Abstract

Aim: Obesity and metabolic syndrome (MetS) frequently coexist and are both important risk factors for cardiovascular disease. However, the pathophysiological role of obesity without MetS, also referred to as metabolically healthy obesity (MHO), remains unclear. In this study, we aim to clarify the effect of MHO on the development of carotid plaque using a community-based cohort.

Methods: We examined 1,241 subjects who underwent health checkups at our institute. Obesity was defined as body mass index of ≥ 25.0 kg/m2. Subjects were divided into three groups: non-obese, MHO, and metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO).

Results: The prevalence of carotid plaque, defined as intima-media thickness (IMT) ≥ 1.1 mm, was higher in subjects with MUO and MHO than in non-obese subjects. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that MHO (odds ratio 1.6, p = 0.012) and MUO (odds ratio 1.9, p = 0.003) as well as age of ≥ 65 years, male sex, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were independently associated with carotid plaque formation. A similar trend was observed in each subgroup according to age and sex.

Conclusions: MHO increased the prevalence of carotid plaque when compared with non-obese subjects, suggesting the potential significance of MHO in the development of subsequent cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Metabolically healthy obesity, Metabolic syndrome, Carotid plaque, Carotid intima-media thickness, Atherosclerosis

Introduction

Obesity is a common and independent risk factor for all-cause mortality1–3). More specifically, obesity is a major component of atherosclerosis in association with metabolic disorders, including metabolic syndrome (MetS), hypertension4–6), diabetes mellitus4, 6–9), and dyslipidemia6), resulting in the development of various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)4), such as coronary artery disease10–12), ischemic stroke11, 13), and peripheral artery disease14). Alternatively, obese subjects without MetS are also present and are referred to as subjects with metabolically healthy obesity (MHO)15). However, most preceding studies regarding MHO have been limited to small cohorts, and there are no consistent criteria for MHO. Therefore, the effect of MHO on atherosclerosis in the general population remains unclear. In this study, we aim to clarify the clinical significance of MHO in the development of subclinical CVD evaluated by carotid plaque formation using a community-based cohort.

Methods

Study Population

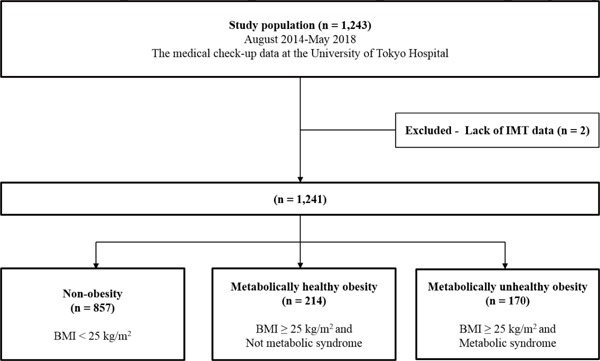

We examined 1,243 subjects who underwent medical checkups at the University of Tokyo Hospital between August 2014 and May 2018 16). All subjects were at least 18 years old, and those who agreed to participate in this study were eligible. We excluded two subjects who lacked IMT data and included 1,241 subjects in this study. (Patient flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

Patient demographics

Among 1,243 subjects who underwent medical checkup at our institute, two subjects who lacked intima-media thickness data were excluded.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Tokyo (No. 2017-2424). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Definiton

Obesity was defined as body mass index of ≥ 25.0 kg/m2, according to the diagnostic criteria in Asian people17, 18) and the guidlines of Japan Society for the Study of Obesity (JASSO: http://www.jasso.or.jp/contents/magazine/journal.html). Abdominal obesity, defined as waist circumstance at umbilical level ≥ 85 cm in men and ≥ 90 cm in women, was obligatory for diagnosis of MetS. In addition, any two of the following three anomalies should be observed for diagnosis of MetS: [1] high blood pressure, systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medications; [2] hyperglycemia, fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 110 mg/dL, or use of insulin or oral antidiabetic medications; and [3] dyslipidemia, triglyceride level ≥ 150 mg/dL, HDL-C < 40 mg/dL, or use of lipid-lowering medications19). MHO was defined as obese subjects without MetS, whereas metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO) was defined as obese subjects with MetS15). Hypertension was defined by blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined by fasting glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL or use of insulin or oral antidiabetic medications. Hypercholesterolemia was defined by total cholesterol level > 240 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering medications.

