Abstract

Aging is associated with multiple human pathologies. In the past few years mitochondrial homeostasis has been well corelated with age-related disorders and longevity. Mitochondrial homeostasis involves generation, biogenesis and removal of dysfunctional mitochondria via mitophagy. Mitophagy is regulated by various mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial factors including morphology, oxidative stress and DNA damage. For decades, DNA damage and inefficient DNA repair have been considered major determinants for age-related disorders. Although defects in DNA damage recognition and repair and mitophagy are well documented to be major factors in age-associated diseases, interactivity between these is poorly understood. Mitophagy efficiency decreases with age leading to accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria enhancing the severity of age-related disorders including neurodegenerative diseases, inflammatory diseases, cancer, diabetes and many more. Therefore, mitophagy is being targeted for intervention in age-associated disorders. NAD+ supplementation has emerged as one intervention to target both defective DNA repair and mitophagy. In this review, we discuss the molecular signaling pathways involved in regulation of DNA damage and repair and of mitophagy, and we highlight the opportunities for clinical interventions targeting these processes to improve the quality of life during aging.

Keywords: DNA damage, DNA Repair, mitophagy, mitochondria, aging

Introduction

According to the “World Population Prospects” 2019, one in six individuals will be over 65 years of age in 2050 and the number of individuals over 80 year will triple from 143 million in 2019 to 426 million in 2050. This exploding increase in the aged population is of serious concern as aging is the highest risk factor for most human diseases. Thus, researchers in the field are aiming to promote healthy aging. Aging involves decline in physical and cognitive abilities of individuals due to increase in stress inducers and a decline in stress repressors. It is an evolutionary conserved phenomenon and researchers have found common factors across the species involved in longevity [1]. Studies have utilized various models ranging from yeast (S. cerevisiae), insects (D. melanogaster), nematodes (C. elegans), rodents (M. musculus) to non-human primates. Despite huge variations in the aging models, defects in insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-sirtuins have emerged as common factors linked with aging processes in various species [2]. Therefore, these models can help us understand some conserved aspects of human aging.

For more than two decades, DNA damage has been considered as the primary conserved factor for aging-associated disorders [3]. Cells are continuously exposed to DNA damage by endogenous and exogenous sources, and DNA repair processes fix these damages. Accumulation of mutations form a molecular basis for aging while DNA damage responses (DDR) play important roles in the protection against various genetic alterations. Defects in DDR genes cause many progeroid and cancer prone syndromes. Another major aspect of the biology of aging involves the mitochondrial theory of aging, which implicates a decline of mitochondrial health as a major causative factor in organismal aging.

Mammalian cells contain two distinct genomes: nuclear and mitochondrial. The nuclear DNA harbors 20000–25000 protein-coding genes with large intergenic non-coding regions spaced across 6 billion bases, while the mitochondrial genome is a small gene-dense circular plasmid with 16569 bases coding for 37 genes. Inherited mtDNA mutations have been implicated in various human diseases ranging from severe (highly penetrant monogenic disorders) to mild in most of the late-onset disorders [4]. Damage in mtDNA has been associated with various age-related disorders including cancer and neurodegeneration. Mitochondria have several mechanisms of quality control, which involves mtDNA repair, removal of damaged mitochondria, and biogenesis, all involved in mitochondrial homeostasis in the cell.

To maintain mitochondrial quality and get rid of damaged/superfluous mitochondria, mitochondria have developed different mechanisms. They use their AAA protease complexes (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) for proteolytic degradation and cytoplasmic proteasomal machinery to remove unfolded proteins. Another pathway for selective degradation of mitochondrial components involves transport of mitochondrial budded vesicles to the lysosomes [5]. The removal of whole mitochondria is accomplished by a selective form of autophagy, called mitophagy. The specific role and underlying mechanism of mitophagy in eliminating mitochondria with mtDNA damage in vivo is a focus of intensive research. Several studies have indicated a decline in mitophagy with age, promoting accumulation of damaged mitochondria. This is implicated in multiple pathological conditions including cardiomyopathy, cardiac hypertrophy, diabetes, fatty liver disease, neurodegenerative disease such as (Alzheimer disease [AD], Parkinson disease [PD], Huntington disease [HD]), cancer and in normal aging [6].

In this review, we will summarize the players involved in DNA damage and repair and mitophagy. We will focus on the interplay between the two and imbalances in associated disorders. Lastly, we will discuss the proposed interventions targeting DNA damage and repair and mitophagy with the aim of promoting healthy aging.

Nuclear DNA Damage and Repair

Nuclear DNA damage has long been implicated as a major underlying risk factor for developmental disorders, aging and age-related disorders. Cellular macromolecules like nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), proteins and lipids are under continuous threat from exogenous and endogenous damaging agents. To cope with the compounding damage, specific cellular pathways have evolved to protect these macromolecules. Unrepaired DNA leads to genomic instability by introducing mutations, and unrepaired DNA and mutations lead to activation of specific signaling pathways that can trigger senescence, cell death or even uncontrolled proliferation [7–10].

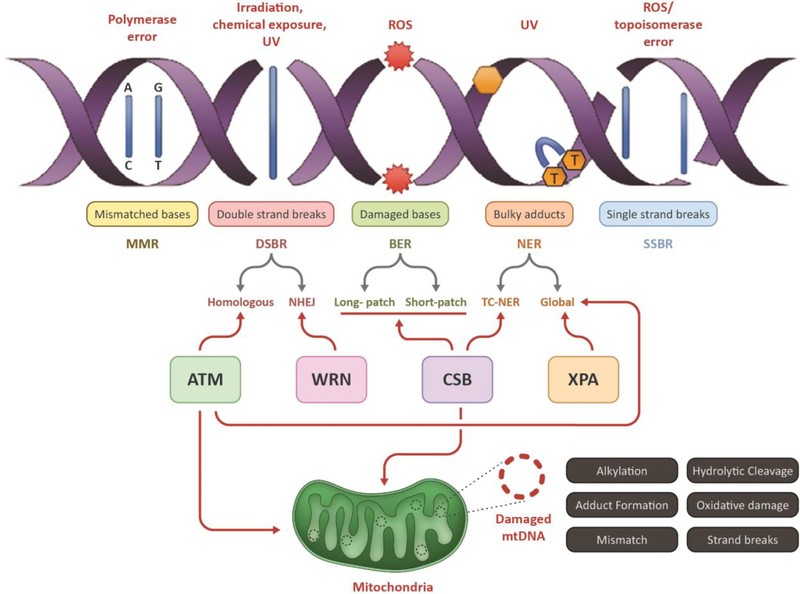

To better understand DNA damage and repair pathways, it is critical to evaluate different DNA damaging agents and the degree of damage caused to the DNA by these sources [11]. Radiation, dietary habits, environmental chemicals like insecticides and pesticides all constitute exogenous DNA damage sources, whereas structural alterations, such as depurination, spontaneous errors during DNA replication, and oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS), are some types of the endogenous damaging sources. Of these, oxidative damage can generate up to 50,000 DNA lesions per human cell per day, including single-strand breaks (SSB’s), double-strand breaks (DSB’s) and interstrand cross-links (ICL’s)[12, 13] (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of different types of nuclear DNA damages and its associated repair pathways:

This figure depicts the major type of nuclear DNAdamages (by stressors) and repair pathways involved in eukaryotic cells including damage recognition, lesion excision;, processing, synthesis of new bases and ligation (left panel). The major repair processes include the mismatch DNA repair (MMR), double strand break repair (DSBR), base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER) and single-strand breaks repair (SSBR). Key players of each step include damage recognition by proteins like glycosylases, lesion excision by nucleases, synthesis of new bases by polymerases and ligation of nicks by ligases. Double strand breaks (DSB) on DNA caused by stressors like UV and ionizing radiation are specifically recognized and repaired by the players of the DSB repair (DSBR) pathway, that includes either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR), depending on the cell-type and stages of cell cycle involved.

As discussed above, mammalian cells are equipped with dedicated DNA repair pathways. Base excision repair (BER) excises mostly non-bulky lesions like oxidation and alkylation damage, which does not distort the double helical structure of the DNA. BER is highly conserved across species and involves four key steps: (a) recognition and excision of the damaged base by a DNA glycosylase like OGG1, NEIL1 or NTH/NTG1, (b) incision of the DNA backbone at the abasic site by the endonuclease APE1, yeast Apn1, (c) gap filling or repair synthesis by a DNA polymerase (d) ligation of the nicks by XRCC1/LIGIII. BER can be classified into two sub-types depending on the repair procedure (step-c): short-patch BER involves a single nucleotide gap to be filled by DNA polymerase beta (Polβ) activity; long-patch BER involves replacement of a longer stretch of 2–10 nucleotides and Polδ/ε with PCNA and RFC synthesize a 2–6 nucleotide track, thus creating a ssDNA overhang. The overhang is removed by the FEN1 endonuclease with nick sealing by LIGI [14]. Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is responsible for removing bulky, helix-distorting lesions like photodimers formed after UV-exposure. NER involves multiple players comprised of at least 25 different proteins, including factors deficient in the human disease Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XPA to XPG, and XPV), as well as Cockayne’s syndrome proteins (CSA and CSB). The global genomic NER (GGR) pathway is involved in the repair of both transcribed and non-transcribed regions, whereas transcription-coupled NER (TCR) is primarily involved in repairing the transcribing strand [7, 15–17].

