Abstract

Various lines of evidence suggest that neonatal exposure to general anesthetics, especially repeatedly, results in neuropathological brain changes and long-term cognitive impairment. Although progress has been made in experimental models, the exact mechanism of GA-induced neurotoxicity in the developing brain remains to be clarified. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) plays an important role in synaptic plasticity and cognitive performance, and its abnormal reduction is associated with cognitive dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. However, the role of SIRT1 in GA-induced neurotoxicity is unclear to date. In this study, we found that the protein level of SIRT1 was inhibited in the hippocampi of developing mice exposed to sevoflurane. Furthermore, the SIRT1 inhibition in hippocampi was associated with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) downregulation modulated by methyl-cytosine-phosphate-guanine–binding protein 2 (MeCP2) and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB). Pretreatment of neonatal mice with resveratrol nearly reversed the reduction in hippocampal SIRT1 expression, which increased the expression of BDNF in developing mice exposed to sevoflurane. Moreover, changes in the levels of CREB and MeCP2, which were considered to interact with BDNF promoter IV, were also rescued by resveratrol. Furthermore, resveratrol improved the cognitive performance in the Morris water maze test of the adult mice with exposure to sevoflurane in the neonatal stage, without changing motor function in the open field test. Taken together, our findings suggested that SIRT1 deficiency regulated BDNF signaling via regulation of the epigenetic activity of MeCP2 and CREB, and resveratrol might be a promising agent for mitigating sevoflurane-induced neurotoxicity in developing mice.

1. Introduction

Every year, millions of children undergo diagnostic or surgical procedures under general anesthesia globally, and the long-term potential neurotoxic effects of general anesthetics (GAs) on the infant brain is a worldwide concern. Solid evidence from rodent and nonhuman primate models has proved that exposure to GAs, especially to those targeting the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor and/or the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, during the brain growth spurt period can cause neuroapoptosis, synaptic dysfunction, and long-term behavioral abnormality [1–10]. Although growing preclinical data has been accumulated, ambiguity still exists in clinical studies [11–15]. A few clinical trials showed that a single brief exposure to GAs during the early life did not increase the risk of neurocognitive impairment [16–21]. However, the secondary analysis of the Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids study suggested that exposure to multiple procedures under general anesthesia before the age of 3 was associated with a specific pattern of deficits in neuropsychological tests, which was corroborated in experimental models [22]. Although these findings could not show a direct causality between neuropsychological deficits and GA exposure, they presented some useful hints to further evaluate the effects of GA on the neurodevelopment of children.

BDNF is a pivotal regulator of neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and other regions of the developing brain [23, 24]. It has been shown that BDNF plays an important role in the formation of certain types of learning, memory, and mood regulation [25, 26]. Previous studies have shown that neonatal exposure to isoflurane and propofol reduces the production of mature BDNF and thus triggers neuroapoptosis [1, 27–29]. Moreover, a persistent reduction in hippocampal BDNF levels in adult rats that were neonatally exposed to isoflurane results in the insufficient synthesis of synaptic proteins and contributes to the cognitive impairment. This effect is mediated by the occupation of the promoter region of exon IV of BDNF with transcriptional factors such as DNA methyltransferase 1, MeCP2, and histone deacetylase 2 [30]. However, it remains unclear how neonatal isoflurane exposure regulates the activity of these transcriptional factors.

SIRT1 is a nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase belonging to the class III histone deacetylase family. SIRT1 is indispensable for synaptic plasticity and cognitive function under physiological conditions [31, 32]. Furthermore, activation of SIRT1 with resveratrol, a natural polyphenol agonist of SIRT1, mitigated neuronal injury by regulating the expression of BDNF in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases [32–36]. In addition, resveratrol was also found to mitigate age-related cognitive deficits [37–39]. However, whether SIRT1 is involved in sevoflurane exposure-induced cognition impairment and whether resveratrol can provide neuroprotection against the neurotoxicity of sevoflurane still need to be further investigated.

In the present study, we aimed to examine the role of SIRT1 in long-term cognitive changes induced by neonatal exposure to sevoflurane. Moreover, we tested the hypothesis that resveratrol restored anesthesia-induced SIRT1 reduction and improved long-term cognitive performance by modulating its substrates (including MeCP2 and CREB) and further influencing BDNF signaling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Anesthesia and Treatment

C57BL/6J mice at 16-18 days of gestation were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Tongji Medical College (Wuhan, China). The mice were kept in cages in suitable environmental conditions (22–24°C, 12-hour light/dark cycle) and were put on a diet of commercial pellet, without water restrictions. Both female and male pups were used in the studies. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The committee of Tongji Medical College has approved the animal protocol.

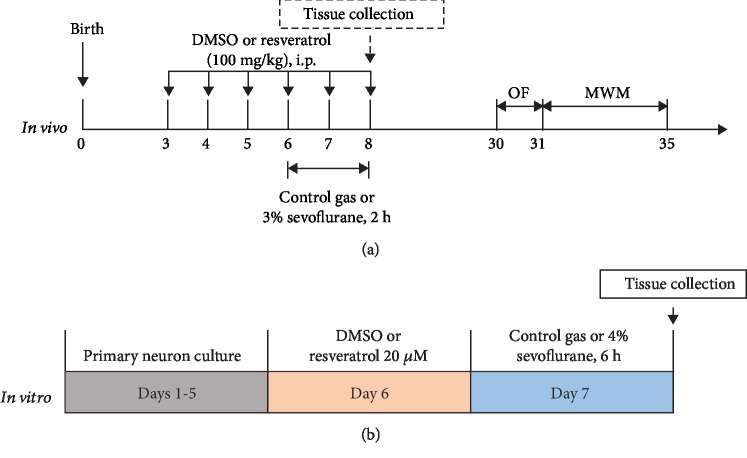

As shown in Figure 1(a), the neonatal mice were assigned randomly to four groups: control plus DMSO, control plus resveratrol treatment, sevoflurane plus DMSO, and sevoflurane plus resveratrol. The mice in anesthesia groups received 3% sevoflurane plus 60% oxygen (balanced with nitrogen) 2 h daily form postnatal day (P)6 to P8 in the induction chamber as previous studies described [40–42]. The induction flow rate was 2 L/min for the first three minutes (for induction) and then 1 L/min with the rest of the anesthesia (for maintenance). Mice in the control conditions were separated from dams for the same period of time and exposed to the control gas (60% oxygen balanced with nitrogen). The concentrations of sevoflurane and oxygen were continuously monitored with an infrared probe (Ohmeda S/5 Compact, Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, CO) during anesthesia. The anesthesia chamber was kept in a homoeothermic incubator to maintain the experimental temperature at 32°C ± 0.5°C. Previous studies have confirmed that the anesthesia with 3% sevoflurane for 2 h did not significantly change pH values, oxygen partial pressure, or carbon dioxide partial pressure in young mice as compared to those in the control group. Therefore, blood gas analysis of the mice was not conducted in our studies. In the intervention studies, 100 mg/kg resveratrol (dissolved in DMSO and diluted with saline) was administrated intraperitoneally (i.p.) on P3, P4, P5, and 1 h prior to isoflurane or control gas exposure from P6 to P8. Mice in the control group received 50 μL DMSO solution (30 μL of DMSO dissolved in 1 mL of saline), which is the vehicle of resveratrol. The number of animals used in each group is reported in Supplementary .

Figure 1.

Experiment protocol in vivo and in vitro. (a) In vivo: 3-day-old mice were pretreated with DMSO or resveratrol via intraperitoneal injection daily for 6 consecutive days and received control gas exposure or 3% sevoflurane for 2 h from P6 to P8. After exposure, some of the mice were decapitated and tissue samples were collected for RT-PCR and western blotting; the other mice were returned to dams and received the OF test and MWM test from P30 to P35. (b) In vitro: after 5-day culture, primary neurons were incubated with DMSO or 20 μM resveratrol followed by 6-hour exposure to control gas or 4% sevoflurane.

2.2. Harvest of Brain Tissues

Mice were allowed to completely recover from anesthesia. One hour after the end of sevoflurane anesthesia on P8, the mice were euthanized and decapitated. For western blot analysis, the harvested hippocampus tissues were homogenized on ice using RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) plus 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitors (Promoter, Wuhan, China), and phosphatase inhibitors (Boster, Wuhan, China). The lysates were collected and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and total protein was quantified with a BCA assay kit (Boster).

