Abstract

Although ideation-to-action theories of suicide aim to explain the emergence of suicidal behaviors, researchers have primarily focused on the content of underlying mechanisms (i.e., who dies by suicide). Much less attention has focused on the temporal dynamics of suicide risk (i.e., when suicide occurs). The fluid vulnerability theory conceptualizes suicide as an inherently dynamic construct that follows a nonlinear time course. Newer research implicates the existence of multiple nonlinear change processes among suicidal individuals, some of which appear to be associated with the emergence of suicidal behavior. The cusp catastrophe model provides a useful model for conceptualizing these change processes and provides a foundation for explaining a number of poorly understood phenomena including sudden emergence of suicidal behavior without prior suicidal planning. The implications of temporal dynamics for suicide-focused theory, practice, and research are discussed.

Keywords: suicide, dynamical systems theory, fluid vulnerability theory, nonlinearity

Globally, suicide accounts for an estimated 800,000 lives lost each year, making it the seventeenth leading cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2018). In the United States, suicide has consistently ranked in the top ten causes of death and accounts for more deaths per year than homicide, motor vehicle accidents, and armed conflict combined (Stone et al., 2018). Over the past decade, the U.S. suicide rate has steadily risen (Stone et al., 2018) despite increasing public awareness about suicide, dissemination of suicide “warning signs,” identification of effective treatments for reducing suicidal behaviors, and implementation of suicide prevention programs across schools, healthcare systems, and communities. Suicide therefore remains a vexing public health issue, prompting researchers to focus efforts on understanding the processes that underlie suicidal thoughts and behaviors, identifying high-risk individuals, predicting who will engage in suicidal behaviors, and testing interventions for vulnerable individuals. Despite several decades of research, however, our ability to understand the underlying processes of suicide risk and to reliably predict suicidal behaviors has not meaningfully improved (Franklin et al., 2017).

Researchers have previously argued that progress has been limited by the absence of theories that comprehensively explain the universe of suicide-related phenomena (O’Connor, 2011; Joiner, 2007; Klonsky & May, 2015; Van Orden et al., 2010). In an attempt to address this gap, newer theories and models of suicidal behavior have emerged. Collectively, these models are referred to as “ideation-to-action” models (Klonsky & May, 2014) because of their emphasis on delineating the mechanisms by which individuals develop suicidal ideation from those implicated in suicidal behavior. The introduction of these theories has catalyzed a considerable increase in research aimed at identifying and understanding these mechanisms. For example, the number of published studies focused on the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner, 2007), the most prominent of the ideation-to-action models, increased by almost 11-fold during 2011–2015 as compared to 2005–2010 (Chu et al., 2017). To date, research studies on the ideation-to-action paradigm have largely focused on identifying and describing the content of these mechanisms, consistent with a primary aim to understand what constructs and in what combinations are necessary for suicide attempts to occur. Much less empirical attention has been devoted to understanding the temporal process of suicide risk fluctuation over time. Temporal processes are key to understanding the emergence of suicidal behavior, but what do these change processes look like and how might these change processes provide information about the emergence of suicidal behavior? These questions are the focus of the present work.

Suicide as an Emergent Phenomenon

Emergence refers to the process by which a phenomenon comes into existence (Goldstein, 1999). Emergent phenomena do not result from a single event, variable, or construct; rather, they involve the interaction of many components within the system, such that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The byproduct of emergence is patterns of change through time, which means that different states for the system are associated with unique change processes. Under most conditions, an individual’s change patterns demonstrate stable properties because of homeostasis—the tendency of a system to employ self-regulatory strategies to establish and maintain an equilibrium among its interacting components (Jaeger & Monk, 2014). When one component of the system is thrown off balance, the other components of the system respond in a manner designed to reestablish the original component’s homeostatic balance, thereby maintaining stability over time. For example, an individual who experiences an acute stressor (e.g., relationship problems) may soon thereafter experience intense emotional arousal (e.g., anger, sadness). Owing to built-in homeostatic forces, the individual might subsequently engage in positive self-talk, reach out to a friend or trusted person to vent, and/or engage another coping strategies (e.g., exercise), all of which are designed to counteract emotional arousal, thereby returning the individual to his or her previous state. When these self-regulatory processes fail, however, the system destabilizes and the likelihood of shifting to another state occurs. Returning to the previous example, if the individual experiencing intense emotional arousal responds to this event with rumination and self-criticism, social isolation, and/or maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., substance use), emotional arousal could intensify, thereby moving the individual away from his or her previous state and towards a higher risk state that could include suicidal behavior.

As applied to suicide, the concept of emergence holds several implications. First, within an individual, multiple states of suicide risk must exist, one characterized by a low probability for suicidal behavior (i.e., low risk) and one characterized by a high probability for suicidal behavior (i.e., high risk). Other suicide risk states might also exist, but these two states are minimally required. Next, low risk states are associated with self-regulatory processes designed to maintain homeostatic balance. By extension, the likelihood that suicidal behavior will emerge is significantly increased when an individual switches from a low risk state to a high risk state as a consequence of failed self-regulation. Because the properties and features of a low risk state are so different from the properties and features of a high risk state, the emergence of suicidal behavior is difficult to anticipate without consideration for self-regulatory processes. Because self-regulation is reflected in the patterns of change evident across a system’s constituent components over time, examination of temporal patterns could provide information about an individual’s vulnerability to switching to a high risk state and engaging in suicidal behavior. Temporal patterns therefore warrant greater attention by suicide researchers and clinical practitioners.

The Fluid Vulnerability Theory

The fluid vulnerability theory was first articulated more than a decade ago as a model for understanding the temporal dynamics of suicide risk over time (Rudd, 2006). As originally described, the fluid vulnerability theory conceptualizes suicide risk along two dimensions: baseline, which refers to the chronic or stable properties of suicide risk that persist over time, and acute, which refers to the dynamic properties of suicide risk that are reactive to external forces. The baseline dimension is therefore influenced by risk and protective factors that are historical and/or relatively static in nature (e.g., genetics, trauma, demographics, and previous suicidal behavior), and corresponds to the homeostatic point of equilibrium for an individual’s low risk state. The acute dimension, by contrast, is influenced by risk and protective factors that fluctuate in response to environmental contingencies and/or internal experiences (e.g., mood, hopelessness, substance use), and corresponds to within-person differences in risk.

