Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Coiling of very small (≤ 3 mm) aneurysms is considered controversial because of technical difficulties and a higher rate of procedural aneurysm ruptures. In this study, we report clinical and angiographic results of coiling of aneurysms 3 mm or smaller in comparison with larger aneurysms in a large, single-center cohort of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: Between 1995 and July 2008, a total of 1295 aneurysms were selectively occluded with coils. Of 1295 aneurysms, 196 (15.1%) in 187 patients were very small. Of 196 aneurysms, 149 (76%) had ruptured and 47 (24%) had not ruptured. There were 51 males (27%) and 136 females (73%). Mean age was 54.7 years (age range, 11–78 years).

RESULTS: Procedural morbidity rate was 2.1% and mortality rate, 1.1%. Procedural rupture occurred in 15 of 196 aneurysms (7.7%). In 13 of 15 procedural ruptures, this had no adverse effect on outcome. Early recurrent hemorrhage of the coiled aneurysm occurred in 2 patients (1.1%). Compared with larger aneurysms, in very small aneurysms more often a procedural rupture occurred (7.7% versus 3.6%; P = .018). Procedural morbidity rate was lower (3.2% versus 5.5%), but this was not significant (P = .26). Retreatment rate consisted predominantly of clipping soon after incomplete coiling and was lower than in larger aneurysms (5.1% versus 10.0%; P = .041). Other characteristics were not significantly different.

CONCLUSIONS: Coiling of very small aneurysms was technically feasible, with good results. Although procedural aneurysm rupture was significantly more frequent in very small aneurysms, this did not lead to increased overall morbidity and mortality rates. Retreatment rate was lower than for larger aneurysms.

Coiling of ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms has become an accepted treatment technique with a better outcome than with surgical clipping. However, coiling of very small aneurysms (2–3 mm) is considered controversial because of technical difficulties and higher complication rates. In the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial, such very small aneurysms were not included, and the conclusion that coiling is the preferred treatment does not apply to these very small aneurysms.1-3 In particular, the higher chance of procedural rupture in recently ruptured aneurysms is considered a drawback, and surgery for these very small aneurysms is often advocated. Although the chance of procedural rupture is higher in very small aneurysms, its effect on outcome is unknown: only a few reports focusing on outcome of coiling of very small aneurysms are available.

The purpose of this study was to report the frequency, clinical results, complications, outcome, and retreatment rate of coiling of aneurysms 3 mm or smaller in a large, single-center cohort of patients. In addition, selected results are compared with those of larger aneurysms.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Between January 1995 and July 2008, a total of 1295 aneurysms were selectively occluded with coils. Of these, 966 (75%) had ruptured and 329 (25%) were unruptured aneurysms. Of 1295 aneurysms, 196 (15.1%) in 187 patients were very small (≤ 3 mm). Nine patients had 2 coiled very small aneurysms. Of 196 aneurysms, 149 (76%) had ruptured and 47 (24%) had remained unruptured. Of 47 unruptured aneurysms, 40 were additional to another ruptured aneurysm, 6 were incidentally discovered, and 1 was symptomatic by mass effect.

Of 187 patients, 51 were male (27%) and 136 were female (73%). Mean age was 54.7 years (median age, 54 years; age range, 11–78 years).

Clinical condition at the time of treatment for 149 patients with a ruptured aneurysm was Hunt and Hess (HH) grade I to II in 113, HH III in 10, and HH IV to V in 26. Timing of treatment after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) was 0 to 3 days in 91 patients, 4 to 14 days in 40 patients, and more than 14 days in 18 patients. Delayed treatment after SAH was caused by patients' delay or by referral delay. The locations of 196 aneurysms were the anterior communicating artery (73 aneurysms), posterior communicating artery (22 aneurysms), middle cerebral artery (20 aneurysms), pericallosal artery (15 aneurysms), carotid tip (13 aneurysms), posterior inferior cerebellar artery (13 aneurysms), basilar tip (12 aneurysms), superior cerebellar artery (10 aneurysms), anterior choroidal artery (6 aneurysms), posterior cerebral artery (6 aneurysms), ophthalmic artery (4 aneurysms), anterior inferior cerebellar artery (1 aneurysm), and cavernous sinus (1 aneurysm).

