Abstract

The human body is a template for many state-of-the-art prosthetic devices and sensors. Perceptions of touch and pain are fundamental components of our daily lives that convey valuable information about our environment while also providing an element of protection from damage to our bodies. Advances in prosthesis designs and control mechanisms can aid an amputee’s ability to regain lost function but often lack meaningful tactile feedback or perception. Through transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) with an amputee, we discovered and quantified stimulation parameters to elicit innocuous (non-painful) and noxious (painful) tactile perceptions in the phantom hand. Electroencephalography (EEG) activity in somatosensory regions confirms phantom hand activation during stimulation. We invented a multilayered electronic dermis (e-dermis) with properties based on the behavior of mechanoreceptors and nociceptors to provide neuromorphic tactile information to an amputee. Our biologically inspired e-dermis enables a prosthesis and its user to perceive a continuous spectrum from innocuous to noxious touch through a neuromorphic interface that produces receptor-like spiking neural activity. In a Pain Detection Task (PDT), we show the ability of the prosthesis and amputee to differentiate non-painful or painful tactile stimuli using sensory feedback and a pain reflex feedback control system. In this work, an amputee can use perceptions of touch and pain to discriminate object curvature, including sharpness. This work demonstrates possibilities for creating a more natural sensation spanning a range of tactile stimuli for prosthetic hands.

Summary

A multilayered e-dermis allows for a prosthesis and an amputee to perceive a range of innocuous and noxious tactile stimuli.

Introduction

One of the primary functions of the somatosensory system is to provide exteroceptive sensations to help us perceive and react to stimuli from outside of our body (1). Our sense of touch is a crucial aspect of the somatosensory system and provides valuable information that enables us to interact with our surrounding environment. Tactile feedback, in conjunction with proprioception, allows us to perform many of our daily tasks that rely on the dexterous manipulation of our hands (2). Mechanoreceptors and free nerve endings in our skin give us the means to perceive tactile sensation (2). The primary mechanoreceptors in the glabrous skin that convey tactile information are Meissner corpuscles, Merkel cells, Ruffini endings, and Pacinian corpuscles. The Merkel cells and Ruffini endings are classified as slowly adapting (SA) and respond to sustained tactile loads. Meissner and Pacinian corpuscles are rapidly adapting (RA) and respond to the onset and offset of tactile stimulation (1, 3). More recently, research has shown the role of fingertips in coding tactile information (4) and extracting tactile features (5).

A vital component of our tactile perception is the sense of pain. Although often undesired, pain provides a protection mechanism when we experience a potentially damaging stimulus. In the event of an injury, increased sensitivity can even render innocuous stimuli as painful (6). Nociceptors are dedicated sensory afferents in both glabrous and non-glabrous skin responsible for conducting tactile stimuli that we perceive as painful (6). Nociceptors, free nerve endings in the epidermal layer of the skin act as high threshold mechanoreceptors (HTMRs) and respond to noxious stimuli through Aβ, Aδ, and C nerve fibers (1), which enables our perception of tactile pain. It was discovered that Aδ fiber HTMRs respond to both innocuous and noxious mechanical stimuli with an increase in impulse frequency while experiencing the noxious stimuli (7). It is also known that mechanoreceptor activation along with nociceptor activation helps inhibit our perception of pain, and our discomfort increases when only nociceptors are active (8), which helps explain our ability to perceive a range of innocuous and noxious sensations. Although novel approaches have improved prosthesis motor control (9), comprehensive sensory perceptions are not available in today’s prosthetic hands.

The undoubted importance of our sense of touch, and lack of sensory capabilities in today’s prostheses, has spurred research on artificial tactile sensors and restoring sensory feedback to those with upper limb loss. Novel sensor developments utilize flexible electronics (10–12), self-healing (13, 14) and recyclable materials (15), mechanoreceptor-inspired elements (16, 17), and even optoelectronic strain sensors (18), which will likely impact the future of prosthetic limbs. Local force feedback to a prosthesis is known to improve grasping (19), but in recent years there has been a major push towards providing sensory feedback to the prosthesis and the amputee. Groundbreaking results show that implanted peripheral nerve electrodes (20–23) as well as noninvasive electrical nerve stimulation methods (24) can successfully elicit sensations of touch in the phantom hand of amputees.

Recent approaches aim to mimic biological behavior of tactile receptors using advanced skin dynamics (25) and what are known as neuromorphic (26) models of tactile receptors for sensory feedback. A neuromorphic system aims to implement components of a neural system, for example the representation of touch through spiking activity based on biologically driven models. One reason for utilizing a neuromorphic approach is to create a biologically relevant representation of tactile information using actual mechanoreceptor characteristics. Neuromorphic techniques have been used to convey tactile sensations for differentiating textures using SA-like dynamics for the stimulation paradigm to an amputee through nerve stimulation (26) and for feedback to a prosthesis to enhance grip functionality (27). While important, methods of sensory feedback have been limited to sensations of pressure (21), proprioception (23), and texture (26) even though our perception of tactile information culminates in a sophisticated, multifaceted sensation that also includes stretch, temperature, and pain.

Current forms of tactile feedback fail to address the potentially harmful mechanical stimulations that could result in damage to cutaneous tissue, or, in this context, the prosthesis itself. We investigate the idea that a sensation of pain could benefit a prosthesis by introducing a sense of self-preservation and the ability to automatically release an object when pain is detected. Specifically, we implement a pain reflex in prosthesis hardware that mimics the functionality of the polysynaptic pain reflex found in biology (28–30). Pain serves multiple purposes in that it allows us to convey useful information about the environment to the amputee user while also preventing damage to the fingertips or cosmesis, a skin-like covering, of a prosthetic hand. It is worth noting that an ideal prosthesis would allow the user to maintain complete control and overrule pain reflexes if desired. However, in this paper we focus on the ability to detect pain through a neuromorphic interface and initiate an automated pain reflex in the prosthesis.

We postulate that the presence of both innocuous and noxious tactile signals will help in creating more advanced and realistic prosthetic limbs by providing a more complete representation of tactile information. We developed a multilayered electronic dermis (e-dermis) and neuromorphic interface to provide tactile information to enable the perception of touch and pain in an upper limb amputee and prosthesis. We show closed-loop feedback to a transhumeral amputee through transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) to elicit either innocuous or painful sensations in the phantom hand based on the area of activation on a prosthesis (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we identify unique features of peripheral nerve stimulation, specifically pulse width and frequency, that play key roles in providing both innocuous and noxious tactile feedback. Quantifying the differences in perception of sensory feedback, specifically innocuous and noxious sensations, adds dimensionality and breadth to the type and amount of information that can be transmitted to an upper limb amputee, which aids in object discrimination. Finally, we demonstrate the ability of the prosthesis and the user to differentiate between safe (innocuous) and painful (noxious) tactile sensations during grasping and appropriately react using a prosthesis reflex, modeled as a polysynaptic withdrawal reflex, to prevent damage and further pain.

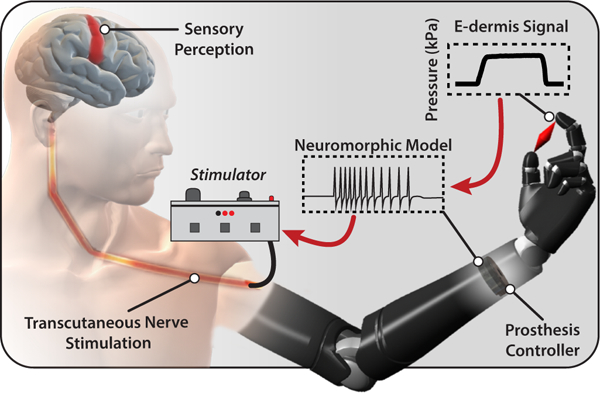

Fig. 1. Prosthesis system diagram.

