Abstract

PURPOSE

We aimed to assess the safety and effectiveness of a modified low-profile hangman technique.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective review of all filter retrieval procedures performed at a major trauma center, from 2012 to 2019. Records were reviewed for patient demographics, device type, device dwell time, device tilt, embedded hook, success of device retrieval, evidence of caval injury and occurrence of complications.

RESULTS

From 2012 to 2019 there were 473 filter retrieval attempts. An advanced technique was documented in 66 (14%). The low-profile hangman technique alone was documented in 23 procedures (5% of all procedures, 35% of advanced technique procedures). Average screening time was 28 minutes. At the time of retrieval attempt, 9 patients (41%) were anticoagulated. The hangman technique was employed as isolated maneuver in 23 patients and was successful on initial attempt in 22 cases (96%). The average dwell time of filters retrieved by the hangman technique was 228 days (range, 40–903 days; median, 196 days). No procedure-related complications occurred.

CONCLUSION

The retrieval of IVC filters is an important part of offering an IVC filter service. Advanced techniques to retrieve caval filters are multiple, and the risk of complications is increased in these cases. We demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of a new modified and lower-profile hangman technique. This new technique could be performed with only an 11 French venous access sheath using off-the-shelf equipment and it remains a cost-effective approach to complex filter retrieval.

Potentially retrievable inferior vena cava (IVC) filters have been in use in clinical practice since the early 2000s (1). Prolonged filter dwell times have been associated with increased difficulty of retrievability and potential complications relating to IVC stenosis or occlusion (2–5). Adding to this, while evidence supports the benefit of IVC filters in decreasing recurrent pulmonary embolism in the short term, there may be no difference in the long-term survival of patients with and without long-term caval interruption (5–7). It is good practice therefore, that all patients with potentially retrievable IVC filters should have an attempt made at filter retrieval as soon as no longer clinically indicated.

Many factors contribute to the success or failure of retrieval and associated complications, and these include, but are not limited to, filter dwell time, brand/design, embedded hook, and strut penetration (8, 9). Major complications associated with filter retrieval are infrequent; however, the use of advanced retrieval techniques has been shown to increase the retrieval complication rate including filter fracture and IVC injury (10–13). Different advanced techniques have been described including loop-snare, balloon-assisted, and endobronchial forceps among many others, and almost all of these techniques require venous access sheaths that are larger than those used for standard retrievals (9).

The benefit of retrieval for challenging filters, must be weighed between the risk of leaving them in situ and the risk of removal, both of which have reasonable arguments and many cases will be patient dependent (2). Despite the associated complication rates, advanced retrieval techniques may be preferable to the risks associated with leaving a filter in place permanently, especially in younger patients or those who desire pregnancy (1). Interventional radiologists need therefore to be prepared to perform both standard and advanced, complex filter retrievals if offering an IVC filter service. In 2015, Al-Hakim et al. (14) described a novel concept which uses a modified loop-snare technique to retrieve filters with an embedded hook. Since around that time, we have adopted this technique but modified to use the standard Cook Gunther-tulip retrieval kit, which is of smaller caliber and available on the shelf in many interventional radiology practices. We describe the feasibility, safety, and success rate of consecutive complicated IVC filter retrievals, where we have used the modified hangman technique as an isolated retrieval maneuver (15).

