Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to assess the magnitude and determinants of road traffic accidents (RTAs) in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was done using a simple random sampling technique.

Setting

The study was done in Mekelle city from February to June 2015.

Participants

The study was done among drivers settled in Mekelle city.

Main outcome measures

The main outcome measure was occurrence of RTA within 2 years. A binary logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with RTA.

Results

The magnitude of RTA was found to be 23.17%. According to the drivers’ perceived cause of the accident, 22 (38.60%) of the accident was due to violation of traffic rules and regulations. The majority of the victims were pedestrians, 19 (33.33%). Drivers who were driving a governmental vehicle were 4.16 (adjusted OR (AOR) 4.16; 95% CI 1.48 to 11.70) times more likely to have RTA compared with those who drive private vehicles. Drivers who used alcohol were 2.29 (AOR 2.29; 95% CI 1.08 to 4.85) times more likely to have RTA compared with those drivers who did not consume alcohol.

Conclusion

Magnitude of reported road traffic accident was high. Violation of traffic laws, lack of vehicle maintenance and lack of general safety awareness on pedestrians were the dominant reported causes of RTAs. Driving a governmental vehicle and alcohol consumption were the factors associated with RTA. Monitoring blood alcohol level of drivers and regular awareness to the drivers should be in place. Holistic study should be done to identify the causes of RTAs.

Keywords: road traffic accident, drivers, Mekelle city, tigray, Ethiopia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data quality was assured under close supervision of the principal investigators.

Appropriate statistical methods were used to present the findings of the study.

Cross-sectional study design does not allow establishing causality.

The analysis of this study misses some important variables like quality of the vehicles and road safety.

There may be recall bias on the road traffic accidents occurrences.

Introduction

Road traffic accident (RTA) is an accident, which occurs or originates on a way or street open to public traffic; resulting in one or more persons being killed or injured, and at least one moving vehicle is involved. RTA includes collisions between vehicles, vehicles and pedestrians and vehicles and animals or fixed obstacles.1 RTA contributes to poverty by causing loss of productivity, material damage, injuries, disabilities, grief and deaths.2 Deaths and injuries resulting from road traffic crashes remain a serious problem globally and current trends suggest that this will continue to be the case in the foreseeable future.3 4 RTA is the major cause of economic loss globally. The total costs to public services identified as follows: older drivers, £63 million (£10 000 per fatality); people driving for work, £702 million (£700 000 per fatality); motorcyclists, £1.1 billion (£800 000 per fatality) and young drivers, £1.3 billion (£1.1 million per fatality).5

Approximately 1.3 million people die each year in traffic-related accidents worldwide.6 Road traffic injury is now the leading cause of death for children and young adults aged 5–29 years, signalling a need for a shift in the current child health agenda. It is the eighth-leading cause of death for all age groups exceeding HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and diarrhoeal diseases7 and the deaths due to RTAs are predicted to become the fifth-leading cause of death by the year 2020.6

The burden of road traffic injuries and deaths is disproportionately borne by vulnerable road users and those living in low-income and middle-income countries, where the growing number of deaths is fuelled by transport that is increasingly motorised. Between 2013 and 2016, no reductions in the number of road traffic deaths were observed in any low-income country.2 Although road infrastructures have a significant role in the occurrence of RTA, the human factor is the most prevalent contributing factor of RTAs. This includes both driving behaviour (eg, drinking and driving, speeding, traffic law violations) and impaired skills (eg, lack of attention, exhaustion, physical disabilities and so on).8

Poor conditions of quality of vehicles and less road safety are determinant factors for RTA in Africa9 including Ethiopia.10 WHO in 2011 reported that RTA in Ethiopia reached 22 786 which accounted for 2.77% of all the deaths. The report showed that RTA is the ninth killer health problem in the country. RTA makes Ethiopia 12th and 9th in the world and in Africa, respectively.11 Mekelle is a fast growing regional city, which has a heavy traffic flow, especially during peak hours.12 In Mekelle city, it was reported that RTA is increasing from year to year and it was shown that 96% of the causes were related to human risky behaviour whereas 4% was due to vehicle-related factors.12 13 However, despite the growing magnitude of RTAs in the city, there is paucity of data on determinants of RTAs among drivers. In addition, to that the study can have significant role to fill the lack of data as there is lack of reliable data although it is a serious problem in most of the low-income and middle-income countries.14 Hence, this study was conducted to assess the magnitude and determinants of RTAs among drivers in Mekelle city, Tigray, Ethiopia. This study can have a significant role in supplementing and informing the current status in achieving the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3.6 for a reduction in the number of deaths by half by 2020.15

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted among drivers in Mekelle city, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia from February to June 2015. Mekelle is the capital city of the Tigray regional state which is found at 783 Km north of the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Regarding road infrastructure: Mekelle city has 55 km asphalted, 23 km cobble stone and 152 km gravel road.16

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was used.

