Abstract

Background

Postpartum endometritis occurs when vaginal organisms invade the endometrial cavity during the labor process and cause infection. This is more common following cesarean birth. The condition warrants antibiotic treatment.

Objectives

Systematically, to review treatment failure and other complications of different antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 November 2014) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomized trials of different antibiotic regimens after cesarean birth or vaginal birth; no quasi‐randomized trials were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy.

Main results

The review includes a total of 42 trials, and 40 of these trials contributed data on 4240 participants.

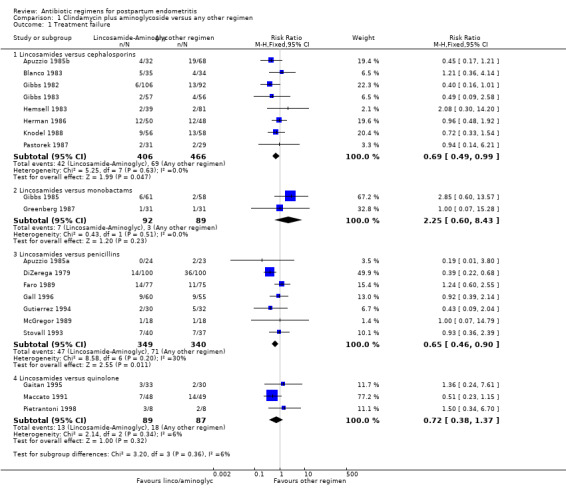

Twenty studies, involving 1918 women, compared clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside (gentamicin for all studies except for one that used tobramycin) with another regimen.

When assessing the individual subgroups of other antibiotic regimens (i.e. cephalosporins, monobactams, penicillins, and quinolones), there were fewer treatment failures in those treated with clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside as compared to those treated with cephalosporins (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.99; participants = 872; studies = 8; low quality evidence) or penicillins (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.90; participants = 689; studies = 7, low quality evidence). For the remaining subgroups for the primary analysis, the differences were not significant. There were significantly fewer wound infections in those treated with clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus cephalosporins (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.93; participants = 500; studies = 4; low quality evidence). Similarly, there were more treatment failures in those treated with an gentamicin/penicillin when compared to those treated with gentamIcin/clindamycin (RR 2.57, 95% CI 1.48 to 4.46; participants = 200; studies = 1).

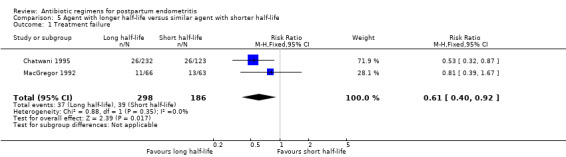

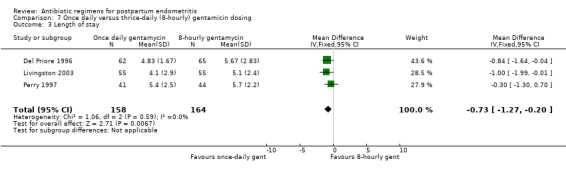

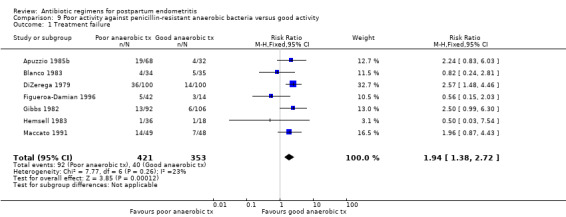

There were fewer treatment failures when an agent with a longer half‐life that is administered less frequently was used (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.92; participants = 484; studies = 2) as compared to using cefoxitin. There were more treatment failures (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.72; participants = 774; studies = 7) and wound infections (RR 1.88, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.02; participants = 740; studies = 6) in those treated with a regimen with poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria as compared to those treated with a regimen with good activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria. Once‐daily dosing was associated with a shorter length of hospital stay (MD ‐0.73, 95% CI ‐1.27 to ‐0.20; participants = 322; studies = 3).

There were no differences between groups with respect to severe complications and no trials reported any maternal deaths.

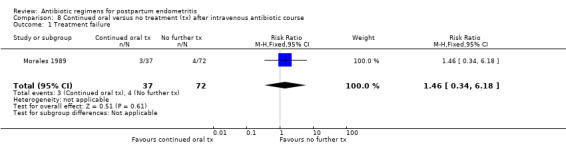

Regarding the secondary outcomes, three studies that compared continued oral antibiotic therapy after intravenous therapy with no oral therapy, found no differences in recurrent endometritis or other outcomes. There were no differences between groups for the outcomes of allergic reactions.

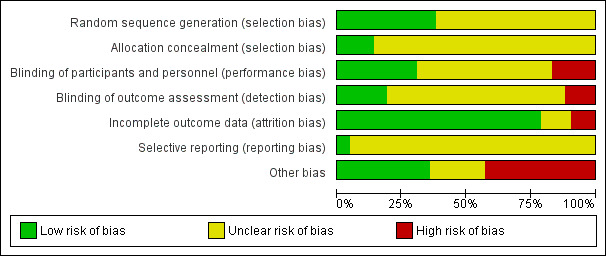

The overall risk of bias was unclear in the most of the studies. The quality of the evidence using GRADE comparing clindamycin and an aminoglycoside with another regimen (compared with cephalosporins or penicillins) was low to very low for therapeutic failure, severe complications, wound infection and allergic reaction.

Authors' conclusions

The combination of clindamycin and gentamicin is appropriate for the treatment of endometritis. Regimens with good activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria are better than those with poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria. There is no evidence that any one regimen is associated with fewer side‐effects. Following clinical improvement of uncomplicated endometritis which has been treated with intravenous therapy, the use of additional oral therapy has not been proven to be beneficial.

Plain language summary

Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis

Intravenous clindamycin plus gentamicin is more effective than other antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics for treatment of womb infection after childbirth.

Inflammation of the lining of the womb (endometritis) can be caused by vaginal bacteria entering the womb (uterus) during childbirth and causing infection within six weeks of the birth (postpartum endometritis). Postpartum endometritis occurs after about 1% to 3% of vaginal births, and up to 27% of cesarean births. Prolonged rupture of the membranes (breaking the bag of water that surrounds the baby) and multiple vaginal examinations during birth also appear to increase the risk.

Endometritis causes fever, tenderness in the pelvic region and unpleasant‐smelling vaginal discharge after the birth. It can have serious complications such as the formation of pelvic abscesses, blood clots, infection of the thin layer of tissue that covers the inside of the abdomen and abdominal organs (peritonitis), and whole body inflammation (sepsis). It is also an important cause of maternal deaths worldwide, although with the use of antibiotics, this is very rare in high‐income countries.

There are many antibiotic treatments currently in use. This review compared different antibiotics, routes of administration and dosages for endometritis. The review identified 42 relevant randomised controlled studies, which are the most reliable type of medical trial for this type of investigation; 40 of these (involving 4240 women) contributed data for analysis.

The results showed that the combination of intravenous gentamicin and clindamycin, and drugs with a broad range of activity against the relevant penicillin‐resistant bacterial strains, are the most effective for treating endometritis after childbirth. Women treated with clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside (gentamicin) showed fewer treatment failures than those treated with penicillin, but this difference was not evident when women treated with clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside were compared to women who received other antibiotic treatments.

There were more treatment failures in women treated with an penicillin plus gentamicin (one study) compared with those treated with clindamycin plus gentamicin. Seven trials showed that an antibiotic treatment that had poor activity against bacteria resistant to penicillin had a higher failure rate and more wound infections than an antibiotic treatment that had good activity against these bacteria.

There was no evidence that any of the antibiotic combinations had fewer adverse effects ‐ including allergic reaction ‐ than other antibiotic combinations. If the endometritis was uncomplicated and improved with intravenous antibiotics, there did not appear to be a need to follow the intravenous antibiotics with a course of oral antibiotics.

