Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been changing the paradigm of cancer treatment. However, immune-related adverse effects (irAEs) have also increased with the exponential increase in the use of ICIs. ICIs can break up the immunologic homeostasis and reduce T-cell tolerance. Therefore, inhibition of immune checkpoint can lead to the activation of autoreactive T-cells, resulting in various irAEs similar to autoimmune diseases. Gastrointestinal toxicity, endocrine toxicity, and dermatologic toxicity are common side effects. Neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and pulmonary toxicity are relatively rare but can be fatal. ICI-related gastrointestinal toxicity, dermatologic toxicity, and hypophysitis are more common with anti- CTLA-4 agents. ICI-related pulmonary toxicity, thyroid dysfunction, and myasthenia gravis are more common with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Treatment with systemic steroids is the principal strategy against irAEs. The use of immune-modulatory agents should be considered in case of no response to the steroid therapy. Treatment under the supervision of multidisciplinary specialists is also essential, because the symptoms and treatments of irAEs could involve many organs. Thus, this review focuses on the mechanism, clinical presentation, incidence, and treatment of various irAEs.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Adverse events, Programmed cell death 1

INTRODUCTION

Immunotherapy has opened up new horizons for cancer treatment (1). In particular, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways have been used to treat various solid cancers. Currently, Food and Drug Administration approved ICIs include anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 inhibitors (pembrolizumab and nivolumab), and PD-L1 inhibitors (atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab). The superiority of the effects of these drugs has been demonstrated, compared to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, although various side effects are present. Recently, combination therapy with various ICIs and cytotoxic chemotherapy has been initiated and various side effects are expected (2).

Frequent immune-related adverse events (irAEs) include gastrointestinal, endocrine, and dermatologic toxicities. Fatal irAEs include neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and pulmonary toxicity (3). The incidence of irAEs is higher in ICI combination therapy than in ICI monotherapy (4). Majorities of clinical trials excluded cancer patients with underlying autoimmune disease or chronic infection (viral or tuberculosis). So, irAEs is expected to increase further when we use immunotherapy in real clinical practice. In addition, some of the symptoms (i.e. cardio or joint toxicity) may be overlooked and confused with the cancer related symptoms of the patients. Thus, the monitoring system for early diagnosis is needed and it can improve treatment of irAEs.

IrAEs are evaluated and treated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, European Society for Medical Oncology guideline and American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline (Tables 1 and 2) (5,6,7). Treatment for grade 1 toxicity is conservative and maintenance of ICIs therapy is considered based on symptoms and involved organs. ‘Hold immunotherapy’ and oral prednisone treatment should be considered in grade 2 toxicity. In grade 3 or 4 toxicity, ICIs should be discontinued, and higher doses of systemic steroids should be considered. If patients do not respond to steroids, immunomodulatory therapy should be initiated. If systemic steroid and immunomodulatory therapy do not improve symptoms, intravenous immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis treatment should be considered in fatal irAEs. Retrying ICIs therapy is not recommended until the irAE has improved to grade 1 or the symptoms have disappeared. In case of fatal irAEs or grade 4 irAEs, retrying ICIs therapy is not recommended. Some irAEs have been reported to be associated with a favorable clinical outcome, but this is still controversial (8). ICIs can be used cautiously in most patients with comorbidities, but it is dangerous for solid-organ transplant patients (9). In this review, we describe the mechanism, clinical presentation, incidence, and treatment based on the organ(s) affected by the irAEs, such as abdomen, endocrine organ, joint and skin, nervous system, and thorax.

Table 1. Grading system (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0, European Society for Medical Oncology guideline, American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline).

| The organ(s) | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute kidney injury (Cr increased) | 1.0–1.5 × ULN | 1.5–3.0 × ULN | 3.0–6.0 × ULN | >6.0 × ULN | |

| <1.5 × baseline | 1.5–3.0 × baseline | >3.0 × baseline | Dialysis indicated | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | - Mild pain with inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling | - Moderate pain with inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling | - Severe pain with inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling | ||

| - Limiting instrumental ADL | - Irreversible joint damage | ||||

| - Limiting self-care ADL | |||||

| Colitis | - Asymptomatic | - Abdominal pain | - Severe abdominal pain peritoneal signs | - Life-threatening consequences | |

| - Increase of fewer than 4 stools per day | - Mucus or blood in stool | - Change in bowel habit | |||

| - Increase of four to 6 stools per day | - Increase of seven or more stools per day | ||||

| Hepatitis (AST, ALT increased) | <3.0 × ULN | 3.0–5.0 × ULN | 5.0–20.0 × ULN | >20.0 × ULN | |

| - Asymptomatic | - Asymptomatic | - Symptomatic liver dysfunction | - Decompensated liver function (ascites, coagulopathy, encephalopathy, coma) | ||

| - Compensated cirrhosis | |||||

| - Reactivation of chronic hepatitis | |||||

| Hypophysitis | - Asymptomatic or mild symptoms | - Moderate symptoms limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL | - Severe or medically significant limiting self-care ADL | - Life-threatening consequences (visual field impairment) | |

| Skin rash | - Target lesions covering <10% BSA and not associated with skin tenderness | - Target lesions covering 10%–30% BSA and associated with skin tenderness | - Target lesions covering >30% BSA | ||

| - Severe/life-threatening symptoms | |||||

| - Generalized exfoliative/ulcerated/bullous rash | |||||

| Fatal adverse effects | |||||

| Myasthenia gravis | - Asymptomatic or mild symptoms | - Moderate symptoms | - Severe or medically significant | - Life-threatening consequences (respiratory muscle involved) | |

| - Limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL | - Limiting self-care ADL | ||||

| Myocarditis | - Asymptomatic | - Symptoms with moderate activity or exertion | - Severe with symptoms at rest or with minimal activity or exertion | - Life-threatening consequences (hemodynamic impairment) | |

| - Cardiac enzyme elevation or abnormal EKG | |||||

| Pneumonitis | - Asymptomatic | - Symptomatic (dyspnea, cough or chest pain) | - Severe symptoms (new or worsening hypoxia) | - Life-threatening respiratory compromise (need intubation and ventilator care) | |

| - Confined to one lobe of the lung or <25% of lung parenchyma | - More than one lobe of the lung or 25%–50% of lung parenchyma | - All lung lobes or >50% of lung parenchyma | |||

| - Need oxygen therapy | |||||

Cr, creatinine; ULN, upper limit normal; ADL, activity of daily living; BSA, body surface area; EKG, electrocardiogram.

Table 2. Management of irAEs (European Society for Medical Oncology guideline, American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline).