Tactile information from object grasping is transformed into a neuromorphic signal through the prosthesis controller. The neuromorphic signal is used to transcutaneously stimulate peripheral nerves of an amputee to elicit sensory perceptions of touch and pain.

Results

Biologically inspired electronic dermis (e-dermis)

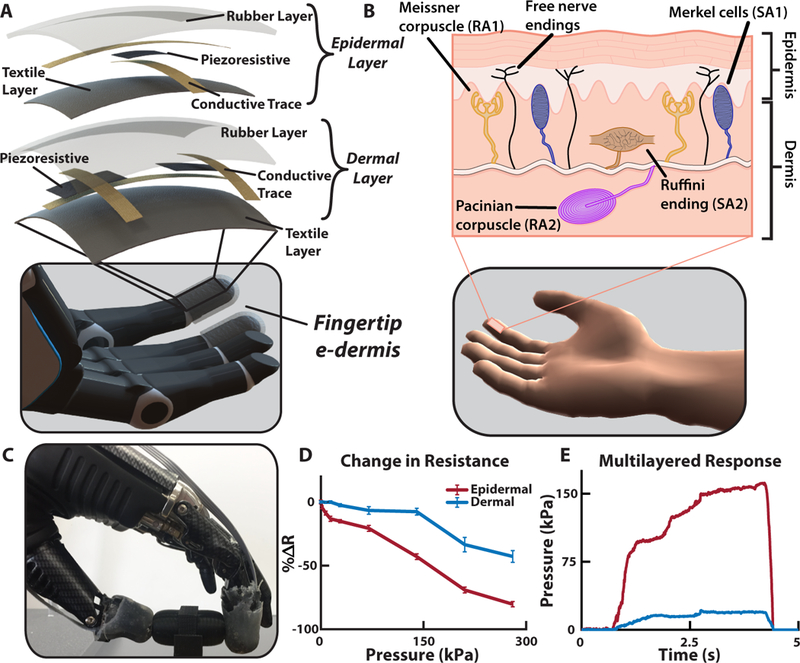

Mechanoreceptors in the human body are uniquely structured within the dermis and, in the case of Meissner corpuscles (RA1) and Merkel cells (SA1), lie close to the epidermis boundary (1). RA1 receptors are often found in the dermal papillae, which lend to their ability to detect movement across the skin, and SA1 receptors tend to organize at the base of the epidermis. However, in glabrous skin the HTMR free nerve endings extend into the epidermis (i.e. the outermost layer of skin) (1). We used this natural layering of tactile receptors to guide the multilayered approach of our e-dermis (Fig. 2A) to create sensing elements to capture signals analogous to those detected by mechanoreceptors (dermal) and nociceptors (epidermal) in healthy glabrous skin (Fig. 2B). The sensor was designed using a piezoresistive (Eeonyx, Pinole, USA) and conductive fabrics (LessEMF, Latham, USA) to measure applied pressure on the surface of the e-dermis. A 1 mm rubber layer (Dragon Skin 10, Smooth-On, Easton, USA) between the artificial epidermal (top) and dermal (bottom) sensing elements provides skin-like compliance and distributes loads during grasping. There are 3 tactile pixels, or taxels, with a combined sensing area of approximately 1.5 cm2 on each fingertip. The sensor layering resulted in variation of the e-dermis output during loading (Fig. 2C). The change in resistance in the tactile sensor was greater for the epidermal layer, enabling higher sensitivity. During grasping of an object, the e-dermis sensing layers, which were calibrated for a range of 0 – 300 kPa, exhibited differences in behavior. These differences can be used for extracting additional tactile information such as pressure distribution and object curvature (Fig. 2D-E).

Fig. 2. Multilayered e-dermis design and characterization.

(A) The multilayered e-dermis is made up of conductive and piezoresistive textiles encased in rubber. A dermal layer of two piezoresistive sensing elements are separated from the epidermal layer, which has one piezoresistive sensing element, with a 1 mm layer of silicone rubber. The e-dermis was fabricated to fit over the fingertips of a prosthetic hand. (B) The natural layering of mechanorecptors in healthy glabrous skin makes use of both rapidly (RA) and slowly adapting (SA) receptors to encode the complex properties of touch. Also present in the skin are free nerve endings (nociceptors) that are primarily responsible for conveying the sensation of pain in the fingertips. (C) The prosthesis with e-dermis fingertip sensors grasps an object. (D) The epidermal layer of the multilayered e-dermis design is more sensitive and has a larger change in resistance compared to the dermal layer. (E) Differences in sensing layer outputs are captured during object grasping and can be used for adding dimensionality to the tactile signal.

Touch and pain perception

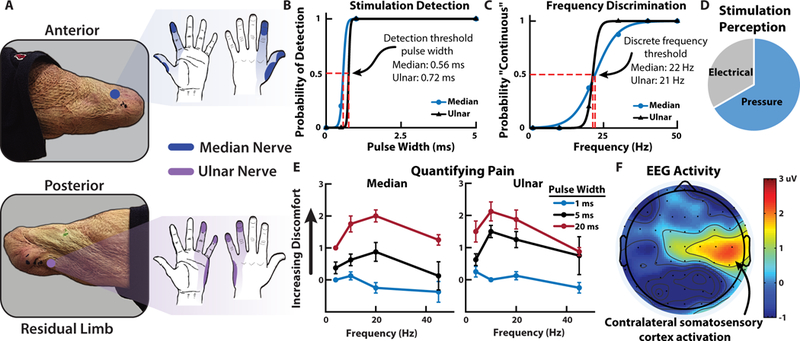

To provide sensory feedback, we used targeted TENS to extensively map and understand the perception of a transhumeral amputee’s phantom limb during sensory feedback, a method we previously demonstrated in multiple amputees (24). Although the participant did not undergo any targeted muscle or sensory reinnervation during surgery, there was a natural regrowth of peripheral nerves into the remaining muscles, soft tissue, and skin around the amputation. The median and ulnar nerves were identified on the amputee’s left residual limb and targeted for noninvasive electrical stimulation because these nerves innervated relevant areas of the phantom hand. The participant received more than 25 hours of sensory mapping in addition to over 150 trials of sensory stimulation experiments to quantify the perceptual qualities of the stimulation. Extensive mapping of the residual limb showed localized activation of the amputee’s phantom hand (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Sensory feedback and perception.

(A) Median and ulnar nerve sites on the amputee’s residual limb and the corresponding regions of activation in the phantom hand due to TENS. (B) Psychophysical experiments quantify the perception of the nerve stimulation including detection and (C) discrete frequency discrimination thresholds. In both cases the stimulation amplitude was held at 1.4 mA. (D) The perception of the nerve stimulation was largely a tactile pressure on the activated sites of the phantom hand although sensations of electrical tingling also occured. (E) The quantification of pain from nerve stimulation shows that the most noxious sensation is perceived at higher stimulation pulse widths with frequencies in the 10 – 20 Hz range. (F) Contralateral somatosensory cortex activation during nerve stimulation shows relevant cortical representation of sensory perception in the amputee participant (movie S1).

