Abstract

Purpose:

Paclitaxel shows little benefit in the treatment of glioma due to poor penetration across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPU) with microbubble injection transiently disrupts the BBB allowing for improved drug delivery to the brain. We investigated the distribution, toxicity and efficacy of LIPU delivery of two different formulations of paclitaxel—albumin-bound paclitaxel (ABX) and paclitaxel dissolved in cremophor (CrEL-PTX)—in pre-clinical glioma models.

Experimental Design:

The efficacy and biodistribution of ABX and CrEL-PTX were compared with and without LIPU delivery. Anti-glioma activity was evaluated in nude mice bearing intracranial patient-derived glioma xenografts (PDX). PTX biodistribution was determined in sonicated and non-sonicated nude mice. Sonications were performed using a 1 MHz LIPU device (SonoCloud®), and fluorescein was used to confirm and map BBB disruption. Toxicity of LIPU delivered paclitaxel was assessed through clinical and histological examination of treated mice.

Results:

Despite similar anti-glioma activity in-vitro, ABX extended survival over CrEL-PTX and untreated control mice with orthotropic PDX. Ultrasound-mediated BBB disruption enhanced paclitaxel brain concentration by 3-5 fold for both formulations and further augmented the therapeutic benefit of ABX. Repeated courses of LIPU delivered CrEL-PTX and CrEL alone was lethal in 42% and 37.5% of mice respectively, whereas similar delivery of ABX at an equivalent dose was well tolerated.

Conclusions:

Ultrasound delivery of paclitaxel across the BBB is a feasible and effective treatment for glioma. ABX is the preferred formulation for further investigation in the clinical setting due to its superior brain penetration and tolerability compared to CrEL-PTX.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Blood Brain Barrier, nab-Paclitaxel, Taxol, Abraxane, Glioblastoma, Brain Tumors, SonoCloud

Introduction:

The current standard of care for glioblastoma (GBM) patients involves surgical resection followed by adjuvant temozolomide chemoradiotherapy, and most recently the addition of tumor treating fields. [1] Nevertheless, GBM remains an ultimately fatal disease as over 90% of patients die within 5 years. Novel treatment strategies are urgently needed. One cause of the commonly observed resistance to conventional therapies is the inability to achieve adequate concentrations in the brain due to the protective blood-brain barrier (BBB). [2, 3]

While it is well established that the BBB is disrupted at the site of the tumor bulk, the BBB remains intact in the infiltrating and non-enhancing part of the tumor that is commonly the origin of subsequent tumor recurrence. [4–6] Many methods have been developed and tested to bypass the BBB to improve drug delivery for the treatment of GBM. These methods include convection-enhanced delivery (CED), intracranial injections, or directly implanting drug-containing wafers during surgery. [7, 8] Each of these methods have their own associated limitations such as reflux in the case of CED or a limited drug diffusion zone in the case of implanted wafers. These limitations prevent drugs from reaching invasive cancer cells in the brain parenchyma distant from the injection/implantation site. [9, 10] Alternatively, broad region disruption of the BBB is achievable via intra-arterial delivery of osmotic agents such as mannitol, however, therapeutic efficacy and feasibility of these methods are also limited due to a minimal half-life of BBB disruption (<10 minutes). Furthermore, mannitol requires the need for arterial catheterization, which limits the repeated treatments commonly used in cancer. [11]

Ultrasound (US) mediated BBB disruption is an emerging new technology that makes use of the physical interactions between ultrasonic waves and systemically administered microbubbles (MB) to transiently disrupt the BBB. [12] This technique has been used to enhance the delivery of a wide range of chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, carboplatin, and temozolomide across the BBB into the brain. [13–15] Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that US-mediated BBB disruption is well-tolerated in animal models and humans. [16–20]

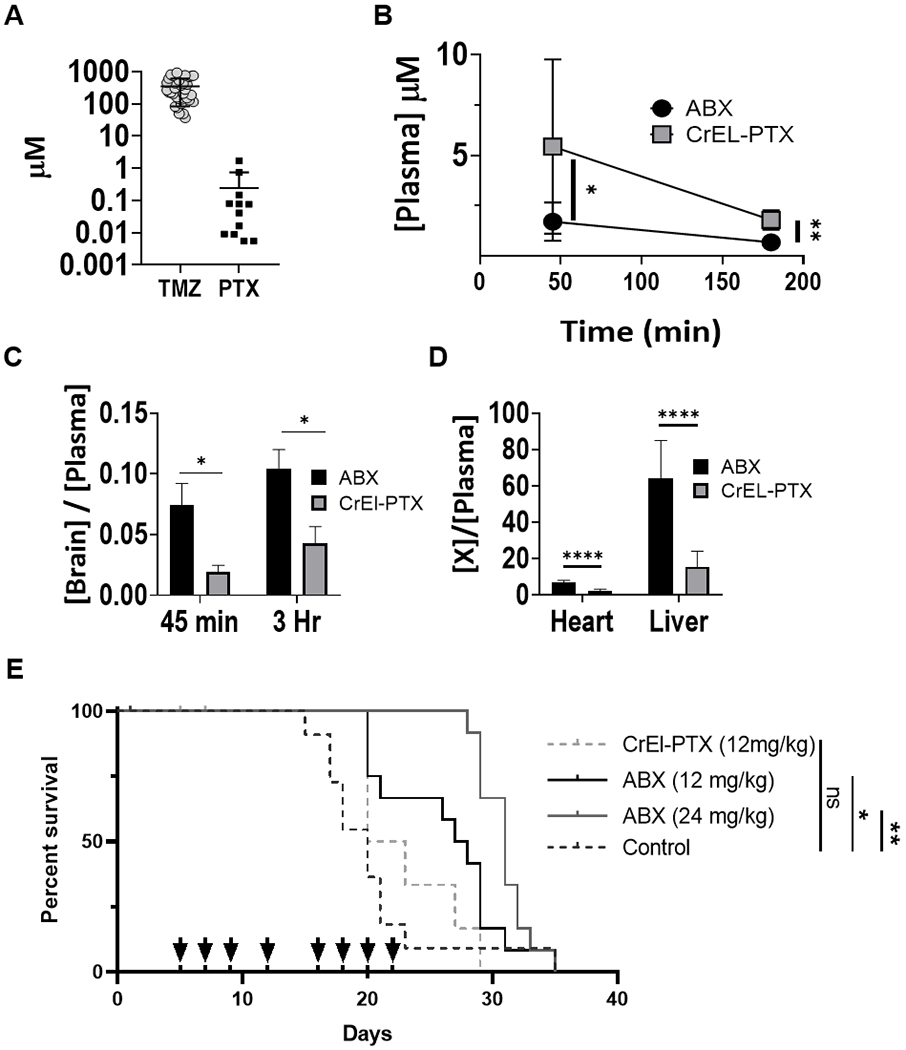

Paclitaxel (PTX), a microtubule stabilizing drug, was initially identified in preclinical models as a potent agent against GBM. According to the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database,[21] PTX exhibits robust anti-glioma effects in-vitro with an average IC50 concentration nearly 1400-fold lower than TMZ (Figure 1A). Yet, several clinical trials investigating PTX for the treatment of GBM demonstrated minimal response.[22–25] Studies later determined that while PTX concentration was detectable in tumor tissue, PTX was undetectable within the surrounding brain parenchyma, elucidating the BBB as a major limitation for PTX efficacy for infiltrative disease in gliomas. [26, 27]

Figure 1:

ABX displays greater bioavailability than CrEL-PTX and increased anti-glioma effect in-vivo. (A) Comparison of IC50 of glioma cell lines across two common chemotherapeutic drugs: TMZ, temozolomide (n=34), PTX (n=12). (B-D) Biodistribution of ABX and CrEL-PTX. (B) Plasma PTX concentration at 45 and 180 minutes (*p=.0285, **p=0.0056). (C) Ratio of brain to plasma PTX concentration at 45 minutes (ABX n=9, CrEL-PTX n=7, p=0.0193) and 180 minutes (ABX n=4, CrEL-PTX n=3, p=0.0349). (D) Ratio of heart or liver to plasma PTX concentration at 45 minutes (ABX n=9, CrEL-PTX n=7, p<0.0001). Data plotted, mean ±SD (E) In-vivo anti-glioma effect of ABX: MES83 cells were used to establish orthotropic xenografts and groups of 12 mice were randomized to treatment groups as indicated. Survival for each is plotted in Kaplan-Meier graphs and evaluated through log-rank test. Arrows represent treatment days (*p=0.0423, **p=0.0041).

