Abstract

Fatigue is a subjective overwhelming feeling of tiredness at rest, exhaustion with activity, lack of energy that impedes daily tasks, lack of endurance, or a loss of vigor. Individuals with end stage renal disease (ESRD) experience a high rate and severity of fatigue. Symptom management of fatigue in this population is critical, since fatigue has been linked with lower quality of life and higher mortality rates. In this article, we present a definition and overview of fatigue, a review of factors contributing to fatigue, and ways to manage fatigue in individuals with ESRD.

Keywords: End stage renal disease, fatigue, symptom management

Fatigue is defined as a subjective overwhelming feeling of tiredness at rest, exhaustion with activity, lack of energy that impedes daily tasks, lack of endurance, or as loss of vigor that can be unpleasant, distressing, and can interfere with physical and social activity (Finsterer & Mahjoub, 2013; Schipper & Abma, 2011). In general, fatigue is associated with chronic conditions, depression, poor sleep quality, stress, and extended periods of energy expenditure. In addition, susceptibility to fatigue may be influenced by genetic factors (Ali & Taha, 2017; Bossola, Luciani, & Tazza, 2009; Bossola, Di Stasio, Giungi, Rosa, & Tazza, 2015; Flythe et al., 2015; Liu, 2006; Wang, Yin, Miller, & Xiao, 2017; Williams, Crane, & Kring, 2007). Untreated fatigue can impact quality of life, leading to weakness, increased dependence on others, decreased physical and mental energy, social withdrawal, and depression (O’Sullivan & McCarthy, 2009).

Methods

A narrative review approach was selected to synthesize the current evidence due to the immense amount of literature regarding fatigue in individuals with ESRD. A thorough literature search was conducted of PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Articles and reference lists from December 2001 to June 2018 were referred. This timeframe was chosen based on the state of the science. The search strategy included terms for end stage renal disease, kidney failure, fatigue, genetic, interventions, symptom management, and treatment. Hand searches were conducted of reference lists of all included articles and pertinent systematic reviews. Abstracts were screened for relevance.

Fatigue Prevalence and Impact in ESRD

Fatigue affects 60% to 97% of individuals with ESRD undergoing hemodialysis (HD) (Jhamb et al., 2013). The severity of fatigue in individuals with ESRD undergoing HD treatment is one of the highest among individuals with a chronic condition, including patients with cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy treatment, patients with depression, and patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Zyga et al., 2015). The impact of fatigue in individuals with ESRD is so profound that 94% of patients on HD reported they would be willing to receive more frequent HD if it would increase energy levels; however, only 19% would agree to more frequent treatments for a three-year increase in survival (Jhamb et al., 2009). Fatigue was one of the four symptoms associated with worse quality of life, with the other three being pain, shortness of breath, and lack of well-being (Davison & Jhangri, 2010). Fatigue affects many aspects of life for individuals with ERSD undergoing dialysis. It is linked with lower quality of life, negatively impacts daily living and activity, increases risk for cardiovascular events, and is associated with higher mortality rates (Bonner, Wellard, & Caltabiano, 2007; Bossola, DiStasio, Antocicco, Panico et al., 2015; Flythe et al, 2015; Jhamb et al., 2009; Koyama et al., 2010; Letchmi et al., 2011; O’Sullivan & McCarthy, 2009; Wang et al., 2017; Zyga et al., 2015).

Factors Contributing to Fatigue

The causes of fatigue in individuals with ESRD remain poorly understood. Fatigue can be experienced regardless of race, gender, and age. Table 1 depicts recent studies that have examined the association of demographic factors with fatigue and the fatigue measure utilized, design, strengths, and weaknesses of these studies. Based on examined studies, there is inconclusive evidence regarding difference in prevalence among race, gender, or age for those living with ESRD.

Table 1.

Demographic Factors Attributing to Fatigue

| Author/Year | Number of Participants | Race | Gender | Age | Design | Fatigue Measure | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai et al., 2015 | 193 | N/A | No | Yes (older – ↑ fatigue) | Descriptive Correlational | Fatigue Scale for patients on HD | Participants recruited from six HD centers | Cross-sectional |

| Bonner, Wellard, & Caltabiano, 2007 | 92 | No | No | No | Cross-sectional Descriptive |

