Abstract

Purpose of Review

The aim of this review is to summarize the development of the photoactivated depot (PAD) approach for the minimally invasive and continuously variable delivery of insulin.

Recent Findings

Using an insulin PAD, we have demonstrated that we can release native, bioactive insulin into diabetic animals in response to light signals from a small external LED light source. We have further shown that this released insulin retains bioactivity and reduces blood glucose. In addition, we have designed and constructed second generation materials that have high insulin densities, with the potential for multiple day delivery.

Summary

The PAD approach for insulin therapy holds promise for addressing the pressing need for continuously variable delivery methods that do not rely on pumps, and their myriad associated problems.

Keywords: insulin, protein delivery, light, glucagon, depot, insulin pump, artificial pancreas

Introduction

The body requires insulin in continuously varying amounts that depend on food intake and activity. For patients with type 1 diabetes, the only currently clinically used delivery method that meets this demand is the insulin pump. The insulin pump, or Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII) is an improvement over Multiple Daily Injections (MDI). It can reduce the number of hypoglycemic episodes observed and increase the convenience of administration. In addition, it reduces the number of injections required and allows for a more natural continuously variable delivery, as opposed to the inherent discrete dosing required of MDI.

But despite this, pumps are subject to a range of problems, all associated with the inherent physical connection of the insulin reservoir on the outside of the patient, and the delivery site on the inside of the patient. These include biofouling, occlusion, infection and crimping. Because of this, we are developing a photoactivated depot (PAD) to allow for the controlled release of insulin in a minimally invasive, continuously variable manner. These PAD materials are injectable into the skin, like normal insulin, but remain inactive until stimulated using a compact external LED light source. This source in turn can be driven by information from a continuous glucose monitor, and in so doing, create a closed loop artificial pancreas without the use of a pump. This article will review the motivation for the insulin PAD, its design, in-vivo validation and subsequent refinement.

Insulin, Highs and Lows

The discovery of insulin and its subsequent production on a large scale has been a triumph of modern biomedicine. Patients with type 1 diabetes are no longer burdened by the health consequences associated with high blood glucose or condemned to a severely shortened lifespan. Insulin that is no longer produced by the pancreas can now be provided exogenously, stimulating the cells of the body to absorb blood glucose, allowing it to be used as an energy source and reducing its toxic burden on the body.(1–3) The revolution in human health introduced by insulin however comes with new challenges. Because insulin is a protein, it is a substrate for proteases and peptidases and is as surely digested as any other dietary protein. Hence, insulin delivery has been traditionally limited to injections, typically subcutaneously, to avoid the rapid degradation associated with the GI tract.

A second and perhaps greater problem associated with insulin is the requirement for continuously variable delivery, as the body’s requirement for insulin varies continuously throughout the day (higher when blood glucose is high, lower when blood glucose is low). This differentiates insulin from most other therapeutics, which typically only need to remain above a static effective blood level. This then leads to the burden faced by people with type 1 diabetes, a lifelong requirement to a) determine their blood glucose level, b) make a decision based on this value, and c) administer an appropriate amount of insulin. In a sense, the person with diabetes and their medical team are being asked to act “in loco pancreas”. The mental wear and tear this represents can not be overstated. In addition, the consequences of over or under administering insulin can be acutely dangerous (in the case of hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis) or dangerous in the long term (in the case of hyperglycemia) with a risk of developing diabetic complications.

The Artificial Pancreas

Over 50 years ago, a solution to this problem was proffered: the artificial pancreas (AP).(4, 5) The AP was conceived of as capturing the essential functions of the pancreas, at least as regards to insulin release. These functions were a) the measuring of blood glucose, b) the calculation of a needed insulin dose and c) the delivery of the required insulin.(6–9) To a large extent, these three (Measure, Decide, Deliver) components have persisted and, to a degree, been optimized. Recently, several AP systems have been subjected to clinical trials, and shown to have similar or superior health outcomes in comparison with standard insulin therapy. Of the three pieces of an artificial pancreas, we argue that the Measure and Decide components have had significantly more innovation than has the Deliver component. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) have become smaller, more accurate and longer lived.(10–12) A range of technologies have been explored, including more traditional electrochemical quantitation of blood glucose and more recently, methods using optical signatures that follow binding to a glucose receptor. In the area of decision making, or algorithm development, multiple teams have made increasingly sophisticated algorithms that incorporate feedback, motion detection, and adaptation as well as the standard input from CGMs.(13–15)

