Abstract

Riboswitches are a class of nonprotein-coding RNAs that directly sense cellular metabolites to regulate gene expression. They are model systems for analyzing RNA-ligand interactions and are established targets for antibacterial agents. Many studies have analyzed the ligand-binding properties of riboswitches, but this work has outpaced our understanding of the underlying chemical pathways that govern riboswitch-controlled gene expression. To address this knowledge gap, we prepared 15 mutants of the preQ1-II riboswitch—a structurally and biochemically well-characterized HLout pseudoknot that recognizes the metabolite prequeuosine1 (preQ1). The mutants span the preQ1-binding pocket through the adjoining Shine–Dalgarno sequence (SDS) and include A-minor motifs, pseudoknot-insertion helix P4, U·A-U base triples, and canonical G-C pairs in the anti-SDS. As predicted—and confirmed by in vitro isothermal titration calorimetry measurements—specific mutations ablated preQ1 binding, but most aberrant binding effects were corrected by compensatory mutations. In contrast, functional analysis in live bacteria using a riboswitch-controlled GFPuv-reporter assay revealed that each mutant had a deleterious effect on gene regulation, even when compensatory changes were included. Our results indicate that effector binding can be uncoupled from gene regulation. We attribute loss of function to defects in a chemical interaction network that links effector binding to distal regions of the fold that support the gene-off RNA conformation. Our findings differentiate effector binding from biological function, which has ramifications for riboswitch characterization. Our results are considered in the context of synthetic ligands and drugs that bind tightly to riboswitches without eliciting a biological response.

Keywords: RNA structure, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), gene expression, bacteria, mutant, A-minor motif, base triples, pseudoknot, riboswitch, Shine-Dalgarno sequence, gene regulation, preQ1 riboswitch

Introduction

Riboswitches are found mostly in the 5′-leader sequences of bacterial mRNAs, where they regulate the expression of a downstream ORF or operon (1–3). An extraordinary aspect of these functional RNAs is their ability to specifically bind a cognate cellular or environmental effector with high affinity and specificity (4–6). Such ligands are often products of a downstream metabolic pathway or imported by a transporter that is encoded by an mRNA, regulated by the riboswitch. To achieve gene-regulatory feedback, riboswitches comprise two functional regions. Aptamers are conserved domains that use complex three-dimensional folds to recognize an effector (7, 8). The cognate molecular recognition event elicits a structural change in a linked expression platform that exposes or sequesters regulatory sequences, such as those required for translation initiation or transcription termination (9). Recognition of key molecules that control essential genes makes riboswitches ideal candidates for drug development (10–18).

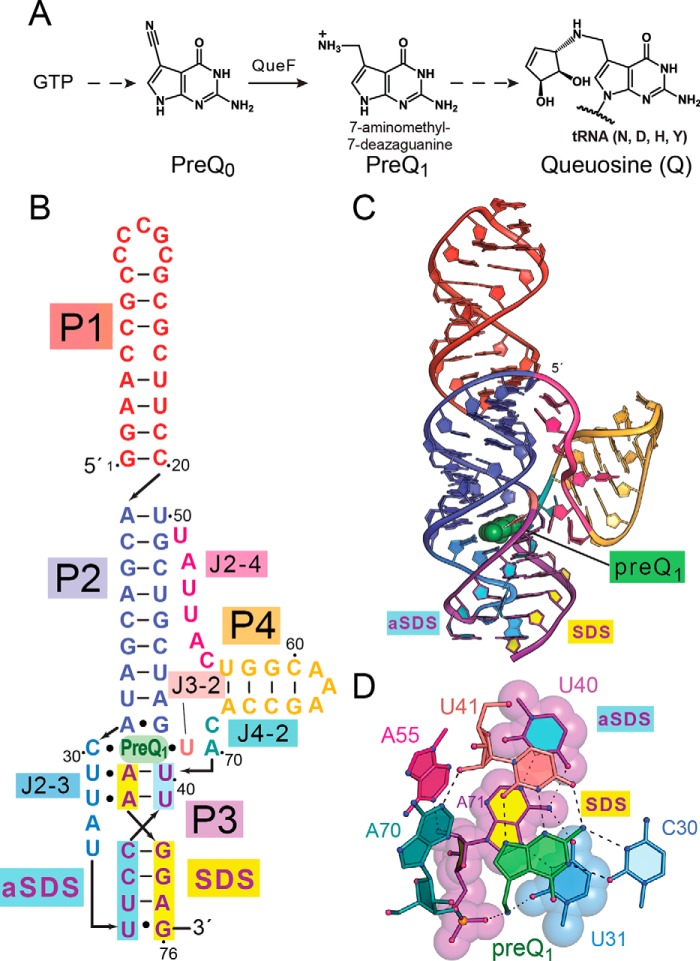

The clan of preQ12 riboswitches comprises three main classes that each bind the secondary metabolite preQ1 (19–21). This pyrrolopyrimidine (7-aminomethyl-7-deazaguanine) is the last free precursor in the queuosine (Q) biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1A) (22, 23). The class II preQ1 riboswitch (preQ1-II) was discovered initially during bioinformatic analysis (24) with subsequent validation as a second riboswitch scaffold that senses preQ1 (21, 25). The riboswitch is found exclusively in the 5′-UTRs of genes encoding queT, a bacterial transporter that appears to salvage preQ0 or preQ1 from the environment (26). The structure, dynamics, and effector binding properties have been investigated for representative preQ1-II riboswitches from Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Lrh) (21, 25, 27–30). The overall fold of the riboswitch is an HLout pseudoknot comprising four helical pairing regions, P1–P4, connected by junction (J) regions (Fig. 1B). The P1, P2, and P3 helices form a continuous coaxial stack, with helix P4 arranged at a right-angle (Fig. 1, B and C). The preQ1 recognition pocket is located at the base of the three-helix junction. The crystal structure of the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch provided a detailed view of preQ1 binding that was confirmed by NMR (25, 27). PreQ1 is recognized by a trans base pair with C30 that engages the ligand in a pseudo-base triple with U41 (Fig. 1D). The floor of the pocket comprises additional base-triple layers at U31·A71-U40 and U32·A72-U39 (Fig. 1, B–D). A71 and A72 represent the first two bases of the Shine–Dalgarno sequence (SDS) 5′-AAGGAG-3′. This purine-rich translation-initiation signal pairs with an anti-SDS (aSDS) to form helix P3 (Fig. 1, B and C). Inclined A-minor adenines, A70 and A55, form one side of the preQ1 pocket that provides a structural transition to helix P4 (Fig. 1, B–D). A number of complementary in vitro biochemical and biophysical studies have been conducted on the Spn preQ1-II riboswitch. Mutagenesis of the two A-minor adenines revealed that each plays an important role in stabilizing and sequestering preQ1 in the binding pocket (27). Disruption of P4 base-pairing at the top of the helix weakened preQ1 binding (21), but deletion of the entire P4 stem-loop suggested that it was not essential for preQ1 binding. Importantly, P4 was reported to influence effector binding by altering the rate at which the aptamer domain interacts with preQ1 while stabilizing the binding pocket (28).

Figure 1.

Queuosine (Q) biosynthesis, secondary structure, and tertiary fold of the preQ1-II riboswitch from Lrh. A, Q is a hypermodified base synthesized by bacteria to confer wobbling. The pathway starts from GTP and proceeds via multiple steps (broken arrow) that lead to preQ0. A nitrile reductase encoded by the queF gene generates preQ1, the last soluble metabolite prior to its insertion by transglycosylation at GUN anticodons specifying Tyr, Asn, Asp, or His. Additional modifications are added in situ (broken arrow) (22) to form queuosine. B, secondary structure of the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch WT sequence based on the crystal structure (25). PreQ1 is green; various pairing regions (P) are color-coded, with canonical and noncanonical pairs indicated by lines or filled circles; Junctions are labeled J. The SDS (expression platform) is highlighted in yellow; the opposing complementary aSDS is highlighted in cyan. C, ribbon diagram depicting the global HLout pseudoknot fold based on the Lrh co-crystal structure (Protein Data Bank entry 4JF2). The P3 helix comprises SDS-aSDS canonical pairing (rings filled yellow and cyan, here and elsewhere), which is considered the gene-off conformation of the expression platform. PreQ1 is drawn as a green CPK model. D, close-up view of the preQ1-binding pocket drawn as a ball-and-stick diagram. The effector is recognized by hydrogen bonds to C30 and U41. A-minor bases A70 and A55 stack against the pyrrole ring of preQ1, whereas its methylamine hydrogen bonds to the keto group of U31 and a nonbridging oxygen of A71—the first nucleotide of the SDS. The pocket floor comprises the base-triple U31·A71-U40 (semi-transparent surface model), wherein U31 interacts with the major-groove edge of the A-U bp.

Beyond effector recognition, a major goal in the riboswitch field has been the development of approaches that interrogate effector binding in the context of the downstream expression platform to discern structure-function relationships (31–35). In this respect, a knowledge gap exists in terms of how effector sensing is communicated through space to distal regulatory sequences. A major advance has been the development of cell-based systems wherein a structurally characterized riboswitch is used to control a downstream reporter gene in a manner that depends on the addition of the exogenous effector. Such assays have been implemented with great success using a GFPuv-reporter gene to dissect cobalamin riboswitches in Escherichia coli (36–39). Using a similar approach, the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch was used to control GFP expression in Mycobacterium, which does not possess queF genes required for preQ1 biosynthesis (Fig. 1A) (40). Considering the breadth of in vitro work on the preQ1-II riboswitch (21, 25, 27–30) and the success of GFP-reporter systems for its functional analysis, we adapted the E. coli–based reporter assay to couple Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch regulation with GFPuv fluorescence, accompanied by orthogonal analysis of gene-regulatory conformations using in-cell chemical modification (41). Our results revealed that the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch co-crystal structure in complex with preQ1 agrees well with expectations for its gene-off conformational state in live bacteria. We further established that our method of folding the Lrh riboswitch for co-crystallization and binding analysis produces no appreciable difference in equilibrium binding to preQ1 when compared with experiments in which the riboswitch was prepared by co-transcriptional folding and native purification (41).