Coiling Procedure

Coiling of aneurysms was performed on a biplane angiographic unit (Integris BN 3000 Neuro; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) with the patient under general anesthesia. Aneurysmal size was defined as the maximal aneurysm diameter and was measured on 3D angiography in 175 of 196 aneurysms. In the remaining 21 aneurysms, size was visually estimated from comparison with the carotid or basilar artery and the size of the first inserted coil. Aneurysmal size varied from 1.8 to 3.4 mm. Ruptured aneurysms smaller than 2.0 mm with good HH grade were preferably clipped. In poor-grade aneurysms smaller than 2.0 mm, coiling was only performed when the aneurysm was judged to be able to accommodate a 1.5-mm coil. During the study period, several types of 1.5- to 3-mm coils were used: Guglielmi detachable coils (GDC; 10 Soft and UltraSoft; Boston Scientific, Fremont, Calif), Trufill DCS mini complex coils (Cordis, Miami, Fla), and Nexus coils and Axium coils (ev3, Irvine, Calif). In the beginning of the study period, during coiling 2500 U of heparin was administered, both in the ruptured and unruptured aneurysms. Heparin was continued intravenously or subcutaneously for 48 hours after the procedure, followed by low-dose aspirin for 3 months orally. Later in the study period, in ruptured aneurysms no anticoagulation was administered, apart from heparinized saline catheter flush. Initial angiographic results of coiling were dichotomized as adequate occlusion (complete occlusion or small neck remnant) and incomplete occlusion.

Procedural Complications

Procedural complications (aneurysm rupture or thromboembolic events) of coiling leading to death or neurologic disability at the time of hospital discharge were prospectively recorded in our data base. For patients who were comatose, thromboembolic complications were considered to have caused a neurologic deficit if this was either clinically evident or if there were infarctions on subsequent CT scans in the territory of the involved vessel. After a procedural rupture, any adverse outcome was considered to be caused by this rupture, also in patients in poor clinical condition at the time of treatment and in patients in whom vasospasm or hydrocephalus had developed afterward. Procedural rupture in poor-grade patients who subsequently died during hospital admission was thus considered as procedural mortality. All procedural aneurysm ruptures, independent of clinical consequences, were recorded.

In the event of a procedural rupture with extravasation of contrast material, heparin was instantly reversed with protamine, and coiling was continued until the aneurysm was occluded and the bleeding had stopped. A microballoon to control the bleeding was never used. In patients whose condition was unstable, urgent ventriculostomy was performed directly after coiling.

Supporting Devices

Ten aneurysms were coiled with balloon assistance, and 2 aneurysms were coiled after stent placement (Enterprise; Cordis).

Clinical and Angiographic Follow-up

Patients who survived the hospital admission period were scheduled for a follow-up visit at the outpatient clinic 6 weeks after treatment and for follow-up angiography after 6 months. In most of the study period, no additional imaging follow-up was scheduled when the aneurysm was adequately occluded at 6 months. Additional treatments and recurrent hemorrhage during follow-up were recorded. Neurologic status according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) was evaluated at 6 months and was categorized as independent (GOS 4 and 5), dependent (GOS 3), and death (GOS 5). Results of follow-up angiography were classified in the same way as for initial angiographic results.

Data Analysis and Comparison

The following clinical and imaging characteristics of 187 patients with 196 aneurysms 3 mm or smaller were compared with those of the remaining 1006 patients with 1099 aneurysms 4 mm or larger: age, sex, rupture status, aneurysm location in 4 categories (anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery, carotid artery, and posterior circulation), use of supporting devices, complications, procedural ruptures, and retreatment rate during follow-up. The χ2 test was used for comparison of proportions, and the t test was used for comparison of means.

Results

Initial Angiographic Results

Initial aneurysm occlusion after coiling was adequate in 186 aneurysms and incomplete in 10 aneurysms. Six of 10 incompletely occluded aneurysms had recently ruptured and were clipped soon after coiling. The other 4 incompletely occluded aneurysms were unruptured.

Procedural Complications

Procedural complications leading to morbidity occurred in 4 patients (2.1%; all thromboembolic complications) and complications leading to mortality in 2 patients (1.1%; both procedural ruptures). Complication rate was 3.2% (6/187, 95% confidence interval, 1.3%–7.0%). Five of 6 complications occurred in patients with ruptured aneurysms. In 1 patient with an unruptured 3-mm middle cerebral artery aneurysm, a thromboembolic complication resulted in permanent dysfunction involving the right arm.

