Abstract

Background

Emerging adulthood (ages 18–26) is a time of identity exploration, experimentation, focusing on self or others, and instability, themes captured in the Inventory of Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA). Preliminary evidence suggests that emerging adults (EAs) with a history of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) score differently on transition dimensions than their peers, however, the role of ACE in the IDEA - substance use relationship is unknown.

Methods

Data are from a longitudinal study of acculturation and health among Hispanics in California (N=1,065). Multivariable regression models assessed the association between IDEA and ACE (no ACE, 1–3 ACE, and ≥ 4 ACE) for substance use behaviors over two time points. Interaction terms assessed whether ACE moderated the association between subjective perceptions of IDEA at age 20 and substance use at age 24.

Results

ACE exposed EAs scored higher on identity exploration, instability, self-focus, and experimentation dimensions than their peers (ps < .01 – .001). Scores on experimentation, identity exploration, and self-focus at age 20 were associated with divergent patterns of substance use across ACE exposure categories. In comparison to other groups, individuals in ≥ 4 ACE group who strongly identified with these transition themes at age 20 had the highest probability of binge drinking, past 30-day alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use at age 24 (AORs 1.09 – 1.49, CI: 1.02–2.58).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that ACE can affect subjective perceptions of transition themes and increased risk for substance use over time. Implications for substance use prevention efforts tailored to Hispanic EAs are discussed.

Keywords: emerging adulthood, transition themes, adverse childhood experiences, substance use, Hispanics

Background

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is a developmental stage defined by individuals’ growing independence from their parents and adapting to the financial, educational, and social responsibilities of adulthood (Arnett, 2000). This period of exploration, transformation, and discovery is also marked by an increase in vulnerability to risky behaviors such as substance use. Relative to other life stages, emerging adults (EAs) (ages 18 to 26) have the highest rates of substance use and dependence (Hedden, 2015; Kong & Bergman, 2010; Mcabe, et al., 2005; SAMHSA, 2014), although patterns of substance use vary across racial and ethnic groups. For example, compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics report less frequent alcohol drinking but tend to consume higher volumes of alcohol during drinking events (Chartier & Caetano, 2010) and have higher alcohol-related negative consequences (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Galvan & Caetano, 2003; Zapolski, Pedersen, McCarthy, & Smith, 2014). Hispanics are also more likely to be tobacco users (Soneji, Sargent, & Tanski, 2016) and binge drinkers than African and Asian Americans, trends that have made Hispanics a priority population for substance use prevention efforts (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2013). Ongoing research investigating the etiology of substance use and misuse among Hispanic young adults is critical given that Hispanics are the fastest growing demographic in this age group and will represent approximately 30% of United States (US) population by 2060 (Clarke, Black, Stussman, Barnes, & Nahin, 2015; Colby & Ortman, 2014; Patten, 2016; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

In the US, establishing independence and a sense of self-determination are considered key developmental tasks of emerging adulthood that facilitate the exploration and pursuit of opportunities that help young people attain their personal, social, and professional goals (Schwartz, Cote, Arnett, 2005). The misuse of drugs and alcohol however jeopardize post-secondary training and educational achievement, romantic relationships, and the formation of social and community ties that set the stage for life course advantage and health (Johnson, Crosnoe & Elder, 2011; Masten et al., 2006; Masten & Powell, 2003). One of the most potent predictors of adolescent and adult substance use that can impede successive developmental adaption is exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) (Anda et al.,2003; 2006; Erikson, 1968; Masten et al., 2006). Nonetheless, current understanding of the effects of ACE on subjective perceptions of emerging adult transition themes in the context of Hispanic substance use is extremely limited. Although sociocultural norms, expectations of adulthood, and responses to traumatic stressors may vary across ethnic groups (Arnett, 2003; Syed & Mitchell, 2013), investigation of these relationships within a cohort of EAs from similar cultural backgrounds and who were raised in comparable community settings will provide useful information for future prevention research.

Emerging adulthood

The theory of emerging adulthood defines the increasingly protracted transition into adulthood, and the postponement of traditional adult roles, as a distinct stage of development (Arnett, 2002; 2007). Accordingly, Arnett and colleagues’ inventory of the dimensions of emerging adulthood (IDEA) operationalizes and measures six key characteristics of this period: feeling in-between, identity exploration, self-focus, new possibilities, and instability/negativity (Arnett, 2000, 2004, 2005) with one dimension, other focus, added later as a counterpoint to self-focus (Reifman, Arnett, & Colwell, 2007). Feeling in-between reflects young peoples’ perception of themselves as neither adolescents nor adults, but rather as being on their way to adulthood. Identity exploration captures emerging adults’ efforts to capitalize on their newly acquired independence from parents, the ability to explore various options in life, and forging an identity while discovering who they are and who they would like to become (Arnett, 2014; Sussman & Arnett, 2014). This new level of independence also brings the freedom from obligations and commitments to others allowing the opportunity to become more self-focused and gain the necessary skills, experience, and self-sufficiency for their future adult lives (Arnett, 2004). Conversely, for the individuals who subscribe to the more traditional roles that defined previous conceptions of adulthood (i.e. marriage, childbearing), this may be a period of other focus (Arnett, 2001; Reifman et al., 2007). This stage is also one of experimentation (possibilities), where opportunities to make dramatic changes in the direction of one’s life become available. Consequently, as the number of opportunities increases, the degree to which these changes and choices are disconcerting is assessed by how strongly an individual identifies this period as one of instability/negativity.

Emerging adult transitions and substance use

Identity exploration, negativity, and experimentation have been associated with substance use (Allem, Lisha, Soto, Baezcode-Garbanati, & Unger, 2013; Lisha, Delucchi, Ling, & Ramo, 2014; Smith, Hill, Marshall, Keaney, & Wanigaratne, 2014), although experimentation has also been linked to higher social well-being (Baggio, Nakajima, Lemieux, Iglesias, & Al’Absi, 2016) and identity exploration to life satisfaction (Negru, 2012). Such findings suggest these constructs may operate independently across outcomes and subsets of the population. For instance, a recent study found that respondents with a history of childhood trauma scored lower on experimentation and self-focus and higher on negativity/instability dimensions than those without (Davis et al., 2017). Although Davis and colleagues investigated how these differences influenced adult roles (i.e. education, marriage, childbirth), their results suggest that individual perceptions of this period in life, and progression through the emerging adult years varied according to levels of childhood adversity.

