Abstract

SUMMARY:Lyme disease has a worldwide distribution and is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States. Incidence, clinical manifestations, and presentations vary by geography, season, and recreational habits. Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) is neurologic involvement secondary to systemic infection by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States and by Borrelia garinii or Borrelia afzelii species in Europe. Enhanced awareness of the clinical presentation of Lyme disease allows inclusion of LNB in the imaging differential diagnosis of facial neuritis, multiple enhancing cranial nerves, enhancing noncompressive radiculitis, and pediatric leptomeningitis with white matter hyperintensities on MR imaging. The MR imaging white matter appearance of successfully treated LNB and multiple sclerosis display sufficient similarity to suggest a common autoimmune pathogenesis for both. This review highlights differences in the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of Lyme disease in the United States, Europe, and Asia, with an emphasis on neurologic manifestations and neuroimaging.

Lyme borreliosis is a tick-transmitted multisystem inflammatory disease caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, in the United States and Borrelia garinii and Borrelia afzelii in Europe.1,2 With approximately 20,000 new cases reported each year, Lyme disease has become the most common vector-borne disease in the United States.3

The Lyme disease syndrome, manifest as erythema migrans, meningopolyneuritis, and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, was first described in the early and mid-20th century in Europe and later recognized in the United States in Old Lyme, Connecticut, in 1976.4,5 Lyme disease was subsequently linked to the recovery of a previously unrecognized spirochete, B. burgdorferi, which is transmitted by the bite of the Ixodes tick (Fig 1). After sustained attachment of the infected tick to the host, the spirochete is transmitted to the human host in the tick salivary secretions.6,7

Fig 1.

Blacklegged tick (I Scapularis): adult female, adult male, nymph, and larva. Reprinted with permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This review will highlight the differences in the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of Lyme disease in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Emphasis is placed on the diagnosis and clinical spectrum of Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB), with special attention to the varying features of corroborative diagnostic neuroimaging.

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

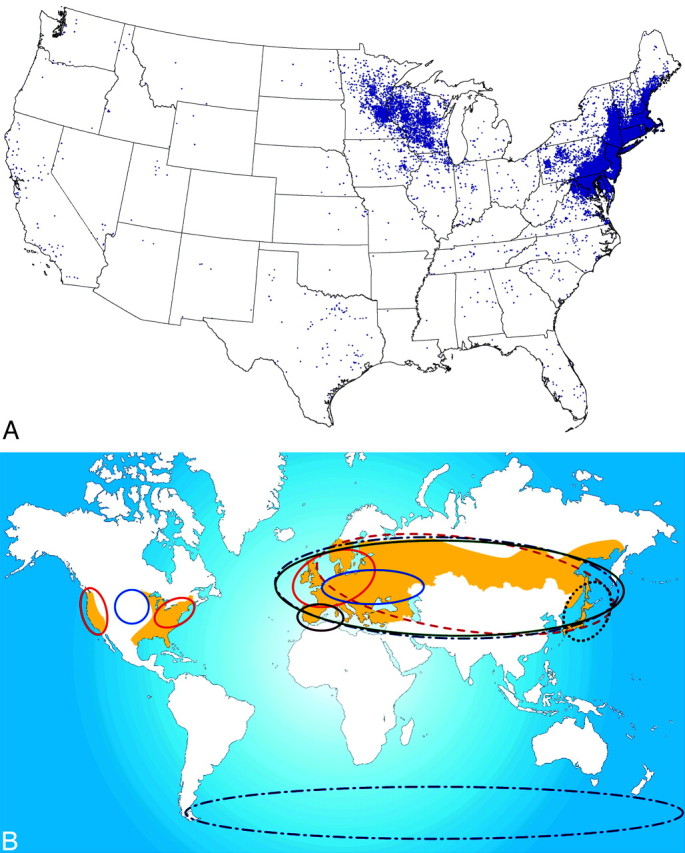

More than 200,000 cases of Lyme disease in the United States have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control, resulting in a national incidence of 9.7 cases per 100 000 population. The prevalence of Lyme disease varies significantly by geography and has a seasonal incidence (Fig 2A, -B). More than 93% of Lyme disease cases in the United States have been reported in high endemic Midatlantic states, Michigan, and Minnesota.3 Lyme disease occurrence peaks during summer months, reflecting the enhanced transmission by the nymphal tick vectors during May and June. Since Lyme disease became nationally notifiable in 1991, the annual number of reported cases has more than doubled.3

Fig 2.

A, Summary of reported cases of Lyme disease in the United States. There is 1 dot within the county of residence for each reported case. Note the widespread diversity of cases correlating with the prevalence of infected Ixodes species in different geographic areas. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control. B, The beige-shaded areas indicate the geographic distribution of recorded clinical cases of Lyme borreliosis. The colored ellipses indicate the distribution of the various Borrelia subspecies. Fig 2B is reprinted with permission from Nature Publishing Group.108

Tick-borne diseases, such as Lyme disease, are dynamic and rapidly evolving in the United States, due in part to climate change.3 B. burgdorferi is a zoonosis maintained at high levels in animals, such as field mice and white-tailed deer.8–11 Song birds and waterfowl also appear to play a major role in the dispersion of infected ticks.9 Borrelia species are transmitted by the bite of infected Ixodes ticks, namely Ixodes scapularis in the United States and predominantly Ixodes ricinus in Europe.3,11–14 Transmission of B. burgdorferi requires at least 24–48 hours of tick attachment.15 Unfortunately, most adult patients do not recall the tick bite because the dominant nymphal Ixodes ticks are very small and often unrecognized when attached to the skin or may fall off after feeding.8

As with other spirochetal infections such as syphilis, Lyme disease occurs in stages, with a wide spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms at each stage. Incubation varies from 3 to 32 days, after which a characteristic enlarging target-like rash, known as erythema migrans (Fig 3), may be evident and accompanied by flulike symptoms of fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias (stage 1).16 After several weeks to months, neurologic abnormalities and cardiac involvement may be seen in 15% and 8% of patients, respectively (stage 2). Migrating very transitory musculoskeletal pain in limited joints, bursae, tendons, muscle, or bone is a common feature of early Lyme disease.17 Within 2–4 weeks after the onset of infection, untreated patients develop a marked cellular and humoral immune response to the spirochete. In stage 3, patients may develop chronic monoarticular or oligoarticular Lyme arthritis, which commonly involves large joints, particularly the knee.18,19

Fig 3.

