Abstract

The number of long-term cancer survivors (≥5 years after diagnosis) in the U.S. continues to rise, with more than 10 million Americans now living with a history of cancer. Along with such growth has come increasing attention to the continued health problems and needs of this population. Many cancer survivors return to normal functioning after the completion of treatment and are able to live relatively symptom-free lives. However, cancer and its treatment can also result in a wide range of physical and psychological problems that do not recede with time. Some of these problems emerge during or after cancer treatment and persist in a chronic, long-term manner. Other problems may not appear until months or even years later. Regardless of when they present, long-term and late effects of cancer can have a negative effect on cancer survivors’ quality of life. This article describes the physical and psychological long-term and late effects among adult survivors of pediatric and adult cancers. The focus is on the prevalence and correlates of long-term and late effects as well as the associated deficits in physical and emotional functioning. In addition, the emergence of public health initiatives and large-scale research activities that address the issues of long-term cancer survivorship are discussed. Although additional research is needed to fully understand and document the long-term and late effects of cancer, important lessons can be learned from existing knowledge. Increased awareness of these issues is a key component in the development of follow-up care plans that may allow for adequate surveillance, prevention, and the management of long-term and late effects of cancer.

Keywords: cancer, survivorship, quality of life, long-term effects

The number of long-term cancer survivors (≥5 years after diagnosis) in the U.S. is increasing because of advances in cancer screening, early detection, treatment strategies, and management of acute treatment toxicities. Indeed, the 5-year survival rate for all cancers combined has risen to 66%, up from approximately 50% in the 1970s,1 and it is estimated that there are now more than 10 million Americans living with a history of cancer.2 Furthermore, based partly on the overall growth and increasing average age of the U.S. population, researchers are predicting that the number of persons over the age of 65 years diagnosed with cancer each year will double by the year 2050, and will quadruple among those aged ≥85 years in the same time frame.3 Considered together, these factors suggest that the number of cancer survivors in this country will continue to grow and that their long-term heath problems and resulting needs will demand increasing attention.

In point of fact, the very same treatments that have helped realize improved cancer survival rates can also cause several physical and psychological sequelae. Some of these symptoms may persist for an extended period after cancer treatment is completed, taking on a long-term nature. Other symptoms and conditions, often referred to as late effects, may not be present during active treatment but instead appear months or years later. It is not always possible to definitively identify the point at which a symptom first appears, which may blur the lines between long-term and late effects. For current purposes, however, we consider long-term effects to be those that develop during active treatment and that persist for at least 5 years after the completion of initial cancer treatment. Examples of long-term effects include neuropathies, with related weakness, numbness, or pain; fatigue; cognitive or sexual difficulties; and elevated anxiety or depression.

In contrast, late effects are generally conceptualized as those problems that are not present or identified after treatment but may develop as outgrowths of the effects of treatment on organ systems or the psychological process. In some cases, such as depression, the distinction may be difficult to discern. In other cases, such as musculoskeletal complications or late-onset stamina deficits related to cardiovascular complications or hypothyroidism, the distinction may be both clear and important, as the presence of a symptom may be a signal of an emerging medical problem.

Regardless of whether a symptom or condition is considered a long-term or a late effect, an emerging body of research has begun to document the problems for which long-term cancer survivors are at increased risk, including second cancers and other comorbid conditions.4 It is not yet clear how fully this research has resulted in increased surveillance of cancer-related risk factors. In fact, some researchers have suggested that having a history of cancer may actually distract attention away from other health conditions, delaying general healthcare and exposing a survivor to other health risks.5 Thus, gaining a better understanding of the long-term and late effects of cancer will allow clinicians and researchers to develop appropriate follow-up care plans, educate survivors in preventive and early detection healthcare needs, and ultimately improve the quality of life (QOL) of cancer survivors.

This article reviews the current knowledge regarding the physical and psychological long-term and late effects among adult survivors of pediatric or adult cancers who have completed treatment. The first section focuses on physical function and symptoms. The emphasis is not on medical complications, but rather on functional impacts of the disease and related complications. The second section addresses the issues of determining the prevalence and associated factors of psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Finally, the discussion describes some national public health initiatives and research activities that have drawn additional attention to the need for improved understanding, assessment, monitoring, and management of long-term and late effects of cancer.

Physical Long-term and Late Effects of Cancer

Initial efforts to address the needs of long-term cancer survivors focused on causes of late mortality and medical late effects, such as recurrences, second cancers, and cardiopulmonary risks. More recently, research has begun to document physical and functional difficulties that do not always resolve with the conclusion of treatment or that become problematic in survivors earlier than expected with normal aging.

As detailed in this section, a majority of long-term survivors describe themselves as having good to excellent health and function. Along with this generally high QOL, however, specific deficits are more prevalent in survivors than in adults of similar age with no history of cancer. The focus of this section is on functional health outcomes in adult survivors of childhood or adult cancers. Among issues that are notably more common across survivors of numerous diagnoses are fatigue, sexual problems, and musculoskeletal symptoms. Functional difficulties with returning to work and restricted physical and social activities have also been identified in some survivors.

Population-based, Case-control Studies Across Cancer Diagnoses

Existing population-based cohorts have provided valuable data on distinguishing differences between long-term cancer survivors and matched controls without a cancer history. Ness et al.6 compared cases and controls using the 1999–2002 population-based home interview survey from the Centers for Disease Control National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database of 10,083 adults. Of these, 279 were recent cancer survivors and 434 were survivors for ≥5 years (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers). They reported that long-term adult survivors had a higher likelihood of physical limitations (53% compared with 21% for controls without cancer). Activities that required sustained muscle activity were most likely to be impaired. These survivors also had higher rates of restricted participation in sustained activities such as shopping, sports, and social events (31% vs 13% reported by controls). Rates of restricted participation in these activities increased with age and with decreasing household income, regardless of cancer history.

Longitudinal, population-based studies of aging provide useful cohorts for examining differences between those with and without a history of cancer. The Iowa Women’s Health Study provided a database of 25,719 postmenopausal women, with a median age of 72 years. Of the 2218 participants with a cancer history, 1068 were long-term survivors (≥5 years after diagnosis). Sweeney et al7 found that compared with controls the elderly female cancer survivors in the Iowa study reported only modest but significant differential rates of inability to do heavy housework (42% vs 31%), walk a half mile (26% vs 19%), or walk up and down stairs (9% vs 6%). The investigators noted that the impaired activities were those requiring muscle strength, stamina, or mobility, whereas no increased difficulty was detected in ability to go out to activities or to prepare meals. Deficits were not attributable to a specific disease or type of treatment.

