Abstract

Biological processes are dynamically regulated by signaling networks composed of protein kinases and phosphatases. Calcineurin, or PP3, is a conserved phosphoserine/phosphothreonine-specific protein phosphatase and member of the PPP family of phosphatases. Calcineurin is unique, however, in its activation by Ca2+ and calmodulin. This ubiquitously expressed phosphatase controls Ca2+-dependent processes in all human tissues, but is best known for driving the adaptive immune response by dephosphorylating the nuclear factor of the activated T-cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors. Therefore, calcineurin inhibitors, FK506 (tacrolimus), and cyclosporin A serve as immunosuppressants. We describe some of the adverse effects associated with calcineurin inhibitors that result from inhibition of calcineurin in nonimmune tissues, illustrating the many functions of this enzyme that have yet to be elucidated. In fact, calcineurin has essential roles beyond the immune system, from yeast to humans, but since its discovery more than 30 years ago, only a small number of direct calcineurin substrates have been shown (∼75 proteins). This is because of limitations in current methods for identification of phosphatase substrates. Here we discuss recent insights into mechanisms of calcineurin activation and substrate recognition that have been critical in the development of novel approaches for identifying its targets systematically. Rather than comprehensively reviewing known functions of calcineurin, we highlight new approaches to substrate identification for this critical regulator that may reveal molecular mechanisms underlying toxicities caused by calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppression.

STRUCTURE AND ACTIVATION OF CALCINEURIN

Canonical Calcineurin Isozymes

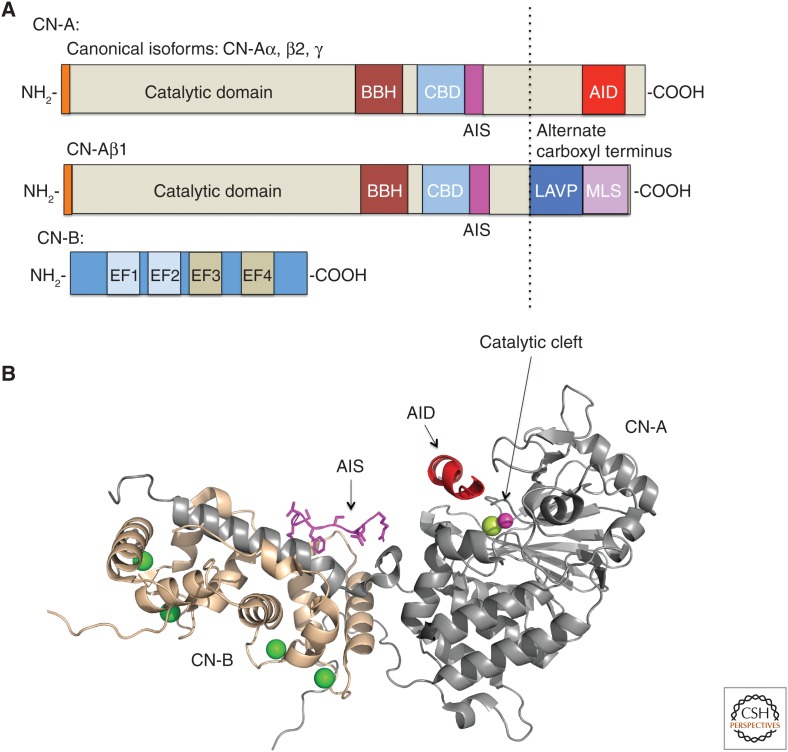

Calcineurin is a heterodimer composed of catalytic (CN-A) and regulatory subunits (CN-B) (Fig. 1). Calcineurin is a metalloenzyme, and CN-A contains two cofactors (Zn2+ and Fe2+) that coordinate a water molecule during catalysis (Rusnak and Mertz 2000). CN-A isoforms, α, β1, β2, and γ, are encoded by three human genes: PPP3CA, PPP3CB (alternatively spliced to generate β1 and β2), and PPP3CC. Of these α, β2, and γ are highly homologous canonical isoforms that, despite some divergence at their amino and carboxyl termini, share domain architectures and activation mechanisms that are widely conserved in calcineurin enzymes across eukaryotes (Thewes 2014). CN-A contains a globular catalytic domain that is highly related to other PPP phosphatases, followed by an α-helical region that binds CN-B (Fig. 1A; CN-B-binding helix (BBH)), and a calmodulin-binding domain, which binds one molecule of Ca2+-bound calmodulin when activated (Fig. 1A, CBD; Aramburu et al. 2000; Rusnak and Mertz 2000). In the inactive enzyme, this region is largely unstructured, but becomes α-helical on binding Ca2+–calmodulin and contains additional sequences that stabilize the calmodulin–calcineurin interaction (Shen et al. 2008; Rumi-Masante et al. 2012; Dunlap et al. 2013). Immediately carboxy terminal to the CBD is the recently defined autoinhibitory sequence (AIS) that occludes one of two substrate-binding pockets in the absence of Ca2+ and Ca2+–calmodulin to silence the enzyme (see below) (Fig. 1B; Li et al. 2016). Finally, the carboxyl termini of canonical CN-A subunits (α, β2, and γ) contain an autoinhibitory domain (AID), which forms two short α helices that directly block the catalytic site under basal conditions (i.e., nonsignaling, cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations [<100 nm]) (Fig. 1B); a peptide encoding the AID sequence inhibits calcineurin in vivo and in vitro (Hashimoto et al. 1990; Kissinger et al. 1995). CN-B, the regulatory subunit of calcineurin, encoded by PPP3R1 and PPP3R2, is a highly conserved Ca2+-binding protein that contains two lobes with a pair Ca2+-binding EF-hands (Fig. 1); one pair has low affinity (10–50 µm range) and the other high affinity (submicromolar) for Ca2+ (Stemmer and Klee 1994). Myristoylation of the CN-B amino terminus promotes thermal stability of the enzyme (Aitken et al. 1982).

Figure 1.

Overview of calcineurin structure. (A) Schematic of canonical (α, β2, and γ) and β1 CN isoforms. BBH, CN-B binding helix; CBD, calmodulin-binding domain; AIS, autoinhibitory sequence; AID, autoinhibitory domain; MLS, membrane localization sequence; EF, calcium-binding helix-loop-helix domain (EF1, 2 are lower affinity calcium-binding domains and EF3, 4 are higher affinity calcium-binding domains). (B) Ribbon diagram of CN heterodimer from PDB entry 4ORC (Li et al. 2016). CN-A subunit is in gray and CN-B subunit is in wheat. Calcium ions are colored in green, AIS in magenta, and AID in red. The catalytic site is represented by zinc (magenta) and iron (lime) metal ions.

Activation Mechanism

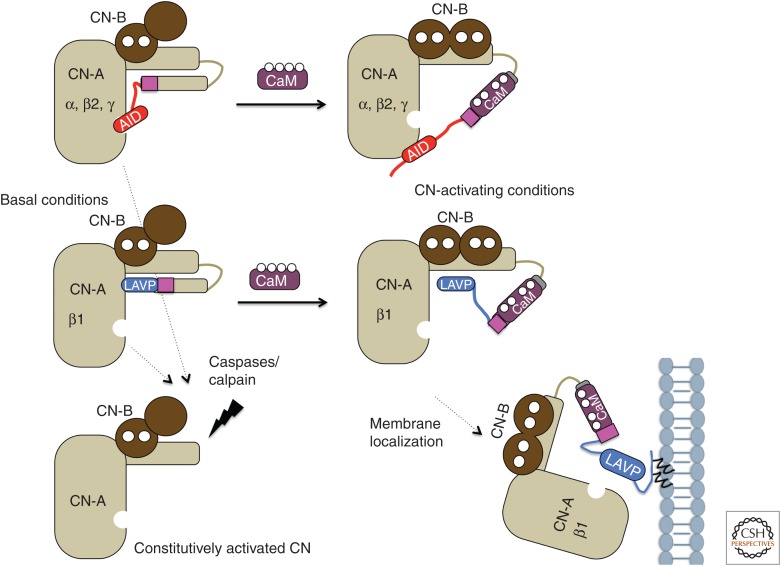

Ca2+ activates calcineurin first by binding to CN-B, and subsequently through the interaction of Ca2+–calmodulin with CN-A (Stemmer and Klee 1994). Under basal cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]cyto <100 nm), only the high-affinity Ca2+-binding sites of CN-B are occupied, and the enzyme is inactive. Elevation in [Ca2+]cyto on physiological stimulation ([Ca2+]cyto >1 µm) occupies the low-affinity sites on CN-B, causing a conformational change in CN-A that promotes Ca2+–calmodulin binding and decreases the Km for substrates (Stemmer and Klee 1994; Yang and Klee 2000). Further binding of Ca2+–calmodulin to CN-A displaces the AIS from the substrate-binding pocket and the AID from the catalytic active site to achieve maximal catalytic activity (Fig. 2; Stemmer and Klee 1994; Perrino et al. 1995; Li et al. 2016). Thus, Ca2+ binding to CN-B and Ca2+–calmodulin binding to CN-A cooperatively activate calcineurin by overcoming autoinhibition at two sites, resulting in a large dynamic response, as well as rapid inactivation on termination of Ca2+ signaling. In contrast to this reversible regulation, cleavage of the entire carboxy terminal CN-A domain to remove the AIS and AID irreversibly activates calcineurin. CN-A is cleaved by the Ca2+-dependent protease, calpain, to constitutively activate calcineurin independent of Ca2+–calmodulin in several pathophysiological contexts, and can also be proteolyzed by caspase-3, which contributes to synaptic dysfunction in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 2; Mukerjee et al. 2001; Wu et al. 2007; D'Amelio et al. 2011). Calcineurin is irreversibly inactivated by oxidation, both in vivo and in vitro (Wang et al. 1996; Sommer et al. 2000; Namgaladze et al. 2005). Originally, this was thought to occur by oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, but recent results suggest oxidation of key methionine residues as the mechanism (Zhou et al. 2014).

