Abstract

Background

orthostatic hypotension (OH) is highly prevalent in older populations and is associated with reduced quality of life and increased mortality. Although non-pharmacologic therapies are recommended first-line, evidence for their use is lacking.

Objective

determine the efficacy of combination non-pharmacologic therapy for OH in older people.

Methods

a total of 111 orthostatic BP responses were evaluated in this prospective phase 2 efficacy study in 37 older people (≥60 years) with OH. Primary outcome was the proportion of participants whose systolic BP drop improved by ≥10 mmHg. Secondary outcomes include standing BP and symptoms. Comparison is made to the response rate of the most efficacious single therapy (bolus water drinking 56%). Therapeutic combinations were composed of interventions with known efficacy and tolerability: Therapy A- Bolus water drinking + physical counter-manoeuvres (PCM); Therapy B- Bolus water drinking + PCM + abdominal compression.

Results

the response rate to therapy A was 38% (95% confidence interval – CI 24, 63), with standing systolic BP increasing by 13 mmHg (95% CI 4, 22). Therapy B was efficacious in 46% (95% CI 31, 62), increasing standing systolic BP by 20 mmHg (95% CI 12, 29). Neither therapy had a significant effect on symptoms. There were no adverse events.

Conclusions

in comparison to single therapy, there is little additional benefit to be gained from combination non-pharmacologic therapy. Focussing on single, efficacious therapies, such as bolus water drinking or PCM, should become standard first-line therapy.

Keywords: orthostatic hypotension, conservative treatment, clinical trial, phase 2, older people

Key points

There is little benefit to be gained from using non-pharmacologic therapies concurrently in older people with orthostatic hypotension.

Combination therapy is no better than using bolus-water drinking alone.

These results challenge current practise and have the potential to reduce poly-therapy and improve uptake and adherence.

Introduction

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is a disabling condition characterised by a significant drop in blood pressure (BP) upon standing upright [1]. It is particularly common in older people, but this group is usually excluded from research, leading to clinical uncertainty around its management.

Non-pharmacologic therapies are recommended as first-line treatment for OH. Bolus water drinking, abdominal compression and physical counter-manoeuvres (PCM) are efficacious for the treatment of OH associated with ageing, whereas lower limb compression is not [2]. Compression garments are also largely unacceptable to older people with OH, whereas bolus-water drinking and PCMs are well tolerated [3]. It is unknown whether there is any additional benefit to be gained by combining non-pharmacologic interventions.

Methods

Population

Participants were aged over 60 years and had OH according to standard criteria [1]. Participants were excluded if they had dysphagia, fluid restriction or were unable to wear abdominal compression.

Setting

Participants were recruited through a Falls and Syncope Service in North East England.

Interventions

The selection of non-pharmacologic interventions was based on the results of a recent phase 2 efficacy study, which determined the efficacy and tolerability of single interventions [2, 3]. Bolus water drinking and PCM were both efficacious and tolerable. Lower limb compression had poor levels of efficacy and was considered intolerable. Abdominal compression was efficacious but had mixed levels of acceptability. The following combinations were therefore evaluated:

Bolus water drinking + PCM

Bolus water drinking + PCM + abdominal compression

Room temperature tap water (480 ml) was consumed within 5 min. During PCM, participants were encouraged to stand cross-legged [4]. An elasticated belt was applied to the abdomen and pelvis providing 10 mmHg pressure at the beginning of supine rest [5].

Procedure

Study procedures were performed between 09:30 and 11:30 a.m. Participants refrained from caffeine, nicotine and eating on the morning of their assessment. All medications were withheld for ≥12 h before attending.

To describe the cohort’s characteristics medication use and co-morbidities were noted. The Charlson Comorbidity Score was calculated to illustrate the cohort’s level of co-morbidity. To describe the cohort’s level of frailty, dominant hand grip strength was quantified with a hydraulic hand dynamometer (Jamar).

To ensure that OH was present, participants underwent a control active stand during which they rested supine for 10 min, followed by standing upright for 3 min. Cardiovascular responses were measured using beat-to-beat monitoring (Task Force Monitor, CNSystems). Digital BP values were verified against a brachial artery oscillometric BP at outset.

A repeat active stand was performed for both combinations of interventions, as described above. Participants were randomised (by selecting an opaque sealed envelope) to the order in which they received intervention; A then B, or B then A. The vasopressor response to water peaks within a few minutes and remains elevated for over 1 h [6], allowing both combinations of therapy to be evaluated after a single bolus of water. Twenty minutes of quiet rest occurred between each intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the response rate to each intervention (defined as the proportion of participants whose systolic BP drop improved ≥10 mmHg).

Secondary outcomes included nadir standing systolic BP, BP drop and symptoms (Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire Symptom Assessment subscale (OHSA) [7]).

Analysis

Baseline BP was the average of the continuous BP values during the final 10 s of supine rest. An average BP was calculated for each 10 s of standing. The lowest of these 10 s averages was considered the nadir standing BP. The orthostatic drop was the difference between the resting BP and the standing nadir BP.

