Abstract

Indigenous populations in Latin America are central to regional and global efforts toward achieving socially and environmentally sustainable development. However, existing demographic research on indigenous forest peoples (IFPs) has many limitations, including a lack of comparable cross-national evidence. We address this gap by linking representative census microdata to satellite-derived tree cover estimates for nine countries in the region. Our analyses describe the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of IFPs, and draw comparisons with reference groups. Our first goal is to examine within- and between-population variation in the age structure, human capital attainment, and economic status of IFPs. We then analyze patterns of fertility among indigenous forest-dwelling women and comparison groups. Finally, we examine the association between migration patterns and tree cover among indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Findings demonstrate that Latin America’s IFPs are materially deprived and characterized by high fertility levels overall. Importantly for sustainable development efforts, we show that non-indigenous forest-dwellers outnumber IFPs by more than eight to one and that IFPs have lower fertility than their non-indigenous counterparts when other characteristics are accounted for. Additionally, we find that most in-migrants to heavily-forested areas are non-indigenous, and that in-migrants tend to settle in areas that are forested but have few indigenous inhabitants. These results provide new cross-national evidence on the state of IFPs in Latin America, and highlight the need to empower these groups in the face of growing social and environmental crises in the region.

Keywords: indigenous populations, Latin America, forests, sustainable development, demography

1. Introduction

Indigenous forest peoples (IFPs) occupy a central role in global efforts toward achieving socially and environmentally sustainable development (Peña 2005; McNeil 2006). While their global populations are estimated to be small (Hall & Patrinos 2012), they are nonetheless the guardians of a large fraction of the world’s intact forests and speak a large fraction of the world’s endangered languages (Loh & Harmon 2014; Garnett et al. 2018). They are also among the world’s poorest peoples and have consistently been denied access to state services and political representation (Hall & Patrinos 2012), while at the same time being involuntarily exposed to the social and environmental externalities of natural resource extraction and agricultural colonization (Reyes-García et al. 2012; O’Faircheallaigh 2013). This latter set of issues is particularly salient in Latin America, where the world’s largest reservoir of tropical biodiversity is watched over by a large number of threatened, numerically-small, and culturally-distinct indigenous populations (Montenegro & Stephens 2006; Finer et al. 2008).

For all these reasons, there is a fundamental need to document and understand the situation of IFPs, who we define as (self-identified) original peoples inhabiting densely-forested areas. To date, however, our knowledge of these populations comes primarily from a large but disparate collection of small-scale studies whose output is empirically rich but quite difficult to aggregate and compare across contexts (McSweeney & Arps 2005), undermining claims about the regional status of these peoples. Alternatively, a small number of studies have collected comparable social data on multiple ethnically-distinct populations (Bremner et al. 2009; Coimbra et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2015; Coomes et al. 2016; Davis et al. 2017), but their regional and national coverage remains limited. Finally, an additional set of studies has used satellite imagery to describe forest cover dynamics in indigenous territories (Nepstad et al. 2006; Nolte et al. 2013; Blackman et al. 2017). However, these formally-designated territories do not encompass all indigenous lands, and analysis of such remotely-sensed data tells us very little about the peoples who are responsible for the observed outcomes. Approaches that produce generalizable knowledge about the social and demographic conditions of indigenous forest peoples are therefore much needed to inform national and regional policymaking.

To address this lacuna, we produce a new demographic portrait of IFPs across nine Latin American countries. Specifically, we access individual-level census data containing measures of indigeneity from Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, and link these records to contemporaneous satellite-derived data on tree cover at the district level. This combined dataset allows us to define a large sample of IFPs (202,198 individuals) that is representative of a population of more than 2.4 million. The major goals of our analyses are to measure the socio-demographic characteristics of the indigenous forest-dwelling population and compare them to the characteristics of non-forest-dwelling and non-indigenous reference groups, describe variation in population characteristics across key sub-populations (e.g., by country and ethno-linguistic group), and investigate the correlates of fertility and migration among these populations.

This analysis confirms that the IFPs of Latin America are materially deprived and at early stages of the demographic transition, particularly in Amazonian countries.1 Additionally, while our study does not directly examine the relationship between demographic and environmental change, a number of our findings have direct relevance for forest conservation. First, we show that non-indigenous populations outnumber members of indigenous groups in heavily-forested districts by more than eight to one. Second, we find that most in-migrants to forested areas are non-indigenous, and non-indigenous migrants are most likely to settle in districts with high forest cover but relatively small indigenous populations. Third and finally, results reveal that separate from other socio-demographic characteristics, indigeneity is itself associated with reduced fertility, and thus generally slower population growth, among forest peoples. These and other results provide new cross-national evidence about the conditions of IFPs in the Americas. Among other policy implications, our findings support calls for greater political recognition and state support for indigenous forest peoples, and in particular point to the need for expanded investments in education and health services for IFPs.

2. Population and environment dynamics among indigenous populations in Latin America

Our study is motivated by two areas of research that have been insufficiently integrated to date: the literature on indigenous environmental behavior and land use, and the literature on indigenous demography and population change (McSweeney 2005). Research on indigenous environmental behavior and land use consistently shows that forest-dwelling indigenous peoples have lower environmental impacts than non-indigenous peoples living in the same areas. For example, several studies using satellite imagery have shown that indigenous territories have lower rates of deforestation and forest degradation than equivalent areas outside of such territories (Asner et al. 2005; Nepstad et al. 2006; Adeney et al. 2009; Nolte et al. 2013; Holland et al. 2014; Blackman et al. 2017), in part because indigenous peoples defend their land from agricultural colonization. These results are consistent with numerous small-scale studies documenting that indigenous forest use—including hunting, fishing, gathering of forest products and swidden agriculture—can be ecologically sustainable at low population densities (Lu 2001; Sirén 2007; Levi 2009).

At the same time, we must avoid essentializing IFPs as “forest defenders” and acknowledge the very real impacts that their land uses can have on local biodiversity. For example, indigenous people hunting with shotguns can drive large-bodied species into local extinction (Levi 2009). Many, if not most, IFPs occupy forest frontiers where they come into regular contact with agricultural colonists, external markets, and extraction activities focused on minerals or forest products (Lu 2007; Gray et al. 2015). (In some cases, the agricultural colonists are other indigenous peoples who have resettled from upland or other lowland areas (Rudel et al. 2013)—and who would be considered IFPs in our definition.). In many places these processes have a long history, resulting in the displacement of IFPs, continual encroachment on their historical lands, and, during the colonial era, slavery and genocide (Erazo 2013). Only recently have governments began to recognize IFPs’ territorial and political rights, though typically on a small fraction of the land these groups historically occupied and only after a long political struggle (Sawyer 2004; Nancy & Zamosc 2005; Lu et al. 2016)

In this context, some indigenous peoples have adopted settlement patterns and agricultural systems that represent a hybrid of traditional practices and those of more destructive, non-indigenous colonists (Rudel et al. 2002; Gray et al. 2008). Nonetheless, in most contexts forest-dwelling indigenous populations remain culturally and spatially distinct from local non-indigenous populations, and their land uses also remain distinct from the practices of non-indigenous populations that often include commercial agriculture and cattle ranching (Lu et al. 2010). These differences support a continued role for IFPs as environmental stewards in the biologically-rich forests of Latin America. These findings also undermine neo-Malthusian assumptions that population growth among IFPs is linearly associated with environmental degradation, and in fact suggest that the support of IFP populations may have both social and ecological benefits.

The second literature that we build on has used demographic data and methods to describe the health, fertility, and migration of IFPs, usually for one local population at a time. These studies have consistently shown that forest-dwelling indigenous populations are materially deprived and have higher rates of fertility and mortality than national or non-indigenous populations (Pagliaro et al. 2007; Pagliaro 2010; Jokisch & McSweeney 2011; Souza et al. 2011; Teixeira et al. 2011; Mcallister et al. 2012; Lanza et al. 2013). These population characteristics reflect IFPs’ history of isolation, exclusion from government services, and their position in early stages of the demographic transition. McSweeney and Arps (2005) made an important effort to aggregate results that had been published from 25 such studies, and their findings revealed that lowland indigenous populations had high fertility and young age structures relative to rural and national comparison groups. However, these and other small-scale studies have not used consistent methodologies, are not representative of IFPs, and have collected very little information about indigenous migration and population mobility (McSweeney & Jokisch 2007).