Figure 2.

Schematic of proposed activation mechanism for canonical and calcineurin-β1 isozymes. Ca2+ ions binding CN-B and CaM (calmodulin) are in white. The magenta box represents the autoinhibitory sequence (AIS) sequence. For canonical calcineurin isozymes, Ca2+ binding to CN-B and calmodulin binding to CN-A relieves autoinhibition by the AIS and autoinhibitory domain (AID). For the calcineurin β1 isozyme, activation by calcium and calmodulin entail removal of the AIS and LAVP sequence from the substrate-binding groove. Activation may also involve localization of calcineurin-β1 to membranes via lipid modifications at the carboxy-terminal end. For all calcineurin isozymes, cleavage of the carboxy-terminal domains by calpain or caspases results in constitutively active enzyme.

Calcineurin-β1 Isozyme

A distinct activation mechanism is exhibited by the calcineurin-β1 isozyme consisting of a conserved and widely expressed variant of CN-A (the CN-Aβ1 isoform), which is generated by alternative 3′-end processing of the PPP3CB transcript (Lara-Pezzi et al. 2007; Bond et al. 2017), complexed with CN-B. The CN-Aβ1 isoform is identical to CN-Aβ2 through the CBD, but then diverges to encode a unique carboxyl terminus that lacks the AID, and instead contains a substrate-like sequence, LAVP (Fig. 1A). This sequence autoinhibits calcineurin-β1 by binding strongly to the same substrate-binding pocket that is occluded by the AIS (Bond et al. 2017). The absence of an AID results in higher basal activity and significant activation of calcineurin-β1 by Ca2+ in the absence of calmodulin. Furthermore, with LxVP-containing substrates (i.e., RII peptide or proteins), maximal activity of calcineurin-β1 in the presence of Ca2+ and Ca2+–calmodulin is significantly lower than that of canonical calcineurin-β2 because the LAVP sequence persists in the substrate-binding pocket, even after displacement of the AIS (Fig. 2). The unique carboxyl terminus of CN-Aβ1 also promotes distinct protein interactions and targets the enzyme to intracellular membranes, including the Golgi apparatus (Felkin et al. 2011; Gómez-Salinero et al. 2016). This membrane association is mediated by lipidation of conserved cysteines, which may also contribute to enzyme activation in vivo (Fig. 2; I Ulengin-Talkish and MS Cyert, unpubl.). The few studies that focus on calcineurin-β1 show that its physiological functions are distinct from those of canonical calcineurin isozymes. For instance, in mice, CN-Aβ1 is highly expressed in regenerating muscle and stem cells (Lara-Pezzi et al. 2007). In contrast to CN-Aβ2, CN-Aβ1 is cardioprotective rather than hypertrophic when overexpressed in the heart, an effect attributed to activation of serine one-carbon metabolism (Felkin et al. 2011; Padrón-Barthe et al. 2018). Mice lacking CN-Aβ1 (but not CN-Aβ2) are viable and fertile, but develop cardiac hypertrophy with age, and display increased hypertrophy in response to pressure overload (Padrón-Barthe et al. 2018). Thus, in vivo, this isoform exhibits unique characteristics by failing to activate NFAT, and instead regulates signaling pathways such as AKT/mTOR. Direct substrates for this isoform remain to be identified. Furthermore, alternative splicing may be a more common mechanism than previously appreciated for modifying calcineurin properties in vivo. Splicing of CN-A isoforms changes during development of mouse skeletal muscle, and expression of fetal splice forms of CN-A in adult tissue impacts its contractile and Ca2+-handling properties (Brinegar et al. 2017).

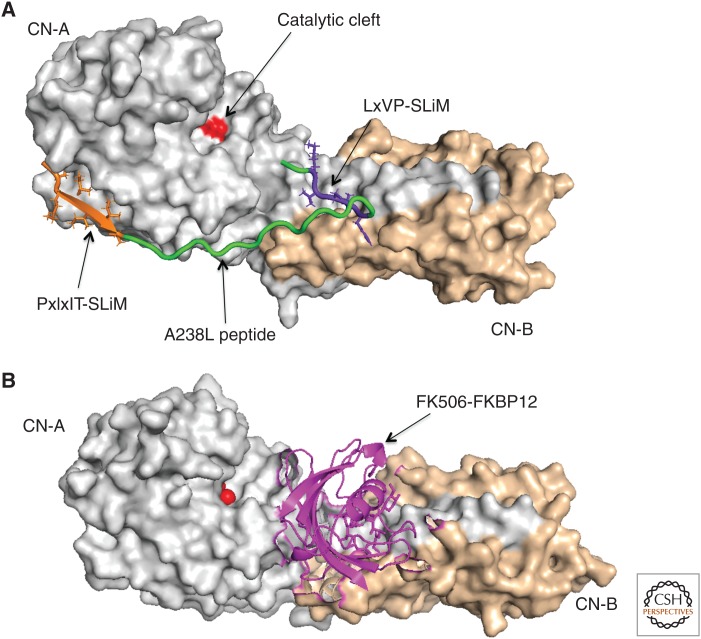

SLiMS MEDIATE CALCINEURIN SUBSTRATE RECOGNITION

Short linear motifs (SLiMs), short degenerate peptide sequences that occur in disordered regions of proteins critically mediate dynamic, low-affinity protein–protein interactions during signaling (Tompa et al. 2014). Calcineurin recognizes two SLiMs in its substrates, PxIxIT and LxVP, enabling specificity (Fig. 3; Roy and Cyert 2009; Nygren and Scott 2016). These SLiMs may be hundreds of residues away from sites of dephosphorylation and are found at variable distances and orientations with respect to each other (Grigoriu et al. 2013). PxIxIT and LxVP sequences were first defined in NFAT, and subsequently in multiple calcineurin substrates from humans and fungi (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Rodríguez et al. 2009; Roy and Cyert 2009; Li et al. 2011; Goldman et al. 2014; Nygren and Scott 2016; Sheftic et al. 2016; Gibson et al. 2019). The surfaces on calcineurin that bind these SLiMs are evolutionarily conserved, and mediate a characteristic mode of substrate recognition that allows human calcineurin to functionally substitute for the yeast enzyme (Li et al. 2004; Grigoriu et al. 2013; Bond et al. 2017).

Figure 3.

Calcineurin interacts with substrates via SLiMs, PxIxIT, and LxVP. (A) Space-filled diagram of calcineurin heterodimer complexed with the calcineurin-inhibiting domain from the viral protein A238L (PBD entry 4FOZ; Grigoriu et al. 2013). CN-A subunit is in gray and CN-B subunit is in wheat. The A238L peptide is in green with its PxIxIT-SLiM colored in orange and the LxVP-SLiM colored in purple. The calcineurin catalytic site is marked in red. (B) Space-filled diagram of calcineurin heterodimer complexed with FK506-FKBP12 (PDB entry ITCO; Griffith et al. 1995). CN-A and -B subunits and the calcineurin catalytic site are colored and in A. The FK506-FKBP12 complex is in magenta and occupies the same groove as the LxVP-SLiM in A.

The PxIxIT Motif

PxIxIT motifs are required in most, but not all, calcineurin substrates or regulators. PxIxIT motifs are degenerate in sequence, but typically share a core consensus sequence: [PI][IVLF][IVLF][TSHDEQNKR]. Compromising the PxIxIT sequence or adding a peptide or small molecule that competes with native PxIxIT sequences for binding to calcineurin inhibits dephosphorylation of many substrates in vitro and in vivo (Aramburu et al. 1999; Roy and Cyert 2009; Matsoukas et al. 2015; Nguyen et al. 2018). PxIxITs vary widely in their affinity for calcineurin, with motifs from five different yeast substrates having Kds ranging from ∼15 to 250 µm (Roy et al. 2007). Changing the PxIxIT affinity alters the Ca2+-concentration dependence of substrate dephosphorylation, showing that fine-tuning of this single interaction can modulate the output of Ca2+ signaling in vivo (Czirják and Enyedi 2006; Roy et al. 2007; Muller et al. 2009). Recent analyses of PxIxIT peptide affinity using a novel microfluidic technology identified residues outside the PxIxIT core that influence affinity for calcineurin: basic residues at position 2 increase affinity; hydrophobic or acidic residues at position -1 increase or decrease affinity, respectively; and acidic or phosphorylated residues at position 9 increase affinity (Nguyen et al. 2018). These insights promise to improve PxIxIT discovery and, ultimately, identification of new calcineurin substrates, anchoring proteins and regulators.

