Abstract

Background:

In Kenya, the prevalence of alcohol use disorder (AUD) is close to 6%, but a notable treatment gap persists. AUD is especially pronounced among men, leading to negative consequences at both individual and family levels. This study examines the experiences of problem-drinking fathers in Kenya regarding previous treatment-seeking related to alcohol use. Experiences and dynamics of the family are also explored, as they pertain to treatment-seeking experiences.

Methods:

In Eldoret, Kenya, semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 11 families with a male exhibiting problem drinking, his spouse, and one child. Thematic content analysis was used to examine themes related to barriers and facilitators to treatment.

Results:

Participants only reported informal help received from family and community members; they exhibited little awareness of available formal treatments. Families were both deeply affected by alcohol use and actively involved in help-seeking. Indeed, fathers’ experiences are described as help-accepting rather than help-seeking. Three overarching themes emerged from the results: poverty, people, and practices. Poverty could be a motivator to accept help to support one’s family financially, but stress from lack of work also drove drinking behaviours. People were also crucial, as both barriers and facilitators, of help-accepting. Negative help strategies or peer influence deterred the father from accepting help to quit. Positive motivation, social support, and stigma against drinking were motivators. Practices that were culturally salient, such as religiosity and gender roles, facilitated help acceptance. Overall, most help efforts were short-term and only lead to very short-term behaviour change.

Conclusion:

Families and communities are active in help provision for problem-drinking men in Kenya, though results confirm remaining need for effective interventions. Future interventions could benefit from recognizing the role of family to aid in treatment-engagement and attending to the importance of poverty, people, and practices in designing treatment strategies.

Keywords: Problem-drinking, Barriers, Facilitators, Fathers, Family

Introduction

In Kenya, close to 6% of the population is reported to have alcohol use disorder (AUD) (NACADA, 2012). Cross-culturally, studies have found that men consume higher rates of alcohol and are disproportionately impacted by harmful consumption compared to women (Wilsnack, Vogeltanz, Wilsnack, & Harris, 2000). Gender disparities in alcohol consumption might be exacerbated by cultural influences, such as strict gender roles and/or patriarchal social structures (WHO, 2005a). In a study in Kenya, socially constructed gender roles were found to be associated with higher alcohol consumption among young men (Mugisha, Arinaitwe-Mugisha, & Hagembe, 2003).

Systematic reviews on harmful alcohol consumption have shown negative impacts on physical and mental health at both the individual and family level (Rehm et. al., 2010; Steel et. al., 2014). On the individual level, men are more likely to suffer from liver damage, cancer, and heart failure; psychological consequences include depression and anxiety (Bofetta P & Hasibe M, 2006; Laonigro, Correale, Di Biase, & Altomare, 2009). At the family level, high paternal alcohol use is associated with domestic violence and early onset of substance abuse among offspring (Leonord & Eiden, 2007; Schafer & Koyiet, 2018).

Treatments in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs)

Treatment for AUDs is scarce in LMICs, typically consisting of private clinics in urban areas with high fee structures. In some countries, there are government-funded clinics, but these have poor efficacy (Benegal et. al. 2009; Myers, Louw, & Pasche, 2010). Consequently, the median gap in treatment - between individuals who require treatment but don’t receive it - in LMICs is an estimated 78.1% (Benegal et.al, 2009).

In the past two decades, there has been an expansion of non-medical treatment interventions for AUDs in LMICs, often through Christian ministries (Salwan & Katz, 2014). However, there is a scarcity of information on the effectiveness of spiritual and church-based treatment interventions in low-resource settings. A study by Stahler, Kirby, and Kerwin (2007) in a High-Income Country (HIC) setting, suggests that such interventions, which incorporate church communities for culturally relevant group activities and offer personal mentoring by church volunteers, led to higher retention and better outcomes at 6-month follow up for substance abusing individuals.

Kenya currently has few counseling and rehabilitation centers, all located in urban areas. Most of these locations provide inpatient and outpatient services for mental health and/or addiction problems (NACADA, 2017). The National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA) in Kenya has also established a hotline for alcohol and drug users, which provides free counseling over the phone, with referrals to rehabilitation facilities. Despite these efforts, the percent of the population seeking treatment remains low (NACADA, 2010).

Familial Effects of Paternal Problem Alcohol Use

Findings from HICs have shown that a history of paternal alcohol abuse is a direct predictor of child mental disorders and early onset of substance use in adolescents (Jääskeläinen, Holmila, Notkola, & Raitasalo, 2016; Obot, Wagner, & Anthony, 2001). Alcohol abuse is linked with child maltreatment and neglect, harsh parenting, and lack of stimulation at home (Keller et.al., 2009; Lee, 2013; Meinck et. al., 2015; Neger et.al., 2015). Studies from several LMICs reveal that an increase in alcohol consumption by the husband brought an increased risk of intimate partner violence, poor co-parenting, poor communication, and marital conflict (Changalwa et. al., 2012; Jeyaseelan et. al., 2004).

Family can affect treatment-seeking behaviour in positive or negative ways. In a systematic review of stigma in relation to treatment for AUD, Keyes et. al. (2010) found that closeness among family members predicted lower stigma experienced by the help-seeking individual. According to a NACADA (2010) report, approximately 62% of alcohol-using individuals sought informal counseling from a family member.

Barriers and Facilitators to Treatment

Current literature on barriers and facilitators to alcohol treatment, from the perspective of the alcohol user, is largely based on data from HICs. Most commonly reported themes include stigma, service accessibility (high cost, distance, and efficacy), culture, religion, perceived need, finances, and family-related factors, such as family functioning, couple’s relationship, and father-child relationship (Benegal, Chand, & Obot, 2009; Herbert et al., 2018; Meade et al., 2015; Saunders, Zygowicz, & D’Angelo, 2006; Tucker, Vuchinich, & Rippins, 2004). In a mixed-methods study by Meade et. al. (2015), methamphetamine users reported denial, fear of stigma, cost, and perceived control over addiction as barriers to substance abuse treatment in South Africa. There is currently very little literature on person-related barriers and facilitators in LMICs, but some indicators surfaced through qualitative research on alcohol consumption, such as fear of stigma compelling individuals to refrain from consuming alcohol, and lack of affordable and efficacious facilities (NACADA, 2010).

