Abstract

Missed care, defined as any aspect of patient care that is omitted or delayed, is receiving increasing attention. It is primarily caused by the imbalance between patients’ nursing care needs and the resources available, making it an ethical issue that challenges nurses’ professional and moral values. In this scoping review, conducted using the five-stage approach by Arksey and O’Malley, our aim is to analyze the patients’ perspective to missed care, as the topic has been mainly examined from nurses’ perspective. The search was conducted in April 2019 in PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ProQuest and Philosophers Index databases using the following terms: omitted care, unfinished nursing care, care undone, care unfinished, missed care, care left undone, task undone and implicit rationing with no time limitation. The English-language studies where missed care was examined in the nursing context and had patients as informants on patient-reported missed care or patients’ perceptions on nurse-reported missed care were selected for the review. Thirteen studies were included and analyzed with thematic content analysis. Twelve studies were quantitative in nature. Patients were able to report missed care, and mostly reported missed basic care, followed by missed communication with staff and problems with timeliness when they had to wait to get the help they needed. In statistical analysis, missed care was associated with patient-reported adverse events and patients’ perceptions of staffing adequacy, and in patients’ perception, it was mainly caused by lack of staff and insufficient experience. Furthermore, patients’ health status, as opposed to gender, predicted missed care. The results concerning patients’ age and education level were conflicting. Patients are able to identify missed care. However, further research is needed to examine patient-perceived missed care as well as to examine how patients identify missed care, and to get a clear definition of missed care.

Keywords: omitted care, care left undone, unmet nursing care needs, patient perceptions

Introduction

Literature related to missed care has increased over the last decade,1 providing evidence of its prevalence and the threat it poses.2,3 The primary cause of missed care seem to be limited nursing resources.4 Missed care is an international problem as most nurses report at least one task left undone in a shift, based on an international review.3 However, little is known about patients’ views on this timely topic. Patients’ perspective in this review is viewed as patients’ personal perception about missed care as well as patients’ perception of their care environment where care is missed based on nurses’ reports. Missed care has been associated with decreased nurse-reported care quality, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction, as well as increased adverse events, turnover and intent to leave.3 Furthermore, an association has been found between missed care and nursing work environment and patient safety culture.5 Predictors of missed care include nurse’s shift type, resource allocation, health professional communication and workload intensity, and predictability.6 Therefore, the worldwide prediction of a nurse shortage underlines the importance to understand the phenomenon.7

The terminology referring to missed care varies in literature, as some studies view missed care as an implicit rationing of nursing care, referring to nurses’ bedside decision-making, leading to failure to carry out all needed nursing interventions because of inadequate resources.8 In addition, the terms care left undone,9,10 nursing task left undone,11 task incompletion12, and unmet nursing care needs13 have been used. The first report on this topic was from the International Hospital Outcomes Research (IHORC), using the term nursing care left undone.9 The term missed care was first used in 2006 by Kalisch in her identification of nine elements of regularly missed nursing care and the reasons for them.14

Missed care occurs when any aspect of required patient care is omitted (in part or whole) or delayed,15 including all aspects of clinical, emotional and administrative nursing care.3 There are some conceptualization of missed care16 including the Missed Nursing Care Model, which is a middle-range theory developed by Kalisch (2009).15 This model identifies external antecedents for missed care, such as resources and communication and relationships among staff, that have an effect on the nursing process. If nurses lack resources, they must prioritize how to best use the resources available. This decision-making interacts with the internal processes of nurses (including staff norms, the prioritization of the care, personal values and behavior). All these factors contribute to missed care, which has adverse outcomes for patients. The model identifies organizational characteristics as factors that facilitate or constrain nurses’ practice.15 Another conceptual model, Implicit Rationing developed by Schubert (2007), is mainly used with cost reduction and the allocation of inadequate resources. This model also recognizes nurses as decision-makers, as they must prioritize, and acknowledges both individual and organizational factors contributing to rationing of nursing care. The number of omitted nursing activities measures the extent of the rationing and is an important indicator of the quality of care.8 The conceptual framework of The Task Undone was originally described by Lucero et al (2009) using the Process of Care and Outcome model. In this model, the necessary care activities that are left undone reflect the quality of provided nursing care as they have negative outcomes for patients.17

Missed care is associated with patient safety culture,5 which has been examined in different theoretical frameworks. Groves et al18 recommend structuration theory of safety culture, which is a middle-range theory that is widely used to examine different organizational topics. It views safety culture as a system that involves individual actions as well as organizational structures. Nurses share values regarding patient safety and enact them in their practice. Organizational structures, such as resources and rules, both enable and constrain nurses’ action to keep patients safe.18 This model could also be adapted to examine missed care. However, there is currently a lack of a theoretical framework and common terminology to describe missed care as it remains unclear whether an understanding exists about how it occurs or whether the causation and response to missed care are similar across different health-care environments; development of a theoretical framework to describe and understand missed care is thus highly needed.19

Missed care is an ethical issue challenging nurses’ professional and moral values, consequently leading to imbalance between patients’ needs and available and/or scarce resources. Therefore, nurses need to prioritize their work, and missed care is an outcome of this prioritization process.20 Missed care is an error of omission, meaning failure to do the right thing, which potentially leads to adverse outcomes to patients, impacting the quality of care negatively. Higher missed care has been associated with a greater risk of patient falls, while missed ambulation can cause pressure ulcers, pneumonia, delayed wound healing, and increased pain and suffering.21 Thus, missed care has been associated with lower patient safety.22,23

The research emphasis of this topic has mainly been on nurses’ perspective3,10 Thus, the aim of this scoping review is to analyze the patients’ perspective to missed care as it has not received adequate research interest. Today, patients are recognized as partners in health care and experts on their situation, working alongside professionals, with their own rights as well as responsibilities.24 This view is associated with the empowerment philosophy to health, which aims to increase patient autonomy and freedom of choice, encouraging patients to oversee their own health values, needs and goals.25 Therefore, patients should be involved in the discussion about the requirements of nursing care and the prioritization process where nurses are unable to respond to patients’ needs.20 This paper adds to the existing literature by examining how patients’ perceptions on missed care have been examined, how patients are able to identify missed care, what care has been mostly identified as missing by patients, and how patients experience the received care when nurses report missed care. In this review, the term missed care expresses patients’ perception that something is missing, delayed or not done during their health-care treatment. The goal of the analysis is to deepen our understanding of the concept of missed care and to provide a basis for further studies in the field.

Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted using the five-stage approach by Arksey and O’Malley (2006).26 In the next paragraph, the five stages of analysis are described in more detail.

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

The following research questions were identified to guide the scoping review:

How have patients’ perceptions of missed care been studied?

What instruments were used to measure patients’ perceptions on missed care?

What were the main findings of the studies?

What are the implications and suggestions for further research in the studies?

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

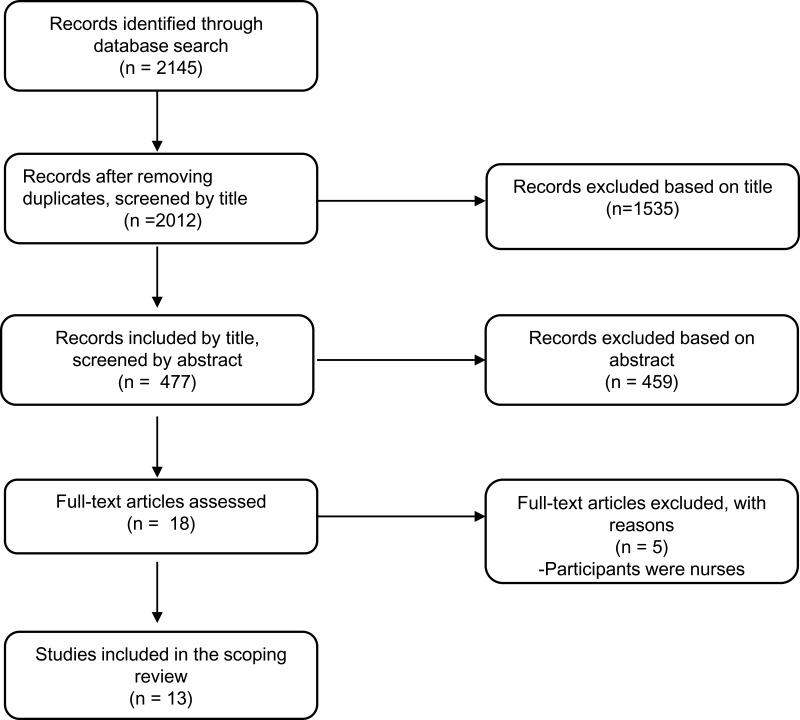

Six electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ProQuest/Scholarly Journals and Philosophers Index) were searched in April 2019 using the terms omitted care, unfinished care, care undone, care unfinished, missed care, care left undone, task undone and implicit rationing. No time limitation was used in the search. The search phrases, chosen in collaboration with the university library information specialist, followed the guidelines of each database. In addition to the systematic database search, a manual search of the reference lists of the included articles as well as scanning through Google Scholar and Academic Search Premier databases was conducted; however, no new articles were identified. In total, the search produced 2145 hits (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart on the article selection process.

Stage 3: Study Selection

Study selection started by determining the inclusion criteria for the articles.26 After the search was conducted, two research approaches in studies of missed nursing care from the patient perspective were identified. The first approach used validated instruments for measurement of missed nursing care from the patient perspective. The second used validated instruments to measure missed nursing care from the nurse’s perspective, linking it to patient data. In these studies, mostly patient satisfaction was measured. These studies have proven that patient satisfaction is linked to missed nursing care from the nurses’ perspective.27 Therefore, it is important to include these studies in this review because they give us important answers of patients’ perspective of their care in an environment where nurses report missed care. Hence, articles were eligible for inclusion if they: 1. Examined missed care in the nursing context; 2. Had patients as participants to provide full or partial data, so that at least some data were collected from patients (patient-reported missed care or patients’ perceptions on nurse-reported missed care); and 3. Were empirical study reports in English. Studies conducted solely from the nurses’ perspective were excluded. Records were first screened by title and afterwards by abstract, leading to exclusion of 1994 articles. Full-text articles (n=18) were finally read among those that were selected based on abstract. Finally, 13 articles were included in the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Articles Included in the Analysis

| Authors, Year, Country and Number in the Reference List | Purpose | Methods/Sample | Instruments | Main Results | Validity/Reliability | Implications to Further Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aiken et al 2018 UK41 | To inform policy decisions. | Cross-sectional survey study. Participants: patients (n=66,348) and nurses (n=2463). | Patients: NHS survey of inpatients. Nurses: The Practice Environment Scale-Nursing Working Index (PES-NVI) and report how many patients they cared for on their last shift and the amount of missed care. | 52.6% of patients rated care as excellent. 75.1% had confidence and trust in nurses and 60.4% said there were enough nurses. 27% of nurses lacked the time to complete three or four of the types of care listed. Significant association was found between nurse-reported missed care and patients rating their care as excellent. (p=<0.001). |

Use of validated measures. Cross-sectional design allows no causal inferences about the associations found between patients’ perceptions of hospital care and nurse-reported missed patient care. Data is from 2010. |

Not reported. |

| Bachnick et al 2018 Switzerland42 | To describe patient-centered care and explore the associations with nurse work environment and implicit rationing of nursing care. | A sub-study of a larger cross-sectional multi-centered study. Participants: patients (n=2073), and nurses (n=1810). |

Patients: The Generic Short Patient Experiences Questionnaire (GS-PEQ), 4 items. Nurses: The Practice Environment Scale-Nursing Working Index (PES-NWI), 2 subscales used: 1. “Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses”, (Cronbach’s alpha 0.79.) 2. “Staffing and resource adequacy” (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83). The Basel Extent of Rationing of Nursing Care (BERNCA) Cronbach’s alpha 0.88. | Patients reported high levels of patient-centered care. Significant association was found between nurse-reported missed care and 3 out of 4 points of patient-centered care reported by patients: easy to understand (p=<0.0,05), enough information (p=<0.01), and treatment and care adapted (p=<0.01) as opposed to nurse-reported missed care and patient-reported involvement in decision-making. | Large sample and high response rate. Design allows no causality conclusions. Results have limited generalizability. Voluntary involvement might cause selection bias. Using all 5 subscales of PES-NWI might have changed the results. Patient surveys had an overall data omission rate of 26%. Some patients had help from staff when answering, which might have influenced the responses. | Further research is needed to identify and develop instruments to distinguish meaningfully between hospitals providing patient-centered care as well as to assess the relative values of various patient-centered care component mixes in specific contexts. |

| Cho et al 2017 South Korea34 | To examine the relationships between nurse staffing and patients’ experiences, and to determine the mediating effects of patient-reported missed care on the relationship between them. | Descriptive cross-sectional study. Participants: nurses (n=362), nurse managers (n=23) and patients (n=210). |

