http://aasldpubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/10.1002/(ISSN)2046-2484/video/15-S1-interview-jalan a video presentation of this article

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Disease

- ACLF

acute‐on‐chronic liver failure

- AD

acute decompensation

- APASL

Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver

- CLIF‐OF

European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure Organ Failure

- EASL‐CLIF

European Association for the Study of the Liver–Chronic Liver Failure

- EF CLIF

European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- ICLFSG

International Chronic Liver Failure Study Group

- ICU

intensive care unit

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MELD

Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease

- NACSELD

North American Consortium for the Study of End‐Stage Liver Disease

- OF

organ failure

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TIPS

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

- WGO

World Gastroenterology Organization

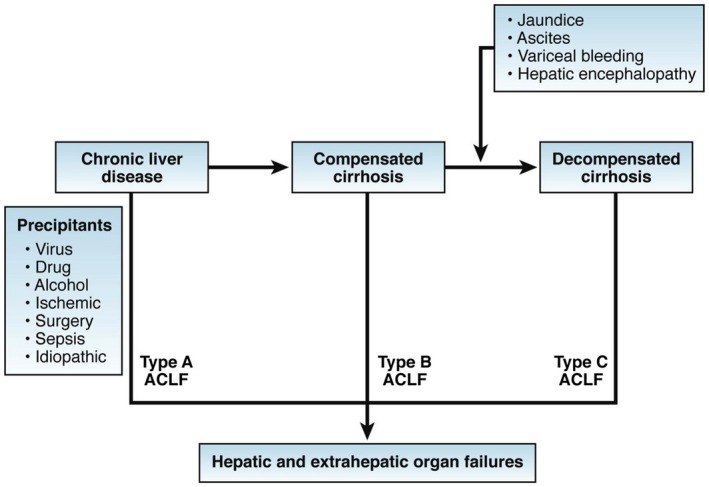

Clinical states of cirrhosis were traditionally represented in a comprehensive multistate model including compensated cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and late decompensated cirrhosis. Acute‐on‐chronic liver failure (ACLF, which is the first of several bewildering acronyms used in this field*) adds substantially to this multistate model by identifying a subgroup of patients with cirrhosis who progress rapidly after acute decompensation (AD) to development of organ failure(s) (OF[s]) and who experience high short‐term mortality (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Pathophysiological stages of cirrhosis and ACLF. This is the concept that was agreed by the WGO Working Party referred to in Table 2. Reproduced with permission from Gastroenterology.19 Copyright 2014, Elsevier.

Since its initial description,1 nearly 1000 articles have been published describing the clinical characteristics, prognostic models, and pathophysiology of ACLF. A number of studies describing novel approaches to treatment are also being developed. More than 10 definitions for the ACLF syndrome exist. Yet, so far, there has been only one prospective study—with the specific aim of defining the ACLF syndrome—that was performed by the European Association for the Study of the Liver–Chronic Liver Failure (EASL‐CLIF) Consortium, namely the CLIF Acute‐on‐Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis (CANONIC) Core Study.2 According to the results of this study, ACLF is defined as a specific syndrome in patients with cirrhosis that is characterized by AD, OF(s), and high short‐term mortality. AD itself is defined as the development of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and/or bacterial infections. ACLF may develop in patients without or with a prior history of AD. OFs involve the liver, kidney, brain, coagulation, respiratory system, and/or the circulation, and are defined either by: (1) the original CLIF‐Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score that has been adapted for liver patients (CLIF‐SOFA); or (2) its simplified version, the CLIF‐Consortium (C) OF score.3 The CLIF C ACLF score combines the European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure Organ Failure (CLIF‐OF) score with the patient’s age and white blood cell count to generate a composite score of 0 to 100 to allow prognostication of individual patients. This has been shown to be superior to the conventional prognostic scores used for patients with cirrhosis, such as the Child‐Turcotte‐Pugh score, the Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and the MELD‐Sodium score.3

High short‐term mortality means a 28‐day mortality rate ≥15%. Specific and cardinal pathophysiological features of ACLF are systemic and hepatic inflammation.2, 4 It is not clear whether systemic inflammation, manifested by elevated white cell count and C‐reactive protein levels, represents an alteration of host response to injury or an inability to resolve inflammation.

