Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) that employs the photochemical interaction of light, photosensitizer and oxygen is an established modality for the treatment of cancer. However, dosimetry for PDT is becoming increasingly complex due to the heterogeneous photosensitizer uptake by the tumor, and complicated relationship between the tissue oxygenation ([3O2]), interstitial light distribution, photosensitizer photobleaching and PDT effect. As a result, experts argue that the failure to realize PDT’s true potential is, at least partly due to the complexity of the dosimetry problem. In this study, we examine the efficacy of singlet oxygen explicit dosimetry (SOED) based on the measurements of the interstitial light fluence rate distribution, changes of [3O2] and photosensitizer concentration during Photofrin-mediated PDT to predict long-term control rates of radiation-induced fibrosarcoma tumors. We further show how variation in tissue [3O2] between animals induces variation in the treatment response for the same PDT protocol. PDT was performed with 5 mg kg−1 Photofrin (a drug-light interval of 24 h), in-air fluence rates (ϕair) of 50 and 75 mW cm−2 and in-air fluences from 225 to 540 J cm−2. The tumor regrowth was tracked for 90 d after the treatment and Kaplan–Meier analyses for local control rate were performed based on a tumor volume ⩽100 mm3 for the two dosimetry quantities of PDT dose and SOED. Based on the results, SOED allowed for reduced subject variation and improved treatment evaluation as compared to the PDT dose.

Keywords: PDT dose, tissue oxygenation, photofrin concentration, long-term survival, SOED

Introduction

Photofrin-mediated photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of microinvasive endobronchial non-small cell lung cancer and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus (Kim et al 2017). This treatment method is advantageous for these diseases as it does not involve ionizing radiation and can be well-localized (Agostinis et al 2011, Penjweini et al 2013). Photofrin undergoes mostly a type II PDT processes upon photoexcitation in which the triplet state transfers energy to oxygen (3O2) to produce reactive singlet oxygen (1O2) (Qiu et al 2016a, 2016b). High concentration of 1O2 ([1O2]rx) causes cytotoxicity and eventually cell death and/or therapeutic effects (Penjweini et al 2015, 2016a).

Although Photofrin-mediated PDT works and causes few long-term problems, it is not widely used to treat cancer today. Photofrin-PDT is strongly dependent on the production of [1O2]rx, and any of several parameters, photosensitizer concentration, tissue oxygenation ([3O2]) and light, can be a limiting factor in determining the treatment efficacy at each point in a target organ. Significant heterogeneity in photosensitizer uptake by tumors has been demonstrated in both preclinical and clinical studies (Hahn et al 2006, Ozturk et al 2014). The microenvironmental differences in inter-capillary distance and pre-existing hypoxia, which will vary depending on the target tumor tissue (Woodhams et al 2007), causes a severe and heterogeneous distribution of [3O2] in the tumors (Hockel and Vaupel 2001). Both photochemical consumption of 3O2 and micro-vascular shutdown during PDT can lead to further depletion of 3O2 and insufficient [1O2]rx production for the tumor destruction (Vaupel et al 1987, Zhang et al 2008).

PDT dosimetry has so far involved the prescription of a delivered light fluence (energy per unit area), an administered photosensitizer dose, and photosensitizer photobleaching ratio (Wang et al 2007). However, due to the complex relationship between [3O2], photosensitizer photobleaching and PDT effect, as well as the complicated nature of the [3O2] measurements in vivo, to our knowledge there is no study that directly incorporates the changes of measured [3O2] in their dosimetry, with correlation to the final treatment outcome (Woodhams et al 2007).

In this study, we incorporate the interstitial distribution of light fluence rate (ϕ), the measured interstitial Photofrin concentration, and the changes of [3O2] during PDT in a mathematical model, the so-called singlet oxygen explicit dosimetry (SOED), to help visualize the average [1O2]rx in radiation-induced fibrosarcoma (RIF) tumor models. Then, we show a better correlation of the [1O2]rx with the long-term Photofrin-PDT outcome as compared to the PDT dose, which is known as the most reliable dosimetry quantity for PDT (Rizvi et al 2013, Penjweini et al 2016a); PDT dose is calculated by the time integral of the photosensitizer concentration and ϕ.

