To the Editor:

Few ICU staffing studies examine connections among clinicians. Examining how nurses are connected in a network and their potential to receive and share information may inform actionable staffing interventions. The most common way to assess connections among clinicians via a network analysis is to determine which clinicians share patients (1) and measure the coreness and betweenness of these connections (2). “Coreness” is the degree to which a network is represented by a densely interconnected core versus a less-connected periphery (3). Nurses in the core may be more effective working together as a team as a result of increased interactions. Indeed, a previous study found that the presence of more core individuals in the operating room (meaning that the team worked together more often) was significantly associated with shorter cases (2). “Betweenness” refers to whether a nurse lies on the path of others who are not directly connected. For example, a nurse with a broad skill set who is caring for a wide spectrum of patients could frequently occupy a high-betweenness position, connecting other skill-based nurses (e.g., nurses trained in continuous renal replacement therapy or aortic balloon pumps), and betweenness could also occur randomly owing to scheduling. A high-betweenness nurse is likely to have a more diverse set of information about evidence-based practice and have the ability to receive and disseminate useful information from a wide range of sources (4, 5). Although coreness and betweenness are often related, coreness has implications for efficient coordination of patient care, whereas betweenness reflects access to diverse communication channels about evidence-based practice. Using these measures, we examined whether patients who were cared for by more core and high-betweenness nurses had different odds of death and ICU readmission.

Some of the results of this study were previously reported in the form of an abstract (6).

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of linked nurse–patient electronic health record (EHR) and administrative data from one medical center. Our sample included adult patients (≥18 yr old) who had been hospitalized in the neurosurgical ICU (NICU) or surgical ICU (SICU) and admitted to a medical/surgical floor during their hospitalization in 2011, and nurses who worked in the NICU or SICU during the same time period. We created networks by identifying ties among nurses who provided direct care for the same patient during the ICU stay (i.e., each nurse entered assessment information in the patient’s EHR).

For primary exposures, we calculated coreness and betweenness for each nurse. Using UCINet, a network analysis software, we calculated coreness using the k-core measure and classified each nurse as in the core (or not) (2) using the recommended UCINet core size (3, 7). We calculated betweenness (4) and classified each nurse as high or low betweenness based on the median betweenness in our sample (11.6 for NICU and 11.9 for SICU). For each patient, we quantified the number of nurses, core nurses, and high-betweenness nurses who cared for that patient during his or her ICU stay.

Our primary outcome was in-hospital death (from the patient’s EHR). We included a secondary outcome of ICU readmission before hospital discharge. The reference category was hospital discharge without ICU readmission.

We used descriptive statistics to describe our sample and multinomial logistic regressions to obtain the relative odds of death and ICU readmission on the number of core and high-betweenness nurses during a patient’s stay, adjusting for a priori nurse and patient characteristics (Table 1), length of ICU stay, and unit fixed effects.

Table 1.

Critical Care Nursing, Patient Characteristics, and Multinomial Logistic Regression Results

| Nurse characteristics (n = 281) | |

| Primary exposures | |

| Betweenness centrality, mean (SD) | 42.7 (60.4) |

| Number of nurses in the core (%) | 155 (55) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.6 (10.5) |

| Sex, M, n (%) | 34 (15) |

| Years of work experience, mean (SD) | 6.3 (7.5) |

| Degree, n (%) | |

| Diploma | 21 (10) |

| Associate | 35 (17) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 156 (74) |

| Expertise, n (%)* | |

| Clinical nurse 1 | 52 (22) |

| Clinical nurse 2 | 124 (53) |

| Clinical nurse 3 | 45 (19) |

| Clinical nurse 4 | 6 (3) |

| Part-time, n (%) | 115 (42) |

| | |

| Patient characteristics (n = 598†) | |

| Outcomes, n (%) | |

| In-hospital mortality (primary) | 30 (5) |

| ICU readmission (secondary) | 27 (4) |

| Discharge without ICU readmission (reference) | 551 (91) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.4 (18.1) |

| Sex, M, n (%) | 327 (54) |

| ICU length of stay, d, mean (SD) | 4.7 (6.8) |

| Number of ICU stays per visit, n (%) | |

| 1 | 573 (94) |

| ≥2 | 35 (6) |

| Number of nurses per ICU stay, mean (SD) | 6.8 (6.6) |

| Primary diagnoses using HCUP CCS, n (%) | |

| General | 168 (28) |

| Oncology | 89 (15) |

| Neurological | 230 (39) |

| Trauma | 73 (12) |

| Liver disease | 13 (2) |

| Pulmonary | 6 (1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 18 (3) |

| | |

| Multinomial logistic regressions modeling the relationships between coreness and betweenness and death/ICU readmission‡ after adjusting for nurse and patient characteristics§, OR (95% CI), P value |

|

| Number of core nurses involved in patient care | |

| ICU readmission | 0.94 (0.74–1.19), P = 0.591 |

| In-hospital mortality | 0.78 (0.62–0.97), P = 0.029 |

| Number of high-betweenness‖ nurses involved in patient care | |

| ICU readmission | 0.94 (0.73–1.20), P = 0.604 |

| In-hospital mortality | 0.79 (0.62–0.99), P = 0.049 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HCUP CCS = Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classifications Software; OR = odds ratio.

Expertise was measured using the clinical nurse ladder, a formalized approach to facilitate nursing career progression by defining levels of practice and expertise. “Clinical nurse 4” refers to an expert nurse, whereas “clinical nurse 1” refers to a novice nurse.

Our patient sample included 598 patients but across 608 hospitalizations.

Death/ICU readmission was the outcome variable. Discharged home/alive without an ICU readmission was the reference category.