Overall the reliability of the studies' results was unclear, the numbers of women studied were often small and data on other outcomes were limited; furthermore, a number of the studies had been funded by drug companies that conceivably would have had a vested interest in the results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen for postpartum endometritis.

| Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus cephalosporins or penicillins for postpartum endometritis | ||||||

| Population: women with postpartum endometritis Settings: hospitals in US, France, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Italy (most studies from USA) Intervention: clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen | |||||

| Treatment failure ‐ lincosamides versus cephalosporins | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.49 to 0.99) | 872 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| 148 per 1000 | 102 per 1000 (73 to 147) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 237 per 1000 | 164 per 1000 (116 to 235) | |||||

| Treatment failure ‐ lincosamides versus penicillins | Study population | RR 0.65 (0.46 to 0.90) | 689 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| 209 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (96 to 188) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 189 per 1000 | 123 per 1000 (87 to 170) | |||||

| Severe complication ‐ lincosamides versus cephalosporins | Study population | RR 2.40 (0.30 to 19.19) | 476 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 4 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (1 to 77) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Severe complication ‐ lincosamides versus penicillins | Study population | RR 0.33 (0.09 to 1.18) | 422 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 38 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (3 to 45) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Wound infection ‐ lincosamides versus cephalosporins | Study population | RR 0.53 (0.3 to 0.93) | 500 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| 114 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (34 to 106) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 121 per 1000 | 64 per 1000 (36 to 113) | |||||

| Wound infection ‐ lincosamides versus penicillins | Study population | RR 0.46 (0.21 to 1) | 339 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 107 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (22 to 107) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 63 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (13 to 63) | |||||

| Allergic reaction ‐ lincosamides versus cephalosporins | Study population | RR 1.36 (0.44 to 4.21) | 680 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (5 to 51) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 14 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (6 to 59) | |||||

| Allergic reaction ‐ lincosamides versus penicillins | Study population | RR 1 (0.14 to 6.96) | 247 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 16 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (2 to 113) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 10 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (1 to 70) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Most studies contributing data had design limitations 2 Small sample size with confidence interval crossing the line of no effect 3 Estimate based on small sample size

Background

Description of the condition

The diagnosis of postpartum endometritis is based on the presence of fever in the absence of any other cause. Uterine tenderness, purulent or foul‐smelling lochia and leukocytosis are common clinical findings used to support the diagnosis of endometritis. The American Committe of Maternal Welfare's standard definition for reporting rates of puerperal morbidity is an "oral temperature of 38.0 degrees centigrade or more on any two of the first 10 days postpartum or 38.7 degrees centigrade or higher during the first 24 hours postpartum". Alternatively, postpartum endometritis has been divided into early‐onset disease occurring within 48 hours postpartum, and late‐onset disease presenting up to six weeks postpartum (Wager 1980; Williams 1995). Endometritis is diagnosed after 1% to 3% of vaginal births; and it is up to 10 times more common after cesarean birth (Calhoun 1995).

Description of the intervention

The pathogenesis of endometritis is related to contamination of the uterine cavity with vaginal organisms during labor and birth and invasion of the myometrium. The presence of certain bacteria (e.g. groups A and B streptococci, aerobic Gram‐negative rods, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma hominis and certain anaerobic bacteria) in amniotic fluid cultures at the time of cesarean birth is associated with an increased risk of postpartum endometritis (Newton 1990). For vaginal births, the presence of the organisms associated with bacterial vaginosis (e.g. certain anaerobic bacteria and Gardnerella vaginalis) or genital cultures positive for aerobic Gram‐negative organisms is associated with an increased risk for endometritis (Newton 1990). Prolonged rupture of membranes and multiple vaginal examinations have also been identified as potential risk factors (Gibbs 1980). Women with bacterial vaginosis in early pregnancy have three times significantly higher risk of postpartum endometritis (Jacobsson 2002).

Endometritis is usually a polymicrobial infection associated with mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora. Bacteremia may be present in 10% to 20% of cases. Unless a specimen is obtained from the upper genital tract without contamination from the vagina, or blood cultures are positive, there is seldom laboratory confirmation of the microbiological etiology of endometritis.

Complications of endometritis include extension of infection to involve the peritoneal cavity with peritonitis, intra‐abdominal abscess, or sepsis. Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, which can be associated with septic pulmonary emboli, can occur rarely as a complication of postpartum endometritis.

How the intervention might work

Before the advent of the antibiotic era, puerperal fever was an important cause of maternal death. With the use of antibiotics, a sharp decrease in maternal morbidity has been observed, and it is now accepted that antibiotic treatment for postpartum endometritis is warranted.

There are many antibiotic treatment regimens currently in use. An empiric regimen active against the mixed aerobic and anaerobic organisms likely to be causing infection is generally selected. Treatment is usually considered successful after the woman is afebrile for 24 to 48 hours. The spectrum of activity of clindamycin with gentamicin makes these antibiotics a popular choice for initial therapy and this combination is widely considered as the gold standard (Monga 1993). However, alternative treatment regimens for endometritis with different antimicrobial activity or pharmacokinetic profiles may be associated with differences in clinical effectiveness, side‐effects or cost.

Why it is important to do this review

Determination of the appropriate antibiotic regimen to treat postpartum endometritis has multiple short and long term ramifications. Appropriate initial treatment may not only decrease maternal morbidity but may also improve antibiotic stewardship.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine, from the best evidence available, the effect of different antibiotic regimens for the treatment of postpartum endometritis on the rate of therapeutic failure, the duration of fever, the rates of complications, and the rates of side‐effects of treatment. The effects of different drugs, routes of administration, and duration of therapy were sought. In addition, we sought to compare the effectiveness of regimens known to be active against the penicillin‐resistant Bacteroides fragilis group of anaerobic organisms compared with those that are not.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All trials in which the authors described random allocation (by any method) of participants to different treatment regimens for postpartum endometritis were considered. Cluster‐randomized trials are eligible for inclusion, but we did not consider cross‐over trials suitable for inclusion. We excluded quasi‐randomized and pseudo‐randomized studies.

Types of participants

Women who were diagnosed with endometritis (as defined by the authors of the individual studies) during the first six weeks of the postpartum period.

Types of interventions

We considered trials if a comparison was made between different antibiotic regimens (including, but not limited to, different drug/drugs, different routes of administration, and different durations of therapy). Our main comparison was between clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside (usually gentamicin) versus another regimen. Where appropriate, we grouped different antibiotics with a similar antimicrobial spectrum of activity (e.g. lincosamides plus aminoglycoside versus cephalosporins, monobactams, quinolones, and penicillins).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Treatment failure (as defined by the individual trials);

severe complications (including pelvic abscess and septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis);

maternal death.

Secondary outcomes

We collected data (where available) on the following additional outcome measures:

any change made to the initial antibiotic regimen;

duration of fever;

wound infection (not prespecified);

allergic reactions;

diarrhoea;

superinfection or colonization with resistant organisms;

quantity of resources (e.g. length of stay, amount of drug) utilized;

treatment failure despite administration of prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean (not prespecified);

financial costs;

recurrent endometritis (not prespecified)*;

nephrotoxicity (not prespecified)**.

*For the analysis of continued oral therapy versus no additional therapy after intravenous treatment, we also assessed the outcome of recurrent endometritis. **For the analysis of daily versus thrice‐daily gentamicin, we also assessed the outcome of nephrotoxicity.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 November 2014).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review see French 2004.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search. These methods are based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed all the potential additional studies we identified as a result of the search strategy for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to abstract data. For eligible studies, two review authors abstracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered data into Review Manager software and checked for accuracy (RevMan 2014).

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports for further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as being at:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as being at:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included the missing data in the analyses that we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

For each included study we described any additional concerns regarding other possible sources of bias. For example, a potential source of bias related to the specific study design, or the trial stopped early due to some data‐dependent process, or extreme baseline imbalance, or claimed to be fraudulent.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using GRADE

For this update we used the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following primary and secondary outcomes for the main comparison (i.e. clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus cephalosporins or penicillins):

treatment failures;

severe complications (including pelvic abscess and septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis);

wound infections;

allergic reactions.

We used GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 in order to create 'Summary of findings’ tables (RevMan 2014). We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference where outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardized mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomized trials

In future updates, we will include cluster‐randomized trials in the analyses along with individually randomized trials. We will adjust their sample size using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomized trials and individually‐randomized trials, we plan to synthesize the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomization unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomization unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomization unit.

Other unit of analysis issues

We did not include cross‐over trials. We did not use any special methods for trials with more than one treatment group.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is, we attempted to include all participants randomized to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analyzed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomized minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

As there are more than 10 studies in the meta‐analysis we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry had been suggested by a visual assessment, we would have performed exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect, i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged to be sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful we did not combine trials.