2.3. Primary Neurons and Cell Treatment

C57BL/6J mice (The Laboratory Animal Center of Tongji Medical College, China) at 16-18 days of gestation were euthanized with carbon dioxide. Embryonic hippocampi were dissected as previously described [43]. The neurons were digested with 0.05% trypsin for 30 min at 37°C. Then, the dissociated cells were plated at a density of 100,000 cells/well in poly-D-lysine-coated 6-well plates with DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, Waltham, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA). Four hours after plating, the medium was replaced with serum-free B27/neurobasal medium. The medium was replaced every 3 days.

The neurons were randomly assigned to four groups: control plus DMSO, control plus resveratrol, sevoflurane plus DMSO, and sevoflurane plus resveratrol, to receive incubation of 0.1% DMSO (the vehicle of resveratrol), 20 μM resveratrol, 0.1% DMSO, and 20 μM resveratrol, respectively, at the sixth day of culture for 24 h. After seven days of plating, the neurons received 4.1% sevoflurane or control gas (21% O2, 5% CO2, and 70% nitrous oxide) exposure for 6 h (Figure 1(b)).

2.4. Neuron Lysis and Protein Quantification

The cells were harvested at the end of the experiments, and neuronal pellets were detergent-extracted on ice using RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) plus 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitors (Promoter, Wuhan, China), and phosphatase inhibitors (Boster, Wuhan, China). The lysates were collected and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and total protein was quantified with a BCA assay kit (Boster).

2.5. Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from hippocampal tissues with a TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA with an RT-PCR kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Real-time RT-PCR was carried out as follows: initial denaturation for 1 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 20 s at 58°C, and 45 s at 72°C. The PCR primers were as follows: Sirt1 forward (5′-ATCGTTACATATTCCACGGTGCT-3′), Sirt1 reverse (5′-CACTTTCATCTTCCAAGGGTTCT-3′); BDNF forward (5′-GCCTCCTCTACTCTTTCTG-3′), BDNF reverse (5′-GGATTACACTTGGTCTCGT-3′). The intensities of the bands were analysed with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

The harvested brain tissues and cells were subjected to western blotting as described by Narasimhan et al. [44]. In brief, hippocampal tissue lysates (40 μg protein) and primary neuron lysates (20 μg protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies, and the antibodies used were SIRT1 (1 : 500, Affinity, OH, USA), BDNF (1 : 500, Affinity, OH, USA), acetyl-MeCP2 (AcMeCP2) (1 : 1000, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), MeCP2 (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) (1 : 1000, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), CREB (1 : 500, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), synapsin1 (1 : 5000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), VGluT1 (1 : 500, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95) (1 : 500, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and Homer1a (1 : 2000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). To verify the uniformity of the protein loading and transfer efficiency across the test samples, the membranes were reprobed with GAPDH. Immunoreactive bands were developed with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Boster), visualized by using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ChemiDoc, Bio-Rad, USA), and normalized to GAPDH expression.

2.7. Coimmunoprecipitation

The hippocampi were dissected from neonatal rats and then homogenized in immunoprecipitation buffer with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors, and the protein concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/mL. Samples (500 μL) were precleared with nonspecific rabbit IgG (Sigma) followed by adsorption on protein G-Sepharose (Millipore). Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of rabbit anti-SIRT1 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-AcMeCP2 (Millipore), and anti-CREB1 (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies, followed by adsorption to protein G-Sepharose. In control experiments, the antibodies were replaced with nonspecific rabbit IgG (Sigma). For western blotting, immunoprecipitates were loaded on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto PVDF membranes. The blots were incubated with specific primary antibodies and then with peroxidase-conjugated species-matched secondary antibodies. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

2.8. Open Field Test

The locomotor and exploratory activities of the animals were monitored by the open field test. The apparatus was a white box with a 50 × 50 cm field surrounded by 40 cm high walls. The mice were placed in the middle of the box and were given 5 min to move freely about the apparatus. Activity in the field was measured using an automated video-tracking system (AVTAS v3.3; AniLab Software and Instruments Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). The total distance traveled and the average speed were monitored to calculate locomotor activity. After each session, the floor and walls of the field were cleaned with 75% ethanol to eliminate olfactory cues. To avoid experimenter bias, all behavioral experiments were performed by two experimenters who were blind to the experimental protocol. In addition, the data was analysed by another experimenter who was blind to the experimental protocol.

2.9. Morris Water Maze Test

The mice (n = 8 per group) used for the MWM test were weaned at P22 and tested from P31 to P35. The Morris water maze (MWM) test was performed as previously described [45–47] with small modifications. As shown in Supplementary , the MWM test was conducted in two separate rooms: test room and computer room. In the test room, there was a round and steel pool (diameter, 120 cm; height, 60 cm), which was filled up with water. Four graphic signals were hung on the walls as visual cues for the navigation of mice in the MWM. Swimming activity of each mouse was tracked via a camera mounted overhead and was analysed by AVTAS v3.3, an automated video-tracking system. Four platforms (platforms ①, ②, ③, and ④) and four quadrants (quadrants 5, 6, 7, and 8) were generated automatically by the system, and platform ② and quadrant 6 were defined as the target platform and target quadrant (Supplementary Figures and ). The data was recorded automatically in a computer, which contains this system and was put in the computer room. By adding powdered milk, the water was rendered opaque. A platform (diametric distance, 10 cm) was placed in the target quadrant (platform ② in quadrant 6) and was 1.0 cm lower than the water level (Supplementary Figures and ). All mice received 5-day training followed by a probe trial. In the training days, the mice were trained to swim to a hidden platform in four trials per day for 5 days (P31-P35). They are allowed to find the platform within 60 s and then have a 15-second stay in the platform. If a mouse failed to find the platform within 60 s, it was guided to the platform and allowed to stay there for 15 s. The mice were tested individually and placed into various quadrants of the pool. The daily order of entry into individual quadrants is randomized, and the mice were allowed to rest at least 30 min before starting the training in the other quadrants. Two hours after the end of the training trials on the fifth day, the probe trial was performed in which the platform is removed from the pool to measure spatial bias. The time spent in searching and mounting the hidden platform in the training trial (escape latency), the distance traversed to reach the hidden platform in the training trial (escape path length), the duration of time spent in each quadrant, and the number of platform crossings in the probe trial were used to assess spatial learning and memory of different group mice. To avoid experimenter bias, all behavioral experiments were performed by two experimenters who were blind to the experimental protocol. In addition, the data was analysed by another experimenter who was blind to the experimental protocol.

2.10. Statistics

The data obtained from the biochemistry studies and behavioral tests were presented as the mean ± SEM and were analysed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). Student's t-test was used to compare the differences between the control and sevoflurane anesthesia groups. Two-way repeated-measured analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the differences in escape latency and escape path length in the MWM test. Two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test was used to evaluate the interaction of groups (control vs. anesthesia) and treatments (resveratrol vs. vehicle) on the amounts of SIRT1, BDNF, p-CREB, CREB, AcMeCP2, MeCP2, synapsin1, VGluT1, PSD95, and Homer1a. The data of escape latency and escape path length obtained from the acquisition training (P31-P35) of the MWM were analysed using a two-way ANOVA (treatment × trial time) with repeated measures (trial days) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. The data of time spent in the target quadrant and platform crossing times obtained from probe trial (P35) were analysed using two-way ANOVA (group × treatment) without repeated measures followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test to determine significant differences between experimental groups. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

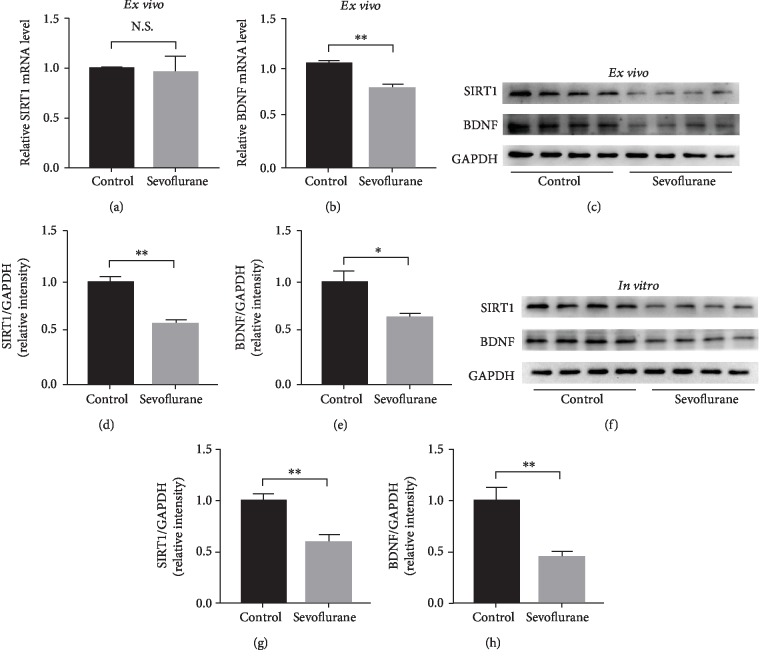

3.1. Sevoflurane Exposure Inhibited SIRT1 Expression and Decreased BDNF Expression Ex Vivo and In Vitro

In the ex vivo experiment, 6-day-old mice received anesthesia with 3% sevoflurane 2 h daily for 3 days. The mice were sacrificed 1 h after anesthesia, and their hippocampi were harvested. The effects of repeated sevoflurane exposure on SIRT1 and BDNF levels were determined at the mRNA and protein levels. As shown in Figures 2(a) and 2(b), although there was no difference in the expression level of SIRT1 mRNA, BDNF mRNA expression decreased after repeated sevoflurane exposure (P < 0.01). At the protein level, both SIRT1 and BDNF expressions were suppressed (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Figures 2(c)–2(e)).