The amputee identified multiple unique regions of activation in his phantom hand from the electrical stimulation. The participant did not report any sensory activation, other than the physical presence of the probe, of his residual limb at the stimulation sites. He indicated that the dominating perceived sensation during stimulation occurred in his phantom hand, which is supported by our previous work (24). Cutaneous receptors on the residual limb respond to physical stimuli whereas the electrical stimulation activates the underlying peripheral nerves to activate the phantom hand. Psychophysical experiments showed the amputee’s perception of changes in stimulation pulse width and frequency on his median and ulnar nerves (Fig. 3B-C). In general, the stimulation was perceived primarily as pressure with some sensations of electrical tingling (paresthesia) (Fig. 3D). Stability of the participant’s sensory activation (fig. S1) and stimulation perceptual thresholds (fig. S2) were tracked over several months in his thumb and index fingers (median nerve) as well as his pinky finger (ulnar nerve).

Sensory feedback of noxious tactile stimuli was delivered using TENS to an amputee and the perception quantified. The results show that changes in both stimulation frequency and pulse width influence the perception of painful tactile sensations in the phantom hand (Fig. 3E). The relative discomfort of the tactile sensation was reported by the user on a modified comfort scale ranging from −1 (pleasant) to 10 (very intense, disabling pain that dominates the senses) (table S1). In this experiment, the highest perceived pain was rated as a 3, which corresponded to uncomfortable but tolerable pain. The most painful sensations were perceived at relatively low frequencies between 10 and 20 Hz. Higher frequency stimulation tends towards more pleasant tactile sensation, which is contrary to what might be expected when increasing stimulation frequency (31). In addition, very low frequencies generally resulted in innocuous activation of the phantom hand whereas frequency that are closer to the discrete detection boundary (15 – 30 Hz) resulted in the most noxious sensations in the activated region. We used electroencephalography (EEG) signals to localize and obtain an affirmation of the stimulus associated pain perception. The stimulation caused activation in contralateral somatosensory regions of the amputee’s brain, which corresponded to his left hand (Fig. 3F) (32). EEG activation during stimulation is significantly higher () than baseline activity, confirming the perceived phantom hand activation experienced by the user (fig. S3, movie S1).

Neuromorphic transduction

As mentioned previously, a neuromorphic system attempts to mimic the behavior found in the nervous system. Based on the results from the sensory mapping of the participant, the neuromorphic representation of the tactile signal was developed to enable the sensation of both touch and pain. To enable direct sensory feedback to an amputee through peripheral nerve stimulation, the e-dermis signal was transformed from a pressure signal into a biologically relevant signal using a neuromorphic model. The aim for the neuromorphic model was to capture elements of our actual neural system, in this case to represent the neural equivalent of a tactile signal for feedback to an amputee. To implement the biological activity from tactile receptors, namely the spiking response in the peripheral nerves due to a tactile event, we utilized the Izhikevich model of spiking neurons (33), which provides a neuron modeling framework based on known neural dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency and easily allowing for different neuron behaviors from parameter adjustments. The Izhikevich model has been used in previous work for providing tactile feedback to an amputee through nerve stimulation (26). In our work, mechanoreceptor and nociceptor models produced receptor-specific outputs, in terms of neuron voltage, based on the measured pressure signal on the prosthesis fingertips. The mechanoreceptor model combined characteristics of SA and RA receptors through the regular and fast spiking Izhikevich neurons, respectively, to convey more pleasant tactile feedback to the amputee. The nociceptor model utilized fast spiking Izhikevich neuron dynamics to mimic behavior of the free nerve endings.

When an object was grasped by the prosthesis, a higher number of active taxels indicated a larger distribution of the pressure on the fingertip, which was conveyed in the neuromorphic transduction as an innocuous (i.e. non-painful) tactile sensation. Changes in the tactile signal were captured in the neuromorphic transduction by changes in stimulation frequency and pulse width to correspond to the appropriate perceived levels of touch or pain during sensory feedback. Based on the results from the psychophysical experiments and the quantification of pain, the perception of noxious tactile feedback was achieved through the nociceptor model (see Materials and Methods).

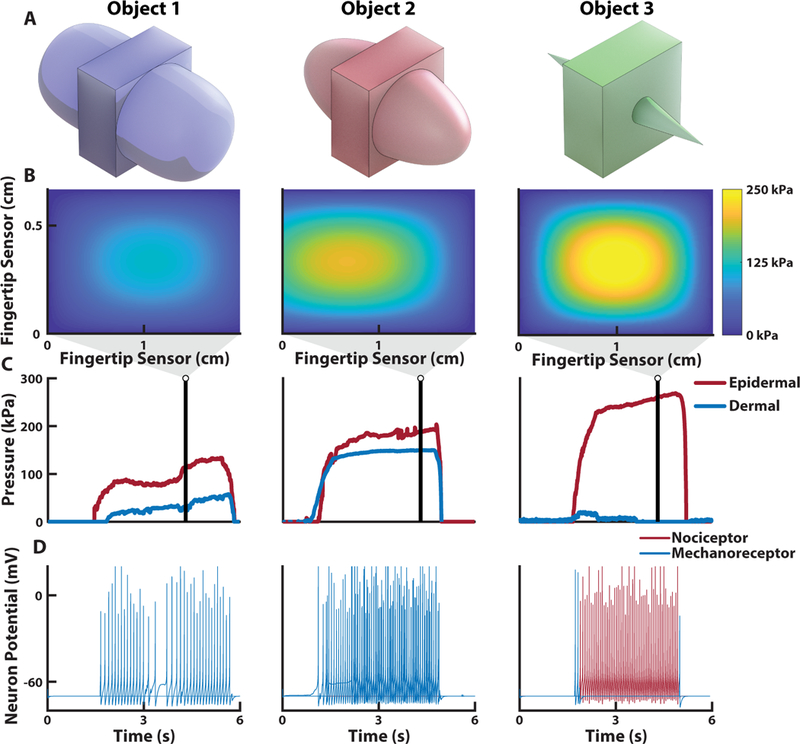

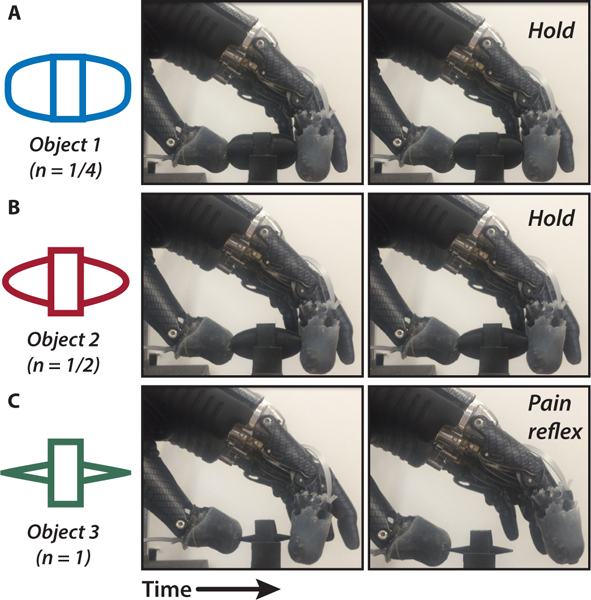

To demonstrate the neuromorphic representation of a tactile signal, three different objects were used, each of equal width but varying curvature, to elicit different types of tactile perception in the prosthesis during grasping (Fig. 4A). The objects follow a power law shape where the radius of curvature (Rc) was modified using the power law exponent n, which ranges between 0 and 1 and effectively defines the sharpness of the objects (see Materials and Methods). The power law exponents used were ¼, ½, and 1 and correspond to Object 1, Object 2, and Object 3, respectively. The response of the fingertip taxels during object loading captured differences in object curvature based on the relative activation of all sensing elements (Fig. 4B-C, movie S2). As expected, the epidermal layer was the most activated taxel during loading and absorbed the largest pressure. The sharp edge of Object 3 produced a highly localized pressure source on the epidermal layer of the e-dermis, which triggered the neuromorphic nociceptor model (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. E-dermis and neuromorphic tactile response from different objects.

