Abstract

Background

With recommendation of surgical management in primary site, both the positive and negative lymph nodes (LNs) retrieved have been emphasized to predict prognosis in stage IV rectum cancer. Therefore, we attempt to compare the prognostic performance of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) N-stage relative to lymph node ratio (LNR), log odds of metastatic lymph nodes (LODDS), and N-score in stage IV rectal cancer.

Methods

Total 5,090 patients taken surgical resection of primary site in rectum cancer with distant metastasis were extracted from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database. Harrell’s C statistic (C-index) and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) were used to evaluate the discriminative ability of the different LN staging systems.

Results

Of the 3,243 patients without radiotherapy, 82.46% (n=2,675) had been found with lymph nodes metastasis with median number of 16 lymph nodes collected (IQR: 11–22). Modeled as categorical cutoff variables for further clinical usage, when number of LNs was between 12 and 25 (C-index: 0.5997, AIC: 1,698.015), 8th AJCC N-stage outperformed other three schemas with increasing C-index and less AIC value. Assessed as continuous values, the LODDS shown as the best schemas with greatest discriminatory power (C-index: 0.5971, AIC: 3,680.017), generally. On the other hand, in the cohorts of other 1274 patients taken radiation, the median number of lymph nodes retrieved was 13 (IQR: 9–18). LODDS still remained remarkable performance as continuous (C-index: 0.5912; AIC: 1,058.765) and categorical variables (C-index: 0.5700; AIC: 1,061.703), while N-staging outperformed with less than 25 lymph nodes retrieved (LNs <12 C-index: 0.5678, AIC: 481.94; 12< LNs <25 C-index: 0.5933, AIC: 390.395).

Conclusions

When assessed as categorical variables, N-stage performed superiorly with adequate lymph nodes examined, whether the patients have got radiotherapy prior to surgery or not. LODDS showed, when assessed as a continuous variable, good discriminative ability and goodness of fit in predicting survival for stage IV rectum cancer patients regardless of radiation therapy status.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, lymph nodes (LNs), prognostic factor, survival analysis

Introduction

There are 15–20% newly diagnosed rectal cancers exhibiting with distant metastasis (1). Chemotherapy and radiotherapy combined with other palliative treatments have been advocated as the classical standard managements for stage IV rectum cancer. Recently, more and more studies proposed that surgical operation could benefit the overall survival for rectal cancer with metastasis (2-4). Although all rectal tumors with distant metastasis are assessed as stage IV in TNM-staging, various lymph nodes (LNs) status also present different survival and is the independent prognosis factor for rectal cancer (5).

As the most wildly used staging system, the 8th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) and Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) N-stage categorized patients by the number of positive LNs (PLN): pN0 (PLN =0), pN1a (PLN =1), pN1b (3≥ PLN ≥2), pN2a (6≥ PLN ≥4), and pN2b (PLN ≥7). However, some experts questioned the accuracy of N staging system for the heterogeneity of total lymph nodes retrieved (TNLE), which could deeply influence both lymphadenectomy and detailed pathologic examination (6,7). Under this circumstance, many other lymph nodes schemes occurred. The lymph node ratio (LNR), one of the most famous ones, is defined as the ratio of metastatic LNs to TNLE. In patients treated with adjuvant therapy of Intergroup trial 0089, Berger et al. found that LNR maintained it significance for survival no matter how many LNs were retrieved (8), which was a potent supplement for TNM staging system. Also, other studies supported natural logarithms of the lymph node odds (LODDS) as efficient prognostic factor (9,10). With the involvement of 192 patients under R0 resection colorectal cancer, LODDS exhibited superior performance than LNR and AJCC/UICC N-stage after 3-step multivariate analysis (9). Recently, there were also other staging systems proposed. Considering the nonlinearly relationship between TNLE and survival, Gleisner et al. developed a model-based score for predicting survival, “N-score”, which summarized both the PLN and TNLE (11). Unfortunately, there has not been any report about the application of staging system based on lymph nodes status in stage IV rectum cancer.

Though great efforts have been made for evaluation of the independent prognostic role of diverse staging system based on the LNs status in rectal cancer, no previous studies have been conducted to compare the discriminative power among different LN staging systems and no consensus has been reached about the prognostic accuracy of the diverse schemes. Therefore, two widely accepted method, C-index and AIC were used to evaluate the prognosis performance of different LN staging/score schemes in predicting cancer specific survival (CSS) for patients with stage IV rectum cancer based on a large population from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-registered database.

Methods

Patient selection

In our study, data of the patients between 20–80-year-old with stage IV rectal cancer underwent surgical treatment between 2004 and 2014 was extracted from SEER database. Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, the SEER database involves 26% population of the USA, including both the incidence and survival data of cancer from 18 cancer registries.

Clinicopathological information, including further treatment detail, was documented. The status of LNs, disease-specific and overall survival data were also collected. Patients who met the following criteria were included: (I) patients were pathologically diagnosed as stage IV rectal cancer; (II) histological types limited to adenocarcinoma (8010; 8140; 8141; 8144; 8145; 8210; 8211; 8213; 8255; 8261; 8263; 8480; 8481); (III) patients received primary surgical resection; (IV) rectal cancer was the only malignant disease. Patients with no lymph nodes retrieved from operation, taking radiotherapy both before and after operation, incomplete TNM staging or survival data were excluded.

Statistical analyze

Clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were depicted by quantitative values and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Both univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were operated to assess and verify the associations between clinicopathological factors and CSS. Multivariate analysis included age, gender, histologic grade, tumor size, T-stage, different site of tumor, chemotherapy status and each staging system. CSS was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and distinctions of subgroups in survival were verified by the Log-rank test. In particular, Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to explore differences in survival among the cohorts established by the 8th AJCC/UICC N categories, LNR, LODDS and N-score.

