Abstract

The immune system is quite remarkable having both the ability to tolerate innocuous and self-antigens while possessing a robust capacity to recognize and eradicate infectious pathogens and foreign entities. The genetics that encode this delicate balancing act include multiple genes and specialized cell types. Over the past several years, whole exome and whole genome sequencing has uncovered the genetics driving many human immune-mediated diseases including monogenic disorders and hematological malignancies. With the advent of genome editing technologies, the ability to correct genetic immune defects in autologous cells holds great promise for a number of conditions. Since assessment of novel therapeutic strategies have been difficult in mice, in recent years, immunodeficient mice capable of engrafting human cells and tissue have been developed and utilized for a variety of research applications. In this review, we discuss immune-humanized mice as a research tool to study human immunobiology and genetic immune disordered in vivo and the promise towards future applications.

Keywords: Immune, Humanized, Mouse, Monogenic, Immunotherapy

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Although genetic information between mice and humans is highly similar, comparisons described under the ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project identified many differences in gene regulation, particularly those associated with immune and metabolic processes in cells and tissues [1, 2]. For these reasons, it can be challenging to extrapolate data stemming from investigations into complex biological processes of the immune system using traditional inbred mice [3–6]. The introduction of human cells and tissues into specific strains of immunodeficient mice to generate mouse-human chimeras is one strategy that has enabled investigations pertaining to human biology within a tractable host without placing individuals at risk. This review focuses on the generation of human immune system (HIS)-mice (also referred to as humanized mice) as a tool for pre-clinical testing and investigations of immune disorders driven by genetic defects.

1.1. Immunodeficient mice and initial progress

In 1983, a spontaneous autosomal recessive mutation arose in a C.B-17 mouse strain at Fox Chase that was described as having a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) similar to what had been also observed in humans [7, 8], with the causal mutation in mice later identified in the gene encoding Protein Kinase, DNA-Activated, Catalytic Subunit (Prkdc) [9–13]. Being devoid of mature B and T cells, SCID mice are non-responsive towards B and T cell antigens and therefore their immune system does not reject xenogeneic cells or tissues [14–16]. Soon after, investigators began utilizing this strain to engraft human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) that enabled the study of antigen specific acquired immune response (donor primed) in Prkdcscid mice repopulated with human PBMCs [17, 18]. Subsequent uses of SCID mice included the transplantation of primary human tissues to study various pathologies affecting skin, vaginal, retinal, ovarian, renal, splenic, and intestinal tissues [19–26]. A significant advancement in translational biomedical research was the demonstration that SCID mice engrafted with autologous human fetal thymus and human liver tissue fragments underwent long-term hematopoiesis permitting human B and T cell development within a murine host [27, 28]. The fetal liver tissue provided the niche for hematopoietic stem cells and the thymic tissue provided the necessary structure to facilitate proper T cell education. Collectively, these seminal findings paved the way for the development of an in vivo platform to study human immunobiology.

1.2. Development and characterization of immunodeficient strains

Like the C.B-17 inbred strain, several other inbred strains have been widely utilized over the years. Backcrossing the Prkdcscid mutation onto various inbred strains revealed that non-obese diabetic (NOD).Prkdcscid mice support higher levels of human PBMC engraftment than any other strain tested [29]. This is largely due to NOD mice having impaired development and function of macrophages, natural killer (NK), NKT cells, and regulatory T cells (although not relevant for mice homozygous for Prkdcscid) [30–35]. Immune cell defects in the NOD strain have largely been mapped to two loci designated insulin-dependent diabetes susceptibility 3 (Idd3) and Idd5, which contain genes encoding interleukin-2 (Il2), Il21, and Ctla4 (as reviewed in [36]). In the early 2000s, another advancement in strain development occurred when targeted null mutations of the IL-2 receptor gamma chain (Il2rg) [37, 38] were combined with mice harboring Prkdcscid or null mutations in recombination activating genes (Rag1 or Rag2), which also results in lymphopenia. This addition further improved human immune cell engraftment and development in various strains including NOD.PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG), NOD.PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Sug (NOG), NOD.Rag1tm1MomIl2rgtm1Wjl (NRG), and BALB/c. Rag2tmFwa1Il2rgtm1Sug (BRG) [39–42]. Furthermore, the introduction of the Il2rg mutation improved human thymocyte development in the murine thymus of mice reconstituted with fetal or cord blood sourced CD34+ HSCs [43]. Surprisingly, NSG and NRG strains supported greater engraftment of human cells than that observed in BRG mice [44]. The difference observed in the efficacy of human cell engraftment was postulated to be due to a polymorphism in the signal regulatory protein alpha (Sirpa) locus of NOD mice that was similar to human SIRPA. SIRPα binds to CD47 and is expressed on most hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells and effective interaction between SIRPα and CD47 communicates a “do not eat me” signal to macrophages [45]. This role for SIRPA in permitting more robust human cell engraftment and development in NOD mice was confirmed using a NOD-Sirpa congenic and a human SIRPA transgenic BRG (BRGS) mouse strain [46–49]. Over the years, many immunodeficient murine strains have been developed that improve human immune cell engraftment and/or development to enable investigations of human immune cell function in vivo (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1:

Immunodeficient strains commonly used to generate immune humanized mice

| Common nomenclature | Strain background | Targeted/mutated murine loci | Human gene(s) present |

|---|---|---|---|

| NS | NOD | Prkdcscid | - |

| NSG | NOD | Prkdcscid, Il2rg | - |

| NSGAb°DR1 | NOD | Prkdcscid, Il2rg, H2-Ab1 | Tg(HLA-DRA*0101,HLA-DRB1*0101) |

| NSGMHCIIDQ8 | NOD | Prkdcscid, Il2rg, H2dlAb1-Ea | Tg(HLA-DQA1,HLA-DQB1) |

| NSG-SGM3 | NOD | Prkdcscid, Il2rg | Tg(KITLG, GM-CSF, IL3) |

| NOG | NOD | Prkdcscid, Il2rg* (truncation) | - |

| NRG | NOD | Rag1, Il2rg | - |

| BRG | BALB/c | Rag2, Il2rg | - |

| BRGS | BALB/c | Rag2, Il2rg, congenic(NOD.Sirpa) | - |

| MITRG | BALB/c | Rag2, Il2rg | CSF1, CSF2, IL3, TPO |

| MISTRG | BALB/c | Rag2, Il2rg | CSF1, CSF2, IL3, TPO Tg(SIRPA) |

2. Genetics driving immune dysregulation

2.1. Monogenic disorders of the immune system

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have linked specific genetic polymorphisms to a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases. Although GWAS implicates genes involved in disease susceptibility, most immune disorders and diseases are not monogenic. The penetrance of inheritable autosomal dominant/recessive and X-linked disorders define causal loci for a number of monogenic immune-mediated diseases. Diagnosis of monogenic immune-mediated diseases typically occurs following a suspected underlying immune deficiency leading to aberrant responses to pathogens presenting early in life. The World Health Organization currently estimates a global prevalence of monogenic disease at 1/100 births with novel causative variants for many inflammatory disorders still being defined. While immune monogenic diseases such as sickle cell anemia are more common, conditions such as hemophilia type A in males and severe combined immunodeficiency affect 1:5000 and 1:58,000 live births, respectively. Far more rare immunological diseases including immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, interleukin-10 receptor (IL10R) deficiency, chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), and others (Table 2) also present early in life. Collectively these conditions pose a significant increase in mortality rate and limited treatment options carry a high economic burden. In theory, most of these conditions are curable with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Nevertheless, identification of a suitable allogeneic donor or health status of the patient confound treatment options. Those patients who do receive allogeneic HSCT require systemic immunosuppression, which is not without additional risk.

