Abstract

Background

Various endosymbiotic bacteria, including Wolbachia of the Alphaproteobacteria, infect a wide range of insects and are capable of inducing reproductive abnormalities to their hosts such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), parthenogenesis, feminization and male-killing. These extended phenotypes can be potentially exploited in enhancing environmentally friendly methods, such as the sterile insect technique (SIT), for controlling natural populations of agricultural pests. The goal of the present study is to investigate the presence of Wolbachia, Spiroplasma,Arsenophonus and Cardinium among Bactrocera,Dacus and Zeugodacus flies of Southeast Asian populations, and to genotype any detected Wolbachia strains.

Results

A specific 16S rRNA PCR assay was used to investigate the presence of reproductive parasites in natural populations of nine different tephritid species originating from three Asian countries, Bangladesh, China and India. Wolbachia infections were identified in Bactrocera dorsalis, B. correcta, B. scutellaris andB. zonata, with 12.2–42.9% occurrence, Entomoplasmatales in B. dorsalis, B. correcta, B. scutellaris, B. zonata,Zeugodacus cucurbitae and Z. tau (0.8–14.3%) and Cardinium in B. dorsalis andZ. tau (0.9–5.8%), while none of the species tested, harbored infections with Arsenophonus. Infected populations showed a medium (between 10 and 90%) or low (< 10%) prevalence, ranging from 3 to 80% for Wolbachia, 2 to 33% for Entomoplasmatales and 5 to 45% for Cardinium. Wolbachia and Entomoplasmatales infections were found both in tropical and subtropical populations, the former mostly in India and the latter in various regions of India and Bangladesh. Cardinium infections were identified in both countries but only in subtropical populations. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the presence ofWolbachia with some strains belonging either to supergroup B or supergroup A. Sequence analysis revealed deletions of variable length and nucleotide variation in three Wolbachia genes. Spiroplasma strains were characterized as citri–chrysopicola–mirum and ixodetis strains while the remaining Entomoplasmatales to the Mycoides–Entomoplasmataceae clade.Cardinium strains were characterized as group A, similar to strains infecting Encarsia pergandiella.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that in the Southeast natural populations examined, supergroup A Wolbachia strain infections were the most common, followed by Entomoplasmatales and Cardinium. In terms of diversity, most strains of each bacterial genus detected clustered in a common group. Interestingly, the deletions detected in three Wolbachia genes were either new or similar to those of previously identified pseudogenes that were integrated in the host genome indicating putative horizontal gene transfer events in B. dorsalis, B. correcta and B. zonata.

Keywords: 16S rRNA, Multi locus sequence typing, Wolbachia, Arsenophonus, Cardinium, Spiroplasma, Horizontal gene transfer, Bactrocera, Zeugodacus

Background

In recent years, many maternally inherited endosymbiotic bacteria, capable of manipulating the reproductive functions of their hosts, have been identified in a wide range of arthropod species [1]. Among them, the most thoroughly studied are those that belong to the genus Wolbachia, a highly diverse group of intracellular endosymbionts belonging to the Alphaproteobacteria [2–4]. Wolbachia infections are widespread in insect species with estimates suggesting an incidence rate ranging from 20 to 66% [5–10]. Wolbachia infections vary significantly between species and also between different geographical populations of a species, exhibiting either high (> 90%) or low prevalence (< 10%) [5, 11, 12]. Overall, the diverse interactions of Wolbachia with their hosts cover a broad spectrum of biological, ecological and evolutionary processes [13–17]. One of the most interesting aspects of Wolbachia interactions is the induction of a range of reproductive abnormalities to their hosts, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), parthenogenesis, male-killing and feminization of genetic males so they develop as females [3, 14, 18–20]. For instance, in woodlice, genetic males develop as females when Wolbachia disrupts a gland that produces a hormone required for male development [21]. In this way, the bacteria change the birth ratio in favor of females, ensuring their steady proliferation within host populations, since they are vertically transmitted by infected females [2, 3, 17, 20, 22].

Apart from Wolbachia, additional reproductive symbionts from distantly related bacterial genera have been recently brought to light, such as Arsenophonus, Cardinium and Spiroplasma. Strains belonging to the genus Cardinium, a member of the phylum Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides (CFB), exhibit the same broad range of reproductive alterations with Wolbachia [23–29], with the exception of male-killing which has not been identified yet [1, 17, 28]. On the other hand, members of Arsenophonus, of the Gammaproteobacteria, and Spiroplasma, wall-less bacteria belonging to the class Mollicutes, are known to induce male-killing phenotypes [1, 17, 30–32]. The incidence rate of all three genera in insects was shown to vary between 4 and 14%, fairly lower than that of Wolbachia [1, 33–39], although higher occurrence was observed for Arsenophonus in aphids and ants, reaching up to 30 and 37.5% of species respectively [40, 41] as well as for Cardinium in planthoppers (47.4% of species) [36]. In Cardinium and Spiroplasma-infected species a wide range of prevalence (15–85%) was observed while in the case of Arsenophonus, prevalence reached values above 75% with relatively few exceptions, such as the wasp Nasonia vitripennis with a 4% infection rate or various ant species that showed a broader range (14–66%) [1, 38, 40, 42].

Insect species belonging to the genus Bactrocera and the closely related species Dacus longicornis (Wiedemann), Z.cucurbitae (Coquillett) and Z. tau (Walker) are members of the Tephritidae, a family of fruit flies with worldwide distribution that contains important agricultural pests, capable of affecting a variety of fruit and horticultural hosts [43–46]. The direct damage to hosts caused by female oviposition and the development of the larvae, results in severe losses in fruit and vegetable production. Their economic impact also expands to trade, with strict quarantine measures imposed on shipments originating from infested countries [47–50]. The reproductive alterations induced by the bacterial symbionts, as well as their role in insect host biology and ecology, could be used in environment-friendly approaches, such as the sterile insect technique (SIT) and other related techniques, for the area-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM) of insect pest populations [13, 51–65].

The current classification of Wolbachia strains based on molecular markers includes 16 supergroups, from A to Q, with the exception of G which has been merged with A and B [66–71]. Classification is primarily based on the 16S rRNA gene but other commonly used genetic markers include the gltA (citrate synthase), groEL (heat-shock protein 60), coxA (cytochrome c oxidase), fbpA (fructose-bisphosphatealdolase),ftsZ (cell division protein), gatB (glutamyl-tRNA(Gln) amidotransferase, subunit B),hcpA (hypothetical conserved protein) andwsp genes (Wolbachia surface protein) [7, 72, 73]. Strain genotyping is performed by multi locus sequence typing (MLST) using five conserved genes (coxA, fbpA, ftsZ, gatB andhcpA), the wsp gene and four hypervariable regions (HVRs) of the WSP protein [74]. Similarly, Spiroplasma strains are divided into three groups, the apis clade, the citri–chrysopicola–mirum clade and the ixodetis clade [75, 76]. Phylogenetic analyses are primarily based on the 16SrRNA gene, while more detailed MLST approaches include partial sequencing of the 23S rRNA, 5S rRNA, gyrB, rpoB,pgk (phosphoglycerate kinase) parE, ftsZ, fruR genes, as well as the complete 16S–23S internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) [75, 77]. The remaining closely related Entomoplasmatales genera,Mycoplasma, Entomoplasma and Mesoplasma, form the separate Mycoides–Entomoplasmataceae clade [76]. Phylogenetic analyses for Cardinium are performed with the use of the 16S rRNA and gyrB genes but also with the amino acid sequence of Gyrase B (gyrB gene) [35, 36, 78–80]. Cardinium strains can be separated into group A, which infect wasps, planthoppers, mites and other arthropods, group B, found in parasitic nematodes and group C in biting midges [36].

Several studies reported that genes, chromosomal segments of various sizes or even the entire Wolbachia genome have been horizontally transferred to host chromosomes [81, 82]. The first incidence of a horizontal gene transfer (HGT) event was described in the adzuki bean beetle Callosobruchus chinensis (L.), where ~ 30% of the Wolbachia genome was found to be integrated in the X chromosome [83, 84]. Such events have also been described in a variety of insect and nematode hosts, including the fruit flyDrosophila ananassae and the tsetse flyGlossina morsitans morsitans [81, 85–89]. In G. m. morsitans two large Wolbachia genome segments of 527 and 484 Kbp have been integrated into the Gmm chromosomes, corresponding to 51.7% and 47.5.% of the draft Wolbachia genome [90]. In the case of Drosophila ananassae, nearly the entire ~ 1.4 MbpWolbachia genome has been integrated in a host chromosome [81] while in Armadillidium vulgare the ~ 1.5 Mbp Wolbachia genome was not only integrated but also duplicated, resulting in the formation of a new female sex chromosome [91]. In the case of the mosquito Aedes aegypti, the direction of the HGT is not clear and could have happened either from the insect or from Wolbachia [92, 93]. Usually, the incorporated fragments lose their functionality and become pseudogenes with low levels of transcription [88]. However, some of these genes are highly expressed and can either provide a new function to the host, or replace a lost one [89, 92, 93]. These new functions may provide hosts with nutritional benefits, enable them to parasitize other eukaryotes, survive in unfavorable environments or protect themselves from other organisms [88].