The nurse manager survey measured the patient-to-nurse ratio. The nurse survey included nurse-perceived staffing adequacy: a 4-point scale varying from 1, very insufficient to 4, very sufficient. Patient-perceived staffing adequacy was measured using the same scale. Patients: the MISSCARE Survey–Patient questionnaire: contains 13 items divided into three (communication, basic care, and timely responses) domains with Cronbach alphas 0.78, 0.86, and 0.78. HCAHPS survey measured patients’ experiences of communication with nurses, Cronbach alpha 0.82. Patients were also asked to rate their hospital from 0 (worst) to 10 (best). |

Patients reported missed basic care: mean 3.57 (SD 1.23) missed communication 2.02(SD 0.83) and timely responses 1.29 (SD 0.54). Patients experiencing at least one adverse event had a significantly higher mean score for missed communication and missed basic care than those who did not experience adverse events. A significant inverse relationship was found between nurse-perceived staffing adequacy and patient-reported missed communication (p = 0.29), as opposed to patient-reported missed basic care. Patient perceptions of staffing adequacy were significantly associated with patient-reported missed communication (p < 0.001), patient-reported missed basic care (p = 0.004), adverse events experienced by patients (p = 0.27), communication with nurses (p < 0.001) and overall hospital rating (p < 0.001). Patient-to-nurse ratio was not significantly associated with patient-reported missed care. Findings indicated the mediating effects of missed care on the relationship between nurse staffing and patients’ experiences. |

Methodology allows no causal inferences about the associations found among nurse staffing, missed care, and patients’ experiences. Findings are only generalizable to the South Korean context. Patient and hospital characteristics that may have affected patients’ experiences were not adjusted for. Missed care might not indicate that patients did not receive the care in question due to the possibility that patients’ families were providing it. Effect sizes were not available to conduct a power analysis prior to data collection. | Not reported. |

| Orique et al 2017 USA36 | Describes aspects of missed nursing care, examines patient factors associated with missed care and describes a process for constructing a standardized missed nursing care metric. | A descriptive cross-sectional study. Data was collected using HCAHPS survey. Participants: patients (n=1125). |

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Systems (the HCAHPS) survey. (Elements of missed nursing care listed in the MISSCARE survey were used as framework for data abstraction when coding patient text comments in categories). |

Missed nursing care is significantly higher among patients reporting poorer health (p=<0.001). Patient’s age, gender or education level were not significantly associated with missed care. 38% of patients reported at least 1 missed nursing activity during their hospitalization. Most frequently missed were explanation of medication adverse effects (24.4%), assistance post discharge (21.5%), and instructions post discharge (14%). Free text part: 335 respondents identified at least 1 aspect of care being missed, including call light assistance (16.4%), symptom management (13.7%), teaching (11.9%), and toileting (10.1%). | Data was collected from one hospital, response rate 21%. Patients received surveys well after discharge which may influence their memory of care. The survey is limited to the USA, limiting generalizability. Ideally, the process of validating measurement of missed nursing care using the HCAHPS survey would include multiple confirmatory strategies such as the MISSCARE survey and use of the electronic medical record. |

Further research is needed to develop percentile ranks for benchmarking and comparison between organizations. Also, multiple confirmatory strategies will need to be developed to improve the validity of this method in measuring missed nursing care. |

| Bruyneel et al 2015 Belgium/Netherlands/Switzerland/USA39 | Study integrates previously isolated findings of nursing outcomes research into an explanatory framework in which care left undone and nurse education levels are of key importance | Cross-sectional data from eight countries. Participants: patients (n= 11,549) and nurses (n=10,733). |

Patients’ overall ratings of the hospital and their willingness to recommend the hospital, items derived from HCAHPS survey. Nurses: Practice Environment Scale-Nursing Working Index (PES-NVI). Nursing care left undone was measured based on nurses’ reports of tasks that were left undone on their last shift because of lack of time, from a list of 13 nursing activities. Nurse education levels. Data on hospital characteristics |

Patients report better care experiences in hospitals with better nursing work environments (0.324, indicates statistical significance). On a scale 0–13, nurses reported an average 1.79 (range 0.60–3.32) missed nursing care tasks in their last working shift. More favorable work environments (−1.636*), lower patient-to-nurse ratios (0.039*) and performing less overtime relate significantly (1.332*) to fewer clinical nursing care tasks left undone and fewer planning and communication activities left undone. *indicates statistical significance. |

Methodology allows no causal inferences. Omitted variable bias may have occurred by not including elements of nurse wellbeing, which also links with the main explanatory variables used and patient care experiences. It was not studied if the same effects persist across different shifts. While random effects were included for the hospital and country level, it cannot be concluded that all findings could be exactly replicated in each country. | Future research is needed about the expectations of patients regarding professional hospital care. |

| Dabney B. & Kalisch B. 2015 USA33 | To explore patient reports of missed care and its relationship to unit’s nurse staffing levels. | Cross-sectional study, secondary analysis. Participants: patients (n= 729). |

Patients: MISSCARE survey-patient questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha for overall instrument 0.838 and for the subscales 0.708–0.834. RNHPPD, NHPPD and RN skill mix. |

Patients reported overall missed care average 1.82 (SD 0.62) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (care never missed) to 5 (care always missed). Mostly basic care 2.29 (SD 1.06), followed by missed communication 1.69 (SD 0.71) and timeliness 1.52 (SD 0.64). Age was a predictor of missed timeliness. A negative correlation was found between NHPPD and patient-reported missed timeliness (p=0.15) as opposed to NHPPD and missed basic care or communication (in contrast to previous studies). A significant negative correlation between RNHPPD and patient-reported missed timeliness (p=0.0002) as opposed to RNHPPD and patient-reported missed basic care or communication. (In contrast to previous studies). RN skill mix was negatively correlated with missed timeliness (p=0.0004) as opposed to missed basic care or communication. (In contrast to previous studies). | Results have limited generalizability. Sample was convenient. The demographic information of patients not participating is not available. The influence of social desirability on patient self-reports could also impact the study results. However, there results of a comparison of patient reports with those of nursing staff were similar. |