Table 2:

Examples of monogenic disorders of the immune system

| Immune Monogenic Diseases | Genes | Manifestation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPEX, IPEX-like syndrome | FOXP3, CD25, CTLA4 | Enteropathy, dermatitis, endocrinopathy (T1DM, thyroiditis) | [50–54] |

| Infantile inflammatory bowel disease | IL10, IL10RA, IL10RB, TTC7,ADAM17, | Colonic inflammation | [55–58] |

| Omenn syndrome | RAG1, RAG2, JAK3, ADA, IL2RG | Erythoderma, desquamation, alopecia, chronic diarrhea, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | [59–62] |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | CYBA, CYBB, NCF1, NCF2, NCF4, CYBC1 | Infections, abnormal wound healing, granulomatous dermatitis, intestinal inflammation | [63–65] |

| Hyper IgE syndrome | STAT3 | Infections, dermatitis, elevated serum IgE | [66, 67] |

| Hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis | PRF1, STXBP2, STX11 | Febrile illness with multiple organ involvement | [68, 69] |

| Complement deficiency | C1QA, C1QB, C1QC,C4A, C4B, C2 | Infections with encapsulated bacteria, systemic lupus erythematosus like | [70, 71] |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | WAS | Thrombocytopenia, eczema, neutropenia | [72, 73] |

Since the presentation and genetic causes of monogenic diseases can be identified early in life, gene therapy or in situ gene correction with emerging technologies like clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) with its CRISPR-associated system 9 (Cas9) permit the use of autologous HSC that would eliminate long-term immune suppression, complications from graft vs. host disease, or reduce the graft rejection episodes. Both gene therapy and CRISPR-mediated gene editing is promising, but not without complications and controversy. Nevertheless, pre-clinical investigations using immune-humanized mice may mitigate risk in efforts employed to cure these patients.

2.2. Humanized mice to study monogenic immune disorders

The opportunity to study immune cells from patients with rare diseases in vivo without putting them at risk would be an ideal setting for characterization and pre-clinical therapeutic applications. Since many patients with these rare diseases are often diagnosed early in life, acquisition of patient samples for research purposes can be difficult. Furthermore, immune cell characterization is often restricted to peripheral blood which only provides a limited assessment into disease pathophysiology. For patients with IPEX, IL10R deficiency, or Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), allogeneic HSCT is curative. During anesthesia for central line placement, we obtained bone marrow CD34+ HSCs from a patient with IPEX syndrome prior to transplantation. The isolated IPEX CD34+ HSCs were injected into lightly irradiated 1-day old NSG or NSGAb°DR1 mice respectively. Interestingly, the NSGAb°DR1-IPEX mice had a high mortality rate, developed lung and liver inflammation, and generalized autoantibody production similar to what is observed in mice and humans with defective FOXP3 [74]. This phenotype was not observed in NSG-IPEX mice. Of note, the NSGAb°DR1-IPEX mice did not develop insulitis and had limited small bowel inflammation which is not consistent with classic IPEX syndrome and the reasons for this discrepancy remains unclear. Consistent with our findings, Keven Herold’s group blocked human Treg function in humanized mice using a monoclonal blocking antibody directed against CTLA-4 and documented hepatitis, autoantibody production, and a high mortality rate but did not report small bowel inflammation or insulitis [75].

In addition to assessing HSCs with mutations in FOXP3, our group also obtained bone-marrow derived CD34+ HSCs from a patient with an IL10RA loss-of-function mutation who presented with severe medical-refractory infantile-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). These cells were injected into a similar strain of NSG mice lacking murine MHCII and expressing HLA-DR1 as recently described [76]. Surprisingly, the immune reconstituted mice did not develop spontaneous intestinal inflammation as occurs in mice and humans with mutations in IL10 or IL10R genes [56]. Analysis of peripheral lymphoid cells showed an increase in the frequency of CD19+ B cells in the spleen and mesenteric lymph node over control (Fig. 1A). This observation is intriguing given that some patients with deleterious IL10R mutations develop B cell lymphoma suggesting a potential role for this pathway in regulating B cell development [77, 78]. Human immune cells recovered from these mice were non-responsive to exogenous IL-10 treatment (Fig. 1B, C), consistent with results obtained using primary PBMCs obtained from the patient. Interestingly, NSG mice harboring transgene encoding human KITLG, GM-CSF, and IL3 (NSG-SGM3) injected with IL-10R1-deficient PBMCs were more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis compared to mice receiving PBMCs from healthy control, which may enable assessment of therapeutics for patients with IL10R mutations (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, full immune reconstitution using CD34+ HSCS from patients with IL10R mutations, while unsuitable for assessing therapeutics for spontaneous intestinal inflammation, would be appropriate to screen gene therapy-based approaches designed to restore IL-10R signaling. This approach would permit information on vector insertion, selective advantage/disadvantage in targeted HSCs, and potentially predict efficacy as well as safety.

Figure 1: NSGAb°DR1 mice reconstituted with IL-10R2-deficient HSCs exhibit defective IL-10R signaling.

A) Representative flow cytometry dot plot depicting human lymphocytes previously gated on live, human CD45+ cells isolated from the spleen and mesenteric lymph node (mLN) of NSGAb°DR1 mice reconstituted using HSCs isolated from healthy control or IL-10R2-deficient patient. B) Splenic cells stimulated with 20 ngml−1 IL-10 for 15 minutes. Intracellular staining for phospho-STAT3 was determined on human CD3+ T cells gated on human CD45. C) Bone marrow-derived macrophage were generated from IL10RB or Control reconstituted NSGAb°DR1 mice and stimulated for 4 hours with LPS (10 ngml−1), IL-10 (20 ngml−1), or LPS following a 1 hr IL-10 pre-treatment. TNF was quantified by qPCR.

Figure 2: IL-10R1-deficient PBMC reconstituted humanized mice are more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis.

NSG-SGM3 mice were injected with 1×107 PBMCs isolated from healthy control or an IL-10R1-deficient patient, and on the next day administered 1.75% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in the drinking for water for 6 days and weighed daily. A) Percent weight loss of both groups (n=12–13 mice per group). B) Hematoxylin & Eosin stained colonic tissue sections from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded colonic blocks 6 days following DSS treatment (left) with intestinal inflammation quantified (right).

To our knowledge, other monogenic disorders such as WAS have not yet been assessed. The disease manifestation of WAS is predominately thrombocytopenia and although megakaryocytes are detected in the bone marrow of humanized mice, platelets are scarce due to rapid clearance by murine macrophage [79]. As in situ gene correction using genome editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 or next generation viral vectors for gene therapy-based approaches mature, other monogenic disorders including Omen syndrome and chronic granulomatous disease will find value in humanized mice reconstituted with patient cells as a first step towards developing effective targeting vectors and good manufacturing practices prior to clinical application [80]. Thus, using humanized mice to study monogenic immune disorders depends on the cell type(s) affected by the particular genetic mutation and the complete phenotype of the patient may not be recapitulated in current strains used to generate humanized mice.