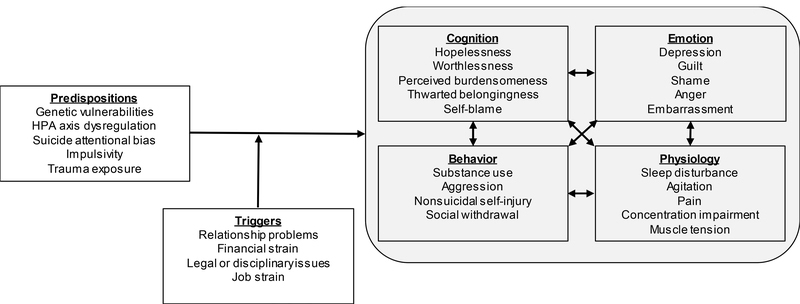

As noted previously, phenomena emerge as the result of complex interactions across multiple components of a system. This corresponds with the concept of the suicidal mode (see Figure 1), a structural element embedded within the fluid vulnerability theory that provides a conceptual model for organizing the many risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior (Beck & Haigh, 2014). Within the suicidal mode, predispositions coincide with the baseline dimension of risk because it includes relatively stable variables whereas the larger grey box to the right coincides with the acute dimension of risk because it includes dynamic, time-dependent variables. These dynamic variables can be organized into a network of four domains that are mutually influential: cognition, emotion, behavior, and physiology. The arrow flowing from predispositions to these four components represents the fact that an individual’s predispositions influence the manifestation of acute risk and protective factors, but the strength of this influence is moderated by environmental stressors and context, referred to as triggers.

Figure 1.

The Suicidal Mode

Central to the suicidal mode is the possibility for suicidal behavior to result from different combinations of triggers, predispositions, and risk factors under different circumstances (Monroe & Simons, 1991; Rudd, 2006). The “formula” for the onset of suicidal behaviors is impacted by the ratio of an individual’s predispositions relative to his or her experienced triggers as well as the degree of match between a stressful event and the individual’s predisposing vulnerabilities, akin to a lock and a key. Specifically, when the right amount or type of stress (the key) is present, it can unlock the suicide-specific vulnerability (lock). When the wrong type of stress is present, however, it does not unlock the suicide-specific vulnerability. In the former situation, a relatively mild stressor nonetheless leads to an intense suicidal episode and/or suicidal behavior whereas in the latter situation, even very severe stressors may not result in suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Once the diathesis is “opened”, a series of other cognitive, affective, behavioral, and physiological processes unfold and suicidal ideation and behavior become active and more intense. According to the theory, an individual with many predispositions can be triggered by a wider variety of stressors (i.e., many keys fit in the lock) than an individual with fewer predispositions (i.e., only one key fits in the lock). As a result, the former group is more likely to shift from a low risk to a high risk state.

As an emergent phenomenon, suicidal behavior is greater than the sum of its parts. Extending from this logic, the fluid vulnerability theory does not prioritize any particular construct or variable over another and does not assume that certain combinations of constructs and variables are better indicators of the emergence of suicidal behavior under all circumstances. This perspective is akin to understanding the emergence of hurricanes. Hurricanes come into being as a result of positive feedback loops among many different variables including wind, humidity, air pressure, warm water, warm air, the rotation of the Earth, and more. By themselves, none of these variables can cause a hurricane, and none of these variables are necessarily more or less important than the others. Furthermore, change in any one of these variables does not necessarily lead to a proportional change in the overall behavior of the hurricane; a 10% change in air pressure, for example, does not necessarily result in a 10% change in hurricane size or speed. Finally, there is no single “correct” combination or levels of these variables; the very same combination of variables that result in hurricanes under certain circumstances (for example, when occurring in the Gulf of Mexico) do not necessarily result in hurricanes under different conditions (for example, when occurring over a large land mass).

In like manner, the suicidal mode implicates the importance of multiple different types of interactions: interactions within individuals among the various components of the suicidal mode (e.g., cognition impacts emotion, emotion impacts physiology, cognition and emotion drive behavior, etc.); interactions between individuals and their environment (e.g., triggers); and interactions between the individual and his or her history with the environment (e.g., predispositions). These interactions will sometimes lead to an increase in suicide risk but sometimes they will not. When in a low risk state, the interactions among these various components demonstrate stable properties because they reflect homeostasis. If an individual’s self-regulatory processes are disrupted, however, they may experience a shift towards a higher risk state characterized by increased probability of suicidal behavior. Critically, these disruptions would be identifiable only when examining temporal processes, similar to how the transition from a tropical depression to a tropical storm to a hurricane is identifiable primarily by examining temporal processes, notably the onset of rotational movement and an increase in wind speed. Change processes can therefore provide unique information about the state of a system that cannot be readily derived from the its constituent components.

Change Processes Associated with Remaining in a Low Risk State

When one component of a system is thrown off balance, we can reasonably expect that the other components of the system will counteract this disturbance in order to reestablish homeostasis. For example, when a triggering event occurs, an individual is pushed away from his or her homeostatic point of equilibrium, also known as a set point, and may experience change across one or more domains of the suicidal mode. This change in emotion, cognition, behavior, and/or physiology can lead to temporary increases in suicide risk (e.g., the desire to die or active suicidal ideation). In response to these disturbances, self-regulatory strategies are automatically employed to reestablish homeostasis, consistent with a negative feedback loop. An individual may, for example, seek out social support and/or use stress management or cognitive reappraisal strategies to offset their negative mood and thoughts, thereby reducing suicide risk and preserving balance within a low risk state. Consistent with this expectation, nonlinear patterns of suicidal ideation have been observed in multiple studies of suicidal individuals (Bryan et al., 2016, 2017; Bryan & Rudd, 2017; Kleiman et al., 2017; Shiepek et al., 2011).

