Highlights

-

•

Telephone-delivered psychological therapy is clinically effective.

-

•

Concerns remain about the quality of therapeutic relationships established by phone.

-

•

This review assessed the evidence base to support or refute such concerns.

-

•

Telephone sessions are shorter, but no different in therapeutic relationship.

-

•

Perceptions of interaction in telephone therapy differ from empirical evidence.

Keywords: Psychological therapy, Telephone therapy, Therapeutic alliance, Interaction, Conversation analysis, Telehealth

Abstract

Background

Despite comparable clinical outcomes, therapists and patients express reservations about the delivery of psychological therapy by telephone. These concerns centre around the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the ability to exercise professional skill and judgement in the absence of visual cues. However, the empirical evidence base for such perceptions has not been clearly established.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review to establish what is known empirically about interactional differences between psychotherapeutic encounters conducted face-to-face vs. by telephone.

Results

The review identified 15 studies that used situated, comparative approaches to exploring interactional aspects of telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy. These studies revealed evidence of little difference between modes in terms of therapeutic alliance, disclosure, empathy, attentiveness or participation. However, telephone therapy sessions were significantly shorter than those conducted face-to-face.

Limitations

We identified only a small number of heterogeneous studies, many of which used non-randomised, opportunity samples and did not use validated measures to assess the constructs under investigation. Disparate therapeutic modalities were used across studies and samples included both clinically diagnosed and non-clinical populations.

Conclusions

Available evidence suggests a lack of support for the viewpoint that the telephone has a detrimental effect on interactional aspects of psychological therapy. The challenge for clinical practice is to translate this evidence into a change in practitioner and patient attitudes and behaviours. In order to do so, it is important to understand and address the breadth of factors that underpin ongoing ambivalence towards the telephone mode, which pose a barrier to wider implementation.

1. Introduction

Psychological therapy is an evidence-based treatment for depression and anxiety that is increasingly being offered through a variety of distance communication media. These various modes, sometimes referred to collectively as ‘telemental health’ or ‘telepsychology’ (e.g. American Psychological Association, 2013; Hilty et al., 2013; Langarizadeh et al., 2017), include telephone, videoconference, email, text message and web-based interventions, alongside the traditional face-to-face mode. This paper is concerned specifically with telephone-delivered psychological therapy. It presents the findings of a systematic review that examined what differences exist (if any) in therapeutic interactions and relationships, where therapy is delivered over the telephone as compared with face-to-face. The review was conducted in the context of a broader research programme which seeks to enhance the quality of psychological interventions delivered by telephone in primary mental health service settings1.

The telephone has a long history in counselling and crisis intervention (Coman et al., 2001; Lester, 1977; Lester et al., 2012) and is utilised in specific treatment modalities such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Haregu et al., 2015; Mohr et al, 2008), Dialectal Behaviour Therapy (Ben-Porath, 2015; Koons, 2011; Oliveira and Rizvi, 2018) and psychoanalysis (Bakalar, 2013; Leffert, 2003; Scharff, 2012). Telephone-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is also used to address a range of physical and co-morbid health conditions (e.g. Dobkin et al., 2011; Everitt et al., 2019; Mohr et al., 2000; Muller and Yardley, 2011).

In the United Kingdom, telephone-based psychological therapy for depression and anxiety forms part of clinical guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009, 2011) and one-fifth of publicly-funded adult primary care mental health provision is delivered via this mode (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014). Evidence from both trial and service settings suggests that telephone-delivered psychological therapy leads to symptom improvement for subthreshold depression, mild to moderate depression and anxiety, and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and that similar clinical outcomes can be achieved via the telephone as are obtained in face-to-face intervention (Castro et al., 2020; Coughtrey and Pistrang, 2016; Furukawa et al., 2012; Hammond et al., 2012; Leach and Christensen, 2006; Mohr et al., 2008, 2012; Turner et al., 2014).

However, despite comparable clinical outcomes and a growing adoption of telephone service models, qualitative research highlights concerns about this mode of delivery, particularly among psychological therapists. These reservations centre around the quality of therapeutic relationship that can be established over the telephone, and the ability to exercise professional skill and judgement in their interactions with patients in the absence of visual cues (e.g. Bee et al., 2016; Gellatly et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2013; Richards et al., 2006; Turner et al., 2018; Webb, 2014). These research findings are echoed in the broader practice and academic literature, where it is asserted that the absence of non-verbal information has an impact on communication and interaction between patient and therapist, with consequences for understanding, empathy and alliance (e.g. Bennett, 2004; Miller, 1973).

A recurrent theme in the telephone therapy literature is the need for an enhanced or ‘different kind’ of listening by the therapist, in order to accurately detect affect and emotion. This is said to involve a heightened awareness of such features as the patient's tone of voice, pitch and breath quality (e.g. Christogiorgos et al., 2010; Coman et al., 2001; Haas et al., 1996; Rosenfield, 1997, 2013; Sanders, 2007). In the absence of visual signals, there is an assertion that empathy and ‘active listening’ must be demonstrated in different, more explicitly verbalised ways (Richards and Whyte, 2011; Rosenfield, 1997, 2013; Sanders, 2007). As well as attending more acutely to the quality of the patient's vocalisations, therapists working via the telephone are advised also to be aware of the pitch, quality and tone of their own voice and how this might be experienced by their patients (Payne et al., 2006), and to adopt a more energetic and upbeat tone (Rosenfield, 1997).

Another recurring theme is the challenge of negotiating, tolerating and interpreting the meaning of silences in the telephone therapy encounter (Christogiorgos et al., 2010; Reeves, 2015; Rosenfield, 1997; Sanders, 2007). It is suggested that silences that may, in a face-to-face context, be experienced as therapeutic might instead, by phone, feel to the patient as if the therapist has disappeared or deserted them (Reeves, 2015). Likewise, over the telephone, silence from the patient may leave the therapist unsure of the ‘meaning’ of that silence, or less able to judge when it might be appropriate to employ a ‘skilful silence’ (Christogiorgos et al., 2010). In turn, these greater complexities of communication, occasioned by the lack of visual information, are believed to have a potential impact on the quality and strength of therapeutic relationship or ‘alliance’ that can be established.

At the same time, it is noted that the absence of visual co-presence can be helpful to some patients, through offering greater anonymity, reducing anxieties that may be aroused by visiting a clinic setting, and eliminating any material indications of (differential) social status (Anthony and Goss, 2003; Bakalar, 2013; Bennett, 2004; Grumet, 1979; Haas et al., 1996; Richards et al., 2006; Spiro and Devenis, 1992; Williams and Douds, 2012), all of which may enable the patient to enter into a more open and free-flowing dialogue than they might do in a face-to-face setting. Thus, from a relational and interactional perspective, there are perceived pros and cons to conducting psychological therapy over the telephone.

The present paper arises from our observation that - whether framed as a hindrance to or facilitator of therapeutic interactions - assertions in the literature about interactional differences between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy are frequently unsubstantiated by empirical, comparative evidence. The rationale for this systematic review was, therefore, to establish what research evidence exists to support such claims about the interactional differences between telephone and face-to-face therapy.

The specific objectives of this review were to: (i) identify the range of comparative empirical research on interactional differences between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy, and (ii) explore the implications of this evidence base for psychological therapy practice, professional training and further research. Our research question was: What is known, empirically, about differences in interactional features of psychotherapeutic encounters conducted face-to-face vs. by telephone?.

