Significance

It is well known that AKT inactivates glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) by increasing its phosphorylation. The inactivation of GSK3β leads to aberrant phosphorylation of Tau, which is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. However, we found that if phosphorylated AKT is sulfhydrated, it will be unable to inactivate GSK3β and subsequently increases Tau phosphorylation. The influence of sulfhydrated AKT on GSK3β and Tau phosphorylation was reversed in a transgenic AKT-KI+/+ mouse, where sulfhydration of AKT residue was mutated to alanine. Thus, AKT-sulfhydration represents a unique posttranslational modification of AKT that can be targeted to suppress phosphorylation of GSK3β and subsequently reduce Tau phosphorylation.

Keywords: AKT, Tau phosphorylation, sulfhydration, GSK3β

Abstract

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), human Tau is phosphorylated at S199 (hTau-S199-P) by the protein kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). HTau-S199-P mislocalizes to dendritic spines, which induces synaptic dysfunction at the early stage of AD. The AKT kinase, once phosphorylated, inhibits GSK3β by phosphorylating it at S9. In AD patients, the abundance of phosphorylated AKT with active GSK3β implies that phosphorylated AKT was unable to inactivate GSK3β. However, the underlying mechanism of the inability of phosphorylated AKT to phosphorylate GSK3β remains unknown. Here, we show that total AKT and phosphorylated AKT was sulfhydrated at C77 due to the induction of intracellular hydrogen sulfide (H2S). The increase in intracellular H2S levels resulted from the induction of the proinflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, which is a pathological hallmark of AD. Sulfhydrated AKT does not interact with GSK3β, and therefore does not phosphorylate GSK3β. Thus, active GSK3β phosphorylates Tau aberrantly. In a transgenic knockin mouse (AKT-KI+/+) that lacked sulfhydrated AKT, the interaction between AKT or phospho-AKT with GSK3β was restored, and GSK3β became phosphorylated. In AKT-KI+/+ mice, expressing the pathogenic human Tau mutant (hTau-P301L), the hTau S199 phosphorylation was ameliorated as GSK3β phosphorylation was regained. This event leads to a decrease in dendritic spine loss by reducing dendritic localization of hTau-S199-P, which improves cognitive dysfunctions. Sulfhydration of AKT was detected in the postmortem brains from AD patients; thus, it represents a posttranslational modification of AKT, which primarily contributes to synaptic dysfunction in AD.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by a progressive loss of memory, cognitive impairments, behavioral difficulties, and ultimately death (1–3). Synaptic dysfunction and hence memory impairments emerge early in the disease process (1, 4, 5). The microtubule-associated protein Tau is most abundant in the neuronal axons in healthy cells; however, at the early stages of AD, Tau can be mislocalized to dendrites after its specific phosphorylation at S199 (6–8). Human Tau (hTau) phosphorylation at S199 triggers synaptotoxicity independent of Tau aggregation and correlates with memory impairment in AD (9–11). Among the kinases that phosphorylate Tau, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) is implicated in AD pathology because activation of GSK3β is essential for Tau phosphorylation at S199 (12–16). However, the molecular mechanism responsible for Tau phosphorylation at S199 remains poorly understood.

GSK3β is a constitutively active kinase that is inactivated by phosphorylation at S9 (17, 18). In GSK3β-S9A transgenic mice overexpressing hTau, Tau phosphorylation was increased (19). AKT is a serine/threonine kinase that phosphorylates GSK3β at S9 (20, 21). Thus, AKT plays a critical role in the modulation of GSK3β activity. Therefore, engagement of signaling pathways that activate AKT results in the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9, followed by down-regulation of GSK3β activity (22). AKT is activated by phosphorylation at T308 and S473, which are located in the regulatory domain of the enzyme (20, 23). The brains of AD patients contain highly abundant levels of active phosphorylated AKT (24, 25) concomitant with an increase in GSK3β activity (26–28). However, it remains undetermined how GSK3β remains activated even in the presence of phosphorylated AKT.

The early induction of inflammatory cytokines is the most common feature in vulnerable areas of AD patients’ brains and body fluids (29–32). These inflammatory cytokines are associated with the cognitive decline observed in AD patients (33). Previously, we showed that the proinflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, could induce intracellular hydrogen sulfide (H2S) levels by augmenting the expression of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), which catalyzes the formation of H2S (34). H2S is a gasotransmitter that activates intracellular signaling pathways through the sulfhydration of proteins. This modification occurs when the sulfur from H2S attaches to a cysteine residue (–SH) of a protein and converts it to –SSH (35, 36).

In the present study, we show that sulfhydration of total or phosphorylated AKT inhibits its interaction with GSK3β and subsequently down-regulates the phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β. The activated GSK3β facilitates Tau phosphorylation and cognitive dysfunction. In AKT knockin mice (AKT-KI+/+), where the sulfhydration of AKT was blocked, early Tau phosphorylation at S199 was attenuated upon stimulation with the proinflammatory cytokine, IL-1β.

Results

IL-1β Induces H2S-Dependent Tau Phosphorylation at S199.

Tau can be mislocalized to dendrites after its specific phosphorylation at S199 (6–8). Therefore, we monitored the phosphorylation of Tau at S199 in AD patients’ brains and a mouse model of AD (PS19). PS19 mice contain the hTau mutant (hTau-P301S) that is characterized by impaired synaptic function before fibrillary Tau tangles emerge at the age of 6 to 8 mo (37). We found that Tau phosphorylation at S199 was abundant in both AD patients’ brains (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) and in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice within the age of 2 mo (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Since IL-1β is highly abundant in AD patients’ brains and body fluids (38), and is associated with cognitive decline (33), we monitored the mRNA and protein levels of IL-1β in both the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice. We found that both IL-1β mRNA (Fig. 1C) and protein levels (Fig. 1D) were significantly increased in PS19 mice that were 2-mo-old. These data suggest that inflammation in PS19 mice is associated with Tau phosphorylation. However, in order to determine whether IL-1β is directly responsible for Tau phosphorylation, we overexpressed hTau-P301L in primary neurons before treatment with IL-1β. We found that IL-1β induced a robust increase in hTau phosphorylation at S199 (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). These data suggest that IL-1β is directly responsible for hTau phosphorylation. Thus, we explored the underlying mechanism of how IL-1β induces Tau phosphorylation at S199.

Fig. 1.

IL-1β induces Tau-phosphorylation in an H2S-dependent manner. (A) Western blot analysis using brain extracts isolated from AD patients and age-matched control brains showed that hTau-S199P level was increased. (B) Immunoprecipitation analysis using HT7 antibody explains that hTau-S199 phosphorylation (hTau-S199P) was increased in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice. (C and D) The mRNA level of IL-1β measured by quantitative RT-PCR and protein level of IL-1β by ELISA were increased in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice. (E) Administration of IL-1β induces hTau-S199 phosphorylation in primary neurons overexpressing hTau-P301L. (F and G) The immunofluorescent staining shows that the expression level of CBS was increased in the cortex (F) and hippocampus (G) of PS19 mice. (H and I) Intracellular H2S level (WSP1; green fluorescence) was increased in the cortex (H) and hippocampus (I) of PS19 mice. (J) The depletion of CBS by administration of CBS RNAi reduces hTau-S199 phosphorylation in the cortex of PS19 mice. (K) Confocal analysis showed that depletion of CBS by CBS RNAi reduces hTau-S199 phosphorylation in the cortex of PS19 mice. (L) The hTau-S199 phosphorylation was reduced in primary neurons isolated from CBS+/− mice compared to CBS+/+ neurons overexpressed with hTau-P301L and treated with IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. (M) The phosphorylation of hTau-S199 was increased in primary neurons overexpressing hTau-P301L after administration of IL-1β or GYY4137 (200, 300 μM). (N) administration of GYY4137 (300 μM) with or without IL-1β increases hTau-S199P in primary neurons depleted with CBS. (O and P) Confocal microscopic analysis (O) and quantitative analysis (P) using ImageJ showed that localization of hTau-S199P in dendrites were decreased in dendritic spines in PS19 mice after depletion of CBS. One-way ANOVA measured statistical significance with a Tukey–Kramer post hoc correction, n = 7, *P < 0.05. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The arrowheads in O indicate the dendritic spines. (Magnification: G–I, 20×; K, 40×; O, 60×.)

