Abstract

Aim

Biochemical relapse-free survival (bRFS) rate is determined by a cohort of Mexican patients (n = 595) with prostate cancer who received treatment with external radiotherapy.

Background

Patients with prostate cancer were collected from CMN Siglo XXI (IMSS), CMN 20 de Noviembre (ISSSTE), and Hospital General de México (HGM). For the IMSS, 173 patients that are treated with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) and 250 with SBRT, for the ISSSTE 57 patients are treated with 3D-CRT and on the HGM 115 patients are managed with intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). The percentage of patients by risk group is: low 11.1%, intermediate 35.1% and high 53.8%. The average follow-up is 39 months, and the Phoenix criterion was used to determine the bRFS.

Materials and methods

The Kaplan–Meier technique for the construction of the survival curves and, the Cox proportional hazards to model the cofactors.

Results

(a) The bRFS rates obtained are 95.9% for the SBRT (7 Gy fx, IMSS), 94.6% for the 3D-CRT (1.8 Gy fx, IMSS), 91.3% to the 3D-CRT (2.65 Gy fx, IMSS), 89.1% for the SBRT (7.25 Gy fx, IMSS), 88.7% for the IMRT (1.8 Gy fx, HGM) %, and 87.7% for the 3D-CRT (1.8 Gy fx, ISSSTE). (b) There is no statistically significant difference in the bRFS rates by fractionation scheme, c) Although the numerical difference in the bRFS rate per risk group is 95.5%, 93.8% and 89.1% for low, intermediate and high risk, respectively, these are not statistically significant.

Conclusions

The RT techniques for the treatment of PCa are statistically equivalent with respect to the bRFS rate. This paper confirms that the bRFS rates of Mexican PCa patients who were treated with conventional vs. hypofractionated schemes do not differ significantly.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Biochemical relapse-free survival, 3D-CRT, Hypofractionation, SBRT

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cancer is the second leading cause of death in the world; in 2015 this disease produced 8.8 million deaths worldwide, of which about 70% are registered in middle and low income countries.1

In Mexico, 160,000 new cases of cancer are presented every year,2 this disease being the third cause of death in the country, only after cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus.3 Prostate cancer PCa has become a public health problem in Mexico, as it is the leading cause of death in the male population. The figures show that about 7,000 men die each year from this disease, and it is estimated that every year between 21,000 and 25,000 new cases of PCa are reported.4

For the clinical stage of PCa, the TNM classification of the AJCC is used,5 which employs the criteria; tumor, lymph node involvement and metastatic disease. This classification is used only for the purposes of clinical stage, since the classification by risk groups is currently employed5: low, intermediate and high. In fact, the low risk group are patients with PSA < 10, Gleason <7 and <50% of the prostate lobe involved (<T2b). Intermediate risk group is defined as patients with a PSA 10–20, Gleason 7 and >50% of the lobe of the prostate affected. The high risk group are patients with PSA >20, Gleason >7 and with extra-prostatic extension (T3).

The treatment for PCa is carried out based on the classification of risk groups.6 Patients with low risk with life expectancy of less than 5 years are under active surveillance, and in those with expectations of more than 5 years there are different options: radical prostatectomy with lymph node dissection (QX), external radiotherapy or brachytherapy. In patients with intermediate and high risk, the options are radical prostatectomy with lymph node dissection, radical external radiotherapy, or external radiotherapy followed by brachytherapy, and hormonal therapy (HT). Also, for these last risk groups the guidelines consider the concomitant androgenic deprivation for increased biochemical control.

Prostatectomy with lymphadenectomy is the surgical treatment indicated in the clinical practice guidelines,7,8 which consists in removing the prostate, seminal vesicles and lymph node dissection, the advantages being: better locoregional control, pathological staging, elimination of resistant clones to radiation and better response to hormone therapy without a primary tumor in case of progression or metastasis.