There are currently two formulations of PTX that are approved for clinical use in humans: Taxol® (Generic) and Abraxane® (Celgene). PTX is a highly lipophilic molecule that is very poorly water-soluble. Taxol® is formulated by dissolving PTX in Cremophor EL (CrEL) for intravenous administration. Studies have demonstrated that CrEL, a 50:50 mix of polyethoxylated castor oil and dehydrated ethanol, is toxic to the peripheral nervous system which poses concerns about the safety of this formulation for use in the central nervous system (CNS). [28, 29]

Abraxane® is an albumin-bound PTX formulation (ABX) recently introduced as an alternative to Taxol®. ABX can be dissolved in water and does not contain CrEL as a vehicle. ABX was found to have a more favorable toxicity profile, in particular, a lower rate (10%) and shorter duration of peripheral neuropathy compared to Taxol (33%) in a large randomized trial of breast cancer patients. [30, 31]

We hypothesized that PTX is an effective agent against GBM if sufficient tumor and brain concentrations can be achieved. Given the concerns of neuro-toxicity for CrEL, and the limited brain penetration of conventional PTX formulations, we compared the safety, pharmacokinetic and efficacy profiles of CrEL dissolved PTX to that of ABX in the presence and absence of LIPU. Our pre-clinical investigations provide the foundation for clinical exploration of the albumin bound formulation of PTX in combination with US-based BBB disruption for GBM patients.

Materials and Methods:

Study Drugs

Commercially available clinical grade Abraxane® (Celgene) and Taxol® (Teva Pharmaceuticals) were purchased from the hospital pharmacy. Drugs were stored at room temperature according to the package insert and prepared the day of experiments.

Animal Studies

All animal studies were performed in accordance with Northwestern’s Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee. Six to twelve week old male and female athymic nude (nu/nu) mice purchased from Charles River Laboratories were used in these studies.

Sonication Procedure

The sonication procedure was performed using a pre-clinical LIPU device (SonoCloud® technology) manufactured by CarThera (Paris, France). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (K/X) cocktail (Ketamine 100mg/kg, Xylazine 10mg/kg, i.p.). MB (Lumason®, Bracco) were reconstituted according to manufacturer instructions and injected at a dose of 7.5 ml/kg through the retro-orbital route. Shortly after MB administration, mice were quickly (<10s) placed supine upon the US transducer holder and sonications began. A 1 MHz, 10-mm diameter flat US transducer was fixed in a holder filled with degassed water and sonications were performed transcranially (Figure S1A). Sonications were performed for 120 s using a 25,000 cycle burst at a 1 Hz pulse repetition frequency and an acoustic pressure of 0.3 MPa as measured in water. After sonications, mice were moved to a clean cage, placed upon a heating pad, and monitored until they recovered from anesthesia.

Fluorescein mapping of BBB disruption and bio distribution studies

Biodistribution studies were performed in healthy nude mice with intact BBB at two time points, 45 and 180 minutes after sonication. Following sonication, mice were injected i.v. with either ABX or CrEL-PTX (12 mg/kg). Forty-five minutes before euthanasia i.v. NaFl (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered at a dose of 20 mg/kg (Figure S1B). Dosing solutions were prepared by diluting a weighed amount of NaFl powder, ABX powder or measured volume of Taxol solution with 0.9% Saline solution to a final injection volume of 5 ml/kg. Mice were then euthanized with Euthasol (Virbac) solution (150 mg/kg, i.p.) and brains were carefully removed and imaged using Nikon AZ100 Epifluorescent microscope (4x, FITC filter cube, 2s exposure time). Highly fluorescent areas of the brain were separated from non-fluorescent regions using a clean No. 15 scalpel that was disposed of after every mouse. These samples were placed into separate cryo-vials (Corning) and flash frozen in liquid N2. Heart, liver and plasma samples were also collected and immediately flash frozen in liquid N2. Frozen tissue samples were stored in −80°C freezer for under 45 days before downstream PTX and NaFl concentration analysis.

LCMS determination of PTX concentration

PTX was determined in plasma and brain tissue using LC-MS/MS (6500 QTRAP AB Sciex, Framingham, MA equipped with a SIL-20AC XR HPLC, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD). For plasma analysis, a 50 μL aliquot of plasma was mixed with 200 μL of acetonitrile containing paclitaxel-d5 (internal standard, 2 ng/ml) in a 96-well deep well plate. After shaking for 5 minutes, the sample was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 mins at 4°C. An aliquot of 105 μL of supernatant was transferred to another 96-well deep well plate and diluted with 300 μL of ASTM type 1 water before instrumental analysis. Brain, heart and liver tissue specimens were finely minced with surgical scalpels and a 30 mg sample was treated with 1 mL of 50/50 acetonitrile/water (v/v), and homogenized in a 1600 MiniG (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ) tissue homogenizer for 10 min using a stainless steel ball. The resulting tissue homogenates extracts were then processed as above.

Chromatographic separation was achieved with a Kinetex C18, 50x2.1mm, 2.6 μm (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) column. The mobile phase was A: 0.1% formic acid in water (v/v) and B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v). After injection, initial conditions with A at 70% were held for 0.2 min, decreased to 30% in 2.8 min and held at 30% for 0.4 min before returning to initial conditions within 0.1 min and re-equilibration for 2.5 min before the next sample. The flow rate was 0.4 ml/min at 25 °C. Retention times for PTX and paclitaxel-d5 were both 2.55 min with a total run time of 6 min. A turbo ion spray interface was used as the ion source operating in positive mode. Acquisition was performed in multiple reaction monitoring mode (MRM) using m/z 854.5 → 286.0, 859.5 → 569.2 ion transitions at low resolution for paclitaxel, and paclitaxel-d5, respectively.

NaFl Concentration determination

NaFl was determined using a Glomax Multi Detection System (Promega, Madison, WI) with a Blue Fluorescence Optical Kit (excitation 490 nm, emission 515-580 nm). For plasma analysis, a 100 μL aliquot of plasma was mixed with 300 μL of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v) in a 2-mL micro-centrifuge tube. After shaking for 5 min, the sample was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. An aliquot of 20 μL of supernatant was transferred to a 2-ml micro-centrifuge tube and mixed with 380 μL of 10mM phosphate buffer solution (pH=8.5). After shaking for 3 min, an aliquot of 200 μL sample was transferred into a 96-well black microplate for fluorescence analysis. The sample was protected from light. Brain tissue specimens were homogenized as before and the extracts processed as described for plasma samples.