A detailed review of ACLF is beyond the scope of this article, which will focus on its historical aspects. This review will also discuss the impact the discovery of ACLF is having on health care, the economy, commerce, public policy, and international collaborations.

Historical Perspective

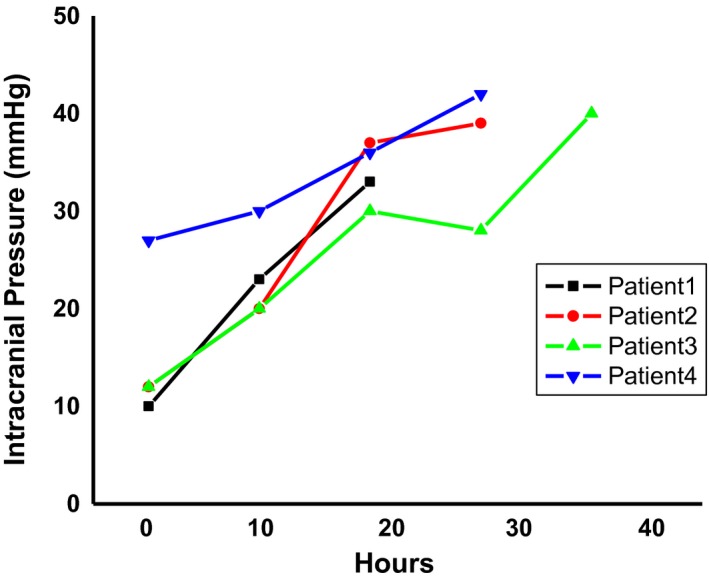

The ACLF concept as we know it today was first described by Jalan and Williams.1 The inspiration for considering this a new syndrome was the clinical observation that relatively young patients with cirrhosis were presenting to the hospital for the first time in multiorgan failure, ending up in the intensive care unit (ICU), and then dying. The background to this was the previous clinical observation made by Jalan et al.,5 in Edinburgh, that insertion of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in four patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding and sepsis led to the development of a syndrome that resembled acute liver failure (ALF) with the typical ALF manifestation of severe intracranial hypertension (Fig. 2). Cerebral edema, as seen in ALF, is rare in cirrhosis even with AD. One of the huge advantages that we had at The Middlesex and University College London Hospitals (which were where the clinical arm of the Institute of Hepatology was based at University College London) was relatively easy access to the excellent intensive care facilities, which embraced these very complex patients. The lack of a liver transplant service paradoxically was an advantage because it meant that competition for ICU beds was limited, because patients with ALF ended up in liver transplant centers, such as the Royal Free and Kings College Hospitals. The second factor that consolidated these early ideas was recognition of the importance of systemic inflammation in driving multiorgan dysfunction, namely, severe portal hypertension, HE, and renal dysfunction.6, 7, 8 Finally, we were able to secure funding from The Foundation for Liver Research and Industry to treat patients in clinical trials, by targeting inflammation using albumin dialysis and anti–tumor necrosis factor‐α therapy, providing us with access to relatively large numbers of patients.6, 7 Together, these early studies created the framework for ascertaining the elements that define ACLF. The early data suggested that the occurrence of OFs changed the natural history of patients with cirrhosis with AD. From the pathophysiological perspective, inflammation, and especially the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, was recognized as a distinctive feature. The chronology of activity to establish studies in ACLF is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Cerebral edema in patients with cirrhosis. The first report of cerebral edema and severe intracranial hypertension in patients with sepsis with cirrhosis after placement of TIPSs. The x axis depicts the time since insertion of transjugular intrahepatic stent‐shunt; the y axis shows the intracranial pressure (in mm Hg). These data first led to the idea that a patient with cirrhosis can manifest the cardinal sign of ALF, giving birth to the idea that a new syndrome, ACLF, may exist. Data are from Jalan et al.20

Table 1.