Erythema migrans rash with the typical target appearance that is virtually diagnostic of Lyme disease.

As shown in the Table, worldwide clinical manifestations of Lyme disease vary as a function of different subspecies but invariably include systemic symptoms and involvement of the dermatologic, neurologic, cardiac, and/or musculoskeletal systems.1,8,14,19–21 In the United States, erythema migrans rash, arthritis, and carditis are common presentations. In Europe and Asia, radiculitis and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans are more common presenting signs. Generalized lymphadenopathy is not a classic feature of Lyme disease, but a Borrelial lymphocytoma may develop at the site of antecedent tick bite. There is a predilection for the ear, nipple, and scrotum.22 A weak association with primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma has been observed in Europe.23

Comparison of clinical differences between American and European LNB*

| Manifestations of Lyme Borreliosis | ||

|---|---|---|

| LNB | American LNB | European LNB |

| Subspecies | B burgdorferi sensu stricto | B garinii > B afzelii |

| LNB/LD | <10% | >35% |

| Painful radiculitis | <10% | >50% |

| Aseptic meningitis at presentation | Majority | Minority |

| Intrathecal antibodies | Minority | >50% |

| Cranial neuropathy | VII, rarely others | VII and others |

| Chronic encephalomyeloradiculitis | <0.1% | Unusual, <3% |

| Erythema migrans | Common, <5 cm erythematous patch at the site of tick bite | Uncommon |

| Chronic skin manifestations | Never | 10% Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans: chronic extensor surface discoloration |

| ± Swelling | ||

| ± Associated peripheral neuropathy | ||

| Associated Lyme arthritis | Common, pauciarticular; knees ∼50%, weeks-to-months postinfection | Rare |

| Carditis | Heart block, transient possible perimyocarditis | Rare |

The characteristic erythema migrans rash (Fig 3) is a hallmark of the disease and manifests as an area of expanding erythema >5 cm in diameter. It is commonly raised and sometimes pruritic. This circular or elliptic red area spreads centrifugally, reflecting movement of spirochetes through lymphatics of the skin. Subsequent central clearing gives the appearance of a “target.”8 In some patients, there are multiple lesions, suggesting dissemination of the spirochete. The erythematous rash should not be confused with the small area of erythema around other tick bites, which reflects a host reaction to the bite. The erythema migrans rash is commonly recalled by the patient at the later time of presentation with LNB.8

I scapularis ticks may also transmit other infectious agents, such as Anaplasma phagocytophilum (anaplasmosis) or human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, human monocytic ehrlichiosis, Babesia microti (babesiosis), and, less commonly, Franciscella tularensis (tularemia). Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) and Master disease are transmitted by the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) in the southern United States and may have a clinical presentation similar to that of Lyme disease due to the transmitted bacterium (Borrelia lonestari).

Diagnostic Tests for Lyme Disease

The diagnosis of Lyme disease should be based on a history of tick exposure, epidemiology, clinical signs and symptoms at different stages of the disease (Table), and the use of serologic tests. Early Lyme disease in a patient with erythema migrans is virtually 100% specific and more sensitive (57%–86%) than serology.24 Adults at risk for tick-borne disease who develop persistent “summer flu” symptoms should increase the clinical suspicion of tick-borne illnesses, such as Lyme disease.

A definitive diagnosis of LNB requires evidence of possible exposure, signs and symptoms of nervous system disease, and supportive laboratory data. Because LNB frequently has clinical overlap with other medical illnesses, there are many obstacles and pitfalls to securing the diagnosis with laboratory confirmation. B burgdorferi can be identified by direct microscopy in tissue biopsies, electron microscopy, and by culture, but these methodologies are not readily available.25 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for clinical samples has had a low sensitivity for blood and CSF in Lyme disease but has been useful on synovial fluid specimens in patients with Lyme arthritis.8,25

Most patients with suspected Lyme disease are currently tested for evidence of antibodies against B burgdorferi. However, B burgdorferi has extremely complex antigenic composition, which may vary by host and stage of the infection. Therefore, the use of indirect methods to detect serum antibodies to B burgdorferi, based on a 2-step method by using an initial enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or indirect florescent antibody assay, followed by confirmation of a positive or equivocal initial test by immunoblot or Western blot is commonly used.25 The 2-step method has advantages, such as ease of testing, better standardization, and greater diagnostic sensitivity than PCR but lacks sensitivity in early disease.16,24 Current standards for the diagnosis of Lyme disease include a sensitive EIA, followed by Western blot (or immunoblot) with findings of abnormal immunoglobulin M (IgM) (at least 2 bands) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (at least 5 bands).

