SUMMARY:

Third branchial cleft cysts (BCCs) are rare entities that represent abnormal persistence of the branchial apparatus. On CT examination, these cysts appear as homogeneous low-attenuation masses with well-circumscribed margins; on MR imaging, they demonstrate variable signal intensity on T1-weighted images and are hyperintense relative to muscle on T2-weighted images. Definitive treatment is surgical excision. We present a case of a third BCC and describe its diagnosis and treatment.

Most cases of third branchial cleft cysts (BCCs) are diagnosed in childhood and show a marked preference for the left side (97%).1 Prenatal diagnosis is uncommon. Here, we present an example of this rare anomaly that was diagnosed prenatally. The embryologic development and radiologic evaluation of third BCCs are discussed.

Case Report

A female neonate was delivered by planned cesarean delivery at 34 weeks' gestation on the basis of the presence of a neck mass resolved by prenatal ultrasonography, consistent in location with a type 3 BCC. At delivery, physical examination revealed no tracheal abnormalities, fistulas, or neck masses, but intraoral examination showed fullness of the posterior oropharynx on the left side. MR imaging examination demonstrated a large cystic structure in the retropharyngeal space, extending from the nasopharynx through the thoracic inlet (Fig 1). On direct laryngoscopy, palpation of the neck produced clear fluid from an opening at the inferior aspect of the left pyriform sinus, and a left type 3 BCC was diagnosed. Cauterization of this opening was performed; however, postoperatively the mass failed to resolve. On day of life (DOL) #22, intraoperative sonography–guided drainage of the cyst was performed for decompression and produced straw-colored fluid and air. Definitive resection was completed on DOL #36. The surgical procedure included a left thyroid lobectomy and excision of a 3 × 3-cm cystic mass adherent to the left thyroid lobe with a tract entering the pyriform sinus. Pathologic evaluation was consistent with a BCC (Fig 2).

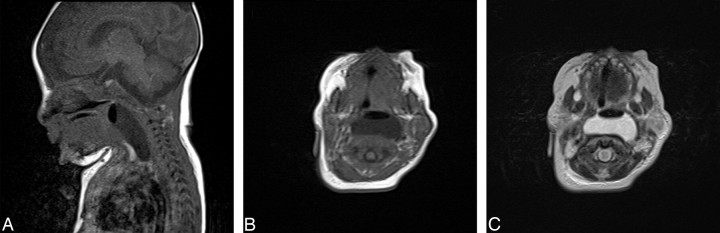

Fig 1.

Sagittal (A) T1 and axial (B) T1-and (C) T2-weighted MR images. A paraglottic and retropharyngeal cystic mass with an air-fluid level is present, displacing the left carotid sheath structures laterally and anteriorly.

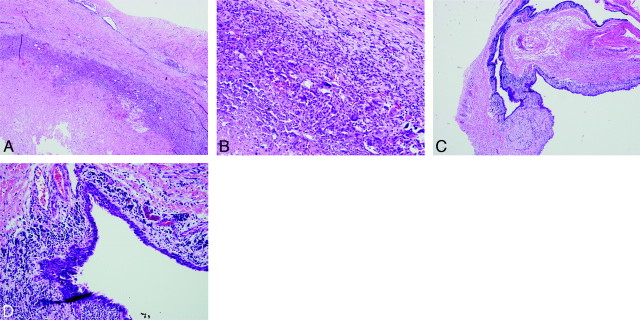

Fig 2.

Photomicrographs (A, low-powered) and (B, high-powered) show rupture of the cyst wall with granulation tissue and foreign-body giant-cell reaction. Photomicrographs (C, low-powered and D, high-powered) demonstrate a cyst lining composed of inflamed squamous mucosa with surrounding lymphoid tissue.

Discussion

Most cystic lesions in infants and children are congenital or developmental in origin and reflect aberrancies in embryogenesis. The differential diagnosis most commonly includes thyroglossal duct (TGD) cysts, lymphatic malformations (LMs), and BCCs. The appropriate radiologic evaluation for these masses depends on their location, extent, and presumed consistency (cystic vs solid). To determine consistency, ultrasonography offers many advantages: it does not require sedation, does not expose the patient to radiation, and can determine easy establishment of whether the lesion is solid or cystic. CT scanning and MR imaging are preferred when the lesion is extensive or when it crosses multiple anatomic spaces.2

A TGD cyst usually presents as a palpable, nontender midline neck mass that elevates with swallowing or protrusion of the tongue. Ultrasonography is the imaging technique of choice for these lesions, which will have a variable appearance (anechoic, homogeneously hypoechoic, or heterogeneous), regardless of the presence of infection or inflammation. On CT examination, uncomplicated TGD cysts are well-defined, low-attenuation masses and, on MR imaging, demonstrate fluid signal intensity.2

LMs are vascular malformations composed of lymph sacs of varying sizes separated by connective tissue stroma. Unlike TGD cysts, LMs typically present in the lateral neck as multiloculated lesions often with fluid-fluid levels indicative of intralesional bleeding. Smaller LMs can be easily examined by ultrasonography to confirm location and extent. However, most LMs are large and require more in-depth imaging.