A limited number of studies have used consistent methods to measure demographic processes across distinct forest-dwelling indigenous groups within single-country contexts. For example, Davis and colleagues (2015; 2017) describe the collection of longitudinal household data from five such groups in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Analyses of these data have revealed high but falling fertility in these populations alongside low but rising use of contraception (Bremner et al. 2009; Davis et al. 2015). This research has also found high rates of internal migration, primarily to rural destinations (Davis et al. 2017). In another case, Coimbra et al. (2013) describe a large cross-sectional survey of indigenous peoples in Brazil, which drew a sample from 60 villages in the heavily-forested Northern region. This study’s findings included evidence that indigenous households had low levels of assets and infrastructure access and high level of child undernourishment. These studies represent an important advance over site-specific research, but it would be very difficult to scale up this intensive approach by fielding new household surveys of indigenous peoples across multiple countries. To our knowledge, such an effort has not been attempted.

Census data represent an alternative to site-specific household surveys, with the advantage that they cover the entire national population. Access to individual-level census data has expanded dramatically with the advent of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series-International project (IPUMS-International, Minnesota Population Center 2015), and the identification of indigenous populations has improved as many Latin American censuses since 2000 have asked a question about indigeneity and/or languages spoken (Schkolnik & Del Popolo 2013). Inclusion of such questions has allowed several analyses of the situation of Latin American indigenous peoples broadly, highlighting their material deprivation and exclusion from economic opportunity (Perz et al. 2008; Hall & Patrinos 2012; Ñopo 2012; Anderson et al. 2016; World Bank 2015; Longo et al. 2016; Del Popolo 2017; Reimão & Taş 2017). Two studies have specifically investigated the suitability of census data to describe IFPs. De Oliveira Martins Pereira and colleagues (2009) compared census data for the Xavante territory with independently-collected demographic data, finding that indigenous forms of household organization were not fully captured but that estimates of the population count and composition were accurate. Santos et al. (2015) analyzed data from the 2010 census of Brazil to reveal that parity under-reporting was slightly higher for indigenous women when the interviewee was not a household member, but these cases represent only 13 percent of the indigenous population in the Northern region. Census data have known limitations for studying indigenous peoples that we describe below, but these studies suggest that that such data can also add considerable value relative to the limited regional-scale knowledge we currently have about IFPs.

With this in mind, in the current study we take advantage of newly-accessible census records to provide the first consistent and representative cross-national description of IFPs in Latin America. By linking individual-level census data to district-level estimates of tree cover, we address two broad questions. First, how do IFPs differ from other forest peoples, as well as indigenous and non-indigenous populations outside of heavily-forested districts? Second, how do processes of fertility and migration compare across indigenous and non-indigenous groups and between forest districts and other parts of the region? As described below, these analyses provide new insights into the distinctiveness of IFPs and their demographic futures in a region undergoing rapid social and environmental change.

3. Research focus

The overall goal of this paper is to describe population characteristics, and patterns therein, among Latin American IFPs during the 2000s. We place particular focus on patterns of fertility and migration since these processes drive population growth (and decline) and are therefore central to the size and geographic distribution of the region’s IFPs. Taking a comparative approach across countries and groups, we address the following specific aims. First, we describe the overall characteristics of IFPs across the countries in our sample. We draw comparisons with non-indigenous forest-dwellers and both indigenous and non-indigenous populations outside of heavily-forested areas. Second, we describe variation in the population characteristics of IFPs among the nine countries in our sample, and provide demographic and socioeconomic profiles of specific indigenous groups within these countries. Then, in the final two steps we focus on levels and patterns of fertility and migration, which are of particular interest since they drive population growth and the relative size of IFP populations in the heavily-forested districts of interest. Specifically, our third aim is to analyze levels of fertility among reproductive-aged women in the region, comparing IFPs with other groups and analyzing correlates of fertility differentials among IFPs. Our fourth and final aim is to examine patterns of migration across the region. Here, our goal is to understand whether recent long-distance in-migrants are over- or under-represented in heavily-forested districts, and if these patterns vary between indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Overall, our attention to cross-national and within-indigenous population variation offers new insights into the “demographic turnaround” among Latin America’s indigenous populations (McSweeney & Arps 2005).

4. Material and methods

4.1. Data and measures

We draw on demographic microdata from national censuses, which we extract from the IPUMS-International database (Minnesota Population Center 2015). We restrict our analytic sample to Latin American countries that implemented censuses or comparable household surveys between 2000 and 2009, that collected the information necessary to identify members of indigenous groups and migrants at a five-year interval, and that had IPUMS-standardized geographic identifiers and shapefiles available for second-order subnational administrative units. We focus on the 2000–2009 period since harmonized data from Latin American censuses conducted in 2010 and later have, to date, not been collected or released for many countries of interest (including Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela). We do not include post-2009 data from the few countries for which it is available to ensure the census data were collected within a decade of the year-2000 measures of tree cover used to identify forest dwellers (see below).

We are particularly interested in describing demographic patterns among IFPs. We classify individuals as indigenous using a binary indicator of indigenous group membership, which for most countries is derived from data on self-reported race or ethnicity. For Peru, however, we classify indigenous status according to whether individuals reported speaking an indigenous language or not since comparable data on ethnicity were not collected. The measurement of indigeneity is contested (Yoshioka 2010), as are many similar measures of socially-constructed identities.2 The approach we take may be limited by individuals’ reluctance to identify as indigenous to census enumerators (Montenegro & Stephens 2006), who represent the federal governments with which many indigenous groups have had tenuous (at best) relationships. Likewise, individuals of indigenous origin and identity may not speak (or may deny speaking) an indigenous language (Skoufias et al. 2009). Censuses and surveys are most likely to undercount indigenous populations in either case, though in some cases resurgences in indigenous identity may lead to upward shifts in estimates (Perz et al. 2008). There is no agreed-upon solution to these challenges (Yoshioka 2010), but we test the sensitivity of our main findings by replicating select analyses using a language- rather than ethnicity-based definition of indigeneity for the six countries in our sample that collected both sets of information.3 The results are presented in Tables A6 and A7 of the appendix.

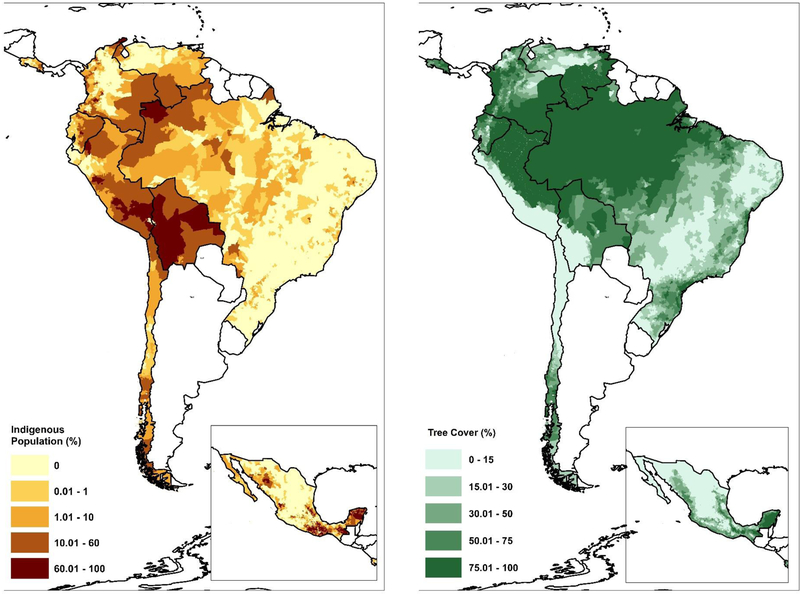

For reference, we have provided estimates of the indigenous population share across our sample (Figure 1, left panel) at the second-order subnational level, which we refer to as the district level. We also measure membership in specific ethno-linguistic groups for parts of our analysis, drawing on the most detailed information available in each census. In some cases, this information on group membership is based on a different census question (e.g., language spoken) than the information used to identify indigenous status in the overall analyses (e.g., race or ethnicity). As a result, some individuals who are identified as indigenous in the global measure of indigenous status lack the information required to identify group membership and are therefore excluded from these more detailed analyses. These discrepancies are relatively minor and documented in the pertinent tables.

Figure 1.