Chronology of Development of the Idea and Organizational Activity in ACLF Worldwide

| 1997 | Jalan R et al. Elevation of intracranial pressure following transjugular intra‐hepatic portosystemic stent‐shunt for variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol 1997;27:928‐933 |

| 2002 | Jalan R, Williams R. Acute‐on‐chronic liver failure: Pathophysiological basis of therapeutic options. Blood Purif 2002;20:252‐261 |

| 2003 | “Towards Defining ACLF” meeting at AASLD—Blei, Arroyo, Kamath, Garcia‐Tsao, Jalan and Williams; plans for ICLFSG shelved |

| 2004 | “Prospects for Liver Support” (University College London) |

| Concept of ACLF gaining acceptance | |

| Jalan R, Sen S, Williams R. Prospects for extracorporeal liver support. Gut 2004;53:890‐898 | |

| 2007 | EASL‐CLIF Consortium |

| First prospective study specifically to define ACLF started in 2009 | |

| 2009 | APASL |

| First consensus definition of ACLF | |

| 2012 | Publication of the first comprehensive review detailing pathophysiology: Jalan R, et al. J Hepatol 2012;57:1336‐1348 |

| 2013 | Publication of the CANONIC study: Moreau R, et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426‐1437 |

| 2014 | Publication of the CLIF‐C ACLF score: Jalan R, et al. J Hepatol 2014;61:1038‐1047 |

| 2014 | NACSELD established |

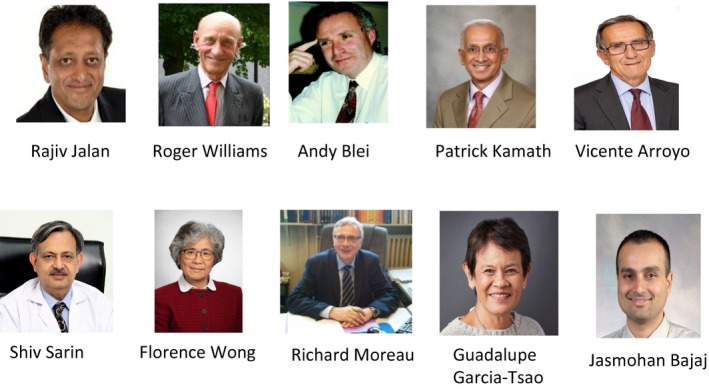

The first meeting to develop the idea further was entitled “Towards Defining ACLF.” This meeting was held at the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) meeting in 2003 (Fig. 3). Its proponents were the late Andy Blei (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), Vicente Arroyo (University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain), Patrick Kamath (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), and Guadalupe Garcia‐Tsao (Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT, and Yale University, New Haven, CT), in addition to Rajiv Jalan and Roger Williams (University College Hospital, University of London). A number of key investigators in the field of cirrhosis were invited to discuss the idea of the existence of this syndrome, and a proposal to perform a prospective study was developed. A supplement was produced from this meeting funded by a small grant from Teraklin Ltd., the company owning the molecular adsorbent recirculating system device. The initial idea was to develop an International Chronic Liver Failure Study Group (ICLFSG). This meeting was followed in 2004 by a meeting at University College London entitled “Prospects for Liver Support,” the proceedings of which were published.9 At this time, support for the concept of ACLF had started to take shape with both enthusiasm and also healthy skepticism. A smattering of talks at various meetings around the world, entitled “Acute‐on‐Chronic Liver Failure,” started to be entertained.

Figure 3.

Key early ACLF investigators worldwide.