Mismatch repair (MMR) is responsible for reversing the risk of permanent mutation generated due to replication errors [18]. Double-strand break repair (DSBR) pathways recognizes DNA double strand breaks and repairs them by rejoining the broken DNA ends by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or in a more accurate way by using the undamaged sister chromatid as a template by homologous recombination (HR). As mentioned, DSB repair by HR involves homologous sister chromatids as a template for re-synthesis, which is the preferred pathway for repair of DSBs in S- and G2-phases. The ends of the DSB’s are processed by 5′→3′ exonucleases like the Mre11/RAD50/Nbs1 protein complex, that generates free 3′ ssDNA overhangs. This is followed by binding of RAD52 and RPA leading to strand invasion onto the homologous strand, which is initiated by RAD51 and RAD54 protein. DNA polymerases then extend the strand using the homologous sequence. Consequently, branch migration leads to the formation of Holliday junctions, which are resolved by resolvases. There are several other factors involved in HR-DSB repair. In NHEJ, Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds to the dsDNA ends and recruits DNA-PK. DNA-PKs, once bound to the DNA ends, bring the ends into closer proximity which are further processed by factors like PNK, WRN, Artemis and Mre11/RAD50/Nbs1 to generate blunt ends. The downstream processes are completed by XRCC4/DNA ligase IV, which releases the NHEJ complex from the DNA strand[19–21] (Fig 1). Interestingly, the premature aging associated-proteins, WRN and RECQL4, can be pathway choice factors in DSBR [22, 23].

Mitochondrial DNA Damage and Repair

Mitochondria are crucial cellular organelles whose primary function includes generating ATP for the entire cell through oxidative phosphorylation (respiration). Mitochondrial biogenesis, bioenergetics, dynamics, mitophagy, and mtDNA status play an important role in the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis [24, 25]. Only a few of the essential proteins necessary for respiration are encoded by the mitochondrial genome, and the rest are from the nuclear DNA (nuDNA) [26–28].

The mitochondrial genome is exposed to most of the damaging agents that impact the nuclear genome. The major types of damage known to damage mtDNA are alkylation, hydrolytic damage, bulky adduct formation, oxidative damage, mismatches, and DNA stand breaks. (Fig. 1).

Apart from the damage described in Fig. 1, a variety of mitochondrial mutations have been linked to different disease conditions. Of these, mtDNA 4977 or mitochondrial common deletion (deletion of mitochondrial genome between 8470bp and 13447bp) in human mtDNA has been extensively studied [29]. The common deletion results in complete or partial deletion of genes encoding subunits for complex I and IV, two complex V units and five tRNA genes which are believed to be extremely important for mitochondrial function [30, 31]. More than 100 mtDNA deletions have been reported so far [32]. Common deletions have been studied in regards to pathogenesis of AD and myopathies, Kearns-Sayre syndrome, Pearson’s syndrome and early stages of human colorectal cancer [30, 32–34].

Having reviewed some of the important damage incurred by mtDNA and their relationship with human diseases, we next aim to review some of the critical DNA damage repair pathways involved in the repair of mtDNA.

The major steps in the mitochondrial BER pathway are similar to nuclear BER [35, 36], with the exception that the gap-filing or synthesis step is done by DNA polymerase-gamma (Polγ), the replicative mitochondrial DNA polymerase. However, recently it has been shown that Polβ also can localize to the mitochondria and may function in mtDNA maintenance and mitochondrial homeostasis through its participation in BER [37, 38]. The last step of the BER pathway is ligation of the newly synthesized DNA fragment or inserted nucleotide to the existing backbone. This is done by mitochondrially localized DNA ligase III (LIG III) [28, 39–41].

NER is not thought to be present in mitochondria. This leaves mtDNA extremely vulnerable to damaging agents inducing bulky adducts, like UV [42]. Studies have shown that bulky lesions in nuDNA can be repaired by translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases. In vitro, Polγ shows weak bypass activity over thymine dimers. In a recent study, it was shown that polymerase theta (Polθ) also localizes to mitochondria [43]. The localization of this polymerase to mitochondria increases with oxidative damage. Polθ may be involved in facilitating mtDNA replication under oxidative stress but this process is error prone [44].

Mitophagy

Autophagy is an evolutionary conserved process involving degradation of cytoplasmic substrates with the help of lysosomes (Fig 2). Selective removal of mitochondria is called mitophagy. It involves the removal of dysfunctional mitochondria to maintain mitochondrial quality and turnover and has been associated with physiological and pathological processes (Fig 2). Mitophagy supports human life in various ways including: (i) fertilization by removal of paternal mitochondria, (ii) metabolic switching of cardiomyocytes after birth [6], (iii) differentiation of erythrocytes during maturation, (iv) differentiation of fibroblast to adipocytes and (v) generation of iPS cells (vi) retinal ganglion cell differentiation during embryogenesis [45]. Defects in mitophagy cause mitochondrial dysfunction and accumulation of damaged mitochondria, which has been linked with aging, metabolic disorders, cancer, senescence, inflammation and genomic instability [8].

Figure 2: Schematic representation of autophagy, mitophagy and proteins involved.

(A) Autophagy involves removal of unnecessary or dysfunctional cellular components like proteins, lipids or organelles. Broadly, autophagy is classified as 1. Macroautophagy- It is the most extensively studied form of autophagy for bulk degradation of cellular components. It involves formation of phagophore, a double membrane structure around the targeted components. Autophagosome formed around the target merges with the lysosome leading to formation of autophagolysosomes to enable degradation of engulfed contents. Micro autophagy or chaperone-mediated autophagy involves direct uptake of targeted contents into lysosomes via lysosomal invagination or binding of chaperon tagged proteins to lysosomal-associated membrane protein LAMP-2A. (B) and (C) Mitophagy is a type of macroautophagy targeting mitochondria specifically. (C) Mitophagy receptors can tag mitochondria for phagophore formation in ubiquitin-dependent, LIR-motif protein-dependent and lipid-mediated pathway. The ubiquitin-dependent pathway involves ubiquitination of OMM proteins to form poly ubiquitin chains with the help of E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes. The polyubiquitin chains are detected by NDP52, OPTN, NBR1 and p62 which contains both UBD and LIR motifs. These proteins aid in interaction of ubiquitinated mitochondria to LC3 containing phagophore. LIR-motif protein-dependent pathway involves regulation of expression and modification of LIR-motif containing OMM proteins. Proteins like NIX, BNIP3, FUNDC1 helps with the interaction of targeted-mitochondria to LC3-containing phagophore. Lastly, lipid-mediated mitophagy involves accumulation of LC3 interacting lipids including cardiolipin and ceramide on OMM, tagging mitochondria for phagophore interaction.

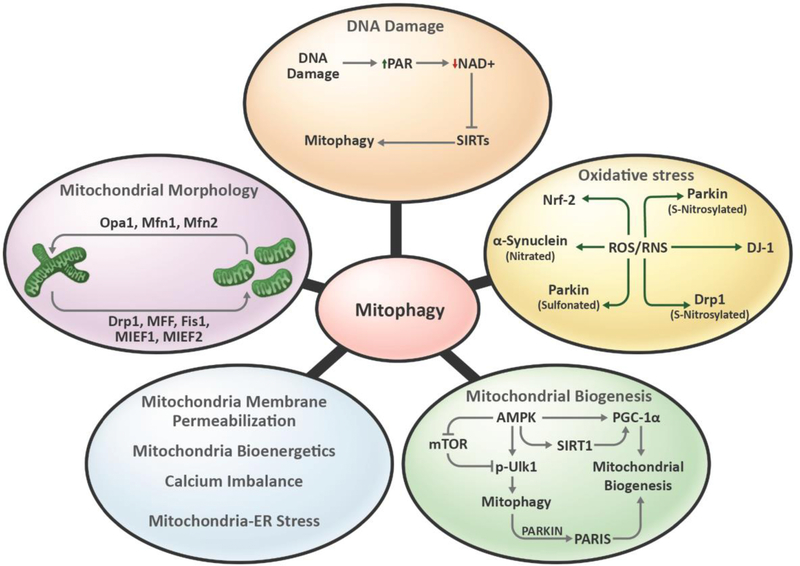

Mitophagy is also regulated by mitochondrial energetics, dynamics, biogenesis, calcium imbalance, mtDNA damage, oxidative stress and overall mitochondrial health (Fig 3). It involves priming of the damaged/superfluous mitochondria and targeting them for phagophore formation and autophagosome engulfment. Mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis regulate mitochondrial homeostasis. Coordination between mitochondrial synthesis and degradation regulates mitochondrial content, quality and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Mitophagy and biogenesis are co-regulated by various shared pathways including AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), CaMK, PKD-NFκB and the Parkin-interacting substrate (PARIS) pathway [46]. Damaged mitochondria undergo changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) causing depolarization. Impaired MMP also regulates the mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery and thereby mitochondrial morphology. The major regulator of mitochondrial fission is DRP1 and for fusion it is MFN1, MFN2 and OPA1 (Fig 3). Mitochondrial fission helps in the separation of dysfunctional mitochondria from healthy mitochondria and is a prerequisite for mitophagy [46, 47]

Figure 3: Mitochondrial factors regulating mitophagy.