Further research is needed to incorporate simultaneous data collection from both nursing staff and patients that should be conducted for comparison of reports of missed nursing care. Also, studies including other factors found to influence nursing care, like nurse interruptions, multitasking, and technology, should be conducted to explore relationships to the other missed care variables. |

| Lake et al 2016 USA27 | To describe the prevalence and patterns of missed nursing care and explore their relationship to the patient care experience. | Cross-sectional study, secondary data. Participants: patients (n=?) all that were available 10/2006-6/2007) and nurses (n=15,320). | Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey. Nurses responded to the question “On the most recent day you worked, which of the following activities were necessary but left undone because you lacked the time to complete them?” |

Significant negative association between nurse-reported missed care and patient-reported rating of the hospital (p=<0.001), communication with nurses (p=<0.001), they always received help as soon as they wanted (p=<0.01), doctors always communicated well (p=<0.01), their room was always clean (p=<0.001), they received discharge information (p=<0.001), staff always explained medication (p=<0.001). | Methodology does not permit causal inference. There is a possibility of ecological bias. The aggregate data from HCAHPS do not make it possible to link individual patients with varying levels of satisfaction to individual nurses with varying levels of missed care. The HCAHPS data are limited in the degree to which they explore satisfaction with nursing care. Findings cannot be generalized. | Not reported. |

| Moreno-Monsiváis et al 2015 Mexico35 | Determine missed nursing care in hospitalized patients and the factors related to missed care, according to the perception of nurses and patients. | Descriptive cross-sectional study. Participants were patients (n=160) and nurses (n=160). |

Patients and nurses: The MISSCARE survey. The first section included demographic and employment data on the nurses. The second section, called “Missed Nursing Care” had Cronbach’s alpha 0.89, and the third part “Reasons for Missed Nursing Care,” had Cronbach’s alpha 0.90. Patients answered the second part of the survey, and the third section was an open question about reasons for missed nursing care. |

Patient-reported overall nursing care provided: mean 83.29, SD 16.33, Median 86.36. Highest number of patients reported missed mouth care (by 32.1% patients), assistance with hand washing (29.4%), ambulation (20.3%), and support for changing position (17%). Emotional support for the patient and family was reported as missing by 43.7% of patents, followed by visits for assessments by other professionals, (26.2%), and evaluating the effectiveness of drugs (16.7%). 36.2% of patients reported shortcomings in education during hospitalization and 73.7% of patients reported missed discharge plan. Factors contributing to patient-perceived missed care: Lack of staff 18.1%, staff with insufficient experience 13.8%, lack of organization and teamwork 7.5%, lack of staff communication from one shift to another, and the attitude of staff members 5%. | Not evaluated. | Further research is needed about subsequent studies on missed care and associated factors to analyze the impact on patient outcomes. |

| Kalisch et al 2014 USA32 | To determine the extent and type of missed nursing care as reported by patients and the association with patient-reported adverse outcomes. | Cross-sectional study. Participants were patients (n= 729). |

Patients: MISSCARE survey-patient questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha for overall instrument was 0.838. Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales varied across 0.708–0.834 |

Patient-reported missed care was associated with patient’s poorer health status (p= < 0.0001), previous psychiatric problem (p = 0.002) and higher education level (p=0.32) as opposed to patient gender. Patients-reported overall missed care average 1.82 (SD 0.62) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (care never missed) to 5 (care always missed). Mostly basic care 2.29 (SD 1.06), followed by missed communication 1.69 (SD 0.71) and timeliness 1.52 (SD 0.64). Mouth care was missed 50.3% of the time, ambulation (41.3%), lifting to chair (38.8% missed) and bathing (26.9%). Providing information to patients was missed 27% of the time, discussing the treatment plan with patients (26.5% missed), considering the opinions of patients (20.4% missed), the patient knowing who their assigned nurse was (11.2% missed), and listening to the patient (7.8% missed). Timely help to the bathroom was missed 10.9% of the time, responding to beeping monitors (8.8% missed), and answering call lights (8.6% missed). Patient-reported overall missed nursing care was significantly associated with patient-reported skin breakdown (p=<0.05), medication error (p=<0.05), new infection (p=<0.05), IV running dry (p=<0.05) and IV leaking (p=<0.05). Patient-reported missed communication was significantly associated with patient-reported new infection (p=<0.05), IV running dry (p=<0.05) and IV leaking (p=<0.05). Patient reported missed timeliness was significantly associated with patient reported skin breakdown (p=<0.05), new infection (p=<0.05), IV running dry (p=<0.05) and IV leaking (p=0.05). Patient reported basic care was significantly associated with patient-reported medication error (p=<0.05), new infection (p=<0.05), IV running dry (p=<0.05) and IV leaking (p=<0.05). | Results cannot be broadly generalized. The sample was convenient. The demographic information of patients who did not participate is not available. The influence of social desirability on patient self-reports of nursing care could also impact the study results. However, the results of a comparison of patient reports with those of nursing staff were similar. | Further research is needed to demonstrate the effect of engaging patients and families more extensively in their nursing care. |

| Papastavrou et al 2014 Cyprus40 | To explore whether patient satisfaction is linked to nurse-reported rationing of nursing care and to nurses’ perceptions of their practice environment and to identify the threshold score of rationing by comparing the level of patient satisfaction factors across rationing levels. | A descriptive, correlational study. Participants: patients (n= 352) and nurses (n=318). |

Patients: The Patient Satisfaction scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.93. Nurses: Basel Extent of Rationing of Nursing Care. (The BERNCA) scale. Cronbach’s alpha 0.91. The Revised Professional Practice Environment scale (RPPE). Cronbach’s alpha 0.89. |

Mean patient satisfaction level was (range: 1–5) 4.01 (SD 0.64, range 2.29–5). Rationing, even at the lowest level (0.5), is significantly associated with areas of patient satisfaction. | No generalizability of the results. Sample was drawn from all the general state hospitals, which strengthens the findings. Some factors may intervene in the data collection to cause random error, including variations in the administration of the questionnaires in different units and the long period of data collection (1 year). The relatively high amount of non-responding nurses may also indicate the sensitivity of the subject. | Further research is needed about factors influencing care rationing, nurses’ critical thinking and decision-making processes, and the criteria used by nurses to allocate and distribute their resources. |

| Kalisch et al 2012 USA31 | To determine the elements of nursing care that patients can report and to gain insight into the extent and type of missed care experienced by a group of patients. | Descriptive study. Data was collected with semi-structured face-to-face interviews.Participants: patients (n=38). |