Methods

PDT of RIF tumor on shoulder and flank

RIF tumors were propagated by the intradermal injection of 1 × 107 cells ml−1 cells over the right shoulders of 28 female C3H mice (6–8 week old; NCI-Frederick, MD, US). When tumors reached ~3–5 mm in diameter, 5 mg kg−1 Photofrin was injected via tail vein. Following 24 h drug–light interval, an optical fiber with a microlens attachment was coupled with a 630 nm diode laser with a maximum output power of 8W (B & W Tek Inc., Newark, DE, US) to produce a collimated beam with a diameter of 1 cm on the surface of the tumor. Based on our previous studies, PDT regimens that used in-air fluence rate (ϕair) of 50 and 70 mW cm−2 and generated 1.1 mM ⩽ [1O2]rx could lead to an enhanced PDT effect (Qiu et al 2016a, 2016b, 2017). Therefore, the tumors were treated with ϕair = 50 or 75 mW cm−2 and the treatment time was adjusted in a way to reach 1.1 mM ⩽ [1O2]rx; [1O2]rx was calculated based on interstitial ϕ distribution, measured initial tissue oxygenation ([3O2]0) and Photofrin concentration. In order to avoid pain, suffering, and distress in mice, PDT was performed under anesthesia and the treatment time was restricted to maximum 7200 s; total fluence was in the range of 225–540 J cm−2. Table 1 shows the PDT protocol and measured parameters for each mouse.

Table 1.

PDT treatment groups categorized based on the PDT dose and the amounts of [1O2]rx generated during the treatment. All mice were given 5 mg kg−1 Photofrin via tail vein injection (drug-light interval 24 h), and were treated with 630 nm wavelength. This protocol was formulated so that SOED1 for all mice ≥1.1 mM, but a few mice fell below that requirement after final data analysis of Photofrin concentration after PDT. Interstitial Photofrin concentration, initial tissue oxygenation ([3O2]0), in-air light fluence rate (ϕair), and treatment time have been shown for each group of mice.

| SOED1a | SOED2b | PDT dosec (μMJ cm−2) | Photofrin (μM) | [3O2]0 (μM) | ϕair (mW cm−2) | Timed (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.734 ≤ [1O2]rx ≤ 1.1 mM | 0.366 ≤ [1O2]rx ≤ 0.734 mM | 400–800 | 2.2 | 14.6 ± 3.0 | 75 | 6200 |

| 2.5 | 5.3 ± 3.2 | 7200 | ||||

| 1.9 | 17.6 ± 2.0 | |||||

| 2.4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | |||||

| 2.8 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 50 | 7200 | |||

| 2.3 | 59.4 ± 16.8 | |||||

| 1.9 | 41.8 ± 5.0 | 75 | ||||

| 2.7 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 50 | ||||

| 1.1 mM ≤ [1O2]rx | 3.0 | 14.8 ± 4.5 | 50 | 7200 | ||

| 2.9 | 52.0 ± 13.0 | |||||

| 0.734 ≤ [1O2]rx ≤ 1.1 mM | 3.7 | 42.0 ± 8.0 | ||||

| 1200 ≤ | 4.9 | 8.5 ± 2.5 | 75 | |||

| 3.7 | 32.5 ± 7.3 | |||||

| 9.1 | 14.9 ± 5.0 | 3000 | ||||

| 1.1 mM ≤ [1O2]rx | 5.9 | 26.1 ± 7.0 | 50 | 7200 | ||

| 5.3 | 48.8 ± 8.9 | |||||

| 5.8 | 20.3 ± 5.2 | |||||

| 7.9 | 20.3 ± 4.1 | 75 | 5400 | |||

| 4.9 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 7200 | ||||

| 5.4 | 25.2 ± 3.0 | 50 | 5400 | |||

| 800–1200 | 6.2 | 13.0 ± 5.0 | ||||

| 4.6 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 7200 | ||||

| 4.3 | 35.8 ± 6.5 | |||||

| 2.9 | 26.4 ± 7.0 | 75 | ||||

| 3.9 | 10.5 ± 3.0 | |||||

| 3.6 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | |||||

| 3.7 | 32.5 ± 7.3 | |||||

| 5.3 | 48.8 ± 8.9 | 50 |

SOED1 groups categorized based on the [1O2]rx values obtained from the measured initial tissue oxygenation [3O2]0.

SOED2 groups categorized based on the [1O2]rx values obtained from the whole oxygen spectra measured before and during PDT.

PDT dose calculated with the integral of the light fluence rate and Photofrin concentration over time.