Fatigue Severity | Included patients on HD, PD, and who had received a kidney transplant | Included pre-dialysis patients Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Bossola, Luciani, & Tazza, 2009 | 62 | N/A | No | Yes (older – ↑ fatigue) | Cross-sectional | Scale SF-36 | Comparison of fatigue and non-fatigued participants on HD | Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Bossola, Stasio, Antocicco, & Tazza, 2013 | 68 | N/A | No | Yes (older – ↑ fatigue) | Cross-sectional | Six Yes or Noquestions based on Hardy and Studenski model | Described study sample of individuals on HD and limitations in detail | Dichotomous fatigue measure Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Chilcot et al., 2015 | 174 | Yes Caucasian – ↑ fatigue for fatigue severity only | No | No | Cross-sectional | Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (primary outcome) The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (secondary outcome) |

Measured fatigue severity and fatigue related functional impairment in individuals on HD | Cross-sectional |

| Jhamb et al., 2009 | 917 (705 included in adjusted models) | Yes Caucasian – ↑ fatigue | No | No | Longitudinal | SF-36 Vitality Scale | Large sample size Included individuals on HD and PD Longitudinal |

Fatigue was only measured at baseline and one year on dialysis through vitality scores |

| Liu, 2006 | 119 | N/A | Yes (female – ↑ fatigue) | Yes older – ↑ fatigue) | Cross-sectional Correlational |

Fatigue Assess Scale | Large sample size Individuals on HD |

Gender differences may have been attributed to Taiwan culture. Men are taught to avoid emotional expression Cross-sectional |

| O’Sullivan & McCarthy, 2007 | 46 | N/A | Yes (female – ↑ fatigue) | No | Cross-sectional Correlational Exploratory |

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory | The sample was representative for gender | Limited sample size Cross-sectional Average length of time patients receiving HD was minimal (2 years) |

| Wang et al., 2016 | 345 | N/A | No | Yes (older – ↑ fatigue) | Cross-sectional Descriptive Correlational |

FACIT-Fatigue | Participants recruited from two HD centers Large sample size |

Cross-sectional Only examined a few potential variables for fatigue |

Notes: N/A = not available, ↑ = increased.

Clinical Laboratory Values Associated with Fatigue

Experimental studies are also inconclusive about the relationship between fatigue and renal-specific laboratory parameters, which include Kt/V (quantifies dialysis treatment adequacy), parathyroid hormone level, anemia, and albumin (Bossola et al., 2009; Bossola, Di Stasio, Antocicco, & Tazza, 2013; Jhamb et al., 2009; Liu, 2006; Williams et al., 2007). Severe anemia is related to fatigue in general and several factors affect this relationship. Individuals with chronic kidney disease have a target maintenance hemoglobin level of 10 to 11.5 g/dL (Mimura, Tanaka, & Nangaku, 2015). The lower target hemoglobin level in this patient population may confound this correlation with fatigue. Bossola and colleagues (2009) and Jhamb and colleagues (2009) suggest that markers of systemic inflammation, C-reactive protein, and IL-6, and decreased levels of albumin are associated with fatigue in individuals with ESRD who are receiving dialysis. While Bossola and colleagues (2013) did not show statistical significance between IL-6 levels and fatigue, serum IL-6 levels did increase with fatigue. The lack of statistical significance could be attributed to small sample size. Table 2 depicts recent studies that have examined the association of clinical laboratory values with fatigue and the fatigue measure utilized, design, strengths, and weaknesses of these studies.

Table 2.

Clinical Laboratory Values Associated with Fatigue

| Author/Yea | Number of Participants | Kt/V | Serum Creatinine | Parathyroid Hormone | Anemia | Albumin | Markers of Inflammation | Design | Fatigue Measure | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bossola, Luciani, & Tazza, 2009 | 62 | N/A | Yes (↓) | No | N/A | Yes (↓) | Yes: IL-6 (↑) | Cross-sectional | SF-36 | Comparison of fatigue and non-fatigued participants on HD | Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Bossola, Stasio, Antocicco, & Tazza, 2013 | 68 | No | No | No | N/A | No | No | Cross-sectional | Six Yes or No questions based on the Hardy and Studenski model | All patients on HD received erythropoietin to maintain hemoglobin levels between 11- 12 g/L and treated to target PTH and albumin levels and Kt/V according to the guidelines | Dichotomous fatigue measure Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Jhamb, et al., 2009 | 917 (705 included in adjusted models) | No | Yes (↓) | N/A | No | Yes (↓) | Yes: C-reactive protein (↑) and IL-6 (↑) | Longitudinal | SF-36 vitality scale | Large sample size Included patients on HD and PD Longitudinal |

Fatigue was only measured at baseline and one year on dialysis through vitality scores |

| Liu, 2006 | 119 | No | N/A | N/A | No | No | N/A | Cross-sectional Correlational |