Methods

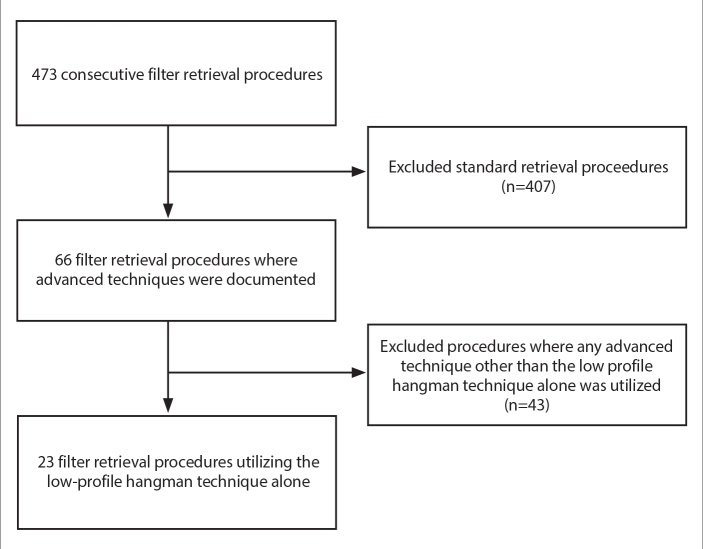

Ethical approval was granted by the local institutional ethics committee (81/19, 29/01/2019) who waived the need for informed consent. We performed a retrospective review of all filter retrieval procedures performed at a tertiary referral center and major trauma center, from 2012 to 2019. Patients were identified using the hospital picture archiving and communication system (PACS) system. Imaging studies and radiology reports were reviewed for patients undergoing IVC filter removal using the hangman technique at our institution. Records were reviewed for patient demographics, device type, device dwell time, device tilt, embedded hook, success of device retrieval, evidence of caval injury, and occurrence of complications. Final inclusion criteria included all consecutive filter retrieval procedures where the hangman technique was used in isolation, subsequent to failing the standard basic retrieval technique. All filter types were included. Exclusion criteria included those procedures where an advanced technique was not used and those procedures where more than one advanced technique was used during the same procedure (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion flow chart.

Filter removal technique

The specifics of the hangman technique used to remove IVC filters is described by Clements et al. (15), and was performed as follows: Intravenous conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl was utilized in the majority of cases (n=16); however, some were performed under general anesthesia (n=6) at the discretion of the operator (for example, failed basic retrieval with long procedure time or pain at initial retrieval and a re-booking made for advanced technique under general anesthetic). All filter removal procedures were performed by using a right internal jugular vein approach. The Cook Gunther-Tulip IVC filter retrieval kit was used for all cases, which consisted of a telescoping 11 French (F) 80 cm sheath system (Cook Medical), which was advanced over a fixed core 0.035-inch J-wire (Cook Medical) until the sheath tip was situated caudal to the filter. An initial digital subtraction angiographic (DSA) cavogram was performed through the Cook retrieval sheath, prior to attempted removal of all filters to identify anterior-posterior tilt, penetration of hook and/or legs, relationship to the renal veins, and best working angle to identify the embedded hook (Fig. 2). A 5 F Sos Omni catheter (Angiodynamics) was formed around the neck of the IVC filter (Fig. 3). A 260 cm 0.018-inch straight-tipped fixed-core wire (TSF-018-260, Cook Medical) was passed through the Sos Omni catheter around the neck of the filter (care was taken not to engage the filter struts) to form a loop, with tip of the wire positioned in the juxta/suprarenal IVC. The Sos Omni catheter was then removed and the snare provided in the Cook filter retrieval kit was used to snare the wire (Fig. 4). The snare and wire were then pulled back through the sheath and removed so that the wire was now looped around the neck of the filter (Fig. 5a), and both the front and back ends of the wire were outside the sheath. Gentle traction was applied to both ends of the wire simultaneously, usually with an artery forceps to grip the wire as it exited the sheath. This allowed straightening of the filter and the retrieval sheath to be advanced in short repetitive movements to separate the hook from the wall.

