Black Americans face greater risk and incidence across many cancers (e.g., breast, prostate, stomach, colorectal), higher death rates, and shortest survival of any racial or ethnic group (American Cancer Society, 2018; National Cancer Institute, 2018). Health disparities contribute significantly to cancer diagnoses and outcomes for Black Americans, including genetic and biological differences, less access to education, or reduced quality care for the poor and medically underserved. Even when socioeconomic status is high and access to care is available, cultural differences can promote mistrust with providers and health care systems. These problems contribute to the perception of cancer as one of the most feared global health challenges for diverse ethnic/racial communities (e.g., see Rayne, Schnippel, & Firnhaber et al., 2017; Vrinten, McGregor, & Heinrich et al., 2017). Fear of cancer is routinely displayed during clinical encounters and in family conversations outside the clinic (e.g., see Beach, Easter, & Good, et al., 2005; Beach, 2009; Beach & Dozier, 2015).

Adding to these challenges is a documented reticence to talk openly and frequently about health concerns occasioned by cancer. Black men are hesitant to disclose fears arising from prostate cancer (Jones, Taylor, Bourguignon et al., 2008); Black women surviving breast or cervical cancer (Ashing-Giwa, Kagawa-Singer, Padilla et al., 2004) often attempt to maintain the image of being a “strong Black woman” (Im, 2008, p. 39). While these findings may well characterize Black Americans, they are applicable to other patients and families facing cancer challenges. The quality and frequency of family and social support from friends and church members are crucial for treatment adherence, recovery, and overall quality of life (Hamilton, Moore, Powe et al., 2010). Supportive communication and collaborative team efforts are essential for managing cancer fears, reducing stigma, and providing hopeful and healing outcomes.

One prominent resource for affecting behavioral change involves translational family storytelling, the use of stories told within families as a framework for designing health communication interventions (Flood-Grady & Koenig Kellas, 2018). Because WCC is constructed exclusively from actual utterances and interactions of a real family telling their own stories, the theatrical performance is best described as nested translational family storytelling. Verbatim family storytelling is nested within a theatrical production, one form of translational family storytelling. Hearing how other patients and family members navigate their cancer journeys can facilitate discussions about shared illness and caregiving experiences, creating the potential for effective interventions that improve human health and well being (Koenig Kellas, 2018; Wethington, Herman, & Pillemer, 2012). The present study addresses intriguing theoretical and practical issues associated with translational family storytelling. Specifically, how does family storytelling in a White family resonate with unique aspects of the Black American experience? Findings of this study provide heuristics for designing and implementing communication health messages that improve how cancer is discussed and managed.

Entertainment Education, WCC, and Authenticity

This study employed a novel approach to Entertainment Education (EE) by utilizing naturally occurring family phone conversations as an authentic communication resource. Authenticity is defined as the degree to which a theatrical performance is based on actual utterances of real people in real time (not words and interactions created by the playwright). In the theatrical performance of When Cancer Calls... (WCC), a character (the Professor, whose own mother in real life died from cancer) explains to the audience that the entire performance is based on verbatim statements made by members of a real family over the phone while negotiating the family’s cancer journey.

EE is defined as the placement of health messages within entertaining media content to influence awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and/or behaviors of audiences (Singhal & Rogers, 1999). Prior EE scholarship suggests health communicators should segment health messages by matching messengers with ethnically, racially and culturally homogenous populations (e.g., Slater, 1996; Singhal & Rogers, 1999; Keuter & McClure, 2004; Hornik & Ramirez, 2006). The concept of homophily suggests that cultural similarities foster connections. Mediated messages are most efficacious when tailored to these differences (e.g., see McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001).

Critical for effective EE messages is perceived authenticity — the truth of the story told as seen through the eyes of an audience, based on the story’s coherency and fidelity (Dozier, Beach, & Gutzmer et al., 2017). People use storytelling for evaluating, updating, animating, dramatizing, and commiserating about health issues and everyday life experiences (Fisher, 1987; Goodwin, 1990; Mandelbaum, 2013). Research indicates that audience members evaluate stories based on perceived coherency (i.e., internal logic) and fidelity (i.e. authenticity); audiences rely on their own history and cultural backgrounds to discern if the story “is ‘fake’…rings ‘true’…sounds ‘right’” (Edgar & Volkman, 2012, pp. 289, 589). These assessments are essential when determining if and how audiences accept, ignore, or reject various stories. The higher the coherency and fidelity of the story, the more likely people will identify with, be transported into, and essentially experience parasocial interactions with productions involving actors displaying shared human dramas.

The present study challenges historical EE assumptions of homophily by assessing the impacts of authentic family conversations about cancer over the telephone. One way of addressing translational storytelling is WCC. This is a professional theatrical production generated from naturally occurring conversations of a single family throughout a 13-month cancer journey. Phone calls (61) were recorded by one family member, subsequently transcribed, and analyzed to discover how family members talk through cancer on the telephone (Beach, 2009). These calls are remarkable for three primary reasons. First, the conversations between family members represent the first recorded natural history of a family talking about and through cancer from diagnosis through death of a loved one (wife/ mother/sister). Second, all dialogue in WCC is drawn verbatim from actual phone conversations as family members navigated their way through a longitudinal cancer journey. Edited from seven hours into an 80-minute performance, WCC provides audiences with unique opportunities to hear, discuss, reflect on, and possibly alter behaviors for managing cancer challenges. Third, as discussed below and of particular relevance for health communication research, are curious and unexpected findings from the pilot study (Beach, Buller, & Dozier et al., 2014): Persons of Color (POC) were significantly more likely to assess WCC interactions as authentic and influential, and to highly recommend WCC to others (Dozier, Beach, & Gutzmer et al., 2017), even though White actors in the theatrical production portrayed the White family that originally recorded and later donated the audio recordings for research and education.

