Abstract

PURPOSE:

To estimate the prevalence of allergic conjunctivitis (AC) and its related allergic ailments among Saudi adults in the western region.

METHODS:

Adult population of Taif, Makkah, and Jeddah cities was surveyed from 2017 to June 2018. Subjective questionnaire was used to collect the response. Participants were asked about symptoms (redness, itching, watering, based diagnosis and details of AC, treatment taken in the pasts, and associated conditions, such as allergic asthma and rhinitis). The age-sex-adjusted prevalence, its determinants, and associations to other ailments were assessed.

RESULTS:

We surveyed 2187 participants (mean age 26.0 ± 9.1 years). The age-sex-adjusted prevalence of AC was 70.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 68.6–72.4). There could be 2.1 million AC patients among 3.1 million adult populations in Western KSA. It was significantly higher in females compared to males (odds ratio [OR] = 1.7 [95% CI 1.4–2.2]). The risk of AC did not vary by age group (χ2 = 2.5, df = 3, P = 0.1). The variation of AC in three provinces was not significant (χ2 = 0.3, df = 3, P = 0.6). Dust (42.6%) and unknown (24.8%) allergens were the main causative agents of AC. AC was significantly associated to asthma (OR = 2.8) and allergic rhinitis (OR = 2.2).

CONCLUSION:

AC affects seven in ten adults in Western Saudi Arabia. AC is positively associated to allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Public health policies at primary eye-care level should focus on early detection and care of persons with AC.

Keywords: Allergic conjunctivitis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, prevalence

Introduction

Allergic conjunctivitis (AC) is a very common ocular disorder in patients and is frequently overlooked, misdiagnosed, and undertreated.[1] AC is prevalent in 6%–30% of the general population. Although seasonal AC is the most frequent form, cases mostly diagnosed and treated by eye-care professionals are chronic, mainly vernal and atopic keratoconjunctivitis.[2] In view of high magnitude and needing frequent ophthalmic care, it causes high disease burden on health-care providers; an understanding of AC, its prevalence, demographics, and treatment paradigms is always encouraged for policy-makers.

AC is mainly of two types; seasonal AC and chronic AC. The former is seasonal often associated with rhinitis, asthma, and nonsight-threatening. The later type of AC if not attended could be sight-threatening. Both pathogenesis and treatment modalities differ in these two types.[3]

A number of agents that trigger AC in the Asian subcontinent include house dust mites, grass and tree pollen, and dust storms.[4] Acute form is associated with allergic rhinitis in 30%–70% of cases[5] Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is associated with asthma.[6]

Many of ACs are treated at primary health-care (PHC) levels. In view of their chronic nature and acute onset in some of the children, self-treatment by parents is common. They include topical antihistamine and steroids both topical and parental form if associated with rhinitis and asthma.[7] Long-term unsupervised use of steroids is known to cause serious complications, such as glaucoma, cataract, and secondary infections.[8]

Although allergic rhinitis and asthma have been studied among Saudi children,[9,10] to the best of our knowledge, apart from Tabbara's[11] review of keratoconjunctivitis, epidemiology of AC is not studied in Saudi Arabia. This ailment being treated in primary, secondary, and tertiary eye care in addition to self-treatment by obtaining medications from pharmacies, institution-based information of AC is likely to be underestimated. Therefore, symptom-based diagnosis through a survey of the general population is a reliable and representative method of collecting information about AC.[12]

Three provinces in Western Saudi Arabia have different types of climatic and geographic scenario. Jeddah is a coastal area, Taif is partly mountainous and in places with unique vegetation, while Macca is dry and arid areas. Thus, different types of allergen could exist in these three areas.

We present the prevalence, causative agents, and determinants of AC among Saudi adults in the western region. We also correlated AC to coexisting allergic diseases, such as bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Methods

Institutional Research Ethics Board of Taif University Hospital approved this survey. This cross-sectional observational study was conducted between April 2017 and June 2018 in the three main cities of the western region in Saudi Arabia – Taif, Makkah, and Jeddah.

Adult residents of both genders and of three cities – Taif, Makkah, and Jeddah – were the study population. Their informed consent was obtained to participate in the survey.

We assumed that the prevalence of AC among the study population would be 5%.[13] To achieve 95% confidence interval (CI), acceptable error margin of 1% in a population of 10,000,000 with clustering effect of 1.2, we need to interview 2190 participants. The sample was further grouped for convenience into three city clusters.