Figure 2.

Effect of sevoflurane exposure on the expression of SIRT1 and BDNF in vivo and in vitro. (a, b) RT-PCR analysis of SIRT1 and BDNF mRNA expression between the control group and the sevoflurane group in hippocampal tissue, respectively (n = 3 per group). (c) Representative western blot bands of SIRT1 and BDNF in the neonatal mouse hippocampus (n = 4 per group). (d, e) Densitometry quantification of SIRT1 and BDNF expression ex vivo, respectively. (f) Representative western blot bands of SIRT1 and BDNF in primary hippocampal neurons (n = 4 per group). (g, h) Densitometry quantification of SIRT1 and BDNF expression in vitro, respectively. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

In the in vitro experiment, the neurons were treated with 4.1% sevoflurane for 6 h on the seventh day of culture. The neurons were lysed to detect SIRT1 and BDNF protein levels by western blotting. As shown in Figures 2(f)–2(h), the sevoflurane anesthesia reduced the protein level of SIRT1 and BDNF protein as compared to the control conditions (P < 0.01).

3.2. MeCP2 and CREB Expression Changed after Sevoflurane Exposure Ex Vivo and In Vitro

In hippocampus of young mice, the expression of AcMeCP2 as well as that of total MeCP2 was increased (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(a)–3(c)) after sevoflurane exposure. There was no significant difference in terms of total CREB expression in hippocampal tissues between the sevoflurane anesthesia and control conditions, while the level of phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) was declined after repeated sevoflurane exposure (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(a), 3(d), and 3(e)).

Figure 3.

Alterations in MeCP2 and CREB expression. (a) Representative western blot bands of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB in the developing mouse hippocampus. (b–e) Densitometry quantification of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB expression ex vivo, respectively. (f) Representative western blot bands of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB in primary hippocampal neurons. (g–j) Densitometry quantification of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB expression in vitro, respectively. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). ∗P < 0.05.

The quantification of the western blotting results also showed that there was a significant interaction among MeCP2, CREB expression, and sevoflurane exposure in primary neurons. By comparison with the control condition, the sevoflurane anesthesia group displayed significantly elevated levels of AcMeCP2 and total MeCP2 (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(f)–3(h)). In line with in vivo experiment, sevoflurane exposure also significantly reduced levels of phosphorylated CREB (P < 0.05) without the change of total CREB expression (Figures 3(f), 3(i), and 3(j)).

3.3. Resveratrol Prevented Sevoflurane-Induced Decreases in SIRT1 and BDNF Expression Ex Vivo and In Vitro

Evidence has shown that resveratrol, a potent SIRT1 activator, is a powerful neuroprotective agent and may play a role in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases [48]. Based on previous studies [37, 38, 49], three concentrations of resveratrol (50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 150 mg/kg) were used, and the minimum effective concentration was determined for subsequent experiments. Mice were pretreated with resveratrol via intraperitoneal injection daily from P3 to P6 and 1 h before sevoflurane exposure on P6, P7, and P8. As shown in Figure 4(a), SIRT1 expression was upregulated dose-dependently in resveratrol-treated mice in comparison with that in mice that underwent sevoflurane exposure without resveratrol pretreatment. Although the injection of 50 mg/kg resveratrol did not significantly alter SIRT1 expression, 100 mg/kg and 150 mg/kg resveratrol injection increased SIRT1 expression compared with that in the sevoflurane group (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001). Thus, we chose 100 mg/kg resveratrol as the dose for the intervention experiment.

Figure 4.

Resveratrol prevented sevoflurane-induced decreases in SIRT1 and BDNF ex vivo and in vitro. (a) Neonatal mice were pretreated with 50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 150 mg/kg resveratrol from P3 to P8 and exposed to sevoflurane from P6 to P8. Western blotting was performed to determine the minimum effective dose of resveratrol. (b) Primary hippocampal neurons were pretreated with 10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM resveratrol 24 h before exposure to sevoflurane. Western blotting was used to determine the minimum effective concentration of resveratrol. (c, d) RT-PCR results showing SIRT1 and BDNF mRNA expression in the developing mouse hippocampus between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol), respectively. (e) Representative western blot bands of SIRT1 and BDNF in the developing mouse hippocampus between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol). (f) Representative western blot bands of SIRT1 and BDNF in hippocampal neurons between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol). (g, i) Densitometry quantification of SIRT1 and BDNF ex vivo, respectively. (h, j) Densitometry quantification of SIRT1 and BDNF protein expression in vitro, respectively. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

There was no difference in the expression of SIRT1 at the RNA level between mice pretreated with resveratrol or DMSO before sevoflurane exposure (Figure 4(c)). However, BDNF expression in mice pretreated with resveratrol was elevated when compared to mice pretreated with DMSO before sevoflurane exposure (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 22.41, P = 0.0015; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 7.015, P = 0.0293; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 6.531, P = 0.0339) (Figure 4(d)). At the protein level, sevoflurane decreased SIRT1 and BDNF expression in the mice pretreated with DMSO as compared to control conditions. However, in the mice pretreated with resveratrol, sevoflurane did not decrease the expression of SIRT1 (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 7.066, P = 0.0209; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 4.419, P = 0.0573; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 7.494, P = 0.018) and BDNF (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 16.41, P = 0.0016; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 13.59, P = 0.0031; Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.545, P = 0.0364) as compared to control conditions (Figures 4(e), 4(g), and 4(i)).

Based on previous studies [50–52], hippocampal neurons were treated with resveratrol for 24 h, and the optimal concentration of resveratrol was selected from10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM. As shown in Figure 3(b), exposure to low concentrations of resveratrol (10 μM) did not prevent sevoflurane-induced SIRT1 suppression. In comparison, exposure to high concentrations of resveratrol (20 μM and 40 μM) for 24 h effectively increased SIRT1 expression (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001). Therefore, intervention group neurons were treated with 20 μM resveratrol for 24 h before sevoflurane anesthesia. In keeping with ex vivo experiment, sevoflurane reduced SIRT1 and BDNF levels as compared to the control conditions, and resveratrol blocked the sevoflurane-induced changes in SIRT1 and BDNF levels (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 12.76, P = 0.0038; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 9.084, P = 0.0108; Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 6.665, P = 0.024; Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 8.63, P = 0.0124; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 7.61, P = 0.0173; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.17, P = 0.0422, respectively) (Figures 4(f), 4(h), and 4(j)).

3.4. Resveratrol Reversed the Expression Change of MeCP2 and CREB Induced by Sevoflurane Exposure Ex Vivo and In Vitro

Previous studies have indicated that SIRT1 could interact with AcMeCP2 and CREB [33, 53]. This finding was also confirmed by our Co-IP results (Figure 5(a)). In the ex vivo experiment, resveratrol reversed sevoflurane-induced changes in the expression of MeCP2 and CREB. Notably, following resveratrol administration, AcMeCP2 (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 4.771, P = 0.0495; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 7.552, P = 0.0177; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 6.603, P = 0.0246) and total MeCP2 (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 13.08, P = 0.0035; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 8.213, P = 0.0142; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 7.521, P = 0.0179) levels decreased, whereas the p-CREB (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 5.889, P = 0.0319; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 5.787, P = 0.0332; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 9.886, P = 0.0085) level increased (Figures 5(b), 5(d), and 5(f)). In contrast, the CREB level was not affected by resveratrol administration (Figures 5(b), 5(h), and 5(j)).

Figure 5.