Participants

All drivers who were based in Mekelle city with a legal driving licence and who were driving taxi, Bajaj (three wheel taxi), private owned car and governmental car in Mekelle city were included in the study. Heavy truck drivers, drivers who were not working and sick during the study period, those who drive more than two vehicle types and those who came from other areas to Mekelle city were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated from a previous study, where the prevalence of RTA was reported, p=22% in Mekelle city.12 Using 5% marginal error and 95% CI by the following formula: n= (Zα/2)2 P (P-1)/D2

Where n=minimum sample size required

Z=standard score corresponding to 95% CI

p=assumed proportion of drivers

D=margin of error (precision) 5%

n=3.84×0.1716/0.0025=263

Since the source population was less than 10 000(ie, 1500), sample size correction formula was used: nf=n/1+ (n/N)

Where nf=desired sample size

n=calculated sample size

n=total population

nf=n/1+ (n/N)=263/1+ (263/1500)=263/1.175=223.8~224

By adding 10% contingency for non-response, the sample size was 224+22=246.

Sampling procedures

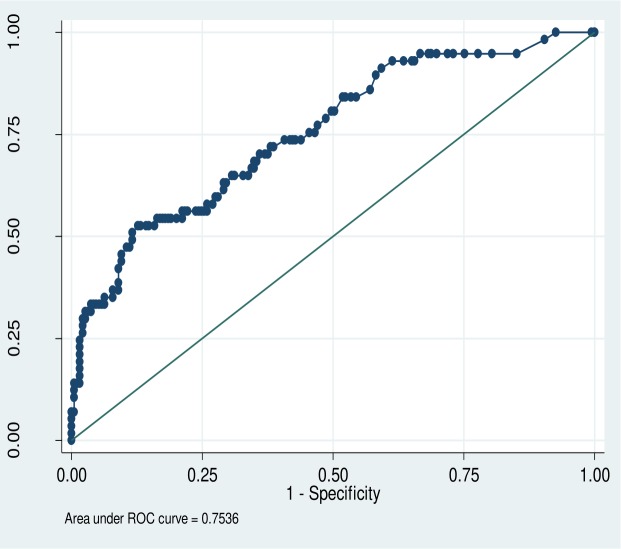

A sampling frame was constructed by a vehicle plate number, which was obtained from Mekelle city transport office. The frame was subcategorised based on the type of the vehicle as a taxi, Bajaj, governmental vehicles and private/house vehicles. Subsamples were calculated for each category of vehicles proportional to the number of vehicles in the respective categories. Then, study subjects were selected using simple random sampling method (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sampling procedure. Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure.

Data collection procedures and tools

The study subjects (drivers) were traced and interviewed for data collection. The drivers were traced at their destination for taxi and Bajaj, house cars in their working area and governmental cars at their offices using the car plate number. A structured interviewer administered questionnaire, adapted from different literatures, was used. The questionnaire was initially prepared in English and was translated into the local language Tigrigna. The instrument included: sociodemographic characteristics of drivers, risky behaviours factors and other variables which has a bearing on RTA. Trained data collectors and supervisors handled the data collection process.

Patient and public involvement

Drivers in Mekelle city were involved in the study.

Data quality control

Pre-est was done on 5% of the sample at Adigrat town, Tigray region. Based on the pretest findings, necessary corrections were made to the questionnaire. Adequate supervision was undertaken by the supervisors and principal investigator during the data collection. Daily spot-checking of the filled questionnaires for errors or any incompleteness was done by the supervisors and the principal investigator.

Data management and analysis

The collected data were entered and cleaned in Microsoft excel 2007. Then, the data were exported and analysed using STATA V.12. Values of categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. All statistical tests were performed at the 5% significance level.

The dependent variable was a occurrence RTA within 2 years which was dichotomised into yes (labelled ‘1’) and no (labelled ‘0’). To prevent recall bias respondents were reinforced to remember the occurrence of RTA in the previous 2 years. Each independent variable was cross-tabulated and further evaluated for association in the bivariate binary logistic regression. Finally, variables significant in the bivariate analysis were entered into multivariable binary logistic regression analysis to identify determinants of RTA. Variables on risky behaviours, traffic safety rules and some other personal characteristics were used to interpret the adjusted OR (AOR) in the multivariate analysis under the adjustment of the sociodemographic variables. The final model was developed using a stepwise logistic regression.

