Abstract

Objective:

A rare variant in TREM2 (p.R47H, rs75932628) has been consistently reported to increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease, while mixed evidence has been reported for association of the variant with other neurodegenerative diseases. Here, we investigated the frequency of the R47H variant in a diverse and well-characterized multicenter neurodegenerative disease cohort.

Methods:

We examined the frequency of the R47H variant in a diverse neurodegenerative disease cohort, including a total of 3,058 patients clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia spectrum syndromes, mild cognitive impairment, progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, corticobasal syndrome, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and 5,089 control subjects.

Results:

We observed a significant association between the R47H variant and Alzheimer’s disease, while no association was observed with any other neurodegenerative disease included in this study.

Conclusions:

Our results support the consensus that the R47H variant is significantly associated with Alzheimer’s disease. However, we did not find evidence for association of the R47H variant with other neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction

TREM2 encodes the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, a receptor involved in immune response that is expressed in the brain by microglia.1 The p.R47H (rs75932628)2,3 and other TREM2 rare variants4 have been shown to be associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but their role in other neurodegenerative diseases is still unclear. The R47H variant has been investigated as a possible risk variant for frontotemporal dementia (FTD), progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome (PSP-S), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Parkinson’s disease (PD) with inconsistent results. While Rayaprolu et al. reported association of the R47H variant with FTD (n = 609) and PD (n = 1493) but no association with ALS (n = 765) or PSP-S (n = 772)5, Cady et al. observed an association with ALS (n = 923)6, and a subsequent meta-analysis by Lill et al. did not find consistent association with FTD (n = 2673), PD (n = 8311), or ALS (n = 5544).7

This study aimed to assess whether the TREM2 p.R47H variant is associated with disease in a large series including 3,058 patients with neurodegenerative disease and 5,089 healthy control subjects.

Methods

Participants.

We included 3,058 patients with neurodegenerative disease and 5,089 controls recruited across collaborating centers worldwide (Supplementary Table 1):

(i) University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), (ii) University of California San Francisco Memory and Aging Center (UCSF-MAC series), (iii) Emory University (Emory), (iv) University of California San Francisco PSP series (UCSF-PSP), (v) University of California Davis (UCD), (vi) University of California Irvine (UCI), (vii) University of Southern California (USC), (viii) University of Brescia and San Raffaele Scientific Institute (ITA), (ix) Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project), (x) University of Athens (GRE), (xi) School of Medicine, Yale University (Turkish series), and (xii) National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH control series).

Patients consisted of individuals of 79.1% European ancestry, 9.9% African ancestry, 7.3% Asian ancestry, 1.8% Latin American ancestry, and 1.8% mixed or other ancestry. Controls consisted of individuals aged 65 or older, of 68.5% European ancestry, 28.5% African ancestry, 1.8% Asian ancestry, 0.9% Latin American ancestry, and 0.4% mixed or other ancestry. Patients were diagnosed with AD, ALS, FTD spectrum syndromes including behavioral variant FTD, semantic and nonfluent variants of primary progressive aphasia, PSP-S, corticobasal syndrome (CBS), and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics by disease series in a series of 3,058 patients and 5,089 controls

| Series | Total Individuals | R47H carriers | % Female | % European | Average Age at Onset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 1157 | 22 (1.90%) | 56.4 | 67.9 | 63.9 ±10.7 |

| FTD | 751 | 7 (0.93%) | 45.5 | 92.4 | 58.9 ±9.4 |

| MCI | 610 | 4 (0.66%) | 55.5 | 75.1 | 63.0 ±10.7 |

| PSP-S | 391 | 1 (0.26%) | 46.9 | 93.1 | 64.3 ±7.5 |

| CBS | 123 | 1 (0.81%) | 48.8 | 91.2 | 61.0 ±7.4 |

| ALS | 26 | 1 (3.85%) | 34.6 | 83.3 | 55.9 ±10.4 |

| Overall | 3058 | 36 (1.18%) | 51.9 | 79.1 | 62.0 ±10.2 |

| Control | 5089 | 22 (0.43%) | 57.4 | 68.5 | N/A |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, FTD: frontotemporal dementia, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PSP-S: progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, CBS: corticobasal syndrome, ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Overall refers to the combined neurodegenerative patient samples.

Age of onset was available in: AD (674/1157), FTD (524/751), MCI (245/610), PSP-S (121/391), CBS (112/123), ALS (19/26).

Gender was available in: AD (1085/1157), FTD (672/751), MCI (609/610), PSP-S (382/391), CBS (123/123), ALS (26/26), Controls (4550/5089).

