Abstract

Bioelectronic medicine is an evolving field in which new insights into the regulatory role of the nervous system and new developments in bioelectronic technology result in novel approaches in disease diagnosis and treatment. Studies on the immunoregulatory function of the vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex have a specific place in bioelectronic medicine. These studies recently led to clinical trials with bioelectronic vagus nerve stimulation in inflammatory diseases and other conditions. Here, we outline key findings from this preclinical and clinical research. We also point to other aspects and pillars of interdisciplinary research and technological developments in bioelectronic medicine.

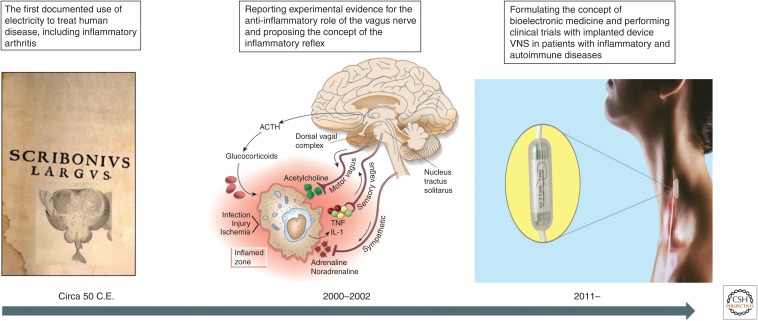

Neuronal electrical activity is fundamental for brain function and for the rapid transfer of information via peripheral nerves in reflex circuits regulating a myriad of physiological processes. Although neural electrical signaling is vital for maintaining homeostasis, disbalance, or failure of neural regulation is associated with many disorders. There is a long history of exploring electricity using devices to treat human disease. Arguably, the first documented approach is associated with Scribonius Largus, the court physician of the Roman emperor Claudius, circa 50 C.E. Scribonius used “a natural device”—a live torpedo fish to treat gout, a form of inflammatory arthritis (Fig. 1). Arthritis, and more specifically, rheumatoid arthritis, is a debilitating disease whose etiology includes dysregulated immune responses, leading to chronic inflammation (Firestein 2003). Fast-forwarding from Scribonius's time to 2016 reveals that we again explore treating arthritis with electricity; however, this time, using a bioelectronic device attached to a major peripheral nerve—the vagus nerve (Koopman et al. 2016). What led to this novel approach was triggered by the recent discovery that the vagus nerve regulates inflammation within a physiological mechanism—the inflammatory reflex (Fig. 1; Borovikova et al. 2000; Tracey 2002). The implications of this discovery were multidimensional. It jumpstarted research on the role of the nervous system as a key partner of the immune system in the regulation of inflammation, and led to identifying molecular constituents of the neuroimmune dialogue (Wang et al. 2003; Pavlov et al. 2006, 2018; Chavan et al. 2017; Pavlov and Tracey 2017). It also triggered a considerable interest in exploring vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and other approaches focused on the inflammatory reflex to counteract aberrant inflammation critically implicated in pathogenesis of many diseases (Pavlov and Tracey 2012). The translational impact of this research was recently validated in clinical trials exploring bioelectronic modulation of the vagus nerve in treating patients with chronic inflammatory diseases (Bonaz et al. 2016; Koopman et al. 2016). These studies ultimately led to conceptually new developments in disease management and treatment under the umbrella of bioelectronic medicine (Fig. 1; Tracey 2014; Olofsson and Tracey 2017; Pavlov and Tracey 2019). Here, we outline key aspects of the studies stemming from the discovery of the immunomodulatory function of the vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex and leading to current clinical translation in bioelectronic medicine. We also briefly summarize other developments in this evolving field, in which novel mechanistic insight and technological innovation in bioelectronics result in new therapeutic approaches.

Figure 1.

From Scribonius to the inflammatory reflex and bioelectronic medicine. The long evolution of using electricity for therapeutic benefit allegedly starting with Scribonius recently culminated in designing revolutionary approaches of electrical neuromodulation in the field of bioelectronic medicine. The recent realization that the vagus nerve plays a role in controlling inflammation within the inflammatory reflex was key in using and developing implanted device-generated vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) in the first clinical trials in patients with inflammatory diseases. Left panel is the compilation of an engraving of a torpedo fish embedded in the foreground of a page from Scribonius Largus 1655 (wellcomecollection.org/works/dwu4cdy6). (Torpedo fish image reprinted from John Hunter's paper to the Royal Society Royal College of Surgeons of England and reprinted courtesy of the public domain; page from Scribonius Largus 1655, provided by the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek and available for reprint because it is in the public domain. Middle panel is reprinted from Tracey 2002, with permission, from the author. Right panel reprinted from noosphereventures.com/bioelectronics-the-next-level-of-leveraging-the-body-s-potential-and-treating-diseases, with permission, from Noosphere Venture Partners LP 2018.)