2. Method

2.1. Identification of studies

The paper followed the PRISMA guidelines for reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2015). To identify potentially relevant items, the following databases were searched: CINAHL Plus; Cochrane Library; Humanities Index; Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts; Medline; PsychInfo; Scopus; Web of Science. The searches were constructed using the following terms and operators: (Telephone OR Phone) AND (CBT OR Counseling OR Counselling OR IAPT OR Therapy OR Psychotherap*). Searches were conducted between 17th April 2018 and 4th May 2018. In order to capture any more recently published results, ZETOC automated literature alerts were set up covering key terms (and combinations thereof) including: telephone, phone, counselling, therapy, psychotherapy and conversation analysis. Some additional items of potential relevance were identified during the process of searching online for fulltext versions of articles returned in the initial searches, and were also screened for eligibility. Record management was supported by Endnote Online.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The key criteria for inclusion in the systematic review were:

-

•

Situated and empirical comparison of telephone and face-to-face therapy modes

-

•

A focus on interactional features of the therapeutic encounter

-

•

Mental health problems as the focus of the psychological therapy

The following paragraphs provide further explanation of how we defined these parameters.

Situated and empirical comparison: Papers had to include an empirical comparison of telephone and face-to-face therapy sessions. We did not include studies that considered only the conduct of telephone therapy, with no comparison of modes. Studies were also excluded if they compared telephone with other types of telepsychology but did not consider the face-to-face mode. Additionally, we only included studies that involved a situated comparative analysis of the therapy sessions themselves; that is to say we did not include studies that gathered retrospective reflections on the experience of having delivered/received telephone vs. face-to-face therapy, nor studies exploring ‘perceptions of’ or ‘attitudes towards’ either mode. Papers that did not feature any primary empirical research were excluded.

Interactional features: Studies had to involve a focus on interactional features of the therapeutic encounter. Here, we included such concepts as empathy, active listening, disclosure, cooperation/resistance, affiliation/disaffiliation, and alignment/misalignment, along with measures of silences, overall duration of sessions2 and ratings of therapeutic alliance. Thus, our interest was on process features of therapeutic interactions, rather than outcomes. The focus of this review was not on differences in clinical outcomes, ratings of satisfaction, attrition, compliance or cost across telephone vs. face-to-face modes. However, we note that interactional features of therapy may, in turn, have implications for such outcomes as attrition and compliance.

Mental health: Studies had to have mental health problems as the focus of the psychological therapy. Within this, we took a broad conceptualisation of mental health and included studies both of individuals with clinically diagnosed mental health conditions (e.g. depression, anxiety, psychosis, personality disorder, eating disorder) and of individuals presenting with sub-threshold psychological or emotional difficulties. Whilst recognising that psychological therapy and counselling are different types of intervention delivered by differently trained practitioners, we expected that relevant evidence and conceptual material would arise from studies based in both practice communities. Hence, in the search and selection process we also took a fairly broad concept of therapeutic intervention that included both psychological therapy and counselling for mental health-related issues. We included studies conducted among defined populations with co-occurring physical health conditions (e.g. cancer, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis) if the primary target of therapy was mental health problems among that group. However, papers were excluded if the primary target of therapy was the physical condition itself, namely studies where the ‘counselling’ being delivered was of an information, support or condition management type, (e.g. chronic pain, breastfeeding, infertility, smoking cessation or gambling) (cf. Coughtrey and Pistrang, 2016; Leach and Christensen, 2006). We also excluded studies focused on addiction and studies where the setting was sex or relationship counselling, family therapy, child behaviour therapy or career/education counselling.

Beyond the above three criteria, we kept our inclusion criteria deliberately broad in terms of population, intervention and study design. No date, geographical or language parameters were set. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 1, below.

Table 2.

Descriptive overview of included studies.

| Publication | Country | Funding | Study group or data set | Diagnostic status of participants | Intervention type | Comparative method | Interactional variable(s) considered | Raters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonioni (1973) | USA | Funding not specified (doctoral thesis) | University student volunteers (n = 20) University based counsellors (n = 10) |

No specified diagnosis | Counselling sessions of around 50 min | Experiment 10 face-to-face participants; 10 telephone participants. Each counsellor saw one patient in each mode |

|

Third party |

| Bassilios et al. (2014) | Australia | Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing | Recorded therapy sessions (n = 6607); 33% conducted by telephone | Diagnosis of depressive and/or anxiety disorder | 6–12 (or up to 18 in exceptional cases) of CBT | Observational. Analysis of service records data, comparing telephone and face-to-face sessions |

|

n/a |

| Brown (1985) | Canada | Some financial support provided by author's employing organisation, within which the research was conducted (doctoral thesis) | Case records of individuals using an Employee Assistance Programme (n = 456) Counsellors (n = 20) |

No specified diagnosis | Employee Assistance Programme. Type of counselling not further specified | Observational. Analysis of case records, comparing telephone and face-to-face sessions. |

|

Therapist |

| Daniel (1973) | USA | Funding not specified (doctoral thesis) | Undergraduate students (n = 41) | No specified diagnosis | One 30 min counselling session | Experiment 19 face-to-face participants, 22 telephone participants |

|

Third party |

| Day and Schneider (2002) | USA | Partially funded by a University of Illinois Graduate College Dissertation Grant (1998) and a University of Illinois Research Board Grant (1998) | Adults recruited from general population (n = 80) | No specified diagnosis | 5 sessions of CBT | Experiment 27 face-to-face participants, 26 video participants, 27 audio participants (plus wait list control) |

|

Third party |

| Dilley et al. (1971) | USA | Funding not specified | University students (n = 3) Counsellors (n = 15) |

No specified diagnosis | Counselling (not further specified) | Experiment 3 conditions: face-to-face, confessional style, telephone. Each participant took part in all three conditions |

|

Third party |

| Fann et al. (2015) | USA | Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R21HD53736) and the Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant H133G070016) | Adults within 10 years of complicated mild to severe traumatic brain injury (n = 100) | Diagnosis of major depressive disorder | 12-session brief cognitive behavioural therapy. Sessions of 30–60 min | Experiment. 40 telephone participants, 18 face-to-face participants, 42 usual care |

|

Patient |

| Hammond et al. (2012) | UK | Authors’ posts variously supported by the National Health Service, Department of Health and National Institute of Health Research | Adults referred to low-intensity mental health service (n = 294) | Diagnosis of mild to moderate depression and/or anxiety | 2 or more sessions of CBT | Observational. Analysis of service records data, comparison of propensity matched face-to-face vs. telephone patients. |

|

n/a |

| Himelhoch et al. (2013) | USA | Project supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R34- MH80630) | Urban-dwelling HIV-infected individuals (n = 34) | Diagnosis of major depressive disorder and scores of 12+ on PHQ-9 | 11-session manualised CBT intervention | Experiment. 18 face-to-face participants, 16 telephone participants (plus treatment as usual control) |

|

Patient |

| Hinrichsen and Zwibelman (1981) | USA | Funding not specified | Case records of students using university counselling service (n = 6178) | No specified diagnosis | Counselling (not further specified) | Observational. Analysis of service records data, comparison of face-to-face and telephone sessions |

|

n/a |

| Mulligan et al. (2014) | UK | National Institute for Health Research under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0606-1086) | Patient-therapist dyads (n = 21) | Diagnosis of non-affective psychosis (ICD-10) | Recovery-focused CBT | Observational (external) Study sample is of telephone participants only; findings are compared with those of previous studies that used a face-to-face sample |

|

Patient and therapist |

| Reese et al. (2002) | USA Canada Mexico | Funding not specified – but article based on doctoral thesis | Individuals using an Employee Assistance Programme (n = 186) |

No specified diagnosis | Employee Assistance Programme, therapists trained in Solution Focused Therapy | Observational (external) Study sample is of telephone participants only; findings are compared with those of previous studies that used a face-to-face sample |

|

Patient |

| Spizman (2001) | USA | Funding not specified (doctoral thesis) | University students (n = 31) | No specified diagnosis | Four 50-min sessions of counselling | Experiment 12 telephone participants, 12 face-to-face, 7 wait list control |

|

Patient and therapist |

| Stephenson et al. (2003) | USA | Funding not specified | Individuals using an Employee Assistance Programme (n = 21,000 +) | No specified diagnosis | Employee Assistance Programme (type of counselling not further specified) | Observational. Analysis of service records data, comparing telephone sessions with face-to-face sessions |

|

Patient |

| Stiles-Shields et al. (2014) | USA | Supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH059708 | Primary care patients (n = 325) (n therapists not specified) |

Diagnosis of major depressive disorder | 18 sessions of CBT | Experiment. Face-to-face and telephone session ratings compared, respectively 140 vs. 149 patient ratings; 138 vs. 153 therapist ratings |

|

Patient and therapist |

Table 1.

Summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria for selection of publications.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. Quality assessment

Our review deliberately included a wide range of comparative study designs (trials and various types of observational designs). After the final list of included studies was identified, we developed an approach to quality assessment that was better suited to this variability, and which was designed to focus on the different types of design included in the review, rather than provide a highly detailed assessment of a single design (such as trials).

-

1Bias in the comparison of face-to-face and telephone therapy. We distinguished three groups of studies, in terms of descending risk of bias in the comparison of the two modes of delivery:

-

aexperimental studies that allocated patients at random (or using some other quasi-random allocation mechanism) to face-to-face and telephone therapy

-

bobservational studies that compared face-to-face and telephone therapy in patients within the same sample, controlling for other characteristics of the patients

-

cobservational studies that compared telephone therapy to patients in face-to-face therapy in external, published studies

-

a

-

2

Measurement of outcome. We distinguished studies in terms of the evidence of the validity of their measurement instruments (essentially, whether they used a published measure), and the type of rater (participant versus external observer). Evidence of validity of measurement was a clear marker of quality. However, we did not identify one type of rater as superior, as both approaches have advantages and disadvantages.

-

3

Representativeness of the sample. We distinguished studies according to whether they were conducted in routine clinical settings with patients with a formal mental health diagnosis, or used student populations, employee assistance programmes or self-referred community samples. The former studies are expected to have greater external validity in generalising to mental health service settings, which is our primary focus.

3. Data extraction and synthesis

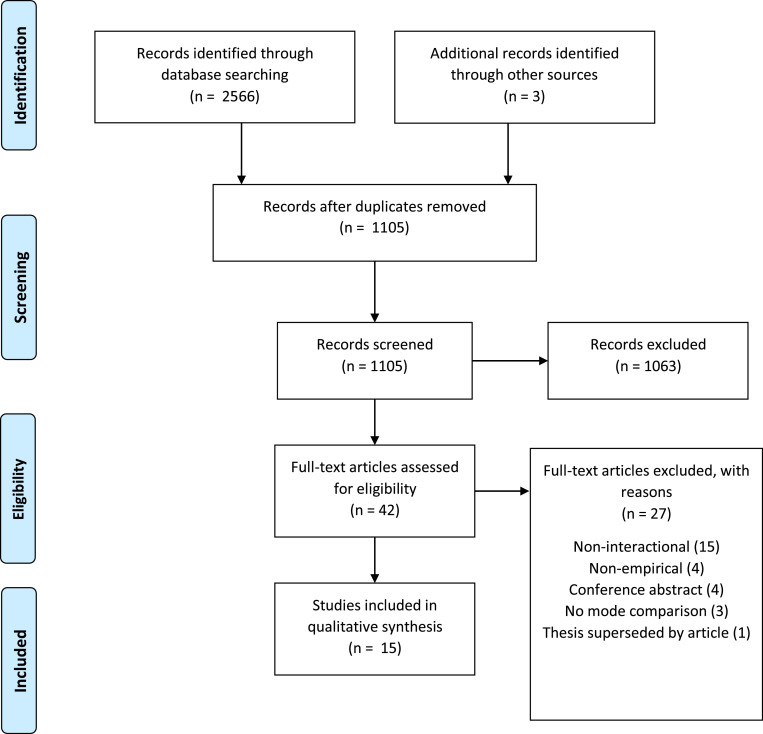

Fig. 1 shows the outcome of the literature searches and selection process, following the preferred reporting items of systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2015). After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 1105 items were screened for relevance by one researcher (Irvine). Two further researchers (Brooks and Gellatly) checked a random selection of 132 items (just over 10% of results) to reduce risk of bias and corroborate the first researcher's screening judgements.

Fig. 1.

Item selection process using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA: Moher et al., 2015).

Forty-two items were selected for full examination and were considered independently by three researchers (Irvine, Gellatly and Brooks). A small number of discrepancies in the researchers’ assessments of the items were resolved through clarification of how ‘mental health problem’ was being defined within the inclusion criteria. Following further exclusions (see Figure 1 for reasons), fifteen studies were included in the final review.

3.1. Data extraction

One researcher (Irvine) extracted key information from the 15 studies into an Excel spreadsheet containing the following column headings:

-

•

Author(s)

-

•

Year

-

•

Title

-

•

Country

-

•

Aims/purpose/research questions

-

•

Participants/sample

-

•

Psychotherapeutic intervention and (as applicable) comparator

-

•

Method(s) used in comparative study

-

•

Variables/measures of relevance to systematic review

-

•

Key findings of relevance to this review

The data extraction chart was checked for accuracy and comprehensiveness by two additional researchers (Gellatly and Brooks), each reviewing approximately half of the fifteen papers. No errors were identified in the first reviewer's extraction, but the secondary reviewers made some minor additions to the data extraction chart. Following further discussion among the three reviewers, certain features of studies were more systematically extracted, namely whether or not the study population had a clinical diagnosis of a mental health condition, and whether ratings of interactional features were made by subjects (patients and/or therapists) or by third parties (e.g. investigators or trained assistants).

A more succinct table of summary data was then produced by the first reviewer, and explored by all contributing authors to arrive at a thematic description of the content and provisional implications of the data set. This summary of findings and implications was also presented to a stakeholder consultation group, The EQUITy Lived Experience Advisory Panel, comprising seven people with lived experience of common mental health problems and primary care mental health services. Their reflections are incorporated in the final analysis that appears below.

3.2. Meta-analysis

Two researchers (Bee, Bower) independently extracted quantitative data from published papers on our outcomes of interest. Where a number of studies reported the same outcome with all necessary data, we subjected the data to meta-analysis, using a random effects model due to the clinical and methodological diversity in the included studies. We used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, reporting results as a standardised mean difference and 95% confidence interval (together with the I2 statistic as a measure of inconsistency). Where we were unable to identify appropriate data for meta-analysis (either because particular outcomes were only reported by a single study, or because only a single study reported meta-analysable data), we describe the results narratively.

3.3. Characteristics of included studies

The 15 included studies were conducted between the years 1971 and 2015, with the majority having been published from 2000 onwards. Eleven studies emanated from the USA with small numbers conducted in Australia, Canada, Mexico and the UK.

In terms of our quality assessment, eight studies were experimental, five were observational studies comparing face-to-face and telephone therapy in patients within the same sample, and two studies were observational studies comparing telephone therapy to patients in face-to-face therapy in external, published studies. Regarding measurement of outcome, nine studies used validated measurement instruments, while three used rating scales developed for the study (three reported only data on duration). Eight studies used participant ratings, and four used external observers (three reported only data on duration).

