Abstract

Background

The GEMINI trials established the efficacy of vedolizumab in moderate-to-severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and demonstrated a favorable safety profile, suggesting it may be advantageous in older patients at greater risk of treatment-related complications. However, there is a paucity of data exploring the outcomes of vedolizumab in this group. Our objective was to determine the clinical effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in older IBD patients within a real-world multicenter UK cohort.

Methods

A retrospective review of electronic records across 6 UK hospitals was undertaken to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and safety outcomes of vedolizumab in IBD patients aged ≥60 at start of therapy. Rates of clinical response, remission and corticosteroid-free remission were assessed at weeks 14 and 52, using validated clinical indices, and were compared to historical controls from real-world vedolizumab-treated cohorts unstratified by age.

Results

Of 74 patients aged 60 years or above (median 66 years), 48 were included in our effectiveness analysis (29 ulcerative colitis, 19 Crohn’s disease). Rates of clinical response, remission and corticosteroid-free remission at week 14 were 64%, 48% and 30%, respectively. By week 52, the rates of clinical response, remission, and corticosteroid-free remission were 52%, 38%, and 32%, respectively. Six (8%) patients experienced adverse effects. Effectiveness and safety outcomes were comparable to those of age-unstratified vedolizumab-treated cohorts.

Conclusion

Our 1-year outcome data suggests that vedolizumab is safe and effective in older IBD patients and broadly comparable to cohorts unselected by age.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, vedolizumab, older onset IBD

Introduction

The incidence of older onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), typically defined as onset >60 years of age, is 10-15% [1] and rising, with one Dutch population-based study reporting a 2-fold increase in incidence between 1991 and 2011 [2]. The majority of cases are diagnosed between 60-70 years, 25% between 70-80 years, and 10% over 80 years [3,4]. Several studies have highlighted differences in the disease trajectory of these patients compared with the younger population [5,6], with a suggestion that the natural history is less aggressive [6-9]. For example perianal and fistulizing disease occur less frequently in older onset IBD patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) [7]. Up to 30% of IBD patients are over 60 years old [8], and given the aging population and the small impact of IBD on mortality, the prevalence of IBD among the elderly is expected to increase.

Therapeutic options are theoretically the same in older and younger patients, but there are gaps in our understanding of the specific needs of the older group. Older patients are either excluded from or under-represented in clinical trials, hampering insights into the safety and efficacy of therapy as a function of age. Additional considerations that influence the optimal management strategy in this group include polypharmacy, multiple comorbidities, functional status and, crucially, adverse effects of therapy secondary to infection and malignancy. Safety data have consistently shown that advanced age is an independent risk factor for serious adverse events and death in patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) medications [9,10], rendering older patients more likely to discontinue therapy [9,11]. In a Belgian retrospective study with 743 anti-TNF-treated patients, older age at first infusion was the only predictor of death (P<0.01) [12]. Older age is also an independent risk factor for lymphoproliferative disorders in thiopurine-treated patients; their incidence increases to more than 5-fold in the 50-65 age group, and even more in the >65 group [13].

In terms of efficacy of biologic agents, older patients have lower rates of short-term clinical response to anti-TNF therapy compared to younger patients, even after adjustment for confounding factors, although once an initial response is achieved they have a comparable long-term clinical response [9]. A similar pattern is observed from the rheumatology experience, which is based on larger patient numbers and longer follow-up data [14].

The advent of vedolizumab, a gut-selective humanised monoclonal antibody targeting the a4b7 integrin expressed by gut-homing lymphocytes, represents an important advance in IBD therapy. The GEMINI trials demonstrated the clinical efficacy of vedolizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in moderate-to-severe active ulcerative colitis (UC) and CD, with a safety profile comparable to that of placebo [15,16]. Integrated safety data, from 2830 patients followed over 5 years, confirmed that vedolizumab was not associated with an increased risk of infection or malignancy. Moreover, infusion-related reactions, enteric infections and autoimmune events occurred infrequently [17]. Similarly, in a 4-year post-marketing safety analysis based on 208,050 patient years of vedolizumab exposure, the rates of gastrointestinal and infection-related adverse events were comparable between patients aged ≥70 years and those <70 years [18].