Arguably, all audiences are likely to evaluate EE more favorably when it is perceived and experienced as authentic storytelling. As an intervention, WCC is a theatrical reenactment of oral communication, enacted as authentic translational storytelling, involving a cancer patient and extended family. Thus, the potential exists for strong resonance among diverse audience members and, in particular, unique aspects that may favorably dispose Blacks to oral storytelling within an extended family. Before discussing prior research and current findings about audience members’ responses to viewing WCC, we provide an overview of the historical importance of oral history to Black American experiences and cultural legacy.

Oral History and Black Experiences

Given that Black Americans are more likely to die from cancer and face challenges with health care systems, it is important to understand if and why messages about cancer resonate with Black audience members. Consider, for example, how the Black American cultural legacies include coping with a wide array of degradations. During the 400-year period of European slave trade, about 40 to 100 million Africans were transported into slavery in the Americas (Rodney, 1974). The maafa (Kiswahili for great disaster and tragedy) brutalized Africans immigrants and their descendants in every aspect of their lives (Mitchell, 2008). Under slavery, Blacks were not allowed to form families in the same ways that most White families were formed. Slaves could not enter into legal Christian marriage; slaves were categorized as property rather than as autonomous beings with legal rights (Cott, 2002). Slave owners disrupted families by separating them through sales, replacing family structures and relationships with identities based on being someone’s property, or discouraging slaves from running away through physical violence and by forcing them into arranged marriages not of their own choosing. These adverse conditions “not only inhibited family formation but made stable, secure family life difficult if not impossible” (Williams, 2016, para. 2; see also, Gutman, 1977).

In addition to extreme life-threatening physical conditions, slaves also contended with living in constant duress from shareholders’ attempts to suppress literacy and constrain customs reflecting racial and ethnic heritage. Under these challenges, Blacks relied heavily on oral performances as coping strategies for managing the tragedies and oppression of American slavery. One primary consequence is the possibility that, over time, Black Americans came to more fully appreciate the importance and resilience of family, amidst devastating struggles (such as slavery or cancer), as threats that families cannot fully control.

The Adaptive Black Family

When Black families cope with cancer, Van Campen and Marshall (2010) listed five key strengths: “strong kinship bond, work orientation, culture of achievement, religious views, and ability to change family roles” (p. 4). These adaptive strategies are consequences of historical mistreatment. Faced with obstacles, Black families became more resilient and even proactive (Staples, 1976). As Jones (1982, p. 237) observed, “under slavery, blacks’ attempts to maintain the integrity of family life amounted to a political act of protest” (Jones, 1982, p. 237). Moreover, evidence shows that slaves may have enacted family traditions from their homeland to maintain familial ties. The West African family, regarded as a clan, seems to be the model for extended kinship structures in contemporary Black American communities (Gutman, 1977). Understood as both a social and political movement, some Black American families became more solidified under oppression. Family members become more capable, from ancestral narratives and first-hand experience, of possessing what may well be a greater capacity for empathy and even compassion for other families (regardless of race and ethnicity) facing difficult circumstances that are not easy to control.

The Power of Oral Storytelling

While the importance of oral storytelling among Black Americans is best understood in the historical context of slavery, it is important to recognize that slave owners have been documented as terrified of slaves who could read and write (Mitchell, 2008). Slave owners lived in fear of rebellion. Indeed, Aptheker (1963) estimated that over 250 slave revolts occurred prior to emancipation. Slave owners understood that literate slaves would have greater resources to organize resistance and rebel. Thus, throughout the antebellum South, laws were passed that prohibited the education of slaves to read and write. Mitchell (2008) noted that slaves caught trying to learn to read and write were severely punished, including “loss of privileges, confinement, whippings, and beatings to mutilation and death” (p. 88). In this context, oral storytelling was not only a tool of survival; it was subversive of a corrupt and dehumanizing social order.

The rich oral traditions of their African roots and subsequent experiences with enslavement and segregation in America have been preserved through a complex web of poems, myths, folktales, songs, chants, narratives, and storytelling activities (e.g., see Angelou, 1969; Abrahams, 1985; Goss & Barnes, 1989; Gates & Tater, 2017). Scholars of Black American culture have documented vernacular details of language, tone, and prosody through which speech communities and dialect were achieved (Abrahams, 2005). Vernacular storytelling performances animate past circumstances, situating here-and-now experiences as perpetual displays of recurring problems and promises of everyday living. Through stories, family and community members portray deeply troubling and at times jocular, even playful characterizations of characters, relationships, situations, and hardships. For families and their social networks, spontaneous storytelling activities are critical yet ordinary resources for claiming and retaining memberships in diverse speech communities.

Pilot Study Findings

The pilot study (Phase I of the research project) used a prototype of WCC as a treatment, included small samples in San Diego and Denver, and provided evidence that translational storytelling resonates with audiences (Dozier, Beach, & Gutzmer et al., 2017). Results of the main study (Phase II of the research project), replicating pilot study findings on storytelling, are reported here. After viewing WCC in the pilot study, large majorities agreed that the theatrical performance held their interest from beginning to end, provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer, was appropriate for “people like me,” would recommend it to others, “influence people like me,” and that it was uplifting and inspiring (see Table 1). A detailed description of the WCC intervention is provided in the Methods section. On a theoretical level, the researchers posited that audience members were transported into a shared human drama faced by all families undergoing cancer, regardless of race or ethnicity.

Table 1.