In the case of RT, initial studies showed that for absorbed doses on the interval of 64−70 Gy, there are good local control rates.5 Other studies were conducted in order to increase the dose from 74 to 80 Gy, with a 10–15% benefit of PSA control, with no impact on overall survival. Finally, different clinical studies show that RT improves the bRFS without increasing toxicity. For example, the 10-year bRFS rates in 393 patients with PCa are reported in the Zietman study9; 83% for patients who received doses ∼79.2 compared with 68% of patients with doses administered <70 Gy. Similarly, Al-Mamgani followed up 669 patients,10 where the bRFS rate was 54% for patients who had received doses ∼78 Gy, and 47% in patients with doses below 70 Gy. Subsequently, Dearnaley11 demonstrates in his study conducted with 843 patients that doses >70 Gy improve the bRFS rate at 10 years, since the bRFS is 72% in patients with administered doses >70 Gy contrasted with 61% with doses <70 Gy.

On the other hand, the mechanism of action whereby HT reduces intracellular concentrations of testosterone,6 induces apoptosis, which decreases tumor volume, increasing local control and decreasing the probability of metastatic disease.

In fact, RT is one of the main treatment options for PCa; however, it is well known that there are biological factors that influence the response of tissues to treatment, such as radiosensitivity, repopulation, reoxygenation and redistribution.12 What is even more, the PCa is characterized by being a tissue with repopulation and slow repair that is expressed with a low value of α/β ∼1.5 Gy.13 In neoplasms with low values of α/β it is considered that hypofractionation schemes can favor cell death and, therefore, the local control of the disease. In this scenario, tolerance and type of tissues located in the treatment area should be considered, since there is a risk to develop greater toxicity. In the case of the conventional treatment schemes to treat PCa with external RT, total absorbed dose employed is in the order of 70−80 Gy, which is administered from Monday to Friday in a period of 6–8 weeks, with doses of 1.8–2 Gy fx; while in the hypofractionated treatments doses >2.0 Gy fx are used,14 where these are divided into: (a) moderate hypofractionation which uses 2.4–3 Gy fx and, (b) ultra-hypofractionated dose >3 Gy fx, giving 5–12 fractions. The advantage of the hypofractionation schemes, is that the total treatment time and the number of fractions are reduced, so that the patient receives treatment in 1–2 weeks instead of 8.

In recent years, there has been a rapid increase in CaP treatments with hypofractioned external RT with the SBRT technique.15,16 However, although there are results in several countries regarding the radiobiological equivalence of PCa treatment schemes, it is convenient to verify with radioepidemiological data the effectiveness of the different RT treatment schemes and techniques for the Mexican male population, i.e. the bRFS and alpha/beta determined for Mexican population of PCa treated with RT techniques, because there are no such studies in our country.17

The aims of this work are to determine and compare the bRFS rate of different RT treatment schemes in Mexican patients with PCa, treated in three Hospital Institutions of Mexico City. The RT techniques used in the patients were 3D-CRT, IMRT and SBRT. The survival values obtained in this study will be taken as a reference to perform a radiobiological optimization in a future phase, and for the determination of the α/β for the Mexican population treated with RT techniques.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Cohort of patients with PCa treated with RT

This work was carried out with 595 PCa patients treated with external RT in three different Hospitals of Mexico City. The distribution of the patients, as well as the different schemes and treatment techniques used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cohort of PCa patients treated with RT.

| Hospital | No. patients | Percentage | Technique | Dose fx (Gy) | No fractions | Total dose (Gy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMSS | 93 | 15.6% | 3D-CRT | 1.8 | 39–44 | 70.2–79.2 |

| 80 | 13.4% | 3D-CRT | 2.65 | 25 | 66.25 | |

| 121 | 20.3% | SBRT | 7.0 | 5 | 35.0 | |

| 129 | 21.7% | SBRT | 7.25 | 5 | 36.25 | |

| ISSSTE | 57 | 19.3% | 3D-CRT | 1.8–2.0 | 30–41 | 60–73.8 |

| HGM | 115 | 9.6% | IMRT | 1.8 | 42–44 | 75.6–79.2 |

To determine the bRFS, the Phoenix criterion is used18: By definition, an increase of 2 ng/ml or more above the nadir PSA is considered as a biochemical failure.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The non-parametric method of Kaplan–Meier (K–M) is used to estimate the median survival.19 The analysis assumes that the mechanisms of the event and censorship are statistically independent; that is, the censored individuals are subject to the same probability of the event as the uncensored ones. Patients are considered on the following accounts:

