Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

The diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF) remains one of the few uncontested indications for catheter based cerebral angiography. We report our experience of using a commercially available form of time-resolved MR angiography (trMRA) at 3T for the diagnosis and classification of a cranial DAVF compared with the reference standard of digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective review of our patient records identified patients who had undergone trMRA at 3T and DSA for the evaluation of DAVF. The trMRA consisted of whole-head, contrast-enhanced “time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics” (TRICKS) MRA. Image sets were independently reviewed by 3 readers for the presence, location, and classification of a DAVF. The reported result of the DSA was used as the gold standard against which the performance of the trMRA was measured.

RESULTS:

Forty patients were identified who had undergone DSA and trMRA for evaluation of DAVF, yielding a total of 42 cases. On DSA, the results of 7 cases were normal, 15 cases were performed for surveillance of a previously cured fistula, and a new fistula (14) or persistent (6) fistula was found in 20 cases. Of these 20 fistulas, on DSA, 13 were Borden I, 2 were Borden II, and 5 were Borden III. In 93% (39/42) of DAVF cases, the 3 readers were unanimous and correct in their independent interpretation of the trMRA, correctly identifying (or excluding) all fistulas and accurately classifying them when encountered.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this small series, trMRA at 3T seems be a reliable technique in the screening and surveillance of DAVF in specific clinical situations.

The diagnosis of a cranial dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF) (also referred to as a dural arteriovenous shunt) has traditionally been made with catheter-based cerebral intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Although the diagnosis of DAVF may commonly be suspected on planar CT and MR imaging, DSA, with its high spatial and temporal resolution, has been required to confirm the diagnosis and define the lesion. On DSA, the characterization of the fistula is based on the presence or absence of cortical venous reflux (CVR), which, in turn, predicts their benign or malignant nature and thus dictates the management of these vascular lesions.1–5 With the use of modified k-space collection schemes, contrast-enhanced MR angiography (MRA) has acquired a degree of temporal resolution that was previously not possible. One of these commercially available techniques is known as “time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics” (TRICKS).6 The use of time-resolved contrast-enhanced MRA (trMRA) techniques to visualize DAVF has been previously reported.7–13 Although these previous reports demonstrated the promise of the technique, they were limited by a small number of cases, did not include DSA as the reference standard, did not address the issue of CVR, or were performed at 1.5T, limiting the signal-to-noise ratio. We report here our experience with using a technique of whole-head, trMRA at 3T for the diagnosis and classification of DAVF compared with the reference standard of DSA.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study.

Patient Data

We retrospectively reviewed patient records at our institution from June 2006 to December 2007 to identify a subset of patients who had undergone both trMRA and DSA for evaluation of DAVF; this comprised the study population. The reported result of the DSA examination regarding the presence, location, and classification2 of the fistula was used as the criterion standard against which the performance of the trMRA was compared.

Conventional Angiography

We performed catheter-based intra-arterial DSA in all patients by using a dedicated biplane neuroangiography suite (Advantx LCN+; GE Healthcare, Buc, France). All DSA examinations included frontal and lateral views with selective injection of the appropriate internal carotid, external carotid, and vertebral arteries with iodinated contrast medium (Omnipaque 300; GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK).