| The organ(s) | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute kidney injury | - Consider ‘Hold immunotherapy’ | - Hold immunotherapy | - Permanently discontinue immunotherapy | - IV methylprednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | |

| - Hydration | - Oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day | - Oral prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | - Start dialysis | ||

| - Check and stop nephrotoxic drug (PPI or NSAIDs) | - A nephrology consultation | ||||

| Inflammatory arthritis | - Continue immunotherapy | - Consider ‘Hold immunotherapy’ | - Hold immunotherapy | ||

| - NSAIDs (eg, ibuprofen) or acetaminophen | - Oral prednisone 10–20 mg/day | - Oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day | |||

| - Intra-articular steroid injection | - Consider immunomodulatory therapy (DMARDs) in steroid non-responders | ||||

| - A rheumatology consultation | |||||

| Colitis | - Continue immunotherapy | - Consider ‘Hold immunotherapy’ | - Hold immunotherapy | - Permanently discontinue immunotherapy | |

| - Oral fluids | - Oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day | - Oral prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | - IV methylprednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | ||

| - Antidiarrheal agents (eg, loperamide) | - Consider sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy | - Consider immunomodulatory therapy (infliximab 5–10mg/kg, mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus) in steroid non-responders | |||

| - Avoid high fibre/lactose diet | - A gastroenterology consultation | ||||

| Hepatitis | - Continue immunotherapy | - Hold immunotherapy | - Permanently discontinue immunotherapy | ||

| - Check hepatotoxic drug | - Oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day | - IV methylprednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | |||

| - Consider immunomodulatory therapy (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine or tacrolimus) in steroid non-responders | |||||

| - Do not offer infliximab | |||||

| - A hepatology consultation | |||||

| Hypophysitis | - Consider ‘Hold immunotherapy’ | - Consider ‘Hold immunotherapy’ | - Hold immunotherapy | ||

| - Start glucocorticoid replacement with stress day rules (e.g., hydrocortisone 10–20 mg orally in the morning, 5–10 mg orally in early afternoon, levothyroxine by weight) | - Oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day | - Oral prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | |||

| - An endocrinology consultation | |||||

| Skin rash | - Continue immunotherapy | - Consider ‘Hold immunotherapy’ | - Hold immunotherapy | - IV prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | |

| - Topical emollients | - Oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day | - A dermatology consultation | - Consider immunomodulatory therapy in steroid non-responders | ||

| - Topical corticosteroids | - Oral prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | ||||

| - Oral antihistamines for pruritus | |||||

| Fatal adverse effects | |||||

| Myasthenia gravis | - Continue immunotherapy | - Hold immunotherapy | - Permanently discontinue immunotherapy | ||

| - Monitor symptoms for progression | - Oral prednisone 1–1.5 mg/kg/day | - IV methylprednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | |||

| - Pyridostigmine starting at 30 mg orally three times a day | - Consider IVIG or plasmapheresis in steroid non-responders | ||||

| - Consider immunomodulatory therapy (azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate) in steroid non-responders | |||||

| - A neurology consultation | |||||

| Myocarditis | - Hold or permanently discontinue immunotherapy at any sign of cardiotoxicity | ||||

| - Systemic steroid (oral prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day – methylprednisolone 1 g every day) | |||||

| - Consider additional immunomodulatory therapy (mycophenolate, infliximab, tacrolimus, or antithymocyte globulin) | |||||

| - Consider IVIG or plasmapheresis for unstable patients | |||||

| Pneumonitis | - Hold immunotherapy | - Hold immunotherapy | - Permanently discontinue immunotherapy | ||

| - Oral prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | - IV methylprednisone 1–2 mg/kg/day | ||||

| - Consider empirical antibiotics | - Empirical antibiotics | ||||

| - Consider bronchoscopy and/or BAL | - Consider additional immunomodulatory therapy (infliximab 5 mg/kg, mycophenolate mofetil IV 1 g twice a day or cyclophosphamide) | ||||

| - Consider IVIG if there is no improvement | |||||

| - A pulmonology consultation | |||||

DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage.

MECHANISM Of irAEs

ICIs block inhibitory checkpoint and activate T-cell mediated immune response. The precise mechanism of irAEs is still unknown, but several hypotheses are suggested. The key idea is that the use of ICIs breaks up the immunologic homeostasis and reduces T-cell tolerance (10). There is some cross-reactivity of T-cells between tumor cells and normal tissue (11). ICIs can increase levels of preexisting autoantibodies, such as antithyroid Abs (12). ICIs can also increase the level of inflammatory cytokines. In organs that express CTLA-4 or PD-L1 directly to protect normal tissue, such as in normal pituitary cells or cardiomyocytes, ICI can disturb these self-protect system (13,14). Due to these various reasons, activated T-cells attack healthy tissue, resulting in irAEs with features similar to autoimmune diseases.

ABDOMEN

Gastrointestinal tract

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

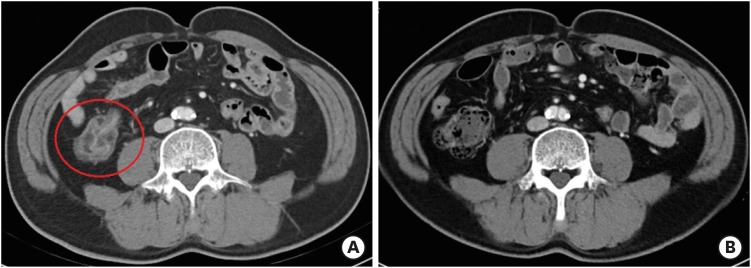

Gastrointestinal toxicity is a common side effect of ICIs. Nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, and epigastric pain may occur when the side effects involve the upper gastrointestinal tract; abdominal pain, hematochezia, and diarrhea may occur when the side effects involve the lower gastrointestinal tract. Lower gastrointestinal tract toxicity occurs more often than upper gastrointestinal tract toxicity. However, asymptomatic or non-specific symptom, which is not related to gastrointestinal symptoms, is also common (Fig. 1A and B). Endoscopy is helpful in diagnosing ICI-induced colitis and the assessment of therapeutic response (15). Stool analysis for bacterial pathogens and clostridium difficile toxin should be considered for differential diagnosis.

Figure 1. Enterocolitis related to immune checkpoint inhibitors. (A) Before steroid treatment, axial contrast computed tomography scan shows wall thickening and abnormal enhancement in intestine. (B) After steroid treatment, intestinal wall thickening and abnormal enhancement are reduced.

Incidence

Generally, anti-CTLA-4 agents are known to show higher incidence and severity of gastrointestinal side effects than those shown by PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (16,17). The incidence of side effects is higher in ICIs combination therapy than in ICIs monotherapy (4); moreover, the onset of the side effects is faster (18,19) and occurs 6–8 weeks after the start of ICIs treatment. In the case of anti-CTLA-4 agents, side effects can occur several months after the drug is discontinued. This is because the molecular effects of anti-CTLA-4 agents that are maintained after drug clearance (20).

Treatment strategies

The first choice of treatment is a systemic steroid (oral prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day) (21). Infliximab (anti-TNF-α) may be considered for patients that do not respond to systemic steroids (22). Recently, the use of vedolizumab (a humanized monoclonal IgG1 Ab against α4β7 integrin) has also been reported to be effective in some case reports and case series (23). A gastroenterology consultation is needed for toxicities above grade 2. Hydration, electrolyte replacement, and antidiarrheal agents should be considered for conservative care.

Gut microbiota

The gut microbiota has been actively studied as a factor affecting gastrointestinal toxicity (24,25). Particular bacterial populations in the gut have been found to be associated with ICI-induced colitis (26); moreover, repeated antibiotic use is considered a risk factor for ICI-related gastrointestinal toxicity. ICIs can increase gut permeability or damage the gut epithelium. Damage of epithelium can cause the gut microbiota to enter the bloodstream, thereby affecting and changing the immune system (24,27). Some cases of fecal microbiota transplantation have been reported in patients who did not respond to systemic steroids or infliximab (28).

Hepatitis

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

If aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is more than 2-fold higher than upper limit normal, tests related to hepatitis should be considered (29). Check other medications that cause hepatotoxicity and test for viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis should be performed. Image tests should be undertaken to identify liver metastasis or biliary obstruction. Liver biopsy can be useful in the diagnosis of immune medicated hepatitis (IMH). Liver biopsy shows lobular hepatitis with abundant infiltration by CD3+ or CD8+ T-lymphocytes (30). Fibrin-ring granulomas are not absolute pathognomonic findings but can be estimated by IMH if identified (31).

Incidence

The incidence of ICI-associated IMH has been reported to be approximately 2%–15% in clinical trial (32). Anti-CTLA-4 agents are known to show higher incidence of IMH than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. The incidence rates are higher in ICI combination therapy than in ICI monotherapy. Fortunately, the fatal case of IMH is relatively rare (17). Underlying chronic liver disease, such as chronic viral hepatitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, are considered as risk factors (33). Although data are few and not available about antiviral treatment, there is a case report of hepatitis B virus reactivation during the ICI treatment (34).