Evaluations of WCC From Pilot Study and Current Study

| Pilot Study (Phase I) | % Neutral & Unfavorable | % Favorable |

|---|---|---|

| RQ1: Authentic portrayal | 10% | 90% |

| RQ2: Appropriate for people like me | 10% | 90% |

| RQ3: Influence people like me | 14% | 86% |

| RQ4: Held my interest | 10% | 90% |

| RQ5: Uplifting and inspiring | 27% | 74% |

| RQ6: Recommend to others | 11% | 89% |

| N=186 | ||

| Main Study (Phase II) | % Neutral & Unfavorable | % Favorable |

| RQ1: Authentic portrayal | 5% | 95% |

| RQ2: Appropriate for people like me | 20% | 80% |

| RQ3: Influence people like me | 14% | 86% |

| RQ4: Held my interest | 23% | 77% |

| RQ5: Uplifting and inspiring | 37% | 63% |

| RQ6: Recommend to others | 20% | 80% |

| N=483 | ||

As noted previously, a long history of EE theory suggests that actors communicating messages should be ethnically and culturally homogenous with targeted audiences to be efficacious (Singhal & Rogers, 1999, 2002). When making sense of these findings, however, the researchers realized that they had relied too heavily on prior theorizing and empirical studies in EE research. Based on concepts of homophily and market segmentation, we expected that individuals from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Blacks, Hispanics, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders) would not identify as strongly with a White family’s cancer experiences as other White people might. This expectation was not confirmed; the pilot study indicated the opposite to be the case (Dozier et al., 2017). Findings indicated that White audience members were significantly less favorable in their overall evaluation of WCC than POC (including Black Americans). POC were significantly more likely to evaluate WCC interactions as authentic and influential and to highly recommend WCC to others.

Importantly, pilot study findings demonstrated what researchers have described as ‘non-homophily effects’ (Alstatt, Madnick, & Valu, 2014): Regardless of race or ethnicity, audience members were transported into a shared human drama faced by all persons undergoing cancer. After the pilot study performances, 90% of all audience members in San Diego and Denver agreed that WCC provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer. For all measures, POC in the audiences rated WCC more favorably than did White audience members. This was an unexpected finding that seemed inconsistent with principles of homophily and audience segmentation. This motivated the research team to retest the pilot study findings on a larger, more representative national sample in the main study. Further, as noted elsewhere (Dozier et al., 2017), the pilot study sample size was too small to tease out differences among different POC subpopulations. The current study (see Methods section) involved data collection from a sample with greater representation of POC. The same six evaluation measures of WCC were used in pilot and main studies. This larger sample permitted separate analysis of differences between how the baseline data provided by White audience members compared with Latino/Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and Black Americans.

A unique aspect of WCC is its authenticity. Dozier et al. (2017) emphasized that authenticity helps audience members suspend disbelief and transport themselves into the unfolding drama. Because cancer has touched the families of the vast majority of audience members (see Findings section), the storytelling of characters in WCC causes some audience members to recall similar storytelling in their own families. Thus, WCC may resonate with audience members, leading them to agree that WCC is appropriate and influential for “people like me.” Although the cancer patient in WCC dies in the end, the family supports each other on the journey. Thus, WCC can be perceived as uplifting and inspiring because the extended family is uplifting and inspiring. In turn, this arguably influences audiences to recommend WCC to others.

Research Questions

Six evaluation statements embedded in RQ2-RQ7 are based on theory and prior research. (RQ1 is the mean of the items in RQ2-RQ7.) Although RQ1 provides the most robust test of relationships using an index with strong face validity and demonstrated reliability, testing of the individual items provides a more detailed, textured, and revealing appreciation of how audiences responded to each evaluation statement. The six items are face-valid measures of audience reactions to WCC. Authenticity is an important objective attribute of WCC. The measure of perceived authenticity (RQ2) was considered an important theoretical attribute of WCC. The other measures (see Table 3 for exact wording of these items) are self-explanatory measures of audience reactions and impact of WCC.

Table 3.

Opinion Statements Assessing Audience Reactions to WCC

| Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1: Overall evaluation using Entertainment-Education Evaluation Index (EEEI) | 1.93 | 2.17 | 1.39 |

| RQ2: I felt that the performance provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer. | 2.84 | 3.00 | 1.30 |

| RQ3: The performance was appropriate for people like me. | 2.10 | 2.00 | 1.78 |

| RQ4: The performance would likely influence people like me. | 1.90 | 2.00 | 1.80 |

| RQ5: The performance held my interest from beginning to end. | 1.72 | 2.00 | 1.92 |

| RQ6: I felt that the performance was uplifting and inspiring. | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.90 |

| RQ7: I would recommend this performance others. | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.85 |

-

RQ1:

Overall, how do participants who are White, Black, and other POC evaluate WCC?

-

RQ2:

How do participants who are White, Black, and other POC perceive the authenticity of WCC?

-

RQ3:

How do participants who are White, Black, and other POC perceive the appropriateness of WCC “for people like me?”

-

RQ4:

How do participants who are White, Black, and other POC evaluate the degree of influence of WCC?

-

RQ5:

How do participants who are White, Black, and other POC evaluate their levels of interest in WCC?

-

RQ6:

How do participants who are White, Black, and other POC evaluate WCC as uplifting and inspiring?

-

RQ7:

How do participants who are White, Black, and other POC intend to recommend WCC to others?

Methods

The pilot study was Phase I of an NCI-funded research project. For the main study (Phase II) reported here, a quasi-experimental design was implemented in four cities: San Diego, CA; Salt Lake City, UT; Lincoln, NE.; and Boston, MA. The overall goal of the main study was to test the impact of WCC (pretest/posttest change scores) when compared to a placebo. Major findings of the main study are reported elsewhere (Beach et al., 2016). The present study examines a subset of a large sample of the main study data. Responses to the six items were collected after audience exposure to WCC. The present analysis does not include audience reactions to the placebo treatment. Following exposure to WCC, participants were asked to participate in a post-exposure discussion of their reactions to WCC.

In each city, audience members were recruited to attend one of two video presentations. All participants were 18 years old or older, required to read and speak English, paid a $50 incentive to participate, and provided informed consent. Institutional review boards (IRBs) at all participating institutions approved the study and consent procedures.

The research team formed partnerships with a hospital, two universities, and a comprehensive cancer center to assist in recruiting. Participants were recruited through newspaper and online advertisements, outreach to community organizations, and cancer centers in each community. Researchers initially sought a target sample size of 1,200, with approximately 300 participants recruited for each site. The goal was to obtain statistical power of .80. Final recruitment resulted in a total of 1,006 participants (84% of target) who completed onsite pretest-posttest measures.