-

i)

Because the study was completed before the event appeared,

-

ii)

the patient decided to leave the study,

-

iii)

the patient was lost for some other reason,

-

iv)

due to death not related to the investigation and so on.

To test the survival functions, the Mantel-Cox, Breslow and Tarone-Ware tests were carried out.

On the other hand, because in the K–M analysis it only considers the relationship of one variable over time, the Cox proportional hazards model is used to take into account different possibly confusing covariates, such as the treatment scheme, technique employed, the risk group, etc. A central element to interpret this method is the hazard ratio (HR), which is no more than the ratio of instantaneous hazard rates between the interest and control group.20

Finally, an important aspect in the models is their validation, since their predictability must be measured, for example, by estimating their concordance between the observed ranges and the estimated or predicted survival times. This concordance statistic test summarizes the potential of the model to predict. Specifically, the concordance statistics is an estimator of the probability that for any couple of individuals, the ones with the shortest life span are the ones with the highest risk function. These pairs of individuals are considered in the calculation when they have failure times of both, and one of them fails before the censorship time of the other. Couples with both censored times, and when the survival time exceeds the other's censorship time, are not considered in the calculation of statistics. As for a model with good predictability, its concordance takes values greater than 0.7, while values around 0.5 have no prediction ability.

3. Results

(a) The bRFS rates of the patient cohort.

Table 2 shows the PSA RFS rates after treatment with external RT, for an average follow-up of 39 months, considering: the fractionation scheme, technique and treatment institution.

Table 2.

bRFS rates by institution, technique and treatment scheme.

| Hospital | No. patients | Technique | Dose fx (Gy) | No fractions | Total dose (Gy) | bRFS Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMSS | 93 | 3D-CRT | 1.8 | 39 - 44 | 70.2–79.2 | 94.6% |

| 80 | 3D-CRT | 2.66 | 25 | 66.25 | 91.3% | |

| 121 | SBRT | 7.0 | 5 | 35.0 | 95.9% | |

| 129 | SBRT | 7.25 | 5 | 36.25 | 89.1% | |

| ISSSTE | 57 | 3D-CRT | 1.8 - 2.0 | 30 - 41 | 60–73.8 | 87.7% |

| HGM | 115 | IMRT | 1.8 | 42 - 44 | 75.6–79.2 | 88.7% |

| Global | 595 | 91.4% |

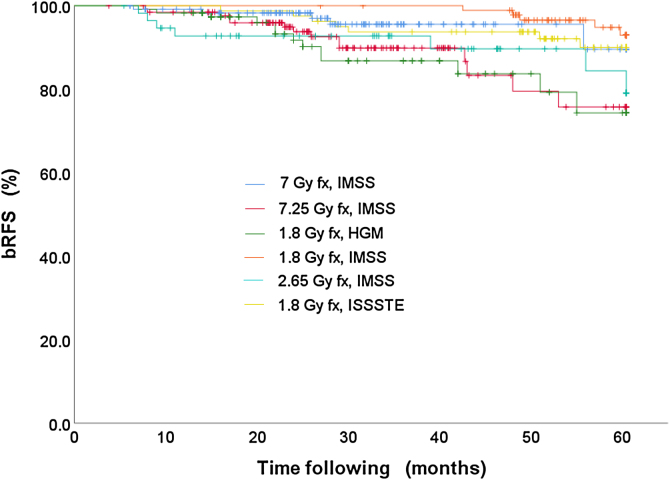

Subsequently, the survival curves for the data in Table 2 were constructed using the K-M method, see Fig. 1. The tests to compare such distributions are (a) Log Rank, (b) Breslow and (c) Tarone-Ware. The results of these tests are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

bRFS curves stratified by institution, technique and treatment scheme.