Treatment strategies

Systemic steroid is the basis for the treatment of IMH. If patients do not respond to steroids, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine should be initiated or added. However, infliximab (anti-TNF-α agent) should not be used because it can cause severe liver injury (35).

Kidney

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is the most common immune-related nephrotoxicity pattern (36). Most drug-induced AIN is caused by drug hypersensitivity reactions (37). However, immune-related AIN is similar to autoimmune disease (38). Renal biopsies show tubular injury rather than glomerular injury and include features such as edema, interstitial inflammation, and tubulitis. The renal interstitium shows infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, in addition to eosinophils and plasma cells. No deposition of specific immunoglobulins or complement fractions is observed. Urine studies often show sterile pyuria and white blood cell casts. Most other ICIs appear as typical tubulointerstitial nephritis, with only ipilimumab sometimes manifesting as nephrotic syndrome (39,40).

Incidence

Acute kidney injury (AKI), abnormal electrolytes, and severe AKI which need dialysis occur in approximately 2%, 1%, and 0.5% of cases, respectively (41). The incidence of AKI in ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy has been reported to be approximately 5% (42). However, the incidence rates mentioned above are based on clinical trials; there are case reports and unpublished cohort study data suggesting that approximately 10%–30% may occur in real clinical settings (43).

Treatment strategies

The basis of therapy is a systemic steroid in immune-related nephrotoxicity. If AKI occurs, clinicians should check the history of drug use and discontinue any medications that may cause kidney damage. If kidney damage occurs that requires dialysis, ICI should be immediately abrogated.

Mechanism

The cause of nephrotoxicity in ICI therapy can be explained by three mechanisms. First, the ICI breaks down peripheral tolerance to self-reactive T-lymphocytes (44). This phenomenon causes an autoimmune variant of interstitial nephritis. Second, the ICI activates drug-specific effector T-cells that are associated with the nephrotoxic drug (45). Several reports show that using proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is a risk factor for nephrotoxicity in ICI users. It has also been reported that stopping PPI or NSAID can restore renal function in mild AKI without stopping ICI. There are case reports that PPI or NSAIDs may cause nephrotoxicity, in patients who have used PPI or NSAID for a long time without any nephrotoxicity (46). Thirdly, using ICI increases pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can produce new auto-antibodies that can cause kidney damage (41).

Kidney transplant patients

Although data are lacking, the risk of ICI use is emphasized in patients undergoing kidney transplantation (9,47). In a case report, 30%–60% of kidney rejections were identified in renal transplant patients. Most patients with rejection did not respond to systemic steroids, and transplant kidney damage was progressing or continuing, even despite ICI cancellation. Therefore, ICI should not be used in kidney transplant patients.

ENDOCRINE ORGANS

Endocrine toxicity

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Endocrine toxicity is a very common irAE and includes hypophysitis, thyroid dysfunction, primary adrenal insufficiency, hypoparathyroidism, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (48). Hypophysitis and thyroid dysfunction are the most common endocrine toxicities (49). Endocrine toxicity is difficult to diagnose, because most symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, weight loss, general weakness, fatigue, mild cognitive dysfunction, hypotension, and headache, are nonspecific. Besides, the symptoms are similar to cancer progression or brain metastasis, resulting in delayed diagnosis. Delayed diagnosis can lead to fatal side effects, such as adrenal crisis, thyroid storm, severe hypocalcemia, and diabetic ketoacidosis (50). Endocrine toxicity is often diagnosed by routine laboratory surveillance under asymptomatic conditions. If the symptoms are caused by anti-CTLA-4 therapy, the side effects are dose-dependent (51). Hypophysitis, thyroid dysfunction, and adrenal insufficiency are significantly higher in ICI combination therapy than in ICI monotherapy (52).

Treatment strategies

While the treatment of other irAEs is based on systemic steroids, endocrine toxicity is based on the replacement of the deficient hormone. Moreover, other forms of immunomodulatory therapy are not recommended for treatment. Endocrine toxicity is often irreversible compared to other irAEs, because ICIs can cause permanent damage to the endocrine glands (53).

Hypophysis

Hypophysitis is more common with anti-CTLA-4 than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (52). Anti-CTLA-4 can cause direct damage to the pituitary gland, because pituitary cells express CTLA-4 (13). Usually, it occurs 4-10 weeks after ICI treatment (54). Toxicity occurs more often in men and older patients (55). Abnormal prolactin levels as well as growth hormone and posterior pituitary hormone deficiency is rare (56). Enlargement of the pituitary gland is rare in cases of ICI-induced hypophysitis (57). Therefore, diagnosis should be based on hormonal evaluation and clinical presentation, not image evaluation (58). Adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol tests, performed in the morning, are recommended for diagnosis. If the morning cortisol level is <350 nmol/L, the adrenocorticotropic hormone test should be conducted. If the morning cortisol level is <250 nmol/L or a random cortisol level is <150 nmol/L, hormone replacement therapy should be considered. In the presence of mass effect symptoms, such as a severe headache or visual field impairment, high-doses of glucocorticoids are considered (56).

Thyroid

Thyroid dysfunctions include hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and thyroiditis. Thyroid dysfunction is more common with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors than with anti-CTLA-4. Moreover, hyperthyroidism is more common with PD-1 inhibitors than PD-L1 inhibitors (59). ICI-related thyroid dysfunctions are more common in females. Thyroglobulin auto-antibodies and/or anti-thyroid peroxidase Abs are reported to be potential biomarkers. Regular monitoring of thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine is recommended for at least 5–6 cycles of ICI therapy (60). Levothyroxine treatment is recommended when thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are >10 mUI/L (61). Beta-blockers can be useful when symptoms of hyperthyroidism are observed (62).

HEMATOLOGIC COMPLICATIONS

Hematologic toxicities are rare irAEs. The risk of hematologic toxicities is lower in ICI than in cytotoxic chemotherapy. In a recent meta-analysis on PD-1 inhibitors, the incidence of all-grade anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia was 5%, 2%, 2%, and 1%, respectively (63). However, hematologic toxicities are fatal; for example, the mortality rate of immune thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic anemia exceeds 10% (64). Anti-CTLA-4 agent causes hematologic toxicity faster than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (65). Systemic steroids are the core of treatment, and transfusion should be performed as supportive care. However, research regarding hematologic complications is still scarce compared to other irAEs.

JOINT AND SKIN

Joint

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

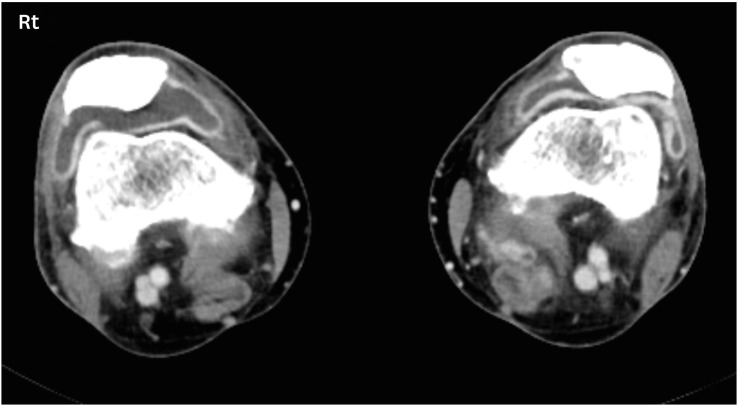

Clinical symptoms include joint swelling, warmth, erythema, or recently experienced joint pain. Erosive joint damage or change can progress rapidly. Evaluating joint erosion through sonography or magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in diagnosis (Fig. 2). If diagnosis is delayed and joint deformities develop, permanent motion limitation or chronic symptoms may occur. If a suspected symptom occurs, it is vital to early diagnose and treat the disease, in consultation with a rheumatologist. Compared to other irAEs, side effect is chronic and persistent and often requires long-term treatment.

