Summary

Neuronal axons terminate as synaptic boutons that form stable yet plastic connections with their targets. Synaptic bouton development relies on an underlying network of both long-lived and dynamic microtubules that provide structural stability for the boutons while also allowing for their growth and remodeling. However, a molecular-scale mechanism that explains how neurons appropriately balance these two microtubule populations remains a mystery. We hypothesized that α-tubulin acetyltransferase (αTAT), which both stabilizes long-lived microtubules against mechanical stress via acetylation and has been implicated in promoting microtubule dynamics, could play a role in this process. Using the Drosophila neuromuscular junction as a model, we found that non-enzymatic dαTAT activity limits the growth of synaptic boutons by affecting dynamic, but not stable, microtubules. Loss of dαTAT results in the formation of ectopic boutons. These ectopic boutons can be similarly suppressed by resupplying enzyme-inactive dαTAT or by treatment with a low concentration of the microtubule-targeting agent vinblastine, which acts to suppress microtubule dynamics. Biophysical reconstitution experiments revealed that non-enzymatic αTAT1 activity destabilizes dynamic microtubules but does not substantially impact the stability of long-lived microtubules. Further, during microtubule growth, non-enzymatic αTAT1 activity results in increasingly extended tip structures, consistent with an increased rate of acceleration of catastrophe frequency with microtubule age, perhaps via tip structure remodeling. Through these mechanisms, αTAT enriches for stable microtubules at the expense of dynamic ones. We propose that the specific suppression of dynamic microtubules by non-enzymatic αTAT activity regulates the remodeling of microtubule networks during synaptic bouton development.

Keywords: microtubule, αTAT1, acetylation, neuron, synaptic bouton, microtubule aging, neuromuscular junction, Drosophila

Introduction

Microtubule networks are comprised of stable and dynamic microtubules that organize the internal structure of cells and determine cell shape. Neurons, with their extensive axonal and dendritic projections, are particularly reliant on balancing microtubule stability and dynamics. At axon terminals, microtubules underlie the development and remodeling of synaptic boutons, the axon terminal swellings that house synapses. Although microtubules are integral to neuronal structure and function, the molecular mechanisms that balance stable and dynamic microtubule populations within neurons and other cells are poorly characterized.

Microtubules are comprised of αβ tubulin heterodimers, which are stacked end-to-end into protofilaments that associate laterally to form a hollow tube. Dynamic microtubules grow and shorten in length, predominantly at their plus-ends, in a behavior termed dynamic instability [1]. In contrast, long-lived stable microtubules do not exhibit dynamic instability and appear to be strongly protected from shortening, perhaps by microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) [2]. A dynamic microtubule grows for extended periods of time via the addition of αβ tubulin heterodimers at its plus-end. Then, suddenly and stochastically, the microtubule will switch to a rapid shortening state. This transition from slow growth to rapid shortening is termed “catastrophe.” Catastrophe events are critical for ensuring that microtubules are able to rapidly restructure during dynamic cellular processes, such as synaptic bouton growth and remodeling. Indeed, the microtubule stabilizing agent Taxol limits the activity-induced formation of nascent boutons [3]. Although microtubule catastrophe events appear to happen at random, growing microtubules tend to catastrophe more frequently over time as they age [4]. This may be because a growing microtubule tip acquires features over time, such as a tapered tip due to variable protofilament lengths [5–7], which then predisposes the microtubule to catastrophe [7–11]. Thus, the rate at which dynamic microtubules age, or become prone to catastrophe, could ultimately impact neuronal development and plasticity.

Multiple MAPs and enzymes have been shown to regulate microtubule growth and stability in neurons and other cells [12–16]. However, the mechanism(s) by which cells balance stable and dynamic microtubules is not clear. Intriguingly, α-tubulin acetyltransferase 1 (αTAT1) has been implicated in promoting both microtubule stability and dynamics, potentially through enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities [17–23]. αTAT1 acetylates α-tubulin at lysine 40. This mark is associated with long-lived microtubules in cells [24] and is particularly enriched on neuronal microtubules. Acetylation itself does not stabilize dynamic microtubules [25] nor does it affect the overall structure of the microtubule lattice or the tubulin subunits [26]. Instead, acetylation likely protects long-lived microtubules from mechanical damage by modulating inter-protofilament interactions [17, 21, 23]. Thus, αTAT1 plays a role in preserving stable microtubules by acetylating them [17, 21, 23, 27, 28]. However, αTAT1 itself has also been reported to increase microtubule dynamics, perhaps independently of its enzymatic activity, although the mechanism by which it does so remains unclear [18]. Given the dual effect that αTAT1 may have on microtubules, we sought to determine whether and how αTAT1 might act to regulate the balance of stable and dynamic microtubules in developing neurons.

The Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is a well-established system for discovering conserved mechanisms by which microtubules shape synaptic terminal growth [29]. We tested whether Drosophila α-tubulin acetyltransferase (dαTAT), the Drosophila αTAT1 homolog, alters dynamic and/or stable microtubules in neurons by analyzing synaptic boutons at the NMJ in developing fruit flies. We found that the loss of dαTAT increased bouton number and led to the formation of small “satellite” boutons that are characteristic of changes to the underlying microtubule cytoskeleton. Strikingly, our data suggest that the increase in boutons in αTAT knockouts is due to the increased growth of dynamic microtubules without a significant effect on stable microtubules. An acetyltransferase-inactive dαTAT has similar effects on bouton growth as wild-type dαTAT, indicating that non-enzymatic dαTAT activity regulates synaptic terminal development. To further probe the non-enzymatic effects of αTAT on dynamic and stable microtubules, we turned to in vitro, cell-free reconstitution experiments. These experiments revealed that non-enzymatic αTAT1 activity destabilizes dynamic microtubules by increasing their catastrophe frequency. In contrast, αTAT1 has little effect on the depolymerization of stable microtubules, mirroring our in vivo findings. We found that αTAT1 acts at growing microtubule ends to alter microtubule tip structure, leading to gently curved, tapered structures at growing microtubule ends. Our analysis of dynamic microtubule aging in the presence of αTAT1 suggests that tip structure remodeling leads specifically to an increased catastrophe frequency of shorter, younger dynamic microtubules. In contrast, an increase in tapered structures at microtubule ends did not strongly increase the shortening rate of stable microtubules, suggesting that the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules is uniquely sensitive to αTAT1-induced alterations in tip structure. Thus, αTAT may enrich for long-lived microtubules through two pathways: by destabilizing dynamic microtubules through non-enzymatic activity, and by enhancing the resiliency of long-lived microtubules via its enzymatic activity. These data suggest that synaptic bouton growth is regulated, at least in part, by non-enzymatic αTAT activity that restrains the growth of dynamic microtubules.

Results

dαTAT limits synaptic bouton growth by restraining the growth of dynamic microtubules

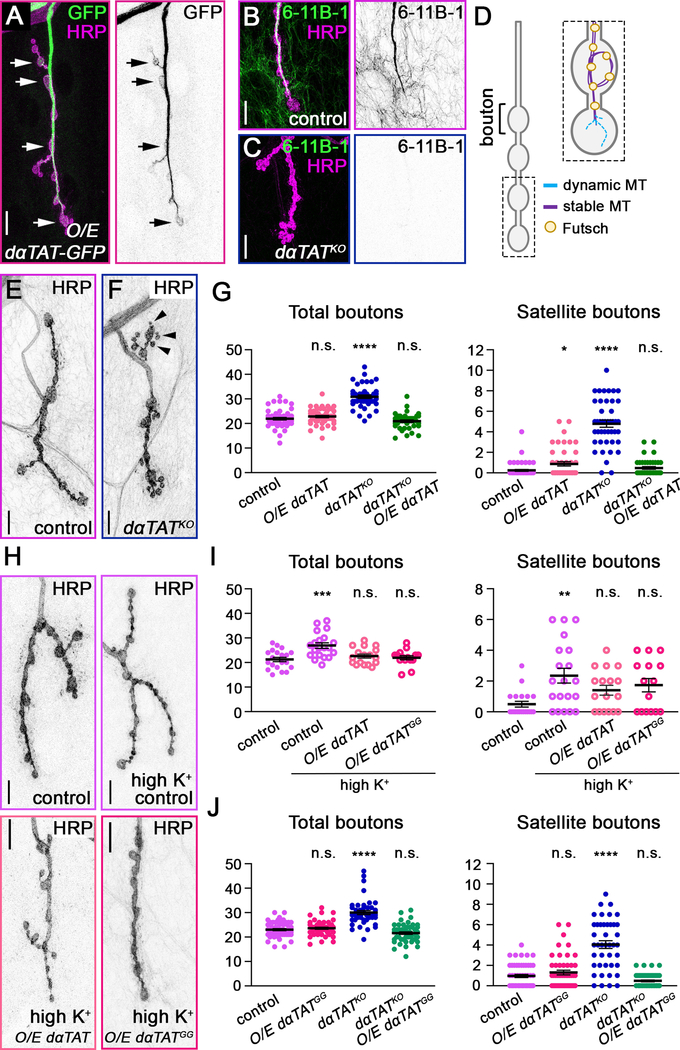

The Drosophila genome encodes a single highly conserved α-tubulin acetyltransferase, which we refer to as dαTAT, that was recently characterized and shown to be neuronally expressed [30]. We found that neuronally over-expressed GFP-tagged dαTAT localized to synaptic boutons and that the acetylation of microtubules at the NMJ depended on dαTAT, indicating that dαTAT is active at the NMJ (Figure 1A-1C). Synaptic bouton growth is regulated by the underlying microtubule cytoskeleton [29]. Stable microtubules bundled together compose the axon terminal core, whereas peripheral dynamic “pioneer” microtubules extend into nascent synaptic boutons (Figure 1D) [31–33]. Consistent with the idea that αTAT regulates microtubule stability and/or growth, we found that the loss of dαTAT increased overall bouton number and stimulated the formation of excess satellite boutons (Figure 1E-1G). The increased number of boutons in dαTAT knockout animals was rescued by the neuronal expression of dαTAT, indicating that the presynaptic activity of dαTAT in axons is sufficient to restrain bouton growth (Figure 1G). We next asked whether dαTAT is sufficient to limit bouton growth. Increasing dαTAT levels did not affect total bouton number in control animals, but the over-expression of dαTAT suppressed the formation of ectopic boutons that occurs in response to high-potassium stimulation (Figure 1H and 1I). αTAT has enzymatic and non-enzymatic effects on microtubules, leading to us test whether dαTAT relies on its acetyltransferase enzyme activity to regulate bouton growth. We resupplied neurons in the dαTAT knock-out with a catalytically inactive dαTAT that contains two mutations, G133W and G135W, that prevent dαTAT from acetylating microtubules (Figure S1) [19, 34]. In dαTAT-knockout neurons, enzymatically inactive dαTAT suppressed the formation of ectopic boutons similar to wild-type dαTAT, indicating the effect of dαTAT on bouton development relies on non-enzymatic activity (Figure 1J). Similar to wild-type dαTAT, inactive dαTAT also suppressed the formation of ectopic boutons in response to high-potassium stimulation (Figure 1H and 1I). Combined, these loss- and gain-of-function results indicate that dαTAT acts non-enzymatically to limit bouton growth.

