Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Cognitive reserve (CR) predicts delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and faster post-diagnosis decline. The net impact of CR, combining both pre- and post- diagnosis risk, on adverse AD-related outcomes is unknown. We adopted a novel approach, using AD genetic risk scores (AD-GRS), to evaluate this.

METHODS:

Using 242,959 UK Biobank participants age 56+, we evaluated whether CR (operationalized as education) modified associations between AD-GRS and mortality or hospitalization (total count, fall-related, and urinary tract infection (UTI)-related).

RESULTS:

AD-GRS predicted mortality and hospitalization outcomes. Education did not modify AD-GRS effects on mortality, but had a non-significantly (interaction P=0.10) worse effect on hospitalizations due to UTI or falls among low education (OR=1.07 [95% CI: 1.02, 1.12]) than high education (OR=1.01 [0.95, 1.07]) individuals.

DISCUSSION:

Education did not convey differential survival advantages to individuals with higher genetic risk of AD, but may reduce hospitalization risk associated with AD genetic risk.

Keywords: Cognitive reserve, education, genetic risk score, mortality, hospitalization, UTIs, falls

Search Terms: Alzheimer’s disease, Cognitive aging, genetic risk

1. Introduction

Dementia has numerous adverse clinical consequences, including higher risk of mortality, falls[1], [2], urinary tract infections (UTIs)[3], and overall hospitalization[4], [5]. The direct cause of these adverse outcomes is rarely due to increased brain pathology, but rather conditions that develop due to lowered cognitive performance and function [6], [7]. Factors that may influence cognitive status and function, like Cognitive Reserve (CR), could in theory have a benefit for hospitalization risk and mortality.

Cognitive Reserve (CR) is conceptualized as the capacity to maintain high cognitive performance despite neural damage due to dementia-related disease processes and is invoked to explain variability in cognitive performance among individuals with similar burden of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology. Key empirical results guiding the interpretation of CR are that (1) people with high CR develop AD on average at a later age and (2) such individuals experience faster functional declines after diagnosis of dementia, including shorter time to death[8]–[13]. Most conceptualizations of CR interpret these results to imply CR provides meaningful improvements in the lives of people at risk of dementia. An alternative interpretation, however, is that CR improves performance on the cognitive tests used to diagnose dementia, without conveying meaningful benefits for cognitive function used in daily life to promote health and functioning.

Although the benefit of CR for improving test scores is established, it is surprisingly still unknown whether CR conveys meaningful delays in the overall course of AD beyond delaying diagnosis. If CR is associated with meaningful cognitive advantages, it may protect against adverse dementia-related outcomes such as premature mortality, falls, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and overall hospitalization. Although individuals with high CR average shorter time from diagnosis to death, this result does not imply that CR has no net mortality advantage when considering time living with the disease both before and after diagnosis. Understanding whether CR is providing meaningful advantages to true cognitive function or whether it is merely conveying an advantage in cognitive test scores that does not translate to other outcomes, such as hospitalization and mortality, could shine a light on the role of CR on the course of AD.

Evaluating the net impact of CR is challenging because diagnostic criteria for AD may be less sensitive to disease among people with high CR. The net impact of CR on hospitalization and mortality associated with AD cannot be directly evaluated using dementia-related hospitalization or dementia-related mortality, due to the potential for missed diagnoses of AD in people with high CR. Nor is it possible to evaluate the net impact of CR on AD mortality and hospitalization using all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization because most measures of CR have benefits for many other causes of these outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease, for reasons entirely unrelated to AD[14], [15].

AD genetic risk scores (AD-GRS) provide a novel approach to evaluating the net effects of CR. AD-GRS predicts cognitive function[16] , memory decline[17], elevated risk of clinical AD[18] , age-specific risk for AD[19], and post-mortem pathological diagnosis of AD[20] . While the effect of AD-GRS on mortality appears primarily mediated by cognition and overall functional status, with no evidence for pleiotropic paths[21], the effect of AD-GRS on hospitalization has not been established. Focusing on individuals with high AD-GRS allows us to differentially identify outcomes related to dementia in a way that is not influenced by timing of diagnosis. If cognitive reserve provides meaningful delays in mortality related to AD, we would expect it to delay mortality related to genetic risk of AD (Figure 1); a similar argument can be made for reduction in hospitalizations related to cognitive function.