Resveratrol reversed the change in the expression of MeCP2 and CREB induced by sevoflurane exposure ex vivo and in vitro. (a) Co-IP results for SIRT1, AcMeCP2, and CREB. (b) Representative western blot bands of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB in the developing mouse hippocampus between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol). (c) Representative western blot bands of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB in primary hippocampal neurons between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol). (d, f, h) Densitometry quantification of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB expression ex vivo, respectively. (e, g, i) Densitometry quantification of AcMeCP2, total MeCP2, p-CREB, and total CREB expression in vitro, respectively. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Consistently, neurons pretreated with 20 μM resveratrol before sevoflurane exposure also showed decreased expression of AcMeCP2 (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 5.048, P = 0.0442; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 4.903, P = 0.0469; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 10.24, P = 0.0076) and total MeCP2 (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 13.08, P = 0.0035; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 8.213, P = 0.0142; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 6.686, P = 0.0238) but increased expression of p-CREB (Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 7.038, P = 0.0211; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 14.32, P = 0.0026; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 9.537, P = 0.0094) by comparison with that in the DMSO pretreated group (Figures 5(c), 5(e), and 5(g)). The expression of CREB did not change with the use of resveratrol (Figures 5(c), 5(i), and 5(k)).

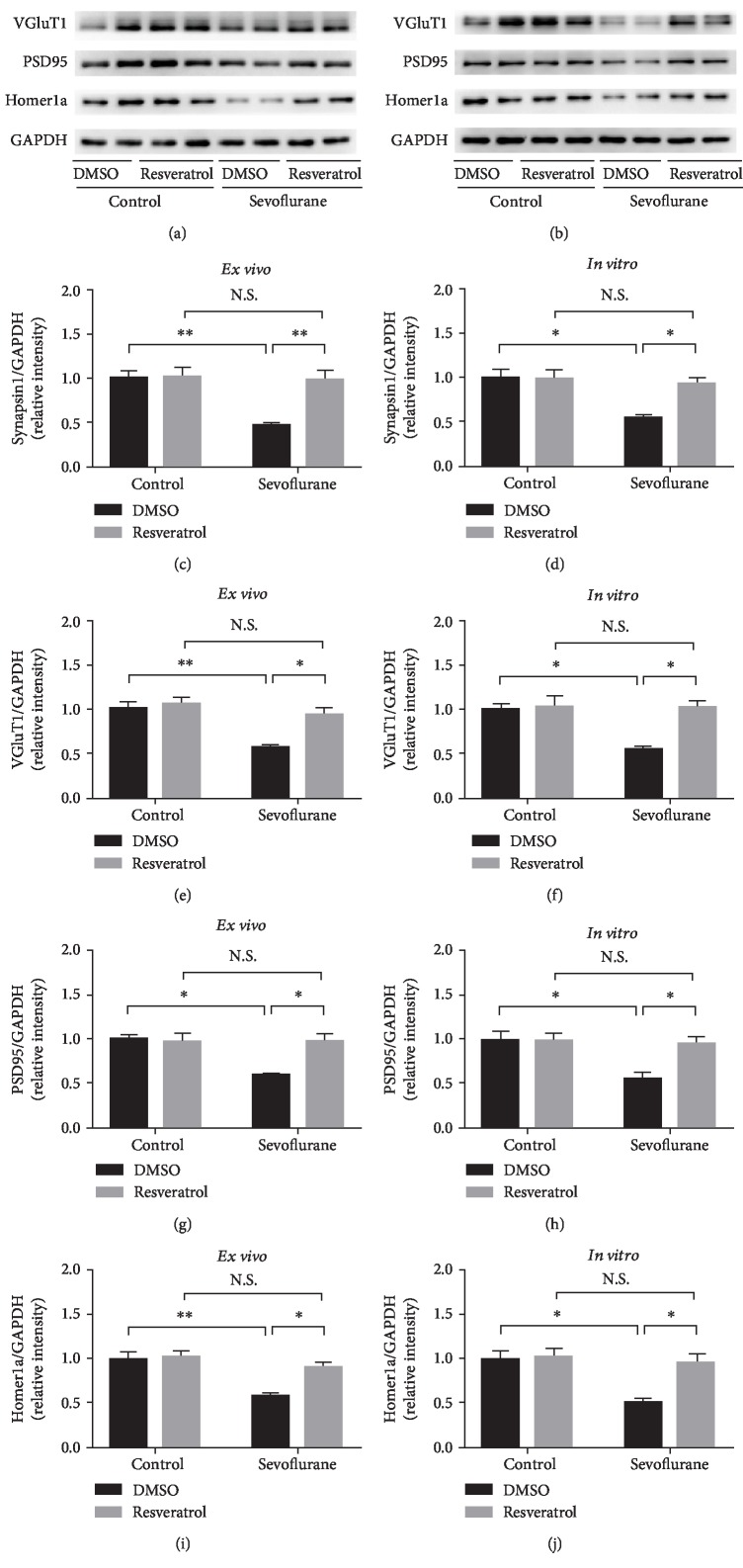

3.5. Resveratrol Restored Synaptic Protein Expression Ex Vivo and In Vitro

Synaptic efficacy depends on the presynaptic and postsynaptic compartments. In particular, synapsin1, vesicular glutamate transporters (VGluT1), PSD95, and Homer1a are classical markers of presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins, which play an important role in synaptic activity [54–59]. Previous research has reported that the repeated sevoflurane exposure downregulates synaptic proteins such as postsynaptic protein PSD95 in the hippocampus of developing mice [60, 61]. In the present study, we detect the effect of sevoflurane and resveratrol on the expression of these proteins. Our results indicated that repeated sevoflurane exposure induced a marked decrease in the hippocampal protein levels of synapsin1, VGluT1, PSD95, and Homer1a. However, these downregulations of synaptic proteins were reversed in the presence of resveratrol treatment (synapsin1: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 12.19, P = 0.0045; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 11.01, P = 0.0061; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 9.139, P = 0.0106; VGluT1: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 15.39, P = 0.0020; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 9.535, P = 0.0094; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.172, P = 0.0421; PSD95: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 6.935, P = 0.0218; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 5.654, P = 0.0349; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 6.887, P = 0.0222; and Homer1a: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 16.89, P = 0.0014; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 8.179, P = 0.0144; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.577, P = 0.0359) (Figures 6(a), 6(c), 6(e), 6(g), and 6(i)).

Figure 6.

Resveratrol restored synaptic protein expression ex vivo and in vitro. (a) Representative western blot bands of synapsin1, VGluT1, PSD95, and Homer1a protein in the developing mouse hippocampus between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol). (b) Representative western blot bands of synapsin1, VGluT1, PSD95, and Homer1a protein in primary hippocampal neurons between groups (control group vs. sevoflurane group) and treatments (DMSO or resveratrol). (c, e, g, i) Densitometry quantification of synapsin1, VGluT1, PSD95, and Homer1a in vivo, respectively. (d, f, h, j) Densitometry quantification of synapsin1, VGluT1, PSD95, and Homer1a in vitro, respectively. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Consistently, long-term sevoflurane exposure in primary neurons also led to a significant decrease in the protein levels of presynaptic proteins (synapsin1 and VGluT1), along with the downregulation of postsynaptic proteins (PSD95 and Homer1a) in the PSD fraction. However, these changes in synaptic proteins induced by sevoflurane were significantly attenuated by pretreatment with resveratrol (synapsin1: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 8.505, P = 0.0129; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 4.853, P = 0.0479; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.719, P = 0.034; VGluT1: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 7.698, P = 0.0168; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 9.36, P = 0.0099; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 6.711, P = 0.0236; PSD95: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 7.643, P = 0.0171; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 5.108, P = 0.0432; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.5851, P = 0.0359; and Homer1a: Fsevoflurane (1, 12) = 9.21, P = 0.0104; Fresveratrol (1, 12) = 7.464, P = 0.0182; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 12) = 5.892, P = 0.0319) (Figures 6(b), 6(d), 6(f), and 6(j)).