Procedural rupture occurred in 15 of 196 aneurysms, all in recently ruptured aneurysms. In 13 of 15 procedural ruptures, this complication had no adverse effect on outcome. In Table 1, different aspects of procedural rupture in the 196 very small aneurysms are compared with the 1099 larger aneurysms.

Table 1:

Comparison of procedural ruptures in 196 very small aneurysms and 1099 larger aneurysms

| 196 Aneurysms ≤ 3 mm in 187 Patients | 1099 Aneurysms ≥ 4 mm in 1006 Patients | Total 1295 Aneurysms in 1193 Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural ruptures | 15 (7.7%) | 36 (3.6%) | 51 (3.9%) |

| Ruptured aneurysms | 15 (100%) | 32 (88.9%) | 47 (92.2%) |

| Poor condition at treatment (HH III–V) | 3 (20%) | 15 (41.7%) | 18 (35.3) |

| Poor outcome (GOS 1–3) | 5 (33.3%) | 11 (30.6%) | 16 (31.4%) |

Note:—HH indicates Hunt and Hess grade; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Clinical Outcome at 6 Months

At 6-month follow-up, 163 patients were independent, 9 patients were dependent in a nursing home, and 15 patients had died. All 9 dependent patients had ruptured aneurysms, and neurologic deficit was mainly caused by thromboembolic complications in 2 and by ischemic lesions of vasospasm in 7. Causes of death in the 15 patients were procedural rupture in 2, complications of SAH in 10, early recurrent hemorrhage of the coiled aneurysm in 2 (after 7 days and 10 days), and complications of surgery of another aneurysm in 1.

Recurrent Hemorrhage from the Coiled Aneurysm

Early recurrent hemorrhage of the coiled aneurysm occurred in 2 patients4: The first patient, a 53-year-old man in poor clinical condition after rupture of a 3-mm anterior communicating artery aneurysm with a large intracerebral hematoma, experienced 2 rebleedings, the first 10 days after initial coiling and the second 20 days after second coiling. Initially, the aneurysm seemed completely occluded, but it progressively enlarged in the following weeks. It is not clear whether the recurrent enlargement of the aneurysm lumen in this patient was caused by resolution of thrombus within a preexistent larger aneurysm or by resolution of thrombus in an adjacent pseudoaneurysm in the hematoma. He eventually died 3 months after admission of medical complications. The second patient was a 26-year-old man in poor clinical condition after rupture of a 3-mm anterior communicating artery aneurysm that was incompletely occluded. After 7 days, this patient died of recurrent hemorrhage.

Angiographic Results at 6-Month Follow-up

Of 196 aneurysms, 158 had 6-month follow-up angiography. In 38 aneurysms in 38 patients, no follow-up angiography at 6 months was performed for the following reasons: deceased (15 patients), clipping soon after coiling (5 patients), dependent in a nursing home (5 patients), age older than 75 years (3 patients), refusal (6 patients), and follow-up angiography scheduled (4 patients).

Of 158 aneurysms, 10 were incompletely occluded. Four of these 10 had increased in size. Additional coiling was attempted in 5 aneurysms and was successful in 3. The 7 incompletely occluded aneurysms are occluded for 70% to 80%, and additional treatment is judged not indicated.