Nursing care that patients can report on include, for example, mouth care, bathing, pain medication, listening to patients, being kept informed and response to call lights. Areas of nursing care patients are somewhat able to report on include, for example, hand washing, vital signs, patient education, ambulation, discharge planning and medication administration. Areas of nursing care patients are unable to report on include, for example, nursing assessment, skin assessment and intravenous site care. Frequently missed cared reported by patients included mouth care, listening to patients, being kept informed, ambulation, discharge planning and patient education. Care that was missed sometimes included response to call lights, response to alarms, meal assistance, pain medication and follow-up, medication administration and repositioning. Care that was missed rarely was bathing, vital signs and hand washing. |

Not evaluated. | Further research is needed to investigate missed care in a non-punitive environment. Also specific aspects of nursing care need to be linked to patient outcomes to assist in determining how essential specific elements of care are and the cost-benefit balance of completing them or not. | |

| Shubert et al 2009 Switzerland38 | To describe the levels of implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss acute care and to identify clinically meaningful thresholds of rationing. | Descriptive cross-sectional study. Participants: nurses (n=1338) and patients (n=779). |

Nurses: Basel Extent of Rationing of Nursing Care (The BERNCA) Cronbach’s alpha 0.93. The frequency of five adverse events and complications in inpatients. On a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never” to “often,” nurses indicated the frequency of these adverse events in their patients over the past year. Overall patient satisfaction with the care they received during their stay was assessed with one question using a 5-point Likert type scale. |

Rationing level of 2 was significantly associated with patient satisfaction (p=<0.001). | Methodology allows no causal conclusions. Generalizability of the results is limited. The rationing levels may be higher than shown. It is impossible to select a random sample of the entire nurse population. Except for patient satisfaction, nurse reports of negative events in care were used as the dependent variables, rather than more objective data. The nurse reports of adverse events and the rationing data refer to different time frames (the preceding year for outcomes, the last 7 working days for rationing). | Further research is needed on validation of nurse reports as measures of incidents. Clinician-reported incidence of adverse events may be a type of measure worth using more extensively in research in this area. |

| Schubert et al 2008 Switzerland/USA37 | To explore the association between implicit rationing of nursing care and selected patient outcomes, adjusting for major organizational variables. | Descriptive cross-sectional study. Participants: patients (n=779) and nurses (n=1338) |

Nurses: Basel Extent of Rationing of Nursing Care (BERNCA). Cronbach’s alpha 0.93. Practice Environment Scale-Nursing Working Index (PES-NVI), three subscales, Cronbach’s alphas 0.90, 0.84 and 0.73. Adapted version of the International Hospital Outcomes Study questionnaire. Overall patient satisfaction was assessed with one 4-point Likert-type question. |

Based on the mean nurse level, on average, tasks were omitted slightly less frequently than “rarely” (mean 0.82, SD 0.53, median 0.77, range 0–2.68), on a scale 0–3. In the fully adjusted model, 0.5 unit increase in rationing levels reported by nurses was associated with a 37% decrease in the odds of patients reporting satisfaction with care. However, the association was only marginally significant (p=0.08). |

Methodology does not allow causal conclusions. Generalizability of the results is limited. All outcomes in this study except patient satisfaction were assessed through nurse reports. | Further research is needed to deepen understanding of rationing. Studies need to incorporate prospectively collected data on patient outcomes sensitive to nursing care quality and investigate the applicability and sensitivity of rationing and the BERNCA instrument internationally. Defining the threshold when rationing begins to affect patient outcomes negatively is also needed. |

Stage 4: Charting the Data

The data chart (Table 1) included the following topics: Authors, Publication year, Country, Purpose, Methods and Sample, Instruments, Main Results, Validity/Reliability, and Implications for Further Research. These variables were central in answering the research questions.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

Stage five included descriptive numerical summary analysis as well as thematic analysis. Descriptive numerical summary included basic numerical analysis of the extent and nature of the included studies.26,28 Thematic analysis in scoping review resembles qualitative data analysis; researchers may thus consider using qualitative content analytical techniques. Therefore, the data were analyzed with content analysis, where it was organized thematically and presented according to the research questions.28 Themes were not preconceived but emerged inductively from the included articles,29 as scoping review does not seek to synthesize evidence on a particular topic, but rather, to describe the account of available research.26,28 The PRISMA-Sco checklist for scoping review was used to guide the reporting of the results.30

Results

Studies Involving Patients’ Perceptions About Missed Care

Description of Studies and Methods Used

The included studies (n=13), published between 2008 and 2018, were from the USA (n=5), Switzerland (n=3), South Korea (n=1), Cyprus (n=1), Mexico (n=1), and the UK (n=1), and one combined data from eight countries (n=1, Table 1).

The data included one qualitative study using phenomenological approach with data collected using in-depth, semi-structured interviews of 38 patients.31 Other studies (n=12) were quantitative in nature. Five studies inquired about missed nursing care directly from the patients. Sample sizes in these varied between 160 and 1555.32–36 Seven studies collected data about patients’ satisfaction with care and compared it to missed care data collected from nurses. The sample size in these varied between 352 and 66,348 patients27,37–42 Quantitative studies (n=12) were descriptive cross-sectional studies using structured questionnaires and statistical analysis.

All participants were adults and the studies were conducted in different clinical hospital settings: medical (n=11), surgical (n=11), rehabilitation unit (n=2), mixed unit (n=1), intensive care unit (n=1), gynecological unit (n=2), and maternity care (n=1).