Figure 2. Inflammatory arthritis related to immune checkpoint inhibitors on both knees; axial contrast computed tomography scan show moderate joint effusion of both knees (right > left) with associated synovial thickening.

Incidence

Representative irAEs associated with the joints are arthralgia, inflammatory arthritis, and tenosynovitis (66). In clinical trials, arthralgia is reported by 3%–7% and inflammatory arthritis by 1% of cases (67,68). High-risk factors are ICI combination therapy, long-term use of ICI, and previous occurrence of other irAEs. Occurrence of inflammatory arthritis is rare and later than other irAEs. Occasionally, inflammatory arthritis occurs after more than a year of stopping ICI treatment (69). In addition, compared to other symptoms, the diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis is often delayed because patients do not complain unless the doctor asks explicitly about joint pains.

Treatment strategies

Like in case of other irAEs, systemic steroids are used for treatment. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and intra-articular steroid injections may be helpful for supportive management (70). For side effects above grade 3, immunomodulatory therapy, such as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, can prevent permanent damage (71). Although detailed studies are still lacking, it has been reported that immunomodulatory therapy does not affect treatment response (72,73). Moreover, some studies report that persistent arthritis is associated with a better treatment response.

Skin

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

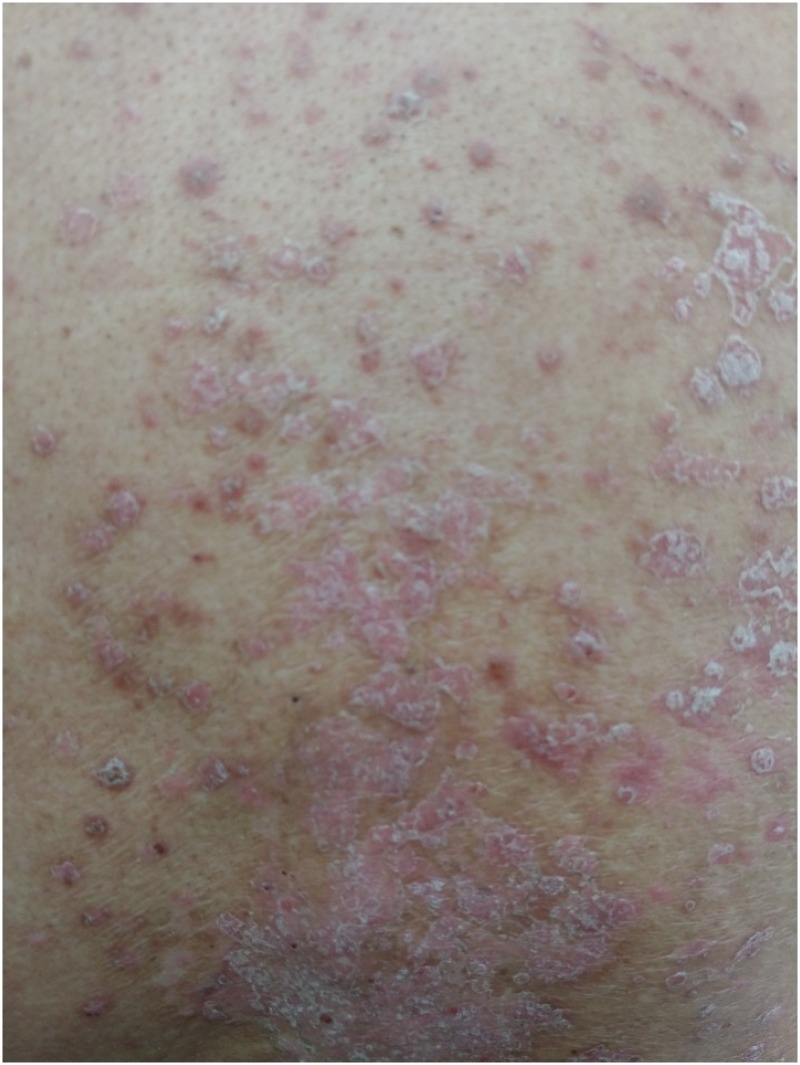

The skin is known to be the most affected by enhanced autoimmunity; thus, dermatologic toxicity is the most common irAEs (74). Common symptoms include rash, pruritus, and vitiligo. Rashes mainly localize to the trunk and extremities and may be combined with pruritus (75). The head, palms, and soles are often affected later, and the rash mostly manifests as erythematous macules, papules, and plaques (Fig. 3). Biopsy of the rash shows perivascular eosinophilic and leukocytic infiltrates (76). In severe cases, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, vasculitis, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms may occur (77). Sweet syndrome, cutaneous sarcoidosis, and bullous skin disorders have been reported very rarely (78).

Figure 3. Exacerbation of psoriasis under immune checkpoint inhibitors; plaque psoriasis with silvery scales on trunk.

Incidence

Dermatologic toxicity occurs faster than other irAEs (79); it is observed approximately 1 month after starting anti-CTLA-4 and approximately 2 months after starting PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (80). Dermatologic toxicity and severe toxicity are generally reported to occur in 25% and 2% of cases, respectively (81). Dermatologic toxicity occurs more frequently and severely with anti-CTLA-4 than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. In anti-CTLA-4 therapy, dermatologic toxicity may be dose-dependent. It is more common in ICI combination therapy, and the main symptoms are rash and pruritus. Among the various symptoms of dermatologic toxicity, rash and vitiligo are suspected to be preferable marker for ICI treatment response (8,82).

Treatment strategies

In most cases, dermatologic toxicity is mild and can be treated with topical corticosteroids or antihistamines (grade 1) (83). Gabapentin, a neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist, and doxepin may help at severe pruritus (84). For side effects above grade 2, the use of oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day is recommended. If the condition of the patient continues to worsen while using systemic steroids, the use of additional immunomodulatory therapy, such as infliximab, cyclophosphamide, and mycophenolate mofetil, should be considered.

NERVOUS SYSTEM

Neurotoxicity

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

ICI-related neurotoxicity can be classified into inflammatory (encephalitis, myelitis, vasculitis, and meningitis) and peripheral neuromuscular autoimmune disorders (myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barre syndrome). If ICI-related neurotoxicity is suspected, prompt work-up should be performed and discontinuation of the ICIs should be considered. Diagnosis must be done to differentiate between spinal cord compression, intra-cerebral metastases, and bacterial meningitis. In order to exclude bacterial meningitis in patients with fever or patients who are immuno-compromised, an urgent lumbar puncture is need. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies help diagnose peripheral neuropathies, and nerve biopsy helps diagnose vasculitis. Neurological history and physical examination may be helpful for diagnosis; therefore, early consultation with a specialized neurologist is necessary (85).

Incidence

The incidence of ICI-related neurotoxicity is reported as 1% in the clinical trial, but it is fatal (3). As it is directly related to the quality of life, patients may give up additional chemotherapy if they experience neurological sequelae. ICI-related neurotoxicity mostly occurs within 3 months of drug initiation. Patterns of neurotoxicity are different depending on the ICIs used (86). Neuromuscular junction dysfunction (myasthenia gravis), non-infectious encephalitis, and myelitis occur more commonly with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors than anti-CTLA-4 agents. In contrast, Guillain-Barré syndrome and non-infectious meningitis occur more commonly with anti-CTLA-4 agents. It has been reported that adverse effects are more common with ipilimumab–nivolumab combination therapy than with monotherapy (87). Although sufficient data are lacking, some studies have reported that progression-free and overall survival are much longer in patients with ICI-related neurotoxicity (87,88). The mechanism of neurotoxicity is still unknown, but it is presumed to be caused by sub-perineural edema and inflammation of endoneurial microvessels (89).