The Current Study

In the absence of accessible formal treatment, it is vital to understand existing patterns, sources, and perceptions of help. The objective of this study was to examine the perceptions of fathers engaged in problem drinking and their families about previous experiences with seeking or receiving help related to alcohol use. We explored both formal and informal sources of help, barriers and facilitators to accepting help, and perceptions of effectiveness. A unique aspect of this study is the examination of family dynamics as they pertain to these help-related experiences. The broader aim of the study is to inform the development and implementation of a community-based intervention to aid in reducing of problem among problem drinking fathers.

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted in Kenya in collaboration with the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) consortium. Participants were recruited from Eldoret Town and surrounding peri-urban communities in Uasin Gishu County. This qualitative study was nested within - and data collection occurred prior to - a pilot intervention trial to reduce problem drinking and increase positive family interactions for alcohol abusing fathers in Kenya. Ethical review of the study was conducted by the Duke University and Moi University Institutional Review Board.

Fathers participating in the intervention, their spouses, and one of their children participated in pre-intervention interviews. To be included in the study, men needed to (a) be responsible for the care of a child 8–17 years old, (b) sleep the majority of nights with the family (i.e. not be separated from spouse or have employment in a different location), and (c) engage in problem drinking as indicated by a score between 3 to 19 on the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Bush et. al., 1998). Men who scored >19, which indicated the likelihood of alcohol dependence, were excluded, as the severity of their AUD was likely beyond the scope of the pilot intervention. The spouse was eligible if over age 18. Exclusion criteria included reporting extreme violence in the home that could lead to imminent danger or brewing alcohol in the home.

Data Collection

Recruitment was performed by local pastors and community leaders from communities within Eldoret (i.e. Ilula and Soroyot); each was asked to identify and then approach men within the community that would benefit from the intervention without disclosing any identifiable details to the research team. If the father was interested, then the pastor or leader provided the study team with their contact information. A research staff member then visited interested fathers to obtain consent from the father, spouse and child and basic demographic information for all members. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between August-November 2017. The interview guides included open-ended questions on barriers and facilitators, with specific probes drawn from existing literature.

Four bilingual Kenyan research assistants (RAs), 2 male and 2 female, conducted interviews. As a part of their training, practice interviews were conducted with community members. Each community member provided feedback on the understandability and cultural appropriateness of the questions; this led to further refinement of the interview guide. The interview guide broadly covered father’s past experiences of help (i.e. identifying individuals or organizations), role of the family/community in acting as barriers or facilitators to help, perceptions on drinking and receiving help (past and future), and perceived impacts of drinking on family/community.

Interviews took place individually in a private room at the participant’s home. Each interview lasted between 20 to 100 minutes (mean 60 minutes) and was audio recorded. Interviewers were not gender matched to the participants. Each participant received non-monetary compensation worth 100 Kenyan Shillings (~ 1 USD), such as a bag of rice, mobile phone airtime, or pencils for children. Non-monetary compensation was provided to mitigate added spending on alcohol consumption.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed in Swahili and translated into English, with interview summaries written by the RAs immediately after each interview. Interview summaries were written in narrative form to summarize and organize the data and to identify patterns. Weekly meetings were conducted by the research team (investigators, RAs, and transcribers) to provide ongoing supervision of interviews and conduct analysis with local input from the team. Interviewer input and interview summaries were used to identify new themes to add to the interview guide; for example, adding questions related to drinking patterns within the work environment.

Thematic content analysis was used to analyze salient themes in the data. The transcripts were reviewed and analytic summaries written. Based on patterns observed in transcript/interview summaries, initial codes were generated. Then, inter-rater reliability (IRR) in applying codes was established between the first author and a member of the team unfamiliar with the data. A kappa score of .72 for the IRR was achieved, and all transcripts were then coded by the first author using NVivo11 software. Summative descriptions were written for each theme and then discussed with the field team to assure accuracy of interpretation and articulation.

Results

A total of 31 individuals participated in semi-structured interviews, including 11 men, 11 women, and 9 children. The average age was 38 years for fathers, 32 for mothers, and 12 for children. All but one of the children were enrolled in primary school. The majority of the adults in the sample were married, casual workers, and belonging to the Kalenjin tribe. Households reported an average income of 1,905 Ksh (~19 USD) per week (range: 500 Ksh (~5 USD) to 7,200 Ksh (~72 USD)). Almost all of the participants reported fathers mostly consuming locally brewed alcohol (e.g., chang’aa and busaa; Mkuu et al., 2019). The average AUDIT score for fathers was 16 (high risk or harmful level), with the scores ranging from 9 to 19.

Experiences of Drinking

Individual

Almost all fathers reported negative experiences related to alcohol consumption and therefore desired to quit, but drinking was often described as a necessary tool to cope with mental and physical stress. Despite these perceived benefits of drinking, most fathers reported being unable to control the amount of alcohol they consumed and therefore faced negative consequences. One father reported, “Usually by [the end of the work day] I have a lot of money; this triggers me to decide and go to drink in hiding, for I wouldn’t like my wife to know about it. Once I have gone [to the alcohol den], I will not be able to control the amount of alcohol consumption; I will definitely overdo it.” Due to this lack of control, most fathers reported spending their daily earnings on alcohol (Figure 1). In many cases, the fathers reported spending all their money on alcohol or, if they didn’t have any money, that their friends offered to buy alcohol for them. Apart from the financial strains on the family, excessive drinking sometimes led fathers to be robbed, unable to reach home, and forced to sleep on the streets. Several fathers also reported frequently getting into fights when drunk. Such behaviours led to community members and neighbors avoiding contact with the father or his family.