Several lines of evidence suggest that variability in suicide risk is less pronounced among lower risk individuals. Individuals who have not attempted suicide, for instance, demonstrate smaller fluctuations in suicidal ideation when measured on a weekly (Bryan & Rudd, 2018) and even daily basis (Witte, Fitzpatrick, Joiner, & Schmidt, 2005; Witte, Fitzpatrick, Warren, Schatschneider, & Schmidt, 2006). Momentary fluctuations in mood state, assessed multiple times per day via experiential sampling methods, have also been found to be associated with less severe suicide risk (Palmier-Claus, Taylor, Gooding, Dunn, & Lewis, 2011). Among treatment-seeking individuals with a history of one suicide attempt, Bryan et al. (2019) further found that fluctuations in suicidal ideation, assessed once per week, were much smaller in magnitude among patients who did not attempt suicide during or after treatment as compared to patients who eventually made a second suicide attempt. A change process characterized by mild and/or gradual fluctuations in suicide risk may therefore signal self-regulatory negative feedback loops associated with the absence of suicidal behavior. We refer to this change process as stable because the system repeatedly returns to its set point after experiencing disturbance caused by an external force. Stability therefore does not necessarily connote a complete absence of change, but rather a tendency to return to one’s set point.

Change Processes Associated Transitioning to a High Risk State

Under certain circumstances, the interactions among the suicidal mode’s various components serve to counteract rather than preserve homeostasis (Butner, Gagnon, Geuss, Lessard, & Story, 2015), consistent with a positive feedback loop. Positive feedback loops serve to destabilize the system, thereby increasing the likelihood of transition to a high risk state. For example, if an individual who feels disappointed (an emotion) after a triggering event subsequently engages in self-criticism (a cognition) and social withdrawal (a behavior), his or her depression could be magnified, which could lead to increased alcohol consumption (a behavior), guilt (an emotion), and perceptions of burdensomeness (a cognition), all of which reinforce social withdrawal, self-criticism, and depression. This “downward spiral” essentially entails the collapse of self-regulation, such that the individual moves away from his or her homeostatic set point and becomes increasingly vulnerable to switching to a high risk state. Returning to homeostasis is still possible under these conditions, but only if the individual’s self-regulatory processes can be activated early enough and to a sufficient degree, before the system shifts to the higher risk state. Consistent with this pattern, positive feedback loops across cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domans have been identified among individuals who have attempted suicide (Loveys, Crutchley, Wyatt, & Coppersmith, 2017). In addition, significantly larger fluctuations in suicidal ideation have been observed among individuals who repeatedly engage in suicidal behaviors (Bryan & Rudd, 2017; Kleiman et al., 2017; Witte, Fitzpatrick, Joiner, & Schmidt, 2005). These fluctuations increase in magnitude in the time leading up to the emergence of suicidal behavior (Bryan et al., 2018; Bryan, Butner, Rozek, & Rudd, 2019). Taken together, rapid and large fluctuations in suicide risk that severely depart from an individual’s homeostatic equilibrium may therefore signal dysregulatory positive feedback loops associated with the emergence of suicidal behavior. We therefore refer to this change process as dysregulated.

Yet another possible change process involves the introduction of a sufficiently forceful event in which rapid and dramatic departure from homeostatic equilibrium occurs, quickly overwhelming the individual’s built-in self-regulatory processes. Under these conditions, a sudden transition to a high risk state occurs, seemingly “out of the blue.” Such change processes are discontinuous, meaning they appear to be disjointed and qualitatively distinct from previous states. Consistent with this pattern, exponential increases in the severity of suicidal ideation in the days and hours immediately preceding a suicide attempt have been reported by psychiatric patients (Bagge, Littlefield, Conner, Schumacher, & Lee, 2014; Millner et al., 2017). Considerable research further indicates that 75–90% of individuals who attempt suicide report making the final decision to act within the preceding hour (Bryan, Garland, & Rudd, 2016; Millner et al., 2017; Simon et al., 2001), and over half report making the attempt without any advance planning, apparently “skipping” over this intermediate step (Borges, Walters, & Kessler, 2000; Conner et al., 2006, 2007; Jeon et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2010; Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999; Nock et al., 2014; Ursano et al., 2015; Wyder & DeLeo, 2007). We refer to this change process as discontinuous.

The Cusp Catastrophe Model

Although each of these nonlinear change processes (i.e., stable, dysregulated, and discontinuous) are qualitatively distinct from each other (see Table 1), all three “types” are possible within catastrophic change models. Catastrophic change models are a specific subtype of change processes in which small changes in certain parameters of a nonlinear system can cause points of equilibrium to change, for example by appearing or disappearing, or switching from stabilizing to destabilizing (and vice versa), resulting in disproportionately large and sudden change in the behavior of the system akin to the third change process described above (Thom, 1989). Of the many catastrophic change processes that have been described (e.g., Zeeman, 1976), the cusp catastrophe model has proven especially valuable for understanding a range of complex behavioral phenomena including anorexia, alcohol use, violence and aggression, and nonsuicidal self-injury (Armey & Crowther, 2008; Armey, Nugent, & Crowther, 2012; Butner et al., 2015; Clair, 1998; Hufford, 2001; Zeeman, 1976). Preliminary evidence suggests the cusp catastrophe model may be especially useful for understanding the temporal process of suicide risk and the emergence of suicidal behavior (Bryan & Rudd, 2017; Schiepek et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Properties of three possible temporal processes for suicide risk

| Type | Properties |

|---|---|

| Stable | Slow, smooth, and mild fluctuations around the homeostatic equilibrium point. |

| Dysregulated | Rapid, large fluctuations around the homeostatic equilibrium point. |

| Discontinous | Sudden, dramatic departure from the homeostatic equilibrium point. |