Retreatment Rate

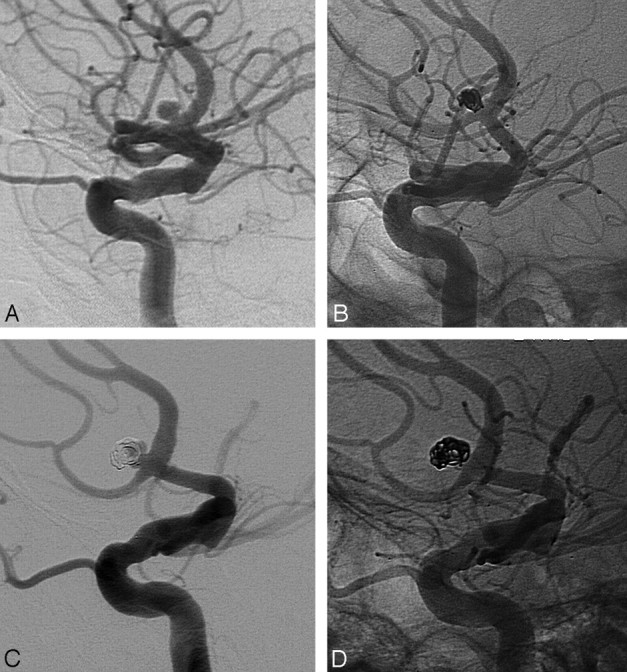

Six aneurysms were clipped soon after incomplete coiling. One aneurysm was additionally coiled twice after early recurrent hemorrhage. Three aneurysms were additionally coiled after reopening at 6 months. Retreatment rate was 4.6% (9/196; 95% CI, 2.3%–8.6%). All 4 aneurysms that were additionally coiled had reopened by luminal enlargement and not by compaction (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

A 3-mm ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm in a 58-year-old woman. A and B, Small aneurysm before (A) and after (B) coiling. C, Reopening at 6-month follow-up by enlargement of the aneurysm. D, Result after additional coiling.

Comparison with Aneurysms 4 mm or Larger

Results of comparison of clinical and imaging characteristics of 187 patients with 196 aneurysms 3 mm or smaller with those of the remaining 1006 patients with 1099 aneurysms 4 mm or larger are displayed in Table 2. Very small aneurysms were significantly more often located on the anterior cerebral artery and less often on the carotid artery. In very small aneurysms, more often a procedural rupture occurred (7.7% versus 3.6%), and retreatment rate was lower (5.1% versus 10.0%). All other characteristics were not significantly different.

Table 2:

Comparison of characteristics of 196 very small aneurysms and 1099 larger aneurysms

| 196 Aneurysms ≤ 3 mm in 187 Patients | 1099 Aneurysms ≥ 4 mm in 1006 Patients | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 136 (73) | 780 (78) | .15 |

| Mean age (y) | 54.7 | 53.0 | .073 |

| Ruptured aneurysms (%) | 149 (76) | 817 (74) | .62 |

| Location (%) | |||

| Anterior cerebral artery | 88 (45) | 355 (32) | .0005 |

| Middle cerebral artery | 20 (10) | 119 (11) | .77 |

| Carotid artery | 46 (24) | 352 (32) | .032 |

| Posterior circulation | 42 (21) | 273 (25) | .267 |

| Procedural mortality (%) | 2 (1.1) | 21 (2.1) | .53 |

| Procedural morbidity (%) | 4 (2.1) | 34 (3.4) | .48 |

| Procedural ruptures (%) | 15 (7.7) | 36 (3.6) | .018 |

| Retreatment rate | 4.6% (9/196) | 10.0% (110/1099) | .023 |

| Additional coiling | 4 | 95 | |

| Additional clipping | 6 | 15 | |

| Supporting devices (%) | 12 (6.1%) | 116 (10.6%) | .070 |

| Balloon | 10 | 81 | |

| Stent | 2 | 19 | |

| TriSpan | 0 | 16 |

Discussion

In this large cohort of patients, coiling of aneurysms 3 mm or smaller was technically feasible with a lower complication rate than for the larger aneurysms. Although procedural aneurysm rupture was significantly more frequent in very small aneurysms, this did not lead to increased overall morbidity and mortality rates. Most procedural ruptures remained without clinical sequelae.

Retreatment rate for very small aneurysms was significantly lower than for larger aneurysms. Most retreatment consisted of surgical clipping performed shortly after incomplete coiling. Additional coiling after reopening at follow-up was very infrequent. Aneurysm reopening needing additional coiling was by luminal enlargement only and not by coil compaction. Enlargement of the aneurysm lumen can be the result of resolution of intraluminal thrombus or of resolution of thrombus in a pseudoaneurysm in an adjacent intraparenchymal hematoma, especially in small anterior communicating artery aneurysms.4

Very small aneurysms were common and comprised 15% of all coiled aneurysms at our institution. Very small aneurysms presented equally often after rupture as the larger ones. The location was significantly more common on the anterior cerebral artery (anterior communicating and pericallosal arteries) and less common on the carotid artery.