PDT treatment time.

In another set of experiments, RIF cells (1 × 107 cells ml−1) were injected in the right flank of three female C3H mice. When the tumors reached ~3–5 mm in diameter, hypoxia was developed in the tumors by tightening of the muscles on flank using a tourniquet that occluded blood flow to the tumor. The hypoxic tumors were treated with ϕair = 50 mW cm−2 and total fluence of 250 J cm−2; the Photofrin injection protocol was the same as the previous group. Then, the results were compared to the RIF tumors on shoulder treated with the same PDT protocol to study the impact of tissue [3O2] on Photofrin-PDT outcome. Eight tumor-bearing mice with no Photofrin and no PDT were used as controls.

Animals were under the care of the University of Pennsylvania Laboratory Animal Resources. All studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Interstitial Photofrin uptake

A custom-made multi-fiber spectroscopic contact probe and single value decomposition (SVD) fitting method were used to obtain the Photofrin concentration in tumors before and after the PDT. The accuracy of the in vivo measurements was additionally evaluated by ex vivo measurements of the Photofrin concentration. The details of the contact probe, SVD method and the correlation of the ex vivo versus in vivo measurements can be found elsewhere (Finlay et al 2001, Qiu et al 2016a). The agreement between the in vivo and ex vivo measurements was found to be within 2% from seven measurements for Photofrin concentrations between 1 and 5 μM (Qiu et al 2016a).

In another set of mice, three mice bearing RIF tumor on their right shoulder and injected with 5 mg kg−1 Photofrin were sacrificed. Then, their tumors were excised for imaging of the interstitial Photofrin heterogeneity using a commercial Zeiss LSM 510 META 2-photon confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63 × /1.4 NA Oil immersion objective (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Photofrin was excited at 780 nm and the fluorescence was collected by a 641/75 nm band-pass filter; power was attenuated to ~8–12 mW for the imaging.

Monitoring of the interstitial [3O2] and its changes during the PDT

A multi-channel dissolved oxygen partial pressure (pO2) and temperature monitor (OxyLite Pro, Oxford Optronix, Oxford, UK) with an oxygen-only bare-fiber sensor (phosphorescence-based, NX-BF/O/E, Oxford Optonix, UK) was used to measure the hemoglobin pO2 for each tumor. Then, [3O2] was calculated by multiplying the measured pO2 with 3O2 solubility in tissue, which is reported to be 1.295 μM mmHg−1 (Zhu et al 2015, Penjweini et al 2016b). In order to account for the heterogeneity, [3O2]0 was measured close to the surface, center and bottom of the tumor mass (~1, 2 and 3 mm with about ± 0.5 mm uncertainty) immediately before the PDT. As much useful information is gleaned from the [3O2] changes during the PDT, the full time-dependent spectra was measured around the base of the tumor at 3 mm depth that allowed calculation of the minimum [1O2]rx value covering the entire tumor to account for the worst case scenario.

Singlet oxygen explicit dosimetry (SOED)

Two SOED models were used to evaluate the PDT outcomes: SOED1 was calculated based on the average value of [3O2]0 measured on the surface, center, and bottom of the tumor before PDT and SOED2 was obtained using the entire [3O2] spectra measured before and during the PDT. Based on the actual in vivo PDT protocols, two different ϕair of 50 or 75 mW cm−2 and various treatment times from 3000 to 7200 s were used for each SOED model. For [1O2]rx calculation using SOED1, the spatial distribution of ϕ in tumors obtained from the Monte-Carlo simulations and tissue optical properties (Qiu et al 2016a), initial Photofrin concentration ([S0]) measured before PDT, and mean [3O2]0 value were passed to the following three equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

For Photofrin-mediated PDT, low concentration correction parameter, δ = 33 μM, specific photobleaching ratio, σ = 7.6 × 10−5 μM−1, macroscopic 3O2 maximum perfusion rate, g = 0.7, 3O2 quenching threshold concentration, β = 11.9 μM, and specific 3O2 consumption rate, ξ = 3.7 × 10−3 cm2 s−1mW−1 (Wang et al 2010). For calculation of [1O2]rx using SOED2, equation (2) is not required as [3O2] spectra was explicitly measured throughout the course of PDT and it was directly used in equations (1) and (3) to calculate the total amount of [1O2]rx.