Table 3.

Test to compare the bRFS rates by institution, technique and treatment scheme.

| Test | χ² | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log Rank | 17.08 | 5 | 0.004 |

| Breslow | 16.74 | 5 | 0.005 |

| Tarone-Ware | 17.40 | 5 | 0.004 |

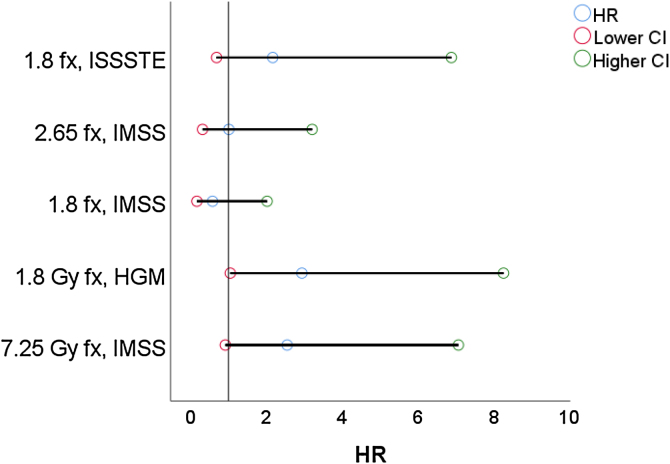

As said before, the Cox proportional hazards are used to perform an analysis that considers the cofactors, see Table 4 and Fig. 2, where the 7 Gy fx scheme i considers the reference treatment.

Table 4.

HR values stratified by scheme and treatment technique.

| Technique | Dose fx (Gy) | Hospital | B | SE | Wald | df | p-Value | HR | CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||||||||

| SBRT | 7 | IMSS | 15.153 | 5 | 0.01 | 95% | ||||

| SBRT | 7.25 | IMSS | 0.935 | 0.521 | 3.219 | 1 | 0.073 | 2.55 | 0.917 | 7.073 |

| IMRT | 1.8 | HGM | 1.079 | 0.527 | 4.2 | 1 | 0.04 | 2.94 | 1.048 | 8.264 |

| 3D-CRT | 1.8 | IMSS | −0.55 | 0.64 | 0.739 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.165 | 2.021 |

| 3D-CRT | 2.65 | IMSS | 0.006 | 0.592 | 0 | 1 | 0.992 | 1.01 | 0.315 | 3.21 |

| 3D-CRT | 1.8 | ISSSTE | 0.777 | 0.588 | 1.743 | 1 | 0.187 | 2.17 | 0.686 | 6.887 |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot considering the SBRT 7 Gy fx scheme as reference.

Finally, the concordance statistic determined for this model is = 0.666 ± 0.034 and R2 = 0.028.

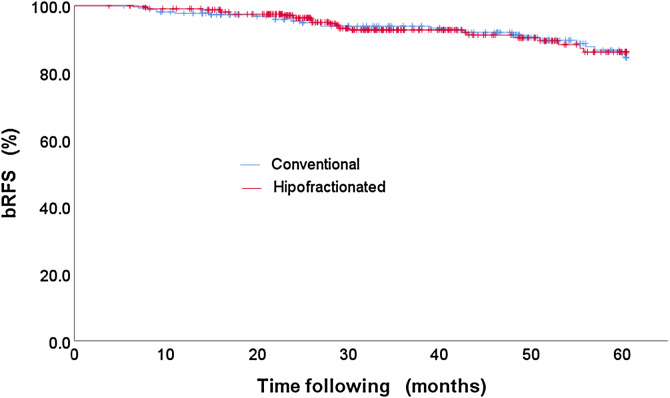

(b) bRFS rate of hypofractioned vs. conventional treatment scheme.