Three medical doctors were investigators who surveyed and examined the participants. The questionnaire was prepared and tested in English during the pilot and then translated into Arabic language. It included demographic information – age, gender, and residency. The second section covered symptoms, causative agents, seasonal occurrence, and ophthalmic care for AC and the third section covered symptom-related coexisting conditions, such as bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis [Appendix 1].

A person having two or more symptoms out of redness, itching, burning, and excessive tearing but not having fever was suspected to suffer from AC.

Cases with symptom-based AC were examined using torchlight and an ophthalmic loupe (×2.5) (Keeler Ltd., UK). The lower lid was pulled to review both bulbar and lower tarsal conjunctiva to note congestion, discharge, follicles, and papilla. A case with two or more symptoms, confirmed by examination to have signs of AC, and those taking treatment for AC were labeled as having AC.

The data were transferred into spreadsheet of Microsoft XL®. After checking for inconsistencies and completeness of data collected, it was transferred for analysis using Statistical Package for the Social studies (SPSS-24, IBM, Chicago, Illinois (IL), USA). The adult Saudi population (>18 years old) of the three cities of Western Saudi Arabia was used as reference to study adequacy of the examined sample to the population by gender and age group. The population in both genders in age groups of 5–40 years was used for comparison. Based on unequal representation, age-sex-adjusted prevalence of AC and their 95% CIs were calculated. To correlate the determinants and coexisting allergic comorbidities to AC, we used 2 × 2 tables and estimated odds ratio (OR), its 95% CI, and two-sided P values. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We surveyed 2187 adult Saudi persons. Their demographic profile was compared to the subgroups of male and female population in the study area [Table 1]. Variation of population and examined persons by gender and age group was wide and therefore adjusted rates were calculated.

Table 1.

Comparison of adult Saudi population and surveyed participants by gender and age group

| Male | Age group | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population, n (%) | Surveyed, n (%) | Population, n (%) | Surveyed, n (%) | |

| 420,605 (29.7) | 453 (80.0) | 20-29 | 397,810 (25.9) | 1248 (77.0) |

| 342,961 (24.2) | 62 (11.0) | 30-39 | 333,150 (21.7) | 185 (11.4) |

| 653,002 (46.1) | 51 (9.0) | 40 and + | 806,967 (52.5) | 188 (11.6) |

| 1,416,568 (100) | 566 (100) | Total | 1,537,927 (100) | 1621 (100) |

The population, examined sample, cases of AC, crude rate, adjusted rates, and projected persons with AC in population by variants are given in Table 2. The prevalence of AC was 70.5% (95% CI 70.4–70.6). On its basis, there could be as many as 2.07 million adult Saudis suffering from AC in the study area.

Table 2.

Prevalence of allergic conjunctivitis among adult Saudi population of Western Saudi Arabia by variants

| Examined | With AC | Crude rate | Adjusted rate | 95% CI | Projected AC cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 566 | 428 | 75.6 | 67.5 | 67.4-67.6 | 956,137 |

| Female | 1621 | 1336 | 82.4 | 78.2 | 78.1-78.3 | 1,201,929 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 20-29 | 1701 | 1365 | 80.2 | 78.9 | 78.8-79.0 | 645,814 |

| 30-39 | 224 | 161 | 71.9 | 61.4 | 61.3-61.5 | 443,624 |

| 40+ | 243 | 201 | 82.7 | 70.3 | 70.2-70.4 | 980,089 |

| Study site | ||||||

| Taif | 942 | 764 | 81.1 | 39.2 | 39.1-39.3 | 582,821 |

| Macca | 861 | 693 | 80.5 | 69.6 | 69.5-69.7 | 564,393 |

| Jeddah | 384 | 307 | 79.9 | 77.2 | 77.1-77.3 | 1,119,429 |

| Total | 2187 | 1727 | 79.9 | 70.5 | 70.4-70.6 | 2,069,528 |

AC: Allergic conjunctivitis, CI: Confidence interval

The AC was associated with demographic variables and other systemic allergic morbidities [Table 3]. AC was positively and significantly associated with asthma (OR = 2.8) and allergic rhinitis (OR = 2.2).

Table 3.

