Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Non-invasive fibrosis markers are routinely used in patients with liver disease. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is recognized as a highly accurate methodology, but a reliable blood test for fibrosis would be useful. We examined performance characteristics of the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) Index compared to MRE in a cohort including those with HCV, HIV, and HCV/HIV.

METHODS:

Subjects enrolled in the Miami Adult Studies on HIV (MASH) cohort underwent MRE and blood sampling. The ELF Index was scored and receiver-operator curves constructed to determine optimal cutoff levels relative to performance characteristics. Cytokine testing was performed to identify new markers to enhance non-invasive marker development.

RESULTS:

The ELF Index was determined in 459 subjects; more than half were male, non-white, and HIV-infected. MRE was obtained on a subset of 283 subjects and the group that had both studies served as the basis of the receiver-operator curve analysis. At an ELF Index of >10.633 the area under the curve for cirrhosis (Metavir F4, MRE>4.62 kPa) was 0.986 (95% CI=0.994–0.996; p< 0.001) with a specificity of 100%. For advanced fibrosis (Metavir F3/4) an ELF cutoff of 10 was associated with poor sensitivity but high specificity (98.9%, 95%CI=96.7–99.8%) with an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI=0.749–0.845). ELF Index performance characteristics exceeded FIB-4 performance. HCV and age were associated with increased fibrosis (p<0.05) in a multivariable model. IP-10 was found to be a promising biomarker for improvement of non-invasive prediction algorithms.

CONCLUSIONS:

The ELF Index was a highly sensitive and specific marker of cirrhosis, even among HIV-infected individuals, when compared with MRE. IP-10 may be a biomarker that can enhance performance characteristics further, but additional validation is required.

Keywords: MRE, ELF, Fibrosis, Biomarkers, HCV, HIV

INTRODUCTION

Though liver biopsy is considered by many the “gold standard” for evaluation of hepatic fibrosis, the last decade has witnessed the emergence and acceptance of a variety of newer non-invasive methodologies for the assessment of fibrosis. Advantages of these assays include better patient acceptance, wider availability for cohort or population-based screening, and relatively high degrees of concordance with results obtained by evaluation of liver histology for clinically relevant outcomes (e.g., advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis). [1–3] While many reports provide comparisons of non-invasive methods with liver histology and occasionally with each other, few studies have examined and optimized the relationship between magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Index (ELF). A small study (n=60) reported the diagnostic performance in terms of area under the curve (AUC) for MRE to be 0.94 vs. 0.63 for ELF in discriminating F3–F4 fibrosis from lower stages [4]

The Miami Adult Studies on HIV (MASH) cohort was created to assess the role of cocaine use as a contributor to development of hepatic fibrosis in participants infected with hepatitis C (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or uninfected controls. Eligible patients underwent both MRE and ELF Index measurement, thus permitting assessment and refinement of cutoff values utilized for each non-invasive method. Furthermore, performance of cytokine panels allowed evaluation of additional biomarkers that may be associated with hepatic fibrosis. These tools, developed at baseline enrollment in this cohort, will allow for long-term longitudinal assessment to better characterize the putative effects of cocaine use in HCV, HIV or HCV/HIV coinfected populations.

METHODS

MASH Cohort

The MASH cohort was established in 2001 and has been funded since 2015 by the National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA) to study the association between cocaine exposure and development of liver disease in participants with HCV, HIV, HCV/HIV coinfection, or uninfected controls. Cocaine non-users were also recruited to determine the impact of cocaine use alone. Eligible participants were >40 years old, had a BMI (in kg/m2) >18 but <40, and had controlled comorbid diseases (diabetes, symptomatic cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome). Subjects with known cirrhosis, HBV infection, carcinoma, who were pregnant, had heavy tobacco use (defined as >20 cigarettes/day) or admitted to other illicit drug use were excluded. All subjects provided baseline demographic data as well as blood samples for laboratory analyses. Drug, alcohol, and tobacco use and frequency questionnaires were administered and confirmed by blood and urine toxicology screening. Cocaine users were defined as participants who admitted to cocaine use by self-report and/or had at least one positive urine toxicology.