Time-Resolved, Gadolinium-Enhanced MRA

We performed all trMRA examinations using a 3T MR imaging system (Signa HDx 14.0 M5 software; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wis) with an 8-channel head coil. The method of time-resolved, gadolinium-enhanced MRA used in this study is commercially available and has been previously reported as TRICKS MRA. The TRICKS sequence combines k-space segmentation into central, mid, and peripheral zones with superimposed elliptic centric view ordering. High temporal resolution is achieved by sampling the central zones of the k-space at a more frequent rate than sampling the more peripheral zones. A full description of the technique is available in the literature.6,14 Techniques and scan parameters used to allow for rapid acquisition of multiple 3D volumes (frames) include a short TE of 0.9 ms and a short TR of 2.2 ms, fractional echo acquisition, 2.6-mm section thickness, additional 2.6-mm interpolated sections with a 1.3-mm increment) with zero filling in the section dimension, and parallel imaging method with k-space sensitivity encoding (asset factor of 2.0). In all cases, the 3D volume acquisitions were sagittally oriented with section coverage from ear to ear (approximately 108 sections), with a FOV of 28 × 22.4 cm, matrix of 192 × 192, NEX of 0.75, and flip angle of 20°. A central k-space refresh rate (frame rate equivalent to an effective temporal resolution of the resultant 3D volumes) was prescribed at 1.8 to 2.0 s, dependent on head size and coverage requirements. Subtraction was used for background tissue suppression and improvement of vessel conspicuity. Approximately 36 volumes were prescribed for each patient examination, and total scan time was approximately 1:17, including 0:09 s for the mask. As part of preparation for MR imaging scanning, a commercially available 2-cylinder MR-compatible injector (Spectris; Medrad, Indianola, Pa) was loaded with 15 mL of gadobutrol (Gadovist; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) injected at a rate of 2 mL/s to a total of 15 mL, followed immediately by a flush (chaser) of 30 mL of saline delivered from the second cylinder. Intravenous access was obtained with a 22-gauge intravenous catheter located in an antecubital vein. A very slow infusion (0.5 mL/min) of saline was initiated at the time of intravenous connection and was continued during preliminary imaging until contrast material bolus injection. After acquisition of the mask, the trMRA sequence was initiated simultaneously with the intravenous injection.

Image Processing and Review

All trMRA sequences were transferred to a commercially available workstation (Advantage for Windows, version 4.1; GE Healthcare) for image processing. Each patient's TRICKS examination consisted of 36 frames (3D volumes). Each frame was viewed as sagittal, coronal, and submentovertex whole-volume maximum intensity projections (MIPs); this allowed for subsequent collation of the MIPS of the 3 orthogonal planes into “image loops” each consisting of 36 frames (MIP images). Using the 3 image loops of each patient, the reviewer could easily scroll through the frames to follow the passage of contrast from the very early arterial phase to the late venous phase. We removed all patient-identifying information and transferred the image sets (the 3 loops) of each patient to a PACS viewing workstation (eFilm 2.1.2; Merge Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wis). The remainder of each patient's clinical MR examination, including the postgadolinium T1 imaging, was not part of this study and was not transferred to the viewing workstation. The only images that the readers were asked, and permitted, to review were the provided image (MIP) loops. Three readers—each with experience in interpreting trMRA examinations and each skilled in diagnostic and interventional neuroradiology—independently reviewed the 3 image loops of each patient in a blinded fashion. The 3 image loops of a single patient were reviewed, and the scoring sheet was filled out before the image sets of another patient were reviewed.

Patients were randomly selected with regard to order of review. We asked the readers to record the presence, location, and classification of a fistula on the basis of criteria similar to those established by Borden et al.2 Specifically, 0 indicated “no AVF present”; I, a DAVF that drained into a dural venous sinus without CVR; II, a DAVF that drained into a dural venous sinus with CVR; and III, a DAVF that drained directly into the subarachnoid (leptomeningeal) veins. No attempts were made to define the feeding arteries or morphologic nature of the fistula. The readers were simply asked to identify the presence or absence of a DAVF and, if present, state its general location (eg, “left cavernous, right posterior fossa, left convexity, etc). Also, they were asked to record in a binary fashion whether CVR was present on the basis of the appearance of the trMRA. The results from each reader were tabulated, and a consensus reading was established for each case based on the unanimity of the readers or on most (2/3) of the readers. The results were then compared with the DSA reported result.

Results

Approximately 42,300 neurologic MR examinations were performed at our institution during the specified interval. Of those patients, we identified a subset of 87 patients who had undergone trMRA for evaluation of a DAVF. Of those 87 patients, 40 (mean age, 56 years; male-to-female ratio, 1:1) had also undergone DSA. During the study period, 2 patients underwent complete evaluation for DAVF twice (at the time of diagnosis of a fistula and again at follow-up after treatment), yielding 42 cases investigated for a DAVF in which coincident trMRA and DSA were available. Of these 42 cases, at DSA, 7 yielded normal results, 15 cases were performed for surveillance of a previously cured fistula (and results remained negative), and a DAVF was found in 20 cases. Of these 20 fistulas, at DSA, 13 were Borden I, 2 were Borden II, and 2 were Borden III (examples are illustrated in Figs 1–3). In 4 of the 42 cases, DSA was performed more than 1 year before trMRA, and these cases consisted of previously cured DAVFs that had remained clinically stable. In the remaining 38 cases, the interval between trMRA and DSA averaged 25 days (SD, ± 29 days), with a range of 0 to 93 days.

