Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Chordoma is a relatively rare tumor of the skull base and sacrum thought to originate from embryonic remnants of the notochord. Chordomas arising from the skull base/clivus are typically locally aggressive with lytic bone destruction. When chordomas occur in an extraosseous location, they may mimic other lesions of the nasopharynx. We present 5 cases of primarily extraosseous chordoma involving the nasopharynx in an effort to improve the preoperative diagnosis of this rare tumor. In addition, we review regional notochordal embryology to explain this variant tumor location.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: We reviewed the clinical and imaging data of 5 pathologically proved cases of extraosseous chordoma of the nasopharynx seen or reviewed at our institution during the last decade. All cases had both CT and MR imaging. The study had institutional review board approval.

RESULTS: The primary clinical complaint in the 5 patients with extraosseous nasopharyngeal chordoma was nasal obstruction. The extraosseous chordomas were centered in the nasopharynx. Bony lytic changes along the anterior surface of the clivus were seen on 5 of 5 CT studies. A midline sinus tract was seen in 3 of 5 patients. MR imaging showed heterogeneous hyperintense T2 signal intensity (5/5).

CONCLUSIONS: Extraosseous nasopharyngeal chordoma is a rare but important lesion to be considered in the differential diagnosis of nasopharyngeal masses. When a midline nasopharyngeal mass is found with an associated clival sinus tract, extraosseous chordoma moves to the top of the differential diagnosis list. Complete removal of the soft-tissue tumor and the clival sinus tract is the treatment of choice in such cases.

Intracranial chordomas are relatively rare locally aggressive tumors thought to originate along the course of the embryonic remnant of the notochord.1 The most common location for chordoma is in the sacrum; however, the skull base/clivus region is the second most common location along the course of the notochord.1 Rarely, skull base chordomas may occur in an extraosseous location.2 When this occurs, chordomas may mimic other lesions of the nasopharynx. These extraosseous lesions are atypical relative to the usual presentation of clival chordoma due to their nasopharyngeal location. It is important to consider extraosseous chordoma in the differential diagnosis of tumors in the nasopharynx because it requires a very different treatment plan and carries its own unique prognosis. In this retrospective review, we analyze the clinical and radiologic data of 5 patients with extraosseous chordoma in an effort to improve the preoperative diagnosis of this rare tumor. In addition, we review the regional notochordal embryology to explain this variant tumor location.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained. We retrospectively reviewed all imaging studies of patients who had pathologically proved extraosseous chordomas that were treated or reviewed at our institution during the last 10 years, 1997–2007.

Each patient underwent both CT and MR imaging. CT was performed in 3-mm sections. Reformatted images were also available in 3 of 5 cases. Four of 5 were contrast-enhanced CT studies, whereas 1 was a bone-only CT. All MR imaging included axial, sagittal, and coronal T1 sequences; axial and coronal T2 with fat saturation; and axial, sagittal, and coronal postcontrast images with fat saturation. All imaging studies were reviewed by 2 senior neuroradiologists.

Clinical information was compiled via a retrospective chart review. Clinical data included demographic information, presenting features, treatment, and follow-up.

Results

Five patients, 8–65 years of age (mean, 42.8 years), had pathologically proved extraosseous chordomas. The male-female ratio was 1:1.5. Three of 5 patients presented with a sensation of a mass in the nasopharynx. The remaining 2 patients presented with a history of nasal obstruction. All patients underwent surgical resection. One of these patients received adjuvant proton beam therapy. Recurrence occurred intracranially along the clivus sinus tract in 1 of the 5 patients. The conditions of the other 4 are currently stable, without recurrence.

Four of 5 chordomas were midline with superior extension into the sphenoid sinus and anterior extension into the nasopharynx. One of the 5 lesions demonstrated preferential extension laterally into the left parapharyngeal space and left maxillary sinus.