District-level indigenous population share (left) and tree cover (right)

To identify forest-dwelling populations, we map and analyze year-2000 forest cover at the district level. We use tree cover estimates from the University of Maryland’s Global Forest Change database (Hansen et al. 2013), and district shapefiles produced by IPUMS-International. These tree cover estimates are derived from 30-meter resolution earth observation satellite data for the year 2000. We use these estimates to calculate the share of each district’s territory under tree cover (Figure 1, right panel). We then identify districts with tree cover of 75 percent or more and classify their residents as forest-dwelling.4 Using this threshold, individuals defined as forest-dwelling fall within the upper tails of both the district and population distributions with respect to tree cover. Only 8.5 percent of the districts included in our dataset have tree cover of 75 percent or more and 5.4 percent of individuals in the entire population reside in these heavily-forested districts. Likewise, just over one-eighth (13.1%) of the total indigenous population is defined as being forest-dwelling according to this approach. So defined, heavily-forested districts are identified by the darkest shade of green in the map on the right-most panel of Figure 1, and closely correspond to the locations of previously-identified intact forest landscapes (Myers et al. 2000) and IFPs. As one specific validation, we identified districts (cantons) in Ecuador that are home to IFPs identified in previous research (Gray et al. 2015; Davis et al. 2017) and confirmed that these areas were correctly classified as highly forested in the current study. We also test the sensitivity of our regression analysis to defining districts as heavily forested if the area under tree cover was 90 percent or more, and include results in Tables A6 and A8 of the appendix.5

We examine two analytic samples during our descriptive analysis. First, we analyze records of all individuals, regardless of age, to describe key characteristics of the overall indigenous forest population and reference groups. Note that in two countries—Bolivia and Mexico—the indigenous status of children is not collected, and for these sub-populations we assign group membership according to the status of the household head. Second, we conduct additional analyses of adults, defined as individuals aged 15 years and older, which focus on human capital and labor force characteristics. The overall sample of all individuals includes 32,023,785 unweighted observations, of which approximately 4.8 percent is identified as indigenous; and our sample of adults ages 15+ years includes 21,310,604 unweighted observations, with 4.4 percent identified as indigenous. We utilize the sample of adults for our migration analysis. Our study of fertility patterns is further restricted to women ages 15–49 years, which corresponds to the conventional definition of reproductive age. Although some data on previous fertility was also collected for women at older ages, we omit these observations since selective mortality patterns among members of these age groups may bias estimates (Montenegro & Stephens 2006; Perreira & Telles 2014). Throughout our analyses, we weight observations by the inverse probability of selection into the IPUMS sample, which includes between 6.0 and 10.6 percent of the national populations.

4.2. Analytic strategy

We address the research objectives outlined above through a four-step analysis. First, we describe the characteristics of IFPs. While we are particularly interested in fertility and migration, we seek to produce the fullest-possible profile of IFPs in Latin America and therefore also describe this population’s age structure, economic status, and, among adults, educational attainment and family structure.6 We choose this set of characteristics because they capture many domains of life and can be measured consistently across the censuses included in our sample. Interpretations should nonetheless be made with caution given cultural differences among IFPs (as well as between indigenous and non-indigenous populations), such as the types of dwellings that are normative, the meaning of marriage, and how employment status is understood in subsistence-oriented societies versus other contexts. Second, we draw a series of comparisons: We begin by comparing the characteristics of IFPs with the non-indigenous population in the same highly-forested districts, as well as with indigenous and non-indigenous populations living in other districts. We then draw comparisons within the forest-dwelling indigenous population, focusing on differences between countries and among ethno-linguistic groups within countries to account for the distinctive socioeconomic and demographic conditions of the many culturally-distinct IFP groups in our sample.

Third, we analyze fertility levels among women ages 15–49 by estimating two regression models that predict the number of children ever born to each woman. We employ Poisson regression since the outcome variable is constrained to non-negative integers and positively skewed (i.e., high values, such as ≥7, are rare). In our first model, we pool all observations and estimate differences between indigenous forest-dwelling populations, non-indigenous forest-dwellers, and both indigenous and non-indigenous non-forest dwellers. This model controls for age (modeled as a quadratic function), educational attainment, marital status, rural versus urban residence, and country of residence. We estimate the second model among a sample of only forest-dwelling indigenous women, and include the predictor variables listed above to identify the social and geographic sources of variation in fertility levels within this population. Note that we do not examine other fertility outcomes of potential interest, such as births in the past year, since the data needed to calculate these alternative measures are not available for all samples.

Fourth and finally, we analyze patterns of long-distance migration into heavily-forested districts (so defined) among indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Here, we conduct aggregated, district-level analyses and estimate linear regression models predicting the number of long-distance in-migrants per 100 of the total district population aged 15 years and above (henceforth “in-migration rate”). Reflecting the best-available migration measures in the census data we analyze, we define in-migrants as individuals whose level-one subnational unit (e.g., province) of residence five years prior to the census differed from their place of residence at the time of the census. As such, our outcome variable can be interpreted as the share of a given district’s population that migrated from another province within the past five years. Given this definition, we expect our analyses to result in conservative estimates of migration since this measure excludes individuals who moved from other districts within the same province or relocated within district boundaries.

We analyze district in-migration rates for indigenous and non-indigenous populations separately. For each group, we estimate a linear regression model of the in-migration rate as a function of whether the district is heavily-forested (as defined above), non-migrant population size, district median age, land area, country, and the respective proportions of the district’s population that is indigenous, has at least a primary school education, is married, and lives in a rural area. These models allow us to assess whether the representation of in-migrants from each group varies systematically between heavily-forested districts and other places irrespective of other district-level factors that may be correlated with in-migration rates. To ensure our results are not being driven by the threshold used to define heavily-forested districts, we estimate an alternative specification in which we treat tree cover as a continuous variable and include it in the model as a quadratic function. Finally, for each group we estimate an additional model of in-migration rates among only heavily-forested districts and examine variation in these rates across the other social and geographic predictors in the model. Using these models, we identify the district characteristics associated with the concentration of long-distance in-migrants within heavily-forested regions of Latin America.

5. Results

5.1. Population characteristics by indigenous and forest-dwelling status

We begin by describing the overall characteristics of the indigenous forest populations captured in our sample and drawing comparisons with non-indigenous forest-dwellers and both indigenous and non-indigenous populations in less-forested districts (Table 1). For each group of interest, we describe the age structure and economic characteristics of the entire population (upper panel), and patterns of educational attainment, marriage and other unions, employment, and migration among adults ages 15 years and older (lower panel). Note that we conducted statistical tests of between-group differences in the means and distributions of the variables of interest with reference to IFPs. All differences were statistically significant at conventional thresholds.

Table 1.

Demographic and economic characteristics, by indigenous and forest-dwelling status

| Variable | Indigenous, forest-dweller | Non-indigenous, forest-dweller | Indigenous, not forest-dweller | Non-indigenous, not forest-dweller | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous individuals | |||||||

| Age 0–14 | 42.84% | 37.37% | *** | 36.81% | *** | 31.18% | *** |

| Age 65+ | 4.22% | 4.35% | ** | 6.82% | *** | 5.67% | *** |

| Sex = female | 48.17% | 49.16% | *** | 49.97% | *** | 50.83% | *** |

| Household size | 6.02 | 5.51 | *** | 5.38 | *** | 4.86 | *** |

| Number of children age <5 in household | 0.27 | 0.20 | *** | 0.22 | *** | 0.17 | *** |

| Place of residence = rural | 70.21% | 33.31% | *** | 52.58% | *** | 18.78% | *** |

| Number of rooms in housing unit | 2.46 | 3.95 | *** | 2.81 | *** | 4.54 | *** |

| Electricity access = yes | 55.71% | 80.25% | *** | 69.26% | *** | 94.45% | *** |

| Access to water supply = yes | 51.51% | 67.04% | *** | 63.19% | *** | 88.29% | *** |

| Phone access = yes | 3.85% | 23.79% | *** | 13.06% | *** | 40.34% | *** |

| Share of total sample | 0.63% | 5.28% | 4.19% | 89.90% | |||

| N (weighted) | 2,437,696 | 20,386,573 | 16,165,274 | 347,088,350 | |||

| N (unweighted) | 202,198 | 1,690,994 | 1,340,852 | 28,789,741 | |||

| Indigenous adults (age 15+) | |||||||

| Educational attainment = primary school+ | 43.31% | 53.71% | *** | 51.19% | *** | 64.27% | *** |

| Marital status | *** | *** | *** | ||||

| Single, never married | 26.28% | 30.80% | 26.17% | 31.47% | |||

| Married or in union | 66.22% | 58.35% | 63.69% | 57.14% | |||

| Separated, divorced, or spouse absent | 2.87% | 7.29% | 3.60% | 6.80% | |||

| Widowed | 4.63% | 3.56% | 6.55% | 4.59% | |||

| Employment status | *** | *** | *** | ||||

| Employed | 57.05% | 51.94% | 52.24% | 52.83% | |||

| Unemployed | 1.25% | 6.08% | 2.60% | 5.77% | |||

| Inactive | 41.70% | 41.98% | 45.16% | 41.41% | |||

| Inter-province migration within 5 years = yes | 3.77% | 6.18% | *** | 5.29% | *** | 4.84% | *** |

| Share of total sample | 0.53% | 4.85% | 3.88% | 90.74% | |||

| N (weighted) | 1,393,363 | 12,768,298 | 10,215,291 | 238,849,472 | |||

| N (unweighted) | 112,806 | 1,033,711 | 827,022 | 19,337,065 | |||

Note: Means and percentages reported.

p<0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

Tests of differences in means and proportions conducted with reference to indigenous forest-dwellers. Results of χ2 tests reported for categorical variables. The universe for indigenous status is restricted to persons age 15+ in Bolivia and persons age 5+ in Mexico. For those outside of this universe, we apply the indigenous status of the household head.