Treatment strategies

The treatment of choice is a systemic steroid. If the symptoms progress, systemic steroids should be started immediately (90). If steroid therapy has been initiated, the dose should be maintained until an observation of response. It should also be applied if there is a concern about the use of steroids due to other underlying diseases or factors. If respiratory muscles are involved, the intensive care unit and ventilator care may be necessary. In the absence of a steroid response, plasmapheresis, administration of intravenous immunoglobulin, and immune modulators, such as infliximab, mycophenolate, and cyclosporine, may be considered (87).

Myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia gravis is the most lethal form of ICI-related neurotoxicity. Unlike other ICI-related neurotoxicities, it occurs within a month of drug use (3). Myasthenia gravis is frequently accompanied by myocarditis and myositis (91). Unlike general myasthenia gravis, the test for acetylcholinesterase receptor Ab is frequently negative in this form of myasthenia gravis (92). Myasthenia gravis may cause an emergency that requires intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. Approximately 20% of patients with myasthenia gravis die, and the fatality rate is increased when the respiratory muscles are affected. High dose corticosteroids, plasma exchange and/or intravenous immunoglobulins are considered in fatal cases (93).

Cognitive disorders

ICI-related neurotoxicity has been focused on acute patterns and diseases. However, ICIs therapy is also suspected of being involved in causing the various aspects of chronic neurotoxicity, including cognitive disorders, fatigue, and mood disorders. In preclinical animal studies, ICIs can pass through the blood-brain barrier (94). ICIs can also change microglial activation and the levels of cytokines and chemokines in the brain (95). This change has been mainly demonstrated in the hippocampus, the center of cognitive function. Cognitive function and mood disorders are important factors that are directly linked to quality of life; often, this toxicity is neglected. Thus, further research is needed regarding cognitive disorders, fatigue, and mood disorders (96).

OCULAR SYSTEM

Ocular toxicities are known to be rare irAEs, with less than 1% of occurrence (97). The most common ICI-related ocular toxicity is uveitis. Most cases are bilateral and appear as anterior uveitis or pan-uveitis (98). Ocular toxicities occur within 6 months of using ICIs. Anti-CTLA-4 agents showed a higher incidence and severity of ocular toxicity than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. ICIs induce more ocular toxicities than cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens (99). ICI-related ocular toxicity occurs more often in melanoma than other solid cancers. This observation may be explained through the cross-reactivity between malignant melanoma cells and normal choroidal melanocytes (100). Uveitis, especially in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada like uveitis, is suspected to be a marker for a favor treatment response (101). Several cases have been reported that led to permanent loss of vision. Therefore, ophthalmic evaluation should be considered immediately if symptoms, such as worsening vision, floaters, or conjunctival injection, are detected (102). Uveitis can be easily treated with topical steroids, but systemic steroids should be considered when severity is high.

THORAX

Heart

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

ICI-related cardiotoxicity is relatively rare. However, it is life-threatening and fatal (3). ICI-related cardiotoxicity includes myocarditis, arrhythmias, conduction disease, acute coronary syndrome, congestive heart failure, and pericardial disease. The most common ICI-related cardiotoxicity is myocarditis. Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms, laboratory findings and image tool, such as cardiac enzymes (troponin and creatinine kinases), echocardiogram, and electrocardiogram (103). Several studies report the usefulness of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, although it is still controversial (104). Endomyocardial biopsy may be helpful for diagnosis, but it is an invasive procedure (105). Histologically, CD8+ T-cell and CD68+ macrophage, but not B-cell, infiltration is observed (106). Many cases are asymptomatic, and the clinician's awareness about cardiotoxicity is low (107). Therefore, attention to cardiotoxicity and efforts in cardiovascular monitoring are needed (108).

Incidence

The incidence of ICI-related myocarditis is known to be 0.09%–2.4% (109,110). However, the fatality rate is approximately 27%–60%, making ICI-related myocarditis the most dangerous irAE (91,111). The incidence and fatality rates are higher in ICI combination therapy than in ICI monotherapy (110). For example, ipilimumab–nivolumab combination therapy reported a fatality rate of 60% in myocarditis. In addition, a combination trial of ICIs and antiangiogenic agents, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (tyrosine kinase) inhibitors, has recently attracted attention, so cardiotoxicity has been increasingly an issue of concern. The time of occurrence varies, but fatal myocarditis usually occurs within a month of the first cycle of ICI infusion (109).

Treatment strategies

Cardiotoxicity has a significantly higher mortality rate than other irAEs, and it is recommended that ICIs are discontinued if cardiotoxicity is suspected. Systemic steroids are recommended for initial therapy, and 1 g per day of intravenous therapy should be considered if hemodynamic impairments are present (104). In steroid-refractory myocarditis, mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus should be considered (35,112). Recently, antithymocyte globulin, abatacept (CTLA-4 agonist), and alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 Ab) have been used for the treatment of steroid-refractory myocarditis (113,114). If the left ventricular ejection fraction is less than 50%, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors may be useful (115). Unlike other side effects, the re-initiation of ICIs is reported to be extremely dangerous (116).

Mechanism

The mechanism of cardiotoxicity is unknown. The presumed mechanism is that the PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways have a cardioprotective mechanism (especially T-cell-mediated inflammation), and ICIs disrupt immune tolerance in the heart (117). This hypothesis is based on the observation that PD-L1 expression in cardiomyocytes is upregulated in cardiac disease or injury (14). Postmortem analysis in ICI-related fatal myocarditis cases showed an increase in cytotoxic T-cells and macrophages. Dilated cardiomyopathy or autoimmune myocarditis has been observed in PD-1 knockout mouse models (118,119). Moreover, severe myocarditis with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte infiltration has been reported in a CTLA-4 knockout mouse models (120). In contrast, some reports suggest that cardiotoxicity occurs because of shared Ags and epitopes among the heart, muscle, and tumor cells (109).

Lung

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Symptoms involving the lungs are very diverse and nonspecific, and some patients do not experience respiratory symptoms (121). It is crucial to exclude infections in diagnosis; thus, bronchoscopy or bronchoalveolar lavage may be helpful for differential diagnosis. However, no specific histologic findings are available yet. In addition, chest imaging and computed tomography are essential for diagnosis and detection. ICI-related pneumonitis exhibits a variety of imaging patterns, such as organizing pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, acute interstitial pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, bronchiolitis, and radiation recall (122). The dominant radiologic pattern is organizing pneumonia.

Incidence

ICI-related pneumonitis is rarer than other irAEs, but it is the most fatal irAE associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy. ICI-related pneumonitis accounts for 35% of deaths due to PD-1 / PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy (3). The overall incidence rate of ICI-related pneumonitis observed in clinical trials with ICI monotherapy is 2.5%–5.0%, and that with ICI combination therapy ranges 7%–10% (121). As clinical trials target healthy patients who have no underlying lung disease or autoimmune disease, the incidence in real world data ranges from 7%–19% (123). Moreover, the incidence of ICI-related pneumonitis is higher in non-small cell lung cancer than in other tumors (124). Further, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors showed a higher incidence and severity of pulmonary toxicity than that shown by anti-CTLA-4 agents (15), and PD-1 inhibitors show a higher incidence and severity of pulmonary toxicity than do PD-L1 inhibitors (125). Underlying lung disease (interstitial lung disease, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and prior thoracic radiation are considered risk factors for ICI-related pneumonitis (126,127). The mean duration of onset is approximately 3 months (128).