CT of the extraosseous chordomas showed a lobular soft-tissue mass centered in the nasopharynx with scalloping of the adjacent anterior margin of the clivus in all cases (Fig 1). All (5/5) lesions show lytic changes with a subtle sclerotic margin. Five of 5 lesions were heterogeneous but hypoattenuated relative to adjacent muscle. Two of the 5 lesions demonstrated dystrophic calcifications within the tumor matrix (Fig 2). In 3 of 5 cases, a well-defined tract was seen extending into the midline clivus, thought to represent the medial basal canal (Fig 2). A narrow zone of transition with a sclerotic margin was seen around the tract in all cases.

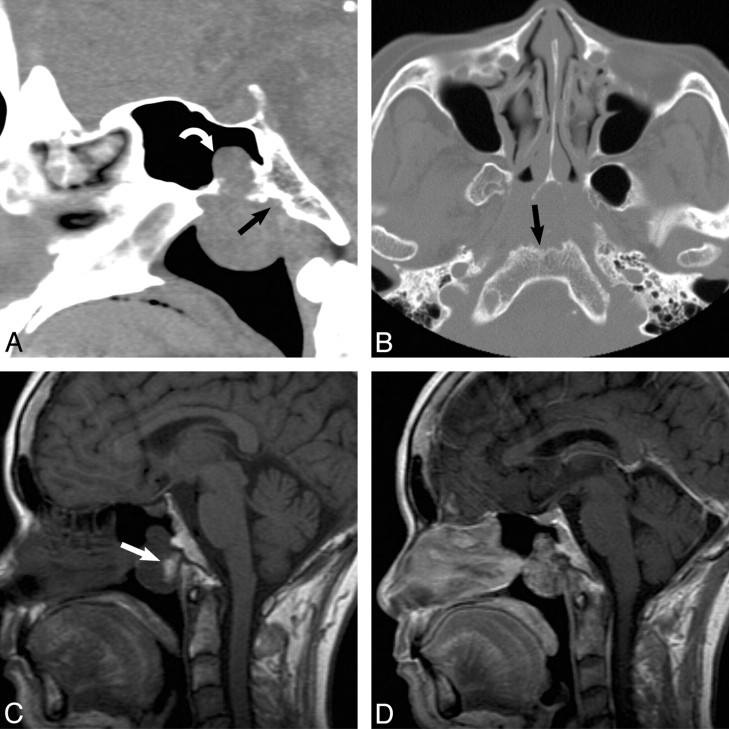

Fig 1.

A, A 65-year-old woman presented with nasal obstruction. Findings show atypical CT appearance of a pathology-proved extraosseous nasopharyngeal chordoma. Sagittal noncontrast CT scan shows a lobulated mass centered in the nasopharynx with superior extension into the sphenoid sinus (curved arrow) and focal erosion of the anterior clivus (black arrow). B, Axial bone CT scan shows a lobulated soft-tissue mass centered in the nasopharynx, with scalloping of the anterior margin of the clivus. Note the lytic appearance with a sclerotic margin (black arrow). C, Sagittal T1-weighted MR image shows a heterogeneous nasopharyngeal mass with a focal area of T1 hyperintensity (arrow) thought to represent blood products or proteinaceous debris. D, Sagittal T1-weighted MR image with contrast shows heterogeneous enhancement of the mass, which is an enhancement pattern seen in both extraosseous and typical skull base chordomas.

Fig 2.

A 56-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of nasal obstruction. Axial noncontrast CT scan shows dystrophic calcification and a midline sinus tract (arrow), which can help with the preoperative diagnosis of extraosseous nasopharyngeal chordoma. This sinus tract is thought to represent tumor extending into the medial basal canal.

On MR imaging, the lesions were predominantly T1 hypointense relative to muscle. Scattered throughout the tumors were areas of mildly hyperintense T1 signal intensity (Fig 1). Following contrast administration, there was heterogeneous enhancement in all 5 cases. Four of 5 lesions demonstrated heterogeneous avid enhancement. Enhancement was seen predominantly in the solid portions of the tumor and along internal septations. One of 5 lesions showed peripheral enhancement.