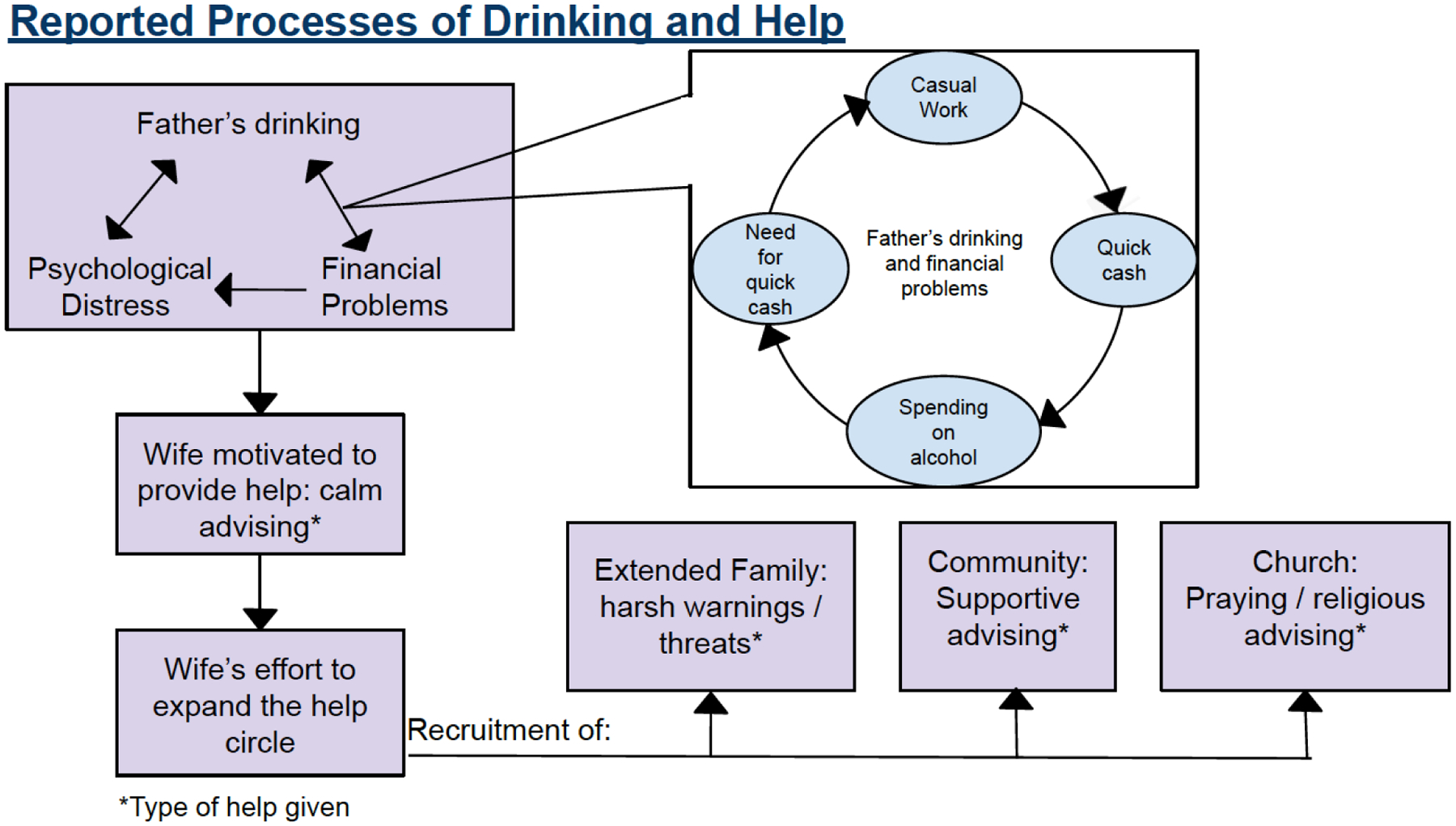

Figure 1: Reported Processes of Help Among Problem-drinking Fathers in Kenya.

Fathers’ drinking is influenced by a cycle of casual work (manual labor), quick earning, and immediate spending, which causes financial problems for the family. Often the financial problems also impact the father’s distress level, leading him to consume alcohol. This motivates the most affected members of the family (most often the wife) to help the father by providing calm advice. To expand the circle of help, wives reported recruiting members of the extended family, community, and church. Each group presented a unique approach to helping the father.

Family

Most families reported having financial, emotional, and functional difficulties due to the father’s drinking. Wives reported a lack of basic needs such as food and clothing as a result of her husband spending earnings on alcohol. They also reported having to find casual work, usually manual labor, to earn enough money to feed the children. One mother reported, “I was digging at a very tedious job because I knew that my children needed to eat and bathe. You just assume that you are a single mother. When he comes back home, he eats and worries about nothing as long as he is full. He goes, get drunk, then comes back home.” Related, several wives reported not trusting the father with money; one father was reported to steal money from the wife’s savings to drink alcohol. Children were often sent home from school due to lack of school fees. In some cases, the wives described talking to the school teachers and requesting extra time or asking for financial favours from extended family members. Even when children were able to attend school, they reported lack of school-related materials due to lack of money.

Wives further reported facing difficulty in communicating about the family’s needs with the father and described overall negative effects of drinking on family relationships. Fathers were reported to come home drunk and quarrel with the wife, with one wife reporting severe physical abuse if the father was angered when drunk. Children reported having very limited contact with the father, but when the father was at home, they feared him when he was drunk. Fear of the father often lead to the child being unable to communicate his/her needs to the father, and a few children reported being beaten when they tried. One child reported, “[The reason I can’t talk to my father] is because whenever I tell him something, he says that I am speaking lies…Like I can tell him that my school exercise book is filled up, and he would in return tell me that I must have torn it up; then he beats me” (Child, Female, 17). A few wives and children also reported facing stigma from peers and community members due to the father’s alcohol use. Wives reported feeling ashamed walking with the father in the community, and one child reported being laughed at in school because his father is a “drunkard.” Some wives reported people not visiting their home and neighborhood children not being allowed to go to their home due to how the community perceived their household. One wife reported that their home was known as the “alcohol house.”

