Abstract

An unbalanced pigment distribution among the sepal and petal segments results in various colour patterns of orchid flowers. Here, we explored this type of mechanism of colour pattern formation in flowers of the Cattleya hybrid ‘KOVA’. Our study showed that pigment accumulation displayed obvious spatiotemporal specificity in the flowers and was likely regulated by three R2R3-MYB transcription factors. Before flowering, RcPAP1 was specifically expressed in the epichile to activate the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, which caused substantial cyanin accumulation and resulted in a purple-red colour. After flowering, the expression of RcPAP2 resulted in a low level of cyanin accumulation in the perianths and a pale pink colour, whereas RcPCP1 was expressed only in the hypochile, where it promoted α-carotene and lutein accumulation and resulted in a yellow colour. Additionally, we propose that the spatiotemporal expression of different combinations of AP3- and AGL6-like genes might participate in KOVA flower colour pattern formation.

Subject terms: Gene regulation, Gene expression, Plant breeding

Li et al. provide insights on the color patterning process during flower development. They identify pigment components of the perianths and the lip segments in the Orchidaceae flowers and use transcriptome profiling and functional assays to identify genes involved in pigment biosynthesis and spatiotemporal specificity.

Introduction

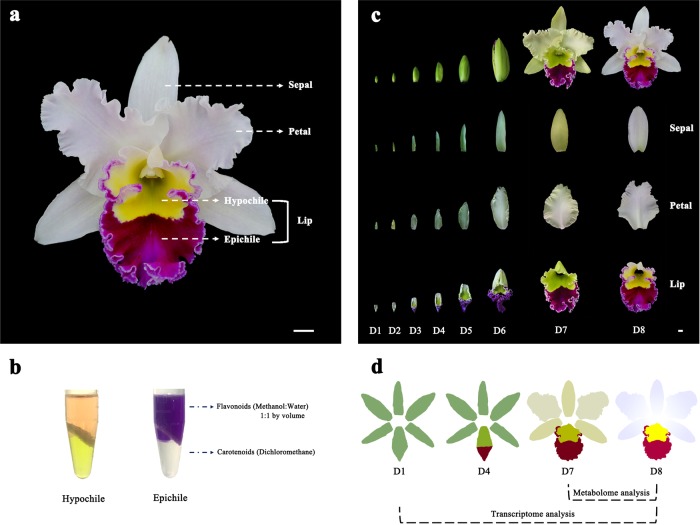

Flower colour patterns are generally shaped by colour differentiation in the petal segments and can help plants attract pollinators1,2, in addition to being an important ornamental trait3. Therefore, the exploration of the mechanism of colour differentiation is valuable for understanding plant evolution and breeding novel ornamental lines. For most species, the sepals are just uniformly green and do not contribute to interesting colour patterns. Orchids are exceptional in that the sepals and the lip are usually as colourful as the petals, which results in an unbalanced pigment distribution among different segments of the perianths and lip to show various flower colour patterns. Although numerous studies have reported the mechanisms of pigment biosynthesis in flowers4–7, the formation of colour patterns by different types of pigments among the sepal and petal segments has yet to be systematically described. Rhyncholaeliocattleya Beauty Girl ‘KOVA’ (KOVA) is a well-known ornamental orchid cultivar; its flowers are relatively large and exhibit pale pink perianths (sepal/petal), a purple-red epichile and a yellow hypochile (Fig. 1a). The red and yellow colours are determined by anthocyanins and carotenoids, respectively (Fig. 1b). These characteristics make KOVA a suitable target for addressing the interesting and important question of the mechanism of colour pattern formation.

Fig. 1. Characteristics of Rhyncholaeliocattleya Beauty Girl ‘KOVA’ (KOVA) flowers.

a KOVA flower with pale pink perianths, a purple-red epichile, and a yellow hypochile in the full-bloom stage. b The epichile is pigmented by anthocyanins, and carotenoids are the main contributor to the yellow colour in the hypochile. c Morphological anatomy of KOVA flowers during floral development. Development stage 1 (D1, bub length < 2 cm), D2 (bub length 2–3 cm), D3 (bub length 3–4 cm), D4 (bub length 4–5 cm), D5 (bub length 5–6 cm), D6 (bub length > 6 cm), D7 (2 days after flowering), and D8 (ten days after flowering). d Sampling strategy: sepals, petals, epichiles, and hypochiles were collected at D1, D4, D7 and D8, respectively, for transcriptome sequencing and metabolome identification. Bar = 1 cm.

Anthocyanins and carotenoids are widely distributed pigments in flowers. The anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway (ABP) is highly conserved and has been well studied in plants6. As crucial ABP regulators, the R2R3-MYB transcription factors can regulate the expression of structural genes to influence flower colour formation8–13. In Orchidaceae, some R2R3-MYBs have been verified to activate ABP structural genes to promote anthocyanin accumulation in Phalaenopsis5, Oncidium14 and Dendrobium15 flowers. Carotenoids are another important type of pigment that contributes to colouration ranging from yellow to red in plant tissues16,17. However, the R2R3-MYBs involved in the regulation of the floral carotenoid biosynthesis pathway (CBP) are not well known. Recently, RCP1 (R2R3-MYB) was suggested to activate CBP structural genes and increase carotenoid accumulation in Mimulus lewisii flowers18.

The shapes and colour patterns of flowers are used as visual standards of flower organ identity. According to the ABCDE model, different combinations of MADS-box genes determine flower organ identity19. B-class genes, including APETALA3 (AP3) and PISTILLATA (PI), and E-class SEPALLATA (SEP)-like genes are considered to participate in petal formation20–22. Many studies have shown that the overexpression or silencing of B-/E-class MADS-box genes can change the shape of petals20–23. Notably, as the transcription levels of these MADS-box genes change, petal colours are also altered23–30. Previous studies have indicated that combinatorial protein interaction networks among the members of the B-class, E-class and AGL6 clades during orchid floral development might be responsible for the evolutionary novelties of orchid flowers24,31–33. Recently, the P code was proposed, indicating that OAP3-1 and OAGL6-1 are required for perianth formation, whereas OAP3-2 and OAGL6-2 are necessary for lip development in orchids23. However, little is known about the relationship between MADS-box genes and flower colour pattern formation in orchids and other plants.

In this study, based on the identification of large-scale metabolomes, RNA-Seq sequencing, and Iso-Seq sequencing, we revealed the precise spatiotemporal characteristics of colour pattern formation during KOVA floral development. Then, we identified two R2R3-MYBs that might participate in the regulation of the ABP and one that might be involved in regulating the CBP in flowers. In addition, we propose that AP3- and AGL6-like genes might participate in colour differentiation in the perianth and lip segments based on the analysis of transcriptome data and a peloric mutant of KOVA.

Results

Morphological anatomy of KOVA flowers during development

The analysis of morphological anatomy showed that no red or yellow colouration appeared in the perianths and lip before floral development stage 2 (D2; Fig. 1c). From D2 to before D7, the colour of the perianths and hypochile changed from green to yellow green, and gradually increasing purple-red colouration appeared in the epichile. After flowering (i.e., from D7 to D8), the colour of the perianths changed from yellow green to white with pale pink; the hypochile turned yellow; and the epichile remained purple-red, but the degree of this coloration from D7 to D8 was lighter than that in previous stages. Based on the analysis of the morphological anatomy, we collected sepals, petals, epichiles, and hypochiles at D1, D4, D7 and D8, respectively, for transcriptome sequencing and metabolome identification (Fig. 1d).