Patients with suspected LNB may have evidence of IgG synthesis against B burgdorferi antigens in the CSF and elevated CSF inflammatory cells (usually lymphocytes, monocytes, or plasma cells), elevated protein, Borrelia-specific intrathecal antibodies, or PCR-detectable Borrelia species antigens (in early cases of Lyme disease). CSF Lyme antibodies (IgM, IgG, and immunoglobulin A) in the absence of inflammatory cells suggest previous infection. Tests developed for the detection of Lyme disease in Europe may not detect high antibody values in infections in the United States and vice versa.16

The use of an EIA with recombinant chimeric proteins, such as the C6 peptide, appears sensitive and has been suggested for use as a single assay, rather than the current 2-tier EIA and Western blot assays. Clearly, further studies are needed to elucidate the advantages and limitations of Lyme disease testing, especially for patients at different stages of neuroborreliosis and in different countries. The use of commercial laboratories that offer Lyme diagnostic tests that have not been professionally validated should be discouraged and prohibited for clinical use.26–28

LNB

LNB results when systemic infection with the spirochete B burgdorferi leads to neurologic involvement.6,8,29,30 Approximately 10%–15% of patients with untreated Lyme disease will develop neurologic manifestations.8,14,19,31–34 The enhanced recognition and surveillance for LNB has generated a plethora of recent outstanding clinical review manuscripts.8,14,16,19,31–34

The likelihood of a person developing LNB is dependent on the Borrelia species, geography, recreational habits of the individual, and season of the year. Because the spirochetes are transmitted to human beings only by the bite of infected ticks, individuals who do not frequent endemic areas or have not been in a situation predisposing to an infected tick bite cannot have LNB.8 The presentation of LNB can vary from weeks to months after exposure.

Pathology

Pachner and Steiner8 observed that LNB inflammation in the nervous system in rhesus macaques was primarily localized to dorsal root ganglia, nerve roots, and leptomeninges. T-lymphocytes and plasma cells were the predominant inflammatory cell markers. Significantly increased amounts of immunoglobulin (IgG, IgM) and complement (C1q) are found in inflamed spinal cords. Spirochetes can be visualized by immunohistochemistry in the leptomeninges, nerve roots, and dorsal root ganglia, but not in the central nervous system (CNS) parenchyma.8 This predisposition correlates well with classic clinical LNB manifested by a predominant meningitis and radiculitis and the rare presence of intra-axial parenchymal brain and spinal cord involvement.8

Borrelia subspecies are responsible for significant differences in the clinical presentations of LNB observed in North America and Europe. European case reports of a painful radiculitis (Garin-Bujadoux-Bannwarth syndrome) and chronic progressive spastic paraparesis suggest a greater neurotropism to B garinii, which has not been found in the United States.35,16

Peripheral Nervous System Manifestations

Peripheral nervous system (PNS) manifestations of LNB are variable and may range from mild-to-severe intermittent sensory symptoms to a typical constant dermatomal painful radiculitis. The latter is a prominent feature of European LNB but is less commonly recognized in the United States. Approximately 85% of European disease presents with Bannwarth syndrome, a painful lymphocytic meningoradiculitis with or without paresis. The pain is frequently sharp, may display nocturnal exacerbations, and may last weeks to months.8 The European presentations are further confounded by a lower incidence of recognized erythema migrans. In the absence of a compressive etiology, Bannwarth syndrome may be a unique clinical hallmark of B garinii LNB. This form of LNB is rarely seen in North American LNB.8,36 Enhancement of spinal nerve roots has been observed on postcontrast T1-weighted sequences in the lower spinal cord and cauda equina more than in cervical cord and roots associated with a lymphocytic meningitis.37

North American LNB usually presents as a subacute meningitis within weeks to months of an antecedent untreated erythema migrans rash.8 Unilateral more than bilateral cranial nerve palsy occurs frequently. The seventh cranial nerve is most frequently involved (Fig 4).32 Lyme disease is an infrequent cause of isolated facial palsy in patients without constitutional symptoms or additional neurologic findings. However, in endemic areas, it may be responsible for ≥25% of new-onset Bell palsy.38,39

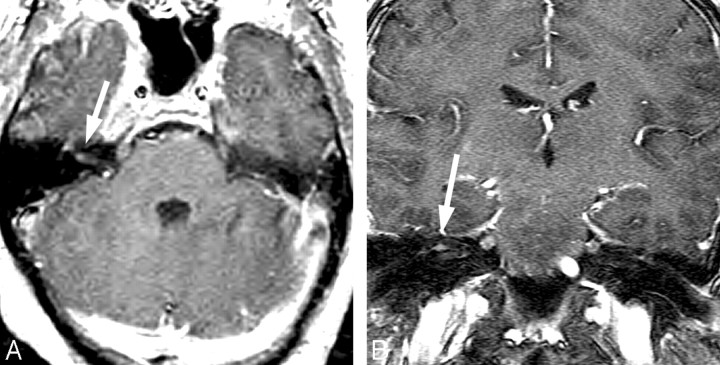

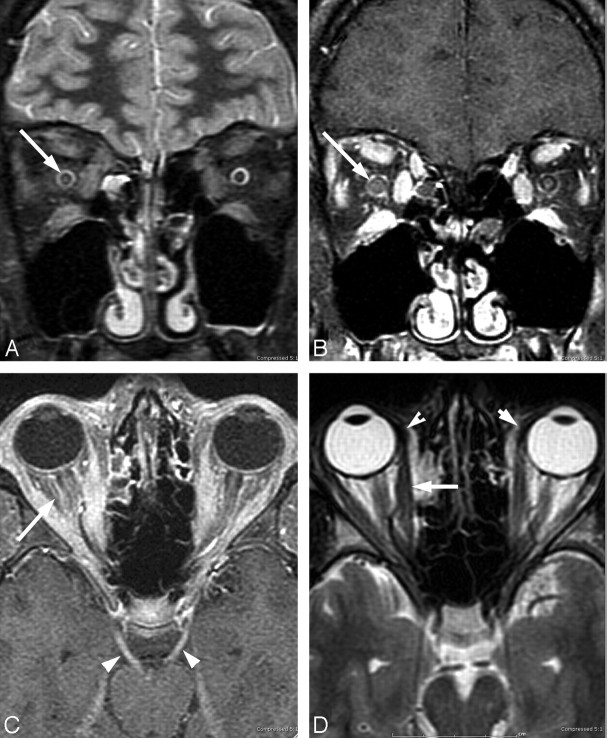

Fig 4.