ACE and substance use

Child maltreatment and parental divorce, mental illness, incarceration, or substance use (ACE) are a set of highly correlated traumatic and negative events that when experienced prior to age 18, can trigger stress responses and changes in brain functioning and physiology that negatively affect development (American Psychological Association, 2014; Brady & Sonne, 1999; Center on the Developing Child, 2015). Such trauma-related physiological and psychological processes undermine mood and behavioral self-regulation (Anda et al., 2006), impact identity and self-perception (Bowlby, 1988; Young, 2003), and increase susceptibility to maladaptive coping behaviors such as substance use (Anda, Brown, Felitti, Dube, & Giles, 2008; Anda et al., 1999; Anda et al., 2006; Ford, 2011; Grigsby et al., 2019; McEwen, 2005, 2006; Shonkoff et al., 2012). Overwhelmingly, research has demonstrated a graded relationship (e.g. the likelihood of poorer outcomes increases as the number of ACE experienced increases) between ACE and substance use across life stages (Allem, Soto, Baezonde-Garbanati, & Unger 2015; Anda et al., 1999; Forster, Grigsby, Rogers & Benjamin, 2018) and that individuals exposed to four or more ACE are at highest risk for poor mental, behavioral, and physical health outcomes (Anda et al., 2002; Dube, Miller, Brown, & Giles, 2006; Ramiro et al., 2010). Because EA is an especially risky time for substance use and the robust evidence that ACE related deficits in emotional and cognitive processing can carry forward (Gilbert, 2009; Pollack, Cicchetti, Hornung, & Reed, 2000; Young & Widom, 2014), the interplay between ACE and the dominant developmental themes of emerging adulthood (e.g., identity exploration, independence and autonomy) (Grotevant & Cooper, 1985) are an important area of substance use prevention research.

The three aims of the present study address this gap. First, we examined the association between ACE and each of the six dimensions cross-sectionally at age 20, early in this transition period. Second, we examined if the degree of identification with these themes, adjusting for ACE, was associated with substance use at age 20 and prospectively four years later, at age 24. Lastly, we investigated whether the relationships between individual dimensions of emerging adulthood and substance use varied across levels of childhood adversity. Drawing upon prior work in this area, we hypothesized that H1) ACE-exposed participants would have higher scores on negativity/instability and lower scores on the experimentation and self-focus dimensions of emerging adulthood at age 20 and H2) that higher negativity, experimentation, and in-between scores at age 20 would be positively associated with substance use cross-sectionally and four years later, at age 24. We also investigated whether ACE moderated the associations between IDEA constructs and substance use although due to the lack of research examining these relationships we did not develop a priori hypotheses regarding the strength or direction of these relationships.

Methods

Data for this study were drawn from project RED (Reteniendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud), a longitudinal study of acculturation and health among Hispanic youth in Southern California (Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009). The sample is comprised of emerging adults who participated in the study as adolescents. The original cohort of adolescents were enrolled in one of the seven randomly selected high schools in the Los Angeles area with student bodies that were at least 75% Hispanic (as indicated by data from the California Board of Education). Of the original high school cohort, approximately 35% were lost to follow-up after high school. Those lost to follow-up after high school were more likely to be male and engaged in risky behaviors (e.g., substance use) in high school, but did not differ on age or socioeconomic status (SES) (p > .05) from the current analytic sample. A summary of the RED study and methods are available elsewhere (Unger et al., 2014).

All participants who self-identified as Hispanic in high school were contacted to participate in the survey in emerging adulthood. Research assistants sent letters to participants’ last known addresses and invited them to call a toll-free phone number or visit a website to participate in the study. Emerging adults provided verbal consent over the phone or read the consent script online, indicated consent, and participated in the survey. If participants could not be contacted, staff searched for them online using social networking sites and publicly available search engines. Of those who agreed to participate, 73% took the survey online and 27% were read survey questions over the phone by a research assistant; all respondents received a $25 gift card upon completion of the survey at every wave. The Institutional Review Board at the [blinded] approved all procedures.

Participants

Data for the current study were drawn from the first wave of data collection in emerging adulthood when respondents were on average 20 (SD = 1.10) years old and the fourth wave when respondents were on average 24 (SD = 1.12) years old. Slightly over half of the sample was female (60%) with the majority of respondents reporting they were born in the US (86%). Participants identified their heritage as Mexican (85%), El Salvadoran (10%), and Guatemalan (5%). At age 20, over half (64%) were enrolled in classes, college, or vocational programs, 16% reported they had gotten married or moved in with a partner within the last year and approximately 25% were employed full time.

Measures

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) were assessed in the first emerging adulthood wave when participants were 20 years old. Consistent with Felitti et al., (1998), the 7-item index score included childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, or verbal abuse; household incarceration; having a household member who was depressed or mentally ill; having a household member who misused alcohol or was an alcoholic, and having a member of the household who used street drugs were combined to represent household substance use; exposure to parental intimate partner violence; and parental divorce. The child maltreatment stem question asked participants, “While you were growing up, that is your first 18 years of life, how often did a parent, step-parent, or adult living in your home” physically, verbally or sexually abuse them. Response options ranged from “Never,” “Once or twice,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” to “I prefer not to answer.” Coding was consistent with the method prescribed by Anda and colleagues (1999). Other parental/adult behavior items asked participants if, before they turned 18 years old, they lived with anyone who was mentally ill, abused substances, was incarcerated, or was physically violent with their spouse/partner. Response options were “Yes,” “No,” or “I prefer not to answer.” Due to the considerable literature demonstrating that persons experiencing 4 or more ACE are especially at risk for substance use (Dube et al., 2002; 2006; Ramiro et al., 2010), final ACE scores were categorized and coded into three groups: No ACE = 0, 1–3 ACE = 1, and ACE ≥ 4 = 2.

Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA) (Reifman et al., 2007) is a 31-item measure that calculates respondent’s endorsement on six dimensions/themes that has been used with Hispanic samples (Allem, 2013; Lisha et al., 2014). Sample questions include “Is this period of your life a…” “time of many possibilities?” “time of feeling stressed?” “time of finding out who you are?” and “time of trying new things?” Likert scale response options for each item ranged from strongly disagree, coded = 1, to strongly agree, coded = 4, with higher scores indicating stronger endorsement. Of these, 7 items assessed identity exploration (α = .85), 5 items measured experimentation (α = .80), 7 items were used to calculate negativity (α = .83), 3 questions were used to calculate other-focus (α = .74), 6 for self-focus (α = .78), and 3 assessed feeling in-between (α = .65).