Here we combine the complementary approaches of equilibrium binding by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) with in-cell functional analysis, wherein GFPuv expression is controlled by the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch in E. coli. Altogether, 15 mutants were analyzed to investigate elements identified previously for their roles in effector recognition and dynamics based on biochemical, biophysical, and structural studies. Specific regions selected for analysis included: (i) inclined A-minor bases, (ii) helix P4 of the pseudoknot, (iii) major-groove base triples in the SDS-aSDS interface, and (iv) base pairing in the helix P3 SDS-aSDS interface (Fig. 1, B–D). Our results revealed that most mutants that disrupted preQ1 binding in vitro could be rescued by compensatory changes. However, all mutations showed impaired gene regulation in bacteria, suggesting uncoupling of effector-binding from expression control. The results are considered in light of the underlying chemical pathways that link the preQ1-binding pocket to the SDS-aSDS expression platform. This work has broader implications for understanding the structure-function relationships of ncRNAs.

Results

Quality control analysis of the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch

To benchmark riboswitch quality prior to the ensuing analysis, we showed that the WT Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch has strong heats of binding to preQ1 in an enthalpically driven process (ΔH = −35.6 kcal mol−1, −TΔS = +24.1 kcal mol−1, Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S1) that yielded a KD of 2.7 nm (Table 1). The WT Lrh riboswitch remained intact after Mg2+-dependent folding at 65 °C (Fig. S3A) and showed distinct CD features in the presence of Mg2+ that were absent when Mg2+ was excluded from the buffer (Fig. S3B). A dependence on Mg2+ for Lrh riboswitch folding was observed in prior smFRET analysis (30). Mixed low- and high-FRET states were present in the population when Mg2+ was absent, but these could be shifted to a uniform high-FRET state with added Mg2+. Accordingly, CD spectroscopy was used herein to assess the folding of representative riboswitch mutants based on comparison with the WT spectrum. This approach was used because computational methods cannot always predict pseudoknot folds (42), such as that of the preQ1-II riboswitch. A comparison of CD spectra revealed that all tested classes of Lrh riboswitch mutants folded similarly to WT in the presence of Mg2+, except C37G/C38G (described below).

Table 1.

-Fold changes in preQ1 binding and gene repression with S.E. values

| Sample | KD | Krela | Gene-off EC50 | EC50 -fold change | -Fold repression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | nm | -fold | -fold | ||

| Structure category: WT Lrh PreQ1-II riboswitch | |||||

| WT | 2.7 ± 0.1 | NAb | 19.5 ± 1.1 | ΝΑ | 11.8 ± 0.3 |

| Structure category: inclined A-minor motifs in binding pocket | |||||

| Δ70 | 246 ± 7 | 93 ± 5 | 148,777 ± 1 | 7,630 ± 423 | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

| A70G | 518 ± 18 | 195 ± 12 | 181,481 ± 1 | 9,307 ± 515 | 3.3 ± 0.04 |

| A70C | 163 ± 6 | 61 ± 4 | 140,307 ± 1 | 7,195 ± 399 | 4.1 ± 0.02 |

| Δ55 | 153 ± 3 | 57 ± 3 | 23,508 ± 1 | 1,206 ± 67 | 8.1 ± 0.3 |

| A55G | 77 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 | 28,383 ± 1 | 1,456 ± 81 | 14.1 ± 1.2 |

| A55C | 433 ± 14 | 163 ± 10 | 36,066 ± 1 | 1,850 ± 102 | 11.7 ± 1.0 |

| Structure category: P4 helix | |||||

| ΔP4 | 66 ± 3 | 25 ± 2 | 14,849 ± 1 | 761 ± 42 | 12.5 ± 0.4 |

| Structure category: U·A-U major groove triples in binding pocket floor or sub-floor | |||||

| A71G | 3,935 ± 105 | 1,479 ± 82 | 196,675 ± 4 | 10,086 ± 559 | 1.2 ± 0.02 |

| A71G/U31C | 21 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 167,530 ± 1 | 8,591 ± 476 | 2.5 ± 0.04 |

| A72G | 126 ± 4 | 47 ± 3 | 86,361 ± 1 | 4,429 ± 245 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

| A72G/U32C | 62 ± 2 | 23 ± 1 | 196,492 ± 1 | 10,077 ± 558 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| Structure category: aSDS in P3 helix (expression platform) | |||||

| C37G/C38G | 20,300 ± 1,058 | 7,632 ± 545 | NDc | ND | 1.0 ± 0.01 |

| C37U/C38U | 3,055 ± 332 | 1,149 ± 137 | ND | ND | 1.1 ± 0.02 |

| C37U | 24 ± 0.3 | 9 ± 1 | 16,598 ± 1 | 851 ± 47 | 8.4 ± 0.3 |

| C38U | 36 ± 5 | 14 ± 2 | 31,632 ± 1 | 1,622 ± 90 | 7.3 ± 0.1 |

a Krel equals apparent KD of mutant divided by the apparent KD of WT.

b NA, not applicable.

c ND, not detected.

Inclined A-minor bases are more important for gene regulation than preQ1 binding

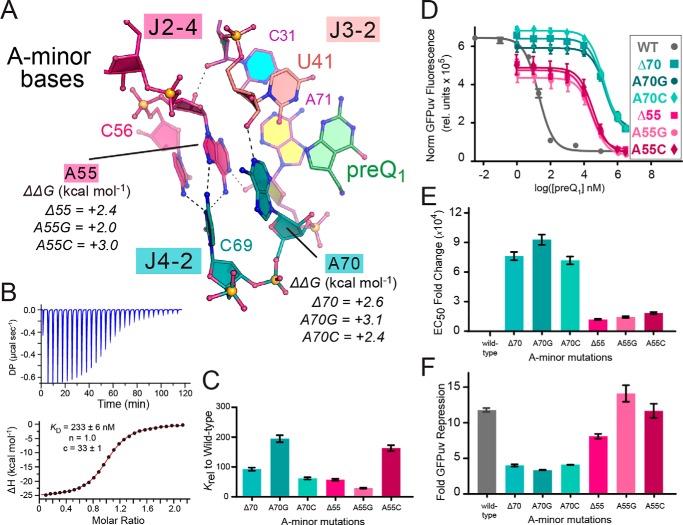

A main objective of our work was to understand how specific mutations that influence preQ1-binding by the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch affect gene-regulatory function. As a starting point, we chose to interrogate the inclined A-minor adenines due to their proximity to preQ1 in the binding pocket (see Fig. 2A). A70 interacts directly with preQ1 via a T-shaped stacking interaction while also interacting with the sugar edge of a pseudo-base triple comprising C30·preQ1·U41 (Fig. 1D) (25). For comparison, we prepared and analyzed three distinct A70 mutants. The first change, Δ70, was a deletion designed to disrupt the binding pocket. We considered the possibility that nearby A-minor base A55 would occupy this void—or possibly underlying base C69. A second mutant, A70G, was designed to disrupt the hydrogen-bonding and van der Waals interactions with the pseudo-base triple, resulting from poor isostericity and reversal of hydrogen bond acceptor and donor groups on the A70G Watson–Crick face. This mutation was analyzed previously for the Spn riboswitch (27), where it resulted in a 280-fold loss of preQ1 binding affinity. A third A70C mutation was chosen with the rationale that a small pyrimidine ring would be accommodated near the binding pocket better than guanine, while maintaining an imine hydrogen bond acceptor like adenine to support local folding interactions.

Figure 2.

Inclined A-minor base interactions abutting the effector-binding pocket and mutational effects on preQ1 binding and reporter-gene switching. A, close-up ball-and-stick diagram of A-minor bases A70 and A55 making cross-strand interactions to U41, C69, and A71. ΔΔG values for various mutants are provided from ITC (Table S1). Dashed lines, putative hydrogen bonds. B, representative ITC thermogram and fit to a single-site binding model for the Δ70 mutant. Here and elsewhere, the KD, binding stoichiometry (n), and c-value are provided. Errors in KD are standard error-of-fit, whereas c-value errors were calculated from errors-of-fit of cell concentration and KD; average KD values are reported in Table 1 and Table S1. C, bar graph of Krel values from Table 1 emphasizing changes in KD for preQ1 binding by each A-minor mutant relative to WT. D, PreQ1-dependent dose-response curve of reporter-gene GFPuv fluorescence emission comparing the WT riboswitch with various A-minor mutants. E. coli cells containing the riboswitch reporter gene were grown with varying amounts of preQ1, and fluorescence was measured at each concentration. Curve fits are based on the average of triplicate biological measurements. E, bar graph of the EC50 -fold change of each mutation relative to WT. F, bar graph of GFPuv reporter-gene -fold repression showing the effect of each inclined A-minor mutant compared with WT. Data from B–F are summarized in Table 1. A full comparison of Krel, EC50 -fold change, and -fold GFPuv repression is provided in Fig. S4. Error bars, S.E.