Problems with Insulin Pumps

Only the delivery component of the AP has remained largely unchanged in the past decades. Conceived originally as a pump, it has remained in this form essentially until today. This manifests as a reservoir that is outside the body and which contains insulin, a motor that drives a piston or something similar, and a physical conduit for conveyance of the insulin into the body, typically a cannula or needle that terminates in the subcutaneous space. This conduit is the major source of problems associated with artificial pancreas systems. Perhaps the greatest problem is that of biofouling. The cannula opening is rapidly blocked through a combination of cellular responses to the foreign materials in the cannula, as well as protein deposits from the delivered insulin itself. Because of this, it is recommended that most infusion sets be replaced every two days or so. This biofouling process takes place at random intervals and so is hard to predict. The clinical consequence of biofouling is severe: a rapid reduction in insulin delivery and subsequent elevation in blood glucose levels.(16, 17)

Infection is an additional challenge that can compromise the conduit insertion site, and is a natural consequence of having a semi-permanent breach in the skin’s protective barrier. Other tissue responses include fibrosis and thickening of the tissue, which often necessitates the rotation of the cannula insertion site to alternative sites on the body. In addition to these biochemical and cellular problems, insulin pumps also have a physical problem associated with them. The conduit, whether cannula or needle, is subject to crimping, snagging, and dislodging as well.(18–25) These make pump usage challenging for a normal, active life.

A Potential Solution: The Insulin PhotoActivated Depot (PAD)