Structures of PxIxIT–calcineurin complexes show this motif forming a β strand (Li et al. 2007, 2012; Grigoriu et al. 2013) that contacts a hydrophobic groove in CN-A formed by two β sheets: β11 and β14. This docking groove is remote from the catalytic cleft and the carboxy-terminal CN-B and calmodulin-binding regions, allowing PxIxIT sequences to interact equally with the active and inactive forms of the enzyme (Fig. 3A). Thus, PxIxIT is critical for recruiting calcineurin to substrates or regulators, such as the AKAP79/150 scaffold protein (Li et al. 2012), but high-affinity PxIxIT peptide inhibitors do not interact with the catalytic center, or interfere with dephosphorylation of small molecules or substrates that lack a PxIxIT site (Aramburu et al. 1998). Mutations in a conserved sequence (330NIR332 to AAA in human CN-Aα) interfere with PxIxIT binding, and severely reduce enzyme function in vivo while having no effect on the catalytic active site per se (Li et al. 2004; Roy et al. 2007).

The LxVP Motif

The LxVP motif is dominated by two hydrophobic residues, L and V, which are buried in a hydrophobic channel formed at the intersection of CN-A and CN-B when bound to calcineurin (Fig. 3A; Rodríguez et al. 2009; Grigoriu et al. 2013; Sheftic et al. 2016). Structures of two LxVP:calcineurin complexes show this sequence binding in an extended conformation, and reveal additional hydrogen bonds formed by amino acids at the two positions (-1, -2) preceding the leucine (Grigoriu et al. 2013; Sheftic et al. 2016). Two AISs in CN-A also bind this site: The AIS, 416ARVFSVLR423 fills the LxVP-binding pocket with FSVL, overlaying the LxVP sequence from calcineurin-interacting partners (Li et al. 2016), preventing substrates from accessing the LxVP-binding groove under basal conditions (Fig. 2). A unique AIS in CN-Aβ1, 460MQLAVP465, also binds this region (Bond et al. 2017). Finally, in combination with their immunophilin-binding partners, the immunosuppressants, FK506 and CysA, specifically block this docking site, indicating that LxVP binding is essential for dephosphorylation of protein substrates (Figs. 3B and 4; Griffith et al. 1995; Kissinger et al. 1995; Jin and Harrison 2002; Rodríguez et al. 2009; Grigoriu et al. 2013).

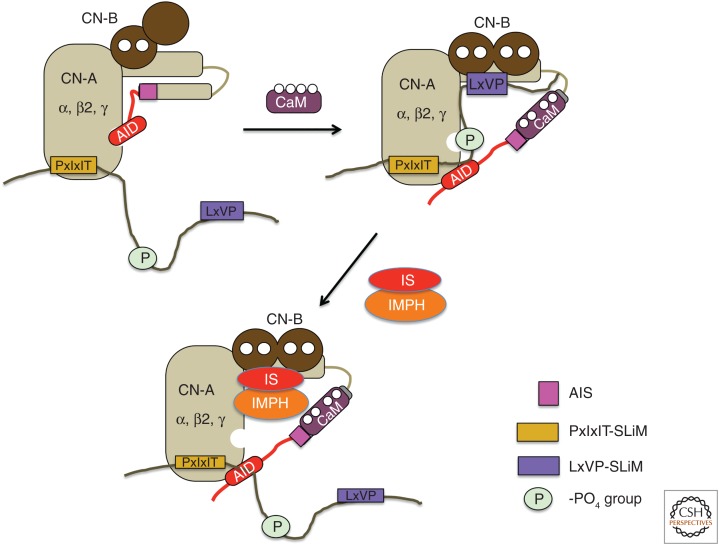

Figure 4.

Schematic for proposed mechanism of substrate engagement by calcineurin. The substrate is shown as a dark brown line with PxIxIT (yellow) and LxVP (purple) SLiMs and the phosphate group to be removed (green circle). The PxIxIT SLiM can interact with calcineurin under nonactivating conditions, whereas the LxVP SLiM engages with calcineurin only after enzyme activation by Ca2+ and calmodulin. The immunosuppressants (IS) complexes, either CsA-cyclophilin or FK506-FKBP (both denoted as IS, red) with immunophilin (IMPH, orange) occlude the LxVP pocket to inhibit substrate binding.

Coordination of PxIxIT and LxVP during Substrate Dephosphorylation

PxIxIT and LxVP docking are required for dephosphorylation of most substrates. The viral protein, A238L effectively and competitively inhibits yeast and human calcineurin by blocking both SLiM-binding surfaces without engaging the active site (Fig. 3A; Grigoriu et al. 2013). However, PxIxIT and LxVP motifs play distinct roles during dephosphorylation. By binding under both basal and signaling conditions that elevate [Ca2+]cyto, PxIxIT motifs target calcineurin to substrates/regulators or to protein complexes that contain substrates. For example, the human scaffold protein, AKAP79/150, co-binds calcineurin and two substrates (the L-type Ca2+ channel and the protein kinase A (PKA) RII regulatory subunit) that lack PxIxITs but contain LxVP motifs (Murphy et al. 2014). In contrast, LxVP motifs bind calcineurin only after activation by Ca2+ and Ca2+–calmodulin, and may orient the phosphosite toward the catalytic center of calcineurin for dephosphorylation (Fig. 4), as shown by computational modeling of calcineurin in complex with the LxVP-containing peptide derived from the PKA RII regulatory subunit (Grigoriu et al. 2013). This model predicts that calcineurin dephosphorylates sites that are 9–15 residues carboxy terminal to the LxVP (Grigoriu et al. 2013). However, only a subset of substrates currently fit this paradigm (PKA RII, RCAN1-3), perhaps because of challenges in identifying functional PxIxIT and/or LxVP sequences that are particularly degenerate/low affinity. For example, the conserved calcineurin regulator from yeast, Rcn1, contains a very low-affinity PxIxIT motif lacking a P (GAITID) (Mehta et al. 2009), which works in combination with a canonical LxVP sequence (Rodríguez et al. 2009). Similarly, in substrates with a high-affinity PxIxIT, a degenerate hydrophobic sequence may be sufficient to engage the LxVP-binding pocket. NFAT isoforms also illustrate this theme: NFATc2 contains a comparatively high-affinity PxIxIT and a lower-affinity LxVP, whereas NFATc1 contains a lower-affinity PxIxIT coupled with a high-affinity LxVP (Martínez-Martínez et al. 2006).

SLiMs Mediate Rapid Evolution of Calcineurin Signaling Networks

SLiMs are more rapidly evolving than globular protein domains and may be acquired de novo (Davey et al. 2015). Thus, the combination of PxIxIT and LxVP motifs of differing strengths allows a wide variety of proteins to be potential calcineurin substrates. Although calcineurin is highly conserved in structure between yeast and mammals, the calcineurin network has diverged significantly between these two species because of the evolving nature of calcineurin-binding SLiMs (Goldman et al. 2014). Many PxIxITs in S. cerevisiae proteins are not conserved even among closely related species and, as shown for the Elm1 protein kinase, determine whether or not the protein is regulated by calcineurin (Goldman et al. 2014). Thus, SLiMs direct surprisingly dynamic changes in the calcineurin signaling network. Substantial rewiring also occurs between the yeast and worm SH3-SLiM-mediated interactome (Xin et al. 2013), suggesting that evolvability is a general feature of SLiM-based PPI networks.

STRATEGIES TO IDENTIFY HUMAN CALCINEURIN SUBSTRATES

Substrates are inherently more difficult to identify for phosphatases relative to kinases, as proteins must be appropriately phosphorylated before examining their dephosphorylation, and because incorporation of a labeled PO4 residue is easier to detect than its loss. Calcineurin in yeast was first shown to mediate response to extracellular stresses through its substrate, the transcription factor Crz1 (Stathopoulus and Cyert 1997). Strategies such as two-hybrid interaction were able to identify additional yeast calcineurin substrates, leading to the study of calcineurin-dependent regulation of endocytosis, intracellular trafficking, response to high pH stress, the mating response and cell-cycle control (Piña et al. 2011; Alvaro et al. 2014; Goldman et al. 2014; Arsenault et al. 2015; Guiney et al. 2015; Ly and Cyert 2017). In humans, a handful of substrates for calcineurin were first identified via in vitro assays using well-characterized proteins with known kinases (Klee et al. 1988). The demonstration that FK506 and CysA specifically inhibit calcineurin (Liu et al. 1991) revolutionized investigations of calcineurin function, and use of these inhibitors remains central to calcineurin substrate identification to this day. Currently, ∼75 human calcineurin substrates have been identified, although many more likely remain to be discovered, as illustrated by the broad physiological consequences of calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppression (see below) (Li et al. 2011, 2013; Sheftic et al. 2016). Calcineurin is also highly conserved, and plays critical roles in a diversity of lower eukaryotes that will not be discussed here (Lee et al. 2013; Juvvadi et al. 2014; Thewes 2014; Liu et al. 2015; Paul et al. 2015; Daane et al. 2018).