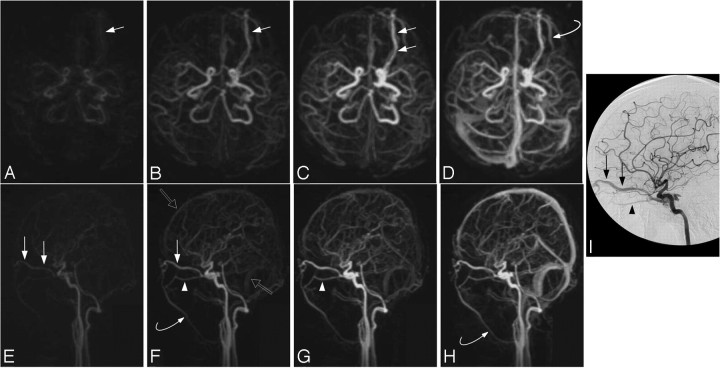

Fig 1.

Case 15. A type I DAVF in a 46-year-old woman with left conjunctival erythema. Submentovertex (A–D) and sagittal (E–H) corresponding MIPs of consecutive whole-head volumes with an effective frame rate of 2 s. Frame A is arbitrarily taken as time zero. I, DSA lateral view of injection into the left internal carotid artery. Rapid arterial phase filling of the left superior (arrows) and inferior (arrowheads) ophthalmic vein as well as filling of the left angular vein of the face (curved arrows) is seen because of a left carotid-cavernous fistula. There is no evidence of CVR. Note the faint amount of signal intensity overlying the superior sagittal and sigmoid sinuses on F (open arrows). This is artifactual signal intensity because of the modified k-space collection scheme of the TRICKS technique (ie, the sharing of peripheral k-space data, some of which is collected well into the venous phase), which results in a small amount of normal venous “contamination” in the final images. This contamination is easily differentiated from pathologic early venous filling because it is not evident in the earlier frames (A and E), nor does it match the intensity of the arteries or the truly abnormal early venous filling (until later frames coincident with normal venous filling as in H).

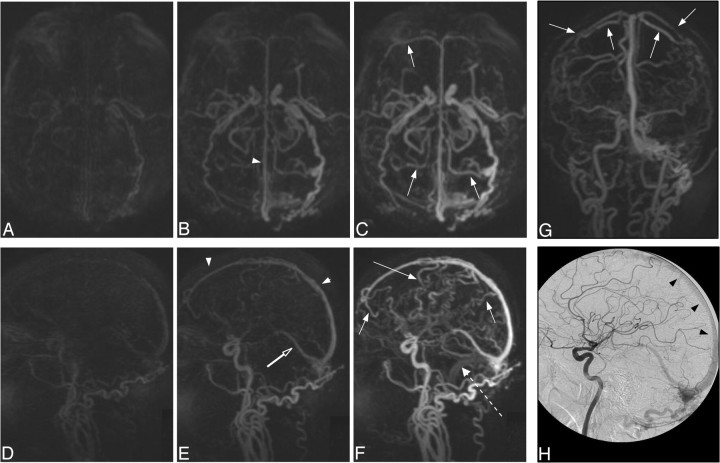

Fig 2.

Case 31. A type II DAVF in a 71-year-old man with a progressive neurologic deficit. Submentovertex (A–C), sagittal (D–F), and anteroposterior (G; frame as C and F) MIPs of whole-head trMRA volumes. H, DSA lateral view of an injection into the left common carotid artery. A DAVF located at the torcula with early arterial phase filling of the superior sagittal sinus (arrowheads), straight sinus (open arrow), and vein of Galen as well as rapid filling of multiple tortuous superficial cortical veins over both cerebral convexities (arrows). Note the differential rate of filling of the superior sagittal sinus and refluxing cortical veins vs the later normal venous phase filling of the left sigmoid sinus (dashed arrow), which fills via the brain.