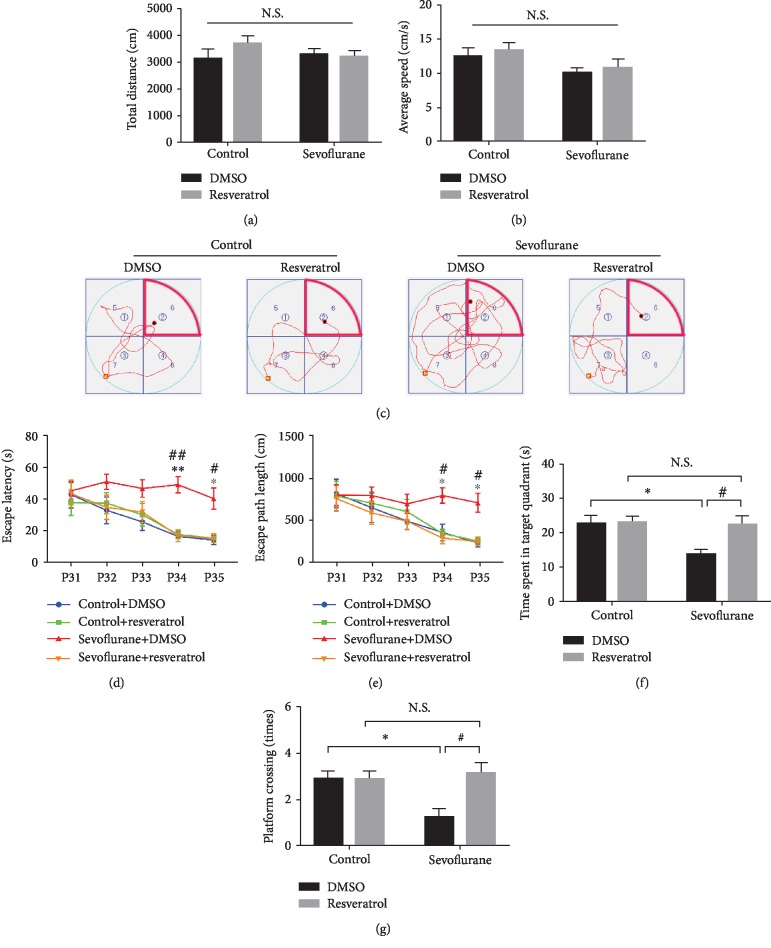

3.6. Spatial Memory Deficits Induced by Early Repeated Exposure to Sevoflurane Were Alleviated by Treatment with Resveratrol

To determine the long-term cognitive effects of repeated isoflurane exposure and resveratrol treatment, the MWM test was used to detect the spatial memory of the different groups of mice on P31. Before the MWM test, the motor function of young mice was measured by the open field test. As displayed in Figures 7(a) and 7(b), the total distance traveled and average speed did not differ among the four groups of mice. In the MWM test, all groups of mice learned to locate a hidden platform, as evidenced by the decreasing escape latencies (Ftime (4, 112) = 9.702, P < 0.001) and escape path length (Ftime (4, 112) = 9.503, P < 0.001) over the training period, and the difference was observed between the groups during the same day (Ftreatment (3, 28) = 9.693, P < 0.001; Ftreatment (3, 28) = 4.877, P < 0.01) (Figure 6(c)). A post hoc test (Bonferroni) showed that, compared with control mice, the mice exposed to sevoflurane required longer escape latency and escape path length to locate the position of the platform in the MWM pool on P34 (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively) and P35 (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, respectively) (Figures 7(d) and 7(e)). The mice that were exposed to sevoflurane, compared to control mice, also spent less time in the target quadrant (Fsevoflurane (1, 28) = 5.455, P = 0.0269; Fresveratrol (1, 28) = 4.97, P = 0.034; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 28) = 4.428, P = 0.0445) (Figure 7(f)) and crossed the platform fewer times (P < 0.05) (Figure 7(g)).

Figure 7.

Motor function and spatial memory changes induced by sevoflurane exposure and pretreatment with resveratrol. (a) Total distance traveled by four groups of mice in the open field test. (b) The average speed traveled by four groups of mice in the open field test. (c) Representative swimming paths of the mice in the four experimental groups obtained from the training in quadrant 7 on P34. The mice were placed in the water facing the pool wall at the yellow point in quadrant 7 on the fourth day of training; the swimming path of mice was finished at the black point. Quadrant 6 is the target quadrant (marked by red lines), and platform ② is the target platform. (d) The escape latency in the MWM plotted against the training days. (e) The escape path length in the MWM plotted against the training days. (f) Analysis of the time spent in each quadrant during the probe trial of the MWM. (g) The platform crossing times during the probe trial of the MWM test. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 8 per group). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, control+DMSO vs. sevoflurane+DMSO; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, sevoflurane+resveratrol vs. sevoflurane+DMSO.

On the other hand, the Bonferroni post hoc test showed that, compared with sevoflurane mice, the mice pretreated with resveratrol before sevoflurane required shorter escape latency and escape path length to locate the position of the platform in the MWM pool on P34 (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) and P35 (P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively), longer time in the target quadrant (Fsevoflurane (1, 28) = 5.455, P = 0.0269; Fresveratrol (1, 28) = 4.97, P = 0.034; and Fsevoflurane∗resveratrol (1, 28) = 4.428, P = 0.0445) and crossed the platform more times (P < 0.05) (Figures 7(c)–7(g)).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we found that SIRT1 deficiency was associated with prolonged cognitive impairment in developing mice following repeated sevoflurane exposure. Sevoflurane-induced SIRT1 inhibition led to the inactivation of MeCP2 and CREB, two critical epigenetic regulators of BDNF, and then reduced the expression of BDNF in the hippocampus. Pretreatment with resveratrol, an agonist of SIRT1, almost restored the expression of SIRT1, increased the epigenetic regulation of MeCP2 and CREB, promoted the expression of BDNF, and consequently mitigated the cognitive deficits. Collectively, our findings showed that SIRT1 deficiency modulated BDNF signaling by influencing the epigenetic activity of MeCP2 and CREB and suggested a promising method for mitigating the neurotoxicity induced by sevoflurane in developing mice.

BDNF has been shown to regulate the survival and the differentiation of neurons and dynamically modulate the synaptic plasticity in the developing brain [23, 24, 34]. BDNF deficiency in the CA1 of the hippocampus led to impaired long-term potentiation and synaptic structure, and administration of recombinant BDNF almost reversed these pathological effects [23, 62]. Several lines of evidence indicated that impaired BDNF signaling was associated with increased neuroapoptosis and disrupted synaptic components in the neonatal rodent following exposure to commonly used GAs [27–29, 62]. In agreement with the aforementioned findings, our data showed that sevoflurane downregulated BDNF in the hippocampi of neonatal mice. BDNF played an important role in synaptic plasticity, partially owing to the regulation of the local synthesis of proteins, including the presynaptic and postsynaptic molecules [24, 63]. As expected, we found that sevoflurane-induced BDNF reduction resulted in decreased levels of the presynaptic components (synapsin1 and VGluT1) and the postsynaptic component (PSD95). Surprisingly, we also found that Homer1a, a key neuroprotective endogenous molecule, was downregulated by sevoflurane. As is known, Homer1a belongs to the postsynaptic density family [64], but it is unknown whether the change of Homer1a is related to the decrease of BDNF in the present study. In addition, the present and previous studies demonstrated that upregulated expression of BDNF mitigated GA-induced neurotoxicity in the developing brain [30, 65]. As is known, BDNF can be produced in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia in the brain. Previous studies showed that neonatal exposure to isoflurane induced BDNF reduction in astrocytes and then promoted neuronal loss [66–68]. In our animal models, we only measured the gross effect of sevoflurane on the expression of BDNF in the developing brain, so we could not find the precise resource of BDNF. Taking into account the experiment of cultured neurons, we cautiously indicated that sevoflurane exposure reduced the expression of BDNF in developing neurons. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that sevoflurane may change the production of BDNF from astrocytes or microglia. These direct and indirect evidences support the notion that the inhibition of neuronal BDNF signaling contributes to the sustained neurobehavioral abnormality in experimental models with repeated exposure to GAs.