Another survey that used similar comparison methods found that the survivors and controls did not differ in rates of cognitive dysfunction and mental health, but that survivors had higher rates of numerous health conditions and functional limitations.8 It should be noted, however, that nearly all these differences were in the small to moderate range. This emphasizes the importance of attending to the clinical meaningfulness of differences in these large epidemiologic samples. It is also worth noting that in several other studies of elderly persons with a history of cancer, most survivors attributed their health problems to aging and not to cancer.8,9

Our understanding of physical limitations in childhood cancer survivors has greatly expanded with the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). The CCSS is following more than 10,000 5-year plus survivors of childhood cancers and greater than 3000 sibling controls.10 Only 11% of the adult long-term survivors in this cohort reported fair or poor general health compared with 5% of siblings.11 However, 44% of the survivor adults reported 1 or more specific impairments in function. Physical limitations were reported in 20% of the childhood survivors compared with 12% of siblings.12 The greatest risk of poor health has been seen in those with central nervous system (CNS) and bone cancer histories.11 Radiotherapy to the brain, being female, having a high school education or less, and lower income also increased risk for physical and activity limitations in the survivors.11,12 Potentially contributing to physical deficits, a majority of these survivors had 1 or more chronic health conditions.13

Few studies have directly examined the influence of race or ethnicity on survivorship outcomes. Castellino et al.14 used the CCSS database to consider these influences on long-term adult survivors of childhood cancers. After adjusting for socioeconomic status, neither health status nor late mortality rates differed between the white, black, and Hispanic groups.

Maunsell et al.15 reported on a Canadian cohort of 1334 child or adolescent long-term cancer survivors compared with 1477 matched controls. Most survivors were >10 years after diagnosis. Fewer survivors (62%) versus controls (71%) reported good to excellent health, and survivors were more likely to have 1 or more physical health problem (73% vs 53% in controls). Although females were slightly more likely to report functional problems, the investigators judged the sex differences to be clinically insignificant. Consistent with the CCSS, the greatest deficits in physical function were noted in those who survived CNS and bone cancers. Other risk factors included more than 1 treatment series and 2 or more organ system dysfunctions. Cranial irradiation was the most detrimental risk factor in absolute values of physical dysfunction, though this cohort was small.

Studies Within Specific Diseases

Along with recent studies across diagnoses, large sample or case-control studies have helped to clarify functional deficits in survivors within specific diagnoses. Not surprisingly, given the large population of breast cancer survivors, these have been the most studied. Long-term breast cancer survivors have increased physical impairment and symptoms, but not consistently poorer psychosocial or work function.16–18 In what to our knowledge was 1 of the earliest large cross-sectional studies of survivors 1 to 5 years after the diagnosis of stage I or II breast cancer who were disease-free, Ganz et al.16 reported that the most frequent physical symptoms were general aches and pains (70%), muscle stiffness (64%), and joint pain (62%). Women who were prematurely postmenopausal and those who received chemotherapy had a higher risk of sexual dysfunction. In a follow-up evaluation when these women were 5 to 10 years after diagnosis, most women continued to function well.17 Energy levels remained unchanged, while sexual activity declined over time. Most menopausal symptoms declined, but cognitive complaints increased. Without comparison to women who have not had breast cancer, it is not possible to know the extent to which these changes are age-related versus disease-related.

Studies have compared breast cancer survivors with controls and essentially confirmed elevated rates of functional deficits in survivors. A prospective investigation used data from the Nurses’ Health Study to document change over a 4-year period in women who were and were not diagnosed with breast cancer between the initial and follow-up assessments.19,20 Those diagnosed with breast cancer had higher rates of decline in physical function, vitality, and social function, along with increases in pain compared with women not diagnosed with cancer, even controlling for baseline abilities, other comorbid conditions, age, education, race, and lifestyle factors. Women aged ≤40 years had the largest declines in these areas of function.20 Although problems decreased with time from diagnosis, the deficits remained up to 4 years later. Investigators consistently note that the most prevalent physical deficits in breast cancer survivors are musculoskeletal problems.21 Meanwhile, increasing physical activity levels after diagnosis has been associated with improved long-term function.22

For long-term survivors of prostate cancer, general physical function appears to be unaffected by treatment type, with the exception of androgen deprivation. Conversely, sexual dysfunction occurs in most men with prostate cancer and is usually severe in men receiving androgen deprivation or other neoadjuvant treatment.23–26 Urinary obstruction, urinary incontinence, and bowel urgency also occur in survivors at rates greater than controls.23–25 Even men using watchful waiting indicate an elevated rate of these problems, pointing out that either the disease itself or reactions to the disease can have effects independent of those caused by treatments.25 Uncommon among survivorship studies, several prostate cancer cohorts have been followed over time, permitting evaluation of decline or comparison of recovery of function between treatment types. These studies indicate that survivors improve over time in urinary obstruction and bowel symptoms, but worsen in urinary incontinence and sexual function.23,24

Perhaps because myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) provides chemotherapy at very high doses and is used on some of the youngest survivors, this group of long-term survivors has received more study than many other diagnostic groups. Physical recovery occurs for most by 1 year after treatment and then remains fairly stable through 5 years.27 Despite good physical function in at least 75% of long-term survivors, recent late follow-up case-control studies have documented increased numbers of health problems, along with poorer physical function, in these long-term survivors relative to controls.28–30 Syrjala et al.30 reported that among 10-year survivors the greatest impairments relative to matched controls were in general health and physical activities rather than in psychosocial function. Sexual dysfunction, cognitive concerns, and musculoskeletal symptoms (even after eliminating survivors with avascular necrosis) were most prevalent. Although 20% of survivors expressed concern about cognitive function, the long-term deficits among the HSCT recipients appeared to predate transplantation.31 Adult survivors of childhood HSCT also have endorsed higher rates of physical and activity participation restrictions than young adults without a history of cancer.32

Cohort or case-control studies of long-term survivors with other diagnoses are less common and have tended to represent smaller sample sizes. After testicular cancer, surveys have found slight, if any, differences between survivors and norms in most physical domains, although vitality and social function remained lower in long-term survivors, while they reported more pain.33 These differences were small, however, and were not thought to be clinically meaningful. In comparing treatment types, those who received orchiectomy alone, without chemotherapy or radiation therapy, reported better sexual function, although all groups treated had changes in gonadal function.33,34 After non-Hodgkin lymphoma, fatigue is 1 of the most prevalent long-term functional complications, and this may in part result from not returning to prediagnosis levels of physical activity despite overall good health.35 Among long-term cervical cancer survivors, sexual function has been the primary problem evaluated. Survivors receiving radical hysterectomy did not differ from controls in either sexual function or physical function, but those who received radiotherapy reported poorer function in both areas, along with more menopausal symptoms.36,37 For colorectal survivors, 1 follow-up of a large cohort of women with mean age of 72 years and mean survival length of 9 years documented no physical function differences between survivors and age-matched norms.38 Not surprisingly, physical function declined as age and comorbidities increased. Because only broad QOL endpoints were measured, specific problem domains such as sexual, urinary, or bowel function could not be evaluated. To our knowledge, few long-term physical deficits have been reported among melanoma survivors.39 This may reflect the finding that most long-term survivors of melanoma have had local disease with only surgical excision, without radiation or systemic treatment. For those with local disease treated with isolated limb perfusion, physical problems are limited to limb stiffness, edema, and other difficulties with limb function in about half of the survivors.40 Although lung cancers are some of the most commonly diagnosed, rates for 5-year survival have remained lower than for other primary sites. Possibly for this reason, few studies of long-term survivors have been reported. In a review of 5-year survivorship results, Sugmura and Yang41 found that a quarter of these long-term survivors had major physical limitations.