Mesurement of Intima-Media Thickness (IMT) and Definition of Carotid Plaque

Images were obtained by multiple experts in carotid imaging using a Aplio 300 TUS-A300 or Xario SSA-660A ultrasound system (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Tochigi, Japan) equipped with a 7.5-MHz linear probe. Common carotid ultrasound examination was performed with the subjects in a supine position. Their necks were hyperextended and their heads were turned contralateral to the test side. The left common carotid arteries were visualized from a fixed lateral transducer angle. Bilateral measurement of the strain was performed from the images of the short axis of the common carotid artery at 1 cm inferior to the carotid bulb. At least two consecutive beats were stored with a frame rate of 29–53 frames/s. Maximum IMT was defined as the distance between the leading edge of the luminal ultrasound and media/adventitia ultrasound. IMT of the common carotid artery was manually measured as the maximum thickness between the proximal and the common carotid bulb20, 21). We used the two right and left measurements on average to calculate IMT. Carotid plaque was defined as IMT ≥ 1.1 mm, as previously reported22). The reproducibility of the IMT was assessed using a similar technique that has already been previously reported23–25).

Subgroup Analyses

The association between obesity category and carotid plaque formation was assessed in two subgroups according to age (< 65 and ≥ 65 years old) and sex.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical and consecutive data on the baseline clinical characteristics are presented as percentages (%) and mean ± standard deviation, respectively. Chi-square analysis was performed to compare categorical variables. Consecutive data were compared by one-way analysis of variance, whereas statistical significance of the difference was calculated using Tukey t-test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify the association between potential factors, including age, male gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, coronary artery disease, smoking, obesity category (non-obese, MHO, and MUO), and carotid plaque formation. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the independent predictors of carotid plaque formation. A probability value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant difference. We performed statistical analysis using SPSS version 25 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographics of study subjects are presented in Table 1. Among 1,241 subjects, 857 (69%) were categorized in the normal body weight group, whereas 214 (17%) were categorized as MHO and 170 (14%) were categorized as MUO. Subjects with obesity were more likely to be male, whereas those without obesity were older. Prevalence of classical cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and cigarette smoking, was different in the three groups (non-obese, MHO, and MUO).

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics.

| Variable | Total | Non-obese (n = 857) |

Metabolically healthy obesity (n = 214) |

Metabolically unhealthy obesity (n = 170) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 62.6 ± 11.7 | 63.1 ± 11.7 | 61.0 ± 11.7 | 62.5 ± 11.7 | 0.067 |

| Age ≥ 65 years old | 598 (48.2%) | 434 (50.6%) | 83 (38.8%) | 81 (47.6%) | 0.008 |

| Gender, Male | 699 (56.3%) | 421 (49.1%) | 140 (65.4%) | 138 (81.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 3.6 | 21.7 ± 2.1 | 26.8 ± 1.8 | 28.6 ± 3.5 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 449 (36.2%) | 250 (29.2%) | 63 (29.4%) | 136 (80.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 132 (10.6%) | 70 (8.2%) | 10 (4.7%) | 52 (30.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 461 (37.1%) | 322 (37.6%) | 60 (28.0%) | 79 (46.5%) | 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 32 (2.6%) | 20 (2.3%) | 3 (1.4%) | 9 (5.3%) | 0.041 |

| Smoking | 469 (37.8%) | 299 (34.9%) | 96 (44.9%) | 74 (43.5%) | 0.007 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 225 (18.1%) | 55 (6.4%) | 0 (0%) | 170 (100%) | < 0.001 |

| Biochemistry | |||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 100.0 ± 20.0 | 97.2 ± 16.7 | 98.4 ± 16.2 | 116.4 ± 29.7 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 6.4 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| T-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 205.1 ± 34.3 | 207.2 ± 34.2 | 207.3 ± 31.7 | 191.6 ± 35.1 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 124.1 ± 30.5 | 123.7 ± 30.5 | 131.9 ± 30.9 | 116.3 ± 29.6 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 65.4 ± 18.5 | 69.7 ± 18.7 | 58.7 ± 13.5 | 51.8 ± 13.4 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 110.9 ± 80.0 | 99.1 ± 76.0 | 116.8 ± 67.9 | 163.1 ± 92.0 | < 0.001 |

