Abstract

Background

Bed rest used to be widely advised for women with a multiple pregnancy.

Objectives

The objective was to assess the effect of bed rest in hospital for women with a multiple pregnancy for prevention of preterm birth and other fetal, neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (May 2010).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials which compare outcomes in women with a multiple pregnancy and their babies who were offered bed rest in hospital with women only admitted to hospital if complications occurred.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors carried out assessment for inclusion and risk of bias of the trials. We extracted and double entered data, and used a random‐effects model.

Main results

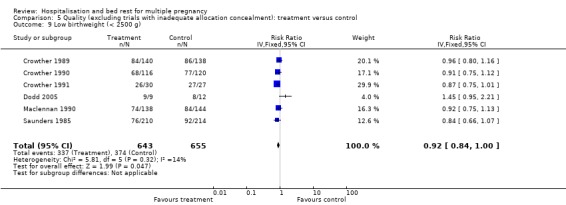

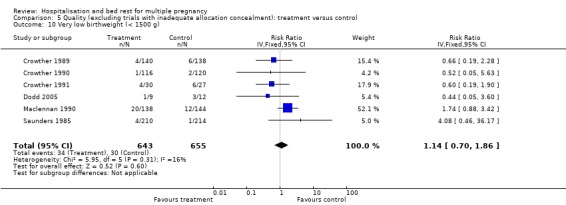

We included seven trials which involved 713 women and 1452 babies. Routine bed rest in hospital for multiple pregnancy did not reduce the risk of preterm birth, or perinatal mortality. There was substantial heterogeneity related to perinatal death and stillbirth unaccounted for by trial quality. There was a suggestion of a decreased number of low birthweight infants (less than 2500 g) born to women in the routinely hospitalised group (risk ratio (RR) 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 1.00). No differences were seen in the number of very low birthweight infants (less than 1500 g). No support for the policy was found for other neonatal outcomes. No information is available on developmental outcomes for infants in any of the trials.

For the secondary maternal outcomes reported of developing hypertension and caesarean delivery, no differences were seen. Women's views about the care they received were reported rarely.

In the subgroup analyses for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, with cervical dilation prior to labour with a twin pregnancy and with a triplet pregnancy, no differences were seen in any primary and secondary neonatal outcomes and maternal outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

There is currently not enough evidence to support a policy of routine hospitalisation for bed rest in multiple pregnancy. No reduction in the risk of preterm birth or perinatal death is evident, although there is a suggestion that fetal growth may be improved. For women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy the results of this review show no benefit from routine hospitalisation for bed rest. Until further evidence is available, the policy cannot be recommended for routine clinical practice.

Plain language summary

Hospitalisation and bed rest for multiple pregnancy

We found no strong evidence that bed rest in hospital for women with a multiple pregnancy decreases the risk of a preterm birth. Multiple pregnancies have a higher risk of preterm (early) birth and poor growth of the babies than a single pregnancy. Bed rest during the latter half of pregnancy has been widely used as a policy for women carrying more than one baby. This was to reduce the risk of preterm birth and restricted fetal growth and to improve the health of both the mother and her babies. We identified seven controlled trials involving 713 women who were randomly offered bed rest in hospital or only admitted to hospital if complications occurred, and 1452 babies. In five of the trials the women were carrying twins, triplets in the other two trials.

Bed rest did not show benefits for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy. Overall, routine bed rest in hospital for multiple pregnancies did not reduce the risk of preterm birth or perinatal deaths. There was a suggestion of a decrease in the number of low birthweight infants (less than 2500 g) when women were routinely hospitalised. Only one trial provided information about what women thought about their care in the routinely hospitalised group. While a small number appreciated admission, a number found it psychologically distressing. Four of the seven trials were conducted in Harare, Zimbabwe.

The review of trials found routine bed rest in hospital did not decrease the risk of a preterm birth, but may improve growth of the infants. Benefits of bed rest in hospital for women with triplets were seen but these could equally have been due to chance.

Background

Multiple pregnancy is associated with increased fetal (the unborn baby) and neonatal (the baby from birth to four weeks of age) mortality compared with singleton pregnancy, and morbidity is high amongst survivors (Crowther 2005). The higher the order of multiple pregnancy, the greater the risk of mortality and morbidity. The majority of perinatal (referring to the period of time before, during, and the first week after birth) deaths are associated with preterm birth and intrauterine (inside the uterus) growth restriction. Fetal growth is reduced from 27 to 30 weeks in twins and from the 27th week in triplets compared with singletons (McKeown 1952).

Interventions for multiple pregnancy that reduce the risk of early birth and/or the risk of poor fetal growth would be an important advance in care. Based on observational studies in the early 1950s that identified improved perinatal outcome in twins born to middle‐class women (Russell 1952), the suggestion that 'admitting to hospital all twin mothers at the 30th week in order by diet and rest to tide them over the danger period' became widely accepted into obstetric practice. No evidence was produced to show the benefits expected from such a practice. Hospitalisation is often a disruptive and stressful experience for women and their families. In addition, hospitalisation is costly to the health services.

Women at especially high risk of preterm birth might be expected to derive greatest benefit from hospitalisation for bed rest if effective. Beneficial effects of hospitalisation for bed rest might include prolongation of pregnancy to achieve greater fetal maturation at birth, improvement in fetal growth and optimal intrapartum (referring to the period of time during labour and birth) management, as labour if early would begin in hospital. Women with a triplet or higher order multiple pregnancy have an increased risk of preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction compared with women having twins. Similarly, women with a twin pregnancy who have evidence on cervical assessment of cervical effacement and dilatation (low cervical score) are at increased risk of preterm birth compared with women who have an uncomplicated twin pregnancy (Houlton 1982; Neilson 1988).

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of hospitalisation for bed rest in women with a multiple pregnancy on the risk of preterm birth, fetal and neonatal mortality, neonatal morbidity, and women's satisfaction with their care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published, unpublished and ongoing randomised trials with reported data which compare outcomes in women and their babies who were offered hospitalisation for bed rest during pregnancy compared with women who did not receive routine hospitalisation.

Types of participants

Women with a multiple pregnancy.

Types of interventions

Hospitalisation for bed rest during the antenatal period compared with a policy of selective admission.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes are preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and fetal growth. Secondary outcomes include other neonatal morbidity, long‐term disability, maternal morbidity and women's assessment of their care.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (May 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 1.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the trial identified by the new search (Dodd 2005) as well as the trials awaiting classification (al‐Najashi 1996; Younis 1990).

Selection of studies

The review author (CA Crowther) assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified in the previous version of this review (Crowther 1999). Two review authors (CA Crowther and S Han) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy for this update. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies included in the previous version of this review, CA Crowther extracted data; For eligible studies identified in this update, two review authors (CA Crowther and S Han) extracted data by using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We judged studies at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

adequate (e.g. where there were no missing data or where reasons for missing data are balanced across groups);

inadequate (e.g. where missing data are likely to be related to outcomes or are not balanced across groups);

unclear (e.g. where there is insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit a judgement to be made).

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias. For example, was there a potential source of bias related to the specific study design? Was the trial stopped early due to some data‐dependent process? Was there extreme baseline imbalance? Has the study been claimed to be fraudulent?

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T2, I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if T2 was greater than zero and either I2 is greater than 30% or there was a low P‐value (< 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

If we identified high levels of heterogeneity among the trials (exceeding 30%), we explored it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis and performed sensitivity analysis. We used a random‐effects meta‐analysis as an overall summary if this was considered appropriate.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspect reporting bias (see 'Selective reporting bias' above) we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing was data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

Where we suspected publication bias (e.g. where only statistically significant results are reported), we explored this using funnel plots. We involved the project statistician in the interpretation of such analysis.

Intention to treat analysis (ITT)

We analysed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they are allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. If in the original reports participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there was sufficient information in the trial report, we attempted to restore them to their allocated group.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition and exclusions)

See 'Assessment of risk of bias' and Assessment of reporting biases sections.

Selective outcome reporting bias

Already addressed in 'Assessment of risk of bias' and Assessment of reporting biases sections above.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analysis for combining data where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were are judged sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or methodological heterogeneity between studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects may differ between trials, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis.

If we identified substantial heterogeneity in a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, we noted this and repeated the analysis using a random‐effects method.

The denominator for maternal outcomes was the number of women; the denominator for neonatal outcomes was the number of babies.

We synthesised data separately for studies with a low risk of bias and those with a high risk of bias to explore the impact of possible bias on review findings.

When appropriate, we synthesised data from studies where results were expressed as dichotomous and continuous data. We involved the project statistician before attempting to synthesise different measures of treatment effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy;

hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy;

hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy.