N-stage was coded based on the UICC/AJCC TNM staging system (8th edition). The cutoff points of other three different staging methods spring from previous study. Depended on LNR, patients were stratified into 2 groups based on the study of Ahmed et al. of which the LNR median was 0.36 (5). LODDS was counted as log (PLN-0.5)/(TNLE-PLN-0.5). According to the assessment of LODDS (LODDS <−1.133, −1.133< LODDS ≤−1.649, LODDS >−0.649), patients are divided into 3 groups (12). Presented by Gleisner et al. (11), “N-score” is another optimal LN staging/scoring system, defined as “NMLN ≤10 – NNLN ≤10 + 0.05*(NNLN ≤10)^2 + 0.2*(10< NMLN − 10< NNLN ≤25)”. And the established cut-off variables were defined as 0–4, 4–8, 8–14 and the ones >14.

The Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and the Harrell’s concordance index (C-statistic) were used to assess the accuracy of each staging system. C-index approach to 1 indicates that the prognostic value of the model is ideal, while C-index closer to 0.5 means the model for prognosis is poor. Generally, a predictive model with a low AIC indicates a better model fit and a high c statistic represents a better discrimination ability. All tests were 2-sided and a P>0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristic of patients

Total 5,090 patients were extracted from SEER database and the clinicopathological characteristic were in the Table 1. Generally, 1,274 received radiotherapy prior to surgery while 3,243 have not.

Table 1. Distributions of different staging systems depended on the LNs status lymph node status and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with stage IV rectal cancer.

| Non-radiation | RPS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1,278 | 39.41 | 489 | 38.38 | |

| Male | 1,965 | 60.59 | 785 | 61.62 | |

| Age | |||||

| <60 | 2,152 | 66.36 | 940 | 73.78 | |

| ≥60 | 1,091 | 33.64 | 334 | 26.22 | |

| Grade | |||||

| Grade I: well differentiated | 109 | 3.36 | 55 | 4.32 | |

| Grade II: moderately differentiated | 2,227 | 68.67 | 852 | 66.88 | |

| Grade III: poorly differentiated | 721 | 22.23 | 234 | 18.37 | |

| Grade IV: undifferentiated | 89 | 2.74 | 20 | 1.57 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 2,293 | 70.71 | 1,247 | 97.88 | |

| No | 950 | 29.29 | 27 | 2.12 | |

| T stage | |||||

| T1 | 49 | 1.51 | 30 | 2.35 | |

| T2 | 120 | 3.70 | 79 | 6.20 | |

| T3 | 2,195 | 67.68 | 923 | 72.45 | |

| T4 | 879 | 27.10 | 242 | 19.00 | |

| TNLE | |||||

| TNLE <12 | 1,054 | 32.50 | 607 | 47.65 | |

| 12< TNLE <25 | 1,682 | 51.87 | 560 | 43.96 | |

| TNLE >25 | 507 | 15.63 | 107 | 8.40 | |

| N-stage | |||||

| pN0 | 568 | 17.51 | 504 | 39.56 | |

| pN1a | 411 | 12.67 | 173 | 13.58 | |

| pN1b | 630 | 19.43 | 221 | 17.35 | |

| pN2a | 631 | 19.46 | 186 | 14.60 | |

| pN2b | 1,003 | 30.93 | 190 | 14.91 | |

| LNR | |||||

| LNR <0.36 | 1,966 | 60.62 | 942 | 73.94 | |

| 0.36≤LNR | 1,277 | 39.38 | 332 | 26.06 | |

| LODDS | |||||

| LODDS ≤−2.510 | 1,488 | 45.88 | 791 | 62.09 | |

| −2.510< LODDS ≤−1.680 | 363 | 11.19 | 129 | 10.13 | |

| −1.680< LODDS ≤−0.510 | 1,392 | 42.92 | 354 | 27.79 | |

| N-score | |||||

| N-score <4 | 1,621 | 49.98 | 809 | 63.50 | |

| 4≤ N-score<8 | 678 | 20.91 | 192 | 15.07 | |

| 8≤ N-score <15 | 631 | 19.46 | 153 | 12.01 | |

| 15≤ N-score | 1,003 | 30.93 | 120 | 9.42 | |

RPS, radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts

Non-radiation cohorts

The median age of the patients involved was 55-year-old (IQR: 50–65), most of which were male (n=1,965, 60.59%). The median number of the total lymph nodes retrieved was 16 (IQR: 11–22) and the median of metastatic lymph nodes was 4 (IQR: 1–8). 82.46% (n=2,675) had at least one metastatic LN. Most patients were in T3 (n=2,195, 67.68%) while there were still some in T2 (n=120, 3.70%) or T4 (n=879, 27.10%). For adjuvant treatment, there were nearly three fourths people having chemotherapy (n=2,293; 70.71%).

The distribution of different staging schemes was not even. The LNRs of 1,966 patients (60.62%) were over 0.36. The cohorts were in unequally distribution of N-stage: N0 17.51% (n=568), N1a 12.67% (n=411), N1b 19.43% (n=630), N2a 19.46% (n=631) and N2b 30.93% (n=1,003). For LODDS, there were 1,488 (45.88%) in LODDS1, 363 (11.19%) in LODDS2 and 1392 (42.92%) in LODDS3. Also, the cohorts could be divided into 4 subgroups depend on N-score: N-score1 49.98% (n=1,621); N-score2 20.91% (n=678); N-score3 19.46% (n=631); N-score4 30.93% (n=1,003).

Radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts

Varied from the previous cohort, most patients with preoperative radiotherapy were female (n=489, 38.38%) the median age was 55-year-old (IQR: 45–65). Pathologically, the most grades of tumor were moderately differentiated (n=852, 66.88%). The median number of lymph nodes collected was 13 (IQR: 9–18), and the one of positive lymph nodes was 1 (IQR: 0–4). For T-stage, similarly to the non-radiation group, 72.45% were in T3 (n=923) while still others in T2 (n=79, 6.20%) and T4 (n=242, 19.00%).

The primary site of most patients was in rectum (n=1,100, 86.34%). Compared with patients without radiation performed, more patients have taken chemotherapy as adjuvant therapy (n=1,247, 97.88%).

In general, the distributions of various staging systems were not exactly equally allocated. More than one fourth of patients have not got positive lymph nodes in operation (n=504, 39.56%), and almost three fourths LNR was less than 0.36 (n=942, 73.94%). The N-stage distribution of patients presented nearly equality: pN1a 173 (13.58%), pN1b 221 (17.53%), pN2a 186 (14.60%) and pN2b 190 (14.91%). On the other hand, more than half patients distributed in LODDS 1 group (n=791, 62.09%) while others were either in LODDS 2 (n=129, 10.13%) or LODDS 3 (n=354, 27.79%). When it came to N-score, 809 (63.50%) were less than 4, 192 (15.07%) were between 4 and 8, 153 (12.01%) were between 8 and 15 and the rest 120 (9.42%) were over 15 (Table 2).

Table 2. Five-year survival rates on the basis of N-stage, LN ratio, LODDS and N-score classification.

| Non-radiation | RPS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| N-stage | |||||

| N0 | 568 (368) | 27.32 | 504 (235) | 47.06 | |

| N1a | 411 (268) | 25.77 | 173 (107) | 28.10 | |

| N1b | 630 (437) | 22.76 | 221 (141) | 27.10 | |

| N2a | 631 (484) | 16.50 | 186 (123) | 25.47 | |

| N2b | 1,003 (832) | 10.38 | 190 (143) | 20.08 | |

| LNR | |||||

| LNR1 | 1,966 (1,320) | 25.20 | 942 (497) | 39.30 | |

| LNR2 | 1,277 (1,070) | 9.08 | 269 (252) | 17.90 | |

| LODDS | |||||

| LODDS1 | 1,488 (958) | 27.72 | 791 (401) | 41.22 | |

| LODDS2 | 363 (275) | 17.96 | 129 (84) | 28.79 | |

| LODDS3 | 1,392 (1,160) | 9.73 | 354 (264) | 19.16 | |

| N-score | |||||

| Nscore1 | 1,621 (1,170) | 20.50 | 809 (455) | 36.2 | |

| Nscore2 | 678 (494) | 19.60 | 192 (114) | 31.35 | |

| Nscore3 | 474 (377) | 12.50 | 153 (109) | 22.80 | |

| Nscore4 | 470 (347) | 18.36 | 120 (120) | 33.70 | |

RPS radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts.