Fatigue Assess Scale | Large sample size of individuals on HD | Cross-sectional |

| Wang et al., 2016 | 345 | Yes Kt/V < 1.2 | Yes(↓) | N/A | No | No | N/A | Cross-sectional | FACIT-Fatigue | Participants recruited from two HD centers Large sample size |

Cross-sectional Only examined a few potential variables for fatigue |

| Williams, Crane, & Kring, 2007 | 36 | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | No | N/A | Cross-sectional Descriptive Correlational |

Fatigue Visual Analog Scale |

Homogenous sample of only African American women on HD. | Limited sample size Analyzed only African American women. |

Notes: N/A = not available, ↑ = increased, ↓ = decreased.

Limitations of these studies include cross-sectional designs, limited sample sizes, and varied fatigue measures. The cross-sectional nature of these studies decreases the ability to recognize the dynamic nature of fatigue experienced in this patient population. Small sample sizes undermine the validity of the studies and may mask a potential significant relationship. Lack of a gold-standard measure of fatigue in this patient population decreases the ability to compare and generalize results across studies and populations.

Factors Associated with Fatigue

Table 3 depicts recent studies that have examined the association of different factors with fatigue and the fatigue measure utilized, design, strengths, and weaknesses of these studies. Based on examined studies, there is strong evidence regarding correlations between the following and fatigue: increased body mass index (BMI), number of co-morbidities, decreased physical activity, and depression. Severity of fatigue is associated with increasing BMI and number of co-morbidities in several key studies (Bossola et al., 2009, 2013; Chilcot et al., 2015; Jhamb et al., 2009; Picariello, Moss-Morris, Macdougall, & Chilcot, 2017). Many individuals with ESRD have multiple co-morbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension which have contributed to the development of ESRD. It should be noted that a study by Bai, Lai, Lee, Chang, and Chiou (2015) showed no association between the number of co-morbidities and fatigue. This may be attributed to study exclusion criteria of certain co-morbidities, including clinical depression, cancer, and dementia (Bai et al., 2015). Decreased physical activity is often found in this patient population (Bossola, Vulpio, & Tazza, 2011). Though much research demonstrates that fatigue is associated with decreased physical activity it is unclear whether fatigue may cause physical inactivity or physical inactivity may contribute to fatigue (Bossola et al., 2011). Further investigation is warranted to better understand this important relationship. Fatigue and depression are related in the general population and research suggests that the association remains for individuals with ESRD (Bai et al, 2015; Bossola et al., 2009, 2013; Liu, 2006). High levels of social support have been associated with decreased fatigue severity in two studies, but limited research has examined this association (Bai et al., 2015; Karadag, Kilic, & Metin, 2013). One large study (n = 105) found fatigue scores were positively correlated with problems of sleep latency (Ali & Taha, 2017). Mixed results regarding the association between fatigue and education level remain (Ali & Taha, 2017; Liu, 2006; Wang et al., 2016; Zyga et al., 2015). Education level warrants further investigation to provide insights to providers on potential patients at higher risk of fatigue.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Fatigue

| Author/Year | Number of Participants | Body Mass Index | Co-morbidities | Physical Activity | Depression | Social Support | Sleep | Education Level | Design | Fatigue Measure | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali & Taha, 2017 | 105 | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A | Yes (sleep latency – ↑ fatigue) | No | Descriptive Cross-sectional |

Fatigue Severity Scale | Large sample size of patients on HD | Cross-sectional |

| Bai et al., 2015 | 193 | N/A | No | Yes – (↓) | Depression – (↑) | Yes (No spouse – ↑ fatigue) | N/A | N/A | Descriptive Correlational | Fatigue Scale for hemodialysis patients | Participants recruited from six HD centers | Cross-sectional |

| Bossola, Luciani, & Tazza, 2009 | 62 | N/A | Yes – (↑) | N/A | Depression – (↑) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Cross-sectional | SF-36 | Comparison of fatigue and non-fatigued participants on HD | Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Bossola, Stasio, Antocicco, & Tazza, 2013 | 68 | Yes – (↓) | Yes – (↓) | N/A | Depression – (↓) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Cross-sectional | Six Yes or No questions based Hardy and Studenski model | None of the patients on HD were on antidepressants | Dichotomous fatigue measure Limited sample size Cross-sectional |

| Chilcot et al., 2015 | 174 | Yes – (↑) | Yes – (↑) | Yes – (↓) | N/A | No (marital status does not impact fatigue) | N/A | N/A | Cross-sectional | Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (primary outcome) The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (secondary outcome) |