Figure 1. dαTAT limits the growth of synaptic boutons at the NMJ.

Axon terminals on muscle 4 in 3rd instar larvae are outlined by HRP (magenta). Scale bars, 10 μm. (A) Neuronally over-expressed dαTAT-GFP (green) localizes to synaptic boutons (arrows highlight a subset of dαTAT-GFP-positive boutons). (B and C) Neuronal and muscle microtubules are acetylated in control (B) but not dαTATKO larvae (C). The 6–11B-1 antibody (green) recognizes acetylated microtubules. (D) Boutons at the NMJ contain a core of stable microtubules (solid purple lines) bound by Futsch (gold circles). Dynamic microtubules (blue dashed lines) grow and retract in the bouton periphery. (E and F) Representative images of synaptic terminals in control (E) and dαTATKO (F) larvae. Ectopic satellite boutons (arrowheads) sprout from axon terminals in dαTATKO larvae. (G-J) Quantification of total and satellite bouton numbers per NMJ 4 in control and experimental conditions as indicated (single-factor ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey; error bars: SEM). (G) Neuronal expression of dαTAT (O/E dαTAT) rescues the change in total and satellite bouton numbers in dαTATKO larvae. (H,I) Neuronal expression of wild-type (O/E dαTAT) or catalytically inactive dαTAT (O/E dαTATGG) suppresses the formation of ectopic boutons in response to high-potassium stimulation. (J) Ectopic boutons in dαTATKO larvae are suppressed by the expression of dαTATGG, indicating dαTAT limits bouton growth independently of its enzymatic activity (See also Figure S1). n.s. = not significant, *p = 0.01–0.05, **p = 0.01–0.001, ***p = 0.001–0.0001, ****p < 0.0001.

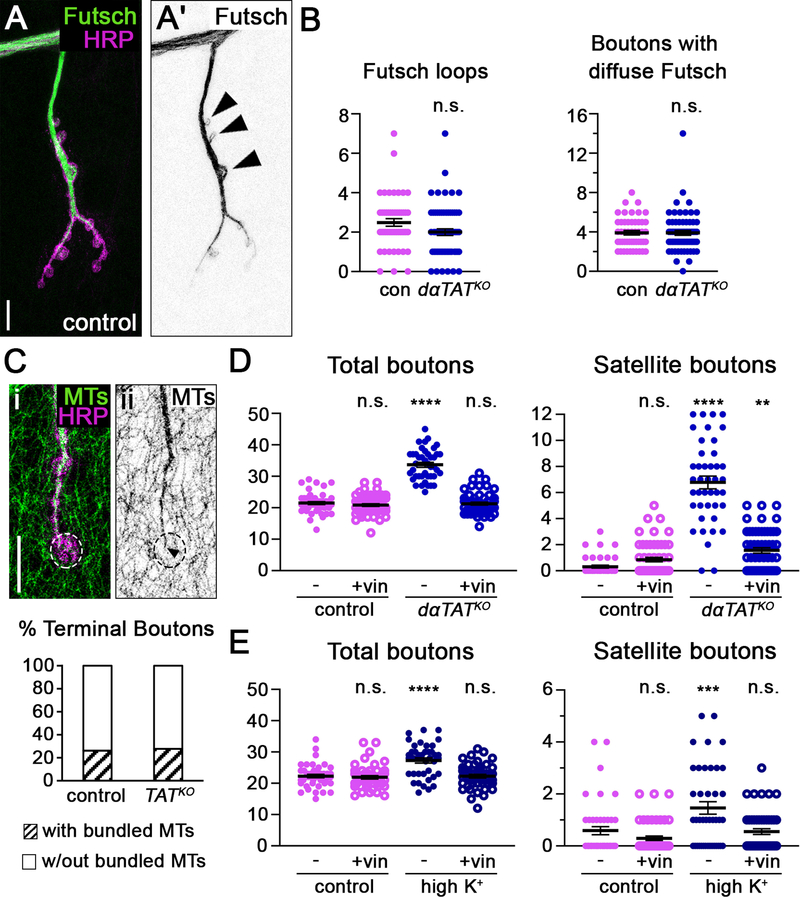

The formation of extra synaptic boutons, including the budding of satellite boutons, can be induced by an increase in stable and/or dynamic microtubules [29]. We first investigated what effect, if any, eliminating dαTAT had on stable microtubules by examining the distribution of the microtubule-associated protein Futsch. Futsch colocalizes with stable microtubules, some of which form loop-like structures in boutons (Figure 2A) [31, 35]. The loss of dαTAT, however, did not increase the number of Futsch-positive microtubule loops per NMJ or affect the number of boutons with diffuse Futsch signal at the NMJ, which suggests that dαTAT does not regulate bouton growth by enhancing microtubule stability (Figure 2B). Consistent with this idea, we found that bundled microtubules at the core of the NMJ extended into terminal boutons, similar to controls (Figure 2C). To test whether dαTAT regulates synaptic bouton growth through an effect on dynamic microtubules, we used the drug vinblastine, which at low concentrations restrains the growth of dynamic microtubules and induces kinetic stabilization [36, 37]. While previous studies have evaluated the effects of αTAT on microtubule growth by monitoring fluorescently tagged end-binding proteins (EBs) [21, 30, 38], EB1-GFP is difficult to visualize at the NMJ. Thus, rather than use EB1-GFP as a read-out of dynamic microtubule growth, we used vinblastine to functionally test whether the increased growth of dynamic microtubules underlies the increased bouton number in dαTAT knockout animals. Consistent with previous work, we found that a low dose of vinblastine had no effect on synaptic bouton growth in control animals, suggesting that dynamic microtubules are normally sparse, and/or their growth is tightly controlled, during axon terminal development (Figure 2D) [39]. Strikingly, vinblastine suppressed the formation of ectopic boutons in dαTAT knockout larvae (Figure 2D), which suggests that an increase in microtubule dynamics may be responsible for the bouton overgrowth in dαTAT knockout animals. Notably, the formation of ectopic boutons in response to high-potassium stimulation relies on dynamic microtubules (Figure 2E). Thus, the ability of over-expressed wild-type and enzymatically inactive dαTAT to inhibit ectopic bouton formation during high-potassium stimulation provides additional support to the idea that dαTAT suppresses dynamic microtubule growth. Consistent with our results, previous studies have found that EB1-GFP comet frequency increases when αTAT levels are reduced [21, 30, 38]. Combined with our Futsch results, this suggests that dαTAT may restrict bouton growth by selectively destabilizing dynamic microtubules.

Figure 2. Increased microtubule growth stimulates the formation of satellite boutons in dαTAT knockout animals.

(A) In neurons, Futsch labels long-lived microtubules, some of which form loops (arrowheads). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) The loss of dαTAT does not affect the number of Futsch-positive stable microtubule loops (“Futsch loops”) per NMJ 4 (top) (p=0.66, Mann-Whitney U test; error bars: SEM). The number of boutons with diffuse Futsch signal is also similar to controls in dαTATKO larvae (bottom) (p=0.83, Mann-Whitney U test; error bars: SEM). (C) Bundled microtubules at the NMJ core extend into ~25% of terminal boutons in control and dαTAT knockout animals. Top: Example of bundled microtubule core (arrowhead) extending into a terminal bouton (dotted circle). Bottom: Quantification of terminal boutons into which the bundled microtubule core has extended (n=12 control and 15 dαTATKO boutons). Scale bar, 10 μm. (D and E) Vinblastine suppresses the formation of ectopic boutons, including satellite boutons, in dαTATKO larvae and in response to high-potassium stimulation (single-factor ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey; error bars: SEM). n.s. = not significant, *p = 0.01–0.05, **p = 0.01–0.001, ***p = 0.001–0.0001, ****p < 0.0001.