Ancestry was available in: AD (1085/1157), FTD (605/751), MCI (594/610), PSP-S (363/391), CBS (113/123), ALS (24/26), Controls (4333/5089).

A multidisciplinary team including neurology, nursing, and project coordinators reviewed cases. Diagnosis protocol used the McKhann et al. (2011) criteria for AD and Albert et al. (2011) for the diagnosis of MCI due to AD, and the incorporation of AD biomarkers whenever they were available.8,9 The International bvFTD Criteria Consortium for bvFTD (Rascovsky et al., 2011), Gorno-Tempini et al. for primary progressive aphasia and its variants (2011), Armstrong et al. (2013) for CBS, and the Movement Disorder Society criteria for PSP-S (2017) were also used.10,11,12,13 A large aged control group was obtained from the NIMH Human Genetics Initiative. Inclusion criteria for the rest of our normal control cohort included availability of a reliable study partner with frequent contact, CDR score of zero, no subject or informant report of significant cognitive decline during the previous year, no evidence from the screening visit suggesting a neurodegenerative disorder (per the team’s clinical judgment), and MMSE score >25. Participants or their surrogates provided informed consent upon study enrollment.

Genetic Analysis.

Genotypes were obtained using TaqMan® SNP assays from ThermoFisher on a LightCycler® 480 System. A commercially available assay (C_100657057_10) for TREM2 R47H rs75932628 was used. Statistical analysis was performed in R (version 3.1.3, www.r-project.org). Association P-values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

We identified 35 p.R47H heterozygous carriers and 1 homozygous carrier (Table 1) among 3,058 patients with neurodegenerative disease, and 22 heterozygous carriers among control subjects. The allele frequency observed in the control group (0.23%) is similar to the 0.25% frequency reported by the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/6–41129252-C-T).

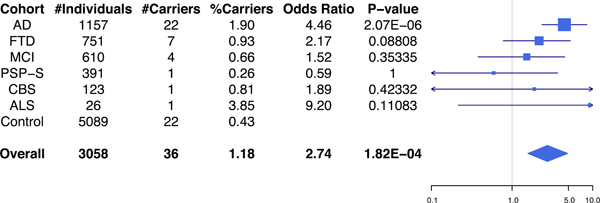

Combined analysis on the 3,058 patients resulted in an estimated OR of 2.74 (CI = 1.57–4.91, Fisher’s exact test, P = 1.82E-04) across neurodegenerative diseases versus controls (Figure 1). Analyses on the individual disease series produced odds ratios ranging from 0.59 (CI = 0.01–3.67, in the PSP-S series) to 9.20 (CI = 0.21–61.8, in the ALS series). However, the association was only significant for the AD series (OR = 4.46, CI = 2.35–8.48, Fisher’s exact test, P = 2.07E-06).

Figure 1: TREM2p.R47H carrier frequencies and associated odds ratios for the different disease series.

Total number of individuals and TREM2 p.R47H carriers for each disease series and control group is shown in the table (left), with odds ratios and P-values represented in the forest plot (right). AD: Alzheimer’s disease, FTD: frontotemporal dementia, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PSP-S: progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, CBS: corticobasal syndrome, ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Overall refers to the combined neurodegenerative disease patient samples. In the forest plot, squares are drawn proportional to the number of samples in each series, and lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Due to the unequal ethnicity distribution between case and control populations, we repeated the analysis on the subset of the series restricted to subjects of European descent (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2). Among the 2,203 patients and 2,969 controls of European descent, combined analysis across neurodegenerative diseases versus controls resulted in an OR of 2.29 (CI = 1.19–4.56, Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.00824). Analyses on the individual disease series resulted in odds ratios ranged from 0.55 (CI = 0.01–3.55, in the PSP-S series) to 9.69 (CI = 0.22–69.1, in the ALS series). As in the complete cohort, the association was only significant for the AD series (OR = 4.62, CI = 2.21—9.73, Fisher’s exact test, P = 1.70E-05).

Similar results were also obtained after excluding carriers of known causal variants (Supplementary Figure 2).

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the rare TREM2 R47H missense variant, which is located on the protein surface and affects ligand binding.1 The R47H variant has been repeatedly reported to confer an increased risk for AD.14,15,16,17,18 However, studies examining potential association of the R47H variant with other neurodegenerative diseases have generated mixed evidence.