Toxicity studies

Toxicity of single and multiple courses of US delivered PTX was evaluated in nu/nu mice. For single course toxicity studies non tumor bearing healthy mice were used. Following treatment, bodyweight was monitored biweekly for three weeks before mice were euthanized and brains were collected for histological evaluation.

For multiple course toxicity studies, healthy non-tumor bearing and mice bearing intracranial xenografts were used. Mice receiving US alone, US-CrEl-PTX (12mg/kg), US-CrEL alone, US-ABX (12 mg/kg) and US-ABX (24 mg/kg) were treated eight times over a period of three weeks (Days 1, 3, 5, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18). CrEL was prepared in house by mixing dehydrated ethanol and Kolliphor EL (Sigma) in a 50:50 ratio. This solution was diluted to 5% in sterile 0.9% saline solution prior to retro orbital administration at 10 ml/kg. In addition, a separate cohort of mice treated with US-ABX (24 mg/kg) on a different dosing schedule (Days 1, 4, 8, 11, 15, 18, 22, 25) was also evaluated. Bodyweight and survival were monitored throughout treatment period and three weeks after last course of treatment. Mice who died during treatment had their brains collected for histological evaluation of CNS toxicity. In addition, non-tumor bearing mice were euthanized 21 days after last course of treatment to examine CNS toxicity that did not result in death.

Tissue was prepared for histology evaluation as follows. Following dissection from the cranium, mouse brains were placed into 4% paraformaldehyde solution. After 6-8 days of fixation, brains were transferred to PBS with 0.2% Sodium Azide (Alfa Aesar) for long term storage. Brains were dissected halfway between the dorsal and ventral surfaces in the transverse plane or at the midline of the brain in the sagittal plane before being dehydrated in a series of ethanol baths. Following dehydration, brains were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 um. Sections were stained with Harris Hematoxylin (Surgipath) and Eosin Y Solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed for histopathology by a neuropathologist blinded to treatment group. Representative images of brain sections were taken at 20X magnification (TissueGnostics) and then stitched together to create whole section images (TissueFaxs).

Intracranial Patient Derived Xenograft (PDX) Mouse Model

Single cell suspensions (MES83 from Ichiro Nakano, University of Alabama and GBM12 from C. David James, Northwestern University) generated from patient tumor samples were serial passaged as heterotrophic flank tumors and short term explant cultures as previously described prior to intracranial implantation. [32] For intracranial implantation, mice were anesthetized with K/X cocktail before a 1-cm incision was made in the midline of the mouse head to expose the skull underneath. A transcranial burr hole was created using sterile hand held drill (Harvard Apparatus) and mouse was mounted on a stereotaxic device (Harvard Apparatus). 2x104 MES83 cells or 5x104 GBM12 cells in 2.5 ul of sterile PBS were loaded into a 29G Hamilton Syringe and injected slowly over a period of three minutes into the left hemisphere of the mouse brain at 3 mm depth through the transcranial burr hole created 3 mm lateral and 2 mm caudal relative to midline and bregma sutures. Following injection, incision was closed using 9 mm stainless steel wound clips.

PDX Cell Viability Assay

MES83 and GBM12 cells were cultured as short term explant cultures in Dulbecco’s Minimum Essential Media (Corning) with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (GE health Sciences) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin solution (Corning) prior to being seeded at a density of 4000 cells per well in a 96 well plate. One day after seeding, cells were checked for attachment and confluence (60-70%). Media was removed from the wells and 100 μl fresh media with PTX dissolved in DMSO or ABX ranging in concentrations from 0.002 μM to 2 μM was placed into the wells. 72 hours later cell viability was determined by CellTiter Glo (Promega). PDX identity was confirmed through short tandem repeat (STR) analysis. (Supplementary Table 2).

Ultrasound Delivered Chemotherapy Treatment of PDX Mouse Model and Survival Analysis

For MES83 survival studies, five days after tumor implantation, mice (n=59) were distributed equally into five different treatment groups. Mice were anesthetized using K/X cocktail and injected i.v. through the retro-orbital route with either 0.9% Sterile Saline Solution, CrEL-PTX at 12mg/kg, ABX at 12 mg/kg, ABX at 24 mg/kg or ABX at 24 mg/kg immediately following sonication treatment. For GBM12 survival studies, five days after tumor implantation, mice (n=30) were distributed equally into three different treatment groups; control (0.9% sterile saline injection), ABX at 24 mg/kg or US delivered ABX at 24mg/kg.

Primary endpoint of the survival study was defined by the development of neurological symptoms due to tumor burden. Upon reaching endpoints, mice were sacrificed and their brains were harvested in preserved in 4% PFA. Presence of tumor was confirmed through gross examination of brain sections. Mice that died before such endpoints could be reached, or mice whose brains did not contain tumor were censored from survival analysis. Previous studies performed by our lab as well as others [14, 33] demonstrated that US alone (n=19) at the parameters used to disrupt the BBB is unable to extend survival, so this group was not included in the present studies.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Software (Prism). Two-tailed student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA was used to measure statistical differences between two groups or greater than two groups respectively. In-vitro dose response curves were generated by fitting experimental cell viability data to a sigmoidal curve using the inhibitor vs response—variable slope (four parameters) function. Statistical analysis of animal survival was performed using log-rank test. Pearson correlation coefficient was determined to measure strength of correlation.

Results:

Albumin-bound paclitaxel exhibits enhanced anti-glioma activity compared to cremophor-paclitaxel due to better brain penetration.

First, we compared the bio-distribution of systemically administered ABX to CrEL-PTX (Figure 1B–D). Plasma concentration of ABX was significantly lower than CrEL-PTX at both 45 and 180 minutes (p=0.0285 at 45 minutes, p=0.0056 at 180 minutes). Mice receiving ABX showed four-fold increased mean brain to plasma (B:P) ratio compared to mice that received CrEL-PTX at 45 minutes after administration (p=0.0193). At 180 minutes, ABX displayed two-fold greater B:P ratios than CrEL-PTX (p=0.0349). Other systemic organs, such as the heart and liver showed a similar phenomenon at 45 minutes (Figure 1D).

We then investigated whether the superior B:P ratio exhibited by ABX was associated with increased anti-glioma activity in-vivo using a orthotropic PDX model. PDX models are shown to better recapitulate genetic and morphologic characteristics typically found in primary human tumors compared to commercial cell lines. [34] We compared the therapeutic effect of CrEL-PTX and ABX at an equivalent dose (12 mg/kg) as well as at a higher dose of ABX (24 mg/kg) against MES83, a primary GBM intracranial PDX. (Figure 1E) [34, 35]. The doses we tested were chosen because they were well tolerated by mice and lead to plasma concentrations similar to those achieved in patients administered 260 mg/m2 of ABX, which is used for the q 3 week regimen for metastatic breast cancer.[31] Mice treated with CrEL-PTX (12mg/kg) did not show a significant increase in survival compared to untreated controls, however the same dose of ABX significantly increased median survival time by 137.5% (27.5 days) compared to untreated controls (20 days, p=0.0423). When the dose of ABX was doubled to 24 mg/kg, median survival increased by 155% (31 days, p=0.0041). CrEL-PTX was not tested at 24 mg/kg, as mice had difficulty tolerating the lower CrEL-ptx/Taxol® regimen.