In terms of the representativeness of the sample, six studies were of patients in clinical settings where patients had a diagnosis of a mental health disorder, whilst nine studies comprised samples of people whose mental or emotional difficulties did not necessarily reach a diagnostic threshold and were conducted in other settings, including educational and occupational contexts. Participants across the 15 studies variously included adults in contact with clinical or community services, university students, adults accessing Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs) and adults recruited from the general population.

Seven studies specified Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) as the therapeutic technique used in the intervention, seven described the intervention as ‘counselling’ with no further specification, and one stated that therapists delivering the intervention were trained in Solution-Focused Therapy. As we discuss in more detail in the following section, variables or measures considered across the group of studies included: duration, alliance, disclosure, empathy, attentiveness and participation.

3.4. Interactional variables addressed by the studies

In this section, we describe the range of interactional variables addressed by the 15 studies and the findings that emerge from their comparison of modes. We have grouped the interactional variables thematically under six headings: duration, alliance, disclosure, empathy, attentiveness and participation. Some themes were common to a relatively larger number of papers and we present findings in that order. However, we do not draw any inferences relating to the frequency of themes, particularly as we recognise a degree of conceptual overlap in some cases. Table 3 provides an overview of the different types of interactional variable considered in the 15 studies and summarises their key findings (papers ordered alphabetically).

Table 3.

Thematic summary of systematic review findings.

| Theme | Findings |

|---|---|

| Duration |

Telephone sessions tend to be shorter:Meta-analysis: telephone treatments significantly shorter than face-to-face treatments (standardised mean difference -1.09, 95% CI -1.41 to -0.77, I2 =86.7%) |

| Alliance | No significant difference (sometimes higher in telephone mode):Meta-analysis: telephone treatments associated with higher ratings of the working alliance measures, although differences not significant (standardised mean difference .16, 95% CI -0.12 to .45, I2 = 62.6%). |

| Disclosure Openness Revealing of sensitive information Self-exploration Counsellor concreteness Affective self-reference |

No significant difference:Introverted patients use more affective self-reference over the phone than face-to-face:Greater amount of total self-reference face-to-face: |

| Empathy | No significant difference: |

| Attentiveness How closely therapist listened How much therapist cared/listened |

No significant difference:Telephone patients gave higher ratings: |

| Participation |

Patients participated more actively in telephone mode:No significant difference: |

statistically significant difference reported

Duration:

Seven studies reported on the length of therapy sessions (Bassilios et al., 2014; Brown, 1985; Daniel, 1973; Fann et al., 2015; Hammond et al., 2012; Hinrichsen and Zwibelman, 1981; Stephenson et al., 2003). These seven studies consistently found that telephone sessions were shorter than those delivered face-to-face, with three (Fann et al., 2015; Hammond et al., 2012; Stephenson et al., 2003) reporting statistically significant differences between modes.

In an analysis of service records data, Bassilios et al. (2014) found that 47% of telephone sessions were shorter than half an hour, compared to just 7.4% of face-to-face sessions; conversely 58.8% of face-to-face sessions lasted 45–60 min, compared to 35.3% of telephone sessions. In an experimental study, where counselling sessions were intended to last around 30 min, Daniel (1973) reported typical lengths of telephone sessions being 25–30 min and face-to-face sessions lasting 35–40 min. Describing a peer-counselling service that offered walk-in and telephone contacts, Hinrichsen and Zwibelman (1981) reported telephone contacts lasting on average 10.5 min and face-to-face contacts lasting an average of 25.62 min.

Brown's (1985) method of reporting session duration is somewhat difficult to interpret, as she converted time brackets to integers, resulting in a very ‘ballpark’ comparison. However, the overall picture is that initial counselling sessions conducted by telephone were shorter, typically falling somewhere between the 15–30 min and the 31–45 min brackets, compared to initial face-to-face sessions, which typically fell somewhere between 31–45 min and 46–60 min. However, for subsequent counselling contacts, Brown (1985) reported that the typical duration for both modes was very similar and fell somewhere between the <30 min and the 31–60 min brackets.

In a choice-stratified RCT, Fann et al.’s (2015) average length of telephone session was 42.5 min, compared to an average of 50.4 min for face-to-face (p = .001). Stephenson et al. (2003) reported statistical significance in their finding of an average of 32.2 min (telephone) vs. 59.8 min (face-to-face) among users of an EAP. Drawing on service records data, Hammond et al. (2012) reported the total duration of therapist-patient contact over an intervention of at least two sessions of therapy. Patients seen face-to-face received on average 3 h 27 min of treatment compared to 2 h 20 min for telephone patients. This equates to 32.6% shorter contact time for telephone patients (p = .001).

Overall, despite much variation in the measurement and reporting mechanisms used by different studies, there is a clear finding that telephone therapy sessions tend to be shorter than those conducted face-to-face. For clarity, we highlight that this finding arises from studies in which there was no a priori intervention design or service model that specified that telephone interventions would be of a shorter duration.

We were able to conduct a meta-analysis of data on duration from four studies (Bassilios et al., 2014; Brown, 1985; Fann et al., 2015; Hammond et al., 2012). This revealed that telephone treatments were significantly shorter than face-to-face treatments (standardised mean difference -1.09, 95% CI -1.41 to -0.77, I2 =86.7%).

Alliance:

Five studies (Fann et al., 2015; Himmelhoch et al., 2013; Mulligan et al., 2014; Reese et al., 2002; Stiles-Shields et al., 2014) considered patient and/or therapist ratings of therapeutic alliance across telephone and face-to-face therapy sessions, using versions of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath and Greenberg, 1989).

Fann et al. (2015) found that patient ratings of working alliance across telephone and in-person CBT did not differ overall or on any of the three subscales (task agreement, therapeutic bond, goal agreement) of the WAI-short form. Similarly, Himmelhoch et al. (2013) and Stiles-Shields et al. (2014) found no significant differences in the working alliance scores of patients randomised to telephone or face-to-face psychological therapy. Additionally in the Stiles-Shields et al. (2014) study, working alliance ratings given by therapists did not differ between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy.

Rather than conducting an empirical comparison within their own study, both Mulligan et al. (2014) and Reese et al. (2002) compared their WAI results for telephone therapy patients against the reported figures of comparable studies that measured WAI among face-to-face therapy participants. In both cases, the authors reported similar scores between their own telephone therapy samples and other studies’ findings from face-to-face cohorts.

We were able to conduct a meta-analysis of data on alliance from five studies (Fann et al., 2015; Himmelhoch et al., 2013; Mulligan et al., 2014; Reese et al., 2002; Stiles-Shields et al., 2014). The meta-analysis indicated that telephone treatments were not associated with significantly higher ratings of the working alliance measures (standardised mean difference .16, 95% CI -0.12 to .45, I2= 62.6%), although the direction of effect was in the opposite direction to ‘received wisdom’ about the effect of the telephone on therapeutic alliance, i.e. telephone treatments were associated with higher ratings of working alliance.

Disclosure:

Four studies (Antonioni, 1973; Brown, 1985; Daniel, 1973; Spizman, 2001) considered variables that we have grouped under the heading Disclosure. In a study of EAPs, and drawing on counsellors’ ratings of their patients, Brown (1985) found there was no difference in ratings of ‘openness or revealing of sensitive information’ attributed to patients engaging in telephone or face-to-face counselling. Similarly, Spizman (2001) found no significant difference in patient or therapist ratings of the extent to which patients disclosed personal information during counselling.

