Ocrelizumab is a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody targeting B cells, which is authorized for relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and active primary progressive MS. Here, we report, to the best of our knowledge, the first case of infective endocarditis in a patient treated with ocrelizumab.

Case report

A 43-year-old man was admitted due to clinical deterioration within the last 4 weeks. He complained about worsening of gait and progressive weakness, aggravated double vision, and night sweats. The patient had a history of highly active RRMS with a disease course of 3 years and an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 4.5. He had been treated with glatiramer acetate and was switched to ocrelizumab 17 months before the current admission due to progressive paraparesis of the legs (EDSS score 3.0). Despite treatment with 3 cycles of ocrelizumab (CD19/CD20 cells were fully depleted 7 weeks before the onset of symptoms), there was further clinical progression (EDSS score 4.5). In addition, he was treated with intrathecal triamcinolone 9 months prior this presentation. Apart from arterial hypertension, the patient had no other underlying condition.

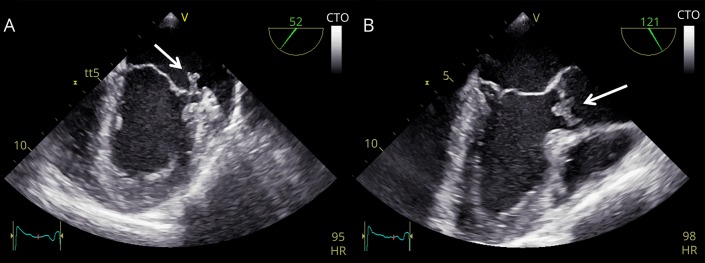

On admission, he presented with a predominant left-sided spastic tetraparesis with spastic-ataxic gait. Routine diagnostic workup revealed an increased body temperature of 38°C, elevated leukocytes of 10,060/μL (normal 4,600–9,500), and a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 50.3 mg/L (<5.0). Clinically, there was no evident focus of the presumed infection. He was therefore treated with an empiric antibiotic regime using ceftriaxone. Chest x-ray and sonography of the abdomen were unremarkable. Blood cultures revealed an infection with Enterococcus faecalis. Hence, infective endocarditis was assumed, and antibiotic therapy was switched to gentamicin along with ampicillin. However, because transesophageal echocardiography revealed no signs of endocarditis, the antibiotic therapy was de-escalated to piperacillin/tazobactam for 7 days, resulting in gradual clinical improvement and regression of CRP values. On discharge, the body temperature was normal. Fifteen days later, he presented again due to elevated body temperature (38.5°C). Blood testing revealed re-elevation of leukocytes (10,680 leukocytes/μL) and CRP (84.7 mg/L). Now, transesophageal echocardiography exhibited aortic valve vegetations (5 × 5 mm) with moderate regurgitation and mitral valve vegetations (4 × 10 mm) with perforation of the posterior leaflet and moderate regurgitation (figure and Video 1). The patient was immediately re-treated with gentamicin and ampicillin, leading to gradual improvement over the following weeks.

Figure. Transesophageal echocardiography.

(A) The view of the mitral valve revealed an endocarditic lesion of the posterior mitral valve leaflet (white arrow). In addition, a perforation of the leaflet was seen. (B) On the aortic valve, an endocarditic lesion appeared (white arrow), which was also associated with a regurgitation jet. CTO = Continuous Tissue Optimization; HR = heart rate; LA = left atrium; LAA = left atrial appendage; LV = left ventricle.