If we used random‐effects analyses, we presented the results as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, with the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did subgroup analyses for class of antibiotics for any other regimens in the comparison group. We classified the class of antibiotics according to the classification in the Gyte 2014 Cochrane review. When referring to penicillins, we included penicillin, ampicillin and extended spectrum penicillins. Monobactam refers to aztreonam. Aminoglycosides typically refer to gentamicin with the exception of one study that used tobramycin (Pastorek 1987). Lincosamides refer to clindamycin. For Analysis 1.1, the regimen typically included clindamycin plus gentamicin. A priori, we had planned subgroup analyses based on the presence of risk factors such as mode of delivery or genital tract infections, if an adequate number of studies were available. We planned a separate sub analysis including only those studies in which all participants had received prophylactic antibiotic treatment during cesarean birth, if an adequate number of studies were available. However, there were not enough studies available to perform the planned subgroup analyses. We also planned to perform sensitivity analyses based on methodological quality if necessary. Given that in all but five of the studies, treatment allocation was inadequately described, we did not perform a sensitivity analysis incorporating allocation concealment as a measure of study quality as this was not appropriate.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We excluded studies from the analysis when more than 20% of participants dropped out or were excluded after randomization. In future updates, we will carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

The clinical criteria listed to define endometritis were consistent across trials. Febrile morbidity is a standard obstetrical outcome and was generally consistently reported, although there was some variation in the exact criteria used for height of fever, interval between febrile episodes and interval from the operative procedure. Urinary tract infection was usually defined as a positive urine culture; symptoms related to the urinary tract were rarely required to be present. Wound infection was diagnosed clinically and generally included induration, erythema, cellulitis or drainage. A positive microbiological diagnosis was rarely required for the diagnosis of either wound infection or endometritis. There was no consistent approach to the definition of serious morbidity. For this review, all episodes of bacteremia have been classified as serious, as have complications such as pelvic thrombophlebitis, pelvic abscess, and peritonitis. Some studies included other outcomes, for example the need for additional antibiotic use and other infections such as pneumonia. Some provided a measure of the fever as a 'fever index' which incorporated both the height of the fever and its duration.

Results of the search

We identified 72 trials. We included 42 (40 of these trials contributed data on 4240 participants), and excluded 30.

Included studies

For a detailed description of included studies, see the table of Characteristics of included studies.

All, but seven studies were conducted in the United States: one was conducted in France, two in Mexico, and one each in Italy, Peru, and Colombia. One study was a multicenter study conducted in many countries, including the United States.

The studies that contributed data to this meta‐analysis compared several different antibiotic regimens. Twenty studies compared clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside (typically gentamicin) with another regimen. Other comparisons included:

an aminoglycoside (gentamicin) plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen;

a beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen;

the combination of aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen;

agents with a long half‐life versus those with a short half‐life;

the combination of metronidazole plus gentamicin versus any other regimen;

once daily versus thrice‐daily dosing of gentamicin;

continued oral therapy versus no therapy after an intravenous antibiotic course;

regimens with good activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobes versus regimens with poor activity (e.g. ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, penicillin or ampicillin and an aminoglycoside, and certain cephalosporins such as cefamandole and ceftazidime) against such organisms;

oral ofloxacin plus intravenous clindamycin versus intravenous clindamycin and intravenous gentamicin.

Twenty studies enrolled only postpartum women who developed endometritis after cesarean birth; in four studies, the mode of delivery was not reported. In the remainder, a variable proportion of cases followed cesarean birth. In women who developed endometritis postcesarean birth there was no consistent approach to the use of prophylactic antibiotics. While four studies excluded women who had received prophylaxis, five others stated that all women had received prophylaxis. Cefazolin was the agent selected when prophylaxis was given except in one study in which cefoxitin was used (Tuomala 1989). Although women who developed endometritis during the first six weeks of the postpartum period were eligible for inclusion in this review, the vast majority appeared to have been enrolled within 48 hours of birth.

Excluded studies

We excluded 30 studies identified in the search from the analysis for the following reasons:

more than 20% exclusions after randomization (n = 7);

not a study of postpartum endometritis (n = 7);

study not randomized or the method of allocation to treatment was inadequate, e.g. alternation (n = 6);

no clinical outcomes on postpartum women reported or postpartum endometritis not defined (n = 4);

actual numbers not provided (n = 4);

different antibiotic regimens not compared (n = 1); or

antibiotic regimen dosing and frequency not described (n = 1).

None of the five studies we identified that compared an extended spectrum penicillin with any other regimen met the methodological criteria for inclusion in this review. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

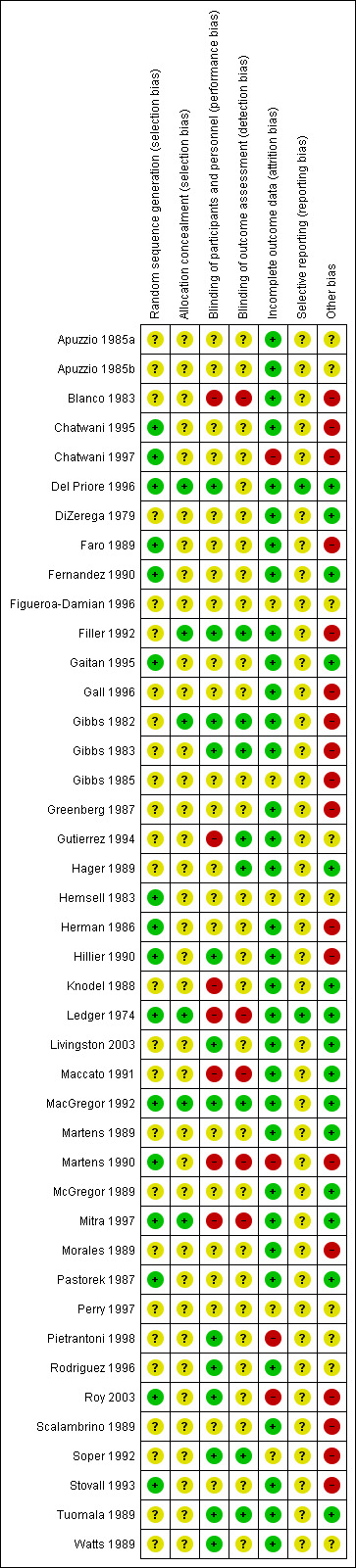

Risk of bias in included studies

For risk of bias for included studies, see the risk of bias tables, Figure 1; and Figure 2. The risk of bias information below pertains only to those studies that contributed data to this meta‐analysis.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

In all of the studies, women were randomly allocated to treatment groups as per the inclusion criteria. Allocation concealment was sufficiently described and considered to be adequate in only five studies (Del Priore 1996; Filler 1992; Gibbs 1982; MacGregor 1992; Mitra 1997). For the remaining studies, the adequacy of allocation of participants to treatment groups was unclear. Although many of these studies did report that a computerized randomization schedule was used, it was unclear how the randomization schedule was actually administered.

Blinding

Blinding was described in only a few studies. Only four studies used placebo doses and, although nine studies reported a 'double‐blind' design, only three studies described how they attempted to ensure the medications appeared similar in appearance (Gibbs 1982; Gibbs 1983; Hillier 1990). One other study stated that interventions were similar in appearance without describing how this was accomplished (MacGregor 1992). Three studies were described as 'single‐blind'. In most trials there was no description of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Since women were usually hospitalized, loss to follow‐up was not a significant problem. When drop‐outs were reported, the reasons why women who had initially been randomized were eventually excluded from the analysis were usually explained. Frequently, however, the number corresponding to each arm of the study was not given. The most frequent reasons given for drop‐outs were protocol violations of various descriptions. For this reason we have provided analysis of available cases (rather than intention‐to‐treat). To reduce the likelihood of bias, we excluded studies in which more than 20% of participants had dropped out or been excluded form the analysis after randomization.

Selective reporting

Only one study had its protocol available, and all of the pre‐specified outcomes were reported (Del Priore 1996). Most of the study protocols were not available and therefore risk of bias was judged to be unclear, due to insufficient information.

Other potential sources of bias

Pharmaceutical sponsorship was evident in 18 studies, which were therefore judged as being at high risk of bias. We judged eight studies to have an unclear additional bias. For three studies we had truncated versions of the original publication that were only partially translated from the initial language (Figueroa‐Damian 1996; Gutierrez 1994; Rodriguez 1996). We suspected that three studies had pharmaceutical sponsorship, but this was not overtly reported (Apuzzio 1985a; Apuzzio 1985b; Hemsell 1983). One study had only an abstract that was available, which could lead to information about potential biases being missed (Perry 1997). One study published what appeared to be preliminary data; neither finalized data nor reasons for failing to complete the study were discovered (Pietrantoni 1998).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