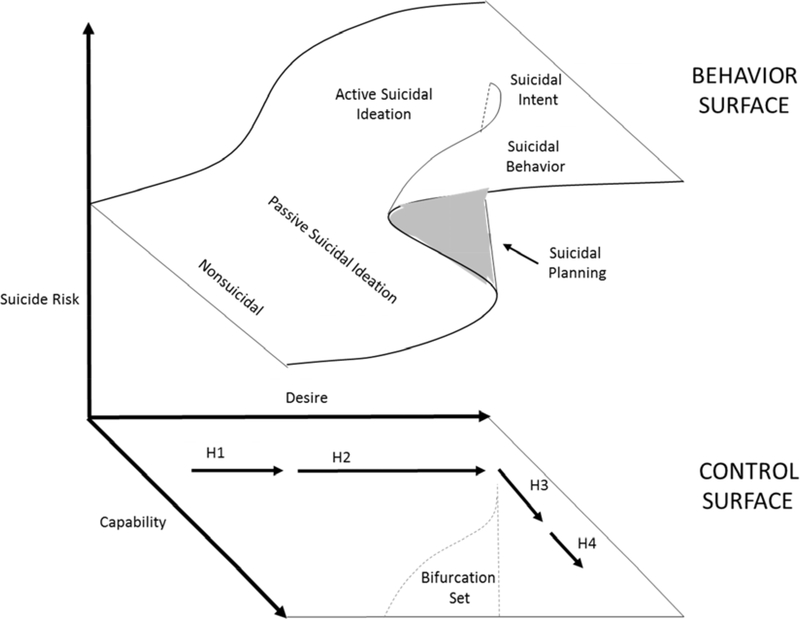

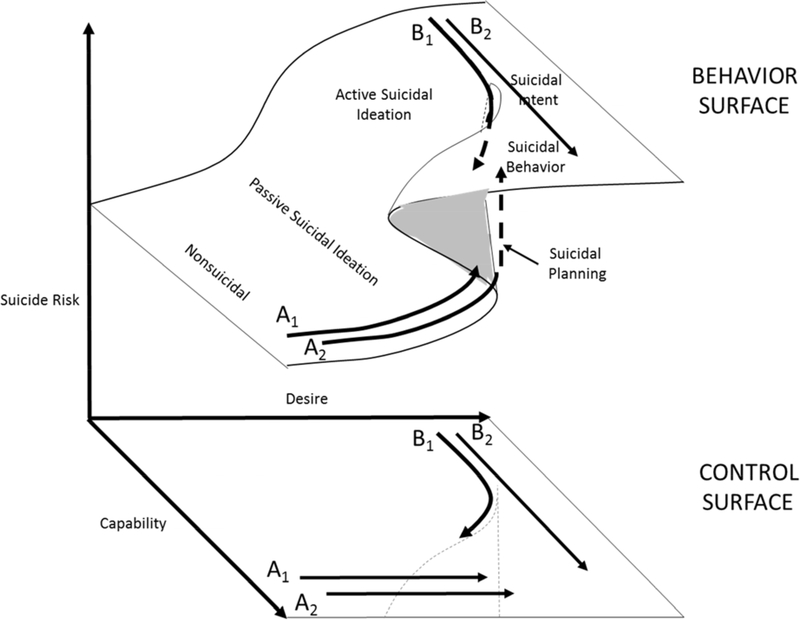

The cusp catastrophe model is characterized by several properties (Zeeman, 1976; Bryan & Rudd, 2017): (1) the system has two distinct states; (2) change between these two states occurs suddenly; (3) certain states are highly improbable; (4) very small changes in conditions can lead to very different outcomes; and (5) transitions from one state to the other do not necessarily coincide with transitions in the opposite direction. Figure 2 provides a visual model for understanding these properties. In this figure and our subsequent discussion, we will use the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner, 2007) for illustrative purposes. We selected the interpersonal-psychological theory primarily because of its familiarity and popularity among contemporary researchers and clinicians, as well as existing research indicating the theory’s central constructs demonstrate nonlinear temporal patterns that conform to the key tenets of dynamical systems theory and emergence (Bryan, Sinclair, & Heron, 2016; Rogers & Joiner, 2019). The principles discussed below are applicable and relevant to other conceptual models and other combinations of variables.

Figure 2.

A cusp catastrophe model of suicidal behavior with suicidal desire and suicidal capability, the two main dimensions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide, serving as control parameters along the axes of the control surface. Suicide risk is represented on the vertical axis, and ranges from nonsuicidal to suicidal behavior. All possible combinations of desire and capability comprise the behavior surface. For most combinations of desire and capability, there is only one probable level of suicide risk, but within the boundaries of the bifurcation set, there are two probable levels (nonsuicidal and suicidal behavior) and one improbable level (suicidal planning). The interpersonal psychological theory’s four hypotheses describing the pathway to suicidal behavior are plotted on the control surface.

A detailed description of the interpersonal-psychological theory can be found elsewhere (e.g., Joiner, 2007; Van Orden et al., 2010), but in brief, the theory articulates four central hypotheses about how individuals transition from being nonsuicidal to experiencing suicidal ideation and, in some cases, enacting suicidal behavior (Van Orden et al., 2010):

Passive suicidal ideation results from either elevated thwarted belongingness or elevated perceived burdensomeness;

Active suicidal ideation results from hopelessness about passive suicidal ideation;

Suicidal intent results from the combination of active suicidal ideation and lowered fear of death; and

Suicidal behavior results from the combination of suicidal intent and increased pain tolerance.

The several constructs included in these hypotheses can be organized into two superordinate constructs: suicidal desire, which includes perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and hopelessness; and suicidal capability, which includes fearlessness of death and pain tolerance. The progression from being nonsuicidal to suicidal behavior therefore occurs sequentially as a consequence of increasing suicidal desire (i.e., nonsuicidal to passive suicidal ideation to active suicidal ideation) and, among those with high suicidal desire, increasing suicidal capability (i.e., active suicidal ideation to suicidal intent to suicidal behavior).