Instruments Used to Measure Patients’ Perceptions on Missed Care

In the included studies, three different instruments were used to examine patients’ perceptions on missed care: the MISSCARE Survey – Patient,32–34 MISSCARE Survey,35 and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Systems survey (also known as the HCAHPS®).36

The MISSCARE Survey – Patient, developed by Kalisch (2014), was used in three studies.32–34 In these studies, patients were asked to identify whether nursing care was provided during their hospitalization. This instrument contains three sections: 1. Demographic characteristics and health status (including patient age, sex, race, education, marital status, hospitalized days, health status, diagnosis, and disease history), 2. Elements of nursing care, and 3. Adverse events. The section of elements of nursing care contains 13 items and uses 5-point Likert-type scales for measurement of communication and basic care (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = usually, and 5 = always) and for measurement of timeliness (from 1 to 30 mins). The mean of all 13 items is used as a total score for the scale, and the potential range of scores is 1 to 5.32–34

The MISSCARE survey, originally developed to measure missed nursing care and the reasons for it from nurses’ perspective, was used to measure patients’ perspective of missed care in one study.35 It contains two parts. Part A consists of 24 listed elements of nursing care. Nurses are asked to indicate how frequently each nursing care element was missed in their unit by all staff, including themselves, using the scale “rarely”, “occasionally”, “frequently”, “always”, or non-applicable. Part B consists of 17 reasons listed for missed care. Nurses are asked to rate each item using the scale “significant factor”, “moderate factor”, “minor factor”, or “not a reason for unmet nursing care”. In addition, demographic/background data contain characteristics of the respondent’s gender, years of working experience, highest nursing degree, current employment status and unit.35

One study used the HCAHPS survey,36 which was originally developed for measuring patients’ perceptions of their hospital experience41 and includes 32 items consisting of nine-key domains pertaining to patient care. The survey has items that ask whether and at what frequency patients experienced a critical aspect of hospital care, rather than whether they were satisfied with their care. The survey also includes four screener items directing patients to relevant questions, five items to adjust for the mix of patients across hospitals, and two items supporting Congressionally-mandated reports.36

The Main Findings of the Studies

Missed Care Reported by Patients

Patients can recognize and report several aspects of missed care.31 MISSCARE Survey – Patient divides missed care into three domains: missed basic care, missed communication, and timeliness. In studies using this questionnaire,32–34 patients (n=210-729) reported mostly missed basic care (mean 2.29–3.57, SD 1.06–1.23), followed by missed communication (mean 1.69–2.02, SD 0.71–0.83) and timeliness (mean 1.29–1.52, SD 0.54–0.64).32–34

MISSCARE Survey – Patient views missed care as unperformed nursing activities. To begin with missed basic care, mouth care (missed 32.1–50.3% of the time), ambulation (missed 20.3–41.3% of the time), lifting to a chair (missed 38.8% of time), bathing (missed 26.9% of time), assistance with hand washing (missed 29.4% of time) and support for chancing position (missed 17% of time) were recognized as missed.32 Moreover, activities categorized as missed communication included nurses providing necessary information to patients and families (missed 11.9–27% of the time), discussing the treatment plan with patients (missed 26.5% of time), considering patient’s opinions (missed 20.4% of time), patient knowing who their assigned nurse was (missed 11.2% of time), and listening to patient (missed 7.8% of time).32 Finally, activities related to timeliness were listed, including timely help to the bathroom (missed 10.1–10.9% of the time), fulfilling call light requests (missed 10.3–16.4% of time) and responding to beeping monitors (missed 8.8% of time) as well as call lights (missed 8.6% of time).32

In the study using MISSCARE Survey,35 patients (n=160) also mostly reported missed basic care, followed by missed individual needs, which included activities such as emotional support for the patient or family (reported as missing by 43.7% of patients), visits for assessments by other professional such as physician or nutritionist (reported as missing by 26.2% of patients), and evaluating the effectiveness of drugs (reported as missing by 16.7% of patients), as well as patient education during hospitalization (reported as missing by 36% of patients) and discharge plan (reported as missing by 73.7% of patients).35 Furthermore, one-third (38%) of the patients (n=1125) reported at least one nursing activity from the HCAHPS survey as missed during their hospital stay.36

Factors Associated with Missed Care

Several patient-related and staff-related factors were associated with missed care. Among patient-related factors, patients with poorer health status and patients with mental health problems reported more missed care,32,36 as did patients who experienced adverse events during hospitalization compared to those who did not; a significant positive association was thus found between patient-reported missed care and patient-reported skin breakdown, medication error, new infection, intravenous infusion (IV) running dry and IV leaking.32 Dabney & Kalisch (2015) found patients’ older age to be a predictor of missed timeliness,33 as opposed to Orique et al (2107).36 Similarly, Kalisch et al (2014) found that patients with lower education level reported more missed care,32 whereas Orique et al (2017) found no significant association between patient’s education level and missed care.36 Patient’s gender did not predict missed care.32,36

Staff-related factors contributing to missed care perceived by patients (n=160) included lack of staff (18.1%), staff with insufficient experience (13.8%), lack of teamwork (7.5%), lack of staff communication between shifts and the attitude of staff members (5%).35

Patient-reported missed care was also associated with nurse staffing levels. The total number of productive hours worked by registered nurses, total number of productive hours worked by all nursing staff members, and the proportion of registered nurses in the total number of nursing staff members had a significant negative correlation with missed patient reported timeliness as opposed to patient-reported missed basic care or communication.33 However, in another study34 the actual patient-to-nurse ratio was not significantly associated with patient-reported missed care while patients’ perceptions of staffing adequacy had a significant positive association with patient-reported missed communication and patient-reported missed basic care. Nurse-perceived staffing adequacy had a significant inverse relationship with patient-reported missed communication but no significant relationship with patient-reported missed basic care.34

Patients’ Satisfaction

Missed care was also connected with the outcomes of care, the outcome mostly being patient satisfaction. In the studies reviewed, patient-reported satisfaction with the nurses’ care showed a significant negative association with nurse-reported missed care.27,37–41 Even low levels of nurse-reported missed care associated significantly with low patient satisfaction.40 Furthermore, a significant negative association was found between nurse-reported missed care and patients rating their care as excellent,37 as well as between nurse-reported missed care and patient-reported patient-centered care.42

Implications and Suggestions for Further Research in the Studies

In most of the studies, the authors reported suggestions for further studies. There is variation in this as well. Suggestions for future research referring to patients’ perspective of missed care are limited. Authors agree that data should be collected from both nursing staff and patients, which would permit comparison of the reports of missed nursing care.33 Future research is also needed to explore the effect of engaging patients and families more extensively in their nursing care,32 and to study the expectations of patients regarding professional hospital care.39

Discussion

Patients’ perspective in missed care literature is very limited, as studies were only included in the review if they had patients providing missed care data or examined patients’ perceptions of nurse-reported missed care and yet, in the search with no time limit, only 13 studies, published 2008–2018, were identified. The selected studies included mostly data about patients’ satisfaction compared to nurse-reported missed care whereas direct information on patients’ perceptions on missed care is extremely scarce: only six studies included these data.