(A) Three different objects, with equal width but varying curvature, are used to elicit tactile responses from the multilayered e-dermis. (B) The pressure heatmap from the fingertip sensor on a prosthetic hand during grasping of each object and (C) the corresponding pressure profile for each of the sensing layers. (D) The pressure profiles are converted to the input current, I, for the Izhikevich neuron model for sensory feedback to the amputee user (movie S2). Note the highly localized pressure during the grasping of Object 3 and the resulting nociceptor neuromorphic stimulation pattern, which is realized through changes in both stimulation pulse width and the neuromorphic model parameters.

Prosthesis tactile perception and pain reflex

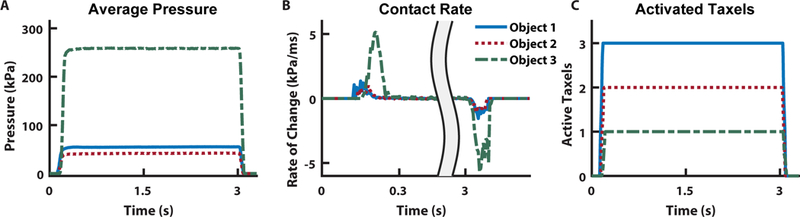

As an extension of the body, a prosthetic hand should exhibit similar behavior and functionality of a healthy hand. The perception of both innocuous touch and pain are valuable at both the local (i.e. the prosthetic hand) and the global (i.e. the user) levels. At the local level, a reflex behavior from the prosthesis to open when pain is detected can help prevent unintended damage to the hand or cosmesis. It should be noted that in an ideal prosthesis this reflex would be modulated by the user based on the perceived pain. To demonstrate a local closed-loop pain reflex, a prosthetic hand, with a multilayered e-dermis on the thumb and index finger, grasped, held, and released one of the previously described objects (Fig. 5A–5C). The sensor signals were used as feedback to the embedded prosthesis controller to enable differentiation of the various objects and determine pain. We used pressure distribution (Fig. 6A), contact rate (Fig. 6B), and the number of activated sensing elements per finger (Fig. 6C) as input features in a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) algorithm for object detection.

Fig. 5. Prosthesis grasping and control.

To demonstrate the ability of the prosthesis to determine safe (innocuous) or unsafe (painful) objects, we performed the pain detection task (PDT). The objects are (A) Object 1, (B) Object 2, and (C) Object 3, each of which are defined by their curvature. In the case of a painful object (Object 3), the prosthesis detects the sharp pressure and releases its grip through its pain reflex (movie S3).

Fig. 6. Tactile features for prosthesis perception.

To determine which object is being touched during grasping, we implemented LDA to discriminate between the independent classes. As input features into the algorithm, we used (A) sensor pressure values, (B) the rate of change of the pressure signal, and (C) the number of active sensing elements during loading.

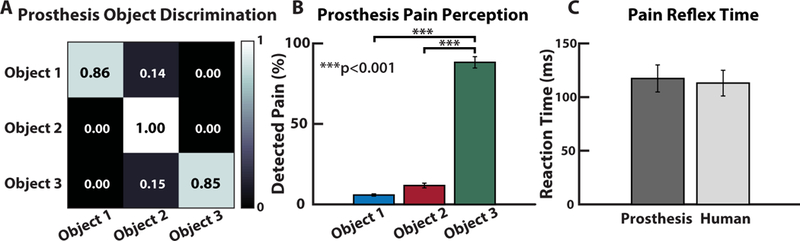

In the online Pain Detection Task (PDT), the prosthesis grabs, holds, and releases an object (movie S3). In this work, the curvature of Object 3 was assumed to be considered painful during grasping. When pain was detected, a prosthesis pain reflex caused the hand to open, releasing the object. Results showed the prosthesis’ ability to reliably detect which object is being grasped (Fig. 7A). The prosthesis had a high likelihood of perceiving pain while grasping Object 3 and a significantly less likelihood of perceiving pain for Objects 2 and 1 () (Fig. 7B). The reaction time for the prosthesis to complete a reflex after perceiving pain was recorded and was similar to reaction times in healthy humans from previously published data (28) (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7. Real-time prosthesis pain perception.

(A) The LDA classifier’s accuracy across the various conditions and (B) the percentage of trials where the prosthesis perceived pain during the online PDT. Note the high percentage of detected pain during the PDT for Object 3. (C) Pain reflex time of the prosthesis, using the rate of change of the pressure signal to determine object contact and release, compared to previously published data of pain reflex time in healthy adults (28).

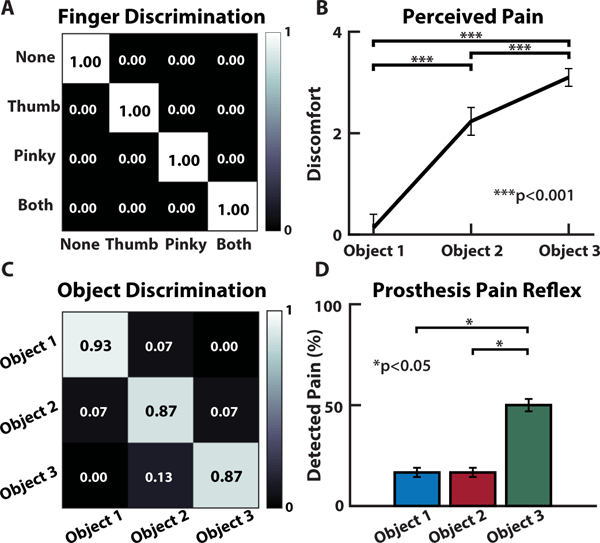

User tactile perception

With the added ability to perceive both innocuous and noxious tactile sensations in a single stimulation modality, an amputee user can utilize more realistic tactile sensations to discriminate between objects with a large or small (sharp) radius of curvature. The participant demonstrated his ability to perceive both innocuous and noxious tactile sensations by performing several discrimination tasks with a prosthetic hand. The neuromorphic tactile signal was passed from the prosthesis controller directly to the stimulator to provide sensory feedback to the amputee. The participant could reliably detect, with perfect accuracy, which of the fingers of the prosthesis were being loaded (Fig. 8A). The participant also received sensory feedback from varying levels of pressure applied to the prosthetic fingers. A light (< 100 kPa), medium (< 200 kPa), or hard (> 200 kPa) touch, as measured by the e-dermis, presented to the prosthesis was translated to the peripheral nerves of the amputee using the neuromorphic representation of touch (fig. S4 and S5). To demonstrate the ability of the prosthesis and user to perceive differences in object shape through variation in the comfort levels of sensory feedback, each of the three objects were presented to the prosthesis. Sensory feedback to the thumb and index finger regions of the phantom hand enabled the participant to perceive variations in the object curvatures, which was realized through changes in perceived comfort of the sensation. The results show an inversely proportional relationship between the radius of curvature of an object and the perceived discomfort of the tactile feedback (Fig. 8B). In addition to being able to perceive variation in sharpness of the objects as conveyed by the discomfort in the neuromorphic tactile feedback, the participant could reliably differentiate between the three objects with high accuracy (Fig. 8C). Finally, the participant performed the PDT with his prosthesis (movie S4). The prosthesis pain reflex control was implemented during the grasping task, which resulted in the prosthesis automatically releasing an object when pain was detected (see Materials and Methods). During actual amputee use, the prosthesis pain reflex registered over half of the Object 3 movements as painful, significantly more than for the other objects () (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8. Innocuous (mechanoreception) and noxious (nociception) prosthesis sensing and discrimination in an amputee.