We analysed all prespecified outcome measures in subgroup analysis. For fixed‐effect meta‐analyses we conducted planned subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001. For random‐effects meta‐analyses we assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality for important outcomes in the review. Where there was risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality (e.g. inadequate allocation concealment), we explored this by sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

We identified eight trials of antenatal hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, of which seven meet the selection criteria (Crowther 1989; Crowther 1990; Crowther 1991; Dodd 2005; Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984; Maclennan 1990; Saunders 1985), and one was identified as new for this update (Dodd 2005). In the excluded trial all women in the study were in hospital for bed rest (Gummerus 1985). A further two studies (al‐Najashi 1996; Younis 1990) were awaiting assessment as to whether they are randomised trials, as their primary reports were unclear about this. In this update, we contacted authors of these two studies, but have received no response to date .

The seven included trials involved 713 women and 1452 babies (Crowther 1989; Crowther 1990; Crowther 1991; Dodd 2005; Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984; Maclennan 1990; Saunders 1985). Five trials of hospitalisation for bed rest involved women with a twin pregnancy (687 women and 1374 babies) (Crowther 1989; Crowther 1990; Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984; Maclennan 1990; Saunders 1985) and two trials involved women with a triplet pregnancy (26 women and 78 babies) (Crowther 1991; Dodd 2005). We have provided details of each study in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

All except one of the trials (Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984) were randomised trials. Maclennan 1990 used a central telephone agency, and four trials used consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (Crowther 1989; Crowther 1990; Crowther 1991; Dodd 2005). Saunders 1985 used consecutively numbered, sealed envelopes, but was unclear about whether the envelopes were opaque. Allocation concealment was not met in the Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984 trial as they used quasi‐randomisation utilising odd or even year of birth.

No blinding to the intervention occurred. The primary outcome of gestational age at birth was assessed by a paediatrician blinded to treatment group in Crowther 1989, Crowther 1990 and Crowther 1991. All other trials made no comment of blinding of outcome assessments.

The rate of exclusion after randomisation was low in most of the trials. The highest rate reported was 8% for Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984.

We have provided details of risk of bias for each of the included studies in the of 'Risk of bias' table.

Effects of interventions

1. Analyses of all trials

Primary outcomes

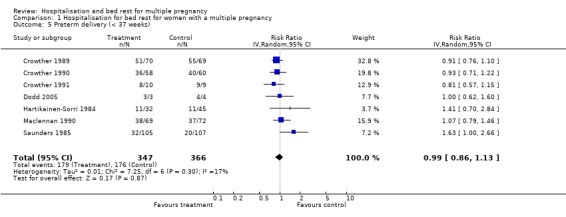

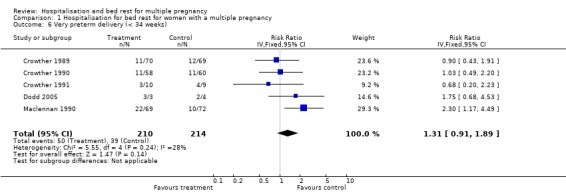

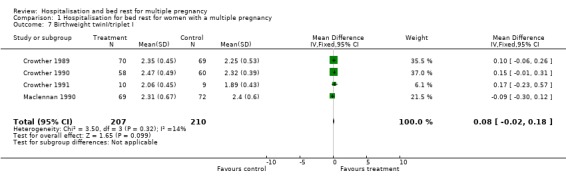

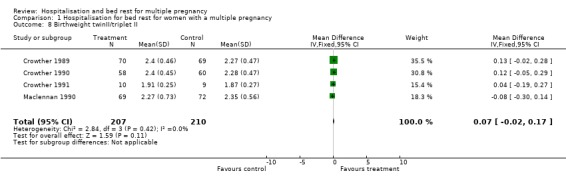

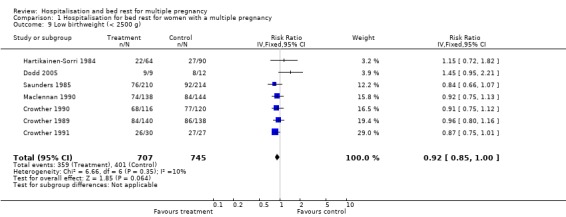

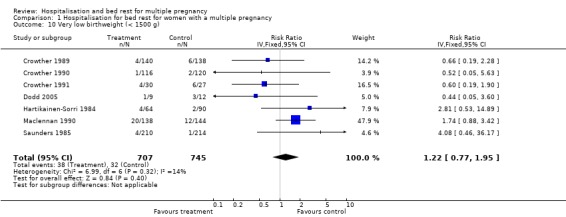

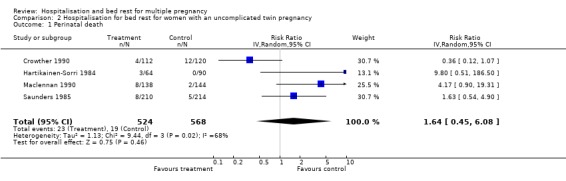

A policy of routine hospitalisation for bed rest in multiple pregnancy did not reduce the risk of preterm birth, or perinatal mortality. There was substantial heterogeneity related to perinatal death and stillbirth unaccounted for by trial quality. There was a suggestion of a decreased number of low birthweight infants (less than 2500 g) in the routinely hospitalised group which reached borderline levels of statistical significance (risk ratio (RR) 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 1.00; 7 trials; 1452 babies). No differences were seen in the number of very low birthweight infants (less than 1500 g).

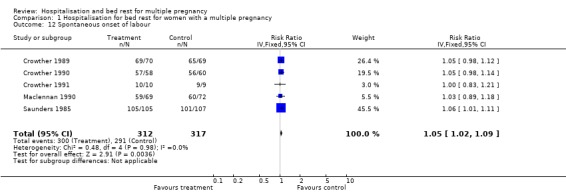

Neonatal and maternal secondary outcomes

No support for the policy was found in the secondary neonatal outcomes reported, which included depressed Apgar scores (less than seven), need for admission and length of stay of seven days or more on the neonatal unit. No information was available on developmental outcomes for infants in any of the trials.

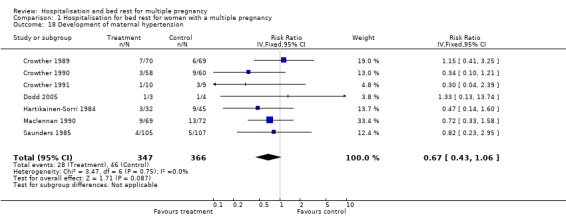

For the secondary maternal outcomes reported of developing hypertension and caesarean delivery, no differences were seen. One trial provided information about what women thought about their care in the routinely hospitalised group (Maclennan 1990): 6% 'appreciated admission' and 18% found hospitalisation for bed rest 'psychologically distressing'.

2. Analyses of hospitalisation for bed rest in women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy

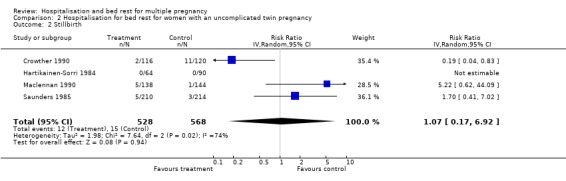

The risk of preterm birth (less than 37 weeks' gestation) was not reduced for routine bed rest in hospital for women with uncomplicated twin pregnancy, nor was the risk of very preterm birth (less than 34 weeks' gestation). No differences were seen in perinatal mortality, and there was substantial heterogeneity related to perinatal death and stillbirth unaccounted for by trial quality. No differences were seen in the measures of neonatal weight. No differences were seen for the neonatal secondary outcomes or maternal outcomes.

3. Analyses of hospitalisation for bed rest in women with a triplet pregnancy

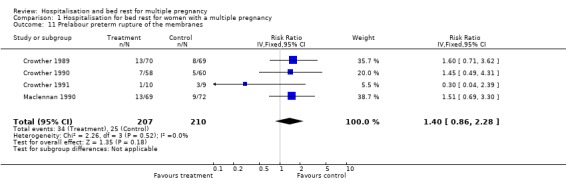

Most of the comparisons made between the hospitalised and control groups suggest beneficial treatment effects from routine hospitalisation for bed rest. However, the identified differences between the two groups were not statistically significant and the confidence limits around these treatment effects were wide. All the differences observed between the experimental and control groups were compatible with chance variation.

4. Analyses of hospitalisation for bed rest in women with a twin pregnancy complicated by cervical effacement and dilatation prior to labour

No differences were seen when compared the hospitalisation for bed rest group with the control group in the risk of preterm birth, perinatal mortality, fetal growth, the neonatal secondary outcomes, or in any of the maternal outcomes.