Types of Help

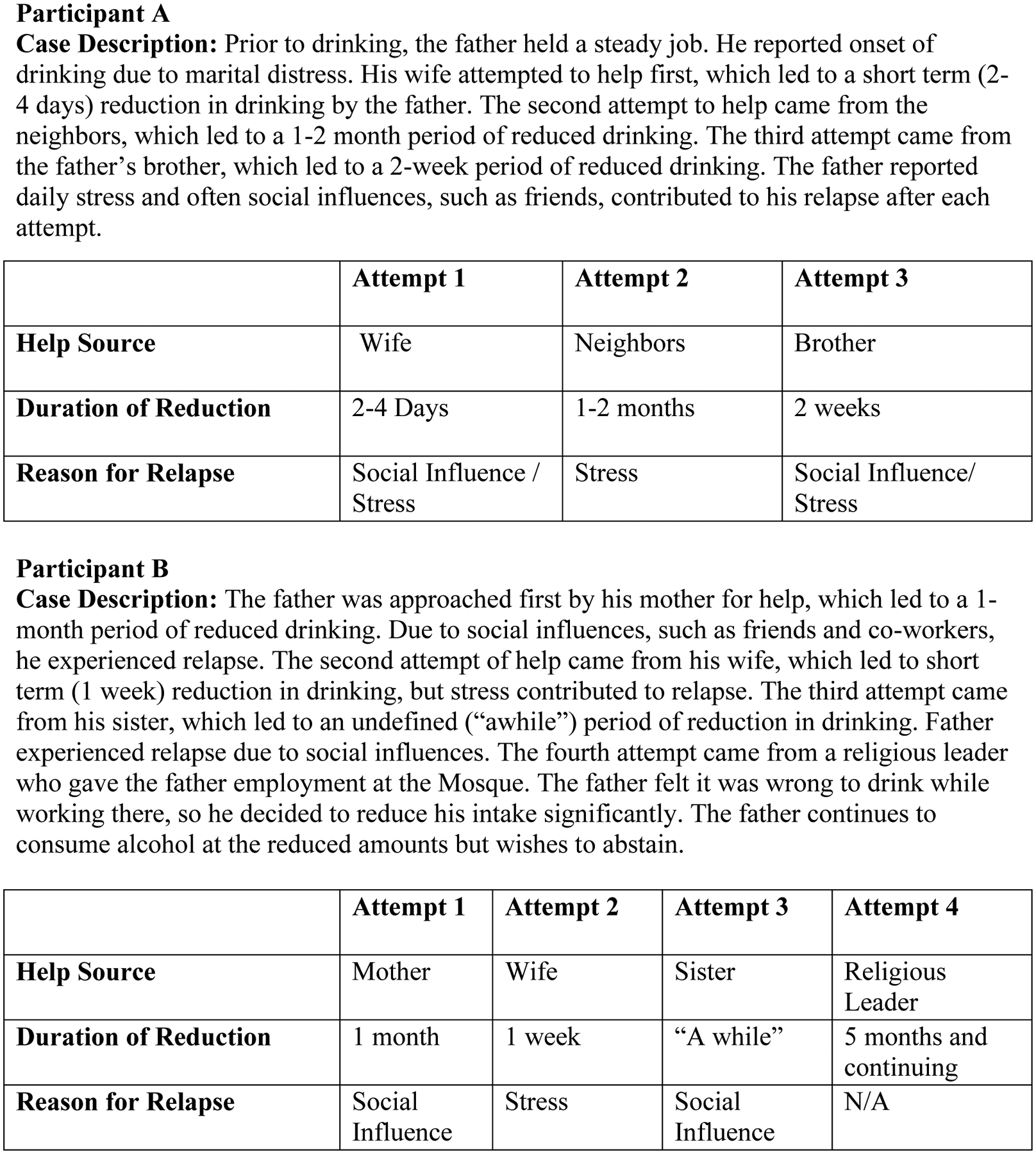

When asked about experiences with treatment, all participants reported various types of informal help received by the father, and none reported awareness of formal treatment services in the area. The help received by the fathers included help from family (nuclear and extended), community members or neighbors, church members, and friends. Participants most frequently reported the wife as primary help-giver; followed by the father’s parents, siblings, community/neighbors, friends, church, children, and in-laws (Table 1). A few fathers also reported having successfully reduced or quit alcohol for a period of time through helping themselves. Two of these fathers are described in case studies in figure 2 to highlight some of the typical ways various types of help are received over time, how those sometimes interact with periods of reduction in drinking, and reasons for relapse. They reported reducing contact with friends who drink, keeping themselves busy, and praying as beneficial methods. Related, three fathers reported believing that quitting or reducing alcohol use can only be done when the person decides on their own and not by the help of others. There were no reports of fathers engaging in any active help-seeking behaviours. Rather, the help-givers approached the father, visiting him at his home.

Table 1:

Sources of Help for Problem-drinking Fathers, as Reported by Fathers and Wives

| Source of Help | Frequency: N (%) |

|---|---|

| Wife | 15 (68%) |

| Father’s Parents | 10 (45%) |

| Father’s Siblings | 9 (41%) |

| Community Members | 8 (36%) |

| Church | 8 (36%) |

| Friends | 8 (36%) |

| Children | 3 (14%) |

| In-laws | 2 (9%) |

Figure 2. Case Studies: Timelines of help and drinking reduction.