Clinical and safety outcomes have been corroborated in observational studies of “real-world” practice [4,17,19-25]. The gut-selective mechanism of action of vedolizumab is an especially attractive property in high-risk groups such as those with advanced age, or a history of malignancy or immunosuppression. However, there is a relative paucity of data in these groups. Yajnik et al conducted a post hoc analysis of the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in GEMINI trial patients stratified by age, of whom 230 (130 UC, 90 CD) were in the >55 years group and 56 patients were aged >65 years. Efficacy (induction and maintenance) and safety profiles between vedolizumab and placebo were similar in all age groups, with no age-related differences in the incidence of malignancy or death [26]. Whilst these outcomes are promising, there are challenges in extrapolating data from clinical trials, given that they are highly selective and often exclude patients with significant comorbidities prevalent in the older population. We therefore aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in older IBD patients in a multicenter UK cohort.

Patients and methods

This study included patients from 6 UK hospitals: Guy’s and St. Thomas’, King’s College, St. Mark’s, The Royal London, Addenbrooke’s, and The John Radcliffe. Older age was defined as ≥60 years. A retrospective review of electronic records was performed to identify patients who started vedolizumab between January 2015 and 2018. Inclusion criteria were age ≥60 and the availability of at least 12 months of follow-up data (irrespectively of whether vedolizumab was continued). Exclusion criteria for the clinical effectiveness analysis included clinically inactive disease at baseline, as defined using validated clinical indices—Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) for CD (HBI<5) or the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) for UC (SCCAI<3)—missing baseline activity score data, and the presence of a stoma.

Data collection was performed using a standardized form. Extracted data included demographics, baseline disease characteristics (subtype, disease duration, phenotype according to the Montreal classification for CD, history of surgery), baseline disease activity, history of malignancy, prior anti-TNF exposure, and concomitant immunomodulation. Patients with unclassified IBD were included in the UC group for analysis.

Effectiveness and safety data were extracted at week 14 and week 52. Effectiveness measures were clinical response (reduction in HBI or SCCAI scores by ≥3 points), clinical remission (HBI<5 or SCCAI<3) and corticosteroid-free remission (HBI<5 or SCCAI<3 without concomitant steroids) [27,28]. An intention-to-treat strategy was used. Safety data included any adverse events. Where relevant, time to discontinuation of therapy was also collated alongside reasons for discontinuation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize differences in demographic and baseline characteristics among study groups. Continuous variables are presented as median and categorical variables are expressed as proportions. Data are presented to the nearest significant figure. The comparator groups were patients from previously published studies describing real-world, observational experience of vedolizumab unstratified by age, identified via a structured PubMed and Embase search.