3. Malignancies driven by mutations in immune cells

3.1. Hematological malignancies

Cancers of the hematopoietic system can occur sporadically or inherited in rare cases such as CEBPA-associated familial acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or mutations in KDM1A which increases risk for multiple myeloma. Somatic mutations in tumor suppressor genes give rise to multiple cytogenic alterations or translocations and have been linked to a variety of malignancies including lymphoma, lymphoid and myeloid leukemias, myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative disorders, and multiple myeloma. Over the last few decades, survival rates for many types of leukemias and lymphomas have improved due to early detection and therapeutic intervention. Nonetheless, some patients do not respond to current treatment regiments and the ability to assess novel therapeutics or combination therapies in humanized murine systems may enable personalized approaches to achieve remission and cure. In recent years, investigators have demonstrated utility of immune humanized mice to study hematological malignancies. Askmyr and colleagues generated NSG humanized mice using CD34+ HSCs transduced to express the BCR-ABL1 fusion, a gene encoding a constitutively active tyrosine kinase, that resulted in a block at the pre-B-cell stage similar to what was found in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia [81]. Similarly, the Ren lab generated humanized mice by injecting HSCs transduced with DEK-NUP214, a chimeric product of a t(6;9)(p22;q34) chromosome rearrangement found in a subset of AML patients, which phenocopied many aspects of the human condition [82]. In some instances, the model is not an ideal surrogate as the t(4;11)(q21;q23) translocation resulting in AF4-MLL fusion is not sufficient to cause leukemia when transduced CD34+ HSCs are transplanted into NSG mice [83]. It is suggested that intrinsic determinants may underlie different outcome observed in humanized mice.

3.2. A platform for immunotherapy

Harnessing the power of immune surveillance for targeted killing of malignant cells has become one of the most exciting developments in cancer research. Since the initial description of cell surface antigens in defining cells of different lineages [84], classification of various “clusters of differentiation” markers provide a potential target in which to direct immunogenicity. The seminal finding by Miller and colleagues describing monoclonal antibodies directed against a patients idiotype of a B cell lymphoma was able to induce remission was remarkable [85]. This finding led to the approval and commercialization in 1997 of the first monoclonal antibody (Rituximab) to treat relapsed or refractory CD20 positive low-grade or follicular B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and led to several additional antibody-based therapeutics coming to market in the years to come. Building upon this work, a combination of techniques converged using genetically modify T cells engineered to recognize and target specific antigens to treat patients with melanoma and lymphoma respectively [86, 87]. For these therapeutic strategies, humanized mice proved to be ideal models for both immunoglobulin depletion of B cells [88], as well as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells directed at epitopes expressed on malignant cells [89, 90].

In addition to immune-oncology, others have exploited genome editing of HSCs to demonstrate novel therapeutic strategies using humanized mice. Although antiretroviral therapy (ART) is effective in reducing viral titers in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), latent viral reservoirs necessitate continuous ART. Targeting the co-receptor that mediates HIV entry into CD4+ T cells using CRISPR/Cas9 in CD34+ HSCs, Mandal et al. demonstrated effective targeting of CCR5 that did not disrupt HSC pluripotent potential [91]. A sophisticated approach by Khamaikawin and colleagues transduced CD34+ HSCs with vectors expressing short hairpin RNAs against CCR5 and the long terminal repeat sequence of HIV and therapeutically administered these transduced HSCs to humanized mice previously infected with HIV. Downregulation of CCR5 was achieved and interestingly there was a selective advantage of gene-modified HSCs in HIV infected mice [91, 92]. Thus, these approaches in autologous HSCs may be an option to deplete latent reservoirs in HIV infected patients and has been a recent topic of debate using this technology in humans [93, 94].

Collectively, immune humanized mice have shown to recapitulate many features of human immunobiology. The opportunity to investigate novel approaches for immune oncology or other conditions including chronic infection in a tractable model system can help assess target engagement and even efficacy without risk to human subjects is of great clinical significance.

4. Considerations using HIS-mice and future developments

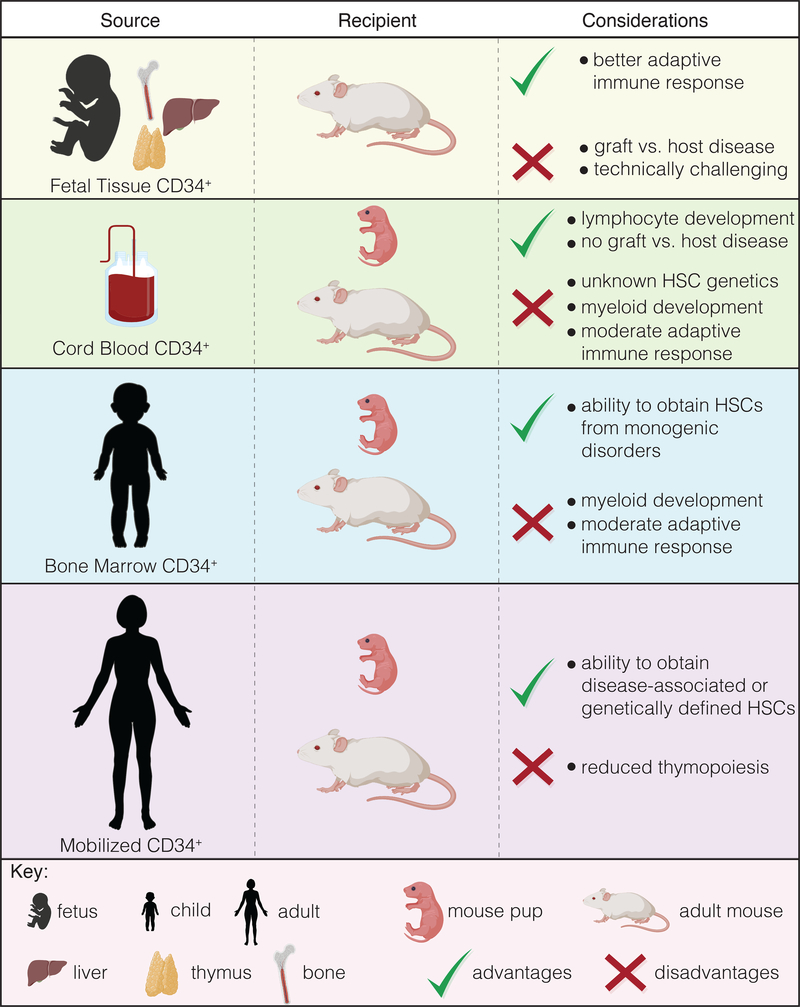

There are multiple cell types and methods that have been used to generate HIS mice, which are summarized in Table 3. The simplest method to establish the human immune system in immunocompromised mice is via injection of human PBMCs. In this model, transplanted human lymphocytes rapidly expand with few cells of myeloid lineage detected after a few days/weeks [95, 96]. The engrafted human T cells will become xeno-reactive and initiate a lethal xeno-graft-versus-host-disease (x-GVHD) within a few weeks but are valuable for studies investigating immunosuppressive therapies targeting human T cells [97]. Transplantation and repopulation using human CD34+ HSCs obtained from G-CSF mobilized blood, bone marrow, fetal liver, or umbilical cord blood all promote varying degrees of hematopoiesis, but engraftment is generally more robust when mice are reconstituted using cord blood or fetal liver sourced CD34+ cells [3, 98]. The bone marrow, liver, and thymus (BLT) system, in which autologous fetal tissue is used, yields the enhanced adaptive immune responses when compared to other models. However, complications from xGVHD as well as acquisition and funding of fetal tissue research introduces additional logistical and ethical considerations. Furthermore, while both BLT and CD34+ HSC models exhibit robust human immune cell chimerism after about 16 weeks, both models are relatively poor in myeloid cells development (due to limited cross-reactivity of key cytokines and/or growth factors) and circulation of human red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets due to clearance by murine cells [79, 99–101]. Finally, the source of CD34+ cells used to generate HIS mice has distinct advantages and disadvantages depending on the questions being addressed (Fig. 3).