Measured fatigue severity and fatigue related functional impairment in individuals on HD | Cross-sectional |

| Jhamb et al., 2009 | 917 (705 included in adjusted models) | Yes – (↑) | Yes – (↑) | Yes – (↓) | N/A | N/A | Yes (↓) | N/A | Longitudinal | SF-36 vitality scale | Large sample size Included patients on HD and PD Longitudinal |

Fatigue was only measured at baseline and 1 year on dialysis through vitality scores |

| Karadag,Kilic, & Metin, 2013 | 73 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Social support – ↓ fatigue | N/A | N/A | Descriptive Cross-sectional |

Fatigue Severity Scale | Compared association of fatigue in individuals on HD with support from family, friends, special person, and overall | Cross-sectional Correlational analysis determined relationship between fatigue, effects may be bidirectional |

| Liu, 2006 | 119 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Depression – (↓) | N/A | N/A | No | Cross-sectional Correlational |

Fatigue Assess Scale | Large sample size of individuals on HD | All patients were married Cross-sectional |

| Wang et al., 2016 | 345 | No | Yes | Yes – (↑) | N/A | No | N/A | No | Cross-sectional | FACIT-Fatigue | Participants recruited from two HD centers Large sample size |

Cross-sectional Only examined a few potential variables for fatigue |

| Zyga et al., 2015 | 129 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes – education | Cross-sectional | Fatigue Assessment Scale | Participants recruited from two HD centers Large sample size |

Cross-sectional Physicians, nurses, and other health care providers were present during survey administration |

Limitations of these studies include mostly cross-sectional designs, limited sample sizes, few studies, and bidirectional nature of variables associate with fatigue. Use of correlational analysis to determine the relationship between fatigue and physical activity, fatigue and depression, and fatigue and social support can depict effects that may be bidirectional. Therefore, causality cannot be determined without further investigation.

Assessment of Fatigue in the Clinical Setting

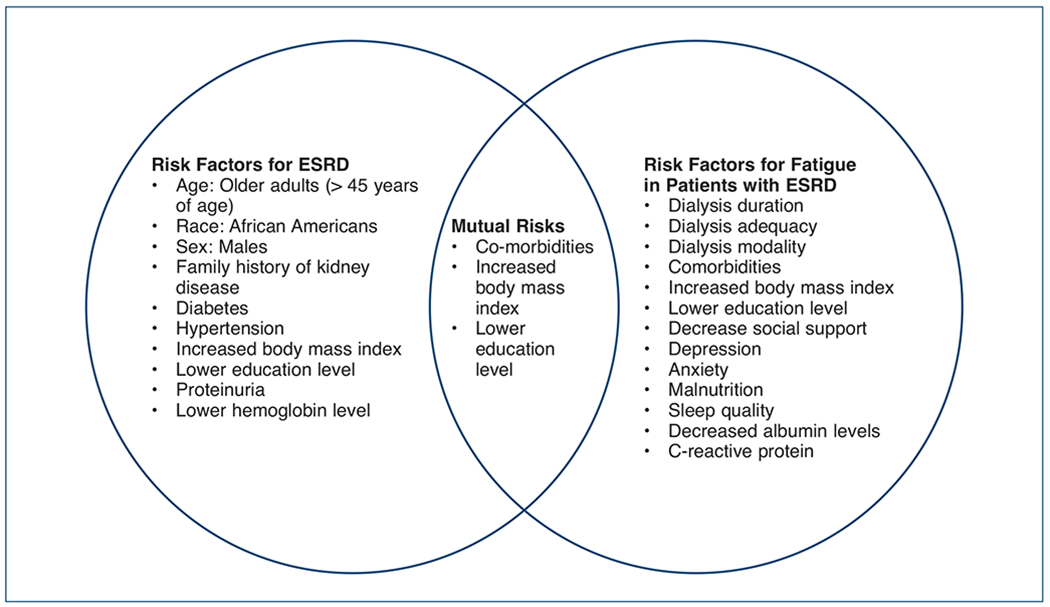

It is important to recognize indicators associated with fatigue in order to assess fatigue effectively in this patient population. Figure 1 represents risk factors associated with ESRD, fatigue, and mutual risk factors between the two (Hsu Iribarren, McCullough, Darbinian, & Go, 2009). Health care providers play a critical role in assessment and management of fatigue in this patient population. Fatigue is important to assess because it is one of the most burdensome symptoms encountered by patients with ESRD affecting not only quality of life, but increasing their risk for cardiovascular events and contributing to higher mortality rates (Bonner et al., 2007; Bossola, DiStasio, Antocicco, Panico et al., 2015; Flythe et al, 2015; Jablonski, 2007; Jhamb et al., 2009; Koyama et al., 2010; Letchmi et al., 2011; O’Sullivan & McCarthy, 2009; Wang et al., 2017; Zyga et al., 2015). Regardless, fatigue remains under-recognized and difficult to manage ( Ju et al., 2018). Various measures exist to assess the level of fatigue experienced. Unfortunately, there is no gold-standard measure of fatigue in this patient population (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Risk Factors Associated with ESRD and Fatigue in Patients with ESRD