An exact, single-stage phase 2 study design was employed [8]. Based on the efficacy the most efficacious single therapy (bolus water drinking, 56% [2]), the study was powered to firstly, reject interventions where response rates were ≤55% (i.e. no better than water alone) and second, consider superior if response rates were ≥75% (alpha 0.05, beta 0.8).

Mean and standard deviation (SD) summarise normally distributed data, whereas the median with range is used for non-parametric data. Responses are described with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The paired t-test and Wilcoxon’s signed rank test were used to compare secondary outcomes.

Approvals

The study was approved by the UK National Research Ethics Service (Newcastle and North Tyneside 2; REC Reference 15/NE/0308). All participants provided written informed consent. Study registration ISRCTN15084870.

Results

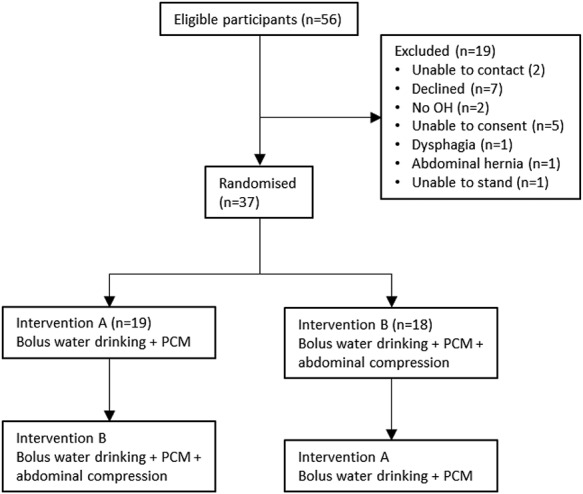

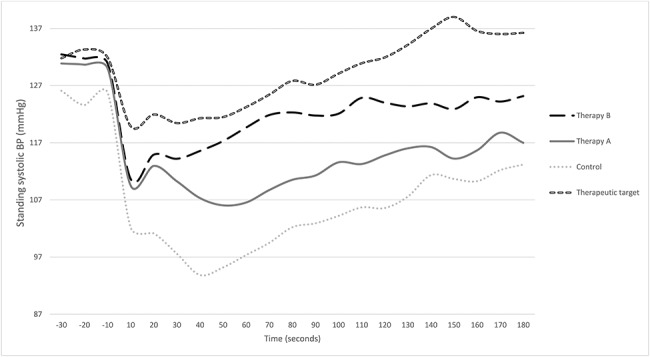

Thirty-seven participants were recruited between September 2017 and May 2018 (Figure 1). Demographic data, baseline cardiovascular data and symptom scores are provided in Table 1. The median volume of water consumed was 480 ml (range 164–480 ml), the temperature of which was 15.7°C (range 8.2–23.2°C). The median time to stand upright from supine position was 21.2 s (range 15–53 s). Two participants scored zero on the OHQ. Figure 2 summarises the mean BP trend during orthostatic challenge for each intervention. There were no adverse events to either therapy.

Figure 1.

Summary of participant screening and enrolment.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Demographic | |

|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 71 (60–94) |

| Female (%) | 14 (38%) |

| Charlson comorbidity score (median, range) | 3 (2–6) |

| Parkinson’s disease (n) | 9 |

| Type 2 diabetes (n) | 2 |

| Amyloid (n) | 1 |

| Number of medications (median, range) | 5 (0–16) |

| Taking fludrocortisone (n, %) | 6 (16%) |

| Taking midodrine (n, %) | 2 (5%) |

| Hand grip (kg, median, range) | 26 (7–52) |

| Control supine BP | 120.2 (±20.4)/76.3 (±15.7) |

| Control nadir standing BP | 78.4 (±24.9)/54.7 (±15) |

| Control BP drop | 42.3 (±23.7)/21.5 (±15) |

| OHQ symptom assessment score | 3 (0–8.4) |

| OHQ dizziness score | 3 (0–8) |

| OHQ daily activity score | 5 (0–8.75) |

Figure 2.

Change in systolic BP during orthostatic challenge with combination therapies. Control is no intervention. Therapeutic target is 10 mmHg greater than bolus water drinking used alone [2]. Standing occurs at time 0 s. Therapy B (bolus water drinking + PCM + abdominal compression); Therapy A (bolus water drinking + PCM).

Therapy A: Bolus water drinking + physical counter-manoeuvres

Fourteen of the 37 participants responded [response rate 38% (95% CI) 24–63%]. Symptoms during standing were similar to baseline [median OHSA score 2.3 (range 0–9.2), P 0.109]. Standing systolic BP was 91 mmHg (SD 29.5), which was significantly higher than during control (see Table 1; P 0.008), a mean increase of 13 mmHg (95% CI 4, 22). Systolic BP drop was 40 mmHg (SD 29), which was not significantly different to the baseline BP drop (P 0.457). Standing diastolic BP was significantly greater than control [64.0 (SD 20.0), P 0.004], whereas the drop in diastolic pressure was not significantly improved [17.5 (SD 20.5), P 0.163].