αTAT1 increases the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules

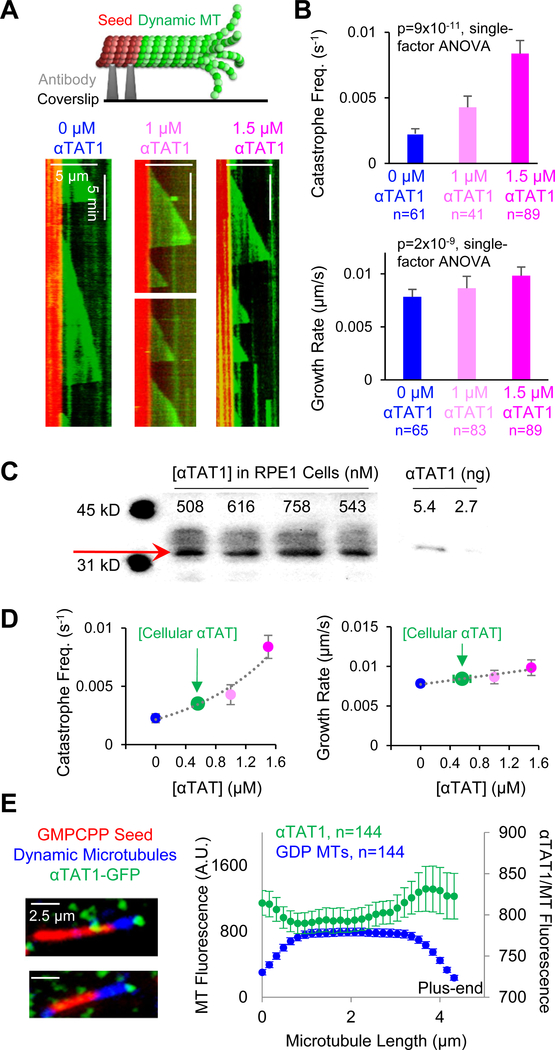

Our analysis of dαTAT at the NMJ suggests that non-enzymatic dαTAT activity has an effect on dynamic microtubules, with little effect on stable microtubules. To further explore the interaction of αTAT with microtubules, we turned to in-vitro cell-free reconstitution experiments to determine the effects of αTAT1, the human α-tubulin acetyltransferase, on dynamic and stable microtubules. We first tested what, if any, effect αTAT1 had on dynamic microtubules, independent of its role in enzymatically acetylating microtubules to alter their mechanics and dynamics [17, 21, 23]. Previous studies carried out in organisms and cells have revealed that αTAT1 itself has distinct functions that are separable from tubulin acetylation [18, 19], including an effect in promoting microtubule destabilization and accelerating microtubule dynamics [18]. Thus, we introduced AlexaFluor647-tubulin and GTP into an imaging chamber that had GMPCPP-stabilized rhodamine-labeled seeds adhered to a coverslip. We then analyzed the growth of dynamic microtubules from stabilized seeds in the presence or absence of αTAT1 (Figure 3A, top). In these assays, Acetyl Co-A was not present, thus preventing αTAT1 from enzymatically acetylating microtubules. Time-lapse videos of dynamic microtubules were converted into kymographs that were used to calculate both the catastrophe frequency and growth rate for individual microtubules (Figure 3A, bottom). Strikingly, we found an 89% increase in catastrophe frequency with 1.0 μM αTAT1 and a 270% increase with 1.5 μM αTAT1 (Figure 3B, top; p=9×10−11, single-factor ANOVA). At concentrations higher than 1.5 μM αTAT1 it was difficult to observe microtubule growth from the seeds. In contrast to the dramatic change in catastrophe, there was only a moderate 10% increase in the growth rate of dynamic microtubules incubated with 1.0 μM αTAT1 and a 26% increase with 1.5 μM αTAT1 (Figure 3B, bottom; no effect on rescue frequency, see Figure S2A). Thus, the dominant effect of αTAT1 on dynamic microtubules is an increase in catastrophe frequency.

Figure 3. Non-enzymatic αTAT1 activity increases the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules.

(A) Top: In vitro reconstitution experiments in which GMPCPP-stabilized seed templates (red) were adhered to a coverslip (black), and then dynamic GTP-microtubules (green) were grown from the seeds. Bottom: Representative kymographs of dynamic microtubules in control experiments (left), and in experiments with 1.0 μM αTAT1 (center), and with 1.5 μM αTAT1 (right). The kymographs display slices from time-lapse videos of dynamic microtubules such that position is across the x-axis and time is down the y-axis. Catastrophe frequency was calculated as the inverse of the microtubule lifetime. See also Videos S1–S2. (B) Top: Catastrophe frequencies of control dynamic microtubules and dynamic microtubules incubated with 1.0 μM αTAT1 and 1.5 μM αTAT1 (p=9×10−11, single-factor ANOVA; error bars: SEM). Bottom: Growth rates for control dynamic microtubules and dynamic microtubules incubated with 1.0 μM αTAT1 and 1.5 μM αTAT1 (p=1.8×10−09, single-factor ANOVA, error bars: SEM). Microtubule growth rate was calculated from the slope of the growth event. (C) Western blots showing detection of RPE1 cell lysates (left), and purified αTAT1 (right) by anti-αTAT1 antibody (LifeSpan BioSciences #LS-C116215). Blot smearing likely reflects αTAT1 isoforms inside of cells. (D) Estimates of αTAT1 concentration inside of RPE1 cells (green), placed in context of the in vitro microtubule dynamics results. (E) Left: Representative TIRF images of αTAT1-GFP (green) binding to Taxol-stabilized GDP-microtubules (blue) grown from stabilized seed templates (red). Right: Quantitative average fluorescence line scans indicating the localization of αTAT1-GFP (green) on Taxol-stabilized GDP-microtubules (blue) (n=144 microtubules, error bars 95% confidence intervals). Line scans of microtubules oriented with minus-end to the left and plus-end to the right; microtubules used in the analysis were ~4 μm long, with additional lengths shown in Figure S2D.

To determine whether these results could be important for microtubule dynamics inside of cells, we used western blotting to estimate the concentration of αTAT1 inside of human RPE1 cells (Figure 3C). Similar to previous work, we estimated the cellular αTAT1 concentration at ~500 nM (previously estimated at ~600 nM [9]). Based on the trends established in Figure 3B, we then estimated the non-enzymatic effect of αTAT1 inside of cells (Figure 3D). We found that αTAT1 could increase microtubule catastrophe frequency by a substantial ~50% inside of cells, while its effect on growth rate is predicted to be a moderate ~7% increase (Figure 3D). Consistent with our predictions, previously published data from NIH 3T3 cells demonstrated that the catastrophe frequency was increased by ~160% in cells that overexpressed a catalytically inactive αTAT1 mutant, relative to wild-type cells [18]. Further, the microtubule catastrophe frequency was decreased by ~−60% in αTAT1 depleted cells, relative to wild-type cells [18].

In order to increase the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules, we suspected that αTAT1 must be interacting with the tips of growing microtubules. To evaluate the localization of αTAT1 on dynamic microtubules, αTAT1-GFP was added to the dynamic microtubule assay. Similar to previous studies [26, 40], we found that αTAT1-GFP did not consistently tip-track on dynamic microtubules. However, by first flushing the chamber with a Taxol-containing buffer and then introducing αTAT1-GFP, we were able to quantify αTAT1-GFP localization over many GDP microtubules of similar length (Figure 3E; shown for additional microtubule lengths, Figure S2D). We found that αTAT1-GFP interacted with the entire microtubule lattice but had a moderately increased affinity for microtubule ends (Figure 3E, right). The preference of αTAT1-GFP for these microtubule ends may be due to the exposure of luminal α-tubulin K40 binding sites at opened or tapered tips (shown normalized to rhodamine-tubulin intensity, Figure S2C) [9, 40]. Thus, we conclude that αTAT1 likely interacts with microtubule plus-ends to increase the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules.

αTAT1 does not efficiently depolymerize stable microtubules

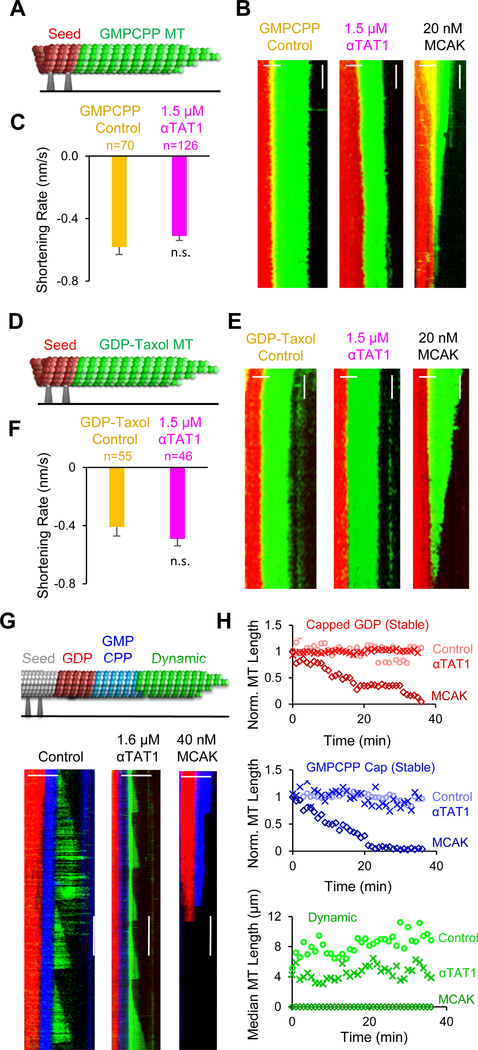

We then asked whether αTAT1 would have a destabilizing effect on stable microtubules. To perform this analysis, we used two different microtubule stabilization approaches: microtubules were grown either in the presence of the slowly hydrolyzing GTP analogue GMPCPP, or with GTP and subsequent stabilization using Taxol. Microtubules stabilized using these approaches are not expected to undergo catastrophe events, and, in addition, free tubulin is diluted once the microtubules are grown, and so they grow very slowly or not at all. Therefore, the effects of αTAT1 on the stability of GMPCPP or Taxol-stabilized microtubules was assessed by evaluating their shortening rate in the presence and absence of αTAT1.

First, GMPCPP microtubules grown from seed templates were incubated with or without αTAT1, and in the absence of free tubulin (Figure 4A). Kymographs generated from time-lapse videos of the GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules revealed that GMPCPP microtubules shortened very slowly (~0.6 nm/s), suggestive of stochastic loss of tubulin subunits from the microtubule end (Figure 4B). In contrast, the GMPCPP microtubules shortened quickly in positive control experiments with the potent microtubule depolymerase, MCAK (Figure 4B, right, 20 nM MCAK). Importantly, the shortening rates were statistically indistinguishable regardless of whether or not αTAT1 was present (Figure 4C, p=0.20, t-test). Next, we repeated the assay using GDP-Taxol-stabilized microtubules (Figure 4D). Similar to the GMPCPP microtubules, GDP-Taxol microtubules shortened slowly (~0.4–0.5 nm/s), and the shortening rates with or without αTAT1 were statistically indistinguishable (Figure 4E and 4F, p=0.30, t-test; with rapid depolymerization in positive control MCAK experiments (Figure 4E, right). These results indicate that αTAT1 does not efficiently depolymerize or destabilize GMPCPP-or Taxol-stabilized microtubules.

Figure 4. αTAT1 does not efficiently depolymerize stable microtubules.