Association of allergic conjunctivitis to other allergic comorbidities and demographic determinants

| With allergic conjunctivitis, n (%) | No allergic conjunctivitis, n (%) | Validation OR (95% CI), P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchial asthma | |||

| Present | 154 (14.2) | 62 (5.6) | 2.8 (2.0-3.8), <0.001 |

| Absent | 932 (85.8) | 1039 (94.4) | |

| Allergic rhinitis | |||

| Present | 271 (25.0) | 142 (12.9) | 2.2 (1.8-2.8), <0.001 |

| Absent | 815 (75.0) | 959 (87.1) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 291 (26.8) | 275 (25.0) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4), 0.2 |

| Female | 795 (73.2) | 826 (75.0) | |

| Age group | |||

| 20-29 | 815 (75.0) | 886 (80.5) | χ2=9.1, df=2, P=0.002 |

| 30-39 | 135 (12.4) | 112 (10.2) | |

| 40+ | 136 (12.5) | 103 (9.4) | |

| Province | |||

| Taif | 479 (44.1) | 463 (42.1) | χ2=0.1, df=2, P=0.7 |

| Macca | 399 (36.7) | 462 (42.0) | |

| Jeddah | 208 (19.2) | 176 (16.0) | |

df: Degrees of freedom, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

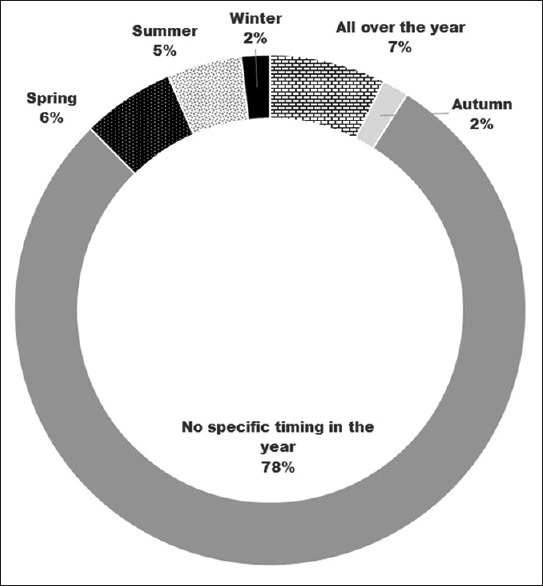

Among 1086 cases with AC, 194 respondents replied that their AC is not having any seasonal pattern. The seasonal pattern of 892 persons with AC is given in Figure 1. Nearly three-fourths of them did not have specific time in the year for allergy to exacerbate. One in ten AC patients had symptoms throughout the year.

Figure 1.

Allergic conjunctivitis cases presentation by season in Western Saudi Arabia

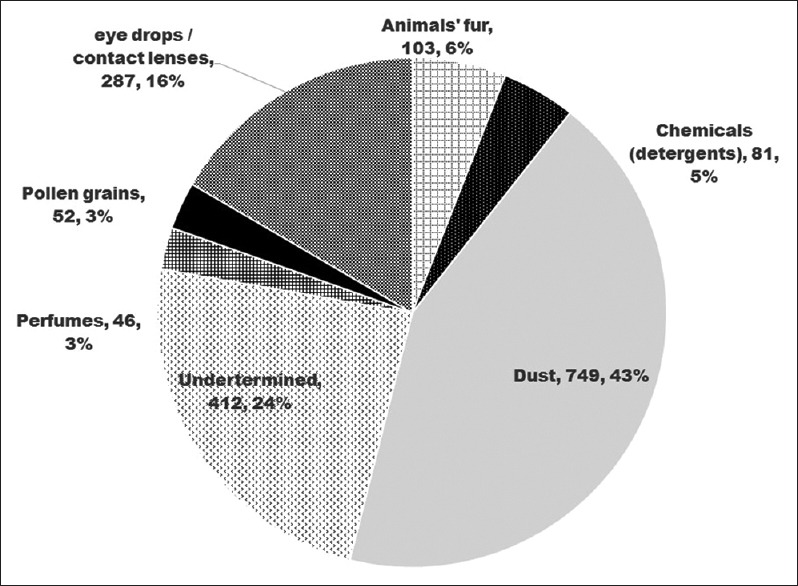

The replies on allergens that trigger AC among 1086 Saudi adults with AC were analyzed to study their distribution [Figure 2]. Dust (43%) and iatrogenic items (eye drops/contact lens) (16%) were the leading allergens. In as many as one-fourth of cases, the cause was unknown.

Figure 2.

Distribution of causative agents for allergic conjunctivitis in Western Saudi Arabia

Among 1086 AC cases, 497 (45.8%) had consulted ophthalmologists in the last 1 year for their eye ailment. In contrast, of the 1101 Saudi adults without allergy, only 47 (3.8%) had visited ophthalmic units (OR = 21.3, 95% CI 15.3–29.6, P < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, seven on ten adult Saudi persons aged 20 years and older suffer from AC. There could be more than 2 million people with AC in the three regions of Western Saudi Arabia. Adults aged 20–29 years had higher risk of AC. AC was positively associated with persons with bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis. The AC cases caused significant burden on the existing ophthalmic services in the study area.