In Figure 2, the vertical axis represents suicide risk and the horizontal axes represent these two superordeinate constructs. The two-dimensional plane located at the bottom of the figure represents the control surface, on which the various levels of desire and capability can be plotted. Above the control surface is the behavior surface, which represents all of the possible manifestations of suicide risk. In combination, these two surfaces reflect how different manifestations of suicide risk (the behavior surface) can result from various combinations of desire and capability (the control surface). To demonstrate how these two surfaces are interpreted, the interpersonal psychological theory’s four hypotheses are plotted on the control surface and the locations for each intervening step of the transition from being nonsuicidal to suicidal behavior are labeled on the behavior surface. As suicidal desire increases on the control surface (the first and second hypotheses), overall suicide risk increases from nonsuicidal to passive suicidal ideation and then active suicidal ideation. Next, as suicidal capability increase on the control surface (the third and fourth hypotheses), suicide risk transitions to suicidal intent and then to suicidal behavior.

Note that for most combinations of desire and capability, there is only one possible level of suicide risk. However, at the bottom center of the control surface, within the wedge labeled “bifurcation set,” multiple manifestations of suicide risk are possible as a result of the double fold located in the behavior surface. Within this wedge-shaped segment, three levels of suicide risk are possible: passive suicidal ideation on the lower fold, suicidal behavior on the upper fold, and suicidal planning on the middle fold. The lower and upper folds represent the most probable or likely suicide risk states whereas the middle fold represents the least probable or unlikely suicide risk state. In other words, when an individual has a combination of desire and capability that falls within the borders of the bifurcation set, two outcomes are possible: passive suicidal ideation or making a suicide attempt. Conversely, suicidal planning is a highly improbable outcome.

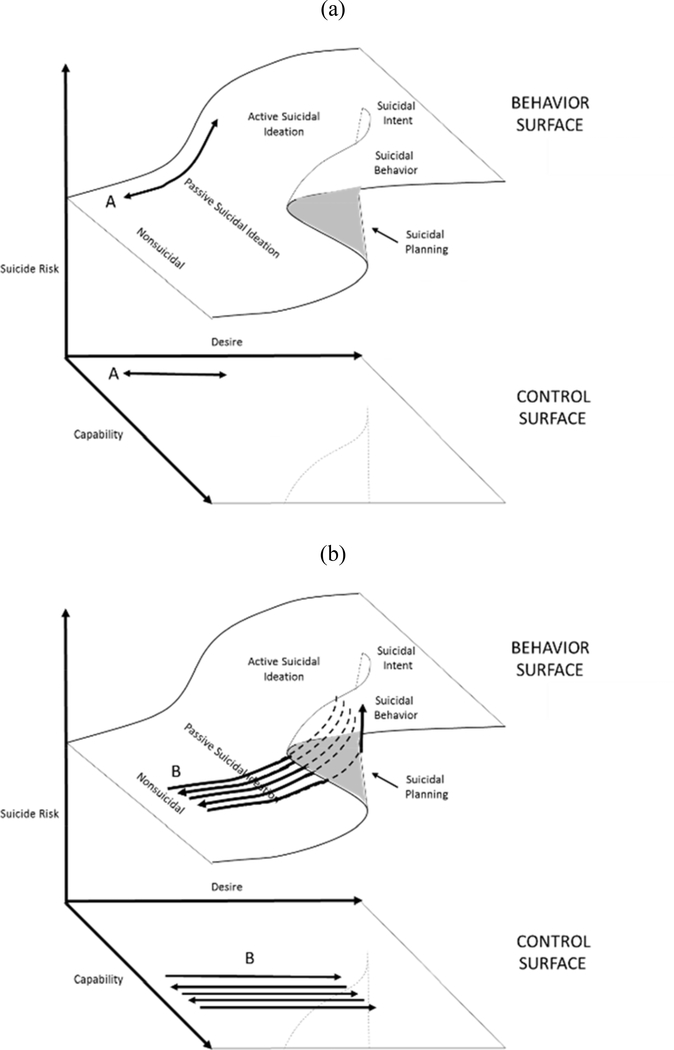

To illustrate how the double fold of the cusp catastrophe model can result in the three types of change processes previously discussed, an example of each pathway is depicted in Figure 3. Pathway A reflects the slow, smooth fluctuations in suicidal desire that have been observed among lower risk suicidal individuals (Bryan et al., 2016, 2018; Bryan & Rudd, 2017; Kleiman et al., 2017). This pathway involves a back-and-forth movement along the control surface, reflecting the ebb and flow of suicidal desire. The phenomenological experience of this change process can be understood by considering how this pathway is reflected on the behavior surface. As suicidal desire increases, an individual on this pathway develops passive suicidal ideation and then starts to climb the behavior surface towards active suicidal ideation. Approximately half way up the slope, the individual reverses direction and moves back through passive suicidal ideation, eventually returning to a nonsuicidal state. This process may repeat multiple times, but eventually we might expect this movement to come to rest in a low risk state.

Figure 3.

Three potential change patterns among suicidal individuals: (a) stable, (b) dysregulating, and (c) catastrophic.

Pathway B reflects the rapid, large fluctuations in suicidal desire associated with the dysregulated change process that has been observed among individuals who repeatedly engage in suicidal behavior (Bryan & Rudd, 2017; Bryan et al., 2018, 2019; Kleiman et al., 2017; Witte, Fitzpatrick, Joiner, & Schmidt, 2005). Similar to Pathway A, Pathway B also pathway involves an ebb and flow of suicidal desire, but this change process is combined with a gradual increase in suicidal capability. Because Pathway B begins at a higher level of capability, the pathway eventually crosses into the bifurcation set region, where the behavior slope is much steeper. An individual following this pathway would therefore develop passive suicidal ideation and then active suicidal ideation but would experience a much more rapid return to a nonsuicidal state. As suicidal capability increases, the slope of the behavior surface becomes increasingly steep, resulting in larger and more rapid fluctuations in suicide risk states, to include episodic suicidal planning. Eventually, the individual experiences a large enough increase in suicidal capability that their pathway crosses the boundary of the bifurcation set. At this point, the individual jumps from the lower fold to the upper fold, at which point a suicide attempt occurs.