Results

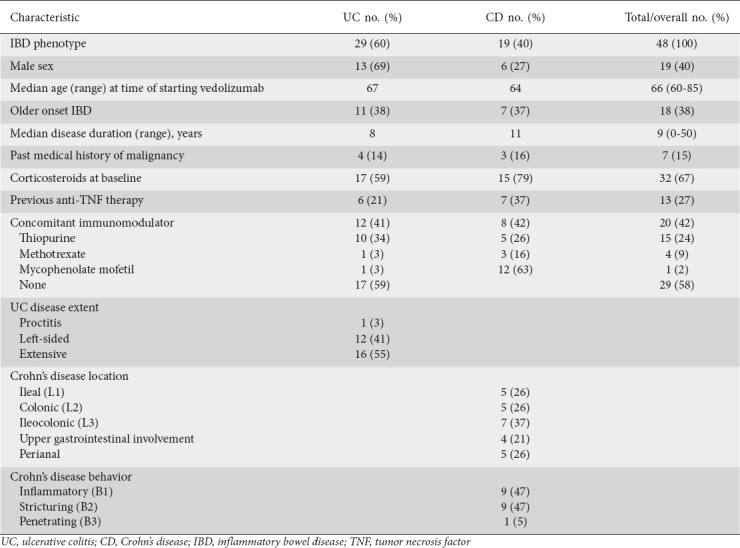

Patient characteristics

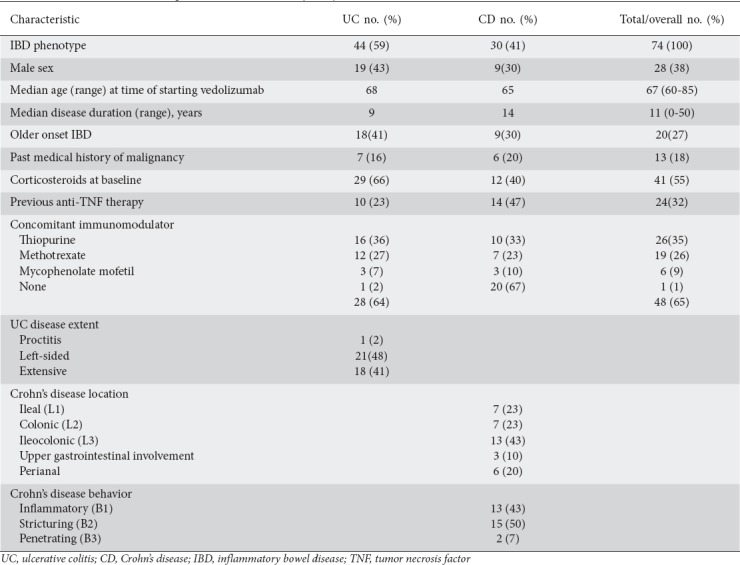

During the study period, 74 patients aged ≥60 years received at least 1 dose of vedolizumab and had follow-up data for at least 1 year. Forty-eight patients were included in the clinical effectiveness analysis (Table 1). The other 26 were excluded for the following reasons: 3 had a stoma, 13 had missing clinical data for week 14 and week 52, 9 had inactive baseline clinical activity scores, and 1 had surgery very shortly after the first infusion. Of the 48 patients included, the median age on starting vedolizumab was 66 (range 60-85) years; 17 patients were in the ≥70 age group. Of these, 10 (21%) were between 70-79 years and 7 (15%) were aged ≥80. Seventeen patients (35%) had older-onset IBD. Analysis of adverse events was performed for all 74 patients who received at least 1 dose of vedolizumab (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in clinical effectiveness analysis (n=48)

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in safety analysis (n=74)