Antonioni (1973) approached the topic of openness in terms of ‘client self-exploration’, conceptualised as the extent to which ‘the client voluntarily introduces personally relevant material and shows emotional proximity to what is being said’ (Antonioni, 1973, p.6). When rated by a third-party observer, using the Carkhuff scale for Assessment of Interpersonal Functioning (Carkhuff, 1969), no significant difference was found in the extent of patient self-exploration across telephone and face-to-face modes. However, in a separate post-intervention questionnaire administered to patients themselves, 78% felt that their counsellor understood and aided their self-exploration to a greater degree in the face-to-face mode than when communicating via telephone. Antonioni (1973) also found comparable ratings across modes in terms of ‘counsellor concreteness’, this being conceptualised as ‘how effective the counsellor is in enabling the client to discuss personally relevant material in specific and concrete terms’ (Antonioni, 1973, p.6).

Daniel (1973) used the Salzinger and Pisoni (1958) measure of total self-reference/affective self-reference (ASR/TSR ratio) to explore the extent to which counselling patients talked about affective feelings during sessions conducted face-to-face and by telephone. Overall, no significant difference was found in ASR/TSR ratios between modes. However, when subgroups were compared, introverted individuals had significantly higher ASR/TSR ratios when taking part in telephone counselling than during face-to-face sessions, whilst the reverse was true for extroverted individuals. This can be interpreted as introverted individuals being significantly more inclined to reveal their feelings in telephone interviews than they are in face-to-face encounters.

Empathy:

Two studies (Antonioni, 1973; Dilley et al., 1971) used the Carkhuff scale for Assessment of Interpersonal Functioning (Carkhuff, 1969) to explore counsellor empathy in the context of a university counselling service. Both studies reported findings of no significant difference between third-party ratings of counsellor empathy in the telephone vs. face-to-face modes. Antonioni (1973) noted, however, that in their post-session questionnaire, counsellors reported feelings of inferiority or inadequacy of the telephone mode compared to face-to-face, e.g. that they felt that ‘part of the person was missing’ or that they wanted more visual cues in order to assess their patient's reactions. Antonioni thus highlighted a discrepancy or gap between the apparently effective communication of empathy via telephone (when externally rated) and counsellors’ own perceptions that the mode detrimentally affects the interaction.

Attentiveness:

Two studies (Spizman, 2001; Stephenson et al., 2003) considered the concept of how much or how well the therapist listens, which we have termed Attentiveness. Stephenson et al. (2003) found no significant differences between telephone and face-to-face patient ratings of how ‘closely’ they perceived their therapist had listened. Spizman (2001) developed a measure of patient-reported ‘connection’ that combined responses to single item questions on how much their therapist listened to them, how caring the therapist was, and how much the patient liked their therapist. This composite measure, within which the therapists’ listening behaviours were rated, produced significantly higher ratings from those receiving telephone counselling than those in a face-to-face setting (F test of Difference 3.06; p < .12).

Participation:

Two studies (Day and Schneider, 2002; Spizman, 2001) considered patients’ degree of participation in the therapy session. Day and Schneider (2002) applied the Vanderbilt Psychotherapy Process Scale (VPPS) to a sample of face-to-face, video and audio (i.e. telephone) therapy sessions. On the Client Participation dimension of the VPPS, which includes ratings of patients’ activity level, initiative, trust, spontaneity and disinhibition, Day and Schneider (2002) found that patients participated significantly more actively in both of the distance modes (video and audio) than they did in the face-to-face setting. Day and Schneider (2002) suggested that this finding may be related to increased patient efforts to communicate when not co-located with the therapist, or to the enhanced sense of ‘safety’ engendered by a distance mode. Using a single item question, Spizman (2001) also considered patients’ level of participation in telephone vs. face-to-face therapy sessions, but found no significant association between mode and patient- or therapist-reported participation.

4. Discussion

This systematic review set out to discover what empirical research can tell us about interactional difference between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy. Our objectives were to identify the range of extant research on this topic and to consider implications for practice and for future research. We consider each of these in turn.

4.1. Evidence on interactional difference

The most striking finding of this review is that, for the most part, we found no evidence of mode-related difference in a range of interactional features including therapeutic alliance, disclosure, empathy, attentiveness or participation. According to the results of this review, there is no empirical evidence to corroborate perceptions that the telephone mode, specifically its absence of visual and physical co-presence, is detrimental to alliance formation. The consistent finding is that alliance is rated similarly across modes, whether by therapists, patients or third party raters. Likewise, the review did not find any evidence that empathy, attentiveness or participation suffer through the telephone mode of communication.

Studies of patient-rated importance of various factors in the formation of therapeutic alliance reveal that, whilst eye contact is considered amongst the most important individual factors, non-verbal gestures and body language as a whole are rated as significantly less important than therapist validation of the patient's experience (Bedi, 2006; Bedi and Duff, 2014). Validation involves such therapist actions as normalizing the patient's experience, framing it as reasonable or understandable, identifying and reflecting back feelings, paraphrasing, agreeing, and making encouraging and comments (Bedi, 2006); significantly, none of these are reliant on visual co-presence.

Some scholars (e.g. Lingley-Pottie and McGrath, 2007; Turner et al., 2018; Webb, 2014) point to the possibility that in telephone-delivered therapy there may be an alternative type of alliance at work, one that is qualitatively different to that which is established face-to-face but is nonetheless facilitative of therapeutic work. As Webb (2014, p.30) notes: “Effective alliance via the telephone may be an overlapping but non-identical construct to our current understanding of the face-to-face alliance … there appears to be a distinct possibility that a new model conceptualising ‘distance’ therapeutic alliance is needed”. In her qualitative study of CBT practitioners, Webb (2014), noted a perception amongst therapists that both they and their patients were more ‘treatment focused’ over the phone, having a tendency to adhere more narrowly during sessions to the CBT tasks at hand. Webb thus suggests that the ‘task’ dimension of the therapeutic alliance may be magnified in telephone therapy, and may in some way be compensating for any reduction in (traditionally conceptualised) ‘bond’. Furthermore, Lingley-Pottie and McGrath (2007) propose that the visual anonymity of the telephone should be conceptualised as an additional, unique and beneficial dimension of therapeutic alliance.

Turning to the concept of disclosure, the findings of studies included in this review again revealed a lack of significant differences across modes. Patients’ comparable degrees of openness, self-exploration or disclosure of sensitive/personal information between modes challenge both those that have argued the greater anonymity of the phone encourages disclosure and those who suggest that the lack of an in-person connection might inhibit openness. These findings suggest it is perhaps other (inter)personal factors, rather than the communication mode itself, that are more influential on whether or not patients ‘open up’ to their therapist. For example, Janofsky (1970) found that whilst there were no significant mode-related differences between the amount of ‘affective self-disclosure’ when comparing brief conversations between strangers over the phone and face-to-face, there was a significant effect of participant sex, with female participants producing a greater number of affective self-references than males during their interactions. Daniel's (1973) findings on introversion-extroversion, described above, also support the speculation that communication channel itself is not the most influential factor in disclosure of feelings and emotions.

Only in respect of duration of sessions did we find any evidence of consistent mode-related difference, with telephone sessions being consistently and significantly shorter than those conducted face-to-face. Stephenson et al. (2003) speculate as to whether the longer duration of face-to-face sessions is related to normative understandings and expectations of a typical therapy session, norms that may not apply to the more novel mode of telephone therapy: “If clients make the effort to see the counselor in person, both the client and the counselor may adhere to the traditional, hour-long counseling session. However, since telephone sessions have never had standard length of time associated with them, both counselor and client may end the session at what feels to be its natural close” (Stephenson et al., 2003, p.31).