Previously, we showed that IL-1β could induce the expression of CBS, a catalytic enzyme responsible for synthesizing H2S (34). Thus, we hypothesized that IL-1β induces hTau phosphorylation by a mechanism that is dependent on H2S. In order to test this hypothesis, we monitored the intracellular levels of both CBS and H2S in murine PS19 brains. Consistent with our previous publication (34), we found that the expression of CBS (Fig. 1 F and G and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and E) and intracellular H2S (Fig. 1 H and I and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 F and G) was increased in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice. Furthermore, we found that the depletion of CBS (CBS RNAi) markedly reduced Tau phosphorylation at S199 in the cortex after administration of IL-1β to PS19 mice, as monitored by Western blotting (Fig. 1J and SI Appendix, Fig. S1H) and confocal analyses (Fig. 1K and SI Appendix, Fig. S1I). These data indicate that H2S plays an essential role in facilitating Tau phosphorylation. To further confirm our cell culture data in mice, we administered IL-1β to CBS+/+ and CBS+/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L in the cortex. In the PS19 brain, aberrant activation of nonneuronal cells, such as microglial cells, mostly contribute to the increase in IL-1β in the brain (37, 39). However, the production of inflammatory molecules in a healthy brain is minimal. Thus, to mimic the pathological conditions that are present in the PS19 brain, we administered IL-1β to CBS+/+ and CBS+/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L in the cortex. This study revealed that Tau phosphorylation was significantly decreased in CBS+/− mice compared to CBS+/+ mice (Fig. 1L and SI Appendix, Fig. S1J), but we could still detect Tau phosphorylation in the CBS+/− mice. This may be explained by the fact that the intracellular H2S levels were significantly decreased in CBS+/− mice, but not fully eliminated.

In order to directly monitor the influence of H2S on hTau phosphorylation, we administered the H2S donor, GYY4137, to primary neurons overexpressing hTau-P301L. We found that GYY4137 induced Tau phosphorylation at S199 in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, the increase in GYY4137-induced hTau phosphorylation was comparable to the hTau phosphorylation levels observed when IL-1β was administered to primary neurons overexpressing hTau-P301L (Fig. 1M and SI Appendix, Fig. S1K). We also found that administration of GYY4137 induced hTau phosphorylation in CBS-depleted neurons, and the increase in hTau phosphorylation was not further elevated after administration of IL-1β (Fig. 1N and SI Appendix, Fig. S1L). These data suggest that H2S, generated by CBS, is critical for IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of hTau at S199.

Since phosphorylation of Tau at S199 leads to its mislocalization to the spines (6–8), we monitored the localization of phosphorylated Tau in the spines of primary neurons isolated from PS19 mice. We found that phosphorylated Tau was highly abundant in the spines; however, it was reduced in CBS-depleted neurons (Fig. 1 O and P). These data suggest that H2S plays an essential role in regulating Tau phosphorylation, and the mislocalization of phosphorylated Tau to dendrites is induced by inflammatory stimuli. However, the underlying mechanism of how H2S induces hTau phosphorylation at S199 remains unanswered.

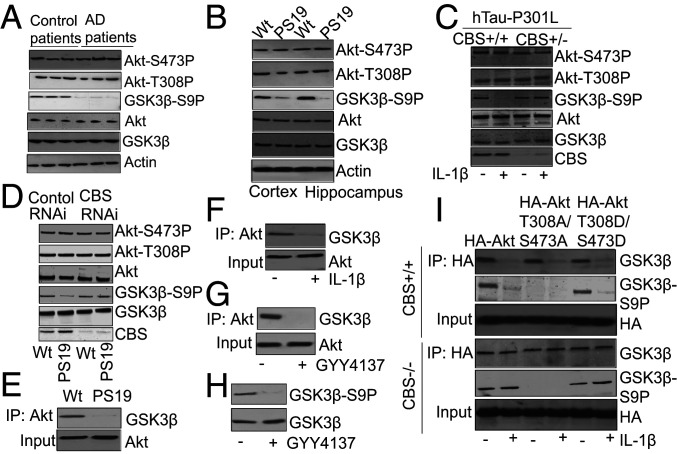

H2S Down-Regulates GSK3β Phosphorylation without Affecting AKT Phosphorylation.

Previous reports have suggested that the activation of protein kinase GSK3β is essential for Tau phosphorylation at S199 and GSK3β activity is inhibited by phosphorylation at S9 (17, 18). A decrease in GSK3β phosphorylation due to the inactivation of another protein kinase, AKT, leads to GSK3β activation (17, 21). The phosphorylation of T308 and S473 is necessary for the activation of AKT (40, 41). We monitored the phosphorylation levels of AKT and GSK3β in AD patients’ brains as well as the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice. Consistent with previous data (42), we found that AKT remained phosphorylated at S473 and T308 in AD patients’ brains (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) as well as the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). However, the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 was decreased in the AD patients’ brains (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A), as well as the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). To further confirm these results, we administered IL-1β to primary neurons isolated from CBS+/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L. Consistent with our in vivo results, we found that IL-1β did not affect AKT phosphorylation but reduced GSK3β phosphorylation at S9 (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). Furthermore, we observed that depletion of CBS in the PS19 cortex increased GSK3β phosphorylation at S9 without affecting the AKT phosphorylation status (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). These data suggest that H2S plays a significant role in regulating GSK3β phosphorylation, but it does not affect AKT phosphorylation. Since AKT is the major kinase that phosphorylates GSK3β, we investigated the mechanism of how H2S regulates GSK3β phosphorylation without affecting AKT phosphorylation.

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of GSK3β is dependent on H2S. (A) Western blot analysis using brain tissue lysates of AD patients showed that AKT phosphorylation at S473 (AKT-S473P) and T308 (AKT-T308P) remains unaltered, but phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β S9P) was decreased significantly. (B) Phosphorylation of AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P) and T308 (AKT-T308P) remains unaltered but phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β S9P) was decreased in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice analyzed by Western blot. (C) Administration of IL-1β in CBS+/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L rescued phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β S9P) compared to CBS+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L. (D) Western blot analysis showed that depletion of CBS after administration of CBS RNAi in PS19 mice rescued phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β S9P) although AKT phosphorylation at S473 (AKT-S473P) and T308 (AKT-T308P) remained unaltered. (E) The interaction between AKT and GSK3β was decreased in PS19 mice and analyzed by coimmunopreciptation (co-IP) analysis. (F) Administration of IL1β (10 ng) causes a decrease in the interaction between AKT and GSK3β in primary neuron culture. (G and H) Administration of GYY4137 (300 μM) causes a decrease in the interaction between AKT and GSK3β and the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 residue. (I) CBS+/+ or CBS−/− neurons overexpressing HA-AKT, HA-AKT-T308A/S473A, or HA-AKT-T308D/S473D were treated with IL-1β. Administration of IL-1β affects interaction between Akt and GSK3β and phosphorylation of GSK3β in CBS+/+ neurons compared to CBS−/− neurons.