(A) GMPCPP extensions were grown from coverslip-attached seed templates to evaluate the effect of αTAT1 on GMPCPP stabilized microtubules. (B) Example kymographs of green GMPCPP microtubules extending from red GMPCPP seeds in the presence of imaging buffer alone (left) and with 1.5 μM αTAT1 (center). Positive control experiments with 20 nM MCAK demonstrates robust depolymerization (right). (Scale bars 2 μm (horiz.) and 1 min (vertical)). (C) Measured shortening rates of GMPCPP extensions with just buffer (yellow), and with 1.5 μM αTAT1 (magenta) (p=0.20, t-test; error bars: SEM) (D) Taxol-stabilized GDP-microtubule extensions from coverslip-attached seed templates were observed to evaluate the effect of αTAT1 on Taxol stabilized GDP-microtubules. (E) Example kymographs of green GDP-Taxol Extensions from red GMPCPP seeds in control (left), 1.6 μM αTAT1 (center), and positive control (20 nM MCAK, right) experiments. (Scale bars 2 μm (horiz.) and 1 min (vertical)). (F) Measured shortening rates of GDP-Taxol extensions with imaging buffer alone (yellow), and with αTAT1 (magenta) (p=0.30, t-test; error bars: SEM). (G) Top: GDP extensions (red) were grown from coverslip-attached seed templates (grey), capped with GMPCPP-tubulin (blue), and then new dynamic (GTP) extensions were grown (green), to simultaneously evaluate the effect of αTAT1 on dynamic and stable microtubules in the presence of free tubulin. Bottom: Example kymographs in control (left), 1.6 μM αTAT1 (center), and 40 nM MCAK (right) experiments. (Scale bars 5 μm (horiz.) and 5 min (vertical)). See also Videos S3–S5. (H) Quantification of microtubule length over time for each microtubule type (top: capped GDP; middle: GMPCPP cap; bottom: dynamic GTP). Sample sizes (average number microtubules per time step): Capped GDP (top): Control 27, αTAT1 21, MCAK 19; GMPCPP (middle): Control 81, αTAT1 29, MCAK 54; Dynamic (bottom): Control 49, αTAT1 55, MCAK 0 (no growth).

Since αTAT1 interacts with the ends of stabilized microtubules [9, 40], we asked whether αTAT1 could potentially depolymerize stabilized microtubules over a longer time scale. Thus, we incubated Taxol-stabilized GMPCPP microtubules with or without αTAT1 in the absence of free tubulin and monitored microtubule length at 0, 7, and 24 hours. We found that while there was no substantial difference in microtubule length at 7 hours, by 24 hours, the Taxol-GMPCPP microtubules treated with αTAT1 were shorter than the untreated controls (Figure S2B, p=2.2×10−15, t-test at 24 hours). The slow shortening of microtubules over time in the absence of free tubulin suggests that αTAT1 acts as a weak depolymerase on stabilized microtubules, although αTAT1 may have little effect on stabilized microtubules in cells due to the presence of free tubulin that may act to counteract this weak effect by repairing damaged tips. However, in contrast, αTAT1 has a rapid and robust effect on increasing the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules.

To directly test the idea that αTAT1 may have little effect on stabilized microtubules in the presence of free tubulin, while simultaneously destabilizing dynamic microtubules under the same conditions, we performed an experiment that explicitly combined both types of microtubules, and included free tubulin. Specifically, we grew dynamic, GTP/GDP-tubulin microtubules from coverslip-attached seeds (Figure 4G, red), and then stabilized these microtubules by flowing GMPCPP-tubulin into the imaging chamber, thus “capping” and stabilizing the GDP microtubules (Figure 4G, blue GMPCPP “cap”). Finally, we introduced free tubulin along with GTP into the imaging chambers, allowing dynamic microtubules to grow from the stabilized microtubule combination (Figure 4G, green dynamic microtubule). This setup allowed us to evaluate microtubule length over time in one combined experiment, and in the presence of free tubulin, for two different types of stabilized microtubules (GDP-capped, and the GMPCPP cap itself), and for dynamic microtubules. We found that for control microtubules, in the absence of any additional proteins, microtubule length remained steady over time, both for the dynamic and the stable microtubules (Figure 4H, circles). In contrast, the known microtubule depolymerase MCAK led to shortening over time for both types of stable microtubules, and a complete frustration of growth for the dynamic microtubules (Figure 4H, diamonds). However, in the presence of αTAT1 (no Acetyl Co-A) both types of stable microtubules maintained a steady length over time, while the median length of dynamic microtubules was reduced relative to controls (Figure 4H, crosses). Thus, we conclude that non-enzymatic αTAT1 activity limits the length of dynamic microtubules, while having little effect on stabilized microtubules.

αTAT1 alters stable microtubule tip structures by increasing protofilament length variability

One way in which αTAT1 could destabilize a microtubule would be by altering the configuration of microtubule ends. Specifically, microtubule catastrophe could potentially be induced if αTAT1 “chewed away” GTP-tubulin subunits at the ends of individual protofilaments, thus altering the size and structure of the microtubule GTP-cap, and causing the lengths of the protofilaments at microtubule tips to be more variable, perhaps promoting gentle curvature of the tip [5–8, 10, 11, 41]. To ask whether αTAT1 alters microtubule tip structures, pre-made GMPCPP microtubules were incubated with or without αTAT1 (in the absence of free tubulin) and then imaged using cryo-electron microscopy. Strikingly, while control GMPCPP microtubules had relatively blunt tips with similar protofilament lengths (Figure 5A, left, yellow dotted lines), the microtubules incubated with αTAT1 often had long, tapered tip structures with correspondingly large variations in protofilament lengths (Figure 5A, right). To quantify this observation, we measured the distance between the end of the longest visible protofilament and the end of the shortest visible protofilament for each microtubule tip (defined as “tip taper”) in the cryo-electron microscopy images, disregarding lattice discontinuities. We found that the tip tapers of microtubules treated with αTAT1 were on average two-fold larger than those at the ends of control microtubules (Figure 5B, p=6.4×10−12, t-test).

Figure 5. αTAT1 alters microtubule tip structures.

(A) Representative cryo-electron microscopy images of GMPCPP microtubules incubated with buffer alone (left) or 1.0 μM αTAT1 (right). Yellow dotted lines highlight microtubule tips. (B) Measured tip tapers (difference in length between longest visible protofilament and shortest visible protofilament) show that the tip tapers of GMPCPP microtubules treated with αTAT1 were on average 2.1-fold larger than untreated control microtubules (p=6.4×10−12, t-test; error bars: SEM). (C) Left: Line scans of Rhodamine-labeled GMPCPP microtubule tips (insets, scale bar 1 μm) were collected for microtubules incubated in buffer alone (top) and with αTAT1 (bottom). The average line scans were then fit to an error function to calculate a “tip standard deviation” (σtip), which reflects the rate that fluorescence at the microtubule tip drops off to background. A slower drop-off (larger σtip) is reflective of a more tapered end. All microtubules included in this measurement were ~ 3 μm long. Right: Fitted tip standard deviations (p=0.02, Z= 2.25; error bars: 95% confidence intervals). (D) Top: Tip structures of dynamic microtubules were analyzed using TIRF microscopy. Bottom: Representative images of short and long dynamic microtubule extensions (green) suggest that short microtubules have similar tip configurations in the presence and absence of αTAT1 (blue arrows). However, in the presence of αTAT1, longer microtubules frequently showed curled tip structures that were not present in the controls (yellow arrows). (E) Left: Line scans of dynamic microtubule tips were collected for short (top) and long (bottom) microtubules that were incubated in buffer alone (blue) and with αTAT1 (magenta). The average line scans were then fit to an error function to calculate a “tip standard deviation” (σtip) at the microtubule plus-end, which reflects the rate that fluorescence at the microtubule tip drops off to background. A slower drop-off (larger σtip) is reflective of a more tapered end. Right: There was little difference in the tip standard deviation between control and αTAT1 for the short microtubules (p=0.96, Z=0.048). However, the tip standard deviation was 42% larger for αTAT1-treated long microtubules as compared to long microtubule controls (p<10−5, Z= 9.76). (Error bars: 95% confidence intervals).

To test whether this effect of αTAT1 on microtubule tip structures could be evaluated using fluorescence microscopy, we used previously acquired fluorescence microscopy data from an experiment in which fluorescently-labeled GMPCPP microtubules were incubated with or without αTAT1, in the absence of free tubulin [9]. We performed line scans over many microtubules, and then plotted the average drop-off in intensity at the microtubule end (Figure 5C, left) [9]. We fit the average drop-off in microtubule fluorescence at the microtubule end to a Gaussian decay function to calculate a “tip standard deviation” (σtip) for control and αTAT1-treated microtubules (Figure 5C, left) [42]. A larger tip standard deviation reflects a slower drop-off in intensity at the microtubule tip, which indicates an increase in tapering and/or protofilament length variability. Consistent with the cryo-electron microscopy results, we found that the tip standard deviation was larger for αTAT1-treated microtubules compared to controls (Figure 5C, right, p=0.02, Z=2.25). Thus, our microscopy data indicate that αTAT1 alters microtubule tip structure.

αTAT1 increases protofilament length variability at the tips of older dynamic microtubules

We then asked whether αTAT1 altered the tip structures of dynamic, GTP-microtubules. Here, GTP microtubules were grown from seed templates in the presence of free tubulin and GTP, and in the presence or absence of αTAT1. Still images were then collected for analysis (Figure 5D). Interestingly, while newly growing, shorter GTP-microtubule tips appeared unaffected by αTAT1, the older, longer microtubules incubated with αTAT1 frequently displayed thin, curving end structures that were not present in the controls (Figure 5D). This suggests that αTAT1 may progressively alter dynamic microtubule tip structures during growth such that longer, older microtubules may be more prone to αTAT1-induced tip structures changes than shorter, younger microtubules.

To test this idea, we performed line scans and plotted the intensity drop-off at the plus-ends of two different groups of growing GTP-tubulin microtubules: one group was comprised of newly growing “short” microtubules (~0.8 μm) and the other of older “long” microtubules (~3.8 μm) (Figure 5E, left). While the drop-off in intensity was similar for short microtubules regardless of whether or not αTAT1 was present (Figure 5E, left-top), for the long microtubules, the fluorescence intensity at microtubule plus-ends dropped off more slowly to background when αTAT1 was present (Figure 5E, left-bottom). We then calculated the tip standard deviation for the control and αTAT1-treated dynamic microtubules in each group [42]. For the short microtubule group, the tip standard deviation was similar between control and αTAT1-treated microtubules (Figure 5E, right, p=0.96, Z=0.048). For the long microtubule group, the tip standard deviations were larger than for the short microtubules regardless of whether αTAT1 was present, similar to previous reports [41, 43]. However, in contrast to the short microtubules, the tip standard deviation was 42% larger for αTAT1-treated long microtubules as compared to long microtubule controls (Figure 5E, right, p<10−5, Z=9.76). Thus, αTAT1 acts to increasingly alter the growing microtubule tip structure as dynamic microtubules grow and age.