Past 30-day substance use was measured with six items asking participants on how many of the days in the past month they drank alcohol, binge drank, smoked cigarettes, used marijuana, or used an illicit drug. Response options were 0 days, 1–3 days, 10–19 days, 20–29 days, and all 30 days. All substance use outcomes were dichotomized and coded no past 30-day use = 0 and use = 1. Due to small cell size for individual illicit drug categories, cocaine, methamphetamine, and “other drugs” were combined to create the illicit drug variable. Response options were consistent with those for other substances and with the variable dichotomized and coded no use = 0 and use of any of the aforementioned drugs in the past 30 days coded use =1.

Covariates.

Gender was coded 0 = male, 1 = female. Age was a continuous variable calculated using date of birth and date at time of survey completion. US born versus foreign-born was assessed with one item asking the respondent whether he or she was born in the US coded = 0 or outside of the US coded = 1. We adjusted for two indicators of socioeconomic status; current (full time) employment coded as yes =1 and no =0 and educational status (currently taking classes or enrolled in college), coded as yes =1 and no =0. Marital and partner status was assessed with two items; one asking if a respondent was married within the last year and another if they had moved in with a partner in the last year. We combined items to adjust for marital/partner status coded: not married and not living with partner =0, living with partner =1, married =2.

Analyses

First, a set of six linear regression models assessed the association between ACE categories (none, 1–3, or ≥ 4) and mean scores on each of the six dimensions of emerging adulthood (adjusting for age, gender, US born, employment and educational status, and marital/partner status). Diagnostic analyses indicated that the assumptions of linear regression were met. Second, we calculated five logistic regression models to assess direct effects of IDEA for each type of past 30-day substance use cross-sectionally, when participants were approximately 20 years old, and longitudinally at age 24, adjusting for ACE and covariates (age, gender, US born, employment and educational status, and marital/partner status).

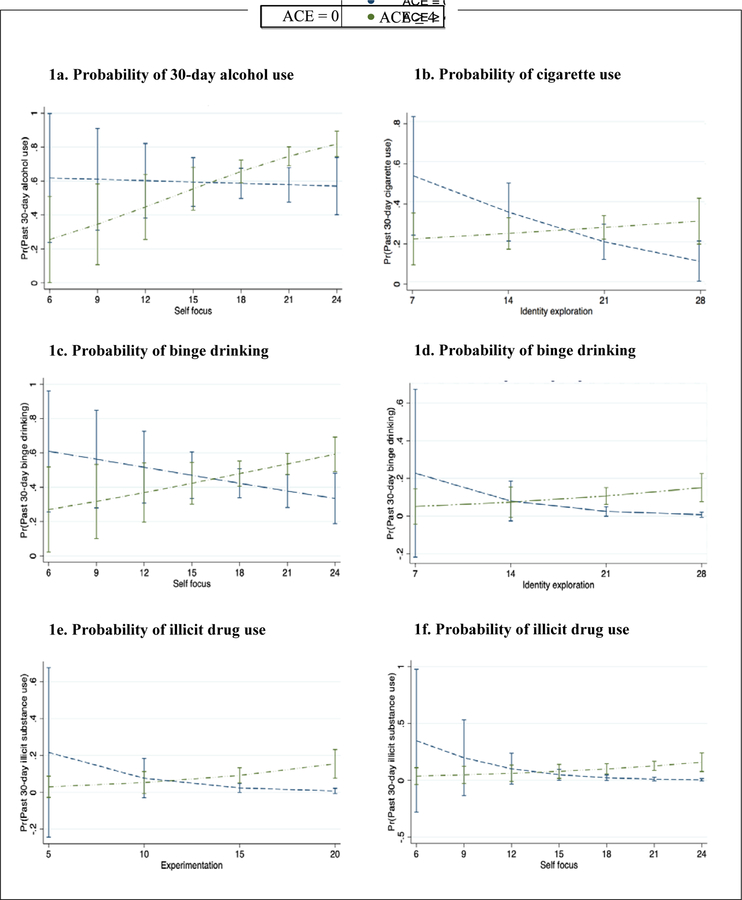

To determine whether the association between IDEA constructs and substance use behaviors varied across levels of ACE exposure (if ACE moderated the association between each dimension and substance use), interaction terms were calculated (ACE*identity, ACE*experimentation, ACE*negativity, ACE*other-focus, ACE*self-focus, ACE*in-between) and included in a final set of models. Due to significant moderation by ACE (ps < .05), results were converted from conditional log odds to probabilities with figures graphically depicting results (Figure 1a–f). Of the 1,309 respondents who participated in the survey in emerging adulthood, missing data were primarily on ACE items (17% missing, n=244). Participants who did not answer ACE questions and who did not take the survey at both time points were excluded from this study, yielding an analytic sample of N = 1,065.

Results

At age 20, approximately 70% of the sample reported using alcohol in the past 30 days, over 50% acknowledge binge drinking at least one day in the past 30 days, nearly 25% had smoked cigarettes, 60% had used marijuana, and slightly over 5% had used an illicit substance. Four years later, with the exception of cigarette and illicit drug use, there was a drop in self-reported substance use. At age 24, 18% had used alcohol on at least one day in the past 30 days, slightly less than 50% had binge drunk, 26% smoked cigarettes, 25% had used marijuana, and 8% used an illicit substance (Table 1). In regard to ACE exposure, about 18% of respondents reported no ACE, 50% had at least one, and 30% had experienced four or more (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for Project RED respondents, (N= 1,065).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 20 (1.23) |