The long-term goal of this cohort is to determine the role of genetic and viral factors in liver disease progression. Longitudinal follow-up is currently in progress. This analysis is designed to establish optimal cutoff levels for comparison of MRE with the ELF Index which can be used to evaluate disease stages with more frequent sampling across the cohort than can be accomplished with MRE.

Evaluation of Hepatic Fibrosis

MRE was conducted on a 3T Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma MRI and mean stiffness of the liver was calculated through an inversion algorithm that generates elastogram/stiffness maps of the tissue in kilopascals (kPa). The ELF Index is based upon an algorithm that utilizes serum-derived values for hyaluronic acid (HA), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP-1), and Human Procollagen III (PIIINP) levels calculated as follows: [ELF Index=−7.412+(ln (HA)×0.681)+(ln(PIIINP)×0.775)+ (ln(TIMP1)×0.494)+10]. [5] Levels were quantified using the following assays: Human PIIINP ELISA Kit (Cloud-Clone Corp), Human HA Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems), and Human TIMP-1 ELISA (Abcam). The fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) parameter was calculated as described using age, ALT, AST, and platelet count. [6]

Optimization of Test Characteristics

Using MRE cutoff values which were previously compared to histologic characterization of the Metavir disease stage, receiver-operator curves (ROC) were used to optimize ELF Index cutoff values, targeting cirrhosis (Metavir F4) and advanced fibrosis (Metavir F3/4). A range of optimal cutoff values has been described in the literature.[7] In our study cohort, results of >4.62 kPa were classified as cirrhosis and >3.7 kPa as advanced fibrosis. Area Under the Receiver Operator Curves (AUROCs) were determined using MEDCALC Version 15.1 software (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium).

Evaluation of Cytokines/Chemokines

Cytokines and chemokines in the serum of MASH enrollees were quantified in serum samples collected at baseline. Included were TGF-beta, TNF-alpha, MIP-1 (alpha and beta), IFN alpha 2, IFN gamma, IL-1 beta, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-17, IL-22, IL-33, Rantes, MIG, GCP-2, ITAC, IP-10, and MCP-1. Briefly, immune markers were quantified by analyte-specific bead-based Luminex multiplex immunoassays (EMD Millipore Corporation). Mean fluorescence intensity for each analyte was detected on a flow-based Luminex platform. Concentrations were calculated using a standard curve derived from the known reference concentration supplied by the manufacturer. Concentrations below the sensitivity limit of detection (LOD) of the method were coded as a decimal unit below the LOD value.

Statistical Evaluation

Parametric and non-parametric tests were utilized as indicated and appropriate for data type. A p-value of 0.05 with a two-tailed hypothesis was used. Multivariable linear regression was employed to analyze cytokines associated with fibrosis following non-parametric univariate analysis.

RESULTS

Though new subjects continue to be entered, the baseline analysis for comparisons between MRE and ELF was truncated following enrollment of 459 individuals. A subset of the larger cohort was used to evaluate receiver-operator characteristics of MRE vs. ELF. As shown in Table 1, the total group and the MRE subset were generally well matched in terms of key demographic and clinical characteristics. This is also true of the 71 participants who did not have HCV or HIV but who underwent both MRE and ELF evaluation. HIV prevalence was slightly less in the group that underwent MRE and had greater female representation than those that did not undergo MRE. As expected, viral uninfected participants had no significant fibrosis.