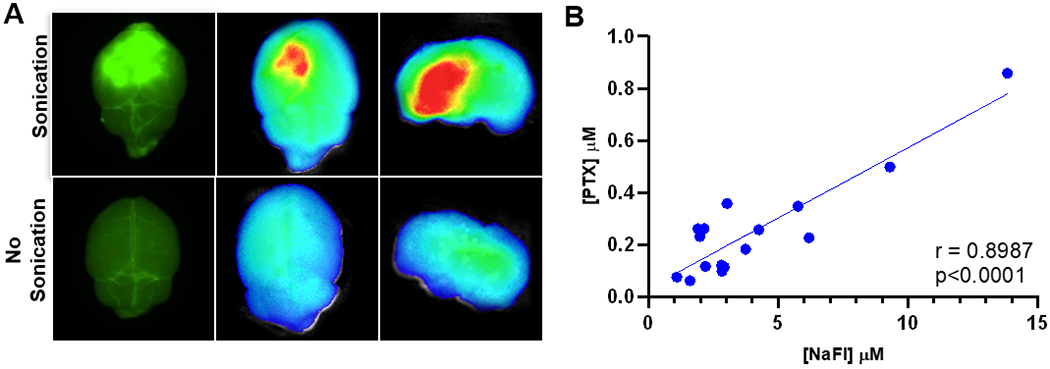

Fluorescein as a visual marker to map US-based BBB disruption and PTX accumulation in the brain

LIPU was used to disrupt the BBB and fluorescein was investigated as a potential tool to map BBB disruption by US through the following experiment. Mice were injected i.v. with sodium fluorescein (NaFl) and ABX immediately after sonication/MB injection. Forty-five minutes after NaFl injection, mice brains were harvested and imaged with a fluorescent microscope (Figure 2A). Fluorescent areas of the brain were then separated from non-fluorescent areas. Brain tissue samples were analyzed for PTX and fluorescein concentrations and compared to samples from non-sonicated control mice. We observed that regions of the brain targeted by the US device led to accumulation of fluorescein, and fluorescein concentrations were correlated with PTX concentration (r=0.8987, p<0.0001) (Figure 2B). These results confirmed US-based BBB disruption, and the use of fluorescein as a tool to map regions of the brain where PTX concentrations were elevated following this treatment.

Figure 2:

Sodium fluorescein is a visual marker for US BBB disruption. (A) Fluorescent imaging: mice injected i.v. NaFL were treated with US and compared to non-sonicated controls. Brains were harvested and imaged using Nikon AZ100 microscope at 4X magnification with FITC filter cube (left) and SII Lago In-vivo Imaging system (ex/em 465/530nm) (B) NaFl and PTX correlation: 16 brain samples from sonicated and non-sonicated mice were analyzed for NaFl and PTX concentration through LCMS. Correlation was determined by calculating Pearson coefficient (r=0.8987, p<0.0001).

Ultrasound further enhances the brain penetration and efficacy of albumin-bound paclitaxel in intracranial gliomas

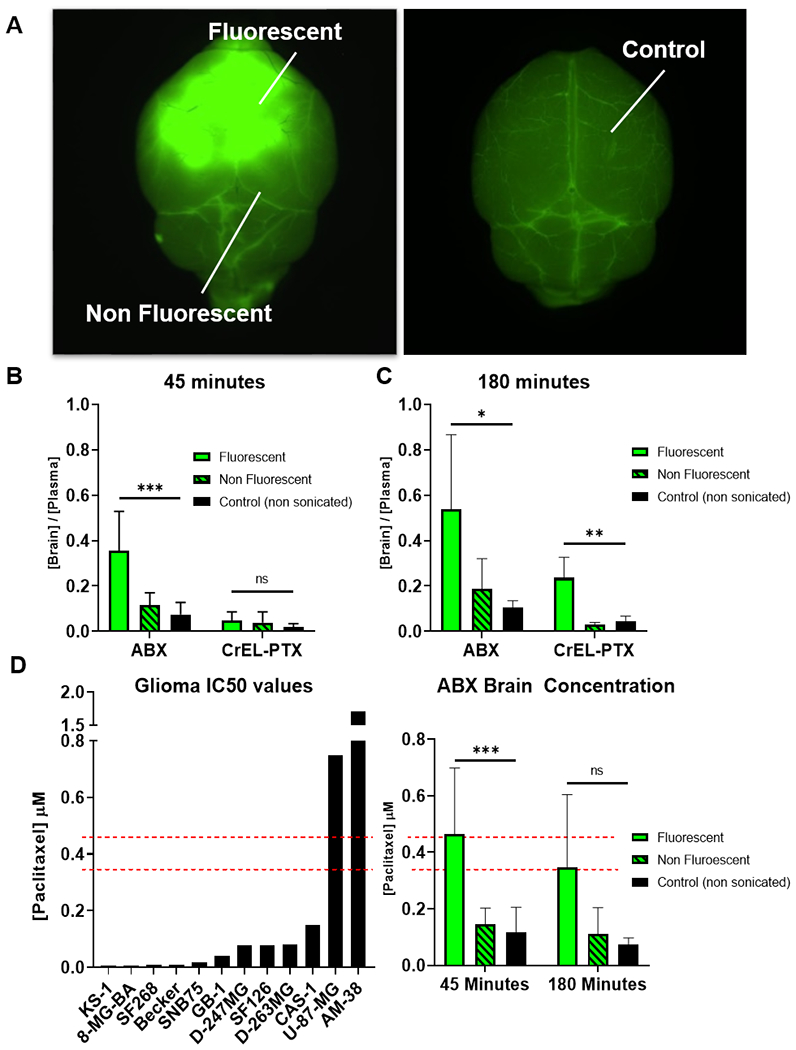

To determine the effect of US-based BBB disruption on PTX concentration within the brain, the fluorescein visualization method described above was used to quantify PTX levels in brain tissue from both sonicated and non-sonicated mice (Figure 3A).

Figure 3:

US increases ABX and CrEL-PTX brain penetration. (A) Representative image of how samples were dissected.(B-D) Following sonication and NaFl administration mice were injected with either ABX or CrEL-PTX at 12mg/kg. PTX concentration was determined in fluorescent, non fluorescent and non sonicated control samples through LCMS. Data plotted are mean±SD. Significance was determined one-way ANOVA test. (B) Brain/plasma PTX 45 minutes after sonication, ***p=0.0002, ns (C) Brain/plasma PTX 180 minutes after sonication. *p=0.0241, **p=0.0017 (D) Absolute concentration of PTX in US+ABX treated mice compared to human glioma cell line PTX IC50 concentration from Sanger /CCLE database. ***p=0.0006, ns.

Fluorescent brain tissue from mice receiving ABX showed a significant three to five-fold increase in PTX B:P ratios compared to non-fluorescent areas and non-sonicated controls at both 45 (p=0.0002) and 180 minutes (p=0.0241) (Figure 3B–C). In contrast, fluorescent brain tissue from mice receiving CrEL-PTX did not show a significant increase in PTX B:P at 45 minutes (p=0.219), but did show a significant increase at 180 minutes (p=0.0017) (Figure 3B–C). Furthermore, absolute concentrations of PTX in fluorescent brain tissue measured in mice receiving ABX surpassed IC50 values for ten out of twelve glioma cell lines listed in the Sanger/CCLE database (Figure 3D). [21]

Interestingly, the two different formulations of PTX displayed different pharmacokinetic profiles in the context of US-mediated drug delivery. The absolute brain PTX concentration achieved by US delivered ABX remained stable from 45 minutes to 180 minutes (p=0.4201). In contrast, brain PTX concentrations achieved through US delivered CrEL-PTX increased nearly twofold from 45 minutes to 180 minutes (p=0.01).