Therapy B: Bolus water drinking + physical counter-manoeuvres + abdominal compression

Seventeen participants responded to therapy B [response rate 46% (95% CI 31–62%)]. Symptom scores were comparable to control [median OHSA 2.0 (range 0–9.0), (P 0.101)]. Mean standing systolic BP was 98.8 mmHg (SD 25.2), which was significantly greater than control (P < 0.001), with a mean increase of 20 mmHg (95% CI 12, 29). Systolic BP drop was 32.1 (SD 24.2), which was significantly better than baseline (P 0.006). Standing diastolic BP was significantly greater than control [68.1 (SD 15.6), P < 0.001], with an improvement in the diastolic pressure drop [15.2 (SD 16.0), P 0.003].

Discussion

This study demonstrates that there is little additional benefit of combination therapy over single non-drug therapy on the primary outcome. Indeed, rather surprisingly the combination of bolus water drinking with PCM, appears to reduce the efficacy of water therapy. It is theoretically possible that the skeletal muscle vasodilation during PCM attenuates the vasopressor response to water. However, the addition of abdominal compression to the aforementioned combination, did improve secondary outcomes, but arguably not to the extent that it becomes clinically valuable. Analogous to the law of diminishing returns, the clinical benefits gained for the patient are less than the effort invested into using combination therapy.

These results are at odds with usual clinical practise, which typically involves recommending several non-pharmacologic interventions to patients with OH. This is particularly relevant for older and frailer populations who typically experience both polypharmacy and polytherapy for multiple conditions. These populations are also most likely to be non-adherent to their treatments [9]. Simplifying advice regarding non-pharmacologic therapy may offer an opportunity to improve uptake and adherence with treatment. The multifactorial pathogenesis of OH in older people may partly explain why there is a mixed response to the different therapies. For example, individuals with sarcopenia may have reduced efficacy of their skeletal muscle pump, whilst those with venous insufficiency may respond more readily to compression therapy. These considerations, alongside patient preference, could be used to select the most appropriate therapy Tolerability of therapies is an important consideration, particularly as compression garments are largely considered intolerable, bolus water drinking is mostly acceptable but PCM are by far the most acceptable to older people as they can be performed discretely, anywhere, without any preparation and without equipment [3]. Likewise, previous work has demonstrated that compression stockings are the least efficacious therapy, and with their low level of tolerability should not be used as first-line therapy [2]. The same study found that bolus water drinking was the most efficacious therapy, and although participants had initial reservations about it, once they had tried it, they found it easier than they anticipated [3]. It should therefore be considered as first line therapy for OH in older people. In contrast to water, the efficacy of PCMs was modest, but these were the most popular of the non-drug therapies which may promote uptake and adherence.

This phase 2 study is relatively small, which may limit its external validity and its power to detect changes in symptoms and BP drop. Outcomes were evaluated immediately and do not therefore reflect long-term effects, indeed the OHQ captures immediate symptoms and does not include longer-term outcomes such as falls or syncope. A small number of participants were medicated with midodrine or fludrocortisone. As midodrine is short acting and medications were withheld for ≥12 h, this is unlikely to have influenced the results. However, fludrocortisone has long-acting effects and may have influenced results. Whilst this is controlled for in the design of the study (each participant acts as their own control) its potential influence cannot be fully excluded. The minimum level of efficacy is based on the response to bolus water-drinking in a previous study. It must be recognised that only 38% of participants in this study also contributed to the water study [2], the response rate to water drinking could therefore have been different if repeated in this study. Further research is certainly required to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of non-pharmacologic therapies and how to improve their uptake and adherence.

Clinicians should consider using single non-pharmacological therapies as first line treatment. Using multiple therapies concurrently should be avoided.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

James Frith is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinician Scientist Award for this research project. This publication presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1. Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB et al. . Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res 2011; 21: 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Newton JL, Frith J. The efficacy of nonpharmacologic intervention for orthostatic hypotension associated with aging. Neurology 2018; 91: e652–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robinson LJ, Pearce RM, Frith J. Acceptability of non-drug therapies in older people with orthostatic hypotension: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics 2018; 18: 315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wieling W, Dijk N, Thijs RD, Lange FJ, Krediet CT, Halliwill JR. Physical countermeasures to increase orthostatic tolerance. J Intern Med 2015; 277: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Figueroa JJ, Singer W, Sandroni P et al. . Effects of patient-controlled abdominal compression on standing systolic blood pressure in adults with orthostatic hypotension. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96: 505–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jordan J, Shannon JR, Black BK et al. . The pressor response to water drinking in humans: a sympathetic reflex? Circulation 2000; 101: 504–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaufmann H, Malamut R, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Rosa K, Freeman R. The orthostatic hypotension questionnaire (OHQ): validation of a novel symptom assessment scale. Clin Auton Res 2012; 22: 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. A'Hern RP. Sample size tables for exact single-stage phase II designs. Stat Med 2001; 20: 859–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim S, Bennett K, Wallace E, Fahey T, Cahir C. Measuring medication adherence in older community-dwelling patients with multimorbidity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2018; 74: 357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]