Mitochondrial homeostasis plays an important role in regulation of mitophagy. DNA damage, including mtDNA damage, causes increase in PARP activity and thereby reduces cellular NAD+ pools. This further reduces the activity of NAD+-dependent proteins like SIRT1 and thereby mitophagy. Oxidative stress modulates activities of various mitophagy-related proteins. For instance, RNS regulates nitrosylation of Parkin, Drp1, α-synuclein and mitophagy. Mitochondrial biogenesis helps in maintaining mitochondrial content along with mitophagy. Protein like AMPK coordinates the biogenesis and mitophagy balance which is important for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis. Mitochondrial frgmentation regulated by fission proteins including Drp1, MFF, Fis1, MIEF1and MIEF2 helps in segregation of defective mitochondria from healthy mitochondria and aids in mitophagy. Mitochondrial biogenesis, energetics, calcium imbalance and mitochondrial-ER stress regulates mitophagy.

Considering the important role of mitophagy in human pathologies it is important to understand its molecular mechanism in order to target mitophagy with pharmaceutical interventions. The depolarized, fragmented and dysfunctional mitochondria are detected and tagged by mitophagy receptors, which help in the identification of dysfunctional mitochondria by phagophores. Compared to the autophagic machinery, mitophagy-related proteins are less conserved. In mammals, mitophagy receptors prime mitochondria broadly in a ubiquitin-dependent or independent manner as detailed in Fig 3. Ubiquitin-mediated mitophagy mainly involves PINK1/Parkin ubiquitination of mitochondria and targeting of them to a phagophore with the help of ubiquitin binding domain (UBD)-containing mitophagy receptors. Another class of mitophagy receptors include BNIP3, NIX, and FUN14 domain- containing protein 1 (FUNDC1), which are outer membrane proteins (OMM) containing LC3- interacting regions (LIRs) that bind to LC3 for phagophore formation [48]. Various studies have discussed the role of these pathways in regulating mitophagy, however, it is still unclear how independent these pathways are from each other and when they are preferred by the cell.

Ubiquitin-Dependent Mitophagy Receptors-

Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy is the best studied mitophagy pathway. It involves ubiquitination of the damaged/superfluous mitochondria via E3 ligases. Several ubiquitin ligases have been associated with the ubiquitination of defective mitochondria including Parkin, p62, MARCH5, VPS13D, MUL1, ARIH1 and SIAH1 [49]. However, E3 ubiquitin ligases are largely unable to detect the targeted mitochondria and therefore need mediators like PINK1. PINK1 labels depolarized mitochondria and provides a platform for E3 ligases to ubiquitinate OMM proteins. Polyubiquitin chains on OMM proteins are further regulated by deubiquitinating enzymes like USP15, USP30 and USP35, which counteract the pro-mitophagy forces and provide homeostasis [50]. Various other proteins including AMBRA1 and mitochondrial RhoGTase (MIRO) also regulate ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of mitophagy receptors.

| Mitophagy Type | Proteins | Refs |

| Ubiquitin-Dependent Mitophagy | The PINK1/Parkin- PINK1/Parkin pathway is one of the most well studied mitophagy pathways. PINK1 is a Ser/Thr kinase which accumulates on the surface of depolarized mitochondria and thereby provides a platform for Parkin, an E3 ligase. PINK1 phosphorylates Parkin altering its conformation to enhance mitochondrial tethering and ligase activity. Upon recruitment to the depolarized mitochondria Parkin ubiquitinates multiple outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) proteins, which further interact with ubiquitin binding mitophagy receptors. It is important to mention that studies have suggested that there is also PINK1-independent Parkin migration to defective mitochondria. MIRO proteins help in the recruitment of Parkin on damaged mitochondria. | [131] |

| AMBRA1- Autophagy and Beclin 1 Regulator 1 (AMBRA1) is a mitophagy receptor which interacts with Parkin and gets recruited to depolarized mitochondria. AMBRA1 contains LIR to interact with LC3 and helps in autophagosome formation. Interestingly, studies have shown that targeting AMBRA1 to the mitochondria initiates mitophagy in a Parkin- and p62-independent manner. | [132] | |

| Miro- Miro1 and Miro2 are GTPases localized on the OMM. These proteins help in mitochondrial trafficking by interacting with myosin to facilitate mitochondrial movement on microtubules and actin cytoskeleton. Degradation of Miro½ by PINK1/Parkin limits mitochondrial mobility to aid mitophagy. Therefore, MIRO½ also helps in separation of damaged mitochondria from healthy mitochondria to be targeted by mitophagy machinery. | [133] [134] | |

| Ubiquitin-Independent Mitophagy | BNIP3/NIX- BNIP3/NIX are members of the Bcl-2 family localized on OMM. It is a ubiquitin-independent mitophagy receptor which interacts with LC3B. BNIP3 interacts with Drp1 and Opa1 to regulate mitochondrial morphology, modulates mitochondrial membrane potential and thereby mitophagy. BNIP3 and NIX are regulated transcriptionally and translationally to modulate to mitophagy. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) regulates transcription of BNIP3 and NIX and therefore hypoxia-induced mitophagy. In response to stress stimuli, BNIP3 and NIX get phosphorylated resulting in increased affinity to LC3 and promote mitophagy. | [48] |

| FUNDC1- FUN14 Domain Containing 1 (FUNDC1) is an OMM mitophagy receptor. FUNDC1 mediates mitophagy in both ubiquitin-dependent and -independent manners. FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial morphology and quality. Under non-stress conditions FUNDC1 gets phosphorylated by Src and CK2 and interacts with Opa1 to support mitochondrial fusion. However, under hypoxic conditions phosphoglycerate mutase 5 (PGAM5) dephosphorylates FUNDC1 to increase FUNDC1 interaction with DRP1 and LC3B to initiate fission and mitophagy, respectively. In contrast, under hypoxia conditions MARCH5 E3 ubiquitin ligase ubiquitylates FUNDC1 to promote mitophagy. | [48] [135] | |

| BCL2L13- BCL2L13 is a mammalian orthologue of the yeast mitophagy protein Atg32 which is localized on OMM. It is an atypical Bcl-2 family protein which contains four BH motifs. These BH domains are involved in mitochondrial fragmentation and targeting mitochondria to autophagosomes. BCL2L13-mediated mitophagy is independent of DRP1 and Parkin. It utilizes its LIR to interact with LC3 to target fragmented mitochondria to autophagosomes. | [48] | |

| FKBP8- FK506-binding protein 8 (FKBP8) is an anti-apoptotic protein localized on the OMM. FKBP8 also contains a LIR sequence which interacts with LC3A and helps in phagophore formation. | [136] |

Mitophagy receptors utilizing ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms rely on ubiquitin binding domain (UBD) E3 ligases and UBD-motif proteins. Some UBD-motif containing mitophagy receptors including p62, NBR1, NDP52 and optineurin contain UBD and LIR. They detect the ubiquitinylated mitochondria and aid in targeting them to LC3-containing phagophores for mitophagosome formation and mitophagic flux. Other UBD-motif containing mitophagy receptors like RABGEF1 do not contain LIR. RABGEF1 detects mitochondria following ubiquitination and interacts with ATG9A for phagophore elongation and autophagosome formation (Fig 3) [51].

Ubiquitin-Independent Mitophagy Receptors-

Mitophagy receptors utilizing ubiquitin independent mechanisms do not contain UBDs and mainly rely on LIR-motif proteins or lipids. Mitophagy receptors containing LIR are constitutively expressed on the OMM unlike PINK1-Parkin. The activity of the mitophagy receptors is regulated either transcriptionally or via post translational modifications. In this review, we have discussed some of the LIR-motif containing proteins (BNIP3/Nix, FUNDC1, BCL3L13 and FKBP8) involved in ubiquitin-independent mitophagy (Table 1).