Clinical effectiveness

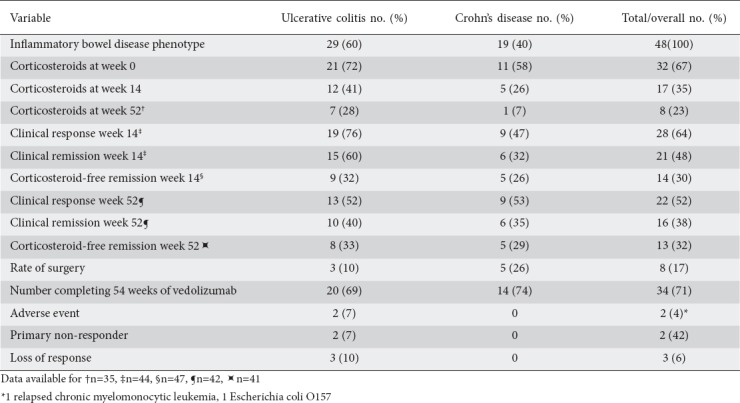

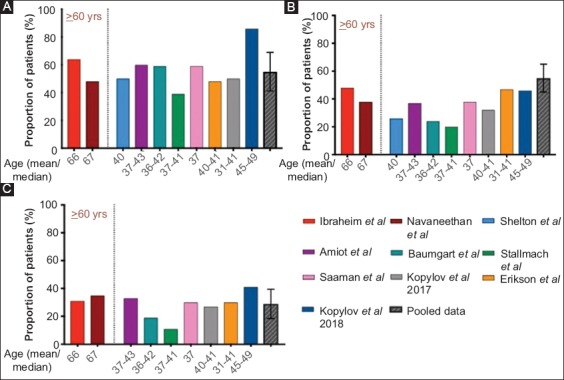

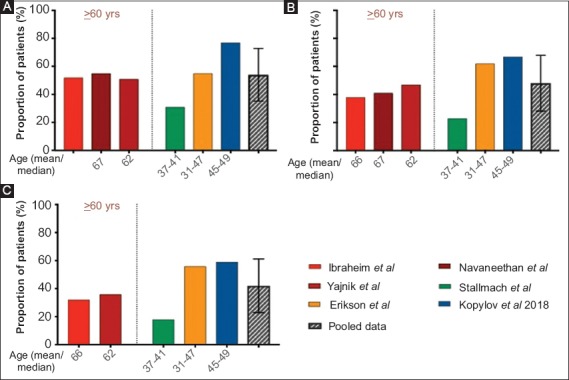

In patients ≥60 years, 28 (64%) had a clinical response at week 14. Of these, 21 (48%) were in clinical remission (Table 3), a higher rate than those reported in the majority of observational studies from age-unstratified populations [19-21,23,24,29,30] (Fig. 1A,B). Thirty percent achieved corticosteroid-free remission (Fig. 1C). At week 52, 21 (81%) had a clinical response (Fig. 2A), 16 (62%) had clinical remission (Fig. 2B) and 13 (52%) had corticosteroid-free remission (Fig. 2C). These rates were relatively lower than those reported in the age-unstratified populations.

Table 3.

Clinical effectiveness of vedolizumab in patients aged ≥60 years (n=48)

Figure 1.

Week 14 clinical response (A), clinical remission (B) and corticosteroid-free remission rates (C) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, comparing those aged ≥60 in our UK multicenter cohort with a non-age-stratified real-world series. The pooled data bar only represents studies from the age-unstratified real-world studies. Error bars represent ± 1 standard deviation. The age is represented on the X-axis as a median or mean. In some studies, the median or mean age was calculated for each subgroup (Crohn’s disease vs. ulcerative colitis) and not a group as a whole: in these cases both numbers are depicted

Figure 2.

Week 52 clinical response (A), clinical remission (B) and corticosteroid-free remission rates (C) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, comparing those aged ≥60 in our UK multicenter cohort with a non-age-stratified real-world series. The pooled data bar only represents studies from the age-unstratified real-world studies. Error bars represent ± 1 standard deviation. The age is represented on the X-axis as a median or mean. In some studies, the median or mean age was calculated for each subgroup (Crohn’s disease vs. ulcerative colitis) and not a group as a whole: in these cases both numbers are depicted

When taking into account disease type (UC vs. CD), the mean SCCAI scores in UC patients at baseline, week 14 and week 52 were 8 with a standard deviation (SD) of 3, 2 (SD 2) and 2 (SD 2), respectively. In CD patients, the mean HBI scores at baseline, week 14 and week 52 were 8 (SD 3), 5 (SD 3), and 4 (SD 3), respectively.

UC patients were numerically more likely than CD patients to experience clinical response or remission at week 14 (76% vs. 47% and 60% vs. 32% respectively). Findings in the UC group were generally more favorable than most of the age-unstratified comparator studies where rates of clinical response and remission ranged between 43%-57% (UC), whilst findings in the CD group were more comparable (22-42%) (Supplementary Fig. 1 (1.9MB, tif) ). At week 52, rates of clinical response, clinical remission and steroid-free remission were comparable between UC and CD patients (52% vs. 53%, 40% vs. 35%, 33% vs. 29%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2 (1.9MB, tif) ).