On T2-weighted sequences, 5 of 5 cases demonstrated heterogeneous hyperintense signal intensity. Scattered areas of very high T2 signal intensity were noted, but all lesions were predominantly mildly hyperintense relative to muscle and less hyperintense compared with CSF. The internal septations on T2-weighted imaging were all uniformly hypointense (Fig 3). Three of the 5 lesions demonstrated a sinus tract extending from the predominant mass lesion posteriorly into the midline clivus (Fig 4). The sinus tract, thought to represent the medial basal canal, was T2 hyperintense in all cases. This sinus tract did not demonstrate enhancement on postcontrast sequences.

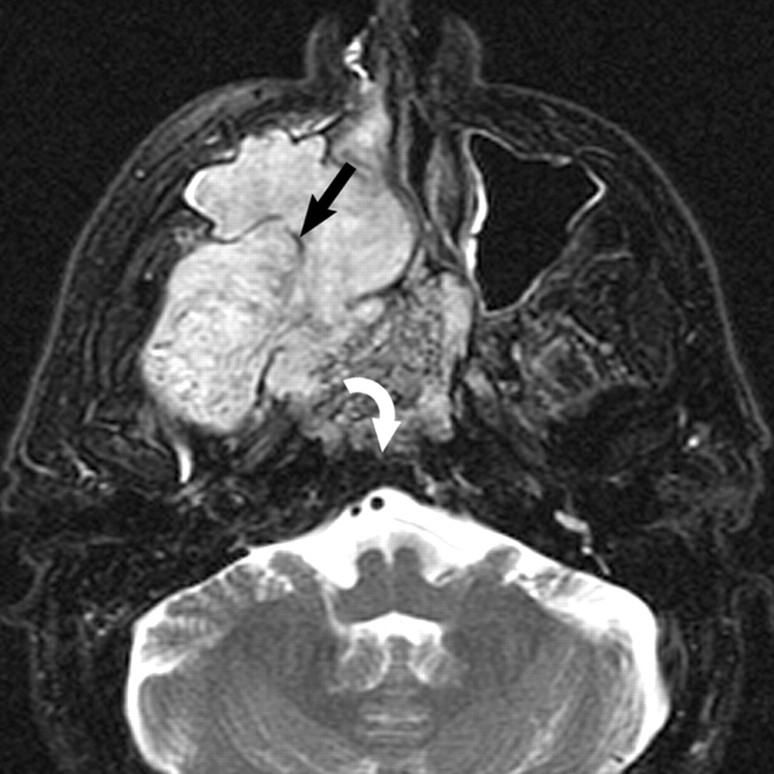

Fig 3.

A 53-year-old man presented with dryness of mouth and difficulty breathing. Axial T2-weighted MR image with fat saturation shows a locally invasive heterogeneously hyperintense mass with internal septations (black arrow) centered in the nasopharynx, with invasion of the right masticator space, nasal cavity, and maxillary sinus. Note involvement of the anterior clivus (curved arrow), which may help preoperatively to diagnose this lesion as an extraosseous nasopharyngeal chordoma.

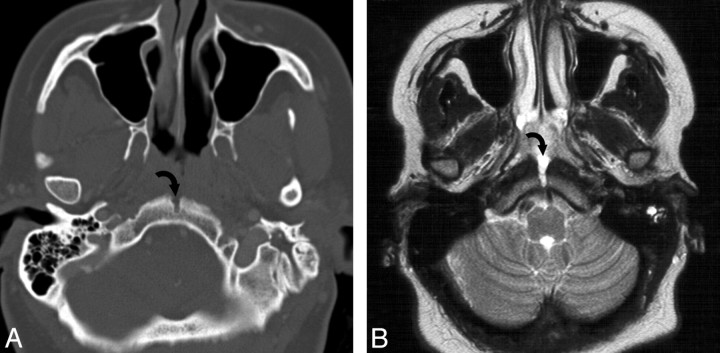

Fig 4.