Discussion

There is currently no sound evidence to support a policy of routine hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy. No reduction in the risk of preterm birth or perinatal death is evident, although there is a suggestion that fetal growth may be improved. The available evidence suggests the policy to be of no benefit for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy. There has been no long‐term follow up of developmental outcome of infants in any of the trials to date. Similarly there is a paucity of information about how women and their families feel about this form of care. The minimal information available suggests that many women find routine hospitalisation distressing.

These seven trials provide only limited evaluation of the policy of routine hospitalisation for bed rest in multiple pregnancy and provide no good evidence to support the use of the policy. Four of the seven trials were conducted in Harare, Zimbabwe. The effect of the policy should be known for other obstetric populations and other racial groups. The scanty evidence available for women with a triplet pregnancy highlights the need for further research to help clarify whether there are real benefits of hospitalisation that outweigh the social and financial costs. To ensure a trial of adequate size to be able to detect small but clinically important differences, a multinational, multi‐centred collaborative trial would be needed.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is currently no sound evidence to support a policy of routine hospitalisation for bed rest in multiple pregnancy. For women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, the results of this review suggest no benefit. Until further evidence is available to the contrary, the policy cannot be recommended for routine clinical practice.

In women with triplets, although mainly beneficial effects of the policy were observed, it must be reiterated that these could all be ascribed to chance variation, and do not provide a basis for adoption of the policy into clinical practice.

For women with a twin pregnancy at high risk of preterm birth, because of signs of cervical effacement and dilatation prior to labour, there is, so far, no basis for the adoption of the policy into clinical practice.

Implications for research.

Hospitalisation for bed rest in multiple pregnancy was introduced into clinical practice without adequate controlled evaluation of its efficacy. The policy has been subjected to limited well‐controlled evaluation.

Further evaluation of the policy in women considered at higher than average risk of preterm birth and at gestational ages considered at greatest risk would seem appropriate. Further assessment of the favourable effects on fetal growth observed is warranted. Four of the seven trials were conducted in Harare, Zimbabwe. The effect of the policy needs to be known in other obstetric populations and other racial groups.

Any future trials should provide long‐term developmental outcomes for the infants, assess women's views of the care received assess costs.

For women with a triplet pregnancy, the policy has not been fully evaluated, and an international, multi‐centre trial would be necessary.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 May 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New author involved in updating the review. |

| 31 May 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated. One new trial identified and included (Dodd 2005). Authors of the two reports in Studies awaiting classification have been contacted. Risk of bias tables updated. Conclusions not changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1997 Review first published: Issue 3, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 November 2008 | Amended | Contact details edited. |

| 3 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 19 August 2000 | New search has been performed | Search updated. 4 new trials found. |

Acknowledgements

Dr Anna‐Liisa Hartikainen‐Sorri kindly provided additional unpublished data for the review, and the reviewer provided additional data from her MD thesis.

The reviews that have been combined into this systematic review were first published on the Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials in 1987. The opportunity for three of the trials reviewed to be completed, the preparation of the initial systematic reviews in 1987, and the continued updating were initially made possible by the encouragement and support given by Iain and Jan Chalmers, Jini Hetherington and staff at the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Oxford.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this updated review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

The following methods were used to assess Crowther 1989; Crowther 1990; Crowther 1991; Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984; Maclennan 1990 and Saunders 1985.

Included trial data were processed as described in Clarke 2000.

Trials under consideration were evaluated for inclusion and methodological quality. There was no blinding of authorship.

Quality scores for concealment of allocation were assigned to each trial, using the criteria described in Section 6 of the Cochrane Handbook (Clarke 2000) A = adequate, B = unclear, C = inadequate, D = not used.

In addition, quality scores were assigned to each trial for completeness of follow‐up and blinding of outcome assessment as follows:‐

Completeness of follow‐up:

(A) < 3% of participants excluded; (B) 3% ‐ 9.9% of participants excluded; (C) 10% ‐ 19.9% of participants excluded; (D) 20% or more excluded; (E) unclear.

For blinding of assessment of outcome:

(A) Double‐blind, neither investigator nor participant knew or were likely to guess the allocated treatment. (B) Single‐blind, either the investigator or the participant knew the allocation. Or, the trial is described as double‐blind, but side effects of one or other treatment mean that it is likely that for a significant proportion (>= 20%) of participants the allocation could be correctly identified. (C) No blinding, both investigator and participant knew (or were likely to guess) the allocated treatment. (D) Unclear.

Data were extracted by the reviewer and double entered. There was no blinding of authorship. Whenever possible, unpublished data were sought from investigators.

Descriptive data included authors, year of publication, setting, country, time span of the trial, pretrial calculation of sample size and number randomised and analysed. Categorical data were compared using odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical heterogeneity between trials was tested for using the chi‐squared test with n (the number of trials contributing data) minus one degrees of freedom. With no significant heterogeneity (p > 0.10), data were pooled using a fixed‐effect model. If significant heterogeneity was found, the random‐effects model was used.

All eligible trials were included in the initial analysis and sensitivity analyses have been carried out to evaluate the effect of trial quality. This was done by excluding trials given a D rating for quality for allocation concealment. Further analyses explored the effect of hospitalisation for bed rest in women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, in women with a triplet pregnancy and women with a twin pregnancy complicated by cervical effacement and dilatation prior to labour.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

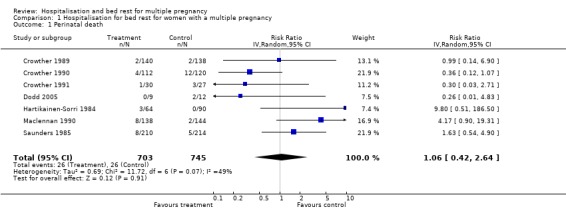

| 1 Perinatal death | 7 | 1448 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.42, 2.64] |

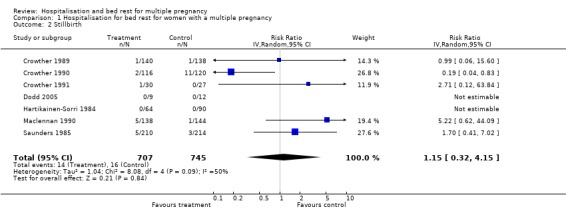

| 2 Stillbirth | 7 | 1452 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.32, 4.15] |

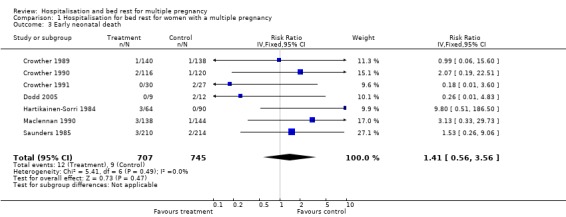

| 3 Early neonatal death | 7 | 1452 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.56, 3.56] |

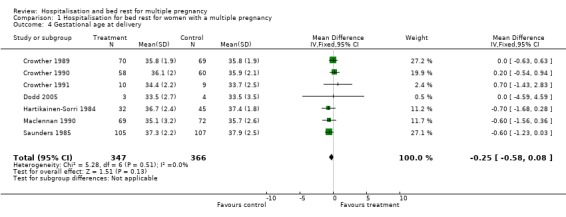

| 4 Gestational age at delivery | 7 | 713 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.25 [‐0.58, 0.08] |

| 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) | 7 | 713 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.86, 1.13] |

| 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks) | 5 | 424 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.91, 1.89] |

| 7 Birthweight twinI/triplet I | 4 | 417 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.02, 0.18] |

| 8 Birthweight twinII/triplet II | 4 | 417 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [‐0.02, 0.17] |

| 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | 7 | 1452 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.85, 1.00] |

| 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g) | 7 | 1452 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.77, 1.95] |

| 11 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes | 4 | 417 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.86, 2.28] |

| 12 Spontaneous onset of labour | 5 | 629 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [1.02, 1.09] |

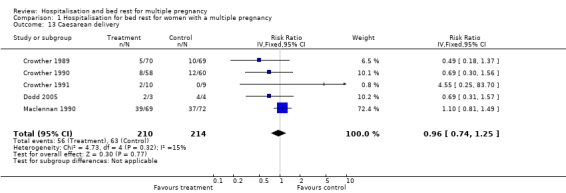

| 13 Caesarean delivery | 5 | 424 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.74, 1.25] |

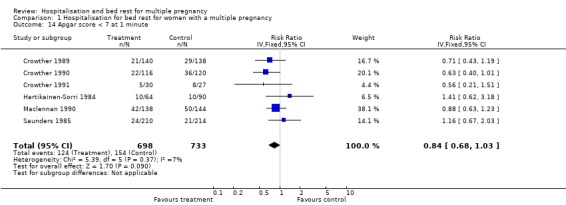

| 14 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute | 6 | 1431 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.68, 1.03] |