Phosphoproteomics

Advances in phosphoproteomics are facilitating calcineurin substrate identification. Studies in yeast showed that 699 phosphorylated peptides were more abundant in calcineurin-deficient versus calcineurin-proficient cell extracts, and that an equivalent number of phosphorylated peptides (660) decreased in abundance when calcineurin was mutated or inhibited (Goldman et al. 2014). Therefore, to identify direct targets, 65 proteins whose phosphorylation increased under calcineurin-deficient conditions and contained putative PxIxIT motifs were examined. Candidates were tested for interaction with calcineurin and, after phosphorylation with copurifying kinases, examined for in vitro dephosphorylation by calcineurin. This study identified the first signaling network for calcineurin in any organism, made up of 39 yeast proteins that revealed new calcineurin functions (Alvaro et al. 2014; Goldman et al. 2014; Ly and Cyert 2017). Integrated analyses of T-cell receptor (TCR) and Ca2+-calcineurin-mediated signaling in mouse thymocytes used isobaric labeling to reveal new calcineurin substrates including Itpkb, a calmodulin-regulated inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase (Hatano et al. 2016). Interestingly, these studies also identified multiple proteins that did not show obvious alterations in phosphorylation during TCR signaling because they were concurrently dephosphorylated by calcineurin and phosphorylated by ERK. Thus, phosphoproteomic analyses may fail to identify direct calcineurin targets, and are limited by the choice of tissue and signaling conditions.

Interaction-Based Approaches

Affinity purification coupled to mass spectrometry (AP-MS) is an alternative strategy that has identified calcineurin-interacting proteins, some of which are substrates. Inp53, yeast synaptojanin, was identified as a conserved substrate of calcineurin by identifying proteins that interact with yeast calcineurin specifically under osmotic stress conditions, when calcineurin is active (Guiney et al. 2015). Fifteen calcineurin-interacting partners, including known substrates GSK-3β, and Rb (Qiu and Ghosh 2008; Kim et al. 2009) were identified in Jurkat T-ALL cells expressing constitutively active, truncated CN-Aα (Tosello et al. 2016). On the whole, however, AP-MS studies have revealed relatively few calcineurin-interacting proteins, and are biased toward identifying high affinity, stable interactors such as regulators and scaffolds rather than dynamic SLiM-mediated substrate interactions (Sundell and Ivarsson 2014; St-Denis et al. 2016; Huttlin et al. 2017). In contrast, yeast two-hybrid assays and related methods are sufficiently sensitive to detect transient SLiM-mediated protein–protein interactions, and multiple calcineurin substrates from yeast and humans have been identified using this technique (Liu et al. 2006; O'Donnell et al. 2010; Piña et al. 2011; Arsenault et al. 2015; Nakamura et al. 2017). However, yeast two-hybrid analyses are also prone to false positives, and can be applied only to a subset of the proteome (Mrowka et al. 2001; Stynen et al. 2012). Recently developed methods that capture transient interactions such as proximity-dependent biotinylation coupled with mass spec (PDB-MS) offer a new strategy to identify dynamic calcineurin–substrate interactions, especially in combination with calcineurin mutants whose interaction with either PxIxIT or LxVP motifs is compromised (Gingras et al. 2019; Wigington et al. 2019). Mutations in the conserved catalytic site have also been used to “trap” phosphatase–substrate interactions and successfully identify substrates for PPI, a strategy that has yet to be applied to calcineurin (Wu et al. 2018).

In Silico Strategies for SLiM Identification

To date, computational strategies for PxIxIT or LxVP discovery have relied on identifying matches to a consensus sequence (i.e., a regular expression) in combination with disorder or accessibility predictions (Goldman et al. 2014; Sheftic et al. 2016). Recently, human proteins containing a match to the “πϕLxVP” regular expression, which was compiled from published sequences and structural predictions, plus a PxIxIT consensus match, predicted a large network of 567 potential calcineurin substrates (Sheftic et al. 2016). This approach, however, is limited to finding only exact matches to the regular expression, and treats information from all positions equally. Additional data is needed to strengthen in silico approaches for identification of calcineurin-binding SLiMs. First, information about how specific sequence elements either positively or negatively affect affinity of these motifs would improve evaluation of potential motif instances. A recent quantitative study of PxIxIT-calcineurin affinities revealed the impact of nonconsensus residues, and provides valuable insights that can be applied to proteome-wide PxIxIT identification (see above; Nguyen et al. 2018). Second, discovery of more calcineurin-binding peptides of both PxIxIT and LxVP types would expand the repertoires of these SLiMs and allow construction of a statistical model for each motif (i.e., a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM)), which includes weighted information for each residue in the motif. This approach provides a scoring method that ranks each instance in the proteome based on its degree of similarity to the PSSM, allowing sequences that are similar to but do not match the regular expression to be identified (Krystkowiak et al. 2018). Currently, however, fewer than 15 examples each of human PxIxITs or LxVPs are in the literature, and each set includes related motifs from four NFAT isoforms. Proteomic peptide phage display (ProP-PD), which uses a phage library expressing tiled 16-mers from all predicted disordered regions in the human proteome, is an ideal method to experimentally identify SLiM instances (Sundell and Ivarsson 2014), and was used to discover 20 additional PxIxIT and 25 additional LxVP sequences in the human proteome (Wigington et al. 2019). These human peptides directly identified new calcineurin substrates, including Notch1 and Nup153, and allowed construction and testing of robust PSSMs for PxIxIT and LxVP, containing 12 and 7 positions, respectively, that were used for motif discovery in the proteome (Wigington et al. 2019). A major strength of in silico SLiM-based strategies is the ability to identify putative calcineurin targets comprehensively (i.e., without experimental limitations such as protein level and accessibility or tissue/cell-type-specific expression). Using this approach, we discovered that calcineurin regulates transport through the nuclear pore by dephosphorylating multiple nucleoporins (Wigington et al. 2019). Overall, these computational methods generate a large “parts list,” and provide a starting point for investigations into new functions for Ca2+ and calcineurin signaling.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF IMMUNOSUPPRESSION WITH CALCINEURIN INHIBITORS SUGGEST UNDISCOVERED SUBSTRATES AND FUNCTIONS

The use of calcineurin inhibitors (i.e., cyclosporin A (CsA) and tacrolimus (FK506)) as immunosuppressants revolutionized the field of organ transplant surgery. In 1983, when CsA was approved for clinical use, the 1-year survival of kidney transplant patients immediately increased from 50% to 80% (Kahan 1999). In 1994, the more potent FK506 was introduced, and these natural products remain the most commonly prescribed immunosuppressants today, including treatments for autoimmune disorders such as acute psoriasis. Both act by forming a complex with an intracellular immunophilin protein (cyclophilin or FKBP, respectively), which subsequently inhibits calcineurin and blocks the adaptive immune response by preventing dephosphorylation of NFAT transcription factors in T cells (Liu et al. 1991). However, improved patient survival has also led to chronic treatment with calcineurin inhibitors, which results in many adverse effects. Hypertension, new-onset diabetes, and neurologic complications commonly occur, likely because of inhibition of calcineurin in nonimmune tissues (although some differences between CysA and FK506 are attributed to noncalcineurin effects). Although disruption of calcineurin/NFAT signaling may contribute to some of these effects, many of the processes affected have no direct connection to known NFAT targets. Rather, these studies highlight the many functions that calcineurin serves throughout the body, and the need to identify physiologically relevant substrates that mediate these responses.