Moving away from the directly comparative element of their study, but potentially related to the relative brevity of telephone sessions, Stephenson et al. (2003) noted a perception among counsellors that, compared to face-to-face sessions, telephone sessions adhered to a more structured format and stayed more on-task. Similarly, Daniel (1973, p.62) observed that in telephone counselling sessions, ‘both interviewer and interviewee had a more problem-solving, task-oriented approach when the contact was by telephone’, concluding that telephone sessions were more ‘direct’, ‘efficient’ and that ‘the reduced impact of verbal cues alone which occurs on the telephone seems to lend itself to a more get down to business effect’ (Daniel, 1973, p.65). These views echo the findings of Webb (2014), who also describes a perception among therapists that it is easier to stick to time boundaries when conducting sessions over the phone.

Some commentators frame the shorter duration of telephone therapy as an economic and resource efficiency for services (e.g. Hammond et al., 2012; Lovell et al., 2006; Stephenson et al., 2003), and suggest that this time saving should be embraced and if possible enhanced (Hammond et al., 2012). However, it remains an untested question as to whether this regularly observed shorter duration is a positive or productive effect of more succinct communication and timekeeping over the telephone, or rather results from some kind of interactional deficit or difficulty that leads to foreshortened encounters. For example, Brown (1985. p.12) suggests that ‘the speed of telephone interviews may yield more superficial responses to questions’ whilst Webb's (2014) participants experienced some reduction in the relational aspects of their practice as a counterpart to their greater task focus, when working by telephone. In consultation with a Lived Experience Advisory Panel, during the development of this paper, the question was also raised of who is ‘driving’ the shorter duration of telephone therapy sessions: is it primarily the patient, the therapist or some mutual collaborative process that results in a shorter encounter?

4.2. Implications for practice

Overall, this review highlights something of a paradox, noted also by Antonioni (1973), that despite empirical studies consistently showing no significant difference in interactional features of alliance, empathy and so on, therapists nonetheless remain ambivalent about the use of this medium. Antonioni (1973) suggests that this contradiction stems from counsellors believing that they rely more on visual than auditory cues, and hence perceiving an inferiority of the telephone medium - despite objective clinical evidence not supporting this viewpoint.

According to the current evidence base, the telephone mode does not apparently make a difference to anything except the duration of patient contacts. However, effecting a change in practice requires more than simply informing practitioners of this evidence base. Indeed, in our consultation with the Lived Experience Advisory Panel, it was highlighted that perceptions can be extremely influential and persist even in the absence of evidence. We know that more nuanced forms of intervention are required to effect change in practitioner attitudes and behaviours, and that barriers to change lie not only at the individual or interpersonal level, but also at the systems level (Bee et al., 2016).

We also recognise that there are multiple broader considerations involved in determining the suitability of different modes for any given patient, including practical logistics, assessment of risk, and indeed that going out to engage in a face-to-face appointment may be part of the therapeutic process for some patients. As emphasised in consultation with the EQUITy Lived Experience panel, patient choice and preference must remain at the heart of service provision.

4.3. Implications for research

This review identified only 15 studies published over a period of almost 50 years. It is striking that so little comparative empirical research has been conducted in this field, and that there seems no particular indication of an upsurge in interest in this topic accompanying the growth of telephone-delivered therapies. Notably, given the significance of silence in the therapeutic encounter, and recurrent commentary on how this may be more challenging to negotiate over the telephone, we found no comparative studies examining this topic (though we note the work of Chatwin et al. (2014) on silence in telephone-delivered CBT).

Furthermore, we identified no empirical studies using methodologies that enable a fine-grained analysis of specific interactional detail. The small body of comparative literature uncovered in this review is dominated by studies that use ratings scales and quantitative measures, rather than methods drawn from communication and interaction studies. Given the need to challenge embedded perceptions with specific, grounded and persuasive evidence, we argue that this represents a significant research gap. For example, whilst ratings of therapeutic alliance certainly speak to the interpersonal significance of therapy encounters, they are nevertheless not a direct analysis or assessment of the interactional features of therapy. As noted by Bedi and Duff (2014, p.15), ‘a client's subjective experience of establishing a therapeutic alliance cannot be equated with and is therefore not synonymous with the actual, interactive process of therapeutic alliance formation’.

We propose the method of Conversation Analysis as a fruitful way forward in shedding empirical light on the specific features of telephone-delivered psychological therapy (cf. Chatwin et al., 2014). The method of Conversation Analysis (CA) offers a proven method for adding understanding to the interactional processes of clinical encounters (Drew et al., 2001; Heritage and Maynard, 2006; Heritage and Robinson, 2006; Perakyla et al., 2008; Robinson, 2003; Robinson and Heritage, 2006). CA is a largely qualitative method for investigating the dynamics of interactions in all kinds of encounters, including a range of medical and (psycho)therapeutic interactions. CA is being widely applied to uncover the interactional/communicative practices used by medical professionals and patients/clients, and to identify those practices that are more effective than others (Ekberg et al., 2015; Heritage et al., 2007; Heritage et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2016).

Regarding the shorter duration of telephone therapy sessions, a closer interactional examination of psychological therapy sessions conducted face-to-face and by telephone could shed more informative light on what this ‘extra’ length of face-to-face therapy sessions comprises, or framed the other way, what is ‘missing’ from telephone therapy sessions. More broadly, a conversation analytic approach would permit a close and situated analysis of how such core therapeutic activities as expectation setting, problem identification, goal agreement and the practices of active listening and management of silence are negotiated and accomplished during the interaction itself. It could illuminate what alliance formation - and potentially the processes of alliance rupture and repair (Safran et al., 1990) - ‘look like’ in practice, and where there might be scope to intervene in and influence this process through practitioner training.

Finally, we note that the 15 included studies used a range of different therapeutic modalities (e.g. CBT, counselling, Solution-Focused Therapy) and varied in the of type and severity of mental health problem. It is possible that the effect of the telephone is different in each of these therapy contexts, depending on, for example, the extent to which treatment follows a guided self-help vs. interpersonal model, and the nature of mental health symptomatology being addressed. Amongst the existing body of comparative literature identified here, we note the predominance of depression and broadly specified (subthreshold) psychological difficulties. As found by Leach and Christensen (2006), it appears that the majority of research on telephone therapy remains focused on common mental health conditions with a relative lack of evidence on the use of the telephone for conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Lastly, effects may be influenced by therapist allegiance with modality, therapist expertise and patient preference. These factors will all be important to explore in future research.

5. Limitations

This review is based on only a small number of heterogeneous studies, a number of which used non-randomised, opportunity samples and did not use validated measures to assess the constructs under investigation. Some studies developed their own ratings scales, and there was inconsistency in the conceptualisation of some of the constructs of interest. Moreover, a range of different therapeutic modalities were used across the included studies, and samples included both clinically diagnosed and non-clinical populations.

We adopted a framework for quality assessment that allowed us to include the range of designs included in the review, but to distinguish those designs most able to support causal statements and those which were more vulnerable to confounding. Our framework also allowed us to explore issues of specific interest to this review, such as measurement methods and external validity of the studies. However, our framework, lacked the granular assessment of quality frameworks used for single designs (such as the Cochrane risk of bias tool used for trials) and therefore did not provide a detailed assessment of quality within designs. Given the small number of studies included in the review, such a detailed assessment was unlikely to substantively impact on the overall review findings. The results of the meta-analyses showed relatively high levels of inconsistency and therefore the results should be interpreted with caution. The small numbers of studies in each analysis made meaningful assessment of this inconsistency difficult.

Due to our specific focus on situated comparative studies, we excluded several non-comparative qualitative and interactional studies that make an important contribution to this area of understanding. Hence, whilst the present paper offers a unique analysis of directly compared interactional features, we recognise that this approach provides only one part of the knowledge that is required in order to address resistance and barriers to uptake of telephone psychological therapy. We also acknowledge that this paper has not addressed online modes of therapy, which are growing exponentially alongside the continued use of the telephone. Yet, the telephone is frequently used as an adjunct to support online therapies and so arguably has significance to the spectrum of distance therapeutic modes.

