Abstract

Background

Ensuring nutritional status of women is important because the malignant effects of malnutrition are procreated to the next generation through women and their off-springs. Malnutrition causes 3.5 million death of women and children each year and almost 11% of the disease burden in the world. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess nutritional status and factors associated with underweight among lactating women in Womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016.

Methods

A Community-based cross-sectional study was carried out in Womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia. A total of 668 lactating women who have 6–24 months of child were included in the study. Study participants were selected using a multistage sampling technique. Data were collected using interview-administered questionnaire. Body mass index (BMI) was used to measure the nutritional status of lactating women. Women’s body weight and height were measured using the standard anthropometric measurement procedures. Data were entered using EpiData software and analysis was done using SPSS software. Descriptive, bivariate and multivariable logistics regression analysis were used to present the findings. Variables with a p-value less than 0.05 on multiple variable logistic regression were taken as significant variables.

Results

Lactating women with normal nutritional status (BMI = 18.5–24.99 kg/m2) were 498 (74.5%), and underweight women (BMI < 88.5 kg/m2) were 170(25.4%). Respondents with less than five family size (AOR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.81, p-value = 0.007), women whose age of first pregnancy was less than 18 years old (AOR: 3.72, 95% CI: 2.33, 6.49 at p-value = 0.0001), home delivery for the recent child birth (AOR: 2.36, 95% CI: 1.50, 3.72 at p-value = 0.0001), and the absence of nutritional education programs in the community (AOR: 5.5, 95% CI: 1.8, 16.79 at p-value = 0.003) were the significant variables with underweight of lactating women.

Conclusions

Nutritional status of lactating women in the study area was poor. One fourth of lactating women was underweight. Factors associated with underweight of lactating women include; respondents with less than five family size, women whose age of first pregnancy was less than 18 years old, home delivery for the recent childbirth, and the absence of nutritional education programs in the community. Early childbearing and short birth intervals between births should be discouraged. Programs which encourage institutional delivery and community-based nutritional education are important to improve women nutritional status.

Keywords: Nutritional status, Underweight, Lactating women, WOMBERMA, Ethiopia

Background

Nutritional status is considered as one of the major indicators of the overall wellbeing of a population [1, 2]. Malnutrition causes more than 3.5 deaths among women and children every year and accounts 11% of disability adjusted life years globally [3]. The nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women is very important since it also affects the health of their children [1, 2]. Children born from women who became malnourished during pregnancy and lactation are at higher risk of perinatal health problems. So, improving the nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women is crucial for the health of children [4].

Malnutrition is one of the common health problem affecting millions of peoples in developing countries. This contributes to poor health and nutritional status among the population which leads to chronic energy deficiency [5]. The demand for nutrition is higher for lactating women, and it affects the milk composition and production among lactating women, and the health of infants and adulthood life [6, 7]. A study has shown that nutrients like; vitamin A, D, B1, B2, B6, and B12, fatty acids and iodine are important for the optimal level of milk production [6]. Prolonged inadequate caloric intake can also affect the quality and quantity of breast milk production [8]. So, malnutrition in lactating women can induce a metabolic disturbance in the early life of infants, which can result in physiological alteration [7, 9].

Poor nutritional status of lactating women is considered as one of the greatest threat to the world public health and is a serious developmental threat of a country [10, 11]. In Ethiopia, studies have shown a higher prevalence of malnutrition among lactating women [11]. A study conducted in Northwest Ethiopia showed nutritional inadequacy among urban residents [12]. The 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS) report showed that 27% of women aged 15–49 years were undernourished. Additionally, the report showed that 9% and 6% of reproductive age women were moderately and severely malnourished respectively [4].