The idea of the ICLFSG was discussed further over the following year, culminating in a debate as to whether the American and European Consortia should be run separately given the logistical difficulties. As a result of a letter sent by Vicente Arroyo to the Secretary General of EASL, seeking their blessing, in 2007, the EASL‐CLIF Consortium was formed. This partnership with EASL was crucial in providing the governance framework on which the future success of the Consortium relied. The Consortium received an unrestricted grant from Grifols, a Spanish multinational pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturer, to perform the first prospective study to develop diagnostic and prognostic criteria for ACLF, which was started in 2009 and published in 2013 supporting the hypothesis.2 This landmark study has been cited more than 1000 times and was led by Profs. Richard Moreau (Paris, France), Rajiv Jalan (London, United Kingdom), Pere Gines (Barcelona, Spain), Paolo Angeli (Padova, Italy), Dr. Marco Pavesi (Barcelona, Spain), and Prof. Vicente Arroyo (Barcelona, Spain) (Fig. 3).

This activity in Europe was paralleled by developments in Asia, led by Prof. Shiv Sarin (Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, New Delhi, India; Fig. 3) under the auspices of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL). APASL took a different approach and defined ACLF in 2009 based on a consensus rather than the results of a prospective study.10 In the United States, the North American Consortium for the Study of End‐Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) was formed by Drs. Jasmohan Bajaj (Virginia Commonwealth University, VA), Patrick Kamath (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Florence Wong (Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Canada), and Guadalupe Garcia‐Tsao (Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT, and Yale University, New Haven, CT)11 (Fig. 3). The key components of the definitions of ACLF by four major organizations are listed in Table 2. Very active groups working on ACLF have since been developed in China, led by Profs. Hai Li (Renji Hospital, Shanghai, China) and Lanjuan Li (Hangzhou, China). As mentioned earlier, over this period, about 1000 peer‐reviewed papers, reviews, and chapters have been published, and this new syndrome has started to have an influence worldwide in several areas, as discussed later.

Table 2.

Variations in Definitions of ACLF Worldwide

| Consortium | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APASL | EASL‐CLIF | NACSELD | WGO | |

| Diagnostic parameters | Acute jaundice and coagulopathy, followed by ascites ± HE <4 weeks in undiagnosed or diagnosed chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis | Specified criteria using CLIF‐OF score(s) for OF, 28‐day mortality rate >15% from AD of cirrhosis, without/with prior decompensation often caused by infection | Specified criteria for ≥2 OFs in patients with infection, at or during admission | Acute hepatic decompensation resulting in jaundice, elevated INR, and ≥1 or more OFs, with increased mortality in 28‐90 days, with or without previously diagnosed cirrhosis |

| Exclusion criteria | Bacterial infection or previous AD | Patients admitted electively for procedures or therapy, or those with hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria, or receiving immunosuppressive therapy, with HIV or with severe chronic extrahepatic disease | Outpatients with infection, any patient with HIV infection, prior organ transplants, or disseminated malignancies | None stated |

Impact of Recognition of ACLF as a New Syndrome

Impact on Health Care

The acceptance of ACLF as a new syndrome has stimulated widespread research across the world, with the setting up of new consortia as described earlier. The investment of resources into these consortia has led to the following benefits:

Reduction in mortality of patients with ACLF: In‐hospital mortality of patients with ACLF has reduced significantly from 65% to about 45%,12 albeit still unacceptably high.

Liver transplantation: In most parts of the world, organ allocation for liver transplantation is based on using the MELD score or its variant(s). New prognostic models and scoring systems for patients with ACLF have been developed that perform better than the MELD score3 and suggest that patients with ACLF are served poorly by the current organ allocation system. The results of these developments are helping to bring about discussions regarding changes to the organ allocation policies.13, 14

Development of new guidelines of care: Recognizing the devastating outcome of ACLF, a Consensus meeting, endorsed by the American Society of Transplantation, the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and EASL, was organized. The document arising therefrom details therapeutic strategies to manage patients with ACLF.15

Regulatory authority policies: The US Food and Drug Administration has recently recognized the importance of ACLF and awarded orphan drug designation to two drugs for the treatment of ACLF, TAK‐242 (Akaza) and Trimetazidine (Martin Pharmaceuticals).

