We read with great interest the paper by Safi et al. (1) describing frameshifts in glpK’s homopolymeric tract (HT) of seven cytosines (7C) as a potential cause of antibiotic tolerance. These results have implications for tuberculosis (TB) treatment, but other forces than antibiotic pressure may be responsible for the emergence of glpK mutations (1, 2). We raise the possibilities of selection in vitro, selection in vivo from nonantibiotic host factors, and population bottlenecks in determining the fate of glpK frameshifts.

In a recent study (3), we observed the landscape of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutations occurring longitudinally in-host for 200 subjects with active TB disease. We tracked mutations arising in-host between two sputum samples taken at different time points during and/or after treatment. To approximate the experimental noise, we analyzed mutations arising between 62 technical replicate pairs of isolates with interval passaging in vitro and/or freezing without antibiotic exposure. Mutations between replicates are thus unrelated to any in-host selection and may result from genetic drift or in vitro selection.

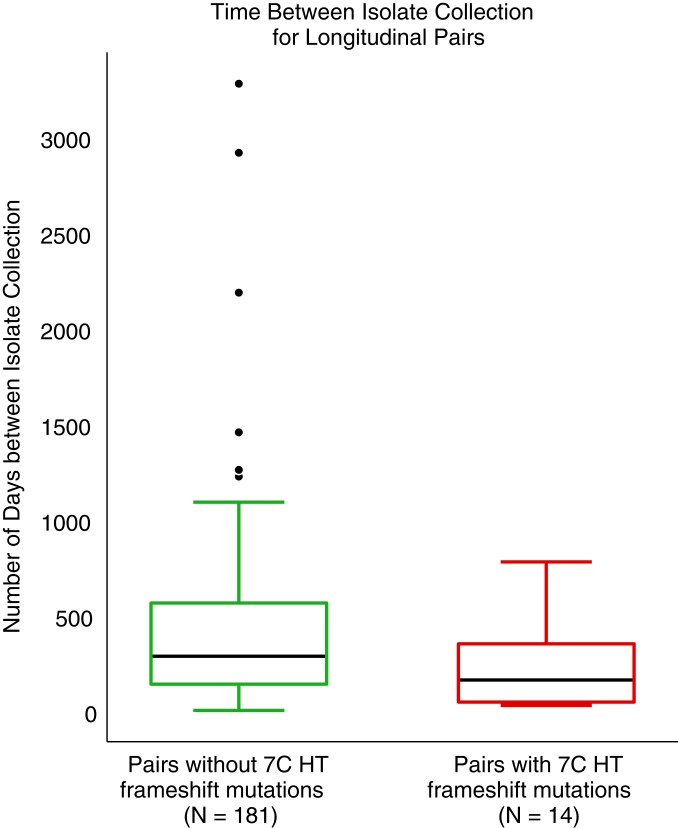

We detected four glpK nonsynonymous mutations (nSNPs) from 200 longitudinal pairs and five nSNPs from 62 replicate pairs (Table 1). Additionally, we observed frameshifts in the 7C HT of glpK (1, 2) to occur commonly between both longitudinal and replicate isolate pairs. GlpK frameshifts were detected more commonly among technical replicates (13/62 vs. 14/200 OR = 2.9, P = 0.003 Fisher’s exact test). We assessed whether glpK frameshifts were more abundant as a function of time between sputum samplings (Fig. 1). Isolates with glpK frameshifts were sampled at similar intervals to those without, indicating that chronic infection or longer duration of antibiotic exposure did not associate with a higher prevalence of these variants.

Table 1.

Mutations detected within the coding sequence for glpK between 200 longitudinal and 62 replicate isolate pairs

| H37Rv reference position | H37Rv reference allele | Alternate allele | Change in allele frequency | H37Rv locus tag | Isolate pair type | Gene position | Variant type | Amino acid change/indel type | Alternate allele frequency A | Alternate allele frequency B |

| 4138945 | A | G | 0.41 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 811 | nSNP | C271R | 0.41 | 0 |

| 4138645 | G | A | 0.93 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 1111 | nSNP | P371S | 0.93 | 0 |

| 4138599 | C | A | 0.43 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 1157 | nSNP | R386L | 0.43 | 0 |

| 4138398 | G | A | 0.79 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 1358 | nSNP | A453V | 0.79 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.386781609 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.903448276 | 0.516666667 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.573228751 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.910891089 | 0.337662338 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.941666667 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.941666667 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.633663366 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.633663366 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.894736842 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.894736842 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.882352941 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.882352941 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.534482759 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.534482759 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.95323741 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.95323741 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.326530612 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.326530612 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.827160494 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.827160494 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.818181818 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.818181818 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.873417722 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.873417722 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.627118644 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.627118644 |