Impact of LN status on risk of death

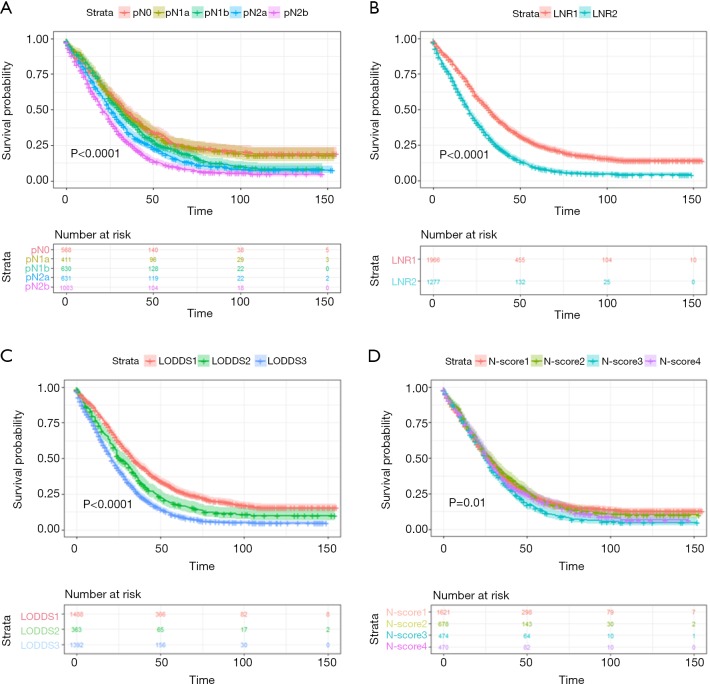

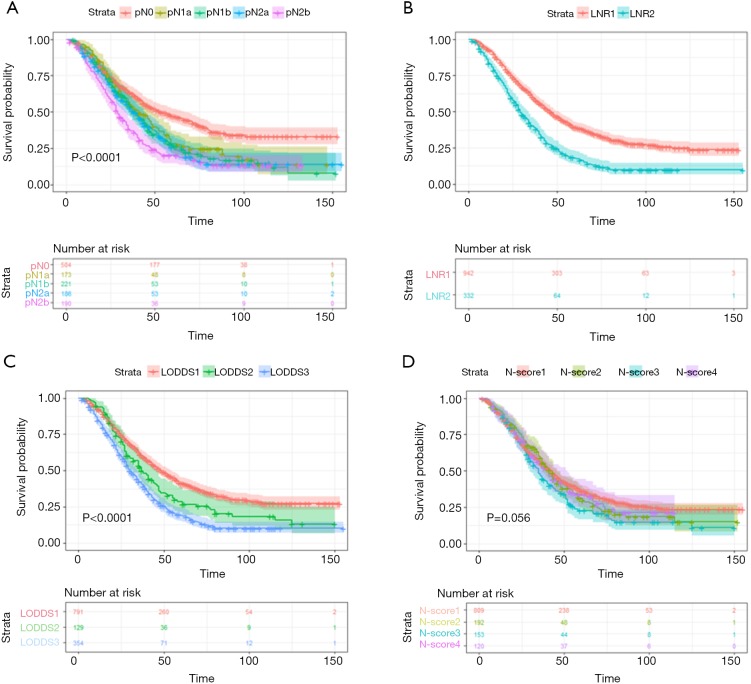

The survival curves of these subgroups depended on the AJCC N-stage, LNR, LODDS and N-score were presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patients stratified by the AJCC/UICC eighth edition (A), LNR (B), LODDS (C) and N-score (D) in non-radiation cohorts. LODDS, lymph node odds; LNR, lymph node ratio.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patients stratified by the AJCC/UICC eighth edition (A), LNR (B), LODDS (C) and N-score (D) in radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts. LODDS, lymph node odds; LNR, lymph node ratio.

Non-radiation cohorts

Generally, the 3- and 5-year survival were 37.00%, 18.80%. The 5-year survivals were determined after grouping patients into groups by AJCC/UICC N-staging: N0 27.32%, N1a 25.77%, N1b 22.76%, N2a 16.50%, N2b 10.38% (P<0.001) while there was no statistic difference between N0 and N1a (P=0.776). And the 5-year survival of people with LNR1 and LNR2 were 25.20%, 9.08% (P<0.001), respectively. Meanwhile, LODDS also divided patients into three subgroups with distinctive 5-year survival: LODDS1 27.72%, LODDS2 17.96%, LODDS3 9.73% (P<0.001). At last, when it came into N-score, the survival in the subgroups was not the same: N-score 1 20.5%, N-score 2 19.6%, N-score 3 12.5%, N-score 4 18.36% (P<0.001), while only the difference between the N-score 1 and N-score 3 was statistically significant (P=0.007).

The four staging systems both had statistic significant correlations with CSS in univariate analysis (Table 3). After balancing the status of gender, age, T stage, histologic grade and the primary sites, the difference of survival in all the subgroups based on 4 staging system both exhibited statistic significance, except N-score. With one more lymph-node retrieved, the risk of death would decrease 0.98% (P=0.001) while one more positive lymph node collected prompted the death risk would rise 2.70% in multivariate analysis (P<0.001). The N-stage pN1a failed to depict the different survival for patients in comparison with the ones without metastatic LNs (pN1a HR=1.0685, 95% CI: 0.9160–1.2464, P=0.3937). By the same time, LNR2 presented 67.1% increasing death risk (HR=1.6475, 95% CI: 1.5187–1.7873, P<0.001) while LODDS2 and LODDS3 exhibited 38.10% and 74.00% increased risk of death (LODDS2 HR=1.3810, 95% CI: 1.2110–1.5748, P<0.001; LODDS3 HR=1.7400, 95% CI: 1.5969–1.8960, P<0.001).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses for 4 staging schemes.

| Non-radiation Cohorts | RPS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis* | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis* | ||||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||||

| N-stage | |||||||||||

| pN0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| pN1a | 1.0220 (0.8768–1.1900) |

<0.001 | 1.0685 (0.9160–1.2464) |

0.3937 | 1.3937 (1.1200–1.734) |

0.0029 | 1.3860 (1.1098–1.7319) |

0.0097 | |||

| pN1b | 1.1920 (1.0427–1.3630) |

<0.001 | 1.2837 (1.1201–1.4712) |

0.0003 | 1.5592 (1.2780–1.9020) |

<0.001 | 1.5740 (1.2820–1.933) |

0.0040 | |||

| pN2a | 1.4290 (1.2529–1.6300) |

<0.001 | 1.4879 (1.3005–1.7022) |

<0.001 | 1.6379 (1.3320–2.0150) |

<0.001 | 1.7220 (1.3859–2.1389) |

<0.001 | |||

| pN2b | 1.8030 (1.5986–2.0330) |

<0.001 | 1.8584 (1.6388–2.1075) |

<0.001 | 2.0739 (1.6970–2.5340) |

<0.001 | 2.220 (1.7969–2.7423) |

<0.001 | |||

| LNR | |||||||||||

| LNR <0.05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 0.05≤ LNR <0.2 | 1.7330 (1.6010–1.8760) |

<0.001 | 1.6475 (1.5187–1.7873) |

<0.001 | 1.8621 (1.6090–2.1550) |

<0.001 | 1.9330 (1.6602–2.2510) |

<0.001 | |||

| LODDS | |||||||||||

| LODDS ≤−2.510 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| −2.510< LODDS ≤−1.680 | 1.3470 (1.1830–1.5340) |

<0.001 | 1.3810 (1.2110–1.5748) |

<0.001 | 1.3773 | 0.0048 | 1.3890 (1.1080–1.7420) |

0.0044 | |||

| −1.680< LODDS ≤−0.510 | 1.8000 (1.6550–1.9570) |

<0.001 | 1.7400 (1.5969–1.8960) |

<0.001 | 1.8879 (1.6260–2.1920) |

<0.001 | 1.9540 (1.6719–2.2830) |

<0.001 | |||

| N-score | |||||||||||

| N-score <4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 4≤ N-score <8 | 0.9893 (0.8935–1.0950) |

