Korean males are required to perform military service, and 92.0% of all enlisted Korean soldiers in 2018 were younger than 22 years. An impacted third molar, which occurs in about 70% of the total population1, is recommended for extraction before age 24 years to limit complications2. Therefore, most Korean soldiers are at the indicated age of surgical extraction. A third molar problem is the second most common dental emergency and results in a significant loss of duty time3. Soldiers, who could be stationed in areas with poor medical accessibility, are recommended to undergo preventive extraction even in the absence of symptoms. As a result, third molar patients represent the largest proportion of patients in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in a military hospital.

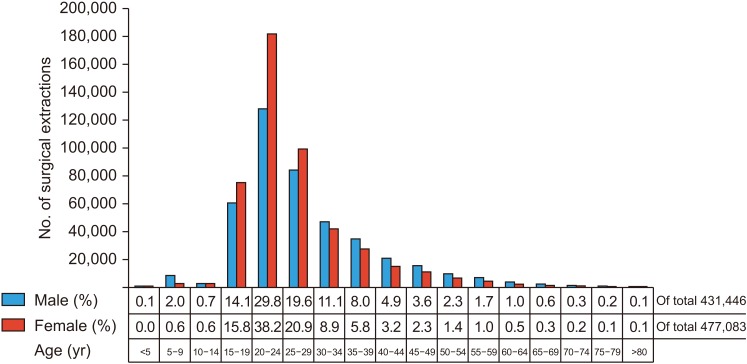

The statistics of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), released in 2018, showed that 54.6% of total extractions in Korea were performed in 20- to 29-year-old people. In particular, the number of extractions in those aged 20 to 24 years was 54,001 fewer in males than females. (Fig. 1) As patients in military hospitals are not included in the statistics of HIRA, the number of extractions in military hospitals should be estimated. From 2013 to 2017, extraction surgeries in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of Armed Forces Capital Hospital accounted for 49.2% of total surgical patients and 8,013 outpatients.

Fig. 1. Numbers of surgical extractions registered in the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service in Korea during 2018.

Most military patients are aged in the early twenties and have similar life patterns due to the nature of military service. In addition, conditions related to extraction surgery could be well controlled because all procedures—anesthesia, incision, ostectomy, odontomy, extraction, suture, dressing, hospitalization, stitch removal, and follow-up observation—are performed by the same military oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Since military hospitals are free of charge for all active duty patients, the surgeon can provide the best treatment options, such as bone graft for bony defect after extraction, without considering cost. Military patients are discharged when they achieve normal dietary intake and high physical activity. Therefore, the hospitalization period is relatively long compared with that in private hospitals. This long hospitalization allows military hospitals to monitor the longer-term condition of extraction patients, including food intake, pain, swelling, anxiety, and satisfactory healing process—which is difficult to achieve in private hospitals.

Although extraction surgery is a common operation in oral and maxillofacial surgery, military hospitals operate on an especially high proportion of third molar patients. Considering the nature of military hospitals, extraction patients could be provided ideal options and close monitoring that is not likely in private hospitals due to practical problems. Military research should be strictly reviewed and approved by the Armed Force Medical Command Institutional Review Board since soldiers are regarded as an ethically vulnerable class, as military hospitals are suitable for third molar research. In conclusion, an expectant leading role in third molar research in Korean military hospitals will contribute to advancement of oral and maxillofacial surgery and to confidence around military medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

How to cite this article: Ku JK. An expectant role of Korean military hospital on impacted third molar research. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;46:1-2. https://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2020.46.1.1

References

- 1.Dodson TB, Susarla SM. Impacted wisdom teeth. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;2014:1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondeau F, Daniel NG. Extraction of impacted mandibular third molars: postoperative complications and their risk factors. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaffin J, Moss D. Review of current U.S. Army dental emergency rates. Mil Med. 2008;173(1 Suppl):23–26. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.supplement_1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]