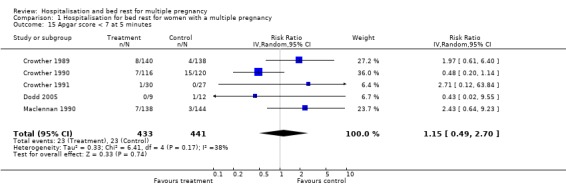

| 15 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.49, 2.70] |

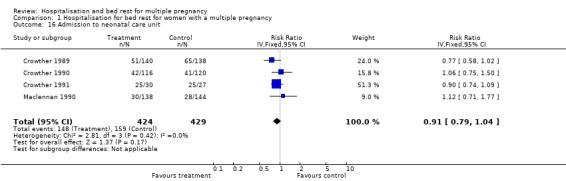

| 16 Admission to neonatal care unit | 4 | 853 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.79, 1.04] |

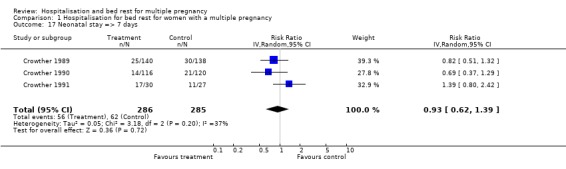

| 17 Neonatal stay => 7 days | 3 | 571 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.62, 1.39] |

| 18 Development of maternal hypertension | 7 | 713 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.43, 1.06] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 2 Stillbirth.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 3 Early neonatal death.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 4 Gestational age at delivery.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 7 Birthweight twinI/triplet I.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 8 Birthweight twinII/triplet II.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 11 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 12 Spontaneous onset of labour.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 13 Caesarean delivery.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 14 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 15 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 16 Admission to neonatal care unit.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 17 Neonatal stay => 7 days.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a multiple pregnancy, Outcome 18 Development of maternal hypertension.

Comparison 2. Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perinatal death | 4 | 1092 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.64 [0.45, 6.08] |

| 2 Stillbirth | 4 | 1096 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.17, 6.92] |

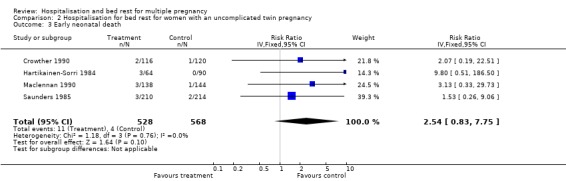

| 3 Early neonatal death | 4 | 1096 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.83, 7.75] |

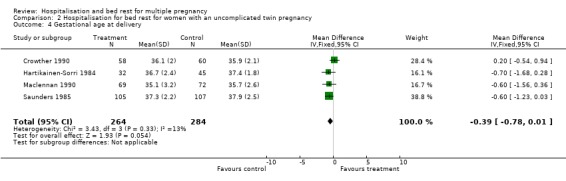

| 4 Gestational age at delivery | 4 | 548 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.39 [‐0.78, 0.01] |

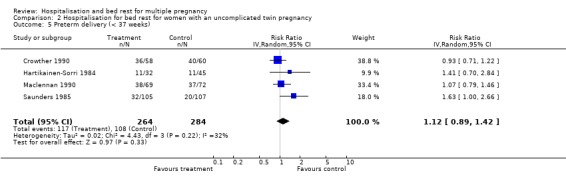

| 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) | 4 | 548 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.89, 1.42] |

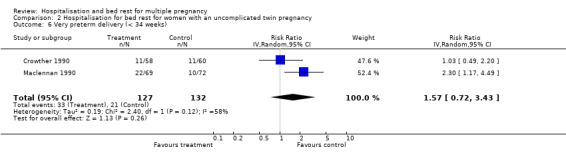

| 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks) | 2 | 259 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.57 [0.72, 3.43] |

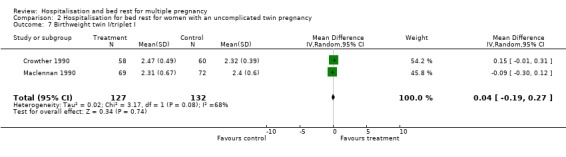

| 7 Birthweight twin I/triplet I | 2 | 259 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.19, 0.27] |

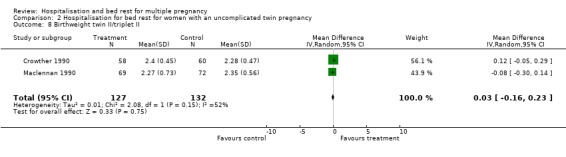

| 8 Birthweight twin II/triplet II | 2 | 259 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.16, 0.23] |

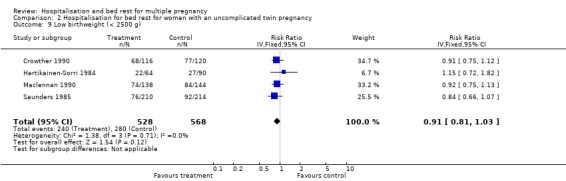

| 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | 4 | 1096 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.81, 1.03] |

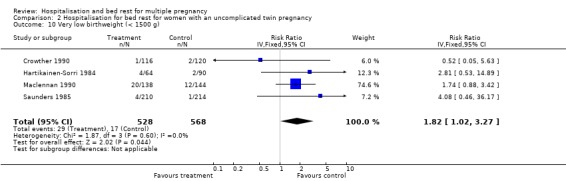

| 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g) | 4 | 1096 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [1.02, 3.27] |

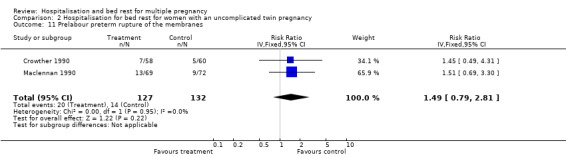

| 11 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes | 2 | 259 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.79, 2.81] |

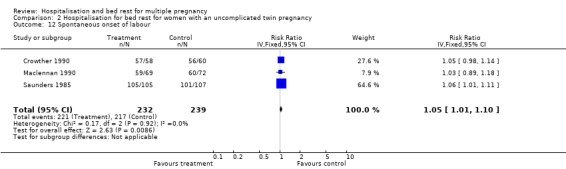

| 12 Spontaneous onset of labour | 3 | 471 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [1.01, 1.10] |

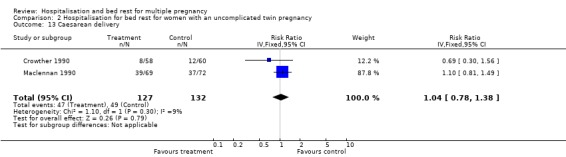

| 13 Caesarean delivery | 2 | 259 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.78, 1.38] |

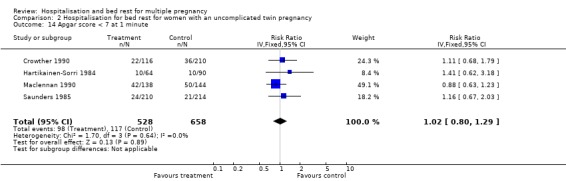

| 14 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute | 4 | 1186 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.80, 1.29] |

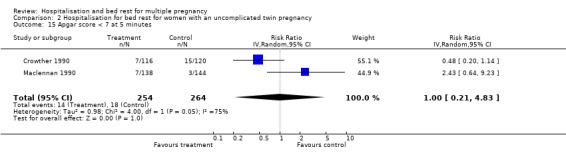

| 15 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 518 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.21, 4.83] |

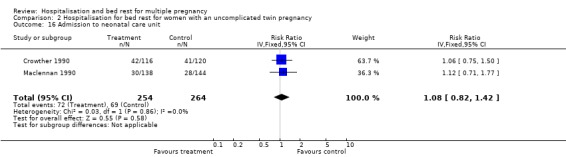

| 16 Admission to neonatal care unit | 2 | 518 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.82, 1.42] |

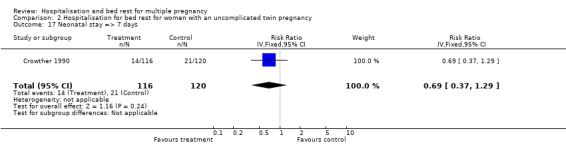

| 17 Neonatal stay => 7 days | 1 | 236 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.37, 1.29] |

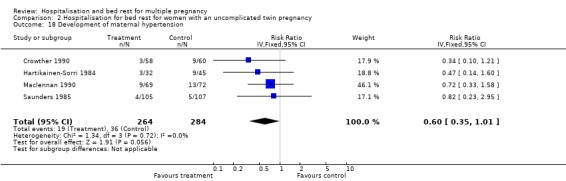

| 18 Development of maternal hypertension | 4 | 548 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.35, 1.01] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 2 Stillbirth.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 3 Early neonatal death.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 4 Gestational age at delivery.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 7 Birthweight twin I/triplet I.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 8 Birthweight twin II/triplet II.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 11 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 12 Spontaneous onset of labour.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 13 Caesarean delivery.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 14 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 15 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 16 Admission to neonatal care unit.