| Metabolic risk components | |||||

| Waist circumstance | 478 (38.5%) | 150 (17.5%) | 158 (73.8%) | 170 (100%) | < 0.001 |

| High blood pressure | 574 (46.3%) | 333 (38.9%) | 89 (41.6%) | 152 (89.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | 222 (17.9%) | 111 (13.0%) | 15 (7.0%) | 96 (56.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 477 (38.4%) | 279 (32.6%) | 59 (27.6%) | 139 (81.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Number of metabolic risks components | |||||

| 0 | 423 (34.1%) | 355 (41.4%) | 68 (31.8%) | 0 (0%) | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 452 (36.4%) | 321 (37.5%) | 131 (61.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 277 (22.3%) | 141 (16.5%) | 13 (6.1%) | 123 (72.4%) | |

| 3 | 89 (7.2%) | 40 (4.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 47 (27.6%) |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, or percentage (number).

LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Prevalence of Carotid Plaque Formation

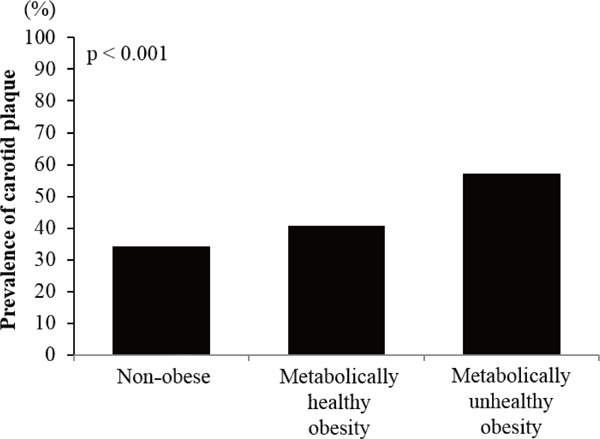

Fig. 2 shows the comparison of the prevalence of carotid plaque formation in the three groups. The prevalence increased in subjects with MHO subjects (41%) as compared with non-obese subjects (34%) and further increased in subjects with MUO (57%).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of carotid plaque

The prevalence of carotid plaque formation was higher in subjects with obesity (both metabolically healthy and metabolically unhealthy) than in non-obese subjects

Determinants of Carotid Plaque Formation

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that subjects with MHO [odds ratio (OR), 1.3; p = 0.078] as well as those with MUO (OR 2.6, p < 0.001) were associated with carotid plaque formation as compared with non-obese subjects (Table 2). Multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated that age, male gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, subjects with MHO (OR; 1.6, p = 0.012), and subjects with MUO (OR 1.9, p = 0.003) were independently associated with carotid plaque formation. There was no statistical difference in the risk of carotid plaque formation between subjects with MHO and MUO (Table 2).

Table 2. Determinants of carotid plaque.

| Variables | Univariate Analysis |

Multivariable Analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | < 0.001 | 1.084 (1.070 – 1.097) | < 0.001 | 1.088 (1.073 – 1.103) |

| Gender, Male | < 0.001 | 1.981 (1.563 – 2.511) | < 0.001 | 2.325 (1.718 – 3.147) |

| Hypertension | < 0.001 | 2.649 (2.085 – 3.367) | 0.001 | 1.640 (1.236 – 2.178) |

| Diabetes mellitus | < 0.001 | 3.074 (2.115 – 4.468) | 0.047 | 1.540 (1.005 – 2.361) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.002 | 1.453 (1.148 – 1.839) | 0.397 | 1.124 (0.857 – 1.475) |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.088 | 1.845 (0.913 – 3.731) | 0.841 | 0.922 (0.415 – 2.047) |

| Smoking | 0.742 | 1.040 (0.822 – 1.317) | 0.495 | 0.902 (0.671 – 1.213) |

| Stage | ||||

| Non-obese | Reference | Reference | ||

| MHO | 0.078 | 1.319 (0.970 – 1.793) | 0.012 | 1.564 (1.102 – 2.222) |

| MUO | < 0.001 | 2.558 (1.830 – 3.575) | 0.003 | 1.857 (1.226 – 2.811) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval, MHO, Metabolically healthy obesity, MUO, Metabolically unhealthy obesity