Table 3:

Cell types and methods used to generate immune humanized mice

| Human cells | Injection route | Recipient | Conditioning |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBMCs | intravenous, intraperitoneal | Adult | - |

| CD4+ | intravenous, intraperitoneal | Adult | - |

| CD34+ | intrahepatic, facial vein, intracardiac intravenous |

1 day-old pup Adult |

sublethal irradiation sublethal irradiation |

| BLT | implantation of fetal liver & thymus under renal capsule, intravenous injection of autologous HSCs | Adult | sublethal irradiation |

Figure 3: Source of CD34+ HSCs and considerations in their use for generating immune-humanized mice.

Image generated using BioRender.

Effective strategies have been employed to address these limitations including exogenous administration of human cytokines [102], human cytokine-encoding plasmids [103, 104], or transgenic expression of human cytokines [105–107]. However, these methods may results in supraphysiological cytokine concentrations of human cytokines producing unwanted and artefactual effects as well as altered immune cell frequencies [105]. Elegant work from Richard Flavell’s group has used a knock-in approach whereby human cytokines/growth factors are targeted to the endogenous murine locus, ensuring faithful transcriptional regulation leading to improved HSC, myeloid, B cell, and NK cell development [101, 1081–12]. While the combination of multiple human cytokine “knock-ins” showed improved engraftment and human myeloid cell development, the lifespan of engrafted mice is shortened due to anemia resulting from human HSCs outcompeting murine HSC that are required for RBC production [108]. Strategies that enable sufficient human RBC development, possibly by expression of human erythropoietin, may overcome this limitation in the future. Other efforts include methods to improve T cell responses. Our group combined transgenic expression of HLA molecules in NSG mice deficient for murine MCH class I/II, which was required in order to recapitulate a T cell-mediated immunopathology [74, 113]. Similar approaches documented for NRG mice expressing HLA-DR4 also show evidence of improved T cell responses including immunoglobulin class switch recombination [114]. We have been curious if improved myeloid cell development in combination with T cell selection on human HLA molecules in the murine thymus would further improve adaptive immunity in humanized mice. Our group backcrossed the human CSF1 knock-in with NSG mice deficient for MHC molecules and instead express HLA-DQ8 and HLA-A2 and we will be assessing immune responses in the near future.