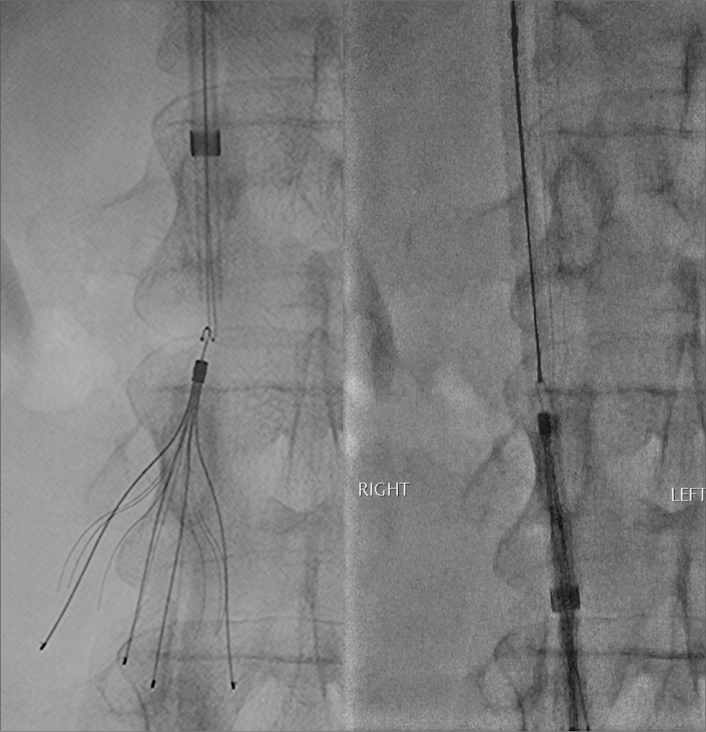

Figure 2.

Initial digital subtraction angiographic (DSA) cavogram was performed through the Cook retrieval sheath, prior to attempted removal of a filter. Filter tilt and an embedded hook is identified in this case on DSA.

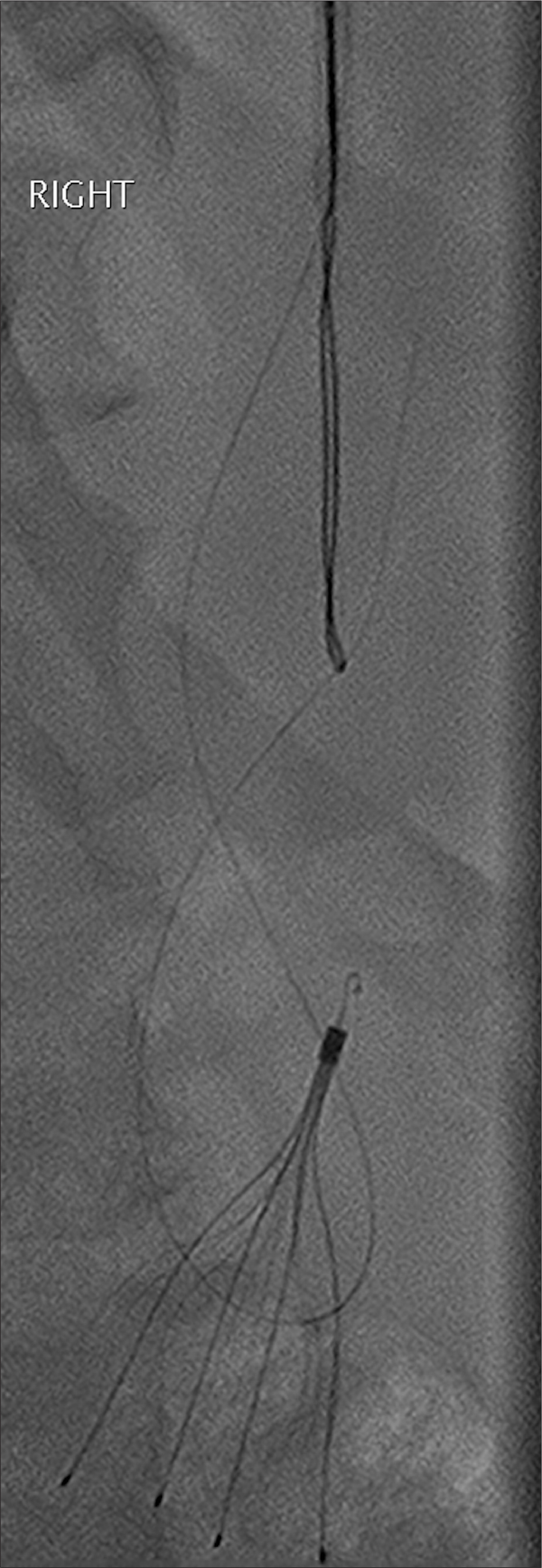

Figure 3.

A 0.018-inch fixed core wire (Cook Medical) is directed around the neck of the IVC filter, taking care not to engage the filter struts, and the end is snared using the snare provided in the Cook filter retrieval kit (Cook Medical).

Figure 4.