Kidney Dysfunction and Hypertension

Calcineurin inhibitor-induced hypertension is characterized by vasoconstriction as well as sodium and fluid retention and is likely caused by multiple effects on the nervous system, vasculature, and kidney (Hoorn et al. 2012). The clearest connection is between calcineurin inhibitors and the activity of the Na/Cl cotransporter (NCC), product of the SLC12A3 gene, which functions in the distal convoluted tubule portion of the kidney. Ellison and colleagues leveraged similarities between familial hyperkalemic hypertension (FHHt), a rare genetic disorder, and calcineurin inhibitor-induced hypertension, as a rationale to investigate regulation of NCC by calcineurin (Hoorn et al. 2011). Indeed, FK506 increases NCC phosphorylation, fails to induce hypertension in SLC12A3 knockout mice, and evokes an exacerbated hypertensive response in mice that overexpress this gene. Thus, NCC regulation is calcineurin-dependent, but whether calcineurin acts directly on the transporter or through other regulators such as WNK/SPAK kinases that are upstream regulators of this transporter is as yet unclear (Hoorn et al. 2012). Calcineurin inhibitors also activate NKCC2, the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter in the thick ascending limb of the kidney, but this effect is apparently mediated by arginine vasopressin (AVP) signaling (Blankenstein et al. 2017), consistent with other findings that calcineurin inhibitors alter endocrine signaling (i.e., vasopressin and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system) (Lassila 2002). Calcineurin inhibitors may also inhibit vasodilation induced by nitric oxide (NO), as calcineurin has been shown to regulate NO synthase activity and expression in endothelial cells (Kou et al. 2002; Yuan et al. 2016). These drugs also induce endothelial damage and inflammation, an effect that is mediated by signaling through TLR4, a key component of the innate immune response (Rodrigues-Diez et al. 2016). Finally, acute induction of hypertension by CsA may be mediated by renal sensory nerves, which also regulate arterial pressure and sodium levels (Kopp 2015). Synapsin, a calcineurin substrate (Chi et al. 2003) that is present in microvesicles in renal sensory nerve terminals may mediate this effect, as knockout of synapsin I and II significantly reduce acute induction of hypertension by CsA in mice (Zhang et al. 2000). In summary, calcineurin inhibitors likely disrupt kidney function through complex effects on the vascular and nervous systems as well as the kidney itself, and by disrupting regulation of multiple targets by calcineurin.

Diabetes

New-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT) is a frequent complication occurring in almost 30% of patients after kidney transplantation, resulting in increased risk of organ rejection and detrimental quality of life. Numerous studies have implicated calcineurin inhibitors as a cause of NODAT (Chakkera and Mandarino 2013). The underlying physiological problems underlying NODAT appear to be enhanced apoptosis of pancreatic β cells (the predominant insulin producing cells in the islets of Langerhans) resulting in reduced insulin secretion. Calcineurin-mediated signaling has been shown to regulate pancreatic β-cell growth and function. In fact, deletion of the regulatory subunit CN-B from pancreatic β cells in adult mice results in decreased cell mass, reduced insulin biosynthesis, and age-dependent development of diabetes, effects that are improved by expression of active NFATc1 (Heit et al. 2006). Further, a similar deletion in neonatal islets resulted in severely defective β-cell proliferation and lethal diabetes (Goodyer et al. 2012). However, other studies suggest more complex effects of calcineurin on insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. Insulin release from pancreatic β cells is regulated by Ca2+ and cAMP signaling, and loss of AKAP79/150, the plasma membrane-localized anchor that localizes PKA and calcineurin, decreases insulin secretion from β cells but increases glucose sensitivity of muscle, a key tissue for glucose uptake (Hinke et al. 2012). These effects are recapitulated by disruption of the PxIxIT motif in AKAP79/150, showing that calcineurin signaling regulates diverse aspects of glucose handling. Calcineurin also affects sensing of the physiological range of glucose concentrations in β cells. Glucose metabolism enhances intracellular Ca2+ levels leading to activation of the ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and calcineurin. Calcineurin acts on at least two proteins involved in this pathway, B-Raf and KSR2. Calcineurin dephosphorylates B-Raf, an upstream kinase in the ERK1/2 pathway, to relieve negative feedback and promote ERK pathway function (Duan and Cobb 2010). The KSR2 scaffolding protein is also dephosphorylated by calcineurin in response to Ca2+ signals to activate the ERK pathway (Dougherty et al. 2009). In fact, deletion of KSR2 in mice causes increased insulin levels and obesity, and human mutations in this gene similarly cause decreased glucose and fatty acid oxidation, severe insulin resistance and obesity (Pearce et al. 2013). These mutations include R397H, the terminal residue of an LxVP motif, 391NTLSVPR397 (Dougherty et al. 2009). Thus, calcineurin inhibitors may disrupt ERK1/2 signaling, which could also alter glucose homeostasis. In summary, the multiple roles for calcineurin suggest that the underlying etiologies of NODAT are likely complex and involve several sites of action.

Neurologic Toxicities

Use of calcineurin inhibition is associated with a wide range of neurotoxicities, which is consistent with the high concentration of calcineurin in many regions of the brain and its well-documented effects on synaptic transmission and plasticity that underlie demonstrated roles for calcineurin in learning and memory (reviewed in Tarasova et al. 2018). These include dephosphorylation of synaptic vesicle proteins to regulate endocytosis and recycling of synaptic vesicles, as well as modulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor activity and cell-surface expression. Multiple ion channels with critical functions in the nervous system including TRPV1, the Cav1.2 subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel, and TRESK, the inwardly rectifying two pore K+ channel, are also known substrates of calcineurin (Mohapatra and Nau 2005; Czirják and Enyedi 2006; Oliveria et al. 2007). However, etiologies of the common neurotoxic effects of calcineurin inhibitors are not well understood. Calcineurin inhibitors frequently induce posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), which is marked by cortical and subcortical edema and can cause headaches, confusion, visual impairment, and seizures in patients (Chen et al. 2016). PRES induced by calcineurin inhibitors may be a result of hypertension (see above). However, calcineurin inhibitors also compromise the blood–brain barrier, which is also thought to contribute to PRES and may be the result of altered signaling by adrenomedullin, a peptide hormone that improves epithelial barrier function (Dohgu et al. 2010) and/or apoptosis of brain capillary endothelial cells (Kochi et al. 2000). The seizures induced by calcineurin inhibitors may be related to those caused by inherited mutations in PPP3CA, which inactivate the enzyme and cause an early onset form of epilepsy termed West syndrome (Myers et al. 2017; Mizuguchi et al. 2018; Rydzanicz et al. 2019). How calcineurin deficiency causes epilepsy is unknown, but mutations in several genes involved in synaptic vesicle endocytosis, including the calcineurin substrate Dynamin I, also cause epilepsy, suggesting that this function of calcineurin may be critical.

Calcineurin inhibitors also cause a pain syndrome termed CNIPS (calcineurin inhibitor-induced pain syndrome) characterized by symmetric pain in the lower extremities including foot, ankle, and knee bones (Prommer 2012). Although the etiology of this syndrome is unknown, calcineurin does have documented roles in nociception. Calcineurin dephosphorylates and activates TRESK, promoting the return of neurons to baseline after signaling, and suggesting a mechanism for calcineurin inhibitors to induce hyperexcitability that would result in pain. Calcineurin also regulates TRPV1, NMDA, and γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) receptors (Tarasova et al. 2018), and rats treated with calcineurin inhibitors showed increased pre- and postsynaptic NMDA receptor activity in spinal cords, producing pain hypersensitivity that was reduced with an NMDA receptor inhibitor (Chen et al. 2014). Finally, increased vascular tone caused by calcineurin inhibitors might also contribute to CNIPS.

A somewhat surprising benefit of long-term treatment with calcineurin inhibitors may be decreased susceptibility to Alzheimer's disease, as suggested by a retrospective patient study (Taglialatela et al. 2015). This finding, although somewhat preliminary, is consistent with animal studies showing that calcineurin inhibitors improve learning and memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer's and block the toxic effects of introduced Aβ amyloid oligomers into normal mice (Dineley et al. 2007, 2010; Taglialatela et al. 2015). All of these findings are consistent with an emerging model of Alzheimer's implicating dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling as a key, causative factor in pathology of the disease (Popugaeva et al. 2017).

In summary, the long-term use of calcineurin inhibitors as immunosuppressants has provided a wealth of data about the consequences of calcineurin inhibition in humans. However, molecular events underlying many of these clinical effects have not been elucidated, and only ∼75 human proteins have been clearly attributed as calcineurin substrates. New studies of calcineurin structure, its mechanisms of activation and inactivation, and investigations of its splice isoforms have revealed the critical role of SLiMs in substrate recognition by this and other phosphatases (Brautigan and Shenolikar 2018). Novel SLiM-directed approaches are revolutionizing methods for calcineurin substrate identification and will undoubtedly reveal novel functions for this enzyme and thus Ca2+ signaling. Calcineurin inhibitors are still in wide clinical use, and remain some of the most effective treatments available for suppression of the adaptive immune response despite their significant negative consequences. Advancing our understanding of calcineurin signaling throughout the human body is a critical step toward elucidating the effects of calcineurin inhibitors in patients, and for developing therapeutic strategies to combat their toxicities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.R. and M.S.C. are supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01GM119336. We thank Devin Bradburn, Idil Ulengin-Talkish, and Callie Wigington for useful discussion and critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Editors: Geert Bultynck, Martin D. Bootman, Michael J. Berridge, and Grace E. Stutzmann

