Abstract

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES:

This retrospective study compared surgical outcome of pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft fixed with sutures, tissue glue or autologous blood in relation to recurrence rate and surgical complications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Surgical records of 148 patients operated for excision of primary nasal pterygium with conjunctival autograft were reviewed retrospectively for the period between January 2015 and June 2018. Based on surgical technique used to fix the graft, patients were divided into three groups. In Group A, 8 “0” vicryl suture was used to fix the graft in 90 patients. In Group B, fibrin glue was used to fix the graft in 23 patients. In Group C, autologous blood was used to fix the graft in 35 patients. Patients who were operated by single surgeon and had followed up for minimum six months were included in the study.

RESULTS:

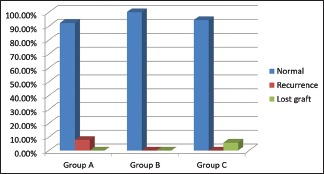

Group A had recurrence in 7 cases (7.78%) whereas; Group B and C had no recurrence. But, in Group C two patients (5.71%) lost their graft. Overall recurrence rate in the study was 4.72%.

CONCLUSION:

Among the three techniques used in the study, recurrence was seen in the suture group and autologous blood group had loss of graft. The fibrin glue group was free of complications.

Keywords: Autologous blood, conjunctival autograft, fibrin glue, recurrence rate, vicryl suture

Introduction

Pterygium is a wing-shaped encroachment of conjunctival fold onto the cornea with elastotic degeneration of a subconjunctival tissue. It is frequently seen in dry, hot, dusty, and windy environment. Exposure to ultraviolet rays and the loss of limbal corneal stem cells are prime factors incriminated in etiopathogenesis. Search for the best surgical approach to treat pterygium is still continuing.[1] Excision of pterygium with conjunctival autograft (CAG) seems so far to be one of the safest and most promising methods.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] In this study, the techniques of CAG affixed with sutures, fibrin glue, and autologous blood were compared with regard to the recurrence rate and complications of surgery.

Methods

This was a retrospective study. Surgical records of 148 patients operated for the excision of primary nasal pterygium with CAG by single surgeon (MS) were reviewed retrospectively for the period between January 2015 and June 2018. A free CAG was used to cover the bare sclera after pterygium excision. Based on the technique used to fix the graft, they were divided into three groups. In Group A, 8 “0” vicryl suture was used to fix the graft in 90 patients. Due to longer surgical time and discomfort in the postoperative period, sutures were substituted with fibrin glue. Hence, Group B comprised 23 patients where fibrin glue was used to fix the graft. However, due to the cost and nonavailability of fibrin glue, autologous blood was used in the place of fibrin glue. Therefore, Group C formed of 35 patients where autologous blood was used to fix the graft. Patients operated for temporal, recurrent, double-head, or pseudo pterygium were excluded from this study. All patients were operated in a tertiary care center catering to armed forces service personnel and their dependents, and only those patients who had follow up for 6 months and above were included in the study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the hospital.

Surgical technique

All cases after obtaining informed written consent were operated under local anesthesia. Lidocaine (Xylocaine, AstraZeneca) 2% was injected into the conjunctiva forming the body of pterygium and at a site from where the graft was harvested. Pterygium head was avulsed using a toothed forceps and was separated from the cornea. Abnormal scar tissue on the corneal surface and wound bed was scraped by Crescent Knife. The body of the pterygium was dissected and excised. An oversize thin CAG by 1 mm in length and breadth relative to bare sclera was harvested from the superior temporal region. Care was taken not to include Tenon's capsule in the graft. With epithelial side facing upward and limbal edge of the graft aligned to the nasal limbus, the graft was secured in place. No corneal limbal cells were included while harvesting the graft. Cautery was not used.

