Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the volumetric stability and bone formation in grafts with Bio-Oss and autogenous bone at different proportions in rabbit calvaria. Material and Methods. Ten rabbits received four titanium cylinders in their calvaria and randomly divided into the following groups: Group I: Bio-Oss (100%), Group II: Bio-Oss (75%) + autogenous bone (25%), Group III: Bio-Oss (50%) + autogenous bone (50%), and Group IV: autogenous bone (100%). After twelve weeks, the animals were euthanized, and samples were collected for clinical and histological analysis.

Results

Clinical analysis showed that Groups I (90.43 ± 8.99) and II (90.87 ± 7.43) had greater dimensional stability compared to Group IV (P=0.0005). Histologically, Groups I, II, and III showed areas of bone formation with particles of biomaterial remaining in close contact with the newly formed bone. However, there were no significant differences between the groups regarding the newly formed bone area.

Conclusion

It was concluded that the use of Bio-Oss either alone or associated with the autogenous bone at a proportion of 25% showed superior dimensional stability compared to the use of autogenous bone in the proposed experimental model.

1. Introduction

Several biomaterials and procedures have been used for bone augmentation in the attempt to increase the long-term success of dental implants [1–3]. An adequate bone volume is one of the critical factors for a successful osseointegration and long-term retention of endosseous dental implants [4–6].

Autogenous bone is considered the gold standard for reconstructive techniques due to its biocompatibility and having osteogenic, osteoconductive, and osteoinductive properties. However, it presents some disadvantages such as the need for additional surgical donor site, associated morbidity, and rapid resorption rate [2–4, 7, 8].

Thus, several biomaterials have been developed in an attempt to reduce the use of or even replace the autogenous bone graft in reconstructive surgeries. Among these, Bio-Oss—a deproteinized bovine bone—has been used in dentistry for bone augmentation procedures due to its osteoconductive properties [9]. Previous studies have demonstrated effectiveness, safety, and high success rates regarding the quality and quantity of bone formation with Bio-Oss in grafting procedures [1, 10, 11]. In addition, adequate results have been already demonstrated in terms of integration without local hosting and low reabsorption [12–14].

The use of autogenous bone in combination with the deproteinized bovine bone is believed to be a better method because of its osteogenic property [10–16]. Despite the extensive literature, preclinical studies comparing volumetric stability and bone formation in bone augmentation procedures using Bio-Oss and autogenous bone grafts are scarce. Moreover, there is no consensus in the literature on the ideal proportion of Bio-Oss and autogenous bone graft. The aim of this study was to compare the volumetric stability and bone formation in grafts with Bio-Oss and autogenous bone at different proportions in rabbit calvaria. The hypothesis of this study was that the proportion of the amount of autogenous bone and Bio-Oss in the graft could influence the volumetric stability and the grater new bone formation.

2. Materials and Methods

This present study has been approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of University of Santo Amaro (CEUA 11/2011).

A total of ten New Zealand rabbits weighing between 3.0 and 4.0 kg, aged between 11 and 15 months, were kept in individual cages under controlled temperature (22–25°C) and received a standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum.

2.1. Surgical Procedure

For all surgical procedures, the animals were initially anesthetized with ketamine 10% (40 mg/kg body wt.) (Ketamin S., Crisfarma, Sergipe, Brazil) and xylazine 2% (8 mg/kg body wt.) (Virbaxyl 2%, Virbac, São Paulo, Brazil), both intramuscularly, before local infiltration of 2% lidocaine with norepinephrine (Alphacaine, DFL, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). In addition, the animals were maintained on intravenous hydration with saline solution 0.9% during surgery.