As anticipated, Δ70 showed significant binding to preQ1, as indicated by a KD of 246 nm, which is >90-fold weaker than that of WT (Fig. 2 (B and C) and Table 1). Despite the rather modest +2.6 kcal mol−1 change in the ΔΔG of binding (Fig. 2A), the gene-regulatory function of this mutant was compromised. Although a preQ1-dependent dose response was observed, the riboswitch lost its sensitivity to preQ1, as indicated by an EC50 >7,600-fold higher than WT and a loss of repression capability from 12- to 4-fold (Fig. 2 (D–F) and Table 1). The A70G transition variant showed poorer preQ1 affinity than Δ70 with a KD of 518 kcal mol−1 (ΔΔG of +3.1 kcal mol−1), which was ∼195-fold worse than WT and ∼2-fold higher than Δ70 (Fig. 2 (A and C) and Table 1). The dose-response trend for A70G was similar to Δ70, and the EC50 was >9300-fold poorer than WT, yielding a nominal 3.3-fold repression of GFPuv fluorescence at 3 mm preQ1 (i.e. the highest concentration of effector attainable in culture) (Fig. 2 (D–F) and Table 1). Although the A70C mutant showed improved preQ1 affinity over Δ70 and A70G, its KD of 163 nm was still >60-fold poorer than WT (ΔΔG of +2.4 kcal mol−1) (Fig. 2 (A and C) and Table 1). Moreover, A70C could not rescue effector-mediated gene repression; the EC50 was 7200-fold poorer than WT, and gene repression only reached a level of 4-fold (Fig. 2 (D–F) and Table 1). The collective results suggest that riboswitch mutants retain folding, as indicated by nanomolar levels of preQ1 binding and CD (Table 1 and Fig. S3B). Although the A70 base is important for high-affinity preQ1 binding, it is essential for an efficient gene-regulatory response. This significance was emphasized best by the A-to-C mutation, which conferred a high level of effector binding but was unable to support effective gene-regulatory function.

A second inclined A-minor base at A55 stacks upon A70 and interacts with the U31·A71-U40 base triple in the floor of the binding pocket (Figs. 1D and 2A). Unlike A70, A55 does not interact directly with preQ1 but instead serves as a transition point whereby the three-way helical junction comprising the P2-P3 coaxial stack contacts the P4 helix closing bp (Figs. 1 (C and D) and 2A). To interrogate position 55 and maintain parity, we analyzed the same mutations employed at position 70. Analysis of Δ55 by ITC resulted in a less severe defect than Δ70, indicated by a KD of 153 nm (ΔΔG of +2.4 kcal mol−1)—a 57-fold loss of preQ1 affinity over WT (Fig. 2 (A and C) and Table 1). Although the Δ55 variant showed a dose-dependent response to preQ1 in terms of GPFuv fluorescence (Fig. 2D), switching was still impaired, as indicated by an EC50 >1200-fold higher than WT (Fig. 2E and Table 1). Notably, the EC50 was not as impaired as mutations at position 70 (Fig. 2E), and Δ55 showed an 8-fold level of gene repression that was nearly on par with WT and substantially improved compared with A70 mutants (Fig. 2F). In contrast, the A55G mutant produced a KD of 77 nm (ΔΔG of +2.0 kcal mol−1)—only 29-fold higher than WT (Fig. 2 (A and C) and Table 1), which was similar to the equivalent mutant tested in the context of the Spn preQ1-II riboswitch (27). Unexpectedly, A55C showed the poorest preQ1 binding with a KD of 433 nm (ΔΔG of +3.0 kcal mol−1), which is >160-fold weaker than WT but comparable with the most severe A-minor mutant tested, A70G (Fig. 2 (A and C) and Table 1). In terms of gene-regulatory function, A55C was comparable with other A55 mutants, with an EC50 >1800-fold poorer than WT (Fig. 2, D and E). In total, A55 mutations did not prove as detrimental to EC50 as those at A70 (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, both A55G and A55C showed WT levels of gene repression (Fig. 2F). Although we cannot pinpoint the underlying basis for this similarity, our results provide new insight into the role and requirement for A-minor bases, which calls for an update of the existing preQ1-II riboswitch consensus model (discussed below).

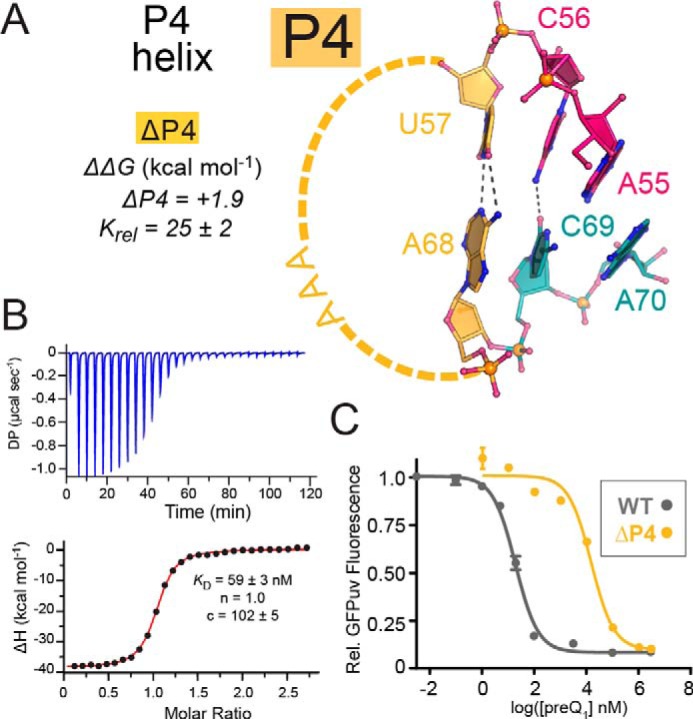

Short P4 helix length supports effector binding but leads to inefficient gene regulation

We next evaluated the role of helix P4, which contacts the binding pocket via inclined A-minor bases A55 and A70 (Fig. 1, B and C). P4 was investigated previously in terms of riboswitch dynamics and binding (27, 28). Deleting the entire P4 stem-loop in the context of the Spn riboswitch and replacing it with a single G caused an ∼10-fold loss of preQ1 affinity (28). In contrast, deleting helix P4 along with the two flanking nucleotides at the base of the helix (i.e. within J4-2 and J2-4; Fig. 1B) resulted in a 20-fold decrease in effector binding (27). The consensus model of the preQ1-II riboswitch shows that whereas the length of helix P4 is variable, most sequences comprise a stem that is 4 bp or longer (21). Of these, the base pair closest to the junction is least conserved, whereas distal pairs show higher conservation, including a central G-C. As such, we truncated P4 to a single U-A pair flanking the A-minor bases A55 and A70 (Fig. 3A). In total, three G-C bp were deleted, and the apical loop was closed by the sequence AAA present in the WT—designated here as ΔP4.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram depicting truncation of the P4 helix and mutational effects on preQ1 binding and reporter-gene switching. A, close-up ball-and-stick view of the truncated P4 stem (ΔP4) capped by the WT AAA-loop and comprising a single U57-A68 canonical pair that abuts a noncanonical C56·C69 interaction and flanking A-minor bases A55 and A70. Three canonical G-C pairs were deleted. ΔΔG is provided from ITC (Table S1). B, representative ITC thermogram and fit to a single-site binding model for the ΔP4 mutant. C, PreQ1-dependent dose-response curves of reporter-gene GFPuv fluorescence emission, comparing the WT riboswitch with the ΔP4 mutant. E. coli cells containing the riboswitch reporter gene were grown with varying amounts of preQ1, and fluorescence was measured at each concentration. Curve fits are based on the average of triplicate biological measurements. A full comparison of Krel, EC50 -fold change and -fold GFPuv repression is provided in Fig. S4. Error bars, S.E.

The resulting P4 variant exhibited a KD of 66 nm for preQ1 binding—25-fold higher than WT (Fig. 3 (A and B) and Table 1). The small increase in ΔΔG of +1.9 kcal mol−1 agrees with a previous report in which the entire helix was ablated up to the A-minor bases (27). In terms of preQ1-dependent gene regulation, ΔP4 showed a clear dose response to preQ1, but the EC50 was shifted to ∼15 μm or >760-fold higher than WT (Fig. 3C and Table 1). In this respect, ΔP4 exhibited properties similar to nearby inclined A-minor mutant A55G in terms of KD and EC50 (Table 1 and Fig. S4). Like the A55C and A55G, the ΔP4 mutant showed gene repression levels near WT (Table 1 and Fig. S4). When compared with other mutants, ΔP4 exhibited the lowest level of GFPuv fluorescence in the absence of preQ1 (Fig. S5). This suggests that truncation of the P4 helix stabilizes the expression platform in the effector-free state. This interpretation is supported by prior biochemical analyses that noted a stabilization of P3 base pairing when P4 is deleted (27, 28). Similarities between ΔP4 and A55 mutants demonstrate that bases distal to the effector-binding pocket are dispensable for preQ1 binding but are essential for potent gene regulation.