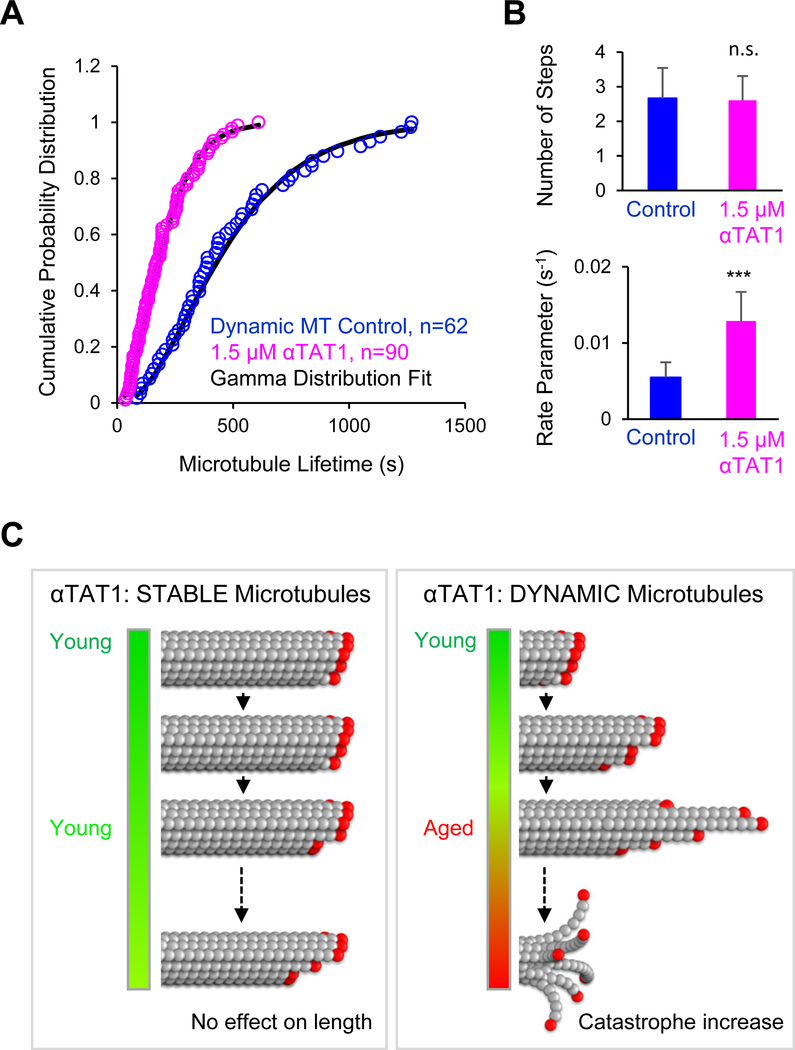

αTAT1 speeds the aging of dynamic microtubules

Previous work has demonstrated that the rate of microtubule catastrophe depends on the age of the microtubule [4, 44, 45]. Further, microtubule plus-ends naturally become more tapered, with an associated gentle curvature, as the microtubule grows, which may destabilize the tip and ultimately contribute to catastrophe [5–7, 11, 41]. Thus, the likelihood of a catastrophe event may be intimately linked to the aging physical structure of a growing microtubule tip. In this scenario, αTAT1, by restructuring the microtubule plus-end as dynamic microtubules grow and age, could potentially alter the rate at which catastrophe frequency accelerates with microtubule age. Alternatively, a microtubule-binding protein such as αTAT1 could increase catastrophe frequency but eliminate microtubule aging, such that the catastrophe frequency remains constant regardless of microtubule age (non-aging Exponential model) [4].

To first test whether αTAT1 eliminated the aging process altogether, we fit both the control and αTAT1 catastrophe time data to single-step, non-aging exponential models (n=1 step). However, both data sets fit poorly to this model (control, p=0.003; αTAT1, p=0.0049; Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test to exponential distribution), suggesting that the catastrophe frequency increased with microtubule age both in the presence and in the absence of αTAT1. We then fit our catastrophe data to aging (Gamma) probability distribution models, and found that both data sets fit well to multi-step, aging Gamma models (control, p=0.3571; αTAT1, p=0.4108; Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test to Gamma distribution).

We then fit our data to a Gamma distribution model to dissect whether and how αTAT1 altered the age-dependent probability of catastrophe for dynamic microtubules (Figure 6A) [4]. Specifically, the control and αTAT1 catastrophe time data were fit to Gamma distribution models (Figure 6A), allowing us to constrain the two fitting parameters that characterize the Gamma distribution (Figure 6B). The first fitting parameter, n, represents the number of steps in the aging process, and likely provides a general readout for the mechanism of catastrophe. The number of steps was similar in the controls and αTAT1-treated microtubules, suggesting that the overall mechanism of age-dependent catastrophe was not altered by αTAT1 (Figure 6B, top; p=0.462, Z-statistic=0.097). The second fitting parameter, r, represents a rate of acquiring “defects” at the microtubule tip, and is likely reflective of the rate of acceleration of catastrophe frequency with microtubule age, perhaps via tip structure remodeling. Importantly, the aging rate parameter was increased by 2.4-fold in the αTAT1-treated microtubules as compared to the controls (Fig. 6B, bottom; p=0.00035, Z-statistic=3.39), suggesting that the aging process itself was accelerated.

Figure 6. αTAT1 speeds the aging of dynamic microtubules.

(A) Microtubule lifetimes prior to catastrophe were plotted as a cumulative probability distribution, and then fitted to a Gamma probability distribution, which describes an aging process. (B) The fitting parameters for the Gamma distribution are (top) the number of steps required prior to a catastrophe event, which are similar between controls and αTAT1 treatments (p=0.46, Z=0.0967), and (bottom) the rate parameter for each step, which generally describes the speed of aging. The difference in rate parameters between control and αTAT1 treatment suggests that αTAT1 speeds microtubule aging (p=0.00035, Z=3.387). (Error bars: 95% confidence intervals). (C) Right: Schematic summarizing the proposed mechanism of dynamic microtubule aging by αTAT1: αTAT1 alters the tip structure of older microtubules, leading to increased tip tapering and associated protofilament curvature (curvature not shown in cartoon). This in turn leads to rapid aging and a higher catastrophe frequency in the presence of αTAT1. Left: A similar effect on stabilized microtubules has little effect on microtubule length.

Thus, we predict that for control microtubules, catastrophe events naturally become more probable as microtubules age, likely due to a gradually increasing taper and associated gentle curvature that destabilizes the growing microtubule plus-end [11, 41] (Figure 6C, right). However, αTAT1 acts to increase the rate of tip tapering and associated protofilament curvature by increasing the variability of protofilament lengths at the microtubule ends. This increased rate of tip structure remodeling then causes catastrophe events to become more probable at a younger microtubule age with αTAT1 than in its absence (Figure 6C, right). Thus, αTAT1 speeds the process of age-dependent catastrophe. In contrast, moderate alterations to the tip structure of stable microtubules are ineffective in altering the overall length, thus protecting stable microtubules from the effects of αTAT1 (Figure 6C, left).

Discussion

Microtubules are central to synaptic terminal growth, yet the mechanisms that balance stable and dynamic microtubules to regulate bouton morphogenesis are poorly understood. Our results support a new role for dαTAT in limiting bouton growth independently of its acetyltransferase activity. While the enzymatic effects of αTAT1 on stable microtubules have been well-studied, our work reveals that non-enzymatic dαTAT activity negatively regulates dynamic microtubules to control synaptic terminal growth. The idea that a microtubule-associated enzyme could have both enzymatic and non-enzymatic functions in regulating the microtubule cytoskeleton has recently been demonstrated for the microtubule severing enzyme spastin [46]. Through in vitro reconstitution experiments we show that non-enzymatic activity of human αTAT1 selectively promotes the catastrophe of dynamic, not stable, microtubules, which suggests a possible mechanism by which dαTAT may select against dynamic microtubules in neurons. However, while this mechanism could explain dαTAT ‘s effects in neurons, it is also possible that dαTAT restrains the growth of dynamic microtubules through additional or alternative mechanisms. Combined, our in vivo and in vitro cell-free reconstitution data support the overarching model that non-enzymatic dαTAT activity restrains synaptic bouton growth by restraining the growth of dynamic microtubules.

αTAT1 increases the magnitude and frequency of tapered, gently curved growing microtubule ends, likely through the removal of tubulin subunits specifically at growing microtubule plus-ends. These microtubule tip structures are characteristic of aging microtubules, and so αTAT1 accelerates the aging of dynamic microtubules. Thus, our data reveal a non-enzymatic activity of αTAT1 in promoting the rapid tip structure aging of dynamic microtubules, by which αTAT1 could select for long-lived microtubules in neurons and likely other cells.

The correlation between α-tubulin K40 acetylation and long-lived microtubules is well-established. Recent work suggests that this correlation may depend on the increased resiliency of acetylated microtubules [17, 23]; however, our results suggest that non-enzymatic αTAT1 activity may also enrich for stable microtubules by selectively destabilizing dynamic ones. Acetylated microtubules are prevalent in neurons, and αTAT1 has been previously implicated in neuronal development and sensory neuron function in a variety of organisms [19, 20, 30, 47–50]. Our data indicate that dαTAT restrains synaptic bouton growth by limiting the growth of dynamic microtubules at the Drosophila NMJ, consistent with previous studies of developing mouse and worm neurons [19, 21, 38]. While our work indicates that the non-enzymatic activity of αTAT1 limits neurite growth, another group has reported that this effect is acetylation-dependent [38]. One possibility is that in particular neuronal types, or under certain culture conditions, acetylation may protect microtubules that ultimately seed new dynamic microtubules [23]. αTAT1 may make dynamic microtubules “older” and more prone to catastrophe, but at the same time αTAT1-mediated acetylation might protect against the mechanical aging of long-lived microtubules that serve as nucleation platforms for new, dynamic microtubules. Thus, αTAT1 has synergistic enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities that enrich for long-lived microtubules in neurons.