There are a limited number of studies conducted to assess the nutritional status of lactating women in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the nutritional status and factors associated with underweight among lactating women in Womberma woreda, North West Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design, area and period

A community-based cross-sectional study was carried out in Womberma woreda, Amhara region, North West Ethiopia. The woreda is located at 427 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia and 172 km from Bahir Dar, the capital city of Amhara region. The woreda has a total of 20 districts; 19 rural and one urban. According to the 2015 population statistics of woreda health office, there were 124,177 populations in the woreda. From this, 4822 were lactating women who have 6–24 months of child [13].

Eligibility criteria

The source population for this study was all lactating women who had 6–24 months of child. Mothers who lived in the area for six or more months were included in the study. Lactating mothers who were seriously ill and physically unable to fit for anthropometric measurement were excluded from the study. Additionally, women who were or who suspect of pregnancy like; those who did not have menstruation after 45 days of childbearing, and women who had doubt for pregnancy were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size for the study was calculated using single population proportion formula. It was calculated by considering 27% magnitude of underweight from 2011 EDHS report [4], expecting a maximum disparity of 5% between the study, 95% confidence interval (CI), 10% non-response rate and a design effect of two. The final sample size calculated was 668 lactating women.

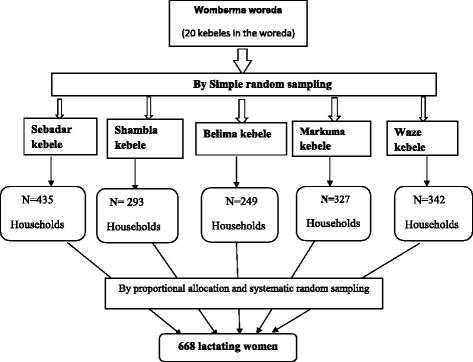

The study participants were selected using a multistage sampling technique. From the 20 districts in the woreda, five districts were selected randomly by using a lottery method. All households with lactating women were identified from health extension worker’s family folder and proportional allocation was done. Systematic sampling technique was used to select households, and study participants were selected using simple random sampling technique. In households where there are more than one lactating women, lottery method was used to select participants. Three visits to participants were made for absences in the first visit (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure

Data collection techniques and study variables

The data collection tool was developed after reviewing related works of literature. The data collection tool included questions related to socio-demographic variables, obstetric history, nutrition, health-related variables and anthropometric measurements. An adult weighing scale was used for weight measurement, and portable height meter with a moveable head piece was used for the height measurement of the study participants. Data was collected by 12 registered nurses and two supervisors were involved in the data collection process. Training on the data collection procedures and ethical issues were given for the data collectors and supervisors. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2) for each participant. Instruments were checked against a standard weight for its accuracy daily. Calibration of the indicator against zero reading was checked following weighting every lactating woman. The dependent variable of the study was the nutritional status of lactating women (normal vs underweight). The independent variables include; sociodemographic characteristics, obstetric history, nutrition-related variable, and health-related variables.

Data quality, processing, and analysis

Data quality was assured through careful design of the questionnaire and data collection procedure. A pre-test was done prior to data collection in the area other than the selected woredas. Data was checked for completeness and consistency. Data was entered using EpiData version 3.1 software and exported to SPSS version 20 for further analysis. Descriptive statistics, binary and multivariable logistic regression analysis were used to present the findings. Variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in the binary logistic regression analysis were entered into a multivariable logistic regression analysis to control for potential confounders. Significant association of variables was declared using adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval and variables with a p-value less than 0.05 were taken as statistically significant.

Operational definitions

Body mass index: a measurement technique which is calculated as weight in kilogram divided by height in meter squared.

Under-weight: Women whose body weight was too low, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2.

Over-weight: Excessive, unbalanced intake of energy or nutritional substances, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2.