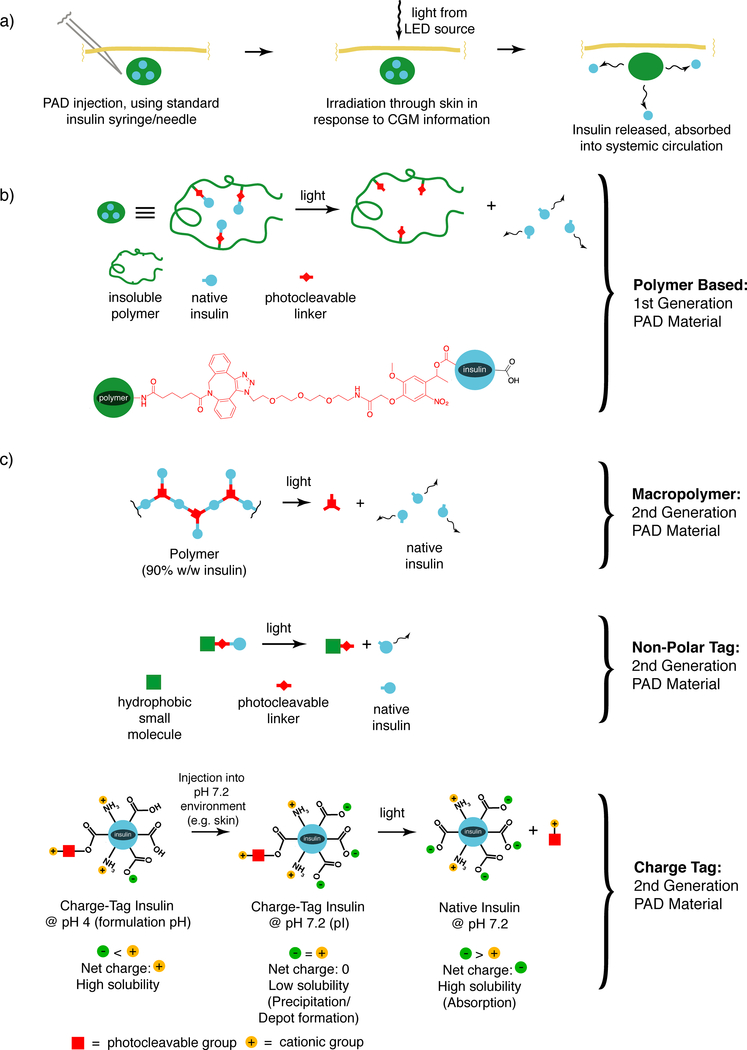

What we have sought is a way to capture the continuously variable delivery that is found in the insulin pump, without the inherent physical connection that is the source of so many associated problems. This has lead us to conceive of and develop the PAD approach for insulin delivery.(26) The overall approach is schematically depicted in Figure 1a. An insulin-containing material is injected into the skin, where it remains, inactive, at the site of injection. A small LED containing light source is placed on the surface of the skin on top of the injection site. In response to blood sugar information from a CGM, the light source sends pulses of light through the skin which stimulates the material to release insulin. By varying the intensity and/or duration of light from the light source, the amount of insulin released from the depot can be varied. And because light itself can be easily controlled, the amount of insulin released should be controllable as well, as long as the process of insulin release has been effectively linked to light exposure.

Figure 1. The photoactivated depot (PAD) approach for continuously variable insulin delivery.

a) The overall approach in schematic form, showing injection of the material into the skin, followed by transcutenous irradiation in response to blood glucose information, followed by insulin release and absorption. b) First generation PAD material design utilizing polymers in schematic form (top) and chemical form (bottom). c) Second generation PAD materials with ten-fold increased insulin density. Macropolymer (top), non-polar tag (middle) and charge tag (bottom).

The insulin PAD can therefore potentially provide the continuous variable delivery of a pump without the physical connection that a pump requires, and all of the problems associated with that physical connection. So then, how to actually achieve this aim? In the broadest sense we are attempting to link insulin solubility with a light triggered event. We want the insulin to remain insoluble at the site of injection so that we know where to aim the light to stimulate insulin release. Our first generation materials achieve this light-stimulated solubility shift by joining insulin to an injectable but insoluble polymer via a light cleaved linker (Figure 1b). Making and attaching this link, while conceptually straightforward, proved to be technically quite challenging. Ultimately, we made the link by using a new reagent of our own design that contains a reactive diazo group. This preferentially modifies the carboxyl groups found on the surface of insulin, and creates an ester link that is photolabile. Upon irradiation with the correct wavelength of light (365 nm in the case of the first-generation material) it will cleave, releasing native soluble insulin. From the earliest stages of this project, it was important to us to release insulin that had no additional atoms or moieties attached, in other words to be completely native, thereby limiting the potential for “downstream” issues associated with introducing an unnatural insulin into the body.

We incorporated an azide group into the linker which allowed us to conveniently make a second link of the modified insulin to an insoluble polymer using a “click” reaction. Our first generation material used a cross-linked polyethylene glycol (PEG) resin modified with a strained cyclooctyne moiety to allow this final link to be made. One can conceive of a wide range of ways of building this first-generation material, and we had to try multiple avenues before finding the approach described above. But once in place, the elements of it have proven to be quite robust, and the diazo attachment approach has remained a major strategy in constructing related materials.

Our first tests of this material were in-vitro.(26) We demonstrated that light released insulin with the expected molecular weight of 5808 Daltons. We showed that the material in the absence of light did not release insulin and that pulses of light from an LED light source resulted in pulses of insulin being released into the supernatant buffer above the insoluble polymeric material. Furthermore, we showed that the release of insulin with light showed release kinetics that were well fit by a first order rate law. This suggested to us that we can reasonably model the amount of insulin released for a given amount of light.

We then turned to an in-vivo assessment of a similar polymer based material.(27) All of our in vivo studies to date are based on the streptozotocin model of diabetes in the rat, an imperfect model that balances the ability to practically assess material performance with the relevance of the results to human health. We assessed the polymer based PAD materials using a dermal injection. The purpose of the dermal site was two-fold: to increase the accessibility of light to the depot and to increase the rate of insulin uptake after photo-release. The subcutaneous site remains a significant future possibility, with the main advantages being the increased injection volume and lower discomfort associated with injection. These are then balanced with the greater depth and hence lower accessibility of light to the site.