Identification and quantification of pigment components

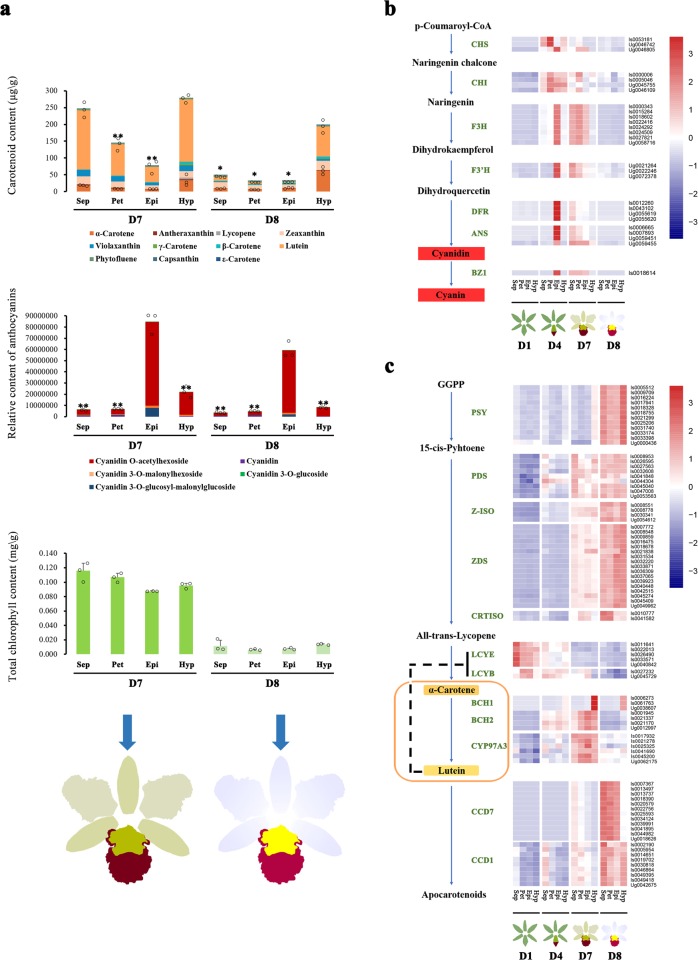

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) analysis identified eleven carotenoids and was used to quantify their levels in flowers at D7 and D8 (Figs. 1d and 2a). The total carotenoid content of the hypochile was higher than that of other flower segments at both stages (Fig. 2a). At D8, α-carotene and lutein were the main carotenoids in the hypochile, accounting for ~31 and 45% of the total carotenoid content, respectively. Moreover, cyanidin and the four forms of cyanin were detected in all flower segments (Fig. 2a). The total anthocyanin content of the epichile was highest at D7 and D8. Among the cyanins, the amount of cyanidin O-acetylhexoside was highest in all flower segments. Additionally, the total chlorophyll content of all segments at D7 was obviously higher than that at D8, and the total chlorophyll content in the perianths was higher than that in the epichile and hypochile at D7 (Fig. 2a). The total carotenoid, anthocyanin, and chlorophyll contents decreased in all flower segments from D7 to D8. These results suggested that cyanins produced via the ABP and lutein and α-carotene synthesised via the CBP contributed to the coloration of KOVA flowers ranging from purple-red to yellow, while chlorophyll provided green colouration.

Fig. 2. Identification and quantification of the pigments in KOVA flowers at D7 and D8.

a Eleven carotenoids and four cyanins were identified and quantified from the sepals, petals, and lip segments at D7 and D8 by using an LC-ESI-MS/MS system. The highest carotenoid and cyanin contents were detected in the hypochile and epichile, respectively. From D7 to D8, the total chlorophyll content was reduced in all segments. Sepal, petal, epichile, and hypochile are abbreviated as Sep, Pet, Epi, and Hyp, respectively. The data are the mean ± SD from three biological replicates. Asterisk and double asterisk indicate values that differ significantly from those in the segment with the highest pigment content in every stage at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, according to Student’s paired t-test. b The expression profile of ABP structural genes in the sepals, petals, and lip segments from D1 to D8. c The expression profile of CBP structural genes in the sepals, petals, and lip segments from D1 to D8. The data are the mean of three biological replicates. Isoform and unigene are abbreviated as Is and Ug, respectively. CHS Chalcone synthase; CHI chalcone isomerase; F3H flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3′H flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase; DFR dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; ANS anthocyanidin synthase; BZ1 flavonoid glucosyltransferase; PSY phytoene synthase; PDS phytoene desaturase; Z-ISO ζ-carotene isomerase, ZDS ζ-carotene desaturase; CRTISO carotenoid isomerase; LCYE lycopene ε-cyclase; LCYB lycopene β-cyclase; BCH β-carotene hydroxylase; CYP97A3 P450-type β-ring hydroxylase; CCD carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase.

Expression profile of structural genes in pigment biosynthesis pathways

Through PacBio Iso-Seq sequencing, 17.61 gigabytes (GB) of raw data were produced from two libraries (0–4 and 4–10 kb libraries), and 67,113 unique full-length transcripts (isoforms) were obtained through pipeline analysis. Moreover, 1.894 billion pairs of clean reads were produced from 48 libraries using RNA-Seq to calculate the expression level (fragments per kilobase per million, FPKM) of each isoform, with a mapping ratio of 77.04–85.99%. Additionally, the unmapped reads were de novo assembled, and 77,281 unigenes were produced.

The isoforms/unigenes involved in the ABP and CBP were screened from the transcriptome data-set, and heatmap analysis was used to illustrate the expression profiles of ABP and CBP structural genes in flower segments during floral development based on their FPKM values. The results showed that the expression of all ABP structural genes was barely detectable at D1, which is consistent with the absence of red colour in KOVA flowers (Fig. 2b). Thereafter, the expression of the structural genes involved in the ABP was strongly activated only in the epichile at D4, at which time the epichile displayed an obvious purple-red colour. Notably, all components of the ABP were expressed in the perianths and epichile at D7, although the expression level of ABP structural genes in those at D7 was lower than that in the epichile at D4. At the final stage, the expression of ABP structural genes was decreased in all segments, and the perianths and epichile displayed pale pink and lighter purple-red colouration, respectively (Fig. 1a). The dynamic expression of ABP structural genes in different segments during floral development is consistent with the morphological anatomy of the purple-red colouration that appears in the epichile before flowering and the pale pink colour that appears in the perianths after flowering (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, the ABP was strongly activated in the epichile and weakly activated in the perianths, which supported the metabolomic results showing that higher levels of cyanins accumulated in the epichile than in the perianths (Fig. 2a).

On the other hand, the expression of all CBP structural genes was downregulated in all segments at D1, except for the lycopene ε-cyclase (LCYE) and lycopene β-cyclase (LCYB; Fig. 2c). At D4, in addition to the LCYEs and LCYBs, β-carotene hydroxylase 1 (BCH1) was activated only in the hypochile, while BCH2s were expressed in all flower segments. At D7, the hypochile was yellower than the other segments, and the expression of the phytoene synthase (PSY) was obviously upregulated only in the hypochile. However, the upstream phytoene desaturase (PDS), carotenoid isomerase (CRTISO), BCH2 and P450-type β-ring hydroxylase (CYP97A3) were obviously upregulated in all segments, and the BCH1s were upregulated in the hypochile. Additionally, the expression of the LCYEs was downregulated in all segments, and the expression level of the LCYBs decreased only in the hypochile. In the final stage, only the hypochile displayed a yellow colour; all of the upstream CBP genes from the PSYs to the CRTISOs were upregulated; and the LCYBs and LCYEs were downregulated in all segments. Notably, the BCH1s remained highly expressed in the hypochile, whereas BCH2s and CYP97A3s were downregulated in all segments (Fig. 2c). Most CBP structural genes, especially the PSYs and BCH1s, remained upregulated only in the hypochile after flowering, which supported the results of the morphological anatomical and metabolomic analyses indicating that the carotenoid content was highest in the hypochile among the flower segments, resulting in a yellow colour (Figs. 1c and 2a).

Moreover, two types of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD), the CCD1 and CCD7, were identified from the transcriptome data. These genes began to show upregulation in D7, and their expression reached its highest level at D8 (Fig. 2c), whereas the carotenoid contents of the segments decreased from D7 to D8 (Fig. 2a). However, the CCD1s were expressed in all segments at D8, whereas the expression levels of the CCD7s remained higher only in the perianths and epichile.

Identification of R2R3-MYBs involved in the regulation of pigment biosynthesis

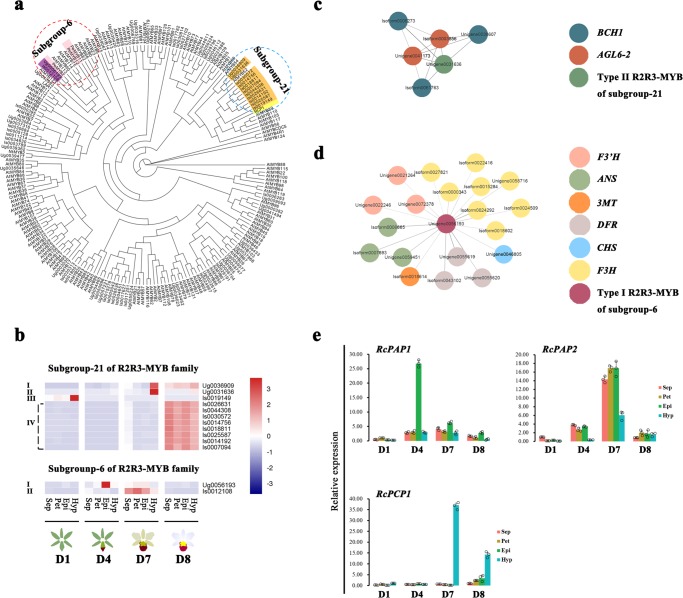

The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree suggested that eleven R2R3-MYBs from KOVA belonged to subgroup 21 of the R2R3-MYBs, which is related to RCP1, a positive regulator of the CBP (Fig. 3a; the blue circle in the figure). Additionally, two R2R3-MYBs belonged to subgroup 6, which is closely related to PeMYB2, a positive regulator of the ABP (Fig. 3a; the red circle in the figure).