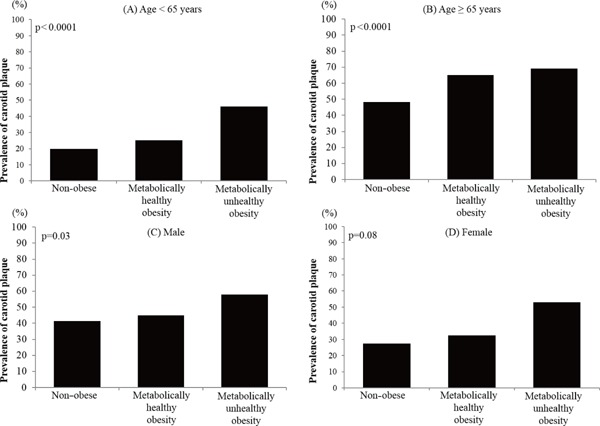

Subgroup Analyses

The prevalence of carotid plaque formation was higher in subjects with MHO and MUO as compared with non-obese subjects having age < 65 years old or age ≥ 65 years old as well as in male non-obese subjects. A similar trend was also seen in the female subgroup (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of carotid plaque in subjects with age < 65 years (A), ≥ 65 years (B), male sex (C), and female sex (D)

The prevalence of carotid plaque formation was significantly higher in subjects with obesity (both metabolically healthy and metabolically unhealthy) than in non-obese subjects in subgroups of age < 65 years (A), age ≥ 65 years (B), and male sex (C). A similar trend was observed in the female subgroup (D)

Discussion

The present study examines the general population who underwent health checkups at our institute, with a focus on the influence of MHO on IMT and carotid plaque formation. Three major findings were observed. First, obesity was observed in 31% of the general population, and 56% of the subjects with obesity were categorized as MHO. Second, the prevalence of carotid plaque formation was higher in subjects with MHO and MUO as compared with non-obese subjects. Third, the prevalence of carotid plaque was higher in subjects with MHO and MUO as compared with non-obese subjects, irrespective of age and sex.

Obesity is a worldwide pandemic public health problem26, 27), and its prevalence is also increasing in Japan due to the westernized and industrialized lifestyle28). An excess of visceral adipose fat in subjects with obesity is known to be an important source of various molecules such as inflammatory cytokines inducing metabolic disorders. Therefore, obesity and MetS frequently coexist and accelerate the development of subsequent CVD. However, recent studies have identified a phenotype, i.e., so-called MHO, which has a low burden of metabolic disorders29, 30). This phenotype attracts clinical interests, particularly regarding its impact on subclinical CVD.

IMT is an established marker for subclinical CVD in the general population and is a good predictor of subsequent CVD. According to preceding studies, obesity and MetS are associated with increased IMT and carotid plaque formation31–34). However, the relationship between MHO phenotype and the prevalence of carotid plaque has remained unknown. Therefore, we investigated whether the MHO phenotype is associated with increased carotid plaque formation in the general population.