The synergistic stabilizing and destabilizing effects that αTAT1 has on long-lived and dynamic microtubules, respectively, may allow αTAT1 to dynamically tune microtubule networks based on their composition. Young neurons, which actively extend neurites, likely have a higher fraction of dynamic microtubules than older neurons. Our work and that of others is consistent with the model that in young neurons, αTAT1 restrains exuberant microtubule and neurite growth, whereas in mature neurons, αTAT1 preserves long-lived microtubules by acetylating them. This may explain why the axons of young neurons lacking αTAT1 sprout ectopic neurites whereas adult worm neurons display a dramatic loss of microtubules and degenerate [19, 21]. Since αTAT1 binds both stable and dynamic microtubules, the proportion of these two microtubule populations within a network may influence the overall outcome of αTAT1 activity. It is also possible that αTAT1 could act to shift the balance towards a more stable microtubule network as neurons age.

The ability of αTAT1 to enhance microtubule catastrophe in cells has been previously reported [18], but the potential mechanism has been elusive. Our in vitro reconstitution experiments suggest that αTAT1 significantly increases microtubule catastrophe by increasing the rate at which protofilament length variability, tip tapering, and associated gentle tip curvatures accumulate at microtubule tips. This non-enzymatic effect of αTAT1 suggests that the binding of αTAT1 to its acetylation site inside the microtubule lumen may weaken tubulin-tubulin binding interactions regardless of whether enzymatic activity occurs. Because luminal acetylation sites tend to be exposed at microtubule ends [9], this would lead to the loss of tubulin subunits from individual protofilaments at the growing microtubule tip. Thus, the binding of αTAT1 to its acetylation site could transiently destabilize tubulin-tubulin bonds at the tips of dynamic microtubules, while acetylation itself could act to more permanently weaken inter-protofilament interactions as described by work from the Nachury group [17].

Aging is an inherent property of microtubule catastrophe [4, 44, 45]. In this work, we demonstrate that αTAT1’s weak affinity for the growing microtubule plus-end leads to a dramatic increase in the catastrophe frequency of dynamic microtubules but has a limited effect on stable microtubules. Thus, a subtle tuning of the microtubule catastrophe aging process, such as a moderate increase in the off-rate of tubulin subunits that leads to increased tip tapering and associated curvature when αTAT1 is bound, could provide a mechanism for dynamically tuning the balance between dynamic and stable microtubules in cellular-scale cytoskeletal networks. By subtly changing molecular interactions that are inherent to the microtubule aging process, αTAT1 could facilitate large-scale cytoskeletal network tuning in developing neurons and other cells.

STAR Methods

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Melissa Gardner (klei0091@umn.edu).

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restriction.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Fly Stocks

The following fly stocks were used in this study: w1118, UAS-GFP-dαTAT, UAS-GFP- dαTATGG, dαTATKO, OK6-Gal4, and Df(3L)BSC113 (stock # 8970, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Bloomington, Indiana). dαTATKO removes three dαTAT exons and eliminates dαTAT [30]. The catalytically inactive dαTAT has two mutations (G133W and G135W) that were introduced into the GFP-dαTAT construct [19, 30]. These mutations virtually eliminate acetylation (Figure S1). All stocks and crosses were maintained at 25°C under 12-hour light-dark cycles on standard cornmeal molasses food unless otherwise stated.

Cell Lines

Human RPE1 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, 1178 MA) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Cultures were grown at 1179 37°C in 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator, and maintained at low passage numbers. The cell line was authenticated using microscopy to examine morphology and kinetochore numbers.

Microbe Strains

A plasmid, pGEX-αTAT1[2–236] (gift from Maxence Nachury (Addgene # 27101) [50], or pEF5B-FRT-GFP-αTAT1 for localization studies (gift from Maxence Nachury (Addgene # 27099) [50] was transformed into Rosetta high protein expression E.coli (EMDMillipore, #71403)). E. coli containing these plasmids were grown in 10ml of LB+amp+cam media at 37 °C overnight, subcultured 1:200 into 500ml of fresh media, and grown for 3.5hr at 37 °C until an A600 of 0.58. IPTG was then added to 1mM final and the cultures continued growth at 18 °C for 16hr.

METHOD DETAILS

Immunohistochemistry

Wandering third instar larvae were dissected in PHEM buffer (80 mM PIPES pH6.9, 25 mM HEPES pH7.0, 7 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) and fixed in 4% PFA in 1X PBS with 3.2% sucrose for 45–60 minutes, permeabilized in PBS with 0.3% Triton-X100 for 20 minutes, quenched in 50 mM NH4Cl for 10 minutes, blocked in buffer containing 2.5% BSA (Sigma catalog number A9647), 0.25% FSG (Sigma catalog number G7765), 10 mM glycine, 50 mM NH4Cl, 0.05% Triton-X100 for at least 1 hour. Fillets were then incubated in primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C, washed in PBS with 0.1% Triton-X100 and incubated with secondary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C in the dark. After washing, fillets were mounted in elvanol containing antifade (polyvinyl alcohol, Tris 8.5, glycerol and DABCO, catalog number 11247100, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). The following antibodies were used: anti-acetylated tubulin 6–11B-1 (1:1000, or 1 μg mL−1, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-Futsch 22C10 (1:50, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), anti-alpha-tubulin DM1A (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-HRP conjugated AlexaFluor647 (1:3000, or 0.5 μg mL−1, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), Dylight 550 anti-mouse (1:1000, or 0.5 μg mL−1, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA), Dylight 488 anti-mouse (1:1000, or 0.5 μg mL−1, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). All neuron imaging was done on a SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Vinblastine Treatment

Control and dαTATKO larvae were raised on cornmeal molasses food containing 1 μM vinblastine (catalog number V1377, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). A previous study tested a range of vinblastine concentrations and found that 1 μM vinblastine has no overt effect on NMJ development [39]; we also found that this concentration has no effect on animal feeding based on a spectrophotometric analysis approach using groups of 10 larvae [51]. For the high-potassium stimulation experiments, 500 μM vinblastine was added to the control and high-potassium HL-3 buffers present throughout the treatment.

High-Potassium Treatment

Wandering third instar larvae were dissected in low-Ca2+ HL-3 saline (70 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, 115 mM sucrose, 5 mM trehalose, 5 mM HEPES) containing 0.1 mM Ca2+ and then incubated in high-K+ HL-3 saline containing 90 mM K+ and 1.5 mM Ca2+ for 2 minutes followed by incubation in low-Ca2+ HL-3 for 15 minutes; this was repeated four times. Following the last low-Ca2+ HL-3 incubation, the larvae were dissected as described above.

Tubulin Purification

Pig brain tubulin was purified and labelled as described in the detailed high-salt buffer protocol paper [52]. Briefly, fresh pig brains (Midwest Research Swine, Glencoe, MN) were used to polymerize microtubules from tubulin, and then successive polymerization/depolymerization cycles were performed to purify active tubulin. Further cycles of polymerization/depolymerization were completed in the presence of a label in order to generate fluorescently labeled tubulin, as described in the protocol paper by the Howard Lab [53].

Purification of αTAT1 and αTAT1-GFP

Cultures were centrifuged and the cell pellets resuspended in 16ml lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 2mM DTT, 2mM AEBSF, 4mg/ml lysozyme) and mixed for 90 min at 30 °C. The cell suspension was then frozen drop-wise into liquid nitrogen and the frozen beads were ground multiple times in a coffee grinder. Lysate was centrifuged at 18000xg for 1hr at 4 °C and the supernatant was mixed with 250ul of PBS-washed glutatione-sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare, #17–0756-01) for 2.5 hr at 4 °C. Beads were then washed 4x with 3ml of lysis buffer, resuspended in 1ml lysis buffer + 12ul of Prescission protease (GE Healthcare, #27–0843-01) and mixed at 4 °C for 20 hrs to release the αTAT1 from the GST tag and beads.

Western blot estimation of αTAT1 concentration in RPE1 cells

Human RPE1 cells were grown using standard culturing conditions (in DMEM, 10% FBS, 1x Penicillin/Streptomycin). The cells were dis-adhered, counted on hemocytometer and lysed in reducing electrophoresis buffer at 95° for 5 min. Cell lysates were loaded alongside known quantities of purified αTAT1 (5.4 and 2.7 ng), and detected for αTAT1 in western blots using rabbit anti-αTAT1 antibody (LifeSpan BioSciences #LS-C116215). Data from western blot band intensities of the cell lysates and purified protein, known cell numbers used, and cell diameter [54] were all used to calculate the concentration of αTAT1 in cells.

Preparation of GMPCPP Microtubules

To make stabilized GMPCPP microtubules, a 45 μL solution that consisted of 3.9 μM tubulin (25% rhodamine-labeled, 75% unlabeled) and 1 mM GMPCPP (jenabiosciences.com#NU405) in BRB80 was mixed and kept on ice for 5 min, then incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes to 2 hours. Following incubation, the seeds were diluted into 400 μL warm BRB80, and 350 μL of this dilution was spun down in an air-driven ultracentrifuge (Beckman.com#340400) @ 20 psi for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended into 400 μL warm BRB80.

Construction and Preparation of Flow Chambers for Imaging

Imaging flow chambers were constructed by placing two narrow strips of parafilm onto salinized coverslips, and following placement of the smaller coverslip onto the parafilm strips, the chamber was heated to melt the parafilm and create a seal between the coverslips similar to Section VII of Gell et al. 2010 [53]. Typically, only three strips of parafilm were used, resulting in two chambers per holder. Chambers were then flushed with anti-rhodamine antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-6397) and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, followed by flushing with Pluronic F127, which was allowed to incubate for a minimum of 30 minutes [53].

αTAT1-GFP Binding Assay and Imaging

A flow chamber was prepared as described above. GMPCPP microtubules were adhered to the chamber coverslip, and the chamber was flushed gently with warm BRB80. The flow chamber was heated to 30°C using an objective heater on the microtubule stage, and 3–4 channel volumes of imaging buffer (1X imaging buffer consisted of 20 μg/ml Glucose Oxidase, 10 μg/ml Catalase, 20 mM D-Glucose, 10 mM DTT, 80 μg/ml Casien, and 1% Tween-20) were flushed through the chamber. A reaction mixture containing imaging buffer and 8.1μM unlabeled tubulin, 3.5μM AlexaFluor647-tubulin, 0.6mM GTP, and 1μM αTAT1-GFP was introduced into the imaging chamber, with drops left at the flow chamber ends.

After 20 minutes, a new αTAT1-GFP (0.2μM final) mixture with 10μM Taxol (Sigma-Aldrich Cat#T7191) and imaging buffer was introduced into the imaging chamber, with drops left at the flow chamber ends. Images were collected using TIRF microscopy as described above.