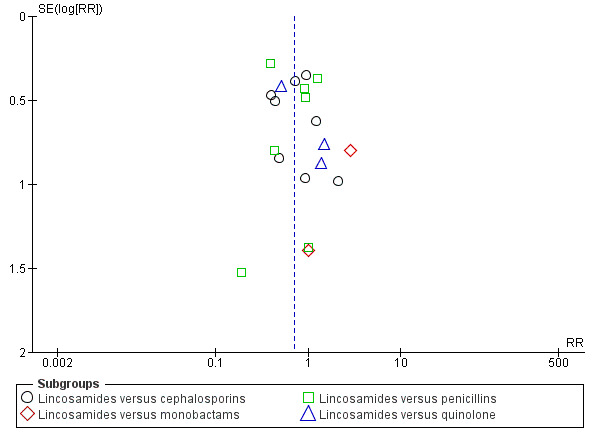

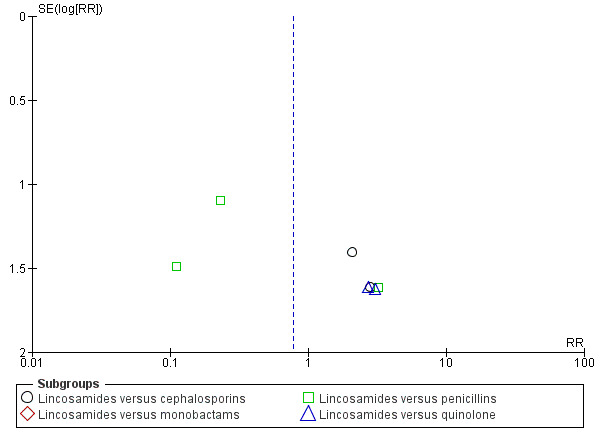

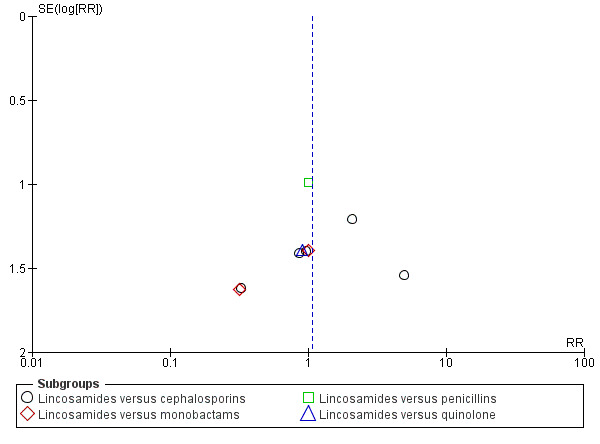

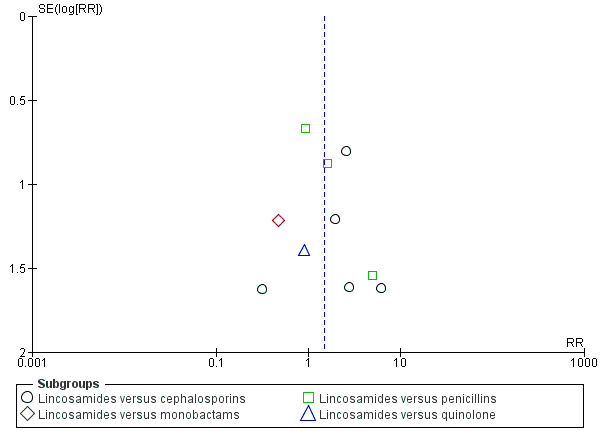

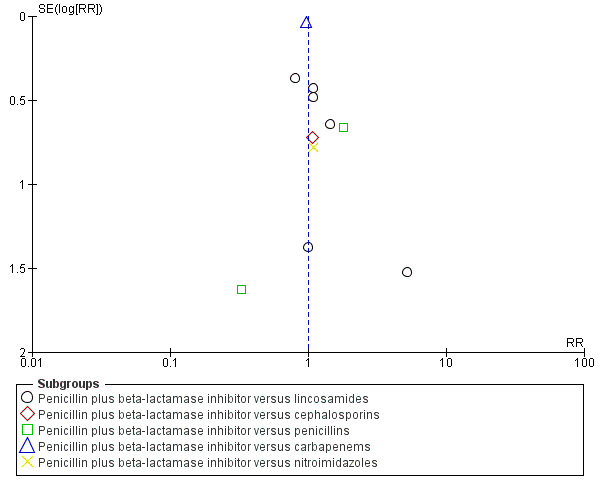

Among all the comparisons reported, there was no evidence that any particular regimen was associated with a different rate of allergic reactions. Despite the large number of trials and different antibiotic regimens, only one comparison revealed statistical heterogeneity (Analysis 2.1); therefore we applied random‐effects analyses. Given that in all but five of the studies, treatment allocation was inadequately described, we did not perform a sensitivity analysis incorporating allocation concealment as a measure of study quality as this was not appropriate. As there were more than 10 trials in certain analyses, we conducted visual inspection of the funnel plots to assess reporting bias. There was no funnel plot asymmetry found in the following analyses: Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 3.1 (Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7).

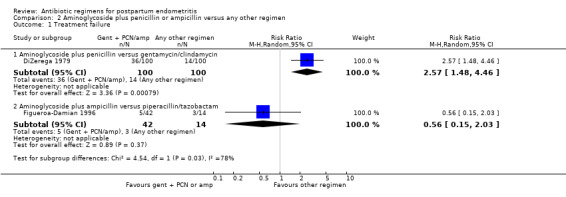

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

1.2. Analysis.

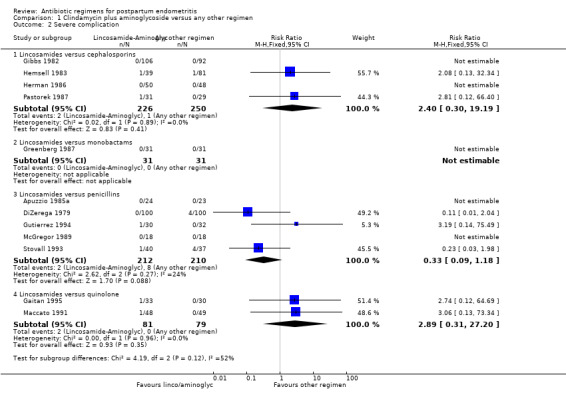

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

1.4. Analysis.

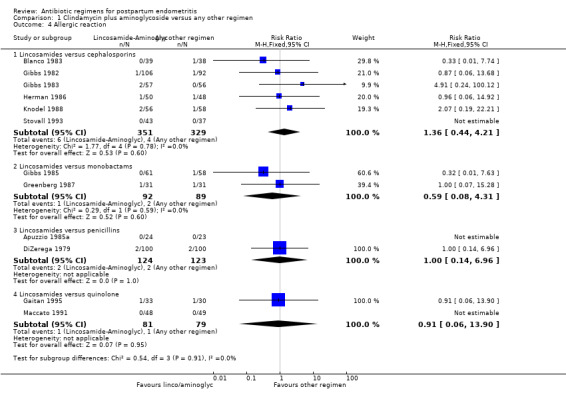

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 4 Allergic reaction.

1.5. Analysis.

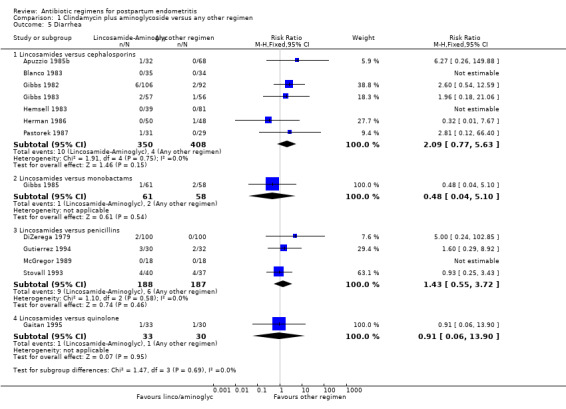

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

3.1. Analysis.

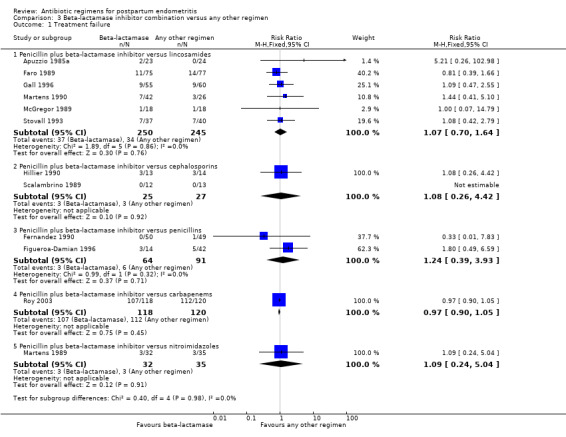

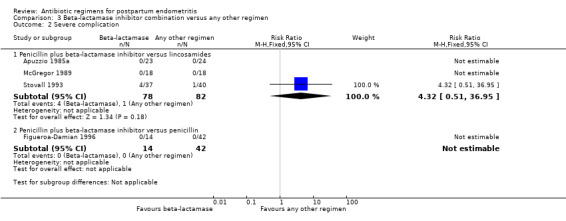

Comparison 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, outcome: 1.1 Treatment failure.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, outcome: 1.2 Severe complication.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, outcome: 1.4 Allergic reaction.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, outcome: 1.5 Diarrhea.

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, outcome: 3.1 Treatment failure.

1. Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen ‐ 20 studies, 1918 women

Twenty studies, involving 1918 women, compared clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside (gentamicin used for all studies except for Pastorek 1987 that used tobramycin) with another regimen (Apuzzio 1985a; Apuzzio 1985b; Blanco 1983; DiZerega 1979; Faro 1989; Gaitan 1995; Gall 1996; Gibbs 1982; Gibbs 1983; Gibbs 1985; Greenberg 1987; Gutierrez 1994; Hemsell 1983; Herman 1986; Knodel 1988; Maccato 1991; McGregor 1989; Pastorek 1987; Pietrantoni 1998; Stovall 1993).

Primary outcomes

When assessing the individual subgroups of other antibiotic regimens (i.e. cephalosporins, monobactams, penicillins, and quinolones), there were fewer treatment failures in those treated with clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside as compared to those treated with cephalosporins (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.99; participants = 872; studies = 8; Analysis 1.1.1) or penicillins (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.90; participants = 689; studies = 7, Analysis 1.1.3). For the remaining subgroups, the differences were not significant.

There were no significant differences between groups with respect to severe complications (Analysis 1.2): lincosamides versus cephalosporins (RR 2.40, 95% CI 0.30 to 19.19; 476 participants; 4 studies; I² 0%, Analysis 1.2.1), lincosamides versus monobactams had only one study with no events (Analysis 1.2.2), lincosamides versus penicillins (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.18; 422 participants; 5 studies; I² 24%, Analysis 1.2.3), lincosamides versus quinolone (RR 2.89, 95% CI 0.31 to 27.20; participants = 160; studies = 2; Analysis 1.2.4).

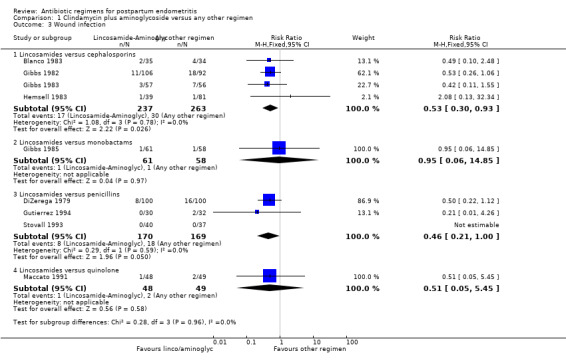

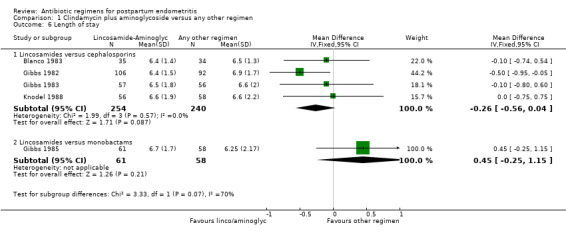

Secondary outcomes

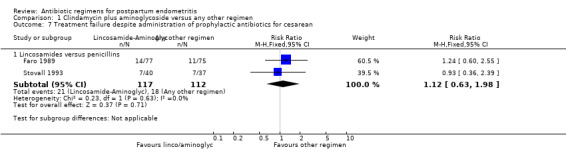

There were significantly fewer wound infections with clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus cephalosporins (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.93; 500 participants; 4 studies, I² 0%, Analysis 1.3,1). There was no statistically significant difference with other comparison subgroup analysis for wound infections with clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus monobactams (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.06 to 14.85; 119 participants; 1 study, Analysis 1.3.2) or penicillins (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.00; 339 participants; 3 studies, Analysis 1.3.3) or quinolone ((RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.45; participants = 97; studies = 1, Analysis 1.3.4). There were no significant differences between lincosamides versus other regimen subgroups with the outcomes of allergic reactions (Analysis 1.4), diarrhea (Analysis 1.5), length of stay (Analysis 1.6) or treatment failure post cesarean with prophylaxis (Analysis 1.7).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 6 Length of stay.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen, Outcome 7 Treatment failure despite administration of prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean.

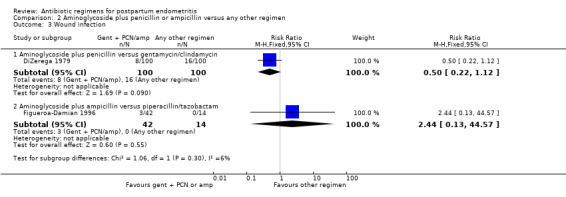

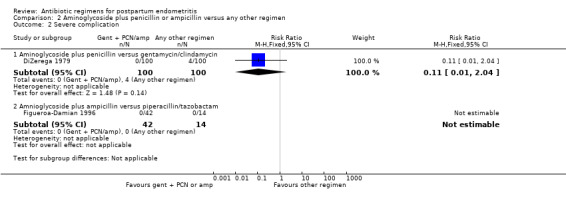

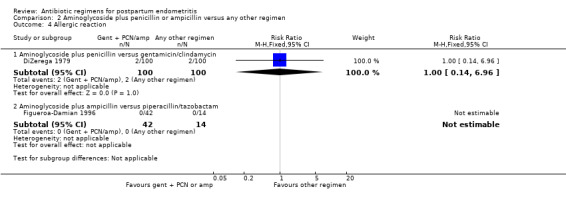

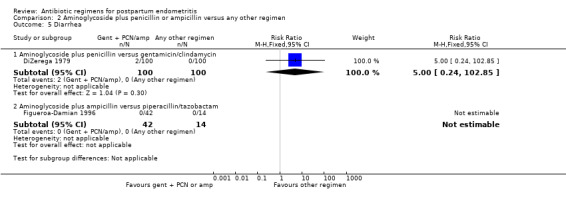

2. Aminoglycoside (specifically gentamicin) plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen ‐ two studies, 256 women

Two trials compared gentamicin plus penicillin or ampicillin with other regimens (DiZerega 1979; Figueroa‐Damian 1996): gentamicin/penicillin versus gentamicin/clindamycin (DiZerega 1979), and gentamicin/ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam (Figueroa‐Damian 1996).

Primary outcomes

There were no significant differences in treatment failures (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.03; 56 participants, Analysis 2.1.2) or wound infection (RR 2.44, 95% CI 0.13 to 44.57; 56 participants; 1 study, Analysis 2.3.2) when comparing gentamicin plus ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam. However, there were significantly more treatment failures for those treated with gentamicin plus penicillin compared to gentamicin plus clindamycin (RR 2.57, 95% CI 1.48 to 4.46; 200 participants, Analysis 2.1).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

There were no significant differences in gentamicin/penicillin versus gentamicin/clindamycin with respect to severe complications (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.04; 200 participants; 1 study; Analysis 2.2.1).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant differences in wound infections (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.12; 200 participants; 1 study, Analysis 2.3.1), allergic reactions (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 6.96; 200 participants; 1 study, Analysis 2.4.1) or diarrhea (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.24 to 102.85; 200 participants; 1 study, Analysis 2.5.1).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen, Outcome 4 Allergic reaction.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

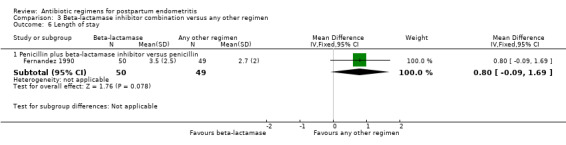

3. Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen ‐ 12 studies, 1007 women

Twelve trials (1007 participants) compared a beta‐lactam/beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination with another regimen.

Primary outcomes

There were no differences in treatment failures in any subgroup; e.g. penicillin plus beta‐lactamase inhibitor versus lincosamides (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.64; participants = 495; studies = 6; I² = 0%, , Analysis 3.1) as well as no difference in severe complication (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.04, Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

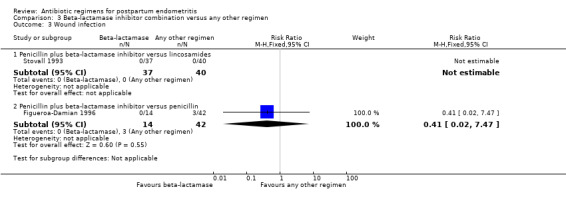

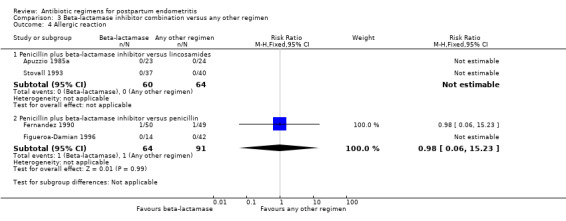

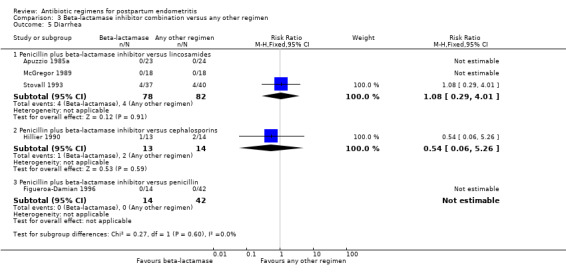

Secondary outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences for any other outcome (Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 3.6). CIs were wide for other outcomes due to the low number of participants with those outcomes.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, Outcome 4 Allergic reaction.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen, Outcome 6 Length of stay.