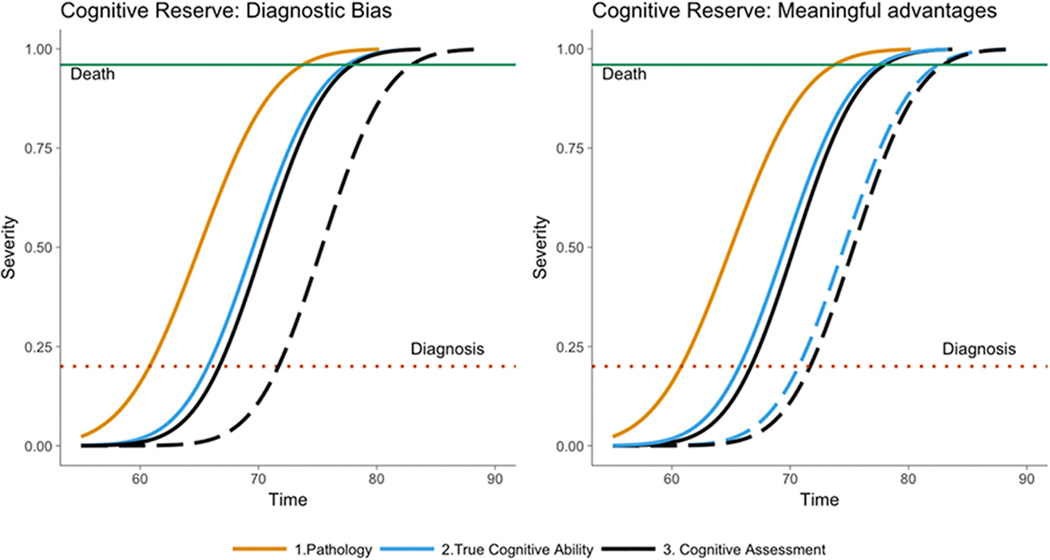

Figure 1: Alternative Hypotheses for How Cognitive Reserve Relates to Mortality.

In the figures below, solid curves represent Pathology (yellow), True Cognitive Ability (blue) and Cognitive Assessment (black). Dementia or AD diagnosis occurs when True Cognitive Ability reaches a certain severity (red dotted line). Death occurs when True Cognitive Ability reaches a certain severity (green line). Dashed curves represent the impact of cognitive reserve on Cognitive Assessment and/or True Cognitive Ability. The left panel displays cognitive reserve as diagnostic bias – in this scenario the Cognitive Assessment curve is shifted forward, meaning cognitive reserve delays age of diagnosis, but no meaningful changes in True Cognitive Ability or age at death occurs. The right panel displays cognitive reserve as having a meaningful protective effect on True Cognitive Ability and age at death.

We therefore hypothesized that CR, measured as educational attainment, reduces the negative impact of high AD-GRS on all-cause mortality, overall number of hospitalizations, hospitalization due to falls, and hospitalizations due to UTIs. With regards to hospitalization outcomes, we focused on causes of hospitalization (falls and UTIs) known to be elevated among individuals with dementia. We used data from the UK Biobank, a large cohort of middle-aged and older adults to test these hypotheses.

2. Methods:

2.1. Study population

The UK Biobank is an ongoing cohort study previously described in detail[22]. Briefly, participants were enrolled in the UK Biobank from 2007–2010, from 21 assessment centers across England, Wales, and Scotland. Consenting participants visited their closest assessment center and provided baseline information, physical measures, and biological samples. Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Service National Research Ethics Service and all participants provided written informed consent.

We restricted to UK Biobank participants age 56+, because there is little evidence that the AD-GRS predicts cognition in younger individuals. From 291,468 UK Biobank participants age 56 or older, we excluded those with missing or poor genetic information based on UK Biobank quality control checks (n = 8,557). We further excluded those who were not genetically classified as of European ancestry (n = 37,160), due to the known risk of confounding in genetic analyses due to population stratification. We also excluded those with missing or not-reported education level (n= 2,792), and 1 participant with inconsistent death information, leaving an analytic sample of 242,958 participants.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Genotyping and Genetic Risk Scores for AD

Genotyping:

UK Biobank genotyping was conducted by Affymetrix using a bespoke BiLEVE Axiom array for ∼50,000 participants and the remaining ∼450,000 on the Affymetrix UK Biobank Axiom array [23], [24]. To calculate genetic risk scores, we used summary results on 26 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) from independent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [25],[26][19], [27], [28]. Appendix A contains detailed information on genotyping and calculation of genetic risk scores.

2.2.2. All-Cause Mortality and Dementia-Related Mortality

Follow-up for all deaths (from national death registers) began at enrollment into the UK Biobank study and ended on March 15, 2016. The underlying cause of death was determined from the death certificate International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) code. For our cause-specific mortality analyses, we distinguished between dementia-related mortality and mortality from all other causes (non-dementia-related mortality). Because of the potential for misclassification of dementia-related deaths, we used an inclusive definition, defining deaths with ICD-10 codes in categories F01-F99 (Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental disorders) or G00-G99 (Diseases of the nervous system) as dementia related. This definition is unlikely to capture all of the individuals who were experiencing symptoms or difficulties due to dementia prior to their deaths, but is an imperfect proxy for the mortality burden related to dementia.

2.2.3. Hospitalization

The hospital diagnosis coding in the UK Biobank is based on the ICD-10 codes captured from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data. Records date back to April 1997 and contain coded data on admissions, operations and procedures. In order to appear in the HES dataset, patients must have been admitted to the hospital after April 1997 and had relevant coding recorded in the patient administrative record. We considered three separate hospitalization outcomes; 1. Total in-patient hospitalizations (offset by observed years), hospitalization due to UTI and hospitalization due to falls. For hospitalization due to UTI, we used ICD 10 code N39.0, for hospitalization due to falls, we used the Fall block of the ICD 10 codes, W00-W19. Hospitalizations under Chapter XV of the ICD 10 codes, Pregnancy, Childbirth and puerperium, were excluded from the total in-patient hospitalizations. We also considered a combined outcome of hospitalization related to falls and a hospitalization related to UTI.