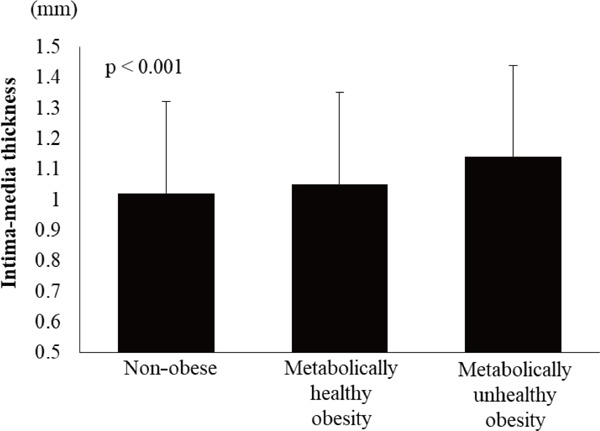

Approximately one-third of our subjects were obese. This percentage is similar to that in preceding studies involving a general population35–37). Among subjects with obesity, more than half of the subjects were categorized as having MHO; therefore, MHO is not a rare condition in the general population. IMT was significantly different between non-obese, MHO, and MUO groups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similar to IMT, the prevalence of carotid plaque formation was also higher in subjects with obesity. Multivariable analysis presented that MHO and MUO were independently associated with higher prevalence of carotid plaque, suggesting that obesity induced subclinical CVD regardless of the presence of MetS and that obesity itself should be the prevention target for future CVD events.

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Intima-media thickness

In contrast, the importance of metabolic disorders in subjects with obesity based on the results of this study cannot be denied. We defined MHO as obese subjects without MetS. Therefore, 68% of subjects with MHO had at least one component that met the criteria of MetS. Given that each component included in the definition of MetS, such as high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia, can induce atherosclerosis, metabolic disorders of subjects categorized as having MHO might weaken the potential difference in IMT between subjects with MHO and MUO. In fact, subjects with MUO tended to have a higher prevalence of carotid plaque formation. Although the difference did not reach a statistically significant value, this may be attributed to the limited sample size. Further studies with larger sample size are warranted to clarify this point.

Subgroup analysis showed the effect of MHO in each subgroup according to age and sex. In particular, presence of MHO increased the prevalence of carotid plaque formation as compared with non-obese subjects, even in subgroups with younger age or female sex, who are supposed to be at low risk of CVD. Therefore, the risk of MHO in the general population with relatively low CVD risk should not be underestimated.

The present study has several limitations. First, the presented data are from a single-center experience; therefore, the present findings may not be simply generalized. The statistical power might not be sufficient for any statistically nonsignificant data to be conclusive because of the limited sample size. Although multivariable regression analysis was performed, unmeasured confounders may have influenced the results. Second, MHO is a novel concept and its definition has not yet established. In this study, we defined MHO as obesity without MetS. However, there are various definitions of MHO given in preceding studies38–40). Although detailed analysis is not available due to the limited sample size, the effect of obesity on the percentage of carotid plaque formation can differ according to the number subjects with metabolic disorders. Therefore, further study is required to establish the optimal definition of MHO. Third, among non-obese subjects, MetS was observed in 55 subjects (6.4%). Because of the small sample size, the significance of this subset could not be analyzed. Fourth, the effect of medication was not assessed in detail, particularly the type of lipid-lowering medications used. Fifth, detailed information regarding alcohol drinking status, which can influence the results, is not available. Finally, we did not perform multivariable analysis for IMT. Therefore, we cannot conclude that IMT was independently higher in subjects with MHO and MUO than in non-obese subjects.

Conclusion

The prevalence of carotid plaque is higher in both subjects with MHO and MUO as compared with non-obese subjects in the general population. Regardless of the presence of MetS, we need to consider obesity as a high-risk factor for subsequent CVD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all staff of the Center for Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at our institute.

Funding Source

This study was self-funded.