Facial neuritis. A 48-year-old woman with headache and peripheral right facial palsy. Prominent enhancement of the fundal tuft and labyrinthine segment of the seventh cranial nerve on postinfusion axial T1 (A) and coronal spoiled gradient-recalled sequences (B). The patient had CSF pleocytosis, Lyme-positive EIA, and Western blot (IgM and IgG) in serum and CSF. Resolution occurred with intravenous ceftriaxone therapy.

There are no neurologic or imaging findings specific for LNB. In the appropriate geographic and seasonal setting, facial diplegia is highly suggestive of LNB as is headache and facial palsy, especially when coupled with a history of erythema migrans. Because erythema migrans may be absent and is usually not present at time of the clinical presentation of neurologic symptoms, suspicion of LNB should be confirmed by serum or CSF antibodies for Borrelia species.8 Sarcoidosis may have a similar neurologic presentation and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

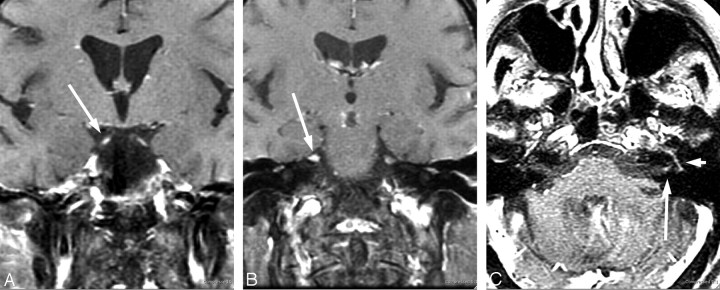

The role of imaging in the assessment of peripheral Lyme disease is enhanced awareness of LNB in the differential diagnosis of cranial neuritis and/or radiculitis in both endemic populations and in patients with a travel history to endemic areas. To our knowledge, there are no published prospective studies citing the incidence of cranial or radicular nerve enhancement in the clinical setting of Lyme disease. Similarly, the described pattern of contrast enhancement has been restricted to case series.18,40,41 Third, fifth, and seventh cranial nerve enhancements have all been reported (Fig 5).42,43 We have observed enhancement predominantly of the seventh cranial nerve with combined involvement of the fundal tuft and labyrinthine and tympanic segments more than generalized fundal tuft-to-mastoid involvement. The higher incidence of meningoradiculoneuritis (Bannwarth syndrome) in Europe is characterized by specific MR imaging findings of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar nerve root contrast enhancement.37,40,44 Of note is the frequent absence of a correlation between multiple enhancing cranial or radicular nerves and neurologic symptoms.40

Fig 5.

Evolving cranial neuritis. A 71-year-old woman with headache, malaise, fever, and diplopia. Initial coronal postcontrast T1 MR imaging (A and B) with enhancing bilateral third and fifth cranial nerves. C, Nine days later, she developed left facial palsy with enhancing fundal tuft and labyrinthine and tympanic segments of the seventh cranial nerve. The patient had CSF pleocytosis with positive Lyme-EIA and Western blot in both serum and CSF and CSF Lyme PCR-negative findings. Resolution occurred with intravenous ceftriaxone therapy.

CNS LNB

Despite the significant increased awareness of LNB and emphasis directed at its diagnosis and treatment, its neuropathology is incompletely understood. Subsequent to the tick bite inoculation, Borrelia species most likely reach the CNS either hematogenously or retrogradely via the peripheral nerves.31 In the United States, dissemination is predominantly hematogenous, leading to meningoencephalitis.31,45 This feature contrasts with the European variant of predominant nerve root involvement (Bannwarth syndrome), wherein dissemination of endemic B garinii and B afzelii mainly occurs through the peripheral nerves. The putative mechanisms for LNB CNS injury include vasculitis, cytotoxicity, neurotoxic mediators, or autoimmune reaction via molecular mimicry.31

Direct CNS symptoms vary widely, ranging from a mild confusional state to severe encephalitis. Cranial neuropathies and motor or sensory radiculoneuritis have their highest incidence in children and adolescents.46 The intrathecal production of anti-B burgdorferi antibodies or a positive PCR are the most reliable indicators of CNS infection. The CSF typically demonstrates a lymphocytic meningitis, with increased protein and increased CSF-to-serum-antibody ratios.

Encephalomyelitis is a very rare complication of borreliosis, with a few reports of progressive and severe courses of the disease.47–51 In most cases of encephalomyelitis, MR imaging is very helpful in assessing the presence of rare tumefactive white matter lesions that may mimic a neoplastic process.47,48,51 Tumefactive lesion biopsies are characterized by microgliosis and spirochetes morphologically compatible with B burgdorferi yet paradoxically without an inflammatory infiltrate.48,52–54 Very rarely, MR imaging has documented reversal of LNB encephalitis subsequent to antibiotic management.49,55 The imaging resolution, however, lagged years behind the rapid clinical response to intravenous antibiotics.

Approximately half of the patients with LNB demonstrate nonspecific abnormal imaging findings predominantly within the frontal cortex white matter arcuate fibers.53,56 Despite successful clinical resolution with antibiotic management, white matter involvement often persists on MR imaging (Fig 6).46

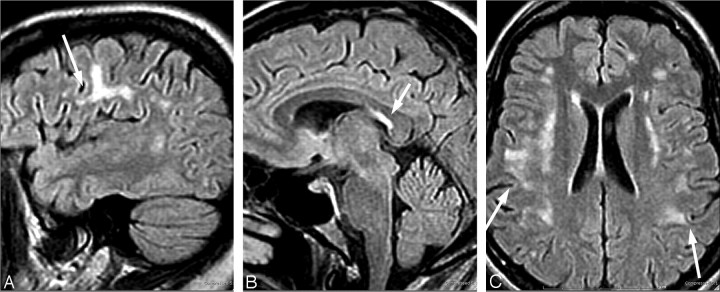

Fig 6.