Lipid-Mediated Mitophagy

Ceramide and cardiolipin are mitochondrial lipids involved in priming mitochondria for mitophagy. Under mitochondrial stress conditions, ceramide is either targeted to the OMM or is synthesized by mitochondrial ceramide synthase 1 (CerS1). Ceramide on the OMM interacts with LC3 to induce mitophagy. Similarly, cardiolipin, which is normally localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), gets redistributed to the OMM after stress. This stress induced OMM re-localized cardiolipin interacts with LC3 and thereby helps in phagophore formation (Fig 3). Taken together, ubiquitin-dependent, ubiquitin-independent and lipid-mediated mitophagy aid in the removal of targeted mitochondria. However, further investigation is needed to understand the spatiotemporal distribution of these complex pathways.

Mitophagy Inducers

As mentioned above, mitophagy is a fundamental physiological process which helps in maintaining mitochondrial quality and in many cellular processes. The extent of mitophagy varies in different tissues. For instance, heart, skeletal muscle, nervous system, hepatic and renal tissue have higher mitophagy than thymus and spleen [52]. Various exogenous or endogenous stresses can regulate the extent of mitophagy in a specific tissue or organ. Further research is needed to understand how specific mitophagy pathways are triggered by certain stresses. MtDNA damage, mitochondrial heteroplasmy, oxidative stress and nutrient deprivation are some of the stress factors involved in induction of mitophagy. In this section, we will discuss some of these mitophagy-inducing factors.

Nutrient-Regulated Mitophagy

Nutrient starvation has long been linked with mitochondrial degradation. Cells induce mitophagy in response to deprivation of various metabolites ranging from glucose, oxygen, amino acids, vitamins and minerals. Oxygen deprivation or hypoxia regulates mitophagy mainly via upregulation and stabilization of HIF-1α. HIF-1α induces pro-survival effects via limiting oxygen consumption. HIF-1α regulates mitophagy via the BNIP3, FUNDC1 and the PINK1/Parkin pathway [49].

Vitamins and minerals maintain an important role in cellular homeostasis. Deficiency of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, C or D regulates mitophagy and mtDNA maintenance. For instance, vitamin D deficiency suppresses complex I and thereby induces mitophagy [49]. Various studies have suggested a role for vitamin B3 (nicotinamide) depletion with mitophagy repression [53]. Nicotinamide supplementation induces mitophagy by direct activation of the mitophagy machinery including dct-1, pdr-1, and PINK-1 in C. elegans [54]. Mitochondria store various trace mineral elements including iron, selenium, magnesium, manganese, calcium, and zinc. These minerals play an important role in regulating the activity of various mitochondrial enzymes. Iron depletion reduces the activity of electron transport chain (ETC) enzymes, altering the mitochondrial membrane potential and activating Parkin−, PINK1−, and BNIP3-pathway-mediated mitophagy. Similarly, selenium and manganese are cofactors for glutathione peroxidase and MnSOD, respectively, thus manganese regulates oxidative stress facilitated mitophagy. Indirectly, accumulation of calcium and zinc can regulate the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and mitophagy [49].

Oxidative Stress

Autophagy, and its subcomponent mitophagy, have both pro- and anti-survival roles. Oxidative stress plays an important role in this process. Mild oxidative stress induces autophagy/mitophagy to enhance cell survival whereas severe oxidative stress leads to cell death. ROS play an important role in various cellular signaling processes. Oxidative stress induced by an increase in cellular or mitochondrial ROS/RNS induces mitophagy via transcriptional or post-transcriptional mechanisms. Transcriptional regulation involves oxidative stress-mediated increased activation of transcription factors like HIF-1α and Forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a), which induces transcription of mitophagy proteins Bnip3 and Nix [55]. Similarly, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) gets activated in response to oxidative stress and elevates transcription of p62 [55].

ROS/RNS species alter post translational modifications of various proteins to enhance or reduce mitophagic flux. One modulation involves ROS-mediated oxidation of cysteine residue (Cys106) of DJ-1, which triggers its mitochondrial translocation. Once inside mitochondria, DJ-1 interacts with Parkin to regulate the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway, thereby leading to oxidative stress-mediated mitophagy induction. Conversely, inhibition of mitophagy also induces oxidative stress via accumulation of damaged mitochondria. NO, H202 and lipid peroxidation-induced 4-hydroxynonenal can modify S-nitrosylation of various protein. S-nitrosylation of IKKβ and JNK1 can cause inhibition of mTOR and release of Beclin, [56]. Similarly, S-nitrosylation of Drp-1 increases mitochondrial fragmentation and thereby mitophagy. Conversely, studies have also suggested an anti-mitophagy role for ROS via oxidation and/or S-nitrosylation of Parkin, which reduces its E3 ligase activity and consequently mitophagy [57, 58].

Mitochondrial DNA Damage

Mitochondria are the highest producer of free radicals in cells, thus making the mtDNA extremely vulnerable to damage by ROS. This underscores the importance and necessity of preserving mitochondrial genome integrity, with the help of the DNA repair machinery.

Since damage to mitochondria and its DNA is directly relevant to its functional decline and reduced oxidative phosphorylation capacity, it can be assumed that organs, which depend on mitochondrially-derived energy will be most affected by mtDNA damage. Different forms of stressors cause damage to mtDNA. Although mitochondria have a dedicated DNA repair machinery to recognize and repair some types of damaged DNA, accumulation of damaged DNA leads to dysfunctional mitochondria involving loss of membrane potential and inhibition of respiratory complexes. Severely damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria are recognized and ubiquitinated by key players of the autophagy pathway like NIX, E3 ligase and LC3, and targeted for degradation by an autophagosome. The detailed mechanism underlying the induction of mitophagy following mtDNA damage and failure of the repair machinery remains elusive [59]. However, it has been shown through previous studies that NIX or BNIP3 plays a critical role in initiation of mitophagy. Recruitment of NIX protein in response to mitochondrial depolarization is followed by ubiquitination of this protein by the E3 ligase, Parkin [60–62]. In addition to this, earlier studies demonstrated that blockage of mitophagy following DNA damage can lead to an accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria that triggers apoptosis [63]. In a recent study, it was shown that the p62 complex binds to the ubiquitinated membrane of damaged mitochondria and recruits the autophagy-related machinery including LC3II. However, p62’s direct role in inducing mitophagy is still unclear [64].

Accumulating evidence stated in the section above, clearly indicates a role of mtDNA damage in mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition, the machinery dedicated for efficient repair of damaged DNA fails under certain conditions including aging, which leads to an accumulation of damaged mtDNA bases [65]. Although some studies have shown mitophagy as one of the contributing mechanisms for efficient turnover of damaged mtDNA and mitochondria, it is still a topic of future investigation to understand its direct and specific roles in mitochondrial quality control and turnover and how it is triggered by specific types of mtDNA damage.

Mitochondrial Heteroplasmy and Mitophagy

Multiple copies of mtDNA exist in a single eukaryotic cell. Cells can harbor many mtDNAs with varying sequences, a condition termed heteroplasmy. The extent of heteroplasmy varies between cells, tissue, or organs of the same individual. Threshold levels of a pathogenic mtDNA mutation can be defined as the fraction of mtDNA molecules carrying that mutation beyond which respiratory chain defects arise. It had been shown that mitochondria harboring mtDNA mutations in patients with mitochondrial diseases can be propagated, thereby implying inefficient elimination of these mitochondria in vivo[66]. Unfortunately, the mere presence of pathogenic mtDNA mutations is insufficient to elicit mitophagy. Additionally, it has been demonstrated through previous studies that cells can usually tolerate a high level of mtDNA mutations (greater than 80%), thus implying most of these mutations are haploinsufficient or recessive [4].

Cell Senescence

DNA double stranded breaks and thus the repair response is one of the primary factors to induce cellular senescence [67]. Continuous DNA damage induces cell cycle arrest in p53 dependent or independent manner [68] (PMID: 28822740), which also explains increased age-associated senescence. Further, accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria caused by defective mitophagy has been closely linked with senescence [69, 70]. Impaired mitophagy observed in senescent cells could be dependent or independent of cellular autophagy. Interestingly, based on limited evidences senescent cells show opposite effects on autophagy and mitophagy. Senescence appears to have positive correlation with autophagy [71] and negative with mitophagy [70]. Considering these evidences DNA damage, senescence and mitophagy forms a vicious cycle with multiple positive feedback loops [70].Mitophagy in response to nuclear DNA Damage

DNA damage leads to a series of biochemical cascades, ultimately resulting in cellular outcomes such as deficient mitophagy and cell death [72]. In general, low levels of genotoxic stress may stimulate mitochondrial function through hormesis, whereas high levels of stress cause cell death. Damaged mitochondria are selectively identified by autophagy pathways. In mammals, there are several mitophagy pathways, including PINK1/Parkin-dependent and PINK1/Parkin-independent manner[73, 74]. Mitophagy is activated or inhibited by DNA damage and is required for several functional outcomes of DNA damage response signaling, including DNA repair [75], cellular senescence [76], apoptosis [77], and neuroinflammation[78].