Fig. 3. The identification of R2R3-MYB candidates involved in pigment biosynthesis using bioinformatics analysis.

a All amino acid sequences of KOVA R2R3-MYBs with pigment-related R2R3-MYBs and all Arabidopsis R2R3-MYBs were used to build a phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood, which was employed to infer the R2R3-MYB candidates of KOVA involved in pigment biosynthesis. The red and blue circles indicate subgroup 6 and subgroup 21 of the R2R3-MYB family, respectively. Purple and pink indicate the isoforms/unigenes of KOVA and the R2R3-MYBs of Phalaenopsis, respectively. Orange and yellow indicate the isoforms/unigenes of KOVA and the R2R3-MYBs of Mimulus lewisii, respectively. b Heatmap analysis based on the FPKM values of the R2R3-MYB candidates was performed to illustrate the expression profile of these candidates in the perianth and lip segments during flower development. The FPKM value of each candidate is the mean of three biological replicates. c The relationship between these candidates and ABP/CBP structural genes was further explored using weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA). The midnight-blue module shows that the type II R2R3MYB of subgroup 21 is coexpressed with the BCH1s and AGL6-2s during flower development. The circles represent isoforms/unigenes, and the grey lines represent connectivity among the isoforms/unigenes. d The light-yellow module shows that the type I R2R3-MYB of subgroup 6 presents a coexpression relationship with some ABP structural genes. e The expression profiles of RcPAP1, RcPAP2 and RcPCP1 during flower development were confirmed using qRT-PCR. The data are the mean ± SD from three biological replicates. Isoform and unigene are abbreviated as Is and Ug, respectively.

Based on the FPKM values of the R2R3-MYBs of KOVA that belonged to subgroup 6 and subgroup 21, the heatmap analysis showed that the R2R3-MYBs of KOVA that clustered in subgroup 21 could be characterised as four types: type I R2R3-MYBs were upregulated in the hypochile at D7 and in all segments at D8; type II R2R3-MYBs were upregulated only in the hypochile, and their expression level was highest at D7; type III R2R3-MYBs were upregulated only in the hypochile at D1; and type IV R2R3-MYBs were upregulated in all segments at D8 (Fig. 3b). Additionally, in subgroup 6, two different expression profiles of the R2R3-MYBs of KOVA were observed: type I R2R3-MYBs were upregulated only in the epichile at D4, and type II R2R3-MYBs were upregulated in the perianths and epichile at D7 (Fig. 3b). The expression profiles of the type I and II R2R3-MYBs were consistent with the expression profiles of ABP structural genes in the flower segments at D4 and D7, respectively (Fig. 2b).

To further confirm the potential functions of these R2R3-MYBs during flower development, we identified seventeen coexpressed gene modules and determined which R2R3-MYBs were coexpressed with structural genes involved in the ABP and CBP using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA; Supplementary Fig. 1). In the midnight-blue module, the type II R2R3-MYB belonging to subgroup 21 (Unigene0031636) was coexpressed with the BCH1s (Fig. 3c). Additionally, we found that the type I R2R3-MYB belonging to subgroup 6 (Unigene0056193) presented a co-expression relationship with ABP structural genes in the light-yellow module (Fig. 3d).

The results of the phylogenetic tree analysis, heatmap analysis and WGCNA suggested that the expression pattern of Unigene0031636 is positively related to the expression of CBP structural genes during flower development and that this unigene is a candidate for the activation of the expression of CBP structural genes; it was designated Rhyncholaeliocattleya promoted carotenoid pigmentation 1 (RcPCP1). In contrast, Unigene0056193 is a candidate for promoting the expression of ABP structural genes and was designated Rhyncholaeliocattleya promoted anthocyanin pigmentation 1 (RcPAP1). Although type II R2R3-MYB (Isoform0012108), belonging to subgroup 6, was not found to present a co-expression relationship with ABP structural genes according to WGCNA, its expression profile was consistent with the expression pattern of ABP structural genes at D7 (Figs. 2b and 3b). Therefore, Isoform0012108 was considered a candidate that might activate the ABP and was designated Rhyncholaeliocattleya promoted anthocyanin pigmentation 2 (RcPAP2). Finally, we confirmed the expression profiles of these candidates using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), and the results were consistent with the transcriptome data (Fig. 3b, e).

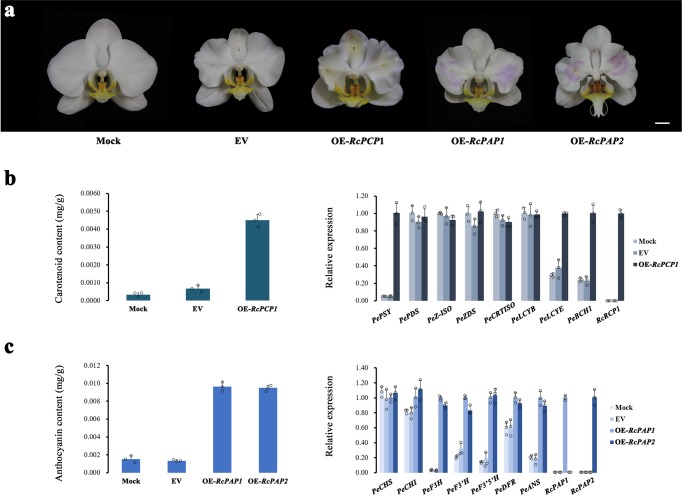

Transient overexpression of RcPCP1 and RcPAP1/2 in the perianths of a Phalaenopsis hybrid

To verify the function of the putative regulators involved in pigment biosynthesis, RcPAP1/2 and RcRCP1 were infiltrated into the perianths of a Phalaenopsis hybrid via Agrobacterium transformation. The overexpression of the empty vector (EV) did not change the colour of the perianths, which resembled the phenotype of the mock-treated flowers (Fig. 4a). The overexpression of RcPCP1 or RcPAP1/2 resulted in white perianths that became slightly yellow or purple-red, respectively (Fig. 4a). We found that the level of carotenoid accumulation was higher in the RcPCP1-overexpressing (OE-RcPCP1) lines than in the mock- and EV-treated plants and that the transcription levels of PePSY, PeLCYE and PeBCH1 were upregulated (Fig. 4b). Notably, PePSYs and BCH1s remained highly expressed in the hypochile of KOVA at D7 and D8 (Fig. 2c). As expected, the level of anthocyanin accumulation was increased in the perianths of the OE-RcPAP1/2 lines compared to the perianths of the mock- and EV-treated plants, and the ABP structural genes from PeF3H to PeANS were notably upregulated in the OE-RcPAP1/2 lines (Fig. 4c). These results indicated that RcRCP1 and RcPAP1/2 could activate CBP and ABP structural genes and promote yellow or red pigmentation in Phalaenopsis flowers, respectively.

Fig. 4. Verification of the function of RcPAP1/2 and RcPCP1 in Phalaenopsis hybrid petals via a transient overexpression assay.

a The white petals of the empty vector-overexpressing (EV) lines were similar to those of the mock-treated plants. RcPCP1-, RcPAP1-, and RcPAP2-overexpressing (OE-RcPCP1, OE-RcPAP1 and OE-RcPAP2) lines displayed slightly yellow or red petals. b The carotenoid content of the OE-RcPCP1 petals was higher than that of the mock- and EV-treated petals (left), and the qRT-PCR results showed that the expression levels of some CBP structural genes were increased in OE-RcPCP1 (right). c Anthocyanin accumulation (left) and the expression levels of some ABP structural genes (right) were obviously increased in OE-RcPAP1/2 petals. The data are the mean ± SD from three biological replicates (Supplementary Fig. 2). Bar = 1 cm.