Finally, Pathway C reflects the sudden, dramatic shift in suicide risk states associated with the discontinuous change process. An individual following Pathway C begins with high suicidal capability combined with low suicidal desire. As suicidal desire increases, passive suicidal ideation develops but before active suicidal ideation emerges, the individual crosses the boundary of the bifurcation set, jumping to the upper fold and attempting suicide. If interviewed after this suicide attempt, an individual who followed Pathway C would likely deny any suicidal planning prior to the attempt, a phenomenological experience reported by a significant number of individuals who have attempted suicide (Borges, Walters, & Kessler, 2000; Conner et al., 2006, 2007; Jeon et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2010; Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999; Nock et al., 2014; Ursano et al., 2015; Wyder & DeLeo, 2007).

When considering these various pathways to suicidal behavior, it is important to keep in mind that the concept of emergence is based on the assumption of within-person, not between-person, change processes. What this means is that the specific shape and form of the cusp catastrophe model does not necessarily differ between those who attempt suicide and those who do not. The conditions under which any individual will transition from their own low risk state to their own high risk state will differ; one person may transition to a high risk state when experiencing only a moderate level of suicidal desire whereas another person may not transition to a high risk state even when experiencing a high level of suicidal desire. Although this boundary between low and high risk states is not fixed across individuals, it can be estimated for each person by examining the characteristics and features of his or her temporal patterns. For instance, Bryan and Rudd (2018) showed that the cusp catastrophe model could be estimated by modeling week-by-week fluctuations in suicidal ideation among psychiatric outpatients. Bryan et al. (2019) subsequently found that within-person nonlinear change patterns characterized by large, sudden shifts in suicidal ideation signaled the later emergence of suicidal behavior. Catastrophic change processes within patients have also been observed and described by Shiepek et al. (2011).

As noted above, emergence implicates unique change processes associated with different states. What this means is that, in the time preceding the transition to a high risk state, change patterns may themselves change. For example, Bryan et al. (2018) observed that nonlinear change processes in social media content became more pronounced and extreme in the months and weeks preceding an individual’s death by suicide. In other words, individuals who died by suicide initially showed a change process akin to Pathway A but eventually shifted to a change process akin to Pathway B. Examining nonlinear change patterns—as well as change in change patterns—may therefore provide a novel, person-centered method for monitoring suicide risk over time.

Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice

As noted previously, a central assumption of the fluid vulnerability theory is that suicide risk possesses both stable and dynamic properties, an assumption that implicates a nonlinear time course. The cusp catastrophe model provides a useful foundation for understanding the various change processes implicated by the fluid vulnerability theory. Research suggests that different types of change processes may be associated with different risk states as well as the emergence of suicidal behavior. Consideration of temporal processes, especially catastrophic change processes, therefore holds promise for advancing suicide theory, research, and practice.

The first and arguably most basic implication of the fluid vulnerability theory is the strong likelihood that multiple pathways can lead to suicidal behavior. The cusp catastrophe model provides a framework for understanding this possibility. Consider, for example, how Pathway B and Pathway C, depicted in Figure 3, both started in a nonsuicidal state and ended with suicidal behavior, but the two pathways were very different from each other. Whereas Pathway B was highly turbulent, with frequent “switching” back and forth between higher risk and lower risk states, Pathway C was characterized by a slow and gradual initial increase in suicide risk followed by a very sudden shift to suicidal behavior. The differences between two pathways implicate very different approaches to suicide prevention. For an individual following Pathway B, psychological treatment that focuses on strengthening self-regulatory processes may be indicated. For example, dialectical behavior therapy and brief cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention are empirically supported treatments for reducing suicidal behavior (e.g., Brown et al., 2005; Linehan et al., 1991, 2006, 2015; Rudd et al., 2015) that emphasize skills training in self-regulation (Bryan & Rozek, 2018).

Psychological treatment may also be helpful for an individual following Pathway C, but it seems unlikely that many individuals following this particular pathway will access mental healthcare because, up until the moment of their suicide attempt, they have largely remained in a low risk state. For such individuals, suicidal planning may not be the only intermediate risk level that is “skipped” during their catastrophic switch from a low risk state to a high risk state; active suicidal ideation might also be skipped. Previous research has found, for instance, that approximately 10% of individuals who deny experiencing active suicidal ideation have nonetheless made a suicide attempt (Millner, Lee, & Nock, 2015). Likewise, approximately one in four individuals who have attempted suicide say they did not experience any form of active suicidal ideation prior to the attempt (Wyder & DeLeo, 2007). Given the difficulty in predicting or anticipating suicidal behavior in this subgroup, means restriction strategies or broad based public health initiatives may be more relevant and effective for preventing their suicidal behaviors.

The cusp catastrophe model might also provide a model for understanding the poor performance of many suicide risk screening and assessment methods. A recent meta-analysis of hundreds of studies conducted over the past 50 years found that suicide ideation is only weakly correlated with suicide death and suicide attempts (Franklin et al., 2017). A separate meta-analysis of 70 studies similarly found that the positive predictive value of suicidal ideation as a predictor of death by suicide was less than 4% (McHugh, Corderoy, Ryan, Hickie, & Large, 2019). The weak association of suicidal ideation with later suicidal behaviors is partly due to the fact that over 90% of those who endorse suicidal ideation do not subsequently engage in suicidal behavior (Simon et al., 2013) and partly due to the fact that up to half of those who engage in suicidal behavior deny experiencing suicidal ideation in advance (Carter et al., 2017; McHugh et al., 2019). A common explanation for these findings is respondent bias and/or recall bias, such that individuals who attempt suicide or die by suicide are presumed to be discounting or overlooking past episodes of suicidal ideation and/or planning (Anestis, Pennings, & Williams, 2014; Anestis, Soberay, Gutierrez, Hernandez, & Joiner, 2014). This explanation is probably true for a certain percentage of those who deny suicidal ideation and planning prior to a suicide attempt. Considering the transition from ideation to action from the perspective of the cusp catastrophe model, however, introduces the possibile (and likely) existence of a subgroup of individuals who engage in suicidal behavior without first experiencing active suicidal ideation.