A 50-year-old woman with a history of tick bite and erythema migrans rash treated with doxycycline, who had recurrent erythema migrans rash with headache, fever, nausea, and nuchal rigidity. The patient had CSF pleocytosis with positive Lyme serum EIA and IgM Western blot and negative Lyme antibodies in the CSF. Gradual symptomatic improvement occurred following intravenous ceftriaxone therapy. There has been stable MR imaging for 5 years. Sagittal (A and B) and axial (C) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images show arcuate and confluent subcortical white matter involvement and callososeptal interface involvement remarkably similar to that in MS, but without involvement of the periventricular white matter.

The distribution of involvement including the callososeptal interface fuels speculation as to a secondary autoimmune mechanism with imaging features mimicking primary demyelinating disease (Fig 7).40,46,48,57–65 Similar mechanisms of molecular mimicry and antigen-specific T-cell response have been recognized in both multiple sclerosis (MS) and chronic LNB.66 Yet, T-cell lines demonstrate only weak cross-reactivity between myelin basic protein and B burgdorferi.67

Fig 7.

A 74-year-old man with 2-year cognitive decline and memory loss. The patient had Lyme-positive serum EIA and Western blot (IgG and IgM) and CSF pleocytosis with CSF positive Lyme IgM and IgG antibodies. The patient improved with intravenous ceftriaxone therapy. The “dot-dash” callososeptal interface (A) and periventricular distribution of involvement (B) would be routinely ascribed to a demyelinating process.

Unlike MS, occult brain and cervical cord pathology in normal-appearing white matter, as assessed by magnetization transfer ratios and diffusion tensor imaging, are infrequent findings in patients with LNB.58 A classic clinical presentation with exposure history, meningitis, CSF pleocytosis, and elevated Lyme disease antibody titers aids in discrimination from MS. However, when the characteristic prodrome of erythema migrans, exposure history, or arthritis is lacking, the multifocal clinical findings on neurologic examination and positive oligoclonal bands and white matter patterns on MR imaging may confuse the diagnosis with that of MS.57,63

Borrelia species are very difficult to culture as exemplified by individual case reports of rare strokelike presentations, wherein brain biopsies merely demonstrated a nonspecific perivascular or vasculitic lymphocytic inflammation.48 In the appropriate clinical and geographic setting, rare instances of LNB vasculitis with ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intracerebral hemorrhage have been reported.48,68–75 Single-photon emission CT may provide indirect manifestations of LNB antibiotic-reversible frontal hypoperfusion.65,76,77

Spinal Cord LNB

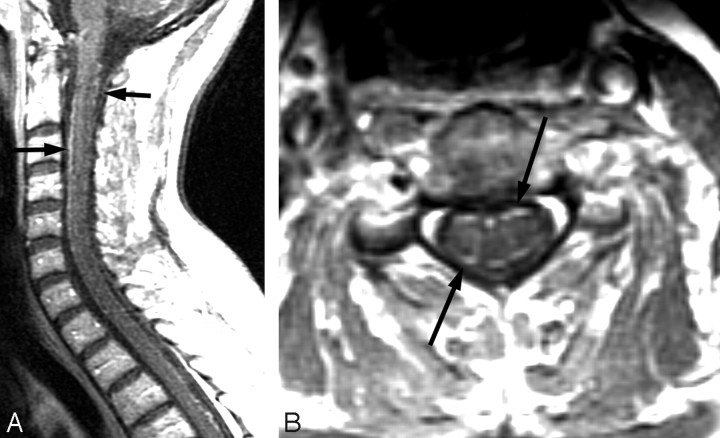

Spinal cord involvement by B burgdorferi is very rare. As a function of geography, LNB would be a rare differential consideration in the evaluation of transverse myelitis. MR imaging findings with LNB myelopathy are characterized by diffuse or multifocal T2-weighted cord lesions. In contrast to the classic cervical spinal cord MR imaging abnormalities seen in MS, most patients with LNB do not have macroscopic lesions or magnetization-transfer ratio changes.58 Nerve root involvement is best seen on postcontrast T1-weighted sequences.40 Spinal involvement has demonstrated diffuse or multifocal T2-weighted cord lesions and nerve root enhancement on postcontrast T1-weighted sequences (Fig 8).40

Fig 8.

A 56-year-old woman with neck, bilateral shoulder, and bilateral arm pain. In 2 weeks, she subsequently developed left facial palsy and positive serum EIA and Western blot (IgM and IgG) and CSF Lyme IgG and IgM antibodies. Complete resolution of symptoms occurred with oral doxycycline. Postcontrast sagittal and axial T1-weighted MR images show diffuse thin uniform cervical spinal cord leptomeningeal enhancement without apparent root or ganglion enhancement.

Orbital and Ocular Lyme Disease

Rare ocular LNB may occur at all 3 stages of the disease. Uveitis and optic neuritis are the most common ocular complications.78 Conjunctivitis and episcleritis are the most frequent manifestations of the early stage. Neuro-ophthalmic disorders and uveitis occur in the second stage, whereas keratitis, chronic intraocular inflammation, and orbital myositis are seen in the third stage of Lyme disease.79 A nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis occurs in approximately 10% of patients with Lyme disease.39 Direct ocular infection and a delayed hypersensitivity mechanism may be involved at different disease stages.

Borrelial orbital myositis is most probably an immunologically mediated response subsequent to hematogenous dissemination of Borrelia species.80 The clinical and imaging manifestations of orbital myositis Lyme disease closely mimic those of orbital pseudotumor (Fig 9). The differential diagnosis includes lymphoma or possibly thyroid dysorbitopathy. Criteria for orbital and ocular Lyme disease include the lack of evidence of other diseases, occurrence in patients living in an endemic area, positive serology, and, in most cases, response to treatment.39

Fig 9.