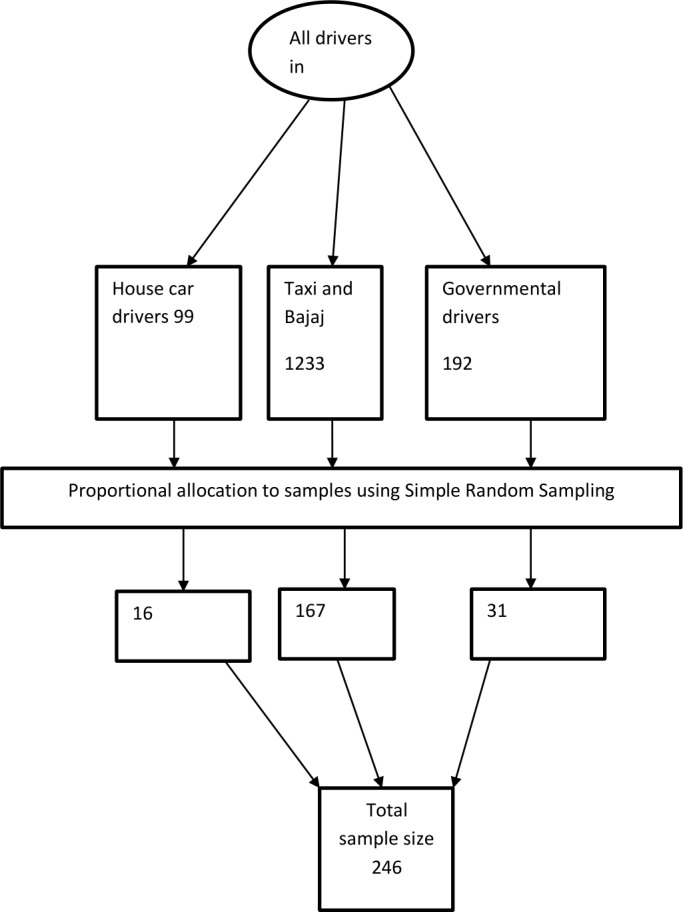

The confounding effect of the explanatory variables was checked using forward and backward elimination techniques and any variable above 20% change of coefficient was considered as a confounder. Multicollinearity was checked using variance inflation factor (VIF) at a cut-off value of 10. Variables with greater than 10 VIF value were handled by removing the most intercorrelated variable(s) from the model and substitute their cross product as an interaction term. Final model fitness was checked using the Hosmer-Lemeshow method. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to show how much the independent variables in the final model predicted the dependent variable.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents

The response rate was 100%. The median (IQR) age of the respondents was 30 (10) years. The majority of study participants (98.37%) were males. Regarding the marital status of the respondents, 102 (41.46%), 101 (41.06%), 30 (12.20%) and 13 (5.28%) were divorced, married, single and widower, respectively. The majority of the drivers, 170 (69.11%) were Christian Orthodox, followed by Muslims, 54 (21.95%). With regard to their educational status, 225 (91.46%) had attained at least grade 5. The median (IQR) monthly income (in Birr) of the study participants was 1000 (1200) (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics of drivers in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia, 2015

| Variable | Category | RTA occurrence/s | P value | Total n (%)/median (IQR) | |

| No n (%)/median (IQR) | Yes n (%)/median (IQR) | ||||

| Age in years | Median (IQR) | 29 (26–34) | 35 (28–41) | – | 30 (26–36) |

| Monthly income in Birr | Median (IQR) | 1000 (700–1800) | 1500 (1000–2300) | – | 1000 (800–2000) |

| Sex | Male | 186 (98.41) | 56 (98.25) | 0.93 | 242 (98.37) |

| Female | 3 (1.59) | 1 (1.75) | 4 (1.63) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 74 (39.15) | 27 (47.37) | 0.004 | 101 (41.06) |