In order to determine whether the phosphorylation status of GSK3β is dependent on the AKT–GSK3β complex, we monitored the interaction between AKT and GSK3β by coimmunoprecipitation assays using cortical lysates from PS19 mice. We found that the interaction between AKT and GSK3β was reduced in cortical lysates from PS19 mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). These results were further confirmed in primary neurons treated with IL-1β, which also had significantly reduced levels of the AKT–GSK3β complex compared to untreated cells (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2G). In order to study the effects of GYY4137 on the interaction between AKT and GSK3β, as well as the phosphorylation of GSK3β, we treated primary neurons with GYY4137. We found that GYY4137-treated cells had decreased levels of the AKT–GSK3β complex (Fig. 2G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2H), along with a reduction in GSK3β phosphorylation (Fig. 2H and SI Appendix, Fig. S2I) compared to untreated cells. These data suggest that H2S directly influences GSK3β phosphorylation by modulating the AKT–GSK3β interaction.

In order to elucidate whether the AKT–GSK3β interaction is dependent on AKT phosphorylation, we generated the following constructs expressing either: 1) Wild-type AKT (HA-AKT), 2) a mutant of AKT that abolishes the phosphorylation of the amino acids which are required for AKT activation (phospho-mutant; HA-AKT-T308A/S473A), or 3) a phospho-mimic AKT mutant (HA-AKT-T308D/S473D). These constructs were overexpressed in CBS+/+ and CBS−/− neurons and treated with IL-1β. We found that the interaction between AKT and GSK3β was decreased in neurons isolated from CBS+/+ mice following IL-1β administration, irrespective of the overexpression of either the phospho-mutant or the phospho-mimic mutant of AKT (Fig. 2I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2J). However, in CBS-depleted cells, the interaction between AKT and GSK3β remained unaltered with or without IL-1β treatment. In addition, the interaction between AKT and GSK3β remained unaltered after the overexpression of either the phospho-mutant or phospho-mimic mutant of AKT (Fig. 2I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2J). These data suggest that the interaction between AKT and GSK3β is not dependent on AKT phosphorylation; however, intracellular H2S levels, which were abolished in CBS−/− neurons, can modulate the interaction between AKT and GSK3β.

In order to examine whether the AKT–GSK3β complex has any influence on GSK3β phosphorylation, we monitored the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 in IL-1β–treated cells overexpressing HA-AKT, HA-AKT-T308A/S473A, or HA-AKT-T308D/S473D. We found lower levels of GSK3β phosphorylation at S9 in cells where the interaction of HA-AKT or HA-AKT-T308D/S473D with GSK3β was decreased after IL-1β treatment (Fig. 2I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2K). Since HA-AKT-T308A/S473A is a dead-kinase mutant of AKT, we found that it was unable to phosphorylate GSK3β irrespective of its interaction with GSK3β with or without IL-1β treatment (Fig. 2I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2K). These data suggest that the interaction between AKT and GSK3β is independent of the phosphorylation status of AKT, but it is required for AKT to phosphorylate GSK3β. Furthermore, we found that the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 remained unaltered in cells overexpressed with HA-AKT-T308D/S473D with or without administration of IL-1β (Fig. 2I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2K). These data suggest that phosphorylation of GSK3β is dependent on the interaction between AKT and GSK3β and intracellular H2S levels is critical to regulate the AKT–GSK3β interaction. However, the underlying mechanism of how H2S regulates the interaction between AKT-GSK3β has not been elucidated yet.

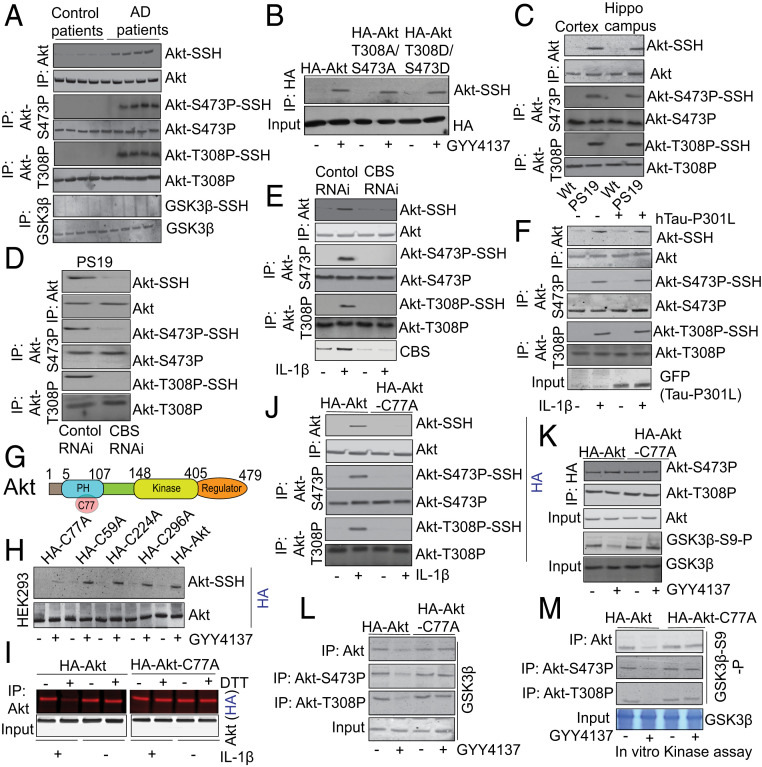

Sulfhydration of Phosphorylated AKT at C77 Inhibits the Formation of the AKT–GSK3β Complex and Prevents the Phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9.

H2S is known to function as an intracellular signaling molecule through the sulfhydration of proteins. Protein sulfhydration occurs when H2S attaches to a cysteine residue in a protein and converts the –SH to an –SSH (35, 36). We tested whether AKT, phosphorylated AKT, or GSK3β can be sulfhydrated in human AD samples. We detected sulfhydrated wild-type AKT (AKT-SSH) and sulfhydrated phosphorylated AKT (AKT-P-SSH) at either S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH). However, GSK3β was not sulfhydrated in AD patients’ brains (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). This was further confirmed in another experiment where administration of GYY4137 sulfhydrated HA-AKT-T308A/S473A, and HA-AKT-T308D/S473D to a similar extent as observed in neurons overexpressed with HA-AKT (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). These data suggest that both wild-type AKT and the phosphorylated AKT can be sulfhydrated.

Fig. 3.