Treatment strategies

The framework of treatment is similar to drug-related hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The basis of treatment is ICI cessation, systemic steroids, and immunosuppressive medications (129). It has been reported that, if ICIs are restarted, ICI-related pneumonitis can recur in 20% of cases (130). Moreover, even after accomplishment of systemic steroid treatment and absence of retrying ICI therapy, some patients experience recurrent pneumonitis (131).

CONCLUSION

ICIs can cause a variety of unexpected side effects throughout the whole body. IrAEs are sometimes nonspecific or ambiguous, such as cardiotoxicity and endocrine toxicity. An important point in the treatment of irAEs is early detection and diagnosis. It should be noted that all new symptoms after ICI initiation could be irAEs. Regular checkups, such as thyroid function tests or cardiac enzymes, need to be performed. The basis of most irAE treatments is the use of systemic steroids. However, an immune modulator may be used in the absence of steroid response. Multidisciplinary treatments under the supervision of specialists are essential, because the symptoms and treatment of irAEs may involve multiple organs.

Abbreviations

- AIN

acute interstitial nephritis

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IMH

immune medicated hepatitis

- irAE

immune-related adverse effect

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Choi J, Lee SY.

- Supervision: Lee SY.

- Writing - original draft: Choi J, Lee SY.

- Writing - review & editing: Choi J, Lee SY.