Fitting and simulation were performed using Matlab and COMSOL Multiphysics on an iMac OSX version 10.10.5 (processor 2.9 GHz Intel Core i5, 16 GB memory).

Kaplan–Meier curves for evaluation of the tumor local control rate

Tumor width (a) and length (b) were measured daily with slide calibers, and tumor volumes were calculated using formula V = π × a2 × b/6 (Busch et al 2009). Since initial tumor volumes at the time of PDT were not identical among mice, daily tracked volumes were scaled relative to a normalized volume of ~36.7 mm3 (the average of all initial tumor volumes). This process provided for consistent comparisons among the treatment groups. As light can penetrate 3–5 mm depth, PDT was performed at small tumor volumes to ensure complete treatment of the entire tumor, providing the potential for a curative response. A Kaplan–Meier curve for local control rate (LCR) was generated based on a V ⩽ 100 mm3 and stratified based on two dosimetry quantities of PDT dose, and [1O2]rx. A tumor volume of 100 mm3 was chosen as the endpoint because it enabled clear discrimination of tumor recurrence from treatment-induced inflammation.

Statistical analyses

Mann-Whitney tests were used to evaluate whether the PDT outcomes in each two independent groups (e.g. PDT-treated mice with RIF tumor on their shoulder, PDT-treated mice with tumor on their flank and controls) are significantly different from each other. Comparison of two survival curves was done using log rank test. Analyses were carried out using SPSS 14.0 (a subsidiary of IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) software and statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05 level (95% confidence level).

Results and discussions

Evaluation of the PDT outcome using PDT dose, SOED1 and SOED2

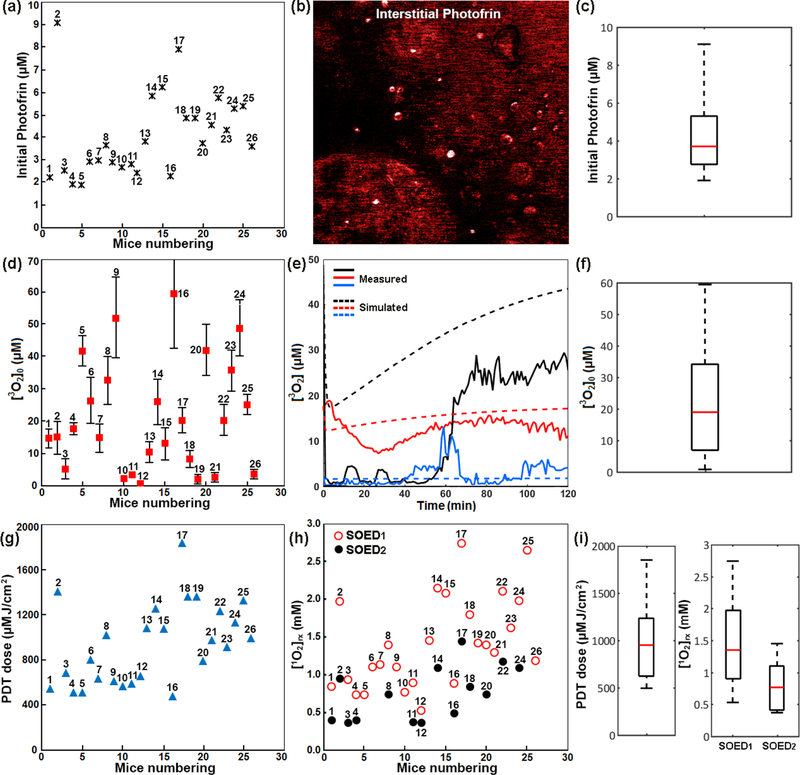

Increase in tumor size or tumor regrowth in some treated mice showed that Photofrin-mediated PDT did not lead to significant objective complete responses or long-term tumor control in all treated mice. The outcome could be attributed to spatial differences in interstitial Photofrin concentration, [3O2]0 and photochemical 3O2 consumption that results in insufficient [1O2]rx for tumor destruction. The measured initial Photofrin concentrations (black stars in figure 1(a)) and fluorescence images of the photosensitizer uptake by the tumors (see figure 1(b)) not only present a heterogeneous distribution within an individual tumor but also among the tumors in different mice. Box plot in figure 1(c) displays how the data is spread across the range. The height of the box represents interquartile range, where the top and bottom of the box are the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The redline near the middle of the box represents the median and the whiskers on either side of the interquartile range represent the lowest and highest quartiles of the data. There is no outlier in this data set.