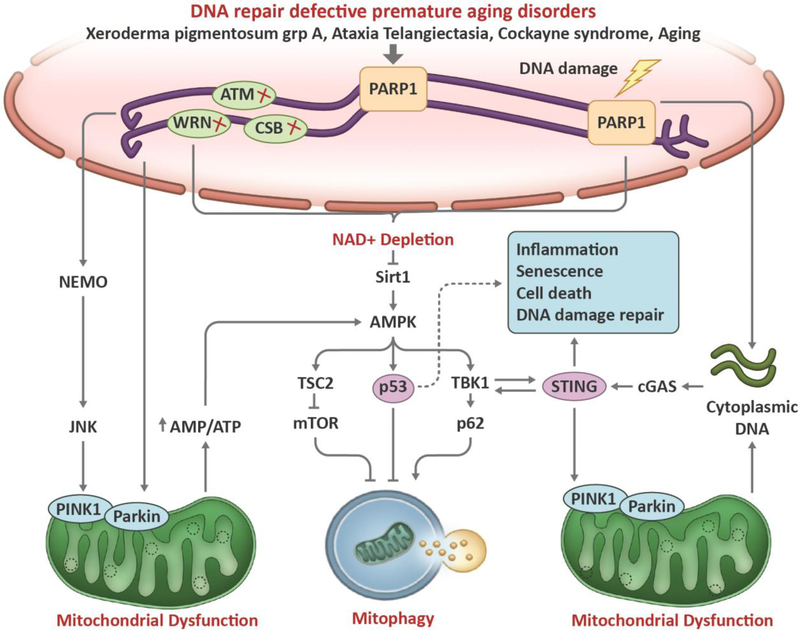

Accumulation of nuclear DNA damage has been implicated in premature aging disorders and normal aging, and the link between DNA damage and neurodegeneration is of great interest currently [7]. Several proteins have been reported that connect nuclear DNA damage with mitophagy (Fig 4). One is the NAD+–SIRT1–PGC-1α axis, in which NAD+ has a pivotal role. NAD+ is an important component that modulates mitochondrial bioenergetics and DNA repair. Activated PARP1, upon DNA damage, facilitates DNA repair but may lead to NAD+ depletion and SIRT1 deacetylation [79, 80]. NAD+ is also a limiting cofactor for SIRTs/sirtuins, such as SIRT1 and the mitochondrial SIRT3. NAD+ insufficiency and SIRT1 inactivation results in compromised mitophagy. SIRT1 plays an important role in mitochondrial biogenesis by deacetylating PGC-1α, which is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [81]. SIRT1 can also regulate mitophagy by maintaining PINK1 integrity through the mitochondrial membrane potential. Inactivation of the NAD+–SIRT1–PGC-1α axis has been shown in Cockayne Syndrome (CS), Ataxia Telangiectasia (A-T), and Xeroderma Pigmentosum group A (XPA), leading to defective mitophagy [79, 80, 82].

Figure 4: Schematic representation of the cross talk between DNA damage to mitophagy.

Compromised DNA repair downregulates mitophagy in aging-related disorders such as Ataxia telangiectasia, Werner syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, and Alzheimer’s disease. When DNA breaks occur, the DNA break sensor PARP1 detects break sites and initiates DNA repair signaling through generation of PAR, a process called PARylation, which consumes NAD+. A decrease in NAD+ and an increase upon DNA damage, nuclear SIRT1 can be activated to facilitate DNA repair. After lethal levels of nuclear DNA damage, SIRT1 is inhibited by the DNA damage response, leading to p53 acetylation and cell death. Loss of SIRT1 activity decreases the stimulation of mitophagy through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator 1α (PGC1α)- and AMP-activated kinase (AMPK)-dependent pathways. SIRT1 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy through deacetylation of PGC1α, and it also interacts with AMPK to regulate mitophagy. In response to DNA damage, ATM is auto phosphorylated within an MRN multiprotein complex that binds DSBs. Activated ATM initiates a pathway that results in activation of AMPK and activates the mTORC1 inhibitor protein tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), thereby further activating autophagy. AMPK also positively regulates PGC1α activity, which stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis. AMPK phosphorylates and activates p53, which propagates pro-apoptotic signals. p53 also has been well characterized in the response to genotoxic stimuli, in which it transcriptionally activates pro-apoptotic proteins such as BAX and p21 while simultaneously inhibiting the ULK1-containing autophagy-initiating complex. In addition, p53 activation may lead to decreased expression of parkin and decreased activation of parkin–PINK1-mediated mitophagy. Damaged DNAfrom nuclear or cytoplasm release into the cytosol. Aberrant localization of DNA in the cytosol activates the cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway, leading to enhanced inflammatory gene expression. Activation of the cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway may stimulate autophagy/mitophagy via a cGAS/beclin-1 interaction–dependent mechanism. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway also promotes autophagy/mitophagy by TBK1-dependent phosphorylation and activation of receptors OPTN and p62 (SQSTM). PINK/Parkin-induced mitophagy inhibits cGAS-cGAMP-STING signaling and innate immunity by mitophagy-mediated mtDNAclearance.

SIRT1 also interacts cooperatively with AMPK, which is a central regulator of metabolism and energy homeostasis, to stimulate mitophagy (Fig 4). SIRT1 can activate or be activated by AMPK [83, 84]. AMPK is also activated by increases in ADP and AMP levels during periods of either low energy availability or increased energy demand [76]. In addition, AMPK is one of downstream target of ATM, which is a master regulator of the DNA damage response. ATM can either directly phosphorylate and activate AMPK or activate the upstream AMPK activator, liver kinase B1 (LKB1) [85]. Upon activation, AMPK promotes mitophagy through phosphorylation and activation of the pro-mitophagic factor ULK1 and TBK1 [86, 87]. In addition, AMPK phosphorylates and activates the mTORC1 inhibitor-TSC2, hereby activating autophagy and decreasing protein synthesis [88].

The protein kinase ATM is a major activator of the DNA double strand break response. ATM binds to DSBs in conjunction with the MRN complex, undergoes autophosphorylation and activation. In turn, ATM activates multiple downstream effector proteins to promote cell survival at low levels of DSBs, including Chk2 and Chk1 involved in cell cycle regulation, the tumor suppressor p53, and transcription factor FOXO3 [89]; conversely, ATM drives cellular apoptosis after extensive DSB damage [72, 90]. This process also promotes ubiquitylation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF‑ κB) essential modifier (NEMO) protein, which translocates from the nucleus to cytoplasm, where it activates the Jun N‑ terminal kinase (JNK) [91, 92]. JNK controls the balance between apoptosis, autophagy and mitophagy through the phosphorylation of specific BCL‑ 2 protein family members, such as BCL‑ 2 and BIM. This releases the pro-autophagy protein Beclin 1 from BCL‑ 2 or BIM complexes, and autophagy is initiated [93]. Thus, in response to DSBs, ATM uses NEMO and JNK to regulate autophagy/mitophagy (Fig 4).

AMPK has been shown to activate p53 in response to metabolic stress. Under lethal genotoxic stress, p53 transcriptionally upregulates cell-fate regulators, such as p21, RB, BAX, and others, which leads to cellular apoptosis, senescence or growth arrest [94, 95]. Of note, p53 in the cytoplasm inhibits mitophagy through disruption of the ULK1-FIP200-ATG13-ATG101 complex [96]. P53 was recently shown to repress the promoter activity, protein, and mRNA levels of PINK1, which downregulates mitophagy [97]. Interestingly, SIRT1 activation induces autophagy via AMPK-mTOR-ULK pathway and mitophagy via the SIRT1–PINK1–Parkin pathway [98]

The cGAS-STING pathway has also been found to interact with DNA damage and mitophagy (Fig 4). The DNA-sensing cGAS-STING pathway modulates inflammatory responses in immune cells to defend against viral and bacterial infections [99]. In addition to foreign DNA, cells can release nuclear or mtDNA into the cytosol under autophagy-deficient conditions that can activate the cGAS-STING pathway [100]. Parkin and PINK1 deficiency-impaired mitophagy leads to STING-dependent inflammation and neurodegeneration [101]. Preventing accumulation of mtDNA in the cytosol by mitophagy may inhibit inflammation and neurodegeneration. Richter et al. recently reported that STING recruits and activates TBK1, which then phosphorylate several mitophagy-related proteins such as optineurin (OPTN) and p6 at their autophagy sites [102]. However, the links in the cGAS-STING pathway, between DNA damage and autophagy/mitophagy remains elusive, and warrants further investigation.

Role of Mitophagy in Age-Associated Disorders

Mitophagy and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Mitophagy [103] and DNA damage [104] have been associated with the development and progression of various neurodegenerative disease including AD, PD, HD and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [105] (Fig 5).

Figure 5: Human pathologies and the organs affected by mitophagy.

Deregulation in mitophagy is linked with various diseases. Mitophagy-associated diseases may affect single organs (like cardiac myopathy, pulmonary disease, fatty liver disease, muscle atrophy) or multiple organs (like cancer, aging, diabetes, inflammatory disease).