Research on this field has mainly focused on the amount and nature of missed care as tasks experienced by patients and the factors associated with it whereas no causal conclusions can be made about these relationships. In the reviewed studies, patients mostly reported missed basic care, followed by missed communication and missed timeliness.32–34 The studies are from several countries and the results on the amount of missed care experienced by patients are similar, potentially indicating an international problem. The estimation of a shortage of two million nurses by 20307 suggests an increasing amount of missed care requiring attention since patient-reported missed care is associated with patient-reported adverse events during hospitalization.32

Some patient- and nurse-related background factors were associated with missed care. However, the results about patients’ education level and age as predictors of missed care were conflicting,32,36 as were the results about an association between staffing level and missed care, highlighting the need for further research. The determination of staffing level varies between studies, making it more difficult to combine these results. Cho et al (2017) used patient-to-nurse ratio (the average number of patients at midnight over the past 7 days divided by the average number of nurses per shift) to determine staffing level, and this was not significantly associated with patient-reported missed care,34 whereas Dabney & Kalisch (2015) used three variables to measure nurse staffing: RNHPPD (the total number of productive hours worked by RNs in a designated inpatient unit during a specific calendar month, divided by the total number of patient days for the corresponding unit and month), NHPPD (total number of productive hours worked by all nursing staff members in an inpatient unit during a designated calendar month, divided by the total number of patient-days for the corresponding unit and month), and RN SKILL MIX (the proportion of RNs in the total number of nursing staff members). These variables were not associated with patient-reported communication and basic care, as opposed to missed timeliness,33 which runs counter to previous studies that highlight the association between lower staff levels and increased amount of missed care.1,21 Nurse-reported missed care was significantly associated with patients’ satisfaction with care, potentially indicating the mediating effects of missed care on the relationship between nurse staffing and patients’ experiences.34

Patient-perceived staffing adequacy was, however, significantly associated with patient-reported missed care, and lack of staff was named as the primary factor contributing to missed care perceived by patients, which raises the questions of how patients recognize missed care and how patients perceive staffing adequacy. Patients may not be able to separate nurses from other health-care professionals or they may not recognize care needs with the same scope as professionals; in addition, each patient also has their individual expectations for nursing care. Among the studies reviewed, different questionnaires were used to measure missed care perceived by patients. The questionnaires included different numbers of listed nursing care tasks, and patients were asked whether or not this task was performed during their hospitalization. This, however, does not say what is important to patients or what nursing care they and their family members value the most; further research would thus be useful to examine how patients identify missed care, what activities they consider that nurses perform, and how they define care that is completed in correspondence with their views on their care needs.

These results support the conceptual models developed to understand missed care, as there were organization-related factors, such as resources and lack of teamwork, identified as contributors to missed care perceived by patients. Moreover, missed care was associated with adverse events and lower patient satisfaction, thus resulting in negative patient outcomes, which could be an indicator of care quality. In these conceptual models, nurses are decision-makers who, in situations that require prioritization, make a choice about what activities to perform and what to leave out. In addition to conceptual models, these results could also be viewed through the framework of structuration theory.15,17 In this framework, nurses would be acknowledged as agents who, based on their education and experience, have knowledge about the necessary nursing activities they should provide, and are able to reflect upon how they carry out these activities. Nurses as agents must also make choices on whether or not to perform a specific task. Nurses carry out their work intentionally, based on their knowledge and the expected outcomes of these activities to patients or themselves. In addition to personal choices, nurses practice their work in a specific social environment and structural system which, for example, provides the resources available.18 Based on these results, basic care was mostly missed; this would indicate that nurses mostly decide that the expected outcome of missed basic care would not be as severe as that of some other nursing activities. However, based on these articles reviewed, no conclusions can be drawn about nurses’ decision process.

The imbalance between patients’ care needs and the resources available forces nurses to prioritize between patients and different nursing tasks, making it an ethical challenge.20 Prioritization has consequences for nurses as well as patients as it may cause nurses to experience moral distress as well as feelings of frustration and powerlessness. The consequences for patients include missed care, dissatisfaction and loss of trust,43 as the prioritization process leaves patients vulnerable to unmet care needs.3 However, the ethical perspective on missed care was not adduced in the reviewed articles, and further research is needed on this topic.

This study has strengths and limitations. The strengths include that the search was comprehensive, using six databases, and conducted in collaboration with an information specialist. In addition, the PRISMA-ScR checklist for scoping reviews was used to guide the reporting of the results.30 The limitation is that only English-language articles were included in the review, and it is therefore possible that relevant articles in languages other than English were left out. However, the studies in the selected articles were conducted internationally in different countries and cultures. The term “patient perspective” was left out of the search phrases because of possible difficulties of including all the terms describing it, as a result of which something relevant might be left out. Even without this, it was possible to go through all the found articles by title.

Further research is needed to form a clear definition of missed care and to state what the definition includes, as it is challenging to examine something that does not exist. In addition, further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of missed care as perceived by patients and the factors influencing it, including different organizational structures, as the literature on this topic is limited and the existing results were partly conflicting. Based on this review, it is not possible to identify a specific nursing context that encloses missed care, which is why future research is needed within a variety of patient groups and health-care contexts, as so far, all the participants have been adult patients in clinical hospital setting. Missed care has been investigated in aged care from the nurses’ perspective, and one study showed that additional unplanned care44 was most frequently missed, whereas basic care was mostly missed among the medical patients in the studies reviewed. As populations age in many parts of the world, prioritization might also increase in older people care in the future.45 Furthermore, in the future it would be useful to examine how patients identify missed care and to explore the ethical perspective on missed care, as it was not addressed in the articles reviewed.