(A) The amputee could discriminate which region of his phantom hand was activated, if at all. (B) Perception of pain increases with decreasing radius of curvature (i.e. increase in sharpness) for the objects presented to the prosthetic hand. (C) Discrimination accuracy shows the participant’s ability to reliably identify each object presented to the prosthesis based purely on the sensory feedback from the neuromorphic stimulation. (D) Results from the PDT during user controlled movements, with pain reflex enabled.

Responses from a subjective survey of the perception of the sensory stimulation show that the amputee felt as if the tactile sensations were coming directly from his phantom hand. In addition, the participant stated that he could clearly feel the touch of objects on the prosthetic hand and that it seemed that the objects themselves were the cause of the touch sensations that he was experiencing during the experiments (table S2).

Discussion

Perceiving touch and pain

Being able to quantify the perception of innocuous and noxious stimuli for tactile feedback in amputees is valuable in that it enables the replacement of an extremely valuable piece of sensory information: pain. Not only does pain play a role in providing tactile context about the type of object being manipulated, but it also acts as a mechanism for protecting the body. One could argue that this protective mechanism is not necessary in a prosthesis because it is merely an external tool or piece of hardware to an amputee user. We postulate that being able to capture noxious stimuli is actually more valuable to a prosthesis because it does not possess the same self-healing characteristics found in healthy human skin, although recent research has shown self-healing materials that could be used for future prosthetic limbs (13, 34). To enable an artificial sense of self-preservation, a noxious tactile signal is useful for the prosthesis to ensure it does not exceed the limits of a cosmetic covering or the hand itself. As prosthetic limbs become more sophisticated and sensory feedback becomes more ubiquitous, there will be a need to increase not just the resolution of tactile information but also the amount of useful information being passed to the user. We have identified how changing stimulation pulse width and frequencies enables a spectrum of tactile sensation that captures both innocuous and noxious perceptions in a single stimulation modality.

Our extensive phantom hand mapping, psychophysics, and EEG results support the use of TENS as providing relevant sensory information to an amputee. The EEG results are limited in that they do not provide detailed information on how changes in stimulation patterns are perceived, but they do show activation in sensory regions of the brain indicating relevant sensations in the amputee. Furthermore, the results from the user survey (table S2) showed that sensory feedback helped the amputee better perceive his phantom hand and that objects being grabbed by the prosthesis were perceived as being the source of the sensation, which helps support the neuromorphic stimulation as a valid approach for providing relevant sensory feedback.

The results from the PDT showed the ability of the prosthesis to detect pain and reflex to release the object. Object 3 was overwhelmingly detected as painful, due to its sharp edge (Fig. 7B). The high success rate for detecting and preventing pain for the benchtop PDT is likely due to the controlled nature of the prosthesis grip. The likelihood of detecting Object 3 as painful decreased and the chances of pain being detected for the other objects increased during the PDT with a user controlled prosthesis (Fig. 8D); however, pain detection and reflex were still significantly more likely for Object 3 (). This shift in pain detection is likely due to the amputee’s freedom to pick up the objects with his prosthesis in any way he chose. The variability in grasping orientation and approach for each trial resulted in more instances where Object 3 was not perceived as painful by the prosthesis. The ability to handle objects in different positions and orientations raises an interesting point in that the amount of pain produced is not an inherent property of an object, rather it is dependent on the way in which it is grasped. A sharp edge may still be safely manipulated without pain if the pressure on the skin does not exceed the threshold for pain. To reliably encode both touch and pain for prostheses, tactile signals should be analyzed in terms of pressure as opposed to grip force.

The prosthesis pain reflex presented here is autonomous, but one possibility is to use the amputee’s electromyography (EMG) signal as an additional input to the reflex model to enable modulation of the pain sensitivity perceived by the prosthesis. In this work, the pain sensation was not severe enough to generate a significant EMG reflex signal, so the reflex decision was made by the prosthesis instead of the user. The time for a user to process sensory feedback and produce a voluntary contraction is over 1 s (35), which is why we implemented an autonomous prosthesis pain reflex to achieve a response time closer to what is found in biology (Fig. 7C). Biologically, this autonomous response is equivalent to a fast spinal reflex compared to the slower cortical response for producing a voluntary EMG signal for controlling limb movement.

Another major implication of this work is in the quantification of the perceived noxious and innocuous tactile sensations during transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation of peripheral afferents. One might assume that an increase in discomfort would be associated with an increase in delivered charge; however, we found that the most painful sensations during tactile feedback to an amputee delivered through TENS were primarily dictated by an increase in stimulation pulse width as well as stimulation frequency. Specifically, frequencies that were near the discrete detection boundary (15 – 30 Hz) were perceived as more painful than higher frequencies. Changes in stimulation frequency seemed to have the largest influence on the perceptions of touch and pain while pulse width affected intensity of the sensation (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, we demonstrated real-time discrimination between object curvature based purely on perceived discomfort in tactile feedback, which was associated with sharpness of the objects by the participant.

Neuromorphic touch

The ability of the participant to discriminate objects, specifically those that cause pain, is rooted in the neuromorphic tactile transduction and corresponding nerve stimulation. The psychophysical results illuminate the unique stimulation paradigms necessary to elicit tactile sensations that correspond to both mechanoreceptors and nociceptors in the phantom hand of an amputee.

More sophisticated neuron models exist and could be used to capture behavior of individual receptors and transduction (25); however, the limitation of hardware prevents the stimulation of individual afferent nerve fibers. The Izhikevich model is simplistic in its dynamics but still follows basic qualities of integrate-and-fire models with voltage non-linearity for spike generation and extremely low computational requirements, which allow for the creation of a wide variety of neuron behaviors (33). The advantage of the neuromorphic representation of touch in our work is that we can transform signals from the multilayered e-dermis directly into the appropriate stimulation paradigm needed to elicit the desired sensory percepts in the amputee participant. Specifically, the combination of mechanoreceptor and nociceptor outputs enables additional touch dimensionality while maintaining a single modality of feedback, both in physical location and stimulation type. This combination allows the user to better differentiate between the objects based on their unique evoked perceptions for each object (Fig. 8B-C).

The limitation of this work is the small study sample. Although this work is a case study with a single amputee, the extensive psychophysical experiments and stability (Fig. S1 and S2) of the results over several months show promise that other amputees would experience a similar type of perception from TENS, a technique we have previously validated for activating relevant phantom hand regions in multiple amputees (24). However, the psychophysics will likely have slight differences based on age and condition of the amputation. The results are promising in that the stimulation parameters used to elicit pain or touch followed the same trend in both median and ulnar nerve sites of the amputee (Fig. 3E). A major implication of this work is the idea that both innocuous and noxious touch can be conveyed using the same stimulation modality. In addition, we showed that it is not necessarily a large amount of injected charge into the peripheral nerves that elicits a painful sensation. Rather, a unique combination of stimulation pulse width and frequency at the discrete detection boundary appears to create the most noxious sensations. Additional amputee participants who are willing to undergo nerve stimulation, sensory mapping, and psychophysical experiments to the quantify their perceived pain would be needed to allow us to generalize the clinical significance to a wider amputee population. Our findings have applications not only in prosthetic limb technology but for robotic devices in general, especially devices that rely on tactile information or interactions with external objects. The overarching idea of capturing meaningful tactile information continues to become a reality as we can now incorporate both innocuous and noxious information in a single channel of stimulation. Whether it is used for sensory feedback or internal processing in a robot, the sense of touch and pain together enable a more complete perception of the workspace.