This was perhaps the first study in the study area to determine the magnitude and determinants of AC in the adult population of Western Saudi Arabia. High prevalence of AC is a matter of concern. Integration of primary eye care in existing PHC and provision of adequate medications at primary level will reduce workload of this mainly nonsight-threatening episodic eye ailment. There is urgent need of establishing standard operating procedures to manage AC at different levels of eye care mainly at PHCs.

The prevalence of AC was significantly higher in the present study compared to the literature. Leonardi et al.[2] reported AC prevalence ranging from 6% to 30% and one-third of them are in children below 20 years of age. Among adult Korean population, the AC prevalence was 5.6%.[14] In Iran, the prevalence in the adult population was 15.9%.[15] In a study of 6–16-year-old Indian children, the prevalence of AC was as low as 8.5%.[16] There is a wide variation of AC by geographic area and age group. It would be interesting to study and compare the prevalence of AC in children of Western Saudi Arabia to the present study outcomes.

We found significantly higher risk of AC among adults aged 20–29 years than the older population. The risk of AC has been found to rise with age in children.[17] This could be accumulated cases which are not cured and not having cause-specific mortality. It could be possible that after adolescence, the body develops immunity toward allergen and resulting spontaneous resolution of AC in many cases.

We did not find significant variation in AC prevalence by gender. This was also noted both in adults and children with rhinoconjunctivitis.[18] The acquired factors for AC could influence equally in male and female population.

Three regions of Western Saudi Arabia reported similar prevalence. This observation should be interpreted with caution as sample representation in three study areas was different. It would be interesting to study causative agents in these three study areas with adequate sample.

Association of AC to asthma and rhinitis noted in the present study once again confirms common pathogenesis of these three entities.[7,14,15] All patients of bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis should be periodically checked for conjunctivitis and counseled to undergo standard eye treatment when AC exacerbates. Ophthalmologists should also be vigilant for the presence of asthma and rhinitis in AC patients.

One in six Saudi adults with AC was allergic to eye drops or contact lens and its allied products. This episode could be once only if proper care is taken. Both patient's caretaker and case record could have proper documentation so that exposure to the same irritant can be avoided.

Prevention of allergic attacks by avoiding the causative agent is a challenge. Saudi Arabia is a dry and desert area with population mainly residing in urban areas and in oasis. The date plantation in oasis also poses risk of pollens during the flowering season. Thus, suppressing the allergic symptom during exacerbation is the best way of improving the health-related quality of life of AC patients. As health services to all Saudi Nationals are provided free of cost, the need of such large number of medications at the nearest health institutions should be planned. Allergic diseases are rising in recent years.[19] Steroids give dramatic relief to such patients. Use of across the counter drugs to manage AC is common.[20] The availability of across the counter steroid medication to manage AC is a matter of concern, and to avoid long-term complications, policy-makers in the Kingdom should be more vigilant to prevent such practices. In addition, health promotion to AC patients about abuse of steroids should be aggressively carried out preferably at PHCs and using mass media.

There were few limitations in our study that are worth noting. The labeling of cases having asthma and rhinitis was based on subjective methods. This could have been influenced by recall bias, especially if symptoms were of mild nature. Thus, these conditions could be underestimates. The stratification of the study sample into three provinces was not done. Hence, the comparison of rate of AC by province should be done with a caution.

Conclusion

AC affects a considerable proportion of Saudi adult population in Western Saudi Arabia, and it is significantly associated with allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Possibility of having these allergic comorbidities in a patient should always be considered by ophthalmologists, allergists, and all health-care providers for early diagnosis and efficient management. Preventative measures and timely treatment of the symptoms should be highly recommended to provide better management for ocular allergy and accordingly better quality of life. Public health policies at primary eye-care level should focus on early detection and care of persons with AC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Title: “Prevalence of allergic conjunctivitis and co morbidity with asthma and allergic rhinitis among adult Saudi Population in Western Region”

Gender: (1)Male (2)Female

Age

City : (1) Taif (2) Makkah (3) Jeddah

-

Have you previously suffered from any of the following symptoms (eye redness, itching or burning in the eye, excessive tears in the eye) without fever?

-

(1)Yes

-

(2)No

-

(1)

-

If yes, what is the cause of these symptoms?