Normal weight: Women who have BMI of 18.5–24.99 kg/m2.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 668 lactating women were involved with a response rate of 100%. More than half, 382(57.2%) of the respondents were in the age group of 25–34 years and 179(26.8%) were aged greater than 34 years. The mean age and standard deviation (SD) of respondents were 30.4 and 5.4 years respectively. All the respondents were Orthodox Christians by religion and 489 (73.2%) of respondents were unable to read and write. Nearly all, 664(99.4%) participants were farmers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents in womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 15-24 | 107 | 16 |

| 25-34 | 382 | 57.2 | |

| >34 | 179 | 26.8 | |

| Educational status of the respondent | Cannot read and write | 489 | 73.2 |

| Can read and write | 66 | 9.9 | |

| Primary (grade 1 to 8) | 95 | 14.2 | |

| Secondary(grade 9 to 10) | 18 | 2.7 | |

| Marital status | Married | 618 | 92.5 |

| Widowed | 10 | 1.5 | |

| Divorced | 30 | 4.5 | |

| Separated | 10 | 1.5 | |

| Educational status of husband | Cannot read and write | 277 | 41.5 |

| Can read and write | 175 | 26.2 | |

| Primary (grade 1 to 8) | 129 | 19.3 | |

| Secondary(grade 9 to 10) | 35 | 5.2 | |

| College level and above | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Amhara | 646 | 96.7 |

| Agew | 16 | 2.4 | |

| Oromo | 6 | 0.9 | |

| Average monthly income (in Ethiopian birr) | <500 | 356 | 53.3 |

| 500-999 | 148 | 22.2 | |

| 1000-1999 | 39 | 5.8 | |

| >2000 | 125 | 18.7 | |

| Family size | ≤5 | 392 | 58.7 |

| >5 | 276 | 41.3 | |

Obstetric history of respondents

The mean age of respondents at first marriage was 15 years (SD ± 2.7 years), with a minimum and maximum of 7 and 26 years respectively. The majority, 92.7% of respondents were married before their eighteenth birthday. The mean and SD age of women at first pregnancy was 19.15 ± 2.2 years respectively. The minimum age of pregnancy was 14 years, and the maximum was 28 years. The mean number of children a woman has was 3.7. Only 405(60.6%) of lactating women were using any type of family planning during the time of data collection. Regarding maternal health service utilization, 597(89.4%), 402(60.2%), 163(24.4%) had antenatal visits, institutional delivery, and postnatal visit for their most recent pregnancy and childbirth respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric history of the respondents in womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first marriage (in years) | <18 | 619 | 92.7% |

| ≥18 | 49 | 7.3% | |

| Age at first pregnancy (in years) | <19 | 452 | 67.7% |

| ≥19 | 216 | 32.3 | |

| Number of pregnancy | ≤5 | 544 | 81.4% |

| >5 | 124 | 18.6% | |

| Number of live birth | ≤4 | 513 | 76.8% |

| >4 | 155 | 23.2% | |

| Current family planning utilization status | Yes | 405 | 60.6% |

| No | 263 | 39.4% | |

| Attending ANC for the current child. | Yes | 597 | 89.4% |

| No | 71 | 10.6% | |

| Attending PNC for the current child. | Yes | 163 | 24.4% |

| No | 505 | 75.6% | |

| Place of delivery for last pregnancy | Health center | 347 | 51.9% |

| Home | 266 | 39.8% | |

| Health post | 16 | 2.4% | |

| hospital | 39 | 5.8% | |

| Age of current breastfeeding child | ≤12 months | 332 | 49.7% |

| >12 months | 336 | 50.3% | |

Health and nutritional status of respondents

Respondents were asked if they had any history of sickness in the last 1 month prior to the data collection period. Accordingly, 128(19.2%) reported that they were sick in the last 1 month prior to the data collection. From this, 9(1.3%) of participants had a history of admission related with malnutrition. The average distance of the nearest health facility from respondent’s house was 4.6 km.