In the present study, we investigate the presence of Wolbachia, Cardinium and Entomoplasmatales (the genera Spiroplasma,Entomoplasma and Mesoplasma) infections in natural populations of Bactrocera, Dacus and Zeugodacus fruit fly species. The detection and the phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial genera were based primarily on the use of the 16S rRNA gene. Additionally, the molecular characterization of the Wolbachia strains was performed with the use of the wsp and MLST gene markers. Finally, we report on the presence of Wolbachia pseudogenes suggesting putative horizontal transfer events to the genome of various Bactrocera species andZ. cucurbitae.

Results

Infection prevalence of reproductive symbiotic bacteria

Wolbachia, Entomoplasmatales andCardinium infections were detected in 15 populations, divided into six species of Bactrocera and Zeugodacus (Tables 1, 2). Wolbachia was the most prevalent with 64 out of 801 (8%) infected individuals, followed by 40 (5%) Entomoplasmatales and 12 (1.5%) Cardinium (Tables 1 and 2). On the contrary, no Arsenophonus infections were found in any of the populations tested. Bactrocera minax (Enderlein),B. nigrofemoralis (White & Tsuruta) and D. longicornis were the only species that did not harbor any infections of the bacterial symbionts tested in this study (Table 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of reproductive bacteria in tephritid fruit fly populations from Bangladesh, China and India using a 16S rRNA gene-based PCR screening approach. For each genus the absolute number and the percentage (in parentheses) of infected individuals are given. The last column on the right (“Total*”) indicates the total occurrence of all three Entomoplasmatales genera

| Entomoplasmatales | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Country | State | Area | Samples | Wolbachia | Cardinium | Spiroplasma | Entomoplasma | Mesoplasma | Total* | |

| 1 | B. correcta | India | Maharashtra | Trombay | 25 | 10 (40) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| 2 | B. correcta | India | Karnataka | Raichur | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | B. dorsalis | Bangladesh | – | Rajshahi | 36 | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 6 (16.7) | 0 | 6 (16.7) |

| 4 | B. dorsalis | Bangladesh | – | – | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | B. dorsalis | Bangladesh | – | Dinajpur | 22 | 0 | 10 (45.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | B. dorsalis | Bangladesh | – | Dhaka | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | B. dorsalis | Bangladesh | – | Jessore | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | B. dorsalis | India | Maharashtra | Trombay | 30 | 14 (46.7) | 0 | 2 (6.7) | 5 (16.7) | 0 | 7 (23.3) |

| 9 | B. dorsalis | India | Himachal Pradesh | Palampur | 15 | 10 (66.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 5 (33.3) | 0 | 5 (33.3) |

| 10 | B. minax | China | – | – | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | B. nigrofemoralis | India | Himachal Pradesh | Palampur | 5 | 2a (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | B. scutellaris | India | Himachal Pradesh | Palampur | 35 | 15 (42.9) | 0 | 0 | 5 (14.3) | 0 | 5 (14.3) |

| 13 | B. zonata | Bangladesh | – | Rajshahi | 21 | 2a (0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (19) |

| 14 | B. zonata | Bangladesh | – | Jessore | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | B. zonata | Bangladesh | – | Dinajpur | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | B. zonata | India | Maharashtra | Trombay | 25 | 10 (40) | 0 | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 3 (12) |

| 17 | B. zonata | India | Karnataka | Raichur | 5 | 4 (80) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| 18 | B. zonata | India | Himachal Pradesh | Palampur | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (20) |

| 19 | D. longicornis | Bangladesh | – | Dhaka | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | Z. cucurbitae | Bangladesh | – | Rajshahi | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | Z. cucurbitae | Bangladesh | – | Jessore | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| 22 | Z. cucurbitae | Bangladesh | – | – | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | Z. cucurbitae | Bangladesh | – | Dinajpur | 96 | 2a (0) | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 3 (3.1) |

| 24 | Z. cucurbitae | Bangladesh | – | Dhaka | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 2 (6.9) |

| 25 | Z. tau | Bangladesh | – | Jessore | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | Z. tau | Bangladesh | – | Dhaka | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 | Z. tau | Bangladesh | – | Rajshahi | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | Z. tau | Bangladesh | – | Dinajpur | 20 | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | Z. tau | India | Maharashtra | Trombay | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| 30 | Z. tau | India | Himachal Pradesh | Palampur | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 9 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 801 | ||||||

a. Only pseudogenised sequences

Table 2.

Prevalence of reproductive symbionts in different tephritid fruit fly species

| Entomoplasmatales | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Country | Areas with infected populations | Samples | Wolbachia | Cardinium | Spiroplasma | Entomoplasma | Mesoplasma |

| B. correcta | India | Trombay | 30 |

10b (30%) |

– | – |

1 (3.3%) |

– |

| B. dorsalis | India | Trombay, Palampur | 189 |

25b (13.2%) |

11 (5.8%) |

2 (1.1%) |

16 (8.5%) |

– |

| Bangladesh | Rajshahi, Dinajpur | |||||||

| B. minax | China | – | 40 | – | – | – | – | – |

| B. nigrofemoralis | India | Palampur | 5 |

2a (0%) |

– | – | – | – |

| B. scutellaris | India | Palampur | 35 |

15 (42.9%) |

– | – |

5 (14.3%) |

– |

| B. zonata | India |

Trombay, Raichur, Palampur |

115 |

14b (12.2%) |

– | – |

6 (5.2%) |

3 (2.6%) |

| Bangladesh | Rajshahi |

2a (0%) |

||||||

| D. longicornis | Bangladesh | Dhaka | 21 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Z. cucurbitae | Bangladesh |

Dinajpur, Jessore, Dhaka |

257 |

2a (0%) |

– |

1 (0.4%) |

4 (1.6%) |

1 (0.4%) |

| Z. tau | India | Trombay | 109 | – |

1 (0.9%) |

– | – |

1 (0.9%) |

| Bangladesh | Dinajpur | |||||||

a. Only pseudogenized sequences

b. Both integral (genuine or full) and pseudogenized Wolbachia genes

The presence of Wolbachia, at variable infection rates, was identified in seven populations from four different species of tephritid fruit flies (Table 2). The most prevalent infections were observed in B. scutellaris (Bezzi) (42.9%) and B. correcta (Bezzi) (30%) compared to B. dorsalis (Hendel) (13.2%) and B. zonata (Saunders) (12.2%) (chi-squared test:p-values< 0.01). On the other hand, noWolbachia infections were identified in the remaining species tested, namely, D. longicornis, B. minax,B. nigrofemoralis, Z. cucurbitae and Z. tau. Variation in prevalence was observed between field populations of the same species from different geographic regions. For example,Wolbachia infections in B. zonata were characterized by 80% prevalence in a population from Raichur, India, by 40% in Trombay, India and were absent from the remaining four areas tested (Table 1, Additional file 1). Heterogeneity in infection rates was also observed in B. dorsalis, which showed medium prevalence (46.7 and 66.7%), except for a population from Rajshahi – the only infected population from Bangladesh – which showed a considerably lower infection rate (2.8%) (chi-squared test:p-values< 0.01). The remaining fourB. dorsalis populations appeared to be free of Wolbachia infections. Only one of twoB. correcta populations studied was infected with Wolbachia, the population originating from the area of Trombay, India with 40% prevalence. Finally, in the case of B. scutellaris, the only population tested was found to be infected at 42.9% rate. Wolbachia prevalence also ranged significantly between populations of the same species that originated from different countries, with fruit flies from India exhibiting higher infection rate than those from Bangladesh. More specifically, Indian populations of B. dorsalis and B. zonata exhibited 53.3 and 40% prevalence respectively, significantly higher than populations from Bangladesh that were found to contain only 0.7% and pseudogenized Wolbachia sequences respectively (chi-squared test: p-values< 0.01) (Table 1).

The occurrence of Spiroplasma and its relative genera, Entomoplasma andMesoplasma, displayed variation between different species, populations and countries (Tables 1, 2). Again, the most prevalent infections per species were observed in B. scutellaris (14.3%) followed by B. dorsalis (9.6%) and B. zonata (7.8%). Three more species were infected with members of the Entomoplasmatales, including B. correcta (3.3%), and at much lower rate compared to the three species with prevalent infections, Z. cucurbitae (2.4%) and Z. tau (0.9%) (chi-squared test: p-values< 0.01). The remaining species that were tested, including B. minax, B. nigrofemoralis and D. longicornis, appeared to be free of Entomoplasmatales infections (Table 2). In some cases, the infection rate varied between different populations. For example, in B. dorsalis, prevalence ranged from 33.3% in Palampur, to 23.4% in the Trombay area, in India and 16.7% in the Rajshahi District, in north-western Bangladesh. There were also four populations from Bangladesh that did not contain any infections (Table 1). At the same time, B. zonata infection rates were almost uniform in three populations (19–20%) and relatively lower in Trombay, India (12%), while two populations were uninfected. The only population of B. scutellaris that was studied, carried Entomoplasmatales infections at medium rate (14.3%) and populations of B. correcta, Z. cucurbitae, andZ. tau at even lower (1.8–10%; Table 1). Spiroplasma infections were observed in only three individuals, two of them originating from a population of B. dorsalis from Trombay, in India and the third one from a population of Z. cucurbitae from Dinajpur, in northern Bangladesh (6.7 and 1% respectively). The total prevalence in each species was 1.1 and 0.4% (Table 2). Differences in infection rates were also observed between different countries. In B. zonata for instance, 14.3% of samples from India were infected with Entomoplasmatales while in Bangladesh the infection rate was calculated at 5% (Table 1).