Dynamic Microtubule Assay: Control Microtubules

GMPCPP microtubules were adhered to flow chamber coverslips. A mixture of imaging buffer, methyl cellulose, 8.2μM AlexaFluor647-tubulin, 4.2μM unlabeled tubulin, and 1mM GTP was prepared and centrifuged at 4°C for 5 minutes. The mixture was then warmed and introduced to the flow chamber and kept at 30°C. Time lapse images were taken every 5 seconds using TIRF microscopy.

Dynamic Microtubule Assay: with αTAT1

GMPCPP microtubules were adhered to flow chamber coverslips. A mixture of imaging buffer, methyl cellulose, 8.2μM AlexaFluor647-tubulin, 4.2μM unlabeled tubulin, 1mM GTP, and unlabeled αTAT1 was prepared and centrifuged at 4°C for 5 minutes. The mixture was then warmed and introduced to the flow chamber and kept at 30°C. Time lapse images were taken every 5 seconds using TIRF microscopy.

Capped GDP microtubules with dynamic microtubules

GMPCPP microtubules were adhered to flow chamber coverslips. A mixture of imaging buffer, 1 mM GTP, 4.4 μM unlabeled tubulin, and 6 μM AlexaFluor647-tubulin was prepared, warmed, introduced to the flow chamber, and kept at 30°C. Time was allowed for microtubule extensions to grow to ~4–5 um long. Then, a mixture of a mixture of imaging buffer, 1 mM GMPCPP, 7 μM unlabeled tubulin, and 2 μM rhodamine-tubulin was prepared, warmed, introduced to the flow chamber, and kept at 30°C. Time was allowed for GMPCPP microtubule extensions to grow to ~2 um long. Then, a mixture of a mixture of imaging buffer, 1 mM GTP, 5.2 μM unlabeled tubulin, and 4 μM AlexaFluor488-tubulin was prepared, warmed, introduced to the flow chamber, and kept at 30°C. Time-lapse images were taken every 5 seconds using TIRF microscopy. Microtubule lengths in time-lapse frames were then measured for analysis. In separate experiments, unlabeled αTAT1 or MCAK was included in the reaction mixture.

Stable Microtubule Depolymerization Assay: GMPCPP Microtubules

GMPCPP seed microtubules were adhered to flow chamber coverslips. A mixture of imaging buffer, 1mM GMPCPP, 1μM AlexaFluor647-tubulin, and 1μM unlabeled tubulin was introduced to the flow chamber and incubated at 30°C for 20 minutes. After 20 minutes, the chamber was gently flushed with warm imaging buffer. Then, a mixture of imaging buffer and 1.5μM αTAT1 was introduced to the chamber. Time lapse images were taken every 5 seconds for 30 minutes. Control assays were imaged with only imaging buffer.

Stable Microtubule Depolymerization Assay: GDP Microtubules

GMPCPP seed microtubules were adhered to flow chamber coverslips. A mixture of imaging buffer, 1mM GTP, 2μM AlexaFluor647-tubulin, and 10μM unlabeled tubulin was introduced to the flow chamber and incubated at 30°C for 10 minutes. After 10 minutes, the chamber was gently flushed with warm imaging buffer with 10μM Taxol. Then a mixture of imaging buffer, 10μM Taxol, and 1.5μM αTAT1 was introduced to the chamber. Time lapse images were taken every 5 seconds for 30 minutes. Control assays were imaged with only imaging buffer and Taxol.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy

Unlabeled GMPCPP microtubules were prepared as described above and incubated with 0 (control) or 1μM αTAT1 for 2 hours. Samples were prepared on a 300-mesh copper grid with a lacey-carbon support film. Grids were treated in a Pelco Glow Discharger before the addition of the GDP microtubule sample and freezing in vitreous ice using a FEI Vitrobot. Specimens were observed using an FEI Technai Spirit BioTWIN transmission electron microscope. Images were recorded at 15,000X-23,000X at −3 to −5 defocus.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Bouton number and Futsch quantification

The 1b boutons at NMJ 4 of segments A2-A4 were quantified. Satellite boutons were defined as five or fewer small boutons emanating from the main terminal nerve branch. Futsch loops were defined as complete, unbroken loops of signal within a bouton and diffuse Futsch defined as a bouton containing Futsch signal that did not form a continuous loop.

Dynamic Microtubule Assay Analysis

Kymographs of the dynamic microtubules were prepared using ImageJ by displaying slices of the images at each time frame. The catastrophe frequency and growth rates were measured by pixel position using ImageJ.

Analysis of Microtubule Tip Structure

Microtubule fluorescence intensity was analyzed, and the microtubule aligned, as previously described [9]. Here, the single time point images of GMPCPP microtubules were cropped to separate each microtubule into a single image using ImageJ. Then, integrated and averaged line scans of each microtubule image were created using a MATLAB script. For the GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules, each microtubule was aligned with the dimmer rhodamine fluorescence end on the right, and then the red fluorescence was plotted as a function of microtubule length from the brighter signal end to the dimmer signal end, in an effort to align like tip structures, as the dimmer end may represent a more tapered tip. To do this, the red tubulin fluorescence was integrated along the length of each microtubule ± 4 pixels above and below the microtubule centerline to account for point spread function and variability in properly finding the microtubule centerline. Then, the red fluorescence intensity was summed over the last 9 pixels on both ends of the microtubule. The lower summed value was considered the dimmer end, while the higher summed value was deemed the brighter end. To combine all individual microtubule data into an ensemble average plot, the microtubules were rebinned to a common lengths, represented by the mean length of all observed microtubules [55]. Scatter plots of the ensemble average values were created by importing the integrated line scan fluorescence data into Excel. Average tip standard deviation values were calculated by fitting an error function to the microtubule ends, as previously described [42].

αTAT1-GFP Binding Assay Image Analysis

The single time point images of GMPCPP and Dynamic-Taxol microtubules with αTAT1-GFP were cropped to separate each microtubule into a single image using ImageJ. Then, integrated and averaged line scans of each microtubule image were created using a MATLAB script. In each case, the microtubule was aligned with the dynamic microtubule plus-end on the right, and then the far-red and green fluorescence were plotted as a function of microtubule length from microtubule minus end to microtubule plus end. Scatter plots were created by importing the integrated line scan fluorescence data into Excel.

Fluorescence Microtubule Tip Assay

The single time point images of GMPCPP microtubules with and without 30nM αTAT1-GFP were cropped to separate each microtubule into a single image using ImageJ. Then, integrated and averaged line scans of each microtubule image were created using a MATLAB script. In each case, for consistency in aligning like tip configurations between microtubules, as the dimmer microtubule end may represent a more tapered tip structure, each microtubule was aligned with the dimmer red fluorescence end on the right, and then the red and green fluorescence were plotted as a function of microtubule length from brighter end to microtubule dimmer end. To do this, the red tubulin fluorescence was integrated along the length of each microtubule ± 4 pixels above and below the microtubule centerline to account for point spread function and variability in properly finding the microtubule centerline. Then, the red fluorescence intensity was summed over the last 9 pixels on both ends of the microtubule. The lower summed value was considered dimmer microtubule end, while the higher summed value was deemed the brighter microtubule end. Scatter plots were created by importing the integrated line scan fluorescence data into Excel.

Statistical Analysis

All reported tests were calculated in R (R Project for Statistical Computing), Microsoft Excel, STATA/SE (Stata Corp), or GraphPad PRISM and are noted in the manuscript. Neuron-derived data were collected and analyzed blind, and then tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk. Normally distributed data were then analyzed for equal variance and significance using F-tests and t-tests (two-sample comparison) or single-factor ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (multiple sample comparison). Non-normally distributed data were analyzed for variance using Kruskal-Wallis with post-hoc Dunn test for significance (multiple-sample comparison) or Mann-Whitney U test (two-sample comparison).

Supplementary Material

Control Dynamic AlexaFluor488 GTP-tubulin microtubules (green) growing from stabilized, cover-slip attached Rhodamine-GMPCPP microtubule seeds (red).

Dynamic AlexaFluor488 GTP-tubulin microtubules (green) growing from stabilized, coverslip-attached Rhodamine-GMPCPP microtubule seeds (red), in the presence of 1.5 μM unlabeled human αTAT1 (no Acetyl-Co is present, and only non-enzymatic activity is observed).

In this video, the coverslip attached, stabilized GMPCPP seed is not visible. An AlexaFluor647-tubulin (far-red) GTP/GDP extension was grown from the coverslip-attached seed, and then capped by flowing in Rhodamine-GMPCPP-tubulin (blue). Then, dynamic AlexaFluor488-tubulin GTP microtubules (green) were grown from the capped 2-color extensions. Growth and shortening of the AlexaFluor488-tubulin microtubules is observed, while the capped GDP-tubulin extensions remain unchanged.

In this video, the coverslip attached, stabilized GMPCPP seed is not visible. An AlexaFluor647-tubulin (far-red) GTP/GDP extension was grown from the coverslip-attached seed, and then capped by flowing in Rhodamine-GMPCPP tubulin (blue). Then, dynamic AlexaFluor488-tubulin GTP microtubules (green) were grown from the capped 2-color extensions in the presence of 1.6 μM unlabeled human αTAT1 (no Acetyl-Co is present, and only non-enzymatic activity is observed). Growth and shortening of the AlexaFluor488-tubulin microtubules is observed, while the capped GDP-tubulin extensions remain unchanged.