-

(1)Dust

-

(2)Some eye drops or contact lenses.

-

(3)Pollen grains

-

(4)Chemicals such as detergents

-

(5)Animals' fur

-

(6)Perfumes

-

(7)None

-

(1)

-

If yes, do you suffer from these symptoms during a specific season of the year?

-

(1)All over the year

-

(2)Winter

-

(3)Spring

-

(4)Summer

-

(5)Autumn

-

(6)No specific timing in the year

-

(7)I don't have allergic conjunctivitis

-

(1)

-

If yes, during the last 12 months, how many times did you experience these symptoms?

-

(1)one to four times

-

(2)Five to ten times

-

(3)More than 10 times

-

(4)I don't have allergic conjunctivitis

-

(1)

-

If yes, during the last 12 months, did you visit the ophthalmologist because of these symptoms?

-

(1)Yes

-

(2)No

-

(1)

-

Are you diagnosed with allergic conjunctivitis?

-

(1)Yes

-

(2)No

-

(1)

-

Do you have bronchial asthma?

-

(1)Yes

-

(2)No

-

(1)

-

Are you diagnosed with allergic rhinitis?

-

(1)Yes

-

(2)No

-

(1)

-

Have you previously suffered from any of the following symptoms ( Nasal obstruction, discharges or itching) without Fever ?

-

(1)Yes

-

(2)No

-

(1)

References

- 1.Berger WE, Granet DB, Kabat AG. Diagnosis and management of allergic conjunctivitis in pediatric patients. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38:16–27. doi: 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonardi A, Castegnaro A, Valerio AL, Lazzarini D. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis: Clinical appearance and treatment patterns in a population-based study. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:482–8. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schröder K, Finis D, Meller S, Wagenmann M, Geerling G, Pleyer U. Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmologe. 2017;114:1053–65. doi: 10.1007/s00347-017-0580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thong BY. Allergic conjunctivitis in Asia. Asia Pac Allergy. 2017;7:57–64. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2017.7.2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel DS, Arunakirinathan M, Stuart A, Angunawela R. Allergic eye disease. BMJ. 2017;359:j4706. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A major review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:133–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo M, Scott NW, Mustafa MZ, Mustafa MS, Azuara-Blanco A. Topical antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers for treating seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD009566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonini S, Coassin M, Aronni S, Lambiase A. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:345–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobki SH, Zakzouk SM. Point prevalence of allergic rhinitis among Saudi children. Rhinology. 2004;42:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hijazi N, Abalkhail B, Seaton A. Diet and childhood asthma in a society in transition: A study in urban and rural Saudi Arabia. Thorax. 2000;55:775–9. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.9.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabbara KF. Ocular complications of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1999;34:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Ghobain MO, Al-Hajjaj MS, Al Moamary MS. Asthma prevalence among 16- to 18-year-old adolescents in Saudi Arabia using the ISAAC questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen E, Celik S, Inanc M, Elgin U, Ozyurt B, Yılmazbas P. Seasonal distribution of ocular conditions treated at the emergency room: A 1-year prospective study. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2018;81:116–9. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20180026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang SY, Song WJ, Cho SH, Chang YS. Time trends of the prevalence of allergic diseases in Korea: A systematic literature review. Asia Pacific Allergy. 2018;12:547–56. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2018.8.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoormasti RS, Pourpak Z, Fazlollahi MR, Kazemnejad A, Nadali F, Ebadi Z, et al. The prevalence of allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis and asthma among adults of Tehran. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47:1749–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao GN, Sabnam S, Pal S, Rizwan H, Thakur B, Pal A. Prevalence of ocular morbidity among children aged 17 years or younger in the eastern India. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1645–52. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S171822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh S, Sharma BB, Salvi S, Chhatwal J, Jain KC, Kumar L, et al. Allergic rhinitis, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema: Prevalence and associated factors in children. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:547–56. doi: 10.1111/crj.12561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retzler J, Grand TS, Domdey A, Smith A, Romano Rodriguez M. Utility elicitation in adults and children for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and associated health states. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:2383–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1910-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterner T, Uldahl A, Svensson Å, Björk J, Svedman C, Nielsen C, et al. The Southern Sweden adolescent allergy-cohort: Prevalence of allergic diseases and cross-sectional associations with individual and social factors. J Asthma. 2019;56:227–35. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1452033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meltzer EO, Farrar JR, Sennett C. Findings from an online survey assessing the burden and management of seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in US patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:779–89e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]