| Single | 88 (46.56) | 14 (24.56) | 102 (41.46) | ||

| Divorced | 21 (11.11) | 9 (15.79) | 30 (12.20) | ||

| Widowed | 6 (3.17) | 7 (12.28) | 13 (5.28) | ||

| Religion | Orthodox | 139 (73.54) | 31 (54.39) | 0.031 | 170 (69.11) |

| Muslim | 37 (19.58) | (17)29.82 | 54 (21.95) | ||

| Protestant | 4 (2.12) | 4 (7.02) | 8 (3.25) | ||

| Catholic | 9 (4.76) | 5 (8.77) | 14 (5.69) | ||

| Educational status | Illiterate | 13 (6.88) | 4 (7.02) | 0.644 | 17 (6.91) |

| Primary (grade 1–4) | 2 (1.06) | 2 (3.51) | 4 (1.63) | ||

| Secondary (grade 5–10) | 94 (49.74) | 27 (47.37) | 121 (49.19) | ||

| Above 10 | 80 (42.33) | 24 (42.11) | 104 (42.28) | ||

| Ethnicity | Tigray | 178 (94.18) | 44 (77.19) | 0.000 | 222 (90.24) |

| Amhara | 10 (5.29) | 7 (12.28) | 17 (6.91) | ||

| Afar | 1 (0.53) | 6 (10.53) | 7 (2.85) | ||

n=246.

RTA, road traffic accident.

Magnitude of RTAs

Among all the drivers, 57 (23.17%) had encountered RTA in the past 2 years from the time of the current study. Most of the accidents happened on Monday, 22 (38.60%) and Friday, 13 (22.81%) even though accidents were reported in all the 7 days. About 22/57 (38.60%), 13/57 (22.81%), 10/57 (17.54%) and 9/57 (15.79%) of the reported causes of RTAs were due to violation of traffic laws, lack of vehicle maintenance, lack of general safety awareness on pedestrians and violation of speed limit. A significant number of the accidents, 25/57 (43.86%) happened at dawn. Pedestrians and cyclists constituted the major share of the RTA victims, 31/57 (54.40%). About three-fourths of the accidents, 43/57 (75.44%) happened at either T-junction road or cross road (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and setting of RTA in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia, 2015

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

| Accident experience in the previous 2 years | Yes | 57 | 23.17 |

| No | 189 | 76.83 | |

| Type of accident | Injury | 29 | 50.88 |

| Injury and property damage | 14 | 24.56 | |

| Property damage | 8 | 14.0 | |

| Death | 6 | 10.5 | |

| Light condition | At dawn | 41 | 71.93 |

| Day time | 16 | 28.07 | |

| Victim | Pedestrian | 19 | 32.14 |

| Cyclist | 12 | 21.43 | |

| Passenger | 14 | 25.00 | |

| Driver | 12 | 21.43 | |

| Accident site road | T-junction | 15 | 26.32 |

| Cross road | 28 | 49.12 | |

| Straight road | 14 | 24.56 | |

| Day of accident | Monday | 22 | 38.60 |

| Tuesday | 4 | 7.02 | |

| Wednesday | 6 | 10.53 | |

| Thursday | 3 | 5.26 | |

| Friday | 13 | 22.81 | |

| Saturday | 9 | 15.79 | |

| No of accidents (life time experience) | 1 | 42 | 73.68 |

| 2 | 12 | 21.05 | |

| 3 | 3 | 5.26 | |

| Reason for the accident | Lack of general safety awareness of pedestrians | 10 | 17.54 |

| Violation of traffic rules and regulations | 22 | 38.60 | |

| Violation of speed limit | 9 | 15.79 | |

| Lack of vehicle maintenance | 13 | 22.81 | |

| Did not remember | 3 | 5.26 |

n=246.

RTA, road traffic accident.

Risky driving behaviours, infrastructure setup and practices

Concerning risky driving behaviours, 92 (37.40) of the drivers drunk alcohol before driving. About 43 (17.48%) of the drivers were chat chewers and 30 (12.20%) were smokers. More than one-third of the drivers, 96 (39.02%) ever reported that they used cell phone for communication while driving. The prevalence of RTA among drivers was 3.29%, 32.6%, 36.7%, 18.5% and 21.6% among cell phone users, alcohol consumers, chat chewers, cigarette smokers and seat belt users while driving respectively. However, the prevalence of RTA among the drivers who do not use cell phone and seat belt were 17.33% and 30.9% respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Risky driving behaviours, infrastructure setup and practices among drivers in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia, 2015

| Variables | Category | RTA | Total (%) | P value | |

| Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

||||

| Cell phone use while driving | Yes | 31 (32.29) | 65 (67.71) | 96 (39.02) | 0.007 |