Most often, the wife was the first line of help. They usually began by advising the fathers to quit drinking so they can provide for their family and accomplish family goals, such as saving money to buy cattle or completing house repairs. Most wives did not use a harsh tone when giving help to the father; rather, they described calm or pleading tones with the aim of gently convincing. One father reported, “Sometimes I come home when I am drunk, and [my wife] doesn’t want to chase me away, she welcomes me home and tells me that ‘Baba so and so,’ ‘do this so that your life may change.’ She has been wishing me well, while I have been drinking.” The term ‘baba’ (“father”) is used in an endearing manner to appeal to the father to reduce or quit alcohol. There were two exceptions to this calm manner, in which wives threatened to take the children and return to her parents’ home. A few wives reported waiting for the father to sober up before giving help so they could ensure that the father is understanding their advice and the conversation doesn’t turn into a quarrel.

Most wives reported reaching out to extended family and community members to offer help to the father in addition to their own efforts to talk with him (Figure 2). Among extended family, fathers and wives described the father’s parents and siblings as most helpful. One wife reported, “I said to him that it was high time he stopped abusing alcohol; otherwise, his home will get destroyed. He listened and calmed down, but after like a span of one to two weeks, he went back to it again…So I went to his mother and reported him, and the mother talked to him.” The extended family was reported to use a harsher tone in their help than the wife. Often, they threatened to relocate the wife and children away from the father or attempted to scare the father by telling him that he would “leave his family behind,” meaning his alcohol consumption could prove to be fatal. In some cases, the extended family asked the father to just reduce his consumption if he didn’t want to quit completely.

Community members also gave advice to the father on quitting alcohol. Help from community members and neighbors consisted of asking the father to stop drinking excessively so that he can return home instead of sleeping in the streets, avoid physical altercations, and maintain peace within the household and the community. Church members often visited the father upon the wife’s request and/or when the father stopped attending church. Most often, church members advised the father to go back to church and change his lifestyle, and they attempted to help by praying for and visiting him.

In the situations described above, participants reported that fathers received vague statements of guidance or warning, rather than specific advice regarding how to change their behaviour. There were a few notable exceptions, however. In two cases, behavioural advice was given from individuals who had successfully quit drinking alcohol. One father reported, “[The neighbor’s] words came to me clearly. He told me that he took alcohol for 25 years, but he later had to quit. He told me that there is no place alcohol takes people… He told me that you can’t stop once, you just proceed gradually until you stop.” Another father reported being advised by his father-in-law who had successfully abstained from alcohol for many years. The father-in-law advised him to “start by leaving his friends and that alcohol would not come following him.” Wives seemed to have ideas about specific behavioural changes that may be helpful, such as the father getting a job or finding new activities that could occupy his attention; however, they did not explicitly report talking to the father about these ideas.

Barriers to Help-Acceptance

Negative Perceptions of Help

Some fathers reported feeling anger or apathy towards individuals attempting to help. Often this was related to the tone being used, such as harsher tones used by extended family members leaving the father feeling ashamed, guilty, or overwhelmed; this led him to resist the help. One father described, “I was happy that he came [to the hospital], but when he began talking to me about alcohol, I became angry at him. I just showed interest to please him, but I had not taken any keen interest in the actual sense…I felt like he was looking down upon me, and I was not happy about it.” Wives reported similar observations.

Most fathers reported that someone had advised them to go to church to be helped; only two fathers reported actually attending and only during the period of time that they had reduced or quit alcohol. Most fathers reported agreeing to attend church but leaving home or becoming unavailable at the last minute. Even though most fathers were not attending church, they did not object to family members continuing to attend or children going to Sunday school. Only one wife reported that during the time the father was drinking, he did not allow her to go to church or even the church members to visit their home. Two fathers explicitly reported not wanting to go to church due to discomfort, mistrust, or lack of time. One father reported, “The issue of asking me to go to church, that was so much of a bother to me. They were wasting my time…even just going to sit in church, that is wasting time…. it was just out of my comfort zone.”

Negative Social Influence

Almost all fathers, wives, and children reported social influences such as friends to be a barrier to help-acceptance. Most fathers reported their attempts to quit alcohol were undermined by friends offering to buy alcohol for them, asking to accompany them to the alcohol den, or tricking them into drinking. One father reported, “Even when they come and find you working in your garden, they keep enticing you to follow them to the center [of town] to go and drink. They are never tired; they keep nagging you even when you have refused. They sweet talk and say to me that they have 20 shillings (~20 cents) for buying a cup of tea for me.” A few fathers reported having informed friends of their intention to reduce or quit drinking, but the friends either responded by not believing him, saying that he will be back to drinking soon, or by asking him just to accompany them to the alcohol den for tea. One father reported that his friends, unbeknownst to him, mixed alcohol in his tea, which led him to drink more since his resolution had already been broken.

Occupation

Most fathers in the study were casual workers, who perform manual labor and get paid daily. Most fathers reported the need to drink alcohol after a day of casual work to “rejuvenate the body” or deal with family-related stress. One father reported, “So, you might find yourself going for one glass and say, ‘Just a warm-up to deal with any burn outs… to rejuvenate and relax the body from hard work.’ It is sometimes necessary. But you will find that one may end up overdoing it.” A cyclical consumption pattern appeared, which indicated that the nature of casual work and being paid daily often led fathers to drink alcohol regularly, usually with coworkers and friends (Figure 2). Fathers and wives reported that fathers almost always spent all of their earnings on alcohol. Fathers then sought more casual work to get quick cash to provide for the basic needs of the family. However, once the money was procured, the father was tempted to consume alcohol before returning home with the money; this led to continual strain on the family.