Sulfhydration of total or phosphorylated AKT regulates phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 residue. (A) The modified biotin assay detects sulfhydration of total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH) in the brain lysates of AD patients compared to age-matched control brains. However, GSK3β was not sulfhydrated in the AD patients. (B) Administration of GYY4137 (300 μM) in primary neurons induces sulfhydration of HA-AKT-T308A/S473A and HA-AKT-T308D/S473D. (C) Sulfhydration of total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH) were found in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice by modified biotin switch assay. (D) Depletion of CBS after administration of CBS RNAi in PS19 mice blocks sulfhydration of total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH). (E) Depletion of CBS after administration of CBS RNAi blocks sulfhydration of total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH) in primary neurons treated with IL-1β (10 ng/mL). (F) Overexpression of hTau-P301L did not affect sulfhydration of total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH) after administration of IL-1β in primary neurons. (G) The schematic view shows that C77 resides within the PH domain of AKT which ranges from 5 to 107 amino acids. (H) The C59, C77A, C224, and C298 residues of AKT were mutated to alanine by site-directed mutagenesis. The HA-tagged mutants of AKT C59A, C77A, C224A, and C298A mutants were overexpressed in HEK293 cells and treated with GYY4137 (300 μM) and subjected to modified biotin switch assay. All of the AKT-mutants except for AKT C77 were sulfhydrated like wild-type AKT. (I) The red-maleimide assay (another method to detect sulfhydration of proteins) shows that AKT can be sulfhydrated at C77 residue in primary neurons treated with IL-1β. (J) The induction of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH was abolished in primary neurons overexpressed with HA-AKT-C77A and treated with IL-1β for 24 h. However, phosphorylation of AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P) or T308 (AKT-T308P) remains unaltered in cells overexpressed with either wild-type HA-AKT or HA-AKT-C77A mutant. (K) Overexpression of HA-AKT-C77A does not affect phosphorylation of AKT either at S473 (AKT-S473P) or T308 (AKT-T308P) but reduces phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β-S9-P) in HEK293 cells. (L) Overexpression of AKT-C77A rescues the interaction between AKT, AKT-S473P, or AKT-T308P and GSK3β after administration of GYY4137 (300 μM) in HEK293 cells. (M) In vitro kinase assay showed that AKT, AKT-S473P, or AKT-T308P immunoprecipitated from GYY4137-treated HEK293 cells was unable to phosphorylate GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β-S9-P); however, the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (GSK3β-S9-P) was rescued after overexpression of AKT-C77A mutant in HEK293 cells.

To further confirm these results, we analyzed the presence of AKT-SSH and AKT-P-SSH in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice. We found that the levels of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH were highly abundant in the cortex and hippocampus of PS19 mice (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). To determine the role of CBS and H2S in AKT sulfhydration, we depleted CBS and monitored AKT sulfhydration in PS19 mice. Consistent with our previous results, we found that AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH were decreased in CBS-depleted PS19 mice (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Consistent with these data, we found that depletion of CBS by RNAi in IL-1β–treated primary neurons abolished the formation of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3E). However, overexpression of hTau-P301L did not affect AKT sulfhydration in IL-1β–treated primary neurons (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Fig. S3F). This result suggests that hTau has no influence on the formation of AKT-S473P-SSH and AKT-T308P-SSH in a feed-forward mechanism.

In order to identify the Cys (C) residue responsible for AKT-SSH, we mutated four Cys residues within AKT and found that mutation of the C77 residue (Fig. 3G) to alanine (C77A) abolished the formation of AKT-SSH in HEK293 cells treated with GYY4137 (Fig. 3H and SI Appendix, Fig. S3G). The formation of AKT-SSH was further confirmed by the red maleimide assay. In this assay, Alexa Fluor 680 is conjugated to C2 maleimide (red maleimide), which selectively interacts with sulfhydryl groups of cysteines (Cs), thus labeling both sulfhydrated as well as unsulfhydrated Cs. However, treatment with DTT cleaves disulfide bonds, and thus the red signal from a sulfhydrated protein will be detached, but the red signal will be maintained on an unsulfhydrated protein. Thus, DTT treatment will result in decreased fluorescence of sulfhydrated proteins. The levels of protein sulfhydration were calculated as the residual red fluorescence intensity after DTT treatment divided by the total AKT level.

We employed the red maleimide assay in cells overexpressing either HA-AKT or HA-AKT-C77A. In cells overexpressing HA-AKT, we detected an intense red signal, which represented proteins with —SH as well as –SSH substituents. The intensity of this signal was reduced by >95% following DTT treatment, which indicated that HA-AKT was robustly sulfhydrated. In contrast, in cells overexpressing HA-AKT-C77A, no reduction in the red signal intensity was observed after DTT treatment, establishing that the putative sulfhydration of AKT was abolished by the C77A mutation (Fig. 3I and SI Appendix, Fig. S3H).

Similarly, overexpression of HA-AKT-C77A in IL-1β–treated primary neurons blocked the formation of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH (Fig. 3J and SI Appendix, Fig. S3I), as detected by the modified biotin switch assay. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of AKT was not affected by mutating the C77 residue of AKT (Fig. 3J), which suggested that sulfhydration is downstream of AKT phosphorylation. Similarly, we found that HA-AKT-C77A was phosphorylated to a similar extent as wild type AKT in GYY4137-treated HEK293 cells overexpressed with HA-AKT or HA-AKT-C77A (Fig. 3K and SI Appendix, Fig. S3J). However, overexpression of HA-AKT-C77A restores GSK3β phosphorylation compared to cells overexpressing wild type HA-AKT after treatment with GYY4137. These data suggest that sulfhydration does not directly influence AKT phosphorylation at S473 and T308.

In order to understand whether the sulfhydration of phosphorylated AKT has any influence on the interaction between GSK3β and AKT, we overexpressed HA-AKT or HA-AKT-C77A in GYY4137-treated HEK293 cells. We found that in HA-AKT-C77A–overexpressing cells, the interaction between phosphorylated AKT and GSK3β was detected along with an increase in the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 after treatment with GYY4137 (Fig. 3L and SI Appendix, Fig. S3K). These data suggest that sulfhydration of AKT blocks its interaction with GSK3β and subsequently affects the phosphorylation of GSK3β.

This was further confirmed by an in situ kinase activity assay. In this assay, both wild-type HA-AKT and the HA-AKT-C77A mutant were overexpressed in GYY4137-treated HEK293 cells, and AKT or phosphorylated AKT was immunoprecipitated from the cells followed by a kinase activity assay using GSK3β as the substrate. We found that phosphorylated AKT from HA-AKT–overexpressed untreated cells robustly phosphorylated GSK3β. However, phosphorylated AKT immunoprecipitated from AKT-C77A–overexpressing cells phosphorylated GSK3β irrespective of GYY4137 treatment (Fig. 3M and SI Appendix, Fig. S3L). These data confirm that sulfhydration of AKT phosphorylated at either S473 or T308 is a key posttranslational modification that reduces the phosphorylation of GSK3β in an H2S-dependent manner.

AKT Sulfhydration Was Abolished and GSK3β Phosphorylation Was Restored in a Transgenic AKT Knockin Mouse (AKT-KI+/+).

In order to determine whether AKT-C77A has any influence on the kinase activity of GSK3β in vivo, we generated a knockin mouse containing a mutated C77 residue in AKT that was substituted with alanine (AKT-C77A) using a modified version of the CRISPR-Cas9 technology (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). The generation of AKT-KI−/−, AKT-KI−/+, and AKT-KI+/+ mice was confirmed by genotyping (Fig. 4A). There were no gross differences between the AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice either from the dorsal, ventral, or lateral view, as well as brain size (Fig. 4B). The bodyweight of the AKT-KI+/+ mice increased with their age irrespective of the gender, and the increase was comparable to the AKT-KI−/− mice (Fig. 4C). In order to more fully examine the knockin mice, we analyzed the brain sections of AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice. We did not observe any remarkable differences in the cellular morphology or in the total number of cells in the brain sections of the cortex and hippocampus of AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice (Fig. 4D). In addition, there was no difference in the movement time and in the percentage of time spent in the center during the open-field test of AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice (Fig. 4 E and F). These data suggest that there is no difference in locomotor activity between AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice at the physiological level.

Fig. 4.