To further examine the potential association of TREM2 with various neurodegenerative diseases, we assessed the risk effect of the R47H variant using a large multicenter neurodegenerative disease cohort comprised of AD, FTD, MCI, CBS, PSP-S, and ALS patients. We found the strongest risk association in the AD series (OR = 4.46, CI = 2.35–8.48, P = 2.07E-06), corroborating previous studies. Rayaprolu et al. (2013) reported association of the R47H variant with FTD diagnosis (n = 609).5 However, a subsequent meta-analysis (n = 2,673) incorporating results from Rayaprolu et al. (2013), produced only modest support for association with FTD, not reaching the suggested genome-wide significance threshold.7 No significant association was found in the FTD series (OR = 2.17, CI = 0.78–5.27, P = 0.088) in this study. We also observed no association within the MCI, PSP-S, CBS, or ALS series. However, it should be noted that statistical power was weak for our CBS (n = 123) and ALS (n = 26) series due to small sample size. Because of this, analyses on the CBS and ALS series produced odds ratios with large confidence intervals (CBS: OR = 1.89, CI = 0.05–11.9, P = 0.423) (ALS: OR = 9.20, CI = 0.21–61.7, P = 0.111).

In summary, our study confirms previous findings of association between the rare TREM2 R47H variant and an increased risk of AD. We also found no evidence of a risk association within FTD, MCI, PSP-S, and CBS series. Further genetic studies are needed to conclusively evaluate potential association of the R47H variant with other neurodegenerative disorders such as ALS and PD.

Supplementary Material

Total number of individuals and TREM2 p.R47H carriers for each disease series and control group (among the subset of participants remaining after excluding carriers of known causal variants) is shown in the table (left), with odds ratios and P-values represented in the forest plot (right). AD: Alzheimer’s disease, FTD: frontotemporal dementia, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PSP-S: progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, CBS: corticobasal syndrome, ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Overall refers to the combined neurodegenerative disease patient samples. In the forest plot, squares are drawn proportional to the number of samples in each series, and lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Total number of individuals and TREM2 p.R47H carriers for each disease series and control group (among the subset of participants of European descent) is shown in the table (left), with odds ratios and P-values represented in the forest plot (right). AD: Alzheimer’s disease, FTD: frontotemporal dementia, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PSP-S: progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, CBS: corticobasal syndrome, ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Overall refers to the combined neurodegenerative disease patient samples. In the forest plot, squares are drawn proportional to the number of samples in each series, and lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Acknowledgments

We thank contributors who collected samples used in this study, as well as patients and their families, whose help and participation made this work possible.

NIMH series. Control subjects from the National Institute of Mental Health Schizophrenia Genetics Initiative (NIMH-GI), data and biomaterials are being collected by the ‘Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia II’ (MGS-2) collaboration. The investigators and co-investigators are: Alan R. Sanders, MD; Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, MH59587, Farooq Amin, MD (PI); Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, MH067257, Nancy Buccola APRN, BC, MSN (PI); University of California-Irvine, Irvine, CA, MH60870, William Byerley, MD (PI); Washington University, St Louis, MO, U01, MH060879, C. Robert Cloninger, MD (PI); University of Iowa, Iowa, IA, MH59566, Raymond Crowe, MD (PI), Donald Black, MD; University of Colorado, Denver, CO, MH059565, Robert Freedman, MD (PI); University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, MH061675, Douglas Levinson, MD (PI); University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia, MH059588, Bryan Mowry, MD (PI); Mt Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, MH59586, Jeremy Silverman, PhD (PI).

Samples from the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease (NCRAD), which receives government support under a cooperative agreement grant (U24 AG21886) awarded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), were used in this study. We thank contributors who collected samples used in this study, as well as patients and their families, whose help and participation made this work possible.

This work was supported by the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation, NIH Grants R01 AG26938 and RC1 AG035610 (to G.C.). We acknowledge the support of the NINDS Informatics Center for Neurogenetics and Neurogenomics (P30 NS062691), NIA P01 AG1972403 and P50 AG023501 (to B.L.M.), Larry L. Hillblom Foundation Healthy Aging Network 2014-A-004-NET and National Institute on Aging RO1AG032289 (to J.K.). J.A.C. received fellowship support from NINDS (F31 NS084556). Italian Ministry of Health (grant number GR-2010-2303035 and GR-2011-02351217) (to F.A and M.F.). NIH grants P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917 (D.A.B.). We acknowledge the support of Parlow-Solomon Professorship; Stark Fund for Alzheimer’s Research (G.W.S.). P50 AG025688 (to AL). ADC P30 AG10129 (to C.S.D.).

Supported by NIH grants: John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation, NIH Grants R01 AG26938 and RC1 AG035610 (to G.C.). NIH grants P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917 (D.A.B.). The project was also supported by NINDS Informatics Center for Neurogenetics and Neurogenomics (P30 NS062691), NIA P01 AG1972403 and P50 AG023501 (to B.L.M.), Larry L. Hillblom Foundation Healthy Aging Network 2014-A-004-NET and National Institute on Aging RO1AG032289 (to J.K.). J.A.C. received fellowship support from NINDS (F31 NS084556). We acknowledge the support of the Italian Ministry of Health (grant number GR-2010-2303035 and GR-2011-02351217) (to F.A and M.F.), and the Parlow-Solomon Professorship; Stark Fund for Alzheimer’s Research (G.W.S.). P50 AG025688 (to AL). ADC P30 AG10129 (to C.S.D.).