2.2.3. Cognitive Reserve

For this analysis, we classified education into two categories: high education (a college/university degree; A levels/AS levels or equivalent examinations; or other professional qualifications, e.g. nursing, teaching) vs low education (O levels/GCSEs/CSEs or equivalent examinations; a national vocational qualification (NVQ), higher national diploma (HND), or Higher National Certificate (HNC); or no educational qualifications). This dichotomization corresponds roughly to 1997 International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) level 3A completion[29]: upper secondary education which enables access to subsequent schooling.

2.2.4. Cognitive Function

To confirm the association between genetic risk and cognitive function, we used the composite UK Biobank cognitive test score assessing verbal-numerical reasoning, described elsewhere[30]. This is an unweighted sum of the number of correct answers given to 13 verbal or numerical logic or reasoning questions within a two-minute time limit. We confirmed that this measure has an approximately normal distribution and is lower among older adults, as expected[31].

2.2.5. Covariates

We controlled for age at first assessment, chromosomally indicated sex and genetic ancestry via the first four PCs provided by UK Biobank for this purpose.

2.3. Analytic plan

To confirm the validity of our AD-GRS, we first estimated the association between AD-GRS and cognitive function at baseline (with a linear model) and longitudinally (with a linear mixed effect model with random intercepts and slopes). We also confirmed that the AD-GRS affected our outcomes, as evidence that outcomes were more common among people with AD (whether or not diagnosed). We then assessed our primary hypotheses that CR reduced the effects of AD-GRS on our outcomes: mortality; hospitalization due to UTI; hospitalization due to falls; hospitalizations due to UTI and falls; and total number of hospitalizations. To assess mortality, we used Cox proportional hazards models, using age as the timescale. To assess hospitalizations due to UTI and hospitalizations due to falls, we used logistic regression models with a binary (0/1) outcome, where a 1 indicated the participant had been hospitalized with the outcome specific ICD 10 codes. Finally, to assess total number of hospitalizations, we used a Poisson regression model, with an offset for total years observed since April 1997. We first estimated the association of AD-GRS with each outcome. We compared the estimated effect of the AD-GRS on each outcome with and without adjustment for education to confirm education was not mediating AD-GRS effects. For our primary hypothesis tests, we compared the estimated effect of the AD-GRS measure on each outcome among individuals with higher education versus individuals with lower education and used interaction terms to test whether effects were significantly different between high and low education individuals. Analyses of the combined outcome of hospitalization for either UTI or falls was post-hoc.

3. Results

Of 242,958 participants, 9,705 (4%) died over a follow-up period up to 10 years (average=7.58 years). Hospital records indicated that most (69%) had been hospitalized at least once, but only a small fraction (5%) had been hospitalized due to falls, or UTIs (4%; Table 1). AD-GRS was higher in those who died (compared to those censored), in those who died from dementia related causes, compared to other causesl and in those who were hospitalized at least once, due to a fall, or due to a UTI (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the UK Biobank included in the analyses.

| Died |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at the End of Follow-Up | Died During Follow-Up | Total | Dementia related death | Other Cause of Death | |

| N (%) | 233,253 (96%) | 9,705 (4%) | 242,958 | 552 (6%) | 9,153 (94%) |

| Baseline Age, mean (SD) | 62.5 (3.8) | 63.9 (3.8) | 62.51 (3.8) | 64.4 (3.6) | 63.84 (3.8) |

| Years of follow up, median (SD) | 7.67 (0.86) | 4.89 (2.03) | 7.58 (1.1) | 5.65 (1.86) | 4.84 (2.03) |

| Female N (%) | 125,413 (54%) | 3,653 (38%) | 129,066 (53%) | 209 (38%) | 3,444 (38%) |

| APOE-e4, N (%) | 60,724 (26%) | 2641 (27%) | 63,365 (26%) | 204 (37%) | 2,437 (27%) |

| AD GRS, mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.40) | 0.05 (0.41) | 0.04 (.40) | 0.16 (0.47) | 0.04 (0.41) |

| AD GRS without APOE-e4, mean (SD) | −0.14 (0.17) | −0.14 (0.18) | −0.14 (0.17) | −0.12 (0.18) | −0.14 (0.17) |

| Verbal Numeric Reasoning, mean (SD) | 6.09 (2.07) | 5.73 (2.05) | 6.07 (2.07) | 5.08 (2.06) | 5.75 (2.05) |

| High education, N (%) | 101,869(44%) | 3,460 (36%) | 105,329 (43%) | 213 (39%) | 3,347 (35%) |

| Any Hospitalization | 159,511 (68%) | 8,145 (84%) | 167,656 (69%) | 466 (84%) | 7679 (84%) |

| Hospitalization due to falls | 11,147 (5%) | 1,004 (10%) | 12,151 (5%) | 105 (19%) | 1004 (10%) |

| Hospitalization due to UTIs | 7,658 (3%) | 1,462 (15%) | 9,120 (4%) | 150 (27%) | 1462 (15%) |

Confirmation of the AD-GRS effect on cognition:

AD-GRS was associated with both baseline cognitive function and cognitive decline, as expected. On average, verbal-numerical reasoning was about 0.025 SD units (95% CI:−0.04,−0.009) lower at first assessment and was different an average of 0.10 SD units (95% CI:−0.11,−0.04) faster per decade, for every one point higher AD-GRS.