THE VAGUS NERVE FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

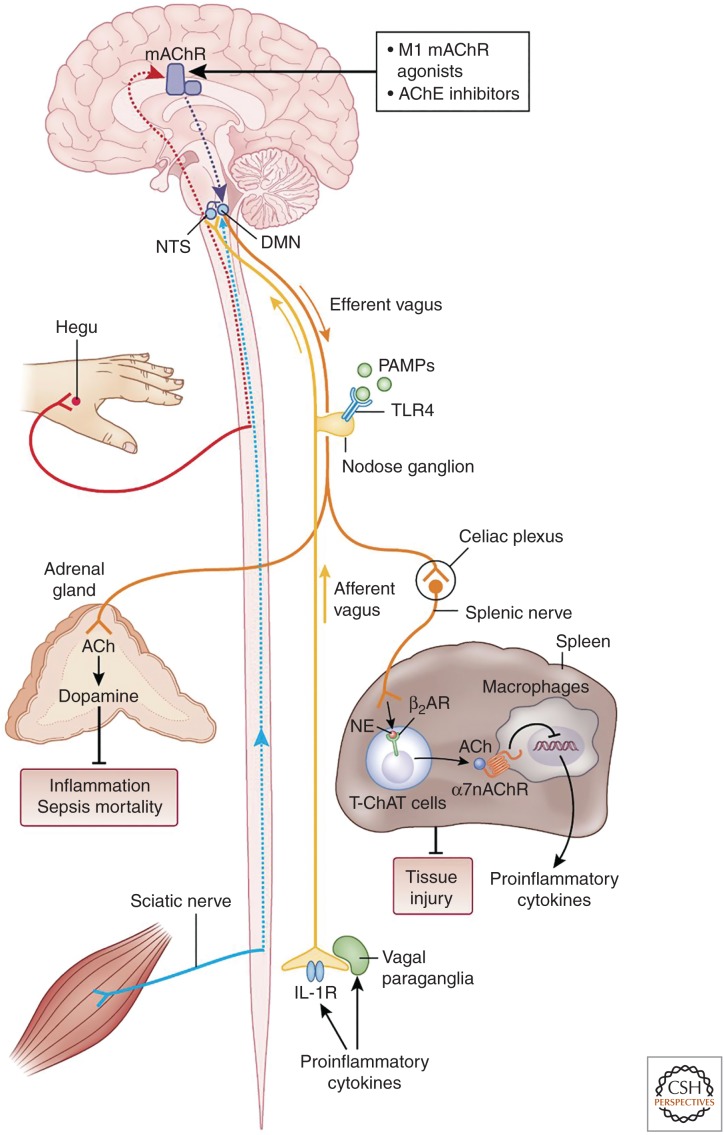

Relevant aspects of the anatomy and physiology of the vagus nerve (cranial nerve ten) have been previously reviewed in detail (see Berthoud and Neuhuber 2000; Berthoud 2004, 2008; Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Metz and Pavlov 2018) and a brief overview is provided below. The vagus nerve is a mixed nerve containing afferent and efferent fibers (Fig. 2). Efferent neurons within the vagus nerve originate in the dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) of the vagus and nucleus ambiguus (NA) in the brainstem medulla oblongata and innervate several visceral organs (Fig. 2; Berthoud 2008; Metz and Pavlov 2018). These long preganlionic neurons communicate with postganlionic neurons in close proximity or within the innervated organs. Main physiological functions of the vagus nerve are related to regulation of heart rate, gastrointestinal motility and secretion, glucose production in the liver, and pancreatic endocrine and exocrine secretion (Berthoud and Neuhuber 2000; Berthoud 2008; Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Masi et al. 2018). These functions are primarily mediated by the release of acetylcholine (ACh) interacting with muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) on target cells, including smooth muscle cells, cardiac myocytes, and glandular cells. The vagus nerve also contains afferent neurons, constituting ∼80% of the total neuronal count (Berthoud and Neuhuber 2000). The cell bodies of these pseudounipolar neurons are localized outside of the central nervous system (CNS)—in the nodose and jugular ganglia, and their bidirectional axons communicate peripheral (visceral) alterations to the brainstem nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) (Fig. 2; Berthoud and Neuhuber 2000).

Figure 2.

The inflammatory reflex. In the inflammatory reflex, the activity of afferent vagus nerve fibers residing in the nodose ganglion is stimulated by cytokines and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The signal is transmitted to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). Reciprocal connections between the NTS and dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) of the vagus mediate communication with and activation of efferent vagus nerve fibers from the DMN. The signal is propagated to the celiac ganglia and the superior mesenteric ganglion in the celiac plexus, where the splenic nerve originates. Norepinephrine (NE) released from the splenic nerve interacts with β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs) and causes the release of acetylcholine (ACh) from T cells containing functional choline acetyltransferase (T-ChAT) cells. ACh interacts with α7 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChRs) on macrophages and suppresses proinflammatory cytokine release and inflammation. The inflammatory reflex can be activated through brain muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR)-mediated mechanisms by centrally acting M1 mAChR agonists and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors. Somatosensory activation by electroacupuncture at the Hegu point also causes activation of brain mAChR signaling, which then results in activation of efferent vagus and splenic anti-inflammatory signaling. Electroacupuncture at a different acupuncture point activates sciatic nerve signals, which by unknown mechanisms convert to efferent vagus nerve signaling to the adrenal medulla, resulting in dopamine release. Dopamine suppresses inflammation and improves survival in a model of sepsis. Vagus nerve and splenic nerve signaling mediated through α7nAChR on splenocytes controls inflammation in acute kidney injury and alleviates the condition. (Figure created by Debbie Maizels, Springer Nature, for Pavlov and Tracey 2017; reprinted, with permission, from the authors in conjunction with Springer Nature.)

THE ROLE OF THE VAGUS NERVE IN THE NEURAL REGULATION OF IMMUNITY AND INFLAMMATION

Recently, our knowledge about the physiological functions of the vagus nerve was considerably advanced when this nerve was characterized as a major regulator of inflammation (Borovikova et al. 2000; Tracey 2002, 2009). Inflammation is a vital protective event against tissue injury and infection. Key elements in the initial innate immune response during inflammation include interaction of pathogen fragments and tissue injury molecules with the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and other molecular sensors on immune cells (Akira et al. 2006; Medzhitov 2008). This interaction triggers activation of NF-κB-mediated and other intracellular signaling pathways that result in the generation of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 (Tracey 2002; Medzhitov 2008; Olofsson et al. 2017). The release of these pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, additional leucocyte recruitment in the inflamed area, angiogenesis, and the release of resolvins and other molecules mediate a complex and balanced inflammatory process, which is resolved in a timely manner (Medzhitov 2008; Chavan et al. 2017; Chavan and Tracey 2017; Olofsson et al. 2017; Serhan and Levy 2018). However, dysregulation of the mechanisms underlying this normal and beneficial course of inflammation results in excessive or unresolved chronic inflammation that can be deleterious and lethal (Medzhitov 2008; Pavlov et al. 2018). Unbalanced and unresolved inflammation mediates pathogenesis in sepsis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and many other disorders (Andersson and Tracey 2012; Talbot et al. 2016). Inflammation also is a characteristic pathogenic feature of obesity, the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cancer, affecting millions of people worldwide (Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Pavlov et al. 2018). Therefore, improved understanding of the mechanisms regulating inflammation is a prerequisite for developing efficient approaches to diagnose, prevent, and treat a wide range of diseases.

It is increasingly recognized that the brain and the nervous system are involved in the regulation of inflammation (Pavlov et al. 2018). Until not so long ago, this regulation was solely attributed to the sympathetic part of the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Elenkov et al. 2000; Webster et al. 2002; Pavlov et al. 2003; Olofsson et al. 2017). A substantial advance was recently generated by the discovery that the efferent vagus nerve plays a major role in the neuroimmune dialogue and neural control of immune function and inflammation (Borovikova et al. 2000). Vagotomy (a surgical interruption of the vagus nerve) results in higher circulating TNF levels in rats administered with endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) and electrical stimulation of the peripheral portion of the vagus nerve in the neck decreases these levels (Borovikova et al. 2000). In addition, in vitro treatment of immune cells with ACh—the main molecule released from efferent vagus nerve axons, decreases LPS-induced TNF production (Borovikova et al. 2000). This new immunomodulatory function of the efferent vagus nerve was termed the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (Borovikova et al. 2000; Pavlov et al. 2003). These findings and previous observations, showing the role of the afferent vagus nerve fibers in transmitting peripheral inflammatory signals to the brain, led to proposing the concept of the inflammatory reflex (Fig. 2; Tracey 2002). A growing body of experimental evidence shows that this physiological, vagus nerve-based mechanism is well positioned to communicate alterations in peripheral immune homeostasis to the brain and control peripheral immune responses and inflammation (Pavlov et al. 2018). A receptor, responsible for transmitting vagus nerve cholinergic anti-inflammatory outflow into suppression of proinflammatory cytokine production was also identified—the α7 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) expressed on macrophages and other immune cells (Wang et al. 2003). This finding provided a rationale for studying the anti-inflammatory properties of GTS-21, choline and many other α7nAChR agonists in preclinical setting of numerous inflammatory conditions (Pavlov et al. 2007; Parrish et al. 2008; Pavlov and Tracey 2015). Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation, activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, and inhibition of the inflammasome activation were identified as intracellular events with a mediating role in cholinergic anti-inflammatory signaling in different inflammatory conditions (Guarini et al. 2003; de Jonge et al. 2005; Lu et al. 2014).