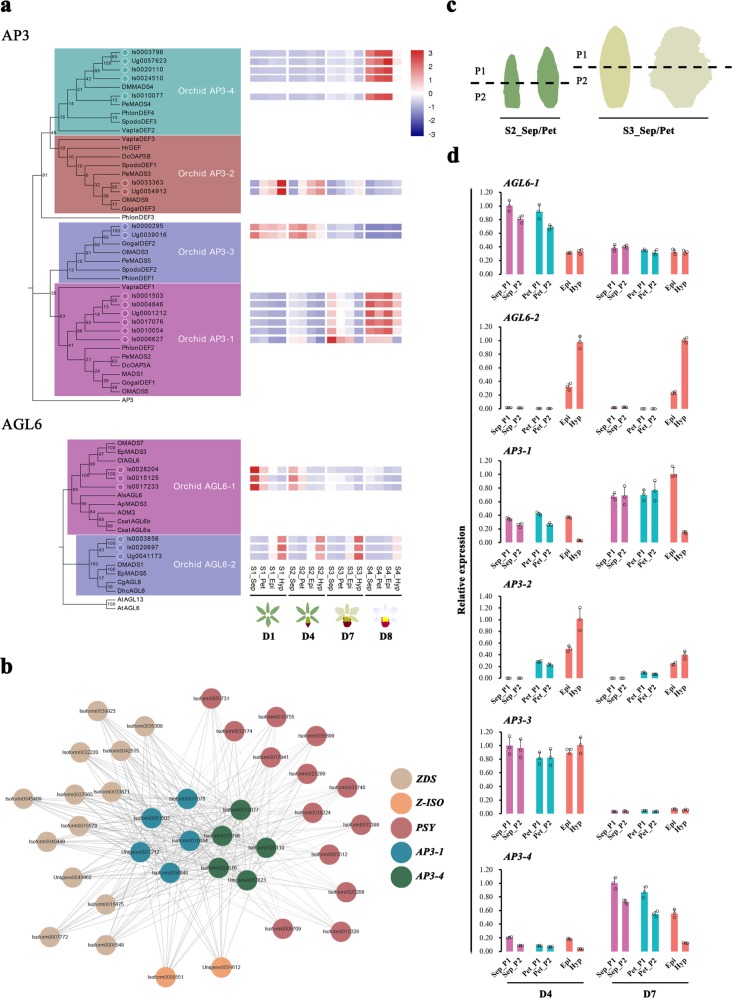

The B-class AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box genes participate in flower colour formation

The B-class AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box genes were screened from our transcriptome data, and different subgroups of AP3 and AGL6 were identified using phylogenetic trees based on the neighbour-joining (NJ) method (Fig. 5a). The heatmap of these MADS-box genes showed that their expression profiles exhibited spatiotemporal specificity during floral development (Fig. 5a). Among AP3-like genes, both the AP3-1s and AP3-4s were expressed in the perianths and lip. However, the AP3-1s were expressed at both D7 and D8, whereas the AP3-4s were highly expressed only at D8. Both the AP3-2s and AP3-3s were expressed at D1 and D4. Spatially, the expression of AP3-2s was high in the hypochiles and gradually decreased from the hypochiles to the petals, whereas the expression level of AP3-3s did not differ markedly among flower segments. Moreover, the AGL6-1s were highly expressed in the perianths at D1 and D4, and their expression level in the sepals was higher than that in the petals (Fig. 5a). Additionally, the AGL6-2s were expressed in the lip at all developmental stages, and their expression level in the hypochiles was higher than that in the epichiles. These results showed that different combinations of the AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box genes participated in determining the identity of the flower segments during KOVA flower development: AP3-1/3/4 and AGL6-1 were associated with the sepals, AP3-1/2/3/4 and AGL6-1 were associated with the petals, and AP3-1/2/3/4 and AGL6-2 were associated with the lip. Although the AP3-1/2/3/4s and AGL6-2s were expressed in both lip segments, the transcription level of the AP3-1/4s was higher in the purple-red epichile than in the yellow hypochile, whereas the transcription level of AP3-2s and AGL6-2s in the hypochile was higher than that in the epichile. Although we did not find co-expression relationships of the AP3- and AGL6-like genes with ABP structural genes according to WGCNA, the AGL6-2s were coexpressed with BCH1s and RcPCP1 (Fig. 3c), and the AP3-1/4s were coexpressed with the PSYs, ZDSs and Z-ISOs (Fig. 5b) during floral development.

Fig. 5. Spatiotemporal expression analysis of the AP3- and AGL6-like genes in the perianth and lip segments during floral development.

a Phylogenetic trees based on the neighbour-joining method were inferred from the amino acid sequences of KOVA AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box proteins and those of other plants (left). According to the FPKM values of these KOVA MADS-box genes, their expression profiles in flower segments during floral development were described via heatmap analysis (right). The FPKM value of each isoform/unigene is the mean of three biological replicates. b The brown module shows that AP3-1s and AP3-4s presented a co-expression relationship with some CBP structural genes during floral development according to WGCNA. c Sampling strategy for the sepals and petals at D4 (left) and D7 (right), which was similar to the sampling strategy for the lip. These samples were used for qRT-PCR analysis to explore the AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box gene expression profiles. d The qRT-PCR results showed that the differences in the expression levels of the AP3- and AGL6-like genes between the perianth segments were smaller than those in the lip segments. The data are the mean ± SD from three biological replicates.

To further investigate the differential expression of AP3- and AGL6-like genes between the sepal/petal segments, qRT-PCR was used to analyse the expression profiles of these MADS-box genes in the sepal/petal segments at D4 and D7 (Fig. 5c). The results showed that the differences in the expression of AP3-1/2/4 and AGL6-2 between sepal/petal segments with similar colours were smaller than those between lip segments with different colours (Figs. 1c and 5c, d). Moreover, the transcriptome data showed that the expression levels of the AP3-1/2/4s and AGL6-2s differed more between the epichile and hypochile than between the sepal and petal (Fig. 5a). These results showed that the expression levels of the AP3-1/2/4s and AGL6-2s differed more between the epichile and hypochile (the lip segments display obvious phenotypic differences) than between the sepal/petal segments (which show similar phenotypes, especially in terms of colour).

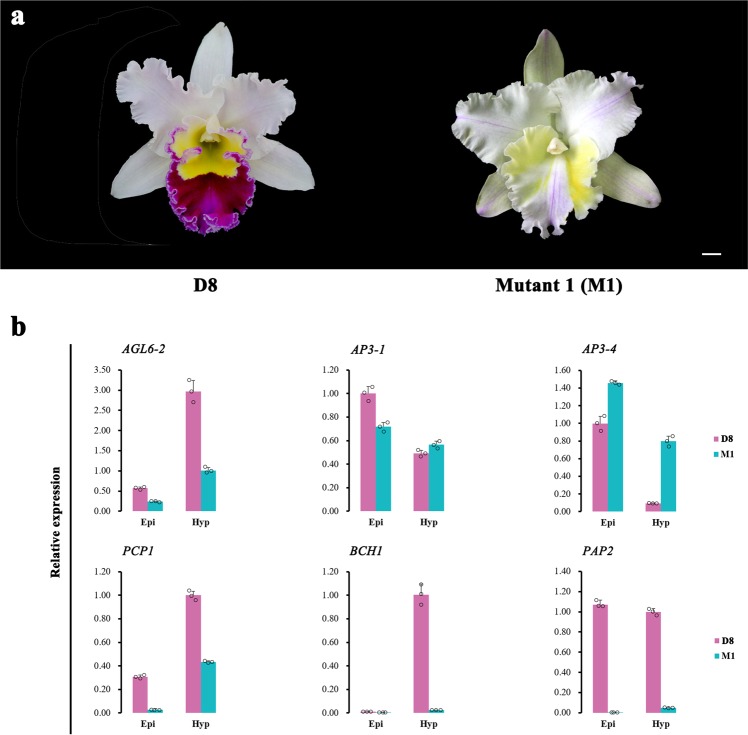

In addition, we identified a peloric mutant, designated KOVA mutant 1 (M1), in which the lip was transformed into petals (Fig. 6a). The colouration of the epichile and hypochile of M1 at D8 changed from the original yellow and purple-red colouration to very light yellow and almost white coloration, respectively (Fig. 6a). Before full flowering, we could not distinguish M1 from KOVA, and we only collected M1 samples at D8. Therefore, according to the heatmap analysis of transcript expression, we compared the expression profiles of the genes that were expressed at the late developmental stage (i.e., D7 and D8), including AP3- and AGL6-like genes and genes involved in pigment biosynthesis, between M1 and wild-type flowers at D8 using qRT-PCR. The results showed that the epichile and hypochile dispalyed a similar phenotype in M1 compared to the wild-type, the differential expression of AP3-1/4 and AGL6-2 in the lip segments was lower in M1 than that in the wild-type, and RcPCP1, BCH1 and RcPAP2 were obviously downregulated in M1 (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6. The relationship between flower colour and the expression levels of AP3- and AGL6-like genes.

a Wild-type KOVA flowers at D8 (left) and the KOVA mutant 1 (M1; right). b The expression levels of the late-expressed AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box genes and some pigment biosynthesis genes were detected using qRT-PCR. The data are the mean ± SD from three biological replicates. Bar = 1 cm.