The Treatment

Of the 1,006 participants in the study, 483 (48%) were exposed to WCC. As noted, the treatment video is unique because the dialogue in the 80-minute theatrical production was extracted verbatim from 61 recorded telephone conversations comprising over 7 hours of interactions over a 13-month period. The theatrical production was performed before a live audience in San Diego; a video recording of the production was produced and used for treatments in each city. To underscore authenticity, actors read directly from the script to emphasize that all storytelling was verbatim. In those conversations, a real family navigated its cancer journey from initial diagnosis to the death of a family member. The family in WCC is White. To preserve authenticity, professional actors portraying family members were also White.

The 80-minute production embodies the “interactive process of sharing stories with others using an oral medium” (Banks-Wallace, 2002, p. 411). Consistent with translational storytelling, a wide array of conversational topics “affect and reflect psychosocial, physical, and relational health” (Koenig Kellas, 2018, p. 63). Throughout WCC, significant and endearing stories about topics such as good and bad cancer news, family dogs, cars, food, and considerably more were interwoven with how the family coped with its cancer journey. Storytelling involved the nuclear family (mother, father, and son) as well as the son’s grandmother, his ex-wife, and his current girlfriend. These features of WCC were not embedded as intentional experimental treatments. Rather, these features emerged organically from the corpus of more than seven hours of recorded and transcribed telephone conversations.

Instrumentation and Measurement

To answer the research questions above, researchers used a 9-point Likert-type scale to measure levels of agreement with six evaluative statements about WCC. The scale ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (9). For reporting purposes, the 9-point Likert-type scales were modified using a constant (−5.0), such that “neutral-unsure” equals zero. Favorable ratings range from 1 to 4 (strongly agree). Unfavorable ratings range from −1 to −4 (strongly disagree).

The Entertainment-Education Evaluation Index (EEEI) was created during the pilot phase of this project (see Research Questions section for a rationale for the item set.) Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used on the pilot data. Initial factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 were extracted using the principal components methods. A single factor emerged, accounting for 63% of the explained variance in the set. Cronbach’s alpha for the pilot data was .88. Using the main study data, the item set was subjected to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good fit of the six items on a single factor (χ2 (9, N=483)=37.30, p<.05; RMSEA=.081; CFI=.980). The EEEI is the mean of the six evaluation items; Cronbach’s alpha for the EEEI in the main study is .88. The EEEI was used to answer RQ1. The remaining tests (RQ2-RQ7) analyze single items from the EEEI.

Table 2 provides a breakdown of the valid sample by self-reported racial/ethnic identification. Note that each racial/ethnic measure was non-exclusive and binary. Participants were encouraged to “please check all that apply” to a standardized list of ethnic and racial categories. Thus, the total number in all groups exceeds the overall sample size (N=483). The total percent exceeds 100%, since participants could self-identify with multiple racial/ethnic groups. For statistical analysis, a White participant was operationally defined as any participant who responded affirmatively to the binary indicator “White/Anglo.” A Black participant was operationally defined as any participant who responded affirmatively to the binary indicator “African American.” If a Black participant indicated additional ethnic or racial identification, the participant remained classified as “African American.” Other Persons of Color were operationally defined as any participant that did not indicate that he or she was “White/Anglo” or “African American.” These participants included participants who self-identified as “Hispanic or Latino,” “Asian,” “Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander,” and/or “Native American/Alaskan Native.” These binary categories were listed on the questionnaire. Participants also were permitted to self-identify through an open-ended “Other (please describe)” variable. Researchers assigned participants who self-identified as Middle Eastern (n=12) to an additional binary variable.

Table 2.

Distribution of Self-Reported Racial/Ethnic Identification

| Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| White (baseline participants; same as WCC family and cast) | 355 | 64% |

| Persons of Color (different from WCC family and cast) | ||

| Asian American | 65 | 13% |

| Hispanic/Latino American | 66 | 11% |

| Black | 26 | 5% |

| Pacific Islander | 14 | 2% |

| Native American | 10 | 2% |

| Middle Eastern | 12 | 2% |

NOTE: Percentages based on sample size of 483. Total number and percent in this table is greater than 100% because respondents could identify with multiple racial/ethnic groups.

Of the 483 participants exposed to the WCC treatment, 69% were women and 31% were men. Average age was 31.9. Of those, 196 were exposed to the WCC treatment in San Diego, 123 in Boston, 103 in Salt Lake City, and 61 in Lincoln. Regarding cancer status, 6% self-identified as current cancer patients, 10% identified as cancer survivors, 34% were members of families where someone was currently undergoing treatment for cancer, and 29% were members of families where someone was a cancer survivor. Fully 59% had lost a family member to cancer. The total percentage exceeds 100% because the variables were binary; a participant might have multiple levels of cancer status with different family members (e.g., grandfather died from cancer and mother is a cancer survivor).

Data Analysis

White participants provided baseline data for evaluating WCC. Based on the concept of homophily, one would expect White participants to respond most favorably to WCC because all characters in the theatrical production are White. Thus, statistical differences were tested between baseline (White) participants and 1) African American participants and 2) all participants indicating that they were POC but not Black.

Results

As in the pilot study, participants gave WCC very positive evaluations. As shown in Table 1, participant evaluations ranged from 63% favorable for rating WCC uplifting and inspiring to 95% agreement that WCC provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer. The use of storytelling based on verbatim conversations among family members resonated with the vast majority of participants. Table 3 provides further description of participant responses. Mean and median scores are provided for the overall evaluation of WCC (RQ1) and for each of the six individual measures (RQ2-RQ7). Means range from a low of 1.02 for RQ6 (WCC was uplifting and inspiring) to a high of 2.84 for RQ2 (authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer).