| No | 26 (17.33) | 124 (82.67) | 150 (60.98) | ||

| Substance use | Alcohol | 14 (32.6) | 29 (67.4) | 92 (37.40) | 0.026 |

| Chat | 11 (36.7) | 19 (63.3) | 43 (17.48) | ||

| Cigarette | 32 (18.5) | 141 (81.5) | 30 (12.20) | ||

| Seat belt use | Yes | 44 (21.6) | 160 (78.4) | 204 (82.93) | 0.189 |

| No | 13 (30.9) | 29 (69.0) | 42 (17.07) | ||

| What do you do when another vehicle tries to pass you? | I advise him to slow down | 4 (12.5) | 28 (87.5) | 32 (13.01) | 0.028 |

| I give him priority | 42 (29.2) | 102 (70.8) | 144 (58.54) | ||

| I speed up | 11 (15.71) | 59 (84.29) | 70 (28.46) | ||

| Road infrastructure | Gravel | 5 (16.7) | 25 (83.3) | 30 (12.2) | 0.117 |

| Asphalt | 39 (28.1) | 100 (71.9) | 77 (31.3) | ||

| Cobble stone | 13 (16.9) | 64 (83.1) | 139 (56.5) | ||

| Service provision of the vehicle as per the manufacturer recommendation | No | 3 (5.26) | 6 (3.17) | 9 (3.66) | 0.462 |

| Yes | 54 (94.74) | 183 (96.83) | 237 (96.34) | ||

| Visual impairment | No | 180 (95.24) | 53 (92.980 | 233 (94.72) | 0.505 |

| Yes | 9 (4.76) | 4 (7.02) | 13 (5.28) | ||

| No violation rule for the speed limit | No | 7 (3.70) | 5 (8.770 | 12 (4.880 | 0.119 |

| Yes | 182 (96.30) | 52 (91.23) | 234 (95.12) | ||

| Listen radio while driving | No | 47 (22.81) | 13 (24.87) | 60 (24.39) | 0.751 |

| Yes | 142 (75.13) | 44 (77.19) | 186 (75.61) | ||

| What did you do in heavy traffic? | Either pass or stay | 1 (0.53) | 2 (3.51) | 3 (1.22) | 0.069 |

| Pass fast | 10 (5.29) | 6 (10.53) | 16 (6.50) | ||

| Slow speed | 178 (94.18) | 49 (85.96) | 227 (92.28) | ||

| Ever received a ticket, citation or warning for any traffic violation | No | 113 (59.79) | 27 (47.37) | 140 (56.91) | 0.097 |

| Yes | 76 (40.21) | 30 (52.63) | 106 (43.09) | ||

n=246.

Factors associated with RTAs

In the bivariate analysis age, being married, being single, driving governmental vehicle, alcohol use, other substances other than alcohol use, cell phone use during driving, drivers’ years of experience and vehicle service were significantly associated with RTAs at 95% CI. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis showed that drivers who drove after consuming alcohol were 2.29 (AOR 2. 29; 95% CI 1.08 to 4.85) times more likely to have RTA compared with drivers who did not consume alcohol. Drivers who drove governmental vehicles were 4.16 (AOR 4. 16; 95% CI 1.48 to 11.70) times more likely to have RTA compared with drivers of privately owned vehicles. As the driver’s experience increased by 1 year, the probability of RTA decreased by 26% (AOR 0. 74; 95% CI 0.60 to 0.90) (table 4).

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariable regression analysis of RTA with the predictors in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia, 2015

| Variables | Category | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| Age | 0.08 (0.041 to 0.121)* | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | |

| Marital status | Married | 0.85 (0.348 to 2.086)* | 1.62 (0.60 to 4.39) 0.94 (0.25 to 3.45) 1 (ref.) |

| Single | 0.37 (0.141 to 0.972)* | ||

| Divorced | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Widower | 2.72 (0.711 to 10.408) | ||

| Religion | Protestant | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) 0.24 (0.05 to 1.26) |

| Orthodox | 0.22 (0.052 to 0.940)* | ||

| Muslim | 0.45 (0.102 to 2.059) | ||

| Catholic | 0.55 (0.095 to 3.245) | ||

| Ethnicity | Afar | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) 0.04 (0.005 to 0.58)* |

| Amhara | 0.12 (0.011 to 1.195) | ||

| Tigray | 0.04 (0.004 to 0.351)* | ||

| Vehicle ownership | Private (driver is employee) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) 4.16(1.48 to 11.70)* 1.64 (0.71 to 3.339) |