Using an injected dermal depot we were able to detect insulin release only in animals that had been irradiated using the LED light source. Control animals that had the material injected as well showed no release either prior to irradiation or after (the light being blocked by an aluminum foil sheet). Of particular note to us was the observation of insulin in the blood stream at the earliest time point (5 minutes post irradiation). This puts the PAD insulin in the same range as the fastest insulins, which could confer significant clinical benefit for an artificial pancreas system. In addition to insulin release we also were able to detect blood glucose reduction. This was a key observation, because it confirmed that the insulin that we used retained its biological activity despite having been involved in the multiple synthetic steps required to make the material. The final key observation we made in these earliest in-vivo studies was that we could induce the release of two pulses of insulin into the blood by irradiating the skin with two separate 30 second irradiation periods. This further supported the idea that insulin delivery can be metered by light. It should therefore be possible to incorporate the insulin PAD into an artificial pancreas system as the delivery component.

Deficits in 1st Generation PAD Materials

As effective as the first-generation polymer-based materials are, they have significant deficits that we have attempted to address in our subsequent materials. The first of these deficits is the dependence on polymers to make the material insoluble. After the insulin has been consumed there is then a need to clear the polymer from the depot site. One can conceive of a system in which the polymer is biodegradable, but then we are burdened with the tricky design issue of maintaining stability while the depot is being used, and then inducing instability after the insulin has been released. We would prefer to avoid this challenge. The second major problem associated with polymer use to induce insolubility is the overall insulin density of the materials. In our first-generation materials the final dry insulin content was ~10% w/w, meaning that 90% was polymer. We prefer materials in which insulin is the majority component, as this increases the potential lifetime of the depot, and also increases the ease with which the insulin is photoreleased. This is because the rate of photolysis increases with the density of photocleavable groups residing in the light beam. The increase in density can help address the requirement in humans for a greater number of moles of insulin released than that observed in our rat studies. While these studies showed blood insulin levels in the high pico-molar range (close to what is required of human efficacy), the number of moles required in a human subject is 200 fold higher, because of the 200 fold larger blood volume. But we can’t simply make the light source area 200 times larger, so we have to increase the moles released to get into the range of what is needed in humans. Depot density is a prime way of accomplishing this.

2nd Generation PAD Designs

We have addressed the issue of density and of reliance on polymers in multiple ways. All of these methods still couple insulin solubility with light but accomplish it without requiring linking to a polymer, and typically by using smaller solubility modulating moieties. Using these approaches we have generated materials that have dry insulin densities of ≥85% (see Figure 1c). In the first of these approaches, we created what we call a “macropolymer” in which the monomers that make up the polymer are insulin itself, which is then linked to other insulin monomers using light cleaved linkers.(28) The result is a highly insoluble material which is composed of mostly insulin, with a minority of the material consisting of light cleaved linkers.

The second approach we have pursued to eliminate polymers in the creation of PAD materials is what we call a “charge tag”.(29) With the charge tag approach, we modify insulin with a light cleaved group in a manner similar to our first-generation material. However to this group we have added cationic moieties that effectively shift the isoelectric point of the modified insulin from the normal value of 5.3 to a value of near 7. The result is that these modified insulins are soluble in formulation at slightly acidic pH values such as 5, but rapidly precipitate upon injection into a neutral environment such as the skin at pH ~7. Thus, they can remain homogenous in formulation but effectively form a depot upon injection. Then upon photolysis, the cationic groups are cleaved and native, soluble insulin released, to be taken up into the capillary bed and systemic circulation. Because the charge moieties are very low in molecular weight, these PAD materials are highly efficient, with dry insulin densities of approximately 90%.

The most recent approach we have examined for the elimination of polymers is the non-polar tag approach.(30) With this method insolubility is achieved by linking a highly non-polar group to insulin via a light cleaved linker. The result is a material that is >90% insulin and is highly insoluble. We have found that we can mechanically mill the material into low micron diameter particles. We can achieve suspensions using this approach of 20 mM which are easily injectable and which release native soluble insulin in response to photolysis. A 140 μl injection of such a suspension contains the equivalent of ~1 week worth of insulin for a typical adult patient.

Challenges

At this point in the development of the insulin PAD, there has been much to encourage us: we have materials that release insulin in response to light, that do not leach insulin in the absence of irradiation. We can release native, unmodified insulin without any additional atoms or linkers. The insulin released retains activity in-vivo, despite the synthetic processing required. We have demonstrated that we can alter the amount of insulin released in-vivo by altering the amount of light, and that we can achieve a robust reduction in blood glucose.