In uncomplicated multiloculated LMs, ultrasonography shows multiple cystic spaces, CT examination demonstrates low-attenuation cysts that do not enhance, and MR imaging demonstrates fluid-intensity lesions. Hemorrhage will increase echogenicity on ultrasonography, attenuation on CT scan, and signal intensity characteristics on MR imaging. MR imaging is the preferred method to demonstrate intralesional hemorrhage, fluid-fluid levels, and the infiltrative extent of LMs.2

The BCC is a vestige of the branchial apparatus, which appears during the fourth week of gestation as 6 paired sets of arches, each with an associated internal pouch and external cleft.1 Each arch has a corresponding condensation of mesoderm, artery, and nerve,3 with the third arch giving rise to the superior laryngeal constrictor muscles and portions of the hyoid bone, the internal carotid artery, and the glossopharyngeal nerve.4 The dorsal portion of the third branchial pouch forms the inferior aspect of the thyroid gland, whereas the ventral portion gives rise to the thymus.1 The second, third, and fourth clefts combine to give rise to the cervical sinus of His, which eventually obliterates.4 Incomplete obliteration of these spaces results in branchial abnormalities.5

The BCC has no external opening but can occur in conjunction with a sinus or a fistula. Sinuses have an internal opening but no external openings, whereas fistulas have both internal and external openings. A sinus extending from the cyst is the most common presentation. There are 95% of BCCs that arise from the second branchial arch, with the remaining 5% arising from the first, third, or fourth arches, combined.6 Third BCCs are very rare but remain the second most common congenital lesion of the posterior cervical area after LMs7 and can present as asymptomatic masses or produce a variety of symptoms if infected. Definitive treatment of third BCCs is surgical excision.1,2

The close proximity of the third and fourth branchial arches makes distinguishing these 2 abnormalities radiologically difficult. For accurate diagnosis, the relationship of the sinus tract to the superior laryngeal nerve must be determined surgically.1 A third arch sinus arises from the base of the pyriform sinus, courses superior to the superior laryngeal and hypoglossal nerves but inferior to the glossopharyngeal nerve, and travels posterior to the carotid artery. Fourth arch sinuses arise from the apex of the pyriform sinus, course inferior to the superior laryngeal nerve, and track down the tracheoesophageal groove.

Because BCCs are rare and are often confused with other entities, the radiologic diagnosis may be difficult. The superficial location of some of these cysts makes them well-suited for sonography examination. Like LMs, BCCs are anechoic on sonography, but infection and hemorrhage will increase echogenicity.2 CT scan and MR imaging are the imaging modalities of choice to assess the extent and depth of BCCs. On CT examination, they appear as fluid-attenuated masses with well-delineated margins.6 Structures adjacent to the cysts are displaced, but fascial planes are preserved unless a biopsy has been performed or an infection is present. MR imaging demonstrates variable cyst wall thickness and contents that may be hypointense or, in the presence of proteinaceous debris, hyperintense to muscle on T1-weighted images. BCCs are hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Infection can cause rim enhancement,6 mimicking abscesses or lymphadenopathy.8

Location can help to establish a differential diagnosis. In general, TGD cysts are midline, whereas LMs and BCCs are laterally located. A lesion near the external auditory canal or parotid gland is likely to be a BCC, whereas a lesion anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and posterior to the submandibular gland should suggest a second BCC. Posterior cervical space cystic masses are either LMs or third BCCs.2

Histopathologic examination of the lesion excised from our patient confirmed the diagnosis of a third BCC. The associated inflamed squamous mucosa with surrounding lymphoid tissue (Fig 2) is consistent with the typical pathologic findings of a BCC.3,5

In summary, although rare, a third BCC should be considered in neonates and infants with a posterior cervical cystic neck mass. Imaging is essential in the diagnosis and management of these lesions. The definitive treatment requires surgical excision. At surgery, the relationship of the sinus tract to the superior laryngeal nerve and the pyriform sinus will differentiate between third and fourth BCCs.

References

- 1. Houck J. Excision of branchial cysts. Operative Tech Otolaryngol 2005;16:213–22 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koch BL. Cystic malformations of the neck in children. Pediatr Radiol 2005;35:463–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. al-Ghamdi S, Freedman A, Just N, et al. Fourth branchial cleft cyst. J Otolaryngol 1992;21:447–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benson MT, Dalen K, Mancuso AA, et al. Congenital anomalies of the branchial apparatus: embryology and pathologic anatomy. Radiographics 1992;12:943–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cote DN, Gianoli GJ. Fourth branchial cleft cysts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;114:95–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foxx S, Smoker WR, Johnson MH, et al. Pediatric neck masses: solid and cystic. Radiologist 1995;2:331–42 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koeller KK, Alamo L, Adair CF, et al. Congenital cystic masses of the neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 1999;19:121–46; quiz 152–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller MB, Rao VM, Tom BM. Cystic masses of the head and neck: pitfalls in CT and MR interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;159:601–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]