Risk Factors and Mechanisms for Physical Dysfunction

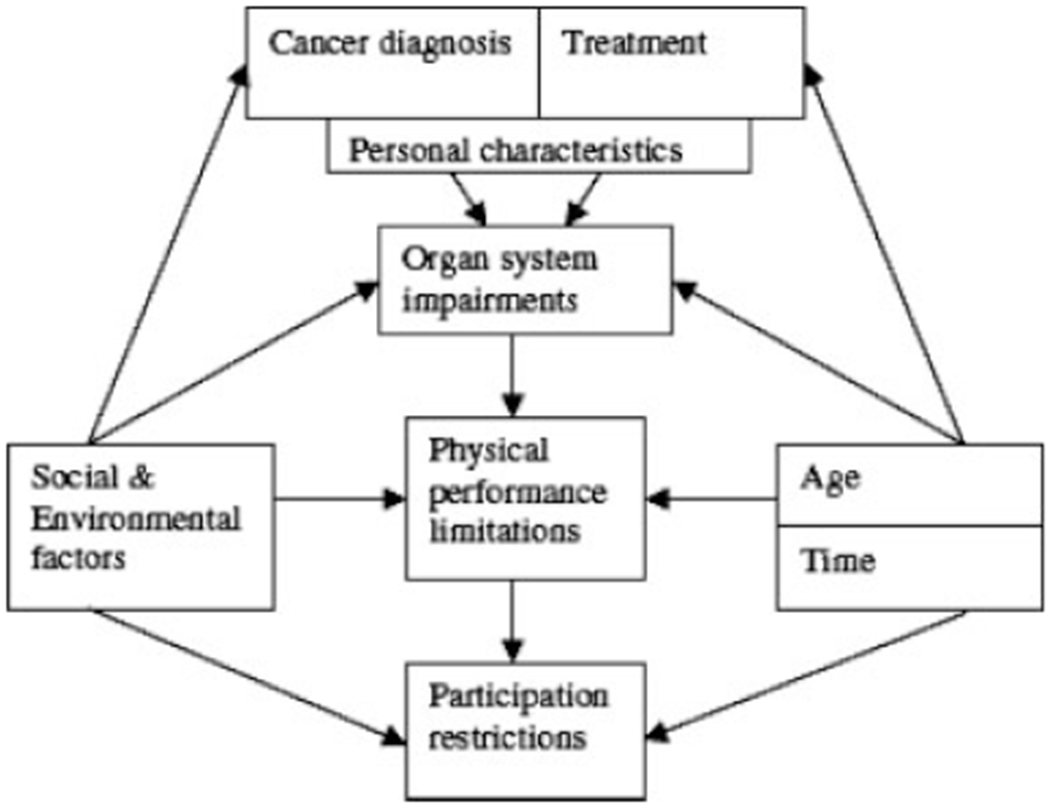

Risk factors for long-term or late effects can vary by diagnosis, type of treatment received, age at treatment, time since treatment, genetic vulnerability, as well as psychological, social, and environmental factors that influence functioning (Fig. 1). In considering differences by diagnosis, CNS and bone cancers are associated with greater risk of physical impairments.11,15 Conversely, cervical, testicular, and melanoma cancer survivors have fewer functional deficits.33,36,39 Risk of physical deficits varies dramatically by type of treatment. For instance, androgen deprivation used for prostate cancer results in high rates of physical and sexual problems. Alkylating agents and pelvic irradiation cause premature gonadal failure, which in turn can result in sexual problems along with increased risk for musculoskeletal complications.30 Treatment alone, however, does not dictate outcomes. Physical function and late complications can be influenced by lifestyle, socioeconomic, and biologic factors. As examples, exercise may strongly influence not only fatigue but also other components of physical and mental health.22,42 Lower income is 1 of the more consistent risk factors for functional outcomes.11 Being female, lower education level, and premature menopause have documented impact on specific deficits.11,12,15–17 Although progress is being made in understanding the influence of specific risk factors on distinct outcomes, clinical trials are needed to define interventions that reduce deficits in high-risk individuals.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model of physical performance limitations causes and effects. Reprinted with permission from Ness KK, Wall MM, Oakes JM, et al. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: a population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:197–205. © Elsevier 2006.

Research Needs

In the past few years, outcomes research has made considerable advances in documenting the physical deficits and needs of cancer survivors. The research methods of these studies, however, have limited some of the conclusions that can be drawn from their results. Much of the research to date has employed cross-sectional cohorts of cancer survivors of varying times since diagnosis and usually within specific cancer types. Still lacking are longitudinal studies that explore whether long-term survivors maintain their physical abilities or decline over time at a more rapid pace than nonsurvivors. Differences in incidence rates of physical impairments over time since treatment may be because of historical changes in treatments over the years or other changing risk factors. For example, the longest survivors of HSCT received single-dose total body irradiation, known now to have greater long-term toxicity than the fractionated doses currently used. Similarly, adult survivors of childhood leukemia received cranial irradiation at a higher frequency than current protocols prescribe, increasing rates of residual cognitive deficits in these long-term survivors. Because treatment regimens will continue to change, our knowledge of long-term and late effects will always lag behind our abilities to answer the questions of patients and clinicians. Nonetheless, longitudinal research is essential to improve modeling of risk factors, in addition to the obvious need for long-term treatment studies to evaluate decrements in survivor functioning.

Another limitation in survivorship research on physical function is the dependence on self-report of physical capacity. Long-term survivors for most diseases are geographically dispersed. The cost and time needed to provide objective testing of abilities can be prohibitive and difficult to fund. This dependence on reporting of known problems through remote contacts by mail, phone, or Internet responses does not address the potential for undetected problems in survivors. For instance, if survivors are not challenging themselves to participate in stamina- or strength-based activities, or are not sexually active, they may be unaware of problems, in the same way that they may be unaware of late medical complications. In addition, enrollment criteria commonly exclude those with limited verbal skills or non-English-speaking survivors. Translation and validation of measures that are sensitive to survivorship outcomes are needed to permit inclusion of these populations.

Another research barrier to determining the mechanisms for survivor outcomes is the cost and mechanics of acquiring medical records and true baseline information to provide accurate risk factor modeling. Furthermore, true baselines can predate cancer treatment for many problems that have behavioral or nonmedical components. For example, data regarding prediagnosis physical capabilities, sexual function, and cognitive function are rarely available, yet can be important predictors of later function.

Problems with inconsistencies in measurement and lack of appropriate, sensitive measures for survivorship research in physical function domains further restrict our ability to build models for risk factors and to determine mechanisms for survivor deficits. The most widely used and standardized cancer-specific measures of function and symptoms are designed for use during the acute treatment period. Generic, non-disease-specific measures of health-related QOL with population-based norms, such as the widely used SF-36, often do not have the sensitivity to capture specific deficits reported by survivors.

A final challenge to note in conducting studies that investigate physical functioning among cancer survivors is selecting appropriate nonsurvivor control cohorts. For purely biologic outcomes, siblings have been used with some confidence. In many cases, physical function deficits are determined by both biologic and behavioral or psychosocial factors. Thus, both sibling and friend cohorts can be suspect for potential biases from going through the cancer experience. Population norms have some appeal for their presumed noncontamination and unbiased representation of a definable sample. However, cancer survivor samples may not be normally distributed within a national population by age, sex, race, or ethnicity, prediagnosis comorbidities, or economic resources, among other factors. Because access to healthcare is not normally distributed in the population of the U.S., and treatment may also not be normally distributed, what constitutes a proper control cohort is still a matter of some debate.