| Frequency (%) | |

| Female | 633 (59) |

| US Born | 916 (86) |

| Marriage/partner status (age 20) | Frequency (%) |

| Married | 32 (3%) |

| Living with partner | 139 (13%) |

| Educational status (age 20) | |

| Enrolled in college or taking classes | 682 (64) |

| Full time employment status (age 20) | |

| Yes | 277 (26) |

| Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA) | Mean (SD) |

| Other-focus | 8.21 (2.18) |

| Negativity | 19.07 (4.29) |

| Identity exploration | 23.03 (3.54) |

| Feeling in-between | 9.59 (1.66) |

| Experimentation | 16.37 (2.61) |

| Substance Use (age 20) | Frequency (%) |

| Past 30-day Alcohol Use | 724 (68) |

| Past 30-day Binge Drinking | 628 (59) |

| Past 30-day Cigarette Use | 224 (21) |

| Past 30-day Marijuana Use | 639 (60) |

| Past 30-day Illicit Drug Use | 64 (6) |

| Substance Use (age 24) | Frequency (%) |

| Past 30-day Alcohol Use | 192 (18) |

| Past 30-day Binge Drinking | 511 (48) |

| Past 30-day Cigarette Use | 277 (26) |

| Past 30-day Marijuana Use | 266 (25) |

| Past 30-day Illicit Drug Use | 85 (8) |

Relationship between ACE and IDEA

We found partial support for our first set of hypotheses that there would be significant differences on mean IDEA scores for ACE exposed groups in comparison to their peers. As anticipated, participants in both the 1–3 ACE group [F (3, 1044) β = .10 p < .05)] and the ≥ 4 ACE [F (3, 1044) β = .18 p < .001] group had higher mean scores on negativity than the 0 ACE group. We expected that ACE exposed respondents would have lower average scores on experimentation and identity exploration IDEA dimensions however, the relationships were in the opposite direction. Respondents in both the 1–3 ACE [F (3, 1039) β = .12, p < .01] and ≥ 4 ACE [F(3, 1039) β = .16, p < .001] groups had higher mean scores on self-focus, and participants with ≥ 4 ACE scored higher on identity exploration [F (3, 1054) β = .12, p < .01] and experimentation [F (3, 1058) β = .09, p < .05] than participants in lower or no ACE groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regression coefficients for IDEA scores associated with ACE exposure

| Identity exploration | Negativity | Self-focus | Other-focus | Feeling in-between | Experimentation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | |

| ACE | ||||||||||||

| 1 to 3 | .047 | .273 | .104* | .012 | .123** | .002 | −.056 | .211 | .006 | .879 | .047 | .135 |

| ≥ 4 | .118** | .007 | .183*** | <.001 | .159*** | <.001 | −.021 | .639 | .062 | .142 | .089* | .040 |

Note: Each cell represents the standardized coefficient on IDEA scores associated with a category of ACE as compared to no-ACE group. All models adjusted for age, gender, US born, employment and educational status, and marital status.

= p < .05,

= p < .01,

= p < .001.

β = Standardized coefficient.

Unique effects of ACE and IDEA for substance use

Our second set of hypotheses about the relationships between IDEA dimensions and substance use outcomes were also partially supported. At age 20, four IDEA constructs were associated with some type of substance use (adjusting for ACE, age, gender, US born, educational and employment status, and marital/partner status). As expected, every unit increase in scores on negativity was associated with higher odds of past 30 day alcohol use (AOR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07–1.22) and cigarette use (AOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.10–1.29), higher experimentation scores were associated with increases in the odds of past 30-day binge drinking (AOR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.00–1.13) and alcohol use (AOR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.00–1.12), and increases in identity exploration were associated with elevated odds of illicit drug use (AOR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.00–1.07). There were also associations that we did not anticipate; higher other-focus was associated with lower odds of alcohol use (AOR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.85–0.97). At age 24, when almost all substance use behaviors had declined, higher self-focus at age 20 was associated with higher odds of marijuana use (AOR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.00–1.11).

After adjusting for IDEA, and with the exception of binge drinking behaviors at age 20, the ≥ 4 ACE group had the highest odds of using all substances relative to no ACE or 1–3 ACE groups (AOR range; 1.68, 95% CI: 1.10–2.60 to 5.08, 95% CI: 1.51–17.08), and participants with 1–3 ACE had consistently higher odds of cigarette and marijuana use than respondents who did not report experiencing ACE. At age 24 in comparison to respondents in the 0 ACE groups, the highest ACE group (≥ 4 ACE) had elevated odds of binge drinking (AORs: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.00–2.33 to 1.58, 95% CI: 1.03–2.42) and illicit drug use (AORs 5.30, 95% CI: 1.93–16.04 to 5.84, 95% CI: 2.03–16.79) and the 1–3 ACE (AORs 1.78, 95% CI: 1.10–2.86) and ≥ 4 ACE groups (AORs 2.44 – 2.56, 95% CI: 1.49–4.03) had higher odds of marijuana use (Table 3). ACE did not moderate the IDEA - substance use associations at age 20 (ps > .05).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for ACE, IDEA and past 30-day alcohol and cigarette use, binge drinking, marijuana and illicit drug use.

| Alcohol n=1053 |

Cigarettes n=1065 |

Binge Drinking n=1047 |

Marijuana n=1058 |

Illicit Drugs n=1065 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 20 | Age 24 | Age 20 | Age 24 | Age 20 | Age 24 | Age 20 | Age 24 | Age 20 | Age 24 | |

| AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

| Negativity | 1.12 (1.07–1.22)* | 0.98 (0.90–1.10) | 1.18 (1.10–1.29)* | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 1.01 (0.99–1.06) | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) |

| ACE 1–3 | 1.41 (0.94–2.11) | 1.02 (0.62–1.67) | 1.63 (1.00–2.65) | 1.14 (0.65–2.00) | 0.98 (0.59–1.63) | 1.33 (0.90–1.97) | 1.55 (1.10–2.118)* | 1.83 (1.14–2.94)* | 2.43 (0.84–7.06) | 2.61 (0.90–7.54) |

| ACE ≥ 4 | 1.69 (1.09–2.62)* | 1.10 (0.64–1.87) | 2.20 (1.41–4.01)** | 1.15 (0.64–2.11) | 1.45 (0.84–2.49) | 1.57 (1.10–2.43)** | 2.39 (1.64–3.49)*** | 2.54 (1.55–4.19)** | 3.71 (1.26–10.89)* | 5.34 (1.83–15.49)** |

| Self-focus | 1.03 (0.99–1.09) | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | 1.04 (0.99–1.11) | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 1.05 (1.00–1.13) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | 1.06 (1.00–1.11)* | 1.03 (0.94–1.14) | 1.00 (0.92–1.10) |

| ACE 1–3 | 1.44 (0.97–2.17) | 1.02 (0.63–1.68) | 1.66 (1.01–2.73)* | 1.30 (0.73–2.31) | 0.93 (0.56–1.56) | 1.36 (0.91–2.02) | 1.54 (1.10–2.17)* | 1.78 (1.1–2.86)* | 3.20 (0.96–10.72) | 2.72 (0.94–7.86) |