| Governmental | 3.5 (1.464 to 8.168)* | ||

| Driver (driver is the owner) | 2.38 (1.225 to 4.660)* | ||

| Licence grade | First | 1 (ref.) | |

| Third | 1.36 (0.329 to 5.632) | ||

| Fourth | 0.55 (0.138 to 2.241) | ||

| Special | 1.52 (0.249 to 9.294) | ||

| Alcohol use | No | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) 2.29 (1.08 to 4.85)* |

| Yes | 1.88 (1.034 to 3.437)* | ||

| Substance use other than alcohol | Chat | 2.12. (1.010 to 4.478)* | 2.18 (0.78 to 6.05) 1.11 (0.39 to 3.18) 1 (ref.) |

| Cigarette | 2.55 (1.105 to 5.884)* | ||

| I do not use | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Cell phone use while driving | No | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) 1.80 (0.86 to 3.74) |

| Yes | 2.27 (1.246 to 4.150)* | ||

| Use seat belt while driving | No | 1 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 0.61 (0.29 to 1.28) | ||

| Income | 1.00 (0.999 to 1.000) | ||

| Distance travelled | 1.00 (0.999 to 1.005) | ||

| Driver’s experience | 0.86 (0. 749 to 0.999)* | 0.74 (0.60 to 0.90)* | |

| Nor of vehicle service since the date of the vehicle manufactured | 1.24 (1.103 to 1.398)* | 1.18 (0.99 to 1.40) | |

| Road infrastructure | Gravel | 1 (ref.) | |

| Cobble stone | 1.02 (0.33 to 3.14) | ||

| Asphalt | 1.95 (0.70 to 5.46) | ||

| Service provision of the vehicle as per the manufacturer recommendation | No | 1 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 0.59 (0.14 to 2.44) | ||

| Visual impairment | No | 1 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.51 (0.45 to 5.10) | ||

| No violation rule for the speed | No | 1 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 0.40 (0.12 to 1.31) | ||

| Listen radio while driving | No | 1 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.12 (0.56 to 2.26) | ||

| What did you do in heavy traffic? | Either pass or stay | 1 (ref.) | |

| Pass fast | 0.30 (0.02 to 4.06) | ||

| Slow speed | 0.14 (0.01 to 1.55) | ||

| Ever received a ticket, citation, or warning for any traffic violation | No | 1 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.65 (0.91 to 3.00) |

n=246.

*P<0.05.

RTA, road traffic accident.

The residuals were checked for influential outlier observations and the result showed that there were no suspicious influential outlier observations. Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed a χ2 value of 9.41 (p=0.3085) which is greater than 0.05. The null hypothesis is not to be rejected, which implies that the model estimates adequately to fit the data at an acceptable level. The area under ROC curve was 0.7536 (see figure 2). The predicting power of the independent variables for the dependent variable was 75.36%. Therefore, it can be concluded that the model fits the data reasonably well. No confounding factor was found.

Figure 2.

ROC curve predicting power of the independent variables for the dependent variable. ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Discussion

The main aim of the study was to assess the magnitude and determinants of RTAs among drivers in Mekelle city, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. This study showed 23.17% of the drivers have reported having RTA in the previous 2 years. Ownership of the vehicles, driving after taking alcohol, driver’s experience, used cell phone while driving were the determinants for RTAs among the drivers.

The study revealed that the magnitude of self-reported RTA in Mekelle city was 23.17%. There was a slight increment of accidents in this study compared with the previous study done in Mekelle city, which showed that the prevalence of RTA was 22%.12 However, it is lower when compared with a similar study conducted in the same city among taxi drivers with four wheels, of which 26.4% of them reported RTA encounter within the past 3 years.17 This variation might be due to the fact that the city is expanding where the population size is increasing. Or it might be due to the differences in the RTAs report period where the current study included reports of RTA in the past 2 years from the time of the study. About three-fourths (75.44%) of the accidents of this study, happened at either T-junction or cross roads. The finding of this study is higher as compared with recent statistics from USA and India which showed, approximately 55% of the total traffic crashes and 23% of crashes with fatalities in urban areas in the USA occur at intersections and approximately 32% of urban traffic crashes take place at intersections in India.18 This difference might be due to infrastructure differences like traffic lights in the intersections of the roads. Because traffic signals do help to prevent collisions if obeying for traffic rules by the drivers.19 In this study about 22/57 (38.60%), 13/57 (22.81%), 10/57 (17.54%) and 9/57 (15.79%) of the reported causes of RTAs were due to violation of traffic laws, lack of vehicle maintenance, lack of general safety awareness on pedestrians and violation of speed limit. This finding is similar with the study on the comparative analysis of literature concerning road safety, which showed that the causes include: lack of control and enforcement concerning implementation of traffic regulation (primarily driving at excessive speed, driving under the influence of alcohol and not respecting the rights of other road users (mainly pedestrians and cyclists), lack of appropriate infrastructure and unroadworthy vehicles.20 This is because, obeying traffic laws are designed to protect the drivers and other people, animals or from destruction of properties around the road and it self the road. In other words by knowing the rules of the road, practising good driving skills and generally taking care as a road user can help a vital role in preventing a crash.