Across the countries in our sample, IFPs are distinctively younger than non-indigenous populations and indigenous populations outside of heavily-forested areas. A full 42.8 percent of all IFPs are less than 15 years old, compared with 37.4 percent of the non-indigenous populations in heavily-forested districts and 36.8 percent of indigenous populations in other parts of the region. The relatively young age structure of the IFP population is suggestive of high fertility rates, and points to a high demand for investments in education, child health, and related resources for children and youth. On the other hand, IFPs have the lowest population share aged 65 years and older (4.2%) among the four groups considered here. This figure is followed closely by the older-adult share of non-indigenous forest-dwellers (4.3%), while between 5.7 and 6.8 percent of the population outside of heavily-forested districts is aged 65 or older. The relatively low share of older adults in heavily-forested districts irrespective of indigenous status is notable and may reflect a combination of age-specific migration patterns and high adult mortality in heavily-forested districts. The sex composition of these four populations is consistent with their age structure, since younger populations tend to have a higher ratio of males to females. Men are over-represented among the region’s IFPs (51.8%) relative to others, although they also comprise a majority (50.8%) of the non-indigenous population in heavily-forested districts.

Demographic differences among populations also manifest in patterns of household living arrangements. The average member of the indigenous forest population resides in a larger household (6.0 persons) than their non-indigenous forest-dwelling counterparts (5.5 persons) or members of both the indigenous (5.4 persons) and non-indigenous (4.9 persons) populations in other districts. The households of IFPs also include the largest number of children under the age of five (0.27 children), on average, relative to the three comparison groups of interest. The average member of these other groups resides in a household with between 0.17 and 0.22 young children, so defined. Taken together, these results are consistent with IFPs being at an early stage of the demographic transition with high fertility and a corresponding young age structure (McSweeney & Arps 2005).

The material living standards of IFPs are also, on average, lowest among the four groups of interest, although we observe broader indigenous versus non-indigenous differences in this set of outcomes. For example, the average member of the indigenous forest population resides in a house with 2.5 rooms, which is considerably smaller than the 4.0- to 4.5-room house of the average non-indigenous person but fairly close to the 2.8-room house of the average indigenous person living outside of heavily-forested districts. Of course, these differences in housing may not only reflect economic disparities but also culturally-specific norms about the types of dwellings that are preferred. We nonetheless observe a similar pattern with respect to electricity, water, and phone access. IFPs have the lowest levels of access to these services, followed by indigenous populations outside of heavily-forested districts, non-indigenous forest-dwellers, and non-indigenous non-forest-dwellers—who have the highest rates of service access. We also find that members of indigenous groups are considerably more likely to reside in rural settlements than their non-indigenous counterparts, and this is true in both heavily-forested districts and elsewhere. While more than two-thirds (70.2%) of IFPs reside in rural settlements, only 33.3 percent of the non-indigenous population in these districts does (a gap mirrored in less-forested districts). An implication is that among the heavily-forested districts we consider, indigenous populations are much more likely to reside in small settlements within the forest than in the urbanized settlements in those districts, where the majority of the non-indigenous population resides.

We also analyze key socioeconomic indicators among IFPs aged 15 years and older. Consistent with the patterns of asset ownership and infrastructure access described above, estimates of educational attainment reveal that indigenous forest populations are socioeconomically disadvantaged relative to other indigenous populations and the non-indigenous. Less than half of adult IFPs (43.3%) have completed primary school, which is nearly eight percentage points less than among indigenous adults outside of heavily-forested districts (51.2%) and more than ten percentage points less than non-indigenous forest-dwelling adults (53.7%). Educational disparities are even greater relative to non-forest-dwelling non-indigenous adults, of whom nearly two-thirds (64.3%) have completed primary school. These inequalities are particularly notable given that the IFPs are overrepresented among younger cohorts of adults, who grew up during a period of increasing emphasis on education in the region (UNESCO 2014). On the other hand, a relatively large share of IFPs—57.1 percent—is employed, and this level stands between 4.3 and 5.2 percentage points higher than comparison groups. Of course, the relatively low levels of indigenous forest asset ownership and educational attainment described above suggest that IFPs may be employed in low-skill and low-wage work or, more likely, subsistence activities that do not generally translate into improved material wellbeing as defined here. Taken together, these results indicate that IFPs are materially disadvantaged even relative to other disadvantaged groups such as non-indigenous forest dwellers and non-forest indigenous peoples.

Finally, we describe patterns of marital unions and migration among indigenous forest adults. The indigenous population in general—and IFPs in particular—have higher rates of marital unions than their non-indigenous counterparts. A full 66.2 percent of IFPs are married or in a union, as is 63.7 percent of the indigenous population in other districts. Divorce—at least as measured by the prevalence of divorcees—is also relatively rare among these two populations, at 2.9 and 3.6 percent, respectively. In contrast, 58.4 and 57.1 percent of the non-indigenous populations in forested and non-forested districts are, respectively, married, and the prevalence of (currently-single) divorcees ranges from 6.8 to 7.3 percent. These disparities in family structure are consistent with higher levels of fertility among the IFPs and other indigenous populations. They may also reflect differences in social norms that promote early entrance into marital unions, reduce the risk of divorce, or lead to notably different concepts of marriage among the populations we study.

Our estimates suggest that members of the indigenous forest population are not only more likely to be married, but also likely to remain in or near their place of residence. Less than four percent (3.8%) of IFPs had moved from another province during the five years preceding the censuses in our sample, which is at least one percentage point lower than the prevalence of migration among both indigenous (5.3%) and non-indigenous (4.8%) populations outside of heavily-forested districts. Consistent with their role in frontier settlement, non-indigenous forest-dwellers had the highest rate of migration at 6.2 percent. These results suggest that IFPs, in comparison to other populations, maintain traditional life-course patterns with high rates of marital unions and low levels of long-distance migration.

5.2. Characteristics of indigenous forest populations by country and ethno-linguistic group

We next examine variation in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics among IFP sub-populations, with a focus on cross-national differences (Table 2). We again describe the characteristics of both the overall population (top panel) and adults ages 15 years and older (bottom panel). We also discuss select differences in characteristics between specific indigenous groups within countries (Tables A1–A5). Given the extent of the latter group-specific analyses, we highlight only select findings where between-group differentials (or a lack thereof) are particularly notable. However, we provide readers with the full set of estimates in the appendix for their reference.

Table 2.