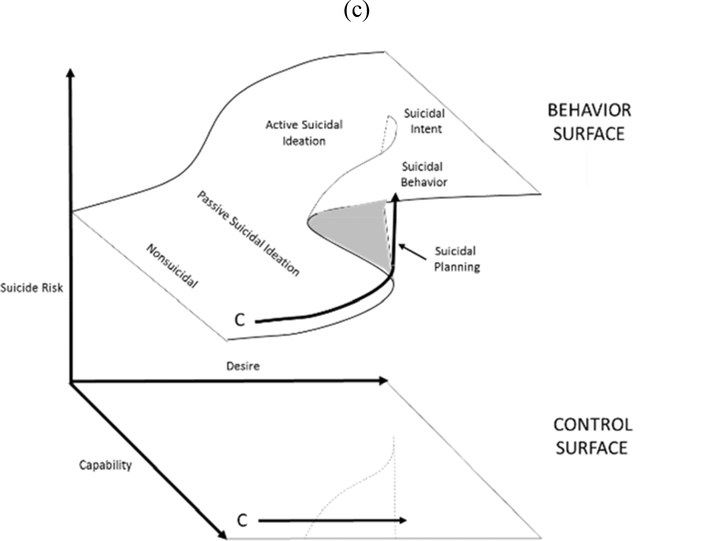

Yet another explanation is that sporadic and/or infrequent assessment is insufficient for capturing the dynamic nature of the transition from suicidal ideation to behavior. Consider, for example, the two pairs of pathways depicted in Figure 4, which represent four different individuals. Pathways A1 and A2 both start with comparable levels of suicidal capability and desire and both experience a comparable increase in desire, but only Pathway A2 crosses the boundary of the bifurcation set, resulting in a catastrophic shift to suicidal behavior. If assessed at the start of their journeys, both pathways would likely screen negative for suicidal ideation, but one pathway would nonetheless result in suicidal behavior. Pathway A2 would therefore be classified as a false negative. Conversely, Pathways B1 and B2 both start with comparable levels of suicidal capability and desire, meaning they would both screen positive for suicidal ideation. Both pathways initially experience a comparable increase in capability, but Pathway B1 falls on the lower edge of the fold whereas Pathway B2 falls on the upper edge of the fold. As a result, Pathway B1’s course is diverted towards the lower fold, eventually ending in a lower risk state, whereas Pathway B2’s course remains on the upper fold, eventually ending with suicidal behavior. If assessed only at the start of their journeys, Pathway B1 would be classified as a false positive. Thus, single or infrequent assessment of suicidal ideation is clearly missing important information that may provide information about an individual’s dynamic pattern. The cusp catastrophe model thereby provides a conceptual frame for understanding that individuals who engage in suicidal behavior are often so similar to those who do not, and why most risk factors are only weakly correlated with suicidal behaviors (Chu et al., 2018; Franklin et al., 2017).

Figure 4.

Change in suicide risk states associated with two pairs of pathways. Within each pair, the pathways begin with comparable levels of suicidal desire and capability but end in very different locations (suicidal behavior versus not).

Summary and Conclusions

Although the nonlinear nature of suicide risk has been hypothesized for decades (e.g., Bryan & Rudd, 2016; Mishara, 1996; Rogers, 2003; Schiepek et al., 2011) and has even been explicitly articulated by the fluid vulnerability theory of suicide (Rudd, 2006), researchers have only recently started to employ methods able to capture this particular property of suicide risk. The results of these studies confirm that suicide risk fluctuates over time sometimes very rapidly and to a large degree. These findings support the conceptualization of suicidal behavior as an emergent phenomenon, such that very small differences or change in conditions can lead to very large differences in outcomes. The cusp catastrophe model provides one possible approach for understanding the temporal patterns that may signal the emergence of suicidal behavior. Increased focus on temporal change processes could serve as a foundation for these much-needed advances in suicide prevention.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (Award No. W81XWH-14-1-0272, PI: Bryan) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Award Nos. UL1TR002538 and KL2TR002539, PI: Rozek). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official positions or views of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Craig J. Bryan, National Center for Veterans Studies & The University of Utah

Jonathan E. Butner, The University of Utah

Alexis M. May, Wesleyan University

Kelsi F. Rugo, National Center for Veterans Studies & The University of Utah

Julia Harris, National Center for Veterans Studies & The University of Utah.

D. Nicolas Oakey, National Center for Veterans Studies & The University of Utah.

David C. Rozek, National Center for Veterans Studies & The University of Utah

AnnaBelle O. Bryan, National Center for Veterans Studies & The University of Utah