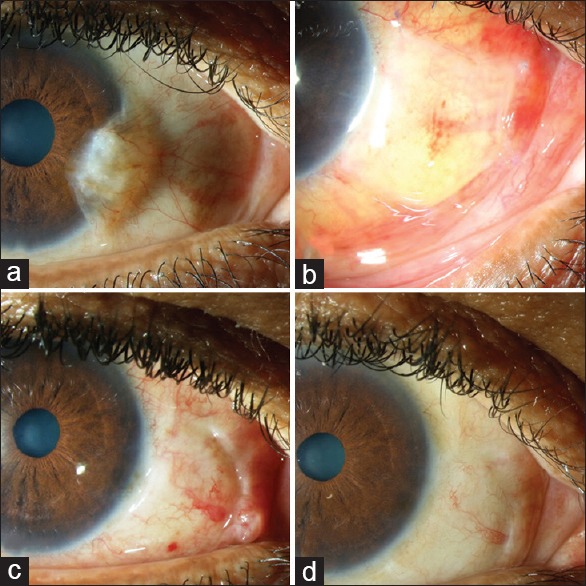

In Group A, 4–5 interrupted 8 “0” vicryl sutures were used to fix the graft to the conjunctiva at the recipient site [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Conjunctival autograft secured with suture. (a) Preoperative photo (b) postoperative photo at 1 week (c) postoperative photo at 1 month and (d) postoperative photo at 15 months

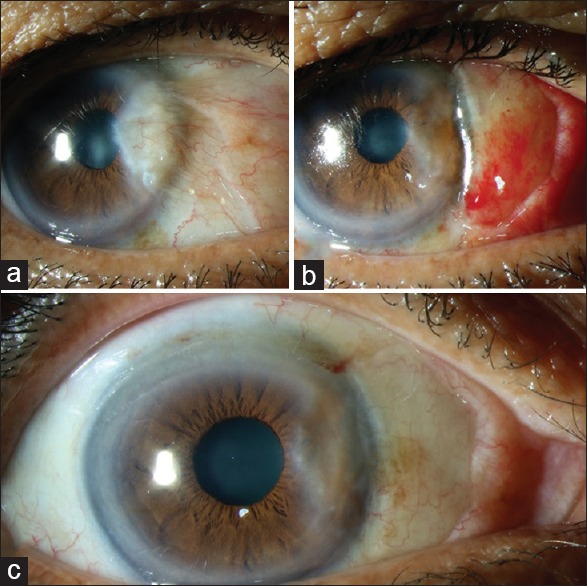

In Group B, fibrin glue which is a fibrin sealant that imitates the final stage of coagulation cascade was used to fix the graft. ReliSeal kit from Reliance Life Sciences, India, was reconstituted in the following manner. In Step 1, aprotinin was injected into the vial containing fibrinogen. It was stored at 37°C temperature for 10 min. In Step 2, water for injection was injected into thrombin component. In Step 3, both these constituents were aspirated in two separate 2 cc syringes using 21-G needles, avoiding double injector system provided by the manufacturer. These constituted two separate solutions of fibrin glue, one was applied on the undersurface of the graft and other on the bare sclera separately, taking care not to mix them with each other before pasting the graft. The graft was pasted to conjunctival edges and bare sclera at the recipient site in such a way that epithelial side faced up and the limbal edge of the graft attached to the nasal limbus [Figure 2]. This sandwich technique gave us extra time to adjust the graft appropriately before the two solutions could come in contact with each other and seal the wound.

Figure 2.

Conjunctival autograft secured with fibrin glue. (a) Preoperative photo (b) postoperative photo at 1 week and (c) postoperative photo at 9 months