The biosynthesis of BDNF can be modulated at different levels. Recently, increasing attention has been paid to the epigenetic reprogramming of BDNF because this regulation mechanism takes part in activity-dependent synaptic function and the crosstalk of neuronal circuits [69, 70]. As aforementioned, GAs inhibited the expression of BDNF when administered at the peak of brain development, and an increasing number of studies had been conducted to explore the mechanism by which GAs regulated the expression of BDNF [1, 30, 71]. In light of the widespread use of sevoflurane in current pediatric anesthesia, we attempted to explore how sevoflurane influenced the expression of BDNF in the developing brain in the present study. We found that the level of acetylated MeCP2 is increased and the level of phosphorylated CREB is decreased in the hippocampi of developing mice following repeated exposure to sevoflurane. As is known, MeCP2 and CREB are two key transcriptional factors that regulate the expression of BDNF in the central nervous system [70]. Their abnormal activity led to BDNF reduction and then impaired the biosynthesis of synaptic proteins [69, 72] in our study. Furthermore, we found that resveratrol, an agonist of SIRT1, almost normalized the sevoflurane-induced changes of MeCP2 and CREB in the hippocampus. Indeed, we found that SIRT1 was inhibited by isoflurane, another inhalational anesthetics, in neonatal rats in our previous study [73]. Therefore, we examined the effect of sevoflurane on the expression of SIRT1 in the hippocampus and did confirm that SIRT1 was reduced by sevoflurane in the current study. It was reported that SIRT1 has been strongly implicated in normal synaptic plasticity and cognitive function [32, 53] by regulating the level of acetylated MeCP2 and the transcriptional activity of CREB in the brain [33, 34]. However, it is unclear whether sevoflurane-induced SIRT1 inhibition modulates the expression of BDNF by inhibiting the activity of MeCP2 and CREB. Together, these findings suggest that SIRT1 reduction and inhibited activity of MeCP2 and CREB are related to sevoflurane-induced decreased BDNF in the developing hippocampus.

SIRT1, a NAD-dependent class III histone deacetylase (HDAC), is involved in various physiological and pathophysiological processes, including neurodevelopment, aging, metabolism, inflammation, and cancer [35]. Its substrates include histone proteins as well as nonhistone proteins [74]. In the present study, we hypothesized that there was a link between the SIRT1 inhibition and abnormal activity of MeCP2 and CREB in developing mice following sevoflurane exposure. To test this hypothesis, we pretreated the neonatal mice with resveratrol before sevoflurane anesthesia. We found that resveratrol pretreatment rescued SIRT1 inhibition, reduced the level of acetylated MeCP2, and increased the levels of phosphorylated CREB and BDNF in the hippocampal tissue and in cultured hippocampal neurons. Furthermore, our coimmunoprecipitation experiment confirmed that SIRT1 could directly bind to MeCP2 or CREB, respectively. CREB-binding protein (CBP) was reduced by sevoflurane in neonatal rats [65]. Similar findings were observed in another study in which general anesthesia (midazolam-nitrous oxide-isoflurane) for 6 hours resulted in CBP reduction in neonatal rats at 24 hours after the treatment ended [71]. In the present study, we found that CBP was not likely correlated with the expression of SIRT1; therefore, the data of CBP was not present. In previous neurodegenerative models, SIRT1 was involved in the regulation of miR134 and transducers of regulated CREB1 (TORC1) and influenced the expression of BDNF [33, 34]. We found that SIRT1 was involved in the regulation of the level of phosphorylated CREB but did not further investigate the potential mechanism by which SIRT1 mediated changes in the transcriptional activity of CREB to affect the expression of BDNF, which is a limitation of our study.

Given the indispensable role of BDNF in GA-induced developmental neurotoxicity, it is essential to explore feasible therapeutic methods for rescuing the expression of BDNF. Several studies found that the increased expression of some class I and class II HADCs was involved in suppressing the expression of BDNF triggered by GA exposure during early life [30, 65, 71, 75, 76]. Theoretically, inhibitors of HDACs might be useful. Strikingly, this hypothesis was supported by a recent study showing that MS-275, a selective inhibitor of class I histone deacetylases (HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8) [77], and sodium butyrate restore GA-induced synaptic alterations along with BDNF alterations [65, 71]. However, it has been reported that inhibitors of class I HDACs have intrinsic toxic side effects and that there is thus a small therapeutic window, which prevents their application in the clinical setting [78]. In the present study, we found that resveratrol pretreatment almost restored the expression of SIRT1 and increased the expression of BDNF by influencing the transcriptional factors MeCP2 and CREB. Resveratrol (3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene (C14H12O3)) is a natural polyphenolic nutraceutical that has pleiotropic properties, including antioxidation, anti-inflammation, antiapoptosis, and anticancer properties in multiple organs under a wide variety of pathological conditions [79]. It has been reported that supplementation with resveratrol improves memory performance in association with increased hippocampal function connectivity in elderly adults [80]. Besides being known as an agonist of SIRT1, resveratrol also acts as an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [81, 82]. Amounts of studies implied that resveratrol could influence autophagy, oxidative stress, and inflammation through the mTOR pathway [49, 82–84]. Additionally, the mTOR pathway was found to take part in the regulation of dendritic growth, synapse formation, and synaptic protein expression [85–87]. It was reported that general anesthetics, including sevoflurane, induced developmental neuronal injury by activating the mTOR pathway [87–90]. In light of the fact that mTOR and BDNF interact in a complicated way in physiological or pathological settings [91, 92], we did not explore the crosstalk between BDNF and mTOR signaling in the sevoflurane-induced injury in the present study. Therefore, it needs to be further investigated whether mTOR signaling is involved in the protection of resveratrol against sevoflurane-induced impairment.

To our knowledge, we have provided the first evidence that resveratrol pretreatment mitigates sevoflurane-induced developmental neurodegeneration and improves long-term cognitive function. Although the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of resveratrol have been documented in more than 200 clinical trials, there is not yet any trial on its potential to prevent GA-induced neurotoxicity. We hypothesize that resveratrol might be a promising medication for preventing the noxious effect of GA in the developing brain. Although the clinical use of resveratrol is documented in stroke and other neurodegenerative diseases, its poor bioavailability and rapid metabolism may limit its use [93, 94]. Therefore, longer-acting SIRT1 agonists more readily absorbed will be more clinically relevant.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our study suggested that SIRT1 reduction was associated with sevoflurane-induced neurotoxicity. SIRT1 deficiency increases MeCP2 acetylation and decreases CREB phosphorylation, thus resulting in the downregulation of BDNF in the hippocampus of the developing brain. Also, pretreatment with resveratrol mitigates the sevoflurane-induced changes of SIRT1, MeCP2, and CREB in the hippocampus and improves the prolonged neurobehavioral performance in the developing model. Our findings proposed a new mechanism of sevoflurane-induced neurotoxicity in the developing brain and suggested that these long-term cognitive deficits could be mitigated by activating SIRT1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by project grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 81400882, 81771159, 81571047, and 81500982) and Science Foundation Projects for Young Scientists of Hubei (grant No. 2017CFB171).

Contributor Information

Ailin Luo, Email: alluo@hust.edu.cn.

Shiyong Li, Email: shiyongli@hust.edu.cn.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: study population. Supplementary Figure 1: the rooms and apparatus used in the MWM test and the division of quadrants and platforms. (A) The rooms and apparatus used in the MWM test. The MWM test was conducted in two separate rooms: test room and computer room. In the test room, there was a round and steel pool, which was filled up with water. Four graphic signals were hung on the walls as visual cues for the navigation of mice in the MWM. Swimming activity of each mouse was tracked via a camera mounted overhead and was analysed by AVTAS v3.3, an automated video-tracking system. The data was recorded automatically in a computer, which contains this system and was put in the computer room. (B) The background of the swimming path recorded by the video-tracking system. By adding powdered milk, the water was rendered opaque. A platform (diametric distance, 10 cm) was placed in the target quadrant and was 1.0 cm lower than the water level. (C) The quadrants and platforms divided automatically by the video-tracking system. Four platforms (platforms ①, ②, ③, and ④) and four quadrants (quadrants 5, 6, 7, and 8) were generated automatically, and platform ② and quadrant 6 were defined as the target platform (marked by a black circle) and target quadrant (marked by red line), respectively. (D) The recorded swimming path shown in the manuscript without background. The target quadrant was marked by a red line.