Finally, it is rewarding to see that the effort put forth by many investigators to develop and improve immune humanized murine systems has already yielded insights into human immunobiology that can ultimately inform clinical approaches to improve patient care. These xenobiotic platforms will only increase in utility and value for pre-clinical assessment of novel therapeutics directed at immune regulation, patient derived xenografts for solid tumors, as well as cancer immunotherapy in the coming years.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases DK106311 (to J.A.G.). The Academy Ter Meulen Grant from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Cultural Foundation Grant from Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation (to J.J.). The humanized mice experiments using IL-10R-deficient samples were funded in part by a joint Israel-US Binational Science Foundation (BSF) grant awarded to D.S.S. and S.B.S. We also thanks Alexandra E. Griffith, Rohini Emani, and Sandra M. Frei for technical assistance with humanized mouse studies.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Lin S, Lin Y, Nery JR, Urich MA, Breschi A, Davis CA, Dobin A, Zaleski C, Beer MA, Chapman WC, Gingeras TR, Ecker JR, Snyder MP, Comparison of the transcriptional landscapes between human and mouse tissues, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(48) (2014) 17224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yue F, Cheng Y, Breschi A, Vierstra J, Wu W, Ryba T, Sandstrom R, Ma Z, Davis C, Pope BD, Shen Y, Pervouchine DD, Djebali S, Thurman RE, Kaul R, Rynes E, Kirilusha A, Marinov GK, Williams BA, Trout D, Amrhein H, Fisher-Aylor K, Antoshechkin I, DeSalvo G, See LH, Fastuca M, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Dobin A, Prieto P, Lagarde J, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Denas O, Li K, Bender MA, Zhang M, Byron R, Groudine MT, McCleary D, Pham L, Ye Z, Kuan S, Edsall L, Wu YC, Rasmussen MD, Bansal MS, Kellis M, Keller CA, Morrissey CS, Mishra T, Jain D, Dogan N, Harris RS, Cayting P, Kawli T, Boyle AP, Euskirchen G, Kundaje A, Lin S, Lin Y, Jansen C, Malladi VS, Cline MS, Erickson DT, Kirkup VM, Learned K, Sloan CA, Rosenbloom KR, Lacerda de Sousa B, Beal K, Pignatelli M, Flicek P, Lian J, Kahveci T, Lee D, Kent WJ, Ramalho Santos M, Herrero J, Notredame C, Johnson A, Vong S, Lee K, Bates D, Neri F, Diegel M, Canfield T, Sabo PJ, Wilken MS, Reh TA, Giste E, Shafer A, Kutyavin T, Haugen E, Dunn D, Reynolds AP, Neph S, Humbert R, Hansen RS, De Bruijn M, Selleri L, Rudensky A, Josefowicz S, Samstein R, Eichler EE, Orkin SH, Levasseur D, Papayannopoulou T, Chang KH, Skoultchi A, Gosh S, Disteche C, Treuting P, Wang Y, Weiss MJ, Blobel GA, Cao X, Zhong S, Wang T, Good PJ, Lowdon RF, Adams LB, Zhou XQ, Pazin MJ, Feingold EA, Wold B, Taylor J, Mortazavi A, Weissman SM, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Snyder MP, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, Gilbert DM, Hardison RC, Beer MA, Ren B, Mouse EC, A comparative encyclopedia of DNA elements in the mouse genome, Nature 515(7527) (2014) 355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shultz LD, Brehm MA, Garcia-Martinez JV, Greiner DL, Humanized mice for immune system investigation: progress, promise and challenges, Nat Rev Immunol 12(11) (2012) 786–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zschaler J, Schlorke D, Arnhold J, Differences in innate immune response between man and mouse, Crit Rev Immunol 34(5) (2014) 433–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Perlman RL, Mouse models of human disease: An evolutionary perspective, Evol Med Public Health 2016(1) (2016) 170–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Warren HS, Tompkins RG, Moldawer LL, Seok J, Xu W, Mindrinos MN, Maier RV, Xiao W, Davis RW, Mice are not men, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(4) (2015) E345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Glanzmann E, Riniker P, [Essential lymphocytophthisis; new clinical aspect of infant pathology], Ann Paediatr 175(1–2) (1950) 1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Giblett ER, Anderson JE, Cohen F, Pollara B, Meuwissen HJ, Adenosine-deaminase deficiency in two patients with severely impaired cellular immunity, Lancet 2(7786) (1972) 1067–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ, A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse, Nature 301(5900) (1983) 527–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Araki R, Fujimori A, Hamatani K, Mita K, Saito T, Mori M, Fukumura R, Morimyo M, Muto M, Itoh M, Tatsumi K, Abe M, Nonsense mutation at Tyr-4046 in the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit of severe combined immune deficiency mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94(6) (1997) 2438–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blunt T, Gell D, Fox M, Taccioli GE, Lehmann AR, Jackson SP, Jeggo PA, Identification of a nonsense mutation in the carboxyl-terminal region of DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in the scid mouse, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93(19) (1996) 10285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jeggo PA, Jackson SP, Taccioli GE, Identification of the catalytic subunit of DNA dependent protein kinase as the product of the mouse scid gene, Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 217 (1996) 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Miller RD, Hogg J, Ozaki JH, Gell D, Jackson SP, Riblet R, Gene for the catalytic subunit of mouse DNA-dependent protein kinase maps to the scid locus, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92(23) (1995) 10792–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Custer RP, Bosma GC, Bosma MJ, Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in the mouse. Pathology, reconstitution, neoplasms, Am J Pathol 120(3) (1985) 464–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lieber MR, Hesse JE, Lewis S, Bosma GC, Rosenberg N, Mizuuchi K, Bosma MJ, Gellert M, The defect in murine severe combined immune deficiency: joining of signal sequences but not coding segments in V(D)J recombination, Cell 55(1) (1988) 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Malynn BA, Blackwell TK, Fulop GM, Rathbun GA, Furley AJ, Ferrier P, Heinke LB, Phillips RA, Yancopoulos GD, Alt FW, The scid defect affects the final step of the immunoglobulin VDJ recombinase mechanism, Cell 54(4) (1988) 453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB, Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency, Nature 335(6187) (1988) 256–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hesselton RM, Koup RA, Cromwell MA, Graham BS, Johns M, Sullivan JL, Human peripheral blood xenografts in the SCID mouse: characterization of immunologic reconstitution, J Infect Dis 168(3) (1993) 630–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Boehncke WH, Kock M, Hardt-Weinelt K, Wolter M, Kaufmann R, The SCID-hu xenogeneic transplantation model allows screening of anti-psoriatic drugs, Arch Dermatol Res 291(2–3) (1999) 104–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Raychaudhuri SP, Dutt S, Raychaudhuri SK, Sanyal M, Farber EM, Severe combined immunodeficiency mouse-human skin chimeras: a unique animal model for the study of psoriasis and cutaneous inflammation, Br J Dermatol 144(5) (2001) 931–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kish TM, Budgeon LR, Welsh PA, Howett MK, Immunological characterization of human vaginal xenografts in immunocompromised mice: development of a small animal model for the study of human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection, Am J Pathol 159(6) (2001) 2331–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bidanset DJ, Rybak RJ, Hartline CB, Kern ER, Replication of human cytomegalovirus in severe combined immunodeficient mice implanted with human retinal tissue, J Infect Dis 184(2) (2001) 192–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Aubard Y, Ovarian tissue xenografting, Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 108(1) (2003) 14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dekel B, Amariglio N, Kaminski N, Schwartz A, Goshen E, Arditti FD, Tsarfaty I, Passwell JH, Reisner Y, Rechavi G, Engraftment and differentiation of human metanephroi into functional mature nephrons after transplantation into mice is accompanied by a profile of gene expression similar to normal human kidney development, J Am Soc Nephrol 13(4) (2002) 977–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Furukawa T, Watanabe M, Kubota T, Yamaguchi H, Teramoto T, Ishibiki K, Kitajima M, Production of human immunoglobulin G reactive against human cancer in tumor-bearing mice with severe combined immunodeficiency reconstituted with human splenic tissues, Jpn J Cancer Res 83(8) (1992) 894–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Savidge TC, Morey