The nutritional status of lactating women was measured using BMI. The mean weight (±SD), height (±SD) and BMI (±SD) of respondents were 49.9 ± 5.7 kg, 1.57 ± 0.05 m and 20 ± 1.98 kg/m2 respectively. Additionally, 487(72.9%) had a normal nutritional status, and 171(25.6%) were underweight. The magnitude of overweight women was 10(1.5%). Less than half, 259(38.8%) of lactating women received nutritional education in their community, and the main source of such information were health extension workers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nutritional and health-related factors for the study participants in womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sickness in the last month. | Yes | 128 | 19.2 |

| No | 540 | 80.8 | |

| Admission due to nutrition-related problem in the last one month | Yes | 9 | 1.3 |

| No | 659 | 98.7 | |

| Distance of respondent’s household from the nearby health facility | ≤5km | 487 | 72.9 |

| >5km | 181 | 27.1 | |

| Nutritional status (BMI) | Normal nutritional status (18.5-24.99 kg/m2) | 487 | 72.9 |

| Underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2) | 170 | 25.4 | |

| Overweight (> 25 kg/m2) | 11 | 1.6 | |

Factors associated with underweight among lactating women

Variables which were found to be associated with underweight of lactating women on bivariate analysis include; large family size, younger age of the woman at first pregnancy, the absence of male involvement during antenatal visits, place of delivery, and absence of nutritional education programs in the community.

On multivariable logistic regression analysis, variables like; respondents with less than five family size (AOR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.81 at p-value = 0.007), women whose age of first pregnancy was less than 18 years old (AOR: 3.72, 95% CI: 2.33, 6.49 at p-value = 0.0001), home delivery for the recent childbirth (AOR: 2.36, 95% CI: 1.50, 3.72 at p-value = 0.0001), and the absence of nutritional education programs in the community (AOR: 5.5, 95% CI: 1.8, 16.79 at p-value = 0.003) were significantly associated with underweight of lactating women (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showing factors associated with underweight of lactating women in womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016

| Variables | Nutritional status of lactating women | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (BMI 18.5-25 Kg/m2) n(%) | Underweight (BMI <18.5 Kg/m2) n(%) | |||||

| Age | 15-34 years old | 77 (72.6%) | 29 (27.4%) | 1 | 1 | |

| 25-34 | 290 (76.7%) | 88 (23.3%) | 1.24 (0.76, 2.02) | 1.13(0.59, 2.17) | 0.722 | |

| Greater than 34 years old | 120 (69%) | 54 (31%) | 0.84 (0.49, 1.43) | 10.81 (0.36, 1.85) | 0623 | |

| Family size | Less than 5 | 199 (74%) | 70 (26%) | 0.99 (0.7, 1.42) | 0.46 (0.26, 0.81)* | 0.007 |

| 5 and above | 288 (74%) | 101 (26%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Age at first pregnancy | Less than 18 years old | 77 (62.1%) | 47 (37.9%) | 2.08 (1.38, 3.14)* | 3.72(2.13, 6.49)* | 0.0001 |

| 18 and above years old | 410 (76.9%) | 123 (23.1%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male involvement during ANC follow-up | Yes | 189 (77.8%) | 54 (22.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 154 (62.1%) | 94 (37.9%) | 2.14 (1.44, 3.18)* | 0.67 (0.43, 1.04) | 0.073 | |

| Place of delivery | Home | 162 (62.1%) | 99 (37.9%) | 2.76 (1.93, 3.94)* | 2.36 (1.50, 3.72)* | 0.0001 |

| Health facility | 325 (82.1%) | 71 (17.9%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attend postnatal visit | Yes | 190 (84.8%) | 34 (15.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 297 (68.6%) | 136 (31.4%) | 2.49 (1.64, 3.76)* | 1.25(0.73, 2.12) | 0.419 | |

| Nutritional education in the community | Yes | 219 (86.9%) | 33 (13.1%) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 268 (66.2%) | 137 (33.8%) | 3.29(2.17, 4.99)* | 5.5(1.8, 16.79)* | 0.003 | |

| Distance from health facility to home | Less than 3 kms | 107 (69%) | 48 (31%) | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 kms and above | 380 (75.7%) | 122 (24.3%) | 1.39 (0.93, 2.06) | 4.53(0.79, 25.72) | 0.088 | |

*Statistical significance at P-value<0.05, 1: reference group, AOR: adjusted odd ratio; COR: Crude odd ratio

Discussion

This study was conducted to assess the nutritional status and factors associated with underweight among lactating women in Womberma district, Northwest Ethiopia.