Facilitators to Help-Acceptance

Positive Perceptions of Help

Almost all fathers reported perceiving help as a way to attain peace and improve conditions for their families. Fathers were most willing to accept help when offered by wives or extended family members, but, as mentioned earlier, the tone of help was an important factor. Help given using a calmer approach was perceived to be positive and therefore accepted. For example, a wife may choose not to quarrel with the father when he returns home drunk but rather wait to talk until the next morning; this was perceived as a sign of caring. Similarly, upon being asked how he felt about receiving help from his mother, one father reported, “I felt like my parent still loves me, and I was happy. I realized that even if you can be a drunkard, your parent is still a friend and is close to you. I saw it wise that if my parent could still love me like this, I should change.” Additionally, even though most fathers reported not attending church/mosque during the time they were consuming alcohol, many fathers reported turning to God or prayer for help. Fathers, including the ones uncomfortable about going to church, perceived praying, and being prayed for, as positive sources of help and were willing to pray with family members.

Financial Motivation to Stop Drinking

Most fathers reported financial strain as a motivation to reduce or quit alcohol. Two of the eleven fathers reported previously owning businesses, which allowed them to provide for basic needs of the family and accumulate savings for emergencies. However, since they started drinking alcohol, their businesses failed, and they have found themselves unable to provide.

Most fathers recognized that lack of money caused strain on the family and reported that witnessing these strains motivated them to accept help so that they could be better providers. Wives were reported to play a vital role in opening the father’s eyes to the financial situation of the household. Not having basic needs and not being able to accomplish family goals, such as building a new home or saving, were reported as main motivators for wives to initiate help.

Perceived Social Support

Some fathers reported receiving emotional and financial support from family and community members. During their attempts to reduce or quit drinking, some also reported receiving encouragement from community and church members; often fathers received compliments or encouragements, such as “you are now looking well” or “you are doing a good thing.” In some cases, wives and extended family members were reported to broaden the support circles around the father. One mother reported, “I usually even consult some of my women friends. When they find him sober, they usually congratulate him and say to him, ‘It is good you continue thus.’”

Most fathers reported their wives and/or extended family members having faith in their ability to quit drinking. Several fathers also described that others helped with paying children’s school fees, buying materials for a new house, or covering medical fees. The fathers perceived this as an act of trust that they will reduce or quit drinking. In contrast to the above, some fathers also reported being motivated by negative social responses, such as family or community members not believing the father is capable of reducing or quitting alcohol. Fathers reported that this lack of faith led to their becoming determined to change.

External Stigma

Fathers reported being excluded from family and community gatherings, as well as from family decisions. This led the fathers to feel rejected and often disrespected, but the negative feelings also motivated the fathers to reduce or quit drinking in order to be a better head of the household. A few fathers reported experiencing stigma from family and community members that acted as a facilitator. One father reported, “I sympathized for my family; I said that if people could talk about me like this, then what about my family? So, I said that is better I fight for my family.”

Discussion

This qualitative study explored barriers and facilitators to help-acceptance from the perspectives of problem-drinking men, their spouses, and their children, which provides a unique contribution to the scarce literature on the treatment gap for substance use in Kenya and other low-resource settings. We found informal help to be most commonly reported, alongside a remarkable lack of awareness of available formal services; none of the study participants reported knowing about the available rehabilitation or mental health services in the area. This is consistent with findings of a population-based survey in Kenya, that 82% of respondents reported little to no awareness of available formal services (NACADA 2012). Currently, there are three rehabilitation facilities in a 30-kilometer radius of Eldoret town, each offering a three-month inpatient program with costs ranging from 50,000 Ksh (~ 500 USD) to 90,000 Ksh (~900 USD). These high costs confirm concerns raised in the literature regarding rehabilitation and mental health services being pragmatically inaccessible in LMICs (Patel et. al., 2007; Singla et al., 2017).

Three overarching themes regarding barriers and facilitators to help-acceptance included the strong influences of poverty, people surrounding these fathers in families and communities, and practices related to culture.

Poverty

Poverty is a risk factor for problem drinking or alcohol dependence (Karriker-Jaffe, 2011), and alcohol abuse perpetuates poverty by causing consistent financial burden, especially in LMICs (Matto, Nebhinani, Kumar, Basu, & Kulhara, 2013; Schafer & Koyiet, 2018; Tudawe, 2001). Results from our study mirrored these findings, as fathers reported casual work (manual labor) as their main source of income and often found the daily income, combined with peer influence, to lead to heavy alcohol use. The spending on alcohol left little to nothing for basic household needs, perpetuating a cycle of financial deficit leading to the family suffering chronic economic burdens. At the same time, fathers named the desire to support their family financially as a motivator to attempt quitting.

People

In describing types of informal help, the important role of family and community was apparent across all interviews. This is consistent with other literature in sub-Saharan Africa, where family is the nexus of social life (Ekane, 2013) and extends beyond the nuclear family to include siblings, grandparents, cousins, and even members of the community such as neighbors (Wilson & Ngige, 2006). The prominence of family and community members in response to drinking appears to differ from high-resource settings that have more accessible evidence-based treatments in formal settings. That said, families and others are sometimes active in help-seeking and treatment in these settings as well. One example is Alcohol Focused Behavioural Couples Therapy (ABCT), an intervention that involves partners and family members in treatment, providing skills to better support the drinker’s efforts to change (Epstein & McCrady, 2002). Such interventions could be useful in settings like Kenya, where families are clearly already involved.

The role of positive social support as a facilitator to help-acceptance is consistent with other settings (Kelly et. al., 2010). Our results also suggested that lack of social support, such as fathers learning that their families had “lost faith” in their ability to stop drinking, also served as a facilitator, motivating men to accept treatment in order to become a better husband, father, and provider. Likewise, experiences of external stigma, such as being excluded from family and community meetings or being avoided by others, emerged as a motivator for fathers to change in order to become “role models.” While these experiences could certainly have negative effects on fathers’ emotional well-being, the fathers in this study found them motivating.