In AKT-KI+/+ mice, sulfhydration of AKT was prevented, and phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 was rescued along with an increase in interaction between AKT and GSK3β. (A) The representative DNA electrophoresis image of Sac-I digester PCR product from genomic DNA showing genotypic profile of −/− (wild-type), −/+ (heterozygous), and +/+(knockin) mice. (B) The dorsal view, ventral view, and lateral view of wild-type and AKT-KI 10-wk-old adult mice and the brain images. (C) The bodyweight of AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice from 9 to 16 wk of age. (D) The Cresyl violet staining of cortex and hippocampus of adult 12-wk-old AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice. (E and F) The total movement time (E) and percentage of time spent in the center (F) remain unaltered in AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice. One-way ANOVA measured statistical significance with a Tukey–Kramer post hoc correction, n = 10, *P < 0.05. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (G) Sulfhydration of total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH) was blocked in the cortex and hippocampus of AKT-KI+/+ mice after administration of IL1β. (H) Primary neurons isolated from AKT-KI+/+ mice were unable to sulfhydrate total AKT (AKT-SSH) or phosphorylated AKT at S473 (AKT-S473P-SSH) or T308 (AKT-T308P-SSH) after administration of IL-1β (10 ng) or GYY4137 (300 μM). (I) The interaction between total AKT, AKT-S473P, or AKT-T308P and GSK3β was restored in AKT-KI+/+ mice compared to AKT-KI−/− mice after administration of IL-1β in the cortex. (J) The reduction of GSK3β-S9-P was rescued after administration of IL-1β in the cortex of AKT-KI+/+ mice and it was measured by Western blot analysis. (K) The confocal analysis shows that GSK3β-S9-P was decreased in the cortex of IL-1β–treated AKT-KI−/− mice and it was rescued in IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice. One-way ANOVA measured statistical significance with a Tukey–Kramer post hoc correction, n = 7, *P < 0.05. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (Magnification: D, 20×; K, 40×.)

In order to determine whether AKT sulfhydration can be blocked in AKT-KI+/+ mice, we administered IL-1β to these mice. IL-1β induction does not occur in either AKT-KI+/+ or AKT-KI−/− mice under physiological conditions. Thus, to mimic the inflammatory state, we administered IL-1β to the mice. We found that administration of IL-1β to AKT-KI+/+ mice prevented the formation of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH in the cortex and hippocampus. However, AKT was not sulfhydrated at the physiological level in the absence of IL-1β treatment (Fig. 4G and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Similarly, we found that in primary neurons isolated from AKT-KI+/+ mice, the formation of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH was abolished after administration of either IL-1β or GYY4137 compared to AKT-KI−/− mice. However, the phosphorylation of AKT at either S473 (AKT-S473P) or T308 (AKT-T308P) remained unaltered in murine AKT-KI+/+ neurons compared to murine AKT-KI−/− neurons (Fig. 4H and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). These data suggest that IL-1β induced the formation of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH by elevating intracellular H2S levels. However, the formation of AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, and AKT-T308P-SSH can be blocked in AKT-KI+/+ mice.

Our data show that a reduction in AKT-SSH, AKT-S473P-SSH, or AKT-T308P-SSH rescued the interaction between GSK3β and AKT, AKT-S473P, or AKT-T308P in AKT-KI+/+ mice compared to AKT-KI−/− mice after treatment with IL-1β (Fig. 4I and SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). An increased interaction between phosphorylated AKT and GSK3β restored GSK3β phosphorylation at S9 in AKT-KI+/+ mice compared to AKT-KI−/− mice after administration of IL-1β (Fig. 4J and SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). This was further confirmed by confocal microscopy analysis, where the reduction in GSK3β phosphorylation at S9 was restored in AKT-KI+/+ mice following administration of IL-1β (Fig. 4K and SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). Taken together, our data show that GSK3β phosphorylation at S9 was restored in AKT-KI+/+ mice after IL-1β administration. Thus, it is important to understand whether blocking the formation of AKT-SSH in the PS19 brain can reduce Tau phosphorylation.

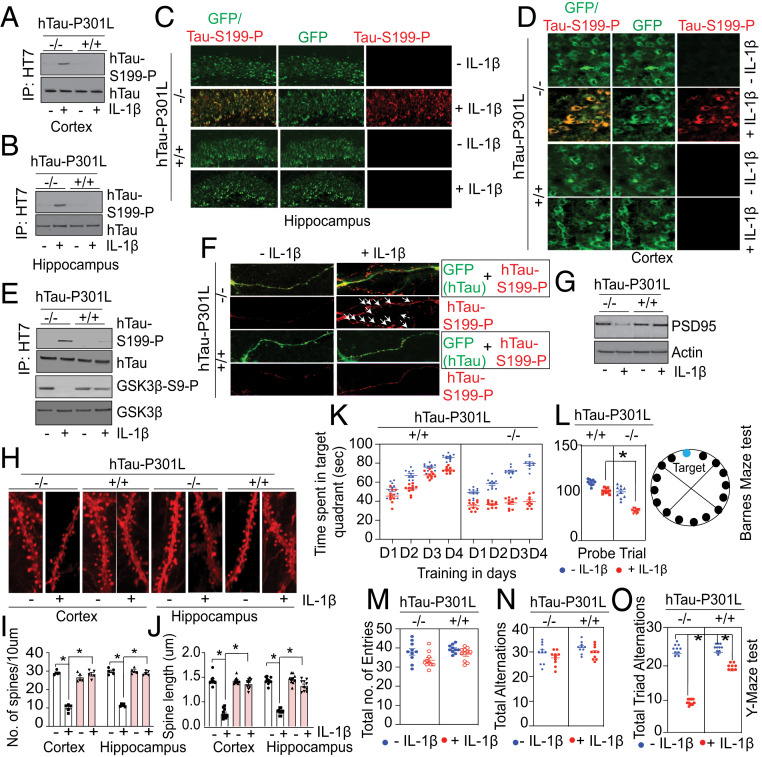

IL-1β–Treated AKT-KI+/+ Mice Overexpressing hTau-P301L Have Reduced hTau Phosphorylation Levels That Prevent the Loss of Dendritic Spines and Improve Memory Functions.

We attempted to generate a homozygous PS19+/+:Akt-KI+/+ mice colony to test the influence of AKT-SSH on Tau phosphorylation in PS19 mice. Unfortunately, we found that establishing a homozygous PS19+/+:AKT-KI+/+ mice colony was unfeasible because female PS19+/+:AKT-KI+/+ mice were infertile like the female PS19+/+ mice. However, we studied heterozygous PS19+/−:AKT-KI+/− mice to elucidate the role of AKT sulfhydration in Tau phosphorylation. We found that Tau phosphorylation was reduced in PS19+/−:AKT-KI+/− mice compared to PS19+/−:AKT-KI−/− mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) and the PS19+/−:AKT-KI+/− mice showed improvement in spatial memory functions, which was determined by a Y-maze study. In this test, the total number of arm entries (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), total alternations, and the number of total triad alternations are calculated. The total number of arm entries (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B) and total alternations (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C) are almost similar between PS19+/−:AKT-KI−/− mice and PS19+/−:AKT-KI+/− mice. This indicates that there were no major differences in motor functions of AKT-KI+/+ and AKT-KI−/− mice. However, total triad alternations (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D) in the Y-maze was significantly reduced in PS19+/−:AKT-KI−/− mice compared to PS19+/−:AKT-KI+/− mice. These data suggest that blocking AKT sulfhydration improved memory functions in PS19 mice.