Discussion

The expression levels of structural genes in pigment biosynthesis pathways can directly influence pigment accumulation to determine flower colour6,16,17. However, most studies have focused on either anthocyanins or carotenoids, and little is known about the detailed process of colour differentiation in the sepal and petal segments. Based on a morphological anatomical analysis performed together with large-scale metabolome analysis and transcriptome analysis, our study indicated that colour pattern formation during KOVA floral development could be divided into three phases. In phase I (i.e., D1), the ABP and CBP were inactivated, resulting in an absence of red or yellow flower segments (Figs. 1d and 2b). In phase II (i.e., from D2 to before D7), the whole ABP was strongly activated only in the epichile, which resulted in the substantial accumulation of cyanins and purple-red colouration of the epichile (Fig. 2a, b). In the final phase (i.e., from D7 to D8), the perianths and hypochile turned pale pink and yellow, respectively. In this phase, the whole ABP was activated in the sepals and petals, and cyanins accumulated. Nevertheless, the intensity of the activity of the ABP structural genes was lower in the perianths in phase III than that in the epichile in phase II, which might be the reason that the sepals and petals produce only small amounts of cyanins and appear pale pink (Fig. 2a, b). Although the increased lutein content resulted in various degrees of yellow green coloration in the sepals and petals at D7, lutein content significantly decreased at D8 and ultimately resulted in the loss of the yellow colour. According to previous studies, BCH and CYP97A3 can hydroxylate the β-ring of cyclic carotenes to produce the precursor of lutein16,34,35, and the suppression of the BCH2 by RNA interference (RNAi) in Oncidium ‘Gower Ramsey’ (GR) flowers causes a reduction in the lutein content36. Additionally, CCDs can cleave carotenoids to generate colourless apocarotenoids17, and the overexpression of OgCCD1 in GR flowers causes their yellow lip produce white spots37. Thus, from D7 to D8, the reduction in the α-carotene and lutein contents of the KOVA perianths and epichile might be caused by the downregulation of BCH2s and CYP97A3s and the upregulation of CCD1s (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the hypochile maintained the highest α-carotene and lutein contents at D8, possibly due to the sustained expression of BCH1s and reduced expression of CCD7s (Fig. 2c). A decrease in the chlorophyll content resulted in the loss of green colour and a complete shift to yellow colouration in the hypochile (Figs. 1a and 2a). Notably, the LCYEs and LCYBs were obviously downregulated in the sepals, petals, and lips at phase III (Fig. 2c). This can be explained by metabolic feedback regulation, which plays an important role in carotenoid accumulation38. A previous study showed that the expression level of LCYE might present a negative correlation with the lutein content39. Therefore, an increased lutein content might result in the downregulation of the expression of LCYEs and LCYBs in KOVA flowers. According to the above findings, our study showed that the process of colour differentiation among the floral segments was very complicated. ABP and CBP structural genes were expressed with high spatiotemporal specificity during KOVA flower development, which directly caused the unbalanced distribution of pigments, leading to colour differentiation in the perianths and lip segments.

R2R3-MYBs can regulate the spatiotemporal expression of the structural genes involved in pigment biosynthesis pathways to determine pigmentation intensity and patterning in flowers, which plays a key role in the regulation of flower colour formation4,40. In our study, the protein sequences of both RcPAP1 and RcPAP2 were found to exhibit high sequence similarity with PeMYB2 (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 3), which has been shown to promote anthocyanin accumulation in Phalaenopsis hybrid flowers5. The transient overexpression assay results showed that the overexpression of RcPAP1/2 activated some ABP structural genes, leading to the accumulation of anthocyanin in Phalaenopsis hybrid flowers, which caused the white petals to become purple-red (Fig. 4a, c) and suggested that RcPAP1/2 are likely to function as an ABP activator in KOVA flowers. Interestingly, RcPAP1 was highly expressed only in the epichile at D4, whereas the expression of RcPAP2 was upregulated in the sepals, petals, and epichile at D7 (Fig. 3b). These results indicated that RcPAP1 and RcPAP2 might determine the purple-red colour of the epichile and the pale pink colour of the perianths, respectively, in KOVA. Different regions exist in the amino acid sequences of RcPAP1 and RcPAP2 (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that they might be derived from different genes with activators that may also be different. Thus, the different activators may have caused the difference in spatiotemporal expression between RcPAP1 and RcPAP2. Additionally, it is worth noting that the activity of ABP structural genes in the epichile at D4 was obviously higher than that in the sepals and petals at D7 (Fig. 2b). However, anthocyanin accumulation and the expression level of ABP structural genes were not obviously different between the OE-RcPAP1 and OE-RcPAP2 lines (Fig. 4c). There are two possible explanations for this finding: R2R3-MYB usually forms an MBW complex with bHLH and WD40 proteins to activate ABP structural genes41, which indicates that the interacting partner of RcPAPs may be downregulated at D7; some MYBs function as repressors and form a complex with bHLH proteins and other activators41. It is possible that some repressors were upregulated at D7 to prevent effective MBW complex formation in KOVA flowers. These possibilities need to be tested in the future. In summary, RcPAP1 and RcPAP2 might spatiotemporally regulate red colour formation in KOVA flower segments during floral development. The specific expression of the former contributed to the purple-red colour of the epichile at phase II, and the latter was activated in the perianths, resulting in the pale pink coloration of the perianths at phase III. This finding indicates that differences of anthocyanin accumulation among flower segments may be regulated by different R2R3-MYBs during floral development in plants.

RCP1 belongs to subgroup 21 of the R2R3-MYB family and can activate CBP structural genes to increase the carotenoid content in Mimulus lewisii flowers18. Our study indicated that the protein sequence of RcPCP1 was homologous to that of RCP1 (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 4) and that RcPCP1 was highly expressed only in the hypochile (Fig. 3b, e). Additionally, the WGCNA results suggested that RcPCP1 presented a co-expression relationship with BCH1s during KOVA flower development. Moreover, a slightly yellow colour appeared in the OE-RcPCP1 petals (Fig. 4a). The carotenoid content and the expression levels of PePSY, PeLCYE, and PeBCH1 in the OE-RcPCP1 petals were higher than those in the mock- and EV-treated petals (Fig. 4b). Notably, the PSYs and BCH1s maintained higher expression levels in the hypochile of after KOVA flowering (Fig. 2c). These results suggested that the spatiotemporally specific expression of RcPCP1 might promote α-carotene and lutein accumulation in the hypochile, resulting in the appearance of yellow colouration in phase III. These results also implied that some R2R3-MYBs belonging to subgroup 21 of monocots might possess a similar function to RCP1 in the regulation of the CBP in flowers. The yellow parts of flowers can help some plants attract pollinators1,42, and yellow is also one of the most important colours of ornamental flowers. Therefore, RcPCP1 will be an important target for future studies on the evolution of orchid flower colouration and will be valuable for the breeding of novel ornamental lines or crops.

At present, most studies focus on the mechanism by which the MBW complex regulates flower colour formation, while MADS-box genes, which are dominant actors in the determination of flower organ identity linked to shape and colour, are often ignored. According to the P code of Orchidaceae, the SP complex comprises AP3-1 and AGL6-1 and is necessary for the development of sepals and petals, whereas AP3-2 and AGL6-2 form the determinant unit of the L complex and are exclusively required for lip formation23. Our study showed that the AP3-1/2/3/4s and AGL6-2s were involved in the development of the identity of the lip during KOVA floral development, but the expression levels of AP3-1/2/4s and AGL6-2s displayed more differences between the yellow hypochile and the purple-red epichile (Fig. 5a), which might be the reason for the obvious phenotypic difference between these two segments. However, the expressional differences in these MADS-box genes between the sepal/petal segments (they show similar phenotypes during floral development, especially regarding coloration) were smaller than the differences compared to the lip segments (Figs. 1c and 5c, d). Moreover, the AP3-1/4s and AGL6-2s exhibited a co-expression relationship with some CBP structural genes and RcPCP1 (Figs. 3c and 5b). Additionally, the obvious downregulation of RcPCP1, BCH1, and RcPAP2 might reduce the yellow and red coloration of the M1 hypochile and epichile, respectively (Fig. 6b), and the expression levels of AP3-1/4 and ALG6-2 also differed in M1 compared to the wild-type at D8. Within Orchidaceae, the suppression of the expression of OAGL6-2 in the Oncidium Lemon Heart lip using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) resulted in the lightening of yellow colouration and the development of green areas on the abaxial lip23. In addition, when the E-class MADS-box genes PeSEP2 and PeSEP3 were silenced using VIGS in Phalaenopsis OX Red Shoes, the sepals and petals showed green colouration and their tips accumulated higher levels of anthocyanins24. Therefore, the expression levels of AP3- and AGL6-like genes in different combinations might contribute to colour differentiation of the perianth and lip segments during floral development in KOVA. In addition, previous studies have shown that changes in the expression levels of MADS-box genes are accompanied by the transformation of flower petal identity, including petal shape and colour23–30,43, which suggested that MADS-box genes might have multiple functions and be involved in the shape and colour differentiation of sepals and petals; several MADS-box genes have been verified to directly or indirectly regulate CBP44,45 or ABP46 structural gene expression to influence colour in fruits, which also supports our finding that MADS-box genes might participate in KOVA flower colour formation. However, how MADS-box genes actually influence flower colour formation is still unknown, and further functional studies in plants involving thorough transgenic systems are needed to illustrate the role of MADS-box genes in this process.