Demographic and economic characteristics of indigenous forest-dwelling population, by country

| Variable | Bolivia | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Costa Rica | Ecuador | Mexico | Peru | Venezuela |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous individuals | |||||||||

| Age 0–14 | 45.96% | 43.35% | 26.95% | 47.76% | 47.24% | 50.11% | 42.39% | 37.59% | 45.67% |

| Age 65+ | 3.95% | 3.66% | 8.90% | 3.78% | 2.98% | 2.52% | 4.42% | 4.71% | 2.99% |

| Sex = female | 45.44% | 48.21% | 47.19% | 48.82% | 47.64% | 48.92% | 48.56% | 48.30% | 50.91% |

| Household size | 5.69 | 6.76 | 4.49 | 5.61 | 6.16 | 7.14 | 6.09 | 5.68 | 6.34 |

| Number of children age <5 in household | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| Place of residence = rural | 71.77% | 77.78% | 61.88% | 80.97% | 88.49% | 72.58% | 62.23% | 83.60% | 26.52% |

| Number of rooms in housing unit | 2.11 | 2.99 | 4.44 | 2.68 | 3.46 | 2.14 | 2.60 | 1.80 | 2.92 |

| Electricity access = yes | 33.13% | 47.00% | 73.48% | 45.41% | 46.25% | 29.94% | 79.19% | 23.49% | 89.64% |

| Access to water supply = yes | 51.01% | 24.35% | 79.27% | 27.72% | 63.46% | 34.08% | 74.92% | 14.55% | 68.42% |

| Phone access = yes | 4.80% | 5.16% | 12.96% | 5.10% | 7.60% | 3.07% | 3.39% | 1.54% | 15.76% |

| Share of country’s total population | 3.67% | 0.10% | 0.26% | 0.53% | 0.87% | 1.28% | 1.19% | 1.59% | 0.15% |

| N (weighted) | 284,660 | 171,419 | 36,960 | 206,418 | 32,240 | 147,350 | 1,105,338 | 420,890 | 32,430 |

| N (unweighted) | 28,466 | 10,188 | 3,696 | 40,182 | 3,224 | 14,735 | 184,889 | 42,089 | 3,243 |

| Indigenous adults (age 15+) | |||||||||

| Educational attainment = primary school+ | 53.07% | 17.57% | 57.63% | 40.97% | 41.56% | 53.50% | 42.82% | 44.09% | 57.43% |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single, never married | 26.95% | 25.15% | 38.15% | 32.12% | 26.04% | 27.34% | 27.62% | 18.44% | 37.00% |

| Married or in union | 65.39% | 63.69% | 53.00% | 61.08% | 67.08% | 67.72% | 65.63% | 72.73% | 56.02% |

| Separated, divorced, or spouse absent | 2.54% | 7.89% | 3.33% | 2.47% | 4.29% | 1.99% | 2.04% | 3.46% | 3.58% |

| Widowed | 5.13% | 3.27% | 5.52% | 4.33% | 2.59% | 2.95% | 4.71% | 5.37% | 3.41% |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Employed | 67.05% | 48.95% | 35.89% | 46.18% | 53.15% | 64.75% | 57.54% | 58.85% | 40.58% |

| Unemployed | 1.07% | 4.72% | 7.63% | 1.54% | 2.00% | 0.99% | 0.33% | 1.37% | 3.75% |

| Inactive | 31.88% | 46.33% | 56.48% | 52.27% | 44.86% | 34.25% | 42.13% | 39.78% | 55.68% |

| Inter-province migration within 5 years = yes | 7.16% | 1.69% | 9.81% | 1.12% | 12.82% | 5.56% | 2.56% | 5.01% | 1.93% |

| Share of country’s total population | 3.35% | 0.08% | 0.26% | 0.40% | 0.68% | 0.98% | 1.06% | 1.45% | 0.12% |

| N (weighted) | 153,830 | 97,103 | 27,000 | 107,828 | 17,010 | 73,510 | 636,780 | 262,690 | 17,620 |

| N (unweighted) | 15,383 | 5,627 | 2,700 | 20,387 | 1,701 | 7,351 | 106,498 | 26,269 | 1,762 |

Note: Means and percentages reported. The universe for indigenous status is restricted to persons age 15+ in Bolivia and persons age 5+ in Mexico. For those outside of this universe, we apply the indigenous status of the household head.

A first and fundamental finding from these cross-national estimates is that the size and representation of IFPs vary markedly across the region. In terms of overall population size, the IFPs range from a low of approximately 32,000 in Costa Rica (32,240) and Venezuela (32,430) to a high of 1,105,338 in Mexico. Proportionately, IFPs constitute the smallest share of the national population in Brazil (0.1%) and the largest in Bolivia (3.7%). We also observe a number of notable differences in the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of indigenous forest-dwellers across countries, which in many cases are consistent with cross-national patterns of social and economic conditions. For example, IFPs in Chile—one of the most developed countries in the region—are much older (26.9% age 0–14; 8.9% age 65+) and, on average, live in larger houses (4.4 rooms) with smaller households (4.5 persons) than comparable populations elsewhere in the region. In Ecuador, for instance, more than half (50.1%) of IFPs are under the age of 15, and the average IFP resides in a household of 7.1 persons and house of only 2.1 rooms, indicating high rates of fertility and low material living standards.

Rates of access to basic infrastructure provide additional insight into economic conditions among IFPs. Our findings suggest that the forest-dwelling indigenous populations in Chile, Mexico, and Venezuela are distinctively better-off than others, if still disadvantaged in an absolute sense. For example, the average member of the small population of indigenous forest-dwellers in Venezuela lives in a house with nearly three (2.9) rooms, and 89.6 and 68.4 percent of this population has access to electricity and water, respectively. Likewise, approximately three-quarters of indigenous forest-dwellers in Mexico have access to electricity (79.2%) and water (74.9%), and the average Mexican IFP’s house has 2.6 rooms. Conversely, the results also point to countries in which the indigenous forest-dwelling population is markedly worse-off. In Peru, for example, the average IFP lives in a house with 1.8 rooms—the smallest average dwelling size across our sample—and 5.7 household members; and rates of access to electricity (23.5%) and water (14.5 percent) are far lower than most other countries (except Ecuador where asset ownership is also low). These findings underscore the variation in living conditions among IFPs across the region. While some of this variation may reflect group-specific preferences (e.g., regarding dwelling types), disparities in access to water and other critical resources are likely to reflect inequality in material living standards.

With respect to the characteristics of indigenous forest-dwelling adults, our estimates reveal wide variation in educational attainment, marital status, employment, and inter-province migration rates. Levels of primary school completion vary from an exceptionally-low 17.6 percent in Brazil to over 57 percent in both Chile (57.6%) and Venezuela (57.4%). Primary school completion rates among the IFPs in a number of other countries—such as Colombia (41.0%), Costa Rica (41.6 %), Mexico (42.8%), and Peru (44.1%)—are not as low as Brazil but remain well below 50 percent. Such poor educational outcomes suggest that many among the next generation of IFPs will face barriers to attaining welfare-enhancing social and economic resources unless changes occur that rapidly improve outcomes for incoming cohorts of students. Relatedly, employment and labor force participation rates range widely across the countries in our sample, with between 35.9 percent (Chile) and 67.1 percent (Bolivia) classified as employed; between 0.3 percent (Mexico) and 7.6 percent (Chile) classified as unemployed; and between 31.9 percent (Bolivia) and 56.5 percent (Chile) classified as inactive. We caution against overinterpreting these employment patterns, which likely reflect a combination of differences in these populations’ age structure, economic status, and the classification methods used by national statistical agencies. The latter may be particularly critical if IFPs in some countries are disproportionately engaged in subsistence activities, which represent meaningful employment but may be classified as informal by some agencies.

At least half of the IFPs in every country are married, though the prevalence of individuals in marital unions ranges from 53.0 in Chile to 72.7 percent in Peru. The prevalence of (currently-single) divorcees generally ranges from two to four percent, with the exception of Brazil, where it is much higher (7.9 percent). We again underscore the likely variation in how marriage is conceptualized and practiced among indigenous and non-indigenous populations across the region. Regarding migration, we find that inter-province migration rates range from just 1.1 percent in Colombia to a full 9.8 percent in Chile and 12.8 percent in Costa Rica. Taken together, these results highlight the heterogenous local and national contexts of Latin American IFPs. IFPs appear to benefit from national-level patterns of development, though less than non-indigenous and non-forest peoples. At the same, the primarily Amazonian IFPs in Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru remain very poor and isolated from the rapid changes happening in coastal and highland cities where most of the non-IFP population resides.

Finally, the results by ethno-linguistic group (Tables A1–A5) reveal that small, forest-dependent groups of IFPs tend to be most materially deprived and earliest in the demographic transition. This pattern is particularly clear in Amazonian countries. For example, the Asháninka in Peru, the Chiquitano in Bolivia, and the Chachi, Huaorani, Siona and Zapara in Ecuador have, for many outcomes, somewhat lower standards of living and younger age structures than larger and less-forest dependent groups. Nonetheless, the starkest contrast remains between IFPs and other national populations, and no IFP group stands out as having escaped considerable material deprivation or fully transitioned to a low-fertility, low-growth demographic regime.