A next step in needed research is to move from defining deficits to determining mechanisms for known persistent dysfunction, which can then inform the design of clinical trials to improve function. Studies currently under way are investigating not only biomarkers and mechanisms, but also methods to reverse these functional deficits.

Summary of Physical Outcomes in Survivors

Available data clearly document that a majority of cancer survivors describe good general health 5 years or more after treatment. Nonetheless, specific physical impairments have sustained impact on the function and QOL of many survivors. Frequent problems include fatigue or lack of stamina, musculoskeletal problems, decreased participation in activities, and sexual dysfunction. Long-term physical and functional effects that do not resolve with time vary by disease and treatment, with a few treatments clearly impairing long-term health, but many not differing markedly. The clearest demographic risk factors for these deficits are age and income. It remains to be determined whether physical function declines over time in survivors more rapidly than in noncancer populations reflecting an accelerated aging process, and to discover mechanisms for physical impairments that could improve targeted interventions to enhance long-term function in survivors.

Psychological Long-term and Late Effects of Cancer

Distress is a generic term that encompasses a variety of psychological responses, including depression and anxiety. The experience of distress after a cancer diagnosis is not unexpected, nor is it unusual for cancer patients to experience distress during treatment. Because this distress is temporally linked to cancer diagnosis and treatment, it is considered an ‘acute’ effect of cancer diagnosis and treatment. What we are interested in here, however, is distress that represents a long-term or late effect of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

As noted earlier, ‘long-term’ psychological effects refer to psychological or emotional responses that emerge after cancer diagnosis or during cancer treatment and persist for at least 5 years. In contrast, psychological ‘late effects’ refer to psychological or emotional responses that emerge after treatment completion. Several things should be noted here.

First, psychological late or long-term effects refer to responses that are primarily psychological or emotional in nature. Although anxiety or depression clearly fit this definition, other potential long-term or late effects of cancer, including fatigue, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbance, or cognitive impairment, likely do not. Although all of these can certainly be significant problems in cancer patients and survivors, they do not meet our definition of psychological long-term or late effects and thus will not be considered here.

Second, psychological long-term or late effects are attributable to the cancer experience. Because anxiety and depression are common in the general population, their presence in a cancer survivor does not necessarily suggest a long-term or late effect of cancer. Again, there is considerable gray area here as attribution of a psychological condition, such as anxiety or depression, to cancer diagnosis and treatment can be difficult.

Third, although anxiety or depression are most commonly brought to mind when psychological long-term or late effects of cancer are considered, psychological late or long-term effects of cancer may also include positive responses to cancer diagnosis and treatment. These include enhanced self-esteem, greater life appreciation and meaning, heightened spirituality, and greater feelings of peace and purposefulness.32,43,44 These positive long-term or late effects can be viewed as benefits of cancer diagnosis and treatment and are often characterized as post-traumatic growth.45–48

Finally, although we have drawn a distinction between ‘long-term’ and ‘late’ psychological effects, the research literature generally has not. For example, although estimates of the prevalence of depression in cancer survivors are often reported, typically little attention is given to whether depression was also present before diagnosis (ie, a premorbid condition and thus not a long-term or late effect of cancer), emerged at the time of diagnosis and treatment and has persisted (ie, a long-term effect of cancer), or whether depression initially developed after treatment completion and was attributable to an individual’s cancer experience (ie, late effect of cancer). Consequently, the technical distinction between psychological long-term and late effects is generally blurred in the research literature. To simplify matters, and in recognition of our belief that most psychological effects evident in cancer survivors represent persistence of a response that first emerged at the time of diagnosis and treatment, we will use the term psychological long-term effect from this point forward.

Psychological Long-term Effects of Cancer: Prevalence

How common are the psychological long-term effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment? The prevalence of depression in cancer survivors has been estimated to range from 10% to 25%,49 20% to 50%,50 and 0% to 58%.51 The prevalence of anxiety disorders has been estimated to be 6% to 23%,52 and the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been estimated to be 0% to 32%.53 These wide-ranging prevalence estimates suggest no facile answer to the seemingly simple question of the prevalence of psychological long-term effects of cancer.

In part, these wide-ranging estimates reflect the difficulty in identifying the prevalence of psychological long-term effects. Identification of the prevalence of a specific long-term effect requires a researcher to define that long-term effect operationally. This definition then enables the researcher to determine whether or not that specific long-term effect is present in a study participant. Unfortunately, the literature examining the prevalence of psychological long-term effects in cancer survivors evidences a distinct lack of consensus regarding how to define these effects. For example, some studies of the prevalence of depression in cancer survivors employ formal diagnostic criteria, whereas other studies define the presence of depression in terms of a cutoff score on a questionnaire or rating scale. In some instances the validity of a ‘cutoff’ score has been established; in others, cutoff scores are used on an ad hoc basis with little empiric justification. In short, the presence of a particular psychological long-term effect, such as anxiety or depression, is defined in different ways in different studies. This compromises comparison of prevalence estimates for a specific long-term effect across studies and contributes to the wide range of prevalence estimates found in the literature.

This lack of definitional consensus is particularly pronounced for positive psychological long-term effects. The nomenclature and measurement operations associated with positive psychological long-term effects are woefully underdeveloped. For example, currently nothing remotely representing a consensus has emerged regarding how to define the presence or absence of potential long-term effects such as ‘enhanced self-esteem,’ ‘a greater sense of peace or purposefulness in life,’ or ‘heightened spirituality.’ Consequently, the prevalence of these potential long-term effects in cancer survivors is largely unknown.

Wide variability in prevalence estimates for psychological long-term effects also stems from variability in case mix both within and across study samples. Risk for a specific psychological long-term effect can vary by cancer, disease stage at diagnosis, treatment received, age, race and ethnicity, sex, developmental stage at diagnosis, and timepoint in the cancer trajectory when long-term effects are assessed. Consequently, prevalence rates can differ widely across studies simply as a function of the variability present with respect to these demographic and clinical characteristics.

Despite these caveats regarding prevalence estimates for psychological long-term effects, some simple generalizations can be offered. First, the absence of an appropriate taxonomy and set of definitional criteria make it impossible to estimate the prevalence of positive psychological long-term effects in cancer survivors. Although ample research has demonstrated that many cancer survivors report that their cancer experience positively affected their life,48 we have no good idea of how frequently they are present. Second, serious psychiatric disorders, such as major depression or PTSD, are generally uncommon in cancer patients and survivors.54 Nonetheless, compared with the general population, cancer patients and survivors appear to possess at least slightly higher risk for major depression and PTSD. For example, Polsky et al.55 found that a cancer diagnosis within the past 2 years increased the risk of reporting significant depressive symptoms 3-fold to 4-fold relative to individuals with no cancer diagnosis. A nearly 2-fold increase in risk for reporting significant depressive symptoms was found in survivors 4 to 8 years postcancer diagnosis.