AD is the most common neurodegenerative disease characterized by accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau tangles. Studies have suggested increased accumulation of autophagic vacuoles in neuritic processes of AD brains. Inability to clear autophagosomes causes increased accumulation of APP (β-amyloid precursor protein) and enzymes causing increased production of Aβ. Aβ translocate to mitochondria and increases oxidative stress, mitochondrial Ca2+ levels and mitochondrial fragmentation causing mitochondrial dysfunction. Accordingly, Miro deficiency causes tau- and PAR-1-mediated late onset neurodegeneration in drosophila [106]. Interestingly, resveratrol treatment of Aβ1–42-treated PC12 cells increased mitophagy and reduced cell death [107]. AD also shows a reduction in BER [108] and DSB [109] repair making it an important disease model to study connections between DNA damage and mitophagy [110]. Interestingly, mitophagy induction in AD disease models reduces AD pathogenesis and anti-inflammation in microglia [54].

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease and is associated with loss of dopaminergic neurons. Genetic mutations in familial PD genes including Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), PARK7, PINK1, Parkin, or alpha-synuclein (SNCA) are associated with defects in mitochondrial function, mitophagy and oxidative stress. PD-associated pathogenic mutation of LRRK2 prevents its binding to Miro1 and thereby Miro1 degradation which further delays arrest of damaged mitochondria and mitophagy [111]. Along the same lines PD linked α-syn accumulation increases OMM Miro accumulation and inhibits autophagy [112].

HD is characterized by altered dopamine neurotransmission in the striatum and also involves accumulation of defective mitochondria, reduced mitophagy and oxidative stress. HD mouse models show reduced PGC-1α and thereby reduced mitochondrial biogenesis. HD mouse models also show reduced mitophagy in the dentate gyrus [103]. In HD, studies have suggested that mutant Huntingtin interacts with GAPDH and inhibit GAPDH-induced mitophagy [103].

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by deregulated motor neurons in brain and spinal cord. Similar to other neurodegenerative disorders, ALS also involves dysfunctional mitochondria and mitophagy. In the case of familial ALS, a study by Zhang et al. reported reduced Miro1 levels in ALS patient spinal cord samples [113]. Further, mutation in Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) associated with familial ALS also disrupts mitophagy as mutant SOD1 hampers Parkin-dependent Miro1 degradation.

Taken together, oxidative stress-mediated by accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria is considered as an initiator of pathology in most neurodegenerative diseases.

Mitophagy and Cancer

The concept of metabolic switching from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis has been around since 1960’s, the Warburg effect. Since mitochondria play a pivotal role in the metabolic rewiring, one can appreciate the role of mitochondria in fulfilling bioenergetic demands and in the flexibility to use multiple fuel sources of cancer. Since then, various studies have correlated increased mitochondrial dysfunction with cancer pathogenesis [114, 115]. In regard to mitophagy, there is limited information about the role of mitophagy in different human malignancies and this therefore needs further investigation. There are multiple models to support the oncogenic or tumor-suppressive role of mitophagy. Mitophagy induction-based pro-cancer theories involve (i) providing essential amino acid to feed cancer cells, (ii) reducing the mitochondrial mass to aid glycolytic switch, (iii) increase in mitophagy has been linked with increased mitochondrial biogenesis and increased fatty acid oxidation to enhance tumor aggressiveness, and (iv) increased mitophagy increases cancer cell stemness and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Mitophagy induction-based anti-cancer theories comprise (i) oxidative stress-mediated HIF-1α stabilization resulting in increased expression of glycolytic enzymes, (ii) loss of PINK1, NIX and BNIP3 is linked with increased ROS production, HIF-1α stabilization and glycolysis and (iii) AMBRA1 increases cMyc degradation and therefore act as tumor suppressor gene [115]. Altogether, targeting mitophagy or its machinery could potentially be utilized as an anti-cancer therapy.

Mitophagy and Diabetes

Mitochondria plays a key role in maintaining cellular metabolism. Mitochondrial dysfunction is one of the key factors in the pathogenesis of diabetes, a metabolic disorder. In pancreatic beta cells, high glucose levels increase mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Increase in the cellular ATP/ADP ratio blocks K+ channels and depolarizes the plasma membrane resulting in high Ca2+ influx. Enhanced calcium levels bind to insulin containing secretory granules and induces insulin release. Defects in mitochondrial activity reduces β-cell ability to secrete insulin in response to high glucose levels resulting in hyperglycemia/type2 diabetes [116]. Along the same lines, proximal tubule epithelial cells also rely on ATP-dependent Na+/K+-ATPase pumps to create an Na+ gradient. This Na+ is used by sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) to transport glucose from the tubular lumen into the proximal tubule epithelial cells. Mitochondrial dysfunction therefore disrupts tubular reabsorption and causes renal proximal tubule epithelial cell injury [55]. Various studies have suggested a decrease in mitophagy proteins in diabetic rats. In case of diabetic cardiomyopathy, reduced Sirt3-Foxo3A-Parkin-mediated mitophagy accelerates diabetic cardiomyopathy [117]. Pancreatic β-cell inflammation is a common diabetic phenotype. There are contradicting reports regarding the role of diabetes in β-cell inflammation as suppression or activation of autophagic machinery has been linked with increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β [116].

Mitophagy and Inflammatory Diseases

Inflammatory diseases like sepsis, pulmonary inflammatory diseases, cardiac inflammation, neuroinflammation, peritoneal inflammatory injury, and renal inflammation show dysfunctional mitophagy (Fig 5). Mitochondria play an important role in the cellular response to stress. Defects in mitophagy causes accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and increases damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMPs) and mtROS. The mtROS causes activation of MAPKs by inhibiting MAPK phosphatase. Activated MAPK aids in the production of IL-6 and TNF, mtROS accumulation also activates the NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which promotes the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18. mtDNA accumulation in the cytosol directly interacts with TLR-9 or high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) to induce inflammatory responses. Further, cytosolic mtDNA can activate cGAS-STING to induce IFN-1 or the NLRP3 inflammasome to induce maturation/ secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [118].

DNA Repair Deficiency Disorders and Mitophagy-

Mitophagy and metabolic alterations have emerged as important for DNA repair disorders (Fig 5). Mitophagy targets mitochondria with disrupted MMP. In that regard, studies have implicated the role of increased MMP in XPA, Cockayne syndrome, and ataxia-telangiectasia patients cell lines [119]. Another potential mechanism involves DNA damage-mediated persistent PARylation leading to a decline in NAD+ and SIRT1 activity suggesting decreased activation of SIRT1/PGC. 1α/UCP2 axis.

Ataxia telangiectasia, a rare autosomal recessive disorder involves defects in ATM and thereby in DNA repair. Fang et al. have suggested a role of defective mitochondria and mitophagy in the pathogenesis of A-T [120]. Interestingly, treatment with NAD+ precursor stimulate DNA repair, mitochondrial quality and mitophagy, and can therefore be proposed as potential therapeutic strategy for A-T [120]. In case of Fanconi Anemia, cells show increased mitochondria fission, increased oxidative stress and defective mitophagy leading to accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria [121]. Mutations in BRCA1, associated with breast cancer also show increases in mitochondrial content and reduced mitophagy [122]

Mutations in the NER pathway machinery, associated with pathogenesis of autosomal recessive inherited CS or Xeroderma pigmentosum also show increased mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ), oxidative stress and impaired mitophagy [123]. Fang et al. showed that a reduced NAD+-SIRT1-PGC-1α axis in response to DNA damage caused defective mitophagy [124]. These studies suggest an important role of nuclear-mitochondrial crosstalk in maintaining mitochondrial quality and thereby human health.

Drugs Targeting Mitophagy

Mitophagy has emerged as a therapeutic target for various diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer and diabetes. However, non-selective inhibition or induction of mitophagy can hamper various physiological processes as described previously. Accordingly, exploring if any adverse effects are associated with modulation of basal mitophagy could provide clues to the diagnosis and therapy. Various studies have suggested pharmacological and biological strategies to manipulate mitophagy (Table 1).

Natural Mitophagy Inducers-

Several naturally occurring compounds like actinonin, resveratrol, urolithin A, spermidine and some antibiotics have been reported to stimulate mitochondrial health. However, the exact molecular mechanism utilized by these compounds is unknown. Resveratrol triggers the SIRT1–PGC-1α axis and therefore induces mitochondrial biosynthesis. Actinonin, a naturally occurring antibiotic, enhances mitophagy in mt-Keima mouse-derived neuronal stem cells. Another natural compound, Urolithin A, a metabolite derived from pomegranates, acts as a mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis inducer. In C. elegans, Urolithin A induces mitophagy probably via SKN-1 and thereby increases C. elegans lifespan. In the mouse, urolithin A-mediated upregulation of mitophagy improves muscle function [103]. A recent study has shown the mitophagy-inducing potential of NAD+ supplementation, urolithin A, and actinonin in suppressing neuroinflammation and AD pathogenesis in animal AD models [54]. NMN, urolithin A, and actinonin regulate mitophagy proteins like dct-1, pdr-1, and pink-1 in C. elegans. This raises the question: at what stage in AD pathogenesis is it more beneficial to induce mitophagy, and secondly, which mitophagy inducer works better at which specific stage in AD?