The snare and snared end of the 0.018- inch wire were pulled back through the sheath and removed. The 0.018-inch fixed core wire is now looped around the neck of the filter.

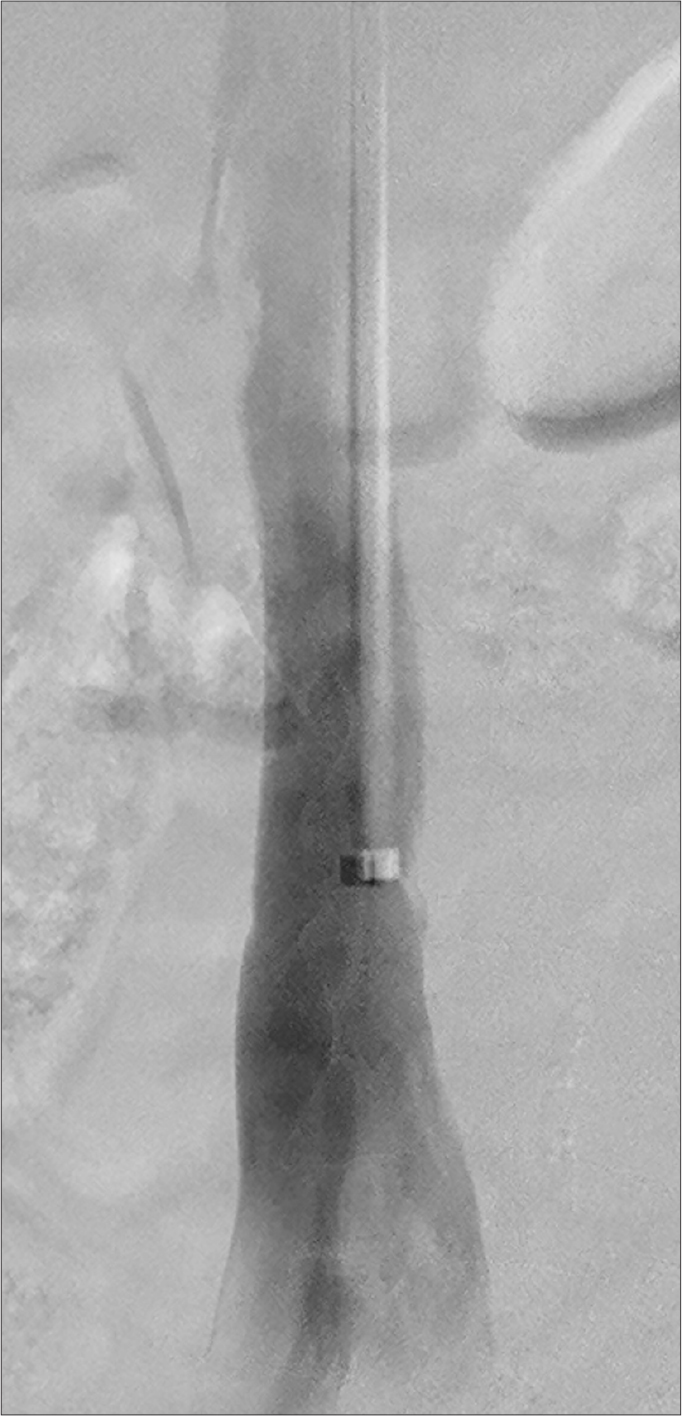

Figure 5.

With forward pressure on the sheath and gentle retraction on the 0.018-inch fixed core wire ends, the sheath is then advanced over the hook and filter in the standard manner.

With forward pressure on the sheath and very gentle counter traction on the 0.018-inch wire ends, the sheath was then advanced over the hook and filter in the standard manner (Fig. 5b). The wire was able to either engage the hook directly or via adherence to the covering fibrosis in almost all cases. On one occasion, the wire was only able to free the hook from the wall, and in this case the standard snare in the Gunther-Tulip kit was used to snare the freed hook in a standard manner and the filter was removed (Fig. 5b). After filter removal, digital subtraction cavography was performed in all cases, through the outer sheath (Fig. 6). The explanted filter was inspected for fracture or defect. Patients were observed for a minimum of 2 hours after the procedure and all were discharged on the same day per our department protocol.

Figure 6.