3.1. AD-GRS, CR, and Mortality

All-Cause Mortality

Each unit higher value of the AD-GRS predicted a 7% higher all-cause mortality hazard (HR = 1.07, CI:1.02,1.13) and this estimate was unchanged when education was included as a covariate, although low education was significantly associated with all-cause mortality (HRLow Education=1.28, CI:1.23,1.34) (Table 2). The interaction between education and AD-GRS on mortality was not statistically significant (p-interaction=0.19), and the interaction point estimates were unexpectedly consistent with the possibility that a high AD-GRS has a greater impact on those with high CR compared to those with low CR (HRAD-GRS among the high education group=1.12, CI: (1.03,1.22), HRAD-GRS among the low education group:=1.05 (0.99,1.11).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios for the association of AD Genetic Risk Score (AD GRS) with all-cause, dementia-related and non-dementia related mortality.

| All- Cause Mortality | Dementia-Related Mortality | Non-Dementia Related Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | |||

| AD-GRS | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 1.99 (1.66,2.39) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.08) |

| Model 2 | |||

| AD-GRS | 1.07 (1.02,1.13) | 1.99 (1.66,2.40) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.08) |

| Low Education | 1.28 (1.23, 1.34) | 1.08 (0.91, 1.29) | 1.29 (1.24, 1.35) |

| Model 3 | |||

| AD-GRS | 1.12 (1.03,1.22) | 2.02 (1.50,2.71) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) |

| Low Education | 1.29 (1.21, 1.34) | 1.08 (0.90, 1.30) | 1.30 (1.25, 1.35) |

| AD-GRS by Low Education Interaction | 0.93 (0.84, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.67, 1.44) | 0.94 (0.84, 1.04) |

| AD-GRS Effect Estimates Among High and Low Education Groups, Estimated from Model 3 | |||

| AD-GRS in High Education | 1.12 (1.03,1.22) | 2.02 (1.50,2.71) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) |

| AD-GRS in Low Education | 1.05 (0.99,1.11) | 1.98 (1.56,2.51) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.07) |

| Pinteraction | 0.19 | 0.63 | 0.21 |

Cause-Specific Mortality

Higher AD-GRS increased risk of dementia-related mortality (HR = 1.99, CI:1.66,2.39) and this estimate remained essentially unchanged when education was included as a covariate in the model (Table 2). Lower education level was not a significant predictor of dementia-related mortality (HR = 1.08, CI:0.91,1.29) and did not significantly modify the effect of the AD-GRS on dementia-related mortality (p-interaction=0.63). The HRAD-GRS among the high education group was 2.02, CI: (1.50,2.71) while the HRAD-GRS among the low education group was 1.98 (1.56,2.51), AD-GRS was not a significant predictor of non-dementia-related death in either unadjusted or education adjusted models (HR=1.03, CI: 0.97,1.08), however lower education (HR=1.29, CI: 1.24, 1.35 was a strong predictor of non-dementia-related death. Education did not significantly modify the effect of the AD-GRS on non-dementia-related mortality (HRAD-GRS among the high education group=1.07, CI:(0.98,1.17), HRAD-GRS among the low education group=1.01 (0.95,1.08), p-interaction = 0.21).

3.2. AD-GRS, CR, and Hospitalization

Hospitalization Visit Rate

Higher AD-GRS slightly increased the risk of hospitalization (Incidence Rate Ratio [IRR] = 1.01, CI: 1.01, 1.02) and this estimate remained essentially unchanged when education was included as a covariate in the model (Table 4). Lower education level significantly increased the rate of hospitalization (IRR=1.25, CI: 1.24, 1.26) but did not significantly modify the effect of the AD-GRS on rate of hospitalization (p-interaction = 0.42). The IRR due to AD-GRS among the high education group was 1.008, CI: (0.998,1.02) while the IRR due to AD-GRS among the low education group was 1.013 (1.01,1.02).

Table 4.

Association of AD Genetic Risk Score (AD GRS) with Hospitalizations (rate), Hospitalization due to falls, Hospitalization due to UTIs.

| Hospitalization | Hospitalization-Falls | Hospitalization-UTIs | Hospitalization-Falls or UTIs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR(95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| AD-GRS | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 1.06 (1.01,1.10) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) |

| Model 2 | ||||

| AD-GRS | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 1.06 (1.01,1.10) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) |

| Low Education | 1.25 (1.24, 1.26) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.33 (1.27, 1.39) | 1.20 (1.16,1.24) |

| Model 3 | ||||

| AD-GRS | 1.01 (0.999–1.02) | 1.01 (.94, 1.09) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) | 1.01 (0.95,1.07) |

| Low Education | 1.25 (1.24, 1.26) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.33 (1.27, 1.39) | 1.20 (1.16,1.23) |

| AD-GRS by Low Education Interaction | 1.01 (0.992–1.02) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.8) | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) | 1.07 (0.99,1.14) |