Additional Perspectives on Calcium Signaling available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Aitken A, Cohen P, Santikarn S, Williams DH, Calder AG, Smith A, Klee CB. 1982. Identification of the NH2-terminal blocking group of calcineurin B as myristic acid. FEBS Lett 150: 314–318. 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80759-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvaro CG, O'Donnell AF, Prosser DC, Augustine AA, Goldman A, Brodsky JL, Cyert MS, Wendland B, Thorner J. 2014. Specific α-arrestins negatively regulate Saccharomyces cerevisiae pheromone response by down-modulating the G-protein-coupled receptor Ste2. Mol Cell Biol 34: 2660–2681. 10.1128/MCB.00230-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu J, García-Cózar F, Raghavan A, Okamura H, Rao A, Hogan PG. 1998. Selective inhibition of NFAT activation by a peptide spanning the calcineurin targeting site of NFAT. Mol Cell 1: 627–637. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80063-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu J, Yaffe MB, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Cantley LC, Hogan PG, Rao A. 1999. Affinity-driven peptide selection of an NFAT inhibitor more selective than cyclosporin A. Science 285: 2129–2133. 10.1126/science.285.5436.2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu J, Rao A, Klee CB. 2000. Calcineurin: From structure to function. Curr Top Cell Regul 36: 237–295. 10.1016/S0070-2137(01)80011-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault HE, Roy J, Mapa CE, Cyert MS, Benanti JA. 2015. Hcm1 integrates signals from Cdk1 and calcineurin to control cell proliferation. Mol Biol Cell 26: 3570–3577. 10.1091/mbc.E15-07-0469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenstein KI, Borschewski A, Labes R, Paliege A, Boldt C, McCormick JA, Ellison DH, Bader M, Bachmann S, Mutig K. 2017. Calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine A activates renal Na-K-Cl cotransporters via local and systemic mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F489–F501. 10.1152/ajprenal.00575.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond R, Ly N, Cyert MS. 2017. The unique C terminus of the calcineurin isoform CNAβ1 confers non-canonical regulation of enzyme activity by Ca2+ and calmodulin. J Biol Chem 292: 16709–16721. 10.1074/jbc.M117.795146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigan DL, Shenolikar S. 2018. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases: Keys to unlocking regulators and substrates. Annu Rev Biochem 87: 921–964. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinegar AE, Xia Z, Loehr JA, Li W, Rodney GG, Cooper TA. 2017. Extensive alternative splicing transitions during postnatal skeletal muscle development are required for calcium handling functions. eLife 6: e27192 10.7554/eLife.27192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakkera HA, Mandarino LJ. 2013. Calcineurin inhibition and new-onset diabetes mellitus after transplantation. Transplantation 95: 647–652. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826e592e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SR, Hu YM, Chen H, Pan HL. 2014. Calcineurin inhibitor induces pain hypersensitivity by potentiating pre- and postsynaptic NMDA receptor activity in spinal cords. J Physiol 592: 215–227. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.263814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Hu J, Xu L, Brandon D, Yu J, Zhang J. 2016. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome after transplantation: A review. Mol Neurobiol 53: 6897–6909. 10.1007/s12035-015-9560-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi P, Greengard P, Ryan TA. 2003. Synaptic vesicle mobilization is regulated by distinct synapsin I phosphorylation pathways at different frequencies. Neuron 38: 69–78. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00151-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Enyedi P. 2006. Targeting of calcineurin to an NFAT-like docking site is required for the calcium-dependent activation of the background K+ channel, TRESK. J Biol Chem 281: 14677–14682. 10.1074/jbc.M602495200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daane JM, Lanni J, Rothenberg I, Seebohm G, Higdon CW, Johnson SL, Harris MP. 2018. Bioelectric-calcineurin signaling module regulates allometric growth and size of the zebrafish fin. Sci Rep 8: 10391 10.1038/s41598-018-28450-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Middei S, Marchetti C, Pacioni S, Ferri A, Diamantini A, De Zio D, Carrara P, Battistini L, et al. 2011. Caspase-3 triggers early synaptic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci 14: 69–76. 10.1038/nn.2709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey NE, Cyert MS, Moses AM. 2015. Short linear motifs–ex nihilo evolution of protein regulation. Cell Commun Signal 13: 43 10.1186/s12964-015-0120-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley KT, Hogan D, Zhang WR, Taglialatela G. 2007. Acute inhibition of calcineurin restores associative learning and memory in Tg2576 APP transgenic mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem 88: 217–224. 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley KT, Kayed R, Neugebauer V, Fu Y, Zhang W, Reese LC, Taglialatela G. 2010. Amyloid-β oligomers impair fear conditioned memory in a calcineurin-dependent fashion in mice. J Neurosci Res 88: 2923–2932. 10.1002/jnr.22445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohgu S, Sumi N, Nishioku T, Takata F, Watanabe T, Naito M, Shuto H, Yamauchi A, Kataoka Y. 2010. Cyclosporin A induces hyperpermeability of the blood–brain barrier by inhibiting autocrine adrenomedullin-mediated up-regulation of endothelial barrier function. Eur J Pharmacol 644: 5–9. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty MK, Ritt DA, Zhou M, Specht SI, Monson DM, Veenstra TD, Morrison DK. 2009. KSR2 is a calcineurin substrate that promotes ERK cascade activation in response to calcium signals. Mol Cell 34: 652–662. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Cobb MH. 2010. Calcineurin increases glucose activation of ERK1/2 by reversing negative feedback. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 22314–22319. 10.1073/pnas.1016630108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap TB, Cook EC, Rumi-Masante J, Arvin HG, Lester TE, Creamer TP. 2013. The distal helix in the regulatory domain of calcineurin is important for domain stability and enzyme function. Biochemistry 52: 8643–8651. 10.1021/bi400483a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felkin LE, Narita T, Germack R, Shintani Y, Takahashi K, Sarathchandra P, López-Olañeta MM, Gómez-Salinero JM, Suzuki K, Barton PJ, et al. 2011. Calcineurin splicing variant calcineurin Aβ1 improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction without inducing hypertrophy. Circulation 123: 2838–2847. 10.1161/circulationaha.110.012211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson ES, Woolfrey KM, Li H, Hogan PG, Nemenoff RA, Heasley LE, Dell'Acqua ML. 2019. Subcellular localization and activity of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MKK7) γ isoform are regulated through binding to the phosphatase calcineurin. Mol Pharmacol 95: 20–32. 10.1124/mol.118.113159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Abe KT, Raught B. 2019. Getting to know the neighborhood: Using proximity-dependent biotinylation to characterize protein complexes and map organelles. Curr Opin Chem Biol 48: 44–54. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman A, Roy J, Bodenmiller B, Wanka S, Landry CR, Aebersold R, Cyert MS. 2014. The calcineurin signaling network evolves via conserved kinase-phosphatase modules that transcend substrate identity. Mol Cell 55: 422–435. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Salinero JM, López-Olañeta MM, Ortiz-Sánchez P, Larrasa-Alonso J, Gatto A, Felkin LE, Barton PJR, Navarro-Lérida I, Ángel Del Pozo M, García-Pavía P, et al. 2016. The calcineurin variant CnAβ1 controls mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation by directing mTORC2 membrane localization and activation. Cell Chem Biol 23: 1372–1382. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer WR, Gu X, Liu Y, Bottino R, Crabtree GR, Kim SK. 2012. Neonatal β cell development in mice and humans is regulated by calcineurin/NFAT. Dev Cell 23: 21–34. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JP, Kim JL, Kim EE, Sintchak MD, Thomson JA, Fitzgibbon MJ, Fleming MA, Caron PR, Hsiao K, Navia MA. 1995. X-ray structure of calcineurin inhibited by the immunophilin-immunosuppressant FKBP12-FK506 complex. Cell 82: 507–522. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90439-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriu S, Bond R, Cossio P, Chen JA, Ly N, Hummer G, Page R, Cyert MS, Peti W. 2013. The molecular mechanism of substrate engagement and immunosuppressant inhibition of calcineurin. PLoS Biol 11: e1001492 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiney EL, Goldman AR, Elias JE, Cyert MS. 2015. Calcineurin regulates the yeast synaptojanin Inp53/Sjl3 during membrane stress. Mol Biol Cell 26: 769–785. 10.1091/mbc.E14-05-1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, Perrino BA, Soderling TR. 1990. Identification of an autoinhibitory domain in calcineurin. J Biol Chem 265: 1924–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano A, Matsumoto M, Nakayama KI. 2016. Phosphoproteomics analyses show subnetwork systems in T-cell receptor signaling. Genes Cells 21: 1095–1112. 10.1111/gtc.12406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JJ, Apelqvist AA, Gu X, Winslow MM, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR, Kim SK. 2006. Calcineurin/NFAT signalling regulates pancreatic β-cell growth and function. Nature 443: 345–349. 10.1038/nature05097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinke SA, Navedo MF, Ulman A, Whiting JL, Nygren PJ, Tian G, Jimenez-Caliani AJ, Langeberg LK, Cirulli V, Tengholm A, et al. 2012. Anchored phosphatases modulate glucose homeostasis. EMBO J 31: 3991–4004. 