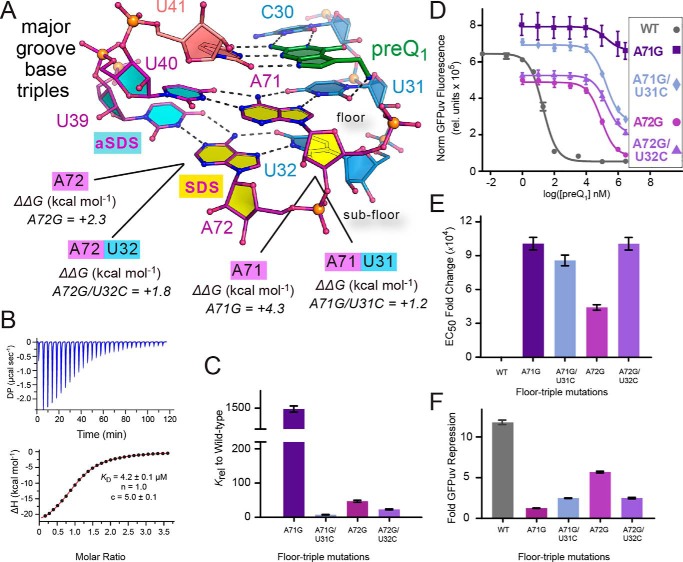

U·A-U triples must interface productively with A-minor motifs to couple preQ1 binding with gene regulation

Two tiers of major-groove base triples compose the floor and sub-floor of the preQ1-binding pocket (Fig. 4A). The triple comprising U31·A71-U40 is located directly beneath preQ1 in the bound-state structure, while simultaneously interacting with inclined A-minor base A55 (Fig. 2A). The central A71 position is also the first base of the Shine–Dalgarno sequence. To investigate the significance of this base triple in preQ1 binding and gene regulation, we generated a series of single and double mutants. We hypothesized that an A71G change would destabilize the binding-pocket floor, despite its apparent compatibility with cross-strand pairing to U40 as a G·U wobble. Specifically, the change was predicted to impair major-groove Hoogsteen readout of G71 by U31 of J2-3. In contrast, we expected that the compensatory mutant, A71G/U31C, would restore Hoogsteen pairing between G71 and C31, as observed in related analyses (43, 44). We expected the resulting C31·G71·U40 base triple would restore some degree of lost function relative to the WT riboswitch, although we recognized the lack of isostericity of the mutant compared with U31·A71-U40 (45).

Figure 4.

Tandem U·A-U major-groove base-triple interactions at the binding-pocket floor and mutational effects on preQ1 binding and reporter-gene switching. A, close-up ball-and-stick diagram of U31·A71-U40 and U32·A72-U39 base triples that form the floor and sub-floor beneath the C30·preQ1·U41 pseudo-base triple. ΔΔG values for various mutants are provided from ITC (Table S1). B, representative ITC thermogram and fit to a single-site binding model for A71G. C, bar graph of Krel values from Table 1 emphasizing changes in KD for preQ1 binding by each floor and sub-floor mutant relative to WT. D, preQ1-dependent dose-response curves of reporter-gene GFPuv fluorescence emission comparing the WT riboswitch with each floor and sub-floor mutant. E. coli cells containing the riboswitch reporter gene were grown with varying amounts of preQ1, and fluorescence was measured at each concentration. Curve fits are based on the average of triplicate biological measurements. E, bar graph of the EC50 -fold change of each mutation relative to WT. F, bar graph of GFPuv-reporter-gene -fold repression showing the effect of each floor and sub-floor mutant compared with WT. Data from B–F are summarized in Table 1. A full comparison of Krel, EC50 -fold change, and -fold GFPuv repression is provided in Fig. S4. Error bars, S.E.

As expected, A71G was affected severely in terms of effector binding as well as the preQ1 dose-response for reporter-gene regulation. The binding affinity was ∼1500-fold poorer than WT with a KD of 3.9 μm, corresponding to a ΔΔG of +4.3 kcal mol−1 (Fig. 4 (A–C) and Table 1). Although impaired, A71G still retains modest effector binding by ITC. However, the mutant has lost most of its ability to repress the reporter gene in response to preQ1, as seen in a shallow dose response corresponding to a 1.2-fold level of preQ1-dependent repression and an EC50 ∼104-fold higher than WT (Fig. 4, D and E). In contrast to ΔP4, cells harboring A71G produced some of the highest GFPuv fluorescence in the absence of preQ1 (Fig. S5), suggesting unfettered ribosomal access to the SDS.

We next analyzed the rescue mutant A71G/U31C, which showed a KD of 20.7 ± 1.2 nm—only ∼8-fold weaker than WT (Fig. 4C and Table 1). Unexpectedly, the EC50 was as high as the A71G mutant but with a slightly greater level of repression (2.5-fold) than A71G (Fig. 4 (D–F) and Table 1). The results demonstrate that the rescue C31·G71·U40 base triple was effective at reconstituting the binding-pocket floor, although gene regulation is impaired. Notably, A71G variation alters a base within the SDS, but levels of GFPuv fluorescence emission in the absence of preQ1 are substantial for A71G (and A72G; see below) (Fig. S5), suggesting that translation initiation is not a factor. Moreover, the A71G mutant still allows G·U pairing between the mutant SDS and 16S rRNA. Perhaps a more plausible explanation for the adverse effects of A71G and A71G/U31C on gene regulation is that the N2 amine of G71 would produce a steric clash with A-minor base A55 and its interface with P4 (Fig. 2A). This clash could conformationally uncouple the effector-binding pocket from the underlying SDS.

To further probe the SDS-aSDS base triples, we prepared a second set of mutants in the sub-floor of the binding pocket at U32·A72-U39 (Fig. 4A). Using a strategy similar to the pocket-floor mutants, we changed A72 to G. This change did not affect preQ1 binding as severely as A71G. The observed KD of 126 nm (ΔΔG of +2.3 kcal mol−1) was only ∼50-fold higher than WT (Fig. 4 (A and C) and Table 1). Similarly, the EC50 and gene repression profile were improved relative to A71G with a steeper preQ1 dose response characterized by a 6-fold range of reporter-gene repression (Fig. 4, D–F).

The double mutant A72G/U32C also showed significant preQ1 affinity (61.7 nm)—twice as tight as A72G but 3-fold weaker than A71G/U31C (i.e. the pocket-floor rescue mutant). More interestingly, A72G/U32C produced a shallow dose-response curve as observed for A71G/U31C (Fig. 4D). Likewise, the EC50 was impaired severely at a level ∼104 weaker than WT and >2-fold higher than A72G (Fig. 4, D–F). Overall, the weak repression properties of A72G/U32C were similar to A71G/U31C and A72G. Like A71G, the A72G variant also affects the minor groove. In the context of the U32·A72-U39 sub-floor triple, a G72 mutation would require wobbling with U39, possibly forcing the 2′-OH of position 72 closer to the 2′-OH of position 56, disrupting base stacking with A55 and P4 (Fig. S6).

When viewed together, the tandem base triples support the concept that major-groove base interactions are needed at the Hoogsteen edges of A71 and A72 to support preQ1 binding. All six bases of the two triples are conserved across the consensus model of the preQ1-II riboswitch with 90–97% nucleotide identity, including a new riboswitch type with a helix inserted into J2-3 (19, 21). Minor-groove readout of the triples is also important, possibly to orient and engage P4 via A70 and A55. Support for this role comes from prior studies in which P4 dynamics plays an integral role in SDS-aSDS stability (28).

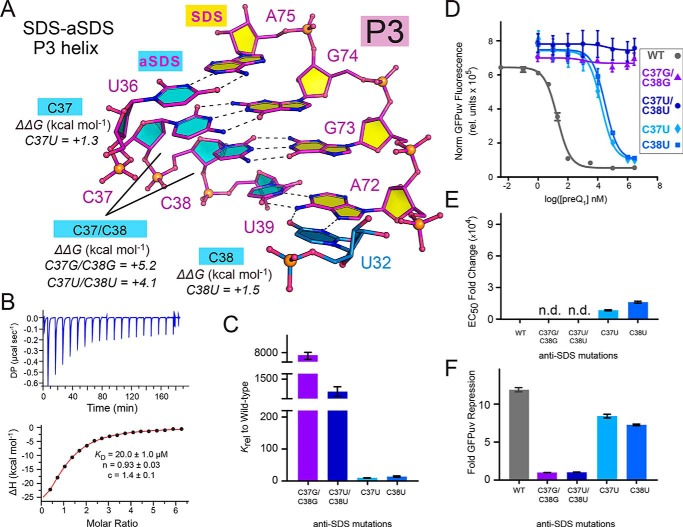

G-C base pairing between the SDS-aSDS helix is essential for expression platform folding

The P3 stem immediately below the sub-floor base triples comprises tandem canonical C-G pairs (Fig. 5A). C37 and C38 form part of the aSDS that attenuates translation by stably pairing to G73 and G74 in the preQ1-bound state. To probe the significance of this base-pairing constellation, we generated four mutations. We first made the C37G/C38G double mutant to abolish the preQ1-dependent dose response by disrupting P3 pairing, freeing the SDS to engage with the ribosome for translation. This appeared likely based on high levels of GFPuv fluorescence emission in the absence of effector (Fig. S5). However, we did not anticipate such a dramatic loss of preQ1 binding by ITC. Indeed, the observed KD was >20 μm (ΔΔG of +5.2 kcal mol−1) or >7,600-fold higher than WT (Fig. 5 (A–C) and Table 1). This change caused the greatest apparent disruption of preQ1 binding, despite its location distal to the effector-binding pocket. Similarly, no significant dose response was detected (Fig. 5D). CD analysis of the C37G/C38G mutant revealed lower absorption at 265 nm (Fig. S3B)—a feature characteristic of dsRNA (46). By comparison, this peak was higher for the WT riboswitch under native folding conditions but reduced under low-folding conditions, wherein Mg2+ was replaced by EDTA. The collective analysis suggests that C37G/C38G disrupts P3 folding, accounting for the substantial losses in effector binding and gene-regulatory function.

Figure 5.