Based on study findings, Chao, Huang, and Chiang (2016) suggested that the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) demonstrated independent and significant correlations with key outcomes in patients with ESRD, which include age, serum albumin, creatinine, and frailty severity. This study had a sample size of 46, and only seven fatigue instruments were examined. Ju and colleagues (2018) suggested, based on study findings, that a core outcome measure for fatigue should incorporate a balance between generalizability and sensitivity, with items phrased to accurately measure the concept of fatigue in individuals undergoing dialysis. Furthermore, to gain a more comprehensive understanding regarding experience of fatigue, health care providers should directly ask patients how they are feeling and about the patient’s preferences in addressing and managing their fatigue (Ju et al., 2018). Assessment of fatigue should occur repeatedly, perhaps at follow-up appointments or weekly at dialysis treatment. Time of assessment of fatigue is essential to keep in mind as fatigue is often increased directly after dialysis, but can resolve as time passes (Ju et al., 2018). It should also be noted that fatigue can be a manifestation of depression, which is also common among individuals with ESRD (Horigan, Schneider, Docherty, & Barroso, 2013).

Clinical Management of Fatigue

Fatigue in this patient population is unique due to the multidimensional nature of dialysis, and in turn, is difficult to manage. Effective treatment of fatigue is further complicated in this patient population because we do not understand the cause(s) of fatigue. Currently, there is nominal research examining genetic associations with fatigue. Some research has examined potential medical treatment options for fatigue, such as the correction of anemia and physical activity to improve clinical outcomes with varying success (Bossola et al., 2011; Horigan et al., 2013; Liu, 2006; Williams et al., 2007; Yurtkuran, Alp, Yurtkuran, & Dilek, 2007). Many of the research studies examining interventions to prevent or mitigate fatigue in individuals with ESRD are limited by small sample sizes and a lack of randomization (Bossola et al., 2011). Interventions to prevent and mitigate fatigue include pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies (see Table 4). Pharmacological interventions to mitigate fatigue include vitamin C and L-carnitine (Brass et al., 2001; Fukuda et al., 2015; Singer, 2011). Nonpharmacological interventions to mitigate fatigue include exercise, acupressure, trans cutaneous electrical acupoint simulation (TEAS), psychological interventions, and correction of anemia (Chang, Cheng, Lin, Gau, & Choa, 2010; Cho & Sohng, 2014; Cho & Tsay, 2004; Hadadian et al., 2016; Johansen et al. 2012; Keown et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2016; Sabouhi, Kalani, Valiani, Mortazavi, & Bemanian, 2013; Yurtkuran et al., 2007). Table 4 depicts the most recent and sentinel studies addressing pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in individuals with ESRD.

Table 4.

Fatigue Interventions: Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological

| Author/Year | Intervention and Type of Dialysis | Participants | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Interventions | Singer, 2011 | Vitamin C 250 mg, 3 times per week (oral) Individuals on HD or PD |

48 intervention 48 placebo |

No improvement in fatigue. |

| Fukuda et al., 2015 | 500 mg carnitine within a nutritional drink, 3 times per week for 12 weeks (oral) Individuals on HD |

87 intervention 86 placebo |

No improvement in fatigue. | |

| Brass et al., 2001 | Study A: IV 20 mg/kg L-carnitine after each dialysis session for 20 weeks. Study B: IV 10 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg, or 40 mg/kg L-carnitine after each dialysis session for 20 weeks. |

Study A: 28 placebo 28 (20 mg/kg) Study B: 33 placebo 32 (10 mg/kg) 30 (20 mg/kg) 32 (40 mg/kg) |

Study A: Deceased level of fatigue for intervention group. Study B: Decreased level of fatigue for intervention group, no difference in level of fatigue between intervention groups. |

|

| Non-Pharmacological Interventions | Chang et al., 2010 | Individuals on HD Physical activity: leg ergometry exercise within the first hour of each HD session for 30 min for 8 weeks. Individuals on HD |