Safety

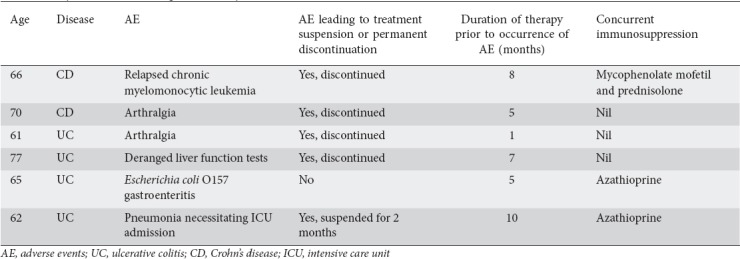

Adverse events were reported in 6/74 (8%) patients, leading to permanent discontinuation in 4/6 (Table 4). Three of these 6 patients were on concomitant immunosuppressive treatment: 1 with relapsed chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisolone, 1 with pneumonia requiring intensive care support on azathioprine, and 1 with Escherichia coli O157 on azathioprine. Of the 3/6 patients on vedolizumab monotherapy, 2 experienced arthralgia necessitating permanent discontinuation of therapy after 1 and 5 months, and 1 patient-developed deranged liver function tests, which resolved on cessation of treatment. According to age, 4/6 were in the 60-69 group and 2 were aged ≥70 years. There were no reported infusion reactions. One death occurred during the study period: a patient with relapsed CMML who had 8 months of vedolizumab therapy prior to the diagnosis.

Table 4.

Safety of vedolizumab in patients ≥60 years (n=74)

Discussion

Our study represents the largest cohort of older vedolizumab-treated patients reported to date and represents a real-world context for its use. Although randomized controlled trials represent the gold standard for establishing efficacy, patients are highly selected and not entirely representative of those encountered in clinical practice. Notably, 44% of our patients would have been excluded from the GEMINI studies because of concomitant medications, extensive CD surgery, and older age. Whilst the GEMINI trials included older patients, those over 80 were excluded. Our study included 7 patients over 80 years, 2 of whom were on concomitant thiopurine therapy while 3 had a past history of malignancy.

We report outcomes largely comparable to the majority of the age-unstratified observational studies, although interestingly we found more favorable week-14 outcomes. This may be attributed to a cohort that included a higher proportion of anti-TNF-naïve patients (73% compared to fewer than 25% in comparator studies), given how closely our findings resemble those from the European study in anti-TNF-naïve patients [25]. Additionally, over a third of our study group had older-onset IBD, ostensibly associated with a less aggressive disease course [5]. These merit further investigation, but to date, Navaneethan et al are the only group to report real-world clinical outcomes of vedolizumab-treated older patients (>60 years old) [31]. In their single-center study, which included 29 IBD patients, clinical response and remission rates were lower than in our group (Fig. 1,2). Corticosteroid-free remission was only reported for week 14, but was similar to our data. Although caution should be exercised when interpreting studies with small patient numbers, an important difference again relates to the lower proportion of anti-TNF-experienced patients included in our study (27% vs. 68.9%).

Yajnik et al performed a post hoc subgroup analysis of data from GEMINI 1 and 2, which analyzed moderately to severely active UC or CD, respectively, stratified into age groups: <35, 35 to <55, and ≥55 years. Two hundred and twenty patients (130 UC, 90 CD) were in the older group, and apart from having a longer duration of disease, and the CD patients having lower clinical activity scores at baseline, other baseline features were consistent amongst the groups. Similar percentages of vedolizumab-treated patients from each age group achieved a durable clinical response, durable clinical remission, mucosal healing, and corticosteroid-free remission at week 52, with no age-related trends [26].

Despite 42% of our patients being on an immunomodulator (compared to a range of 14-80.4% in the non-age-stratified real world studies), we, like others [21], did not observe a larger clinical benefit compared with vedolizumab monotherapy. Although our sample size may be too small to detect a difference, this finding was also apparent from a post hoc analysis of the pivotal trials, where the use of concomitant immunomodulators was 18.9% in GEMINI 1 and 16.1% in GEMINI 2 [15,16].