Interactions between base pairs of the SDS expression platform and the aSDS and mutational effects on preQ1 binding and reporter-gene switching. A, close-up ball-and-stick diagram of canonical base pairs between C37-G74 and C38-G73 that compose stem P3 of the pseudoknotted expression platform. The bases are shown in relation to the sub-floor base triple U32·A72-U39. ΔΔG values for various aSDS mutants are provided from ITC (Table S1). B, representative ITC thermogram and fit to a single-site binding model for the C37G/C38G double mutant; due to the low c-value, the KD is considered an estimate of binding (70). Here, the stoichiometry of binding (n) was allowed to vary during curve fitting. C, bar graph of Krel values from Table 1 emphasizing changes in KD for preQ1 binding by each aSDS mutant relative to WT. D, preQ1-dependent dose-response curves of reporter-gene GFPuv fluorescence emission comparing the WT riboswitch with each aSDS mutant. E. coli cells containing the riboswitch reporter gene were grown with varying amounts of preQ1, and fluorescence was measured at each concentration. Curve fits are based on the average of triplicate biological measurements. E, bar graph of the EC50 -fold change of each aSDS mutant relative to WT. n.d., not determined due to the absence of an apparent dose response in D. F, bar graph of GFPuv-reporter-gene -fold repression showing the effect of each aSDS mutant compared with WT. Data from B–F are summarized in Table 1. A full comparison of Krel, EC50 -fold change, and -fold GFPuv repression is provided in Fig. S4. Error bars, S.E.

We then tested a compensatory C37U/C38U mutant that was intended to restore preQ1 binding and the dose response by promoting G·U wobble pairing between the SDS-aSDS in P3. However, the KD was 3 μm by ITC, and the in-cell dose response was again absent (Fig. 5 (C and D) and Table 1). Although CD analysis of C37U/C38U revealed no significant spectral difference compared with the WT riboswitch (Fig. S3B), the introduction of tandem uridines in an already U-rich sequence provides a likely basis for P3 folding heterogeneity (see below).

We then tested more conservative single mutants C37U and C38U. Each performed well in terms of preQ1 binding, giving KD values of 24.1 and 36.2 nm (Table 1). However, their dose-response characteristics and repression profiles were weaker, with EC50 values >850- and >1,600-fold higher than WT (Fig. 5 (D–F) and Table 1). This finding implies that a single G·U wobble in the SDS-aSDS pairing of the Lrh riboswitch is not ideal for gene regulation. It is known that a G-C pair and a G·U wobble are not isosteric (45). A cytidine at position 38 is conserved in the consensus sequence of the preQ1-II riboswitch 97% of the time. In contrast, position 37 appears to require a pyrimidine, which is found in 75% of sequences (21). The preference for at least one C-G pair is apparent in 90–97% of sequences of the updated preQ1-II riboswitch consensus model, although the cytidine occurs at position 37 rather than 38 (19). The collective findings suggest that the aSDS is important not only for regulatory switching but also to promote a functional riboswitch fold.

Discussion

The preQ1-II riboswitch is a gene-regulatory ncRNA that attenuates translation by sensing cellular levels of preQ1 (21, 40, 41). Translational regulation occurs by modulation of SDS accessibility—a common gene-regulation mechanism among bacterial riboswitches (1, 9). Despite the number of known riboswitch classes, only a handful of studies have sought to relate three-dimensional structure to in-cell gene-regulatory function (31, 36–39, 47–49). To meet this challenge, we previously established that the co-crystal structure of the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch bound to preQ1 is a relevant gene-off conformation, based on chemical modification analysis of switched and unswitched states in live bacteria (41). This validation makes the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch an excellent system to probe in vitro preQ1 binding in relation to in vivo gene regulation. Leveraging prior biochemical and biophysical analyses (19, 21, 25, 27, 28, 30), we focused our experiments here upon discrete regions of the structure to pinpoint chemical interactions that link effector binding to regulatory activity.

We first analyzed inclined A-minor bases flanking preQ1 in the binding pocket. These bases were deemed important for preQ1 recognition by the Spn preQ1-II riboswitch (27), as well as the preQ1-III riboswitch, which shares 10 common bases for preQ1 recognition—including equivalent A-minor bases in an otherwise dissimilar fold (50). Of the two A-minor bases, mutants at position 70 proved more deleterious than A55 in gene regulation, based on the need for ∼7,000-fold more preQ1 to elicit 50% GFPuv repression compared with WT (Table 1). Accordingly, the T-shaped stack between A70 and the preQ1 pyrrole ring appears operative in relaying the effector-occupancy status of the binding pocket to the underlying SDS. This connection entails positioning the A70 base atop A71 of the SDS within the U31·A71-U40 base triple while simultaneously hydrogen-bonding to the sugar edge of U41 (Fig. 2A). The T-shaped mode of A70-to-preQ1 engagement is reminiscent of a recent co-crystal structure of the preQ1-I riboswitch in complex with a small-molecule inhibitor identified using a high-throughput binding screen (17). Although the natural mode of effector binding by the class I riboswitch requires Watson–Crick recognition of the guanine-like face of preQ1 (51–54), the inhibitor instead makes a T-shaped contact with the specificity base, C15. This mode of recognition still permits high-affinity binding to the inhibitor, but lack of a Watson–Crick interaction with C15 could be an underlying reason why transcription termination by the inhibitor is less efficient than preQ1 (17). In other words, T-shaped stacking appears to partially uncouple the binding pocket from the distal expression platform. Conversely, the inclined A-minor interaction between A70 and preQ1 in the class II riboswitch is crucial to sense the ligand and propagate the occupancy status to the nearby SDS. Indeed, at least two mutants (Δ70 and A70C) exhibited relatively tight binding to preQ1 (KD values of 246 and 163 nm) but remained functionally impaired, with EC50 values of ∼140 μm—suggesting an inability to couple the ligand-bound state to the expression platform. This result suggests that synthetic riboswitch ligands intended to alter biological function will work best when they engage all of the recognition determinants utilized by the natural effector. Nonetheless, inhibitors that bind within riboswitch aptamer domains without strongly affecting regulatory function could still exert adverse antibacterial effects. This is because organismal fitness and virulence have been shown to be compromised in cases where regulatory RNAs were constitutively active or inactive for gene expression (55, 56). Hence, blocking the sensing domain of a riboswitch—without regulating switching—could be sufficient to compromise a bacterial attack on host cells.

Although the consensus sequence for the preQ1-II riboswitch class indicates high conservation of A70 (i.e. 95–97%), position A55 is only ∼50–75% conserved (19, 21). The lower conservation at position 55 was questioned previously in light of its importance for tight binding to preQ1 (27). Our binding results reinforce this interpretation, but our functional analysis indicates that A55 is indispensable for efficient regulatory switching at the nanomolar concentrations of preQ1 encountered in bacterial cells (51, 57). Like mutants at position 70, A55G, Δ55, and A55C caused moderate to substantial losses in preQ1 binding (KD values of 77, 153, and 433 nm). However, each mutant required substantially higher concentrations of preQ1 for gene repression compared with WT (i.e. EC50 of 24–36 μm compared with 20 nm for WT) (Table 1). As such, we propose that the consensus preQ1-II riboswitch model should be revised in a manner that varies the central J2–4 sequence—one of the least ordered regions of the crystal structure—while aligning the 3′-end to reflect the functional importance of the A-minor base at position 55. This revised consensus model would capture a much higher level of adenine conservation in accord with its important role in gene repression.

We next probed the functional importance of helix P4, which was deleted completely in prior studies to analyze its influence on SDS dynamics and P3 (expression platform) stability (27, 28). As in prior work in which deletion of the entire P4 helix resulted in ∼26-fold loss in preQ1 binding (27, 28), we found that reduction of the P4 helix to a single base pair reduced effector binding by 25-fold (i.e. KD of 66 nm). Although P4 deletion resulted in a substantially favorable decrease in the entropy of preQ1 binding (i.e. −9.2 kcal mol−1) (27), our shorter P4 helix produced an unfavorable enthalpy increase of +3 kcal mol−1 (Table S1). Moreover, the short P4 helix eroded the EC50 for gene regulation to ∼15 μm, or 760-fold higher than WT (Table 1). Based on these observations, we propose that the P4 helix is much more than a “screw cap” that serves to close off the binding pocket (27). Instead, P4 appears to serve as a lever that requires an optimal length (lever arm) to exert dynamics on the binding pocket and expression platform—contacts that are mediated by inclined A-minor bases A55 and A70 (Fig. 2A). Prior analysis supports this role because the full deletion of P4 yielded an overly stable SDS with reduced dynamics (28). Notably, the bound state of the preQ1-III riboswitch has also been shown to alter the dynamics of a comparable P4 helix joined by spatially identical A-minor bases (50). This interface appears to control pairing between the SDS and aSDS located >40 Å away from the preQ1-binding pocket. Because the HLout pseudoknot is a common RNA fold (8), it is likely that other riboswitches that juxtapose the effector recognition site near a P3 expression platform will show a similar gene-regulation dependence upon P4 length.