6. Conclusion

At a time when demand for mental health services is high, we need more efficient service models and systems that overcome the barriers posed by patient illness and competing responsibilities. The telephone is a convenient, reliable and virtually universal communication channel. Yet despite evidence of comparable clinical outcomes, adoption amongst services is challenged by practitioner ambivalence, embedded views and systems that favour face-to-face (Bee et al., 2016). This review identified only a small and heterogeneous group of studies on interactional difference in telephone and face-to-face therapies, limiting the strength of any conclusions that can be drawn at this stage. However, the available evidence does suggest a lack of support for arguments that the telephone has a detrimental effect on interactional aspects of psychological therapy. The challenge is to translate this evidence into a change in practice behaviours. In order to do so, it is important to understand and address the breadth of factors that underpin ongoing resistance to the telephone mode among therapists, and which pose a barrier to wider implementation. The study has also identified research questions about the source and implications of durational difference between telephone and face-to-face therapy sessions, and limited evidence on the nature of silence in telephone therapy encounters. Exploring these questions, through the use of interactional methods such as Conversation Analysis, may reveal whether the more concise nature of telephone therapy is uniquely an economic benefit or may simultaneously be a cost to the therapeutic interaction.

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research award (RP-PG-1016-20010). NIHR had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) [Enhancing the quality of psychological interventions delivered by telephone (EQUITy), RP-PG-1016-20010]. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Annie Irvine: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Paul Drew: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Peter Bower: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing. Helen Brooks: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Judith Gellatly: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Christopher J. Armitage: Writing - review & editing. Michael Barkham: Writing - review & editing. Dean McMillan: Writing - review & editing. Penny Bee: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the EQUITy Lived Experience Advisory Panel (EQUITy LEAP) for their insightful comments and feedback on an earlier draft of this review. Christopher Armitage's role was supported by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre and NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre.

Footnotes

Enhancing the quality of psychological interventions delivered by telephone (EQUITy), funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (RP-PG-1016-20010)

We consider duration to be relevant as an interactional feature because it is a reflection, or product, of the overall interactional process. It is of particular relevance in the psychotherapeutic setting, given the import placed on silences – their occurrence, frequency and duration – and on the elicitation of ‘extended’ turns at (reflective) talk from the patient. For examples of the interactional relevance of duration in healthcare encounters, see Heritage and Robinson, 2006; Robson et al., 2013.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.057.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- American Psychological Association2013. Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology. https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/telepsychology.aspx (accessed 19 July2019).

- Anthony K., Goss S. Conclusion. In: Anthony K., editor. Technology in Counselling and Psychotherapy: A Practitioner's Guide. Palgrave; London: 2003. pp. 195–208. Goss S. Eds. [Google Scholar]

- Antonioni, D.T., 1973. A field study comparison of counselor empathy, concreteness and client self-exploration in face-to-face and telephone counseling during first and second interviews(Doctoral Thesis). University of Wisconsin, USA.

- Bakalar N.L. Transition from in-person psychotherapy to telephone psychoanalysis. In: Scharff J.S., editor. Psychoanalysis Online: Mental Health, Teletherapy, and Training. Karnac Books; London: 2013. pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bassilios B., Pirkis J., King K., Fletcher J., Blashki G., Burgess P. Evaluation of an Australian primary care telephone cognitive behavioural therapy pilot. Aust. J. Primary Health. 2014;20:62–73. doi: 10.1071/PY12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R.P. Concept mapping the client's perspective on counselling alliance formation. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2006;531:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R.P., Duff C.T. Client as expert: A Delphi poll of clients’ subjective experience of therapeutic alliance formation variables. Counsell. Psychol. Quart. 2014;271:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bee P., Lovell K., Airnes Z., Pruszynska A. Embedding telephone therapy in statutory mental health services: a qualitative, theory-driven analysis. BMC Psych. 2016:1656. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0761-5. doi: 10.1186%2Fs12888-016-0761-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. Viewing telephone therapy through the lens of attachment theory and infant research. Clin. Social Work J. 2004;323:239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath D.D. Orienting clients to telephone coaching in dialectal behavior therapy. Cognit. Behav. Pract. 2015;22:407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. J., 1985. Antecedents of compliance in employee assistance programs: telephone vs. face-to-face communications(Doctoral Thesis). University of Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

- Carkhuff R.R. Holt, Rinehart Winston; New York: 1969. Helping and Human Relations (two vols) [Google Scholar]

- Castro A., Gili M., Ricci-Cabello I., Roca M., Gilbody S., Ángeles Perez-Ara M. Effectiveness and adherence of telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;260:514–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatwin J., Bee P., Macfarlane G., Lovell K. Observations on silence in telephone delivered cognitive behavioural therapy T-CBT. J. Appl. Linguist. Profess. Pract. 2014;111:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Christogiorgos A., Vassilopoulou V., Florou A., Xydou V., Douvou M., Vgenopoulou S., Tsiantis J. Telephone counselling with adolescents and countertransference phenomena: particularities and challenges. Br. J. Guidance Counsell. 2010;383:313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Coman G.J., Burrows G.D., Evans B.J. Telephone counselling in Australia: applications and considerations for use. Br. J. Guidance Counsell. 2001;292:247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coughtrey A.E., Pistrang N. The effectiveness of telephone-delivered psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: a systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2016;242:65–74. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16686547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, L.S., 1973. A study of the influence of introversion-extraversion and neuroticism on telephone counseling vs. face to face counselling(Doctoral Thesis). University of Texas, Austin, USA.