A considerable insight into the inflammatory reflex was provided by revealing the interaction between the vagus nerve and the splenic nerve (Berthoud and Powley 1996) in the regulation of inflammation (Rosas-Ballina et al. 2011). This was first indicated by showing that the suppression of serum and splenic TNF as a result of VNS in murine endotoxemia is abrogated by splenic nerve transection (Rosas-Ballina et al. 2008). VNS also activates the release of ACh in the spleen (Rosas-Ballina et al. 2011). A major cellular source of this ACh is a subset of T lymphocytes, containing choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)—the key enzyme in ACh biosynthesis (Rosas-Ballina et al. 2011). These T cells containing functional choline acetyltransferase (T-ChAT) cells also express β-adrenergic receptors, mediating catecholaminergic activation of ACh release under vagus nerve control (Fig. 2). ACh further interacts with the α7nAChR on macrophages and other immune cells to suppress proinflammatory cytokine production (Fig. 2). In addition to endotoxemia, a functional cooperation between the vagus nerve (classically designated as parasympathetic) and the splenic nerve (sympathetic) has been described in murine colitis (Ji et al. 2014; Munyaka et al. 2014), B-cell responses to blood-borne antigen (Mina-Osorio et al. 2012), T-cell activation and egress from the spleen, and control of hypertension (Carnevale et al. 2016), renal ischemia–reperfusion injury (Inoue et al. 2016), and other conditions. These studies suggested that the convenient and widely used designation “parasympathetic” versus “sympathetic” in describing the functional role of autonomic neurons as acting in an opposite manner is imprecise (Pavlov and Tracey 2017). In addition, new functional roles for peripheral afferents (somatosensory) and efferent neurons in immunomodulation and their contribution to the inflammatory reflex have been reported (Fig. 2). Hence, active ongoing characterization of peripheral nerves and even neuronal populations within one nerve, based on specific functions should provide a basis for more precise classifications (Chang et al. 2015; Pavlov and Tracey 2017; Han et al. 2018).

A ROLE FOR VAGUS AFFERENTS IN THE NEUROIMMUNE DIALOGUE

Vagus nerve and other afferent (sensory) neurons innervating peripheral tissues respond to inflammatory products and send signals to the CNS (Fig. 2; Chavan et al. 2017). Peripheral terminals of sensory neurons activated during pathogen invasion also release substance P and other neuropeptides (Chiu et al. 2013; Talbot et al. 2015). These molecules modulate inflammation by interacting with immune cells within a feedback loop—an axon reflex (Chiu et al. 2013; Talbot et al. 2015; Chavan and Tracey 2017; Pavlov and Tracey 2017; Baral et al. 2018). The role of sensory vagus nerve fibers in detecting alterations in the immune homeostasis and communicating this information to the brain (Fig. 2) has also been an area of active research (Niijima 1996; Goehler et al. 2000; Chavan et al. 2017; Pavlov et al. 2018). The interplay between inflammatory mediators and sensory vagus nerve fibers was first suggested by showing that subdiaphragmatic vagotomy inhibited febrile responses induced by intraportal administration of IL-1β or LPS (Goehler et al. 2000). This and other findings have indicated that afferent signaling along the vagus nerve is required to initiate a hyperthermic response to peripheral inflammatory mediators (Goehler et al. 2000). In addition, intraportal administration of IL-1β results in increased activity of the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve and increased efferent activity of the splenic nerve (Niijima 1996). Hepatic vagotomy ablates activation of splenic nerve activity (Niijima 1996)—an observation pointing to the reflex nature of this effect with relevance to our current understanding of the inflammatory reflex (Pavlov et al. 2018). Recent studies added to these early observations by providing insight into the specificity of vagus nerve signaling activated in the presence of inflammatory mediators. Electrophysiological recordings and comprehensive decoding of neural activity identified LPS and cytokine-specific sensory neural signals in the vagus nerve (Steinberg et al. 2016; Silverman et al. 2018; Zanos et al. 2018). Systemic administration of LPS activates sensory vagus nerve signals in TLR4-receptor-dependent manner (Silverman et al. 2018). Intraperitoneal administration of IL-1β or TNF results in a dose-dependent increase in afferent vagus nerve activity (Steinberg et al. 2016). Decoding the neural signals based on their shape and amplitude identifies sensory neural groups responding specifically to TNF and IL-1β (Steinberg et al. 2016; Zanos et al. 2018). Vagotomy performed distal to the recording electrode abolishes these neural signals indicating that the majority of the activity recorded are sensory vagus nerve signals (Steinberg et al. 2016). These characteristic electrical patterns are absent in animals lacking the respective cytokine receptor (Steinberg et al. 2016; Zanos et al. 2018). This research has generated considerable insights, which may be of interest for developing advanced approaches in disease diagnosis and treatment within the scope of bioelectronic medicine.

BRAIN SIGNALING IN THE REGULATION OF THE INFLAMMATORY REFLEX AND IN CONTROLLING INFLAMMATION

Reporting the direct evidence for the anti-inflammatory role of the vagus nerve was closely related to studies with the anti-inflammatory compound CNI-1493 (guanylhydrazone). CNI-1493 administered in the brain was found to suppress peripheral cytokine levels and the vagus nerve was identified as a major brain-to-periphery conduit of CNI-1493 anti-inflammatory effects (Bernik et al. 2002). Intriguingly, CNI-1493 was also identified as a ligand of mAChRs (Pavlov et al. 2006). Consequently, a role for brain cholinergic signaling and brain mAChRs in the neural regulation of peripheral inflammation through a vagus nerve–mediated mechanism was shown (Fig. 2; Pavlov et al. 2006, 2009; Ji et al. 2014; Munyaka et al. 2014; Rosas-Ballina et al. 2015). These findings also indicated new possibilities to intervene in inflammatory conditions for therapeutic benefit using two types of centrally acting cholinergic compounds—mAChR ligands and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors (Pavlov et al. 2006, 2009; Waldburger et al. 2008; Munyaka et al. 2014; Hanes et al. 2015; Rosas-Ballina et al. 2015). Especially appealing, in terms of clinical development, is the use of AChE inhibitors, because some of these compounds, including galantamine are clinically approved drugs (for Alzheimer's disease). Immune dysregulation and chronic low-grade inflammation are characteristic features of obesity and obesity-driven conditions, including the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Roth et al. 2016). Galantamine treatment was shown to significantly alleviate inflammation, insulin resistance, and other metabolic derangements in a murine model of high-fat, diet-induced obesity (Satapathy et al. 2011). Preclinical research was recently followed by clinical studies. A randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind trial showed the anti-inflammatory and beneficial metabolic effects of clinically approved galantamine doses in patients with the metabolic syndrome (Consolim-Colombo et al. 2017).

The CNS integration of afferent and efferent neural immunomodulatory circuitries and their brain regulation are also of substantial research interest. Interactions between NTS, DMN, and area postrema within the dorsal vagal complex mediate integration of afferent (sensory) and efferent (motor) vagus nerve signaling and humoral factors at the level of the brainstem (Rogers et al. 1996; Pavlov and Tracey 2012). After reaching the brainstem NTS, afferent signals along the vagus nerve are directed to other brain areas, including the hypothalamus, the basal forebrain, hippocampus, and other constituents of the limbic system (Grijalva and Novin 1990; Rogers et al. 1996; Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Suarez et al. 2018). It has also been known for a long time that hypothalamic nuclei and regions in the forebrain and the limbic system also control efferent vagus nerve outflow (Akert and Gernandt 1962; Rogers et al. 1996). These observations suggest another “higher” level of integration and regulation of vagus nerve signaling. Detailed mapping of brain networks with a role in the regulation of vagus nerve anti-inflammatory activity and the inflammatory reflex and their alterations in disease settings would indicate new neural therapeutic targets (Pavlov et al. 2018). Several approaches of device-generated brain neuromodulation, including electrical deep brain stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation, are in clinical use or have been experimentally studied for treating neurological conditions (Fregni and Pascual-Leone 2007; Cabrera et al. 2014; Salehpour et al. 2018). One day, it may be possible to use these approaches to modulate brain networks for therapeutic benefit in inflammatory diseases within the scope of bioelectronic medicine.