This study identified that ownership of the vehicles was found to be predictor of RTA. RTA was 3.78 times more likely among those who drove governmental vehicles. A study on Arab gulf countries as compared with other countries showed that vehicle ownership levels and safety parameters in both developed and low-income and middle-income countries is presented to highlight the relative seriousness of the road safety situation in different countries.14 The possible justification for this to be happen might be due to the fact that governmental drivers might violate the traffic rules and speed up to arrive timely at workplace especially at the peak hours.

This study revealed that driving after taking alcohol was found to be an aggravating factor for RTA. Drivers who drove after consuming alcohol were 2.29 more likely to have RTA compared with those who do not consume alcohol. This finding is similar to a similar study which showed that individuals who drank alcohol were 3.2 times more likely to encounter RTA.21 It was also supported by the Great Britain department for Transport provisional estimates for 2013 which showed that between 230 and 290 people were killed in accidents in Great Britain where at least one driver was over the drink drive limit.22 Another study also showed that impairments from alcohol was associated with traffic accident of crashes and deaths.23 24 This might be due to the nature of alcohol that has a range of psychomotor and cognitive effects, including attitude, judgement, vigilance, perception, reaction and controlling.25 This can increase accident risk by lowering cognitive processing, coordination, attention, vision and hearing.

This study has also revealed that as driver’s experience increases by 1 year, the probability of getting RTA decreased by 26 percent. This finding was similar to the finding of a study in 2003 which showed that as the drive miles and experience increases, the probability of self-reported crash decreased.26 This might be due to the anticipation of potentially hazardous traffic situations, which require years of practice.

The likelihood of RTA was 1.8 times higher among drivers who used cell phone while driving compared with these who do not use. This study is consistent with a previously done study in Mekelle city.17 Other studies have also reported that drivers distracted by mobile devices such as smartphones and/or other in-vehicle devices are at risk for a serious negative outcomes.27–29 A similar study indicated that telephone use while driving increases the likelihood of RTA/crash by a factor of four, while texting by around 23 times.30 This is because of loss of attention to surroundings while driving.

The findings of this study showed visual impairment was not found to be a predictor variable for RTA. But a study done in Ibadan town Nigeria showed that drivers who had visual impairment were 1.6 times more likely to encounter RTA.31 Therefore, this needs further investigation.

The strength of this study is that data quality was assured under close supervision of the principal investigators during both data entry and data collection time. Appropriate statistical methods were used to present the findings of the study. Despite this strength, the study has certain limitations. Due to cross-sectional study design nature, establishing causality is not possible. In addition to that, there may be recall bias and the analysis of this study misses some important variables like quality of the vehicles and road safety.

Conclusion

The magnitude of RTA was high. The intersections of the roads were the main cause of RTAs. Violation of traffic laws, lack of vehicle maintenance and lack of general safety awareness on pedestrians were the dominant reported causes of RTAs. Driving a governmental vehicle and alcohol consumption were the factors associated with RTA. Monitoring blood alcohol level of drivers should be in place. Education on traffic laws and regulations should be given to drivers on regular basis. In addition to that a holistic study should be done to identify the causes of RTA. Due to the similarities of the cities in North Ethiopia, this study can represent to other cities in Northern Ethiopia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are glad to extend our gratitude to the data collectors and participants of the study. We would like to extend our gratitude to Mekelle University as well for funding the research.

Footnotes

Contributors: ABW conceptualised and designed the study, involved in data analyses, acquisition of data, tabulating the data, interpretation of data, preparing tables and figures, and critically revising the manuscript. AAD and TWW have involved in interpretation of data, Supervision, administration, drafting the initial manuscript and critically revising the manuscript. AAD has primary responsibility for final content and involved in final review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Mekelle University for research and community services.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical clearance and approval was given by Mekelle University, school of public health Ethical Review Committee with the approval number of ERC 0017/2014.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. The dataset of the study findings is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Health statistics 2019 definitions, sources and methods, 2019. Available: file:///C:/Users/lenovo/Downloads/HEALTH_STAT_11_Injuries%20in%20road%20traffic%20accidents.pdf [Accessed 24 Nov 2019].