Impact on the Economy

The use of the CLIF classification and scores allows early risk stratification of patients into those without and with ACLF, and the identification of patients who are likely to die. This allows earlier engagement with the ICU and liver transplantation teams, resulting in an increase in the total number of ICU admissions, yet a reduction in mortality12 (see Table 3 for an assessment of the cost of ACLF to the US economy in comparison with other serious illnesses). In contrast, new thresholds for futility of ongoing ICU care for patients with ACLF have been identified, to permit the release of precious ICU beds with the hope that patients and relatives will not be unduly distressed.16, 17, 18

Table 3.

Economic Burden of ACLF in the United States

| Total Cost per Year | Mean Cost per Admission | No. of Admissions per Year | Hospital Stay (days) | Mortality Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | $10 billion | $14,894 | 658,884 | 7 | 7 |

| ACLF | $1.8 billion | $51,841 | 32,335 | 16 | 50 |

| Pneumonia | $17 billion (all costs, including outpatient) | $7206 or $4913 | 1.1 million | 5.2 | 4.1 |

| Chronic heart failure | $32 billion? (all costs, including outpatient) | $10,775 | 1 million | 5 | 5.3 |

| Sepsis | $24.3 billion | $19,330 | 808,000 | 8.8 |

Modified with permission from Hepatology.12 Copyright 2016, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Impact on Commerce

Targeting ACLF is a growing priority in the various pharma and biotech companies that are involved in developing suitable drugs and devices. The ACLF research area is currently employing at least 150 researchers across the world, whereas the drug companies that are involved in ACLF research are investing more than $500 million into drug development. Examples of investment into ACLF are pharmaceuticals developed by Mallinckrodt and Takeda’s investment in Ambys. Cell therapy approaches are being developed by Promethera, whereas drug and device development is being undertaken by small‐ and medium‐size enterprises, such as Versantis, Yaqrit, Akaza, Thoeris, and Martin Pharma.

Impact on Public Policy and Practitioners

ACLF is making a huge impression on public policy in relation to allocation of organs, the effort for which is being spearheaded by the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association and the CLIF Consortium, which aim to find appropriate justification to allocate priority for patients with ACLF. The realization that ACLF is indeed a reversible condition is transforming early referral pathways in clinical networks, thereby yielding more rapid access to ICU care and facilitating recruitment of these patients into clinical trials.

Impact on International Development

ACLF is fostering international collaborations, which are improving the global relationships for liver diseases. Given the vast variations in the prevalence of liver diseases that are factors in ACLF worldwide and the differences in both the etiology of liver disease (predominantly alcohol in Europe, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States, and chronic viral hepatitis in the Far East) and triggers of AD (e.g., infection, alcoholic hepatitis, and reactivation of hepatitis B; Table 2), close collaborations in terms of exchanges of students, data, and clinical care pathways are underway. This will favor better international relations and overall improvement in the care of patients.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

It is clear that the discovery of ACLF as a distinct syndrome that occurs in patients with cirrhosis has reclassified cirrhosis, provided novel insights into disease pathogenesis, and generated new therapeutic targets. The academic funding organizations have taken notice of the importance of this syndrome and have started to invest in research groups studying ACLF. Many pharmaceutical companies have started to take an interest in finding solutions for this patient population, whose outlook has improved somewhat, but not sufficiently yet, over the past 30 years. ACLF continues to cost the taxpayer huge sums of money (Table 3). Increasing awareness of the ACLF syndrome, however, is leading to rapid referral of these patients to specialist centers. New research is leading to the discovery of new biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Liver transplantation is being used increasingly for these patients as rescue therapy. Taken together, it is to be expected that mortality rates of ACLF will start to plummet as physician awareness, education, and research advance; patients are engaged in clinical trials; and new therapies blossom.