Figure 1.

(a) Measured interstitial Photofrin concentration before PDT, and (b) a representative image of the photosensitizer uptake by a RIF tumor. Higher fluorescence signals in some regions and lack of the signals in other regions represent the heterogeneous distribution of Photofrin. (c) The statistical box plot of Photofrin distribution among the treated mice. The top and bottom of the box are the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The redline near the middle of the box represents the median and the whiskers on either side of the interquartile range represent the lowest and highest quartiles of the data. (d) Initial tissue oxygenation level measured before PDT ([3O2]0); the data for each mouse is a mean of three measurements on the surface, middle and bottom of the tumor with a standard deviation. (e) Measured (solid lines) and corresponding simulated (dashed lines with the same color) oxygen consumption spectra during PDT for three mice bearing RIF tumor on shoulder. (f) The statistical box plot of [3O2]0 distribution among the mice. (g) PDT dose and (h) reactive singlet oxygen concentration ([1O2]rx) calculated using SOED1 (incorporating [3O2]0) and SOED2 (incorporating the entire [3O2] spectra) for each treated mouse. (i) The statistical box plot of PDT dose and [1O2]rx distribution among the treated mice.

The measured [3O2]0 in three different depths (red squares with the standard deviation of the three measurements in figure 1(d)) and 3O2 consumption spectra (measured and simulated for three individual mice in figure 1(e)) during the treatment varied within a tumor and among the animals. The statistical box plot of [3O2]0 distribution is shown in figure 1(f).

As PDT dose is calculated based on the integral of ϕ and Photofrin concentration over time, PDT dose varied among the treated mice (see blue triangles figure 1(g)). Incorporating interstitial ϕ distribution, Photofrin concentration, and [3O2]0 in SOED1 or the entire [3O2] spectra in SOED2 also predicted different amounts of [1O2]rx generated during the PDT for each individual mouse (see figure 1(h)). It is here acknowledged that [1O2]rx values calculated using SOED1 (empty red circles) are different from those obtained using SOED2 (filled black circles) that accounts for the photochemical 3O2 consumption during the PDT. The statistical box plots of PDT dose distribution and [1O2]rx spread in SOED1 and SOED2 are shown in figure 1(i).

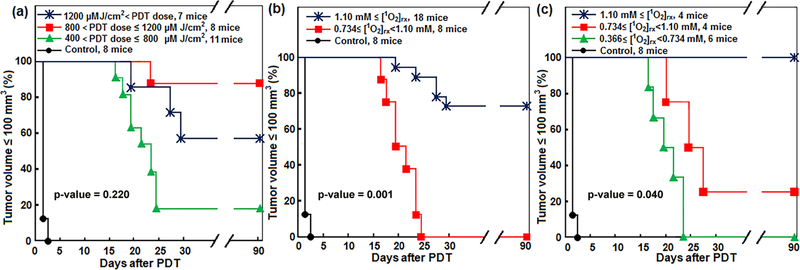

As shown in figure 2(a), Kaplan–Meier curves generated for LCR ⩽ 100 mm3 showed that ~87.5% of the mice treated with a PDT dose in the range of 800–1200 μM J cm−2 survived at 90 d post PDT; these mice did not show tumor regrowth within this period. However, the survival was ~57.1% for the mice treated with a higher PDT dose ⩾1200 μM J cm−2; this unexpected outcome result is partly due to the lack of 3O2 consumption information in this model. Photofrin-mediated PDT relies on its ability to generate [1O2]rx for tumor toxicity based on the mainly type II interaction of Photofrin, [3O2] and light. Figures 2(b) and (c) shows that dosimetry based on the amounts of [1O2]rx generated during the PDT allowed for reduced subject variation and improved treatment evaluation. PDT treatments that generate 1.1 mM ⩽ [1O2]rx showed the most effective results in the control of the tumor. Survival rate was 80% for [1O2]rx calculated using SOED1 (figure 2(b)) and 100% for [1O2]rx calculated using SOED2 (figure 2(c)). For SOED1 and SOED2, Log-rank test showed a statistically significant difference among different independent treated groups in all possible pairwise combinations; p-value was calculated to be 0.001 and 0.04 for figures 2(b) and (c), respectively. We expect that this bigger p-value for figure 2(c) is partly due to its smaller sample size (less number of mice). The maximum p-value of the considered differences between the treated groups was 0.220 (figure 2(a)), which was calculated for PDT dose.