5.3. Fertility patterns by indigenous and forest-dwelling status

In our ensuing analyses, we compare and analyze patterns of fertility among reproductive-age women (15–49 years) by indigenous status and between heavily-forested districts and other localities in the region. We begin by describing the characteristics of the entire population, as well as of the subset of indigenous forest-dwellers in particular (Table 3). Consistent with the full sample described above, approximately 0.5 percent of reproductive-aged women in the sample are members of the indigenous forest population and an additional 3.6 percent are members of indigenous groups living outside of heavily-forested districts. The women in our sample have given birth to 1.8 children on average, but the mean among indigenous forest-dwellers in particular is nearly 3 children. We observe this relatively high fertility rate despite a somewhat lower-than-average mean age (29.1 years) among indigenous forest-dwelling women, which suggests elevated age-specific fertility rates among this population. Consistent with these higher levels of fertility, indigenous forest-dwellers are more likely than average to be married or in a union (69.6% vs. 57.1%) and less likely to have completed primary school (44.5% vs. 71.7%), which respectively tend to be positively and inversely correlated with fertility. As such, between-group differences in the unadjusted average number of children ever born may reflect systematic differences in age, marital status, or education.

Table 3.

Demographic and economic characteristics, women age 15–49 years, total and indigenous-forest-dwellers only

| Variable | Total | Indigenous, forest-dweller |

|---|---|---|

| Group | ||

| Indigenous, forest-dweller | 0.51% | - |

| Non-indigenous, forest-dweller | 4.87% | - |

| Indigenous, not forest-dweller | 3.59% | - |

| Non-indigenous, not forest-dweller | 91.03% | - |

| Children ever born | 1.81 | 2.98 |

| Age | 29.90 | 29.07 |

| Educational attainment = primary school+ | 71.71% | 44.46% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single, never married | 33.61% | 25.22% |

| Married or in union | 57.12% | 69.62% |

| Separated, divorced, or spouse absent | 7.82% | 3.47% |

| Widowed | 1.45% | 1.70% |

| Place of residence = rural | 17.81% | 66.46% |

| Country | ||

| Bolivia | 1.69% | 9.86% |

| Brazil | 44.86% | 7.28% |

| Chile | 3.61% | 1.62% |

| Colombia | 10.15% | 7.93% |

| Costa Rica | 0.92% | 1.25% |

| Ecuador | 2.82% | 5.66% |

| Mexico | 23.83% | 46.32% |

| Peru | 6.46% | 18.63% |

| Venezuela | 5.66% | 1.44% |

| N (weighted) | 104,042,292 | 528,956 |

| N (unweighted) | 8,329,430 | 71,094 |

Note: Means and percentages reported.

We account for potentially confounding factors by estimating two Poisson regression models predicting the number of children ever born to the women in our sample (Table 4). We estimate the first model among the full sample of women (Model 1), and predict children ever born as a function of indigenous and forest-dweller status, controlling for age (modeled as a quadratic function), educational attainment, marital status, rural (urban) residence, and country of residence. The goal of this analysis is to estimate the magnitude of differences in fertility between indigenous forest dwellers and other reference groups that cannot be explained by variation in other population characteristics known to be correlated with fertility. Estimates show that after accounting for the sociodemographic and geographic controls in the model, indigenous forest-dwellers have significantly higher achieved fertility than both indigenous and non-indigenous populations living outside of heavily-forested districts. Compared to the indigenous forest-dweller reference group, fertility rates are approximately 9.3 percent lower (incidence rate ratio, IRR=0.915) among indigenous women outside of heavily-forested districts; and approximately 17.6 percent lower (IRR=0.849) among non-indigenous women who are not forest dwellers. In contrast, indigenous forest-dwellers have lower achieved fertility than non-indigenous populations in the same heavily-forested districts. Interestingly, this pattern is different than what we observe in the unadjusted group-specific statistics for the forest-dwelling population, with showed means of 3.0 children ever born to indigenous women and 2.2 children ever born to non-indigenous women. These results therefore suggest that higher unadjusted levels of fertility among IFPs than non-indigenous forest-dwellers can be explained by differences in their sociodemographic and geographic characteristics. That said, the estimated magnitude of this adjusted between-group difference is substantively rather small, with point estimates revealing an approximately 3.0 percent (IRR=1.030) difference in fertility rates between non-indigenous forest-dwellers and the IFP reference group. Forest-dwellers have high fertility even accounting for other characteristics, with indigenous fertility being slightly lower than non-indigenous fertility among this population.

Table 4.

Poisson regression models of children ever born, women age 15–49 years, total and indigenous-forest-dwellers only

| Variable | (Model 1) | (Model 2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Indigenous, forest-dweller | |||

| β | IRR | β | IRR | |

| Group | ||||

| Indigenous, forest-dweller | (ref) | - | ||

| Non-indigenous, forest-dweller | 0.0292 | 1.0296 *** | - | |

| Indigenous, not forest-dweller | −0.0889 | 0.9150 *** | - | |

| Non-indigenous, not forest-dweller | −0.1627 | 0.8498 *** | - | |

| Age | 0.1868 | 1.2054 *** | 0.2209 | 1.2472 *** |

| Age-squared | −0.0021 | 0.9979 *** | −0.0025 | 0.9975 *** |

| Educational attainment = primary school+ | −0.4269 | 0.6525 *** | −0.2644 | 0.7676 *** |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single, never married | (ref) | (ref) | ||

| Married or in union | 1.5884 | 4.8958 *** | 1.7244 | 5.6092 *** |

| Separated, divorced, or spouse absent | 1.5240 | 4.5905 *** | 1.4987 | 4.4758 *** |

| Widowed | 1.6028 | 4.9669 *** | 1.6056 | 4.9808 *** |

| Place of residence = rural | 0.1914 | 1.2110 *** | 0.1155 | 1.1224 *** |

| Country | ||||

| Bolivia | (ref) | (ref) | ||

| Brazil | −0.4376 | 0.6456 *** | −0.2182 | 0.8040 *** |

| Chile | −0.3174 | 0.7280 *** | −0.4963 | 0.6088 *** |

| Colombia | −0.2982 | 0.7422 *** | −0.2235 | 0.7997 *** |

| Costa Rica | −0.2259 | 0.7978 *** | −0.0111 | 0.9889 |

| Ecuador | −0.1264 | 0.8813 *** | 0.1215 | 1.1292 *** |

| Mexico | −0.1553 | 0.8562 *** | −0.1525 | 0.8586 *** |

| Peru | −0.2957 | 0.7440 *** | −0.1941 | 0.8236 *** |

| Venezuela | −0.0877 | 0.9160 *** | 0.0118 | 1.0119 |

| N (weighted) | 104,042,292 | 528,956 | ||

| N (unweighted) | 8,329,430 | 71,094 | ||

Note:

p<0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

Constant not shown.

The coefficients on control variables in this first model are consistent with prior demographic research and expectations. For instance, age is positively associated with achieved fertility but the marginal increase in children ever born declines at higher ages, where age-specific fertility rates are low. Marital unions are also positively associated with fertility; education is negatively associated with the number of children ever born; and rural women have higher fertility than urban women. We also find evidence of cross-national differences in fertility rates net of the sociodemographic controls in the model: The number of children ever born is significantly lower than the reference country of Bolivia in each of the other countries in our sample, with IRR point estimates ranging from 0.916 to 0.646.

Next, we estimate a second model predicting the number of children ever born among only the indigenous forest population (Model 2). Our goal is to understand the sociodemographic variables that explain fertility differentials within this population. The results are consistent with commonly-observed socioeconomic gradients in fertility, which suggests that IFPs are subject to similar fertility-determining processes as many other populations. For example, educational attainment is negatively associated with fertility among indigenous forest-dwelling women: women with a primary school education or more have approximately 30.3 percent lower (IRR=0.768) fertility rates than comparable women who did not complete primary school. Indigenous women living in urbanized areas within heavily-forested districts also have significantly lower fertility than their counterparts in rural areas of such districts; and experience in marital unions—both current and previous—is positively associated with women’s achieved fertility at the time of the census. For example, fertility among women who are currently married or in a union is more than five-times higher than among single, never married women (IRR=5.609). Point estimates are slightly lower among women who are widowed or separated, divorced, or have a spouse absent, but remain more than four-times the fertility rates of single, never married women.

Relative to the national populations, age and marital status appear to be somewhat more important determinants of fertility among IFPs, whereas education and urbanicity appear to be somewhat less important. These patterns are consistent with more traditional fertility practices that persist even among well-educated and urban IFPs. Cross-national differences in fertility rates among indigenous forest-dwelling women also remain after controlling for the social and demographic factors included in the model. Relative to the reference country of Bolivia, for example, statistically significant point estimates of cross-national differences in fertility rates range from −64.3 percent in Chile to −16.5 percent in Mexico. By contrast, the fertility rates of indigenous forest women in Costa Rica and Venezuela are not statistically different from Bolivia. Of course, these cross-national patterns may mask important sub-national heterogeneity between IFP groups (as our descriptive analysis suggested) and should therefore be interpreted with some caution.