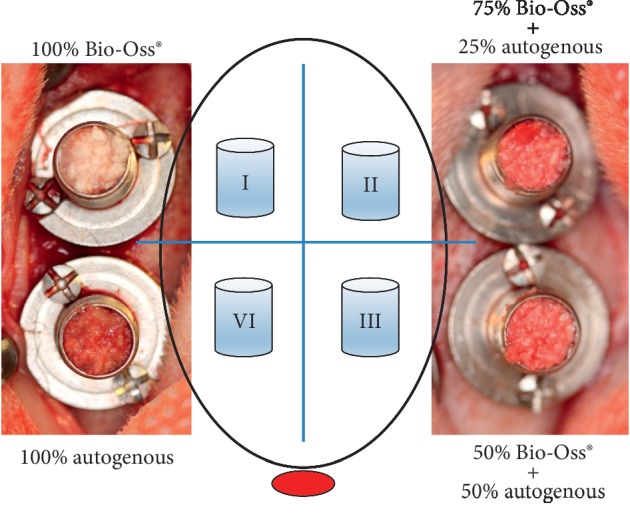

Incision was made in the skin of the calvaria region, and the tissues were dissected to expose the calvarial bone. Each animal received four titanium cylinders of 5 mm in diameter × 5 mm in height (Conexão®, São Paulo, Brazil) attached with two screws of 1.5 mm in height × 1.5 mm in diameter (Neodent®, Curitiba, Brazil). Decortication of the internal region of the cylinder was made with a 1.1 mm diameter drill under constant irrigation with saline solution 0.9%. The cylinders were randomly divided into four groups according to the grafts (Figure 1) as follows:

Group I: anorganic bovine bone graft (100% Bio-Oss)

Group II: anorganic bovine bone graft (75% Bio-Oss) + 25% autogenous bone

Group III: anorganic bovine bone graft (50% Bio-Oss) + 50% autogenous bone

Group IV: 100% autogenous bone

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the cylinders distributed into four groups according to the grafts placed in the rabbit caldarium.

The autogenous bone graft was obtained from the iliac crest. The lateral surface of the posterior iliac crest was exposed by a skin incision, and the tissues were dissected to show the iliac crest bone. Next, a cortical-cancellous bone graft was harvested and then separated. Autogenous bone graft and anorganic bovine bone graft (particle size of 1-2 mm; Bio-Oss, Geistlich Pharmaceutical, Wolfhausen, Switzerland) were proportionally mixed according to the experimental groups.

The cylinders were filled with the biomaterial according to the experimental groups (Figure 1) and covered before the wounds were sutured with 4-0 nylon threads (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, São José dos Campos, Brazil).

Postoperatively, the animals were medicated with antibiotics enrofloxacin 2.5% (0.4 ml/kg body wt.), enrofloxacin 10% (Vencofarma, Londrina, Brazil), and Flotril® (Schering Plough, São Paulo, Brazil) by subcutaneous injections for seven days as well as with analgesic meloxicam intramuscularly for seven days (0.01 ml/kg body wt.) (Maxicam®, OuroFino, São Paulo. Brazil).

2.2. Calculation of Bone Graft Volume

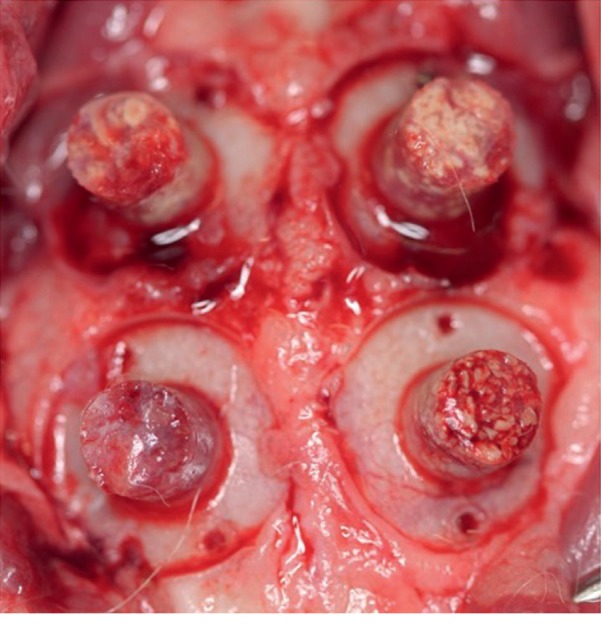

After 12 weeks, all animals were euthanized with an overdose of anaesthetics. The calvaria were surgically reopened, and the screw caps of the cylinder were removed (Figure 2). Next, the height of the bone graft was measured by one blinded calibrated examiner, who used a PDT Sensor Probe™ (Type U.S, Zila Pharmaceuticals, Phoenix, USA) in four sites of each sample.