Major-groove base triples are another recurring motif found in ncRNAs (58–61). In some riboswitches, these triples play an integral role in effector recognition by providing a nexus for coaxially stacked helices to coalesce at helix-closing pairs that bind a cognate ligand (25, 50, 51, 62, 63). As such, we probed the role of conserved base triples that compose layers of the preQ1-II riboswitch binding-pocket floor and sub-floor that harbor the 5′-SDS. A major finding was that near-isosteric replacement of base triples (i.e. U·A-U with C·G·U) is sufficient to support preQ1 binding (i.e. KD values of 21 and 62 nm), but such substitutions cannot support efficient gene regulation (EC50 values of 170–200 μm). Notably, substitution of a U·A Hoogsteen interaction with a C·G Hoogsteen pair is well-tolerated in the context of telomerase pseudoknot base triples as well as MALAT base triples that stabilize the RNA (58, 60). Stability analysis of the U·A-U interaction in MALAT indicated that a U·G·U triple was comparable in stability with a C·G·U triple, with the latter interaction showing slightly more functional stabilization of the RNA in cells (43). This observation is reminiscent of our base triple observations for preQ1 binding. However, the associated 104-fold increase in EC50 relative to WT suggests that effector binding remains uncoupled from the expression platform in the context of base-triple mutations. In light of the rather modest stability changes in major-groove triple stability in prior work as well as our current studies on preQ1 binding, our results point to the importance of maintaining a complementary interface between base-triple minor-groove edges in the pocket floor and sub-floor with the minor-groove edge of helix P4. This structural feature appears to be a key facet of efficient gene regulation by the preQ1-II riboswitch.

Finally, we considered the aSDS, which is an integral part of the expression platform in translational riboswitches that must stably pair with the SDS to control protein expression (1). When we introduced tandem G·U wobble pairs into P3 (i.e. the SDS-aSDS helix), we observed damaging effects in terms of preQ1 binding and an absence of detectable gene regulation (i.e. a KD value of 3.1 μm with no dose response; Table 1). These deficiencies in binding and gene regulation are supported by differences in the internal base-pairing stabilities of 5′-GG-3′/3′-CC-5′ compared with 5′-GG-3′/3′-UU-5′, wherein the ΔΔG37 for a tandem G-C pair was 3.0 kcal mol−1 more favorable than a tandem G·U pair (64). However, we also reasoned that introduction of U at positions 37 and 38 caused misfolding of P3. Inspection of the sequence shows that this tandem uracil mutation leads to a stretch of eight consecutive U bases from U34 to U41 (Fig. 1B). As such, the WT C37/C38 patch appears to lock the register of an otherwise U-rich sequence that has the potential to slip during folding, resulting in impaired preQ1 binding and gene regulation. In the context of the Lrh preQ1-II WT sequence, the P3 stem appears to be stabilized best by tandem G-C pairs. Indeed, single G·U wobble mutations supported strong preQ1 binding (i.e. KD values of 24 and 36 nm) but were still incapable of robust switching (i.e. EC50 values of 0.85 and 1.60 μm). Support for the notion that tandem G-C pairing is a stabilizing feature comes from the Spn preQ1-II riboswitch, which harbors a single G-C pair at position C38 of its aSDS and a flanking G·U wobble pair that utilizes U37 (21). Despite the “nearest neighbor” prediction of only modest (+1.2 kcal mol−1) destabilization of the C38U variant (i.e. a 5′-GG-3′/3′-CU-5′ pair compared with a tandem G-C pair) (64), our results suggest that the single G·U wobble in P3 should substantially weaken the gene-regulatory capability of the Spn riboswitch compared with the WT Lrh riboswitch herein. A recent analysis corroborates this notion, wherein the EC50 of the Spn riboswitch for cell reporter-gene regulation is 96 μm (49), as compared with 19.5 nm for the Lrh riboswitch. Such differences in structure-activity relationships between riboswitches of the same class could be a strategy to fine-tune gene-regulatory functions to meet the distinct fitness needs of a specific organism (65, 66).

Experimental procedures

RNA preparation and purification

The 76-mer WT Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch and the accompanying mutants were synthesized by in vitro transcription using DNA templates (IDT Inc.) to produce each sequence in Table S2. Templates included tandem 2′-O-methyl groups added to the 3′-end (67). RNA was transcribed at 37 °C in 75 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 12.5 mm DTT, 30 mm MgCl2, 0.01% Triton X-100, 2.2 mm Spermidine, 2.1% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.13% (v/v) BSA (New England Biolabs), 4.2 mm rNTP mix, 1 μm primer-annealed template, and ∼50 μg ml−1 T7 polymerase. After overnight incubation, the reaction was 0.2-μm-filtered and passed through the first of two Toyopearl 650S DEAE columns (Tosoh Bioscience, LLC). The eluted RNA was precipitated in undiluted ethanol and resuspended before purification. Purification was performed by 8% denaturing PAGE using a 29:1 ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide, 1× TBE buffer, and 7 m urea (41, 68). The RNA was extracted from the gels and subjected to a second anion-exchange step. Pure lyophilized RNA was stored at −20 °C.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

RNA was folded by suspending in a folding buffer of 10 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7.0, and 100 mm NaCl. The RNA was heated in an aluminum heating block to 65 °C for 3 min in a heating block followed by the addition of MgCl2 at 65 °C to a final concentration of 6 mm over 5 min. The sample was then slow-cooled in the aluminum block to room temperature. RNA samples were dialyzed at 4 °C overnight using a 3,500 molecular weight cutoff Slide-A-Lyzer (Thermo) against 4 liters of ITC Buffer (50 mm HEPES-Na, pH 7.0, 100 mm NaCl, and 6 mm MgCl2). PreQ1 powder (LeadGen Laboratories, LLC) was dissolved in ITC buffer to a concentration ≥10 times higher than the RNA. ITC measurements were conducted at 20 °C using a VP-ITC or a PEAQ-ITC (Malvern Panalytical) (69). PreQ1 in the syringe was titrated into riboswitch in the cell using 29 injections (VP-ITC) or 20 injections (PEAQ-ITC). For the VP-ITC, each injection was 10 μl except for the initial 3-μl technical injection. The injection spacing was 240 s, except for the C37U/C38U mutant, which was 1,200 s. For the PEAQ-ITC, injection volumes were 2 μl, except for the 0.4-μl technical injection. The spacing between injections was 600 s. Whenever possible, c values were kept between 5 and 1,000, where c = Ka·[M]·n; [M] is the concentration of riboswitch in the cell, and n is the binding stoichiometry (70, 71). Under conditions where c > 1,000 (i.e. WT in Fig. S1A), the KD is typically considered an estimate of binding due to the sparse number of data points available to fit the sloped, linear region of a sigmoidal binding curve. In general, the reliability of our KD measurements is supported by the reproducibility of thermograms (Fig. S2), the well-defined zero-slope regions of the sigmoidal titration curve, attainment of binding saturation, lack of an appreciable buffer mismatch, and the well-defined fit of the binding model to the data. Likewise, shallow slopes associated with c < 5 indicate that the associated KD values are only estimates (70) (i.e. C37G/C38G in Fig. 5B and C37U/C38U in Fig. S1J). All ITC thermograms were analyzed with MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis software using a 1:1 binding model, a stoichiometry n value fixed at 1.0 (unless noted), and a cell concentration that was allowed to vary during the final fit. Two or more replicate measurements were performed for each sample. Representative thermograms and curve fits are provided in Figs. 2–5 and Fig. S1. A plot of KD value replicates is shown in Fig. S2 to emphasize the agreement of duplicate measurements. Average thermodynamic parameters are provided in Table S1.

PAGE and CD analyses

To determine whether RNA folding in the presence of Mg2+ at 65 °C produced degradation using the standard folding conditions described for ITC, we analyzed WT Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch samples by denaturing PAGE. Mr markers included the microRNA standard (New England Biolabs) and the Tte preQ1-I riboswitch. A sample folded in the presence of 6 mm Mg2+ with heating at 65 °C showed no detectable difference in size or degradation compared with a control sample that was resuspended in an ITC buffer devoid of Mg2+ that did not undergo heating (Fig. S3A). This result is corroborated by prior studies of the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch that showed a high level of preQ1 binding, folding, and crystallization after Mg2+-dependent folding between 65 and 70 °C (25, 30, 41).

To evaluate changes in global folding of Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch variants relative to WT, we acquired CD spectra for representative mutant classes on a J-1100 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Inc.) (Fig. S3B). Riboswitch samples folded in ITC buffer, as described above, were dialyzed at 4 °C using a 3,500 molecular weight cutoff Slide-A-Lyzer (Thermo) against a CD buffer comprising 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, with 6 mm Mg(C2H3O2)2; this buffer was used as a blank and diluent. This buffer condition was shown previously to support a high level of Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch folding in the absence of preQ1 (30). Each sample was diluted to an OD260 nm of 3.55. As a control experiment, the WT riboswitch was folded in ITC buffer in which Mg2+ ions were replaced with 0.5 mm EDTA. The absence of Mg2+ produced incomplete folding of the Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch in prior analysis (30).