Two populations of B. dorsalis and one of Z. tau were found to harborCardinium infections with much different prevalence. The most prevalent infection was identified in a population ofB. dorsalis from Dinajpur, Bangladesh with 45.5% (Table 1) (chi-squared test:p-values< 0.01). A population ofZ. tau, also from Dinajpur, carried a 5% infection, while the other infected B. dorsalis population originating from Palampur, India displayed a 6.7% infection rate. The prevalence of Cardinium infections was 5.8% in B. dorsalis and 0.9% in Z. tau (Table 2) (chi-squared test: p-values< 0.04). Finally, in the case ofB. dorsalis, populations from Bangladesh showed higher prevalence, but without statistical significance, than those from India (6.9% compared to 2.2%).

MLST genotyping for Wolbachia strains

Sequence analysis revealed the presence of several alleles for all MLST, wsp and 16S rRNA loci: three for gatB, two for coxA, two for hcpA, two for ftsZ, two forfbpA, two for wsp and nine for the 16S rRNA. Interestingly, more than half of the MLST and wsp alleles were new in the Wolbachia MLST database: two for gatB, one for coxA, one forhcpA, two for ftsZ, one for fbpA and one for wsp, respectively (Table 3). Cloning and sequencing of the MLST, wsp and 16S rRNA gene amplicons clearly indicated the presence of multiple strains within individuals of three populations (Table 3). In more detail, multiple bacterial strains with two potential Sequence Types (STs, combination of alleles) were detected in the infected B. zonata sample (2.2) from Trombay. The second infected B. zonata sample (8.2) contained four possible ST combinations. In addition to these multiple infections, we found double 16S rRNA alleles in four Indian samples, in B. correcta (1.4 and 01.5H) from Trombay, in B. scutellaris (02.5E) from Palampur and in B. zonata (01.4E) from Raichur.

Table 3.

Wolbachia MLST,wsp, 16S rRNA allele profiles and pseudogenes for infected Bactrocera and Z. cucurbitae populations

| Wolbachia MLST | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample code | species | Country, Area | ST | gatB | coxA | hcpA | ftsZ | fbpA | wsp |

16S rRNA |

| 03.7D | B. dorsalis |

Bangladesh, Rajshahi |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL4 + PW |

| 03.3B | B. zonata |

Bangladesh, Rajshahi |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | PW |

| BC.18 | Z. cucurbitae |

Bangladesh, Dinajpur |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | PW |

| BC.27 | ||||||||||

| 1.4 | B. correcta |

India, Maharashtra, Trombay |

wBco | 8 | New1 | 103 | New1 | 160 | 335 |

AL2 + AL9 + PW |

| 01.5H | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL5 + AL7 | ||

| DD2.2 | B. dorsalis |

India, Maharashtra, Trombay |

wBdo | New2 | New1 | New1 | New2 | New1 | New1 | AL1 |

| 01.10B | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL2 | ||

| 01.11A | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL2 | ||

| 02.11D | B. dorsalis |

India, Himachal Pradesh, Palampur |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL3 + PW |

| 02.10G | B. nigrofemoralis |

India, Himachal Pradesh, Palampur |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | PW |

| 02.5E | B. scutellaris |

India, Himachal Pradesh, Palampur |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL2 + AL8 |

| 01.4E | B. zonata |

India, Karnataka, Raichur |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | AL2 + AL8 |

| 2.2 | B. zonata |

India, Maharashtra, Trombay |

Multi wBzo-1 wBzo-2 |

8 + New1 | 84 | 103 | New1 + PW | 160 | 335 + PW | AL6 + PW |

| 8.2 |

Multi wBzo-1 wBzo-2 wBzo-3 wBzo-4 |

8 + New1 | 84 + New1 | 103 | New1 + PW | 160 | 335 | AL3 + PW | ||

PW: pseudogenized (with deletions) Wolbachia genes

New: new alleles based on MLST data

Multi: multiple potential combinations/ST of alleles

Phylogenetic analysis

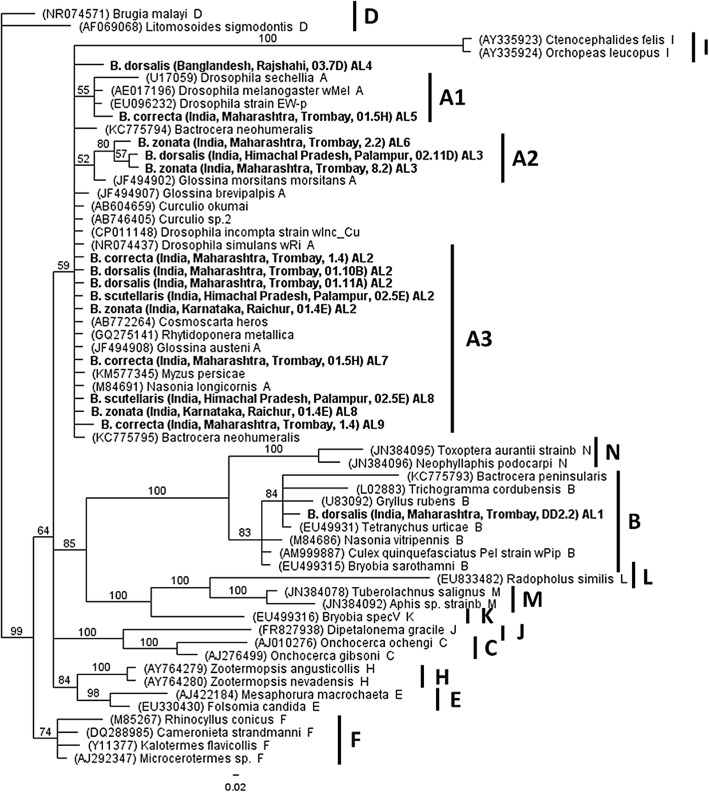

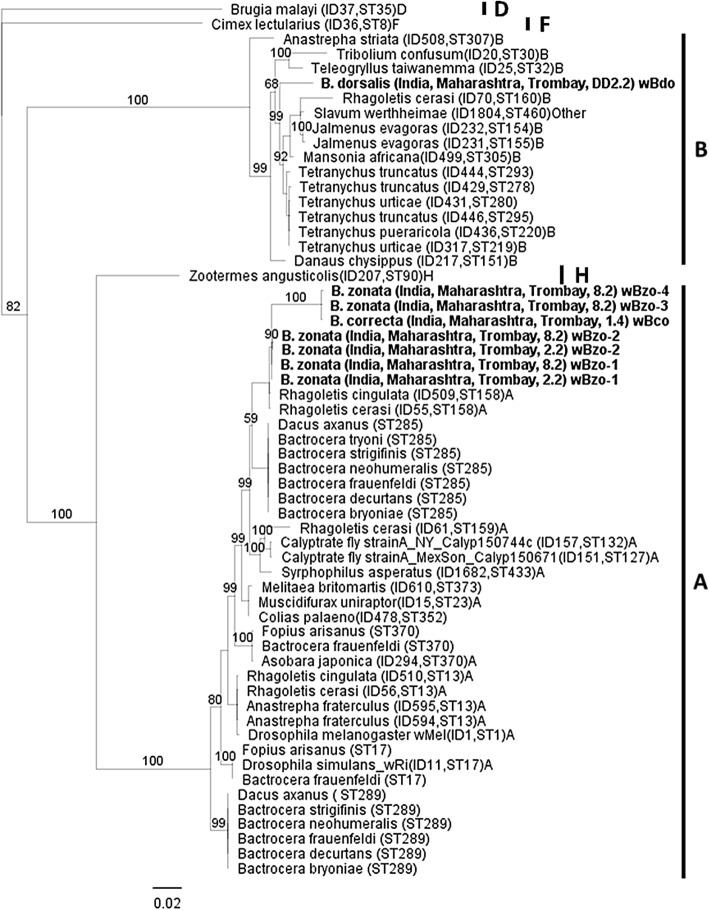

The Wolbachia phylogenetic analysis was carried out on seven Wolbachia-infected natural populations and was based on the datasets of all MLST (gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ and fbpA) and 16S rRNA loci. Phylogenetic analysis, based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences, revealed that the clear majority of the Wolbachia strains infecting Bactrocera species belonged to supergroup A, except for the strain found in B. dorsalis sample DD2.2 from Trombay that fell into supergroup B (Fig. 1). In more detail, based on the 16S rRNA loci, Wolbachia strains infecting Bactrocera species classified into three clusters in supergroup A and one cluster in supergroup B (Fig. 1). The first cluster (A1) includes a Wolbachia strain infecting a B. correcta sample (01.5H) from Trombay which groups with the strain present in Drosophila melanogaster. The second cluster (A2) is comprised of strains present in samples from India, such as B. dorsalis from Palampur and B. zonata from Trombay which are similar to Wolbachia from Glossina morsitans morsitans. The third cluster (A3) is the largest and contains strains present in samples of B. correcta (Trombay), B. dorsalis (Trombay), B. scutellaris (Palampur) and B. zonata (Raichur) from India as well as in samples of B. dorsalis from Bangladesh (Rajshahi), that are closely related to Wolbachia strains found in Drosophila simulans and Glossina austeni. Finally, the Wolbachia strain infecting sample DD2.2 of B. dorsalis from Trombay, which fell in supergroup B, clusters with the strain from Tetranychus urticae. The same results were also acquired with the phylogenetic analysis based on the concatenated sequences of the MLST genes (Fig. 2). More specifically: (a) the Wolbachia strainswBzo-3, wBzo-4 (multiple infections in sample 8.2 of B. zonata from Trombay) and wBco (infecting B. correcta from Trombay) were classified into a distinct cluster of supergroup A, while theWolbachia strains wBzo-1 and wBzo-2 infecting both B. zonata samples from Trombay (2.2 and 8.2) were assigned into another cluster of supergroup A, (b) the strainwBdo infecting B. dorsalis from Trombay was assigned to supergroup B. The most closely related Wolbachia strains towBzo-1 and wBzo-2 have been detected in Rhagoletis cingulata (ST 158) and Rhagoletis cerasi (ST 158) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Bayesian inference phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence (438 bp). The 15Wolbachia strains present in Bactrocera and indicated in bold letters (including 9 Alleles: AL1 to AL9) along with the other strains represent supergroups A, B, C, D, E, F, H, I, J, K, L, M and N. Strains are characterized by the names of their host species and their GenBank accession number. Wolbachia supergroups are shown to the right of the host species names. Bayesian posterior probabilities based on 1000 replicates are given (only values > 50% are indicated; Brugia malayi used as outgroup)

Fig. 2.