References

- 1.Lu L. X., Yon J. H., Carter L. B., Jevtovic-Todorovic V. General anesthesia activates BDNF-dependent neuroapoptosis in the developing rat brain. Apoptosis. 2006;11(9):1603–1615. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-8762-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jevtovic-Todorovic V., Hartman R. E., Izumi Y., et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(3):876–882. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikonomidou C., Bosch F., Miksa M., et al. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999;283(5398):70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brambrink A. M., Evers A. S., Avidan M. S., et al. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(4):834–841. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d049cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creeley C. E., Dikranian K. T., Dissen G. A., Back S. A., Olney J. W., Brambrink A. M. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of neurons and oligodendrocytes in the fetal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(3):626–638. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brambrink A. M., Back S. A., Riddle A., et al. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of oligodendrocytes in the neonatal primate brain. Annals of Neurology. 2012;72(4):525–535. doi: 10.1002/ana.23652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raper J., De Biasio J. C., Murphy K. L., Alvarado M. C., Baxter M. G. Persistent alteration in behavioural reactivity to a mild social stressor in rhesus monkeys repeatedly exposed to sevoflurane in infancy. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018;120(4):761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slikker W., Zou X., Hotchkiss C. E., et al. Ketamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkey. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;98(1):145–158. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creeley C., Dikranian K., Dissen G., Martin L., Olney J., Brambrink A. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2013;110(Supplement 1):i29–i38. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vutskits L., Xie Z. Lasting impact of general anaesthesia on the brain: mechanisms and relevance. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2016;17(11):705–717. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson A. J. Neurotoxicity and the need for anesthesia in the newborn: does the emperor have no clothes? Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):507–509. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182475673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson A. J., Sun L. S. Clinical evidence for any effect of anesthesia on the developing brain. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(4):840–853. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazoit J. X., Roulleau P., Baujard C. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain: isoflurane or ischemia-reperfusion? Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1245–1246. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f710a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders R. D., Andropoulos D., Ma D., Maze M. Theseus, the labyrinth, and the minotaur of anaesthetic-induced developmental neurotoxicity. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;119(3):453–455. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vutskits L., Sall J. W. Reproducibility of science and developmental anaesthesia neurotoxicity: a tale of two cities. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;119(3):451–452. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun L. S., Li G., Miller T. L., et al. Association between a single general anesthesia exposure before age 36 months and neurocognitive outcomes in later childhood. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2312–2320. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glatz P., Sandin R. H., Pedersen N. L., Bonamy A. K., Eriksson L. I., Granath F. Association of anesthesia and surgery during childhood with long-term academic performance. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171(1, article e163470) doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Leary J. D., Janus M., Duku E., et al. Influence of surgical procedures and general anesthesia on child development before primary school entry among matched sibling pairs. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019;173(1):29–36. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson A. J., Disma N., de Graaff J. C., et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;387(10015):239–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00608-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCann M. E., de Graaff J. C., Dorris L., et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age after general anaesthesia or awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled equivalence trial. The Lancet. 2019;393(10172):664–677. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32485-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner D. O., Zaccariello M. J., Katusic S. K., et al. Neuropsychological and behavioral outcomes after exposure of young children to procedures requiring general anesthesia: the Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) study. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(1):89–105. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaccariello M. J., Frank R. D., Lee M., et al. Patterns of neuropsychological changes after general anaesthesia in young children: secondary analysis of the Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids study. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019;122(5):671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson S. L., Abel T., Deuel T. A., Martin K. C., Rose J. C., Kandel E. R. Recombinant BDNF rescues deficits in basal synaptic transmission and hippocampal LTP in BDNF knockout mice. Neuron. 1996;16(6):1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos A. R., Comprido D., Duarte C. B. Regulation of local translation at the synapse by BDNF. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010;92(4):505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duman R. S. Synaptic plasticity and mood disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7(Supplement 1):S29–S34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bekinschtein P., Cammarota M., Izquierdo I., Medina J. H. Reviews: BDNF and memory formation and storage. The Neuroscientist. 2008;14(2):147–156. doi: 10.1177/1073858407305850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Head B. P., Patel H. H., Niesman I. R., Drummond J. C., Roth D. M., Patel P. M. Inhibition of p75 neurotrophin receptor attenuates isoflurane-mediated neuronal apoptosis in the neonatal central nervous system. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(4):813–825. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b602b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemkuil B. P., Head B. P., Pearn M. L., Patel H. H., Drummond J. C., Patel P. M. Isoflurane neurotoxicity is mediated by p75NTR-RhoA activation and actin depolymerization. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(1):49–57. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318201dcb3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearn M. L., Hu Y., Niesman I. R., et al. Propofol neurotoxicity is mediated by p75 neurotrophin receptor activation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):352–361. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242a48c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu J., Bie B., Naguib M. Epigenetic manipulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor improves memory deficiency induced by neonatal anesthesia in rats. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(3):624–640. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michan S., Li Y., Chou M. M.-H., et al. SIRT1 is essential for normal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(29):9695–9707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0027-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao J., Wang W. Y., Mao Y. W., et al. A novel pathway regulates memory and plasticity via SIRT1 and miR-134. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature09271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong H., Cohen D. E., Cui L., et al. Sirt1 mediates neuroprotection from mutant huntingtin by activation of the TORC1 and CREB transcriptional pathway. Nature Medicine. 2012;18(1):159–165. doi: 10.1038/nm.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang M., Wang J., Fu J., et al. Neuroprotective role of Sirt1 in mammalian models of Huntington's disease through activation of multiple Sirt1 targets. Nature Medicine. 2012;18(1):153–158. doi: 10.1038/nm.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herskovits A. Z., Guarente L. SIRT1 in neurodevelopment and brain senescence. Neuron. 2014;81(3):471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomes B. A. Q., Silva J. P. B., Romeiro C. F. R., et al. Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Resveratrol in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of SIRT1. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2018;2018:15. doi: 10.1155/2018/8152373.8152373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B., Ge S., Xiong W., Xue Z. Effects of resveratrol pretreatment on endoplasmic reticulum stress and cognitive function after surgery in aged mice. BMC Anesthesiology. 2018;18(1):p. 141. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0606-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X. M., Zhou M. T., Wang X. M., Ji M. H., Zhou Z. Q., Yang J. J. Resveratrol pretreatment attenuates the isoflurane-induced cognitive impairment through its anti-inflammation and -apoptosis actions in aged mice. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2014;52(2):286–293. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu W., Yang E., Ye J., Han W., Du Z. L. Resveratrol protects neuronal cells from isoflurane-induced inflammation and oxidative stress-associated death by attenuating apoptosis via Akt/p38 MAPK signaling. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2018;15(2):1568–1573. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen X., Dong Y., Xu Z., et al. Selective anesthesia-induced neuroinflammation in developing mouse brain and cognitive impairment. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(3):502–515. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182834d77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X., Dong Y., Zhang Y., Li T., Xie Z. Sevoflurane induces cognitive impairment in young mice via autophagy. PLoS One. 2019;14(5, article e0216372) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao G., Zhang J., Zhang L., et al. Sevoflurane induces tau phosphorylation and glycogen synthase kinase 3β activation in young mice. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(3):510–527. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J., Dong Y., Zhou C., Zhang Y., Xie Z. Anesthetic sevoflurane reduces levels of hippocalcin and postsynaptic density protein 95. Molecular Neurobiology. 2015;51(3):853–863. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narasimhan K. K. S., Jayakumar D., Velusamy P., et al. Morinda citrifolia and its active principle scopoletin mitigate protein aggregation and neuronal apoptosis through augmenting the DJ-1/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2019;2019:13. doi: 10.1155/2019/2761041.2761041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X., Xin X., Dong Y., et al. Surgical incision-induced nociception causes cognitive impairment and reduction in synaptic NMDA receptor 2B in mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(45):17737–17748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2049-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terry A. V., Jr. Spatial navigation (water maze) tasks. In: Buccafusco J. J., editor. Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience. 2nd. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2009. pp. 267–280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng X., Liang N., Zhu D., et al. Resveratrol inhibits β-Amyloid-Induced neuronal apoptosis through regulation of SIRT1-ROCK1 signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8(3, article e59888) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peñalver P., Belmonte-Reche E., Adán N., et al. Alkylated resveratrol prodrugs and metabolites as potential therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2018;146:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou Y., Wang K., Wan W., Cheng Y., Pu X., Ye X. Resveratrol provides neuroprotection by regulating the JAK2/STAT3/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway after stroke in rats. Genes & Diseases. 2018;5(3):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lv W., Zhang J., Jiao A., Wang B., Chen B., Lin J. Resveratrol attenuates hIAPP amyloid formation and restores the insulin secretion ability in hIAPP-INS1 cell line via enhancing autophagy. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2019;97(2):82–89. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2016-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Q., Ganapathy S., Singh K. P., Shankar S., Srivastava R. K. Resveratrol induces growth arrest and apoptosis through activation of FOXO transcription factors in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(12, article e15288) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao J., Wang X., Wu Y., et al. Synergistic effect of resveratrol and HSV-TK/GCV therapy on murine hepatoma cells. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2019;20(2):183–191. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2018.1523094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zocchi L., Sassone-Corsi P. SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of MeCP2 contributes to BDNF expression. Epigenetics. 2012;7(7):695–700. doi: 10.4161/epi.20733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clifton N. E., Cameron D., Trent S., Sykes L. H., Thomas K. L., Hall J. Hippocampal regulation of postsynaptic density Homer1 by associative learning. Neural Plasticity. 2017;2017:11. doi: 10.1155/2017/5959182.5959182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ehrlich I., Malinow R. Postsynaptic density 95 controls AMPA receptor incorporation during long-term potentiation and experience-driven synaptic plasticity. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(4):916–927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4733-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beique J. C., Andrade R. PSD-95 regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity in rat cerebral cortex. The Journal of Physiology. 2003;546(3):859–867. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han K., Kim E. Synaptic adhesion molecules and PSD-95. Progress in Neurobiology. 2008;84(3):263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fourneau J., Canu M. H., Cieniewski-Bernard C., Bastide B., Dupont E. Synaptic protein changes after a chronic period of sensorimotor perturbation in adult rats: a potential role of phosphorylation/O-GlcNAcylation interplay. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2018;147(2):240–255. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martineau M., Guzman R. E., Fahlke C., Klingauf J. VGLUT1 functions as a glutamate/proton exchanger with chloride channel activity in hippocampal glutamatergic synapses. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):p. 2279. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zimering J. H., Dong Y., Fang F., Huang L., Zhang Y., Xie Z. Anesthetic sevoflurane causes rho-dependent filopodial shortening in mouse neurons. PLoS One. 2016;11(7, article e0159637) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu H., Liufu N., Dong Y., et al. Sevoflurane acts on ubiquitination–proteasome pathway to reduce postsynaptic density 95 protein levels in young mice. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(6):961–975. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korte M., Griesbeck O., Gravel C., et al. Virus-mediated gene transfer into hippocampal CA1 region restores long-term potentiation in brain-derived neurotrophic factor mutant mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(22):12547–12552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leal G., Comprido D., Duarte C. B. BDNF-induced local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Part C):639–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y., Rao W., Zhang C., et al. Scaffolding protein Homer1a protects against NMDA-induced neuronal injury. Cell Death & Disease. 2015;6(8, article e1843) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jia M., Liu W. X., Yang J. J., et al. Role of histone acetylation in long-term neurobehavioral effects of neonatal exposure to sevoflurane in rats. Neurobiology of Disease. 2016;91:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stary C. M., Sun X., Giffard R. G. Astrocytes protect against isoflurane neurotoxicity by buffering pro-brain–derived neurotrophic factor. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(4):810–819. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou C. H., Zhang Y. H., Xue F., et al. Isoflurane exposure regulates the cell viability and BDNF expression of astrocytes via upregulation of TREK‑1. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2017;16(5):7305–7314. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ryu Y. K., Khan S., Smith S. C., Mintz C. D. Isoflurane impairs the capacity of astrocytes to support neuronal development in a mouse dissociated coculture model. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2014;26(4):363–368. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen K.-W., Chen L. Epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene during development and diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(3):p. 571. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karpova N. N. Role of BDNF epigenetics in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Part C):709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dalla Massara L., Osuru H. P., Oklopcic A., et al. General anesthesia causes epigenetic histone modulation of c-Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, target genes important for neuronal development in the immature rat hippocampus. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(6):1311–1327. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.KhorshidAhmad T., Acosta C., Cortes C., Lakowski T. M., Gangadaran S., Namaka M. Transcriptional regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2): a novel mechanism for re-myelination and/or myelin repair involved in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53(2):1092–1107. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fang X., Han Q., Li S., Zhao Y., Luo A. Chikusetsu saponin IVa attenuates isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive deficits via SIRT1/ERK1/2 in developmental rats. American Journal of Translational Research. 2017;9(9):4288–4299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gomes A. R., Yong J. S., Kiew K. C., et al. Sirtuin1 (SIRT1) in the acetylation of downstream target proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2016;1436:169–188. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3667-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu Z., Zhao P. Epigenetic alterations in anesthesia-induced neurotoxicity in the developing brain. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018;9:p. 1024. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sen T., Sen N. Isoflurane-induced inactivation of CREB through histone deacetylase 4 is responsible for cognitive impairment in developing brain. Neurobiology of Disease. 2016;96:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Joksimovic S. M., Osuru H. P., Oklopcic A., Beenhakker M. P., Jevtovic-Todorovic V., Todorovic S. M. Histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat (MS-275) restores anesthesia-induced alteration of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the developing rat hippocampus. Molecular Neurobiology. 2018;55(1):222–228. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0735-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kalin J. H., Bergman J. A. Development and therapeutic implications of selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;56(16):6297–6313. doi: 10.1021/jm4001659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keylor M. H., Matsuura B. S., Stephenson C. R. Chemistry and biology of resveratrol-derived natural products. Chemical Reviews. 2015;115(17):8976–9027. doi: 10.1021/cr500689b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Witte A. V., Kerti L., Margulies D. S., Floel A. Effects of resveratrol on memory performance, hippocampal functional connectivity, and glucose metabolism in healthy older adults. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(23):7862–7870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0385-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alayev A., Berger S. M., Holz M. K. Resveratrol as a novel treatment for diseases with mTOR pathway hyperactivation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2015;1348(1):116–123. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Widlund A. L., Baur J. A., Vang O. mTOR: more targets of resveratrol? Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2013;15 doi: 10.1017/erm.2013.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu Y., Liu F. Targeting mTOR: evaluating the therapeutic potential of resveratrol for cancer treatment. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;13(7):1032–1038. doi: 10.2174/18715206113139990113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sanches-Silva A., Testai L., Nabavi S. F., et al. Therapeutic potential of polyphenols in cardiovascular diseases: regulation of mTOR signaling pathway. Pharmacological Research. 2020;152, article 104626 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu Q., Dai C. L., Zhang Y., et al. Intranasal insulin increases synaptic protein expression and prevents anesthesia-induced cognitive deficits through mTOR-eEF2 pathway. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2019;70(3):925–936. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arafa S. R., LaSarge C. L., Pun R. Y. K., Khademi S., Danzer S. C. Self-reinforcing effects of mTOR hyperactive neurons on dendritic growth. Experimental Neurology. 2019;311:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu J., Mathena R., Xu M., et al. Early developmental exposure to general anesthetic agents in primary neuron culture disrupts synapse formation via actions on the mTOR pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(8):p. 2183. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu J., Kang E., Mintz C. D. Anesthetics disrupt brain development via actions on the mTOR pathway. Communicative & Integrative Biology. 2018;11(2):1–4. doi: 10.1080/19420889.2018.1451719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kang E., Jiang D., Ryu Y. K., et al. Early postnatal exposure to isoflurane causes cognitive deficits and disrupts development of newborn hippocampal neurons via activation of the mTOR pathway. PLoS Biology. 2017;15(7, article e2001246) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tan H., Li C. L., Zhang L., Yang Z. J., Zhao X., Wang Y. W. Sevoflurane inhibits the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 in neonatal rat brain. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2015;8(9):14816–14826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abdel‐Maksoud M. S., El‐Gamal M. I., Benhalilou D. R., Ashraf S., Mohammed S. A., Oh C.‐. H. Mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin: recent pathological aspects and inhibitors. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2019;39(2):631–664. doi: 10.1002/med.21535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Takei N., Inamura N., Kawamura M., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent local activation of translation machinery and protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(44):9760–9769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh A. P., Singh R., Verma S. S., et al. Health benefits of resveratrol: evidence from clinical studies. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2019;39(5):1851–1891. doi: 10.1002/med.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Narayanan S. V., Dave K. R., Saul I., Perez-Pinzon M. A. Resveratrol preconditioning protects against cerebral ischemic injury via nuclear erythroid 2–related factor 2. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1626–1632. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: study population. Supplementary Figure 1: the rooms and apparatus used in the MWM test and the division of quadrants and platforms. (A) The rooms and apparatus used in the MWM test. The MWM test was conducted in two separate rooms: test room and computer room. In the test room, there was a round and steel pool, which was filled up with water. Four graphic signals were hung on the walls as visual cues for the navigation of mice in the MWM. Swimming activity of each mouse was tracked via a camera mounted overhead and was analysed by AVTAS v3.3, an automated video-tracking system. The data was recorded automatically in a computer, which contains this system and was put in the computer room. (B) The background of the swimming path recorded by the video-tracking system. By adding powdered milk, the water was rendered opaque. A platform (diametric distance, 10 cm) was placed in the target quadrant and was 1.0 cm lower than the water level. (C) The quadrants and platforms divided automatically by the video-tracking system. Four platforms (platforms ①, ②, ③, and ④) and four quadrants (quadrants 5, 6, 7, and 8) were generated automatically, and platform ② and quadrant 6 were defined as the target platform (marked by a black circle) and target quadrant (marked by red line), respectively. (D) The recorded swimming path shown in the manuscript without background. The target quadrant was marked by a red line.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.