Figure 2.

Survival curves for Photofrin-mediated PDT. The impact of (a) calculated PDT dose and (b) singlet oxygen concentration ([1O2]rx) obtained using initial tissue oxygenation ([3O2]0) immediately before PDT (SOED1) and (c) [1O2]rx obtained using the whole tissue oxygenation ([3O2]) spectra during PDT (SOED2) on the local control rate of RIF tumors within 90 d follow-up. The maximum p values are calculated using the Log-rank test to show statistical difference among different independent treated groups.

The effect of tissue oxygenation on the PDT efficacy

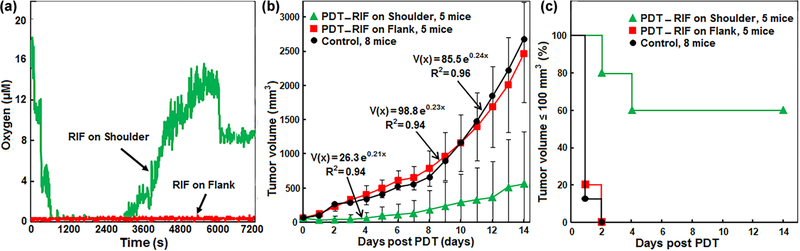

The role of the tissue [3O2] on the PDT efficacy was further tested by evaluating the regrowth rate and LCR of oxygenated RIF tumor on the shoulder as compared to hypoxic RIF tumors on flank treated with the same PDT protocol (ϕair = 50 mW cm−2 and total fluence = 250 J cm−2). Tumor hypoxia was achieved by use of a tourniquet to occlude blood flow to tumors (on the thigh) exclusively during light delivery for PDT. The changes of interstitial [3O2] in both groups of tumors have been shown in figure 3(a). Figure 3(b) shows the exponential tumor regrowth within the two weeks follow-up. Hypoxic RIF tumors did not show any improved treatment response as compared to the controls (Mann–Whitney p values = 0.94), whereas oxygenated tumors achieved ~60% LCR two weeks after the PDT (Mann–Whitney p values = 0.001). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves generated for LCR ⩽ 100 mm3 has been shown in figure 3(c) for both groups of mice as compared to the control (no Photofrin and no PDT).

Figure 3.

(a) Temporal changes of oxygen concentration ([3O2]) in a hypoxic radiation-induced fibrosarcoma (RIF) tumor on flank (red) and an oxygenated RIF tumor on shoulder (green) during Photofrin-mediated PDT for two representative mice. (b) Exponential tumor regrowth within two weeks follow up after PDT, and (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves generated for tumor volumes ⩽100 mm3. The tumors with no Photofrin and no photoexcitation were considered as control (black line). The green and red curves and symbols show the oxygenated (on shoulder) and hypoxic (on flank) tumors, respectively.

Conclusions

Although PDT is an established modality for the cancer treatment, the medical application of this technique has been limited due to the lack of dosimetry methods that can accurately account for all PDT component: photosensitizer, [3O2] and light. Our in vivo PDT suggested a substantial heterogeneity of Photofrin uptake (injected with the same amounts of photosensitizer) and [3O2] in RIF tumors that may account for the tumor regrowth and lack of PDT efficacy in some of the treated mice. Moreover, due to the heterogeneity of tissue [3O2] among the mice and different rate of 3O2 consumption during the PDT, the changes of [3O2] needs to be individually assessed for each mouse in order to estimate the mice population that show a complete response to the treatment. As a result, we proposed [1O2]rx calculated based on ϕ and explicit dosimetry of the photosensitizer concentration, and full spectra of [3O2] during PDT to predict complete tumor response and LCR. Assessing LCR across two dosimetry quantities of PDT dose, and [1O2]rx in RIF tumor model demonstrates that [1O2]rx is the most reliable dosimetry quantity for prediction of the Photofrin-mediated PDT outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Theresa M. Busch for providing Photofrin and advices on animal cares, and Radiobiology Division for providing OxyLite instrument for oxygen measurements. Special thanks to Dr Jay R Knutson from NHLBI, NIH for the use of his confocal microscope and helpful scientific discussions. This work is supported by grants R01 CA154562 and P01 CA87971 from National Institute of Health (NIH).