Bayesian inference phylogeny based on the concatenated MLST data (2079 bp). The eight Wolbachia strains present in Bactrocera are indicated in bold letters, while all the other strains represent supergroups A, B, D, F and H. Strains are characterized by the names of their host species and ST number from the MLST database. Wolbachia supergroups are shown to the right of the host species names. Bayesian posterior probabilities based on 1000 replicates are given (only values > 50% are indicated; Brugia malayi used as outgroup)

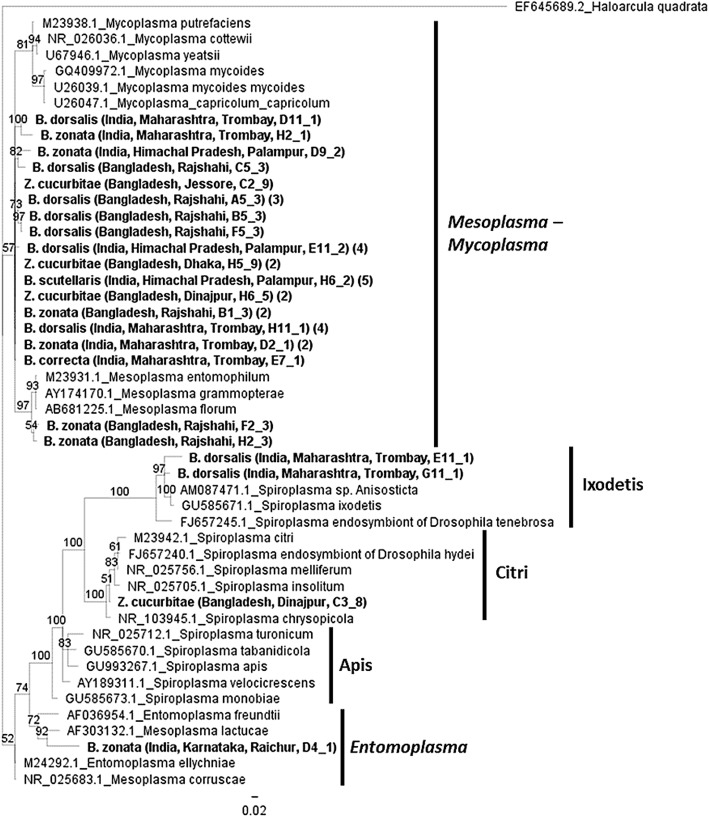

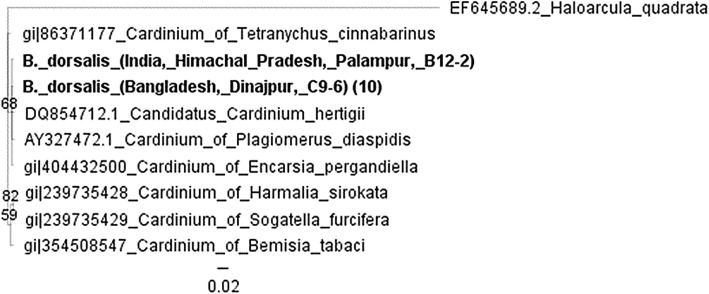

Phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene revealed that the majority of the Entomoplasmatales infecting Bactrocera and Zeugodacus species clustered with Mesoplasma corruscae and Entomoplasma ellychniae (Fig. 3). These 32 sequences were found in populations of B. correcta, B. dorsalis, B. scutellaris andB. zonata from various regions of India and in populations of B. dorsalis, B. zonata and Z. cucurbitae from Bangladesh. Two sequences from B. zonata samples (Rajshahi) grouped with the closely related Mesoplasma entomophilum cluster. One sequence from B. zonata (Raichur) clustered with Mesoplasma lactucae, in the closely related Entomoplasma group. A strain found in Z. cucurbitae from Bangladesh (Dinajpur) was clustered with the Spiroplasma citri-chrysopicola-mirum group and two strains found in a population of B. dorsalis from the area of Trombay in India, fell into the Spiroplasma ixodetis group. Finally, the phylogenetic analysis of Cardinium 16S rRNA sequences that were identified in two populations ofB. dorsalis (Dinajpur and Palampur) were grouped with Cardinium species infectingEncarsia pergandiella and Plagiomerus diaspidis that compose group A ofCardinium strains (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Bayesian inference phylogeny based on the Entomoplasmatales 16S rRNA gene sequence (301 bp). The strains present in Bactrocera and Z. cucurbitae are indicated in bold letters. Most samples represent the Entomoplasma and Mesoplasma-Mycoplasma groups while three sequences represent the Ixodetis and Citri groups of Spiroplasma. The Ixodetis, Citri and Apis clades are shown to the right of the Spiroplasma species names. Bayesian posterior probabilities based on 1000 replicates are given (only values > 50% are indicated; Haloarcula quadrata used as outgroup). For each strain, their GenBank accession number is also given on the left. Two sequences were removed due to short length (one fromB. dorsalis and one fromZ. tau). Parentheses on the right of the name indicate number of sequences from that population

Fig. 4.

Bayesian inference phylogeny based on the Cardinium 16S rRNA gene sequence (354 bp). The strains present in Bactrocera are indicated in bold letters. The 11 sequences from B. dorsalis and one from Z. tau (removed due to shorter length) group with Cardinium sequences found in Encarsia pergandiella and Plagiomerus diaspidis. Bayesian posterior probabilities based on 1000 replicates are given (only values > 50% are indicated; Haloarcula quadrata used as outgroup). For each strain, their GenBank accession number is also given on the left. Parentheses on the right of the name indicate number of sequences from that population