35 control 36 experimental |

Leg erometry exercise decreased fatigue in active and sedentary HD patients. |

| Yurtkuran et al., 2007 | Group yoga exercise, 30 minutes per day, twice a week for 3 months. Individuals on HD |

18 control 19 experimental |

Group yoga exercise decreased fatigue levels by 55%. | |

| Cho & Sohng, 2014 | Virtual reality exercise program (Nintendo Wii Fit Plus) for 40 minutes, 3 times per week for 8 weeks. Individuals on HD |

23 control 23 experimental |

Level of fatigue decreased in the exercise group. | |

| Sabouhi et al., 2013 | Experimental and placebo groups received acupressure intervention during HD on six acupoints with massage for 20 minutes, 3 days per week for 4 weeks. Placebo group-intervention performed, but 1cm away from intervention site. Individuals on HD |

32 control 32 placebo 32 experimental |

Experimental group experienced less fatigue severity compared to placebo and control. | |

| Cho & Tsay, 2004 | Experimental group received acupoint massage for 12 minutes per day, 3 times per week, for 4 weeks. | 30 control 28 experimental |

Experimental group demonstrated greater improvement in fatigue compared to control group. | |

| Hadadian et al., 2016 | Individuals on HD Trans Cutaneous Electrical Acupoint Simulation (TEAS) for 5 minutes, 2-3 times per week, for 5 weeks. |

28 control 28 experimental |

Experimental group had a better recovery rate of fatigue compared to the control group. | |

| Keown et al., 2010 | Individuals on HD Epoetin alfa intravenously 3 times per week to attain a hemoglobin of 9.5–11.0 g/dL (low-target group, n=40), or 11.5–13.0 g/dL (high-target group, n=38) for 6 months. |

40 control 78 experimental |

Experimental group had improvement in fatigue compared to control group. |

Generally, exercise involving resistance training and/or aerobic activity, as well as yoga, are safe and positive for patients on dialysis, especially individuals with low baseline physical functioning self-opinions (Bossola et al., 2011). Several studies suggest acupressure and TEAS interventions are favorable, though a systematic review by Kim and colleagues (2016) noted there is a very low quality of evidence of short-term effects of acupressure as an intervention for fatigue in this patient population. Furthermore, none of the studies specified the occurrence of severe adverse events nor assessed pain outcomes related to the intervention (Kim et al., 2016). Research examining the efficacy of counselling to reduce fatigue and improve the quality of life among patients on dialysis is ongoing (van der Borg, Schipper, & Abma, 2016). This study should conclude in 2019 and results should be available shortly thereafter. This is the first protocol to utilize mixed methods, including a randomized control trial, to examine a psychosocial intervention for reducing fatigue and improving quality of life in individuals with ESRD (van der Borg et al., 2016). A systematic review by Johansen and colleagues (2012), examining 15 articles, concluded that partial correction of anemia with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) leads to improvement of fatigue especially in individuals with a baseline hemoglobin level of less than 10 g/dL.

It is essential to note there is no standardization of interventions nor gold-standard measure of fatigue utilized. The lack of a standardized intervention limits our ability to determine which intervention is most impactful. Sabouhi and colleagues (2013) and Cho and Tsay (2004) demonstrated an acupressure intervention had positive effects on fatigue, but we are unable to determine which of the two methods is more effective due to lack of a standardized measure of fatigue. In the future, it will be helpful to determine a gold standard measure for fatigue in this patient population to compare effectiveness of interventions to mitigate fatigue. Additionally, future research studies need to include large randomized samples to increase generalizability of findings.

Key Findings

Research on fatigue in patients with ESRD has demonstrated that fatigue is a serious issue that needs to be addressed to improve quality of life and poor health outcomes. In this article, we presented a definition and overview of fatigue, factors contributing to fatigue, assessment of fatigue in the clinical setting, and clinical management of fatigue.

There are several key limitations regarding research examining fatigue in individuals with ESRD. A majority of the studies had a limited sample size and cross-sectional study design. Utilization of a cross-sectional design hinders the ability to capture the dynamic nature of fatigue experienced in this patient population. Lack of a gold standard measure of fatigue in this patient population is concerning. Future research must examine the best measure of fatigue in this patient population to determine a gold standard measure and increase the ability to compare and generalize results. Possible bidirectional nature of variables (physical activity, depression, and social support) associated with fatigue demonstrates that causality cannot be determined without further investigation.