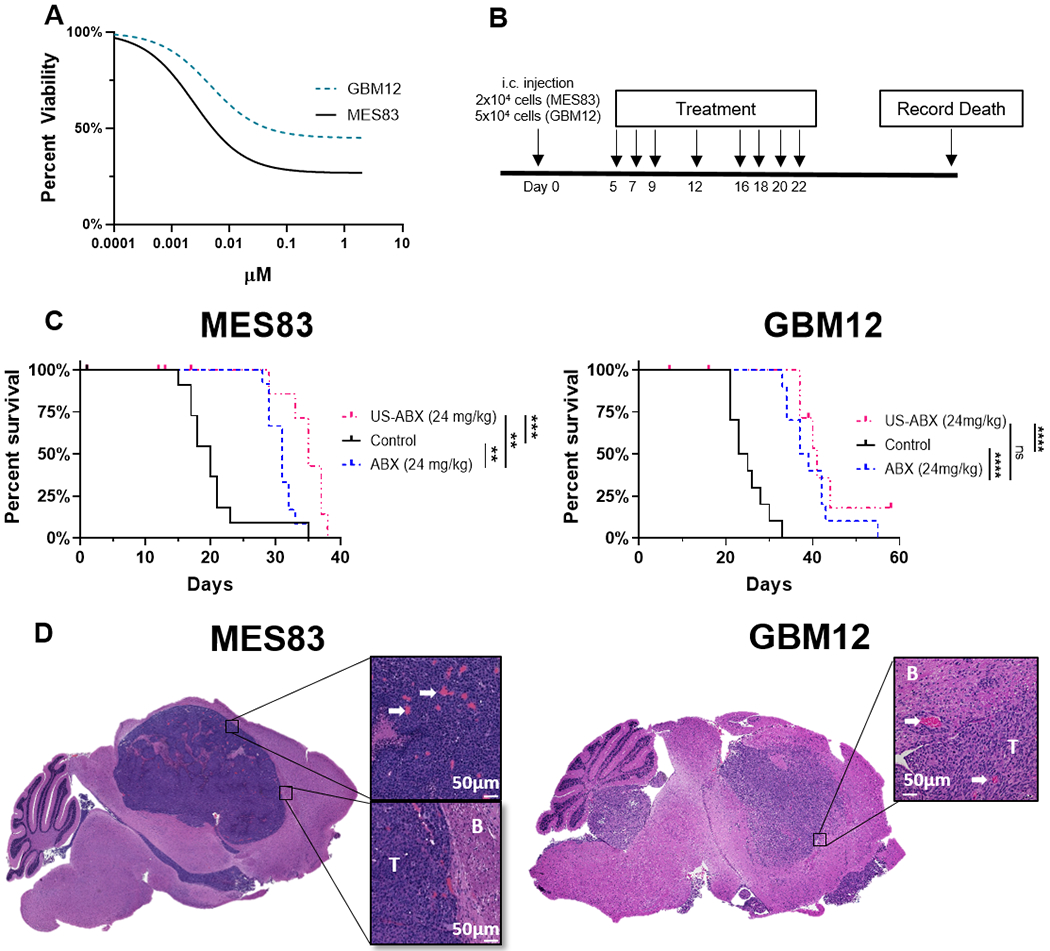

We next investigated whether the increase in drug concentrations achieved by US-based ABX delivery translated into superior efficacy against glioma models in-vivo. We tested our treatment in two different glioma PDX models, GBM12 and MES83, with differing therapeutic profiles in-vitro (Figure 4A). In MES83, the PDX line that exhibited more sensitivity to PTX, we observed US-based delivery of ABX (24 mg/kg) was able to nearly double median survival time (35 days) compared to untreated controls (20 days, p=0.0006). Furthermore, US-based delivery of ABX further extended median survival time of tumor bearing mice (35 days) beyond ABX alone (31 days, p=0.0036) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4:

Ultrasound delivered ABX differs in therapeutic profile between two patient-derived xenograft models (A) Cell viability: GBM12 and MES83 short term explant cultures were exposed to increasing doses of ABX, viability after 72 hours was determined by CellTiterGlo. Dose response curves represent three replicates. (B) Experimental timeline. (C) Five days after tumor implantation, mice were randomized to treatment groups as indicated and survival is plotted through Kaplan-Meier graphs. Survival differences were determined through log-rank analysis. Mice that did not die due to tumor burden were censored from this analysis. Censored subjects are denoted by tick mark on the day they were removed from the study. (MES83: **p=0.0041, **p=0.0036, ***p=0.0006) (GBM12: ****p<0.0001, ns (p=0.2590), ****p<0.0001) (D) H&E stain of tumor histology from untreated control mice. Left, MES83 xenograft. Right, GBM12 xenograft. White arrows show blood vessels. B, Brain tissue; T, Tumor mass. White scale bar, 50μm.

In mice bearing GBM12 xenografts, the PDX line that exhibited relative resistance to PTX, ABX (24mg/kg) was also successful in extending survival over control treated mice (38 vs 24 days, p<0.0001). Yet in this model, US-based delivery of ABX (24mg/kg) did not to significantly increase survival beyond ABX alone(41 vs 38 days, p=0.3747). However, H&E staining of untreated control mice revealed that both the MES83 and GBM12 xenografts are non-invasive and have extensive tumor vasculature which is known to have a defective BBB (Figure 4E).

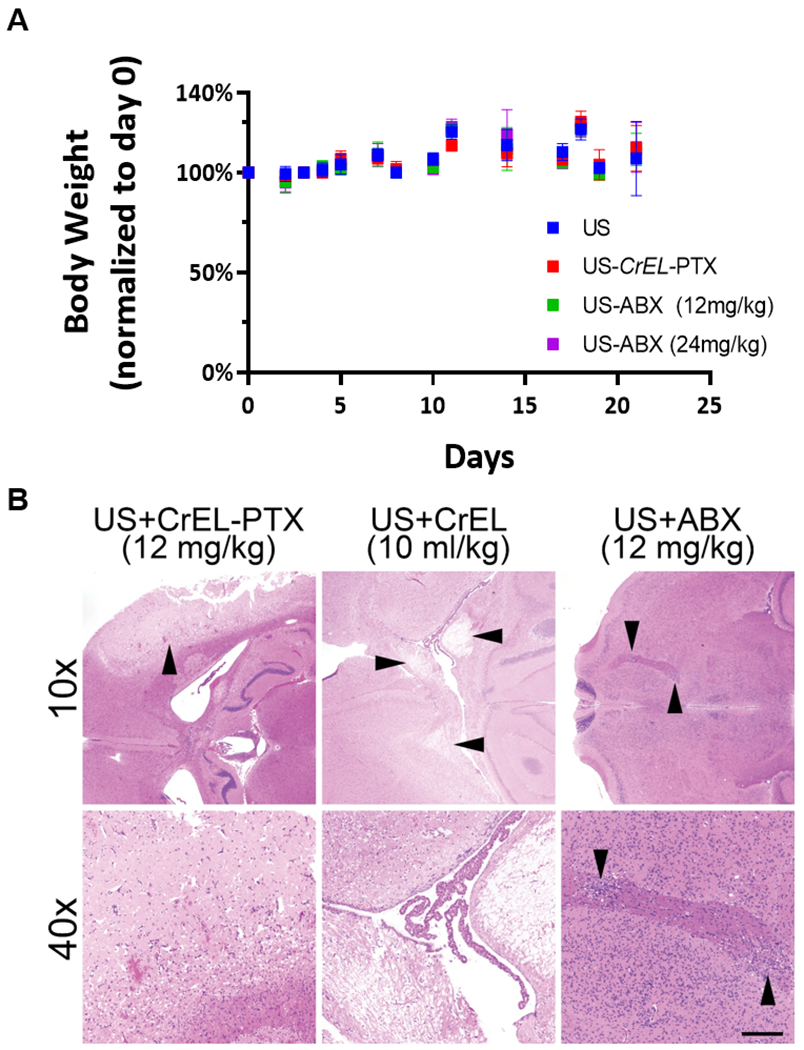

ABX exhibits less neurotoxicity compared to CrEL-PTX in the setting of ultrasound-based BBB disruption