10.1038/emboj.2012.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn EJ, Walsh SB, McCormick JA, Furstenberg A, Yang CL, Roeschel T, Paliege A, Howie AJ, Conley J, Bachmann S, et al. 2011. The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus activates the renal sodium chloride cotransporter to cause hypertension. Nat Med 17: 1304–1309. 10.1038/nm.2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn EJ, Walsh SB, McCormick JA, Zietse R, Unwin RJ, Ellison DH. 2012. Pathogenesis of calcineurin inhibitor-induced hypertension. J Nephrol 25: 269–275. 10.5301/jn.5000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttlin EL, Bruckner RJ, Paulo JA, Cannon JR, Ting L, Baltier K, Colby G, Gebreab F, Gygi MP, Parzen H, et al. 2017. Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature 545: 505–509. 10.1038/nature22366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Harrison SC. 2002. Crystal structure of human calcineurin complexed with cyclosporin A and human cyclophilin. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 13522–13526. 10.1073/pnas.212504399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvvadi PR, Lamoth F, Steinbach WJ. 2014. Calcineurin-mediated regulation of hyphal growth, septation, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycopathologia 178: 341–348. 10.1007/s11046-014-9794-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahan BD. 1999. Cyclosporine: A revolution in transplantation. Transplant Proc 31: 14S–15S. 10.1016/S0041-1345(98)02074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Lee YI, Seo M, Kim SY, Lee JE, Youn HD, Kim YS, Juhnn YS. 2009. Calcineurin dephosphorylates glycogen synthase kinase-3 β at serine-9 in neuroblast-derived cells. J Neurochem 111: 344–354. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06318.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger CR, Parge HE, Knighton DR, Lewis CT, Pelletier LA, Tempczyk A, Kalish VJ, Tucker KD, Showalter RE, Moomaw EW, et al. 1995. Crystal structures of human calcineurin and the human FKBP12-FK506-calcineurin complex. Nature 378: 641–644. 10.1038/378641a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee CB, Draetta GF, Hubbard MJ. 1988. Calcineurin. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol 61: 149–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochi S, Takanaga H, Matsuo H, Ohtani H, Naito M, Tsuruo T, Sawada Y. 2000. Induction of apoptosis in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and tacrolimus. Life Sci 66: 2255–2260. 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00554-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp UC. 2015. Role of renal sensory nerves in physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308: R79–R95. 10.1152/ajpregu.00351.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou R, Greif D, Michel T. 2002. Dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by vascular endothelial growth factor. Implications for the vascular responses to cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem 277: 29669–29673. 10.1074/jbc.M204519200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystkowiak I, Manguy J, Davey NE. 2018. PSSMSearch: A server for modeling, visualization, proteome-wide discovery and annotation of protein motif specificity determinants. Nucleic Acids Res 46: W235–W241. 10.1093/nar/gky426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Pezzi E, Winn N, Paul A, McCullagh K, Slominsky E, Santini MP, Mourkioti F, Sarathchandra P, Fukushima S, Suzuki K, et al. 2007. A naturally occurring calcineurin variant inhibits FoxO activity and enhances skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Biol 179: 1205–1218. 10.1083/jcb.200704179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassila M. 2002. Interaction of cyclosporine A and the renin-angiotensin system; New perspectives. Curr Drug Metab 3: 61–71. 10.2174/1389200023337964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JI, Mukherjee S, Yoon KH, Dwivedi M, Bandyopadhyay J. 2013. The multiple faces of calcineurin signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans: Development, behaviour and aging. J Biosci 38: 417–431. 10.1007/s12038-013-9319-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rao A, Hogan PG. 2004. Structural delineation of the calcineurin-NFAT interaction and its parallels to PP1 targeting interactions. J Mol Biol 342: 1659–1674. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhang L, Rao A, Harrison SC, Hogan PG. 2007. Structure of calcineurin in complex with PVIVIT peptide: Portrait of a low-affinity signalling interaction. J Mol Biol 369: 1296–1306. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rao A, Hogan PG. 2011. Interaction of calcineurin with substrates and targeting proteins. Trends Cell Biol 21: 91–103. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Pink MD, Murphy JG, Stein A, Dell'Acqua ML, Hogan PG. 2012. Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19: 337–345. 10.1038/nsmb.2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wilmanns M, Thornton J, Kohn M. 2013. Elucidating human phosphatase-substrate networks. Sci Signal 6: rs10 10.1126/scisignal.6306er10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Wang J, Ma L, Lu C, Wang J, Wu JW, Wang ZX. 2016. Cooperative autoinhibition and multi-level activation mechanisms of calcineurin. Cell Res 26: 336–349. 10.1038/cr.2016.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD Jr, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. 1991. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell 66: 807–815. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wilkins BJ, Lee YJ, Ichijo H, Molkentin JD. 2006. Direct interaction and reciprocal regulation between ASK1 and calcineurin-NFAT control cardiomyocyte death and growth. Mol Cell Biol 26: 3785–3797. 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3785-3797.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Hou Y, Liu W, Lu C, Wang W, Sun S. 2015. Components of the calcium-calcineurin signaling pathway in fungal cells and their potential as antifungal targets. Eukaryot Cell 14: 324–334. 10.1128/EC.00271-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly N, Cyert MS. 2017. Calcineurin, the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase, regulates Rga2, a Cdc42 GTPase-activating protein, to modulate pheromone signaling. Mol Biol Cell 28: 576–586. 10.1091/mbc.e16-06-0432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Martínez S, Rodríguez A, López-Maderuelo MD, Ortega-Pérez I, Vázquez J, Redondo JM. 2006. Blockade of NFAT activation by the second calcineurin binding site. J Biol Chem 281: 6227–6235. 10.1074/jbc.M513885200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsoukas MT, Aranguren-Ibáñez A, Lozano T, Nunes V, Lasarte JJ, Pardo L, Pérez-Riba M. 2015. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of calcineurin-NFATc signaling that mimic the PxIxIT motif of calcineurin binding partners. Sci Signal 8: ra63 10.1126/scisignal.2005918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Li H, Hogan PG, Cunningham KW. 2009. Domain architecture of the regulators of calcineurin (RCANs) and identification of a divergent RCAN in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2777–2793. 10.1128/MCB.01197-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi T, Nakashima M, Kato M, Okamoto N, Kurahashi H, Ekhilevitch N, Shiina M, Nishimura G, Shibata T, Matsuo M, et al. 2018. Loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in PPP3CA cause two distinct disorders. Hum Mol Genet 27: 1421–1433. 10.1093/hmg/ddy052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra DP, Nau C. 2005. Regulation of Ca2+-dependent desensitization in the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 by calcineurin and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 280: 13424–13432. 10.1074/jbc.M410917200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrowka R, Patzak A, Herzel H. 2001. Is there a bias in proteome research? Genome Res 11: 1971–1973. 10.1101/gr.206701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukerjee N, McGinnis KM, Gnegy ME, Wang KK. 2001. Caspase-mediated calcineurin activation contributes to IL-2 release during T cell activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 285: 1192–1199. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MR, Sasaki Y, Stevanovic I, Lamperti ED, Ghosh S, Sharma S, Gelinas C, Rossi DJ, Pipkin ME, Rajewsky K, et al. 2009. Requirement for balanced Ca/NFAT signaling in hematopoietic and embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 7034–7039. 10.1073/pnas.0813296106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Sanderson JL, Gorski JA, Scott JD, Catterall WA, Sather WA, Dell'Acqua ML. 2014. AKAP-anchored PKA maintains neuronal L-type calcium channel activity and NFAT transcriptional signaling. Cell Rep 7: 1577–1588. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CT, Stong N, Mountier EI, Helbig KL, Freytag S, Sullivan JE, Ben Zeev B, Nissenkorn A, Tzadok M, Heimer G, et al. 2017. De novo mutations in PPP3CA cause severe neurodevelopmental disease with seizures. Am J Hum Genet 101: 516–524. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Katagiri T, Sato S, Kushibiki T, Hontani K, Tsuchikawa T, Hirano S, Nakamura Y. 2017. Overexpression of C16orf74 is involved in aggressive pancreatic cancers. Oncotarget 8: 50460–50475. 10.18632/oncotarget.10912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namgaladze D, Shcherbyna I, Kienhofer J, Höfer HW, Ullrich V. 2005. Superoxide targets calcineurin signaling in vascular endothelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334: 1061–1067. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HQ, Roy J, Harink B, Damle N, Baxter B, Brower K, Kortemme T, Thorn K, Cyert MS, Fordyce PM. 2018. Quantitative mapping of protein-peptide affinity landscapes using spectrally encoded beads. bioRxiv 10.1101/306779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren PJ, Scott JD. 2016. Regulation of the phosphatase PP2B by protein–protein interactions. Biochem Soc Trans 44: 1313–1319. 