These encouraging data prompted us to determine whether homozygous AKT-KI+/+ mice fully block Tau phosphorylation and restore cognitive functions. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed hTau-P301L in the brains of both AKT-KI−/− and AKT-KI+/+ mice followed by administration of IL-1β. As GSK3β activation was compromised in IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice, we tested whether hTau was phosphorylated at S199 in the cortex and hippocampus of AKT-KI−/− and Akt-KI+/+ mice after administration of IL-1β. We found that hTau phosphorylation was increased at S199 in the murine AKT-KI−/− cortex and hippocampus after administration of IL-1β. However, hTau phosphorylation at S199 was blocked in AKT-KI+/+ mice after administration of IL-1β (Fig. 5 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5E). These results were further confirmed by confocal microscopic analysis, which showed that hTau S199 phosphorylation was decreased in the hippocampus (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5F) and cortex (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5G) of hTau-P301L–overexpressing IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice compared to hTau-P301L–overexpressing IL-1β–treated AKT-KI−/− mice. To further confirm these results, we isolated primary neurons from AKT-KI+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L, followed by IL-1β treatment of the neurons. Next, we monitored hTau phosphorylation at S199. Consistent with our in vivo results, we found that the phosphorylation of hTau at S199 was blocked in AKT-KI+/+ neurons compared to AKT-KI−/− neurons in association with an increase in GSK3β phosphorylation (Fig. 5E and SI Appendix, Fig. S5H).

Fig. 5.

In AKT-KI+/+ mice, the synaptic integrity and cognitive dysfunction were restored compared to AKT-KI−/− mice after administration of IL-1β. (A and B) Compared to AKT-KI−/− mice, the induction of hTau-S199 phosphorylation was restored in the cortex (A) and hippocampus (B) of AKT-KI+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L, after administration of IL-1β (10 ng) in the cortex. (C and D) The confocal analysis shows that the hTau-S199 phosphorylation was decreased in the hippocampus (C) and cortex (D) of AKT-KI+/+ compared to AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L after administration of IL-1β. (E) Compared to AKT-KI−/− neurons, the induction of hTau-S199 phosphorylation was restored in AKT-KI+/+ neurons overexpressed with hTau-P301L, after administration of IL-1β (10 ng). (F) Confocal microscopic studies show that the level of hTau-S199 phosphorylation in spines was reduced in AKT-KI+/+ neurons overexpressed with hTau-P301L after administration of IL-1β (10 ng). (G) Western blot analysis shows that PSD95 was decreased in AKT-KI−/− mice but rescued in AKT-KI+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L after administration of IL-1β. (H) Confocal microscopic analysis shows that the loss of synaptic puncta as shown by DiI staining in the cortex and hippocampus was rescued in AKT-KI+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L after administration of IL-1β. (I and J) The loss in the number of spines per 10 μm of dendrites (I) and loss in spine length (μm) of dendrites (J), were rescued in the cortex and hippocampus of AKT-KI+/+ mice compared to AKT-KI−/− mice after administration of IL1β. (K and L) the time spent in the target quadrant was improved IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L compared to AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L during 4 d of training (K) and the day of probe trial (L) in the Barnes maze test. A representative image of The Barnes maze was presented where the target hole was colored as blue while the other holes are shown in black color. (M–O) The total number of entries (M), total alternations (N), and the total number of triad alternations (O) were determined in the Y-maze test. The total number of entries, alternations were unaltered among AKT-KI+/+ mice or AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L treated with or without IL-1β. However, the total number of triad alternations was rescued in IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice overexpressing hTau-P301L compared to IL-1β–treated AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L. One-way ANOVA measured statistical significance with a Tukey–Kramer post hoc correction, n = 10, *P < 0.05. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The arrowheads in F indicate the dendritic spines. (Magnification: C, 20×; D, 40; F and H, 60×.)

Since Tau phosphorylation at synapses significantly reduced the number of dendritic spines (43), we monitored the percentage of hTau-S199-P in the spines of neurons isolated from AKT-KI+/+ and AKT-KI−/− mice. We found that the percentage of hTau-S199-P+ spines was decreased in IL-1β–treated neurons isolated from AKT-KI+/+ mice (Fig. 5F and SI Appendix, Fig. S5I). The spine loss was further confirmed by monitoring the expression level of a postsynaptic protein, PSD95. We found that the reduced expression level of PSD95 in AKT-KI−/− mice was rescued in AKT-KI+/+ mice after administration of IL-1β (Fig. 5G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5J). The morphologic assessment of spines using DiI staining of AKT-KI+/+ mice revealed a loss of several spines in the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 5 H and I) that was rescued in AKT-KI+/+ mice after administration of IL-1β. Similarly, the decrease in spine length in the hippocampus (Fig. 5 H and J) of AKT-KI−/− mice were restored in AKT-KI+/+ mice.

Accumulation of hTau-S199-P in spines leads to synaptic dysfunctions, which is the most common underlying mechanism of memory impairment in AD (44). We subjected both AKT-KI+/+ and AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L to the Y-maze and Barnes maze tests to monitor spatial learning and memory functions after administration of IL-1β. In the Barnes maze test, mice are placed in the middle of a large elevated circle, which has 19 mock holes and 1 target hole, and the time spent in the target quadrant is measured. The target quadrant is defined as the area containing the target hole and two more holes left and right side of the target hole. This is conducted for 4 training days. On the fifth day, the escape hole is blocked and the time spent in the target quadrant are measured. We found that the time spent in the target quadrant was increased for AKT-KI+/+–overexpressing hTau-P301L treated with or without IL-1β during the training period of 4 d (Fig. 5K). However, the time spent in the target quadrant was not improved in AKT-KI−/−–overexpressing hTau-P301L mice treated with IL-1β compared to untreated AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L (Fig. 5K). On the day of the probe test, IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+–overexpressing hTau-P301L (Fig. 5L) mice spent more time in the target quadrant, compared to IL-1β–treated AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L (Fig. 5L). These data suggest that the memory function of AKT-KI−/− mice overexpressing hTau-P301L was impaired after administration of IL-1β. However, the memory function was rescued in AKT-KI+/+ mice under similar experimental conditions.

Consistent with the Barnes maze test, we found that the total number of triad alternations in the Y-maze was reduced significantly in hTau-P301L–overexpressing IL-1β–treated AKT-KI−/− mice compared to hTau-P301L–overexpressing IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice (Fig. 5O). This result suggests that AKT-KI+/+ mice attenuate cognitive dysfunction. However, the total number of arm entries (Fig. 5M) and total alternations (Fig. 1N) was altered between hTau-P301L–overexpressing IL-1β–treated AKT-KI−/− mice and hTau-P301L–overexpressing IL-1β–treated AKT-KI+/+ mice. This indicates that there were no major differences in motor functions of AKT-KI+/+ and AKT-KI−/− mice. Overall, our data suggest that blocking AKT sulfhydration is essential to improving memory functions of mice overexpressing hTau-P301L under neuroinflammatory conditions.

In order to test whether the impairment of cognitive functions is also mediated by neuronal loss other than spine loss, we monitored neuronal loss as a characteristic feature of atrophy or neurodegeneration in hTau-P301L–overexpressing AKT-KI+/+ mice and AKT-KI−/− mice. We found that overexpression of hTau-P301L did not induce neuronal loss after a month of overexpression (SI Appendix, Fig. S5K). Our results are consistent with a previous study, which showed that PS19 mice developed neuronal loss and brain atrophy by 8 to 9 mo (37) despite cognitive impairment that was observed within 5 mo (45, 46).

Discussion

In the present study, we provide compelling evidence that AKT-P-SSH is critical for the activation of the protein kinase, GSK3β, which in turn, augments the phosphorylation of hTau. Our study also reveals that the interaction between phosphorylated AKT and GSK3β suppresses the activation of GSK3β. Sulfhydration of phosphorylated AKT prevents the formation of the AKT–GSK3β complex and the unbound unphosphorylated GSK3β becomes free to phosphorylate Tau at S199 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5L). All of these events can be reversed in transgenic mice that block AKT sulfhydration.