Table 1:

Demographic Characteristics of Cohort Participants: Comparison of Subjects Who Underwent MRE vs. No MRE

| ALL | MRE | No MRE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 459 | 283 | 176 | |

| Age: Mean (Range) | 53.3 (23–78) | 53.0 (23–78) | 53.9 (26–73) | 0.22 |

| Other % | 4.8 | 4.6 | 5.1 | |

| Sex (% Male) | 59 | 55 | 65.3 | 0.03 |

| HIV (% Positive) | 76.4 | 73.1 | 81.7 | 0.03 |

| HCV (% Positive) | 20.3 | 18.7 | 22.7 | 0.30 |

| HCV/HIV Uninfected (%) | 22.4 | 25.1 | 18.2 | |

| (Total n) | (277) | (160) | (117) | |

| ALT: Mean/S.D. | 25.3 ±33.0 | 24.2 ±25.2 | 26.8 ±43.1 | 0.42 |

| Cocaine Use (% baseline) | 35.9 | 37.1 | 34.1 | 0.51 |

The ELF Index, as well as FIB-4, were calculated for all enrollees in the MASH cohort to date. The ELF Index mean was 9.06 (SEM ± 0.0364) and ranged from 4.07 to 11.63 (1st to 3rd quartile 8.65 to 9.49). The FIB-4 mean was 1.40 (SEM ± 0.0843) and ranged from 0.29 to 29.43. The median was 9.05. MRE was obtained on 283 individuals. Failure to obtain MRE was primarily due to presence of relative contraindications to performance of MRE at the research site, including prior surgical placement of metal mesh, orthopedic prosthetics or other hardware. The mean MRE result was 2.4 kPa (SEM ± 0.0462) and ranged from 1.44 to 9.43. The median was 2.25. The mean FIB-4 was 1.39 (SEM + 0.08) with a median 1.11.