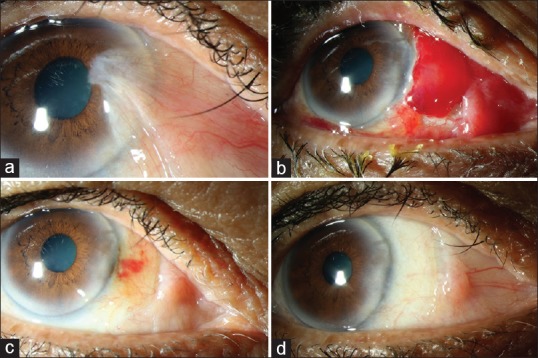

In Group C, after harvesting free CAG, a small conjunctival blood vessel was nicked with 26-G needle, blood was allowed to ooze over the bare sclera, and the graft was placed over it [Figure 3]. The graft edges were tugged under the pocket of the conjunctiva at the site of the excised pterygium on all the sides except the edge at the nasal limbus. The graft was ironed out by applying gentle pressure with iris repositor so that the graft sticks to the bare sclera. The blood clotting time is usually 4–10 min, and therefore, the graft was not disturbed for further 10 min. The adhesion of the graft to the bare sclera was confirmed by gently stroking with Weck-Cel sponge tip centrally and on the edges.

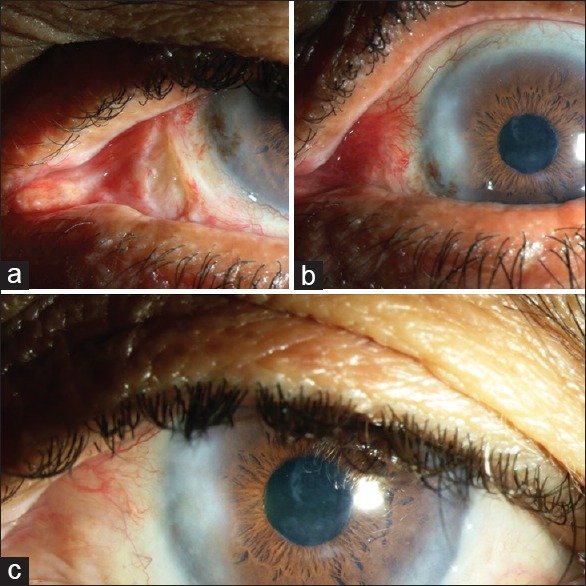

Figure 3.

Conjunctival autograft secured with autologous blood. (a) Preoperative photo (b) postoperative photo at 1 week shows graft retraction (c) postoperative photo at 1 month and (d) postoperative photo at 18 months

All the patients were given firm eye patch which was removed by the surgeon the next day. All patients postoperatively were reviewed on 1st, 7th 30th, and 180th days. In the postoperative period, the steroid-antibiotic combination was given in tapering dose for a period of 4 weeks. In Group A, suture removal was done only for those patients who had loose or broken sutures. The recurrence was defined as conjunctival fibrovascular encroachment of more than 1 mm onto the cornea.

The three techniques were compared with regard to the recurrence rate and complications of surgery.

Results

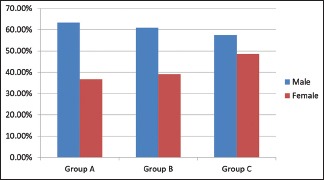

As shown in Graph 1, of 90 patients from Group A, 57 (63.33%) were male and 33 (36.66%) were female. The age of the patients ranged between 19 and 87 years (average 47.9 years). Of 23 patients from Group B, 14 (60.87%) were male and 9 (39.13%) were female. The age of the patients ranged between 23 and 66 years (average 44.3 years). Of 35 patients from Group C, 18 were male (51.43%) and 17 were female (48.57%). The age of the patients ranged between 26 and 81 years (average: 44.37 years). All the patients in the 1st week complained discomfort, watering, redness, and photophobia and had lid edema, conjunctival hemorrhage, and chemosis of varying degree. Signs and symptoms were more pronounced in Group A compared to Groups B and C and were attributed to irritation caused by vicryl sutures. All the patients were comfortable at the end of 1 month.

Graph 1.

Gender distribution

Seven patients (7.78%) from Group A had a recurrence, and their mean age was 45.42 (range 34–59) years, and 2 (5.71%) patients from Group C had lost their graft [Graph 2]. In both patients, regrafting was done immediately by harvesting fresh graft from the inferior bulbar conjunctiva. 8 “0” vicryl suture was used to secure the fresh graft. Their postoperative recovery was uneventful. None of the patients from Group C had recurrence.