The functional relevance of AKT in AD remains multifactorial (47, 48). Importantly, AKT plays a vital role in influencing the hyperphosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein, Tau (49, 50), through GSK3β phosphorylation. Inactivation of AKT has been shown to augment hTau hyperphosphorylation (50). However, the underlying mechanism for inactivation of AKT remains unknown. Previously, it was shown that in AD patient samples, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) down-regulates the activation of AKT by decreasing its phosphorylation via inhibiting its localization to the plasma membrane (51–54). However, we show that sulfhydration of phosphorylated AKT (AKT-S473P-SSH or AKT-T308P-SSH) is the primary contributor to GSK3β activation and it is possible that it functions independent of the PTEN-mediated reduction in AKT phosphorylation. In addition, the detection of AKT-P-SSH in AD patient samples and transgenic AD mice models, along with its correlation with hTau phosphorylation at S199, further strengthens the evidence that AKT-S473P-SSH or AKT-T308P-SSH is critical in AD pathology.

Previously, dysregulation of H2S homeostasis was implicated in the pathological processes of AD. Studies show that H2S prevents neuronal impairment in an experimental model of AD (55). However, no studies have provided genetic evidence indicating whether a lack of H2S exaggerated the neuropathology of AD. In addition, these studies were unable to provide direct evidence whether intracellular H2S was down-regulated in AD. Our study contributes to these critical gaps in the field and establish that augmentation of H2S plays an important role in the synaptic dysfunction in AD. In support of this conclusion, we provide compelling evidence using heterogeneous transgenic CBS mice and transgenic AKT-KI+/+ mice. As part of the mechanism, we found that AKT sulfhydration is critical for AD pathology, including Tau phosphorylation, which can be reversed in transgenic mice (AKT-KI+/+ mice) that block AKT sulfhydration. Sulfhydration of proteins is prevalent, and several proteins have been identified that are sulfhydrated either under physiological or pathological conditions (34, 35, 56). Importantly, we found that AKT was not sulfhydrated under physiological conditions. However, AKT can be sulfhydrated under inflammatory conditions, which are present in all of the neurodegenerative disorders, including AD, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis (57, 58). The investigation of the functional relevance of sulfhydrated AKT in AKT-KI+/+ mice provides a unique opportunity to revisit the influence of AKT-P-SSH in the manifestation of these neurological disorders.

A substantial number of studies have shown that AKT is the major kinase that regulates the activation of GSK3β. Other than AKT, the activation of other kinases, such as PKC or PKA, also contributes to the phosphorylation of GSK3β at S9 (59, 60). Since GSK3β phosphorylation is down-regulated in the AD brain, PKA or PKC may also play a role in the down-regulation of GSK3β phosphorylation. GSK3β phosphorylation is dependent on the intracellular H2S levels, and the interaction between phosphorylated AKT and GSK3β was robustly increased in the PS19 brain after depletion of H2S. Thus, we mainly focused on the influence of AKT on GSK3β phosphorylation. We provide direct evidence that blocking AKT sulfhydration in AKT-KI+/+ mice rescued GSK3β phosphorylation. These data further confirm that AKT is the major kinase that regulates GSK3β phosphorylation.

Previously, it was shown that Tau phosphorylation was independent of amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation in the AD brain (61–63). However, the underlying mechanism was not fully elucidated. We provide evidence that proinflammatory cytokines can induce Tau phosphorylation before induction of Aβ in the AD brain (64, 65). On the other hand, Aβ and IL-1β always function in a positive feedback loop. Thus, it is possible that induction of Aβ will further increase the sulfhydration of phosphorylated AKT and Tau phosphorylation through activation of GSK3β in an IL-1β–dependent manner.

Although the aggregation of hTau at the late phase of tauopathy has been associated with neuronal loss and brain atrophy (9–11), the early hyperphosphorylation of hTau, specifically at S199, has a unique importance in synaptic dysfunction in AD patients. Aberrant hTau phosphorylation at the early stage of AD induces its mislocalization to dendritic spines and affects its stability (6–8). In addition, early phosphorylation of hTau serves as a precursor for hTau aggregation, which is a standard feature of tauopathy (62, 66). Thus, targeting early phosphorylation of hTau could be an effective strategy to reduce tauopathy. Our study provides direct evidence that sulfhydration of phosphorylated AKT is responsible for hTau hyperphosphorylation. In addition, we show that the loss of dendritic spines was rescued in AKT-KI+/+ mice, which resulted in an improvement in cognitive function. Thus, targeting sulfhydration of phosphorylated AKT provides a novel opportunity to address tauopathy in AD. In the future, we will study whether blocking AKT sulfhydration reduces brain atrophy and neuronal loss. Furthermore, tauopathy has been implicated in other neurological disorders other than AD (67). Thus, the identification of AKT sulfhydration may provide insights into other tauopathy-associated neurological disorders.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. The Akt-KI+/+ mouse colony was generated using the using the transgenic core facility of the University of Pittsburgh. The PS19 mouse line was purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. We used homozygous PS19+/+ males to carry out breeding with Akt-KI+/+ female mice to generate PS19+/−:Akt-KI+/− mice. The details of generation of AKT-KI+/+, the maintenance and breeding of PS19 mice and PS19+/−:Akt-KI+/− mice are detailed in S1 Appendix. Details of materials and methods, including in vivo overexpression of mutant Tau construct and administration of IL-1β in the brain, cortical neuron culture, site-specific mutagenesis, transfection in HEK293 cells and primary neurons, immunocytochemical and immunohistochemical staining, maleimide assay, coimmunoprecipitation, modified biotin switch assay for sulfhydration, quantitative real-time PCR, ELISA detection of hydrogen sulfide, agarose gel electrophoresis for the separation of DNA Western blotting, and neurobehavioral tests like Y-maze test, Barnes maze test, open-field test, DiI stain, and spine evaluation are described in SI Appendix. The quantification of each image present in the main figures is also incorporated in SI Appendix.

Statistical Analysis.

The biochemical studies, Western blot, coimmunoprecipitation, ELISA, RT-PCR, confocal analysis, the Sholl analysis, and all behavioral tests were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons were performed using the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test (P < 0.05) unless noted otherwise. Mean values were calculated for each biochemical experiment (n = 7) and each behavioral experiment (n = 10), and all of the data were depicted as the mean ± SEM.

Data Availability.

All data are available in the manuscript and SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sebastien Gingras (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Immunology) for the design of the targeting strategy; as well as Dr. Chunming Bi and Zhaohui Kou of the Transgenic and Gene Targeting Core (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Immunology) for the microinjection of zygotes and the production of mutant mice. This work was partly supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01NS094516 and R01EY025622 (to N.S.) and by grants from the University of Pittsburgh and Copeland Foundation (to T.S. and N.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1916895117/-/DCSupplemental.

Change History

October 11, 2021: Figure 2 has been updated; please see accompanying Correction for details.