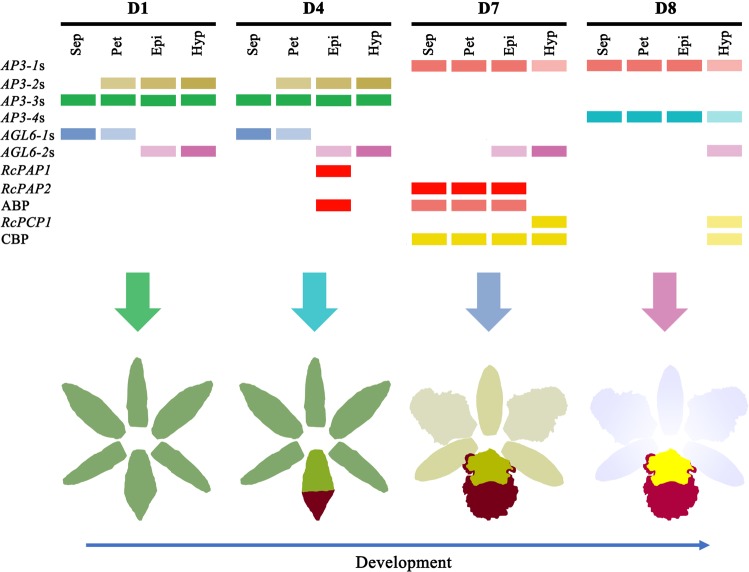

In summary, the RcPAP1/2, RcPCP1 and AP3/AGL6 MADS-box genes might collectively regulate colour differentiation in perianth and lip segments during KOVA flower development (Fig. 7), which may result in the spatiotemporal expression of ABP and CBP structural genes to determine colour differentiation, as follows: substantial cyanin accumulation in the epichile results in purple-red colouration before flowering; after flowering, the low levels of cyanin and carotenoids in the perianths result in a pale pink colour, and the extremely high α-carotene and lutein contents in the hypochile result in yellow colouration. These findings from this study can enrich our understanding of flower colour pattern formation.

Fig. 7. The mechanism of colour differentiation in the sepals, petals, and lip segments during KOVA floral development.

Different combinations of AP3- and AGL6-like MADS-box genes, R2R3-MYBs, and ABP and CBP structural genes might participate in KOVA flower colour pattern formation during floral development. The colour of each rectangle indicates whether the isoforms/unigenes was expressed, and deep colours indicate that the expression intensity of the isoforms/unigenes is high. ABP Anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway; CBP carotenoid biosynthesis pathway.

Methods

Plant materials and sampling

Rhyncholaeliocattleya Beauty Girl ‘KOVA’ (KOVA) flowers are very large and exhibit pale pink perianths, a purple-red epichile and a yellow hypochile (Fig. 1a), while KOVA mutant 1 (M1) exhibits a lip that has been transformed into petals (Fig. 6a). The hybrid Phalaenopsis flower has white perianths and a light-yellow lip with red stripes (Fig. 4a) and was used for the transient overexpression assay to identify the function of isoforms/unigenes.

All orchids used in this study were grown in a Chinese Academic Forestry greenhouse (Beijing, China) under natural light with daytime and night-time temperatures of 24–30 °C.

We collected sepals, petals, the purple-red region of epichiles and the yellow region of hypochiles from KOVA flowers at D1 (i.e., bub length < 2 cm), D4 (i.e., bub length 4–5 cm), D7 (i.e., two days after flowering), and D8 (i.e., ten days after flowering) (Fig. 1d). The same four tissues of the M1 flowers were also sampled. The areas of transient isoform/unigene overexpression in Phalaenopsis hybrid flowers were sampled. All materials were sampled, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C.

Identification of pigments

According to a previous study47, flower tissues were weighed (50 mg), ground into a powder in liquid nitrogen and resuspended in 200 µl methanol, which enabled the extraction of flavonoids and carotenoids from the tissue powder. Then, an equal volume of water and dichloromethane was added to the methanol extract, followed by thorough mixing. Finally, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min to separate flavonoids and carotenoids into the supernatant liquid (aqueous) and bottom liquid (non-aqueous).

Metabolite profiling

Flavonoids and carotenoids in the sepals, petals, epichiles, and hypochiles of KOVA flowers at D7 and D8 were identified and quantified by using an LC-ESI-MS/MS system (Fig. 1d; HPLC, UFLC SHIMADZU CBM20A system, www.shimadzu.com.cn/; MS, Applied Biosystems 4500 QTrap, www.appliedbiosystems.com.cn/). Moreover, total chlorophyll was extracted and quantified as previously described in ref. 48. At both stages, three biological replicate bundles were evaluated for each part of the flower (i.e., samples of the same segment from four individuals were mixed to form one replicate), for a total of 24 samples. The flavonoids present in the freeze-dried samples were extracted, identified, and quantified using a previously described method49.

For carotenoid extraction, the freeze-dried samples were ground into powder using a mixer mill (MM 400, Retsch, Germany) with a zirconia bead for 1.5 min at 30 Hz, and 100 mg of the powder was weighed and added to 1 ml of extraction solution 1 (hexane–acetone–ethanol (2:1:1 by volume) containing 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene). Then, the sample was vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm and 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant liquid was collected and mixed with 1 ml of the extraction solution, and the mixture was centrifuged again. The final supernatant liquid was dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. A total of 200 μl of extraction solution 2 ((ethyl nitrile-methyl alcohol)-methyl tert-butyl ether (17(3:1):3) by volume) was used to dissolve the dried residues, and the sample was subsequently vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 2 min. Finally, the extract residues were filtered through a 0.22-μm membrane filter and stored in brown bottles. Carotenoid quantification in the samples was performed according to a previously described method50. In addition, the total carotenoids and anthocyanins of the samples showing transient overexpression were extracted and quantified as previously described48,51.

Total RNA extraction and quality assessment

All freeze-dried samples were ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen and weighed (50 mg) to extract total RNA using an RNA extraction kit (Huayueyang Biotechnology Inc., Beijing, CN) following the specifications of the kit. We used an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis to detect the integrity of RNA, and the purity and concentration of the RNA were analysed by using a NanoDrop™ One/OneC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

PacBio Iso-Seq library preparation, sequencing and data analysis

PacBio Iso-Seq library preparation and sequencing were performed as previously described52 with some modifications. To obtain all full-length transcriptome sequences expressed during KOVA flower development, the total RNA of the sepals, petals, epichiles, and hypochiles from D1, D7 and D8 flowers were fully mixed in equal quantities to construct sequencing libraries. Then, cDNA was synthesised using the SMARTer™ PCR cDNA Synthesis kit. After 14 cycles of PCR amplification, the products with sizes of 1–4 kb and >4 kb size used to construct libraries using the BluePippin™ Size-Selection System (Sage Science, MA, USA). Then, large-scale PCR was performed for the two libraries to amplify full-length cDNA, which was used for SMRTbell library construction (including cDNA damage repair, terminal repair, and ligation with SMRT dumbbell-type adapters). Before sequencing, the SMRTbell template was annealed with a sequencing primer, and polymerase was linked to the primer-annealed template. The polymerase-bound templates were sequenced on the PacBio Sequel platform using P6-C4 chemistry with 10 h movies.