Figure 2.

Clinical image of the bone grafts in the rabbit calvarium 12 weeks after the surgery.

The volume of the bone graft was calculated according to the following formula:

| (1) |

where V is the volume, π is a mathematical constant = 3.1415, r is the cylinder radius = 2.5 mm, and h is the mean height of the formed tissue graft.

2.3. Tissue Processing and Histomorphometric Analysis

The calvarial bone of each animal was carefully removed and then sectioned together with the four cylinders. The samples were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 hours prior to routine histological processing and paraffin embedding. Histological serial sections with 5 μm thickness were cut in the sagittal plane (Jung Supercut 2065 Leica, Chicago, IL, USA), and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) was used for staining them. Histological slides were analysed by using a light microscope (LEICA Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), and images were captured with a digital camera (Leica DFC 300 FX, Wetzlar, Germany) at a 40x magnification. The digital images were exported for histomorphometric analysis, which was performed by a calibrated blinded examiner using specific software (ImageJ, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) in a standardized manner.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed by using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). In relation to volume data, Shapiro–Wilk's test was used to assess data normality, and Friedman's test was used for comparison between the groups.

After testing the normal distribution of the histomorphometric data with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, statistical significance was assessed by using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons between the groups at a statistical significance of P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Volume Maintenance of the Bone Graft

All groups had samples integrated to the calvarium of the animals, without signs of infections.

In relation to volume, Groups I and II showed resorption less than 10% of the total volume, whereas Group IV showed resorption greater than 30%. Thus, there was a greater volume maintenance in Groups I and II compared to Group IV (P=0.0005) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Volume maintenance of the bone graft.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone graft volume (%) | 92.68 ± 6.05 | 90.87 ± 7.43 | 82.28 ± 8.57 | 67.02 ± 17.89∗ |

Mean ± SD (%); ∗p=0.0005; Group I = Group II > Group IV.