Conclusion

Research about missed care from patients’ perspective is scarce, although anticipated to be an extremely common phenomenon. Patients mostly report missed basic care, followed by missed communication and timeliness. The included articles pointed out that researchers can investigate patient’s perspective of missed nursing care using validated instruments; however, we suggest also asking patients’ views more broadly. In addition, patients’ perception on some of the missing nursing tasks and areas had strong correspondence with previously studied nurses’ perception. However, since identification of missed care is not simple, it presents, and will continue to present, a great challenge for researchers, clinicians and patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anna Vuolteenaho for the language check of this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Griffiths P, Recio-Saucedo A, Dall’Ora C, et al. The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1474–1487. doi: 10.1111/jan.13564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recio-Saucedo A, Dall’Ora C, Maruotti A, et al. What impact does nursing care left undone have on patient outcomes? Review of the Literature. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:2248–2259. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones T, Hamilton P, Murry N. Unfinished nursing care, missed care, and implicitly rationed care: state of the science review. Int J NursStud. 2015;52:1121–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schubert M, Ausserhofer D, Desmedt M, et al. Levels and correlates of implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals e a cross sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(2):230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.inurstu.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim KJ, Yoo MS, Seo EJ. Exploring the influence of nursing work environment and patient safety culture on missed nursing care in Korea. Asian Nurs Res. 2018;12:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackman I, Henderson J, Willis E, et al. Factors influencing why nursing care is missed. J Clin Nurs. 2014;24:47–56. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drennan V, Ross F. Global nurse shortages-the facts, the impact and action for change. Br Med Bull. 2019;1–13. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schubert M, Glass T, Clarke S, et al. Validation of the Basel extent of rationing of nursing care instrument. Nurs Res. 2007;56(6):416–424. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299853.52429.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D, et al. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001;20(3):43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ausserhofer D, Zander B, Busse R, et al. Prevalence, patterns and predictors of nursing care left undone in European hospitals: results from the multicountry cross-sectional RN4CAST study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):126–135. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sochalski J. Is more better? The relationship between nurse staffing and the quality of nursing care in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42(2):II67–II73. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109127.76128.aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Kandari F, Thomas D. Factors contributing to nursing task incompletion as perceived by nurses working in Kuwait general hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(24):3430–3440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucero R, Lake E, Aiken L. Nursing care quality and adverse events in US hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(15–16):2185–2195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03250.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalisch B. Missed nursing care: a qualitative study. J Nurs Care Qual. 2006;14(4):306–313. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200610000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalisch B, Landstrom G, Hinshaw A. Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1509–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalánková D, Zianková K, Kurucová R. Approaches to understanding the phenomenon of missed/rationed/unfinished care – a literature review. Central Eur J Nurs Midwifery. 2019;10(1):1005–1016. doi: 10.15452/CEJNM.2019.10.0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucero RJ, Lake ET, Aiken LH. Variations in nursing care quality across hospitals. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(11):2299–2310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05090.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groves PS, Meisenbach RJ, Scott-Cawiezell J. Keeping patients safe in healthcare organizations: a structuration theory of safety culture. J Adv Nurs. 2019;76(8):1846–1855. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05619.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T, Willis E, Amorim-Lopes M, Drach-Zahavy A. Advancing the science of unfinished nursing care: exploring the benefits of cross-disciplinary exchange, knowledge integration and transdisciplinarity. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:905–917. doi: 10.1111/jan.13948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suhonen R, Scott A. Missed care: a need for careful ethical discussion. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(5):458–551. doi: 10.1177/0969733018790837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalisch B, Xie B. Errors of omission: missed nursing care. Western J Nurs Res. 2014;36(7):875–890. doi: 10.1177/0193945914531859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho S-H, You SJ, Song KJ, Hong KJ. Nurse staffing, nurses prioritization, missed care, quality of nursing care, and nurse outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;e12803. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hessels AJ, Wurmser T. Relationship among safety culture, nursing care and Standard Precautions adherence. Am J Infect Control. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coulter A. Paternalism or partnership? Patients have grown up- and there’s no going back. Br Med J. 1999;319:719–720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feste C, Anderson RM. Empowerment: from philosophy to practice. Patient Educ Counsel. 1995;26:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00730-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lake E, Germack H, Viscardi M. Missed nursing care is linked to patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional study of US hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:535–543. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010;5(69). doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kastner N, Tricco A, Soobiah C, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(144). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA.ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalisch B, McLaughlin M, Dabney B. Patient perceptions of missed nursing care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(4):161–167. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(12)38021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalisch B, Xie B, Dabney B. Patient-reported missed nursing care correlated with adverse events. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(5):415–422. doi: 10.1177/1062860613501715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dabney B, Kalisch B. Nurse staffing levels and patient-reported missed nursing care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(4):306–312. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho S, Mark B, Knafl G, et al. Relationships between nurse staffing and patients’ experiences, and the mediating effects of missed nursing care. J Nurs Scholarship. 2017;49(3):347–355. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreno-Monsiváis M, Moreno-Rodríguez C, Interial-Guzmán MG. Missed nursing care in hospitalized patients. Aquichan. 2015;15(3):318–328. doi: 10.5294/aqui.2015.15.3.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orique S, Patty C, Sandidge A, et al. Quantifying missed nursing care using the hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems (HCAHPS) survey. J Nurs Admin. 2017;47(12):616–662. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shubert M, Glass T, Clarke S, et al. Rationing of nursing care and its relationship to patient outcomes: the Swiss extension of the International Hospital Outcomes Study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(4):227–237. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schubert M, Clarke S, Glass T, et al. Identifying thresholds for relationships between impacts of rationing of nursing care and nurse- and patients-reported outcomes on Swiss hospitals: A correlational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(7):884–893. doi: 10.1016/j.inurstu.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruyneel L, Li B, Ausserhofer D, et al. Organization of hospital nursing, provision of nursing care, and patient experiences with care in europe. Med Care Res Rev. 2015;72(6):643–664. doi: 10.1177/1077558715589188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papastavrou E, Andreou P, Tsangari H, et al. Linking patient satisfaction with nursing care: the case of care rationing – a correlational study. BMC Nurs. 2014;13:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-13-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aiken L, Sloane D, Ball J, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospital care and nurses in England: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2018;8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachnick S, Ausserhofer D, Baernholdt M, et al. Patient-centered care, nurse work environment and implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals: A cross-sectional multi-centered study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;81:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.inurstu.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suhonen R, Stolt M, Habermann M, et al. Ethical elements in priority setting in nursing care: A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;88:25–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nurstu.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henderson J, Willis E, Xiao L, et al. Missed care in residential aged care in Australia: an exploratory study. Collegian. 2017;24:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2016.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amalberti R, Vincent C, Nicklin W, et al. Coping with more people with more illness. Part 1: the nature of the challenge and the implications for safety and quality. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(2):154–158. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]