Detection of Wolbachia pseudogenes

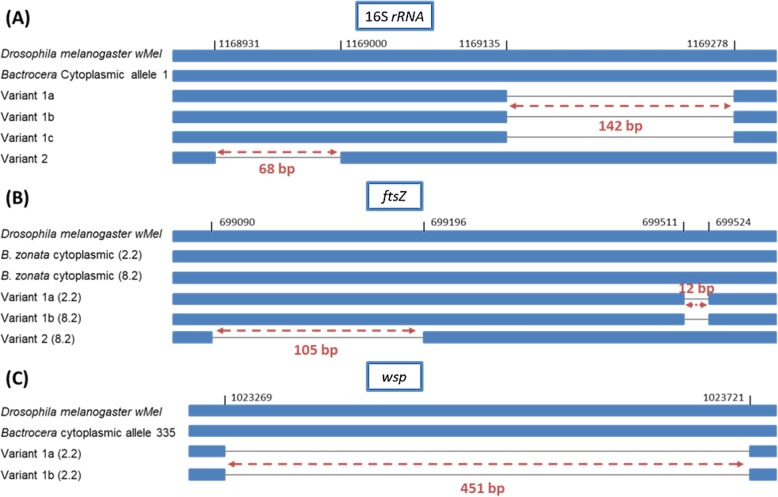

The presence of two distinct PCR amplification products was observed for the 16S rRNA gene in samples from four Bactrocera populations during theWolbachia-specific 16S rRNA-based screening (Table 3). The first product had the expected 438 bp size while the second was 296 bp (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the populations of B. nigrofemoralis from Palampur, India and B. zonata from Rajshahi, Bangladesh were found to contain only the smaller pseudogenized sequence. On the contrary, other samples from India including, B. correcta (sample 01.5H) andB. dorsalis from Trombay, B. scutellaris from Palampur and B. zonata from Raichur, contained only the expected 438 bp fragment (Table 3). When sequenced, both PCR products appeared to be of Wolbachia origin. The 438 bp product corresponded to the expected 16S rRNA gene fragment, while the shorter product contained a deletion of 142 bp (Fig. 5a). The 296 bp short version of the gene was detected in seven individuals from various Bactrocera species, including B. correcta, B. dorsalis,B. nigrofemoralis and B. zonata. Three different types of deletions were found, with minor changes in their nucleotide sequence compared to the cytoplasmic Wolbachia 16S rRNA gene fragment found in Drosophila melanogaster and various Bactrocera species in this study (Fig. 5a). Zeugodacus cucurbitae from Dinajpur, Bangladesh contained only pseudogenized Wolbachia 16S rRNA gene sequences. In this case, however the deletion was only 68 bp and the resulting pseudogene had a size of 370 bp (Fig. 5a). The presence of distinct amplicons was also observed duringWolbachia MLST analysis for genesftsZ and wsp. In both cases, apart from the expected PCR product, a smaller fragment was also detected (Fig. 5b, c). Multiple ftsZ gene products were found in two samples (2.2 and 8.2) belonging to the population ofB. zonata from Trombay, India. Two different short amplicons were observed. Sequence analysis revealed that the large product had the expected size of 524 bp while the short ones were either 512 bp or 419 bp long (Fig. 5b). The 512 bp fragment contained a small deletion of 12 bp while the 419 bp one, a much larger of 105 bp. The 419 bp fragment was only detected in sample 8.2. In the case of the 512 bp fragment, two different variants were found with minor changes in their sequence (Fig. 5b). Two distinct PCR products were also observed during amplification of the wsp gene in sample 2.2 of B. zonata from India (Trombay) (Fig. 5c). After sequence analysis, the larger product appeared to have the expected 606 bp size while the second was significantly smaller, consisting of only 155 bp. Two such pseudogenes were found in this case, with minor differences in their sequence (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Overview of three Wolbachia pseudogenes carrying deletions of various sizes. The 16S rRNA,ftsZ and wsp gene fragments of Wolbachia chromosomal insertions sequenced from natural Bactrocera and Zeugodacus populations aligned with the corresponding regions of strain wMel and Wolbachia strains infecting Bactrocera flies (cytoplasmic). Grey lines represent the deletion region. The black numbers show the positions before and after the deletions in respect to thewMel genome. The red arrows and numbers indicate the size of deletion in base pairs. Variants exhibit small number of SNPs. aVariant 1a: B. zonata (Bangladesh, Rajshahi, 03.3B), B. correcta (India, Trombay, 1.4), B. dorsalis (India, Palampur, 02.11D), B. nigrofemoralis (India, Palampur, 02.10G),B. zonata (India, Trombay, 2.2). Variant 1b:B. dorsalis (Bangladesh, Rajshahi, 03.7D), B. dorsalis (India, Palampur, 02.11D), B. zonata (India, Trombay, 8.2). Variant 1c: B. correcta (India, Trombay, 1.4).Variant 2: Z. cucurbitae (Bangladesh, Dinajpur, 07.10H). b Deletions in the ftsZ gene were identified in two B. zonata samples, B. zonata (India, Trombay, 2.2) and B. zonata (India, Trombay, 8.2). Sample 8.2 carried two different types of deletions. (C) B. zonata (India, Trombay, 2.2) contained wsp pseudogenes with two different types of deletions

Discussion

In this study, Wolbachia, Entomoplasmatales and Cardinium infections were identified in several Bactrocera and Zeugodacus species. Interestingly, none of the examined populations contained sequences belonging to Arsenophonus.

Infections prevalence

The prevalence of Wolbachia infections was found to vary between different species. For the first time, infections were detected in B. scutellaris and B. zonata. In the case of B. correcta, a previous study on wild samples from Thailand reported a higher infection rate (50%) than the one observed in our work (33%), but was based on only two screened individuals [94]. Contrary to the infection rate we detected in B. dorsalis (13.2%), most wild and laboratory populations examined up to date, were found to harbor noWolbachia infections [94–96]. However, there are two cases of activeWolbachia infections that have been reported in B. dorsalis from Thailand. One is a low rate infection (0.9%; 2 individuals out of 222) and the other shows medium prevalence (50%) but is based only on one infected sample [94]. On the other hand, no Wolbachia infections were present in B. minax, B. nigrofemoralis, D. longicornis, Z. cucurbitae andZ. tau. It is noteworthy that previous studies reported infections, but overall with very low prevalence, in Z. cucurbitae (4.2%) and Z. tau (1%) [94]. Recently, Wolbachia endosymbiont of Culex quinquefasciatus Pel was detected as the dominant species, with ~ 98% prevalence, in all the life stages studied in samples of B. latifrons (Hendel) from Malaysia using next-generation sequencing [97]. This occurrence is notably higher than any otherBactrocera species originating from Southeast Asia and Oceania.

Most of the Wolbachia-infected populations were found in India, in areas located in the far North (Palampur), close to the West coast (Trombay) as well as in the South (Raichur). Only one infected population was detected in Bangladesh, close to the city of Rajshahi, on the western border with India. In the case of B. zonata, the presence of Wolbachia decreased and eventually the infection was lost as we moved towards the North and away from the equator. Otherwise, this trend could mean that the infection is currently spreading from South to North. At the same time, infections in B. dorsalis exhibited the exact opposite behavior. The low prevalence infection detected in the population originating from Rajshahi, in western Bangladesh, close to the border with India, could be the result of a current spreading from the neighboring infected Indian populations. No individuals from Raichur were screened, so the picture of the infection in B. dorsalis further to the South is incomplete. Infected populations of B. correcta followed a similar pattern to B. dorsalis. In this case, however, no population from Northern India (Palampur) was included in the screen. Finally, it was impossible to determine a trend in the case of B. scutellaris since the only infected population was found in the North of India (Palampur).

Low density (< 10%) Entomoplasmatales infections were detected in multiple Zeugodacus and Bactrocera species. Previous screenings of laboratory populations of five Bactrocera species did not reveal any infections with members of the Entomoplasmatales [95]. Spiroplasma infections, the only genus within the order with species known to induce reproductive phenotypes, were identified in B. dorsalis and Z. cucurbitae with much lower frequencies (~ 1%) compared to other fly species belonging to the genera of Drosophila (0–53%) [38, 98]Glossina (5.8–37.5%) [75] and Phlebotomus (12.5%) [99]. The geographical distribution of infected populations appeared to be widespread in various areas of Bangladesh and India. In bothB. dorsalis and B. zonata, subtropical and tropical populations were generally characterized by similar infection rates with little fluctuation, suggesting that geography does not influence the dispersion of infections. For the remaining fruit fly species infected with Entomoplasmatales, we could not extract any useful information about the geographical distribution of infections either due to the presence of only one infected population or due to the proximity of infected populations.

Populations infected with Cardinium originated only from subtropical regions and harbored either medium or low prevalence infections. Previously, 244 species of flies belonging to the Empidoidea (Order: Diptera), which consists of four families such as the long-legged flies (Family: Dolichopodidae) and the dance flies (Family: Hybotidae), were found to contain Cardinium infections in only ten species, with an incidence rate of 4% [28]. A similar study in various arthropods did not identify any Cardinium sequences in the seven families of Diptera studied [33] while laboratory populations of various Bactrocera species were also free of Cardinium infections [95]. However, higher occurrence of Cardinium was identified inCulicoides biting midge species (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) with infection rates reaching up to 50.7, 72 or 100% [80, 100]. It seems that a wide range ofCardinium infections can be found in different fly species.

Genotyping - phylogeny

The 16S rRNA, MLST and wsp-based sequence analysis results are in accordance with a previous study that was based on 16S rRNA and wsp phylogeny, in which Wolbachia strains infecting variousBactrocera species from Australia, likeB. bryoniae (Tryon), B. decurtans (May), B. frauenfeldi (Schiner) and B. neohumeralis (Hardy), were clustered in supergroup A [96]. Another study, based on the ftsZ and wsp genes, identified strains belonging to both supergroups A and B, in samples from Thailand from various species including, B. ascita (Hardy), B. diversa (Coquillett) and B. dorsalis [101], even though a previous work on the same samples found strains belonging mostly to supergroup B, except for those found in B. tau (now Z. tau) that belonged to supergroup A [94]. The phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence revealed the presence of closely related Wolbachia strains in different Bactrocera species (Fig. 1), which could be the result of horizontal transmission between insect species, as has been previously reported in the case of the parasitic wasp genus Nasonia and its fly hostProtocalliphora [102] as well as in other insects [70, 103–105]. In addition, populations of various species, including B. correcta, B. dorsalis,B. scutellaris and B. zonata from different locations harbor very closely related Wolbachia strains, suggesting that the geographical origin of their hosts did not lead to Wolbachia strain divergence. However, some divergence was observed between samples of the same species (e.g. B. correcta) from the same population (Trombay; subgroups A1, and A3), and between different populations of a species (e.g.B. zonata; Trombay and Raichur; A2 and A3 respectively). Distantly related Wolbachia strains were seen between different B. dorsalis populations, but also in samples from the same population (Trombay, A3 and B). Strains belonging to supergroups A and B have been previously found to occur in the same species [102, 106]. The same picture, with closely related strains between different species and a distantly related strain from B. dorsalis from Trombay, was also seen in the MLST/wsp based phylogeny. Some degree of divergence was also observed between B. zonata samples of the same population (Trombay) similar to the one observed in the 16S rRNA gene-based phylogeny.

Phylogenetic analysis on the 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed that most Entomoplasmatales strains grouped with the closely related species Mesoplasma corruscae and Entomoplasma ellychniae. Overall, three samples were found to carry Spiroplasma infections. Two of the 16S rRNA gene sequences were classified into the ixodetis group and one into the citri-chrysopicola-mirum group. Spiroplasma strains infecting tsetse flies were also clustered in the citri-chrysopicola-mirum group [75]. On the other hand, S. ixodetis is mostly found in ticks [107–109]. AllCardinium strains described in this study were similar to the strain infecting the parasitic wasp Encarsia pergandiella (Order: Hymenoptera). Similar strains were also found in other parasitic wasps of the genus Encarsia as well as in armored scale insects (Order: Hemiptera) like Aspidiotus nerii and Hemiberlesia palmae [37].