A 17-year-old boy with right papilledema and orbital pain and rule out pseudotumor. The patient had positive serum EIA and Western blot (IgM and IgG) and CSF Lyme IgM and IgG antibodies. Lyme PCR in the CSF was negative. Complete resolution of symptoms occurred after intravenous ceftriaxone therapy. Right optic nerve edema on fat-saturated T2-weighted fast spin-echo images (A) and right-greater-than-left optic nerve enhancement on coronal fat-saturated contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (B). C, Bilateral third cranial nerve enhancement (arrowheads) and bilateral retrobulbar compartment congestion (arrow). Note the generalized extraocular muscle enlargement and enhancement, including the insertions. Additional imaging findings included enhancement of right fifth cranial nerve, optic chiasm, and intracanalicular right seventh nerve, all of which were occult to neurologic examination.

Pediatric LNB

Thirty percent of Lyme disease cases occur in children.3 The presence of erythema migrans in 89% of children significantly aids the clinical diagnosis.81 It is speculated that the CNS lesions in children represent a spirochete-triggered autoimmune process.82 Headache is the most frequent neurologic symptom; the most common neurologic signs of pediatric LNB include facial nerve palsy (3%–5%) and meningitis (1%). Less common manifestations are sleep disturbance and papilledema associated with increased intracranial pressure.83,84 Ataxia, chorea, myelitis, pseudotumor cerebri, meningitis, and encephalopathy are very uncommon.84–90 Peripheral neuropathies, radiculopathies, and Bannwarth syndrome are other rare pediatric LNB manifestations.

Brain MR imaging findings in pediatric LNB include the presence of prominent Virchow-Robin spaces, T2 bright white matter lesions, pial and cranial nerve enhancement, and treatment-responsive lesion enhancement.18,82

Despite having a greater incidence of LNB, the clinical course in most children is milder and shorter than that reported for adults.89 Facial nerve palsy resolves in 95% of pediatric patients irrespective of treatment.90 The use of doxycycline for the primary therapy of Lyme disease is restricted due to side effects in this population of patients.

Chronic Lyme Disease

The clinical presence of a chronic form of neuroborreliosis subsequent to classic verified objective manifestations and rigorous antibiotic management remains a focus of ongoing conjecture and controversy.34,46,91–96 The inflammatory reaction of neuroborreliosis is postulated by some to be one of the etiologies for a very broad spectrum of neurologic disorders. These include the amyloid deposition of Alzheimer disease, MS, autism, and neuropsychiatric illness.65,95,97–106 The diagnosis of chronic LNB is predicated on characteristic symptoms, specific serum antibodies, CSF pleocytosis, and intrathecal Lyme antibody production. The utility of brain MR imaging in confirming diagnostic suspicion of chronic LNB is very limited, due to the overlap with age-related basal ganglionic and subcortical white matter lesions and persistence subsequent to successful treatment of LNB. Conversely, LNB is a diagnostic consideration in a young patient with subependymal white matter lesions, a history of geographic/seasonal risk factors, and neurologic symptoms.107

Conclusions

LNB is an insidious infectious neurologic disease caused by the spirochete B burgdorferi. The mechanism of neurologic injury probably includes vasculitis, cytotoxicity, neurotoxic mediators, or autoimmune reaction via molecular mimicry. Although there are no neurologic or imaging findings specific for the diagnosis of LNB, an enhanced level of surveillance is required as a function of geography, recreational/travel history of the patient, and season of the year. In the at-risk patient population, LNB should be included in the imaging differential diagnosis of facial neuritis, multiple enhancing cranial nerves, enhancing noncompressive radiculitis, pediatric leptomeningitis with white matter hyperintensities, and symmetric orbital myositis with cranial neuritis. There is an overlap in the CNS MR imaging appearance of LNB and MS; however, unlike MS, cervical cord pathology and occult brain involvement in normal-appearing white matter are infrequent findings in patients with LNB. Further refinements and ongoing research in serum and CSF serologic tests will be required for better detection of active acute and chronic manifestations of Lyme disease.