This study illustrates, through demonstration in a prosthesis and amputee participant, the ability to quantify and utilize tactile information that is represented by a neuromorphic interface as both mechanoreceptor and nociceptor signals. Through our demonstration of capturing and conveying a range of tactile signals, prostheses and robots can incorporate more complex components of touch, namely differentiating innocuous and noxious stimuli, to behave in a more realistic fashion. The sense of touch provides added benefit during manipulation in prostheses and robots, but the sense of pain enhances their capabilities by introducing a novel sense of self preservation and protection.

Materials and Methods

Objectives and study design

Our objectives were to show that 1) a prosthetic hand was capable of perceiving both touch and pain through a multilayered e-dermis and 2) an amputee was capable of perceiving the sense of both touch and pain through targeted peripheral nerve stimulation using a neuromorphic stimulation model.

Participant recruitment

All experiments were approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board. The amputee participant was recruited from a previous study at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD. At the time of the experiments, the participant was a 29-year-old male with a bilateral amputation 5 years prior, due to tissue necrosis from septicemia. The participant has a transradial amputation of the right arm and a transhumeral amputation of the left arm. The left arm was used for all sensory feedback and controlling the prosthesis in this work. The participant consented to participate in all the experiments and to have images and recordings taken during the experiments used for publication and presentations. After 2 months of sensory mapping, the experiments were performed on average once every 2 weeks over a period of 3 months with follow up sessions after 2, 5, and 8 months. EEG data was collected in one session over a period of 2 hours.

Sensory Feedback

The sensory feedback experiments consisted of TENS of the median and ulnar nerves using monophasic square wave pulses. We performed mapping of the phantom hand using a 1 mm beryllium copper (BeCu) probe connected to an isolated current stimulator (DS3, Digitimer Ltd., UK). An amplitude of 0.8 mA and frequency of 2 – 4 Hz were used while mapping the phantom hand. Anatomical and ink markers were used, along with photographs of the amputee’s limb, to map the areas of the residual limb to the phantom hand. For all other stimulation experiments, we used a 5 mm disposable Ag-Ag/Cl electrode. A 64-channel EEG cap with Ag-Ag/Cl electrodes (impedance) was used for the EEG experiment. The participant was seated and stimulation electrodes were placed on his median and ulnar nerves. Each site was stimulated individually for a period of 2 s followed by a 4 s delay with 25% jitter before the next stimulation. There was a total of 60 stimulation presentations with varying pulse width (1–20 ms) and frequencies (4–45 Hz) with an amplitude of 1.6 mA. A time window of 450 ms starting at 400 ms after stimulation was used to average EEG activity across trials and compared to baseline activity using methods similar to those in (36).

Psychophysical Experiments

Psychophysical experiments were performed to quantify the perception of TENS on the median, radial, and ulnar nerves of the amputee. Experiments included sensitivity detection (varying pulse width at 20 Hz), detection of discrete versus continuous stimulation (varying frequency with pulse width of 5 ms), and scaled pain discrimination. For the pain discrimination experiment the participant used a discomfort scale that ranged from pleasant or enjoyable (−1) to no pain (0) to very intense pain (10) (table S1). Stimulation current amplitude was held at 2 mA while frequency and pulse width were modulated to quantify the effect of signal modulation on perception in the participant’s phantom hand. Every electrical stimulation was presented as a 2 s burst with at least 5 s rest before the next stimulation. Experiments were conducted in blocks up to 5 min with a break up to 10 min between each block. Every stimulation condition was presented up to 10 times and at least 4 times. Psychometric functions were fit using a sigmoid link (24).

E-dermis fabrication

The multilayered e-dermis was constructed from piezoresistive transducing fabric (Eeonyx, USA) placed between crossing conductive traces (stretch conductive fabric, LessEMF, USA), similar to the procedure described in previous work (37). The piezoresistive material is pressure sensitive and decreases in resistance with increased loading. The intersection of the conductive traces created a sensing taxel, a tactile element. Human anatomy expresses a lower density of nociceptors, compared to mechanoreceptors, in the fingertip (38). So, we designed the epidermal layer as a 1 × 1 sensing array while the dermal layer was a 2 × 1 array (Fig. 2A). The size of the prosthesis fingertip and the available inputs to the prosthesis controller limited the number of sensing elements to 3 per finger. The piezoresistive and conductive fabrics were held in place by a fusible tricot fabric with heat activated adhesive. A 1 mm layer of silicone rubber (Dragon Skin 10, Smooth-On, USA) was poured between two sensing layers. After the intermediate rubber layer cured, the textile sensors were wrapped into the fingertip shape and a 2 mm layer of silicone rubber (Dragon Skin 10, Smooth-On, USA) was poured as an outer protection and compliance layer, which is known to benefit prosthesis grasping (19). The e-dermis was placed over the thumb, index, and pinky phalanges of a prosthetic hand (Fig. 1B).

Prosthesis control

A bebionic™ prosthetic hand (Ottobock, Duderstadt, Germany) was used for the experiments. Prosthesis movement was controlled using a custom control board, with an ARM Cortex-M processor, developed by Infinite Biomedical Technologies (IBT) (Baltimore, USA). The board was used for interfacing with the prosthesis, reading in the sensor signals, controlling the stimulator, and implementing the neuromorphic model. During the user controlled PDT, the amputee used his own prosthesis (fig. S6), a bebionic™ hand with Motion Control wrist and a UtahArm 3+ arm with elbow (Motion Control Inc, Salt Lake City, USA). The amputee controlled his prosthesis using a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) algorithm on an IBT control board for EMG pattern recognition. The electrodes within his socket were bipolar Ag-Ag/Cl EMG electrodes from IBT.

Neuromorphic models

We implemented artificial mechanoreceptor and nociceptor models to emulate natural tactile coding in the peripheral nerve. We tuned the model to match the known characterization of TENS in the amputee to elicit the appropriate sensation. Constant current was applied during stimulation and both pulse width and spiking frequency were modulated by the model. Higher grip force was linked to increased stimulation pulse width and frequency, which was perceived as increased intensity in the phantom hand. Innocuous tactile stimuli resulted in shorter pulse widths (1 ms or 5 ms) whereas the noxious stimuli produced a longer pulse width (20 ms), a major contributor to the perception of pain through TENS as shown by the results. To create the sensation of pain, we varied the parameters of the model in real-time based on the output of the e-dermis. We converted the e-dermis output to neural spikes in real-time by implementing the Izhikevich neuron framework (33) in the embedded C++ software on the prosthesis control board. The output of the embedded neuromorphic model on the control board was used to control the stimulator for sensory feedback. The neuromorphic mechanoreceptor model was a combination of SA and RA receptors modelled as regular and fast spiking neurons. The nociceptor model was made up of Aδ neurons, which were modeled as fast spiking neurons to elicit a painful sensation in the phantom hand. It should be noted that the fast spiking neuron model was perceived as noxious with an increase in pulse width, which allows us to use the same Izhikevich neuron for both mechanoreceptors and nociceptors. The e-dermis output was used as the input current, I, to the artificial neuron model. The evolution of the membrane potential v and the refractory variable u are described by Eq. 1 and 2. When the membrane potential reaches the threshold vth the artificial neuron spikes. The membrane potential was reset to c and the membrane recovery variable u was increased by a predetermined amount d (Eq. 3). The spiking output was used to directly control the TENS unit for sensory feedback.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Because we are not directly stimulating individual afferents in the peripheral nerves we tuned the model to represent behavior of a population of neurons. The parameters used for the different receptor types were: ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; and

R is dimensionless in this model. The fast spiking neurons fire with high frequency with little adaptation, similar to responses from nociceptors during intense, noxious stimuli (7). In the model, fast spiking is represented by a very fast recovery (a). Values for the parameters were taken from (26) and (33).