5.4. District-level migration patterns

Finally, we conduct a district-level analysis of long-distance in-migration rates to evaluate whether indigenous and non-indigenous in-migrants are over- or under-represented in highly-forested areas. While these analyses cannot tell us whether migration patterns are leading to changes in population size, they provide insight into whether heavily-forested and heavily-indigenous districts are attracting in-migrants from other provinces more (or less) than other areas. We begin by describing select characteristics of the districts in our sample (Table 5), estimating averages across all districts and then separately for the set of heavily-forested districts as defined above. On average, heavily-forested districts have disproportionately high indigenous population shares (23.4% vs. 11.4% overall), smaller (25,437 vs. 40,464) and younger (median age = 32.3 vs. 34.1) populations, lower rates of primary school attainment (43.4% vs. 49.7%), and higher rates of individuals in marital unions (61.0% vs. 60.2%). The populations of heavily-forested districts are also, on average, more likely to reside in a rural settlement (54.0%) than the overall district-level average (45.9%). Finally, we note that these high-forest districts are also disproportionately large (11,335 vs. 2,567 km2), overrepresented in Columbia, Peru, and Ecuador, and underrepresented in Mexico.

Table 5.

Demographic and economic characteristics of districts (level-2 subnational units) in sample

| Variable | Total | Forest districts |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous population | 11.39% | 23.40% |

| Population size, excluding migrants (10,000 persons) | 4.05 | 2.54 |

| Tree cover (%) | 32.38 | 85.22 |

| Indigenous in-migrants, per 100 of district population | 0.27 | 0.48 |

| Non-indigenous in-migrants, per 100 of district population | 3.56 | 3.91 |

| Median age | 34.13 | 32.27 |

| Educational attainment = primary school+ | 49.73% | 43.44% |

| Married | 60.18% | 61.02% |

| Rural | 45.92% | 54.05% |

| Land area (1,000 sq. km) | 2.57 | 11.34 |

| Country | ||

| Bolivia | 1.34% | 2.10% |

| Brazil | 38.42% | 38.67% |

| Chile | 3.01% | 1.14% |

| Colombia | 7.92% | 12.57% |

| Costa Rica | 1.02% | 2.29% |

| Ecuador | 2.15% | 3.81% |

| Mexico | 39.48% | 29.33% |

| Peru | 2.83% | 6.10% |

| Venezuela | 3.83% | 4.00% |

| N (districts) | 6,185 | 525 |

Note: District-level variables represent weighted means and percentages among population age 15+.

Our multivariate analyses (Table 6) begin by estimating models of in-migration rates that treat tree cover as a continuous variable but include a quadratic term to allow migration to vary non-linearly according to forest density. Our respective models of indigenous (Model 3) and non-indigenous in-migration (Model 6) both reveal a pattern whereby in-migration rates initially decline as tree cover increases from zero, but the magnitude of these marginal declines decreases and the marginal change eventually becomes positive at high levels of tree cover. We illustrate these relationships in Figure 2, which plots the predicted indigenous (left panel, derived from Model A) and non-indigenous (right panel, derived from Model D) in-migration rates across different levels of tree cover while holding all other district characteristics at their means. Note that the y-axis scale on these graphs are considerably different. While in both cases we see a trend toward increasing in-migration rates in heavily-forested districts, the curvilinear relationship between in-migration rates and tree cover is more pronounced for the indigenous in-migration rate—at least in proportional terms. For example, as district tree cover increases from 50 to 100 percent, the predicted number of indigenous in-migrants per 100 of the total district population increases by over 45 percent, from 0.236 to 0.344. The corresponding increase in the number of non-indigenous in-migrants—from 3.462 to 4.089—is larger in absolute terms but represents a proportionately-smaller 18.1 percent increase over the predicted value at 50 percent tree cover. While representation of indigenous in-migrants is more strongly associated with forest cover in the destination, these in-migration flows are dwarfed by the larger number of non-indigenous in-migrants to heavily-forested districts.

Table 6.

Linear regression models predicting number of in-migrants per 100 of district population, by group

| Variable | (Model 3) | (Model 4) | (Model 5) | (Model 6) | (Model 7) | (Model 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous in-migrants | Non-indigenous in-migrants | |||||

| Total | Total | Forest districts | Total | Total | Forest districts | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Tree cover (%) | −0.0035 ** | - | - | −0.0132 ** | - | - |

| Tree cover (%), squared | 0.0000 ** | - | - | 0.0002 ** | - | - |

| Forest district = yes | - | 0.0731 ** | - | - | 0.4427 ** | - |

| Indigenous population (proportion) | 1.6863 *** | 1.6667 *** | 1.3627 *** | −2.5739 *** | −2.6198 *** | −4.3114 *** |

| Population size, excluding migrants (10,000 persons) | −0.0004 | −0.0005 | −0.0129 | −0.0015 | −0.0016 | −0.0471 |

| Median age | 0.0229 *** | 0.0242 *** | 0.0041 | −0.0725 *** | −0.0700 *** | −0.1570 † |

| Educational attainment = primary school+ (proportion) | 0.6459 *** | 0.6731 *** | 2.0028 *** | 5.7081 *** | 5.7893 *** | 12.8419 *** |

| Married (proportion) | −1.0623 *** | −1.0678 *** | −0.1775 | 8.4279 *** | 8.4519 *** | 25.0579 *** |

| Rural | 0.1213 ** | 0.1136 ** | 0.4216 ** | −0.5392 ** | −0.5538 ** | 0.0710 |

| Land area (1,000 sq. km) | 0.0019 † | 0.0019 † | 0.0004 | 0.0393 *** | 0.0394 *** | 0.0191 ** |

| Country | ||||||

| Bolivia | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) |

| Brazil | −1.8547 *** | −1.8817 *** | −2.3323 *** | 0.6837 † | 0.6008 | 0.7675 |

| Chile | −1.8649 *** | −1.8970 *** | −1.7878 *** | 2.4696 *** | 2.3867 *** | 1.9409 |

| Colombia | −2.1097 *** | −2.1571 *** | −2.8284 *** | −0.0507 | −0.1744 | −2.2088 |

| Costa Rica | −1.8453 *** | −1.8996 *** | −2.2735 *** | 3.4391 *** | 3.3095 *** | 0.3220 |

| Ecuador | −1.7767 *** | −1.8181 *** | −2.2950 *** | 2.5396 *** | 2.4232 *** | 7.3870 *** |

| Mexico | −1.9184 *** | −1.9354 *** | −2.7234 *** | −0.7652 ** | −0.8197 ** | −1.7743 |

| Peru | −1.7414 *** | −1.7415 *** | −2.1700 *** | 0.1009 | 0.1006 | −0.6999 |

| Venezuela | −2.0558 *** | −2.1005 *** | −2.9822 *** | 1.2930 ** | 1.1704 ** | −1.1963 |

| N (districts) | 6,185 | 6,185 | 525 | 6,185 | 6,185 | 525 |

Note:

p<0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

Constant not shown. District-level variables represent weighted means/proportions among population age 15+.

Figure 2.

Predicted number of in-migrants per 100 of district population, stratified by indigenous (left) and non-indigenous (right) populations

As a complementary approach, we also estimate a model of in-migration rates that compares the discrete group of heavily-forested districts with all others (Models 4 and 7). Consistent with the results presented above, we find that both indigenous and non-indigenous in-migration rates are significantly higher in heavily-forested districts relative to all others. On average and net of the district characteristics included as controls in the model, indigenous in-migration rates are 0.073 per 100 of the district population higher in heavily-forested districts than all others; and non-indigenous in-migration rates are 0.443 higher in heavily-forested versus other districts. Importantly, the magnitude of these associations appears to be substantively important in the context of a mean indigenous in-migration rate of 0.27 per 100 and non-indigenous in-migration rates of 3.56 per 100. This finding provides further support that the representation of in-migrants increases in step with tree cover, irrespective of differences in the other observed characteristics between high- and low-forest districts.