Digital subtraction cavography is performed post filter removal, through the outer sheath.

Statistical analysis

Results were pooled and analyzed. Variables were assessed for normality via the chi-square test using Real Statistics add-on for Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp.). Descriptive statistics of the data are presented with n (%). Variables with non-normal distribution are shown as median (min–max or 25–75 percentiles). Variables with normal distribution are shown as mean (±standard deviation).

Results

From 2012 to 2019 there were 473 filter retrieval attempts (Table 1). An advanced technique was documented in 66 (14%) of these cases. Of these cases, use of the hangman technique alone was documented in 23 procedures (4.9% of all procedures, 34.8% of advanced technique procedures), whilst the remaining 43 cases either used a different technique or more than one technique simultaneously.

Table 1.

Overall procedure success

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of IVC filter retrievals | 473 |

| Number of advanced techniques, n (%) | 66 (13.95) |

| Number of isolated low-profile hangman techniques, n (% of total) | 23 (4.86) |

| Successful at initial attempt, n (%) | 22 (95.96) |

| Successful overall, n (%) | 23 (100) |

| Complication, n (%) | 0 (0) |

There were 13 males (59.1%) with mean age of 47.68±3.90 years (range, 26–86 years). Most filters retrieved were Cook Celect Platinum (Cook Medical) (n=19, 82.6%), while two filters (8.7%) were optional ALN vena cava filter (ALN implants chirurgicaux, Ghisonaccia) and one filter (4.3%) was Cook Celect (Cook Medical). The median tilt was 11.5° (range, 2°–19°). The mean screening time was 27.72±5.75 minutes. At the time of retrieval attempt, 9 patients (40.9%) were taking therapeutic anticoagulation (low molecular weight heparin, novel anticoagulant, or warfarin) while the others had either ceased or were not taking anticoagulation (variables are shown in Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical variables

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 47.7±3.9 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 13 (59.1) |

| Screening time (min), mean±SD | 27.72±5.75 |

| Dwell time (days), median (range) | 196 (40–903) |

| Tilt (degrees), median (range) | 11.5 (2–19) |

| Anticoagulation during retrieval, n (%) | 19 (82.60) |

| Cook Celect Platinum filter, n (%) | 9 (40.91) |

This technique was employed as an isolated maneuver in 23 patients (4.9%) and was successful on initial attempt in 22 cases (95.6%). In one case after the hangman wire was successfully placed around the filter neck, the patient experienced abdominal pain whilst the sheath was being advanced over the hook. In spite of intravenous sedation and analgesia, a decision was made to abandon, and a second attempt with general anesthesia was performed which was successful on that attempt. The median dwell time of filters retrieved by the hangman technique was 196 days (range, 40–903 days). No filter migration or fractures, either prior to or during the retrieval procedures occurred. Postprocedure cavography was performed in all patients. No procedure-related complications occurred, including IVC injury or access site complications.

Discussion

Neointimal hyperplasia of the filter hook in tilted filters, i.e., “embedded hook”, continues to be a significant reason for failure of retrieval (16). A wide variety of advanced techniques are described, which can be used to retrieve caval filters when the standard retrieval technique fails. These include the use of angioplasty balloons, additional snares, guidewires, endobronchial forceps and endovascular laser. These techniques have various technical success rates and complication rates, some of which is likely to be in part related to operator preference, experience, and prior success (11, 17–22).

The use of a loop snare was described by Rubenstein et al. (21), who used this approach successfully to retrieve eight tilted IVC filters. This technique involved the use of a 16 F sheath, formation of a reverse curve catheter below the filter, extending a Bentson wire (0.035 inches, 260 cm; Cook Medical) above the hook which is subsequently snared with a snare device. The 16 F sheath is then advanced over the filter, and the filter is pulled back into the sheath and retrieved (21). Slight variations have subsequently been described, including variation in the reverse curve catheter, wires and additional equipment such as a Liver Access and Biopsy Needle Set. Various success rates have been described ranging as 70%–100% (16, 22). Lynch et al. (22) consider that particular filter types included in the study (Bard Recovery, G2, G2 Express, and Eclipse Inferior Vena Cava Filters) may lend themselves favorably to the technique as they are made of thin wire Nitinol, which is pliable enough to fold over into a sheath.