Furthermore, certain subgroups appear to be particularly vulnerable to psychological long-term effects. For example, survivors of hematopoietic and head and neck cancers may be particularly vulnerable to PTSD,56,57 whereas head and neck cancer survivors may be particularly vulnerable to major depression.58

Third, less severe ‘adjustment’ disorders, characterized as evidencing either a depressed or anxious mood or a mixture of both, are a fairly likely consequence of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Derogatis et al.54 reported a 32% prevalence rate for adjustment disorders in a heterogeneous group of cancer patients. How this compares to the prevalence of adjustment disorders in the general population is difficult to gauge, however, because to our knowledge large-scale epidemiologic surveys of psychiatric disorder have typically not included adjustment disorders.59 Adjustment disorders are generally mild and transitory and are particularly likely in the immediate aftermath of a cancer diagnosis or relatively early in the cancer trajectory. Such adjustment disorders should not, however, be considered psychological long-term or late effects of cancer unless they persist (ie, long-term effect) or initially appear (ie, late effect) well beyond the conclusion of treatment.

Many disease-free cancer survivors experience anxiety over the possibility of a cancer recurrence.60 To our knowledge, fear of recurrence has not been extensively studied as a potential psychological long-term effect of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Although self-report inventories to measure fear of cancer recurrence have been developed,61 to our knowledge no agreement exists regarding how to define a ‘fear of recurrence’ for purposes of estimating its prevalence in cancer survivors. Although some fear of cancer recurrence is normal in cancer survivors, a fear of recurrence that is severe and persistent can significantly impact QOL and diminish everyday functioning. There is likely some merit to developing specific criteria for defining such instances of ‘abnormal’ (pathologic) fear of recurrence for purposes of estimating its prevalence. Until consensus is developed regarding the defining characteristics of ‘fear of recurrence’ as a long-term effect of cancer, however, it is impossible to estimate its prevalence in cancer survivors.

Feeling one’s future may be cut short is a central element in the fear of cancer recurrence. It is also a defining symptom used to diagnose PTSD. Although 1 study found that 32% of cancer survivors experience PTSD after the completion of cancer treatment,53 the majority of studies suggest prevalence rates in cancer survivors in the range of 5% to 15%. The prevalence of cancer-related PTSD appears to exceed the base rate of PTSD in the general population, estimated to be in the range of 1% to 4%.62,63 However, to our knowledge, few studies to date have employed formal diagnostic criteria for PTSD and examined long-term cancer survivors, so existing research is limited with regard to the information it provides regarding PTSD as a long-term effect of cancer. A study employing formal PTSD criteria in women who were a mean of 3 years after breast cancer diagnosis demonstrated prevalence rates of 6% and 10% for current and lifetime cancer-related PTSD, respectively.64 A similar study of head and neck cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis demonstrated a PTSD prevalence rate of 14%.57 Although application of the PTSD concept to understanding psychological response to cancer diagnosis and treatment is not without difficulty,53 cancer survivors clearly can evidence a constellation of distressing symptoms associated with PTSD long after cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Finally, it is important to note that the cancer experience is dynamic over time. The physical, psychological, social, and existential stressors associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment today might be markedly different from those associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment tomorrow. Consequently, the spectrum and prevalence of psychological long-term effects, both negative and positive, associated with a specific constellation of disease, treatment, and patient characteristics may change with the passage of time. To appreciate this assertion, one might consider how the experience of breast cancer has changed over the past 50 years. Early reports from the 1950s of the psychological impact of breast cancer stressed the potential for anger, anxiety, depression, helplessness, stigma, and social isolation.65 Today, 50 years later, one is equally likely to hear the psychological impact of breast cancer described in terms of opportunity, empowerment, and social connection.66,67

Psychologic Long-term Effects of Cancer: Associated Factors

Nearly all individuals experience some psychological disequilibrium at the time of the initial diagnosis and treatment. Most will eventually recover from their cancer experience, regain their psychological equilibrium, and evidence few significant late or long-term effects, either positive or negative. For other individuals, however, the cancer experience has a more profound impact. For some, the diagnosis of cancer initiates a downward spiral of psychological and social impairment. For others, the diagnosis of cancer may also initiate an upward trend characterized by enhanced psychological and social adjustment.

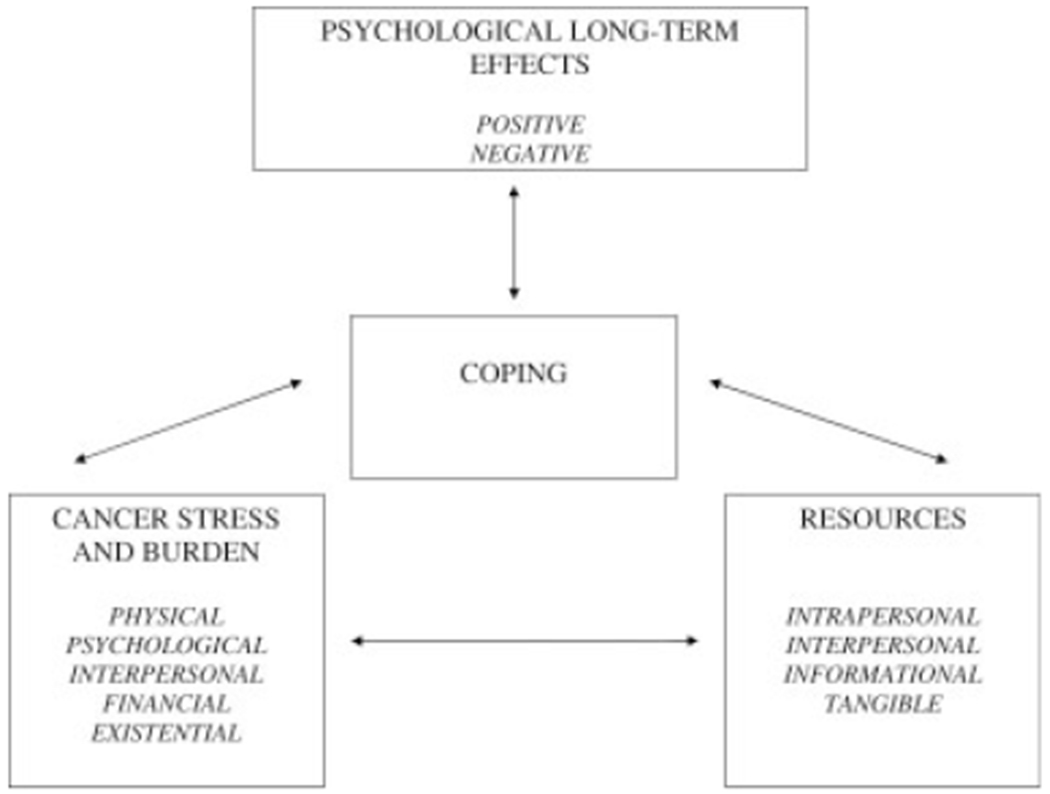

Identification of the factors that influence the trajectory and ultimate equilibrium of psychological adjustment evidenced by a cancer survivor is a distinct challenge. At the risk of oversimplifying matters, psychological response to the cancer experience can be seen as influenced by 2 classes of variables: the stress and burden posed by the cancer experience and the resources available to an individual (Fig. 2). The interaction between cancer stress and burden and the resources available to an individual influences how, and how well, an individual copes with their cancer experience. How an individual appraises his or her cancer experience and the specific coping strategies he or she employs (eg, approach- or avoidance-oriented) are determined by the particular stresses confronted as well as the resources available. How, and how well, an individual copes with his or her cancer experience then influences risk for psychological long-term effects in cancer patients and survivors. In general, the relative balance of resources vis-à-vis cancer stress and burden determines the individual’s psychological response in both the short- and long-term. All things being equal, the greater the stress and burden posed by the cancer experience, the greater the risk for negative long-term psychological effects. Conversely, the greater the resources available, the lower the risk of negative long-term effects.