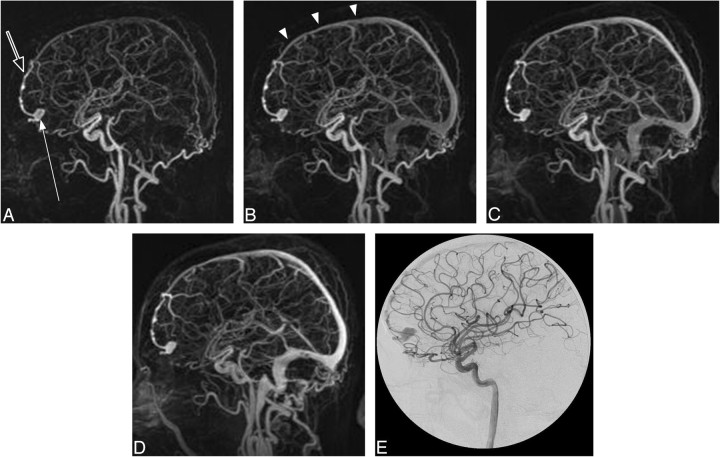

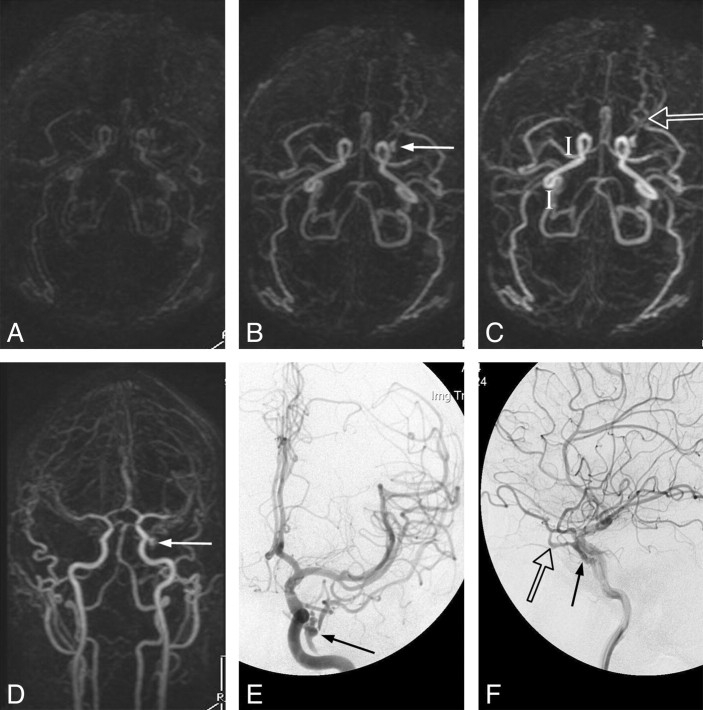

Fig 3.

Case 5. A type III DAVF in a 60-year-old man presenting with an intracranial hemorrhage. A–D, trMRA sagittal MIPs (2-s frame rate) and (E) DSA lateral view from an injection into the left internal carotid artery. There is a DAVF located over the left aspect of the cribriform plate with rapid early arterial phase filling of a subarachnoid venous pouch (arrow), which drains via an abnormal leptomeningeal vein (open arrow) to the superior sagittal sinus (arrowheads).

Regarding the performance of trMRA, use of the “most rule” to derive a consensus result for each case showed that the trMRA interpretation was 100% sensitive and specific compared with DSA for DAVF evaluation. In 39 (93%) of the 42 cases, the 3 readers were unanimous and correct in their independent interpretation of trMRA, correctly excluding and identifying all fistulas and accurately classifying them when encountered. Agreement among the readers was quite high, with a reliability across the readers of 0.94 ± 0.04 (P < .0001). From an individualistic standpoint, the 126 reader evaluations revealed 3 instances (2.4%) in which a reader incorrectly interpreted the trMRA compared with DSA and with the other 2 readers. In 2 of these instances, overclassification of an identified fistula occurred (case 7, reader 3 [Fig 4] and case 23, reader 1). In both of these cases, the reader described CVR, which the other readers and DSA did not identify. In the third instance, a false-negative result occurred (case 13, reader 3) in which the remaining 2 readers correctly identified a type 1 fistula (Fig 5).