| ACE ≥ 4 | 1.72 (1.11–2.67)* | 1.11 (0.65–1.90) | 2.38 (1.41–4.01)** | 1.28 (0.70–2.38) | 1.42 (0.82–2.49) | 1.59 (1.03–2.43)* | 2.48 (1.69–3.64)*** | 2.46 (1.50–4.07)*** | 4.83 (1.43–16.33)* | 5.52 (1.90–16.03)** |

| Other-focus | 0.90 (0.85–0.97)** | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) | 0.97 (0.91–1.05) | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 0.99 (0.93–1.08) | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) | 1.05 (0.93–1.17) |

| ACE 1–3 | 1.47 (0.98–2.19) | 0.98 (0.60–1.60) | 1.73 (1.06–2.81)* | 1.13 (0.64–1.97) | 0.99 (0.60–1.64) | 1.26 (0.87–1.89) | 1.63 (1.17–2.29)** | 1.88 (1.17–3.02)** | 2.69 (0.93–7.76) | 2.91 (1.01–8.39)* |

| ACE ≥ 4 | 1.79 (1.17–2.77)* | 1.08 (0.64–1.84) | 2.35 (1.40–3.91)** | 1.17 (0.65–2.12) | 1.49 (1.15–2.73) | 1.47 (0.98–2.26) | 2.61 (1.80–3.78)*** | 2.59 (1.57–4.20)*** | 3.85 (1.32–11.24)* | 5.84 (2.03–16.79)** |

| Identity exploration | 1.02 (0.997–1.05) | 0.98 (0.94–1.04) | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 1.01 (0.95–1.05) | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.97 (0.88–1.94) | 1.06 (1.02–1.09)* | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 1.11 (1.02–1.21)* | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) |

| ACE 1–3 | 1.46 (0.98–2.19) | 0.99 (0.60–1.61) | 1.73 (1.05–2.84)* | 1.19 (0.68–2.11) | 0.99 (0.60–1.65) | 1.31 (0.88–1.94) | 1.65 (1.17–2.31)** | 1.81 (1.13–2.91)* | 3.31 (0.99–11.03) | 2.72 (0.94–7.85) |

| ACE ≥ 4 | 1.70 (1.11–2.63)* | 1.10 (0.65–1.87) | 2.35 (1.40–3.95)** | 1.23 (0.68–2.24) | 1.48 (0.86–2.56) | 1.59 (1.03–2.32)* | 2.54 (1.75–3.69)*** | 2.51 (1.53–4.10)*** | 4.74 (1.41–15.97)* | 5.66 (1.96–16.32)** |

| In-between | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 1.01 (0.92–1.12) | 1.06 (0.97–1.17) | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 1.06 (0.90–1.26) | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) |

| ACE 1–3 | 1.49 (1.00–2.23)* | 0.99 (0.60–1.61) | 1.68 (1.03–2.74)* | 1.15 (0.66–2.01) | 1.02 (0.62–1.70) | 1.32 (0.90–1.96) | 1.64 (1.17–2.29)** | 1.88 (1.17–3.01)** | 3.43 (1.03–11.40)* | 2.75 (0.95–7.93) |

| ACE ≥ 4 | 1.68 (1.10–2.60)* | 1.12 (0.65–1.90) | 2.25 (1.35–3.75)** | 1.17 (0.65–2.10) | 1.49 (0.64–2.09) | 1.49 (0.98–2.26) | 2.56 (1.76–3.71)*** | 2.48 (1.51–4.06)*** | 5.08 (1.51–17.08)** | 5.56 (1.93–16.04)** |

| Experimentation | 1.06 (1.00–1.12)* | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 1.07 (1.00–1.13)* | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 1.12 (0.95–1.07) | 0.97 (0.88–1.06) |

| ACE 1–3 | 1.53 (1.04–2.25)* | 0.96 (0.59–1.57) | 1.75 (1.10–2.85)* | 1.12 (0.65–1.98) | 1.02 (0.62–1.69) | 1.31 (0.89–1.93) | 1.59 (1.14–2.23)** | 1.86 (1.20–2.96)* | 2.50 (0.86–7.22) | 2.79 (0.97–8.05) |

| ACE ≥ 4 | 1.72 (1.12–2.65)* | 1.08 (0.63–1.83) | 2.35 (1.49–3.89)** | 1.11 (0.62–2.02) | 1.50 (0.87–2.57) | 1.44 (0.95–2.19) | 2.47 (1.70–3.58)*** | 2.46 (1.51–3.99)*** | 3.52 (1.20–10.32)* | 5.30 (1.83–15.33)** |

Note: Cells are adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). AORs reflect the odds of substance use for members of each ACE category as compared to the reference group (no ACE). Bolded results are significant at p < 0.05 All models adjusted for age, gender, US born, employment and educational status, and marital/partner status.

= p < .05,

= p < .01,

= p < .001.

Moderation effects

ACE categories moderated the relationship between several IDEA constructs and substance use at age 24. Participants in the ≥ 4 ACE group, who had higher scores on self-focus, identity exploration, and experimentation at age 20, were actually at greater risk for substance use at age 24 than the 0 ACE and 1–3 ACE groups (for whom IDEA scores at age 20 were not predictive of substance use). Specifically, individuals in the ≥ 4 ACE group who strongly identified with self-focus at age 20 had higher probabilities of past 30-day alcohol use, binge drinking, and illicit substance use at age 24 than their peers. Similarly, individuals in ≥ 4 ACE group with higher scores on identity exploration or experimentation at age 20, were more likely than respondents in the 0 ACE or 1–3 ACE groups to have binge drunk and used illicit substances, respectively, at age 24 (Figure 1a–f).

Figure 1.

The relationship between IDEA (age 20), ACE, and substance use outcomes at age 24

Note: 1a-1f show predicted probability of substance use behaviors at age 24 with 95% confidence intervals. All models adjust for age, gender, US born, educational and employment status, and marital status.