FIGURE 2.

Factors associated with psychological late effects in cancer survivors.

Several points are worth noting. First, both resources and cancer stress and burden can fluctuate across time, so the balance between them is dynamic. Just as 1 or both factors can increase or decrease over time, so also the profile of positive and negative psychological long-term effects experienced by an individual may fluctuate over time. Second, an individual might be at high risk for negative psychological long-term effects even when cancer stress or burden appears to be low. This might result if resources were also low. Conversely, an individual might be at low risk for negative psychological long-term effects even when cancer stress or burden appears to be considerable. This might result if available resources were also considerable. Finally, the correlations between cancer stress and burden, on the one hand, and the resources available to an individual can be bidirectional. The availability of suitable resources can affect cognitive appraisals and thus reduce stress and burden. Conversely, greater stress and burden can influence the resources available. For example, a survivor who is experiencing a high level of cancer stress and burden might be limited in his or her capacity to receive and process important disease or treatment-related information or might discourage supportive responses from his or her social environment.

Several other aspects of our heuristic model for understanding factors associated with long-term psychological effects should be noted. First, cancer stress and burden is multifaceted. Cancer patients and survivors confront stressors that may be physical, psychological, interpersonal, financial, or existential in nature. Consequently, understanding of an individual’s risk for negative psychological long-term effects should incorporate relevant information from each of these domains. Second, the concepts of ‘stress’ and ‘burden’ are subjective. The experience of certain physical late or long-term effects, such as infertility, fatigue, or weight gain, may be experienced as highly stressful by some cancer survivors but much less stressful by others. Similarly, a poor prognosis may be a persistent source of dread for some cancer survivors, whereas others are more sanguine when faced with a similar prognosis. Consequently, understanding of an individual’s risk for negative psychological long-term effects must include not just an objective account of the stresses posed by his or her cancer experience but must also account for the individual’s subjective response to those presumed stressors (ie, cognitive appraisal).

Finally, the stress and burden posed by the cancer experience is dynamic and fluid across time. Early in the cancer trajectory, the stress of the cancer experience might be primarily characterized by the existential threat posed by a potentially life-threatening illness, difficulties involved in making treatment decisions under uncertainty, recovery from cancer surgery, and anxiety regarding response to adjuvant treatment. Later in the cancer trajectory the stress of the cancer experience might be primarily characterized by fear of cancer recurrence, financial difficulties resulting from high medical care costs and/or reduced income, difficulties with sexuality and intimacy, or recognition of physical long-term or late effects of treatment. Consequently, understanding of an individual’s risk for psychological long-term effects is based on knowledge of how the specific stresses and burdens confronting a cancer survivor evolve over time, resulting in a waxing and waning of specific concerns.68

The resources available to the cancer patient and survivor are also multifaceted. These resources can be grouped into 4 general categories: intrapersonal, interpersonal, informational, and tangible.

Intrapersonal resources consist of internal, personal characteristics. These can be dispositional in nature and reflect general tendencies to think or act in certain ways. Their presence might result in better coping, while their absence might be associated with poorer coping. Examples of intrapersonal resources that have shown some empiric linkage to better psychological adjustment in cancer survivors include optimism,69–71 self-efficacy,72,73 emotional intelligence,74 and spirituality.75,76

Social support is an interpersonal resource that has been linked to better short- and long-term psychological outcomes in cancer patients and survivors.77 Better coping with the stresses and burdens posed by the cancer experience is fostered when the individual is embedded within a supportive social environment, one which facilitates the individual’s attempts to cognitively and emotionally process his or her experience.78 Although most attention has been focused on social support as a facilitating factor in the coping process, the role that social constraints might play in impeding the coping process has also been examined.74,79 Social constraints represent efforts by individuals to actively prevent or inhibit a cancer patient or survivor from talking about or psychologicalally confronting his or her cancer experience. The presence of such social constraints may inhibit social and emotional processing that is believed to be critical to the coping process, and would thus be considered a risk factor for negative psychological long-term effects.

Informational resources are also linked to risk for long-term psychological effects. For cancer patients and survivors, access to accurate and understandable information regarding their disease, treatment options, treatment side effects, prognosis, and support services in the community is a valuable resource. Greater educational attainment is often linked to better psychological adjustment in cancer survivors.80–82 More educated individuals might elicit more information from their care providers, be more likely to seek information, or better understand the information provided to them. Information might also foster appropriate expectations regarding long-term recovery. Inappropriate, unrealistic expectations regarding long-term or late effects and the trajectory of recovery could increase risk negative long-term psychological effects.83

Interestingly, it may not always be the case that “knowledge is power.” Individuals differ in their preferences with regard to the type, amount, and depth of information with which they are comfortable. People differ with regard to whether they are a ‘monitor’ or ‘blunter’ in a situation of threat or uncertainty.84 Monitors tend to actively seek information and are comfortable with efforts to provide them with as much information as possible. Blunters prefer to avoid information and consequently are less comfortable with large amounts of information. Thus, although information might enhance coping and reduce risk for negative long-term effects for some, the same information might increase distress and increase risk for negative long-term psychological effects for others.

Finally, coping with cancer stress and burden is facilitated by access to tangible resources. Cancer patients and survivors receive their medical care in a variety of settings, including academic medical centers, community hospitals, and private physicians’ offices. Special clinics devoted to the medical and support needs of cancer survivors have also been developed.85,86 The type, extent, and quality of psychological support services that are available to cancer patients and survivors differ across these diverse treatment settings. Available support services may include licensed therapists and social workers, support groups, formal ‘navigator systems,’ or informal peer-to-peer networks. Poorer access to these support services, as well as other mental health resources available in the community, is likely associated with greater risk for negative psychological long-term effects. Although money can not buy happiness directly, money can facilitate access to resources (eg, education, vocational retraining, mental health services, child care, personal assistance, and housekeeping assistance) that can foster better coping cancer stress and burden and ultimately impact risk for psychological long-term effects.

In summary, the risk for psychological long-term effects, both positive and negative, varies widely across cancer survivors. A considerable amount of research has attempted to link a variety of demographic, clinical, dispositional, psychosocial, and health system variables to long-term adjustment outcomes (ie, psychological long-term effects). In general, the focus of attempts to identify ‘risk factors’ for psychological long-term effects in cancer survivors has focused on negative long-term effects, with a much smaller but growing literature seeking to identify ‘risk factors’ for positive long-term effects. The results of this research can best be described as mixed, with few individual variables possessing strong predictive power in isolation. Rather, risk for specific psychological long-term effects is likely a result of a combination of factors. In general, risk for psychological long-term effects is determined by the balance between cancer stress and burden and the resources available to an individual to cope with this stress and burden.

Finally, the risk for positive and negative long-term effects are likely not the obverse of each other. For example, although lack of social support has been linked with poor short- and long-term psychological outcomes, it does not automatically follow that provision of adequate social support enhances the likelihood of positive psychological long-term effects. ‘Risk’ for positive long-term effects may be determined by factors that differ from those that determine risk for negative long-term effects.