In single course treatment toxicity tests, only mice receiving US delivered CrEL-PTX exhibited treatment related mortality. Two out of ten mice in the US+CrEL-PTX group died shortly after receiving i.v. CrEL-PTX injections; however, none of the surviving mice nor mice in other treatment conditions experienced any significant weight loss due to treatments (Figure 5A). Twenty-one days after the single treatment, mice were sacrificed and the brains underwent histological examination. The most common form of CNS pathology observed was vacuolation in white matter tracts of the corpus callosum. These lesions were found in 20% of mice treated with a single course of US therapy alone. No significant difference was found in CNS pathology between US therapy alone and US-based delivery of ABX at either dose tested except for one case of minor macrophage infiltration in a mouse treated with a single dose of US-ABX at 12 mg/kg. Conversely, signs of CNS pathology increased to 50% in mice that received a single dose of US-CrEL-PTX at 12 mg/kg (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 5:

Toxicity evaluation of ultrasound delivered paclitaxel therapy. (A) Bodyweight of mice following single course of treatment, ten mice were evaluated for each treatment condition. Data plotted are mean±SD. (B) Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained axial brain sections from mice following multiple courses of US-delivered paclitaxel. Damage was most severe in US-delivered CrEL-PTX (upper left, arrowhead, and lower left), although US-delivered CrEL alone also elicited marked white matter damage (upper central, arrowheads, and lower central). US-delivered ABX showed only small patches of damage to deep white matter tracts in some cases (upper and lower right, arrowheads). Scale bar=200 microns in lower panels and 800 microns in upper panels.

Toxicity due to multiple courses of treatment is presented in Table 1. Multiple courses of US and US delivered ABX at 12 mg/kg was generally well-tolerated and did not cause any additional signs of CNS pathology over those observed in mice receiving single course treatments. In contrast, multiple courses of US-CrEL-PTX at an equivalent dose (12mg/kg) produced a 58% mortality rate and caused significant necrosis and hemorrhage within the left hemisphere of the brain in 75% of the mice that died during treatment. Because CrEL has been implicated in the development of peripheral neuropathy observed in patients receiving Taxol therapy [28], we also evaluated the toxicity profile of CrEL when delivered through US. Three out of eight mice died while receiving multicourse US delivered CrEL. One of these mice displayed similar signs of CNS pathology observed in US-CrEL-PTX treated mice (Figure 5B). When the dose of ABX delivered through US was doubled to 24 mg/kg, 5 out of 25 mice experienced treatment related toxicity. Of these five mice, one exhibited diffuse axonal injury, one displayed signs of cytotoxic edema and one had focal points of white matter vacuolation. The remaining two mice displayed no signs of neurotoxicity. Interestingly, treatment related mortality was not observed when US-ABX (24mg/kg) treatment frequency was reduced to twice a week for four weeks. Due to the significant toxicity observed with US and CrEL-PTX at 12 mg/kg, US and CrEL-PTX at 24 mg/kg was not tested.

Table 1:

Toxicity evaluation from multiple courses of US delivered chemotherapy

| Treatment |

Non-tumor Bearing Mice |

i.c. glioma PDX modela |

Total Survival (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Signs of CNS Pathology | Mortality | Signs of CNS pathology | ||

| Ultrasound Only | 0/8 | 2/4 Small focal white matter vacuolation (WMV), Hemosiderin-laden macrophages (HLM) |

0/19 | 27/27 (100%) | |

| Ultrasound + Cremophor EL PTX (12mg/kg) | 4/7 | 3/4 severe necrosis, hemorrhage, Diffuse axonal injury (DAI), hippocampal damage |

3/7 (42%) | ||

| Ultrasound + Cremophor EL (5% in Saline) | 3/8 | 1/3 DAI 2/3 small focal WMV |

5/8 (62.5%) | ||

| Ultrasound + Abraxane (12mg/kg) | 1/6 | 3/4 Focal WMV |

0/20 | 25/26 (96%) | |

| Ultrasound + Abraxane (24mg/kg) | 0/5 | 1/3 HLM | 5/21 | 1/3 cytotoxic edema 1/3 DAI 1/3 focal WMV |

21/26 (81%) |

| Ultrasound + Abraxaneb (24mg/kg) | 0/10 | 10/10 (100%) | |||

In intracranial glioma PDX model mice, deaths were considered due to treatment if the day of death was considered significantly from control untreated tumor bearing mice (p<0.0005)

Mice received treatment twice a week (MTh) X 4 weeks instead of 8 courses of treatment over 3 weeks

Discussion

While the bulk of glioma tissue can often be safely resected, tumors tend to recur close to the initial presentation site, and thus, residual infiltrative tumor cells are considered to be the origin of the recurrence. [36] Many systemically administered cytotoxic or molecularly targeted therapies that are effective in the treatment of other solid tumors have proven of little benefit in glioma patients due to the presence of the protective BBB. [2] PTX displays one of the most potent anti-glioma effects in-vitro, but is unable to cross the BBB and reach infiltrative glioma cells at meaningful concentrations. [27] This work demonstrates that LIPU-based disruption of the BBB may be an effective technique to enhance penetration of PTX in glioma patients.

Shen et al. examined the therapeutic efficacy of a liposomal PTX formulation in an orthotropic GBM mouse model. Similar to our approach, they used US to open the BBB and demonstrated prolonged survival of mice suggesting meaningful antitumor activity. [33] However, this study did not compare or demonstrate whether this liposomal formulation exhibits better brain penetration than other PTX formulations. Moreover, there are currently no FDA approved liposomal-PTX formulations for use. In this study, we demonstrated the ability of US-based BBB disruption to increase PTX concentrations within the brain to therapeutic levels using two FDA approved PTX formulations that are indicated for use in a variety of solid tumors such as ovarian cancer, metastatic breast cancer, metastatic pancreatic cancer and advanced non-small cell lung cancer. [19, 37] Our results show that brain penetration, distribution, efficacy and neuro-toxicity of PTX is highly dependent on the vehicle solvent and chemical properties of each formulation, with ABX exhibiting improved penetration through the BBB compared to classical CrEL-PTX.