| AD-GRS Effect Estimates Among High and Low Education Groups, Estimated from Model 3 | ||||

| AD-GRS in High Education | 1.008 (0.999–1.02) | 1.01 (.94, 1.09) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) | 1.01 (0.95,1.07) |

| AD-GRS in Low Education | 1.013 (1.01,1.02) | 1.08 (1.02,1.15) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) |

| Pinteraction | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

Hospitalization due to falls, UTIs

Higher AD-GRS increased the odds of a hospitalization due to a fall (OR = 1.06, CI: 1.01, 1.10) and hospitalization due to a UTI (OR = 1.04, CI: 1.00, 1.10). These estimates remained essentially unchanged when education was included as a covariate in the model (Table 4). Lower education level significantly increased the odds of a hospitalization due to a fall (OR = 1.15, CI: 1.10, 1.18), and due to a UTI (OR = 1.33, CI: 1.27, 1.39). Though interaction was not statistically significant for either outcome (falls, UTIs, p-interaction=0.14,.18), the effect of the AD-GRS on hospitalization due to a fall among people in the high education group was close to null (ORAD-GRS among higher educated=1.01, CI: (0.94,1.09)), while the effect among people with low education was harmful, (ORAD-GRS among the low educated group: 1.08 (1.02,1.15)); a similar pattern was seen with UTIs.

Hospitalization due to falls or UTI

In light of suggestive but potentially underpowered results for hospitalization due to falls and hospitalization due to UTI, we also considered a pooled outcome of hospitalization for either falls or UTI. Higher AD-GRS increased the odds of a hospitalization due to a UTI or fall (OR = 1.04, CI: 1.01, 1.08) and this estimate remained essentially unchanged when education was included as a covariate in the model (Table 4). Lower education level significantly increased the odds of a hospitalization due to a UTI or fall (OR = 1.20, CI: 1.16, 1.24). The effect of the AD-GRS on the pooled hospitalization outcome among people with high education, ORAD-GRS = 1.01, CI: (0.95,1.07), was close to null, while the effect among people with low education was harmful, ORAD-GRS = 1.07 (1.02,1.12), and the interaction p-value = 0.10.

3.3. AD-GRS without APOE

Our subsequent analyses explored the effect of the AD-GRS without APOE ε4 by removing the two SNPs along chromosome 19 that are used to characterize APOE status (rs429358, rs7412), Tables 3,5. With respect to mortality, results for our primary hypothesis were similar, although the AD-GRS is a much weaker predictor of mortality without APOE ε4 , Table 3. The AD-GRS without APOE ε4 was not associated with all-cause mortality (HR = 1.00, CI: 0.89, 1.12), but was a significant predictor of dementia-related mortality (HR = 1.67, CI: 1.03, 2.70). Education did not significantly modify the effect of the AD-GRS without APOE ε4 on dementia-related mortality ((HRHigh Ed:1.57, CI: (0.73, 3.40), HRLow Ed: 1.74 (0.94, 3.22), p-interaction = 0.84). With respect to hospitalization outcomes, results were relatively consistent between the two different genetic risk scores (AD-GRS with and without APOE ε4) Table 5. We found evidence that education modified the effect of the AD GRS without APOE ε4 on hospitalization incidence risk ratio (IRR for hospitalization due to ADGRS among the high education group was 0.99, CI: (0.97,1.02) while the IRR due to AD-GRS among the low education group was 1.05 (1.03,1.07), p-interaction = 0.001. Stronger modifying effects of education on hospitalization due to falls and UTIs were also found; for UTI related visits, ORAD-GRS among the high education group was 0.99, CI: (0.82,1.21), and ORAD-GRS among the low education group of 1.17 (1.00,1.36), p-interaction = 0.20 , for fall related visits, ORAD-GRS among the high education group was 0.99, CI: (0.86,1.53), and ORAD-GRS among the low education group was 1.12 (0.97,1.28), p-interaction = 0.18. In the pooled analysis, we found a stronger modifying effect of education on hospitalization due to a fall or UTI, ORAD-GRS among the high education group was 0.95, CI: (0.83,1.09), and ORAD-GRS among the low education group of 1.15 (1.04,1.28), p-interaction = 0.03.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for the association of AD Genetic Risk Score Calculated Without APOE-e4 (AD-GRSnoAPOE) with all-cause, dementia-related and non-dementia related mortality.

| All- Cause Mortality | Dementia-Related Mortality | Non Dementia- Related- Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | |||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE | 1.00 (0.89,1.12) | 1.67 (1.03,2.70) | 0.97 (0.86,1.09) |

| Model 2 | |||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE | 1.00 (0.90,1.13) | 1.67 (1.03,2.70) | 0.97 (0.87,1.10) |

| Low Education | 1.29 (1.21, 1.31) | 1.08 (0.91, 1.28) | 1.29 (1.24, 1.35) |

| Model 3 | |||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE | 0.98 (0.81,1.19) | 1.57 (0.73,3.40) | 0.95 (0.78,1.16) |

| Low Education | 1.29 (1.22, 1.36) | 1.10 (0.88, 1.35) | 1.30 (1.23, 1.37) |

| AD-GRSnoAPOE by Low Education Interaction | 1.03 (0.81, 1.31) | 1.11 (0.41, 2.95) | 1.03 (0.81,1.32) |

| AD-GRSnoAPOE Effect Estimates Among High and Low Education Groups, Estimated from Model 3 | |||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE in High Education | 1.03 (0.81, 1.31) | 1.57 (0.73,3.40) | 0.95 (0.78,1.16) |

| AD-GRSnoAPOE in Low Education | 1.02 (0.88,1.17) | 1.74 (0.94,3.22) | 0.98 (0.85,1.14) |

| Pinteraction | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.90 |

Table 5.