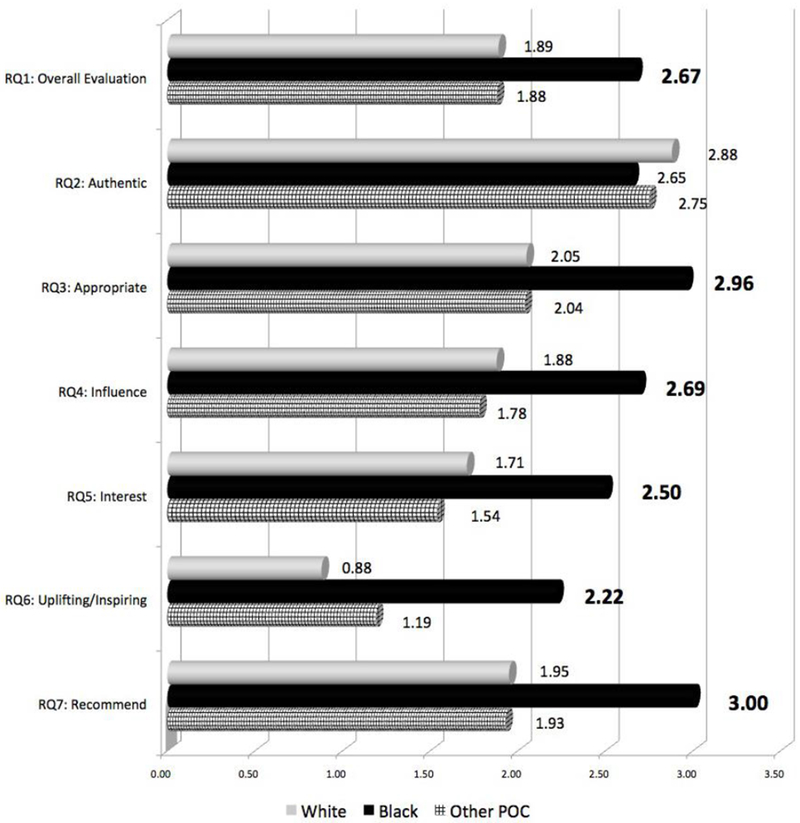

Figure 1 graphically displays average scores for White, Black, and POC (not Black) participants for the overall evaluation of WCC (RQ1). The six individual assessments (RQ2-RQ7) are also shown. As displayed in bold, Black participants gave much higher overall evaluations (RQ1) of WCC than did White participants and POC who were not Black. The same pattern was sustained for RQ3-RQ7. Black participants were more likely to agree that WCC was appropriate and influential for “people like me.” Black participants more strongly agreed that WCC held their interest from beginning to end and that WCC was uplifting and inspiring. They were more likely to recommend WCC to others. When comparing other POC who are not Black to White baseline participants, their evaluations of WCC differed little. The only measure where White, Black, and other POC did not differ was with regard to the authenticity of WCC. As noted above, however, the vast majority (95%) of all participants agreed that WCC provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer.

Figure 1.

Mean scores for EEEI and six individual evaluations of WCC from White, Black, and other POC (not Black) participants.

Figure 1 suggests that Back participants evaluated WCC significantly more favorably than White (baseline) participants. Table 4 displays a test of differences between Black participants and White participants. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant differences in means and to generate measures of effect size (η2).

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance of Overall Evaluation and Six Individual Evaluations of WCC by White (Baseline) and Black Participants

| White | Black | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | d.f. | F | p | η 2 | |

| RQ1: Entertainment-Education Evaluation Index (overall evaluation) | 1.89 | 1.32 | 2.67 | 1.60 | 1, 372 | 7.61 | <.01 | .020 |

| RQ2: I felt that the performance provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer. | 2.88 | 1.21 | 2.65 | 1.70 | 1, 376 | 0.79 | .38 | .002 |

| RQ3: The performance was appropriate for people like me. | 2.05 | 1.74 | 2.96 | 1.51 | 1, 375 | 6.50 | .01 | .017 |

| RQ4: The performance would likely influence people like me. | 1.88 | 1.70 | 2.69 | 2.07 | 1, 374 | 5.37 | .02 | .014 |

| RQ5: The performance held my interest from beginning to end. | 1.71 | 1.92 | 2.50 | 1.73 | 1, 376 | 4.15 | .04 | .011 |

| RQ6: I felt that the performance was uplifting and inspiring. | 0.88 | 1.85 | 2.22 | 2.16 | 1, 375 | 11.86 | <.01 | .031 |

| RQ7: I would recommend this performance others. | 1.95 | 1.81 | 3.00 | 1.70 | 1, 376 | 8.19 | <.01 | .021 |

As shown in Table 4, Black participants gave WCC a significantly higher overall rating (RQ1) than did White participants. Black participants reported more favorable evaluations for RQ3-RQ7. Effect sizes (η 2) ranged from a low of .011 (WCC held my interest from beginning to end) to a high of .031 (WCC was uplifting and inspiring). The only test that was not statistically significant was the statement that WCC provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer.

As shown in Figure 1, POC who are not Black differed little from White baseline participants in how they evaluated WCC. Table 5 displays a test of differences in means for RQ1-RQ7. Differences between White and POC participants were not statistically significant for any of the seven tests.

Table 5.