Based on the anthropometric measurement of body mass index, 72.9% of lactating women had normal nutritional status, BMI of 18.5 to 24.99 kg/m2 and 25.6% women were underweight, BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2. The 2011 EDHS report showed a 27% undernutrition among women [4]. A study conducted in Samre woreda, South Eastern Zone of Tigray also showed a 31% prevalence of underweight [14]. This is higher than the finding of the current study. The reason for the difference between the two studies could be due to the socioeconomic difference, and time difference in which the current study was conducted recently after several community-based interventions were undertaken.

A study conducted in rural Vietnam showed a 23.7% prevalence of malnutrition, which is lower than the current study [15]. The difference could be due to the sociodemographic difference between the two studies. And a similar study conducted among Lactating Women in India also showed a 36.6%, 19.3% and 10% prevalence of underweight among Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmiri women respectively [16]. The difference in the prevalence of underweight between the current study and the study in India could be due to the difference in the sociodemographic and economic differences between the two study areas.

Factors associated with underweight of lactating women were identified. Accordingly, respondents with less than five family size, women whose age of first pregnancy was less than 18 years, home delivery for the recent childbirth, and the absence of nutritional education programs in the community were significantly associated.

Women with less than five family size were less likely to be underweight when compared with women who have higher family size, five and above. This could be because of the food security issue in women with higher family size and related underweight and nutritional depletion of the mother due to successive pregnancies. A systematic review on the effect of births spacing on maternal or child nutritional outcomes showed that short interval between pregnancies is associated with adverse outcome in women’s nutritional status. The review showed significant association of short birth interval with increased risk for maternal anemia and with maternal serum zinc, copper, magnesium, ferritin, folate or thyroid-stimulating hormone [17]. A higher risk of undernutrition among women who have higher family size was also observed in a study conducted in Nekemte, Ethiopia [18].

Women who got pregnant before their eighteenth birthday were 3.7 times more likely to be underweight compared to their counterparts. This could be because of the immature anatomical and physiological conditions in younger women. Poor knowledge of younger women towards dietary intake during pregnancy and lactation could also have an impact on their nutritional status [19]. Studies conducted in Ethiopia also showed that women in the youngest age group (15–19) were more likely to be affected by undernutrition [20, 21]. A similar finding was observed in a study conducted among women of reproductive age in Nepal, which showed that younger women aged 15 to 24 years were almost three times more likely to be malnourished than older women [19].

Respondents who gave birth at home were more than two times more likely to be underweight when compared with women who deliver at a health institution. This could be explained by a reduced risk of obstetric complications in women who deliver at health institutions. Such risks include; hemorrhage which could influence the overall health status of the lactating women. In addition, women who deliver at health facility can get nutrition-related health education from health professionals, which will help them to adapt good behaviors related with nutrition and prevent malnutrition.

Women who did not get a regular nutritional education in their community were more than five times more likely to be underweight than those who got a nutritional education in their local area. This could be due to the positive effect of such educational programs on the healthy behaviors of the community [22]. This finding is similar to a study conducted in Nekemte which showed a lower prevalence of undernutrition in women who got health education about nutrition [18].

The current study has certain limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design, it may be difficult to establish a causal relationship between underweight and other independent variables. So, large-scale studies assessing a wide range of socioeconomic factors should be conducted for a better understanding of the factors associated with underweight among lactating women.