0.8361 | 1.0195 (0.9195–1.1305) |

0.7135 | 1.0832 (0.8920–1.315) |

0.4200 | 1.0420 (0.8535–1.2728) |

0.6843 | |||

| 8≤ N-score <15 | 1.1984 (1.0700–1.3420) |

0.0017 | 1.2358 (1.1021–1.3857) |

0.0002 | 1.3240 (1.0824–1.6200) |

0.0063 | 1.322 (1.0727–1.6303) |

0.0089 | |||

| 15≤ N-score | 1.0623 (0.9459–1.1930) |

0.30757 | 1.0490 (0.9314–1.1814) |

0.4304 | 1.0789 (0.8498–1.370) |

0.5331 | 1.1430 (0.8932–1.4631) |

0.2877 | |||

*, Multivariate analysis including age, gender, histologic grade, tumor size, T-stage, different site of tumor, chemotherapy status and each staging system. RPS, radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts.

Radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts

The 3-year and 5-year survival of this cohorts were 55.00% and 33.50%. If patients had radiotherapy prior to surgery, a positive LN indicated the risk of death for patients would go up 5.32% (HR=1.0532, 95% CI: 0.9495–1.0395, P<0.001) while one more LN retrieved signified the 1.25% decreasing risk of death (HR=0.9877, 95% CI: 1.0125–0.9790, P=0.006). The 5-year survival of 5 N-stage subgroups was 47.06%, 28.10%, 27.10%, 25.47%, 20.08% (P<0.001). However, N1a and Nab (P=0.359), N1a and N2a (P=0.198), N1b and N2a (P=0.716) were not statistical significant. With cutoff point of 0.36, LNR1 and LNR2 had different survival rate (LNR1 39.30%, LNR2 17.90%, P<0.001). Stratified by LODDS, the three groups had significantly different survival: LODDS1 41.22%, LODDS2 28.79% and LODDS 3 19.16% (P<0.001).

Compared with patients short of PLN, people in N1a stage had 39.97% increasing risk (N1a HR=1.3997, 95% CI: 1.1226–1.7451, P=0.003). By the same time, unlike previous condition, the N-stage could separate those patients with distinguish hazard ratio (N1b HR=1.5611, 95% CI: 1.2735–1.9136, P<0.001; N2a HR=1.6798, 95% CI: 1.3537–2.0844, P<0.001; N2b HR=2.1853, 95% CI: 1.7738–2.6923, P<0.001). Similar with previous group, LODDS2 and LODDS3 also had 38.53% and 93.25% increasing risk then LODDS1 (LODDS2 HR=1.3853, 95% CI: 1.1056–1.7357, P=0.005; LODDS3 HR=1.9325, 95% CI: 1.6557–2.2555, P<0.001), and LNR2 had 89.94% increasing risk than LNR1 (LNR2 HR=1.8984, 95% CI: 1.6329–2.2070, P<0.001) (Table 3).

Performance of varied LN staging/scoring systems

For assessing the accuracy of four LNs-based schemes, we performed C-index and AIC counting. When categorized by the condition of radiation, the performance of 4 staging schemes was presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Prognosis performance of lymph nodes staging based on evaluation by C-index and AIC.

| Non-radiation cohorts | RPS | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | TNLE <12 | 12< TNLE <25 | TNLE >25 | General | TNLE <12 | 12< TNLE <25 | TNLE >25 | ||||||||||||||||

| C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | C-index | AIC | ||||||||

| Continuous variables | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| LNR | 0.5903 | 3,680.601 | 0.5574 | 1,060.943 | 0.6081 | 1,696.71 | 0.6009 | 416.3431 | 0.5809 | 1,060.083 | 0.5688 | 481.211 | 0.6001 | 390.145 | 0.5407 | 43.2119 | |||||||

| LODDS | 0.5971 | 3,680.017 | 0.5654 | 1,060.202 | 0.6084 | 1,697.307 | 0.6005 | 417.0892 | 0.5912 | 1,058.765 | 0.5777 | 480.743 | 0.6039 | 389.544 | 0.5349 | 43.536 | |||||||

| N-score | 0.4918 | 3,705.123 | 0.5190 | 1,065.144 | 0.4929 | 1,710.872 | 0.5609 | 419.3464 | 0.4954 | 1,068.141 | 0.5159 | 483.730 | 0.4975 | 394.698 | 0.5843 | 43.487 | |||||||

| Categorical variables | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| AJCC/UICC 8th Edition | 0.5643 | 3,692.224 | 0.5400 | 1,063.164 | 0.5997 | 1,698.015 | 0.5723 | 419.7306 | 0.5688 | 1,062.943 | 0.5678 | 481.940 | 0.5933 | 390.395 | 0.5513 | 44.311 | |||||||

| LNR | 0.5686 | 3,687.317 | 0.5447 | 1,060.203 | 0.5751 | 1,701.111 | 0.5807 | 417.88023 | 0.5644 | 1,061.763 | 0.5558 | 481.660 | 0.5699 | 391.619 | 0.5704 | 43.351 | |||||||

| LODDS | 0.5756 | 3,686.433 | 0.5419 | 1,062.535 | 0.5869 | 1,700.172 | 0.5830 | 418.2158 | 0.5700 | 1,061.703 | 0.5575 | 481.895 | 0.5768 | 391.603 | 0.5715 | 43.548 | |||||||

| N-score | 0.5107 | 3,704.488 | 0.5361 | 1,063.269 | 0.5263 | 1,709.71 | 0.5773 | 417.9618 | 0.5108 | 1,067.837 | 0.5472 | 482.481 | 0.5125 | 394.664 | 0.5663 | 43.731 | |||||||

RPS, radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts.