Analysis of Variance of Overall Evaluation and Six Individual Evaluations of WCC by White (Baseline) and POC (Not Black)

| White | POC (Not Black) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | d.f. | F | p | η 2 | |

| RQ1: Entertainment-Education Evaluation Index (overall evaluation) | 1.89 | 1.32 | 1.88 | 1.53 | 1, 451 | 0.01 | .93 | .000 |

| RQ2: I felt that the performance provided an authentic portrayal of how families deal with cancer. | 2.88 | 1.21 | 2.75 | 1.47 | 1, 455 | 0.79 | .38 | .002 |

| RQ3: The performance was appropriate for people like me. | 2.05 | 1.74 | 2.046 | 1.951 | 1, 454 | <.01 | .95 | .000 |

| RQ4: The performance would likely influence people like me. | 1.88 | 1.70 | 1.78 | 2.01 | 1, 453 | 0.24 | .63 | .001 |

| RQ5: The performance held my interest from beginning to end. | 1.71 | 1.92 | 1.54 | 1.93 | 1, 455 | 0.61 | .43 | .001 |

| RQ6: I felt that the performance was uplifting and inspiring. | 0.88 | 1.85 | 1.19 | 1.89 | 1, 454 | 2.14 | .14 | .005 |

| RQ7: I would recommend this performance others. | 1.95 | 1.81 | 1.93 | 1.970 | 1, 454 | 0.01 | .91 | .000 |

A number of control variables might influence differences in how Black and White participants evaluated WCC. Because none of the research questions addressed the impact of these control variables, this analysis was conducted as post hoc analysis. Control variables included age, gender, and cancer status of the participant. Cancer status was measured through five non-exclusive binary variables: 1) current cancer patient, 2) cancer survivor, 3) family or friend of cancer patient, 4) family or friend of cancer survivor, and 5) lost family or friend to cancer. Using the overall evaluation of WCC as the dependent variable (EEEI scores), the control variables of age, cancer status as a current patient, and cancer status as having a family member or friend with cancer were significantly related to EEEI. However, none of these covariates was significantly related to whether the participant self-identified as Black or White.

To rule out these control variables as rival explanations for the relationships reported above, ANOVA with multiple classification analysis (MCA) was used to test the relationship between overall evaluation of the WCC (EEEI scores) and self-identification of participants as either Black or White, while controlling for age, gender, and the five measures of cancer status. Adjusted means are the means for each group, after controlling for control variables (covariates). The adjusted mean for Black participants was 2.52 (unadjusted mean=2.67); the adjusted mean for White participants was 1.90 (unadjusted mean=1.89). After controlling for all seven covariates, the difference between Black and White participants is statistically significant, F(1, 365)=4.87, p=.03, η2 =.020. After controlling for the seven covariates, Black participants reported significantly more favorable overall evaluations of WCC, when compared to White participants.

Notably, Black audience members did not respond with any sense of bias or prejudice against Whites. Just the opposite seems to be the case. Although Blacks have been reported to keep things hidden within the family system (Williams, 2016), the WCC intervention provided opportunities to open up discussions with audience members following exposure to WCC. In moderated post-exposure discussions, which were part of this study, many audience members across various ethnic and racial groups described WCC as cathartic. WCC provided them with a sense of relief, knowing that others have experienced similar kinds of troubles and remedies. Moreover, exposure to WCC was depicted as a powerful triggering device for generating meaningful discussions about how laypersons, families, and medical professionals experience cancer and rely on alternative techniques for navigating their way through cancer journeys.

Discussion

The authenticity of WCC resonated across participants, regardless of racial or ethnic identity. The consensus on authenticity was so universal, no significant differences were found across racial/ethnic groups. Participants varied little in their assessment of WCC’s authenticity. Regarding all other assessments of WCC, including the overall Entertainment-Education Evaluation Index, Black participants reported more favorable evaluations than did White participants and POC who were not Black. POC who were not Black differed little from White participants in their evaluations. This confirms the argument that there is something unique about the Black American experience that makes them more responsive to oral family storytelling – even if the storytellers are all White. These results disconfirm the proposition, based on homophily, that audiences respond more favorably to health communication messages delivered by messengers who share racial and ethnic characteristics with the audience.

Black Americans in the audience were significantly more likely to agree that the cancer journey of a real White family was appropriate for “people like me” and would influence “people like me.” Compared to Whites and other POC, Black Americans found WCC significantly more uplifting and inspiring, agreed significantly more strongly that it held their interest from beginning to end, and were significantly more emphatic that they would recommend WCC to others.

To understand why Black Americans responded so favorably to WCC, one must consider how oral storytelling was accomplished in the theatrical production. Black American audience members strongly resonated with authentic (i.e., naturally occurring) stories, co-authored by members of an extended family, as they rely on verbatim transcriptions of ordinary conversations to reveal how a family navigated a cancer journey over time. Communication tools for surviving slavery, and coping with racism in contemporary society, function as residual cultural strengths helpful for framing and interpreting our findings. Stories about coping with difficult cancer challenges, as well as hopes for a brighter future, are embedded throughout these telephone conversations and thus prominent performance resources. These interactions involve a father, a mother, their son, the son’s grandmother, his ex-wife, and his current girlfriend across diverse topics (e.g., news updates, commiseration about uncertainty, future plans, and expectations). WCC translates and makes available these interactions for others whose lives have somehow been impacted by cancer. Performed oral storytelling thus can enhance authentic identification as human beings sharing similar cancer journeys fraught with uncertainties, fears, and hopes. Findings from this study reveal that authentic family storytelling minimizes ethnic and racial differences between the White family in WCC and Black Americans who attended and responded to this everyday language performance.

Oral Family Storytelling and the Unique Black American Experience

As explicated in the literature review, oral family storytelling plays an important role in all aspects of survival of Black Americans in a hostile environment. The unique history of Black Americans provides unique opportunities for efficacious health communication interventions. Authentic oral storytelling about family health issues offers a powerful and empirically supported approach to health communication interventions and campaigns designed specifically to assist Black Americans with managing communication, illness, and disease. Just as oral storytelling has been a tool of survival and resistance for Black Americans who have suffered inhumane treatment beyond their control, translational family storytelling emphasizing oral communication provides a powerful triggering mechanism for Black audiences who listen, reflect on, and generate further stories about past and current health circumstances. After viewings, moderated discussion groups may help Black audience members volunteer and participate in family conversations about cancer impacts. Various social media (e.g., blogs) could also be utilized to foster contacts with other families who have seen and experienced WCC performances and post-discussions.