Graph 2.

Incidence of complications

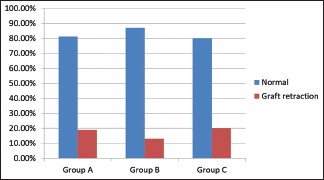

Patients from all the three groups encountered gaping at graft–host junction [Graph 3]. In Group A, due to broken sutures, 17 patients (18.89%), and in Groups B and C, due to graft retraction, 3 (13.04%) and 7 (20.0%) patients, respectively, had wound dehiscence. Complete healing and reepithelialization of the wound was noted in all patients by 4 weeks [Figure 4].

Graph 3.

Incidence of graft retraction

Figure 4.

Conjunctival graft secured with autologous blood, showing postoperative retraction healed without sequelae (a) At 1 week (b) at 4 weeks and (c) at 21 months

Patients were free from other major complications such as granuloma formation, scleral necrosis, and suture-related infections.

Discussion

The standard treatment for pterygium is excision with CAG. However, the surgical outcome is compromised by recurrence and surgical complications. Variables such as geographic location, patient's race, age, exposure to sun, and other environmental factors have influence on the incidence of pterygium and its recurrence after surgery. The skill and expertise of the surgeon has additional impact on the outcome of surgical result. In our study, all the surgeries were performed by single surgeon.

The use of CAG following the pterygium excision was first described by Kenyon et al. in 1985.[2] CAG initiated by them significantly affected the recurrence rate, which dropped from 89% in case of bare sclera technique to 2%[3] and has since been considered as the best method of treatment. Despite being safe and effective procedure, suturing CAG required surgical expertise, technical abilities, more surgical time, and need of their removal at times. Patients always complain of pain, grittiness, and watering postoperatively, especially if vicryl suture were used. Sutures are thought to be not actively participating in wound healing; it can result in additional trauma to surgical site, acts as a nidus for infection, and carries the risk of suture-related complications such as granuloma formation. Silk, nylon, and particularly, vicryl sutures placed in the conjunctiva are thought to cause inflammation and migration of the Langerhans cells to the cornea, thus favoring recurrence.[4] In our study, the overall rate of recurrence was 4.72%. Group wise, Group A had 7.78% recurrence, but Groups B and C had none. Cohen RA et al.[5] were first to use fibrin glue in pterygium surgery. They however used it with sutures. Koranyi et al.,[6] who used fibrin glue singly, observed that the immediate adhesion of the whole graft to the underlying sclera may inhibit the fibroblasts of the nasal Tenon's tissue from proliferating toward the cornea, keeping recurrence rate low. Thereafter, many studies demonstrated lower rates of recurrence when fibrin glue was used compared to sutures.[7,8,9] Pan et al.[10] in their meta-analysis supported the superiority of fibrin glue over sutures in securing CAG, as it reduced the recurrence rate and decreased the operating time without increasing the risk of complications. Similar finding was noted in our study as well. The variation in the technique in applying fibrin gave us more time to position the CAG before fibrin glue sealed the wound.[11] The simple modification thus gave more stability to the graft.