Conflict of Interest

I.K. received lecture honoraria from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Japan, Astellas, Amgen Astellas Bio-Pharma, AstraZeneca, MSD, Shionogi & Co, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, TOA EIYO, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Yakuhin and Pfizer Japan, clinical research funding from IQVIA, Meiji, Daiichi Sankyo Company and Ono Pharmaceutical Company, and scholarship grants from Astellas, Edwards Life Science, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Teijin Pharma, Bayer Yakuhin, NIPRO and Terumo Corporation. H.K. received the research funding and scholarship fundsfrom Medtronic Japan CO., LTD, Abbott Medical Japan CO., LTD, Boston Scientific Japan CO., LTD and Fukuda Denshi, Central Tokyo CO., LTD. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1). Stevens J, Cai J, Pamuk ER, Williamson DF, Thun MJ, Wood JL. The effect of age on the association between body-mass index and mortality. N Engl J Med, 1998; 338: 1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). de Gonzalez AB, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, Moore SC, Tobias GS, Anton-Culver H, Freeman LB, Beeson WL, Clipp SL, English DR, Folsom AR, Freedman DM, Giles G, Hakansson N, Henderson KD, Hoffman-Bolton J, Hoppin JA, Koenig KL, Lee IM, Linet MS, Park Y, Pocobelli G, Schatzkin A, Sesso HD, Weiderpass E, Willcox BJ, Wolk A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Willett WC, Thun MJ. Body-Mass Index and Mortality among 1.46 Million White Adults. New Engl J Med, 2010; 363: 2211-2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 2013; 309: 71-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006; 26: 968-976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Huang Z, Willett WC, Manson JE, Rosner B, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Colditz GA. Body weight, weight change, and risk for hypertension in women. Ann Intern Med, 1998; 128: 81-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Nguyen NT, Magno CP, Lane KT, Hinojosa MW, Lane JS. Association of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome with obesity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. J Am Coll Surg, 2008; 207: 928-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care, 1994; 17: 961-969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med, 1995; 122: 481-486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Sullivan PW, Morrato EH, Ghushchyan V, Wyatt HR, Hill JO. Obesity, inactivity, and the prevalence of diabetes and diabetes-related cardiovascular comorbidities in the U.S., 2000–2002. Diabetes Care, 2005; 28: 1599-1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, Lang CC, Rumboldt Z, Onen CL, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P, Jr., Razak F, Sharma AM, Anand SS, Investigators IS Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet, 2005; 366: 1640-1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases C. Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Ezzati M, Woodward M, Rimm EB, Danaei G. Metabolic mediators of the effects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1.8 million participants. Lancet, 2014; 383: 970-983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). McGill HC, Jr., McMahan CA, Herderick EE, Zieske AW, Malcom GT, Tracy RE, Strong JP, Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth Research G Obesity accelerates the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in young men. Circulation, 2002; 105: 2712-2718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Mitchell AB, Cole JW, McArdle PF, Cheng YC, Ryan KA, Sparks MJ, Mitchell BD, Kittner SJ. Obesity increases risk of ischemic stroke in young adults. Stroke, 2015; 46: 1690-1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Huang Y, Xu M, Xie L, Wang T, Huang X, Lv X, Chen Y, Ding L, Lin L, Wang W, Bi Y, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Ning G. Obesity and peripheral arterial disease: A Mendelian Randomization analysis. Atherosclerosis, 2016; 247: 218-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Mongraw-Chaffin M, Foster MC, Anderson CAM, Burke GL, Haq N, Kalyani RR, Ouyang P, Sibley CT, Tracy R, Woodward M, Vaidya D. Metabolically Healthy Obesity, Transition to Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018; 71: 1857-1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Itoh H, Kaneko H, Kiriyama H, Yoshida Y, Nakanishi K, Mizuno Y, Daimon M, Morita H, Yatomi Y, Komuro I. Relation between the Updated Blood Pressure Classification according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines and Carotid Intima-Media Thichness. Am J Cardiol, 2019; 124: 396-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Kanazawa M, Yoshiike N, Osaka T, Numba Y, Zimmet P, Inoue S. Criteria and classification of obesity in Japan and Asia-Oceania. World Rev Nutr Diet, 2005; 94: 1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). TaskForce International Obesity. The Asia-Pacfic perspective: Redefining obesity and its treatment World Health Organization Western Pacific Region. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 19). Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC, Jr., International Diabetes Federation Task Force on E, Prevention, Hational Heart L, Blood I, American Heart A, World Heart F, International Atherosclerosis S, International Association for the Study of O Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation, 2009; 120: 1640-1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Iino H, Okano T, Daimon M, Sasaki K, Chigira M, Nakao T, Mizuno Y, Yamazaki T, Kurano M, Yatomi Y, Sumi Y, Sasano T, Miyata T. Usefulness of Carotid Arterial Strain Values for Evaluating the Arteriosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Handa N, Matsumoto M, Maeda H, Hougaku H, Ogawa S, Fukunaga R, Yoneda S, Kimura K, Kamada T. Ultrasonic Evaluation of Early Carotid Atherosclerosis. Stroke, 1990; 21: 1567-1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Salonen R, Salonen JT. Progression of carotid atherosclerosis and its determinants: a population-based ultrasonography study. Atherosclerosis, 1990; 81: 33-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Kanters SD, Algra A, van Leeuwen MS, Banga JD. Reproducibility of in vivo carotid intima-media thickness measurements: a review. Stroke, 1997; 28: 665-671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Gonzalez J, Wood JC, Dorey FJ, Wren TA, Gilsanz V. Reproducibility of carotid intima-media thickness measurements in young adults. Radiology, 2008; 247: 465-471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Kim GH, Youn HJ. Is Carotid Artery Ultrasound Still Useful Method for Evaluation of Atherosclerosis? Korean Circ J, 2017; 47: 1-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L, Nedcom tNE, Demography Compression of Morbidity Research G Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med, 2003; 138: 24-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Meldrum DR, Morris MA, Gambone JC. Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertil Steril, 2017; 107: 833-839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Nishi N. Monitoring Obesity Trends in Health Japan 21. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo), 2015; 61 Suppl : S17-S19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Karelis AD. Metabolically healthy but obese individuals. Lancet, 2008; 372: 1281-1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Primeau V, Coderre L, Karelis AD, Brochu M, Lavoie ME, Messier V, Sladek R, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Characterizing the profile of obese patients who are metabolically healthy. Int J Obes (Lond), 2011; 35: 971-981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Lo J, Dolan SE, Kanter JR, Hemphill LC, Connelly JM, Lees RS, Grinspoon SK. Effects of obesity, body composition, and adiponectin on carotid intima-media thickness in healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006; 91: 1677-1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Burke GL, Bertoni AG, Shea S, Tracy R, Watson KE, Blumenthal RS, Chung H, Carnethon MR. The impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical vascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med, 2008; 168: 928-935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Muller DC, Andres R, Hougaku H, Metter EJ, Lakatta EG. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the age-associated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2004; 43: 1388-1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Heiss G, Golden SH, Duncan BB, East HE, Ballantyne C. Prevalence of coronary heart disease and carotid arterial thickening in patients with the metabolic syndrome (The ARIC Study). Am J Cardiol, 2004; 94: 1249-1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Kokubo Y, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Nakao YM, Kobayashi T, Watanabe T, Okamura T, Okayama A, Miyamoto Y. Interaction of Blood Pressure and Body Mass Index With Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation in a Japanese Urban Cohort: The Suita Study. Am J Hypertens, 2015; 28: 1355-1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Kubo M, Hata J, Doi Y, Tanizaki Y, Iida M, Kiyohara Y. Secular trends in the incidence of and risk factors for ischemic stroke and its subtypes in Japanese population. Circulation, 2008; 118: 2672-2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Shibata Y, Ojima T, Nakamura M, Kuwabara K, Miyagawa N, Saito Y, Nakamura Y, Kiyohara Y, Nakagawa H, Fujiyoshi A, Kadota A, Ohkubo T, Okamura T, Ueshima H, Okayama A, Miura K. Associations of Overweight, Obesity, and Underweight With High Serum Total Cholesterol Level Over 30 Years Among the Japanese Elderly: NIPPON DATA 80, 90, and 2010. J Epidemiol, 2019; 29: 133-138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Hashimoto Y, Tanaka M, Okada H, Senmaru T, Hamaguchi M, Asano M, Yamazaki M, Oda Y, Hasegawa G, Toda H, Nakamura N, Fukui M. Metabolically Healthy Obesity and Risk of Incident CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephro, 2015; 10: 578-583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Uehara S, Sato KK, Shibata M, Oue K, Kambe H, Morimoto M, Hayashi T. The Association between Metabolically Healthy Obese Phenotype and the Risk of Proteinuria: The Kansai Health Care Study. Diabetes, 2017; 66: A556-A556 [Google Scholar]

- 40). Caleyachetty R, Thomas GN, Toulis KA, Mohammed N, Gokhale KM, Balachandran K, Nirantharakumar K. Metabolically Healthy Obese and Incident Cardiovascular Disease Events Among 3.5 Million Men and Women. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2017; 70: 1429-1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]