Conclusion

There is much to learn regarding fatigue in this patient population, including causes, a gold standard measure for assessment, and effective management of fatigue. To address the unique and multifaceted nature of fatigue in this patient population related to dialysis, we think assessment with a standardized validated measure and interventions aimed to address the various dimensions of fatigue will produce the best results to mitigate the detrimental symptom of fatigue.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to acknowledge support provided to the primary author from the NRSA Predoctoral Fellowship: Multiple Chronic Conditions Interdisciplinary Nurse Scientist Training and the VA Quality Scholars Fellowship.

Footnotes

Statement of Disclosure: The authors reported no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this continuing nursing education activity.

Contributor Information

Christine Horvat Davey, Research Associate, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; VAQS Post doctoral Fellow, Cleveland VA, Cleveland, OH; member of ANNA’s Black Swamp Chapter.

Allison R. Webel, Associate Professor of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

Ashwini R. Sehgal, Nephrologist, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH; Director and Duncan Neuhauser Professor of Community Health Improvement, Center for Reducing Health Disparities School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH

Joachim G. Voss, Professor of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University; Director of the Sarah Cole Hirsh Institute for Evidence-Based Practice, the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

Anne M. Huml, Nephrologist, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH; Instructor of Medicine, the Center for Reducing Health Disparities, the MetroHealth System, Cleveland, OH