Disclosure Statement

F.A. is Section Editor of NeuroImage: Clinical; has received speaker honoraria from Novartis and Biogen Idec; and receives or has received research supports from the Italian Ministry of Health, AriSLA (Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA), and the European Research Council. G.W.S. is an advisor/speaker for AARP, Allergan, Inc., Avanir, Axovant Sciences Ltd., Forum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Handok, Inc., Herbalife International, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Lily, Lundbeck, Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer, Inc., and Theravalues; equity interest in Taumark, LLC. J.A.C. is a founder and major shareholder of Verge Genomics, a San Francisco-based biotechnology company. M.F. is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Neurology; received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Biogen Idec, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; and receives research support from Biogen Idec, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Roche, Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, and ARiSLA (Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA).

Footnotes

A full disclosure statement with all possible conflicts of interest is available within the main manuscript.

References

- 1.Jay TR, von Saucken VE, Landreth GE. TREM2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurodegener. 2017. August 2;12(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013. January 10;368(2):107–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. Epub 2012 Nov 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013. January 10;368(2):117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. Epub 2012 Nov 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sims R, van der Lee SJ, Naj AC, et al. Rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 implicate microglial-mediated innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2017. September;49(9):1373–1384. doi: 10.1038/ng.3916. Epub 2017 Jul 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rayaprolu S, Mullen B, Baker M, et al. TREM2 in neurodegeneration: evidence for association of the p.R47H variant with frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2013. June 21;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cady J, Koval ED, Benitez BA, et al. TREM2 variant p.R47H as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014. April;71(4):449–53. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lill CM, Rengmark A, Pihlstrøm L, et al. The role of TREM2 R47H as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015. December;11(12):1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.12.009. Epub 2015 Apr 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011. 7(3):263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011. 7(3):270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011. 134(Pt 9):2456–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011. 76(11):1006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013. 80(5):496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M et al. and P.S.P.S.G. Movement Disorder Society-endorsed. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord. 2017. 32(6):853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellenguez C, Charbonnier C, Grenier-Boley B, et al. Contribution to Alzheimer’s disease of rare risk variants in TREM2, SORL1, and ABCA7 in 1779 cases and 1273 controls. Neurobiol Aging. 2017. November;59:220.e1–220.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.07.001. Epub 2017 Jul [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013. December;45(12):1452–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. Epub 2013 Oct 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benitez BA, Cooper B, Pastor P, et al. TREM2 is associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Spanish population. Neurobiol Aging. 2013. June;34(6):1711.e15–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.018. Epub 2013 Feb 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korvatska O, Leverenz JB, Jayadev S, et al. R47H Variant of TREM2 Associated With Alzheimer Disease in a Large Late-Onset Family: Clinical, Genetic, and Neuropathological Study. JAMA Neurol. 2015. August;72(8):920–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz A, Dols-Icardo O, Bullido MJ, et al. Assessing the role of the TREM2 R47H variant as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2014. February;35(2):444.e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.011. Epub 2013 Sep 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slattery CF, Beck JA, Harper L, et al. R47H TREM2 variant increases risk of typical early-onset Alzheimer’s disease but not of prion or frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 Nov;10(6):602–608.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1751. Epub 2014 Aug 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, et al. The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity. 2017. September 19;47(3):566–581.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Total number of individuals and TREM2 p.R47H carriers for each disease series and control group (among the subset of participants remaining after excluding carriers of known causal variants) is shown in the table (left), with odds ratios and P-values represented in the forest plot (right). AD: Alzheimer’s disease, FTD: frontotemporal dementia, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PSP-S: progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, CBS: corticobasal syndrome, ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Overall refers to the combined neurodegenerative disease patient samples. In the forest plot, squares are drawn proportional to the number of samples in each series, and lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Total number of individuals and TREM2 p.R47H carriers for each disease series and control group (among the subset of participants of European descent) is shown in the table (left), with odds ratios and P-values represented in the forest plot (right). AD: Alzheimer’s disease, FTD: frontotemporal dementia, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PSP-S: progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome, CBS: corticobasal syndrome, ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Overall refers to the combined neurodegenerative disease patient samples. In the forest plot, squares are drawn proportional to the number of samples in each series, and lines represent 95% confidence intervals.