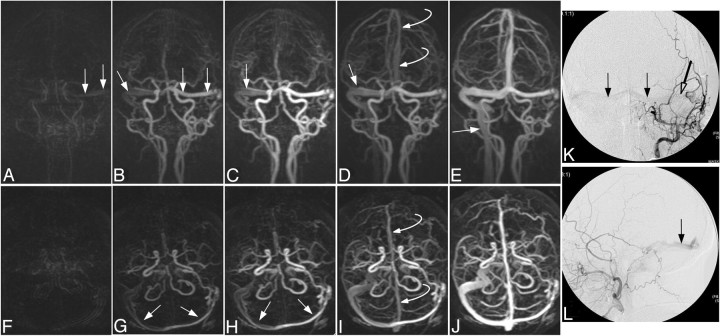

Fig 4.

Case 23, a patient with treated DAVF with residual Borden type I shunt. Anteroposterior (A–E) and submentovertex (F–J) MIPs of consecutive whole-head volumes with an effective frame rate of 2 s. K and L are DSA anteroposterior and lateral views of an injection into the left external carotid artery. A persistent DAVF is located at the left sigmoid sinus, with residual shunt into the left transverse sinus and across the torcula to the right transverse sinus and down the right jugular vein (arrows). The left jugular vein is occluded. Endovascular coils from previous treatment can be seen overlying the left transverse sinus (open arrow) on DSA. Note the normal (later) filling of the superior sagittal sinus at 6 s in Figs D and I (curved arrow). In this case, reader 1 incorrectly suspected CVR.

Fig 5.

Case 13. A type I, low-flow, residual carotid-cavernous fistula in a 55-year-old man after previous embolization. This represents a false-negative result in which one of the readers did not correctly identify the presence of a fistula. Submentovertex (A–C) and anteroposterior (D) MIPs of trMRA whole-head volumes. DSA (E) frontal and lateral (F) views of a left internal carotid injection. A small amount of early filling of the left cavernous sinus (arrow) with truncated outflow to the superior ophthalmic vein (open arrow) is seen on both modalities.

Discussion

Noninvasive imaging modalities, particularly CT angiography (CTA) and MRA, have been gaining acceptance as practical alternatives to DSA for the diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease. This is evident throughout the recent radiologic literature and in the daily practice of neuroradiologic departments. However, DSA has remained the technique of choice for evaluation of patients with a suspected DAVF. DAVFs are commonly very small lesions requiring the high spatial resolution of DSA for their identification. In addition to high spatial resolution, a need for adequate temporal resolution is also warranted because the normal cerebrovascular circuit is 5 to 8 s from the cavernous carotid to the transverse sinus, and one must be able to identify not only the early opacification of a dural sinus, but also reflux into the connecting cortical veins, if present. Aside from its obvious drawbacks of patient discomfort, expense, and risks, DSA is ideal for investigation of DAVFs because of its inherent spatial and temporal resolution as well as that it is performed with selective injections. Therefore, abnormal communications are easily appreciated isolated from the overlying vascular anatomy. Previous reports of trMRA techniques suggested that MRA can play a role in DAVFs; however, these techniques were limited in signal-to-noise ratio and spatial and temporal resolution, as well as areas of coverage.11,13,15 In their case report, Vattoth et al16 used a TRICKS technique at 1.5T, with an 8-s frame rate to visualize a carotid cavernous fistula. However, there was no discussion of CVR. Meckel et al9 showed that, at 1.5T, a trMRA technique applied to a population of 14 patients (9 with a DAVF) resulted in correct identification or exclusion of the fistula and a correct grading of CVR in 77% to 85% of cases. Ziyeh et al8 described success with an early form of trMRA at 3T in identification of vascular malformations of the head and neck.