VAGUS NERVE STIMULATION IN ANIMAL MODELS OF INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Numerous studies using VNS have provided mechanistic insight into the anti-inflammatory role of the vagus nerve and indicated new therapeutic options for inflammatory conditions (Pavlov and Tracey 2015; Chavan et al. 2017). Most of these studies have used cervical VNS, which activates both efferent and afferent signaling. The role of efferent vagus nerve signaling in controlling proinflammatory cytokine release, inflammation, and cardiovascular and metabolic indices has been unequivocally shown (Borovikova et al. 2000; Inoue et al. 2016; Hong et al. 2018b). In addition, activation of afferent vagus nerve signaling has been shown to cause peripheral anti-inflammatory effects (Olofsson et al. 2015; Inoue et al. 2016). This observation suggests that activation of afferent vagus nerve signaling triggers brain regulatory networks resulting in peripheral anti-inflammatory output (Pavlov and Tracey 2017). Revealing the brain mechanisms of this regulation presents an interesting area for future research. The anti-inflammatory and disease-alleviating efficacy of VNS has been indicated in acute settings of murine endotoxemia, sepsis, hemorrhagic shock, uncontrolled bleeding, postoperative ileus, kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury, and other conditions (Borovikova et al. 2000; Guarini et al. 2003; de Jonge et al. 2005; Inoue et al. 2016; Hong et al. 2018b). The use of implanted devices for bioelectronic VNS has allowed studying the efficacy of this approach in chronic settings of inflammatory conditions. For instance, once daily VNS delivered via implanted cuff electrode for 7 days significantly alleviates inflammation and other pathological features of collagen-induced arthritis in rats (Levine et al. 2014). The use of a similar approach—3 hours of VNS stimulation per day through an implanted device for 5 days—significantly attenuates colonic inflammation and the severity of IBD (colitis) in rats (Meregnani et al. 2011). Another, minimally invasive approach of VNS has recently been used in treating adverse inflammation. Stimulating the cervical vagus nerve using a percutaneous needle electrode placed under ultrasound guidance results in significant alleviation of peripheral and CNS inflammation (neuroinflammation) in mice with endotoxemia (Huffman et al. 2019). Approaches for noninvasive VNS in controlling inflammation have also been explored. One of these approaches is stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. This afferent branch of the vagus nerve innervates the ear canal and a specific area of the ear, termed “cymba concha,” and terminates in the NTS. Although several studies have shown the anti-inflammatory efficacy of this transcutaneous form of VNS in animal studies, there have been some unaddressed questions and uncertainty in terms of the mechanisms mediating these effects. One key question has been whether activation of neural signaling through this sensory branch translates into efferent vagus nerve signaling that regulates immune responses and inflammation. A very recent study exploring this approach in mice with postoperative ileus (a common complication after abdominal surgery) and endotoxemia provided substantial mechanistic insight addressing this question (Hong et al. 2018b). Electrical transcutaneous auricular VNS in these mice suppresses intestinal cytokine expression, lowers leukocyte recruitment to the manipulated intestine segment, and improves gastrointestinal transit after intestinal manipulation (Hong et al. 2018b). In addition, this form of VNS suppresses TNF and IL-6 levels in mice with endotoxemia (Hong et al. 2018b). Auricular VNS triggers neuronal activation in the NTS and DMN, and vagotomy abrogates its anti-inflammatory effects; these observations clearly point to the mediating role of efferent vagus nerve signaling in the context of murine ileus and endotoxemia (Hong et al. 2018b). Recent studies have also shown the efficacy of other approaches of noninvasive VNS in alleviating CNS inflammation (neuroinflammation) and other brain derangements in mice by affective microglial activation toward neuroprotective phenotype (Kaczmarczyk et al. 2017; Zhao et al. 2019). For instance, noninvasive transcutaneous stimulation of the right cervical vagus nerve was recently used in a mouse model of focal cerebral ischemia (Zhao et al. 2019). The efficacy of a regimen of VNS for 60 min (six series of 2-min duration substimulations at a 10-min interval, consisting of 1 msec duration pulses of 5 kHz sinewaves, repeated at 25 Hz with an average voltage of 15 V) was studied. This VNS (vs. sham stimulation applied on left femur) results in considerable neuroprotection related to increased microglial M2 polarization mediated by IL-17A expression (Zhao et al. 2019).

In addition to its implications in immunoregulation and inflammatory control, the efficacy of VNS has been shown in the regulation of bleeding (hemorrhage) (Czura et al. 2010) and body weight (Pelot and Grill 2018; Yao et al. 2018). VNS in pigs subjected to ear resection was shown to significantly shorten the bleeding time and to potentiate formation of thrombin/antithrombin III complexes (Czura et al. 2010). Although the mechanisms of these VNS antihemorrhagic effects remain to be further elucidated, these observations suggest the potential of VNS as an experimental approach in treating a variety of trauma- and hemorrhage-related conditions. The vagus nerve, and specifically its afferent fibers regulate satiety and thus food intake (Berthoud and Neuhuber 2000). A very recent study showed the usage of a “smart” device for VNS in reducing body weight (Yao et al. 2018). This battery-free device was designed to generate biphasic electrical pulses stimulating afferent vagus nerve fibers in response to stomach peristalsis (Yao et al. 2018). The use of this device in rats results in a remarkable 38% weight loss maintained within the 100-day study period (Yao et al. 2018). This targeted VNS may have considerable future implications in therapeutic strategies aimed at achieving weight loss in individuals with obesity.

Using modern methodology, based on advances in molecular genetics, allows further in-depth functional characterization of the role of vagus nerve and other neural circuitries in immune regulation (Pavlov and Tracey 2017; Pavlov et al. 2018). In parallel, accumulating evidence about the efficacy of VNS in animal models of disorders characterized by immune and metabolic derangements has resulted in testing implanted device-generated bioelectronic VNS in patients with inflammatory and autoimmune disease (Bonaz et al. 2016; Koopman et al. 2016).

VAGUS NERVE STIMULATION IN THE TREATMENT OF HUMAN INFLAMMATORY AND AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES

In many diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, aberrant inflammation coexists with decreased vagus nerve activity determined by heart rate variability analysis (Lindgren et al. 1993; Carnethon et al. 2003; Pavlov and Tracey 2012). Although a causal relationship has not been clearly established, augmenting the diminished vagal tone by VNS in these disorders has been documented as an efficient approach to decrease inflammation and alleviate the disease severity (Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Bonaz 2018).