References

- Anestis MD, Pennings SM, & Williams TJ (2014). Preliminary results from an examination of episodic planning in suicidal behavior. Crisis, 35, 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Soberay KA, Gutierrez PM, Hernández TD, & Joiner TE (2014). Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 366–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, & Crowther JH (2008). A comparison of linear versus non-linear models of aversive self-awareness, dissociation, and non-suicidal self-injury among young adults. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 76(1), 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, Nugent NR, & Crowther JH (2012). An Exploratory Analysis of Situational Affect, Early Life Stress, and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in College Students. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 5(4), 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Littlefield AK, Conner KR, Schumacher JA, & Lee HJ (2014). Near-term predictors of the intensity of suicidal ideation: An examination of the 24 h prior to a recent suicide attempt. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, & Fonagy P (2009). Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 1355–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Haigh EA (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Walters EE, & Kessler RC (2000). Associations of substance use, abuse, and dependence with subsequent suicidal behavior. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151, 781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Steer RA, Henriques GR, & Beck AT (2005). The internal struggle between the wish to die and the wish to live: a risk factor for suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1977–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rozek DC (2018). Suicide prevention in the military: a mechanistic perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rudd MD (2016). The importance of temporal dynamics in the transition from suicidal thought to behavior. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rudd MD (2017). Nonlinear change processes during psychotherapy characterize patients who have made multiple suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Butner JE, Sinclair S, Bryan ABO, Hesse CM, & Rose AE (2017). Predictors of emerging suicide death among military personnel on social media networks. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Garland EL, & Rudd MD (2016). From impulse to action among military personnel hospitalized for suicide risk: Alcohol consumption and the reported transition from suicidal thought to behavior. General Hospital Psychiatry, 41, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rozek DC, Butner J, & Rudd MD (in press). Patterns of change in suicide ideation signal the recurrence of suicide attempts among high-risk psychiatric outpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Peterson AL, Young-McCaughan S, & Wertenberger EG (2016). The ebb and flow of the wish to live and the wish to die among suicidal military personnel. Journal of affective disorders, 202, 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Sinclair S, & Heron EA (2016). Do military personnel “acquire” the capability for suicide from combat? A test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Clinical Psychological Science, 4, 376–385. [Google Scholar]

- Butner JE, Gagnon KT, Geuss MN, Lessard DA, & Story TN (2015). Utilizing topology to generate and test theories of change. Psychological Methods, Available online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter G, Milner A, McGill K, Pirkis J, Kapur N, & Spittal MJ (2017). Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: systematic review and analysis of positive predictive values for risk scales. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, … & Michaels MS (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair S (1998). A cusp catastrophe model for adolescent alcohol use: An empirical test. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 2(3), 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Meldrum SC, Schuckit MA, Bucholz KK, Gamble SA, … & Kramer J (2007). Transitions to, and correlates of, suicidal ideation, plans, and unplanned and planned suicide attempts among 3,729 men and women with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Schuckit MA, Hirsch JK, Knox KL, Meldrum S, … & Soyka M (2006). Precontemplated and impulsive suicide attempts among individuals with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, … & Nock MK (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J (1999). Emergence as a construct. Emergence, 1, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hufford MR (2001). Alcohol and suicidal behavior. Clinical psychology review, 21(5), 797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger J, & Monk N (2014). Bioattractors: dynamical systems theory and the evolution of regulatory processes. The Journal of Physiology, 592, 2267–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon HJ, Lee JY, Lee YM, Hong JP, Won SH, Cho SJ, … & Cho MJ (2010). Unplanned versus planned suicide attempters, precipitants, methods, and an association with mental disorders in a Korea-based community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127, 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Perry DK, & Hesser JE (2010). Adolescent suicide and health risk behaviors: Rhode Island’s 2007 youth risk behavior survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T (2007). Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, & Walters EE (1999). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Huffman JC, & Nock MK (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of abnormal psychology, 126, 726–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED & May AM (2014). Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: A critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, & May AM (2015). The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, & Heard HL (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1060–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, …, & Lindenboim N (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, … & Murray-Gregory AM (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveys K, Crutchley P, Wyatt E, & Coppersmith G (2017). Small but mighty: Affective micropatterns for quantifying mental health from social media language In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology–-From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality (pp. 85–95). Stroudsburg, PA: Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh CM, Corderoy A, Ryan CJ, Hickie IB, Large MM (2019). Association between suicidal ideation and suicide: meta-analyses of odds ratios, sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value. BJPsych Open, 5 (2), e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, & Nock MK (2015). Single-item measurement of suicidal behaviors: validity and consequences of misclassification. PLOS One, 10 (10), e0141606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, & Nock MK (2017). Describing and measuring the pathway to suicide attempts: A preliminary study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47, 353–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara BL (1996). A dynamic developmental model of suicide. Human Development, 39, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe S, Simons A 1991. Diathesis—Stress Theories in the Context of Life Stress Research Implications for the Depressive Disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 110, 3: 406–425. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, … & Zaslavsky AM (2014). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC, & Kirtley OJ (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373, 20170268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmier-Claus JE, Taylor PJ, Gooding P, Dunn G, & Lewis SW (2011). Affective variability predicts suicidal ideation in individuals at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis: an experience sampling study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JR (2003). The anatomy of suicidology: A psychological science perspective on the status of suicide research. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, & Joiner TE (2019). Exploring the temporal dynamics of the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide constructs: a dynamic systems modeling approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87, 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Bryan CJ, Wertenberger E, Peterson AL, Young-McCaughon S, Mintz J, …, & Bruce TO (2015). Brief cognitive behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: results of a 2-year randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD (2006). Fluid vulnerability theory: A cognitive approach to understanding the process of acute and chronic risk In Ellis TE (Ed.), Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy (pp. 355–368). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Schiepek G, Fartacek C, Sturm J, Kralovec K, Fartacek R, & Plöderl M (2011). Nonlinear dynamics: theoretical perspectives and application to suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41, 661–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, & Ludman EJ (2013). Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatric Services, 64, 1195–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow MJ, & O’Carroll PW (2001). Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, …, & Crosby AE (2018). Vital Signs: trends in state suicide rates—United States, 1999–2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide—27 states, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 67, 617–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom R (1989). Structural Stability and Morphogenesis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Jain S, Raman R, Sun X, … & Hwang I (2015). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among new soldiers in the US Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Depression and Anxiety, 32, 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological review, 117, 575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Joiner TE Jr, & Schmidt NB (2005). Variability in suicidal ideation: a better predictor of suicide attempts than intensity or duration of ideation? Journal of Affective Disorders, 88, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Warren KL, Schatschneider C, & Schmidt NB (2006). Naturalistic evaluation of suicidal ideation: variability and relation to attempt status. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1029–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2018). Suicide Data. Retrieved July 29, 2018, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/

- Wyder M, & De Leo D (2007). Behind impulsive suicide attempts: Indications from a community study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 104, 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman EC (1976). Catastrophe theory. Scientific American, 65–83. [Google Scholar]