Our study evaluated the performance of a commercially available form of trMRA optimized for spatial and temporal resolution with whole-head coverage at 3T for the screening and grading of DAVFs in a population of patients in which the prevalence of a fistula was 48% (20/42). The consensus opinion among the readers with use of this form of trMRA (vs DSA as the criterion standard) was 100% sensitive and 100% specific, not only for DAVF identification but for correct grading of the fistula. One of the 3 readers was incorrect on 3 of 42 cases.

Screening a population of patients referred for a suspected DAVF requires reliable imaging directed at identification or exclusion of these lesions. Once identified, the screening imaging examination should also enable accurate preliminary classification of the DAVF as either “benign or aggressive.” The Borden and Cognard classifications have been independently substantiated as the best predictors of subsequent behavior of a DAVF and thus direct the appropriate management of these lesions.3–5,17 With noninvasive imaging, fistulas that demonstrate CVR (Borden type II or III) can be readily identified and referred for endovascular or surgical treatment. A population of patients with DAVFs may be appropriate to observe rather than treat aggressively; this would include patients with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic Borden type I fistulas or the small group of patients with incompletely treated fistulas (in which the fistula was converted from a Borden II or III to a type I).

Unfortunately, the well-founded fear exists that a benign fistula can silently convert to a malignant form, or a previously treated lesion thought to be cured or downgraded can recur, thus unknowingly putting the patient at risk for an intracerebral hemorrhage.10 Therefore, many authors1,9,17 advocate a strategy of continued surveillance of these patients. A reliable noninvasive imaging technique for this purpose would be welcomed. Full definition of the DAVF with complete, detailed identification of all feeding arteries, size and flow of the fistula, and analysis of draining venous pathways was not part of our study and clearly continues to be a task best performed with selective DSA for the purposes of treatment planning. As can be seen from Figs 1 through 5, acquiring a component of time resolution was obtained at the expense of spatial resolution. This sacrifice of spatial resolution inherently limits the ability of TRICKS MRA to define the small feeding arteries of a DAVF.

Our study supports the use of trMRA in the arena of cranial DAVF only for the purposes of screening and surveillance and not as a tool for complete characterization of a fistula. This technique of trMRA does not rely on visualization of feeding arteries but, rather, exploits the obligatory early venous filling to identify fistulas. Moreover, it seems that we can determine whether the early venous filling is confined to a dural venous sinus or if it also involves the cortical and/or abnormal subarachnoid veins.

Limitations of our study include lack of prospective enrollment, variable elapsed interval between DSA and trMRA studies, temporal resolution of the trMRA of 1.8 to 2 s (rather than subsecond resolution as in DSA), and trMRA spatial resolution of approximately 1.4 to 2.6 mm in voxel dimension rather than the submillimeter resolution of DSA. Also, a sample size of 40 patients cannot be said to be completely representative of the spectrum of DAVFs that “occur in the wild.” Most worrisome are the tiny, slow-flowing fistulas that may represent a diagnostic challenge for even DSA (as recently reported by van Rooij et al18) and thus may be “missed” on trMRA. These limitations may be addressed in the near future with further refinement of trMRA techniques that enable greater spatial and temporal resolution.19 Also, multidetector CT angiographic regimens will undoubtedly contribute to this topic in the near future. At our institution, we now use trMRA to screen all patients suspected of harboring a DAVF. When the clinical suspicion for a DAVF is low, ie, the previously treated patient or the patient who presents with tinnitus when there is no objective clinical sign (conjunctival erythema, bruit, or neurologic deficit) and there is no imaging evidence (meningeal enhancement, venous congestion, or “too many vessels”) to suggest the presence of a fistula, we believe that a negative trMRA result obviates the need to perform DSA. However, we continue to strongly advocate for the use of DSA in patients with unexplained objective clinical and imaging signs that suggest a possible vascular lesion irrespective of a negative trMRA result. Patients with unexplained hemorrhage, edema, or “too many vessels” on conventional imaging will continue to require DSA to exclude a DAVF. When the trMRA result is positive in a patient suspected of having a DAVF, the additional step of diagnostic screening with DSA is no longer required. Instead, expedited referral to a neurointerventional center is facilitated where a single, confirmatory, and comprehensive selective DSA can occur for treatment planning.