Psychological Long-term Effects of Cancer: Research Needs

Research on late and long-term effects psychological effects of cancer has as its ultimate goal the minimization of distress and the maximization of well-being in cancer survivors. To achieve this goal, cost-effective approaches to the clinical management of cancer survivors must be developed and disseminated. To minimize distress, effective strategies for preventing distress from developing or managing distress when it is already present must be developed and evaluated. There already exists a large literature that has examined the efficacy of a host of interventions for minimizing distress in cancer patients and survivors.87,88 Although the results are decidedly mixed, they are promising. To make use of these cost-effective interventions, it will be necessary to streamline them and target them toward survivors who are most at risk for significant distress at the specific points in the cancer trajectory when survivors are likely most vulnerable. To achieve this goal, cost-effective approaches to distress screening in cancer survivors must be developed. Several approaches to distress screening have been developed,89,90 but they remain to be further field-tested and refined. To identify individual risk factors for distress and specific points of vulnerability in the cancer trajectory, more and better longitudinal descriptive research is necessary. In particular, it is critically important that research employs well-defined and well-validated criteria for identifying the presence or absence of specific psychological late or long-term effects, both negative and positive.

Finally, although the majority of research to date has focused on distress and management of distress, future research is advised to consider how well-being might be enhanced in cancer survivors. Based on the premise that well-being is more than the absence of distress, specific strategies for enhancing well-being in cancer survivors should be developed, evaluated, and ultimately targeted toward those survivors most likely to benefit. Although several promising studies have appeared recently,91,92 research designed to enhance well-being in cancer patients or survivors is in its infancy. Researchers in this field are advised to consider insights and experience available in the growing field of ‘positive psychology.’93

Conclusions and Future Directions

In this article we have discussed the prevalence, risk factors or associated factors, and impact of physical and psychological long-term and late effects among adult survivors of pediatric and adult cancers. In addition, we have attempted to highlight some of the important issues and challenges inherent in measuring such effects. A thorough review of the strategies that have been used in the management of these outcomes and the efficacy of such interventions is outside the scope of this article. We would, however, like to call attention to several varied yet potentially synergistic initiatives designed to increase awareness and understanding of these issues and to generate a groundswell of interest and activity to address them in the public domain.

One such example is a recent invitational symposium focusing solely on the long-term sequelae of cancer and cancer treatment, jointly sponsored by the American Journal of Nursing, the American Cancer Society, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS), and the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. This symposium examined the state of the science regarding long-term and late effects of cancer, identified gaps and barriers to the management of long-term and late effects, and formulated a set of recommendations and strategies aimed at addressing these problems. One key recommendation of the symposium was that more research was needed to further document the prevalence of long-term and late effects on a nationally representative level; identify the medical, sociodemographic, and psychosocial factors associated with the development of long-term and late effects; and assess the overall impact of long-term and late effects on cancer survivors’ QOL.94

In keeping with this recommendation is the development and implementation of several large-scale national research projects with cancer survivors. Although some of these efforts aim to document the physical and psychological functioning of cancer survivors, others focus on the quality-of-care issues that impact such functioning. Specifically, the American Cancer Society’s Behavioral Research Center has implemented a program of research, collectively referred to as the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors (SCS), that includes longitudinal, cross-sectional, and cancer caregiver components.95,96 By sampling survivors from 25 population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) cancer registries in 21 states, stratifying by cancer type and time since diagnosis, and oversampling younger (those aged <55 years) and minority cancer survivors, the SCS aim to produce self-report data that is more representative of the population of cancer survivors than are typically available from convenience samples.

In addition, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) has been active in both funding and, in some cases, conducting several large population-based research projects that are relevant to the study of long-term and late effects of cancer. Foremost among them is the previously mentioned Childhood Cancer Survivors Study (CCSS), which has followed a large cohort of survivors of pediatric cancers for more than 10 years. CCSS has produced over 60 published articles and reports, several of which have become seminal articles in the documentation of long-term and late effects among survivors of childhood cancer.10,13,97–102 Other NCI studies have focused on adult cancer survivors, including the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study (PCOS),103 which assessed QOL outcomes in a large, heterogeneous cohort of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Data from PCOS has been used to document sexual functioning deficits among survivors of prostate cancer at 5 years after diagnosis.104 In addition, along with the Department of Veterans Affairs, the NCI is conducting the Cancer Care Outcome Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) study,105 a multisite longitudinal study of the processes and outcomes of cancer care among persons diagnosed with lung and colorectal cancer. The CanCORS study has several components that could inform our understanding of the factors that contribute to long-term late effects of cancer, including a longitudinal patient survey, a proxy or surrogate survey for ill participants and early decedents, a caregiver survey, a provider survey, linkages with publicly available datasets, and detailed medical record review.

However, even such large-scale studies as SCS, CCSS, PCOS, and CanCORS cannot address the need to monitor trends in functioning among new groups of cancer patients and survivors going forward. That is, because these studies are based on single samples of patients/survivors, they will not be able to document changes in rates of late effects that occur as standards of care change over time and our ability to manage the effects of cancer improve. Population-based monitoring of late effects would best be achieved by a surveillance system that periodically drew new samples of cancer patients that would allow for the documentation of these changes. To accomplish these surveillance goals, national systems for monitoring the physical, emotional, and social functioning of cancer survivors will need to be developed and maintained. Increasingly, the establishment of such surveillance systems is being called for by the research community94 and public health entities, as evidenced by the adoption of a nationwide objective of the American Cancer Society to have national cancer surveillance systems that allow for the monitoring of the physical and emotional functioning of cancer survivors in place by the year 2015.106 Clearly, this is an ambitious goal, because many issues must be addressed, including securing funding for the initial start-up and maintenance of such systems, generating support among researchers and public health organizations, and determining how the existing cancer surveillance infrastructure can be augmented and incorporated into the plan. Despite the challenges, such a surveillance system would provide a mechanism with which to document successes and challenges in improving the QOL of cancer survivors, including the management and prevention of long-term and late effects.

Another emerging approach to the identification, surveillance, and management of survivorship issues is the development of a survivorship care plan. This tool would allow cancer survivors to document the treatments they received and the health conditions such treatments place them at risk for. By sharing this information with their healthcare providers, survivors may be able to play an active role in anticipating and even preventing potential long-term and late effects of their cancer. Such survivorship care plans are among the many important recommendations in the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, which calls for survivors, family members, providers, and the healthcare system in general to be proactive in addressing the many issues that a person with cancer faces during the transition from being a cancer patient to becoming a cancer survivor.107 As suggested in the IOM report, the prescription for successful survivorship will have to be a multifaceted approach that includes research, education, advocacy, and community activism components. Ultimately, the aim of these efforts is to produce strategies to understand, monitor, and mitigate the impact of long-term and late effects of cancer.

Acknowledgments

Supplement sponsored by the American Cancer Society’s Behavioral Research Center and the National Cancer Institute’s Office of Cancer Survivorship.

Dr. Syrjala is supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA63030, CA78990, CA112631, and CA103728) and a Survivorship Center of Excellence grant from the Lance Armstrong Foundation.