Negative influence of peers who drink alcohol was observed as one of the greatest barriers to accepting help; oftentimes, friends were reported as the primary reason for relapse. A review of social networks and alcohol use disorders in HICs showed peer influence to be a risk factor for poor treatment outcomes and high relapse rates (McCrady, 2004). A longitudinal study in the US also provides evidence that changing social networks, such as decreasing friendships with regular drinkers, can lead to lower levels of drinking (Mohr, Averna, Kenny, and Del Boca 2001). In this study, none of the fathers described efforts to change social networks during periods of abstinence or reduced drinking, but this could be a potential avenue for intervention.

Though it did not feature in our data, it is worth noting that the influence of people extends beyond immediate family and community, to include society as a whole. Traditionally, alcohol consumption has been viewed as a means to strengthen relationships among families, friends, and communities in many parts of Kenya (Muturi, 2014). However, the recent surge in use of harmful home-brewed alcohol has raised concern across the country, including harmful effects like unemployment, school drop-out, and marital problems (Kaithuru & Stephen, 2015; Muturi, 2016; NACADA, 2010). It is possible that shifting norms and stigma around alcohol consumption will lead to changes in patterns of help-seeking.

Practices

Two primary ways that culturally-grounded practices and norms influenced fathers’ experiences of help were religion and gender identity. Fathers were urged to attend church during periods of active drinking as a way to receive help, but most fathers reported not doing so, even though most of them had attended church before they began drinking. However, fathers reported acceptance of other religiously-oriented sources of help, including being prayed for by others or being encouraged to have faith in God. This points towards a complicated role of faith in these men’s lives as it relates to drinking; it cannot be categorized as a positive or negative influence. Religion plays an important role in Kenya: approximately 83% of the population self-identifies as Christian, and approximately 11% identifies as Muslim (CIA, 2009). More broadly, a systematic review of the relationship between alcohol and religion shows evidence of religion playing a protective role from alcohol abuse (Chitwood, Weiss, & Leukefeld, 2008). However, empirical research on the effectiveness of interventions for substance use that incorporate spiritual or religious content is sparse (Neff & MacMaster, 2005). One method that does integrate spirituality explicitly is Alcoholics Anonymous, but there is inconclusive evidence on the effectiveness of such twelve-step facilitation methods in LMICs (Kaskutas, 2009).

The strongly gendered expectations of fathers to be providers and leaders, or “heads” of households (Kato-Wallace, Barker, Eads, & Levtov, 2014; Schafer & Koiyet, 2018), may have led a father to perceive dire conditions of the family, such as lack of money for food, as a dereliction of his duties as a man. A mixed-methods study in Kenya that explored perceptions of masculinity showed men increasingly clinging to the roles of protector and provider when faced with the threat of losing this part of their identity (Corria, Amuyunzu-Nyamongo & Francis, 2006). This is reminiscent of fathers in this study who became motivated to accept help after having the realization that they were no longer recognized as the provider or head of the household. On the other hand, a cross-cultural study in 8 different countries, including South Africa and Zambia, found that heavy alcohol use was associated with both masculinity and freedom, carrying a positive connotation (WHO, 2005b). The fathers in the present study did not endorse positive notions of freedom or masculinity associated with drinking, but there may be a subtle interplay between these two conflicting perspectives that should be explored in future work.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that should be considered. First, the sample represents only men who have not yet received effective help for problem drinking. That is, it does not include men who may have successfully stopped drinking after receiving either informal or formal help. The fathers in the sample agreed to participate in a pilot intervention and therefore displayed a certain level of motivation to receive/seek help, which might not be representative of all problem drinking fathers (for example, fathers who perceive that they don’t need help). The sample also excluded men with severe AUD who may have unique perspectives on the issues explored here. Therefore, as with all qualitative inquiries, the findings are bound to the participants and context in which the study was conducted.

Conclusion

In the Kenyan context, three overarching themes accounted for barriers and facilitators to father’s help-acceptance for alcohol use: the strong influences of poverty, people surrounding these fathers in families and communities, and cultural practices. As this study focuses on individuals who continue to engage in problem drinking, studies identifying strengths in the existing social networks (i.e. nuclear and extended family and community members) will inform future community-based interventions and aid in closing the persisting treatment gap in the region. The findings of the present study did not inform any aspect of the pilot intervention as the analysis phase for both projects took place simultaneously. However, Future interventions may benefit from incorporating awareness, such as providing detailed information on available treatment venues, within the psychoeducation components. Further, treatment research in this area should consider how to promote access and sustainability, with special attention to financial accessibility of treatment as critical to the field. mhGAP approaches such as task-shifting may prove to be promising solutions for issues related to accessibility and sustainability.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University Graduate School, Duke University Bass Connections, and the National Institutes of Health [F32MH113288]. We are grateful to our research assistants and all those who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration: The authors report no conflicts of interest

References

- Benegal V, Chand PK, & Obot IS (2009). Packages of Care for Alcohol Use Disorders in Low- And Middle-Income Countries. PLOS Medicine, 6(10), e1000170 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changalwa CN, Ndurumo MM, Barasa PL, & Poipoi WM (2012). The relationship between parenting styles and alcohol abuse among college students in Kenya. Greener Journal of Educational Research, 2(2), 013–020. [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood DD, Weiss ML, & Leukefeld CG (2008). A Systematic Review of Recent Literature on Religiosity and Substance Use. Journal of Drug Issues, 38(3), 653–688. 10.1177/002204260803800302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, & McCrady BS (2002). Couple therapy in the treatment of alcohol problems.