The unique full-length transcriptome sequences (isoforms) were obtained from the raw sequencing data using the SMRT Link v5.0.1 pipeline53 supported by Pacific Biosciences. First, the circular consensus sequence (CCS) reads were extracted from the subreads in a BAM file. Second, the CCS reads were classified into full-length non-chimeric (FLNC), non-full-length (nFL), chimeric and short (i.e., read length < 200 bp) reads depending on whether cDNA primers and poly A tails were detected. Subsequently, we used Iterative Clustering for Error Correction (ICE) to cluster the FLNC reads and generate the consensus FLNC reads, which were further polished with nFL reads using Quiver to produce high-quality consensus FLNC reads. Finally, the redundant high-quality consensus FLNC reads were removed using CD-HIT-v4.6.754 with a threshold of 0.99 identity to obtain the final isoforms.

The final isoforms were annotated by BLAST searches against the nonredundant protein (Nr) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg) at an E-value threshold of 1e−5. To eliminate isoforms that may have been derived from Cymbidium mosaic virus (CymMV), we used CymMV genomes (ref|NC_001812.1|) as a reference to identify virus-originating isoforms according to their similarity (query coverage > 90% and percent identity > 80%) and obtained the final isoform set. The coding sequences (CDSs), protein sequences, and UTR sequences of the isoforms were analysed using ANGEL55. We aligned the protein sequences of the isoforms to the Pfam database (version 26.0) by using the Pfam_Scan program56 and SMART database (version 06/08/2012) with the HMMER program for profile hidden Markov models for biosequence analysis (http://hmmer.org/) to predict the protein domains.

Illumina transcriptome (RNA-Seq) library preparation, sequencing and expression level estimation

The total RNA of the sepals, petals, epichiles, and hypochiles from D1, D4, D7, and D8 flower was extracted and used for RNA-Seq sequencing (Fig. 1d) with the aim of describing the transcriptome expression profile during KOVA flower development. In these four stages, three biological replicate bundles from each part of the flower were evaluated (i.e., samples from the same structures of 4–6 individuals were mixed to form one replicate), for a total of 48 samples. RNA-Seq library preparation was performed according to a previous study57. The final PCR products were sequenced using Illumina HiSeqTM 4000.

We used in-house Perl scripts to process the raw data to obtain the clean data. In this process, reads containing adapters, reads containing more than 10% unknown nucleotides (N) and low-quality reads containing more than 50% low-quality (Q-value ≤ 10) bases were filtered from the raw data. The rRNA reads were removed from the clean data to obtain the effective data using bowtie258. The effective data were mapped to the CymMV genome (ref|NC_001812.1|) using bowtie2, and the CymMV reads were filtered from the effective data to generate the final clean data. These final clean data were then mapped to the pseudoreference genome (i.e., the previously described final isoform set) using HISAT259. The unmapped reads were assembled de novo with Trinity60 to obtain the unigene set. The annotation, CDSs, protein sequences, UTR sequences, and protein domain predictions of the unigenes were analysed using a method consistent with the above approach. Then, we combined these unigenes with the PacBio Iso-Seq data, resulting in a final reference transcriptome for KOVA. Isoform and unigene expression levels were estimated via the FPKM method using RSEM61.

Phylogenetic analysis and co-expression network construction

The ML phylogenetic tree was constructed by using RAxML-HPC BlackBox with the default parameters at the CIPRES SCIENCE GATEWAY (http://www.phylo.org/) to analyse the phylogenetic relationships among the R2R3-MYBs of KOVA and the genes from other plants. Sequence alignments were performed with MUSCLE62. Then, NJ phylogenetic trees were constructed with bootstrap values estimated from 1000 replicate runs using MEGA763 to analyse the phylogenetic relationships among the AP3- and AGL6-like genes of KOVA and the genes from other plants. Phylogenetic trees were modified using Evolgenius (http://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/). Heatmap analysis was used to display the isoform/unigene expression profile using Omiscshare tools (http://omicshare.com/tools/). The WGCNA was performed using the WGCNA (v1.47) package in R64. The isoforms/unigenes expression values were imported into the WGCNA package to establish co-expression modules using the automatic network construction function blockwiseModules with deissuesettings, except that the power was 0.5; the TOMType was unsigned; the mergeCutHeigh was 0.8; and the minModuleSize was 50. All of the isoforms/unigenes were finally clustered into 17 modules. The networks were visualised using Cytoscape v3.3.0.

qRT-PCR analysis

cDNA was synthesised from total RNA using EasyScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The primer pairs for each isoform/unigene were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The cDNA template was fully mixed with 2X TB Green™ Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa, Japan) and used for qRT-PCR in a LightCycler 480 System (Roche, USA). The qRT-PCR protocol involved an initial denaturation step (95 °C for 30 s, ramp rate of 4.4 °C/s), followed by 45 cycles of PCR (95 °C for 5 s, ramp rate of 4.4 °C/s; 60 °C for 30 s, ramp rate of 2.2 °C/s, acquisition mode: single), melting (analysis mode: melting curve, 95 °C for 5 s, ramp rate of 4.4 °C/s; 60 °C for 1 min, ramp rate of 2.2 °C/s; 95 °C, acquisition mode: continuous, acquisitions: 5/°C), and cooling (50 °C for 30 s, ramp rate of 2.2 °C/s). From D1 to D8, the transcriptional levels of the isoforms/unigenes were calculated from three biological samples. The 18S housekeeping gene of KOVA and PeActin465 were used for normalisation. All PCR primers are listed in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 1).

Transient overexpression of the R2R3-MYBs by Agrobacterium infiltration

The CDSs of RcPCP1, RcPAP1 and RcPAP2 were cloned by using the corresponding cloning primers, which were designed based on transcriptome data (Supplementary Table 1). Overexpression vector construction and infiltration were performed using a previously described method5 with some modifications. Briefly, RcRCP1, RcPA1 and RcPA2 were ligated into pCAMBIA1304 by using T4 ligase. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 via heat activation. After incubation, the EHA105 solution containing the overexpression vectors was centrifuged, and bacterial cell pellets were then resuspended by adding liquid infection medium (Murashige and Skoog liquid medium containing 1 mM MES and 100 μM acetosyringone) to an OD600 = 1. The final suspensions were injected into the petals of the Phalaenopsis hybrid two days before flowering by using an injector. Subsequently, the infected Phalaenopsis hybrid was cultivated in a Chinese Academic Forestry greenhouse under natural light with daytime and night-time temperatures ranging from 24 to 30 °C for 6−8 days. After the emergence of a stable phenotype, the area of transient isoform/unigene overexpression in the flower was photographed, and RNA was extracted. To ensure the reliability of the results, the phenotypes assessment in the transient overexpression assay of each isoform/unigene was independently repeated at least three times.

Statistics and reproducibility

Significant test was conducted by Student’s paired t-test using Omiscshare tools (http://omicshare.com/tools/), and asterisk and double asterisk indicate values that differ significantly from those in the sample with the highest value at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. In the experiment of RNA-Seq sequencing and metabolite profiling, three biological replicate bundles from each part of the flower were evaluated (i.e., samples from the same structures of 4–6 individuals were mixed to form one replicate). For the transient overexpression assays, the phenotypes assessment in the transient overexpression assay of each isoform/unigene was independently repeated at least three times to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results. Additionally, all of the qRT-PCR experiments in our study were performed three biological replications and the transcriptional levels of the isoforms/unigenes were calculated from three biological samples.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Li-Wei Chu (Chinese Academy of Forestry) for help with experiments. This work was funded by “The import of important parents of Cattleya and targeted breeding technology of lip” (Grant No. 2014-4-15).

Author contributions

Y.W. managed the project; Y.W., Z-J.L. and B-J.L. designed experiment and coordinated the project; Y.W., Z-J.L. and B-J.L. wrote the paper; J-Y.W., W-C.T. and D.-Y.Z. reviewed the paper, B-J.L. and B-Q.Z. grew the plant material; B-J. L., B-Q. Z., L-H. Z. and X. W. collected and prepared samples; J-Y. W. assisted B.-J. L. in analysing transcriptome and metabolome data; B-J. L. participated in all the experiments; B-Q. Z., W-C. T. and H.-C. L. assisted in completing transient overexpression assay; H-J. Q. assisted in measuring total chlorophyll content of samples.

Data availability

The RNA-Seq data have been deposited in NCBI under SRA accession codes: PRJNA559603. The Iso-Seq data have been deposited in NCBI under SRA accession codes: PRJNA559608. The sequence of RcPAP1, RcPAP2 and RcPCP1 have been deposited in NCBI under GenBank accession numbers: BankIt2261106 RcPCP1 MN420461, BankIt2261154 RcPAP2 MN420462 and BankIt2261158 RcPCP1 MN420463.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhong-Jian Liu, Email: zjliu@fafu.edu.cn.

Yan Wang, Email: wangyan@caf.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42003-020-0821-8.