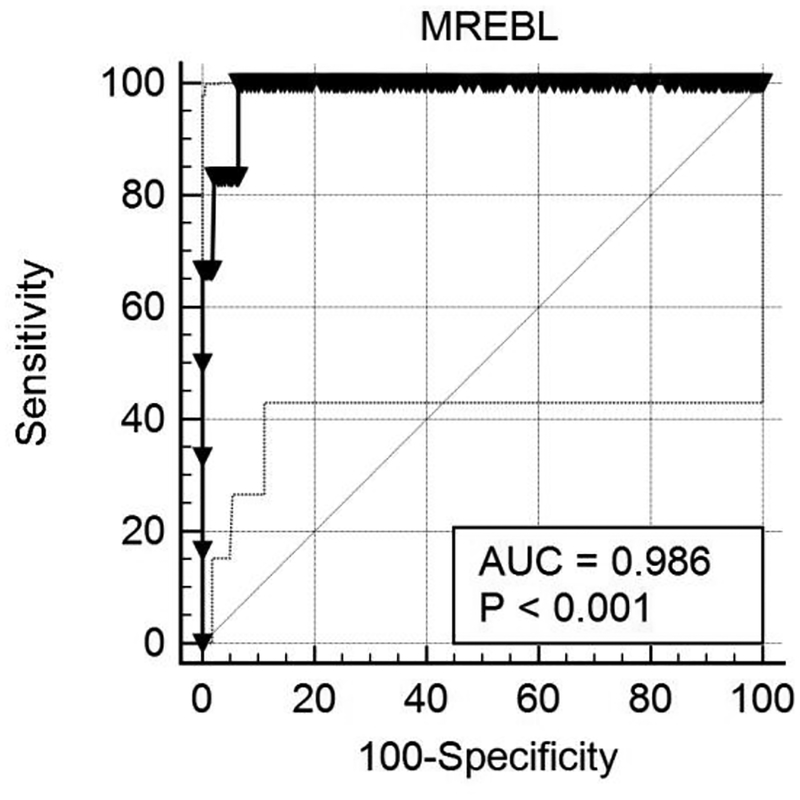

The determination of optimal operational characteristics for the ELF index, using MRE as the reference methodology, was performed by comparisons of area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity and specificity at multiple cutoff levels. The optimal “best fit” is shown in Figure 1 below. At an ELF Index cutoff of >10.633, the area under the curve for cirrhosis (Metavir F4, MRE>4.62 kPa) was 0.986 (95% CI 0.994–0.996; p< 0.001). The sensitivity for MRE-determined cirrhosis was 66.67% (95% CI 22–95%) with a specificity of 100% (95% CI 98.7–100). Advanced fibrosis was defined as an MRE cutoff of >3.7 kPa. ELF index did not perform as well in diagnosing advanced fibrosis as it did for cirrhosis. For advanced fibrosis, an ELF index of 10 or more was associated with a significant loss of sensitivity (26.3%) though specificity was maintained (98.9%, 95%CI= 96.7–99.8%) with an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI= 0.749–0.845). In contrast, FIB-4 > 3.25 (advanced fibrosis) was not highly correlated with either MRE (Spearman r= 0.22) or ELF (Spearman r=0.29).

Figure 1:

Receiver-Operator Curve using ELF Index cut-off greater than 10.633. At an optimal ELF Index cutoff of >10.633 the area under the curve for cirrhosis (Metavir F4, MRE>4.62 kPa) prediction was 0.986 (95% CI 0.994–0.996; p< 0.001). The sensitivity for this MRE-determined cirrhosis was 66.67% (95% CI = 22–95%) with a specificity of 100% (95% CI =98.7–100). MREBL: MRE levels at MASH cohort baseline.

The presence of cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis by ELF (Index ≥ 10) was evaluated by best subset regression models of multiple factors, including age, gender, ethnicity, HIV status, HCV status, and current or any reported prior history of cocaine use. HCV status, age, race/ethnicity, and history of cocaine use were the most highly associated independent variables. A least square regression model of these factors revealed that HCV status (p<0.0001), and age (p< 0.05) were the key factors associated with fibrosis. Race/ethnicity and prior cocaine use fell out of the final model.

Association of Cytokines and Chemokines with Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis

Cytokine and chemokine markers were obtained and characterized by their univariate association with hepatic fibrosis, as classified by ELF, using a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. The goal was to identify factors that might eventually be incorporated into more robust models of hepatic fibrosis. In univariate analysis (Wilcoxon Rank Sum) 6/22 cytokine/chemokine markers were either positively or negatively associated with advanced fibrosis and one approached significance. These include IL-4(−), IL-8(+), IP-10 (+), Rantes (−), TGF-beta1(−), and ITAC(+). There was also a strong trend for an association with MCP-1(0.06). A multivariable linear regression model using these univariate factors revealed that IP-10 (p<0.0001) was the most important factor associated with development of advanced fibrosis.

DISCUSSION

Compared to even a decade ago, a variety of non-invasive tools are now available for assessment and characterization of hepatic fibrosis. These tests each exhibit both strengths and weaknesses in their implementation and use. MRE has emerged as a leading methodology for determination of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis. It examines the whole liver and is highly correlated with liver biopsy interpretation. [8] The list of contraindications to having an MRI is relatively circumscribed, though individual radiologists may adhere to more restrictive criteria. [9] However, MRE is more expensive than ultrasound-based elastography, requires more time than drawing blood for a lab test, and may fail in some patients (e.g., claustrophobia). In this study MRE is the core assessment methodology for the MASH cohort. However, alternative methodologies are needed for assessment at interim timepoints and for those enrollees who cannot undergo MRE. The ELF Index has emerged as a highly sensitive non-invasive marker. Though not commercially available in the United States at this time, the test is marketed in both Europe and India. Pricing in the U.S. is not available, but the test can be run on an automated platform which allows rapid throughput. It has been validated against liver biopsy in patients with hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and NASH. [5, 10–12] However, there are limited studies that have examined performance characteristics compared with MRE. In a 60 patient fibrosis assessment study, ELF had low diagnostic performance with an AUC-0.63 for advanced fibrosis and was not highly correlated with MRE at any stage of fibrosis. [4] Using a much larger cohort, we found ELF provided better accuracy with an AUC of 0.80. Indeed, at the specified cutoff values the specificity of ELF approaches nearly 100% though sensitivity is lower.