Given all of these positive signs, it is worthwhile at this point to examine some of the challenges that remain, and briefly explore possible solutions to these challenges. The first of these challenges is that of ambient light. There is a danger with a light triggered process that ambient light from unnatural and natural sources can stimulate the release of insulin. With insulin this is a particularly critical issue, as overdose has severe physiological consequences. We conceive of multiple approaches to deal with this issue. The first is to shadow the injection site with the light source. Having a strong adhesive affixing the light source over the depot site will eliminate ambient light and unintended insulin release.

We can also deal with ambient light by engineering the material and source such that insulin will only be released in significant quantities with the source. We have begun to examine this issue, determining the absolute irradiance of the solar spectrum and comparing it with the absolute irradiance in the narrow wavelength range that our LED light sources generate. Our observation is that our source can generate significantly higher intensity in this narrow range, and therefore with the right material, ambient light will have minimal release of insulin, akin to basal insulin release. There appears to be significant room for optimizing this interplay between the material and the light source.

A second major challenge is that of depot longevity, i.e. how long the depot can last after injection. In preliminary in-vivo studies we have observed a reduction in the insulin released on the second day after insulin PAD injection. This may be due to the nature of the material itself or the nature of the interaction of the material with the biological matrix. It is possible that this issue can be addressed by modification of the material or the injection site.

An additional potential challenge is that of immunogenicity. We have seen some signs of immune response at the depot site in dermal injections with some materials. Again, modulating the material itself may help minimize this phenomenon. Furthermore, injection into the subcutaneous space may reduce exposure and immunogenicity compared with the dermal site. The body’s tolerance to multiple long acting depot forms of insulin (e.g. degludec, glargine) suggests that immunogenicity can also be avoided in PAD materials that have similar levels of non-nativeness.

The final challenge that the insulin PAD faces is one that all insulin therapy faces: inter-patient variability. Skin depth differences, pigmentation differences, injection variations and other factors introduce variability into the delivery of insulin. We believe that we will have to incorporate adaptation into the control algorithm, wherein feedback from the CGM guides the amount of light administered. The expectation is that we will have a reasonable range of starting parameters, derived from in-vitro and in-vivo analysis, that will ultimately be fine tuned through feedback in the individual patient.

Next Steps

The focus of our next steps is closely linked with the challenges described above. A principal focus is on the number of insulin moles both contained by our depot, and the moles released in response to a tolerable dose of light. With the above described high-density materials, we have begun to address the issue of depot insulin content. With second generation materials, a tolerable injection volume of 140 μl can contain 7 days worth of insulin for an adult (~470 units). Our challenge is to release these with a tolerable light dose. To increase the ease of insulin release, we are focusing on the incorporation of new photocleavable groups into our materials with improved photolytic properties. These improved properties include higher photolysis wavelength and higher photolysis quantum yield. Our first materials use the di-methoxy nitro phenyl ethyl group (DMNPE) for photolysis, which utilizes 365 nm light in the far UV range. Incorporating longer wavelength photocleavable groups (i.e. in the visible range) can help eliminate any toxicity associated with far UV light. In addition, longer wavelengths have greater skin penetration potential, so that a larger proportion of the light applied can reach the depot site, leading to more efficient insulin release for a given amount of energy applied to the skin. Further improvements to the photocleavable group include increasing the amount of light absorbed by it (i.e. the extinction coefficient) and the yield of photolytic products formed upon absorption of a photon (the quantum yield). Improvements in these areas can lead to ten fold or greater release of insulin for a given energy of light.

In parallel to our work with insulin we are also examining the release of glucagon with light, as the best control of blood glucose should come from a combination of insulin and glucagon release, as is found in the healthy pancreas.(31, 32) Indeed, successful artificial pancreas trials have been advanced using twin pumps with both insulin and glucagon, with excellent results. Much of the technology that we have developed for light stimulated insulin release can be directly adapted for glucagon release. There is also the potential for photo-orthogonality, in which a single material could release insulin with one wavelength of light and release glucagon with a different wavelength of light.