References

- Agostinis P et al. 2011. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update CA Cancer J. Clin 61 250–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch TM, Xing X, Yu G, Yodh A, Wileyto EP, Wang HW, Durduran T, Zhu TC and Wang KK 2009. Fluence rate-dependent intratumor heterogeneity in physiologic and cytotoxic responses to Photofrin photodynamic therapy Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 8 1683–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay JC, Conover DL, Hull EL and Foster TH 2001. Porphyrin bleaching and PDT-induced spectral changes are irradiance dependent in ALA-sensitized normal rat skin in vivo Photochem. Photobiol 73 54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn SM, Putt ME, Metz J, Shin DB, Rickter E, Menon C, Smith D, Glatstein E, Fraker DL and Busch TM 2006. Photofrin uptake in the tumor and normal tissues of patients receiving intraperitoneal photodynamic therapy Clin. Cancer Res 12 5464–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockel M and Vaupel P 2001. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects J. Natl Cancer Inst 93 266–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MM, Ghogare AA, Greer A and Zhu TC 2017. On the in vivo photochemical rate parameters for PDT reactive oxygen species modeling Phys. Med. Biol 62 R1–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk MS, Rohrbach D, Sunar U and Intes X 2014. Mesoscopic fluorescence tomography of a photosensitizer (HPPH) 3D biodistribution in skin cancer Acad. Radiol 21 271–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penjweini R, Liu B, Kim MM and Zhu TC 2015. Explicit dosimetry for 2-(1-hexyloxyethyl)-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a-mediated photodynamic therapy: macroscopic singlet oxygen modeling J. Biomed. Opt 20 128003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penjweini R, Loew HG, Breit P and Kratky KW 2013. Optimizing the antitumor selectivity of PVP-Hypericin re A549 cancer cells and HLF normal cells through pulsed blue light Photodiagnos. Photodyn. Ther 10 591–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penjweini R, Kim MM, Finlay JC and Zhu TC 2016a. Investigating the impact of oxygen concentration and blood flow variation on photodynamic therapy Proc. SPIE 9694 96940L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penjweini R, Kim MM, Liu B and Zhu TC 2016b. Evaluation of the 2-(1-Hexyloxyethyl)-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide (HPPH) mediated photodynamic therapy by macroscopic singlet oxygen modeling J. Biophoton 9 1344–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H et al. 2017. A comparison of dose metrics to predict local tumor control for Photofrin-mediated photodynamic therapy Photochem. Photobiol 93 1115–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Kim MM, Penjweini R and Zhu TC 2016a. Macroscopic singlet oxygen modeling for dosimetry of Photofrin-mediated photodynamic therapy: an in vivo study J. Biomed. Opt 21 88002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Kim MM, Penjweini R and Zhu TC 2016b. Dosimetry study of PHOTOFRIN-mediated photodynamic therapy in a mouse tumor model Proc. SPIE 9694 96940T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi I, Anbil S, Alagic N, Celli J, Zheng L Z, Palanisami A, Glidden MD, Pogue BW and Hasan T 2013. PDT dose parameters impact tumoricidal durability and cell death pathways in a 3D ovarian cancer model Photochem. Photobiol 89 942–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel P, Fortmeyer HP, Runkel S and Kallinowski F 1987. Blood flow, oxygen consumption, and tissue oxygenation of human breast cancer xenografts in nude rats Cancer Res. 47 3496–503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HW, Rickter E, Yuan M, Wileyto EP, Glatstein E, Yodh A and Busch TM 2007. Effect of photosensitizer dose on fluence rate responses to photodynamic therapy Photochem. Photobiol 83 1040–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KK, Finlay J C, Busch TM, Hahn SM and Zhu TC 2010. Explicit dosimetry for photodynamic therapy: macroscopic singlet oxygen modeling J. Biophotonics 3 304–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams JH, Macrobert AJ and Bown SG 2007. The role of oxygen monitoring during photodynamic therapy and its potential for treatment dosimetry Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 6 1246–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Aslan K, Previte MJ and Geddes CD 2008. Plasmonic engineering of singlet oxygen generation Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 1798–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu TC, Liu B and Penjweini R 2015. Study of tissue oxygen supply rate in a macroscopic photodynamic therapy singlet oxygen model J. Biomed. Opt 20 38001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]