Results from clinical trials of bioelectronic VNS in patients with IBD (Crohn's disease) and rheumatoid arthritis started validating the translational applicability of preclinical findings. Crohn's disease is a chronic inflammatory disease with limited, expensive, and associated with considerable adverse effect treatment options. A relatively recent study showed that VNS using an implanted device significantly alleviated the severity of the disease manifested by reduced disease activity index and improved endoscopic findings in five of seven patients with active disease (Bonaz et al. 2016). In parallel, VNS results in increased vagus nerve activity determined by heart rate variability analysis (Bonaz et al. 2016). Another debilitating chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorder with expensive treatment options and a high number of nonresponders is rheumatoid arthritis (Firestein 2003). Bioelectronic VNS (up to four times daily) through an implanted device in patients with this disease resulted in considerable disease alleviation indicated by significantly improved disease scores for up to 84 days (Koopman et al. 2016). This VNS treatment is efficient in two cohorts of patients—seven patients in an early disease stage—who showed no response to previous methotrexate treatment and 10 patients in later disease stages who failed treatments with several biologics (Koopman et al. 2016). These effects are tightly associated with the neurostimulation effect; interruption (withdrawal) of the VNS treatment results in worsening of the disease score and restoring VNS—in consequent improvement (Koopman et al. 2016). The clinical improvement in these patients with rheumatoid arthritis following VNS occurs in parallel with decreases in TNF and other cytokine levels (Koopman et al. 2016).

The anti-inflammatory efficacy of transcutaneous stimulation of the cervical vagus nerve has also been successfully explored in healthy volunteers (Lerman et al. 2016) and more recently in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome (Tarn et al. 2018). The potential use of auricular VNS in the treatment of postoperative ileus was also recently suggested by showing that auricular VNS in humans activates efferent vagus nerve signaling to the viscera (Hong et al. 2018a). Transcutaneous auricular VNS results in significant suppression of action potential frequency and significant increase of action potential amplitude (analyzed by a free running electromyography [EMG]) in the stomach of 14 patients requiring open laparotomy. Transcutaneous VNS also increases gastrin levels (a surrogate marker for vagus nerve activation) in these patients 3 hours following stimulation (Hong et al. 2018a). Of note, no significant device-related adverse events are reported in these patients. These findings and the recently shown therapeutic efficacy of transcutaneous VNS in mice with ileus (Hong et al. 2018b) suggest that this noninvasive VNS approach can be further explored in the treatment of human postoperative ileus (Hong et al. 2018a).

BIOELECTRONIC MEDICINE: AN EXPANDING FIELD

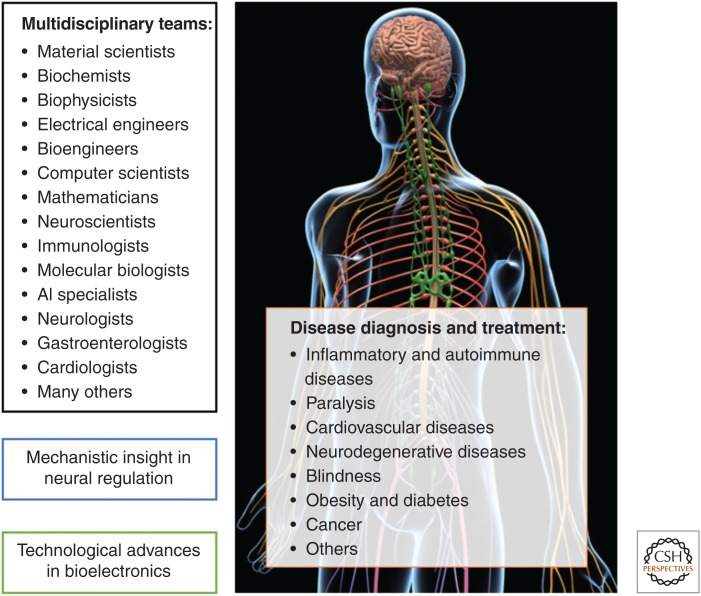

VNS holds the potential of providing efficient means of treating a broad spectrum of human conditions, including IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, ileus, uncontrolled bleeding, and the modern pandemics—obesity and the closely related metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (Pavlov and Tracey 2012; Yao et al. 2018). Continuing preclinical and clinical studies providing new insight into the role of the vagus nerve in the regulation of inflammation and the therapeutic efficacy of VNS, described above, represent a pillar of translational advances in bioelectronic medicine. In addition to the vagus nerve, studies on the regulatory role of other peripheral and CNS circuitries and the therapeutic usage of their modulation are considerably adding to progress in bioelectronic medicine (Fig. 3; Talbot et al. 2015; Guduru et al. 2018; Güemes and Georgiou 2018; Jiman et al. 2018; Kibleur and David 2018; Kovatchev 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Pavlov and Tracey 2019). These studies use methodological advances in material science, bioengineering, neuroscience, data analytics, computer modeling and mathematics, immunology, molecular biology, and other disciplines (Fig. 3; Bettinger 2018; Giagka and Serdijn 2018; Guduru et al. 2018; Kovatchev 2018; Qing et al. 2018; Sanjuan-Alberte et al. 2018; Silverman et al. 2018; Pavlov and Tracey 2019). Applying multidisciplinary approaches has been instrumental in discovering new molecular mechanisms of CNS and peripheral neural regulation, and identifying new therapeutic targets (Fig. 3). These insights and advancing bioelectronic technology have led to clinical exploration of novel treatments of cardiovascular disease, paralysis, diabetes, blindness, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and many other diseases and conditions (Fig. 3; Merabet et al. 2005; Fregni and Pascual-Leone 2007; De Ferrari et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2015, 2018; Bouton et al. 2016; Mishra et al. 2016; Olofsson and Tracey 2017; Angeli et al. 2018; Fernandez 2018; Kovatchev 2018; Salehpour et al. 2018; Sanjuan-Alberte et al. 2018). Successful team efforts of basic researchers and clinical scientists, including neurologists, gastroenterologists, cardiologists, and other colleagues will continue to be a driving force for broadening the scope of the field and novel clinical exploration (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Current aspects and constituents of bioelectronic medicine. Bioelectronic medicine is a growing and evolving field. It brings together colleagues with diverse specializations in basic research and clinical disciplines. Ongoing research efforts by these multidisciplinary teams provide new mechanistic insight into the regulatory functions of the nervous system and their deviations in disease settings, identify new molecular targets, and evaluate new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches with relevance to neuromodulation. In parallel, advances in biomaterials, electrodes, sensors, interfaces, bioelectronic devices, and artificial intelligence elements substantially facilitate the implementation of bioelectronic approaches in disease settings. Although many of these approaches are based on targeting neural circuits, others, such as the “artificial pancreas” are not strictly related to neuromodulation. All of these efforts culminate in new clinical trials in many diseases under the umbrella of bioelectronic medicine. (Background figure from MotionCow 2018; reprinted, with permission, from TurboSquid.com.)

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Active ongoing research has provided mechanistic insights into the role of the vagus nerve in the neuroimmune communication and in controlling inflammation within the inflammatory reflex. These studies also indicated that targeting the inflammatory reflex using VNS can be an efficient new approach to control aberrant inflammation in a broad range of diseases. Preclinical studies provided a rationale for successful clinical translation in recently completed and ongoing clinical trials exploring bioelectronic neuromodulation in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and IBD. These studies were of fundamental importance for the field of bioelectronic medicine. Improved understanding of the nervous system regulatory functions and their alterations in preclinical disease models will continue to provide necessary mechanistic insights for further clinical trials. Moving forward, the symbiotic relationship between preclinical and clinical studies and technological innovations will be essential for achieving a key factor for novel clinical translation (Fig. 3). The future use of closed-loop devices and systems, machine learning, and elements of artificial intelligence will improve disease diagnosis, allow precise predictions of major medical events, and result in improved treatments. Arguably, bioelectronic medicine is at the forefront of the technological revolution in science and medicine and holds the promise of transforming medicine.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT

V.A.P., S.S.C., and K.J.T. are inventors on patents broadly related to the topic of this review and have assigned their rights to the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants NIH-NIGMS: R01GM128008 to V.A.P., 1R35GM118182-01 to K.J.T., and NIH-NIAID 1P01AI102852-01A1 to K.J.T. and S.S.C.