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 17 Neonatal stay => 7 days.

2.18. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with an uncomplicated twin pregnancy, Outcome 18 Development of maternal hypertension.

Comparison 3. Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

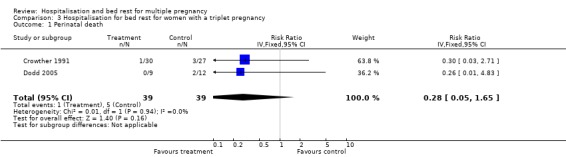

| 1 Perinatal death | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.05, 1.65] |

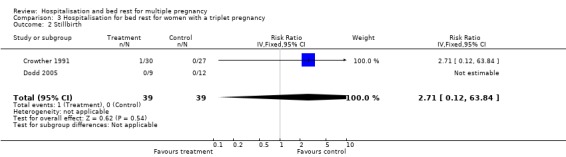

| 2 Stillbirth | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.71 [0.12, 63.84] |

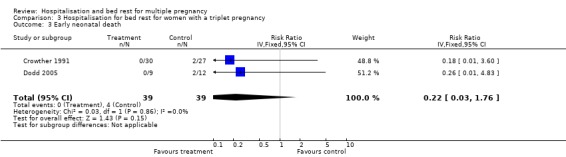

| 3 Early neonatal death | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.03, 1.76] |

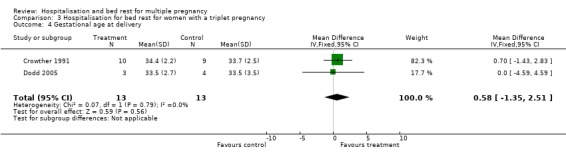

| 4 Gestational age at delivery | 2 | 26 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [‐1.35, 2.51] |

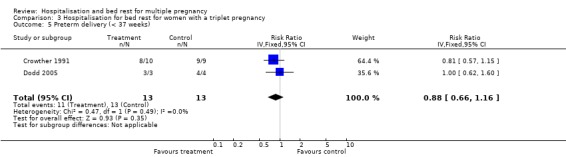

| 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) | 2 | 26 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.66, 1.16] |

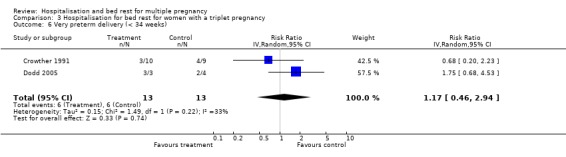

| 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks) | 2 | 26 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.46, 2.94] |

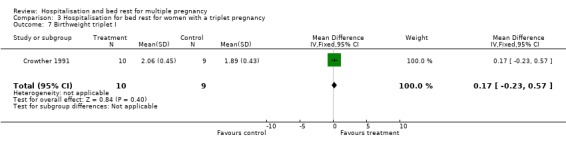

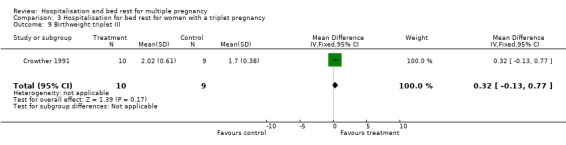

| 7 Birthweight triplet I | 1 | 19 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [‐0.23, 0.57] |

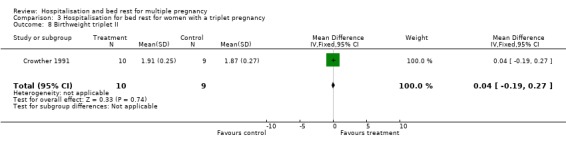

| 8 Birthweight triplet II | 1 | 19 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.19, 0.27] |

| 9 Birthweight triplet III | 1 | 19 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [‐0.13, 0.77] |

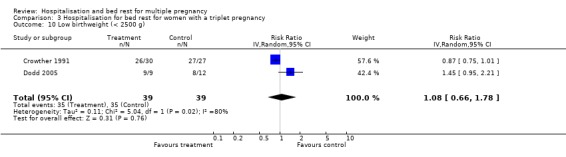

| 10 Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.66, 1.78] |

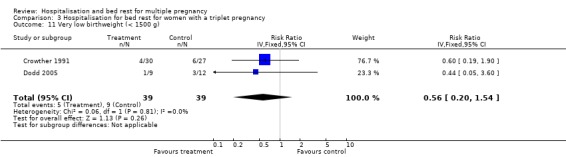

| 11 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g) | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.20, 1.54] |

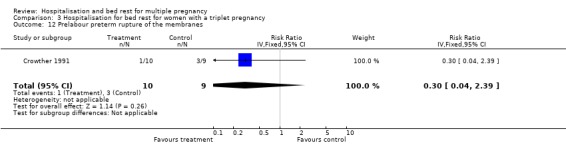

| 12 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.04, 2.39] |

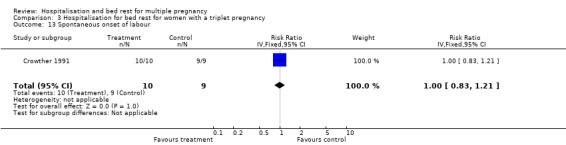

| 13 Spontaneous onset of labour | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.83, 1.21] |

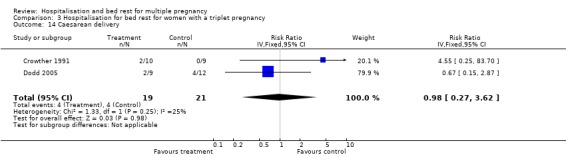

| 14 Caesarean delivery | 2 | 40 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.27, 3.62] |

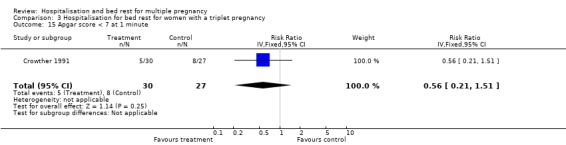

| 15 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.21, 1.51] |

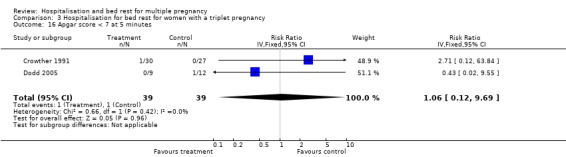

| 16 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 78 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.12, 9.69] |

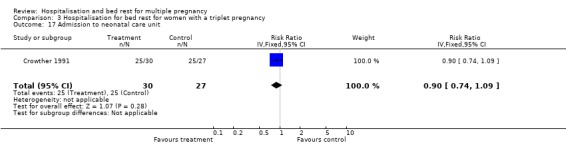

| 17 Admission to neonatal care unit | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.9 [0.74, 1.09] |

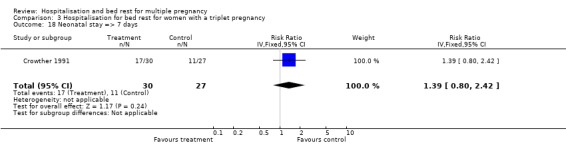

| 18 Neonatal stay => 7 days | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.80, 2.42] |

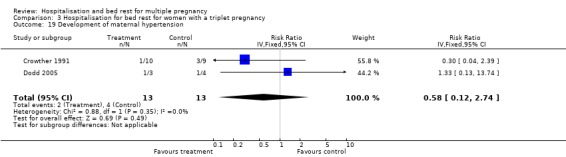

| 19 Development of maternal hypertension | 2 | 26 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.12, 2.74] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 2 Stillbirth.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 3 Early neonatal death.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 4 Gestational age at delivery.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 7 Birthweight triplet I.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 8 Birthweight triplet II.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 9 Birthweight triplet III.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 10 Low birthweight (< 2500 g).

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 11 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g).

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 12 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes.

3.13. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 13 Spontaneous onset of labour.

3.14. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 14 Caesarean delivery.

3.15. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 15 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

3.16. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 16 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

3.17. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 17 Admission to neonatal care unit.

3.18. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 18 Neonatal stay => 7 days.

3.19. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy, Outcome 19 Development of maternal hypertension.