The view of the mitral valve revealed an endocarditic lesion of the posterior mitral valve leaflet. In addition, a perforation of the leaflet was seen. On the aortic valve, an endocarditic lesion appeared (white arrow), which was also associated with a regurgitation jet. Video is shown in slow motion (0.25×).Download Supplementary Video 1 (4.5MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/000680_Video_1

Discussion

Here, we present the first case of infective endocarditis following ocrelizumab therapy. Ocrelizumab was investigated in 2 pivotal phase 3 clinical trials in RRMS and in 1 trial in primary progressive MS. In the OPERA I and II clinical trials, therapy with ocrelizumab reduced the relapse rate by 46% compared with interferon beta-1a and disability progression (hazard ratio 0.6, 95% CI, 0.43–0.84; p = 0.003) in patients with RRMS1 and disability progression after 12 weeks in the ORATORIO trial in patients with primary progressive MS by 24%.2 Side effects, reported in the trials, include infusion-related reactions in about 30% of the patients and infections1 such as nasopharyngitis (22.6% ocrelizumab and 27.2% placebo), urinary tract infection (19.8% vs 22.6%), influenza (11.5% vs 8.8%), and upper respiratory tract infections.2 In the phase 3 trials conducted in rheumatoid arthritis, ocrelizumab combined with methotrexate (MTX) induced more serious infections than placebo (ocrelizumab 500 mg + MTX 6.1% vs 3.1% MTX + placebo group) with a higher risk for patients recruited in Asia.3 Until now, infective endocarditis has not been reported in association with ocrelizumab therapy.

However, endocarditis has occurred in B cell–depleted patients following rituximab treatment, another B cell–depleting antibody. For example, 1 patient with damaged valves due to Libman-Sacks endocarditis more than 20 years before treatment with rituximab developed endocarditis with Streptococcus intermedius.4 By contrast, there was no previous history of underlying heart disease, which could have facilitated the development of endocarditis in our patient. Pathomechanistically, it could be speculated that a depletion of innate-like B cells such as B1 cells, critical for the primary immune response5 and involved in local reaction during infection,6 might have facilitated the infection with E faecalis in this patient. Although not investigated in this patient, low immunoglobulin levels could have contributed to the infection.

In summary, we present the first case of infective endocarditis in a patient treated with ocrelizumab. Although infective endocarditis seems to be a rare complication following ocrelizumab therapy, treating physicians should be aware of this rare and previously unreported side effect of ocrelizumab in patients with otherwise unexplained recurrent episodes of fever and laboratory signs of systemic inflammation under treatment with ocrelizumab.

Acknowledgment

The authors received written informed consent from the patient regarding anonymous publication of this case report.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

There was no specific funding. The authors acknowledge support by the DFG Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Disclosure

S. Faissner received travel grants from Biogen Idec and speaker or board honoraria from Celgene and Novartis, not related to the content of this manuscript. C. Schwake has nothing to report. M. Gotzmann received travel grants from Bayer and Novartis and speaker or board honoraria from Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer, not related to the content of this manuscript. A. Mügge received speaker or board honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer, not related to the content of this manuscript. S. Schmidt received travel grants and speaker as well as board honoraria from Bayer Schering, Biogen, Genzyme, Roche, Novartis, Merck Serono, and Teva. R. Gold received speaker's and board honoraria from Baxter, Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec, CLB Behring, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Stendhal, Talecris, and Teva. His department received grant support from Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva. All not related to the content of this manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery P, Rigby W, Tak PP, et al. Safety with ocrelizumab in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the ocrelizumab phase III program. PLoS One 2014;9:e87379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong D, Wright S, McVeigh C, Finch M. Infective endocarditis complicating rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) treatment in an SLE patient with a past history of Libman-Sacks endocarditis: a case for antibiotic prophylaxis? Clin Rheumatol 2006;25:583–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grasseau A, Boudigou M, Le Pottier L, et al. Innate B cells: the archetype of protective immune cells. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol Epub 2019 June 10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Choi YS, Baumgarth N. Dual role for B-1a cells in immunity to influenza virus infection. J Exp Med 2008;205:3053–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The view of the mitral valve revealed an endocarditic lesion of the posterior mitral valve leaflet. In addition, a perforation of the leaflet was seen. On the aortic valve, an endocarditic lesion appeared (white arrow), which was also associated with a regurgitation jet. Video is shown in slow motion (0.25×).Download Supplementary Video 1 (4.5MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/000680_Video_1