One important question that needs to be addressed is the effect of NAD+ supplementation and urolithin A treatment on DNA repair. NR has been linked with boosting NHEJ DSB repair in a SIRT1-dependent and -independent manner in ATM-deficient worms [125]. Urolithin A has been shown to induce NER in UV B-damaged cells [126]. Whether these agents modulate other DNA repair pathways should be evaluated.

Calorie restriction has long been established as an inducer for autophagy and promotes longevity. Studies have also implemented the role of exercise and calorie restriction on the removal of mutant mtDNA, and mitophagy [127]. Further, calorie restriction also stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis [128].

Various synthetic drugs have been identified to restore mitophagy. Boyle et al. utilized mitochondrially targeted 3-Carboxyl proxyl nitroxide (Mito-CP) and Mito-metformin to target mitochondrial activity. Mito-CP and Mito-metformin decreased oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondria ATP levels, and MMP leading to increased AMPK activation and mTOR inhibition eventually stimulating mitophagy and inhibiting cancer cell proliferation [129]. Various other chemical mitophagy inducers are detailed in Table 2. These inducers are extensively used in biological studies to obtain mechanistic insight. However, most of these inducers have off target effects and therefore minimal clinical utility.

Table 2:

Chemical mitophagy inducers

| Mitophagy Inducer Type | Mechanism | Examples | Refs |

| H+ Ionophores | H+ ionophores modulate proton transfer across the IM causing proton leak and loss of MMP. These ionophores have off-target effect causing plasma membrane depolarization and cytotoxicity. However, second generation ionophores like Bam15 have less off target effects. | (CCCP) and carbonyl cyanide-p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and to a lesser extent the 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP), BAM15 | [137] |

| K+ Ionophore | Targets import of K+ ions across the IM and thereby alters MMP. Induces lethal mitochondrial damage. | Valinomycin, Salinomycin | [137] |

| ETC inhibitor | Targets mitochondrial respiration to induce ROS production and mitophagy. Drugs are less specific but have fewer toxic effects. | AntimycinA, Oligomycin, | [137] |

| PINK1-Parkin independent | Induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial depolarization to activate and recruit autophagic activation molecules including MUL1-ULK1 (sodium selenite), cardiolipin-LC3 (Rotenone, 6-OHDA), Mito-Erk2 (6-OHDA and MPP+). | Sodium Selenite, Rotenone, 6-OHDA and MPP+ | [137] |

| PINK1-Parkin inducer | ROS-mediated by paraquat induces complex 1mediated ROS generation causing mitochondrial depolarization and PINK1-Parkin activation. | Paraquat | [137] |

| Kinetin directly increases PINK1 activity, pifithrin-α inhibits p53 and thereby increases PARK2 expression. | Kinetin (KATP precursor), pifithrin-α | [137] | |

| Iron chelators | Iron depletion induces mitophagy in a mitochondrial depolarization-dependent or independent manner | DFP, 1,10’-Phenanthroline, Cicloprox Olamine, 2’2-Bipyridyl | [137] |

| SIRT1 activators | Direct increase in SIRT1 deacetylation activity triggers activation of LC3, UCP2 and FOXO3-BNIP23-mediated mitophagy | NAM (NAD+ precursor), Resveratrol, Fisetin, SRT1720 | [137, 138] |

| Reduces NAD+ consumption indirectly to avail more NAD+ for SIRT1 activity. | Olaparib (PARP-1 inhibitor) | [137] |

Other than pharmacological inhibition, p53 inhibition disrupts p53-Parkin interaction thereby providing more Parkin for mitochondrial translocation. Knockdown of mitochondrial deubiquitinating enzymes including USP30 and USP15 would enhance poly-ubiquitin chains and prime mitochondria for Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Along the same lines activating NRF2 could increase transcription of genes (like p62 and NDP528) containing antioxidant response elements (AREs) in promoter regions and therefore could increase mitophagy.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Mitochondrial dysfunction and genomic instability have been implicated in pathophysiology of cancer, neurodegeneration, diabetes and in normal aging. Understanding the molecular biology of the regulation of mitochondrial activity and mitophagy in regard to DNA damage will reveal, not only mechanistic links, but also therapeutic targets. Defects in DNA repair pathways have been associated with hampered mitophagy. Also, there is limited information available on effect of defects in DNA repair on another mitochondrial quality control pathway, UPRmt. Further studies are needed to understand the role of UPRmt in neurodegeneration and other age-associated disorders [130]. Undoubtedly, mitochondrial health plays an important role in the aging process. Understanding the role of mitophagy in nuclear DNA repair could be an important research axis for a combined therapy towards longevity.

Mitophagy shows spatiotemporal distribution and have different physiological and pathological roles in different tissues. It is important to understand the role of mitophagy in stem cell renewal and function [103]. Additionally, in the past decades it has become well established that inhibition of autophagy and/or mitophagy contributes to the pathogenesis of various diseases.

Therapeutic interventions targeting mitophagy could have high impact on human health. Future studies are needed to develop specific gene therapies and drugs for induction of mitophagy. It is unclear how calorie restriction stimulates mitophagy and/or mitochondrial biogenesis. Mechanistic insights into the molecular mechanisms will help in the formulation of individualized medicine. In the past, combinatorial approaches have shown promising results. In terms of targeting mitophagy, more studies to fully explore the therapeutic drugs and targets that modulate mitophagy and treat various human pathologies are warranted.

Highlights.

DNA damage regulates mitophagy induction and mitochondrial homeostasis

Nuclear-mitochondrial signaling modulates aging and age-associated disorders

Combinatorial approaches targeting DNA repair and mitophagy could promote healthy aging

Acknowledgements and Funding

We thank Dr Yujun Hou and Yong Wei for critical reading of the manuscript, and Marc Raley for help with the figures. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