Consistent with the post hoc and post-marketing analyses, we found that the safety profile of vedolizumab in older patients was favorable [17,18]. The adverse event rate of 8% is comparable to other real-world series, where rates of 8.2% [19], 10.7% [21], and 14.2% [23] were reported. The 3 patients who developed either a serious infection or recurrence of malignancy were also on concomitant immunomodulators, which have a well-documented association with these outcomes. Two patients discontinued therapy secondary to arthralgia.

Limitations of our study include a lack of endoscopic data and a limited cohort size (particularly the CD group), which made subgroup analyses challenging. The majority of patients were on corticosteroids at baseline, thus introducing a confounding variable that may have influenced the perceived effectiveness of vedolizumab in the short term. Additionally, the risk of infective events associated with corticosteroids is well documented. The retrospective nature of the data may also have resulted in an underestimation of the number of adverse events. However, such biases are inevitable features of real-world studies and are therefore not dissimilar to other published real-world series.

In conclusion, our multicenter experience of vedolizumab in IBD patients aged 60 or older demonstrated that treatment was effective and well-tolerated at 1 year, and likely to be broadly comparable to cohorts unselected by age. Given the absence of prospective controlled studies of vedolizumab in elderly patients, our study provides reassuring insights into the potential benefit of vedolizumab as an effective and safe therapeutic option in this patient group.

Summary Box.

What is already known:

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the older population is rising, with up to 30% being over 60 years of age

Advanced age is an independent risk factor for serious adverse events and death in anti-tumor necrosis factor-treated patients

Post hoc analysis of GEMINI trial data suggests efficacy and safety profiles between vedolizumab and placebo are similar in all age groups

What the new findings are:

Advanced age was not a barrier to the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab

Vedolizumab and concomitant immunomodulation did not incur a clinical benefit over vedolizumab monotherapy

Supplementary Figure 1 Week 14 clinical response, clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission rates in patients with ulcerative colitis (A) and Crohn’s disease (B), comparing those aged ≥60 in our UK multicenter cohort with a non-age-stratified real-world series

Supplementary Figure 2 Week 52 clinical response, clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission rates in patients with ulcerative colitis (A) and Crohn’s disease (B), comparing those aged ≥60 in our UK multicenter cohort with a non-age-stratified real-world series

Biography

Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London; King’s College, London; Oxford University Hospitals Trust; University College London Hospital; King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London; Barts Health NHS Trust, London; Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge; St. Mark’s Hospital, London; Imperial College London, UK

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Mark A. Samaan: Served as a speaker, a consultant and/or an advisory board member for Janssen, Takeda, MSD, Falk. Oliver Brain: Served as a speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Janssen. Jonathan Digby-Bell: Served as a speaker for AbbVie and Takeda. Peter M. Irving: Served as a speaker, a consultant and/or an advisory board member for Janssen, AbbVie, Warner Chilcott, Ferring, Falk Pharma, Takeda, MSD, Johnson and Johnson, Shire, Vifor Pharma, Pharmacosmos, Topivert, Genentech, Hospira, Samsung Bioepis, and has received research funding from MSD, Takeda. Ana Ibarra: Served as a speaker for Janssen. Klaartje Bel Kok: Served as a speaker for Janssen. Gareth Parkes: Served as a speaker for Takeda, AbbVie and Janssen. Miles Parkes: Served as a speaker for Takeda. Jonathan Segal: Served as a consultant for Takeda. Ailsa Hart: Served as a consultant, advisory board member or speaker for AbbVie, Atlantic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Falk, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Napp Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Shire and Takeda. ALH also serves on the Global Steering Committee for Genentech. Bu’Hussain Hayee: Served as a speaker and consultant for Takeda. Nick Powell: Served as a speaker for Allergan, Falk, Janssen, Tillotts and Takeda a consultant and/or an advisory board member for AbbVie, Allergan, Debiopharm International, Ferring and Vifor Pharma