AL, Ferguson DJ, Fleming KA, Shmakov AN, Phillips AD, Human intestinal development in a severe-combined immunodeficient xenograft model, Differentiation 58(5) (1995) 361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Shultz LD, Lieberman M, Weissman IL, The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function, Science 241(4873) (1988) 1632–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Namikawa R, Weilbaecher KN, Kaneshima H, Yee EJ, McCune JM, Long-term human hematopoiesis in the SCID-hu mouse, The Journal of experimental medicine 172(4) (1990) 1055–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hesselton RM, Greiner DL, Mordes JP, Rajan TV, Sullivan JL, Shultz LD, High levels of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell engraftment and enhanced susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in NOD/LtSz-scid/scid mice, J Infect Dis 172(4) (1995) 974–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Serreze DV, Gaedeke JW, Leiter EH, Hematopoietic stem-cell defects underlying abnormal macrophage development and maturation in NOD/Lt mice: defective regulation of cytokine receptors and protein kinase C, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90(20) (1993) 9625–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kataoka S, Satoh J, Fujiya H, Toyota T, Suzuki R, Itoh K, Kumagai K, Immunologic aspects of the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Abnormalities of cellular immunity, Diabetes 32(3) (1983) 247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ogasawara K, Hamerman JA, Hsin H, Chikuma S, Bour-Jordan H, Chen T, Pertel T, Carnaud C, Bluestone JA, Lanier LL, Impairment of NK cell function by NKG2D modulation in NOD mice, Immunity 18(1) (2003) 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang B, Geng YB, Wang CR, CD1-restricted NK T cells protect nonobese diabetic mice from developing diabetes, The Journal of experimental medicine 194(3) (2001) 313–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Solomon JB, Forbes MG, Solomon GR, A possible role for natural killer cells in providing protection against Plasmodium berghei in early stages of infection, Immunol Lett 9(6) (1985) 349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shultz LD, Schweitzer PA, Christianson SW, Gott B, Schweitzer IB, Tennent B, McKenna S, Mobraaten L, Rajan TV, Greiner DL, et al. , Multiple defects in innate and adaptive immunologic function in NOD/LtSz-scid mice, J Immunol 154(1) (1995) 180–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wakeland EK, Hunting autoimmune disease genes in NOD: early steps on a long road to somewhere important (hopefully), J Immunol 193(1) (2014) 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cao X, Shores EW, Hu-Li J, Anver MR, Kelsall BL, Russell SM, Drago J, Noguchi M, Grinberg A, Bloom ET, et al. , Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain, Immunity 2(3) (1995) 223–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].DiSanto JP, Muller W, Guy-Grand D, Fischer A, Rajewsky K, Lymphoid development in mice with a targeted deletion of the interleukin 2 receptor gamma chain, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92(2) (1995) 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, Kotb M, Gillies SD, King M, Mangada J, Greiner DL, Handgretinger R, Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells, J Immunol 174(10) (2005) 6477–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, Suzue K, Kawahata M, Hioki K, Ueyama Y, Koyanagi Y, Sugamura K, Tsuji K, Heike T, Nakahata T, NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells, Blood 100(9) (2002) 3175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pearson T, Shultz LD, Miller D, King M, Laning J, Fodor W, Cuthbert A, Burzenski L, Gott B, Lyons B, Foreman O, Rossini AA, Greiner DL, Non-obese diabetic-recombination activating gene-1 (NOD-Rag1 null) interleukin (IL)-2 receptor common gamma chain (IL2r gamma null) null mice: a radioresistant model for human lymphohaematopoietic engraftment, Clin Exp Immunol 154(2) (2008) 27084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Traggiai E, Chicha L, Mazzucchelli L, Bronz L, Piffaretti JC, Lanzavecchia A, Manz MG, Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice, Science 304(5667) (2004) 104–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Denton PW, Nochi T, Lim A, Krisko JF, Martinez-Torres F, Choudhary SK, Wahl A, Olesen R, Zou W, Di Santo JP, Margolis DM, Garcia JV, IL-2 receptor gamma-chain molecule is critical for intestinal T-cell reconstitution in humanized mice, Mucosal Immunol 5(5) (2012) 555–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Brehm MA, Cuthbert A, Yang C, Miller DM, DiIorio P, Laning J, Burzenski L, Gott B, Foreman O, Kavirayani A, Herlihy M, Rossini AA, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Parameters for establishing humanized mouse models to study human immunity: analysis of human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment in three immunodeficient strains of mice bearing the IL2rgamma(null) mutation, Clin Immunol 135(1) (2010) 84–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Brown EJ, Frazier WA, Integrin-associated protein (CD47) and its ligands, Trends Cell Biol 11(3) (2001) 130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Barclay AN, Brown MH, The SIRP family of receptors and immune regulation, Nat Rev Immunol 6(6) (2006) 457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yamauchi T, Takenaka K, Urata S, Shima T, Kikushige Y, Tokuyama T, Iwamoto C, Nishihara M, Iwasaki H, Miyamoto T, Honma N, Nakao M, Matozaki T, Akashi K, Polymorphic Sirpa is the genetic determinant for NOD-based mouse lines to achieve efficient human cell engraftment, Blood 121(8) (2013) 1316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Legrand N, Huntington ND, Nagasawa M, Bakker AQ, Schotte R, Strick-Marchand H, de Geus SJ, Pouw SM, Bohne M, Voordouw A, Weijer K, Di Santo JP, Spits H, Functional CD47/signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRP(alpha)) interaction is required for optimal human T- and natural killer- (NK) cell homeostasis in vivo, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(32) (2011) 13224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Strowig T, Rongvaux A, Rathinam C, Takizawa H, Borsotti C, Philbrick W, Eynon EE, Manz MG, Flavell RA, Transgenic expression of human signal regulatory protein alpha in Rag2−/−gamma(c)−/− mice improves engraftment of human hematopoietic cells in humanized mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(32) (2011) 13218–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, Kelly TE, Saulsbury FT, Chance PF, Ochs HD, The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3, Nat Genet 27(1) (2001) 20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Caudy AA, Reddy ST, Chatila T, Atkinson JP, Verbsky JW, CD25 deficiency causes an immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked-like syndrome, and defective IL-10 expression from CD4 lymphocytes, J Allergy Clin Immunol 119(2) (2007) 482–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wildin RS, Ramsdell F, Peake J, Faravelli F, Casanova JL, Buist N, Levy-Lahad E, Mazzella M, Goulet O, Perroni L, Bricarelli FD, Byrne G, McEuen M, Proll S, Appleby M, Brunkow ME, X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy, Nat Genet 27(1) (2001) 18–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Paust S, Lu L, McCarty N, Cantor H, Engagement of B7 on effector T cells by regulatory T cells prevents autoimmune disease, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(28) (2004) 10398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F, Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation, The Journal of experimental medicine 192(2) (2000) 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Franke A, Balschun T, Karlsen TH, Sventoraityte J, Nikolaus S, Mayr G, Domingues FS, Albrecht M, Nothnagel M, Ellinghaus D, Sina C, Onnie CM, Weersma RK, Stokkers PCF, Wijmenga C, Gazouli M, Strachan D, McArdle WL, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Rosenstiel P, Krawczak M, Vatn MH, Mathew CG, Schreiber S, Grp IS, Sequence variants in IL10, ARPC2 and multiple other loci contribute to ulcerative colitis susceptibility, Nature Genetics 40(11) (2008) 1319–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, Gertz EM, Schaffer AA, Noyan F, Perro M, Diestelhorst J, Allroth A, Murugan D, Hatscher N, Pfeifer D, Sykora KW, Sauer M, Kreipe H, Lacher M, Nustede R, Woellner C, Baumann U, Salzer U, Koletzko S, Shah N, Segal AW, Sauerbrey A, Buderus S, Snapper SB, Grimbacher B, Klein C, Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor, N Engl J Med 361(21) (2009) 2033–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Avitzur Y, Guo C, Mastropaolo LA, Bahrami E, Chen H, Zhao Z, Elkadri A, Dhillon S, Murchie R, Fattouh R, Huynh H, Walker JL, Wales