- Herbert S, Stephens C, & Forster M (2018). Older Māori understandings of alcohol use in Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal of Drug Policy, 54, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen M, Holmila M, Notkola I-L, & Raitasalo K (2016). Mental disorders and harmful substance use in children of substance abusing parents: A longitudinal register-based study on a complete birth cohort born in 1991. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(6), 728–740. 10.1111/dar.12417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan L, Sadowski LS, Kumar S, Hassan F, Ramiro L, & Vizcarra B (2004). World studies of abuse in the family environment - risk factors for physical intimate partner violence. Injury Control & Safety Promotion, 11(2), 117–124. 10.1080/15660970412331292342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaithuru P, & Stephen A (2015). Alcoholism and its Impact on Work Force: A Case of Kenya Meteorological Station, Nairobi. J Alcohol Drug Depend, 3(192), 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ (2011). Areas of disadvantage: A systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug & Alcohol Review, 30(1), 84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato-Wallace J, Barker G, Eads M, & Levtov R (2014). Global pathways to men’s caregiving: Mixed methods findings from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey and the Men Who Care study. Global Public Health, 9(6), 706–722. 10.1080/17441692.2014.921829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PS, El-Sheikh M, Keiley M, & Liao P-J (2009). Longitudinal relations between marital aggression and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(1), 2–13. 10.1037/a0013459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP, Peterson JA, Wilson DME, & Brown BS (2010). The relationship of social support to treatment entry and engagement: The Community Assessment Inventory. Substance Abuse, 31(1), 43 10.1080/08897070903442640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Link B, Olfson M, Grant BF, & Hasin D (2010). Stigma and Treatment for Alcohol Disorders in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(12), 1364–1372. 10.1093/aje/kwq304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laonigro I, Correale M, Di Biase M, & Altomare E (2009). Alcohol abuse and heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 11(5), 453–462. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ (2013). Paternal and Household Characteristics Associated With Child Neglect and Child Protective Services Involvement. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(2), 171–187. 10.1080/01488376.2012.744618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS (2004). To have but one true friend: implications for practice of research on alcohol use disorders and social network. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 18(2), 113–121. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Towe SL, Watt MH, Lion RR, Myers B, Skinner D, … Pieterse D (2015). Addiction and treatment experiences among active methamphetamine users recruited from a township community in Cape Town, South Africa: A mixed-methods study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 152, 79–86. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinck F, Cluver LD, Boyes ME, & Mhlongo EL (2015). Risk and Protective Factors for Physical and Sexual Abuse of Children and Adolescents in Africa: A Review and Implications for Practice. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(1), 81–107. 10.1177/1524838014523336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings: Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP): Version 2.0. (2016). Geneva: World Health Organization; Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390828/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkuu RS, Barry AE, Swahn MH, & Nafukho F (2019). Unrecorded alcohol in East Africa: A case study of Kenya. International Journal of Drug Policy, 63, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Averna S, Kenny DA, & Del Boca FK (2001). “Getting by (or getting high) with a little help from my friends”: an examination of adult alcoholics’ friendships. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(5), 637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugisha F, Arinaitwe-Mugisha J, & Hagembe BON (2003). Alcohol, substance and drug use among urban slum adolescents in Nairobi, Kenya. Cities, 20(4), 231–240. 10.1016/S0264-2751(03)00034-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muturi N (2014b). Engaging communities in the understanding of excessive alcohol consumption in rural central Kenya. Journal of International Communication, 20(2), 98–117. doi: 10.1080=13216597.2013.869240 [Google Scholar]

- Muturi N (2016). Community perspectives on communication strategies for alcohol abuse prevention in rural central Kenya. Journal of health communication, 21(3), 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers BJ, Louw J, & Pasche SC (2010). Inequitable access to substance abuse treatment services in Cape Town, South Africa. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 5, 28 10.1186/1747-597X-5-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NACADA | Surveys & Results. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2018, from http://nacada.go.ke/?page_id=387

- Nadkarni A, Weobong B, Weiss HA, McCambridge J, Bhat B, Katti B, … Patel V (2017). Counselling for Alcohol Problems (CAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for harmful drinking in men, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 10065(389), 186–195. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31590-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA, & MacMaster SA (2005). Applying Behavior Change Models to Understand Spiritual Mechanisms Underlying Change in Substance Abuse Treatment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31(4), 669–684. 10.1081/ADA-200068459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neger EN, & Prinz RJ (2015). Interventions to address parenting and parental substance abuse: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Clinical Psychology Review, 39, 71–82. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obot IS, Wagner FA, & Anthony JC (2001). Early onset and recent drug use among children of parents with alcohol problems: data from a national epidemiologic survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 65(1), 1–8. 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00239-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, … van Ommeren M (2007). Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London, England), 370(9591), 991–1005. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, & Thornicroft G (2009). Packages of Care for Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: PLoS Medicine Series. PLOS Medicine, 6(10), e1000160 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GLG, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, … Taylor B (2010). The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction, 105(5), 817–843. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salwan J, & Katz CL (2014). A Review of Substance Use Disorder Treatment in Developing World Communities. Annals of Global Health, 80(2), 115–121. 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders SM, Zygowicz KM, & D’Angelo BR (2006). Person-related and treatment-related barriers to alcohol treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(3), 261–270. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer A, & Koyiet P (2018). Exploring links between common mental health problems, alcohol/substance use and perpetration of intimate partner violence: A rapid ethnographic assessment with men in urban Kenya. Global Mental Health, 5 10.1017/gmh.2017.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahler G, Kirby K, & Kerwin M (2007). A faith-based intervention for cocaine-dependent Black women. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 39(2), 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, & Silove D (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476–493. 10.1093/ije/dyu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, & Rippens PD (2004). A factor analytic study of influences on patterns of help-seeking among treated and untreated alcohol dependent persons. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(3), 237–242. 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00209-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudawe I (2001). Chronic Poverty and Development Policy in Sri Lanka: Overview Study (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1754524). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1754524 [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz ND, Wilsnack SC, & Harris TR (2000). Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: cross-cultural patterns. Addiction, 95(2), 251–265. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2005a). Alcohol, gender and drinking problems in low and middle income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2005b). Alcohol Use and Sexual Risk Behaviour: A Cross-cultural Study in Eight Countries. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]