Using fluorescein, we showed that both PTX formulations exhibit increased brain penetration by US-mediated opening of the BBB. However, these formulations differed in their pharmacokinetic properties following US-mediated BBB opening, specifically, US delivered CrEL-PTX exhibited a delay in brain accumulation compared to US delivered ABX. 45 minutes after BBB disruption, CrEL-PTX did not show a significant increase in B:P ratios compared to non-sonicated controls. Only at 180 minutes did US delivered CrEL-PTX treated mice show increased B:P ratios compared to their non-sonicated controls. In contrast, US delivered ABX mice showed highly significant increases in PTX B:P ratios at both 45 and 180 minutes. This delay in brain accumulation can, in part, be explained by the finding that CrEL forms micelles within the plasma compartment of blood, trapping PTX in the circulatory system and thereby reducing its bioavailability. [38]

Our toxicity studies reveal ABX is better tolerated than CrEL-PTX in the context of US-based BBB disruption. At equivalent doses (12mg/kg), US delivered CrEL-PTX has significantly greater rates of neurotoxicity compared to US delivered ABX. While small patches of white matter vacuolation and macrophage infiltration was observed in mice receiving US delivered ABX (12 mg/kg), these lesions were indistinguishable from the lesions found in mice treated with US alone. In contrast, US delivered CrEL-PTX induced broad swathes of necrosis and hemorrhage. Previous studies in rats have shown that CrEL plasma levels similar to those reached in the context of therapeutic CrEL-PTX dosing induce a variety of neurotoxic effects such as: axonal swelling, vesicular degeneration and demyelination of dorsal ganglion neurons. [28] Our results show that administering CrEL alone following US-mediated BBB opening is enough to induce significant neurotoxicity. These findings provide further evidence that the neurotoxic effects associated with CrEL-PTX are to a great degree, related to CrEL, the vehicle solvent of this particular formulation, rather than PTX itself.

The neurotoxicity profile of the higher doses of US delivered ABX seems to be influenced by the frequency the treatment is given. In tumor bearing mice receiving multiple courses of US-ABX at 24 mg/kg, neurotoxicity induced death was observed in a small percentage (11.5%) of mice when the treatment was administered three times a week. Because signs of CNS pathology were observed in mice receiving multiple courses of US therapy alone, it is likely that a partial cause of the neurotoxicity observed in multicourse US-ABX mice is due to the frequency of the sonication procedure. This conclusion is further supported by the disappearance of treatment related mortality rates when the frequency of US-ABX treatment is reduced to twice a week. Such side effects might be more likely observed in small animals, as the safety of US-mediated BBB opening in primate models and human subjects is well established, even in regimens in which sonication is performed every 3 weeks in GBM patients. [17–20]

Another interesting finding was the observation that ABX in the absence of US was able to provide a significant survival benefit despite having a similar cytotoxicity profile in-vitro to free PTX (Figure S2). Previous groups have hypothesized that ABX is actively transported into the tumor through endothelial glycoproteins and through the SPARC mediated albumin binding pathway. [30, 39] It is possible that the active transportation of ABX through these pathways allows for increased drug accumulation within the tumor.

We also showed that the increased PTX levels within the brain parenchyma achieved by US-delivery of ABX provides an increase in survival compared to ABX administration alone in one of two glioma PDX models. The observed difference in US therapeutic efficacy may be explained by the fact that GBM12 displays decreased sensitivity to ABX, with cell viability plateauing around 50% starting at 0.03μM of ABX exposure. H&E staining of GBM 12 and MES83 xenografts in untreated control mice reveal that these tumors display extensive tumor vasculature, which is known to have defective BBB, and relatively well demarcated tumor-brain borders. It is likely that ABX is able to reach therapeutic concentrations within this tumor regardless of US-mediated delivery, masking the therapeutic benefit US may grant for infiltrative disease with intact BBB seen in patients, which cannot be easily modeled using PDX in mice.

Early attempts to disrupt the BBB though US were thwarted by the inability for US waves to bypass the human skull. Two methods have been developed to overcome this obstacle. The first, transcranial focused ultrasound (FUS), uses a large external US transducer that is either single or multi-element to generate a focused ultrasound beam to target a specific focal region of the brain for BBB disruption. Guidance of the treatment is then performed using either neuronavigation or MR-guidance, with US feedback to control the sonication output parameters.[18] The second method, is an US device directly implanted into a cranial window on the patient’s skull. While both methods of US-BBB disruption are well tolerated, they have their own associated advantages and limitations. [18, 20] Transcranial FUS allows for more precise targeting of BBB disruption, however, the relatively small region of BBB disruption may not be sufficient to cover the areas where residual tumor cells may be residing following tumor resection. On the other hand, the most recent iteration of the implantable US device developed by Carthera, Sonocloud-9, features nine US transducer heads that are designed to sonicate the tumor and surrounding infiltrative region. [40]

As US-mediated BBB disruption for drug delivery moves from pre-clinical to clinical studies, the ability to quantify the concentration of the therapeutic agent delivered into the brain parenchyma via US-mediated BBB opening may be of importance. [40] Currently, BBB disruption by US is validated by the use of Evan’s Blue injection in animal models or by MRI gadolinium contrast-enhancement in patients. [19, 41] One drawback to MRI visualization of BBB opening is this method does not allow for real-time tissue sampling of regions of US BBB disruption. On an initial pharmacokinetic human study of the effect of US on drug concentrations, tissue for analysis was collected one day after MRI confirmation of US-mediated BBB opening. [18] This delay and inaccuracy in sampling of tissue subject to BBB disruption can negatively impact the measurement of therapeutic agent concentration achieved by US delivery in humans. Because NaFl has been established as an intraoperative tool to guide glioma resection,[42] we sought to investigate its ability as a visual marker for US based BBB. Our study establishes the ability of NaFl to map BBB disruption following a 45 minute incubation period, which is feasible in the operating room. Thus, we believe that in future clinical trials, NaFl can be repurposed to guide sampling of peri-tumoral brain tissue subject to US-based BBB disruption in real-time. This would allow for intraoperative pharmacokinetic studies to directly investigate the effect of US-based BBB disruption on the concentration of chemotherapeutics in the peri-tumoral brain .

Other interesting formulations of paclitaxel designed to bypass the BBB are in early pre-clinical and clinical development. In particular, GRN-1005, a novel PTX-peptide conjugate has been explored in the context of gliomas and brain metastases.[43] GRN-1005 relies on low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1)-mediated transcytosis to deliver PTX across the BBB. A recent Phase I clinical trial investigating GRN-1005 in recurrent glioma patients reported PTX levels in excised tumor tissue generally exceeded plasma levels in patients treated with GRN-1005. Furthermore, patients exhibited no signs of CNS toxicity even when GRN-1005 was administered at 650 mg/m2. [44] A phase II study aimed at evaluating efficacy of this drug in the treatment of GBM was recently completed in 2017, the results of which are eagerly awaited.

In conclusion, novel methods for the treatment of GBM are urgently needed. PTX displays high cytotoxicity against glioma, yet this efficacy has not been exploited due to the protective BBB. In this study, we have demonstrated the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of repeated US delivery of ABX. US is a well-tolerated and effective way to increase drug delivery to the human brain and ABX is a well characterized FDA approved formulation of PTX. In this context, systemic administration of ABX with concomitant US-based BBB disruption with LIPU is a novel treatment of high therapeutic value that is well positioned to be explored in clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance:

Paclitaxel is approximately 1400-fold more potent than temozolomide, the current standard chemotherapy for glioma, yet it is not used in the clinic due to its inadequate penetration across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Here, we demonstrate the ability of low intensity pulsed ultrasound-based BBB opening to increase paclitaxel concentrations in the brain after systemic administration of paclitaxel. Two different FDA approved formulations of paclitaxel were compared. The albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel was better tolerated and had increased brain penetration compared to the cremophor-based formulation. Multiple sessions of ultrasound delivered albumin-bound paclitaxel increased survival in an orthotropic glioma model compared to non-sonicated controls while ultrasound delivered cremophor-paclitaxel induced central nervous system toxicity. Our preclinical experiments suggest that increased paclitaxel drug delivery by disrupting the BBB is feasible, and an effective anti-glioma treatment. Albumin-bound paclitaxel is the preferred formulation for further investigation in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments:

This work was funded by 5DP5OD021356-04 (AS), P50CA221747 SPORE for Translational Approaches to Brain Cancer (AS & RS), and Developmental funds from The Robert H Lurie NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30CA060553 (AS). We are grateful for the generous philanthropic support from Dan and Sharon Moceri. Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. Histology services were provided by the Northwestern University Research Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory which is supported by NCI P30-CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. The authors would like to thank CarThera for providing the equipment and guidance necessary to perform the US-mediated blood brain barrier opening procedure.