Design Philosophy

We have approached the continuously variable delivery of insulin guided by a specific design philosophy: simplicity, both materially and operationally. We are aiming for substances that are as close to native insulin as possible, and incorporate the least amount of unnatural materials as possible. The rationale is multifold: simple materials have lower potential for toxicological issues. Simple materials that resemble insulin will have a lower potential for immune reaction. And finally, and perhaps most importantly, simple materials are more likely to be robust and work. This stands in contrast to more ambitious approaches such as smart insulins, in which the material is expected to do all three things a pancreas does: measure glucose, make a decision and finally meter insulin.(33, 34) We are asking PAD insulin to do only one thing and do it robustly: meter insulin in response to light. The glucose measuring is left to a CGM and the decision making is left to an algorithm. By limiting the PAD to a single purpose, we increase the chances that we can actually effectively achieve this goal.

In addition to this material simplicity we are also aiming for operational simplicity. We mean to make materials that are used in a fashion as close to current, familiar therapies. PADs are meant to be injected by the patient using a familiar 31G syringe in a completely analogous fashion to normal insulin, and we are trying to incorporate this characteristic from the earliest stages of design. Again, simplicity of materials and operation will increase the likelihood that these become actually incorporated into clinical practice and not exist solely as an academic exercise.

Conclusions

In this review we have described the PAD approach for the continuously variable delivery of insulin. Our motivation in pursuing this work is to address the significant deficits in currently existing delivery methods, specifically insulin pumps. We believe that the goal of controlling insulin delivery in a robust and minimally invasive way using light is well within reach and can be attained through the execution of the challenging but achievable steps outlined in this work. The result has the potential to change the lives of by relieving much of the lifelong burden associated with management of the disease.

Acknowledgments

The work reviewed in this article was largely executed by a group of talented and dedicated graduate students. They are: Piyush K. Jain, Dipu Karunakaran, Bhagyesh R. Sarode, Karthik Nadendla, Swetha Chintala, Parth Shah and Mayank Sharma.

In addition all animal studies were performed in collaboration with Professor Karen Kover (Childrens’ Mercy Hospital, Kansas City)

The work was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP3DK106921 as well as the support of a University of Missouri Fast Track Award and the UMKC School of Pharmacy Dean’s Bridge Fund.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Simon H. Friedman declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

References

Publications of particular interest published recently, have been highlighted as:

•Of importance

••Of major importance

- 1.Sonksen P, Sonksen J. Insulin: understanding its action in health and disease. Br J Anaesth. 2000. July;85(1):69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens E Insulin Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes. Medical Clinics of North America. 2015;99(1):145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Switzer SM, Moser EG, Rockler BE, Garg SK. Intensive Insulin Therapy in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2012;41(1):89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadish AH. Automation Control of Blood Sugar. I. A Servomechanism for Glucose Monitoring and Control. Am J Med Electron. 1964. Apr-Jun;3:82–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadish AH. Automation control of blood sugar a servomechanism for glucose monitoring and control. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1963;9:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battelino T, Omladiƒç JS, Phillip M. Closed loop insulin delivery in diabetes. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;29(3):315–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis T, Salahi A, Welsh JB, Bailey TS. Automated insulin pump suspension for hypoglycaemia mitigation: Development, implementation and implications. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2015;17(12):1126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forlenza GP, Buckingham B, Maahs DM. Progress in Diabetes Technology: Developments in Insulin Pumps, Continuous Glucose Monitors, and Progress towards the Artificial Pancreas. Journal of Pediatrics. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinzimer SA. Closed-loop artificial pancreas: Current studies and promise for the future. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2012;19(2):88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergenstal RM, Tamborlane WV, Ahmann A, Buse JB, Dailey G, Davis SN, et al. Effectiveness of sensor-augmented insulin-pump therapy in type 1 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(4):311–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Campbell AS, Wang J. Wearable non-invasive epidermal glucose sensors: A review. Talanta. [Article]. 2018;177:163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui SA, Zhang Y, Lloret J, Song H, Obradovic Z. Pain-free Blood Glucose Monitoring Using Wearable Sensors: Recent Advancements and Future Prospects. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. [Article in Press]. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boiroux D, Duun-Henriksen AK, Schmidt S, N√∏rgaard K, Poulsen NK, Madsen H, et al. Adaptive control in an artificial pancreas for people with type 1 diabetes. Control Engineering Practice. [Article]. 2017;58:332–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajizadeh I, Rashid M, Samadi S, Feng J, Sevil M, Hobbs N, et al. Adaptive and Personalized Plasma Insulin Concentration Estimation for Artificial Pancreas Systems. J Diabetes Sci Technol. [Article in Press]. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toffanin C, Visentin R, Messori M, Palma FD, Magni L, Cobelli C. Toward a Run-to-Run Adaptive Artificial Pancreas: In Silico Results. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. [Article]. 2018;65(3):479–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klonoff DC, Freckmann G, Heinemann L. Insulin Pump Occlusions: For Patients Who Have Been Around the (Infusion) Block. J Diabetes Sci Technol. [Review]. 2017;11(3):451–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slover RH. Best Ways and Practices to Avoid Insulin Pump Catheter Occlusions. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. [Note]. 2016;18(3):118–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinemann L Insulin infusion sets: A critical reappraisal. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. [Review]. 2016;18(5):327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinemann L, Fleming GA, Petrie JR, Holl RW, Bergenstal RM, Peters AL. Insulin pump risks and benefits: a clinical appraisal of pump safety standards, adverse event reporting and research needs. A Joint Statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association Diabetes Technology Working Group. Diabetologia. 2015;58(5):862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinemann L, Krinelke L. Insulin infusion set: The Achilles heel of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. J Diabetes Sci Technol. [Review]. 2012;6(4):954–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinemann L, Walsh J, Roberts R. We need more research and better designs for insulin infusion sets. J Diabetes Sci Technol. [Editorial]. 2014;8(2):199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda K, Takeshita Y, Kaneko S, Takamura T. Bending of a vertical cannula without alarm during insulin pump therapy as a cause of unexpected hyperglycemia: A Japanese issue? Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2015;6(6):739–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massa G, Gys I, Eyndt AO, Wauben K, Vanoppen A. Needle detachment from the Sure-T¬Æ infusion set in two young children with diabetes mellitus (DM) treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) and unexplained hyperglycaemia. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;28(1–2):237–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser C, Maurer K, Binder E, Meraner D, Steichen E, Abt D, et al. Needle detachment in a slim and physically active child with insulin pump treatment. Pediatric Diabetes. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plager P, Murati MA, Moran A, Sunni M. Two case reports of retained steel insulin pump infusion set needles. Pediatric Diabetes. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain PK, Karunakaran D, Friedman SH. Construction of a photoactivated insulin depot. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013;52(5):1404–9.••This was the first demonstration of the synthesis of insulin PAD materials, and showed that native insulin could be covalently linked to an insoluble resin, and then released in a controlled manner using light from an LED.

- 27.Sarode BR, Kover K, Tong PY, Zhang C, Friedman SH. Light control of insulin release and blood glucose using an injectable photoactivated depot. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2016;13(11):3835–41.••This was the first in-vivo demonstration of the insulin PAD approach. It demonstrated in diabetic rats that sufficient light could cross the skin during transdermal irradiation to stimulate insulin release. It further showed that insulin was released into the blood rapidly (within five minutes) and maintained its bioactivity, effecting blood glucose reduction.

- 28.Sarode BR, Jain PK, Friedman SH. Polymerizing Insulin with Photocleavable Linkers to Make Light-Sensitive Macropolymer Depot Materials. Macromol Biosci. 2016. August;16(8):1138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadendla K, Friedman SH. Light Control of Protein Solubility Through Isoelectric Point Modulation. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(49):17861–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadendla K, Sarode BR, Friedman SH. Hydrophobic Tags for Highly Efficient Light-Activated Protein Release. Mol Pharm. 2019. May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farhy LS, McCall AL. Glucagon -The new ‘insulin’ in the pathophysiology of diabetes. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2015;18(4):407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haidar A, Legault L, Messier V, Mitre TM, Leroux C, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Comparison of dual-hormone artificial pancreas, single-hormone artificial pancreas, and conventional insulin pump therapy for glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: An open-label randomised controlled crossover trial. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2015;3(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu Z, Aimetti AA, Wang Q, Dang TT, Zhang Y, Veiseh O, et al. Injectable nano-network for glucose-mediated insulin delivery. ACS Nano. 2013. 2013/05/28/;7(5):4194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rege NK, Phillips NFB, Weiss MA. Development of glucose-responsive ‘smart’ insulin systems. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017. August;24(4):267–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]