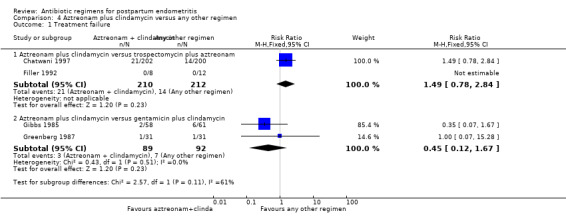

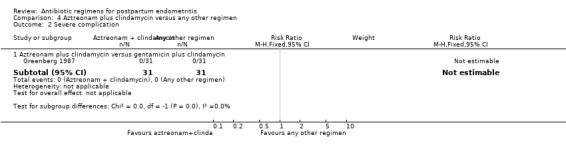

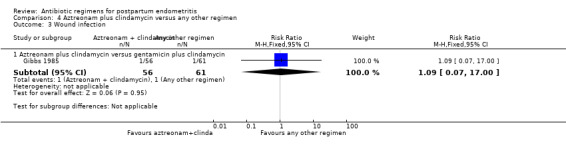

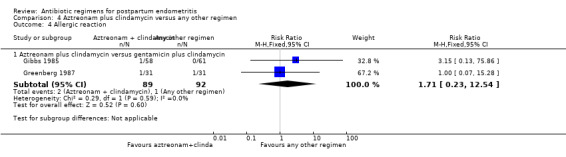

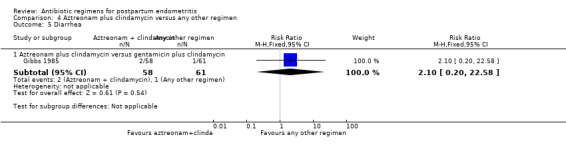

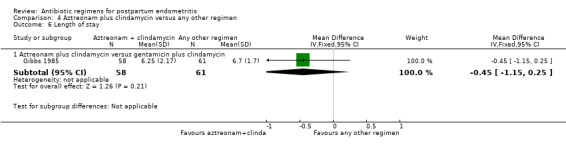

4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen ‐ four studies, 603 women

Four trials (603 participants) compared aztreonam plus clindamycin with other regimens. Two of these were comparisons with clindamycin plus aztreonam versus clindamycin plus gentamicin (Gibbs 1985; Greenberg 1987). The other two trials compared clindamycin and aztreonam with trospectomycin (Chatwani 1997; Filler 1992).

Primary outcomes

There was no difference between these regimens for any of the outcomes (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

Secondary outcomes

There was no difference between these regimens for any of the outcomes (Analysis 4.3; Analysis 4.4; Analysis 4.5; Analysis 4.6).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen, Outcome 4 Allergic reaction.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aztreonam plus clindamycin versus any other regimen, Outcome 6 Length of stay.

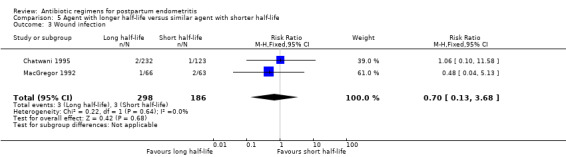

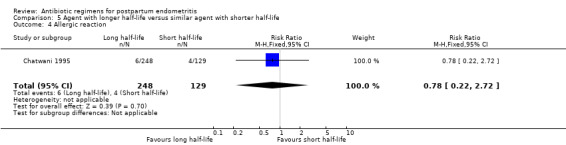

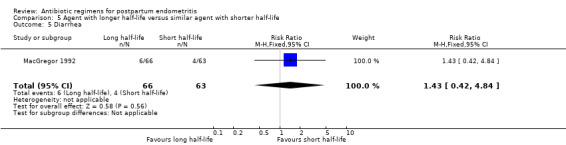

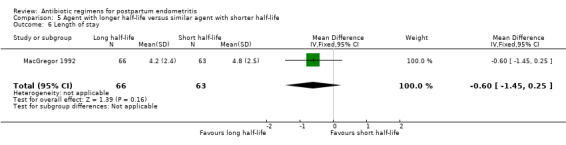

5. Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life ‐ two studies, 484 women

Two trials (484 participants) compared agents with a longer half‐life to a drug in the same class with a shorter half‐life. All regimens were cephalosporins: cefoxitin administered every six hours was compared with either cefmetazole administered every eight hours (Chatwani 1995) or cefotetan administered every 12 hours (MacGregor 1992).

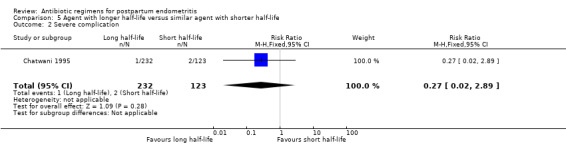

Primary outcomes

Treatment with an agent with a longer half life that is administered less frequently was associated with fewer treatment failures (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.92; 484 participants; 2 studies; I² 0%, Analysis 5.1) than cefoxitin. No significant differences were found for severe complications (Analysis 5.2)

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

Secondary outcomes

No significant differences were found for the other outcomes (Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4; Analysis 5.5; Analysis 5.6).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life, Outcome 4 Allergic reaction.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Agent with longer half‐life versus similar agent with shorter half‐life, Outcome 6 Length of stay.

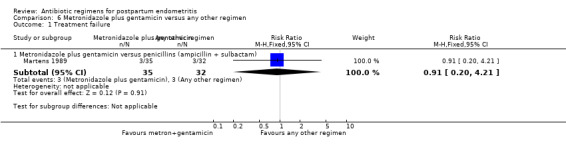

6. Metronidazole plus gentamicin versus any other regimen ‐ one study, 67 women

One small trial (Martens 1989, 67 participants) compared metronidazole and gentamicin with ampicillin/sulbactam.

Primary outcomes

There was no difference in treatment failures between the two regimens (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.20 to 4.21, Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Metronidazole plus gentamicin versus any other regimen, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

Secondary outcomes

There were no secondary outcomes reported for this analysis.

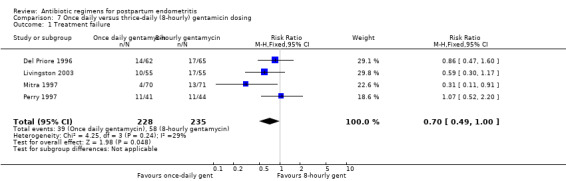

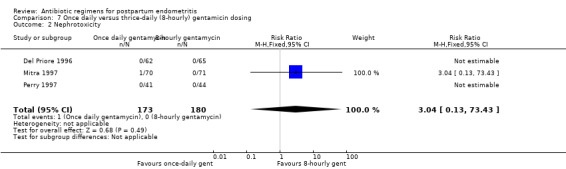

7. Once‐daily versus thrice‐daily gentamicin dosing ‐ four studies, 463 women

Four trials (463 participants) compared once‐daily versus thrice‐daily (i.e. eight‐hourly) administration of gentamicin (Del Priore 1996; Livingston 2003; Mitra 1997; Perry 1997).

Primary outcomes

There was a non‐significant trend toward fewer treatment failures with once‐daily dosing (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.00; 463 participants; 4 studies; I² 29%, Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Once daily versus thrice‐daily (8‐hourly) gentamicin dosing, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

Secondary outcomes

There was no difference in the incidence of nephrotoxicity between regimens (Analysis 7.2). Once‐daily dosing was associated with a shorter length of hospital stay (MD ‐0.73, 95% CI ‐1.27 to ‐0.20; 322 participants; 3 studies; I² 0%, Analysis 7.3).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Once daily versus thrice‐daily (8‐hourly) gentamicin dosing, Outcome 2 Nephrotoxicity.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Once daily versus thrice‐daily (8‐hourly) gentamicin dosing, Outcome 3 Length of stay.

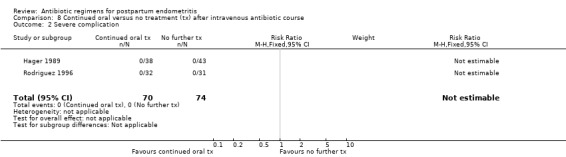

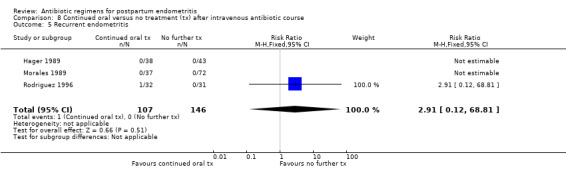

8. Continued oral versus no treatment after intravenous antibiotic course ‐ three studies, 253 women

Three trials (253 participants) compared continued oral antibiotic therapy with no treatment after intravenous therapy (Hager 1989; Morales 1989; Rodriguez 1996). The incidence of recurrent endometritis was exceptionally low in both groups (only one episode in 253 women).