One dangerous misinterpretation of our research is that it’s appropriate to under-represent Blacks and other POC in health communication campaigns/programs and in popular media. Under-representation of all POC is an ongoing problem in popular media and advertising (Boulton, 2016). As Weick (1979) suggested, the principle of requisite variety states that diversity inside an organization (e.g., a health communication campaign) must be as diverse as the external environment (e.g., potential breast cancer patients). Thus, under certain specified conditions, ethnic and racial homophily between communicator and audience may not matter. However, as Valente (2002) noted, formative evaluation (e.g., focus groups, participant observation, message testing) with target populations such as Blacks and other POC is critical to developing efficacious strategies for health communication campaigns. We argue that, when Blacks and other POC are targets of health communication programs, all POC affected must be encouraged to participate in the actual planning, implementation, and evaluation of those campaigns. It is not sufficient, for example, to inviting POC to participate in focus groups for the sole purpose of fine-tuning messages.

Future Research

Using the present findings as a foundation, continued inductive and qualitative research will allow future researchers to develop more anchored concepts and empirical generalizations within ordinary and daily conversational interactions. These empirical generalizations will, in turn, permit the explication of grounded theories that more fully explain and predict assessments of WCC by audiences from a wide range of backgrounds. In the end, we believe that family cancer journeys are only one critical area for investigation, especially since audience members (in moderated post-exposure discussions) repeatedly commented that WCC triggered thoughts and feelings across many types of illnesses and diseases (e.g., cardiovascular, diabetes, AIDS, dementia).

Because oral storytelling within extended families resonates with Black Americans, further questions can guide research and strategies for health communication program design and implementation. For example, for Black Americans is effective family communication and decision-making more critical for overall quality of living when compared to other ethnic and racial groups? Might Black families feel more responsible for the care of patients, and welfare of the family, due to their historical and cultural heritage? How do other healthcare factors influence how diverse families manage health challenges? For example, distrust of the medical community persists among some Blacks due to a shameful history of unethical medical treatment of Blacks. This mistreatment includes the Tuskegee Syphilis Studies and the cloning of Henrietta Lacks’ cells (e.g., see Washington, 2007; Skloot, 2011). In addition, research repeatedly reveals explicit and implicit bias against Blacks in diagnoses, treatment, patient-provider interactions, and access to medical care (Hall, Chapman, Lee et al., 2015; Lewis, Cogburn, & Williams, 2015).

It is quite possible that Black Americans have navigated their own hardships by extending kinship to others who are also facing fears, uncertainties, and hopes that they cannot fully control. When a family copes with cancer, the meaning of family may extend beyond cultural ancestry and genetic linkages to include all persons and families caught up in health dilemmas. In this important sense, family members can and do recognize that others undergo difficult circumstances. Windows of opportunity exist for responding with empathy, sympathy, support, compassion, love, and a host of other behaviors necessary for effective communication throughout sustained family cancer journeys.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations: 1) The evaluations of WCC were provided by participants immediately after viewing the theatrical production. Whether these evaluations of the theatrical production remain stable over time is unknown. Future research should examine evaluations of the theatrical production in a longitudinal design; 2) Self-identification of one’s race or ethnicity is a simple proxy measure of homophily. The concept of identity is complex for Black Americans (Jackson, 2002) and for all persons, regardless of color. As shown in Table 2, many participants (13%) identified with multiple racial and ethnic groups. Researchers should avoid oversimplification of identity, and assess how or if those with multiple identifications represent unique orientations to healthcare and communication. Note that we did not measure the complexities of perceived homophily. Rather, we triangulated homophily by treating White participants as providing baseline data (high homophily). Blacks and other POC were treated as possessing low homophily. Rather than conflating racial/ethnic similarity with homophily, future research should seek to examine identity and perceived homophily using more robust, multi-dimensional scales (Allen, 2007); 3) The subsample of Black Americans was small (n=26/5%). However, small sample size would mitigate against the strong statistical relationships we discovered between self-identified Black participants and favorable evaluations of WCC. A small sample favors the null hypothesis and Type 2 error. Nevertheless, a larger future sampling would permit more detailed analysis with regard to multi-racial and multi-ethnic identification.

Conclusion

This evaluation of WCC affirms how similar diverse people are. As shown in Table 1, the evaluations of WCC are positive for all audience members across all six measures. From these responses, we conclude that family phone conversations display supportive environments in the very midst of challenging health circumstances. Findings demonstrate that the customary “homophily effect” does not occur under all circumstances. Coming together to communicate about cancer as a family is treated as more similar and important than possible differences in racial/ethnic or cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and practices. Indeed, differences in race/ethnicity do not seem to constrain abilities for strongly identifying with the fundamental importance of family communication in times of trouble. Moderated audience discussions after exposure to WCC strongly confirm that audience members felt the performance was uplifting and hopeful, despite the mother/wife’s death. During the progression of cancer, the family in WCC relied on communication to come together and even grow. The power of family becomes evident when persons display ongoing love and support as emotional and relational difficulties inevitably arise and must somehow be managed.

The primal human social condition, especially but not exclusively when confronting illness and disease, may well be more similar than different. The basic fact that all humans travel through time and space together, relying on communication to navigate their way through unforeseen health circumstances, transcends many incompatible beliefs and lays important groundwork for realizing and accepting that humans are much more similar than different – especially when matters of communication and health are at stake. As Nouwen (2013, p.xxiv) so aptly states: “These obvious and beautiful differences among us seem small in the context of the unity that binds us all together. The unity of life among us is even deeper than the diversity between us.” Although ethnic and racial differences have been emphasized historically, this study serves as an important reminder that primal, universal similarities can and do exist whenever dilemmas of everyday living are experienced and understood as shared family dramas.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through Grant #’s 144235-01/02 (W. Beach, PI)

Contributor Information

Wayne A. Beach, Professor, School of Communication, Director, Center for Communication, Health, & the Public Good, SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Public Health, San Diego State University, Adjunct Professor, Department of Surgery, Member, Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego

David M. Dozier, School of Journalism & Media Studies, San Diego State University.