Non-radiation cohorts

In the cohorts of none radiation received, based on the previous cut-off values, the LODDS (C-index: 0.5756, AIC: 3,686.433) performed better than the other three, including wildly applied N-stage (C-index: 0.5643, AIC: 3,692.224). Although LNR (C-index: 0.5686, AIC: 3,687.317) was not as sensitive as AJCC N-stage, it still had better performance than N-score (C-index: 0.5107, AIC: 3,704.488).

When taking TNLE into account, unlike we former understanding, the N-staging outperformed the other three only if there were 12–25 LNs retrieved (12< TNLE <25 C-index: 0.5997, AIC: 1,698.015; TNLE >25 C-index: 0.5723, AIC: 419.731). With 12–25 lymph nodes retrieved, LODDS (C-index: 0.5869, AIC: 1,700.172) was more sensitive than LNR (C-index: 0.5751, AIC: 1,701.111) and N-score (C-index: 0.5263, AIC: 1,709.71). With less than 12 TNLE, LODDS (C-index: 0.5419, AIC: 1,062.535) shown better performance than LNR (C-index: 0.5400, AIC: 1,063.164), N-stage (TNLE <12 C-index: 0.5400, AIC: 1,063.164) and N-score (C-index: 0.5361, AIC: 1,063.269). When there were more than 25 LNs retrieved, the LODDS (C-index: 0.5830, AIC: 418.216) remained better nature than either LNR (C-index: 0.5807, AIC: 417.880) or N-score (C-index: 0.5773, AIC: 417.962).

As continuous variable, the LODDS performed better than the other three (C-index: 0.5971, AIC: 3,680.017). When there were less than 25 retrieved, the LODDS shown the highest C-index and lowest AIC (TNLE <12 C-index: 0.5654, AIC: 1,060.202; 12< TNLE <25 C-index: 0.5654, AIC: 1,060.202) while the LNR (TNLE <12 C-index: 0.5574, AIC: 1,060.943; 12< TNLE <25 C-index: 0.6081, AIC: 1696.71) performed better than N-score (TNLE <12 C-index: 0.5190, AIC: 1,065.144; 12< TNLE <25 C-index: 0.4929, AIC: 1,710.872). When more than 25 lymph nodes collected, LODDS (C-index: 0.6005; AIC: 417.089) still exhibited better performance with N-score (C-index: 0.5609, AIC: 419.346) while LNR (C-index: 0.6009, AIC: 416.343) performing slightly more remarkable than LODDS.

Radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts

In the cohorts of patients received radiation therapy prior to surgery, LODDS (C-index: 0.5700, AIC: 1061.703) still performed superior than N-stage (C-index: 0.5688, AIC: 1062.943), and the latter performed better than LNR (C-index: 0.5644, AIC: 1061.763) and N-score (C-index: 0.5108; AIC: 1067.837). N-staging outperformed the other three only if there were less than 25 LNs retrieved (TNLE <12 C-index: 0.5678, AIC: 481.940; 12< TNLE <25 C-index: 0.5933, AIC: 390.395). With inadequate lymph nodes retrieved (TNLE <12), LODDS (C-index: 0.5575, AIC: 481.895) was more sensitive than LNR (C-index: 0.5558, AIC: 481.660) and N-score (C-index: 0.5472, AIC: 482.481). With 12–25 TNLE, LODDS (C-index: 0.5768, AIC: 391.603) shown better performance than LNR (C-index: 0.5699, AIC: 391.619) and N-score (C-index: 0.5125, AIC: 394.664). When there were more than 25 LNs retrieved, the LODDS (C-index: 0.5715; AIC: 43.548) remained better nature than LNR (C-index: 0.5704, AIC: 43.351), AJCC N-staging (C-index: 0.5513, AIC: 44.311) and N-score (C-index: 0.5663, AIC: 43.731).

Regard as continuous variables, LODDS (C-index: 0.5912, AIC: 1,058.765) presented as better lymph nodes schemes than LNR (C-index: 0.5809, AIC: 1,060.083) while LNR could be utilized to predict overall survival more accurately than N-score (C-index: 0.4954, AIC: 1,068.141). When there were over 25 lymph nodes retrieved, N-score (C-index: 5843, AIC: 43.487) seemed to present better C-index while the stability of the model was worse than LNR (C-index: 5407, AIC: 43.212).