Wolbachia pseudogenes

In the present study, three Wolbachia genes, 16S rRNA,ftsZ and wsp, were found to harbor deletions of various sizes in their sequence. The most common pseudogenes were identified in the case of the 16SrRNA gene, in four Bactrocera species and Z. cucurbitae (Fig. 5a) while shorter copies of theftsZ and wsp genes were found only in B. zonata. It is worth mentioning that pseudogenized sequences were found both in populations that harbored presumably active Wolbachia infections and in uninfected ones. Interestingly, the 16S rRNA and ftsZ pseudogenes were similar to those described previously in Glossina species [86], which were shown to be incorporated in the host genome. The similarity in sequence with the Glossina pseudogenes, along with the lack of amplification of all marker genes (MLST and wsp), could suggest that the identified pseudogenes may be integrated into the genome ofBactrocera flies. Wolbachia pseudogenes (16S rRNA, wsp, coxA, hcpA andfbpA) have been previously identified in two Bactrocera species (B. peninsularis (Drew & Hancock) and B. perkinsi) from tropical Australian populations with amplification results also suggesting horizontal gene transfer to the host genome [96]. Even though horizontal gene transfer is much more common between prokaryotes, many cases have been described between endosymbiotic bacteria and their insect hosts [82]. These interactions may have significant impact on the genomic evolution of the invertebrate hosts. PseudogenizedWolbachia sequences and horizontal transfer events have been reported in various Wolbachia-infected hosts [83–86, 89, 90, 92, 93]. It is worth noting that in some cases horizontally transferred Wolbachia genes are expressed from the host genome, as reported in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum [89, 92, 93].

Conclusions

Wolbachia, Cardinium, Spiroplasma and its close relatives, Entomoplasma and Mesoplasma, are present in wild populations ofBactrocera and Zeugodacus species from Southeast Asia. Strain characterization and phylogenetic analyses were performed primarily with the 16S rRNA gene and additionally, in the case of Wolbachia, with the wsp and MLST gene markers, revealing the presence of supergroup A and B Wolbachia strains along with new and previously identified Wolbachia MLST and wsp alleles, Spiroplasma strains belonging to the citri-chrysopicola-mirum and ixodetis groups as well as sequences clustering with Mesoplasma and Entomoplasma species, and finally group A Cardinium species similar to those infecting Encarsia pergandiella and Plagiomerus diaspidis. Even though the geographical map of infections is incomplete, it seems that Wolbachia are more common in Indian populations and possibly spreading to neighboring countries, while Entomoplasmatales infections are widespread in both Indian and Bangladeshi populations. Fruit flies infected with these bacterial taxa were found in both tropical and subtropical regions. On the other hand, Cardinium infections were less common and were only found in subtropical populations. The detection of Wolbachia pseudogenes, containing deletions of variable size, implies putative events of horizontal gene transfer in the genome of the tephritid fruit fly populations studied which could be remnants of past infections. Further study of additional species and wild populations could provide a more detailed report of the infection status for these specific endosymbiotic bacteria that may function as reproductive parasites. The detailed characterization of existing strains could shed more light on the host-symbiont interactions, which could be potentially harnessed for the enhancement of the sterile insect technique (SIT) and related techniques as components of area-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM) strategies for the control of insect pest populations.

Methods

Sample collection, preparation and DNA extraction

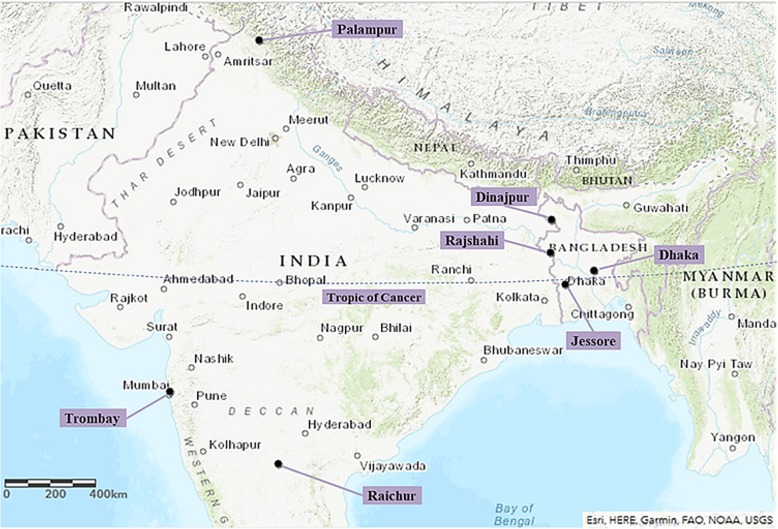

Analyzed samples belonged to nine species of fruit flies from three different Tephritidae genera: Bactrocera,Dacus and Zeugodacus. A total of 801 adult male fruit flies were collected from 30 natural populations originating from various regions of Bangladesh, China and India and stored in absolute ethanol Fig. 6 (Table 1). DNA extraction was performed immediately after the arrival of the samples in the laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at the University of Patras. Total DNA was extracted from the whole body of adult flies using the NucleoSpin® Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Prior to extraction, the insects were washed with sterile deionized water to remove any traces of ethanol. Each sample contained one fly (n = 1). Extracted DNA was stored at − 20 °C.

Fig. 6.

Map showing tropical (south of the Tropic of Cancer (dotted line)) and subtropical (north) sampling locations in Bangladesh and India (created with ArcGIS, by Esri)

PCR screening and Wolbachia MLST

The presence of reproductive symbiotic bacteria that belong to the genera Wolbachia, Spiroplasma (and the other two genera of the Entomoplasmatales,Entomoplasma and Mesoplasma), Cardinium andArsenophonus in natural populations of tephritid fruit flies was investigated with a 16S rRNA gene-based PCR assay. A fragment of variable size (301–600 bp) was amplified with the use of specific primers for each bacterial genus (Additional file 2). In the case of Wolbachia strains, the specific 16SrRNA PCR assay that was employed was described previously [86]. Prior to screening, the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene was used as positive control for PCR amplification. A 377 bp fragment of the gene was amplified in all samples tested with the primers 12SCFR and 12SCRR [110]. Also, amplification of an approximately 800 bp long fragment of host mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene was carried out with primers “Jerry” and “Pat” [111] in order to perform molecular characterization of the samples tested and to confirm successful DNA extraction (Additional file 3). Amplification was performed in 20 μl reactions using KAPA Taq PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems). Each reaction contained 2 μl of 10X KAPA Taq Buffer, 0.2 μl of dNTP solution (25 mM each), 0.4 μl of each primer solution (25 μM), 0.1 μl of KAPA Taq DNA Polymerase solution (5 U/μl), 1 μl from the template DNA solution and was finalized with 15.9 μl of sterile deionized water. For each set of PCR reactions performed, the appropriate negative (no DNA) and positive controls were also prepared. The PCR protocol was comprised of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 95 °C, annealing for 30 s at the required annealing temperature (Ta) for every pair of primers (54 °C for Wolbachia, 56 °C forArsenophonus and Cardinium, 58 °C for Spiroplasma, 54 °C for the 12S rRNA gene and 49 °C for mtCOI) and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. A final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 5 min.

In order to genotype the Wolbachia strains present in infected specimens (Table 3), fragments of the MLST (gatB, coxA,hcpA, fbpA and ftsZ) and wsp genes were amplified with the use of their respective primers [74] (Additional file 2). Ten Wolbachia-infected populations (three Bangladeshi and seven Indian) were initially selected for genotyping using the MLST and wsp genes. Efforts were made to amplify the MLST genes in all selected samples, however, most PCRs failed, resulting in the successful amplification of all the MLST genes for only four samples (Table 3). Due to these difficulties, the characterization of the bacterial strains present in the remaining infected flies was limited to the 16S rRNA gene. The four samples that were amplified belonged to three Bactrocera species, B. correcta, B. dorsalis, andB. zonata (Table 3). Amplification was performed in 20 μl reactions with the following PCR mix: 2 μl of 10X KAPA Taq Buffer, 0.2 μl of dNTP mixture (25 mM each), 0.4 μl of each primer solution (25 μM), 0.1 μl of KAPA Taq DNA Polymerase solution (5 U/μl), 1 μl from the template DNA solution and 15.9 μl of sterile deionized water. PCR reactions were performed using the following program: 5 min of denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at the appropriate temperature for each primer pair (52 °C forftsZ, 54 °C for gatB, 55 °C for coxA, 56 °C for hcpA, 58 °C for fbpA and wsp), 1 min at 72 °C and a final extension step of 10 min at 72 °C.

Due to products of variable size and the presence of multiple infections, we selected one representative sample from each Wolbachia-infected species population and cloned the PCR products of the Wolbachia 16SrRNA, wsp and MLST genes (Table 3) into a vector (pGEM-T Easy Vector System, Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ligation product was used to transform DH5α competent cells, which were plated on ampicillin/X-gal selection Petri dishes. At least three clones were amplified by colony PCR [112] with primers T7 and SP6 (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc.). Amplification was performed in 50 μl reactions each containing: 5 μl of 10X KAPA Taq Buffer, 0.4 μl of dNTP mixture (25 mM each), 0.2 μl of each primer solution (100 μM), 0.2 μl of KAPA Taq DNA Polymerase solution (5 U/μl) and 44 μl of sterile deionized water. The PCR protocol consisted of 5 min of denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 53 °C, 2 min at 72 °C and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min.