Association of AD Genetic Risk Score AD Genetic Risk Score Calculated Without APOE-e4 (AD-GRSnoAPOE) with Hospitalizations (rate), Hospitalization due to falls, Hospitalization due to UTIs.

| Hospitalization | Hospitalization-Falls | Hospitalization-UTIs | Hospitalization-Falls or UTIs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR(95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE | 1.03 (1.01,1.05) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.17) | 1.10 (0.98,1.24) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) |

| Model 2 | ||||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE | 1.03 (1.01,1.05) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.17) | 1.10 (0.98,1.24) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) |

| Low Education | 1.25 (1.24, 1.26) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.33 (1.27, 1.39) | 1.21 (1.18,1.25) |

| Model 3 | ||||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE | 0.997 (0.97,1.02) | 0.97 (0.81,1.14) | 0.99 (0.82,1.21) | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) |

| Low Education | 1.26 (1.25, 1.27) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.123) | 1.36 (1.29, 1.44) | 1.24 (1.20,1.29) |

| AD-GRSnoAPOE by Low Education Interaction | 1.05 (1.02, 1.09) | 1.16 (0.93, 1.44) | 1.17 (0.91,1.50) | 1.21 (1.02,1.44) |

| AD-GRSnoAPOE Effect Estimates Among High and Low Education Groups, Estimated from Model 3 | ||||

| AD-GRSnoAPOE in High Education | 0.996 (0.972,1.02) | 0.997 (0.86,1.53) | 0.99 (0.82,1.21) | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) |

| AD-GRSnoAPOE in Low Education | 1.05 (1.03,1.07) | 1.12 (0.97,1.28) | 1.17 (1.00,1.36) | 1.15 (1.04, 1.28) |

| Pinteraction | 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.03 |

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether education, a common proxy measure of CR, reduces four adverse outcomes commonly associated with AD (premature mortality, rate of hospitalization, hospitalization due to a fall, hospitalization due to UTI) by examining the extent to which education reduced effects of AD-GRS on each outcome. We found no evidence that education level reduced mortality due to AD-GRS, although the AD-GRS predicted higher all-cause and dementia-related mortality risk. Education level predicted all-cause mortality and death from causes unrelated to dementia, but not dementia-related mortality. We found some evidence that education level reduced overall hospitalization rate due to AD-GRS as well as hospitalization due to falls and due to UTIs. We found this result in the AD-GRS both with and without APOE ε4. While formal tests for interaction indicated the differences in risk for hospitalization could plausibly be attributed to chance, there was a consistent pattern of results. Given the suggestive evidence found in the hospitalization outcomes, we performed a post-hoc analysis that pooled together the two cause-specific hospitalization ICD 10 codes (falls and UTIs). We found stronger and significant evidence that education modified the effect of AD-GRS on this pooled outcome. Further analyses that considered additional hospitalization outcomes and includes longer follow-up in an older sample, could improve precision and develop a more complete picture of a phenotype.

We used an indirect approach to evaluate the influence of CR on adverse outcomes of AD, to overcome a fundamental challenge in evaluating the net impact of CR on the burden of AD. The timing of AD diagnosis is imprecise and diagnostic measures may be less sensitive for people with high CR. The imprecision of clinical tests and potential misdiagnoses of AD could result in delayed diagnosis and shortened time from diagnosis to death even if CR conveyed no meaningful advantage. All-cause mortality and hospitalizations due to falls or UTIs, on the other hand, are arguably health events with less potential for diagnostic bias. The impact of AD-GRS on all-cause mortality or hospitalization in older adulthood is likely to operate primarily through increased dementia risk [1], [3], [21] . Evaluating whether CR offsets the impact of AD-GRS on mortality or hospitalization gives us insight into the relation between CR and mortality or hospitalization burden of AD.

Our results did not suggest education reduced the impact of AD-GRS on all-cause mortality. Contrary to our hypothesis, the interaction point estimates were more consistent with the possibility that those with more education were less protected from mortality burden of AD compared to those with lower levels of education. With respect to hospitalization outcomes, we found suggestive evidence that education protected against the effects of the AD-GRS, i.e., the effect of the AD-GRS was in general non-significantly worse for individuals with low levels of education compared to those with high levels of education. Patterns were similar for all three hospitalization outcomes (overall rate, visit due to fall, visit due to UTI). This finding provides some evidence towards the hypothesis that CR provides meaningful benefits to individuals at higher genetic risk for dementia by reducing adverse outcomes resulting in excess hospitalization.