Brenda J. Allen, Department of Communication, Vice Chancellor for Diversity & Inclusion, University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical Campus.

Chelsea Chapman, UCSD School of Medicine, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, SDSU Graduate School of Public Health.

Kyle Gutzmer, UCSD School of Medicine, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, SDSU Graduate School of Public Health

References

- Abrahams RD (1985). African American folktales: Stories from black traditions in the new world. NY: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams RD (2005). Everyday life: A poetics of vernacular practices. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen BJ (2007). Theorizing communication and race. Communication Monographs, 74, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (2018). Cancer facts and figures for African Americans. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/cancer-facts-figures-for-african-americans.html. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- Angelou M (1969). I know why the caged bird sings. NY: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Aptheker H (1963). American Negro slave revolts. New York: International. [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, Tejero JS, Hsiao E, Chhabra R, & Tucker MB (2004). The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: A qualitative, multiethnic study. Psycho-oncology, 13, 709–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks-Wallance J (2002). Talk that talk: Storytelling and analysis rooted in African American oral tradition. Qualitative Health Research, 12(3), 410–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA (2009). A natural history of family cancer: Interactional resources for managing illness. New York: Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Easter DW, Good JS, & Pigeron E (2005). Disclosing and responding to cancer fears during oncology interviews. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 893–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Buller MK, Dozier DM, Buller DB, & Gutzmer K (2014). The Conversations About Cancer (CAC) Project: Assessing feasibility and audience impacts from viewing The Cancer Play. Health Communication, 29, 462–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, & Dozier DM (2015). Fears, uncertainties, and hopes: Patient-initiated actions and doctors’ responses during oncology interviews. Journal of Health Communication. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Dozier DM, Buller MK, Gutzmer K, Fluharty L, Myers VH, & Buller DB (2016). The Conversations about Cancer (CAC) Project -Phase II: National findings from watching When Cancer Calls… and implications for entertainment-education (E-E). Patient Education & Counseling, 99, 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton C 2016). Black identities inside advertising: Race inequality, code switching, and stereotype threat. Howard Journal of Communications, 27, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cott NF (2002). Public vows: A history of marriage and the nation. United States: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier D, Beach WA, Gutzmer G, & Yagade A (2017). The transformative power of authentic conversations about cancer. Health Communication, 32, 1350–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar T, & Volkman JE (2012). Using communication theory for health promotion: Practical guidance on message design and strategy. Health Promotion Practice, 13, 587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WR (1987). Human communication as narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value and action. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flood-Grady E, & Koenig Kellas J (2018). Sense-making, socialization, and stigma: Exploring narratives told in families about mental illness. Health Communication, DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1431016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates HL & Tatar M (Ed.) (2017). The annotated African American folktales. NY: Liveright Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin MH (1990). He said she said: Talk as social organization among Black children. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goss L & Barnes ME (1989). Talk that talk: An anthology of African American storytelling. NY: Simon & Schuester. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman HG (1977). The black family in slavery and freedom: 1750–1925. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Enge E, & Day SH, & Coyne-Beasley T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JB, Moore CE, Powe BD, Agarwal M & Martin P(2010). Perceptions of support among older African American cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37, 484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik RC, & Ramirez AS (2006). Racial/ethnic disparities and segmentation in communication campaigns. American Behavioral Scientist, 49, 868–884. [Google Scholar]

- Im E (2008). African-American cancer patients’ pain experience. Cancer Nursing, 31, 38–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J (1982). “My mother was much of a woman”: Black women, work, and the family under slavery. Feminist Studies, 8, 235–269. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Taylor AG, Bourguignon C, Steeves R, Fraser G, Lippert M, & Kilbridge KL (2008). Family interactions among African American prostate cancer survivors. Family & Community Health, 31, 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Kalles J (2018). Communicative narrative sense-making theory In Brathwaite DO, Suter EA, & Floyd K (Eds.). Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives, (2nd ed.) pp. 62–74. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, & McClure SM (2004). The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 439–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T, Cogburn CD, & Williams DR (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 407–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum J (2013). Storytelling in conversation In Sidnell J & Stivers T (Eds.). The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 492–508). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Simth-Lovin L, & Cook JM (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AB (2008). Self-emancipation and slavery: An examination of the African American’s quest for literacy and freedom. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 2(5), 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (2019). Cancer disparities. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/disparities Accessed March 25, 2019.

- Nouwen H (2013). Discernment. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rayne S, Schnippel K, Farnhaber C, Kruger D, Wright K, & Benn CA (2017). Fear of treatment surpasses demographics and socioeconomic factors in affecting patients with breast cancer in urban South Africa. Journal of Global Oncology, 3, 125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodney (1974). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A & Rogers E (1999). Entertainment-education: A communication strategy for social change. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, & Rogers EM (2002). A theoretical agenda of entertainment-education. Communication Theory, 12, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Skloot R (2011). The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Random House, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD (1996). Theory and method in health audience segmentation. Journal of Health Communication, 1, 267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples R (1976). Introduction to black sociology. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Valente T (2002). Evaluating health promotion programs. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Campen KS, & Marshall CA (2010). How families cope with cancer (Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth, and Families Research Link, Vol. 2, No. 4). Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona; https://mcclellandinstitute.arizona.edu/sites/mcclellandinstitute.arizona.edu/files/ [Google Scholar]

- Vrinten C, McGregor LM, Heinrich M, von Wagner C, Welles J, Wardles J, & Black GB (2017). What do people fear about cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis in the general population. Psychooncology, 26, 1070–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington HA (2006). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Weick K (1979). Cognitive processes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 1, 41–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, Herman H, & Pillemer K (2012). Introduction: Translational research in the social and behavioral sciences In Wethington E & Dunifon RE (Eds.), Research in the public good: Applying the methods of translational research to improve human health and well-being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Williams HA (2016, October 24). How slavery affected African American families. Retrieved from http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1609-1865/essays/aafamilies.htm on October 25, 2017.