Sample purification and sanger sequencing

Throughout the experimental procedure, imaging of the desired amplification products was performed in a Gel Doc™ XR+ system (Bio-Rad) after loading 5 μl from each PCR reaction on 1.5% (w/v) agarose gels and separating them by electrophoresis. Purification of the PCR products was carried out with a 20% PEG, 2.5 M NaCl solution as previously described [113]. The concentration of purified PCR product was measured with a Quawell Q5000 micro-volume UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Purified PCR products were sequenced using the appropriate primers in each case (Additional file 2) while clonedWolbachia PCR products were sequenced with the universal primers T7 and SP6. In this case, at least three transconjugants were sequenced as previously described [86]. A dye terminator-labelled cycle sequencing reaction was conducted with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). Reaction products were purified using an ethanol/EDTA protocol according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems) and were analyzed in an ABI PRISM 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analysis

All gene sequences used in this study were aligned using MUSCLE, [114] with the default algorithm parameters, as implemented in Geneious 6.1.8 [115] and manually edited. Statistical significance of pairwise comparisons of infection prevalence between different species of fruit flies, areas or countries were calculated with chi-squared tests which were performed with R 3.5.1 [116]. The null hypothesis (H0) assumed that the variables (infection status between different species, areas or countries) were independent, and the significance level was equal to 0.05.P-values are presented in the text only for comparisons that show statistical significance. Alignments used in phylogenetic analyses were performed with MUSCLE [114] using the default algorithm parameters, as implemented in Geneious 6.1.8 [115]. Phylogenetic analyses of the 16S rRNA gene sequences and the concatenated sequences of the protein-coding MLST genes (coxA, fbpA, ftsZ, gatB and hcpA) were based on Bayesian Inference (BI). Bayesian analyses were performed with MrBayes 3.2.1 [117]. The evolutionary model was set to the Generalised Time Reversible (GTR) model with gamma-distributed rate variation and four gamma categories used. The parameters for the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method included four heated chains, with the temperature set to 0.2, which were run for 1,000,000 generations. The first 10,000 generations were discarded, and the cold chain was sampled every 100 generations. Also, posterior probabilities were computed for the remaining trees. All phylogenetic analyses were performed with Geneious [115]. All MLST, wsp and 16S rRNA gene sequences generated in this study have been deposited into GenBank under accession numbers MK045503-MK045529 and MK053669-MK053774.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Prevalence of reproductive bacteria in tephritid fruit fly populations from Bangladesh, China and India using a 16S rRNA gene-based PCR screening approach. Red values in the heat map indicate high occurrence and blue values low. For each genus the absolute number and the percentage (in parentheses) of infected individuals are given. The last column on the right (“Total*”) indicates the total occurrence of all three Entomoplasmatales genera.

Additional file 2. Genes and PCR primers used.

Additional file 3. Bayesian inference phylogeny tree based on host mtDNA COI (~ 800 bp). Bayesian posterior probabilities based on 1000 replicates are given (only values > 50% are indicated).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Microbiology Volume 19 Supplement 1, 2019:Proceedings of an FAO/IAEA Coordinated Research Project on Use of Symbiotic Bacteria to Reduce Mass-rearing Costs and Increase Mating Success in Selected Fruit Pests in Support of SIT Application: microbiology. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-1.

Abbreviations

- AW-IPM

Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management

- CFB

Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides

- CI

Cytoplasmic Incompatibility

- GTR

Generalised Time Reversible

- HGT

Horizontal Gene Transfer

- HVR

Hypervariable Region

- MCMC

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- MLST

Multi Locus Sequence Typing

- SIT

Sterile Insect Technique

- ST

Sequence Type

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the study: KB, GT. Conducted the experiments and analyzed the results: EA, MK, CB, RH, AH, CN, VD, GT. Drafted the manuscript: EA, GT. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was: (a) partially supported by the International Atomic Energy research contact no. 17074 as part of the Coordinated Research Project “Use of Symbiotic Bacteria to Reduce Mass-Rearing Costs and Increase Mating Success in Selected Fruit Pests in Support of SIT Application” and by intramural funds of the University of Patras to George Tsiamis, (b) partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31661143045) to Changying Niu and (c) partially supported by the International Atomic Energy research contact no. 17090 and 17011 as part of the Coordinated Research Project “Use of Symbiotic Bacteria to Reduce Mass-Rearing Costs and Increase Mating Success in Selected Fruit Pests in Support of SIT Application” to Ramesh Hire and Mahfuza Khan respectively.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in NCBI.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Elias D. Asimakis, Email: eliasasim@upatras.gr

Vangelis Doudoumis, Email: e.doudoumis@teiwest.gr.

Ashok B. Hadapad, Email: ahadapad@barc.gov.in

Ramesh S. Hire, Email: rshire@barc.gov.in

Costas Batargias, Email: batc@teimes.gr.

Changying Niu, Email: niuchangying88@163.com.

Mahfuza Khan, Email: mahfuza79@gmail.com.

Kostas Bourtzis, Email: K.Bourtzis@iaea.org.

George Tsiamis, Email: gtsiamis@upatras.gr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12866-019-1653-x.

References

- 1.Duron O, Bouchon D, Boutin S, Bellamy L, Zhou L, Engelstädter J, et al. The diversity of reproductive parasites among arthropods: Wolbachia do not walk alone. BMC Biol. 2008;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werren JH. Biology of Wolbachia. Annu Rev Entomol. 1997;42:587–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:741–751. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Neill SL, Hoffmann A, Werren J. Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997.

- 5.Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? – a statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werren JH, Windsor D, Guo L. Distribution of Wolbachia among neotropical arthropods. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1995;262:197–204. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werren JH, Windsor DM. Wolbachia infection frequencies in insects: evidence of a global equilibrium? Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2000;267:1277–1285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zug R, Hammerstein P. Still a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Oliveira CD, Gonçalves DS, Baton LA, Shimabukuro PHF, Carvalho FD, Moreira LA. Broader prevalence of Wolbachia in insects including potential human disease vectors. Bull Entomol Res. 2015;105:305–315. doi: 10.1017/S0007485315000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sazama EJ, Bosch MJ, Shouldis CS, Ouellette SP, Wesner JS. Incidence of Wolbachia in aquatic insects. Ecol Evol. 2017;7:1165–1169. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes GL, Allsopp PG, Brumbley SM, Woolfit M, McGraw EA, O’Neill SL. Variable infection frequency and high diversity of multiple strains of Wolbachia pipientis in Perkinsiella planthoppers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2165–2168. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02878-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun X, Cui L, Li Z. Diversity and phylogeny of Wolbachia infecting Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) populations from China. Environ Entomol. 2007;36:1283–1289. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X(2007)36[1283:DAPOWI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beard CB, Durvasula RV, Richards FF. Bacterial symbiosis in arthropods and the control of disease transmission. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:581–591. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourtzis K, O’Neill S. Wolbachia infections and arthropod reproduction: Wolbachia can cause cytoplasmic incompatibility, parthenogenesis, and feminization in many arthropods. BioScience. 1998;48:287–293. doi: 10.2307/1313355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brucker RM, Bordenstein SR. Speciation by symbiosis. Trends Ecol Evol. 2012;27:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlat S, Hurst GDD, Merçot H. Evolutionary consequences of Wolbachia infections. Trends Genet. 2003;19:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kageyama D, Narita S, Watanabe M. Insect sex determination manipulated by their endosymbionts: incidences, mechanisms and implications. Insects. 2012;3:161–199. doi: 10.3390/insects3010161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris HL, Brennan LJ, Keddie BA, Braig HR. Bacterial symbionts in insects: balancing life and death. Symbiosis. 2010;51:37–53. doi: 10.1007/s13199-010-0065-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurst GDD, Jiggins FM, von der Schulenburg JHG, Bertrand D, West SA, Goriacheva II, et al. Male-killing Wolbachia in two species of insect. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 1999;266:735. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JA, GDD H. Wolbachia pipientis: microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:71–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Grève P. The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms. Trends Genet. 2011;27:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourtzis K, Miller T. Insect symbiosis. USA: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, LLC, Florida; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotoh T, Noda H, Ito S. Cardinium symbionts cause cytoplasmic incompatibility in spider mites. Heredity. 2007;98:13–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weeks AR, Marec F, Breeuwer JAJ. A mite species that consists entirely of haploid females. Science. 2001;292:2479–2482. doi: 10.1126/science.1060411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zchori-Fein E, Perlman SJ, Kelly SE, Katzir N, Hunter MS. Characterization of a ‘Bacteroidetes’ symbiont inEncarsia wasps (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae): proposal of ‘Candidatus Cardinium hertigii.’. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:961–968. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02957-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenyon SG, Hunter MS. Manipulation of oviposition choice of the parasitoid wasp, Encarsia pergandiella, by the endosymbiotic bacterium Cardinium. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:707–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie R-R, Zhou L-L, Zhao Z-J, Hong X-Y. Male age influences the strength of Cardinium-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility expression in the carmine spider mite Tetranychus cinnabarinus. Appl Entomol Zool. 2010;45:417–423. doi: 10.1303/aez.2010.417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin Oliver Y., Puniamoorthy Nalini, Gubler Andrea, Wimmer Corinne, Germann Christoph, Bernasconi Marco V. Infections with the MicrobeCardiniumin the Dolichopodidae and Other Empidoidea. Journal of Insect Science. 2013;13(47):1–13. doi: 10.1673/031.013.4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao D-X, Zhang X-F, Hong X-Y. Host-symbiont interactions in spider mite Tetranychus truncates doubly infected withWolbachia and Cardinium. Environ Entomol. 2013;42:445–452. doi: 10.1603/EN12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gherna RL, Werren JH, Weisburg W, Cote R, Woeste CR, Mandelco L, et al. Arsenophonus nasoniae gen. nov., sp. nov., the causative agent of the son-killer trait in the parasitic waspNasonia vitripennis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:563-5.