References

- 1.Gold C. A., Budson A. E., Memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for development of therapeutics. Expert Rev. Neurother. 8, 1879–1891 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarawneh R., Holtzman D. M., The clinical problem of symptomatic Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006148 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulving E., Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 1–25 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankar G. M., Walsh D. M., Alzheimer’s disease: Synaptic dysfunction and Abeta. Mol. Neurodegener. 4, 48 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsh J., Alifragis P., Synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: The effects of amyloid beta on synaptic vesicle dynamics as a novel target for therapeutic intervention. Neural Regen. Res. 13, 616–623 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurage C. A., Sergeant N., Ruchoux M. M., Hauw J. J., Delacourte A., Phosphorylated serine 199 of microtubule-associated protein tau is a neuronal epitope abundantly expressed in youth and an early marker of tau pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 105, 89–97 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luna-Muñoz J., Chávez-Macías L., García-Sierra F., Mena R., Earliest stages of tau conformational changes are related to the appearance of a sequence of specific phospho-dependent tau epitopes in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 12, 365–375 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertrand J., Plouffe V., Sénéchal P., Leclerc N., The pattern of human tau phosphorylation is the result of priming and feedback events in primary hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 168, 323–334 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger Z., et al., Accumulation of pathological tau species and memory loss in a conditional model of tauopathy. J. Neurosci. 27, 3650–3662 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alonso Adel. C., Mederlyova A., Novak M., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Promotion of hyperphosphorylation by frontotemporal dementia tau mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34873–34881 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song J. S., Yang S. D., Tau protein kinase I/GSK-3 beta/kinase FA in heparin phosphorylates tau on Ser199, Thr231, Ser235, Ser262, Ser369, and Ser400 sites phosphorylated in Alzheimer disease brain. J. Protein Chem. 14, 95–105 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai Z., Zhao Y., Zhao B., Roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3 in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 9, 864–879 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong C. X., Iqbal K., Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau: A promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 2321–2328 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee V. M., Brunden K. R., Hutton M., Trojanowski J. Q., Developing therapeutic approaches to tau, selected kinases, and related neuronal protein targets. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1, a006437 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim J., Lu K. P., Pinning down phosphorylated tau and tauopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1739, 311–322 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma T., GSK3 in Alzheimer’s disease: Mind the isoforms. J. Alzheimers Dis. 39, 707–710 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanger D. P., Noble W., Functional implications of glycogen synthase kinase-3-mediated tau phosphorylation. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 352805 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takashima A., GSK-3 is essential in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 9 (suppl. 3), 309–317 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spittaels K., et al., Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta phosphorylates protein tau and rescues the axonopathy in the central nervous system of human four-repeat tau transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 41340–41349 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manning B. D., Toker A., AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating the network. Cell 169, 381–405 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kremer A., Louis J. V., Jaworski T., Van Leuven F., GSK3 and Alzheimer’s disease: Facts and fiction…. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4, 17 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A., Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378, 785–789 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alessi D. R., Caudwell F. B., Andjelkovic M., Hemmings B. A., Cohen P., Molecular basis for the substrate specificity of protein kinase B; comparison with MAPKAP kinase-1 and p70 S6 kinase. FEBS Lett. 399, 333–338 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rickle A., et al., Akt activity in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Neuroreport 15, 955–959 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pei J. J., et al., Role of protein kinase B in Alzheimer’s neurofibrillary pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 105, 381–392 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pei J. J., et al., Distribution of active glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK-3beta) in brains staged for Alzheimer disease neurofibrillary changes. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 1010–1019 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avila J., et al., Tau phosphorylation by GSK3 in different conditions. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 578373 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hooper C., Killick R., Lovestone S., The GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 104, 1433–1439 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubio-Perez J. M., Morillas-Ruiz J. M., A review: Inflammatory process in Alzheimer’s disease, role of cytokines. ScientificWorldJournal 2012, 756357 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swardfager W., et al., A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 930–941 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C., Cui G., Zhu M., Kang X., Guo H., Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Chemokines produced by astrocytes and chemokine receptors. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7, 8342–8355 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brosseron F., Krauthausen M., Kummer M., Heneka M. T., Body fluid cytokine levels in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A comparative overview. Mol. Neurobiol. 50, 534–544 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimura A., Yoshikura N., Hayashi Y., Inuzuka T., Cerebrospinal fluid C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 correlates with brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 61, 581–588 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mir S., Sen T., Sen N., Cytokine-induced GAPDH sulfhydration affects PSD95 degradation and memory. Mol. Cell 56, 786–795 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paul B. D., Snyder S. H., H2S signalling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 499–507 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mustafa A. K., et al., H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci. Signal. 2, ra72 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshiyama Y., et al., Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 53, 337–351 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopperton K. E., Mohammad D., Trépanier M. O., Giuliano V., Bazinet R. P., Markers of microglia in post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 177–198 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X., Quan N., Microglia and CNS interleukin-1: Beyond immunological concepts. Front. Neurol. 9, 8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cantley L. C., The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296, 1655–1657 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vivanco I., Sawyers C. L., The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 489–501 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang S., et al., Reducing the levels of Akt activation by PDK1 knock-in mutation protects neuronal cultures against synthetic amyloid-beta peptides. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 435 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kandimalla R., Manczak M., Yin X., Wang R., Reddy P. H., Hippocampal phosphorylated tau induced cognitive decline, dendritic spine loss and mitochondrial abnormalities in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 30–40 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di J., et al., Abnormal tau induces cognitive impairment through two different mechanisms: Synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. Sci. Rep. 6, 20833 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeuchi H., et al., P301S mutant human tau transgenic mice manifest early symptoms of human tauopathies with dementia and altered sensorimotor gating. PLoS One 6, e21050 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lasagna-Reeves C. A., et al., Reduction of Nuak1 decreases tau and reverses phenotypes in a tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 92, 407–418 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffin R. J., et al., Activation of Akt/PKB, increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates and loss and altered distribution of Akt and PTEN are features of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J. Neurochem. 93, 105–117 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanabria-Castro A., Alvarado-Echeverría I., Monge-Bonilla C., Molecular pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: An update. Ann. Neurosci. 24, 46–54 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li C., Götz J., Tau-based therapies in neurodegeneration: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 863–883 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoothoff W. H., Johnson G. V., Tau phosphorylation: Physiological and pathological consequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1739, 280–297 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Georgescu M. M., PTEN tumor suppressor network in PI3K-Akt pathway control. Genes Cancer 1, 1170–1177 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frere S., Slutsky I., Targeting PTEN interactions for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 416–418 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knafo S., et al., PTEN recruitment controls synaptic and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s models. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 443–453 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kreis P., Leondaritis G., Lieberam I., Eickholt B. J., Subcellular targeting and dynamic regulation of PTEN: Implications for neuronal cells and neurological disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7, 23 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei H. J., Li X., Tang X. Q., Therapeutic benefits of H2S in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 21, 1665–1669 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sen N., Functional and molecular insights of hydrogen sulfide signaling and protein sulfhydration. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 543–561 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gelders G., Baekelandt V., Van der Perren A., Linking neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 4784268 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ransohoff R. M., How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 353, 777–783 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaidanovich-Beilin O., Woodgett J. R., GSK-3: Functional insights from cell biology and animal models. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4, 40 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fang X., et al., Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11960–11965 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kametani F., Hasegawa M., Reconsideration of amyloid hypothesis and tau hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 12, 25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saha P., Sen N., Tauopathy: A common mechanism for neurodegeneration and brain aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 178, 72–79 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rajmohan R., Reddy P. H., Amyloid-beta and phosphorylated tau accumulations cause abnormalities at synapses of Alzheimer’s disease neurons. J. Alzheimers Dis. 57, 975–999 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kinney J. W., et al., Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (N. Y.) 4, 575–590 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alasmari F., Alshammari M. A., Alasmari A. F., Alanazi W. A., Alhazzani K., Neuroinflammatory cytokines induce amyloid beta neurotoxicity through modulating amyloid precursor protein levels/metabolism. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 3087475 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kolarova M., García-Sierra F., Bartos A., Ricny J., Ripova D., Structure and pathology of tau protein in Alzheimer disease. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 731526 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee V. M., Goedert M., Trojanowski J. Q., Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1121–1159 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript and SI Appendix.