We limited the spiking frequency of the neuromorphic model to 40 Hz and 20 Hz for the mechanoreceptor and nociceptor models, respectively. The transition of the neuromorphic model from mechanoreceptors to nociceptors relies on the pressure measured at the fingertips of the prosthesis, the number of active sensing elements, and the standard deviation of the pressure signal across the active taxels. The prosthesis fingertip pressure (P) is used to determine the neuromorphic stimulation model for sensory feedback. Highly localized pressure above a threshold triggers the FS model whereas the RS model is used in cases of more distributed fingertip pressure. The following pseudocode explains how the stimulation model is chosen, where , n is the number of active taxels, and pw is the stimulation pulse width:

Prosthesis pain reflex

To mimic biology, we modeled the prosthesis pain withdrawal as a polysynaptic reflex (29, 30) in the prosthesis hardware. In our model, the prosthesis controller was treated as the spinal cord for the polysynaptic reflex. The nociceptor signal was the input, I(t), to an integrating interneuron Γ whose output was the input to an alpha motor neuron, which triggered the withdrawal reflex through a prosthesis hand open command after ~100 ms of pain. Both neurons can be modelled as leaky-integrate-and-fire with a synapse from the alpha motor neuron causing the reflex movement (Eq. 4 and 5, fig. S7), similar to the EMG signals generated during a nociceptive reflex (39).

| (4) |

| (5) |

Both neurons had time constant , resting potential , membrane resistance , and a spiking threshold of . The time step was 5 ms and the nociceptor signal was normalized, enveloped, and scaled by . The prosthesis reflex parameters were chosen to trigger hand withdrawal after ~100 ms of pain to mimic the pain reflex in healthy humans (28). Fingertip pressure, the rate of contact, and the number of active sensing elements on each fingertip were used as features for an LDA algorithm to detect the different objects. Object 3 was labeled as a painful object. A taxel was considered active if it measured a pressure greater than 10 kPa. The pattern recognition algorithm was trained using sensor data from 5 trials of prosthesis grasping for each object and validated on 10 different trials.

Object design and fabrication

We created 3 objects of equal size with varying edge curvatures, defined by the edge blend radius, using a Dimension 1200es 3D printer (Stratasys, USA). Each object has a width of 5 cm but differed in curvature. Each object’s curvature followed a power law where the leading edge of the protrusions vary in blend radii and range from flat to sharp. The radius of curvature, , of the leading edge can be modified by the body power law exponent, where

| (6) |

A is the power law constant, which is a function of n, and x is the position along the Cartesian axis in physical space. The objects for this study were designed to maintain a constant width, w (fig. S8) to prevent the ability to discriminate between the objects based on overall width. The three objects used had a power law exponent, n, of ¼, ½, and 1 and were referred to as Object 1, Object 2, and Object 3, respectively. More details and explanation of power law shaped edges can be found in (40, 41).

Experimental design

Finger discrimination:

The multilayered e-dermis was placed over the thumb and pinky finger of the prosthesis. Activation of each fingertip sensor corresponded directly to nerve stimulation of the amputee in the corresponding sites of his phantom hand. The participant was seated, and his vision was occluded. The experimenter pressed either the prosthetic thumb, pinky, both, or neither in a random order. Each condition was presented 8 times. The stimulation amplitude was 1.5 mA and 1.45 mA for the thumb and pinky sites on the amputee’s residual limb, respectively. Next, the experimenter pressed the prosthetic thumb or pinky with either a light (< 100 kPa), medium (< 200 kPa), or hard (> 200 kPa) pressure (fig. S4 and S5). Each force condition was presented 10 times in a random order for each finger.

Object discrimination:

Fingertip sensors were placed on the thumb and index finger of a stationary bebionic™ prosthetic hand. The participant was seated, and his vision of the prosthesis was occluded. A stimulating electrode was placed over the region of his residual limb that corresponded to his thumb and index fingers on his phantom hand. The experimenter presented one of the 3 objects on the index finger of the prosthetic hand for several seconds. The participant responded with the perceived object as well as the perceived discomfort based on the tactile sensation. Each block consisted of up to 15 object presentations. The participant performed 3 blocks of this experiment. Each object was presented randomly within each block, and each object was presented the same number of times as the other objects. The participant visually inspected the individual objects before the experiment took place, but he was not given any sample stimulation of what each object would feel like. This was done to allow the participant to create his own expectation of perception of what each object should feel like if he were to receive sensory feedback on his phantom hand.

Pain Detection Task:

In the benchtop PDT, the prosthesis was mounted on a stand with the multilayered sensors on the thumb and index finger. The object was placed on a stand and the prosthesis grabbed the object using a closed precision pinch grip. Each object was presented to the prosthesis at least 15 times in a random order. For the user controlled PDT, the participant used his prosthesis to pick up and move one of the three objects. Each object was presented at least 10 times. The instances of prosthesis reflex were recorded. The participant took a survey at the end of the experiments (table S2).

Data collection

Each taxel of the multilayered e-dermis was connected to a voltage divider. Sensor data was collected by the customized prosthesis controller and sent through serial communication with a baud rate of 115,200 bps to MATLAB (MathWorks, USA) on a PC for further post-processing and plotting. Each sensing element in the e-dermis was sampled at 200 Hz. Responses from the psychophysical experiments were recorded using MATLAB and stored for processing and plotting. The prosthesis controller communicated with MATLAB through Bluetooth communication with a baud rate of 468,000 bps. 64 channel EEG data was recorded at 500 Hz by a SynAmp2 system (Neuroscan, UK) and processed in MATLAB using the EEGLab Toolbox (Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience, UC San Diego, USA). EEG data was downsampled to 256 Hz and band-pass filtered between 0.5 to 40 Hz using a 6th order Chebyshev filter. Muscle artifacts were rejected by the Automatic Artifact Rejection (AAR) blind source separation algorithm using canonical correlation approach. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was performed for removal of the eye and remnant muscle artifacts to obtain noise-free EEG data. Results from data collected over multiple trials of the same experiment were averaged together. Statistical p-values were calculated using a one-tailed, two-sample t-test. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean, unless otherwise specified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to sincerely thank the participant who volunteered and selflessly dedicated his time for this research to help enhance the current state of the art of prosthetic limb technology for the betterment of current and future users. The authors would like to thank Benjamin Skerritt-Davis for his help with the EEG experiment and Megan Hodgson for her support with the prosthesis controller and hardware.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Space@Hopkins funding initiative through Johns Hopkins University, the JHU Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) Graduate Fellowship Program, the Neuroengineering Training Initiative through the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering through the National Institutes of Health under grant T32EB003383.

Footnotes

Competing interests: L.E.O and N.V.T. are inventors on intellectual property regarding the multilayered e-dermis, which has been disclosed to Johns Hopkins University. N.V.T. is co-founder and R.R.K. is CEO of Infinite Biomedical Technologies. This relationship has been disclosed to and is managed by Johns Hopkins University. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Data and software code can be made available by materials transfer agreement upon reasonable request.