Footnotes

Editors: Valentin A. Pavlov and Kevin J. Tracey

Additional Perspectives on Bioelectronic Medicine available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Akert K, Gernandt BE. 1962. Neurophysiological study of vestibular and limbic influences upon vagal outflow. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 14: 904–914. 10.1016/0013-4694(62)90141-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124: 783–801. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson U, Tracey KJ. 2012. Reflex principles of immunological homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 313–335. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeli CA, Boakye M, Morton RA, Vogt J, Benton K, Chen Y, Ferreira CK, Harkema SJ. 2018. Recovery of over-ground walking after chronic motor complete spinal cord injury. N Engl J Med 379: 1244–1250. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral P, Umans BD, Li L, Wallrapp A, Bist M, Kirschbaum T, Wei Y, Zhou Y, Kuchroo VK, Burkett PR, et al. 2018. Nociceptor sensory neurons suppress neutrophil and γδ T cell responses in bacterial lung infections and lethal pneumonia. Nat Med 24: 417–426. 10.1038/nm.4501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernik TR, Friedman SG, Ochani M, DiRaimo R, Ulloa L, Yang H, Sudan S, Czura CJ, Ivanova SM, Tracey KJ. 2002. Pharmacological stimulation of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J Exp Med 195: 781–788. 10.1084/jem.20011714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR. 2004. Anatomy and function of sensory hepatic nerves. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 280: 827–835. 10.1002/ar.a.20088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR. 2008. The vagus nerve, food intake and obesity. Regul Pept 149: 15–25. 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Neuhuber WL. 2000. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton Neurosci 85: 1–17. 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Powley TL. 1996. Interaction between parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves in prevertebral ganglia: Morphological evidence for vagal efferent innervation of ganglion cells in the rat. Microsc Res Tech 35: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger CJ. 2018. Recent advances in materials and flexible electronics for peripheral nerve interfaces. Bioelectron Med 4: 6 10.1186/s42234-018-0007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaz B. 2018. Is there a place for vagus nerve stimulation in inflammatory bowel diseases? Bioelectron Med 4: 4 10.1186/s42234-018-0004-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Hoffmann D, Clarençon D, Mathieu N, Dantzer C, Vercueil L, Picq C, Trocmé C, Faure P, et al. 2016. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation in Crohn's disease: A 6-month follow-up pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 28: 948–953. 10.1111/nmo.12792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ. 2000. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature 405: 458–462. 10.1038/35013070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton CE, Shaikhouni A, Annetta NV, Bockbrader MA, Friedenberg DA, Nielson DM, Sharma G, Sederberg PB, Glenn BC, Mysiw WJ, et al. 2016. Restoring cortical control of functional movement in a human with quadriplegia. Nature 533: 247–250. 10.1038/nature17435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera LY, Evans EL, Hamilton RH. 2014. Ethics of the electrified mind: Defining issues and perspectives on the principled use of brain stimulation in medical research and clinical care. Brain Topogr 27: 33–45. 10.1007/s10548-013-0296-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnethon MR, Jacobs DR Jr, Sidney S, Liu K. 2003. Influence of autonomic nervous system dysfunction on the development of type 2 diabetes: The CARDIA study. Diabetes Care 26: 3035–3041. 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale D, Perrotta M, Pallante F, Fardella V, Iacobucci R, Fardella S, Carnevale L, Carnevale R, De Lucia M, Cifelli G, et al. 2016. A cholinergic-sympathetic pathway primes immunity in hypertension and mediates brain-to-spleen communication. Nat Commun 7: 13035 10.1038/ncomms13035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RB, Strochlic DE, Williams EK, Umans BD, Liberles SD. 2015. Vagal sensory neuron subtypes that differentially control breathing. Cell 161: 622–633. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan SS, Tracey KJ. 2017. Essential neuroscience in immunology. J Immunol 198: 3389–3397. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan SS, Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. 2017. Mechanisms and therapeutic relevance of neuro-immune communication. Immunity 46: 927–942. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu IM, Heesters BA, Ghasemlou N, Von Hehn CA, Zhao F, Tran J, Wainger B, Strominger A, Muralidharan S, Horswill AR, et al. 2013. Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature 501: 52–57. 10.1038/nature12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolim-Colombo FM, Sangaleti CT, Costa FO, Morais TL, Lopes HF, Motta JM, Irigoyen MC, Bortoloto LA, Rochitte CE, Harris YT, et al. 2017. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome in a randomized trial. JCI Insight 2: 93340 10.1172/jci.insight.93340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czura CJ, Schultz A, Kaipel M, Khadem A, Huston JM, Pavlov VA, Redl H, Tracey KJ. 2010. Vagus nerve stimulation regulates hemostasis in swine. Shock 33: 608–613. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cc0183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ferrari GM, Crijns HJ, Borggrefe M, Milasinovic G, Smid J, Zabel M, Gavazzi A, Sanzo A, Dennert R, Kuschyk J, et al. 2011. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation: A new and promising therapeutic approach for chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 32: 847–855. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge WJ, van der Zanden EP, The FO, Bijlsma MF, van Westerloo DJ, Bennink RJ, Berthoud HR, Uematsu S, Akira S, van den Wijngaard RM, et al. 2005. Stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates macrophage activation by activating the Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 6: 844–851. 10.1038/ni1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES. 2000. The sympathetic nerve—An integrative interface between two supersystems: The brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev 52: 595–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E. 2018. Development of visual neuroprostheses: Trends and challenges. Bioelectron Med 4: 12 10.1186/s42234-018-0013-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein GS. 2003. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature 423: 356–361. 10.1038/nature01661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. 2007. Technology insight: Noninvasive brain stimulation in neurology—Perspectives on the therapeutic potential of rTMS and tDCS. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 3: 383–393. 10.1038/ncpneuro0530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giagka V, Serdijn WA. 2018. Realizing flexible bioelectronic medicines for accessing the peripheral nerves—Technology considerations. Bioelectron Med 4: 8 10.1186/s42234-018-0010-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler LE, Gaykema RP, Hansen MK, Anderson K, Maier SF, Watkins LR. 2000. Vagal immune-to-brain communication: A visceral chemosensory pathway. Auton Neurosci 85: 49–59. 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00219-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva CV, Novin D. 1990. The role of the hypothalamus and dorsal vagal complex in gastrointestinal function and pathophysiology. Ann NY Acad Sci 597: 207–222. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb16169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini S, Altavilla D, Cainazzo MM, Giuliani D, Bigiani A, Marini H, Squadrito G, Minutoli L, Bertolini A, Marini R, et al. 2003. Efferent vagal fibre stimulation blunts nuclear factor-κB activation and protects against hypovolemic hemorrhagic shock. Circulation 107: 1189–1194. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000050627.90734.ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guduru R, Liang P, Yousef M, Horstmyer J, Khizroev S. 2018. Mapping the brain's electric fields with magnetoelectric nanoparticles. Bioelectron Med 4: 10 10.1186/s42234-018-0012-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güemes A, Georgiou P. 2018. Review of the role of the nervous system in glucose homoeostasis and future perspectives towards the management of diabetes. Bioelectron Med 4: 9 10.1186/s42234-018-0009-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Tellez LA, Perkins MH, Perez IO, Qu T, Ferreira J, Ferreira TL, Quinn D, Liu ZW, Gao XB, et al. 2018. A neural circuit for gut-induced reward. Cell 175: 665–678.e623. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes WM, Olofsson PS, Kwan K, Hudson LK, Chavan SS, Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. 2015. Galantamine attenuates type 1 diabetes and inhibits anti-insulin antibodies in nonobese diabetic mice. Mol Med 21: 702–708. 10.2119/molmed.2015.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong GS, Pintea B, Lingohr P, Coch C, Randau T, Schaefer N, Wehner S, Kalff JC, Pantelis D. 2018a. Effect of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on muscle activity in the gastrointestinal tract (transVaGa): A prospective clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 10.1007/s00384-018-3204-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong GS, Zillekens A, Schneiker B, Pantelis D, de Jonge WJ, Schaefer N, Kalff JC, Wehner S. 2018b. Non-invasive transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation prevents postoperative ileus and endotoxemia in mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31: e13501 10.1111/nmo.13501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman WJ, Subramaniyan S, Rodriguiz RM, Wetsel WC, Grill WM, Terrando N. 2019. Modulation of neuroinflammation and memory dysfunction using percutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in mice. Brain Stimul 12: 19–29. 10.1016/j.brs.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Abe C, Sung SS, Moscalu S, Jankowski J, Huang L, Ye H, Rosin DL, Guyenet PG, Okusa MD. 2016. Vagus nerve stimulation mediates protection from kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury through α7nAChR+ splenocytes. J Clin Invest 126: 1939–1952. 10.1172/JCI83658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Rabbi MF, Labis B, Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ, Ghia JE. 2014. Central cholinergic activation of a vagus nerve-to-spleen circuit alleviates experimental colitis. Mucosal Immunol 7: 335–347. 10.1038/mi.2013.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiman AA, Chhabra KH, Lewis AG, Cederna PS, Seeley RJ, Low MJ, Bruns TM. 2018. Electrical stimulation of renal nerves for modulating urine glucose excretion in rats. Bioelectron Med 4: 7 10.1186/s42234-018-0008-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk R, Tejera D, Simon BJ, Heneka MT. 2017. Microglia modulation through external vagus nerve stimulation in a murine model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 10.1111/jnc.14284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibleur A, David O. 2018. Electroencephalographic read-outs of the modulation of cortical network activity by deep brain stimulation. Bioelectron Med 4: 2 10.1186/s42234-018-0003-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman FA, Chavan SS, Miljko S, Grazio S, Sokolovic S, Schuurman PR, Mehta AD, Levine YA, Faltys M, Zitnik R, et al. 2016. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: 8284–8289. 10.1073/pnas.1605635113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovatchev B. 2018. Automated closed-loop control of diabetes: The artificial pancreas. Bioelectron Med 4: 14 10.1186/s42234-018-0015-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Lee Y, Song C, Cho HR, Ghaffari R, Choi TK, Kim KH, Lee YB, Ling D, Lee H, et al. 2015. An endoscope with integrated transparent bioelectronics and theranostic nanoparticles for colon cancer treatment. Nat Commun 6: 10059 10.1038/ncomms10059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Howe C, Mishra S, Lee DS, Mahmood M, Piper M, Kim Y, Tieu K, Byun HS, Coffey JP, et al. 2018. Wireless, intraoral hybrid electronics for real-time quantification of sodium intake toward hypertension management. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115: 5377–5382. 10.1073/pnas.1719573115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman I, Hauger R, Sorkin L, Proudfoot J, Davis B, Huang A, Lam K, Simon B, Baker DG. 2016. Noninvasive transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation decreases whole blood culture-derived cytokines and chemokines: A randomized, blinded, healthy control pilot trial. Neuromodulation 19: 283–290. 10.1111/ner.12398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine YA, Koopman FA, Faltys M, Caravaca A, Bendele A, Zitnik R, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Tak PP. 2014. Neurostimulation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates disease in rat collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS ONE 9: e104530 10.1371/journal.pone.0104530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren S, Stewenius J, Sjölund K, Lilja B, Sundkvist G. 1993. Autonomic vagal nerve dysfunction in patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 28: 638–642. 10.3109/00365529309096103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Kwan K, Levine YA, Olofsson PS, Yang H, Li J, Joshi S, Wang H, Andersson U, Chavan SS, et al. 2014. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling inhibits inflammasome activation by preventing mitochondrial DNA release. Mol Med 20: 350–358. 10.2119/molmed.2013.00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi EB, Valdés-Ferrer SI, Steinberg BE. 2018. The vagus neurometabolic interface and clinical disease. Int J Obes (Lond) 42: 1101–1111. 10.1038/s41366-018-0086-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. 2008. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454: 428–435. 10.1038/nature07201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merabet LB, Rizzo JF, Amedi A, Somers DC, Pascual-Leone A. 2005. What blindness can tell us about seeing again: Merging neuroplasticity and neuroprostheses. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 71–77. 10.1038/nrn1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meregnani J, Clarençon D, Vivier M, Peinnequin A, Mouret C, Sinniger V, Picq C, Job A, Canini F, Jacquier-Sarlin M, et al. 2011. Anti-inflammatory effect of vagus nerve stimulation in a rat model of inflammatory bowel disease. Auton Neurosci 160: 82–89. 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz CN, Pavlov VA. 2018. Vagus nerve cholinergic circuitry to the liver and the gastrointestinal tract in the neuroimmune communicatome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 315: G651–G658. 10.1152/ajpgi.00195.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina-Osorio P, Rosas-Ballina M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ, Diamond B. 2012. Neural signaling in the spleen controls B-cell responses to blood-borne antigen. Mol Med 18: 618–627. 10.2119/molmed.2012.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Saadat D, Kwon O, Lee Y, Choi WS, Kim JH, Yeo WH. 2016. Recent advances in salivary cancer diagnostics enabled by biosensors and bioelectronics. Biosens Bioelectron 81: 181–197. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munyaka P, Rabbi MF, Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ, Khafipour E, Ghia JE. 2014. Central muscarinic cholinergic activation alters interaction between splenic dendritic cell and CD4+CD25 – T cells in experimental colitis. PLoS ONE 9: e109272 10.1371/journal.pone.0109272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niijima A. 1996. The afferent discharges from sensors for interleukin 1β in the hepatoportal system in the anesthetized rat. J Auton Nerv Syst 61: 287–291. 10.1016/S0165-1838(96)00098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson PS, Tracey KJ. 2017. Bioelectronic medicine: Technology targeting molecular mechanisms for therapy. J Intern Med 282: 3–4. 10.1111/joim.12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson PS, Levine YA, Caravaca A, Chavan SS, Pavlov VA, Faltys M, Tracey KJ. 2015. Single pulse and unidirectional electrical activation of the cervical vagus nerve reduces tumor necrosis factor in endotoxemia. Bioelectron Med 2: 37–42. 10.15424/bioelectronmed.2015.00006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson PS, Metz CN, Pavlov VA. 2017. The neuroimmune communicatome in inflammation. In Inflammation: From molecular and cellular mechanisms to the clinic (ed. Cavaillon J, Singer M), pp. 1485–1516. Wiley, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani M, Ochani K, Yang LH, Hudson L, Lin X, Patel N, Johnson SM, et al. 2008. Modulation of TNF release by choline requires α7 subunit nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated signaling. Mol Med 14: 567–574. 10.2119/2008-00079.Parrish [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. 2012. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—Linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8: 743–754. 10.1038/nrendo.2012.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. 