3.2. Histomorphometric Analysis

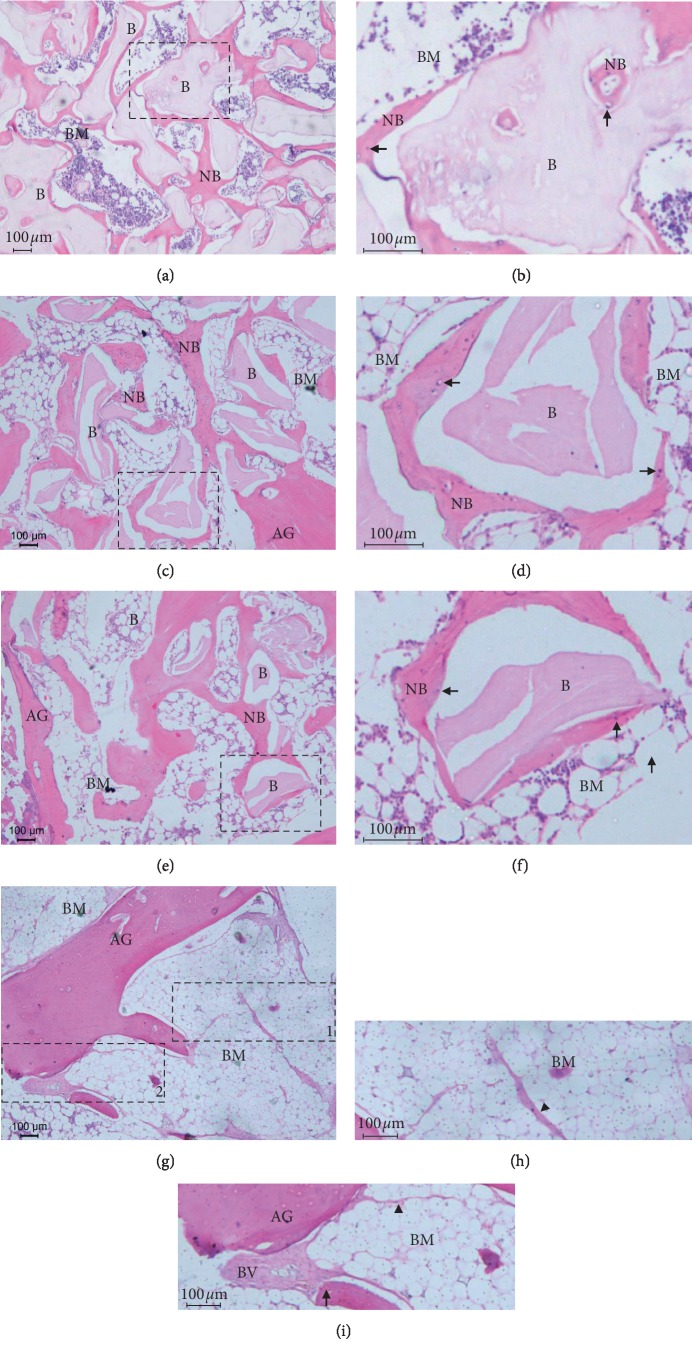

There was no inflammatory process in all histological sections evaluated. The grafted material was integrated into the pre-existing bone, demonstrating a good bone-healing pattern with normal mineralization of the neo-formed bone. In addition, Groups I, II, and III showed regions of bone neo-formation interspersed with residual biomaterial in which the remaining biomaterial particles were in contact with bone apposition on their surface. The bone marrow space varied in volume along the bone, presenting either greater or lesser amounts (Figure 3). However, there were no significant differences regarding the bone area between the groups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs showing bone formation in different groups: (a, b) Group I (100% Bio-Oss), (c, d) Group II (75% Bio-Oss + 25% autogenous bone), (e, f) Group III (50% Bio-Oss + 50% autogenous bone), and (g, h, i) Group IV (100% autogenous bone). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of all groups. Bars: 100 μm. Residual particles of biomaterial (B), newly formed bone (NB), bone marrow (BM), autogenous bone graft (AG), osteocyte (arrow), and blood vessels (BV). Extracellular matrix of bone marrow seems to be replaced by adipose tissue (arrowhead). Dotted squares in (a), (c), and (e) represent the areas observed at higher magnification in (b), (d), and (f), respectively. Dotted rectangles (1) and (2) in (g) represent the areas observed at higher magnification in (h) and (i), respectively.

Table 2.

Histomorphometric analysis of the areas of the newly formed bone.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newly formed bone (mm2) | 2.44 ± 0.80 | 2.24 ± 0.85 | 2.63 ± 0.72 | 3.33 ± 0.66 | 0.25 |

| Residual particles (mm2) | 2.70 ± 0.79 | 2.37 ± 0.60 | 2.03 ± 0.41 | 0.00∗ | <0.0001 |

Mean ± SD.

4. Discussion

This study was carried out in rabbits based on a methodology already applied by our research team in which titanium cylinders were attached to the calvaria of rabbits with two screws to create and stabilize an area to be filled with the biomaterial [17, 18]. This simulates a clinical situation in which there is no wall with vascularization pathway, which is similar to that found in maxillary sinus lift surgery or in which there is a critical bone defect with only one remaining bone wall, permitting the comparison of four different ratios of Bio-Oss and autogenous bone in the same animal.

Among the biomaterials, Bio-Oss has been widely used in bone augmentation procedures due to its high success rate and predictability. Earlier studies have tested different ratios of the autogenous bone associated with Bio-Oss in bone augmentation procedures, ranging from the addition of an undefined proportion of the autogenous bone [10, 19, 20] to ratios of 2 : 1 [21], 1.5 : 1 [22], 1 : 1 [12, 15, 16, 23], 1 : 2 [15], and 1 : 4 [15, 24–26]. The purpose of this approach is to add viable osteoblasts to improve bone induction and bone formation. However, there is still no consensus regarding the ideal proportion of autogenous bone and Bio-Oss to optimize bone formation [13].