Primary outcomes

No differences were found in treatment failure (Analysis 8.1). There were no severe complications in the studies (Analysis 8.2).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Continued oral versus no treatment (tx) after intravenous antibiotic course, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Continued oral versus no treatment (tx) after intravenous antibiotic course, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

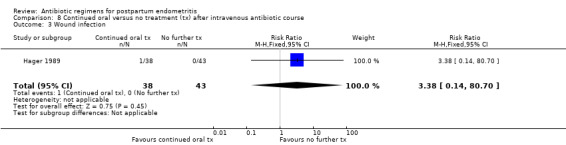

Secondary outcomes

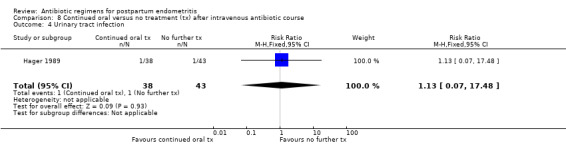

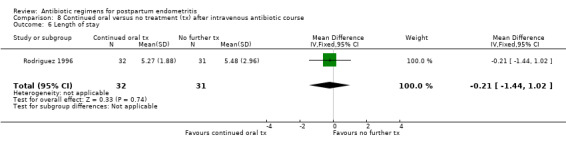

No differences were found in wound infection (Analysis 8.3), urinary tract infection (Analysis 8.4), recurrence of endometritis (Analysis 8.5), or length of stay (Analysis 8.6).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Continued oral versus no treatment (tx) after intravenous antibiotic course, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Continued oral versus no treatment (tx) after intravenous antibiotic course, Outcome 4 Urinary tract infection.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Continued oral versus no treatment (tx) after intravenous antibiotic course, Outcome 5 Recurrent endometritis.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Continued oral versus no treatment (tx) after intravenous antibiotic course, Outcome 6 Length of stay.

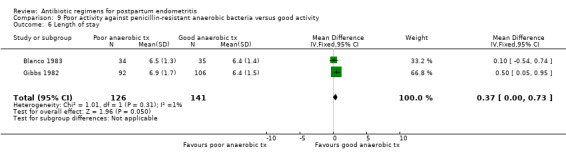

9. Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity ‐ seven studies, 774 women

Seven trials (774 participants) compared a regimen of antibiotics with poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria (e.g. the Bacteroides fragilis group) with a regimen with good activity.

Primary outcomes

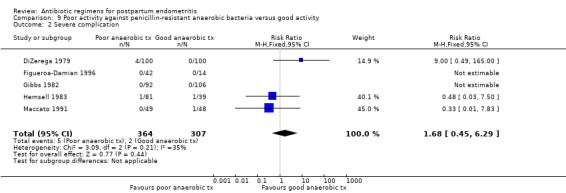

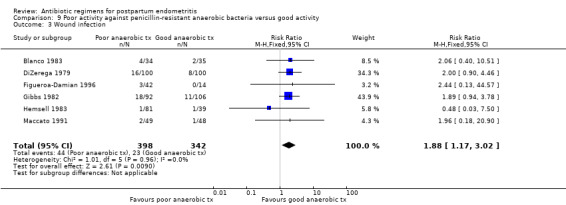

Antibiotics with poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobes were associated with higher failure rates of the regimen (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.72; 774 participants; 7 studies; I² 23%, Analysis 9.1). There were no significant differences in severe complications (Analysis 9.2).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity, Outcome 2 Severe complication.

Secondary outcomes

Antibiotics with poor activity against penicillin resistant anaerobes were associated with more wound infections (RR 1.88, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.02; 740 participants; 6 studies; I² 0%, Analysis 9.3).

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity, Outcome 3 Wound infection.

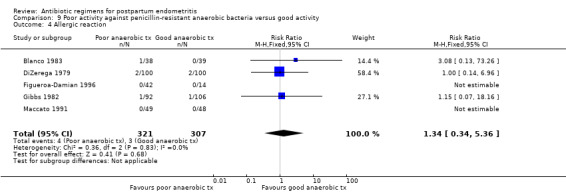

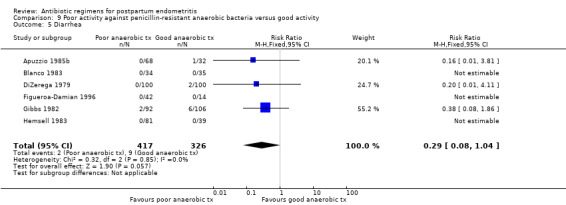

There were no significant differences between the groups for the other outcomes (Analysis 9.2; Analysis 9.4; Analysis 9.5; Analysis 9.6).

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity, Outcome 4 Allergic reaction.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity, Outcome 5 Diarrhea.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria versus good activity, Outcome 6 Length of stay.

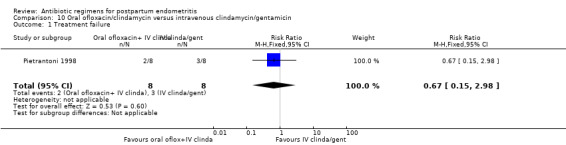

10. Oral ofloxacin/clindamycin versus intravenous clindamycin/gentamicin ‐ one study, 16 women

One small trial (16 participants) compared oral ofloxacin/intravenous clindamycin versus intravenous clindamycin/gentamicin.

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes showed no significant differences for treatment failures (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.98; I² 0%, Analysis 10.1).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral ofloxacin/clindamycin versus intravenous clindamycin/gentamicin, Outcome 1 Treatment failure.

Secondary outcomes

No secondary outcomes were reported.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The combination of clindamycin and an aminoglycoside was more effective than treatment with cephalosporins or penicillins as evidenced by fewer treatment failures. There were also fewer wound infections with clindamycin and an aminoglycoside as compared to cephalosporins. There were more treatment failures in women receiving gentamicin/penicillin compared with gentamicin/clindamycin. There is evidence that cefoxitin with a shorter half‐life is less effective than the cephamycins with a longer half‐life that are administered less frequently. Once‐daily dosing of gentamicin was associated with shorter hospital stays than thrice‐daily dosing. Regimens with poor activity against penicillin‐resistant anaerobic bacteria had higher failure rates and more wound infections than regimens with good activity against these organisms. For all the other outcomes, there were no differences between treatment regimens. However, for many of these comparisons the numbers studied were small and, although unlikely, significant differences may not have been detected.

If the improved response with clindamycin and gentamicin compared with any other regimen is expressed as the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB), 20 women (95% confidence interval (CI) 12 to 56) would need to be treated with clindamycin and gentamicin, rather than any other regimen, to prevent one additional treatment failure. What is missing from these studies, however, and what is needed to use the NNTB to help make treatment decisions, is a better assessment of side‐effects of the regimens and reporting of the cost of the different therapies. No study looked at the effect of treatment on the infant of a breastfeeding mother and any maternal renal toxicity was not described systematically. Very rarely were drug costs collected and overall no attempt was made to collect and compare all costs of treatment, including length of stay.

For the other regimens that were compared, where there were no differences in treatment failures, it is unfortunate that there were so few data on other outcomes. These factors might determine whether a regimen, albeit equally effective, had some other advantage. As a minimum, drug costs should have been reported consistently.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall the studies were at an unclear risk of bias. There were opportunities for systematic bias: allocation concealment was usually inadequately described and only rarely was there any attempt at 'blinding'. Often the study was sponsored by the manufacturer of a new drug and this drug was compared with the control regimen, typically clindamycin plus gentamicin. But despite all these potential biases, which would most likely work against the control arm, the combination of clindamycin and an aminoglycoside was more effective than other regimens with fewer treatment failures and wound infections. However, for many of these comparisons the numbers studied were small and, although unlikely, significant differences may not have been detected.

Although there may be differences in the expected response of women who developed endometritis after cesarean birth compared with those who developed infection after a vaginal birth, insufficient data were provided to allow us to perform a subgroup analysis. We could not perform subgroup analyses based on the presence of bacterial vaginosis or genital tract cultures positive for virulent organisms, as the data were not available. There were too few studies to detect whether there are differences in outcomes between regimens when prophylactic antibiotics have been given for cesarean births. Many of the studies performed extensive bacteriological work‐up on endometrial cultures, but this could not be approached systematically nor incorporated into this review.

Quality of the evidence

The overall risk of bias was unclear in the most of the studies. We assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE and judged the evidence for an aminoglycoside plus clindamycin with another regimen compared with cephalosporins or penicillins as low to very low quality for therapeutic failure, severe complications, wound infection and allergic reaction (Table 1). We downgraded scores as most studies had design limitations, few events, and wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. Though drop‐outs were reported with reasons explained, frequently, the number corresponding to each arm of a study was not given. For this reason we have provided analysis of available cases (rather than intention‐to‐treat). Many of the studies date back to the 1970s and 1980s. Since then there may have been changes in the causative organisms, as well as in the antimicrobial resistance profile.