PW, Cutz E, Kakuta Y, Dudley J, Kammermeier J, Powrie F, Shah N, Walz C, Nathrath M, Kotlarz D, Puchaka J, Krieger JR, Racek T, Kirchner T, Walters TD, Brumell JH, Griffiths AM, Rezaei N, Rashtian P, Najafi M, Monajemzadeh M, Pelsue S, McGovern DP, Uhlig HH, Schadt E, Klein C, Snapper SB, Muise AM, Mutations in tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A result in a severe form of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease, Gastroenterology 146(4) (2014) 1028–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Colon AL, Menchen LA, Hurtado O, De Cristobal J, Lizasoain I, Leza JC, Lorenzo P, Moro MA, Implication of TNF-alpha convertase (TACE/ADAM17) in inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and inflammation in an experimental model of colitis, Cytokine 16(6) (2001) 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Villa A, Santagata S, Bozzi F, Giliani S, Frattini A, Imberti L, Gatta LB, Ochs HD, Schwarz K, Notarangelo LD, Vezzoni P, Spanopoulou E, Partial V(D)J recombination activity leads to Omenn syndrome, Cell 93(5) (1998) 885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Arredondo-Vega FX, Santisteban I, Daniels S, Toutain S, Hershfield MS, Adenosine deaminase deficiency: genotype-phenotype correlations based on expressed activity of 29 mutant alleles, Am J Hum Genet 63(4) (1998) 1049–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Frucht DM, Gadina M, Jagadeesh GJ, Aksentijevich I, Takada K, Bleesing JJ, Nelson J, Muul LM, Perham G, Morgan G, Gerritsen EJ, Schumacher RF, Mella P, Veys PA, Fleisher TA, Kaminski ER, Notarangelo LD, O’Shea JJ, Candotti F, Unexpected and variable phenotypes in a family with JAK3 deficiency, Genes Immun 2(8) (2001) 422–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Pepper AE, Buckley RH, Small TN, Puck JM, Two mutational hotspots in the interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain gene causing human X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, Am J Hum Genet 57(3) (1995) 564–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Roos D, de Boer M, Kuribayashi F, Meischl C, Weening RS, Segal AW, Ahlin A, Nemet K, Hossle JP, Bernatowska-Matuszkiewicz E, Middleton-Price H, Mutations in the X-linked and autosomal recessive forms of chronic granulomatous disease, Blood 87(5) (1996) 1663–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Roos D, Kuhns DB, Maddalena A, Bustamante J, Kannengiesser C, de Boer M, van Leeuwen K, Koker MY, Wolach B, Roesler J, Malech HL, Holland SM, Gallin JI, Stasia MJ, Hematologically important mutations: the autosomal recessive forms of chronic granulomatous disease (second update), Blood Cells Mol Dis 44(4) (2010) 291–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, Feld JJ, Pike KM, Marciano BE, Uzel G, DeRavin SS, Priel DA, Soule BP, Zarember KA, Malech HL, Holland SM, Gallin JI, Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease, N Engl J Med 363(27) (2010) 2600–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, Freeman AF, Demidowich A, Davis J, Turner ML, Anderson VL, Darnell DN, Welch PA, Kuhns DB, Frucht DM, Malech HL, Gallin JI, Kobayashi SD, Whitney AR, Voyich JM, Musser JM, Woellner C, Schaffer AA, Puck JM, Grimbacher B, STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome, N Engl J Med 357(16) (2007) 1608–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Minegishi Y, Saito M, Tsuchiya S, Tsuge I, Takada H, Hara T, Kawamura N, Ariga T, Pasic S, Stojkovic O, Metin A, Karasuyama H, Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome, Nature 448(7157) (2007) 1058–U10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chiossone L, Audonnet S, Chetaille B, Chasson L, Farnarier C, Berda-Haddad Y, Jordan S, Koszinowski UH, Dalod M, Mazodier K, Novick D, Dinarello CA, Vivier E, Kaplanski G, Protection from inflammatory organ damage in a murine model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis using treatment with IL-18 binding protein, Front Immunol 3 (2012) 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Cote M, Menager MM, Burgess A, Mahlaoui N, Picard C, Schaffner C, Al-Manjomi F, AlHarbi M, Alangari A, Le Deist F, Gennery AR, Prince N, Cariou A, Nitschke P, Blank U, El-Ghazali G, Menasche G, Latour S, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G, Munc18–2 deficiency causes familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 and impairs cytotoxic granule exocytosis in patient NK cells, J Clin Invest 119(12) (2009) 3765–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Botto M, Dell’Agnola C, Bygrave AE, Thompson EM, Cook HT, Petry F, Loos M, Pandolfi PP, Walport MJ, Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies, Nature Genetics 19(1) (1998) 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Blanchong CA, Chung EK, Rupert KL, Yang Y, Yang ZY, Zhou B, Moulds JM, Yu CY, Genetic, structural and functional diversities of human complement components C4A and C4B and their mouse homologues, Slp and C4, International Immunopharmacology 1(3) (2001) 365–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Devriendt K, Kim AS, Mathijs G, Frints SGM, Schwartz M, Van den Oord JJ, Verhoef GEG, Boogaerts MA, Fryns JP, You DQ, Rosen MK, Vandenberghe P, Constitutively activating mutation in WASP causes X-linked severe congenital neutropenia, Nature Genetics 27(3) (2001) 313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ochs HD, Thrasher AJ, The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 117(4) (2006) 725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Goettel JA, Biswas S, Lexmond WS, Yeste A, Passerini L, Patel B, Yang S, Sun J, Ouahed J, Shouval DS, McCann KJ, Horwitz BH, Mathis D, Milford EL, Notarangelo LD, Roncarolo MG, Fiebiger E, Marasco WA, Bacchetta R, Quintana FJ, Pai SY, Klein C, Muise AM, Snapper SB, Fatal autoimmunity in mice reconstituted with human hematopoietic stem cells encoding defective FOXP3, Blood 125(25) (2015) 3886–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Vudattu NK, Waldron-Lynch F, Truman LA, Deng S, Preston-Hurlburt P, Torres R, Raycroft MT, Mamula MJ, Herold KC, Humanized mice as a model for aberrant responses in human T cell immunotherapy, J Immunol 193(2) (2014) 587–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Goettel JA, Kotlarz D, Emani R, Canavan JB, Konnikova L, Illig D, Frei SM, Field M, Kowalik M, Peng K, Gringauz J, Mitsialis V, Wall SM, Tsou A, Griffith AE, Huang Y, Friedman JR, Towne JE, Plevy SE, O’Hara Hall A, Snapper SB, Low-Dose Interleukin-2 Ameliorates Colitis in a Preclinical Humanized Mouse Model, Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 8(2) (2019) 193–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Neven B, Mamessier E, Bruneau J, Kaltenbach S, Kotlarz D, Suarez F, Masliah-Planchon J, Billot K, Canioni D, Frange P, Radford-Weiss I, Asnafi V, Murugan D, Bole C, Nitschke P, Goulet O, Casanova JL, Blanche S, Picard C, Hermine O, Rieux-Laucat F, Brousse N, Davi F, Baud V, Klein C, Nadel B, Ruemmele F, Fischer A, A Mendelian predisposition to B-cell lymphoma caused by IL-10R deficiency, Blood 122(23) (2013) 3713–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Shouval DS, Ebens CL, Murchie R, McCann K, Rabah R, Klein C, Muise AM, Snapper SB, Large B-Cell Lymphoma in an Adolescent Patient With Interleukin-10 Receptor Deficiency and History of Infantile Inflammatory Bowel Disease, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 63(1) (2016) e15–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Hu Z, Yang YG, Full reconstitution of human platelets in humanized mice after macrophage depletion, Blood 120(8) (2012) 1713–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Naumann N, De Ravin SS, Choi U, Moayeri M, Whiting-Theobald N, Linton GF, Ikeda Y, Malech HL, Simian immunodeficiency virus lentivector corrects human X-linked chronic granulomatous disease in the NOD/SCID mouse xenograft, Gene Ther 14(21) (2007) 1513–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Askmyr M, Agerstam H, Lilljebjorn H, Hansen N, Karlsson C, von Palffy S, Landberg N, Hogberg C, Lassen C, Rissler M, Richter J, Ehinger M, Jaras M, Fioretos T, Modeling chronic myeloid leukemia in immunodeficient mice reveals expansion of aberrant mast cells and accumulation of pre-B cells, Blood Cancer J 4 (2014) e269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Qin H, Malek S, Cowell JK, Ren M, Transformation of human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells with DEK-NUP214 induces AML in an immunocompromised mouse model, Oncogene 35(43) (2016) 5686–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Prieto C, Marschalek R, Kuhn A, Bursen A, Bueno C, Menendez P, The AF4-MLL fusion transiently augments multilineage hematopoietic engraftment but is not sufficient to initiate leukemia in cord blood CD34(+) cells, Oncotarget 8(47) (2017) 81936–81941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Boyse EA, Miyazawa