We thank Leigh Boghossian, MPH, for assistance with literature review, article preparation, and editorial input.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ries LA, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2007]. Available at URL: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/ Accessed December 4, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries LA, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2002. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2005. Available at URL: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002 Accessed June 11, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabroff KR, McNeel TS, Waldron WR, et al. Health limitations and quality of life associated with cancer and other chronic diseases by phase of care. Med Care. 2007;45:629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ness KK, Wall MM, Oakes JM, et al. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: a population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006; 16:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney C, Schmitz KH, Lazovich D, et al. Functional limitations in elderly female cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keating NL, Norredam M, Landrum MB, et al. Physical and mental health status of older long-term cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2145–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidrich SM, Egan JJ, Hengudomsub P, et al. Symptoms, symptom beliefs, and quality of life of older breast cancer survivors: a comparative study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robison LL, Green DM, Hudson M, et al. Long-term outcomes of adult survivors of childhood cancer: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2005;104:2557–2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290:1583–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castellino SM, Casillas J, Hudson MM, et al. Minority adult survivors of childhood cancer: a comparison of long-term outcomes, health care utilization, and health-related behaviors from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6499–6507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M, et al. Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2527–2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helgeson VS, Tomich PL. Surviving cancer: a comparison of 5-year disease-free breast cancer survivors with healthy women. Psychooncology. 2005;14:307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michael YL, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, et al. The persistent impact of breast carcinoma on functional health status: prospective evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer. 2000;89:2176–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, et al. Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1849–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieboer P, Buijs C, Rodenhuis S, et al. Fatigue and relating factors in high-risk breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant standard or high-dose chemotherapy: a longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8296–8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendall AR, Mahue-Giangreco M, Carpenter CL, et al. Influence of exercise activity on quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1358–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2772–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galbraith ME, Arechiga A, Ramirez J, et al. Prostate cancer survivors’ and partners’ self-reports of health-related quality of life, treatment symptoms, and marital satisfaction 2.5–5.5 years after treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:E30–E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1773–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291:2335–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker KS, Gurney JG, Ness KK, et al. Late effects in survivors of chronic myeloid leukemia treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation: results from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2004;104:1898–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrykowski MA, Bishop MM, Hahn EA, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life, growth, and spiritual well-being after hemotopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Late effects of hematopoietic cell transplantation among 10-year adult survivors compared with case-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6596–6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syrjala KL, Dikmen S, Langer SL, et al. Neuropsychological changes from before transplantation to 1 year in patients receiving myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Blood. 2004;104:3386–3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ness KK, Bhatia S, Baker KS, et al. Performance limitations and participation restrictions among childhood cancer survivors treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the bone marrow transplant survivor study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mykletun A, Dahl AA, Haaland CF, et al. Side effects and cancer-related stress determine quality of life in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3061–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huddart RA, Norman A, Moynihan C, et al. Fertility, gonadal and sexual function in survivors of testicular cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Jones LW, et al. Differences in quality of life between non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors meeting and not meeting public health exercise guidelines. Psychooncology. 2005;14:979–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7428–7436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donovan KA, Taliaferro LA, Alvarez EM, et al. Sexual health in women treated for cervical cancer: characteristics and correlates. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trentham-Dietz A, Remington PL, Moinpour CM, et al. Health-related quality of life in female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2003;8:342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, et al. Health status of long-term cancer survivors: results from an Australian population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1969–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noorda EM, van Kreij RHJ, Vrouenraets BC, et al. The health-related quality of life of long-term survivors of melanoma treated with isolated limb perfusion. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:776–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugimura H, Yang P. Long-term survivorship in lung cancer: a review. Chest. 2006;129:1088–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, et al. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1588–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, Hunt J. Positive psychosocial adjustment in potential bone marrow transplant recipients: cancer as a psychosocial transition. Psychooncology. 1993;2:261–276. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bower JE, Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA, et al. Perceptions of positive meaning and vulnerability following breast cancer: predictors and outcomes among long-term breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellizi KM, Blank TO. Predicting posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2006;25:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordova MJ, Andrykowski MA. Responses to cancer diagnosis and treatment: posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2003;8:286–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cordova MJ, Cunningham LC, Carlson CR, et al. Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychol. 2001;20:176–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stanton AL, Bower JE, Low CA. Posttraumatic growth after cancer In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, eds. Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth; Research and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;2006:138–175. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pirl WF. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of depression in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasquini M, Biondi M. Depression in cancer patients: a critical review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stark DPH, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:499–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting D, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;49:751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polsky D, Dishi JA, Marcus S, et al. Long-term risk for depressive symptoms after a medical diagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1260–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Black EK, White CA. Fear of recurrence, sense of coherence, and posttraumatic stress disorder in haematological cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;14:510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. The course of psychological disorders in the 1st year after cancer diagnosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morton RP, Davies AD, Baker J, et al. Quality of life in treated head and neck cancer patients: a preliminary report. Clin Otolaryngol. 1984;9:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Casey P, Maracy M, Kelly BD, et al. Can adjustment disorder and depressive episode be distinguished? Results from ODIN. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee-Jones C, Humphries G, Dixon R, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence: a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology. 1997;6:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vickberg SM. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Clara I, et al. The relationship between anxiety disorders and physical disorders in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Stein MB, et al. Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behavior associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a large community sample. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andrykowski MA, Cordova MJ, Studts JL, et al. Diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder following treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bard M, Sutherland AM. Psychological impact of cancer and its treatment: IV. Adaptation to radical mastectomy. Cancer. 1955;8:656–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coreil J, Wilke J, Pintado I. Cultural models of illness and recovery in breast cancer support groups. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:905–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kinney CK, Rodgers DM, Nash KA, et al. Holistic health for women with breast cancer through a mind, body, and spirit self-empowerment program. J Holist Nurs. 2003;21:260–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andrykowski MA, Cordova MJ, Hann DM, et al. Patients’ psychosocial concerns following stem cell transplantation: findings from 2 transplant centers. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1121–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carver CS, Smith RG, Antoni MH, et al. Optimistic personality and psychosocial well-being during treatment predicit psychosocial adjustment among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2005;24:508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Curbow B, Somerfield MR, Baker F, et al. Personal change, dispositional optimism, and psychological adjustment in bone marrow transplantation. J Behav Med. 1993;16:423443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, et al. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:306–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Norton TR, et al. Cancer-specific self-efficacy and psychosocial and functional adaptation to early stage breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beckham JC, Burker EJ, Lytle BL, et al. Self-efficacy and adjustment in cancer patients: a preliminary report. Behav Med. 1997;23:138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmidt JE, Andrykowski MA. The role of social and dispositional variables associated with emotional processing in adjustment to breast cancer: an internet-based study. Health Psychol. 2004;23:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gall TL, Cornblat MW. Breast cancer survivors give voice: a qualitative analysis of spiritual factors in long-term adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11:524–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krupski TL, Kwan L, Fink A, et al. Spirituality influences health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychol. 1996;15:135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lepore SJ. A social-cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer In: Baum A, Anderson B, eds. Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association;2001:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Widows MR, Jacobsen PB, Fields K. Relation of psychological vulnerability factors to posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology in bone marrow transplant recipients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:873–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, Weiss RB, et al. Long-term adjustment of survivors of early-stage breast carcinoma, 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98: 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, et al. Psychological and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2003;12:183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]