References

- 1.Piront P, Louis E, Latour P, Plomteux O, Belaiche J. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the elderly in the province of Liège. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2002;26:157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeuring SF, van Heuvel Zeegers MP, et al. Epidemiology and long-term outcome of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed at elderly age-an increasing distinct entity? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1425–1434. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loftus CG, Loftus J EV, Harmsen SW, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota 1940-2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:254–261. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loftus EV, Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gut. 2000;46:336–343. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charpentier C, Salleron J, Savoye G, et al. Natural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease:a population-based cohort study. Gut. 2014;63:423–432. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakatos PL, David G, Pandur T, et al. IBD in the elderly population:results from a population-based study in Western Hungary 1977-2008. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viola A, Monterubbianesi R, Scalisi G, et al. Italian Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) Late-onset Crohn's disease:a comparison of disease behaviour and therapy with younger adult patients:the Italian Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease 'AGED'study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:1361–1369. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz S, Pardi DS. Inflammatory bowel disease of the elderly:frequently asked questions (FAQs) Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1889–1897. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobatón T, Ferrante M, Rutgeerts P, Ballet V, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:441–451. doi: 10.1111/apt.13294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cottone M, Kohn A, Daperno M, et al. Advanced age is an independent risk factor for severe infections and mortality in patients given anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai A, Zator ZA, de Silva P, et al. Older age is associated with higher rate of discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:309–315. doi: 10.1002/ibd.23026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fidder HH, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease:a single center cohort study. Gut. 2008;58:501–508. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. CESAME Study Group. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease:a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filippini M, Bazzani C, Favalli EG, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-tumour necrosis factor in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis:an observational study. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2010;38:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colombel JF, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gut. 2017;66:839–851. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen RD, Bhayat F, Blake A, Travis S. The safety profile of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease:4 years of global post-marketing data. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:192–204. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Groupe d'Etude Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1593–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson C, Marsal J, Bergemalm D, et al. SWIBREG Vedolizumab Study Group. Long-term effectiveness of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease:a national study based on the Swedish National Quality Registry for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SWIBREG) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:722–729. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1304987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shelton E, Allegretti JR, Stevens B, et al. Efficacy of vedolizumab as induction therapy in refractory IBD patients:a multicenter cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2879–2885. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG. Inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly is associated with worse outcomes:a national study of hospitalizations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:182–189. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopylov U, Ron Y, Avni-Biron I, et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab for induction of remission in inflammatory bowel disease—the Israeli real-world experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:404–408. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samaan MA, Pavlidis P, Johnston E, et al. Vedolizumab:early experience and medium-term outcomes from two UK tertiary IBD centres. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2017;8:196–202. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2016-100720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopylov U, Verstockt B, Biedermann L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in anti-TNF-naïve patients with inflammatory bowel disease—a multicenter retrospective European Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2442–2451. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yajnik V, Khan N, Dubinsky M, et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients stratified by age. Adv Ther. 2017;3(4):542–559. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0467-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins P, Schwartz M, Mapili J, Krokos I, Leung J, Zimmermann EM. Patient defined dichotomous end points for remission and clinical improvement in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:782–788. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.056358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Sandborn WJ, Dubois C, Rutgeerts P. Correlation between the Crohn's disease activity and Harvey–Bradshaw indices in assessing Crohn's disease severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stallmach A, Langbein C, Atreya R, et al. Vedolizumab provides clinical benefit over 1 year in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease - a prospective multicenter observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1199–1212. doi: 10.1111/apt.13813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumgart DC, Bokemeyer B, Drabik A, Stallmach A, Schreiber S Vedolizumab Germany Consortium. Vedolizumab induction therapy for inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice—a nationwide consecutive German cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1090–1102. doi: 10.1111/apt.13594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navaneethan U, Edminister T, Zhu X, Kommaraju K, Glover S. Vedolizumab is safe and effective in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:E17. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 Week 14 clinical response, clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission rates in patients with ulcerative colitis (A) and Crohn’s disease (B), comparing those aged ≥60 in our UK multicenter cohort with a non-age-stratified real-world series

Supplementary Figure 2 Week 52 clinical response, clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission rates in patients with ulcerative colitis (A) and Crohn’s disease (B), comparing those aged ≥60 in our UK multicenter cohort with a non-age-stratified real-world series