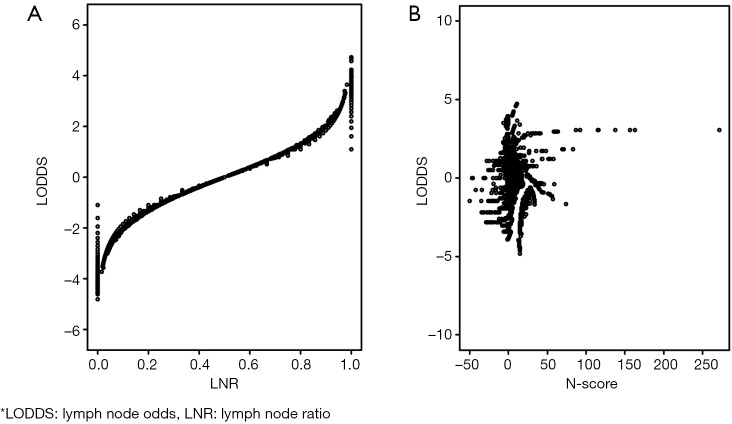

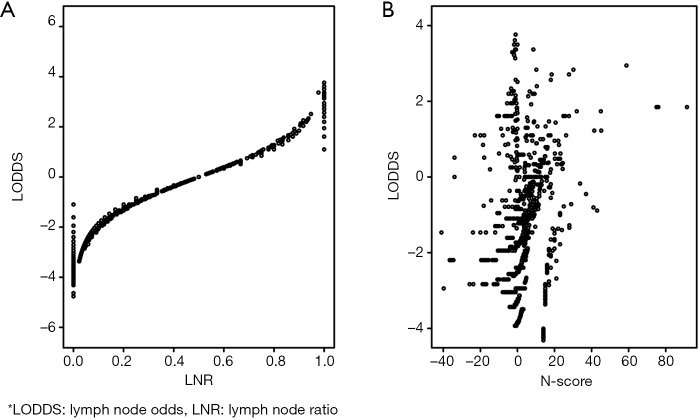

For further exploit the relationship between these prognostic models, we drew the plot figures to depict LODDS and other three systems. As shown in Figure 2, in same LNR group, LODDS could distinguish the varied survival status while N-score presented complicated relationship with LODDS. This may part explain the distinction of these staging systems (Figures 3,4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of LODDS vs. LNR (A), LODDS vs. N-score (B) in non-radiation cohorts. LODDS, lymph node odds; LNR, lymph node ratio.

Figure 4.

Distribution of LODDS vs. LNR (A), LODDS vs. N-score (B) in radiation-prior-to-surgery cohorts. LODDS, lymph node odds; LNR, lymph node ratio.

Discussion

The standard managements for patients with metastatic rectal cancer are not consistent (13,14). Despite of requisite chemotherapy and radiation, resection of the primary tumor has been proposed to be beneficial for incurable patients (2,4). As one of the most crucial parameters for prognosis, lymph nodes status has been proposed as an independent prognostic element of survival and recurrence among patients with rectal cancer (5,15), while it is controversial how many LNs should be retrieved in stage IV rectum cancer (16). The clinical indications have been extended with the role of lymph nodes known gradually. Since the differentiating the prognosis between patients with or without positive LN retrieved, the number of metastatic lymph nodes has been wildly used by AJCC/UICC for prognosis in patients with rectal carcinoma. However, some experts found out that due to stage-migration, only with enough lymph nodes retrieved would the positive LNs exhibit prognosis power, which meant both the total number collected and the positive number pathologic confirmed should be taken account in staging system. Further, the guideline of AJCC/UICC suggested that only with more than 12 LNs retrieved could the N-stage present satisfied performance. So that, many studies have attempted to advocate other staging systems with LNs involvement. Lykke et al. advocated that the LNR could reflect the influence of total lymph nodes status on the survival and be utilized as a supplement for the TNM staging (14). Although LNR was firstly advocated and wildly verified, the obvious disadvantage is that it is incompetent to distinguish the patients with different number of TNLE in N0 stage. Hence, LODDS was illustrated to cover this shortage. By the same time, to avoid no-linear relationship between TNLE and positive lymph nodes, Gleisner et al. (11) constructed the model called “N-score”. There have been several studies focused on comparing the 4 of LN stage systems, though none of them paid particular attention to stage IV rectal cancer. Our study is unique for specialty in the rectum adenocarcinoma with the distant metastatic. In the prior radiation cohorts of our study, with less than 25 lymph nodes retrieved, the AJCC/UICC N-staging outperformed LNR and other cited systems. This may due to the complicated condition of lymph nodes status in rectal carcinoma after radiotherapy. Unlike colon cancer, the TNLE was limited because of the pre-operation radiotherapy and difficulties of operations (17). And with increasing TNLE, the proportion of patients with positive lymph nodes would increase, accordingly. On the other hand, when patients did not get radiation preoperative, only with enough and not too much lymph node collected, could N-stage system present excellent performance than others. And we proposed that LODDS exhibited as more favorable measure for prognosis generally, although N-stage outperformed the other three with less than 25 LNs retrieved.

Status of lymph nodes is crucial prognosis factor in many malignancies (18,19). More LNs retrieved improved overall survival by not only reducing further metastasis but also assisting in more accurate prognosis of survival. In our study, with one more lymph node retrieved, the risk of death would decrease 0.99% (HR=0.9902, 95% CI: 0.9865–0.9938, P<0.001) and with one more metastatic lymph node, the risk of death would increase 5.20% (HR=1.0520, 95% CI: 1.0462–1.0579, P<0.001). On the whole, compared with pN0 stage, pN1a had 14% increasing risk of death (HR=1.140, 95% CI: 1.003–1.295, P=0.0446). Unexpectedly, when patients without any radio therapy were selected, the distinguished capacity between pN0 to pN1adid not shown static significance (HR=1.044, 95% CI: 0.8905–1.224, P=0.597). In the multicentric population study of 548 colon cancer between January 2004 and December 2007, for disease-free survival, pN0 and pN1 groups failed to distinguish the survival of patients, but it could be shown in LNR and LODDS subgroups which could be sufficiently supplement for estimating the survival prognosis (10).