The bRFS rates of the patients who were treated with the hypofractioned vs. conventional scheme are compared. The outcomes of bRFS rate values are: (i) 92.1% for patients who were treated with hypofractionated schemes and (ii) 90.6% for patients who received treatments with conventional schemes.

Apparently, the survival curves stratified by treatment scheme are very similar, see Fig. 3, and, therefore, the statistical test is run to demonstrate the null hypothesis for the equality of the treatment schemes, see Table 5.

Fig. 3.

bRFS rates of hypofraction vs. conventional treatment scheme.

Table 5.

Test to compare the bRFS rates by treatment scheme: hypofraction vs. conventional.

| Test | χ² | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log Rank | 0.031 | 1 | 0.860 |

| Breslow | 0.036 | 1 | 0.849 |

| Tarone-Ware | 0.025 | 1 | 0.873 |

These results point to something very important, since they indicate that there is no statistical significant difference between hypofractioned and standard treatment schemes.

Similarly, the Cox proportional hazards are calculated for this classification, where the standard scheme is taken as reference, see Table 6. This method also reveals that there is no significant difference related to the patient's treatment scheme.

Table 6.

Cox proportional hazards model of hypofraction vs. conventional treatment scheme.

| Technique | B | SE | Wald | df | p-Value | HR | CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | higher | |||||||

| Hypofractioned | −0.05 | 0.281 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.860 | 0.95 | 0.548 | 1.652 |

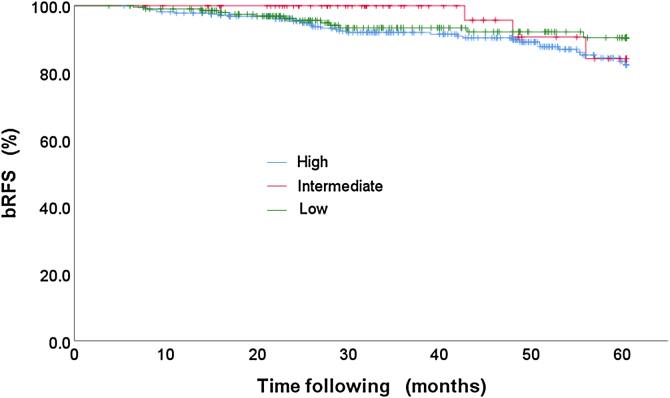

(c) bRFS stratified by risk group.

The percentage of patients classified by risk group is: low risk 11.1% (66 patients), intermediate risk 35.1% (209 patients) and high risk 53.8% (320 patients). And the bRFS rates obtained for this stratification are: 95.5%, 93.8% and 89.1% for the low, intermediate and high risk, respectively, see Table 7. Likewise, the K–M curves were constructed for each of the risks, Fig. 4.

Table 7.

bRFS rates stratified by risk group.

| Risk | Total patients | Patients PSA failure | bRFS Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 66 | 3 | 95.50% |

| Intermediate | 209 | 13 | 93.80% |

| High | 320 | 35 | 89.10% |

Fig. 4.

bRFS stratified by risk group.

To test the H0 hypothesis for the equality of the survival functions for risk group, the Log-Rank, Breslow and Tarone-Ware tests were carried out, and the values resulting from these tests are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Test to compare the bRFS rates distributions by risk group.

| Test | χ² | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log Rank | 2.855 | 2 | 0.240 |

| Breslow | 3.381 | 2 | 0.184 |

| Tarone-Ware | 3.118 | 2 | 0.210 |

Also, for this stratification, the Cox proportional hazards analysis was carried out, where the high risk was taken as a reference, see Table 9.

Table 9.