The small series presented here suggests that trMRA can reliably differentiate a benign from a dangerous fistula. Nonetheless, at our center we continue to suspect that all newly diagnosed cranial DAVFs are Borden type II or III until proven otherwise by DSA. This strategy may change with more experience and improved techniques of CTA and MRA.

Conclusions

In this small series, trMRA at 3T seems to be a reliable technique in the screening and surveillance of DAVFs in specific clinical situations. When results are positive for the presence of a fistula, trMRA seems to be reliable in the identification of CVR.

References

- 1. Cognard C, Gobin YP, Pierot L, et al. Cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulae: clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification of venous drainage. Radiology 1995; 194: 671– 80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borden JA, Wu JK, Shucart WA. A proposed classification for spinal and cranial dural arteriovenous fistulous malformations and implications for treatment. J Neurosurg 1995; 82: 166– 79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davies MA, TerBrugge K, Willinsky R, et al. The validity of classification for the clinical presentation of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulae. J Neurosurg 1996; 85: 830– 37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Dural arteriovenous fistulae with cortical venous drainage: incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 651– 55 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Dijk JM, terBrugge KG, Willinsky RA, et al. Clinical course of cranial dural arteriovenous fistulae with long-term persistent cortical venous reflux. Stroke 2002; 33: 1233– 36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korosec FR, Frayne R, Grist TM, et al. Time-resolved contrast-enhanced 3D MR angiography. Magn Reson Med 1996; 36: 345– 51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coley SC, Wild JM, Wilkinson ID, et al. Neurovascular MRI with dynamic contrast-enhanced subtraction angiography. Neuroradiology 2003; 45: 843– 50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ziyeh S, Strecker R, Berlis A, et al. Dynamic 3D MR angiography of intra- and extracranial vascular malformations at 3T: a technical note. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 630– 34 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meckel S, Maier M, Ruiz DS, et al. MR angiography of dural arteriovenous fistulae: diagnosis and follow-up after treatment using a time-resolved 3D contrast-enhanced technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 877– 84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noguchi K, Kuwayama N, Kubo M, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistula involving the transverse sigmoid sinus after treatment: assessment with magnetic resonance digital subtraction angiography. Neuroradiology 2007; 49: 639– 43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horie N, Morikawa M, Kitigawa N, et al. 2D thick-section MR digital subtraction angiography for the assessment of dural arteriovenous fistulae. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 264– 69 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klisch J, Strecker R, Hennig J, et al. Time-resolved projection MRA: clinical application in intracranial vascular malformations. Neuroradiology 2000; 42: 104– 07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akiba H, Tamakawa M, Hyodoh H, et al. Assessment of dural arteriovenous fistulae of the cavernous sinuses on 3D dynamic MR angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 1652– 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cashen TA, Carr JC, Shin W, et al. Intracranial time-resolved contrast-enhanced MR angiography at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 822– 29 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noguchi K, Melhem ER, Kanazawa T, et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulae: evaluation with combined 3D time-of-flight MR angiography and MR digital subtraction angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 182: 183– 90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vattoth S, Cherian J, Pandey T. Magnetic resonance angiographic demonstration of carotid-cavernous fistula using elliptical centric time resolved imaging of contrast kinetics (EC-TRICKS). Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 25: 1227– 31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Satomi J, van Dijk JM, Terbrugge KG, et al. Benign cranial dural arteriovenous fistulae: outcome of conservative management based on the natural history of the lesion. J Neurosurg 2002; 97: 767– 70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Intracranial dural fistulas with exclusive perimedullary drainage: the need for complete cerebral angiography for diagnosis and treatment planning. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 348– 51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu Y, Kim N, Korosec FR, et al. 3D time-resolved contrast-enhanced cerebrovascular MR angiography with subsecond frame update times using radial k-space trajectories and highly constrained projection reconstruction. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 2001– 04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]