In 2012, Esparaz et al. (23) described the technique of forming a reverse curve catheter and wire around the radiolucent fibrin at the filter apex of a Celect filter, and subsequent removal with a standard snare device. In 2015, Al-Hakim et al. (14) further slightly modified this procedure. The hangman technique is based on the loop snare technique; however, the reverse curve catheter and wire loop is formed between the filter neck and IVC wall, as opposed to between the filter struts or the fibrin cap. The filter was then retrieved using the in situ wire loop snare, or if the wire loop slipped off the filter hook, through the fibrin cap, and the filter hook was subsequently snared. The success rate was 81.8% (9 of 11 cases) in this series, and no complications were encountered (14). Of note, this technique has been described as requiring a 14 F sheath, which necessitates a larger than normal venotomy as well as a specific sheath to be acquired separate to a standard retrieval set. While this may not be of concern to some operators, in patients where therapeutic anticoagulation is continued during retrieval it may be less desirable.

Doshi et al. (24) described a 90% success rate with the hangman technique in 29 cases used on 7 different filter types. No procedure related complications were encountered; however, the specifics of the technique were not published (24).

The new hangman technique preferred at our institution, and described recently by Clements et al. (15) in a case report, uses a modified version of the traditional hangman procedure (16) and allows use of a standard 11 F Cook Gunther-Tulip retrieval sheath and 0.018-inch 260 cm fixed-core wire (Cook Medical) to be used, rather than exchanging for a larger sheath with an 0.035-inch wire. The middle sheath (of the telescoping 3-sheath system in the retrieval kit) is firm, which negates the need for extra stabilizing equipment such as the liver access and biopsy needle set (Cook Medical). Our low-profile technique retrieves the filter without folding the filter, as described by Lynch et al. (22). Although no filter fractures due to retrieval were described by Lynch et al. (22), the low-profile hangman technique allows the filter to be retrieved in a manner similar to manufacturers recommendations, which we consider would decrease the risk of filter fracture, when compared to techniques where the filter is folded in situ prior to retrieval.

In spite of the low-profile nature of this method, we achieved 100% technical success, with only one procedure requiring repeat attempt under general anesthetic due to pain. There were no complications and this is encouraging especially given that 40.9% of the cohort remained on therapeutic anticoagulation during the procedure and this supports prior literature (25).

Literature on the hangman technique is scarce. Previously described 81%–90% technical success rates using the hangman technique are comparable to our retrieval rate of 100%. We advocate the use of an 0.018-inch fixed-core wire, which allows smaller sheath size and use of the standard Cook retrieval kit, with the only additional necessary equipment being a 260 cm fixed core wire and reverse curve catheter such as the Sos Omni. In our institution this adds only 42 USD extra to the retrieval set cost, which may make this a cost-effective option compared to purchasing and sterilizing endobronchial forceps. In addition, these items are more likely to be found on the shelf of a standard interventional radiology practice without prior arrangements needing to be made for special stock. This means that managing an unexpectedly difficult retrieval may not need a repeat procedure with stock being ordered, but simply continuing to use the standard access set and combining a low-cost set of items most likely on the shelf. There may be further such advantages in workflow and reducing repeat bookings, which is especially helpful if anticoagulation was ceased specifically for the procedure.

It must be acknowledged that cases selected to be suitable for this technique were made at operator discretion and thus introduces significant selection bias. In addition, while the IVC retrieval cohort is large, the series of low-profile hangman cases is small, which is a factor of the overall high success rates for the inherent retrieval practice at our institution and overall advanced operator experience. Higher numbers could be achieved by evaluating success in a multicenter prospective trial.

In conclusion, this retrospective audit demonstrates 100% technical success and 0% complication rate of the low-profile hangman technique for the retrieval of IVC filters with an embedded hook. Our preferred technique using 11 F Cook Gunther-Tulips access kit negates the need for upsizing the sheath and necessitates minimal additional equipment which are cost-effective and available across most interventional radiology practices.

Main points.

This low-profile hangman technique uses a modified version of the traditional hangman procedure and allows use of a standard 11 F Cook filter retrieval sheath, negating the necessity of sheath upsizing and ensuing cost.