References and Notes

- 1.Abraira V, Ginty D, The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron 79, 618–639 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson RS, Flanagan JR, Coding and use of tactile signals from the fingertips in object manipulation tasks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 345–359 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallbo AB, Johansson RS, Properties of cutaneous mechanoreceptors in the human hand related to touch sensation. Hum. Neurobiol. 3, 3–14 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheibert J, Leurent S, Prevost A, Debregeas G, The role of fingerprints in the coding of tactile information probed with a biomimetic sensor. Science 323, 1503–1506 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pruszynski JA, Johansson RS, Edge-orientation processing in first-order tactile neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1404–1409 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ESJ, Lewin GR, Nociceptors: a phylogenetic view. J. Comp. Physiol. A. Neuroethol Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 195, 1089–1106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perl ER, Myelinated afferent fibres innervating the primate skin and their response to noxious stimuli. J. Physiol. 197, 593–615 (1968). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubin AE, Patapoutian A, Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3760–3772 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farina D, Vujaklija I, Sartori M, Kapelner T, Negro F, Jiang N, Bergmeister K, Andalib A, Principe J, Aszmann OC, Man/machine interface based on the discharge timings of spinal motor neurons after targeted muscle reinnervation. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 25 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DH, Ahn JH, Choi WM, Kim HS, Kim TH, Song J, Huang YY, Liu Z, Lu C, Rogers JA, Stretchable and foldable silicon integrated circuits. Science 320, 507–511 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Lee M, Shim HJ, Ghaffari R, Cho HR, Son D, Jung YH, Soh M, Choi C, Jung S, Chu K, Jeon D, Lee S, Kim JH, Choi SH, Hyeon T, Kim D, Stretchable silicon nanoribbon electronics for skin prosthesis. Nat. Commun. 5, 5747 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson C, Peele B, Li S, Robinson S, Totaro M, Beccai L, Mazzolai B, Shepherd R, Highly stretchable electroluminescent skin for optical signaling and tactile sensing. Science 351, 1071–1074 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C, Wang C, Keplinger C, Zuo J, Jin L, Sun Y, Zheng P, Cao Y, Lissel F, Linder C, You X, Bao Z, A highly stretchable autonomous self-healing elastomer. Nat. Chem. 8, 618–624 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tee BC, Wang C, Allen R, Bao Z, An electrically and mechanically self-healing composite with pressure-and flexion-sensitive properties for electronic skin applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 825–832 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou Z, Zhu C, Li Y, Lei X, Zhang W, Xiao J, Rehealable, fully recyclable, and malleable electronic skin enabled by dynamic covalent thermoset nanocomposite. Sci. Adv 4, eaaq0508 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tee BCK, Chortos A, Berndt A, Nguyen AK, Tom A, McGuire A, Lin ZC, Tien K, Bae W, Wang H, Mei P, Chou H, Cui B, Deisseroth K, Ng TN, Bao Z, A skin-inspired organic digital mechanoreceptor. Science 350, 313–316 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chun K, Son YJ, Jeon E, Lee S, Han C, A self-powered sensor mimicking slow-and fast-adapting cutaneous mechanoreceptors. Adv. Mater, 1706299 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao H, O’Brien K, Li S, Shepherd RF, Optoelectronically innervated soft prosthetic hand via stretchable optical waveguides. Sci. Robot 1, eaai7529 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborn L, Kaliki RR, Soares AB, Thakor NV, Neuromimetic event-based detection for closed-loop tactile feedback control of upper limb prostheses. IEEE Trans. Haptics 9, 196–206 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graczyk EL, Schiefer MA, Saal HP, Delhaye BP, Bensmaia SJ, Tyler DJ, The neural basis of perceived intensity in natural and artificial touch. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 362ra142 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raspopovic S, Capogrosso M, Petrini FM, Bonizzato M, Rigosa J, Di Pino G, Carpaneto J, Controzzi M, Boretius T, Fernandez E, Granata G, Oddo CM, Citi L, Ciancio AL, Cipriani C, Carrozza MC, Jensen W, Guglielmelli E, Stieglitz T, Rossini PM, Micera S, Restoring natural sensory feedback in real-time bidirectional hand prostheses. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 222ra19 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan DW, Schiefer MA, Keith MW, Anderson JR, Tyler J, Tyler DJ, A neural interface provides long-term stable natural touch perception. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 257ra138 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wendelken S, Page DM, Davis T, Wark HAC, Kluger DT, Duncan C, Warren DJ, Hutchinson DT, Clark GA, Restoration of motor control and proprioceptive and cutaneous sensation in humans with prior upper-limb amputation via multiple Utah Slanted Electrode Arrays (USEAs) implanted in residual peripheral arm nerves. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 14, 121 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborn L, Fifer M, Moran C, Betthauser J, Armiger R, Kaliki R and Thakor N. Targeted transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for phantom limb sensory feedback, Conf. Proc. IEEE Biomed. Circuits Syst. (BioCAS) (2017) 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saal HP, Delhaye BP, Rayhaun BC, Bensmaia SJ, Simulating tactile signals from the whole hand with millisecond precision. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E5702 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oddo CM, Raspopovic S, Artoni F, Mazzoni A, Spigler G, Petrini F, Giambattistelli F, Vecchio F, Miraglia F, Zollo L, Di Pino G, Camboni D, Carrozza MC, Guglielmelli E, Rossini PM, Faraguna U, Micera S, Intraneural stimulation elicits discrimination of textural features by artificial fingertip in intact and amputee humans. eLife 5, e09148 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osborn L, Nguyen H, Kaliki R and Thakor N. Prosthesis grip force modulation using neuromorphic tactile sensing, Proc. Myoelec. Controls Symp. (2017) 188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skljarevski V, Ramadan NM, The nociceptive flexion reflex in humans – review article. Pain 96, 3–8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bussel B, Roby-Brami A, Azouvi P, Biraben A, Yakovleff A, Held JP, Myoclonus in a patient with spinal cord transection. Possible involvement of the spinal stepping generator. Brain 111, 1235–1245 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ, Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J. Pain 10, 895–926 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chai G, Sui X, Li S, He L, Lan N, Characterization of evoked tactile sensation in forearm amputees with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. J. Neural Eng. 12, 066002 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schalk G, Mellinger J, Brain sensors and signals, in A Practical Guide to Brain–Computer Interfacing with BCI2000, Schalk G, Mellinger J, Eds. (Springer, London, 2010), pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izhikevich EM, Simple model of spiking neurons. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 14, 1569–1572 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terryn S, Brancart J, Lefeber D, Van Assche G, Vanderborght B, Self-healing soft pneumatic robots. Sci. Robot 2, eaan4268 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damian DD, Arita AH, Martinez H, Pfeifer R, Slip speed feedback for grip force control. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 59, 2200–2210 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartley C, Duff EP, Green G, Mellado GS, Worley A, Rogers R, Slater R, Nociceptive brain activity as a measure of analgesic efficacy in infants. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaah6122 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborn L, Lee WW, Kaliki R and Thakor N. Tactile feedback in upper limb prosthetic devices using flexible textile force sensors, Conf. Proc. IEEE Biomed. Robot. Biomechatron. (BioRob) (2014) 114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mancini F, Sambo C, Ramirez J, Bennett DH, Haggard P, Iannetti G, A fovea for pain at the fingertips. Curr. Biol. 23, 496–500 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrao M, Pierelli F, Don R, Ranavolo A, Cacchio A, Currà A, Sandrini G, Frascarelli M, Santilli V, Kinematic and electromyographic study of the nociceptive withdrawal reflex in the upper limbs during rest and movement. J. Neurosci. 26, 3505–3513 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santos WFN, Lewis MJ, Aerothermodynamic performance analysis of hypersonic flow on power law leading edges. J. Spacecr. Rockets 42, 588–597 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos WF, Lewis MJ, Power-law shaped leading edges in rarefied hypersonic flow. J. Spacecr. Rockets 39, 917–925 (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.