APOE ε4 provides the largest effect estimate in the total AD-GRS score, but is also associated with mortality from non-dementia causes, especially earlier in life[32]. To assess whether our results were completely driven by APOE, we removed the two SNPs that characterize APOE ε4 in the genome. After removing these SNPs from the total AD-GRS we were able to confirm the association between genetic risk for AD and increased dementia-related mortality, overall hospitalization rate, as well as hospitalization due to falls and hospitalization due to UTIs. This implies there is information in the AD-GRS outside of APOE status that is important in predicting dementia-related deaths and hospitalizations. With this modified GRS, we found evidence that CR moderated the effect of the GRS hospitalization outcomes, in addition to the pooled outcome. We found no evidence that CR moderated the effect of the GRS on all-cause mortality or dementia related mortality.

This study has several strengths. Most importantly, we use a conceptually novel approach to shed new light on the meaning and importance of CR. The large sample size and high quality genetic data in the UK Biobank allows for powerful and robust testing. Finally, to our knowledge, this is the first study to establish an association between AD genetic risk and hospitalizations due to falls and UTIs (as well as overall hospitalization rate). An important limitation of this study is that the UK Biobank averaged less than 8 years of follow-up data. Both self-reported education and cause-specific mortality and hospitalization data may be misreported. The UK Biobank is not a representative sample and we restricted these analyses to individuals classified as having Caucasian genetic ancestry. Results may differ in a more diverse or less highly selected sample[22]. It would also be valuable to explore this with a stronger AD-GRS, for example a genome-wide score, as polymorphisms included in the AD-GRS represent only a portion of the full genetic background of AD. The most important limitation is our inability to evaluate a broader range of dementia related outcomes. Mortality and hospitalization are two outcomes of importance to patients, however many other domains, including independence in activities of daily living, quality of life, and meaningful social participation, are all adversely affected by dementia and may be influenced by CR. Our approach can be fielded in other cohorts with good longitudinal measures of these outcomes.

To date, measures of CR are among the most promising indicators of protection from AD and other neurodegenerative pathologies. Our understanding of the overall impact of CR on the course and burden of AD has been limited and interpretation of the basic empirical findings about CR remains uncertain. One avenue by which CR may be reducing AD burden is through a compression of morbidity. In other words, individuals with higher CR experience clinical dementia for a shorter period of time. Empirical evidence tends to support this as those with higher CR are diagnosed at later ages and often have faster decline and higher mortality post-diagnosis. However, a meaningful measurement of morbidity in dementia is very difficult. The challenge here is that this relies on the assumption that performance on neuropsychological tests used for diagnosis of AD is an ideal assessment of morbidity in older adults. Although it can be argued that everyone below a severe cut-point on neuropsychological tests might have dementia, individuals with dementia still have varying degrees of test taking skills and education may enhance test taking skills without conferring any useful improvement in cognition. Our use of hospitalization outcomes was an attempt at disentangling compression of morbidity with diagnostic bias. Our evidence was suggestive but not conclusive. Future work that hones-in on additional outcomes related to dementia, could clarify the extent to which CR benefits those at highest risk for dementia.

Our analysis provides a novel approach to evaluating the net impact of CR on adverse outcomes associated with AD: mortality, hospitalization rate, falls, and UTIs. Although our results should be replicated in a more diverse sample, additional outcomes, and with longer-follow-up, they provide a template for additional work. Although we find no benefit of CR for mortality, we find suggestive evidence that CR reduces hospitalizations due to dementia.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A novel approach to evaluating the net impacts of cognitive reserve (CR) on adverse dementia related outcomes, based on genetic risk scores.

CR, conceptualized as education, did not convey differential mortality advantages.

Results for whether CR conveyed differential advantages for hospitalizations related to dementia were suggestive but not conclusive.

Results suggest possible benefit of education for overall clinical consequences of diagnosed or undiagnosed AD.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institute on Aging grants K99AG053410 (Mayeda), R01AG051170 (Filshtein, Jones, Glymour), T32AG049663 (Brenowitz)

Footnotes

Author Disclosures:

Teresa Filshtein: No disclosures

Willa Brenowitz: No disclosures

Elizabeth Rose Mayeda: No disclosures

Timothy Hohman: No disclosures

Stefan Walter: No disclosures

Rich N. Jones: No disclosures

Fanny Elahi: No disclosures

M. Maria Glymour: No disclosures

Contributor Information

Teresa Jenica Filshtein, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco.

Willa D. Brenowitz, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco.

Elizabeth Rose Mayeda, Department of Epidemiology, University of California, Los Angeles Fielding School of Public Health.

Timothy J. Hohman, Vanderbilt Memory & Alzheimer’s Center, Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN.

Stefan Walter, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco and Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid, Spain.

Rich N. Jones, Department of Neurology, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Fanny M. Elahi, Memory and Aging Center, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco.