| 4139183 | AC | A | 0.495798319 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 573 | Indel | Deletion | 0 | 0.495798319 |

| 4138684 | CG | C | 0.343065693 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 1072 | Indel | Deletion | 0.343065693 | 0 |

| 4138376 | C | CA | 0.507246377 | Rv3696c | Longitudinal | 1380 | Indel | Insertion | 0 | 0.507246377 |

| 4139424 | G | A | 0.28 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 332 | nSNP | A111V | 0 | 0.28 |

| 4139083 | G | A | 0.38 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 673 | nSNP | R225W | 0 | 0.38 |

| 4138995 | G | A | 0.29 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 761 | nSNP | P254L | 0 | 0.29 |

| 4138398 | G | A | 0.81 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 1358 | nSNP | A453V | 0.02 | 0.83 |

| 4138326 | A | G | 0.47 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 1430 | nSNP | L477P | 0 | 0.47 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.521403509 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.894736842 | 0.373333333 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.470588235 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.5 | 0.970588235 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.85 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.85 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.25 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.25 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.447058824 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.447058824 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.670807453 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.670807453 | 0 |

| 4139183 | AC | A | 0.237288136 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Deletion | 0.237288136 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.534482759 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.534482759 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.513513514 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.513513514 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.573863636 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.573863636 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.561643836 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.561643836 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.348314607 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.348314607 | 0 |

| 4139183 | A | AC | 0.868686869 | Rv3696c | Replicate | 573 | Indel | Insertion | 0.868686869 | 0 |

SNPs were reported for a pair only if the alternate allele frequency between both isolates changed by at least 25%. Indels were reported if the alternate allele was detected at any allele frequency in at least one isolate for each pair. In a majority of cases, the mutant allele was detectable only in one of the isolates in each pair. The values in columns alternate allele frequency A and alternate allele frequency B are ordered according to sample collection dates for the longitudinal pairs. This ordering is arbitrary for replicate pairs since we did not have sample collection dates for the replicate isolates.

Fig. 1.

Emergence of glpK frameshift mutations in-host. Isolate collection times were available for 195/200 longitudinal pairs, and glpK frameshift mutations were detected in 14/195 longitudinal pairs. Boxplots display the number of days elapsed between isolate collections from subjects with active TB disease in which no glpK frameshift mutations were called (median 291 d) and in which a glpK frameshift mutation was called (median 167 d).

Our data confirm that nSNPs and reversible frameshifts are common within glpK but the frequency varies with several factors that include experimental conditions, genetic drift following a sampling bottleneck, and/or selection in culture on glycerol-based media. Pethe et al. (4) showed that M. tuberculosis glycerol dissimilation was dispensable in a mouse model of TB, suggesting that glpK is dispensable for growth in humans. We hypothesize parsimoniously that inactivating glpK mutations may arise in-host due to the cost of protein production for a potentially dispensable enzyme rather than selection pressure from antibiotic treatment. Adding antibiotic pressure results in a population bottleneck or may increase the fitness differential between strains with and without glpK frameshifts. Once samples are isolated and cultured in the presence of glycerol, bacteria can rapidly revert to wild type since glpK function is necessary for glycerol catabolism (2) as demonstrated by Safi et al. (1) in their in vitro passaging experiments.

Still, the evidence presented makes a strong case that glpK mutations alter drug tolerance in glycerol-containing culture media (1). Further research including the sequencing of M. tuberculosis directly from sputum can overcome the problems of selection and bottlenecks related to in vitro culture (5). Clinical studies assessing treatment outcomes for TB with and without glpK variants are also needed to assess the potential future use of glpK inhibitors for patient treatment.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Safi H., et al. , Phase variation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis glpK produces transiently heritable drug tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 19665–19674 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellerose M. M., et al. , Common variants in the glycerol kinase gene reduce tuberculosis drug efficacy. MBio 10, e00663-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vargas R., et al. , In-host population dynamics of M. tuberculosis during treatment failure. bioRxiv:726430 (6 August 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pethe K., et al. , A chemical genetic screen in Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies carbon-source-dependent growth inhibitors devoid of in vivo efficacy. Nat. Commun. 1, 57 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmo C., et al. , Whole genome sequencing Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from sputum identifies more genetic diversity than sequencing from culture. BMC Genomics 20, 389 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]