Comparison 4. Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

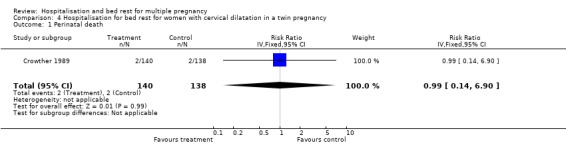

| 1 Perinatal death | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.14, 6.90] |

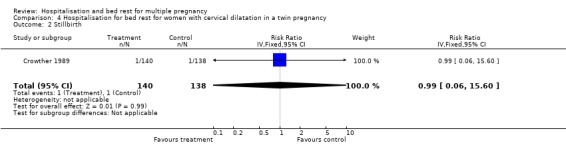

| 2 Stillbirth | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.06, 15.60] |

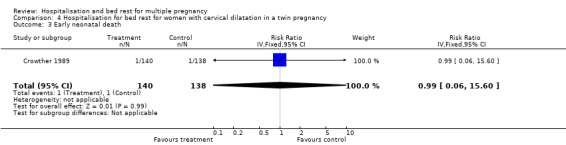

| 3 Early neonatal death | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.06, 15.60] |

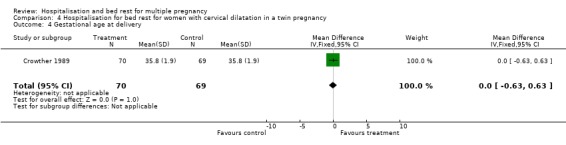

| 4 Gestational age at delivery | 1 | 139 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.63, 0.63] |

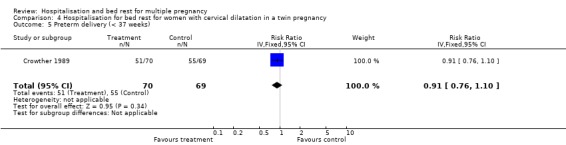

| 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) | 1 | 139 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.76, 1.10] |

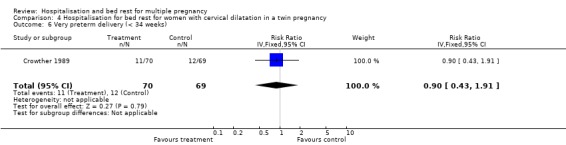

| 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks) | 1 | 139 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.43, 1.91] |

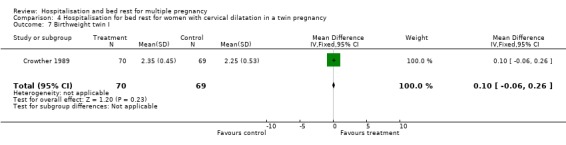

| 7 Birthweight twin I | 1 | 139 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.06, 0.26] |

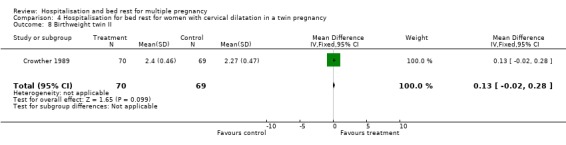

| 8 Birthweight twin II | 1 | 139 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [‐0.02, 0.28] |

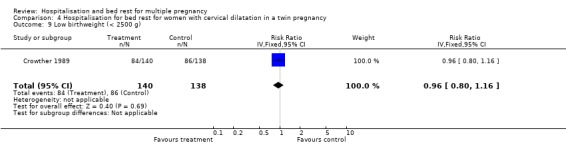

| 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.80, 1.16] |

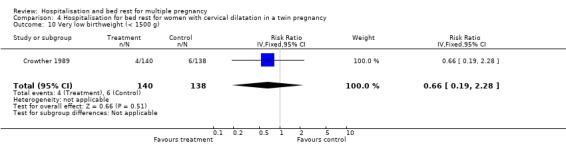

| 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g) | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.19, 2.28] |

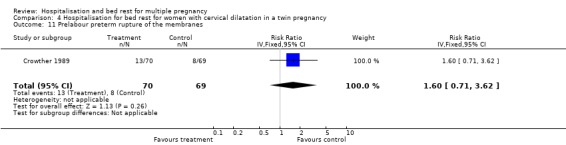

| 11 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes | 1 | 139 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [0.71, 3.62] |

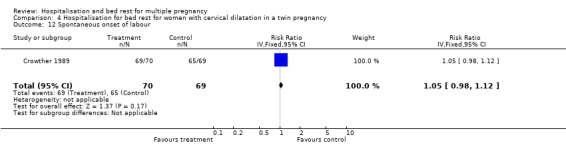

| 12 Spontaneous onset of labour | 1 | 139 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.98, 1.12] |

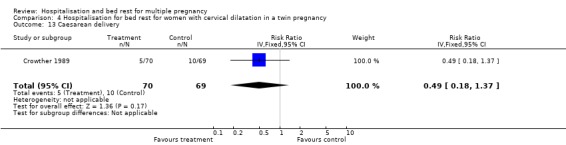

| 13 Caesarean delivery | 1 | 139 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.18, 1.37] |

| 14 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.43, 1.19] |

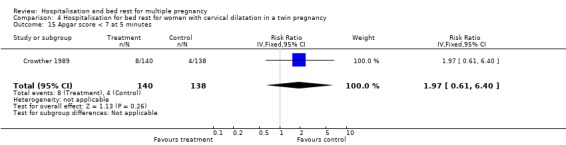

| 15 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.97 [0.61, 6.40] |

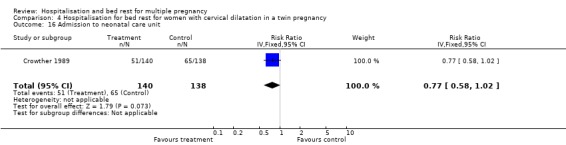

| 16 Admission to neonatal care unit | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.58, 1.02] |

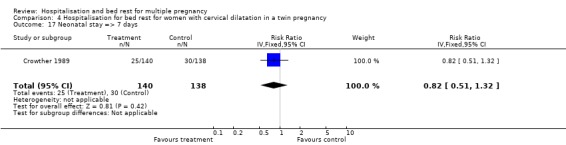

| 17 Neonatal stay => 7 days | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.51, 1.32] |

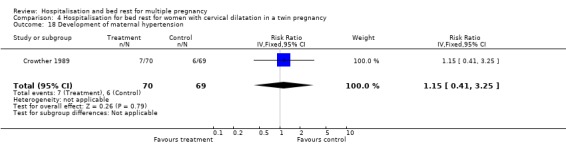

| 18 Development of maternal hypertension | 1 | 139 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.41, 3.25] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 2 Stillbirth.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 3 Early neonatal death.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 4 Gestational age at delivery.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 7 Birthweight twin I.

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 8 Birthweight twin II.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g).

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g).

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 11 Prelabour preterm rupture of the membranes.

4.12. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 12 Spontaneous onset of labour.

4.13. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 13 Caesarean delivery.

4.14. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 14 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

4.15. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 15 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

4.16. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 16 Admission to neonatal care unit.

4.17. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 17 Neonatal stay => 7 days.

4.18. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with cervical dilatation in a twin pregnancy, Outcome 18 Development of maternal hypertension.

Comparison 5. Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

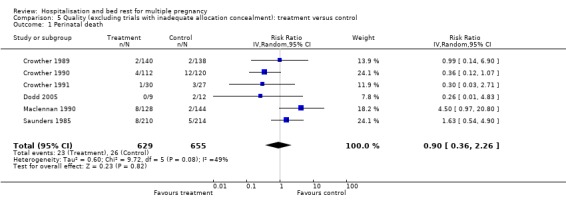

| 1 Perinatal death | 6 | 1284 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.36, 2.26] |

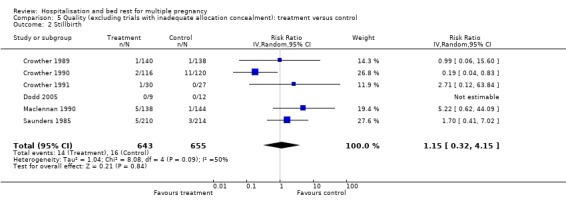

| 2 Stillbirth | 6 | 1298 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.32, 4.15] |

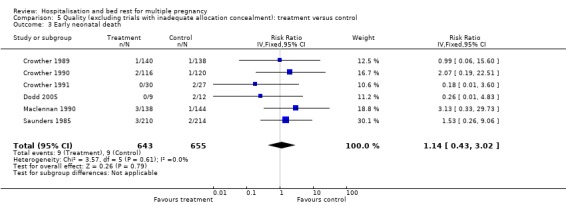

| 3 Early neonatal death | 6 | 1298 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.43, 3.02] |

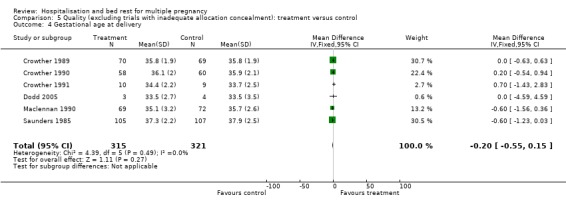

| 4 Gestational age at delivery | 6 | 636 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.55, 0.15] |