References

- 1.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang J, Yu JX, Hubbard-Lucey VM, Neftelinov ST, Hodge JP, Lin Y. Trial watch: The clinical trial landscape for PD1/PDL1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:854–855. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S, Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, Das S, Beckermann KE, Ha L, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1721–1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Y, Ruddy KJ, Tsuji S, Hong N, Liu H, Shah N, Jiang G. Coverage evaluation of CTCAE for capturing the immune-related adverse events leveraging text mining technologies. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2019;2019:771–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, Chau I, Ernstoff MS, Gardner JM, Ginex P, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haanen JB, Carbonnel F, Robert C, Kerr KM, Peters S, Larkin J, Jordan K ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv264–iv266. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, Zwinderman AH, Reitsma JB, Spuls PI, Luiten RM. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773–781. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deltombe C, Garandeau C, Renaudin K, Hourmant M. Severe allograft rejection and autoimmune hemolytic anemia after anti-PD1 therapy in a kidney transplanted patient. Transplantation. 2017;101:e291. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne EH, Fisher DE. Immune and molecular correlates in melanoma treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer. 2017;123:2143–2153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimbara S, Fujiwara Y, Iwama S, Ohashi K, Kuchiba A, Arima H, Yamazaki N, Kitano S, Yamamoto N, Ohe Y. Association of antithyroglobulin antibodies with the development of thyroid dysfunction induced by nivolumab. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3583–3590. doi: 10.1111/cas.13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwama S, De Remigis A, Callahan MK, Slovin SF, Wolchok JD, Caturegli P. Pituitary expression of CTLA-4 mediates hypophysitis secondary to administration of CTLA-4 blocking antibody. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:230ra45. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baban B, Liu JY, Qin X, Weintraub NL, Mozaffari MS. Upregulation of programmed death-1 and its ligand in cardiac injury models: interaction with GADD153. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haanen JB, Carbonnel F, Robert C, Kerr KM, Peters S, Larkin J, Jordan K ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv119–iv142. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil C, Lotem M, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil C, Lotem M, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006) Lancet. 2017;390:1853–1862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31601-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Malet A, Antoni G, Collins M, Soularue E, Marthey L, Vaysse T, Coutzac C, Chaput N, Mateus C, Robert C, et al. Evolution and recurrence of gastrointestinal immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2019;106:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geukes Foppen MH, Rozeman EA, van Wilpe S, Postma C, Snaebjornsson P, van Thienen JV, van Leerdam ME, van den Heuvel M, Blank CU, van Dieren J, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open. 2018;3:e000278. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A, De Felice KM, Loftus EV, Jr, Khanna S. Systematic review: colitis associated with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:406–417. doi: 10.1111/apt.13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samaan MA, Pavlidis P, Papa S, Powell N, Irving PM. Gastrointestinal toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: from mechanisms to management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2018.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beniwal-Patel P, Matkowskyj K, Caldera F. Infliximab therapy for corticosteroid-resistant ipilimumab-induced colitis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:274. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.243.bwp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh AH, Ferman M, Brown MP, Andrews JM. Vedolizumab: a novel treatment for ipilimumab-induced colitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016216641. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Placencio-Hickok V, Guan M, Hendifar A, Salgia R. The gut microbiome and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: preclinical and clinical strategies. Clin Transl Med. 2019;8:9. doi: 10.1186/s40169-019-0225-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy S, Trinchieri G. Microbiota: a key orchestrator of cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:271–285. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubin K, Callahan MK, Ren B, Khanin R, Viale A, Ling L, No D, Gobourne A, Littmann E, Huttenhower C, et al. Intestinal microbiome analyses identify melanoma patients at risk for checkpoint-blockade-induced colitis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10391. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pezo RC, Wong M, Martin A. Impact of the gut microbiota on immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated toxicities. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819870911. doi: 10.1177/1756284819870911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Wiesnoski DH, Helmink BA, Gopalakrishnan V, Choi K, DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Abu-Sbeih H, Sanchez CA, Chang CC, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. Nat Med. 2018;24:1804–1808. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jennings JJ, Mandaliya R, Nakshabandi A, Lewis JH. Hepatotoxicity induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: a comprehensive review including current and alternative management strategies. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15:231–244. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2019.1574744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zen Y, Yeh MM. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a histology study of seven cases in comparison with autoimmune hepatitis and idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:965–973. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Martin E, Michot JM, Papouin B, Champiat S, Mateus C, Lambotte O, Roche B, Antonini TM, Coilly A, Laghouati S, et al. Characterization of liver injury induced by cancer immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1181–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, Lie P, Guo M, He J. Risk of hepatotoxicity in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1018–1028. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim KW, Ramaiya NH, Krajewski KM, Jagannathan JP, Tirumani SH, Srivastava A, Ibrahim N. Ipilimumab associated hepatitis: imaging and clinicopathologic findings. Invest New Drugs. 2013;31:1071–1077. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9939-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koksal AS, Toka B, Eminler AT, Hacibekiroglu I, Uslan MI, Parlak E. HBV-related acute hepatitis due to immune checkpoint inhibitors in a patient with malignant melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:3103–3104. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Thompson JA. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline summary. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:247–249. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perazella MA, Shirali AC. Nephrotoxicity of cancer immunotherapies: past, present and future. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:2039–2052. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018050488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paueksakon P, Fogo AB. Drug-induced nephropathies. Histopathology. 2017;70:94–108. doi: 10.1111/his.13064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marco T, Anna P, Annalisa T, Francesco M, Stefania SL, Stella D, Michele R, Marco T, Loreto G, Franco S. The mechanisms of acute interstitial nephritis in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919875549. doi: 10.1177/1758835919875549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mamlouk O, Selamet U, Machado S, Abdelrahim M, Glass WF, Tchakarov A, Gaber L, Lahoti A, Workeneh B, Chen S, et al. Nephrotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors beyond tubulointerstitial nephritis: single-center experience. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:2. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0478-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izzedine H, Gueutin V, Gharbi C, Mateus C, Robert C, Routier E, Thomas M, Baumelou A, Rouvier P. Kidney injuries related to ipilimumab. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:769–773. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manohar S, Kompotiatis P, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Herrmann J, Herrmann SM. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor treatment is associated with acute kidney injury and hypocalcemia: meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34:108–117. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cortazar FB, Marrone KA, Troxell ML, Ralto KM, Hoenig MP, Brahmer JR, Le DT, Lipson EJ, Glezerman IG, Wolchok J, et al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2016;90:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wanchoo R, Karam S, Uppal NN, Barta VS, Deray G, Devoe C, Launay-Vacher V, Jhaveri KD Cancer and Kidney International Network Workgroup on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Adverse renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a narrative review. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45:160–169. doi: 10.1159/000455014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes J, Vudattu N, Sznol M, Gettinger S, Kluger H, Lupsa B, Herold KC. Precipitation of autoimmune diabetes with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e55–e57. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirali AC, Perazella MA, Gettinger S. Association of acute interstitial nephritis with programmed cell death 1 inhibitor therapy in lung cancer patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:287–291. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koda R, Watanabe H, Tsuchida M, Iino N, Suzuki K, Hasegawa G, Imai N, Narita I. Immune checkpoint inhibitor (nivolumab)-associated kidney injury and the importance of recognizing concomitant medications known to cause acute tubulointerstitial nephritis: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:48. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-0848-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maggiore U, Pascual J. The bad and the good news on cancer immunotherapy: Implications for organ transplant recipients. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23:312–316. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang LS, Barroso-Sousa R, Tolaney SM, Hodi FS, Kaiser UB, Min L. Endocrine toxicity of cancer immunotherapy targeting immune checkpoints. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:17–65. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.González-Rodríguez E, Rodríguez-Abreu D Spanish Group for Cancer Immuno-Biotherapy (GETICA) Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Review and management of endocrine adverse events. Oncologist. 2016;21:804–816. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boasberg P, Hamid O, O'Day S. Ipilimumab: unleashing the power of the immune system through CTLA-4 blockade. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:440–449. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Filette J, Andreescu CE, Cools F, Bravenboer B, Velkeniers B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endocrine-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Horm Metab Res. 2019;51:145–156. doi: 10.1055/a-0843-3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sznol M, Postow MA, Davies MJ, Pavlick AC, Plimack ER, Shaheen M, Veloski C, Robert C. Endocrine-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade and expert insights on their management. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;58:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caturegli P, Di Dalmazi G, Lombardi M, Grosso F, Larman HB, Larman T, Taverna G, Cosottini M, Lupi I. Hypophysitis secondary to cytotoxic t-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 blockade: Insights into pathogenesis from an autopsy series. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:3225–3235. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faje AT, Sullivan R, Lawrence D, Tritos NA, Fadden R, Klibanski A, Nachtigall L. Ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis: a detailed longitudinal analysis in a large cohort of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4078–4085. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dillard T, Yedinak CG, Alumkal J, Fleseriu M. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy associated autoimmune hypophysitis: serious immune related adverse events across a spectrum of cancer subtypes. Pituitary. 2010;13:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s11102-009-0193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blansfield JA, Beck KE, Tran K, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Haworth LR, Levy C, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 blockage can induce autoimmune hypophysitis in patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cancer. J Immunother. 2005;28:593–598. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000178913.41256.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ntali G, Kassi E, Alevizaki M. Endocrine sequelae of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Hormones (Athens) 2017;16:341–350. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barroso-Sousa R, Barry WT, Garrido-Castro AC, Hodi FS, Min L, Krop IE, Tolaney SM. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:173–182. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barroso-Sousa R, Ott PA, Hodi FS, Kaiser UB, Tolaney SM, Min L. Endocrine dysfunction induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Practical recommendations for diagnosis and clinical management. Cancer. 2018;124:1111–1121. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Illouz F, Briet C, Cloix L, Le Corre Y, Baize N, Urban T, Martin L, Rodien P. Endocrine toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: essential crosstalk between endocrinologists and oncologists. Cancer Med. 2017;6:1923–1929. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Filette J, Jansen Y, Schreuer M, Everaert H, Velkeniers B, Neyns B, Bravenboer B. Incidence of thyroid-related adverse events in melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:4431–4439. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sui JD, Wang Y, Wan Y, Wu YZ. Risk of hematologic toxicities with programmed cell death-1 inhibitors in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of current studies. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:1645–1657. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S167077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calvo R. Hematological side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the example of immune-related thrombocytopenia. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:454. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis EJ, Salem JE, Young A, Green JR, Ferrell PB, Ancell KK, Lebrun-Vignes B, Moslehi JJ, Johnson DB. Hematologic complications of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncologist. 2019;24:584–588. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jagpal A, Choudhary G, Chokr J. Severe arthritis and tenosynovitis caused by immune checkpoint blockade therapy with pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2019;32:419–421. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2019.1588654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Hamid O, Robert C, Hodi FS, Schachter J, Pavlick AC, Lewis KD, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:908–918. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, Khan N, Wang Z, Boyce L, Korenstein D. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cappelli LC, Naidoo J, Bingham CO, 3rd, Shah AA. Inflammatory arthritis due to immune checkpoint inhibitors: challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:5–8. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naidoo J, Cappelli LC, Forde PM, Marrone KA, Lipson EJ, Hammers HJ, Sharfman WH, Le DT, Baer AN, Shah AA, et al. Inflammatory arthritis: a newly recognized adverse event of immune checkpoint blockade. Oncologist. 2017;22:627–630. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, Bingham CO, 3rd, Brogdon C, Dadu R, Hamad L, Kim S, Lacouture ME, LeBoeuf NR, et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Braaten TJ, Brahmer JR, Forde PM, Le D, Lipson EJ, Naidoo J, Schollenberger M, Zheng L, Bingham Rd CO, Shah AA, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis persists after immunotherapy cessation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, Momtaz P, Postow MA, Callahan MK, Carvajal RD, Dickson MA, D'Angelo SP, Woo KM, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3193–3198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jaber SH, Cowen EW, Haworth LR, Booher SL, Berman DM, Rosenberg SA, Hwang ST. Skin reactions in a subset of patients with stage IV melanoma treated with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 monoclonal antibody as a single agent. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:166–172. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, Hellmann MD, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Motzer RJ, Wu S, Busam KJ, Wolchok JD, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lacouture ME, Wolchok JD, Yosipovitch G, Kähler KC, Busam KJ, Hauschild A. Ipilimumab in patients with cancer and the management of dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Voskens CJ, Goldinger SM, Loquai C, Robert C, Kaehler KC, Berking C, Bergmann T, Bockmeyer CL, Eigentler T, Fluck M, et al. The price of tumor control: an analysis of rare side effects of anti-CTLA-4 therapy in metastatic melanoma from the ipilimumab network. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, Busam K, Cunningham J, Page DB, Postow MA, Weinstein A, Lucas AS, Ciccolini KT, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:383–389. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, Drucker C, Diab A, Hymes SR, Duvic M, Hwu WJ, Wargo JA, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158–176. doi: 10.1111/cup.12858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tarhini A. Immune-mediated adverse events associated with ipilimumab CTLA-4 blockade therapy: the underlying mechanisms and clinical management. Scientifica (Cairo) 2013;2013:857519. doi: 10.1155/2013/857519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Minkis K, Garden BC, Wu S, Pulitzer MP, Lacouture ME. The risk of rash associated with ipilimumab in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e121–e128. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, Richards A, Gibney G, Weber JS. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:886–894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zimmer L, Vaubel J, Livingstone E, Schadendorf D. Side effects of systemic oncological therapies in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:475–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Collins LK, Chapman MS, Carter JB, Samie FH. Cutaneous adverse effects of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spain L, Tippu Z, Larkin JM, Carr A, Turajlic S. How we treat neurological toxicity from immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO Open. 2019;4:e000540. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johnson DB, Manouchehri A, Haugh AM, Quach HT, Balko JM, Lebrun-Vignes B, Mammen A, Moslehi JJ, Salem JE. Neurologic toxicity associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance study. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:134. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spain L, Walls G, Julve M, O'Meara K, Schmid T, Kalaitzaki E, Turajlic S, Gore M, Rees J, Larkin J. Neurotoxicity from immune-checkpoint inhibition in the treatment of melanoma: a single centre experience and review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:377–385. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cuzzubbo S, Javeri F, Tissier M, Roumi A, Barlog C, Doridam J, Lebbe C, Belin C, Ursu R, Carpentier AF. Neurological adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: review of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 2017;73:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Manousakis G, Koch J, Sommerville RB, El-Dokla A, Harms MB, Al-Lozi MT, Schmidt RE, Pestronk A. Multifocal radiculoneuropathy during ipilimumab treatment of melanoma. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48:440–444. doi: 10.1002/mus.23830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Touat M, Talmasov D, Ricard D, Psimaras D. Neurological toxicities associated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:659–668. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moslehi JJ, Salem JE, Sosman JA, Lebrun-Vignes B, Johnson DB. Increased reporting of fatal immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Lancet. 2018;391:933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30533-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anquetil C, Salem JE, Lebrun-Vignes B, Johnson DB, Mammen AL, Stenzel W, Léonard-Louis S, Benveniste O, Moslehi JJ, Allenbach Y. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myositis. Circulation. 2018;138:743–745. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Becquart O, Lacotte J, Malissart P, Nadal J, Lesage C, Guillot B, Du Thanh A. Myasthenia gravis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother. 2019;42:309–312. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reardon DA, Gokhale PC, Klein SR, Ligon KL, Rodig SJ, Ramkissoon SH, Jones KL, Conway AS, Liao X, Zhou J, et al. Glioblastoma eradication following immune checkpoint blockade in an orthotopic, immunocompetent model. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:124–135. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McGinnis GJ, Friedman D, Young KH, Torres ER, Thomas CR, Jr, Gough MJ, Raber J. Neuroinflammatory and cognitive consequences of combined radiation and immunotherapy in a novel preclinical model. Oncotarget. 2017;8:9155–9173. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McGinnis GJ, Raber J. CNS side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: preclinical models, genetics and multimodality therapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:929–941. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Antoun J, Titah C, Cochereau I. Ocular and orbital side-effects of checkpoint inhibitors: a review article. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:288–294. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sun MM, Levinson RD, Filipowicz A, Anesi S, Kaplan HJ, Wang W, Goldstein DA, Gangaputra S, Swan RT, Sen HN, et al. Uveitis in patients treated with CTLA-4 and PD-1 checkpoint blockade inhibition. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019 doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1577978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abdel-Rahman O, Oweira H, Petrausch U, Helbling D, Schmidt J, Mannhart M, Mehrabi A, Schöb O, Giryes A. Immune-related ocular toxicities in solid tumor patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2017;17:387–394. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2017.1296765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lavezzo MM, Sakata VM, Morita C, Rodriguez EE, Abdallah SF, da Silva FT, Hirata CE, Yamamoto JH. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: review of a rare autoimmune disease targeting antigens of melanocytes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Diem S, Keller F, Rüesch R, Maillard SA, Speiser DE, Dummer R, Siano M, Urner-Bloch U, Goldinger SM, Flatz L. Pembrolizumab-triggered uveitis: An additional surrogate marker for responders in melanoma immunotherapy? J Immunother. 2016;39:379–382. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Conrady CD, Larochelle M, Pecen P, Palestine A, Shakoor A, Singh A. Checkpoint inhibitor-induced uveitis: a case series. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256:187–191. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Michel L, Rassaf T, Totzeck M. Cardiotoxicity from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;25:100420. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2019.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ganatra S, Neilan TG. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Oncologist. 2018;23:879–886. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bonaca MP, Olenchock BA, Salem JE, Wiviott SD, Ederhy S, Cohen A, Stewart GC, Choueiri TK, Di Carli M, Allenbach Y, et al. Myocarditis in the setting of cancer therapeutics: Proposed case definitions for emerging clinical syndromes in cardio-oncology. Circulation. 2019;140:80–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang S, Asnani A. Cardiotoxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018;42:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Neilan TG, Rothenberg ML, Amiri-Kordestani L, Sullivan RJ, Steingart RM, Gregory W, Hariharan S, Hammad TA, Lindenfeld J, Murphy MJ, et al. Myocarditis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an expert consensus on data gaps and a call to action. Oncologist. 2018;23:874–878. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Totzeck M, Schuler M, Stuschke M, Heusch G, Rassaf T. Cardio-oncology - strategies for management of cancer-therapy related cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2019;280:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias S, Gorham J, Xu Y, Hicks M, Puzanov I, Alexander MR, Bloomer TL, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1749–1755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen JV, Nohria A, Reynolds KL, Heinzerling LM, Sullivan RJ, Damrongwatanasuk R, Chen CL, Gupta D, et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1755–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Escudier M, Cautela J, Malissen N, Ancedy Y, Orabona M, Pinto J, Monestier S, Grob JJ, Scemama U, Jacquier A, et al. Clinical features, management, and outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2017;136:2085–2087. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Arangalage D, Delyon J, Lermuzeaux M, Ekpe K, Ederhy S, Pages C, Lebbé C. Survival after fulminant myocarditis induced by immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:683–684. doi: 10.7326/L17-0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Salem JE, Allenbach Y, Vozy A, Brechot N, Johnson DB, Moslehi JJ, Kerneis M. Abatacept for severe immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2377–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1901677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Esfahani K, Buhlaiga N, Thébault P, Lapointe R, Johnson NA, Miller WH., Jr Alemtuzumab for immune-related myocarditis due to PD-1 therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2375–2376. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1903064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lyon AR, Yousaf N, Battisti NM, Moslehi J, Larkin J. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and cardiovascular toxicity. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e447–e458. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tajmir-Riahi A, Bergmann T, Schmid M, Agaimy A, Schuler G, Heinzerling L. Life-threatening autoimmune cardiomyopathy reproducibly induced in a patient by checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Immunother. 2018;41:35–38. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tajiri K, Ieda M. Cardiac complications in immune checkpoint inhibition therapy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:3. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang J, Okazaki IM, Yoshida T, Chikuma S, Kato Y, Nakaki F, Hiai H, Honjo T, Okazaki T. PD-1 deficiency results in the development of fatal myocarditis in MRL mice. Int Immunol. 2010;22:443–452. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nishimura H, Okazaki T, Tanaka Y, Nakatani K, Hara M, Matsumori A, Sasayama S, Mizoguchi A, Hiai H, Minato N, et al. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science. 2001;291:319–322. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, Thompson CB, Griesser H, Mak TW. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4 . Science. 1995;270:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, Iyriboz T, Halpenny D, Cunningham J, Chaft JE, Segal NH, Callahan MK, Lesokhin AM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:709–717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kalisz KR, Ramaiya NH, Laukamp KR, Gupta A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy-related pneumonitis: patterns and management. Radiographics. 2019;39:1923–1937. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019190036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Suresh K, Naidoo J, Lin CT, Danoff S. Immune checkpoint immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: benefits and pulmonary toxicities. Chest. 2018;154:1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ma K, Lu Y, Jiang S, Tang J, Li X, Zhang Y. The relative risk and incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitors related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1430. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sternschein R, Moll M, Ng J, D'Ambrosio C. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis. Incidence, risk factors, and clinical and radiographic features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:951–953. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0525RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cho JY, Kim J, Lee JS, Kim YJ, Kim SH, Lee YJ, Cho YJ, Yoon HI, Lee JH, Lee CT, et al. Characteristics, incidence, and risk factors of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;125:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K, Veruttipong D, Goldman JW, Formenti SC, Garon EB, Lee P. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:895–903. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30380-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]