For cancer in rectum, neoadjuvant radiation therapy is becoming more and more prevail, and the post-radiation reaction of tissue may influence the lymph nodes status (17). In our study, in patients who did not receive radiotherapy prior to the surgery, the LODDC presented more discriminatory ability generally while N-stage exhibited more desirable performance with 12–25 LNs retrieved. Although this may be part due to the limited population included and the uneven distribution of the patients’ treatment condition in our study, the performance of LODDS in assessment of prognosis was extraordinary because: LODDS took full advantage of both the TMLE and TNLE; LODDS presented as an efficient LN-based risk factor on multivariate analyses, while N-stage failed to distinguish the difference of survival in patients of some subgroups; estimated with C-index and AIC, LODDS held better discriminatory ability for prognosis, especially in patients with LNR0; LODDS subgroups could be combined with other staging-systems for further improvement.

To our best knowledge, this is the first study that tended to evaluate the prognostic accuracy for AJCC N-stage, N-score, LNR and LODDS directly in stage IV rectal adenocarcinoma. However, there were still several limitations in this study. Firstly, as a retrospective study, selection bias was inevitable. Secondly, previous study exhibited that different distant metastatic organ could influence the overall survival (20). However, due to the incomplete metastatic information before 2015 in SEER database, this study did not have enough assessment for the metastatic site of the patients due to limited information of database. Of note, the specific location of each lymph node and extent of lymphadenectomy were also not mentioned in the SEER database, which could also impact the outcome of staging systems. Thirdly, with regard to different institutions included in the SEER database, neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment plans in this study were not consistent. Last, as the definition of tumor deposits keep changing for decades, the data of N1c stage was not included in this study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the discriminative abilities of different staging systems were distinct in stage IV rectum cancer with different TNLE. When assessed as categorical variables, despite of different conditions of neoadjuvant radiotherapy, N-stage performed superiorly if adequate lymph nodes were examined. LODDS showed, when assessed as a continuous variable, good discriminative ability and goodness of fit in predicting survival for rectal cancer patients regardless of TNLE.

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Goodman KA, Milgrom SA, Herman JM, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(R) rectal cancer: metastatic disease at presentation. Oncology (Williston Park) 2014;28:867-71, 876, 878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piso P, Arnold D, Glockzin G. Challenges in the multidisciplinary management of stage IV colon and rectal cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;9:317-26. 10.1586/17474124.2015.957273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchs NC, Ris F, Majno PE, et al. Rectal outcomes after a liver-first treatment of patients with stage IV rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:931-7. 10.1245/s10434-014-4069-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi H, Kotake K, Funahashi K, et al. Clinical benefit of surgery for stage IV colorectal cancer with synchronous peritoneal metastasis. J Gastroenterol 2014;49:646-54. 10.1007/s00535-013-0820-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed S, Leis A, Chandra-Kanthan S, et al. Regional Lymph Nodes Status and Ratio of Metastatic to Examined Lymph Nodes Correlate with Survival in Stage IV Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:2287-94. 10.1245/s10434-016-5200-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Washington MK, Berlin J, Branton P, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:1539-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotake K, Honjo S, Sugihara K, et al. Number of lymph nodes retrieved is an important determinant of survival of patients with stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012;42:29-35. 10.1093/jjco/hyr164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger AC, Sigurdson ER, LeVoyer T, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with decreasing ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8706-12. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang HY, Yang H, He ZS, et al. Log odds of positive lymph nodes is superior to the number- and ratio-based lymph node classification systems for colorectal cancer patients undergoing curative (R0) resection. Mol Clin Oncol 2017;6:782-8. 10.3892/mco.2017.1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortea-Sanchis C, Martinez-Ramos D, Escrig-Sos J. The lymph node status as a prognostic factor in colon cancer: comparative population study of classifications using the logarithm of the ratio between metastatic and nonmetastatic nodes (LODDS) versus the pN-TNM classification and ganglion ratio systems. BMC Cancer 2018;18:1208. 10.1186/s12885-018-5048-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleisner AL, Mogal H, Dodson R, et al. Nodal status, number of lymph nodes examined, and lymph node ratio: what defines prognosis after resection of colon adenocarcinoma? J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:1090-100. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou R, Zhang J, Sun H, et al. Comparison of three lymph node classifications for survival prediction in distant metastatic gastric cancer. Int J Surg 2016;35:165-71. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.09.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shida D, Boku N, Tanabe T, et al. Primary Tumor Resection for Stage IV Colorectal Cancer in the Era of Targeted Chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Surg 2019;23:2144-50. 10.1007/s11605-018-4044-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lykke J, Jess P, Roikjaer O, et al. The prognostic value of lymph node ratio in a national cohort of rectal cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:504-12. 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun HR, Lee WY, Lee WS, et al. The prognostic factors of stage IV colorectal cancer and assessment of proper treatment according to the patient's status. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1301-10. 10.1007/s00384-007-0315-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Concors SJ, Vining CM, Saur NM, et al. Combined Proctectomy and Hepatectomy for Metastatic Rectal Cancer Should be Undertaken with Caution: Results of a National Cohort Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:3972-9. 10.1245/s10434-019-07497-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mechera R, Schuster T, Rosenberg R, et al. Lymph node yield after rectal resection in patients treated with neoadjuvant radiation for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2017;72:84-94. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Percy DB, Pao JS, McKevitt E, et al. Number of nodes in sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: Are surgeons still biased? J Surg Oncol 2018;117:1487-92. 10.1002/jso.25010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gigliarano C, Nonis A, Briganti A, et al. Effect of the number of removed lymph nodes on prostate cancer recurrence and survival: evidence from an observational study. BMC Bioinformatics 2018;19:200. 10.1186/s12859-018-2180-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaitanidis A, Alevizakos M, Tsaroucha A, et al. Predictive Nomograms for Synchronous Distant Metastasis in Rectal Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:1268-76. 10.1007/s11605-018-3767-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]