Cox proportional hazards model by risk group.

| Group | B | SE | Wald | df | p-Value | HR | CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||||||

| High | 2.779 | 2 | 0.249 | |||||

| Intermediate | −0.724 | 0.602 | 1.447 | 1 | 0.229 | 0.485 | 0.149 | 1.578 |

| Low | −0.429 | 0.325 | 1.74 | 1 | 0.187 | 0.651 | 0.344 | 1.232 |

4. Discussion

The bRFS rates obtained are 95.9%, 94.6%, 91.3%, 89.1%, 88.7% and 87.7% for the treatment schemes SBRT (7 Gy fx, IMSS), 3D-CRT (1.8 Gy fx, IMSS), 3D -CRT (2.65 Gy fx, IMSS), SBRT (7.25 Gy fx, IMSS) IMRT (1.8 Gy fx, HGM) and 3D-CRT (1.8 Gy fx, ISSSTE). These results are consistently reported in the literature.21

For the contrast tests stratified by scheme and treatment technique, there is a statistically significant difference in HR only for patients treated with the IMRT technique, see Table 2 and Fig. 2. Where the proportional hazards model was validated with the Concordance test.

On the other hand, the bRFS rates of the hypofractioned vs. conventional scheme are not statistically significant, that is, patients treated with hypofractionated schemes have the same results as patients who were treated with standard treatment schedules, Table 5, 6 and Fig. 3. This is a very important result, since it is verified that for the Mexican population the treatments administered with hypofractionated schemes provide an advantage, as they improve the use of technical, human resources and allow the patients to receive their treatment in a shorter period, with the same probability of tumor control.

In spite of the above, the consequences of this study generate a high impact, since one of the main disadvantages of the treatment of PCa with standard schemes of radiotherapy is the duration of the treatment. For this reason, the possibility of reducing the treatment time, delivering higher doses per fraction, has benefits from an economic and administrative point of view; improves the use of technical and human resources, allows the patient to finish his treatment in a shorter period, causing savings to the institution and the patient, to name a few.

Regarding the bRFS classified by the type of risk, we have values of 95.5%, 93.8% and 89.1% for the low, intermediate and high risk, respectively, as intuitively expected, but when performing the contrast tests and multivariate analysis using the Cox proportions model, we found that there is no statistically significant difference for the risk group, Table 7, Table 8. However, the low risk has a HR = 0.48 while the intermediate risk has HR = 0.64, which together with the negative sign of B indicates a lower risk of biochemical failure with respect to the high risk that has a value of HR = 1.

It is worth mentioning that the proportional hazards model was validated with the Concordance test.

Another fundamental aspect of radiotherapy is to validate the radiobiological sensitivities of α/β for the PCa tumor and risk organs (bladder rectum, penile bulb and so on). A preliminary calculation of α/β considering the treatment schemes for the Mexican population uses the Refs. 13,22 under the hypothesis that the hypofractionated and normal techniques all have the same rate of bRFS (see Fig. 3 and Table 5), which gives us a value of α/β ∼2.8 Gy. This value will be the issue for future research to verify and determine a more accurate value with the corresponding uncertainty or confidence interval.

5. Conclusions

The RT techniques (3D-CRT and SBRT) for the treatment of PCa are statistically equivalent with respect to the rate bRFS. This paper confirms that the bRFS rates of Mexican PCa patients who were treated with conventional vs. hypofractionated schemes show no significant difference.

Another fundamental aspect of radiotherapy is to validate the radiobiological sensitivities of α/β, both for the PCa tumor and risk organs (bladder rectum, penile bulb, to name a few). A preliminary calculation of α/β considering the treatment schemes of this work, gives the value of ∼2.8 Gy. This value will be the reason for future research to determine a more accurate value and with the corresponding uncertainty for the Mexican population.

Finally, the objective of knowing the survival rates of PCa in the Mexican population is to determine the current levels of the bRFS rate to take the corresponding actions in the optimization of the treatment schemes based on the radiobiological optimization.

Financial disclosure

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article have or will confer a benefit on us or on any organization with which they are.

Conflict of interest

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers ‘bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). He is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the corresponding Author and which has been configured to accept email from christhian.adame@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

We thank the Education Department of the all Medical Centers for the facilities given in obtaining data of the treated patients, where, all data is protected by confidentiality regulations. Dr. Alvarez wishes to thank the SSDL/ININ for allowing time for the development of this work; we are also very grateful that the ESFM/IPN to let Dr. Moranchel carry out this research.