Discussion

Given that the accomplishments, lessons, and benefits of critical developmental transitions have long-term implications for health, satisfaction, and sustainability over the life course (Masten et al., 2004), this paper examined the relationships between emerging adult transition themes, ACE, and substance use behaviors over a four-year period. The drop in the number of respondents who reported past month substance use at age 24, compared to age 20, aligns with epidemiological data documenting that these behaviors tend to peak in early adulthood and decline as individuals mature, secure gainful employment, find stable partnerships and begin family planning (NIDA, 2014). One of our most revealing findings was the extent of ACE exposure in the sample and that one third of respondents reported ≥ 4 ACE, the category most strongly associated with poor psychological and behavioral health outcomes. Although estimates suggest that approximately 50% of US youth will experience at least one ACE (Sacks, Murphy, and Moore, 2014), national and state data mask the uneven distribution of ACE in communities across socioeconomic strata. In the context of the present study, during the early waves of data collection, two thirds of Hispanic households in Los Angeles County earned less than $50,000 (US, Census 2011) and while in high school, over half the sample had parents with less than a high school education and a large majority qualified for free lunch. Therefore, ACE exposure in this cohort is likely a reflection of the strong link between socioeconomic disadvantage and parenting practices and behaviors (Conradi et al., 2000; Drake & Jonson-Reid, 2014). Taken together, our results and the substantial literature demonstrating the effects of economic strain on health and development, contribute to the mounting evidence that policies need to prioritize efforts to reduce family adversity in communities with limited resources and supports.

One of our primary aims was to investigate whether the degree of identification with the six salient transition dimensions of emerging adulthood was related to substance use. After adjusting for ACE, our finding that identity exploration was associated with marijuana and illicit drug use at age 20, but not predictive of these behaviors four years later, aligns with contemporary identity and development scholarship. Theoretically, defining one’s own values and sense of self, although a central task of emerging adulthood, can initially be stressful and confusing (Arnett, 2000; Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004; Schwartz et al., 2013). However, as the process evolves, identities are consolidated, and young people adapt to their roles and responsibilities, the stress and confusion surrounding these tasks wanes (Schwartz et al., 2013). Stronger identification with the experimentation theme at age 20 was also related to alcohol and cigarette use at age 20 but not at age 24 and suggests a sense of curiosity about risky behaviors may be normative but over the emerging adult years as individuals mature, they abandon behaviors that could jeopardize their health and overall functioning (Arnett, 2007; Walton & Roberts, 2004). Similarly, perceptions of the transition to adulthood as a period of negativity was associated with alcohol and cigarette use at age 20 but not at age 24. As in the aforementioned relationships, using substances may be a means of curbing the uncomfortable feelings that can occur when young people struggle to meet the demands of an unknown future (Allem et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2014). As they adapt, these new obligations and concerns may become less disconcerting and an expected and even potentially stimulating component of adulthood. Interestingly, at age 20, when substance use was at its highest, other-focus was associated with lower odds of alcohol use which is consistent with studies demonstrating the behavioral health benefits of prioritizing respect and caring for others, especially among Hispanic young adults (Allem et al., 2013; Arnett & Tanner, 2006; Unger et al., 2002; Zhang, Norvilitis, & Ingersoll, 2007).

Most notably, participants with high levels of ACE exposure had stronger perceptions of this period in their life as a time of self-focus, identity exploration, negativity, and experimentation. With the exception of negativity (associated with substance use only at age 20), high identification with the aforementioned themes at age 20 was associated with divergent substance use patterns across ACE exposure groups at age 24. Focusing on oneself, giving one’s values and identity serious consideration, and experimenting with new possibilities may be among the most relevant aspects of developing a positive self-concept that are fundamental to this stage of development (Cook et al., 2017). However, the increase in substance use in the high ACE group compared to the no or low ACE group among respondents who identified with these themes (e.g., experimentation, self-focus, and identity exploration) suggests that for individuals with high levels of adversity, rather than contributing to the capacity to form a coherent sense of self and purpose (Marcia, 2002; Schwartz et al., 2009), these transition themes may be perceived as destabilizing and overwhelming. Although our findings are preliminary, it stands to reason that the effects of ACE on earlier emotional and social development (Cicchetti, 2012; Gaensbauer, 1982; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010) carry forward and influence the subjective experience of transition themes that, in turn, increase vulnerability for substance use for this segment of the EA population.

In view of the mounting evidence that traumatic stressors, especially co-occurring stressors, can have serious development consequences (Gershon, Sudheimer, Tirouvanziam, Williams, & O’Hara, R., 2013; Neigh, Gillespie, & Nemeroff, 2009), increasing access to trauma-informed services during transition periods when resilient functioning can emerge (Cicchetti & Blender, 2006; Masten et al., 2004; Rutter, 1987; Widom, Dumont & Czaja, 2006) is a critical next step. Some of the key ingredients of resilience are having supportive relationships with peers and adults in the community (Collishaw et al., 2007; Forster, Gower, Borowsky & McMorris 2017), having a positive perception of one’s ethnic heritage, and having a shared sense of belonging and membership in a group (Jackson & Lassiter, 2001; Quintana, 2007; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2015; Schwartz, Côté, & Arnett, 2005; Smith & Silva, 2011; Ungar, 2011). In fact, the advantages of a positive perception of one’s ethnic heritage and identity for health and well-being (Burnett-Zeigler, Bohnert, & Ilgen, 2013; Forster, Grigsby, Soto, Sussman, & Unger, 2017, 2019; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, & Wang, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007) highlight the potential for culturally informed trauma based programs to yield substantial benefits for at-risk, Hispanic emerging adults as they establish independent lives.

Limitations

Our results should be considered in light of the following limitations. First, the generalizability of our findings is limited to emerging adults of predominantly Mexican descent living in urban settings similar to Southern California. Second, although we adjust for employment, education, and marital/partner status, items on the survey only asked about past-year marriages and living arrangements, full time employment and enrollment in classes or in college. As such, we cannot adjust for part-time employment, type of educational institution, income, or prior partnerships. Third, the IDEA measure may not encompass all emerging adult transitions although research has begun to use this measure to assess the role of these constructs in early adult behavioral and emotional health. Fourth, we cannot definitively anchor ACE to a specific time point in childhood although survey items explicitly ask about events that occurred prior to age 18. Therefore, we could not assess whether the timing and frequency of ACE was differentially associated with respondent’s perceptions of transition themes or substance use. Fifth, the participants lost to attrition may represent an especially vulnerable subset of the sample such that our results provide only a preliminary understanding of these relationships. It is also possible that respondents who were lost to follow up assumed adult roles (parenthood, financial responsibility for the family) early and were not able to participate in later waves that, had they been included, would have provided a more complete picture of the IDEA – substance use relationships. Sixth, although there is a substantial literature on gender differences in developmental timing and exposure to specific types of ACE, after adjusting for ACE, there were no gender differences in IDEA scores. Our models were not sufficiently powered to examine gender differences in the associations between IDEA, ACE and substance use yet future work should explore these relationships as this may have important implications for prevention and intervention program design. Lastly, although the dimensions of IDEA had good internal consistency, further study of the psychometric properties of IDEA across populations is warranted (Allem, Sussman & Unger, 2017; Lisha et al., 2014). Despite these limitations, this is one of the few studies to explore the associations between IDEA, ACE, and substance use over two time points in a nonclinical, community sample of Hispanic EAs.