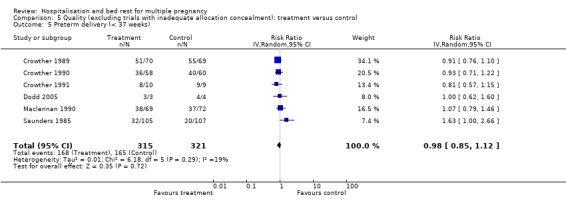

| 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) | 6 | 636 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.85, 1.12] |

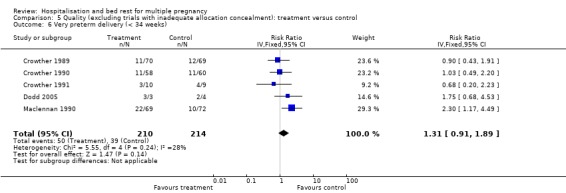

| 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks) | 5 | 424 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.91, 1.89] |

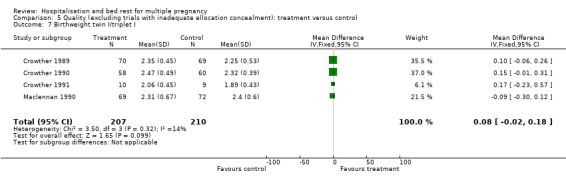

| 7 Birthweight twin I/triplet I | 4 | 417 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.02, 0.18] |

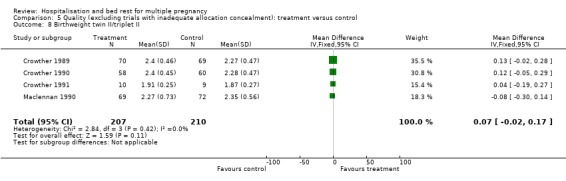

| 8 Birthweight twin II/triplet II | 4 | 417 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [‐0.02, 0.17] |

| 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | 6 | 1298 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.84, 1.00] |

| 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g) | 6 | 1298 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.70, 1.86] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 2 Stillbirth.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 3 Early neonatal death.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 4 Gestational age at delivery.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 5 Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 6 Very preterm delivery (< 34 weeks).

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 7 Birthweight twin I/triplet I.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 8 Birthweight twin II/triplet II.

5.9. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 9 Low birthweight (< 2500 g).

5.10. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Quality (excluding trials with inadequate allocation concealment): treatment versus control, Outcome 10 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Crowther 1989.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Single centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. No losses to follow up. |

|

| Participants | 139 women with a twin pregnancy with a cervical score of ‐2 or less on vaginal examination at or before 34 weeks' gestation, who attended a specialist antenatal clinic for multiple pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included uncertain gestational age, cervical suture in place, antepartum haemorrhage, hypertension, previous caesarean section and in labour. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to the hospitalisation group were admitted to the antenatal ward as soon after randomisation as convenient. Women were encouraged to rest in bed as much as possible, but ambulation was allowed. Women allocated to the control group were not routinely admitted and were encouraged to continue their normal activities at home. Women were selectively admitted if problems developed (preterm labour, hypertension, preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes). | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: gestational age at delivery (Dubowitz assessment by paediatrician blinded to treatment allocation), birthweight, need for admission to neonatal intensive care unit. Other neonatal morbidity, perinatal mortality, maternal morbidity. | |

| Notes | Sample size of 44 women would have an 80% chance of detecting a reduction in rate of preterm delivery from 80% to 40% at the 5% level. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Block randomisation by opening 'consecutively, opaque, sealed envelopes'. Randomisation schedule was prepared by a researcher not involved in treatment allocation. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes were used. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes on gestational age and newborn infants were assessed by a paediatrician blinded to treatment allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | There were no losses to follow up. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No obvious risk of other bias. |

Crowther 1990.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Single centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. No exclusions. No losses to follow up. | |

| Participants | 118 women with a twin pregnancy at 28‐30 weeks' gestation who attended a specialist antenatal clinic for multiple pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included uncertain gestational age, cervical suture in place, antepartum haemorrhage, hypertension, or previous caesarean section. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to the hospitalisation group were admitted to the antenatal ward as soon after randomisation as convenient. Women were encouraged to rest in bed as much as possible, but ambulation was allowed. Women allocated to the control group were not routinely admitted and were encouraged to continue their normal activities at home. Women were selectively admitted if problems developed (hypertension, preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes, preterm labour). | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: gestational age at delivery (Dubowitz assessment by paediatrician blinded to treatment allocation), birthweight, need for admission to neonatal intensive care unit. Other neonatal morbidity, perinatal mortality. Maternal morbidity. | |

| Notes | Sample size of 100 women would detect a reduction in rate of preterm delivery from 55% to 28%. 200 women would be needed to detect a reduction in the risk of small‐for‐gestational‐age infants from 35% to 17.5%. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Block randomisation by opening 'consecutively, opaque, sealed envelopes'. Randomisation schedule was prepared by a researcher not involved in treatment allocation. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes were used. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessment of gestational age by a paediatrician blinded to treatment allocation. The other primary measures of outcome (birthweight and need for admission to the neonatal unit) were measurements or decisions taken by staff blinded to treatment allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow up. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No obvious risk of other bias. |

Crowther 1991.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Single centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. No losses to follow up. | |

| Participants | 19 women with a triplet pregnancy at 24 weeks' gestation or more who attended a specialist antenatal clinic for multiple pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included uncertain gestational age, cervical suture in place, antepartum haemorrhage, hypertension, or previous caesarean section. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to the hospitalisation group were asked to attend the antenatal ward as soon after recruitment as possible. Women were encouraged to rest in bed as much as possible, but ambulation was allowed. Women allocated to the control group were not routinely admitted and were encouraged to continue their normal activities at home. Women were selectively admitted if problems developed (hypertension, preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes, preterm labour). | |

| Outcomes | Gestational age at delivery (Dubowitz assessment by paediatrician blinded to treatment allocation), birthweight, other neonatal morbidity, perinatal mortality, maternal morbidity. | |

| Notes | No pretrial sample size calculation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Block randomisation by opening 'consecutively, opaque, sealed envelopes'. Randomisation schedule was prepared by a researcher not involved in treatment allocation. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes were used. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessment of gestational age and newborn infants by a paediatrician blinded to treatment allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow up. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No obvious risk of other bias. |

Dodd 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Single centre in Adelaide, Australia. No losses to follow up and no post‐randomisation exclusion. Analysis based on an intention‐to‐treat basis. |

|

| Participants | 7 women with a triplet pregnancy, with ultrasound confirmed gestation age of less than 24 weeks at trial entry. No other condition necessitating hospital admission. Exclusion criteria included women with a triplet pregnancy and any other condition requiring hospitalisation (e.g. placenta praevia). |

|

| Interventions | The hospitalisation group: women were admitted to hospital from 24 weeks' gestation until 30 weeks' gestation, after which time, women were discharged home and encouraged to obtain as much rest as possible. All women were able to ambulate within the hospital, receive a normal hospital diet, and fortnightly routine antenatal assessment. Women were allowed leave from the ward over weekend periods to assist compliance with continued hospitalisation. The control group: women were encouraged to continue with their normal activities at home, and were reviewed fortnightly in the antenatal clinic. They were admitted to hospital if any complications developed, such as preterm labour, preterm prelabour ruptured membranes and pregnancy‐induced hypertension. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: incidence of preterm birth (defined as birth less than 37 weeks' gestation) and very preterm birth (defined as birth less than 34 weeks' gestation), and the development of maternal pregnancy‐induced hypertension (defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg OR an increase in the diastolic blood pressure of more than 15 mmHg from booking). Secondary outcomes: tocolytic use, mode of birth, infant Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes, infant birthweight less than 2500 grams, infant birthweight less than 1500 grams, admission to the neonatal unit, length of stay in the neonatal unit more than 7 days, perinatal death (stillbirth and neonatal death) and the occurrence of neonatal morbidity (including respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular haemorrhage, and necrotising enterocolitis). |

|

| Notes | Sample size of 400 women would have an 80% chance of detecting a reduction in rate of preterm birth less than 34 weeks' gestation from 44% to 30% at the 5% level. Sample size of 52 women would have an 80% chance of detecting a reduction in the risk of preterm birth less than 37 weeks' gestation from 100% to 80% at the 5% level. The results of this study were incorporated into a systematic review and meta‐analysis with a previous trial of hospitalisation and bed rest for women with triplet pregnancy, a total sample size of 26 women and 78 infants were obtained. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomisation schedule used variable blocks with stratification by parity. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A researcher not involved in clinical care contacted by telephone to determine treatment allocation by opening the next in a series of consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information given on blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow up. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | High risk | Recruitment stopped before achieving the calculated sample size due to difficulties in recruitment. |

Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984.

| Methods | Quasi‐randomised trial. Single centre, Oulu, Finland. Exclusions 8%. | |

| Participants | 73 women with a twin pregnancy, confirmed by ultrasound, attending outpatient clinic. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to bed rest were admitted to hospital for rest after the 29th week of gestation. Women allocated to the control group were seen weekly in the specialised antenatal clinic. Selective admission if in preterm labour, fetal distress developed or hypertension. | |

| Outcomes | Gestational age at delivery, birthweight, perinatal mortality, fetal distress, maternal hypertension. | |

| Notes | 1 set of conjoined twins excluded from the bed rest group. Additional data kindly provided by Dr Anna‐Liisa Hartikainen‐Sorri. No sample size given. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | Randomisation by odd/even year of birth. |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | A quasi‐randomised trial. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information given on blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | No information given on the 5 women who were excluded. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | A quasi‐randomised trial. |

Maclennan 1990.

| Methods | Randmised controlled trial. Multi‐centred, 11 hospitals in Australia. No exclusions. | |

| Participants | 141 women with twin pregnancy, confirmed by ultrasound. Randomised between 16‐19 weeks' gestation. Exclusion criteria: not able to be admitted, pre‐existing hypertension, polyhydramnios, antepartum haemorrhage, preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes, preterm labour. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to bed rest were admitted at 26 weeks' gestation for 4 weeks. Weekend leave was allowed. Strict bed rest was not advocated. Women allocated to the control group were not routinely admitted but seen in the clinic every 2 weeks. Normal home activities were encouraged. | |

| Outcomes | Gestational age at delivery, birthweight, need for admission and length of stay on the neonatal ward. Women's views of care. | |

| Notes | Sample size 400 women in each arm to detect differences in mortality and major handicap. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | By using of a computer‐generated list of random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: "a random allocation of management was given to the clinician in charge from a computer‐generated list of random numbers; the person designating the management was unaware of the management associated with the number until after enrolment". |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information given on blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessment was based on intention‐to‐treat basis. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No obvious risk of other bias. |

Saunders 1985.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Single centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. No losses to follow up reported. |

|

| Participants | 212 women with a twin pregnancy attending the antenatal clinic. Randomised (usually 30 weeks) at their last antenatal visit before admission at 32 weeks' gestation. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to bed rest in hospital were admitted for bed rest at 32 weeks' gestation until the onset of labour. Women allocated to the control group were not routinely admitted to hospital. Selective admission only for complications. | |

| Outcomes | Gestational age at delivery, birthweight, perinatal mortality, hypertension. | |

| Notes | 100 women in each arm had a 40% chance of detecting a reduction in the risk of preterm delivery before 37 weeks' gestation by one‐third, from 30% to 20%. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randmisation by referring to a consecutively numbered series of sealed envelopes. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information given on whether the envelopes used for randomisation were opaque or not. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Assessment of duration of gestation at delivery was made by labour‐ward staff blinded to group allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow up reported. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No obvious risk of selective reporting. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No obvious risk of other bias. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Gummerus 1985 | This randomised trial of 200 women in Finland compared the effects on gestation at birth and birthweight of long‐term betamimetic therapy given to women with a multiple pregnancy after admission to hospital for bed rest with no betamimetic therapy. All women were admitted to hospital for bed rest and the trial therefore did not meet the criteria for inclusion. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

al‐Najashi 1996.

| Methods | Single centre in The King Fahd Hospital of the university, Al‐Khobar, Saudi Arabia. No information on group allocation method. |

| Participants | 189 women with uncomplicated twin pregnancy. Women with complicated pregnancy (e.g. women with hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease or had antepartum haemorrhage) were excluded. |

| Interventions | Women in bed rest group 1: receiving prophylactic oral ritodrine 10 mg 3 times a day starting from the 25th week until the end of the 37th week of gestation. No restriction in any activities. Women in bed rest group 2: hospitalised from the 28th to the 32nd week of gestation. Women in the control group: no medication or hospitalisation for bed rest, but were seen regularly in the outpatient clinic until delivery. No restriction in any activities. |

| Outcomes | Gestational age at delivery, birthweight, caesarean section rate, perinatal mortality. |

| Notes |

Younis 1990.

| Methods | Single centre in Hadassah Hospital, Ein Karem. No information given on group allocation method. |

| Participants | 151 women with twin pregnancy, born after 32 weeks' gestation were included. Women suffering from complications of pregnancy affecting time of delivery, e.g. hypertensive disorders, Antepartum bleeding, premature uterine contractions were excluded. |

| Interventions | Women in bed rest group were electively hospitalised from the 30‐32 weeks of gestation, and if not delivered, until the end of 36 weeks of gestation. Women in control group 1 were not prophylactically hospitalised but instructed to rest at home. Women in control group 2 were not routinely hospitalised and were not instructed to remain at home. |

| Outcomes | Gestational age at birth, birthweight, perinatal mortality, caesarean section, Apgar score at 5 minutes. |

| Notes |

Contributions of authors

CA Crowther contributed to the development of the protocol, identification and selection of studies for inclusion, data extraction and preparation of the text of the previous review. Both review authors (CA Crowther and S Han) contributed to the final version of this updated review. For this update, CA Crowther and S Han assessed identified studies for eligibility and risk of bias. Both review authors (CA Crowther and S Han) contributed to data extraction and data entry for this update, S Han prepared the initial draft of the risk of bias tables, and both review authors have prepared the text of this updated review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Adelaide, Australia.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

CA Crowther was chief investigator on four of the trials included in this review.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Crowther 1989 {published data only}

- Crowther CA, Neilson JP, Verkuyl DAA, Bannerman C, Ashurst HM. Preterm labour in twin pregnancies: can it be prevented by hospital admission?. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1989;96:850‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crowther 1990 {published data only}

- Crowther CA, Verkuyl DAA, Neilson JP, Bannerman C, Ashurst HM. The effects of hospitalization for rest on fetal growth, neonatal morbidity and length of gestation in twin pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990;97:872‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crowther 1991 {published data only}

- Crowther CA, Verkuyl D, Ashworth M, Bannerman C, Ashurst H. The effects of hospitalisation for bed rest on duration of gestation, fetal growth and neonatal morbidity in triplet pregnancy. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae 1991;40:63‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dodd 2005 {published data only}

- Dodd JM, Crowther CA. Hospitalisation for bed rest for women with a triplet pregnancy: an abandoned randomised controlled trial with meta‐analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2005;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hartikainen‐Sorri 1984 {published and unpublished data}

- Hartikainen‐Sorri AL, Jouppila P. Is routine hospitalization needed in antenatal care of twin pregnancy?. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 1984;12:31‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maclennan 1990 {published data only}

- MacLennan AH, Green RC, O'Shea R, Brookes C, Morris D. Routine hospital admission in twin pregnancy between 26 and 30 weeks' gestation. Lancet 1990;335:267‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saunders 1985 {published data only}

- Saunders MC, Dick JS, Brown I McL, McPherson K, Chalmers I. The effects of hospital admission for bed rest on the duration of twin pregnancy: a randomised trial. Lancet 1985;2:793‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Gummerus 1985 {published data only}

- Gummerus M, Halonen O. Prophylactic long‐term oral tocolysis of multiple pregnancies. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1987;94(3):249‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummerus M, Halonen O. The merits of betamimetic treatment and bed rest in multiple pregnancies [Vuodelevon ja beetasympatomimeetthoidon vaikutus monisikioisessa raskaudessa]. Duodecim 1985;101:1966‐71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

al‐Najashi 1996 {published data only}

- al‐Najashi SS, al‐Mulhim AA. Prolongation of pregnancy in multiple pregnancy. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 1996;54(2):131‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Younis 1990 {published data only}

- Younis JS, Sadovsky E, Eldar‐Geva T, Mildwidsky A, Zeevi D, Zajicek G. Twin gestations and prophylactic hospitalization. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 1990;32(4):325‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Crowther 2005

- Crowther CA, Dodd JM. Multiple pregnancy. In: James D, Steer P, Weiner C, Gonik B editor(s). High risk pregnancy. 3rd Edition. Elsevier, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2001

- Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta‐analysis. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG editor(s). Systematic reviews in health care: meta‐analysis in context. London: BMJ Books, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Houlton 1982

- Houlton MCC, Marivate M, Philpott RHP. Factors associated with preterm labour and changes in the cervix before labour in twin pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1982;89:190‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McKeown 1952

- McKeown T, Record R. Observation on fetal growth in multiple pregnancy in man. Journal of Endocrinology 1952;8:386‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neilson 1988