Potential biases in the review process

We tried to minimize potential biases in the review process by having at least two review authors independently assess the eligibility for inclusion and exclusion, perform data abstraction and assess the risk of bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Very few studies have been conducted outside of the USA, with only four studies (from Central and South America) performed in the developing world. Since postpartum endometritis is an important cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in low‐income countries, the lack of studies conducted in such environments leaves a gap in our knowledge.

Barza 1996 performed a meta‐analysis of single versus multiple doses of aminoglycoside for the treatment of various infections, and the conclusions support a once‐daily regimen.

Any study of a new drug for the treatment of endometritis should, rather than have as its only objective the demonstration of equivalence between the regimens, be designed to incorporate other relevant outcomes in the analyses, and ideally should incorporate some form of cost‐benefit analysis. While concern about ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are identified as contraindications to the routine use of an aminoglycoside in community‐acquired intra‐abdominal infections (Solomkin 2003), healthy women with postpartum endometritis, whose treatment course is usually short, could be assumed to suffer from less toxicity from aminoglycosides compared with other women who are more likely to have significant co‐morbid illness. Although the studies included in this review did not collect information systematically on renal toxicity, there is no evidence that using an aminoglycoside in the clinical setting of postpartum endometritis should not be recommended because of toxicity. It is, however, important that any new regimen that is compared with clindamycin and an aminoglycoside should include ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity as outcomes.

There is evidence of increasing resistance in the Bacteroides fragilis group of organisms to clindamycin (Aldridge 2002). While there are no data to suggest that this is having an impact on treatment outcome in women with endometritis, whose infections are generally uncomplicated, there should be ongoing surveillance of the effect of changing antibiotic resistance patterns. Although overall a regimen with activity against the B fragilis group is better than one without, 80% of women treated with a regimen without that activity were cured, raising questions about the type of woman in which a broad spectrum regimen is necessary.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

It can be concluded from this review that the combination of clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside (such as gentamicin) is appropriate for the treatment of endometritis and that a regimen with activity against the Bacteroides fragilis group and other penicillin resistant anaerobic bacteria is better than one without. There is no good evidence that any one regimen is associated with fewer side‐effects. No specific recommendations can be made for the treatment of women who develop endometritis after receiving antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean birth as we were unable to specifically study that population in this review. Also, it should be noted that none of the trials' regimens included ampicillin plus clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside, so we cannot make a recommendation as to whether these three antibiotics are superior to clindamycin plus gentamicin alone.

Implications for research.

The majority of these studies took a traditional approach to the treatment of endometritis and compared new regimens to the standard of care in North America. Any further studies that compare clindamycin and an aminoglycoside with an alternative regimen, with efficacy as the primary outcome, should include regimens that are routinely used outside of North America and consider alternatives suitable for use in low‐income countries.

With the availability of new antibiotics with improved oral bioavailability, novel ways of managing endometritis should be explored and more creative study designs should evaluate early switching to the oral route. Although the new quinolones have a broader spectrum of activity than ciprofloxacin and excellent oral bioavailability, and are used widely to treat intra‐abdominal infections, it is generally recommended that they be avoided if a woman is breastfeeding, because their safety in breastfeeding has not been established. However, as more information on the safety of these agents in infants and children becomes available, their usefulness in treating women with endometritis should be studied. Any study of a new drug for the treatment of endometritis should, rather than have as its only objective the demonstration of equivalence between the regimens, be designed to incorporate other relevant outcomes in the analyses, and ideally should incorporate some form of cost‐benefit analysis.

Traditionally an empiric regimen active against the mixed aerobic and anaerobic organisms likely to be causing infection is selected, but with increasing concern about the appropriate utilization of antibiotics and developing antimicrobial resistance, this approach may no longer be appropriate. We should ask whether the use of endometrial cultures, collected under conditions where contamination is avoided, has a role for targeting antibiotic therapy more specifically to individual women. Studies may be designed that compare different strategies for selecting an antibiotic regimen.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 June 2015 | Amended | Corrected errors. Three trials (Gibbs 1983; Knodel 1988; Pastorek 1987) were inadvertently misclassified as quinolones. They belong with cephalosporins. Additionally, we removed two analyses (cephalosporins and cephamycins) as the initial analysis 1.1 included both of these medications and all applicable studies, so these analyses were redundant. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 November 2014 | New search has been performed | Search updated and two trials identified. Methods and risk of bias tables have been updated. A 'Summary of findings' table incorporated for this update |

| 30 November 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated. One trial included, one trial excluded. Two trials previously excluded are now included (Ledger 1974; Watts 1989) |

| 8 June 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Two reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Pietrantoni 1998a; Sweet 1988a). |

| 12 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 January 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated. One new study included (Roy 2003). The conclusions have not changed. |

| 31 January 2004 | New search has been performed | Two new studies have been included (Hemsell 1997; Livingston 2003) and one has been excluded (Pastorek 1987b). |

| 30 October 2001 | New search has been performed | Eight additional studies were evaluated for inclusion in the review. Six were added to the review and two were excluded. The conclusions drawn from the meta‐analysis were not changed. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Fiona M Smaill who developed the original review (French 2004).

Erika Ota's work was financially supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research (RHR), World Health Organization. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication.

We would like to thank Becky Davie and Sally Reynolds, student medical statisticians, who helped with the risk of bias assessments of some included studies.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus any other regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Lincosamides versus cephalosporins | 8 | 872 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.49, 0.99] |

| 1.2 Lincosamides versus monobactams | 2 | 181 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.25 [0.60, 8.43] |

| 1.3 Lincosamides versus penicillins | 7 | 689 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.46, 0.90] |

| 1.4 Lincosamides versus quinolone | 3 | 176 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.38, 1.37] |

| 2 Severe complication | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Lincosamides versus cephalosporins | 4 | 476 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.40 [0.30, 19.19] |

| 2.2 Lincosamides versus monobactams | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.3 Lincosamides versus penicillins | 5 | 422 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.09, 1.18] |

| 2.4 Lincosamides versus quinolone | 2 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.89 [0.31, 27.20] |

| 3 Wound infection | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Lincosamides versus cephalosporins | 4 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.30, 0.93] |

| 3.2 Lincosamides versus monobactams | 1 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.06, 14.85] |

| 3.3 Lincosamides versus penicillins | 3 | 339 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.21, 1.00] |

| 3.4 Lincosamides versus quinolone | 1 | 97 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.05, 5.45] |

| 4 Allergic reaction | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Lincosamides versus cephalosporins | 6 | 680 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.44, 4.21] |

| 4.2 Lincosamides versus monobactams | 2 | 181 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.08, 4.31] |

| 4.3 Lincosamides versus penicillins | 2 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.14, 6.96] |

| 4.4 Lincosamides versus quinolone | 2 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.06, 13.90] |

| 5 Diarrhea | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Lincosamides versus cephalosporins | 7 | 758 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.09 [0.77, 5.63] |

| 5.2 Lincosamides versus monobactams | 1 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.04, 5.10] |

| 5.3 Lincosamides versus penicillins | 4 | 375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.55, 3.72] |

| 5.4 Lincosamides versus quinolone | 1 | 63 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.06, 13.90] |

| 6 Length of stay | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Lincosamides versus cephalosporins | 4 | 494 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.26 [‐0.56, 0.04] |

| 6.2 Lincosamides versus monobactams | 1 | 119 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [‐0.25, 1.15] |

| 7 Treatment failure despite administration of prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Lincosamides versus penicillins | 2 | 229 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.63, 1.98] |

Comparison 2. Aminoglycoside plus penicillin or ampicillin versus any other regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin versus gentamycin/clindamycin | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.57 [1.48, 4.46] |

| 1.2 Aminoglycoside plus ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.15, 2.03] |

| 2 Severe complication | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin versus gentamycin/clindamycin | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 2.04] |

| 2.2 Amnioglycoside plus ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Wound infection | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin versus gentamycin/clindamycin | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.22, 1.12] |

| 3.2 Aminoglycoside plus ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.44 [0.13, 44.57] |

| 4 Allergic reaction | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin versus gentamicin/clindamycin | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.14, 6.96] |

| 4.2 Aminoglycoside plus ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Diarrhea | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Aminoglycoside plus penicillin versus gentamicin/clindamycin | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.24, 102.85] |

| 5.2 Aminoglycoside plus ampicillin versus piperacillin/tazobactam | 1 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 3. Beta‐lactamase inhibitor combination versus any other regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Penicillin plus beta‐lactamase inhibitor versus lincosamides | 6 | 495 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.70, 1.64] |