In the technical sense, coiling of very small aneurysms is more challenging than coiling of larger aneurysms.5-7 Prevention of rupture is essential. A smaller size of the aneurysmal sac restricts the freedom of movement for microcatheter and coil positioning. Unexpected forward catheter movement by a few millimeters could lead to rupture in the more confined lumen of a small aneurysm, whereas this would be trivial in a larger one. In smaller aneurysms, the probability of inadvertently positioning the coil or microcatheter in the vicinity of the initial rupture site is higher. In general, we positioned the tip of the microcatheter just beyond the neck in the aneurysmal sac while deploying the first coil loops. Then, the catheter was withdrawn until the tip was just outside of the aneurysmal neck in the parent artery to deploy the following loops. When the last loop entered the aneurysmal sac, the catheter tip was pulled back farther outside of the neck to allow for the stiff detachment zone (1.2–2.8 mm long depending on the type of coil5) to protrude from the tip in the parent vessel and not in the aneurysmal sac.

After detachment, the tip of the microcatheter usually reentered the aneurysm neck automatically when the geometry of vessels was favorable. We preferred to occlude a small aneurysm with just 1 coil and strived to choose the most appropriate coil length between 1 and 8 cm that would accommodate and occlude the aneurysm. When a procedural rupture occurred, we immediately reversed heparin with protamine and continued coiling until the aneurysm was occluded. Extravasation of contrast usually stops within seconds to minutes. Clinical consequences of procedural rupture may vary from no sequelae to rapid death.6-10 In our experience, vital signs after a rupture as recorded by the anesthetist can be, to some extent, predictive of outcome: when no change in heart rate and blood pressure is registered, the outcome usually will be good. On the other hand, when heart rate and blood pressure change rapidly in combination with sudden (pain-induced) patient movement needing instant adjustment of medication by the anesthetist, the outcome usually is unfavorable. Another bad omen is acute local vasospasm and persistent flow restriction on angiography as a result of an increase in intracranial pressure.

In our series, in very small aneurysms the procedural rupture rate was more than twice as high as in larger aneurysms. After rupture, approximately one third of patients had a poor outcome, both in very small and larger aneurysms. It must be noted that attribution to poor outcome of procedural rupture in poor-grade patients is hard to establish. We allocated any adverse outcome in patients with procedural rupture to the rupture only, though some poor-grade patients would have probably had a poor outcome anyway. Compared with other published reports, overall procedural rupture rate and the proportion of a good outcome after rupture in this series are in the same range.6-10

Recently, the routine positioning of an adjunctive uninflated compliant balloon at the side of the aneurysm neck to stop hemorrhage should a rupture occur has been advocated on the basis of a small series of patients with procedural rupture during coiling of very small aneurysms.6,7 In our opinion, an adjunctive balloon makes the procedure more complicated: positioning the balloon catheter in small arteries such as the A1or A2 is technically challenging and time consuming, with an additional risk for (thromboembolic) complications. The possible beneficial effect of having a balloon in place on the outcome should outweigh the additional risks. This is not yet clarified and should be the subject of additional study.

Conclusions

Coiling of very small aneurysms was technically feasible, with good results. Although procedural aneurysm rupture was significantly more frequent in very small aneurysms, this did not lead to increased overall morbidity or mortality rates. Retreatment rate was lower than for larger aneurysms.

References

- 1.Cloft HJ, Kallmes DF. Cerebral aneurysm perforations complicating therapy with Guglielmi detachable coils: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:1706–09 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group: International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1267–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki S, Kurata A, Ohmomo T, et al. Endovascular surgery for very small ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Technical note. J Neurosurg 2006;105:777–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sluzewski M, van Rooij WJ. Early rebleeding after coiling of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: incidence, morbidity, and risk factors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1739–43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim YC, Kim BM, Shin YS, et al. Structural limitations of currently available microcatheters and coils for endovascular coiling of very small aneurysms Neuroradiology 2008;50:423–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen TN, Raymond J, Guilbert F, et al. Association of endovascular therapy of very small ruptured aneurysms with higher rates of procedure-related rupture. J Neurosurg 2008;108:1088–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanzino G, Kallmes DF. Endovascular treatment of very small ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2008;108:1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doerfler A, Wanke I, Egelhof T, et al. Aneurysmal rupture during embolization with Guglielmi detachable coils: causes, management, and outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:1825–32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brisman JL, Niimi Y, Song JK, et al. Aneurysmal rupture during coiling: low incidence and good outcomes at a single large volume center. Neurosurgery 2005;57:1103–09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tummala RP, Chu RM, Madison MT, et al. Outcomes after aneurysm rupture during endovascular coil embolization. Neurosurgery 2001;49:1059–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]