10.1042/BST20160150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell AF, Apffel A, Gardner RG, Cyert MS. 2010. α-Arrestins Aly1 and Aly2 regulate intracellular trafficking in response to nutrient signaling. Mol Biol Cell 21: 3552–3566. 10.1091/mbc.e10-07-0636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveria SF, Dell'Acqua ML, Sather WA. 2007. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron 55: 261–275. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padrón-Barthe L, Villalba-Orero M, Gómez-Salinero JM, Acín-Pérez R, Cogliati S, López-Olañeta M, Ortiz-Sánchez P, Bonzón-Kulichenko E, Vazquez J, Garcia-Pavia P, et al. 2018. Activation of serine one-carbon metabolism by calcineurin Aβ1 reduces myocardial hypertrophy and improves ventricular function. J Am Coll Cardiol 71: 654–667. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AS, Saha S, Engelberg K, Jiang RH, Coleman BI, Kosber AL, Chen CT, Ganter M, Espy N, Gilberger TW, et al. 2015. Parasite calcineurin regulates host cell recognition and attachment by apicomplexans. Cell Host Microbe 18: 49–60. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Atanassova N, Banton MC, Bottomley B, van der Klaauw AA, Revelli JP, Hendricks A, Keogh JM, Henning E, Doree D, et al. 2013. KSR2 mutations are associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and impaired cellular fuel oxidation. Cell 155: 765–777. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino BA, Ng LY, Soderling TR. 1995. Calcium regulation of calcineurin phosphatase activity by its B subunit and calmodulin. Role of the autoinhibitory domain. J Biol Chem 270: 340–346. 10.1074/jbc.270.1.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piña FJ, O'Donnell AF, Pagant S, Piao HL, Miller JP, Fields S, Miller EA, Cyert MS. 2011. Hph1 and Hph2 are novel components of the Sec63/Sec62 posttranslational translocation complex that aid in vacuolar proton ATPase biogenesis. Eukaryot Cell 10: 63–71. 10.1128/EC.00241-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popugaeva E, Pchitskaya E, Bezprozvanny I. 2017. Dysregulation of neuronal calcium homeostasis in Alzheimer's disease—A therapeutic opportunity? Biochem Biophys Res Commun 483: 998–1004. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prommer E. 2012. Calcineurin-inhibitor pain syndrome. Clin J Pain 28: 556–559. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31823a67f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Ghosh A. 2008. A calcium-dependent switch in a CREST-BRG1 complex regulates activity-dependent gene expression. Neuron 60: 775–787. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Diez R, González-Guerrero C, Ocaña-Salceda C, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Egido J, Ortiz A, Ruiz-Ortega M, Ramos AM. 2016. Calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine A and tacrolimus induce vascular inflammation and endothelial activation through TLR4 signaling. Sci Rep 6: 27915 10.1038/srep27915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A, Roy J, Martínez-Martínez S, López-Maderuelo MD, Niño-Moreno P, Ortí L, Pantoja-Uceda D, Pineda-Lucena A, Cyert MS, Redondo JM. 2009. A conserved docking surface on calcineurin mediates interaction with substrates and immunosuppressants. Mol Cell 33: 616–626. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J, Cyert MS. 2009. Cracking the phosphatase code: Docking interactions determine substrate specificity. Sci Signal 2: re9 10.1126/scisignal.2100re9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J, Li H, Hogan PG, Cyert MS. 2007. A conserved docking site modulates substrate affinity for calcineurin, signaling output, and in vivo function. Mol Cell 25: 889–901. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumi-Masante J, Rusinga FI, Lester TE, Dunlap TB, Williams TD, Dunker AK, Weis DD, Creamer TP. 2012. Structural basis for activation of calcineurin by calmodulin. J Mol Biol 415: 307–317. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak F, Mertz P. 2000. Calcineurin: Form and function. Physiol Rev 80: 1483–1521. 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzanicz M, Wachowska M, Cook EC, Lisowski P, Kuzniewska B, Szymanska K, Diecke S, Prigione A, Szczaluba K, Szybinska A, et al. 2019. Novel calcineurin A (PPP3CA) variant associated with epilepsy, constitutive enzyme activation and downregulation of protein expression. Eur J Hum Genet. 27: 61–69. 10.1038/s41431-018-0254-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheftic SR, Page R, Peti W. 2016. Investigating the human calcineurin interaction network using the πɸLxVP SLiM. Sci Rep 6: 38920 10.1038/srep38920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Li H, Ou Y, Tao W, Dong A, Kong J, Ji C, Yu S. 2008. The secondary structure of calcineurin regulatory region and conformational change induced by calcium/calmodulin binding. J Biol Chem 283: 11407–11413. 10.1074/jbc.M708513200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer D, Fakata KL, Swanson SA, Stemmer PM. 2000. Modulation of the phosphatase activity of calcineurin by oxidants and antioxidants in vitro. Eur J Biochem 267: 2312–2322. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos AM, Cyert MS. 1997. Calcineurin acts through the CRZ1/TCN1-encoded transcription factor to regulate gene expression in yeast. Genes Dev 11: 3432–3444. 10.1101/gad11.24.3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Denis N, Gupta GD, Lin ZY, Gonzalez-Badillo B, Veri AO, Knight JDR, Rajendran D, Couzens AL, Currie KW, Tkach JM, et al. 2016. Phenotypic and interaction profiling of the human phosphatases identifies diverse mitotic regulators. Cell Rep 17: 2488–2501. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer PM, Klee CB. 1994. Dual calcium ion regulation of calcineurin by calmodulin and calcineurin B. Biochemistry 33: 6859–6866. 10.1021/bi00188a015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stynen B, Tournu H, Tavernier J, Van Dijck P. 2012. Diversity in genetic in vivo methods for protein–protein interaction studies: From the yeast two-hybrid system to the mammalian split-luciferase system. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76: 331–382. 10.1128/MMBR.05021-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell GN, Ivarsson Y. 2014. Interaction analysis through proteomic phage display. Biomed Res Int 2014: 9 10.1155/2014/176172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglialatela G, Rastellini C, Cicalese L. 2015. Reduced incidence of dementia in solid organ transplant patients treated with calcineurin inhibitors. J Alzheimers Dis 47: 329–333. 10.3233/JAD-150065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasova EO, Gaydukov AE, Balezina OP. 2018. Calcineurin and its role in synaptic transmission. Biochemistry (Mosc) 83: 674–689. 10.1134/S0006297918060056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thewes S. 2014. Calcineurin-Crz1 signaling in lower eukaryotes. Eukaryot Cell 13: 694–705. 10.1128/EC.00038-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P, Davey NE, Gibson TJ, Babu MM. 2014. A million peptide motifs for the molecular biologist. Mol Cell 55: 161–169. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosello V, Saccomani V, Yu J, Bordin F, Amadori A, Piovan E. 2016. Calcineurin complex isolated from T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cells identifies new signaling pathways including mTOR/AKT/S6K whose inhibition synergize with calcineurin inhibition to promote T-ALL cell death. Oncotarget 7: 45715–45729. 10.18632/oncotarget.9933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Culotta VC, Klee CB. 1996. Superoxide dismutase protects calcineurin from inactivation. Nature 383: 434–437. 10.1038/383434a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigington C, Roy J, Damle NP, Yadav VK, Blikstad C, Resch E, Wong CJ, Mackay DR, Wang JT, Krystikowiak I, et al. 2019. Systematic discovery of short linear motifs decodes calcineurin phosphatase signaling. bioRxiv 10.1101/632547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Tomizawa K, Matsui H. 2007. Calpain-calcineurin signaling in the pathogenesis of calcium-dependent disorder. Acta Med Okayama 61: 123–137. 10.18926/AMO/32905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, De Wever V, Derua R, Winkler C, Beullens M, Van Eynde A, Bollen M. 2018. A substrate-trapping strategy for protein phosphatase PP1 holoenzymes using hypoactive subunit fusions. J Biol Chem 293: 15152–15162. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin X, Gfeller D, Cheng J, Tonikian R, Sun L, Guo A, Lopez L, Pavlenco A, Akintobi A, Zhang Y, et al. 2013. SH3 interactome conserves general function over specific form. Mol Syst Biol 9: 652 10.1038/msb.2013.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SA, Klee CB. 2000. Low affinity Ca2+-binding sites of calcineurin B mediate conformational changes in calcineurin A. Biochemistry 39: 16147–16154. 10.1021/bi001321q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Yang J, Santulli G, Reiken SR, Wronska A, Kim MM, Osborne BW, Lacampagne A, Yin Y, Marks AR. 2016. Maintenance of normal blood pressure is dependent on IP3R1-mediated regulation of eNOS. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: 8532–8537. 10.1073/pnas.1608859113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Li JL, Hosaka M, Janz R, Shelton JM, Albright GM, Richardson JA, Sudhof TC, Victor RG. 2000. Cyclosporine A-induced hypertension involves synapsin in renal sensory nerve endings. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97: 9765–9770. 10.1073/pnas.170160397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Mester C, Stemmer PM, Reid GE. 2014. Oxidation-induced conformational changes in calcineurin determined by covalent labeling and tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 53: 6754–6765. 10.1021/bi5009744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]