In a final set of analyses, we examine patterns of indigenous and non-indigenous migration in heavily-forested districts only. The model of indigenous in-migration (Model 5) suggests that the rate of indigenous in-migration is positively correlated with districts’ indigenous population share, educational attainment, and rurality. There are also statistically significant cross-national differences in indigenous in-migration rates, all of which are lower than in the reference country of Bolivia. In contrast, non-indigenous in-migration rates (Model 8) are inversely associated with indigenous representation in districts’ populations. Non-indigenous in-migration rates are also positively associated with educational attainment and proportion married. Additionally, there is very little in the way of cross-national differences in non-indigenous in-migration rates after adjusting for other district characteristics, at least relative to the reference group of Bolivia. Only in Ecuador are non-indigenous in-migration rates into heavily-forested districts statistically different—and higher—than Bolivia. A key take-away from this analysis is that among potential destinations, the relative size of indigenous populations is positively associated with indigenous in-migration rates but negatively associated with non-indigenous inflows. The magnitude of the latter association is much larger than the former, indicating that in-migrants overall tend to be underrepresented in forested districts with large indigenous populations.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis of socioeconomic and demographic outcomes among the IFPs in nine Latin American countries leads to a number of broad conclusions about the wellbeing and demographic trajectory of these distinctive populations. In general, IFPs are younger, more likely to be married, less likely to migrate, and more socioeconomically disadvantaged than non-indigenous populations in the same heavily-forested districts, as well as indigenous and non-indigenous populations in other areas of the region. Unadjusted fertility levels are also disproportionately high among IFPs, but differentials relative to non-indigenous populations in heavily-forested districts are fully explained by demographic and geographic characteristics. In fact, IFPs’ fertility rates would be lower than their non-indigenous counterparts if the social and demographic characteristics (as included in our model) of both groups were the same. The implication is that the independent association between indigeneity and fertility is negative, and this is particularly true in heavily-forested districts. Such patterns would seemingly place upward pressure on non-indigenous populations in these biologically-rich locations, which our results suggest are amplified by migration patterns. Indeed, we find that non-indigenous individuals comprise the majority of in-migrants to forested areas, and that non-indigenous in-migration rates increase in step with levels of tree cover (but are offset by indigenous inhabitants).

Our analyses also yield evidence of considerable variation in characteristics among IFPs, both cross-nationally and between specific ethno-linguistic groups. In addition to large differences in the absolute and relative size of indigenous forest populations across the countries in our sample, we find substantively important differences in their demographic and socioeconomic profiles, with the IFPs in certain countries—such as Chile, Mexico, Venezuela—distinctively better off than others—such as Peru and Ecuador. Of course, the relative advantages among the former do not negate the fact that these populations are still characterized by large absolute deficits in education, access to basic services, and other dimensions of wellbeing. Members of small, forest-dependent ethnic groups in Amazonian countries are particularly deprived across multiple social outcomes. Finally, our multivariate analyses of fertility and migration patterns among IFPs found statistically and substantively significant cross-national differences in these outcomes, indicating that distinctions among IFPs cannot be reduced to the socioeconomic characteristics included in our regression models.

In addition to these substantive findings, our study makes a methodological contribution to research on indigenous populations and their interactions with the environment by demonstrating the utility of harmonized census microdata from across multiple countries, which are increasingly available (Ruggles 2014). Linking these georeferenced data to tree cover estimates, we conduct what is to our knowledge the first cross-national analysis of a representative sample of IFPs. We anticipate that scholars will build on this approach in future research, conducting analyses of similar populations in other regions of the world and using consecutive censuses and longitudinal environmental data to study the interaction between demographic and environmental changes in biologically-rich areas (Bilsborrow & DeLargy 1990; Myers 1990; Chu & Yu 2002; Evans & Moran 2002). However, as researchers continue to analyze these harmonized data to study indigenous populations across multiple countries and time periods, they should also remain attentive to the important differences between indigenous groups—both between and within countries.

Our results also have clear policy implications. They are consistent with previous findings that indigenous forest-dwelling populations are growing rapidly (McSweeney & Arps 2005), and that this demographic turnaround can be interpreted as enabling IFPs to assert themselves vis-à-vis the political and cultural forces of non-indigenous settler populations. This growth might also be interpreted as a threat to biodiversity, but it has occurred during the same period in which numerous studies have documented that indigenous tenure protects forests (Asner et al. 2005; Nepstad et al. 2006; Adeney et al. 2009; Nolte et al. 2013; Holland et al. 2014; Blackman et al. 2017). The greater threat to Latin American forests appears to come from non-indigenous forest residents and in-migrants, who far outnumber IFPs and are often involved in the exploitation of natural resources. Providing additional educational and health services in these areas would likely reduce deforestation while also hastening desirable development and demographic transitions among IFPs. However, we make this recommendation in a context where the political demands and recognition of IFPs have been routinely ignored by Latin American governments, who have instead prioritized frontier settlement and resource extraction (Sawyer 2004; Nancy & Zamosc 2005; Lu et al. 2016). In some cases, including the current Bolsonaro administration in Brazil, governments in the region have actively encouraged the implementation of indigenous-hostile policies. Progress on IFP well-being as well as deforestation are thus conditional on engaging with, and substantively addressing, these political issues.

Building on our static analysis at a single time point, future research should similarly leverage census and satellite data to empirically assess the protective effects of indigenous populations on tropical forests across the region. Studies should also examine whether and how such effects may vary. For example, can the benefits of indigenous tenure persist given indigenous and non-indigenous population growth in forested areas? Do fertility transitions among indigenous and other forest peoples relieve pressures on natural resources (Davis et al. 2015)? The demographic, development, and cultural futures of IFPs remain very unclear, but new data sources such as IPUMS’ harmonized and georeferenced census microdata will help researchers provide additional clarity going forward.

Appendix

Table A1.

Demographic and economic characteristics of indigenous forest-dwelling population in Bolivia, by ethnic or linguistic group

| Variable | Quechua | Aymara | Guarani | Chiquitano | Mojeño | Other Indigenous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous individuals | ||||||

| Age 0–14 | 47.94% | 41.41% | 45.82% | 48.35% | 51.18% | 51.82% |

| Age 65+ | 3.50% | 4.49% | 3.61% | 3.48% | 4.55% | 3.99% |

| Sex = female | 45.96% | 45.22% | 43.73% | 45.75% | 40.74% | 45.47% |

| Household size | 5.72 | 4.73 | 6.58 | 7.02 | 6.58 | 6.94 |

| Number of children age <5 in household | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Place of residence = rural | 74.19% | 82.61% | 53.42% | 54.30% | 37.21% | 59.15% |

| Number of rooms in housing unit | 2.01 | 2.10 | 2.00 | 2.30 | 2.38 | 2.16 |

| Electricity access = yes | 29.44% | 37.43% | 35.17% | 37.23% | 44.61% | 21.15% |

| Access to water supply = yes | 48.26% | 63.32% | 38.78% | 43.18% | 46.97% | 29.17% |

| Phone access = yes | 5.74% | 3.53% | 4.94% | 7.76% | 6.73% | 2.09% |

| Share of group’s total population | 3.77% | 5.62% | 4.07% | 21.54% | 8.51% | 24.29% |

| N (weighted) | 93,760 | 108,320 | 5,260 | 40,830 | 5,940 | 30,550 |

| N (unweighted) | 9,376 | 10,832 | 526 | 4,083 | 594 | 3,055 |

| Indigenous adults (age 15+) | ||||||

| Educational attainment = primary school+ | 44.31% | 57.71% | 51.23% | 59.36% | 64.83% | 51.15% |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, never married | 25.69% | 26.02% | 30.53% | 31.53% | 30.34% | 27.17% |

| Married or in union | 67.67% | 64.81% | 62.11% | 62.26% | 60.69% | 66.37% |

| Separated, divorced, or spouse absent | 1.91% | 2.82% | 2.46% | 2.66% | 5.52% | 2.65% |

| Widowed | 4.73% | 6.35% | 4.91% | 3.56% | 3.45% | 3.80% |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 61.83% | 75.84% | 58.95% | 55.76% | 70.00% | 63.65% |

| Unemployed | 1.21% | 0.69% | 1.75% | 1.99% | 2.41% | 0.48% |

| Inactive | 36.96% | 23.46% | 39.30% | 42.25% | 27.59% | 35.87% |

| Inter-province migration within 5 years = yes | 13.01% | 4.19% | 7.72% | 1.71% | 20.00% | 5.71% |

| Share of group’s total population | 3.43% | 5.48% | 4.10% | 20.45% | 7.62% | 21.95% |

| N (weighted) | 48,810 | 63,460 | 2,850 | 21,090 | 2,900 | 14,720 |

| N (unweighted) | 4,881 | 6,346 | 285 | 2,109 | 290 | 1,472 |

Note: Means and percentages reported. The universe for indigenous status is restricted to persons age 15+. For those outside of this universe, we apply the indigenous status of the household head.

Table A2.