References

- Ali HH, & Taha NM (2017). Fatigue, depression and sleep disturbance among hemodialysis patients. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 6(3), 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Lai LY, Lee BO, Chang YY, & Chiou CP (2015). The impact of depression on fatigue in patients with hemodialysis: A correlational study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(13-14), 2014–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner A, Wellard S, & Caltabiano M (2007). Levels of fatigue in people with ESRD living in far North Queensland. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(1), 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossola M, Luciani G, & Tazza L (2009). Fatigue and its correlates in chronic hemodialysis patients. Blood Purification, 28(3), 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossola M, Di Stasio E, Antocicco M, Panico L, Pepe G, & Tazza L (2015). Fatigue is associated with increased risk of mortality in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Nephron, 130(2), 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossola M, Di Stasio E, Antocicco M, & Tazza L (2013). Qualities of fatigue in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Hemodialysis International, 17(1), 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossola M, Di Stasio E, Giungi S, Rosa F, & Tazza L (2015). Fatigue is associated with serum interleukin-6 levels and symptoms of depression in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(3), 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossola M, Vulpio C, & Tazza L (2011). Fatigue in chronic dialysis patients. Seminars in Dialysis, 24(5), 550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass EP, Adler S, Sietsema KE, Hiatt WR, Orlando AM, & Amato A (2001). Intravenous L-carnitine increases plasma carnitine, reduces fatigue, and may preserve exercise capacity in hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 37(5), 1018–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Cheng SY, Lin M, Gau FY, & Choa YF (2010). The effectiveness of intradialytic leg ergometry exercise for improving sedentary life style and fatigue among patients with chronic kidney disease: A randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(11), 1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CT, Huang JW, & Chiang CK (2016). Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy – The fatigue scale exhibits stronger associations with clinical parameters in chronic dialysis patients compared to other fatigue-assessing instruments. PeerJ, 4, e1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcot J, Moss-Morris R, Artom M, Harden L, Picariello F, Hughes H, … Macdougall IC (2015). Psychosocial and clinical correlates of fatigue in haemodialysis patients: The importance of patients’ illness cognitions and behaviours. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(3), 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, & Sohng KY (2014). The effect of a virtual reality exercise program on physical fitness, body composition, and fatigue in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 26(10), 1661–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YC, & Tsay SL (2004). The effect of acupressure with massage on fatigue and depression in patients with end-stage renal disease. Journal of Nursing Research, 12(1), 51–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison SN, & Jhangri GS (2010). Impact of pain and symptom burden on the health-related quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Journal of Pain Symptom Management, 39(3), 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J, & Mahjoub SZ (2013). Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 31(5), 562–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flythe JE, Powell JD, Poulton CJ., Westreich KD, Handler L, Reeve BB, & Carey TS. (2015). Patient-reported outcome instruments for physical symptoms among patients receiving maintenance dialysis: A systematic review. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 66(6), 1033–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Koyama H, Kondo K, Fujii H, Hirayama Y, Tabata T, … Nishizawa Y. (2015). Effects of nutritional supplementation on fatigue, and autonomic and immune dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0119578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadadian F, Sohrabi N, Farokhpayam M, Farokhpayam H, Towhidi F, Fayazi S, … Abdi A. (2016). The effects of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS) on fatigue in haemodialysis patients. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 10(9), YC01–YC04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horigan AE, Schneider SM, Docherty S, & Barroso J (2013). The experience and self-management of fatigue in hemodialysis patients. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 40(2), 113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CY, Iribarren C, McCulloch CE, Darbinian J, & Go AS (2009). Risk factors for end-stage renal disease: 25-year follow-up. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(4), 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski A (2007). The multidimensional characteristics of symptoms reported by patients on hemodialysis. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 34(1), 29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamb M, Argyropoulos C, Steel JL, Plantinga L, Wu AW, Fink N, … Unruh ML. (2009). Correlates and outcomes of fatigue among incident dialysis patients. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 4(11), 1779–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamb M, Liang K, Yabes J, Steel JL, Dew MA, Shah N, & Unruh M (2013). Prevalence and correlates of fatigue in CKD and ESRD: Are sleep disorders a key to understanding fatigue? American Journal of Nephrology, 38(6), 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen KL, Finkelstein FO, Revicki DA, Evans C, Wan S, Gitlin M, & Agodoa IL (2012). Systematic review of the impact of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on fatigue in dialysis patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 27(6), 2418–2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju A, Unruh M, Davison S, Dapueto J, Dew MA, Fluck R, … Tong A. (2018). Establishing a core outcome measure for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis: A Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology – Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) Consensus Workshop report. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 72(1), 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karadag E, Kilic SP, & Metin O (2013). Relationship between fatigue and social support in hemodialysis patients. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(2), 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keown PA, Churchill DN, Poulin-Costello M, Lei L, Gantotti S, Agodoa I, … Mayne TJ. (2010). Dialysis patients treated with Epoetin alfa show improved anemia symptoms: A new analysis of the Canadian Erythropoietin Study Group trial. Hemodialysis International, 14(2), 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Lee MS, Kim TH, Kang JW, Choi TY, & Lee JD (2016). Acupuncture and related interventions for symptoms of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, CD00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama H, Fukuda S, Shoji T, Inaba M, Tsujimoto Y, Tabata T, … Nishizawa Y. (2010). Fatigue is a predictor for cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 5(4), 659–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letchmi S, Das S, Halim H, Zakariah FA, Hassan H, Mat S, & Packiavathy R (2011). Fatigue experienced by patients receiving maintenance dialysis in hemodialysis units. Nursing & Health Sciences, 13(1), 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HE (2006). Fatigue and associated factors in hemodialysis patients in Taiwan. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(1), 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura I, Tanaka T, & Nangaku M (2015). How the target hemoglobin of renal anemia should be. Nephron, 131(3), 202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan D, & McCarthy G (2009). Exploring the symptom of fatigue in patients with end stage renal disease. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 36(1), 37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picariello F, Moss-Morris R, Macdougall IC, & Chilcot J (2017). The role of psychological factors in fatigue among end-stage kidney disease patients: A critical review. Clinical Kidney Journal, 10(1), 79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabouhi F, Kalani L, Valiani M, Mortazavi M, & Bemanian M (2013). Effect of acupressure on fatigue in patients on hemodialysis. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 18(6), 429–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipper K, & Abma TA. (2011). Coping, family and mastery: Top priorities for social science research by patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 26(10), 3189–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer RF (2011). Vitamin C supplementation in kidney failure: Effect of uraemic symptoms. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 26(2), 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Borg WE, Schipper K, & Abma TA (2016). Protocol of a mixed method, randomized controlled study to assess the efficacy of a psychosocial intervention to reduce fatigue in patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD). BMC Nephrology, 17(1), 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Zang XY, Fu SH, Bai J, Liu JD, Tian L, … Zhao Y. (2016). Factors related to fatigue in Chinese patients with end-stage renal disease receiving maintenance hemodialysis: A multi-center cross-sectional study. Renal Failure, 38(3), 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Yin J, Miller AH, & Xiao C (2017). A systematic review of the association between fatigue and genetic polymorphisms. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 62, 230–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AG, Crane PB, & Kring D (2007). Fatigue in African American women on hemodialysis. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 34(6), 610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurtkuran M, Alp A, Yurtkuran M, & Dilek K (2007). A modified yoga-based exercise program in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 15(3), 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyga S, Alikari V, Sachlas A, Fradelos EC, Stathoulis J, Panoutsopoulos G, … Lavdaniti M. (2015). Assessment of fatigue in end stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis: Prevalence and associated factors. Medical Archives, 69(6), 376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]