Conclusion

Studies with diverse emerging adults suggest that young people across ethnic groups value and are engaged in an effortful pursuit of personal agency and that this endeavor is positively associated with adaptive development (Marcia, 2002; Schwartz, Cote, Arnett, 2005). That ACE exposed EAs experience this transition differently than their peers is not surprising and underscores the need to invest in programs that facilitate post traumatic growth for at risk young people as they transition to adulthood. However, to develop effective programs for ACE exposed Hispanic youth, it is critical that research continue to investigate the synergistic relationship between ethnicity, economic disparity, and ACE in development and health.

Short statement.

The misuse of drugs and alcohol during the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood can jeopardize post-secondary training, educational achievement, and the formation of social and community ties that set the stage for life course advantage and health. Although exposure to adverse childhood experiences is one of the most potent predictors of substance use, research assessing the effects of early adversity on the subjective experience of this transition in the context of Hispanic young adult substance use is extremely limited. The present study suggests that economically vulnerable communities may be especially vulnerable to family-based adversity and that the differences in the transition experience of young adults who report high levels of adversity versus those with no or low levels of adversity increases risk for alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use. Our results, in conjunction with the substantial literature demonstrating the harmful effects of traumatic stressors and economic strain on health and development, highlights the need for investment in programs that facilitate post traumatic growth for at-risk young people as they transition to adulthood.

Funding:

NIDA Grant# DA016310

References

- Allem J-P, Lisha NE, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, & Unger JB (2013). Emerging adulthood themes, role transitions and substance use among Hispanics in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors, 38(12), 2797–2800. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem J-P, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L, & Unger J (2015). The relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use among Hispanic emerging adults. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 47(1), 60–64. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.1001099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Sussman S, & Unger JB (2017). The Revised Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA-R) and substance use among college students. Evaluation & the health professions, 40(4), 401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, & Giles WH (2008). Adverse childhood experiences and prescription drug use in a cohort study of adult HMO patients. BMC public health, 8(1), 198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Giles WH, Williamson DF, & Giovino GA (1999). Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. Jama, 282(17), 1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.171652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, … Giles WH (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, & Williamson DF (2002). Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric services, 53(8), 1001–1009. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American psychologist, 55(5), 469. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2001). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of adult development, 8(2), 133–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1026450103225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2002). The psychology of globalization. American psychologist, 57(10), 774. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.10.774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New directions for child and adolescent development, 2003(100), 63–76. doi: 10.1002/cd.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2005). The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 235–254. doi:http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002204260503500202 [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child development perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (Vol. 14). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, & Tanner JL (2006). Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio S, Nakajima M, Lemieux A, Iglesias K, & al’Absi M (2016). Associations of emotional states and stress with hungeramong smokers and non-smokers Paper presented at the Psychosomatic Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1988). A Secure Base. Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Zeigler I, Bohnert KM, & Ilgen MA (2013). Ethnic identity, acculturation and the prevalence of lifetime psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults in the US. Journal of psychiatric research, 47(1), 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(1–2), 152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Blender JA (2006). A multiple levels of analysis perspective on resilience: implications for the developing brain, neural plasticity, and preventive interventions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 248–258. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, & Thibodeau EL (2012). The effects of child maltreatment on early signs of antisocial behavior: Genetic moderation by tryptophan hydroxylase, serotonin transporter, and monoamine oxidase A genes. Development and psychopathology, 24(3), 907–928. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000442\ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, & Nahin RL (2015). Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National health statistics reports(79), 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, & Ortman JM (2015). Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Population Estimates and Projections. Current Population Reports. P25–1143. US Census Bureau. Retrieved 12/19/2018, from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, & Maughan B (2007). Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: evidence from a community sample. Child abuse & neglect, 31(3), 211–229. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad D, & Perry B (2000). The cost of caring: Understand and preventing secondary traumatic stress when working with traumatized and maltreated children. Interdisciplinary Education Series. [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, … Liautaud J (2017). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric annals, 35(5), 390–398. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JP, Dumas TM, & Roberts BW (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and development in emerging adulthood. Emerging adulthood, 6(4), 223–234. doi: 10.1177/2167696817725608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, & Jonson-Reid M (2014). Poverty and child maltreatment In Korbin KR J. (Ed.), Handbook of child maltreatment (pp. 131–148). Dordecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, & Williamson DF (2002). Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: implications for health and social services. Violence and victims, 17(1), 3. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dong M, & Anda RF (2006). Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(4), 444.e441–444.e410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Anda RF, Edwards VJ, Perry GS, Zhao G, Li C, & Croft JB (2011). Adverse childhood experiences and smoking status in five states. Preventive medicine, 53(3), 188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Gower AL, Borowsky IW, & McMorris BJ (2017). Associations between adverse childhood experiences, student-teacher relationships, and non-medical use of prescription medications among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 68, 30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Grigsby TJ, Rogers CJ, & Benjamin SM (2018). The relationship between family-based adverse childhood experiences and substance use behaviors among a diverse sample of college students. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Grigsby TJ, Soto DW, Sussman SY, & Unger JB (2017). Perceived discrimination, cultural identity development, and intimate partner violence among a sample of Hispanic young adults. Cultural diversity and ethnic minority psychology, 23(4), 576. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Davis L, Grigsby T, Rogers CJ., Vetrone S, Unger JB (2019). The role of familial incarceration and ethnic identity in suicidal ideation and suicide attempt: Findings from a longitudinal study of Latinx young adults in California. American Journal of Community Psychology, in presss. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaensbauer TJ (1982). The differentiation of discrete affects: A case report. The Psychoanalytic study of the child, 37(1), 29–66. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1982.11823357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, & Caetano R (2003). Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health, 27(1), 87–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon A, Sudheimer K, Tirouvanziam R, Williams LM, & O’Hara R (2013). The long-term impact of early adversity on late-life psychiatric disorders. Current psychiatry reports, 15(4), 352. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0352-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, & Janson S (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373(9657), 68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby TJ, Forster M, Davis L, & Unger JB (2019). Substance Use Outcomes for Hispanic Emerging Adults Exposed to Incarceration of a Household Member during Childhood. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2018.1511494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, & Cooper CR (1985). Patterns of interaction in family relationships and the development of identity exploration in adolescence. Child Development, 56(2), 415–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden SL (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved 06/01/2018, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PB, & Lassiter SP (2001). Self-Esteem and Race In Goodman N, Stryker S, & Owens TJ (Eds.), Extending Self-Esteem Theory and Research: Sociological and Psychological Currents (pp. 223–254). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Crosnoe R, & Elder GH (2011). Insights on adolescence from a life course perspective. Journal of Research on adolescence, 21(1), 273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00728.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, & Cicchetti D (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 51(6), 706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, & Bergman A (2010). A motivational model of alcohol misuse in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 35(10), 855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisha NE, Grana R, Sun P, Rohrbach L, Spruijt-Metz D, Reifman A, & Sussman S (2014). Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Revised Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA-R) in a sample of continuation high school students. Evaluation & the health professions, 37(2), 156–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE (2002). Identity and psychosocial development in adulthood. Identity: An international journal of theory and research, 2(1), 7–28. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0201_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, & Coatsworth JD (2006). Competence and psychopathology in development Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation, Vol. 3, 2nd ed. (pp. 696–738). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, Roisman GI, Obradović J, Long JD, & Tellegen A (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404040143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Powell JL (2003). A resilience framework for research, policy, and practice Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities (pp. 1–26): Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’malley PM, Bachman JG, & Kloska DD (2005). Selection and socialization effects of fraternities and sororities on US college student substance use: a multi cohort national longitudinal study. Addiction, 100(4), 512–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2005). Glucocorticoids, depression, and mood disorders: structural remodeling in the brain. Metabolism, 54(5), 20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2006). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 8(4), 367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2015). Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/The-Science-of-Resilience.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Negru O (2012). The time of your life: Emerging adulthood characteristics in a sample of Romanian high-school and university students. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 16(3), 357. [Google Scholar]