- Day S.X., Schneider P.L. Psychotherapy using distance technology: a comparison of face-to-face, video, and audio treatment. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2002;494:499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Dilley J., Lee J.L., Verrill E.L. Is empathy ear-to-ear or face-to-face? Personnel Guidance J. 1971;503:188–191. [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin R.D., Menza M., Allen L.A., Tiu J., Friedman J., Bienfait K.L. Telephone-based cognitive–behavioral therapy for depression in Parkinson disease. J. Geriatric Psych. Neurol. 2011;24:206–214. doi: 10.1177/0891988711422529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew P., Chatwin J., Collins S. Conversation analysis: a method for research into interactions between patients and health-care professionals. Health Expectat. 2001;4:58–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg S., Barnes R.K., Kessler D.S., Mirza S., Montgomery A.A., Malpass A., Shaw A.R.G. Relationship between expectation management and client retention in online cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav. Cognit. Psychoth. 2015;436:732–743. doi: 10.1017/S1352465814000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt H., Landau S., O'Reilly G., Sibelli A., Hughes S., Windgassen S. . Cognitive behavioural therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: 24-month follow-up of participants in the ACTIB randomised trial. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;4:863–872. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fann J.R., Bombardier C.H., Vannoy S., Dyer J., Ludman E., Dikmen S., Marshall K., Barber J., Temkin N. Telephone and in-person cognitive behavioral therapy for major depression after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. J. Neurotrauma. 2015;321:45–57. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T.A., Horikoshim M., Kawakamim N., Kadota M., Sasaki M., Sekiya Y. Telephone cognitive-behavioral therapy for subthreshold depression and presenteeism in workplace: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly J., Pedley R., Molloy C., Butler J., Lovell K., Bee P. Low intensity interventions for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder OCD: a qualitative study of mental health practitioner experiences. BMC Psych. 2017;1777 doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1238-x. 10.1186%2Fs12888-017-1238-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumet G.W. Telephone Therapy: A Review and Case Report. Am. J. Orthopsych. 1979;494:574–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1979.tb02643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas L.J., Benedict J.G., Kobos J.C. Psychotherapy by telephone: risks and benefits for psychologists and consumers. Profess. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1996;272:154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G.C., Croudace T.J., Radhakrishnan M., Lafortune L., Watson A., McMillan-Shields F., Jones P.B. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive therapies delivered face-to-face or over the telephone: an observational study using propensity methods. PLoS One. 2012;79:e42916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haregu T.N., Chimeddamba O., Islam M.R. Effectiveness of telephone-based therapy in the management of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SM J. Depress. Res. Treatment. 2015;1:1006. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Social Care Information Centre HSCIC Psychological therapies: Annual report on the use of IAPT Services 2013/14. Experimental statistics. 2014 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/psychological-therapies-annual-reports-on-the-use-of-iapt-services/annual-report-2013-14 accessed 19 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J., Maynard D., editors. Communication in Medical Care. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J., Robinson J. The structure of patients’ presenting concerns: physicians’ opening questions. Health Commun. 2006;19:89–102. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J., Elliott M.N., Stivers T., Richardson A., Mangione-Smith R. Reducing inappropriate antibiotics prescribing: The role of online commentary on physical examination findings. Patient Edu. Counsel. 2010;81:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J., Robinson J.D., Elliott M., Beckett M., Wilkes M. Reducing patients' unmet concerns: The difference one word can make. J. General Int. Med. 2007;22:1429–1433. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty D.M., Ferrer D.C., Parish M.B., Johnston B., Callahan E.J., Yellowlees P.M. The effectiveness of telemental health: A 2013 review. Telemed. J. e-Health. 2013;196:444–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelhoch S., Medoff D., Maxfield J., Dihmes S., Dixon L., Robinson C., Mohr D.C. Telephone based cognitive behavioral therapy targeting major depression among urban dwelling, low income people living with HIV/AIDS: Results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2756–2764. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0465-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen J.J., Zwibelman B.B. Differences between telephone and in-person peer counseling. J. College Student Personnel. 1981;224:315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A., Greenberg L. Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. J. Counsel. Psychol. 1989;362:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Janofsky A.I. Affective self-disclosure in telephone versus face to face interviews. J. Human. Psychol. 1970;10:93–103. 10.1177%2F002216787101100110. [Google Scholar]

- Jones E.A., Bale H.L., Morera T. A qualitative study of clinicians’ experiences and attitudes towards telephone triage mental health assessments. Cogn. Behav. Therap. 2013;6:e17. [Google Scholar]

- Jones D., Drew P., Elsey C., Blackburn D., Wakefield S., Harkness K., Reuber M. Conversational assessment in memory clinic encounters: interactional profiling for differentiating dementia from functional memory disorders. Aging Mental Health. 2016;205:500–509. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1021753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koons C.R. The role of the team in managing telephone consultation in dialectal behavior therapy: three case examples. Cognit. Behav. Pract. 2011;18:168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Langarizadeh M., Tabatabaei M.S., Tavakol K., Naghipour M., Rostami A., Moghbeli F. Telemental Health Care, an Effective Alternative to Conventional Mental Care: a Systematic Review. Acta Informat. Med. 2017;254:240–246. doi: 10.5455/aim.2017.25.240-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach L.S., Christensen H. A systematic review of telephone-based interventions for mental disorders. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2006;123:122–129. doi: 10.1258/135763306776738558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffert M. Analysis and Psychotherapy by Telephone: Twenty Years of Clinical Experience. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 2003;51:101–130. doi: 10.1177/00030651030510011301. 10.1177%2F00030651030510011301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester D. The Use of the Telephone in Counseling and Crisis Intervention. In: de Sola Pool I., editor. The Social Impact of the Telephone. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1977. pp. 454–472. [Google Scholar]

- Lester D., Rogers J.R., editors. Crisis Intervention and Counseling by Telephone and the Internet. 3rd ed. Charles C Thomas Publishers; Springfield, IL: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lingley-Pottie P., McGrath P.J. Distance therapeutic alliance: the participant's experience. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2007;30:353–366. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000300184.94595.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell K., Cox D., Haddock G., Jones C., Raines D., Garvey R., Roberts C., Hadley S. Telephone administered cognitive behaviour therapy for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2006;2006(333):883. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38940.355602.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.B. The telephone in outpatient psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychother. 1973;271:15–26. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1973.27.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Shekelle P., Stewart L.A., Group PRISMA-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols PRISMA-P 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015;41:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D.C., Ho J., Duffecy J., Reifler D., Sokol L., Burns M.N., Jin L., Siddique J. Effect of telephone-administered vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients. Random. Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2012;30721:2278–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D.C., Likosky W., Bertagnolli A., Goodkin D.E., Van Der Wende J., Dwyer P., Dick L.P. Telephone-administered cognitive–behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:356–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D.C., Vella L., Hart S., Heckman T., Simon G. The effect of telephone-administered psychotherapy on symptoms of depression and attrition: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. 2008;153:243–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00134.x. 10.1111%2Fj.1468-2850.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan J., Haddock G., Hartley S., Davies J., Sharp T., Kelly J., Neil S.T., Taylor C.D., Welford M., Price J., Rivers Z., Barrowclough C. An exploration of the therapeutic alliance within a telephone-based cognitive behaviour therapy for individuals with experience of psychosis. Psychol. Psychoth. Theory, Res. Pract. 2014;874:393–410. doi: 10.1111/papt.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2009. Depression in adults: recognition and management. NICE, London. [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2011. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management. NICE, London. [PubMed]

- Oliveira P.N., Rizvi S.L. Phone coaching in Dialectal Behavior Therapy: frequency and relationship to client variables. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47:383–396. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1437469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne L., Casemore R., Neat P., Chambers M. British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy; London: 2006. Guidelines for telephone counselling and psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- Perakyla A., Antaki C., Vehvilainen S., Leuder I. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2008. Conversation Analysis and Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- Reese R.J., Conoley C.W., Brossart D.F. Effectiveness of telephone counseling: A field-based investigation. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2002;492:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves N. The use of telephone and skype in psychotherapy. In: Cundy L., editor. Love in the Age of the Internet: Attachment in the Digital Era. Karnac Books; London: 2015. pp. 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Richards D., Whyte M. Rethink Mental Illness and National Mental Health Development Unit, London. 3rd ed. 2011. Reach out. national Programme student materials to support the delivery of training for psychological wellbeing practitioners delivering low intensity interventions. [Google Scholar]

- Richards D.A., Lankshear A.J., Fletcher J., Rogers A., Barkham M., Bower P., Gask L., Gilbody S., Lovell K. Developing a U.K. protocol for collaborative care: A qualitative study. Gen. Hosp. Psych. 2006;284:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. An interactional structure of medical activities during acute visits and its implications for patients’ participation. Health Commun. 2003;15:27–59. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1501_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J., Heritage J. Physicians’ opening questions and patients’ satisfaction. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006;60:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson C., Drew P., Reuber M. Duration and structure of unaccompanied (dyadic) and accompanied (triadic) initial outpatient consultations in a specialist seizure clinic. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield M. A Handbook for Practitioners. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2013. Telephone Counselling. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield M. Sage Publications; London: 1997. Counselling by Telephone. [Google Scholar]

- Safran J.D., Crocker P., McMain S., Murray P. Therapeutic alliance rupture as a therapy event for empirical investigation. Psychotherapy. 1990;27:154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger K., Pisoni S. Reinforcement of affect responses of schizophrenics during the clinical interview. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1958;571:84–90. doi: 10.1037/h0040304. https://psycnet.apa.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]