References

- 1.Aberer E. Lyme borreliosis: an update [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007;5:406–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensenius M, Parola P, Raoult D. Threats to international travellers posed by tick-borne diseases. Travel Med Infect Dis 2006;4:4–13. Epub 2004 Dec 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lyme disease: United States, 2003–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:573–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mast WE, Burrows WM, Jr. Erythema chronicum migrans in the United States. JAMA 1976;236:859–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mast WE, Burrows WM. Erythema chronicum migrans and “lyme arthritis.” JAMA 1976;236:2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, et al. Lyme disease: a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 1982;216:1317–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steere AC, Grodzicki RL, Kornblatt AN, et al. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 1983;308:733–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pachner AR, Steiner I. Lyme neuroborreliosis: infection, immunity, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:544–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed KD, Meece JK, Henkel JS, et al. Birds, migration and emerging zoonoses: west Nile virus, Lyme disease, influenza A and enteropathogens. Clin Med Res 2003;1:5–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halperin JJ. Nervous system Lyme disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2002;2:241–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dam AP. Diversity of Ixodes-borne Borrelia species: clinical, pathogenetic, and diagnostic implications and impact on vaccine development. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2002;2:249–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wormser GP. Clinical practice: early Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2794–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grubhoffer L, Golovchenko M, Vancova M, et al. Lyme borreliosis: insights into tick-/host-borrelia relations. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 2005;52:279–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bratton RL, Whiteside JW, Hovan MJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:566–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halperin JJ. Lyme disease and the peripheral nervous system. Muscle Nerve 2003;28:133–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hengge UR, Tannapfel A, Tyring SK, et al. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:489–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steere AC. Musculoskeletal manifestations of Lyme disease. Am J Med 1995;98:44S–48S, discussion 48S–51S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanzieleghem B, Lemmerling M, Carton D, et al. Lyme disease in a child presenting with bilateral facial nerve palsy: MRI findings and review of the literature. Neuroradiology 1998;40:739–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stonehouse A, Studdiford JS, Henry CA. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of early Lyme disease: “focusing on the bull's eye, you may miss the mark.” J Emerg Med 2007. Oct 16. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.DePietropaolo DL, Powers JH, Gill JM, et al. Diagnosis of Lyme disease. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:297–304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huppertz HI. Lyme disease in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2001;13:434–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme disease: European perspective. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:327–39, vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood 2008;112:1600–09. Epub 2008 Jun 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tugwell P, Dennis DT, Weinstein A, et al. Laboratory evaluation in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1109–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, et al. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18:484–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1995;44:590–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Effect of electronic laboratory reporting on the burden of Lyme disease surveillance: New Jersey, 2001–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:42–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klempner MS, Schmid CH, Hu L, et al. Intralaboratory reliability of serologic and urine testing for Lyme disease. Am J Med 2001;110:217–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pachner AR. The immune response to infectious diseases of the central nervous system: a tenuous balance. Springer Semin Immunopathol 1996;18:25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345:115–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rupprecht TA, Koedel U, Fingerle V, et al. The pathogenesis of Lyme neuroborreliosis: from infection to inflammation. Mol Med 2008;14:205–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halperin JJ. Nervous system Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:261–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tilly K, Rosa PA, Stewart PE. Biology of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:217–34, v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoppa E, Bachur R. Lyme disease update. Curr Opin Pediatr 2007;19:275–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halperin JJ. North American Lyme neuroborreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1991;77:74–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donaldson JO, Lewis RA. Lymphocytic meningoradiculitis in the United States. Neurology 1983;33:1476–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demaerel P, Crevits I, Casteels-Van Daele M, et al. Meningoradiculitis due to borreliosis presenting as low back pain only. Neuroradiology 1998;40:126–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ljostad U, Okstad S, Topstad T, et al. Acute peripheral facial palsy in adults. J Neurol 2005;252:672–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lesser RL. Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Am J Med 1995;98:60S–62S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hattingen E, Weidauer S, Kieslich M, et al. MR imaging in neuroborreliosis of the cervical spinal cord. Eur Radiol 2004;14:2072–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boukobza M, Guichard JP, Merland JJ, et al. Facial diplegia in the course of childhood Lyme disease: bilateral enhancement of the facial nerve and MRI after injection of gadolinium [in French]. J Neuroradiol 1997;24:270–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savas R, Sommer A, Gueckel F, et al. Isolated oculomotor nerve paralysis in Lyme disease: MRI. Neuroradiology 1997;39:139–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson JA, Wolf MD, Yuh WT, et al. Cranial nerve involvement with Lyme borreliosis demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology 1992;42 (3 pt 1):671–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mantienne C, Albucher JF, Catalaa I, et al. MRI in Lyme disease of the spinal cord. Neuroradiology 2001;43:485–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wormser GP, McKenna D, Carlin J, et al. Brief communication: hematogenous dissemination in early Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:751–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgen K, Martin R, Stone RD, et al. FLAIR and magnetization transfer imaging of patients with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. Neurology 2001;57:1980–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Logigian EL, Kaplan RF, Steere AC. Chronic neurologic manifestations of lyme disease. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1438–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oksi J, Kalimo H, Marttila RJ, et al. Inflammatory brain changes in Lyme borreliosis: a report on three patients and review of literature. Brain 1996;119 (pt 6):2143–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steinbach JP, Melms A, Skalej M, et al. Delayed resolution of white matter changes following therapy of B burgdorferi encephalitis. Neurology 2005;64:758–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oschmann P, Dorndorf W, Hornig C, et al. Stages and syndromes of neuroborreliosis. J Neurol 1998;245:262–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massengo SA, Bonnet F, Braun C, et al. Severe neuroborreliosis: the benefit of prolonged high-dose combination of antimicrobial agents with steroids—an illustrative case. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2005;51:127–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pachner AR, Duray P, Steere AC. Central nervous system manifestations of Lyme disease. Arch Neurol 1989;46:790–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rafto SE, Milton WJ, Galetta SL, et al. Biopsy-confirmed CNS Lyme disease: MR appearance at 1.5 T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990;11:482–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray R, Morawetz R, Kepes J, et al. Lyme neuroborreliosis manifesting as an intracranial mass lesion. Neurosurgery 1992;30:769–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halperin JJ. Nervous system manifestations of Lyme disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:635–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez RE, Rothberg M, Ferencz G, et al. Lyme disease of the CNS: MR imaging findings in 14 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990;11:479–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fadil H, Kelley RE, Gonzalez-Toledo E. Differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol 2007;79:393–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agosta F, Rocca MA, Benedetti B, et al. MR imaging assessment of brain and cervical cord damage in patients with neuroborreliosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:892–94 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Latsch K, Tappe D, Warmuth-Metz M, et al. Central nervous system borreliosis mimicking a pontine tumour. J Med Microbiol 2006;55 (pt 11):1597–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van der Stappen A, De Cauwer H, van den Hauwe L. MR findings in acute cerebellitis. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1071–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmutzhard E. Multiple sclerosis and Lyme borreliosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2002;114:539–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kieslich M, Fiedler A, Driever PH, et al. Lyme borreliosis mimicking central nervous system malignancy: the diagnostic pitfall of cerebrospinal fluid cytology. Brain Dev 2000;22:403–06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karussis D, Weiner HL, Abramsky O. Multiple sclerosis vs Lyme disease: a case presentation to a discussant and a review of the literature. Mult Scler 1999;5:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Triulzi F, Scotti G. Differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: contribution of magnetic resonance techniques. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64 (suppl 1):S6–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Logigian EL, Johnson KA, Kijewski MF, et al. Reversible cerebral hypoperfusion in Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology 1997;49:1661–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin R, Gran B, Zhao Y, et al. Molecular mimicry and antigen-specific T cell responses in multiple sclerosis and chronic CNS Lyme disease. J Autoimmun 2001;16:187–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pohl-Koppe A, Logigian EL, Steere AC, et al. Cross-reactivity of Borrelia burgdorferi and myelin basic protein-specific T cells is not observed in borrelial encephalomyelitis. Cell Immunol 1999;194:118–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chehrenama M, Zagardo MT, Koski CL. Subarachnoid hemorrhage in a patient with Lyme disease. Neurology 1997;48:520–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seijo Martinez M, Grandes Ibanez J, Sanchez Herrero J, et al. Spontaneous brain hemorrhage associated with Lyme neuroborreliosis. Neurologia 2001;16:43–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Topakian R, Stieglbauer K, Aichner FT. Unexplained cerebral vasculitis and stroke: keep Lyme neuroborreliosis in mind. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:756–57, author reply 757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hammers-Berggren S, Grondahl A, Karlsson M, et al. Screening for neuroborreliosis in patients with stroke. Stroke 1993;24:1393–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmitt AB, Kuker W, Nacimiento W. Neuroborreliosis with extensive cerebral vasculitis and multiple cerebral infarcts [in German]. Nervenarzt 1999;70:167–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cox MG, Wolfs TF, Lo TH, et al. Neuroborreliosis causing focal cerebral arteriopathy in a child. Neuropediatrics 2005;36:104–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Romi F, Krakenes J, Aarli JA, et al. Neuroborreliosis with vasculitis causing stroke-like manifestations. Eur Neurol 2004;51:49–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmiedel J, Gahn G, von Kummer R, et al. Cerebral vasculitis with multiple infarcts caused by Lyme disease. Cerebrovasc Dis 2004;17:79–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Logigian EL, Kaplan RF, Steere AC. Successful treatment of Lyme encephalopathy with intravenous ceftriaxone. J Infect Dis 1999;180:377–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sumiya H, Kobayashi K, Mizukoshi C, et al. Brain perfusion SPECT in Lyme neuroborreliosis. J Nucl Med 1997;38:1120–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bodaghi B. Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease[in French]. Med Mal Infect 2007;37:518–22. Epub 2007 Mar 21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zagorski Z, Biziorek B, Haszcz D. Ophthalmic manifestations in Lyme borreliosis [in Polish]. Przegl Epidemiol 2002;56 (suppl 1):85–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fatterpekar GM, Gottesman RI, Sacher M, et al. Orbital Lyme disease: MR imaging before and after treatment—case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:657–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sood SK. What we have learned about Lyme borreliosis from studies in children. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2006;118:638–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Belman AL, Coyle PK, Roque C, et al. MRI findings in children infected by Borrelia burgdorferi. Pediatr Neurol 1992;8:428–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shapiro ED, Seltzer EG. Lyme disease in children. Semin Neurol 1997;17:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Belman AL, Iyer M, Coyle PK, et al. Neurologic manifestations in children with North American Lyme disease. Neurology 1993;43:2609–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kan L, Sood SK, Maytal J. Pseudotumor cerebri in Lyme disease: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Neurol 1998;18:439–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rothermel H, Hedges TR 3rd, Steere AC. Optic neuropathy in children with Lyme disease. Pediatrics 2001;108:477–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith V, Traquina DN. Pediatric bilateral facial paralysis. Laryngoscope 1998;108 (4 pt 1):519–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kacinski M, Zajac A, Skowronek-Bala B, et al. CNS Lyme disease manifestation in children. Przegl Lek 2007;64 (suppl 3):38–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lopez-Alberola RF. Neuroborreliosis and the pediatric population: a review. Rev Neurol 2006;42 (suppl 3):S91–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feder HM Jr. Lyme disease in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:315–26, vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Feder HM Jr, Johnson BJ, O'Connell S, et al. A critical appraisal of “chronic Lyme disease.” N Engl J Med 2007;357:1422–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Donta ST. Late and chronic Lyme disease. Med Clin North Am 2002;86:341–49, vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sigal LH. Persisting complaints attributed to chronic Lyme disease: possible mechanisms and implications for management. Am J Med 1994;96:365–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hurley RA, Taber KH. Acute and chronic Lyme disease: controversies for neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008;20:iv -6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tager FA, Fallon BA, Keilp J, et al. A controlled study of cognitive deficits in children with chronic Lyme disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001;13:500–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marques A. Chronic Lyme disease: a review. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:341–60, vii-viii [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.MacDonald AB. Alzheimer's disease Braak Stage progressions: reexamined and redefined as Borrelia infection transmission through neural circuits. Med Hypotheses 2007;68:1059–64. Epub 2006 Nov 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miklossy J. Chronic inflammation and amyloidogenesis in Alzheimer's disease: role of spirochetes. J Alzheimers Dis 2008;13:381–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.MacDonald AB. Plaques of Alzheimer's disease originate from cysts of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Med Hypotheses 2006;67:592–600. Epub 2006 May 3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meer-Scherrer L, Chang Loa C, Adelson ME, et al. Lyme disease associated with Alzheimer's disease. Curr Microbiol 2006;52:330–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miklossy J, Khalili K, Gern L, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi persists in the brain in chronic lyme neuroborreliosis and may be associated with Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2004;6:639–49, discussion 673–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bransfield RC, Wulfman JS, Harvey WT, et al. The association between tick-borne infections, Lyme borreliosis and autism spectrum disorders. Med Hypotheses 2008;70:967–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fallon BA, Das S, Plutchok JJ, et al. Functional brain imaging and neuropsychological testing in Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25 (suppl 1):S57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fallon BA, Nields JA. Lyme disease: a neuropsychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1571–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schneider RK, Robinson MJ, Levenson JL. Psychiatric presentations of non-HIV infectious diseases: neurocysticercosis, Lyme disease, and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002;25:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vrethem M, Hellblom L, Widlund M, et al. Chronic symptoms are common in patients with neuroborreliosis: a questionnaire follow-up study. Acta Neurol Scand 2002;106:205–08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Aalto A, Sjowall J, Davidsson L, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging does not contribute to the diagnosis of chronic neuroborreliosis. Acta Radiol 2007;48:755–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kurtenbach K, Hanincova K, Tsao JI, et al. Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006;4:660–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]