Conclusions

The prevalence of underweight among lactating women was found to be high. Women with large family size, who were pregnant at a younger age, home delivery for the recent childbirth, and the presence or absence of community-based nutritional education programs were significant factors associated with underweight among lactating women. Routine anthropometric measurements should be practiced for pregnant and lactating women for early identification of malnutrition at the community level. Government and other concerned bodies should focus on community-based health education programs on nutritional issues, and prevention mechanisms for early childbearing and short birth interval. Large-scale community-based studies should also be conducted for a better understanding of the nutritional status of lactating women and factors affecting it.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge to Debre Markos University, College of Health Sciences, to supervisors, data collectors, and study participants.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Authors’ contributions

SB participated in the design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation. GMK and MT also participated in the analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Debre Markos University, college of medicine and health science, ethical clearance committee. Permission was obtained from Womberma woreda administrative office. The importance of the study, data collection process, confidentiality and the ethical issue was briefly described for the study participants before data collection, and verbal consent was obtained. Parental or guardian verbal consent was obtained for participants below the age of 18. Lactating women who were found to be malnourished based on anthropometric measurement were recommended and referred to the nearest health institution for further follow-up and management.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal care

- AOR

Adjusted Odd Ratio

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- COR

Crude Odd Ratio

- EDHS

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- WHO

World Health Organization

Contributor Information

Sileshi Berihun, Email: sileshberihun@gmail.com.

Getachew Mullu Kassa, Phone: +251-920-17-40-29, Email: gechm2005@gmail.com.

Muluken Teshome, Email: mulukenteshome@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Blossner M, Onis M. Malnutrtion, quantifying the health impact at national and local levels. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takimoto H, et al. Nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women in Japan: a comparison with non-pregnant/non-lactating controls in the National Nutrition Survey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29(2):96–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2002.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black RE, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Statistical Agency Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and ORC Macro Calverton, USA . Ethiopia demographic and health survey. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black RE, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentine CJ, Wagner CL. Nutritional management of the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2013;60(1):261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ukegbu P, et al. Influence of maternal anthropometric measurements and dietary intake on lactation performance in Umuahia urban area, Abia state, Nigeria. Niger J Nutr Sci. 2012;33(2):31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolasa KM, Firnhaber G, Haven K. Diet for a healthy lactating woman. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58(4):893–901. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen LH. B vitamins in breast milk: relative importance of maternal status and intake, and effects on infant status and function. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(3):362–369. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bantamen G, Belaynew W, Dube J. Assessment of factors associated with malnutrition among under five years age children at Machakel Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia: a case control study. J Nutr Food Sci. 2014;4(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bain LE, et al. Malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: burden, causes and prospects. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:120. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.120.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amare B, et al. Nutritional status and dietary intake of urban residents in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:752. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Womberma woreda health office. Annual plan of womberma woreda health office and community health information system of 2015 to 2016, Womberma, Ethiopia.

- 14.Haileslassie K, Mulugeta A, Girma M. Feeding practices, nutritional status and associated factors of lactating women in Samre Woreda, south eastern zone of Tigray. Ethiopia Nutr J. 2013;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamori M, et al. Nutritional status of lactating mothers and their breast milk concentration of iron, zinc and copper in rural Vietnam. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2009;55(4):338–345. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.55.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan YM, Khan A. A study on factors influencing the nutritional status of lactating women in Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh regions. Inter J Advancements Res Technol. 2012;1(4):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ. Does birth spacing affect maternal or child nutritional status? A systematic literature review. Maternal & child nutrition. 2007;3(3):151–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hundera TD, Wirtu D, Gemede HF, Kenie DN. Nutritional status and associated factors among lactating mothers in Nekemte referral hospital and health centers. Int J Nutr Food Sci. 2015;4(2):216–222. doi: 10.11648/j.ijnfs.20150402.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhandari S, et al. Dietary intake patterns and nutritional status of women of reproductive age in Nepal: findings from a health survey. Archives Public Health. 2016;74(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13690-016-0114-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teller CH, Yimer G. Levels and determinants of malnutrition in adolescent and adult women in southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2015;14(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girma W, Genebo T. Determinants of the nutritional status of mothers and children in Ethiopia. Calverton: ORC Macro; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Wiley; 2008.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.