The hangman technique was employed as isolated maneuver in 23 patients and was successful on initial attempt in 22 cases (96%). One procedure required repeat attempt under general anesthetic due to pain and was successful on this attempt.

No procedure-related complications occurred, including IVC injury or access site complications.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Al-Hakim R, Mcwilliams J. Retrievable inferior vena cava filter update. Endovasc Today. 2014:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements W. Inferior vena cava filters in the asymptomatic chronically occluded cava: to remove or not remove? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:165–168. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson W, Nicholson WJ, Tolerico P, et al. Prevalence of fracture and fragment embolization of Bard retrievable vena cava filters and clinical implications including cardiac perforation and tamponade. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1827–1831. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HS, Young MJ, Narayan AK, Hong K, Liddell RP, Streiff MB. A comparison of clinical outcomes with retrievable and permanent inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nazzal M, Chan E, Abbas J, Erikson G, Sediqe S, Gohara S. Complications related to inferior vena cava filters: a single-center experience. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young T, Tang H, Aukes J, Hughes R. Vena caval filters for the prevention of pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17:CD006212. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006212.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: The PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005;112:416–422. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.512834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turba U, Arslan B, Meuse M, et al. Gunter tulip filter retrieval experience: predictors of successful retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:732–738. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iliescu B, Haskal Z. Advanced techniques for removal of retrievable inferior vena cava filters. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:741–750. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0205-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stavropoulos SW, Dixon RG, Burke CT, et al. Embedded inferior vena cava filter removal: Use of endobronchial forceps. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1297–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo WT, Tong RT, Hwang GL, et al. High-risk retrieval of adherent and chronically implanted IVC filters: Techniques for removal and management of thrombotic complications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1548–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Hakim R, Kee S, Olinger K, Lee EW, Moriarty JM, McWilliams JP. Inferior vena cava filter retrieval: effectiveness and complications of routine and advanced techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JT, Goh GS, Joseph T, Koukounaras J, Phan T, Clements W. Prolonged balloon tamponade in the initial management of inferior vena cava injury following complicated filter retrieval, without the need for surgery. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2018;62:810–813. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Hakim R, McWilliams J, Derry W, Kee S. The hangman technique: a modified loop snare technique for the retrieval of inferior vena cava filters with embedded hooks. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clements W, Kassamali R, Joseph T. Retrieval of an embedded suprarenal inferior vena cava filter using the Hangman technique. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2018;62:806–809. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doody O, Noe G, Given M, Foley P, Lyon S. Assessment of snared-loop technique when standard retrieval of inferior vena cava filters fails. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:145–149. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch FC. Balloon-assisted removal of tilted inferior vena cava filters with embedded tips. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1210–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai K, Pandhi M, Seedial S, et al. Retrievable IVC filters: comprehensive review of device-related complications and advanced retrieval techniques. Radiographics. 2017;37:1236–1245. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stavropoulos SW, Solomon JA, Trerotola SO. Wall- embedded recovery inferior vena cava filters: Imaging features and technique for removal. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:379–382. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000196354.45643.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo W, Odegaard J, Louie J, et al. Photothermal ablation with the excimer laser sheath technique for embedded inferior vena cava filter removal: Initial results from a prospective study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:813–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.01.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubenstein L, Chun AK, Chew M, Binkert CA. Loop-snare technique for difficult inferior vena cava filter retrievals. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:1315–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch F. Modified loop snare technique for the removal of bard recovery, G2, G2 express, and eclipse inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esparaz AM, Ryu RK, Gupta R, et al. Fibrin cap disruption: an adjunctive technique for inferior vena cava filter retrieval. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1233–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doshi M, Shah K, Mohan P, et al. Fibrin cap disruption using the hangman technique for retrieval of apex embedded conical IVC filters: a highly effective technique even in filters with long dwell times (Abstract No. 654) J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29:S271. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2018.01.699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassamali RH, Burlak K, Lee JTL, et al. The safety of continuing therapeutic anticoagulation during inferior vena cava filter retrieval: a 6-year retrospective review from a tertiary centre. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:1110–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00270-019-02254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]