Although generally considered safe, fibrin glues are currently manufactured from human plasma and therefore carry a theoretical risk of prion disease transmission and anaphylaxis in susceptible individuals. Furthermore, it is mandatory to maintain cold chain from time of preparation until it is used. Failure in maintaining cold chain drops the efficacy of fibrin glue. The cost and availability could be an issue. Autologous blood is considered an alternative to fibrin glue. de Wit[12] et al. in their small series of 15 eyes considered autologous blood safe and offered comparable results to current methods of suture or glue. Kurian et al.[13] stated that recurrence rate was 6.25% and 8.16%, but the graft displacement was 13% and 2.04%, respectively, with the use of autologous blood and fibrin glue in their series of 200 eyes. Nadarajah et al.[14] also stated that autologous blood does not exhibit similar graft stability seen with fibrin glue and had graft dislodged in 24.2% of patients. The recurrence rate after excluding cases of graft dislodgement was 3.4% in fibrin group and 10.6% in the autologous blood group. Boucher et al.[15] observed that CAG fixation with autologous blood was less stable and had higher recurrence rate compared with fixation with fibrin glue. Zeng et al.[16] in the meta-analysis found that autologous blood was inferior to fibrin glue with respect to surgical duration, graft retraction, and graft displacement nevertheless found no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of the recurrence rate. Kodavoor et al.[17] observed that recurrence rate, graft retraction, and graft loss were more with the use of autologous blood. In our study, although recurrence was nil in Group C, 2 patients (5.71%) had dislodgment of the graft. Prompt regrafting reduced the risk of further complications.

Conclusion

All the three techniques employed to secure CAG were effective in reducing the recurrence rate. Sutures however caused postoperative discomfort and recurrence was noteworthy. The use of fibrin glue was free of complications but involved high cost and availability was an issue. The use of autologous blood is suitable alternative to sutures and fibrin glue and patients had no recurrence, but the loss of graft was consequential.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cionni RJ, Watanabe TM. In: Pterygium Surgery. Buratto L, Phillips RL, Carito G, editors. Slack Incorporated: Thorofare; 2000. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenyon KR, Wagoner MD, Hettinger ME. Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1461–70. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salagar KM, Biradar KG. Conjunctival autograft in primary and recurrent pterygium: A study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2825–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/7383.3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki T, Sano Y, Kinoshita S. Conjunctival inflammation induces langerhans cell migration into the cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:550–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen RA, McDonald MB. Fixation of conjunctival autografts with an organic tissue adhesive. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1167–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090090017006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koranyi G, Seregard S, Kopp ED. Cut and paste: A no suture, small incision approach to pterygium surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:911–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.032854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdamar Y, Mutevelli S, Han U, Ileri D, Onal B, Ilhan O, et al. A comparative study of tissue glue and vicryl suture for closing limbal-conjunctival autografts and histologic evaluation after pterygium excision. Cornea. 2008;27:552–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318165b16d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahar I, Weinberger D, Dan G, Avisar R. Pterygium surgery: Fibrin glue versus Vicryl sutures for conjunctival closure. Cornea. 2006;25:1168–72. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000240087.32922.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang J, Yang Y, Zhang M, Fu X, Bao X, Yao K. Comparison of fibrin sealant and sutures for conjunctival autograft fixation in pterygium surgery: One-year follow-up. Ophthalmologica. 2008;222:105–11. doi: 10.1159/000112627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan HW, Zhong JX, Jing CX. Comparison of fibrin glue versus suture for conjunctival autografting in pterygium surgery: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1049–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fava MA, Choi CJ, El Mollayess G, Melki SA. Sandwich fibrin glue technique for attachment of conjunctival autograft during pterygium surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:516–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Wit D, Athanasiadis I, Sharma A, Moore J. Sutureless and glue-free conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery: A case series. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1474–7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurian A, Reghunadhan I, Nair KG. Autologous blood versus fibrin glue for conjunctival autograft adherence in sutureless pterygium surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:464–70. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadarajah G, Ratnalingam VH, Mohd Isa H. Autologous blood versus fibrin glue in pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft surgery. Cornea. 2017;36:452–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boucher S, Conlon R, Teja S, Teichman JC, Yeung S, Ziai S, et al. Fibrin glue versus autologous blood for conjunctival autograft fixation in pterygium surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50:269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng W, Dai H, Luo H. Evaluation of autologous blood in pterygium surgery with conjunctival autograft. Cornea. 2019;38:210–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodavoor SK, Ramamurthy D, Solomon R. Outcomes of pterygium surgery-glue versus autologous blood versus sutures for graft fixation-an analysis. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2018;11:227–31. doi: 10.4103/ojo.OJO_4_2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]