Adjusted for nurses’ years of experience, age, clinical expertise, part-time status, and degree; indicator for neurosurgical ICU; and patient characteristics (age, sex, and primary diagnosis using the HCUP CCS); length of ICU stay; and unit fixed effects.

We calculated betweenness by classifying each nurse as high or low betweenness based on the median betweenness in our sample (11.6 for neurosurgical ICU and 11.9 for surgical ICU). We then calculated the number of high-betweenness nurses involved in each patient’s ICU stay.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Yale New Haven Medical Center (HIC1201009585) and the University of Michigan (HUM00113561).

Results

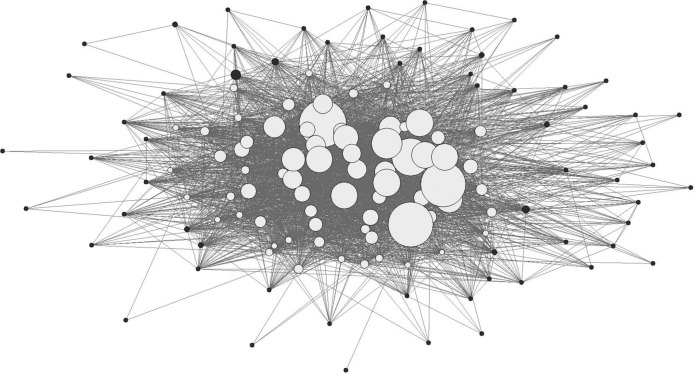

Our sample included 598 patients and 281 nurses (Table 1). In an adjusted multinomial logistic regression (Table 1), we found that ICU patients who were cared for by one additional core nurse had significantly lower odds of in-hospital death (odds ratio [OR], 0.78 [95% confidence interval, 0.62–0.97]). Similarly, ICU patients who were cared for by one additional high-betweenness nurse had significantly lower odds of death (OR, 0.79 [95% confidence interval, 0.62–0.99]). ORs for the secondary outcome of ICU readmission were nonsignificant. A sociogram of the NICU (a visual representation of coreness and betweenness in the network) is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sociogram of the neurosurgical ICU nursing network. The size of the nodes corresponds to individual nurses’ betweenness scores. White nodes correspond to nodes in the core and black nodes correspond to nodes in the periphery.

Discussion

In our sample of two ICUs, patients who were cared for by more core and high-betweenness nurses were less likely to die, and these results held after we controlled for nurse and patient characteristics. We did not find differences in the odds of ICU readmission, which may be attributable to ICU readmission and mortality being poorly correlated (8) or to confounding from factors outside of ICUs (9).

Considering how nurses are embedded in the network, and the potential effects of this network on patients, may have significant implications with regard to staffing. Aside from recent legislation regarding public reporting of ICU nurse staffing (10), there are no universal guidelines. An examination of coreness and betweenness could inform strategic ICU staffing decisions by identifying core nurses who might work together effectively and/or high-betweenness nurses with access to information about evidence-based care to benefit patients.

Our study has limitations. Because of the limited severity-of-illness adjustment, unmeasured confounding is a potential limitation. This was a single-center study in a large tertiary academic medical center, and therefore generalizability may be limited. Because this was a secondary analysis study, our sample was limited to ICU patients who also had a medical/surgical stay during the same hospitalization; therefore, our results might be subject to selection bias. To construct the networks, we used a simple and frequently used approach (1) based on whether two nurses shared a patient, without accounting for the number of times nurses shared a patient. Furthermore, our measures quantified the number of core and high-betweenness nurses during a patient’s ICU stay and did not account for the number or timing of shifts (early vs. late in the hospitalization) by each type of nurse. How our results might change if more-nuanced measures were used should be explored in future studies.

In the first study to examine nurse networks in adult ICUs, we found that patients who were cared for by more core and high-betweenness nurses were significantly less likely to die. Our results are hypothesis generating, and future work should examine the position of ICU nurses in a network as a possible mechanism to improve outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS024552 to D.K.C.).

Author Contributions: D.K.C. and O.Y. conceptualized the study. D.K.C., H.L., E.M.B., and O.Y. contributed to analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and approval of the final manuscript. O.Y. contributed to data acquisition and analysis and supervision of the study.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0543LE on October 18, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Landon BE, Keating NL, Onnela J-P, Zaslavsky AM, Christakis NA, O’Malley AJ. Patient-sharing networks of physicians and health care utilization and spending among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;138:288–298. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson C, Talsma A. Characterizing the structure of operating room staffing using social network analysis. Nurs Res. 2011;60:378–385. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182337d97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgatti SP, Everett MG. Models of core/periphery structures. Soc Networks. 2000;21:375–395. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc Networks. 1978;1:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tasselli S. Social networks and inter-professional knowledge transfer: the case of healthcare professionals. Organ Stud. 2015;36:841–872. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa DK, Liu H, Boltey EM, Yakusheva O. The structure of critical care nursing teams and patient outcomes: a network analysis [unpublished abstract] Presented at the AcademyHealth’s Annual Research Meeting. June 25, 2017, New Orleans, LA.

- 7.Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies; 2002. UCINet for Windows: software for social network analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maharaj R, Terblanche M, Vlachos S. The utility of ICU readmission as a quality indicator and the effect of selection. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:749–756. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SE, Ratcliffe SJ, Kahn JM, Halpern SD. The epidemiology of intensive care unit readmissions in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:955–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1720OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law AC, Stevens JP, Hohmann S, Walkey AJ. Patient outcomes after the introduction of statewide ICU nurse staffing regulations. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1563–1569. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.