In-cell GFPuv reporter assays

The WT Lrh preQ1-II riboswitch upstream of a GFPuv reporter gene was inserted into the pBR327-Lrh(WT)-GFPuv plasmid (41). Riboswitch mutants were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis (GenScript Inc.) on the WT sequence (Fig. 1B) in the context of the parent plasmid, generating the desired mutant sequences (Figs. 2A, 3A, 4A, and 5A). Care was taken during the mutant design to avoid ablation of base-pairing interactions between the riboswitch SDS and the E. coli 16S rRNA, which is essential for translation initiation. All resulting plasmids were sequence-verified. Positive and negative control sequences were used in which the riboswitch was removed and replaced by the Shine–Dalgarno sequence or the Shine–Dalgarno sequence was replaced by the reverse complement as described (41). All plasmids were transformed into competent E. coli strain JW2765 ΔqueF (Coli Genetic Stock Center, Yale University) (72) to eliminate preQ1 synthesis that could influence the assays. To ensure that preQ1 came only from exogenous supplementation, agar plates and liquid cultures were prepared using a chemically defined CSB medium (39, 41). Transformed cells were grown on CSB-amp (100 μg ml−1) plates overnight at 37 °C. Isolated single colonies were used to inoculate overnight liquid cultures of 2.5 ml of CSB-amp. These cells were used to inoculate 2.5-ml cultures of fresh CSB-amp medium with varying concentrations of preQ1: 0, 1 nm, 10 nm, 100 nm, 1 μm, 10 μm, 100 μm, 1 mm, and 3 mm. From a starting optical density (OD600) of 0.05, cells were grown for 5 h at 37 °C. This time point was chosen because it represents the mid-log phase of growth for this bacterial strain in CSB medium. GFPuv fluorescence was measured using an Enspire plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). For every mutant, at least three biological replicates were employed for fluorescence measurements at each preQ1 concentration. Fluorescence utilized an excitation wavelength of 395 nm and emission at a wavelength of 510 nm. All readings were normalized based on the A600 cell densities of each sample and then corrected for background by subtracting the negative-control values. -Fold repression, EC50 analysis, and curve fits were performed as described (36) using GraphPad Prism. -Fold repression is calculated as the ratio between the maximal fluorescence (effector-free state, gene on) and the minimal fluorescence (effector-bound state, gene off). Representative curve fits are provided in Figs. 2–5. Average values derived from GFPuv functional analyses are reported in Table 1. A comparison of EC50 changes and repression relative to WT is provided for all variants in Fig. S4. GFPuv fluorescence emission from WT and mutants is shown in Fig. S5 to emphasize GFPuv production in the effector-free state.

Author contributions

D. D. data curation; D. D. and J. E. W. formal analysis; D. D. validation; D. D. investigation; D. D. methodology; D. D. and J. E. W. writing-original draft; D. D. and J. E. W. writing-review and editing; J. E. W. conceptualization; J. E. W. resources; J. E. W. supervision; J. E. W. funding acquisition; J. E. W. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivan Belashov and members of the Wedekind laboratory for technical assistance. We thank Andrew DiCola and Jermaine Jenkins for assistance with CD. We thank Griffin Schroeder for critical review of the manuscript. We thank Jay Schneekloth for helpful discussions. We thank David Mathews for insightful suggestions on RNA folding and thermodynamic analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM063162 (to J. E. W.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article was selected as one of our Editors' Picks.

This article contains Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S6.

- preQ1

- prequeuosine1

- preQ1-II

- class II preQ1 riboswitch

- OD

- optical density

- Spn

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Lrh

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus

- SDS

- Shine–Dalgarno sequence

- aSDS

- anti-SDS

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry.