In our study, the data demonstrated that the autogenous bone alone undergoes faster resorption and remodeling compared to any other mixture, showing that the volume reduction in Group IV was statistically significant compared to Groups I, II, and III (Table 1). Some studies using only autogenous graft for bone augmenting procedures showed unpredictable reduction in volume [4, 27, 28].

The volume stability of the graft is an important factor for implant survival, and the proportion of Bio-Oss has a significant influence on the graft. These findings are consistent with other studies using only Bio-Oss as a graft material as they reported higher dimensional maintenance compared to the autogenous bone in the short and long terms [26, 29, 30]. Also, Bio-Oss demonstrated high volume maintenance and new bone formation [12, 13, 30].

In the present study, the histomorphometric analysis revealed similar rate of the newly formed bone between the groups (Table 2). These results indicate that quantity and quality of the newly formed bone were the same in the groups not influenced by the percentage of autogenous bone. Also, the newly formed bone in close contact with the residual particles in the groups using Bio-Oss suggests that this biomaterial induces bone formation without any influence on the bone graft resorption due to its stability and osteoconductive property.

The volume stability was significantly influenced by the proportion of Bio-Oss in the bone graft. The addition of Bio-Oss in any proportion would be beneficial for the maintenance of the grafted region, resulting in long-term implant survival.