In this video, the coverslip attached, stabilized GMPCPP seed is not visible. An AlexaFluor647-tubulin (far-red) GTP/GDP extension was grown from the coverslip-attached seed, and then capped by flowing in Rhodamine-GMPCPP tubulin (blue). Then, dynamic AlexaFluor488-tubulin GTP microtubules (green) were grown from the capped 2-color extensions in the presence of 40 nM unlabeled human MCAK plus ATP. No growth of the AlexaFluor488-tubulin microtubules is observed, and the capped GDP-tubulin extensions ultimately depolymerize.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-acetylated tubulin 6– 11B-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T6793, RRID:AB_477585 |

| anti-Futsch 22C10 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | DSHB Cat# 22c10, RRID:AB_528403 |

| anti-alpha tubulin DM1A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T6199, RRID:AB_477583 |

| anti-HRP conjugated Alexa Fluor 647 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 123–605-021, RRID:AB_2338967 |

| Dylight 550 anti-mouse | ThermoFisher | Cat# SA5–10167, RRID:AB_2556747 |

| Dylight 488 anti-mouse | ThermoFisher | Cat# SA5–10166, RRID:AB_2556746 |

| Anti-αTAT, Rabbit | Lifespan Biosciences | Cat# LS-C116215 RRID:AB_10913028 |

| Anti-rhodamine, Rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-6397, RRID:AB_2536196 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Rosetta 2 DE3 pLysS Expression E. coli | EMDMillipore | Cat# A-6397, RRID:AB_2536196 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Porcine (Pig) Brains | Midwest Research Swine | https://midwestresearchswine.com |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Vinblastine Sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# V1377 |

| BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A9647 |

| FSG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G7765 |

| DABCO | Fisher Scientific | Cat#11247100 |

| Glutathione Sepharose 4B | GE Life Sciences | Cat# 17–0756-01 |

| Prescission protease | GE Life Sciences | Cat# 27–0843-01 |

| Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium | ThermoFisher Sci. | 1178 MA |

| AlexaFluor647 NHS Ester | ThermoFisher Sci. | A20006 |

| AlexaFluor488 NHS Ester | ThermoFisher Sci. | A20000 |

| GTP (Guanosine triphosphate), disodium salt hydrate | Fisher Scientific | AC22625–0010 |

| GMPCPP (Guanosine-5’-[(α,β)-methyleno]triphosphate, Sodium salt) | Jena Biosciences | Cat#NU-405 |

| Taxol (Paclitaxel) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T7191 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| RPE-1 Human | Dr. Lars Jansen | RRID:CVCL_4388 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D. melanogaster: w[1118] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) | BL6326, RRID:BDSC_6326 |

| D. melanogaster: P(Gal4)OK6 | BDSC | BL 64199, RRID:BDSC_64199 |

| D. melanogaster: Df(3L)BSC113 | BDSC | BL8970, RRID:BDSC_8970 |

| D. melanogaster: w[1118]; UAS-GFP-dTat-L | [30] | NA |

| D. melanogaster: w[1118; UAS-GFP-dTat-cat dead | [30] | NA |

| D. melanogaster: w[1118]; dTat[KO] | [30] | NA |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGEX-αTAT1[2–236] | Maxence Nachury [50], Addgene | RRID: Addgene_27101 |

| pEF5B-FRT-GFP-αTAT1 | Maxence Nachury [50], Addgene | RRID: Addgene_27099 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | National Institute of Health, USA | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ RRID:SCR_003070 |

| Excel | Microsoft | https://products.office.com/en-gb/excel RRID:SCR_016137 |

| STATA/SE | StataCorpxs | https://www.stata.com/products/ RRID:SCR_012763 |

| GraphPad PRISM | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com RRID:SCR_002798 |

| Leica LAS AF software | Leica LAS AF software | http://www.leica-microsystems.com/products/microscope-software/ RRID:SCR_016555 |

| Adobe PhotoShop | Adobe | http://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html RRID:SCR_014199 |

| MATLAB | Mathworks | https://www.mathworks.com/ RRID:SCR_001622 |

| Other | ||

| Leica TCS SP5 microscope | Leica Microsystems | https://www.leica-microsystems.com RRID:SCR_008960 |

| Nikon Ti-E TIRF Microscope | Nikon | https://www.nikon.com |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant R21NS101553 from the NINDS of the National Institutes of Health to J.W. and M.K.G. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Parts of this work were carried out in the Characterization Facility, University of Minnesota, a member of the NSF-funded Materials Research Facilities Network (www.mrfn.org) via the MRSEC program. We thank members of the Wildonger and Gardner laboratories for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

This study did not generate large data sets, and all described analysis code has been previously published and appropriately referenced.

References

- 1.Mitchison T, and Kirschner M. (1984). Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 312, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapin SJ, and Bulinski JC (1992). Microtubule stabilization by assembly-promoting microtubule-associated proteins: a repeat performance. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 23, 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin CN, Nechipurenko IV, Liu N, and Broihier HT (2016). A Toll receptor-FoxO pathway represses Pavarotti/MKLP1 to promote microtubule dynamics in motoneurons. The Journal of cell biology 214, 459–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner MK, Zanic M, Gell C, Bormuth V, and Howard J. (2011). Depolymerizing Kinesins Kip3 and MCAK Shape Cellular Microtubule Architecture by Differential Control of Catastrophe. Cell 147, 1092–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chretien D, Fuller SD, and Karsenti E. (1995). Structure of growing microtubule ends: two-dimensional sheets close into tubes at variable rates. Journal of Cell Biology 129, 1311–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guesdon A, Bazile F, Buey RM, Mohan R, Monier S, Garcia RR, Angevin M, Heichette C, Wieneke R, Tampe R, et al. (2016). EB1 interacts with outwardly curved and straight regions of the microtubule lattice. Nature cell biology 18, 1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, and Milligan RA (1991). Microtubule dynamics and microtubule caps: a time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy study. The Journal of cell biology 114, 977–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aher A, and Akhmanova A. (2018). Tipping microtubule dynamics, one protofilament at a time. Curr Opin Cell Biol 50, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coombes C, Yamamoto A, McClellan M, Reid TA, Plooster M, Luxton GW, Alper J, Howard J, and Gardner MK (2016). Mechanism of microtubule lumen entry for the alpha-tubulin acetyltransferase enzyme alphaTAT1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, E7176–E7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doodhi H, Prota AE, Rodriguez-Garcia R, Xiao H, Custar DW, Bargsten K, Katrukha EA, Hilbert M, Hua S, Jiang K, et al. (2016). Termination of Protofilament Elongation by Eribulin Induces Lattice Defects that Promote Microtubule Catastrophes. Current biology : CB 26, 1713–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zakharov P, Gudimchuk N, Voevodin V, Tikhonravov A, Ataullakhanov FI, and Grishchuk EL (2015). Molecular and Mechanical Causes of Microtubule Catastrophe and Aging. Biophysical journal 109, 2574–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohan R, Katrukha EA, Doodhi H, Smal I, Meijering E, Kapitein LC, Steinmetz MO, and Akhmanova A. (2013). End-binding proteins sensitize microtubules to the action of microtubule-targeting agents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 8900–8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Willige D, Hoogenraad CC, and Akhmanova A. (2016). Microtubule plus-end tracking proteins in neuronal development. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 73, 2053–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penazzi L, Bakota L, and Brandt R. (2016). Microtubule Dynamics in Neuronal Development, Plasticity, and Neurodegeneration. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 321, 89–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magiera MM, Singh P, Gadadhar S, and Janke C. (2018). Tubulin Posttranslational Modifications and Emerging Links to Human Disease. Cell 173, 1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magiera MM, and Janke C. (2014). Post-translational modifications of tubulin. Current biology : CB 24, R351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portran D, Schaedel L, Xu Z, Thery M, and Nachury MV (2017). Tubulin acetylation protects long-lived microtubules against mechanical ageing. Nature cell biology 19, 391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalebic N, Martinez C, Perlas E, Hublitz P, Bilbao-Cortes D, Fiedorczuk K, Andolfo A, and Heppenstall PA (2013). Tubulin acetyltransferase alphaTAT1 destabilizes microtubules independently of its acetylation activity. Mol Cell Biol 33, 1114–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topalidou I, Keller C, Kalebic N, Nguyen KC, Somhegyi H, Politi KA, Heppenstall P, Hall DH, and Chalfie M. (2012). Genetically separable functions of the MEC-17 tubulin acetyltransferase affect microtubule organization. Current biology : CB 22, 1057–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalebic N, Sorrentino S, Perlas E, Bolasco G, Martinez C, and Heppenstall PA (2013). alphaTAT1 is the major alpha-tubulin acetyltransferase in mice. Nat Commun 4, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumann B, and Hilliard MA (2014). Loss of MEC-17 leads to microtubule instability and axonal degeneration. Cell Rep 6, 93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cueva JG, Hsin J, Huang KC, and Goodman MB (2012). Posttranslational acetylation of alpha-tubulin constrains protofilament number in native microtubules. Current biology : CB 22, 1066–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Z, Schaedel L, Portran D, Aguilar A, Gaillard J, Marinkovich MP, Thery M, and Nachury MV (2017). Microtubules acquire resistance from mechanical breakage through intralumenal acetylation. Science 356, 328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cambray-Deakin MA, and Burgoyne RD (1987). Posttranslational modifications of alpha-tubulin: acetylated and detyrosinated forms in axons of rat cerebellum. The Journal of cell biology 104, 1569–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulze E, Asai DJ, Bulinski JC, and Kirschner M. (1987). Posttranslational modification and microtubule stability. The Journal of cell biology 105, 2167–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howes SC, Alushin GM, Shida T, Nachury MV, and Nogales E. (2014). Effects of tubulin acetylation and tubulin acetyltransferase binding on microtubule structure. Molecular biology of the cell 25, 257–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webster DR, and Borisy GG (1989). Microtubules are acetylated in domains that turn over slowly. Journal of cell science 92 ( Pt 1), 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montagnac G, Meas-Yedid V, Irondelle M, Castro-Castro A, Franco M, Shida T, Nachury MV, Benmerah A, Olivo-Marin JC, and Chavrier P. (2013). alphaTAT1 catalyses microtubule acetylation at clathrin-coated pits. Nature 502, 567–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodaleo FJ, and Gonzalez-Billault C. (2016). The Presynaptic Microtubule Cytoskeleton in Physiological and Pathological Conditions: Lessons from Drosophila Fragile X Syndrome and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias. Front Mol Neurosci 9, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan C, Wang F, Peng Y, Williams CR, Jenkins B, Wildonger J, Kim HJ, Perr JB, Vaughan JC, Kern ME, et al. (2018). Microtubule Acetylation Is Required for Mechanosensation in Drosophila. Cell Rep 25, 1051–1065 e1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roos J, Hummel T, Ng N, Klambt C, and Davis GW (2000). Drosophila Futsch regulates synaptic microtubule organization and is necessary for synaptic growth. Neuron 26, 371–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawson C, Eaton BA, and Davis GW (2008). Formin-dependent synaptic growth: evidence that Dlar signals via Diaphanous to modulate synaptic actin and dynamic pioneer microtubules. J Neurosci 28, 11111–11123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]