References

- 1. Breaker R. R. (2018) Riboswitches and translation control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10, a032797 10.1101/cshperspect.a032797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breaker R. R. (2012) Riboswitches and the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a003566 10.1101/cshperspect.a003566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sherwood A. V., and Henkin T. M. (2016) Riboswitch-mediated gene regulation: novel RNA architectures dictate gene expression responses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 361–374 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCown P. J., Corbino K. A., Stav S., Sherlock M. E., and Breaker R. R. (2017) Riboswitch diversity and distribution. RNA 23, 995–1011 10.1261/rna.061234.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wedekind J. E., Dutta D., Belashov I. A., and Jenkins J. L. (2017) Metalloriboswitches: RNA-based inorganic ion sensors that regulate genes. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 9441–9450 10.1074/jbc.R117.787713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Belashov I. A., Dutta D., Salim M., and Wedekind J. E. (2015) Tails of Three Knotty Switches: How PreQ1 Riboswitch Structures Control Protein Translation. In: eLS. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0021031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garst A. D., Edwards A. L., and Batey R. T. (2011) Riboswitches: structures and mechanisms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a003533 10.1101/cshperspect.a003533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peselis A., and Serganov A. (2014) Structure and function of pseudoknots involved in gene expression control. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 5, 803–822 10.1002/wrna.1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Serganov A., and Nudler E. (2013) A decade of riboswitches. Cell 152, 17–24 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sudarsan N., Cohen-Chalamish S., Nakamura S., Emilsson G. M., and Breaker R. R. (2005) Thiamine pyrophosphate riboswitches are targets for the antimicrobial compound pyrithiamine. Chem. Biol. 12, 1325–1335 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blount K. F., Wang J. X., Lim J., Sudarsan N., and Breaker R. R. (2007) Antibacterial lysine analogs that target lysine riboswitches. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 44–49 10.1038/nchembio842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee E. R., Blount K. F., and Breaker R. R. (2009) Roseoflavin is a natural antibacterial compound that binds to FMN riboswitches and regulates gene expression. RNA Biol. 6, 187–194 10.4161/rna.6.2.7727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howe J. A., Wang H., Fischmann T. O., Balibar C. J., Xiao L., Galgoci A. M., Malinverni J. C., Mayhood T., Villafania A., Nahvi A., Murgolo N., Barbieri C. M., Mann P. A., Carr D., Xia E., et al. (2015) Selective small-molecule inhibition of an RNA structural element. Nature 526, 672–677 10.1038/nature15542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howe J. A., Xiao L., Fischmann T. O., Wang H., Tang H., Villafania A., Zhang R., Barbieri C. M., and Roemer T. (2016) Atomic resolution mechanistic studies of ribocil: a highly selective unnatural ligand mimic of the E. coli FMN riboswitch. RNA Biol. 13, 946–954 10.1080/15476286.2016.1216304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang H., Mann P. A., Xiao L., Gill C., Galgoci A. M., Howe J. A., Villafania A., Barbieri C. M., Malinverni J. C., Sher X., Mayhood T., McCurry M. D., Murgolo N., Flattery A., Mack M., and Roemer T. (2017) Dual-targeting small-molecule inhibitors of the Staphylococcus aureus FMN riboswitch disrupt riboflavin homeostasis in an infectious setting. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 576–588.e6 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blount K. F., Megyola C., Plummer M., Osterman D., O'Connell T., Aristoff P., Quinn C., Chrusciel R. A., Poel T. J., Schostarez H. J., Stewart C. A., Walker D. P., Wuts P. G., and Breaker R. R. (2015) Novel riboswitch-binding flavin analog that protects mice against Clostridium difficile infection without inhibiting cecal flora. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 5736–5746 10.1128/AAC.01282-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Connelly C. M., Numata T., Boer R. E., Moon M. H., Sinniah R. S., Barchi J. J., Ferré-D'Amaré A. R., and Schneekloth J. S. (2019) Synthetic ligands for PreQ1 riboswitches provide structural and mechanistic insights into targeting RNA tertiary structure. Nat. Commun. 10, 1501 10.1038/s41467-019-09493-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vicens Q., Mondragón E., Reyes F. E., Coish P., Aristoff P., Berman J., Kaur H., Kells K. W., Wickens P., Wilson J., Gadwood R. C., Schostarez H. J., Suto R. K., Blount K. F., and Batey R. T. (2018) Structure-activity relationship of flavin analogues that target the flavin mononucleotide riboswitch. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 2908–2919 10.1021/acschembio.8b00533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCown P. J., Liang J. J., Weinberg Z., and Breaker R. R. (2014) Structural, functional, and taxonomic diversity of three preQ1 riboswitch classes. Chem. Biol. 21, 880–889 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roth A., Winkler W. C., Regulski E. E., Lee B. W., Lim J., Jona I., Barrick J. E., Ritwik A., Kim J. N., Welz R., Iwata-Reuyl D., and Breaker R. R. (2007) A riboswitch selective for the queuosine precursor preQ1 contains an unusually small aptamer domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 308–317 10.1038/nsmb1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meyer M. M., Roth A., Chervin S. M., Garcia G. A., and Breaker R. R. (2008) Confirmation of a second natural preQ1 aptamer class in Streptococcaceae bacteria. RNA 14, 685–695 10.1261/rna.937308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCarty R. M., and Bandarian V. (2008) Deciphering deazapurine biosynthesis: pathway for pyrrolopyrimidine nucleosides toyocamycin and sangivamycin. Chem. Biol. 15, 790–798 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCarty R. M., and Bandarian V. (2012) Biosynthesis of pyrrolopyrimidines. Bioorg. Chem. 43, 15–25 10.1016/j.bioorg.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weinberg Z., Barrick J. E., Yao Z., Roth A., Kim J. N., Gore J., Wang J. X., Lee E. R., Block K. F., Sudarsan N., Neph S., Tompa M., Ruzzo W. L., and Breaker R. R. (2007) Identification of 22 candidate structured RNAs in bacteria using the CMfinder comparative genomics pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 4809–4819 10.1093/nar/gkm487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liberman J. A., Salim M., Krucinska J., and Wedekind J. E. (2013) Structure of a class II preQ1 riboswitch reveals ligand recognition by a new fold. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 353–355 10.1038/nchembio.1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zallot R., Yuan Y., and de Crécy-Lagard V. (2017) The Escherichia coli COG1738 member YhhQ is involved in 7-cyanodeazaguanine (preQ(0)) transport. Biomolecules 7, e12 10.3390/biom7010012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kang M., Eichhorn C. D., and Feigon J. (2014) Structural determinants for ligand capture by a class II preQ1 riboswitch. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. U.S.A. 111, E663–E671 10.1073/pnas.1400126111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soulière M. F., Altman R. B., Schwarz V., Haller A., Blanchard S. C., and Micura R. (2013) Tuning a riboswitch response through structural extension of a pseudoknot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E3256–E3264 10.1073/pnas.1304585110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aytenfisu A. H., Liberman J. A., Wedekind J. E., and Mathews D. H. (2015) Molecular mechanism for preQ1-II riboswitch function revealed by molecular dynamics. RNA 21, 1898–1907 10.1261/rna.051367.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warnasooriya C., Ling C., Belashov I. A., Salim M., Wedekind J. E., and Ermolenko D. N. (2019) Observation of preQ1-II riboswitch dynamics using single-molecule FRET. RNA Biol. 16, 1086–1092 10.1080/15476286.2018.1536591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kubota M., Tran C., and Spitale R. C. (2015) Progress and challenges for chemical probing of RNA structure inside living cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 933–941 10.1038/nchembio.1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Henkin T. M. (2014) Preface—riboswitches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1839, 899 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rinaldi A. J., Lund P. E., Blanco M. R., and Walter N. G. (2016) The Shine-Dalgarno sequence of riboswitch-regulated single mRNAs shows ligand-dependent accessibility bursts. Nat. Commun. 7, 8976 10.1038/ncomms9976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strobel E. J., Watters K. E., Nedialkov Y., Artsimovitch I., and Lucks J. B. (2017) Distributed biotin-streptavidin transcription roadblocks for mapping cotranscriptional RNA folding. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e109 10.1093/nar/gkx233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watters K. E., Strobel E. J., Yu A. M., Lis J. T., and Lucks J. B. (2016) Cotranscriptional folding of a riboswitch at nucleotide resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 1124–1131 10.1038/nsmb.3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson J. E. Jr, Reyes F. E., Polaski J. T., and Batey R. T. (2012) B12 cofactors directly stabilize an mRNA regulatory switch. Nature 492, 133–137 10.1038/nature11607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Polaski J. T., Holmstrom E. D., Nesbitt D. J., and Batey R. T. (2016) Mechanistic insights into cofactor-dependent coupling of RNA folding and mRNA transcription/translation by a cobalamin riboswitch. Cell Rep. 15, 1100–1110 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Polaski J. T., Webster S. M., Johnson J. E. Jr., and Batey R. T. (2017) Cobalamin riboswitches exhibit a broad range of ability to discriminate between methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 11650–11658 10.1074/jbc.M117.787176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holmstrom E. D., Polaski J. T., Batey R. T., and Nesbitt D. J. (2014) Single-molecule conformational dynamics of a biologically functional hydroxocobalamin riboswitch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16832–16843 10.1021/ja5076184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Vlack E. R., Topp S., and Seeliger J. C. (2017) Characterization of engineered preQ1 riboswitches for inducible gene regulation in mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00656–16 10.1128/JB.00656-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dutta D., Belashov I. A., and Wedekind J. E. (2018) Coupling green fluorescent protein expression with chemical modification to probe functionally relevant riboswitch conformations in live bacteria. Biochemistry 57, 4620–4628 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bellaousov S., and Mathews D. H. (2010) ProbKnot: fast prediction of RNA secondary structure including pseudoknots. RNA 16, 1870–1880 10.1261/rna.2125310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown J. A., Kinzig C. G., DeGregorio S. J., and Steitz J. A. (2016) Hoogsteen-position pyrimidines promote the stability and function of the MALAT1 RNA triple helix. RNA 22, 743–749 10.1261/rna.055707.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Batey R. T., Rambo R. P., and Doudna J. A. (1999) Tertiary motifs in RNA structure and folding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 38, 2326–2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leontis N. B., and Westhof E. (2001) Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA 7, 499–512 10.1017/S1355838201002515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chauca-Diaz A. M., Choi Y. J., and Resendiz M. J. (2015) Biophysical properties and thermal stability of oligonucleotides of RNA containing 7,8-dihydro-8-hydroxyadenosine. Biopolymers 103, 167–174 10.1002/bip.22579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Caron M. P., Bastet L., Lussier A., Simoneau-Roy M., Massé E., and Lafontaine D. A. (2012) Dual-acting riboswitch control of translation initiation and mRNA decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E3444–E3453 10.1073/pnas.1214024109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watters K. E., Yu A. M., Strobel E. J., Settle A. H., and Lucks J. B. (2016) Characterizing RNA structures in vitro and in vivo with selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension sequencing (SHAPE-Seq). Methods 103, 34–48 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Neuner E., Frener M., Lusser A., and Micura R. (2018) Superior cellular activities of azido- over amino-functionalized ligands for engineered preQ1 riboswitches in E. coli. RNA Biol. 15, 1376–1383 10.1080/15476286.2018.1534526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liberman J. A., Suddala K. C., Aytenfisu A., Chan D., Belashov I. A., Salim M., Mathews D. H., Spitale R. C., Walter N. G., and Wedekind J. E. (2015) Structural analysis of a class III preQ1 riboswitch reveals an aptamer distant from a ribosome-binding site regulated by fast dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E3485–E3494 10.1073/pnas.1503955112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jenkins J. L., Krucinska J., McCarty R. M., Bandarian V., and Wedekind J. E. (2011) Comparison of a preQ1 riboswitch aptamer in metabolite-bound and free states with implications for gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24626–24637 10.1074/jbc.M111.230375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Spitale R. C., Torelli A. T., Krucinska J., Bandarian V., and Wedekind J. E. (2009) The structural basis for recognition of the preQ0 metabolite by an unusually small riboswitch aptamer domain. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11012–11016 10.1074/jbc.C900024200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kang M., Peterson R., and Feigon J. (2009) Structural insights into riboswitch control of the biosynthesis of queuosine, a modified nucleotide found in the anticodon of tRNA. Mol. Cell 33, 784–790 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Klein D. J., Edwards T. E., and Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. (2009) Cocrystal structure of a class I preQ1 riboswitch reveals a pseudoknot recognizing an essential hypermodified nucleobase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 343–344 10.1038/nsmb.1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Babina A. M., Lea N. E., and Meyer M. M. (2017) In vivo behavior of the tandem glycine riboswitch in Bacillus subtilis. MBio 8, e01602–17 10.1128/mBio.01602-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Warrier I., Ram-Mohan N., Zhu Z., Hazery A., Echlin H., Rosch J., Meyer M. M., and van Opijnen T. (2018) The transcriptional landscape of Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 reveals a complex operon architecture and abundant riboregulation critical for growth and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007461 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hoops G. C., Townsend L. B., and Garcia G. A. (1995) tRNA-guanine transglycosylase from Escherichia coli: structure-activity studies investigating the role of the aminomethyl substituent of the heterocyclic substrate PreQ1. Biochemistry 34, 15381–15387 10.1021/bi00046a047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Theimer C. A., Blois C. A., and Feigon J. (2005) Structure of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot reveals conserved tertiary interactions essential for function. Mol. Cell 17, 671–682 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brown J. A., Valenstein M. L., Yario T. A., Tycowski K. T., and Steitz J. A. (2012) Formation of triple-helical structures by the 3′-end sequences of MALAT1 and MENβ noncoding RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19202–19207 10.1073/pnas.1217338109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brown J. A., Bulkley D., Wang J., Valenstein M. L., Yario T. A., Steitz T. A., and Steitz J. A. (2014) Structural insights into the stabilization of MALAT1 noncoding RNA by a bipartite triple helix. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 633–640 10.1038/nsmb.2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Belashov I. A., Crawford D. W., Cavender C. E., Dai P., Beardslee P. C., Mathews D. H., Pentelute B. L., McNaughton B. R., and Wedekind J. E. (2018) Structure of HIV TAR in complex with a lab-evolved RRM provides insight into duplex RNA recognition and synthesis of a constrained peptide that impairs transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 6401–6415 10.1093/nar/gky529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gilbert S. D., Rambo R. P., Van Tyne D., and Batey R. T. (2008) Structure of the SAM-II riboswitch bound to S-adenosylmethionine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 177–182 10.1038/nsmb.1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Smith K. D., Shanahan C. A., Moore E. L., Simon A. C., and Strobel S. A. (2011) Structural basis of differential ligand recognition by two classes of bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate-binding riboswitches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7757–7762 10.1073/pnas.1018857108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chen J. L., Dishler A. L., Kennedy S. D., Yildirim I., Liu B., Turner D. H., and Serra M. J. (2012) Testing the nearest neighbor model for canonical RNA base pairs: revision of GU parameters. Biochemistry 51, 3508–3522 10.1021/bi3002709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dutta D., and Wedekind J. E. (2015) Gene regulation gets in tune: how riboswitch tertiary-structure networks adapt to meet the needs of their transcription units. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 3469–3472 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wostenberg C., Ceres P., Polaski J. T., and Batey R. T. (2015) A highly coupled network of tertiary interactions in the SAM-I riboswitch and their role in regulatory tuning. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 3473–3490 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sherlin L. D., Bullock T. L., Nissan T. A., Perona J. J., Lariviere F. J., Uhlenbeck O. C., and Scaringe S. A. (2001) Chemical and enzymatic synthesis of tRNAs for high-throughput crystallization. RNA 7, 1671–1678 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lippa G. M., Liberman J. A., Jenkins J. L., Krucinska J., Salim M., and Wedekind J. E. (2012) Crystallographic analysis of small ribozymes and riboswitches. in Ribozymes (Hartig J. S., ed) pp. 159–184, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liberman J. A., Bogue J. T., Jenkins J. L., Salim M., and Wedekind J. E. (2014) ITC analysis of ligand binding to preQ(1) riboswitches. Methods Enzymol. 549, 435–450 10.1016/B978-0-12-801122-5.00018-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wiseman T., Williston S., Brandts J. F., and Lin L. N. (1989) Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem. 179, 131–137 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Velazquez-Campoy A., Leavitt S. A., and Freire E. (2004) Characterization of protein-protein interactions by isothermal titration calorimetry. Methods Mol. Biol. 261, 35–54 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., Datsenko K. A., Tomita M., Wanner B. L., and Mori H. (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.