Financial Support: P50CA221747 SPORE for Translational Approaches to Brain Cancer, 5DP5OD021356-04, P30CA060553 NCI Cancer Center Support Grant, Philanthropic Support from Dan and Sharon Moceri

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: D.Z., R.S. and A.S. have submitted a patent application on the proposed treatment through Northwestern University. M.C., C.D. and A.C. have ownership in CarThera. A.C. is a paid consultant of CarThera. M.C. and C.D. are employees of CarThera

References

- 1.Stupp R, et al. , Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2017. 318(23): p. 2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitz MW, et al. , Tissue concentration of systemically administered antineoplastic agents in human brain tumors. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 2011. 104(3): p. 629–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardridge WM, The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx, 2005. 2(1): p. 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long DM, Capillary ultrastructure and the blood-brain barrier in human malignant brain tumors. J Neurosurg, 1970. 32(2): p. 127–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane JR, The Role of Brain Vasculature in Glioblastoma. Molecular Neurobiology, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Tellingen O, et al. , Overcoming the blood-brain tumor barrier for effective glioblastoma treatment. Drug Resist Updat, 2015. 19: p. 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobo RH, et al. , Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994. 91(6): p. 2076–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allhenn D, Boushehri MA, and Lamprecht A, Drug delivery strategies for the treatment of malignant gliomas. Int J Pharm, 2012. 436(1-2): p. 299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahangiri A, et al. , Convection-enhanced delivery in glioblastoma: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. J Neurosurg, 2017. 126(1): p. 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunwar S, et al. , Phase III randomized trial of CED of IL13-PE38QQR vs Gliadel wafers for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol, 2010. 12(8): p. 871–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zunkeler B, et al. , Quantification and pharmacokinetics of blood-brain barrier disruption in humans. J Neurosurg, 1996. 85(6): p. 1056–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi JJ, et al. , Noninvasive, transcranial and localized opening of the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound in mice. Ultrasound Med Biol, 2007. 33(1): p. 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aryal M, et al. , Enhancement in blood-tumor barrier permeability and delivery of liposomal doxorubicin using focused ultrasound and microbubbles: evaluation during tumor progression in a rat glioma model. Phys Med Biol, 2015. 60(6): p. 2511–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drean A, et al. , Temporary blood-brain barrier disruption by low intensity pulsed ultrasound increases carboplatin delivery and efficacy in preclinical models of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beccaria K, et al. , Ultrasound-induced opening of the blood-brain barrier to enhance temozolomide and irinotecan delivery: an experimental study in rabbits. J Neurosurg, 2016. 124(6): p. 1602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs ZI, et al. , MRI and histological evaluation of pulsed focused ultrasound and microbubbles treatment effects in the brain. Theranostics, 2018. 8(17): p. 4837–4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu SY, et al. , Efficient Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Primates with Neuronavigation-Guided Ultrasound and Real-Time Acoustic Mapping. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 7978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mainprize T, et al. , Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Primary Brain Tumors with Non-invasive MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound: A Clinical Safety and Feasibility Study. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carpentier A, et al. , Clinical trial of blood-brain barrier disruption by pulsed ultrasound. Sci Transl Med, 2016. 8(343): p. 343re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Idbaih A, et al. , Safety and Feasibility of Repeated and Transient Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption by Pulsed Ultrasound in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 2019: p. clincanres.3643.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barretina J, et al. , The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature, 2012. 483(7391): p. 603–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamberlain MC and Kormanik P, Salvage chemotherapy with paclitaxel for recurrent primary brain tumors. J Clin Oncol, 1995. 13(8): p. 2066–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prados MD, et al. , Phase II study of paclitaxel in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol, 1996. 14(8): p. 2316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fetell MR, et al. , Preirradiation paclitaxel in glioblastoma multiforme: efficacy, pharmacology, and drug interactions. New Approaches to Brain Tumor Therapy Central Nervous System Consortium. J Clin Oncol, 1997. 15(9): p. 3121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang SM, et al. , Phase I study of paclitaxel in patients with recurrent malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium report. J Clin Oncol, 1998. 16(6): p. 2188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heimans JJ, et al. , Paclitaxel (Taxol) concentrations in brain tumor tissue. Ann Oncol, 1994. 5(10): p. 951–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heimans JJ, et al. , Does paclitaxel penetrate into brain tumor tissue? J Natl Cancer Inst, 1995. 87(23): p. 1804–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Authier N, et al. , Assessment of neurotoxicity following repeated cremophor / ethanol injections in rats. Neurotoxicity Research, 2001. 3(3): p. 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Windebank AJ, Blexrud MD, and de Groen PC, Potential neurotoxicity of the solvent vehicle for cyclosporine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 1994. 268(2): p. 1051–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gradishar WJ, Albumin-bound paclitaxel: a next-generation taxane. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 2006. 7(8): p. 1041–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gradishar WJ, et al. , Phase III Trial of Nanoparticle Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel Compared With Polyethylated Castor Oil–Based Paclitaxel in Women With Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2005. 23(31): p. 7794–7803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson BL, et al. , Establishment, maintenance and in vitro and in vivo applications of primary human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) xenograft models for translational biology studies and drug discovery. Curr Protoc Pharmacol, 2011. Chapter 14: p. Unit 14 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen Y, et al. , Enhanced delivery of paclitaxel liposomes using focused ultrasound with microbubbles for treating nude mice bearing intracranial glioblastoma xenografts. Int J Nanomedicine, 2017. 12: p. 5613–5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodgson JG, et al. , Comparative analyses of gene copy number and mRNA expression in glioblastoma multiforme tumors and xenografts. Neuro Oncol, 2009. 11(5): p. 477–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao P, et al. , Mesenchymal glioma stem cells are maintained by activated glycolytic metabolism involving aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013. 110(21): p. 8644–8649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg FH and Pruitt A, Assumptions in the radiotherapy of glioblastoma. Neurology, 1980. 30(9): p. 907–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skog J, et al. , Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol, 2008. 10(12): p. 1470–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sparreboom A, et al. , Cremophor EL-mediated Alteration of Paclitaxel Distribution in Human Blood. Clinical Pharmacokinetic Implications, 1999. 59(7): p. 1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trieu V, et al. , SPARC expression in breast tumors may correlate to increased tumor distribution of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (ABI-007) vs taxol. Cancer Research, 2005. 65(9 Supplement): p. 1314–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonabend AM and Stupp R, Overcoming the blood-brain barrier with an implantable ultrasound device. Clin Cancer Res, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang FY and Lee PY, Efficiency of drug delivery enhanced by acoustic pressure during blood-brain barrier disruption induced by focused ultrasound. Int J Nanomedicine, 2012. 7: p. 2573–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinoda J, et al. , Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme by using high-dose fluorescein sodium. Technical note. J Neurosurg, 2003. 99(3): p. 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Regina A, et al. , Antitumour activity of ANG1005, a conjugate between paclitaxel and the new brain delivery vector Angiopep-2. Br J Pharmacol, 2008. 155(2): p. 185–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drappatz J, et al. , Phase I study of GRN1005 in recurrent malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res, 2013. 19(6): p. 1567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.