References

- 1.http://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer, [Accessed 31/07/2019].

- 2.https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/160-mil-nuevos-casos-de-cancer-al-ano-en-mexico, [Accessed 31/07/2019].

- 3.http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/registros/vitales/mortalidad/tabulados/ConsultaMortalidad.asp, [Accessed 31/07/2019].

- 4.https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/514-cancer-de-prostata-padecimiento-mortal-y-silencioso, [Accessed 31/07/2019].

- 5.Gunderson Leonard, Tepper Joel E. 4th ed. 2012. Clinical Radiation Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catton Charles N., Lukka Himu, Catton Jarad Martin. Prostate Cancer radiotherapy: An evolving paradigm. J Clin Oncol. 2018;29(36):2943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubio-Brionesa J., Ramírez-Backhausa M., Gómez-Ferrera A. Resultados Oncológicos a largo plazo del Tratamiento Cáncer de Próstata de Alto Riesgo mediante Prostatectomía radical en un Hospital Oncológico. Actas Urológicas Españolas. 2018;42(8):507–5151. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nouhi Mojtaba, Mousavi SeyedMasood, Olyaeemanesh Alireza. Long-term outcomes of radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in localized prostate Cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oran J Public Health. 2019;48(4):566–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zietman Anthony L., Kyounghwa Bae, Slater Jerry D. Randomized trial comparing conventional-dose with high-dose conformal radiation therapy in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Long term results from proton radiation oncology group/American college of radiology 95-09. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1106–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.8475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mamgani Abrahim, Putten Wim L.J. Van, Heemsbergen Wilma D. Update of Ducth multicenter dose-escalation trial of radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(4):980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dearnaley D.P., Jovic G., Syndikus I. Escalated-dose versus control-dose conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: long-term results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:464–473. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayles Philip, Nahum Alan, Rosenwald Jean-Claude. Theory and Practice. CRC Press; 2007. Handbook of radiotherapy physics. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler Jack, Chappell Rick, Ritter Mark. Is α/β for prostate tumors really low? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan S.C., Hoffman K., Loblaw D.A. Hypofractionated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: executive summary of an ASTRO; ASCO and AUA evidence-based guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2018;8:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2018.08.002. Epub 2018 Oct 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King Christopher R., Freeman Debra, Kaplan Irving. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: pooled analysis from a multi-institutional consortium of prospective phase II. Protein Sci. 2010;19:2261–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leborgne Felix, Jack Fowler, Leborgne Jose H., Mezzera Julieta. Later outcomes and alpha/beta estimate from hypofractionated conformal three-dimensional radiotherapy versus standard fractionation for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1200–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.https://oncologypro.esmo.org/content/download/196880/3546194/version/1/file/2019-ESMO-Summit-Latin-America-Practice-Management-Prostate-Cancer-Latin-America-Maria-Teresa-Bourlon.pdf, [Accessed 31/07/2019].

- 18.Roach Mack, Hanks Gerald, Thames Howard. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate Cancer: Recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix consensus conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rich J.T., Neely J.G., Paniello R.C., Voelker C.C., Nussenbaum B., Wang E.W. A practical guide to understanding Kaplan Meier curves. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(3):331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez Marcela Pérez, Ruiz Rodolfo Rivas, Cruz LinoPalacios, Talavera Juan O. Del juicio clínico al modelo de riesgos proporcionales. Med Int Mex Seguro Soc. 2014;52(4):430–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson William C., Silva Jessica, Hartman Holly E. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 6,000 patients treated on prospective studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leborgne Felix, Fowler Jack, Leborgne Jose H., Mezzera Julieta. Later outcomes and alpha/beta estimate from hypofractionated conformal three-dimensional radiotherapy versus standard fractionation for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(3):1200–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]