- Neigh GN, Gillespie CF, & Nemeroff CB (2009). The neurobiological toll of child abuse and neglect. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(4), 389–410. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA, National Institute on Drug Abuse,. (2015). Nationwide Trends. Retrieved 02/23/2018, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends

- Patten E (2016). The nation’s Latino population is defined by its youth. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; Retrieved 03/01/2019, from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-is-defined-by-its-youth/ [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Cicchetti D, Hornung K, & Reed A (2000). Recognizing emotion in faces: developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Developmental psychology, 36(5), 679. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.5.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (2007). Racial and ethnic identity: Developmental perspectives and research. Journal of counseling psychology, 54(3), 259. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro LS, Madrid BJ, & Brown DW (2010). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child abuse & neglect, 34(11), 842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Arnett JJ, & Colwell MJ (2007). Emerging adulthood: Theory, assessment and application. Journal of Youth Development, 2(1), 37–48. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2007.359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, & Tellegen A (2004). Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development, 75(1), 123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American journal of orthopsychiatry, 57(3), 316–331. doi:http://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1111%2Fj.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks V, Murphy D, & Moore K (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: National and State-level prevalence (Research brief# 2014–28). Retrieved 03/01/2018, from http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Brief-adverse-childhoodexperiences_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AH, Eichstaedt JC, Kern ML, Dziurzynski L, Ramones SM, Agrawal M, … Seligman ME (2013). Personality, gender, and age in the language of social media: The open-vocabulary approach. PloS one, 8(9), e73791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Côté JE, & Arnett JJ (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37(2), 201–229. doi:http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0044118×05275965 [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Weisskirch RS, & Wang SC (2009). The relationships of personal and cultural identity to adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning in emerging adults. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150(1), 1–33. doi: https://doi.org10.1080/00224540903366784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J, & Garner A (2012). Committee on early childhood, adoption and dependent care. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, Hill R, Marshall J, Keaney F, & Wanigaratne S (2014). Sleep related beliefs and their association with alcohol relapse following residential alcohol detoxification treatment. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy, 42(5), 593–604. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, & Silva L (2011). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of counseling psychology, 58(1), 42. doi: 10.1037/a0021528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneji S, Sargent J, & Tanski S (2016). Multiple tobacco product use among US adolescents and young adults. Tobacco control, 25(2), 174–180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- <Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No.(SMA) 14–4863. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, & Arnett JJ (2014). Emerging adulthood: developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Evaluation & the health professions, 37(2), 147–155. doi:http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0163278714521812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Mitchell LL (2013). Race, ethnicity, and emerging adulthood: Retrospect and prospects. Emerging adulthood, 1(2), 83–95. doi: 10.1177/2167696813480503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. (2011, 2018-01-18T13:41:36.068-05:00). The Hispanic Population: 2010. Retrieved 05/20/2018, from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-04.html [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Updegraff KA (2007). Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of adolescence, 30(4), 549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M (2011). The social ecology of resilience. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Teran L, Huang T, Hoffman BR, & Palmer P (2002). Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of California adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory, 10(3), 257–279. doi: 10.1080/16066350211869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner KD, Soto DW, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2009). Parent–child acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. The journal of primary prevention, 30(3–4), 293–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Schwartz SJ, Huh J, Soto DW, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2014). Acculturation and perceived discrimination: Predictors of substance use trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood among Hispanics. Addictive behaviors, 39(9), 1293–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton KE, & Roberts BW (2004). On the relationship between substance use and personality traits: Abstainers are not maladjusted. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(6), 515–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2004.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, & Czaja SJ (2007). A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(1), 49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JC, & Widom CS (2014). Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion processing in adulthood. Child abuse & neglect, 38(8), 1369–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JE, Klosko JS, & Weishaar ME (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, & Smith GT (2014). Less drinking, yet more problems: understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological bulletin, 140(1), 188. doi: 10.1037/a0032113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Norvilitis JM, & Ingersoll TS (2007). Idiocentrism, allocentrism, psychological well being and suicidal ideation: A cross cultural study. OMEGA-Journal of death and dying, 55(2), 131–144. doi: 10.2190/OM.55.2.c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]