5. Conclusions

One can conclude that the use of Bio-Oss alone or associated with the autogenous bone in the proportion of 25% showed superior dimensional stability compared to the use of autogenous bone alone in the proposed experimental model.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) according to protocol number 143741/2014–0.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kao S. T., Scott D. D. A review of bone substitutes. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 2007;19(4):513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmagnola D., Abati S., Celestino S., Chiapasco M., Bosshardt D., Lang N. P. Oral implants placed in bone defects treated with Bio-Oss, ostim-paste or perioglas: an experimental study in the rabbit tibiae. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2008;19(12):1246–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chavda S., Levin L. Human studies of vertical and horizontal alveolar ridge augmentation comparing different types of bone graft materials: a systematic review. Journal of Oral Implantology. 2018;44(1):74–84. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-d-17-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browaeys H., Bouvry P., De Bruyn H. A literature review on biomaterials in sinus augmentation procedures. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 2007;9(3):166–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2007.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlegel A., Hamel J., Wichmann M., Eitner S. Comparative clinical results after implant placement in the posterior maxilla with and without sinus augmentation. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2008;23(2):289–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulinelli J. L., Dutra R. A., Marão H. F., Simeão S. F. P., Groli Klein G. B., Santos P. L. Maxilla reconstruction with autogenous bone block grafts: computed tomography evaluation and implant survival in a 5-year retrospective study. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2017;46(8):1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maiorana C., Poli P. P., Mascellaro A., Ferrario S., Beretta M. Dental implants placed in resorbed alveolar ridges reconstructed with iliac crest autogenous onlay grafts: a 26-year median follow-up retrospective study. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2019;47(5):805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papageorgiou S. N., Papageorgiou P. N., Deschner J., Götz W. Comparative effectiveness of natural and synthetic bone grafts in oral and maxillofacial surgery prior to insertion of dental implants: systematic review and network meta-analysis of parallel and cluster randomized controlled trials. Journal of Dentistry. 2016;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artzi Z., Nemcovsky C. E., Tal H. Efficacy of porous bovine bone mineral in various types of osseous deficiencies: clinical observations and literature review. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2001;21(21):395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yildirim M., Spiekermann H., Handt S., Edelhoff D. Maxillary sinus augmentation with the xenograft bio-oss and autogenous intraoral bone for qualitative improvement of the implant site: a histologic and histomorphometric clinical study in humans. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2001;16(1):23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijndert L., Raghoebar G. M., Schüpbach P., Meijer H. J. A., Vissink A. Bone quality at the implant site after reconstruction of a local defect of the maxillary anterior ridge with chin bone or deproteinised cancellous bovine bone. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2005;34(8):877–884. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galindo-Moreno P., Moreno-Riestra I., Avila G., et al. Effect of anorganic bovine bone to autogenous cortical bone ratio upon bone remodeling patterns following maxillary sinus augmentation. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2011;22(8):857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen T., Schou S., Stavropoulos A., Terheyden H., Holmstrup P. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation with bio-oss or bio-oss mixed with autogenous bone as graft: a systematic review. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2012;23(3):263–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aludden H. C., Mordenfeld A., Hallman M., Dahlin C., Jensen T. Lateral ridge augmentation with bio-oss alone or bio-oss mixed with particulate autogenous bone graft: a systematic review. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2017;46(8):1030–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pripatnanont P., Nuntanaranont T., Vongvatcharanon S. Proportion of deproteinized bovine bone and autogenous bone affects bone formation in the treatment of calvarial defects in rabbits. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;38(4):356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thuaksuban N., Nuntanaranont T., Pripatnanont P. A comparison of autogenous bone graft combined with deproteinized bovine bone and autogenous bone graft alone for treatment of alveolar cleft. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010;39(12):1175–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polo C. I., Lima J. L. O., De Lucca L., et al. Effect of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 associated with a variety of bone substitutes on vertical guided bone regeneration in rabbit calvarium. Journal of Periodontology. 2013;84(3):360–370. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelegrine A. A., Costa C. E. S. d., Sendyk W. R., Gromatzky A. The comparative analysis of homologous fresh frozen bone and autogenous bone graft, associated or not with autogenous bone marrow, in rabbit calvaria: a clinical and histomorphometric study. Cell and Tissue Banking. 2011;12(3):171–184. doi: 10.1007/s10561-010-9178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y.-K., Yun P.-Y., Kim S.-G., Lim S.-C. Analysis of the healing process in sinus bone grafting using various grafting materials. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2009;107(2):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassan K. S., Marei H. F., Alagl A. S. Composite bone graft for treatment of osseous defects after surgical removal of impacted third and second molars: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2011;112(6):e8–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatano N., Shimizu Y., Ooya K. A clinical long-term radiographic evaluation of graft height changes after maxillary sinus floor augmentation with a 2:1 autogenous bone/xenograft mixture and simultaneous placement of dental implants. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2004;15(3):339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mooren R. E. C. M., Dankers A. C. A., Merkx M. A. W., Bronkhorst E. M., Jansen J. A., Stoelinga P. J. W. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on early and late bone healing using a mixture of particulate autogenous cancellous bone and Bio-Oss: an experimental study in goats. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010;39(4):371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young C., Sandstedt P., Skoglund A. A comparative study of anorganic xenogenic bone and autogenous bone implants for bone regeneration in rabbits. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 1999;14(1):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallman M., Sennerby L., Lundgren S. A clinical and histologic evaluation of implant integration in the posterior maxilla after sinus floor augmentation with autogenous bone, bovine hydroxyapatite, or a 20:80 mixture. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2002;17:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallman M., Sennerby L., Zetterqvist L., Lundgren S. A 3-year prospective follow-up study of implant-supported fixed prostheses in patients subjected to maxillary sinus floor augmentation with a 80:20 mixture of deproteinized bovine bone and autogenous bone. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2005;34(3):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mardinger O., Chaushu G., Sigalov S., Herzberg R., Shlomi B., Schwartz-Arad D. Factors affecting changes in sinus graft height between and above the placed implants. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2011;111(1):e6–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansson B., Grepe A., Wannfors K., Hirsch J.-M. A clinical study of changes in the volume of bone grafts in the atrophic maxilla. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. 2001;30(3):157–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakkas A., Wilde F., Heufelder M., Winter K., Schramm A. Autogenous bone grafts in oral implantology-is it still a “gold standard”? A consecutive review of 279 patients with 456 clinical procedures. International Journal of Implant Dentistry. 2017;3(1):p. 23. doi: 10.1186/s40729-017-0084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert F., Léonard A., Drion P., Sourice S., Layrolle P., Rompen E. Influence of space-filling materials in subantral bone augmentation: blood clot vs. autogenous bone chips vs. bovine hydroxyapatite. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2011;22(5):538–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Araújo M., Linder E., Lindhe J. Effect of a xenograft on early bone formation in extraction sockets: an experimental study in dog. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2009;20(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.