References

- 1.Gigord LDB, et al. Negative frequency-dependent selection maintains a dramatic flower color polymorphism in the rewardless orchid Dactylorhiza sambucina (l.) soò. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6253–6255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111162598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins R, Rausher MD. Pollinator-mediated selection on flower color allele drives reinforcement. Science. 2012;335:1090–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1215198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noman A, et al. Biotechnological advancements for improving floral attributes in ornamental plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:530. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies KM, et al. From landing lights to mimicry: the molecular regulation of flower colouration and mechanisms for pigmentation patterning. Funct. Plant Biol. 2012;39:619. doi: 10.1071/FP12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu CC, et al. Three R2R3-MYB transcription factors regulate distinct floral pigmentation patterning in Phalaenopsis orchids. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:175–191. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.254599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao D, Tao J. Recent advances on the development and regulation of flower color in ornamental plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:261. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan YW, et al. Competition between anthocyanin and flavonol biosynthesis produces spatial pattern variation of floral pigments between Mimulus species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515294113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou H, et al. Multiple R2R3-MYB transcription factors involved in the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in peach flower. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1557. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anwar M, et al. Ectopic overexpression of a Novel R2R3-MYB, NtMYB2 from Chinese Narcissus represses anthocyanin biosynthesis in tobacco. Molecules. 2018;23:781. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert NW, et al. Members of an R2R3‐MYB transcription factor family in Petunia are developmentally and environmentally regulated to control complex floral and vegetative pigmentation patterning. Plant J. 2011;65:771–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu Z, et al. A novel R2R3-MYB transcription factor contributes to petal blotch formation by regulating organ-specific expression of PsCHS in tree peony (Paeonia suffruticosa) Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;60:599–661. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley D, et al. Evolution of flower color pattern through selection on regulatory small RNAs. Science. 2017;358:925–928. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tavares H, et al. Selection and gene flow shape genomic islands that control floral guides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:11006–11011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801832115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiou CY, Yeh KW. Differential expression of MYB gene (OgMYB1) determines color patterning in floral tissue of Oncidium Gower Ramsey. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008;66:379–388. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, et al. Anthocyanin biosynthesis regulation of DhMYB2 and DhbHLH1 in Dendrobium hybrids petals. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2017;112:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nisar N, et al. Carotenoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan H, et al. Carotenoid metabolism and regulation in horticultural crops. Hortic. Res. 2015;2:15036. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2015.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagawa JM, et al. An R2R3‐MYB transcription factor regulates carotenoid pigmentation in Mimulus lewisii flowers. N. Phytol. 2016;209:1049–1057. doi: 10.1111/nph.13647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman JL, et al. The ABC model of flower development: then and now. Development. 2012;139:4095–4098. doi: 10.1242/dev.083972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelaz S, et al. B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature. 2000;405:200–203. doi: 10.1038/35012103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honma T, Goto K. Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature. 2001;409:525–529. doi: 10.1038/35054083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker A, Günter T. The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;29:464–489. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu HF, et al. Model for perianth formation in orchids. Nat. Plants. 2015;1:15064. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan ZJ, et al. Flower development of Phalaenopsis orchid involves functionally divergent SEPALLATA-like genes. N. Phytol. 2014;202:1024–1042. doi: 10.1111/nph.12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitoma M, Kanno A. Graduate the greenish flower phenotype of Habenaria radiata (Orchidaceae) is caused by a mutation in the SEPALLATA-Like MADS-Box gene HrSEP-1. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:831. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sommer H, et al. Deficiens, a homeotic gene involved in the control of flower morphogenesis in Antirrhinum majus: the protein shows homology to transcription factors. Embo J. 1990;9:605–613. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tröbner W, et al. GLOBOSA: a homeotic gene which interacts with DEFICIENS in the control of Antirrhinum floral organogenesis. Embo J. 1992;11:4693–4704. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rijpkema AS, et al. Analysis of the Petunia TM6 MADS box gene reveals functional divergence within the DEF/AP3 lineage. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1819–1832. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandenbussche M, et al. Toward the analysis of the petunia MADS box gene family by reverse and forward transposon insertion mutagenesis approaches: B, C, and D floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA-Like MADS box genes in Petunia. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2680–2693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsubara K, et al. Green corolla segments in a wild Petunia species caused by a mutation in FBP2, a SEPALLATA-like MADS box gene. Planta. 2008;228:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0744-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai WC, et al. Four DEF-like MADS box genes displayed distinct floral morphogenetic roles in Phalaenopsis orchid. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:831–844. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai WC, et al. Interactions of B-class complex proteins involved in tepal development in Phalaenopsis orchid. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:814–824. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiao YY, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of floral organs from Phalaenopsis orchid by using oligonucleotide microarray. Gene. 2013;518:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu C, et al. The regulation of carotenoid pigmentation in flowers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010;504:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colasuonno P, et al. The carotenoid biosynthetic and catabolic genes in wheat and their association with yellow pigments. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:122. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3395-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang HM, et al. Modification of flower colour by suppressing β-ring carotene hydroxylase genes in Oncidium. Plant Biol. 2016;18:220–229. doi: 10.1111/plb.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiou CY, et al. Differential expression of carotenoid-related genes determines diversified carotenoid coloration in floral tissues of Oncidium cultivars. Planta. 2010;232:937–948. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cazzonelli CI, Pogson BJ. Source to sink: regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu B, et al. Enhancing the carotenoid content of Brassica napus seeds by downregulating lycopene epsilon cyclase. Transgenic Res. 2008;17:573–585. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albert NW, et al. A conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in eudicots. Plant Cell. 2014;26:962–980. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.122069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu W, et al. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis by MYB–bHLH–WDR complexes. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owen CR, Bradshaw HD. Induced mutations affecting pollinator choice in Mimulus lewisii (Phrymaceae) Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2011;5:235–244. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aceto S, Gaudio L. The MADS and the beauty: genes involved in the development of orchid flowers. Curr. Genomics. 2011;12:342–356. doi: 10.2174/138920211796429754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu S, et al. The citrus transcription factor CsMADS6 modulates carotenoid metabolism by directly regulating carotenogenic genes. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:2657–2676. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong T, et al. A tomato MADS-Box transcription factor, SlMADS2, acts as a negative regulator of fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:1026–1036. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.224436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaakola L, et al. A SQUAMOSA MADS box gene involved in the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in bilberry fruits. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1619–1629. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan YW, et al. Bulk segregant analysis of an induced floral mutant identifies a MIXTA-Like R2R3 MYB controlling nectar guide formation in Mimulus Lewisii. Genetics. 2013;194:523–528. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.151225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang YL, et al. Change law of hyperspectral data with chlorophyll and carotenoid for rice at different developmental stages. Rice Sci. 2004;18:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang A, et al. A comparative metabolomics study of flavonoids in sweet potato with different flesh colors (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) Food Chem. 2018;260:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiong C, et al. A tomato B-box protein SlBBX20 modulates carotenoid biosynthesis by directly activating PHYTOENE SYNTHASE 1, and is targeted for 26S proteasome-mediated degradation. N. Phytol. 2019;221:279–294. doi: 10.1111/nph.15373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh MH, et al. Optimizing virus-induced gene silencing efficiency with Cymbidium mosaic virus in Phalaenopsis flower. Plant Sci. 2013;201–202:25–41. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chao Q, et al. The developmental dynamics of the Populus stem transcriptome. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:206–219. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon SP, et al. Widespread polycistronic transcripts in fungi revealed by single-molecule mRNA sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimizu K, et al. Angle: a sequencing errors resistant program for predicting protein coding regions in unfinished cDNA. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2006;4:649–664. doi: 10.1142/s0219720006002260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Finn RD, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:279–285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu H, et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of digital gene expression tag profiles during maize ear development. Genomics. 2015;106:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim D, et al. Hisat: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with improved accuracy and speed. in 3rd International IEEE Computer Society Computational Systems Bioinformatics Conference (CSB 2004), 16−19. (IEEE, Stanford, 2004).

- 63.Kumar S, et al. Mega7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinforma. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen YH, et al. Transcription analysis of peloric mutants of Phalaenopsis orchids derived from tissue culture. Cell Res. 2005;15:639–657. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-Seq data have been deposited in NCBI under SRA accession codes: PRJNA559603. The Iso-Seq data have been deposited in NCBI under SRA accession codes: PRJNA559608. The sequence of RcPAP1, RcPAP2 and RcPCP1 have been deposited in NCBI under GenBank accession numbers: BankIt2261106 RcPCP1 MN420461, BankIt2261154 RcPAP2 MN420462 and BankIt2261158 RcPCP1 MN420463.