M. Maria Glymour, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- [1].Muir SW, Gopaul K, and Montero Odasso MM, “The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Age and Ageing. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Welmerink DB, Longstreth WT, Lyles MF, and Fitzpatrick AL, “Cognition and the risk of hospitalization for serious falls in the elderly: Results from the cardiovascular health study,” Journals Gerontol. - Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Caljouw MAA, den Elzen WPJ, Cools HJM, and Gussekloo J, “Predictive factors of urinary tract infections among the oldest old in the general population. A population-based prospective follow-up study.,” BMC Med., 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chodosh J et al. , “Cognitive decline in high-functioning older persons is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization,” J. Am. Geriatr. Soc, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shah FA et al. , “Bidirectional relationship between cognitive function and pneumonia,” Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beard MC, Kokmen E, Sigler C, Smith GE, Petterson T, and O’Brien PC, “Cause of death in Alzheimer’s disease,” Ann. Epidemiol, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 195–200, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brunnström HR and Englund EM, “Cause of death in patients with dementia disorders,” Eur. J. Neurol, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stern Y, “Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease,” Lancet Neurol., vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 1006–1012, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Scarmeas N, Albert SM, Manly JJ, and Stern Y, “Education and rates of cognitive decline in incident Alzheimer’s disease,” J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, vol. 77, pp. 308–316, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Valenzuela M, Brayne C, Sachdev P, Wilcock G, and Matthews F, “Cognitive Lifestyle and Long-Term Risk of Dementia and Survival After Diagnosis in a Multicenter Population-based Cohort,” Am. J. Epidemiol, vol. 173, no. 9, pp. 1004–1012, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Osone A, Arai R, Hakamada R, and Shimoda K, “Impact of cognitive reserve on the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease in Japan,” Geriratrics Gerontol. Int, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 428–434, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ojagbemi A, Bello T, and Gureje O, “Cognitive Reserve, Incident Dementia, and Associated Mortality in the Ibadan Study of Ageing,” J Am Geriatr Soc., vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 590–595, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bruandet A et al. , “Cognitive decline and survival in Alzheimer’s disease according to education level,” Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 74–80, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cohen AK and Syme SL, “Education: A Missed Opportunity for Public Health Intervention,” Am J Public Heal., vol. 103, no. 6, pp. 997–1001, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kubota Y and et al. , “Educational Attainment and Lifetime Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study,” Forthcom. JAMA-Internal Med., 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fawns-Ritchie C et al. , “Polygenic Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Neurodegenerative Related Traits and their Association with Cognitive Function: UK Biobank and the Dementias Platform UK,” Alzheimer’s Dement., vol. 12, no. 7, p. 179, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marden JR et al. , “Using an Alzheimer’s Disease polygenic risk score to predict memory decline in black and white Americans over 14 years of follow-up Running head: AD polygenic risk score predicting memory decline,” Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 195–202, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Escott-Price V et al. , “Common polygenic variation enhances risk prediction for Alzheimer’s disease.,” Brain, vol. 138, no. 12, pp. 3673–3684, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Desikan RS et al. , “Genetic assessment of age-associated Alzheimer disease risk: Development and validation of a polygenic hazard score,” PLoS, vol. 14, no. 3, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Escott-Price V, Myers AJ, Huentelman M, and Hardy J, “Polygenic risk score analysis of pathologically confirmed Alzheimer disease,” Ann. Neurol, vol. 82, pp. 311–314, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mez J et al. , “Alzheimer’s disease genetic risk variants beyond APOE ε4 predict mortality,” Alzheimer’s Dement., vol. 8, pp. 188–195, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sudlow C et al. , “UK Biobank: An Open Access Resource for Identifying the Causes of a Wide Range of Complex Diseases of Middle and Old Age,” PLoS Med., vol. 12, no. 3, p. e1001779, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].UK Biobank, “biobank; Genetic Data,” 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/scientists-3/genetic-data. [Accessed: 31-Mar-2018].

- [24].UK Biobank, “Genotyping and quality control of UK Biobank, a large-scale, extensively phenotyped prospective resource,” 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2014/04/UKBiobank_genotyping_QC_documentation-web.pdf. [Accessed: 31-Mar-2018].

- [25].Lambert J, Ibrahim-Verbaas C, Harold D, and Al E., “Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease.,” Nat. Genet, vol. 45, no. 12, pp. 1452–1458, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].de Lille IP, “Vivre Mieux, Plus Longtemps.” [Online]. Available: https://www.pasteurlille.fr/5/home/. [Accessed: 31-Mar-2018].

- [27].Ruiz A et al. , “Assessing the role of the TREM2 p.R47H variant as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia.,” Neurobiol. Aging, vol. 35, no. 2, p. 444 e1–4, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van der Lee SJ et al. , “The effect of APOE and other common genetic variants on the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: a community-based cohort study,” Lancet Neurol., 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].U. I. for Statistics, “International Standard Classification of Education,” 2018. [Online]. Available: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/united_kingdom_isced_mapping_0.xls. [Accessed: 31-Mar-2018].

- [30].UK Biobank, “Fluid intelligence score - Data-Field 20016.” [Online]. Available: http://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/field.cgi?id=20016. [Accessed: 31-Mar-2018].

- [31].Lyall M et al. , “Cognitive Test Scores in UK Biobank: Data Reduction in 480,416 Participants and Longitudinal Stability in 20,346 Participants.,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 4, p. e0154222, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rajan KB et al. , “Racial Differences in the Association Between Apolipoprotein E Risk Alleles and Overall and Total Cardiovascular Mortality Over 18 Years,” J. Am. Geriatr. Soc, vol. 65, no. 11, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.