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) Global status report on road safety. Geneva: WHO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO Projections of mortality and causes of death, 2015 and 2030. Geneva: WHO, 2013. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/ [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018;392:2052–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clifford J, THEOBALD C, Atkinson S. Evaluating the costs of incidents from the public sector perspective: a road safety policy research paper, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO Global plan: decade of action for road safety 2011-2020. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO Global health expenditure database. Geneva: WHO, 2018. http://apps.who.int/nha/database [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nabi H, Consoli SM, Chastang J-F, et al. Type A behavior pattern, risky driving behaviors, and serious road traffic accidents: a prospective study of the GAZEL cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:864–70. 10.1093/aje/kwi110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abuhamoud MAA, Rahmat RAOK, Ismail A. Transportation and its concerns in Africa: a review. The Social Sciences 2011;6:51–63. 10.3923/sscience.2011.51.63 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO World health rankings : Live longer live better. Geneva: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. WHO World health rankings : Live longer live better. Genevea: WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hassen A, Godesso A, Abebe L, et al. Risky driving behaviors for road traffic accident among drivers in Mekele City, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:535 10.1186/1756-0500-4-535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mekelle Town Police Commission Office Report on road traffic accident Mekele. Mekelle: Police commission, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bener A, Abu-Zidan FM, Bensiali AK, et al. Strategy to improve road safety in developing countries. Saudi Med J 2003;24:603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. United Nations Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mekelle City Administration Free traffic ranks. Mekelle: Mekelle City administration, 2019. http://mekelleadministration.gov.et.rankank.com [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asefa NG, Ingale L, Shumey A, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with road traffic crash among TAXI drivers in Mekelle town, Northern Ethiopia, 2014: a cross sectional study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0118675 10.1371/journal.pone.0118675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khan MA, Agarwal PK, Chaki S. Strategies for safety evaluation of road intersection to have sustainable development. Journal of Advanced Research in Automotive Technology and Transportation System 2017;2:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rhythm Engineering 7 traffic signal myths Debunked. Available: https://rhythmtraffic.com/7-traffic-signal-myths-debunked/

- 20. Goniewicz K, Goniewicz M, Pawłowski W, et al. Road accident rates: strategies and programmes for improving road traffic safety. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2016;42:433–8. 10.1007/s00068-015-0544-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Connor J, Norton R, Ameratunga S, et al. The contribution of alcohol to serious CAR crash injuries. Epidemiology 2004;15:337–44. 10.1097/01.ede.0000120045.58295.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Great Britain Department for Transport Estimates for reported road traffic accidents involving illegal alcohol levels: 2013 (second provisional) self-reported drink and drug driving for 2013/14. London: Great Britain Department for Transport, 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/402698/rrcgb-drink-drive-2013-prov.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shinar D. Traffic safety and human behavior. 2nd edition Beersheba, Israel: Ben Gurion University of the Negev, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brown T, Milavetz G, Murry DJ, Alcohol MDJ. Alcohol, drugs and driving: implications for evaluating driver impairment. Ann Adv Automot Med 2013;57:23–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao X, Zhang X, Rong J. Study of the effects of alcohol on drivers and driving performance on straight road. Math Probl Eng 2014;2014:1–9. 10.1155/2014/607652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rolison JJ, Regev S, Moutari S, et al. What are the factors that contribute to road accidents? an assessment of law enforcement views, ordinary drivers' opinions, and road accident records. Accid Anal Prev 2018;115:11–24. 10.1016/j.aap.2018.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lipovac K, Đerić M, Tešić M, et al. Mobile phone use while driving-literary review. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav 2017;47:132–42. 10.1016/j.trf.2017.04.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Caird JK, Willness CR, Steel P, et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of cell phones on driver performance. Accid Anal Prev 2008;40:1282–93. 10.1016/j.aap.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Horrey WJ, Wickens CD. Examining the impact of cell phone conversations on driving using meta-analytic techniques. Hum Factors 2006;48:196–205. 10.1518/001872006776412135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farmer CM, Braitman KA, Lund AK. Cell phone use while driving and attributable crash risk. Traffic Inj Prev 2010;11:466–70. 10.1080/15389588.2010.494191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bekibele CO, Fawole OI, Bamgboye AE, et al. Risk factors for road traffic accidents among drivers of public institutions in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Health Sci 2007;14:137–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.