ELF has been also evaluated in the context of HIV infection in prior studies, but not in direct comparison with MRE. Biochemical non-invasive marker assays tend to perform poorly in the setting of HIV infected relative to HIV uninfected persons. [13] Peters and colleagues examined performance characteristics of ELF in a large cohort of HIV-infected women and found that ELF was superior to APRI or FIB-4 in the prediction of mortality in this population.[14] ELF also correlated with acoustic transient elastography results in the same cohort. [15]

Application of the optimal cutoff values for ELF revealed a high level of association between putative hepatic fibrosis and HCV infection, which is not surprising. We did not observe an association with HIV, but there was a clear relationship between hepatic fibrosis and patient reporting of prior cocaine use in the univariate model. This relationship will be explored further as the longitudinal cohort matures and specific testing for cocaine, rather than historical reporting, is utilized to support the role of cocaine in development of liver fibrosis.

We also evaluated an array of cytokines and chemokines which have been associated with development of hepatic fibrosis. Following univariate analysis, several putative markers of advanced fibrosis, as determined by ELF, were identified. Multivariable analysis revealed that IP-10 was an important independent marker of hepatic fibrosis. IP-10 (interferon gamma-inducible protein-10) is a chemokine expressed by hepatocytes that binds to CXCR3 after acute liver cell injury. [16] Correlations with IP-10 and necroinflammatory responses and fibrosis in HCV have also been reported. [17] A recent study of 180 patients with chronic hepatitis B infection suggested that elevated IP-10 were also associated with hepatic fibrosis. [18] Our data and prior findings support a role for the prospective assessment of IP-10 levels as a predictor of hepatic fibrosis which, when combined with ELF parameters could potentially improve the performance characteristics of the current assay, and will be explored.

In summary, we have assessed the efficacy of the ELF Index to provide highly specific predictive results for advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in a large prospective cohort of cocaine users, with/without HCV and/or HIV infection. ELF is viable alternative to MRE for diagnosis of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis among persons living with HCV and HCV/HIV coinfection. Exploratory analyses suggest that IP-10 may also be strongly associated with fibrosis and is a suitable candidate for further evaluation as an adjunctive marker of hepatic fibrosis.

Key point.

Progressive liver disease occurs in those with HCV and/or HIV. MR Elastography (MRE) highly correlates with liver biopsy and predicts fibrosis stage. ELF Index correlates with MRE in predicting fibrosis stage. IP-10 may be useful as another non-invasive fibrosis marker.

Funding

This study was supported by NIH/NIDA 5U01DA040381 to MB.

We would like to acknowledge the Research Flow Cytometry Core at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and the Digestive Health Center (NIDDK P30 DK078392); and NIH/NIBIBR37 EB001981 to RLE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Potential competing interests

All authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- [1].Singh S, Muir AJ, Dieterich DT, Falck-Ytter YT, American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the Role of Elastography in Chronic Liver Diseases, Gastroenterology 152(6) (2017) 1544–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shiha G, Ibrahim A, Helmy A, Sarin SK, Omata M, Kumar A, Bernstien D, Maruyama H, Saraswat V, Chawla Y, Hamid S, Abbas Z, Bedossa P, Sakhuja P, Elmahatab M, Lim SG, Lesmana L, Sollano J, Jia JD, Abbas B, Omar A, Sharma B, Payawal D, Abdallah A, Serwah A, Hamed A, Elsayed A, AbdelMaqsod A, Hassanein T, Ihab A, H GH, Zein N, Kumar M, Asian-Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) consensus guidelines on invasive and non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis: a 2016 update, Hepatology international 11(1) (2017) 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chin JL, Pavlides M, Moolla A, Ryan JD, Non-invasive Markers of Liver Fibrosis: Adjuncts or Alternatives to Liver Biopsy?, Frontiers in pharmacology 7 (2016) 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dyvorne HA, Jajamovich GH, Bane O, Fiel MI, Chou H, Schiano TD, Dieterich D, Babb JS, Friedman SL, Taouli B, Prospective comparison of magnetic resonance imaging to transient elastography and serum markers for liver fibrosis detection, Liver international: official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver 36(5) (2016) 659–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Parkes J, Roderick P, Harris S, Day C, Mutimer D, Collier J, Lombard M, Alexander G, Ramage J, Dusheiko G, Wheatley M, Gough C, Burt A, Rosenberg W, Enhanced liver fibrosis test can predict clinical outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease, Gut 59(9) (2010) 1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, M SS, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M, Investigators AC, Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection, Hepatology 43(6) (2006) 1317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Singh S, Venkatesh SK, Wang Z, Miller FH, Motosugi U, Low RN, Hassanein T, Asbach P, Godfrey EM, Yin M, Chen J, Keaveny AP, Bridges M, Bohte A, Murad MH, Lomas DJ, Talwalkar JA, Ehman RL, Diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance elastography in staging liver fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data, Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 13(3) (2015) 440–451 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yin M, Talwalkar JA, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Grimm RC, Rossman PJ, Fidler JL, Ehman RL, Assessment of hepatic fibrosis with magnetic resonance elastography, Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 5(10) (2007) 1207–1213 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dill T, Contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging: non-invasive imaging, Heart 94(7) (2008) 943–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fernandes FF, Ferraz ML, Andrade LE, Dellavance A, Terra C, Pereira G, Pereira JL, Campos F, Figueiredo F, Perez RM, Enhanced liver fibrosis panel as a predictor of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients, Journal of clinical gastroenterology 49(3) (2015) 235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Karlas T, Dietrich A, Peter V, Wittekind C, Lichtinghagen R, Garnov N, Linder N, Schaudinn A, Busse H, Prettin C, Keim V, Troltzsch M, Schutz T, Wiegand J, Evaluation of Transient Elastography, Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Imaging (ARFI), and Enhanced Liver Function (ELF) Score for Detection of Fibrosis in Morbidly Obese Patients, PloS one 10(11) (2015) e0141649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Friedrich-Rust M, Rosenberg W, Parkes J, Herrmann E, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C, Comparison of ELF, FibroTest and FibroScan for the non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis, BMC gastroenterology 10 (2010) 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shire NJ, Rao MB, Succop P, Buncher CR, Andersen JA, Butt AA, Chung RT, Sherman KE, Improving noninvasive methods of assessing liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus/human immunodeficiency virus co-infection, Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 7(4) (2009) 471–80, 480 e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peters MG, Bacchetti P, Boylan R, French AL, Tien PC, Plankey MW, Glesby MJ, Augenbraun M, Golub ET, Karim R, Parkes J, Rosenberg W, Enhanced liver fibrosis marker as a noninvasive predictor of mortality in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected women from a multicenter study of women with or at risk for HIV, Aids 30(5) (2016) 723–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Swanson S, Ma Y, Scherzer R, Huhn G, French AL, Plankey MW, Grunfeld C, Rosenberg WM, Peters MG, Tien PC, Association of HIV, Hepatitis C Virus, and Liver Fibrosis Severity With the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score, The Journal of infectious diseases 213(7) (2016) 1079–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ren X, Kennedy A, Colletti LM, CXC chemokine expression after stimulation with interferon-gamma in primary rat hepatocytes in culture, Shock 17(6) (2002) 513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zeremski M, Petrovic LM, Chiriboga L, Brown QB, Yee HT, Kinkhabwala M, Jacobson IM, Dimova R, Markatou M, Talal AH, Intrahepatic levels of CXCR3-associated chemokines correlate with liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C, Hepatology 48(5) (2008) 1440–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang Y, Yu W, Shen C, Wang W, Zhang L, Liu F, Sun H, Zhao Y, Che H, Zhao C, Predictive Value of Serum IFN-gamma inducible Protein-10 and IFN-gamma/IL-4 Ratio for Liver Fibrosis Progression in CHB Patients, Scientific reports 7 (2017) 40404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]