M, Aoki T, Old LJ, Ly-A and Ly-B: two systems of lymphocyte isoantigens in the mouse, Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 170(1019) (1968) 175–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Miller RA, Maloney DG, Warnke R, Levy R, Treatment of B-cell lymphoma with monoclonal anti-idiotype antibody, N Engl J Med 306(9) (1982) 517–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA, Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes, Science 314(5796) (2006) 126–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Till BG, Jensen MC, Wang J, Chen EY, Wood BL, Greisman HA, Qian X, James SE, Raubitschek A, Forman SJ, Gopal AK, Pagel JM, Lindgren CG, Greenberg PD, Riddell SR, Press OW, Adoptive immunotherapy for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma using genetically modified autologous CD20-specific T cells, Blood 112(6) (2008) 2261–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lux A, Seeling M, Baerenwaldt A, Lehmann B, Schwab I, Repp R, Meidenbauer N, Mackensen A, Hartmann A, Heidkamp G, Dudziak D, Nimmerjahn F, A humanized mouse identifies the bone marrow as a niche with low therapeutic IgG activity, Cell Rep 7(1) (2014) 236–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Jin CH, Xia J, Rafiq S, Huang X, Hu Z, Zhou X, Brentjens RJ, Yang YG, Modeling anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in humanized mice with human immunity and autologous leukemia, EBioMedicine 39 (2019) 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Pizzitola I, Anjos-Afonso F, Rouault-Pierre K, Lassailly F, Tettamanti S, Spinelli O, Biondi A, Biagi E, Bonnet D, Chimeric antigen receptors against CD33/CD123 antigens efficiently target primary acute myeloid leukemia cells in vivo, Leukemia 28(8) (2014) 1596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Mandal PK, Ferreira LM, Collins R, Meissner TB, Boutwell CL, Friesen M, Vrbanac V, Garrison BS, Stortchevoi A, Bryder D, Musunuru K, Brand H, Tager AM, Allen TM, Talkowski ME, Rossi DJ, Cowan CA, Efficient ablation of genes in human hematopoietic stem and effector cells using CRISPR/Cas9, Cell Stem Cell 15(5) (2014) 643–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Khamaikawin W, Shimizu S, Kamata M, Cortado R, Jung Y, Lam J, Wen J, Kim P, Xie Y, Kim S, Arokium H, Presson AP, Chen ISY, An DS, Modeling Anti-HIV-1 HSPC-Based Gene Therapy in Humanized Mice Previously Infected with HIV-1, Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 9 (2018) 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Cyranoski D, Ledford H, Genome-edited baby claim provokes international outcry, Nature 563(7733) (2018) 607–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ledford H, CRISPR babies: when will the world be ready?, Nature 570(7761) (2019) 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ito R, Katano I, Kawai K, Hirata H, Ogura T, Kamisako T, Eto T, Ito M, Highly sensitive model for xenogenic GVHD using severe immunodeficient NOG mice, Transplantation 87(11) (2009) 1654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].King MA, Covassin L, Brehm MA, Racki W, Pearson T, Leif J, Laning J, Fodor W, Foreman O, Burzenski L, Chase TH, Gott B, Rossini AA, Bortell R, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Human peripheral blood leucocyte non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain gene mouse model of xenogeneic graft-versus-host-like disease and the role of host major histocompatibility complex, Clin Exp Immunol 157(1) (2009) 104–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Kenney LL, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Brehm MA, Humanized Mouse Models for Transplant Immunology, Am J Transplant 16(2) (2016) 389–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Brehm MA, Shultz LD, Human allograft rejection in humanized mice: a historical perspective, Cell Mol Immunol 9(3) (2012) 225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Theocharides AP, Rongvaux A, Fritsch K, Flavell RA, Manz MG, Humanized hemato-lymphoid system mice, Haematologica 101(1) (2016) 5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Suzuki K, Hiramatsu H, Fukushima-Shintani M, Heike T, Nakahata T, Efficient assay for evaluating human thrombopoiesis using NOD/SCID mice transplanted with cord blood CD34+ cells, Eur J Haematol 78(2) (2007) 123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Willinger T, Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Auerbach W, Eynon EE, Stevens S, Manz MG, Flavell RA, Human IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice support human alveolar macrophage development and human immune responses in the lung, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(6) (2011) 2390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Huntington ND, Legrand N, Alves NL, Jaron B, Weijer K, Plet A, Corcuff E, Mortier E, Jacques Y, Spits H, Di Santo JP, IL-15 trans-presentation promotes human NK cell development and differentiation in vivo, The Journal of experimental medicine 206(1) (2009) 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Li Y, Chen Q, Zheng D, Yin L, Chionh YH, Wong LH, Tan SQ, Tan TC, Chan JK, Alonso S, Dedon PC, Lim B, Chen J, Induction of functional human macrophages from bone marrow promonocytes by M-CSF in humanized mice, J Immunol 191(6) (2013) 3192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Chen Q, Khoury M, Chen J, Expression of human cytokines dramatically improves reconstitution of specific human-blood lineage cells in humanized mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(51) (2009) 21783–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Nicolini FE, Cashman JD, Hogge DE, Humphries RK, Eaves CJ, NOD/SCID mice engineered to express human IL-3, GM-CSF and Steel factor constitutively mobilize engrafted human progenitors and compromise human stem cell regeneration, Leukemia 18(2) (2004) 341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Brehm MA, Racki WJ, Leif J, Burzenski L, Hosur V, Wetmore A, Gott B, Herlihy M, Ignotz R, Dunn R, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Engraftment of human HSCs in nonirradiated newborn NOD-scid IL2rgamma null mice is enhanced by transgenic expression of membrane-bound human SCF, Blood 119(12) (2012) 2778–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ito R, Takahashi T, Katano I, Kawai K, Kamisako T, Ogura T, Ida-Tanaka M, Suemizu H, Nunomura S, Ra C, Mori A, Aiso S, Ito M, Establishment of a human allergy model using human IL-3/GM-CSF-transgenic NOG mice, J Immunol 191(6) (2013) 2890–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Rongvaux A, Willinger T, Martinek J, Strowig T, Gearty SV, Teichmann LL, Saito Y, Marches F, Halene S, Palucka AK, Manz MG, Flavell RA, Development and function of human innate immune cells in a humanized mouse model, Nat Biotechnol 32(4) (2014) 364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Rongvaux A, Willinger T, Takizawa H, Rathinam C, Auerbach W, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Eynon EE, Stevens S, Manz MG, Flavell RA, Human thrombopoietin knockin mice efficiently support human hematopoiesis in vivo, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(6) (2011) 2378–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Herndler-Brandstetter D, Shan L, Yao Y, Stecher C, Plajer V, Lietzenmayer M, Strowig T, de Zoete MR, Palm NW, Chen J, Blish CA, Frleta D, Gurer C, Macdonald LE, Murphy AJ, Yancopoulos GD, Montgomery RR, Flavell RA, Humanized mouse model supports development, function, and tissue residency of human natural killer cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(45) (2017) E9626–E9634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Rathinam C, Poueymirou WT, Rojas J, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Rongvaux A, Eynon EE, Manz MG, Flavell RA, Efficient differentiation and function of human macrophages in humanized CSF-1 mice, Blood 118(11) (2011) 3119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Yu H, Borsotti C, Schickel JN, Zhu S, Strowig T, Eynon EE, Frleta D, Gurer C, Murphy AJ, Yancopoulos GD, Meffre E, Manz MG, Flavell RA, A novel humanized mouse model with significant improvement of class-switched, antigen-specific antibody production, Blood 129(8) (2017) 959–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Goettel JA, Gandhi R, Kenison JE, Yeste A, Murugaiyan G, Sambanthamoorthy S, Griffith AE, Patel B, Shouval DS, Weiner HL, Snapper SB, Quintana FJ, AHR Activation Is Protective against Colitis Driven by T Cells in Humanized Mice, Cell Rep 17(5) (2016) 1318–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Danner R, Chaudhari SN, Rosenberger J, Surls J, Richie TL, Brumeanu TD, Casares S, Expression of HLA class II molecules in humanized NOD.Rag1KO.IL2RgcKO mice is critical for development and function of human T and B cells, PLoS One 6(5) (2011) e19826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]