Dr. Bohr’s laboratory has a CRADA arrangements with ChromaDex, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pitt JN and Kaeberlein M, Why is aging conserved and what can we do about it? PLoS Biol, 2015. 13(4): p. e1002131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AA, Aging across the tree of life: The importance of a comparative perspective for the use of animal models in aging. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2018. 1864(9 Pt A): p. 26802689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gensler HL and Bernstein H, DNA damage as the primary cause of aging. Q Rev Biol, 1981. 56(3): p. 279–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart JB and Chinnery PF, The dynamics of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy: implications for human health and disease. Nat Rev Genet, 2015. 16(9): p. 530–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashrafi G. and Schwarz TL, The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ, 2013. 20(1): p. 31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong G, et al. , Parkin-mediated mitophagy directs perinatal cardiac metabolic maturation in mice. Science, 2015. 350(6265): p. aad2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maynard S, et al. , DNA Damage, DNA Repair, Aging, and Neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2015. 5(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang EF, et al. , Nuclear DNA damage signalling to mitochondria in ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2016. 17(5): p. 308–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer NC, Corbett AH, and Doetsch PW, The current state of eukaryotic DNA base damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015. 43(21): p. 10083–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hegde ML, Bohr VA, and Mitra S, DNA damage responses in central nervous system and age-associated neurodegeneration. Mech Ageing Dev, 2017. 161(Pt A): p. 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkwood TB, Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell, 2005. 120(4): p. 437–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindahl T, Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature, 1993. 362(6422): p. 709–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyama T. and Wilson DM 3rd, DNA repair mechanisms in dividing and non-dividing cells. DNA Repair (Amst), 2013. 12(8): p. 620–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortini P, et al. , The base excision repair: mechanisms and its relevance for cancer susceptibility. Biochimie, 2003. 85(11): p. 1053–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa RM, et al. , The eukaryotic nucleotide excision repair pathway. Biochimie, 2003. 85(11): p. 1083–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, et al. , Evidence of ultraviolet type mutations in xeroderma pigmentosum melanomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(15): p. 6279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Steeg H. and Kraemer KH, Xeroderma pigmentosum and the role of UV-induced DNA damage in skin cancer. Mol Med Today, 1999. 5(2): p. 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu D, Keijzers G, and Rasmussen LJ, DNA mismatch repair and its many roles in eukaryotic cells. Mutat Res, 2017. 773: p. 174–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scully R, et al. , DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang HHY, et al. , Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2017. 18(8): p. 495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen NB, Rasmussen M, and Rasmussen LJ, Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA repair: similar pathways? Mitochondrion, 2005. 5(2): p. 89–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu H, et al. , RECQL4 Promotes DNA End Resection in Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Cell Rep, 2016. 16(1): p. 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamanna RA, et al. , WRN regulates pathway choice between classical and alternative non-homologous end joining. Nat Commun, 2016. 7: p. 13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Um JH and Yun J, Emerging role of mitophagy in human diseases and physiology. BMB Rep, 2017. 50(6): p. 299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babbar M. and Sheikh MS, Metabolic Stress and Disorders Related to Alterations in Mitochondrial Fission or Fusion. Mol Cell Pharmacol, 2013. 5(3): p. 109–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holt IJ, et al. , Mammalian mitochondrial nucleoids: organizing an independently minded genome. Mitochondrion, 2007. 7(5): p. 311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazak L, Reyes A, and Holt IJ, Minimizing the damage: repair pathways keep mitochondrial DNA intact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2012. 13(10): p. 659–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexeyev M, et al. , The maintenance of mitochondrial DNA integrity--critical analysis and update. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013. 5(5): p. a012641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortopassi GA and Arnheim N, Detection of a specific mitochondrial DNA deletion in tissues of older humans. Nucleic Acids Res, 1990. 18(23): p. 6927–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nie H, et al. , Mitochondrial common deletion, a potential biomarker for cancer occurrence, is selected against in cancer background: a meta-analysis of 38 studies. PLoS One, 2013. 8(7): p. e67953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng TI, et al. , Visualizing common deletion of mitochondrial DNA-augmented mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis upon oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2006. 1762(2): p. 241–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen T, et al. , The mitochondrial DNA 4,977-bp deletion and its implication in copy number alteration in colorectal cancer. BMC Med Genet, 2011. 12: p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor RW and Turnbull DM, Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nat Rev Genet, 2005. 6(5): p. 389–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmadi M, Golalipour M, and Samaei NM, Mitochondrial Common Deletion Level in Blood: New Insight Into the Effects of Age and Body Mass Index. Curr Aging Sci, 2019. 11(4): p. 250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akbari M, et al. , Overexpression of DNA ligase III in mitochondria protects cells against oxidative stress and improves mitochondrial DNA base excision repair. DNA Repair (Amst), 2014. 16: p. 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu S, Je G, and Kim YS, Transcriptional mutagenesis by 8-oxodG in alpha-synuclein aggregation and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Mol Med, 2015. 47: p. e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sykora P, et al. , DNA Polymerase Beta Participates in Mitochondrial DNA Repair. Mol Cell Biol, 2017. 37(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad R, et al. , DNA polymerase beta: A missing link of the base excision repair machinery in mammalian mitochondria. DNA Repair (Amst), 2017. 60: p. 77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohr VA, Repair of oxidative DNA damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, and some changes with aging in mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med, 2002. 32(9): p. 804–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Croteau DL and Bohr VA, Repair of oxidative damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem, 1997. 272(41): p. 25409–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svilar D, et al. , Base excision repair and lesion-dependent subpathways for repair of oxidative DNA damage. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011. 14(12): p. 2491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Houten B, Hunter SE, and Meyer JN, Mitochondrial DNA damage induced autophagy, cell death, and disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2016. 21: p. 42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wisnovsky S, et al. , DNA Polymerase theta Increases Mutational Rates in Mitochondrial DNA. ACS Chem Biol, 2018. 13(4): p. 900–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasiviswanathan R, et al. , Human mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma exhibits potential for bypass and mutagenesis at UV-induced cyclobutane thymine dimers. J Biol Chem, 2012. 287(12): p. 9222–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esteban-Martinez L, et al. , Programmed mitophagy is essential for the glycolytic switch during cell differentiation. EMBO J, 2017. 36(12): p. 1688–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palikaras K. and Tavernarakis N, Mitochondrial homeostasis: the interplay between mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis. Exp Gerontol, 2014. 56: p. 182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubli DA and Gustafsson AB, Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circ Res, 2012. 111(9): p. 1208–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palikaras K, Lionaki E, and Tavernarakis N, Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat Cell Biol, 2018. 20(9): p. 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X, et al. , Mitochondrial DNA Mutation, Diseases, and Nutrient-Regulated Mitophagy. Annu Rev Nutr, 2019. 39: p. 201–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gersch M, et al. , Mechanism and regulation of the Lys6-selective deubiquitinase USP30. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2017. 24(11): p. 920–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamano K, et al. , Endosomal Rab cycles regulate Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Elife, 2018. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun N, et al. , Measuring In Vivo Mitophagy. Mol Cell, 2015. 60(4): p. 685–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang EF and Bohr VA, NAD(+): The convergence of DNA repair and mitophagy. Autophagy, 2017. 13(2): p. 442–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fang EF, et al. , Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-beta and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci, 2019. 22(3): p. 401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higgins GC and Coughlan MT, Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy: the beginning and end to diabetic nephropathy? Br J Pharmacol, 2014. 171(8): p. 1917–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee J, Giordano S, and Zhang J, Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem J, 2012. 441(2): p. 523–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yao D, et al. , Nitrosative stress linked to sporadic Parkinson’s disease: S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(29): p. 10810–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meng F, et al. , Oxidation of the cysteine-rich regions of parkin perturbs its E3 ligase activity and contributes to protein aggregation. Mol Neurodegener, 2011. 6: p. 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bess AS, et al. , UVC-induced mitochondrial degradation via autophagy correlates with mtDNA damage removal in primary human fibroblasts. J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2013. 27(1): p. 28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novak I, et al. , Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep, 2010. 11(1): p. 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ding WX, et al. , Nix is critical to two distinct phases of mitophagy, reactive oxygen species-mediated autophagy induction and Parkin-ubiquitin-p62-mediated mitochondrial priming. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(36): p. 27879–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsuda S, et al. , Functions and characteristics of PINK1 and Parkin in cancer. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2015. 20: p. 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cotan D, et al. , Secondary coenzyme Q10 deficiency triggers mitochondria degradation by mitophagy in MELAS fibroblasts. FASEB J, 2011. 25(8): p. 2669–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Czarny P, et al. , Autophagy in DNA damage response. Int J Mol Sci, 2015. 16(2): p. 2641–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trifunovic A, Mitochondrial DNA and ageing. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2006. 1757(5–6): p. 611–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wallace DC and Chalkia D, Mitochondrial DNA genetics and the heteroplasmy conundrum in evolution and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013. 5(11): p. a021220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Passos JF, et al. , Feedback between p21 and reactive oxygen production is necessary for cell senescence. Mol Syst Biol, 2010. 6: p. 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bielak-Zmijewska A, Mosieniak G, and Sikora E, Is DNA damage indispensable for stress-induced senescence? Mech Ageing Dev, 2018. 170: p. 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Correia-Melo C, et al. , Mitochondria are required for pro-ageing features of the senescent phenotype. EMBO J, 2016. 35(7): p. 724–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Korolchuk VI, et al. , Mitochondria in Cell Senescence: Is Mitophagy the Weakest Link? EBioMedicine, 2017. 21: p. 7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Young AR and Narita M, Connecting autophagy to senescence in pathophysiology. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2010. 22(2): p. 234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fang EF, et al. , Nuclear DNA damage signalling to mitochondria in ageing. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 2016. 17(5): p. 308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Di Rita A, et al. , HUWE1 E3 ligase promotes PINK1/PARKIN-independent mitophagy by regulating AMBRA1 activation via IKKalpha. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jian F, et al. , Sam50 regulates PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy by controlling PINK1 stability and mitochondrial morphology. Cell Rep, 2018. 23(10): p. 2989–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Croteau DL, et al. , NAD+ in DNA repair and mitochondrial maintenance. Cell Cycle, 2017. 16(6): p. 491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wiley CD, et al. , Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence with a distinct secretory phenotype. Cell Metab, 2016. 23(2): p. 303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Youle RJ and Narendra DP, Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2011. 12(1): p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kerr JS, et al. , Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Neurosci, 2017. 40(3): p. 151–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fang EF, et al. , Defective mitophagy in XPA via PARP-1 hyperactivation and NAD+/SIRT1 reduction. Cell, 2014. 157(4): p. 882–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fang EF, et al. , NAD+ replenishment improves lifespan and healthspan in ataxia telangiectasia models via mitophagy and DNA repair. Cell Metab, 2016. 24(4): p. 566–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chalkiadaki A. and Guarente L, The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 2015. 15(10): p. 608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheibye-Knudsen M, et al. , Cockayne syndrome group B protein prevents the accumulation of damaged mitochondria by promoting mitochondrial autophagy. J Exp Med, 2012. 209(4): p. 855869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cantó C, et al. , AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature, 2009. 458(7241): p. 1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Price NL, et al. , SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell Metab, 2012. 15(5): p. 675–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tripathi DN, et al. , Reactive nitrogen species regulate autophagy through ATM-AMPK-TSC2–mediated suppression of mTORC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(32): p. E2950-E2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heo J-M, et al. , The PINK1-PARKIN mitochondrial ubiquitylation pathway drives a program of OPTN/NDP52 recruitment and TBK1 activation to promote mitophagy. Mol Cell, 2015. 60(1): p. 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lautrup S, et al. , Microglial mitophagy mitigates neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int, 2019. 129: p. 104469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]