2015. Neural circuitry and immunity. Immunol Res 63: 38–57. 10.1007/s12026-015-8718-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. 2017. Neural regulation of immunity: Molecular mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Neurosci 20: 156–166. 10.1038/nn.4477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. 2019. Bioelectronic medicine: Updates, challenges and paths forward. Bioelectron Med 5: 1 10.1186/s42234-019-0018-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Wang H, Czura CJ, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. 2003. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: A missing link in neuroimmunomodulation. Mol Med 9: 125–134. 10.1007/BF03402177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani K, Huston JM, Czura CJ, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ. 2006. Central muscarinic cholinergic regulation of the systemic inflammatory response during endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 5219–5223. 10.1073/pnas.0600506103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Yang LH, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani K, Lin X, Levi J, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Czura CJ, et al. 2007. Selective α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves survival in murine endotoxemia and severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 35: 1139–1144. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259381.56526.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Puerta M, Ochani K, Chavan S, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ. 2009. Brain acetylcholinesterase activity controls systemic cytokine levels through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun 23: 41–45. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Chavan SS, Tracey KJ. 2018. Molecular and functional neuroscience in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 36: 783–812. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelot NA, Grill WM. 2018. Effects of vagal neuromodulation on feeding behavior. Brain Res 1693: 180–187. 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing KY, Wasilczuk KM, Ward MP, Phillips EH, Vlachos PP, Goergen CJ, Irazoqui PP. 2018. B fibers are the best predictors of cardiac activity during vagus nerve stimulation. Bioelectron Med 4: 5 10.1186/s42234-018-0005-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RC, McTigue DM, Hermann GE. 1996. Vagal control of digestion: Modulation by central neural and peripheral endocrine factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 20: 57–66. 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00040-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Parrish WR, Ochani K, Harris YT, Huston JM, Chavan S, Tracey KJ. 2008. Splenic nerve is required for cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway control of TNF in endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 11008–11013. 10.1073/pnas.0803237105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, et al. 2011. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 334: 98–101. 10.1126/science.1209985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Valdés-Ferrer SI, Dancho ME, Ochani M, Katz D, Cheng KF, Olofsson PS, Chavan SS, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ, et al. 2015. Xanomeline suppresses excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine responses through neural signal-mediated pathways and improves survival in lethal inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 44: 19–27. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J, Sahota N, Patel P, Mehdi SF, Wiese MM, Mahboob HB, Bravo M, Eden DJ, Bashir MA, Kumar A, et al. 2016. Obesity paradox, obesity orthodox, and the metabolic syndrome: An approach to unity. Mol Med 22: 873–885. 10.2119/molmed.2016.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehpour F, Mahmoudi J, Kamari F, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Rasta SH, Hamblin MR. 2018. Brain photobiomodulation therapy: A narrative review. Mol Neurobiol 55: 6601–6636. 10.1007/s12035-017-0852-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuan-Alberte P, Alexander MR, Hague RJM, Rawson FJ. 2018. Electrochemically stimulating developments in bioelectronic medicine. Bioelectron Med 4: 1 10.1186/s42234-018-0001-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satapathy SK, Ochani M, Dancho M, Hudson LK, Rosas-Ballina M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Olofsson PS, Harris YT, Roth J, Chavan S, et al. 2011. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and other obesity-associated complications in high-fat diet-fed mice. Mol Med 17: 599–606. 10.2119/molmed.2011.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Levy BD. 2018. Resolvins in inflammation: Emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J Clin Invest 128: 2657–2669. 10.1172/JCI97943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman HA, Stiegler A, Tsaava T, Newman J, Steinberg BE, Masi EB, Robbiati S, Bouton C, Huerta PT, Chavan SS, et al. 2018. Standardization of methods to record vagus nerve activity in mice. Bioelectron Med 4: 3 10.1186/s42234-018-0002-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg BE, Silverman HA, Robbiati S, Gunasekaran MK, Tsaava T, Battinelli E, Stiegler A, Bouton CE, Chavan SS, Tracey KJ, et al. 2016. Cytokine-specific neurograms in the sensory vagus nerve. Bioelectron Med 3: 7–17. 10.15424/bioelectronmed.2016.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez AN, Hsu TM, Liu CM, Noble EE, Cortella AM, Nakamoto EM, Hahn JD, de Lartigue G, Kanoski SE. 2018. Gut vagal sensory signaling regulates hippocampus function through multi-order pathways. Nat Commun 9: 2181 10.1038/s41467-018-04639-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot S, Abdulnour RE, Burkett PR, Lee S, Cronin SJ, Pascal MA, Laedermann C, Foster SL, Tran JV, Lai N, et al. 2015. Silencing nociceptor neurons reduces allergic airway inflammation. Neuron 87: 341–354. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot S, Foster SL, Woolf CJ. 2016. Neuroimmunity: Physiology and pathology. Annu Rev Immunol 34: 421–447. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarn J, Legg S, Mitchell S, Simon B, Ng WF. 2018. The effects of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on fatigue and immune responses in patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Neuromodulation 10.1111/ner.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey KJ. 2002. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 420: 853–859. 10.1038/nature01321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey KJ. 2009. Reflex control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 9: 418–428. 10.1038/nri2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey KJ. 2014. The revolutionary future of bioelectronic medicine. Bioelectron Med 1: 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Waldburger JM, Boyle DL, Edgar M, Sorkin LS, Levine YA, Pavlov VA, Tracey K, Firestein GS. 2008. Spinal p38 MAP kinase regulates peripheral cholinergic outflow. Arthritis Rheum 58: 2919–2921. 10.1002/art.23807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH, Wang H, Yang H, Ulloa L, et al. 2003. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature 421: 384–388. 10.1038/nature01339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. 2002. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 20: 125–163. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.082401.104914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G, Kang L, Li J, Long Y, Wei H, Ferreira CA, Jeffery JJ, Lin Y, Cai W, Wang X. 2018. Effective weight control via an implanted self-powered vagus nerve stimulation device. Nat Commun 9: 5349 10.1038/s41467-018-07764-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanos TP, Silverman HA, Levy T, Tsaava T, Battinelli E, Lorraine PW, Ashe JM, Chavan SS, Tracey KJ, Bouton CE. 2018. Identification of cytokine-specific sensory neural signals by decoding murine vagus nerve activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115: E4843–E4852. 10.1073/pnas.1719083115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Schwemmer MA, Ting JE, Majstorovic CE, Friedenberg DA, Bockbrader MA, Jerry Mysiw W, Rezai AR, Annetta NV, Bouton CE, et al. 2018. Extracting wavelet based neural features from human intracortical recordings for neuroprosthetics applications. Bioelectron Med 4: 11 10.1186/s42234-018-0011-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XP, Zhao Y, Qin XY, Wan LY, Fan XX. 2019. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury and promotes microglial M2 polarization via interleukin-17A inhibition. J Mol Neurosci 67: 217–226. 10.1007/s12031-018-1227-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]