The author of Ecclesiastes bemoans the monotony of life, and alleges that “there is nothing new under the sun.” Notwithstanding, the appreciation that ACLF is a syndrome distinct from simple AD was essentially a new observation, even though it is highly likely that it indeed represented an old disease hiding in plain sight.

Biographies

Potential conflict of interest: R.J. has served as a speaker, a consultant, and an advisory board member for Sequana Medical, Yaqrit, Mallinckrodt, Organovo, Prometic, and Takeda; has received research funding from Yaqrit and Takeda; owns stocks and shares in Yaqrit, Ammun, and Cyberlive; and owns the patents for Yaq‐001, DIALIVE, Ornithine Phenylacetate, and TLR4 antagonist.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jalan R, Williams R. Acute‐on‐chronic liver failure: pathophysiological basis of therapeutic options. Blood Purif 2002;20:252‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, et al. Acute‐on‐chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426‐1437, 1437.e1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute‐on‐chronic liver failure. J Hepatol 2014;61:1038‐1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clària J, Stauber RE, Coenraad MJ, et al. Systemic inflammation in decompensated cirrhosis: characterization and role in acute‐on‐chronic liver failure. Hepatology 2016;64:1249‐1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jalan R, Dabos K, Redhead DN, et al. Elevation of intracranial pressure following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent‐shunt for variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol 1997;27:928‐933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mookerjee RP, Sen S, Davies NA, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha is an important mediator of portal and systemic haemodynamic derangements in alcoholic hepatitis. Gut 2003;52:1182‐1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sen S, Davies NA, Mookerjee RP, et al. Pathophysiological effects of albumin dialysis in acute‐on‐chronic liver failure: a randomized controlled study. Liver Transpl 2004;10:1109‐1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, et al. Systemic inflammatory response exacerbates the neuropsychological effects of induced hyperammonemia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2004;40:247‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jalan R, Sen S, Williams R. Prospects for extracorporeal liver support. Gut 2004;53:890‐898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, et al. Acute‐on‐chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol Int 2009;3:269‐282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, et al. Survival in infection‐related acute‐on‐chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology 2014;60:250‐256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen AM, Kim WR, Moriarty JP, et al. Time trends in the health care burden and mortality of acute on chronic liver failure in the United States. Hepatology 2016;64:2165‐2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sundaram V, Jalan R, Wu T, et al. Factors associated with survival of patients with severe acute‐on‐chronic liver failure before and after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1381‐1391.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sundaram V, Shah P, Wong RJ, et al. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure grade 3 have greater 14‐day waitlist mortality than status‐1a patients. Hepatology 2019;70:334‐345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nadim MK, Durand F, Kellum JA, et al. Management of the critically ill patient with cirrhosis: a multidisciplinary perspective. J Hepatol 2016;64:717‐735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gustot T, Fernandez J, Garcia E, et al. Clinical course of acute‐on‐chronic liver failure syndrome and effects on prognosis. Hepatology 2015;62:243‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Engelmann C, Thomsen KL, Mookerjee RP. Response to intensive care is the key to prognosticate patients with severe acute‐on‐chronic liver failure. Crit Care Med 2019;47:e384‐e385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karvellas CJ, Garcia‐Lopez E, Fernandez J, et al. Dynamic prognostication in critically ill cirrhotic patients with multiorgan failure in ICUs in Europe and North America: a multicenter analysis. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1783‐1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jalan R, Yurdaydin C, Bajaj JS, et al.; World Gastroenterology Organization Working Party . Toward an improved definition of acute‐on‐chronic liver failure. Gastroenterology 2014;147:4‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jalan R, Dabos K, Redhead DN, et al. Elevation of intracranial pressure following transjugular intra‐hepatic portosystemic stent‐shunt for variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol 1997;27:928‐933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]