- 31.Montenegro H, Solferini V. N., Klaczko L. B., Hurst G. D. D. male-killingSpiroplasma naturally infectingDrosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol Biol. 2005;14:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tinsley MC, Majerus MEN. A new male-killing parasitism: Spiroplasma bacteria infect the ladybird beetleAnisosticta novemdecimpunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) Parasitology. 2006;132:757–765. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005009789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zchori-Fein E, Perlman JS. Distribution of the bacterial symbiont Cardinium in arthropods. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:2009–2016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinert Lucy A., Araujo-Jnr Eli V., Ahmed Muhammad Z., Welch John J. The incidence of bacterial endosymbionts in terrestrial arthropods. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;282(1807):20150249. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y-K, Chen Y-T, Yang K, Hong X-Y. A review of prevalence and phylogeny of the bacterial symbiont Cardinium in mites (subclass: Acari) Syst Appl Acarol. 2016;21:978–990. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura Y, Kawai S, Yukuhiro F, Ito S, Gotoh T, Kisimoto R, et al. Prevalence of Cardinium bacteria in planthoppers and spider mites and taxonomic revision of “Candidatus Cardinium hertigii” based on detection of a new Cardinium group from biting midges. Appl Env Microbiol. 2009;75:6757–6763. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01583-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruwell ME, Wu J, Normark BB. Diversity and phylogeny of Cardinium (Bacteroidetes) in armored scale insects (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2009;102:1050–1061. doi: 10.1603/008.102.0613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watts T, Haselkorn TS, Moran NA, Markow TA. Variable incidence of Spiroplasma infections in natural populations of Drosophila species. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkes T, Duron O, Darby AC, Hypsa V, Novakova E, Hurst GDD. The genus Arsenophonus. In: Bourtzis K, Zchori-Fein E, editors. Manipulative tenants. USA: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, LLC, Florida; 2011. pp. 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Jiang J, Xu Y, Zeng L, Lu Y. Occurrence of three intracellular symbionts (Wolbachia, Arsenophonus, Cardinium) among ants in southern China. J Asia Pac Entomol. 2016;19:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2016.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jousselin E, d’Acier AC, Vanlerberghe-Masutti F, Duron O. Evolution and diversity of Arsenophonus endosymbionts in aphids. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:260–270. doi: 10.1111/mec.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skinner SW. A third extrachromosomal factor affecting the sex ratio in the parasitoid wasp, Nasonia (=Mormoniella) vitripennis. Genetics. 1985;109:745–759. doi: 10.1093/genetics/109.4.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drew R. Biogeography and speciation in the Dacini (Diptera: Tephritidae: Dacinae) Bish Mus Bull Entomol. 2004;12:165–178. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drew R. The tropical fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae: Dacinae) of the Australasian and Oceanian regions. Mem Qld Mus. 1989;26:521. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krosch MN, Schutze MK, Armstrong KF, Graham GC, Yeates DK, Clarke AR. A molecular phylogeny for the tribe Dacini (Diptera: Tephritidae): systematic and biogeographic implications. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;64:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Virgilio M, Jordaens K, Verwimp C, White IM, De Meyer M. Higher phylogeny of frugivorous flies (Diptera, Tephritidae, Dacini): localised partition conflicts and a novel generic classification. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;85:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cugala DR, Meyer MD, Canhanga LJ. Integrated management of fruit flies – case studies from Mozambique. In: Fruit fly research and development in Africa - towards a sustainable management strategy to improve horticulture. Cham: Springer; 2016. pp. 531–552. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhillon MK, Singh R, Naresh JS, Sharma HC. The melon fruit fly,Bactrocera cucurbitae: a review of its biology and management. J Insect Sci. 2005;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Jessup AJ, Dominiak B, Woods B, Lima CPFD, Tomkins A, Smallridge CJ. Area-wide control of insect pests. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. Area-wide management of fruit flies in Australia; pp. 685–697. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vargas RI, Piñero JC, Leblanc L, Manoukis NC, Mau RFL. Fruit fly research and development in Africa - towards a sustainable management strategy to improve horticulture. Cham: Springer; 2016. Area-wide management of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Hawaii; pp. 673–693. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alam U, Medlock J, Brelsfoard C, Pais R, Lohs C, Balmand S, et al. Wolbachia symbiont infections induce strong cytoplasmic incompatibility in the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002415. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bourtzis K. Transgenesis and the Management of Vector-Borne Disease. New York: Springer; 2008. Wolbachia based technologies for insect pest population control; pp. 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dobson SL, Fox CW, Jiggins FM. The effect of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility on host population size in natural and manipulated systems. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;269:437–445. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dutra HLC, Rocha MN, Dias FBS, Mansur SB, Caragata EP, Moreira LA. Wolbachia blocks currently circulating zika virus isolates in Brazilian Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:771–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, Fong AWC, Sidhu M, Wang Y-F, et al. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2009;323:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1165326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saldaña MA, Hegde S, Hughes GL. Microbial control of arthropod-borne disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112:81–93. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zabalou S, Riegler M, Theodorakopoulou M, Stauffer C, Savakis C, Bourtzis K. Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:15042–15045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403853101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Dongjing, Lees Rosemary Susan, Xi Zhiyong, Bourtzis Kostas, Gilles Jeremie R. L. Combining the Sterile Insect Technique with the Incompatible Insect Technique: III-Robust Mating Competitiveness of Irradiated Triple Wolbachia-Infected Aedes albopictus Males under Semi-Field Conditions. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang D, Zheng X, Xi Z, Bourtzis K, Gilles JRL. Combining the sterile insect technique with the incompatible insect technique: I-impact of Wolbachia infection on the fitness of triple- and double-infected strains of Aedes albopictus. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Dongjing, Lees Rosemary Susan, Xi Zhiyong, Gilles Jeremie R. L., Bourtzis Kostas. Combining the Sterile Insect Technique with Wolbachia-Based Approaches: II- A Safer Approach to Aedes albopictus Population Suppression Programmes, Designed to Minimize the Consequences of Inadvertent Female Release. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bourtzis K, Robinson AS. Insect pest control using Wolbachia and/or radiation. In: Bourtzis K, Miller T, editors. Insect symbiosis 2. Florida: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, LLC; 2006. pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zabalou S, Apostolaki A, Livadaras I, Franz G, Robinson AS, Savakis C, et al. Incompatible insect technique: incompatible males from a Ceratitis capitata genetic sexing strain. Entomol Exp Appl. 2009;132:232–240. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Apostolaki A, Livadaras I, Saridaki A, Chrysargyris A, Savakis C, Bourtzis K. Transinfection of the olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae with Wolbachia: towards a symbiont-based population control strategy. J Appl Entomol. 2011;135:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2011.01614.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Atyame CM, Cattel J, Lebon C, Flores O, Dehecq J-S, Weill M, et al. Wolbachia-based population control strategy targeting Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes proves efficient under semi-field conditions. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Augustinos AA, Santos-Garcia D, Dionyssopoulou E, Moreira M, Papapanagiotou A, Scarvelakis M, et al. Detection and characterization of Wolbachia infections in natural populations of aphids: is the hidden diversity fully unraveled? PLoS One. 2011;6:e28695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bing X-L, Xia W-Q, Gui J-D, Yan G-H, Wang X-W, Liu S-S. Diversity and evolution of the Wolbachia endosymbionts of Bemisia (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) whiteflies. Ecol Evol. 2014;4:2714–2737. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerth M. Classification of Wolbachia (Alphaproteobacteria, Rickettsiales): no evidence for a distinct supergroup in cave spiders. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;43:378–380. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glowska E, Dragun-Damian A, Dabert M, Gerth M. New Wolbachia supergroups detected in quill mites (Acari: Syringophilidae) Infect Genet Evol. 2015;30:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ros VID, Fleming VM, Feil EJ, Breeuwer JAJ. How diverse is the genus Wolbachia? Multiple-gene sequencing reveals a putatively newWolbachia supergroup recovered from spider mites (Acari: Tetranychidae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1036–1043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01109-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang G-H, Jia L-Y, Xiao J-H, Huang D-W. Discovery of a new Wolbachia supergroup in cave spider species and the lateral transfer of phage WO among distant hosts. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;41:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Casiraghi M, Bordenstein SR, Baldo L, Lo N, Beninati T, Wernegreen JJ, et al. Phylogeny of Wolbachia pipientis based on gltA, groEL and ftsZ gene sequences: clustering of arthropod and nematode symbionts in the F supergroup, and evidence for further diversity in the Wolbachia tree. Microbiology. 2005;151:4015–4022. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O’Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert AM, Karr TL, Robertson HM. 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2699–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baldo L, Dunning Hotopp JC, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7098–7110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Doudoumis V, Blow F, Saridaki A, Augustinos A, Dyer NA, Goodhead I, et al. Challenging the Wigglesworthia,Sodalis, Wolbachia symbiosis dogma in tsetse flies: Spiroplasma is present in both laboratory and natural populations. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Gasparich GE, Whitcomb RF, Dodge D, French FE, Glass J, Williamson DL. The genus Spiroplasma and its non-helical descendants: phylogenetic classification, correlation with phenotype and roots of the Mycoplasma mycoides clade. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:893–918. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heres A, Lightner DV. Phylogenetic analysis of the pathogenic bacteriaSpiroplasma penaei based on multilocus sequence analysis. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]