A, A 32-year-old woman presented with a mass in the nasopharynx. MR imaging shows a midline sinus tract extending into the clivus of a pathologically proved extraosseous nasopharyngeal chordoma. Axial bone CT scan shows a midline tract (curved arrow) representing the extension of the extraosseous chordoma into the medial basal canal. B, Axial T2-weighted MR image shows the hyperintense midline sinus tract (curved arrow) extending posteriorly from the nasopharyngeal mass. Note fluid in the left mastoid air cells secondary to obstruction of the eustachian tube due to a nasopharyngeal chordoma.

Discussion

Chordomas account for 1% of all intracranial tumors.1-4 Intracranial chordomas generally occur in the vicinity of the clivus, often in the region of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis. There have been case reports of extraosseous chordomas in the literature, but none have been reported in the nasopharynx, as defined in our series.2,3 It is important to consider extraosseous chordoma in the differential diagnosis of tumors in the nasopharynx because it requires a very different treatment plan and carries its own unique prognosis.

The cases we present are variants of typical clival chordomas in that they were primarily located in the nasopharyngeal soft tissues. Due to the extraosseous location of these lesions, the typical lytic changes in the clivus are absent; thus, the initial diagnosis is difficult. The aggressive features of chordomas, however, are evident in our series with lytic changes along the proximal osseous structures, such as the superficial surface of the clivus and bones of the posterior sinonasal region. Most of our patients had a nasopharyngeal mass with mass effect and scalloping of the anterior margin of the clivus. Most interesting, our patients presented with symptoms referable to their location in the nasopharynx in contradistinction to typical chordomas, which present with neurologic symptoms and cranial neuropathies.1

Chordomas are thought to arise from physaliphorous cells as described by Virchow.5 The notochord is a primitive cell line around which the skull base and axial skeleton develop. In the cases we present, the finding of a sinus tract leading from the soft-tissue component of the chordoma into the clival bone is a critical clue in differentiating extraosseous chordoma from other more common nasopharyngeal tumors. This observation is clinically significant because as is demonstrated in 1 of our patients, tumor recurrence can result from incomplete excision of the sinus tract if not identified preoperatively.

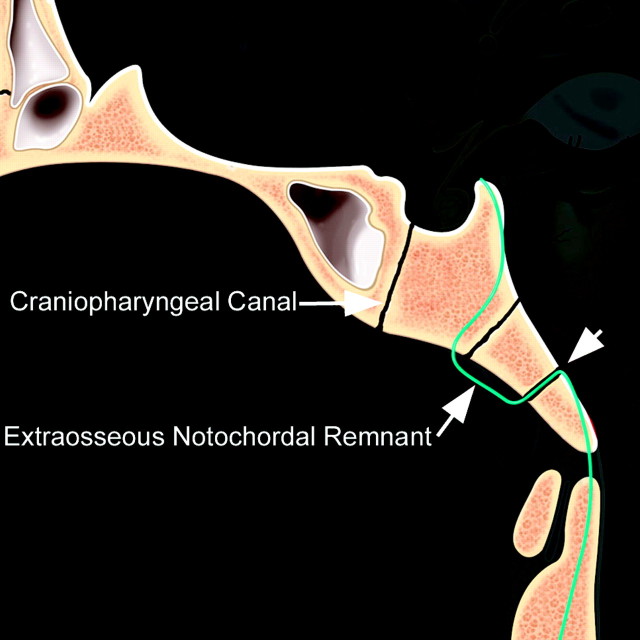

The sinus tract identified in this case series is believed to be the medial basal canal (canalis basilaris medianus) (Figs 5 and 6). The medial basal canal is considered the cephalad exit tract of the notochord as it moves from its intraclival location ventrally into the midline nasopharyngeal soft tissues. Nasopharyngeal extraosseous chordoma arises in the extraosseous nasopharyngeal soft tissues and may or may not have a smaller intraosseous component along the course of the medial basal canal.6

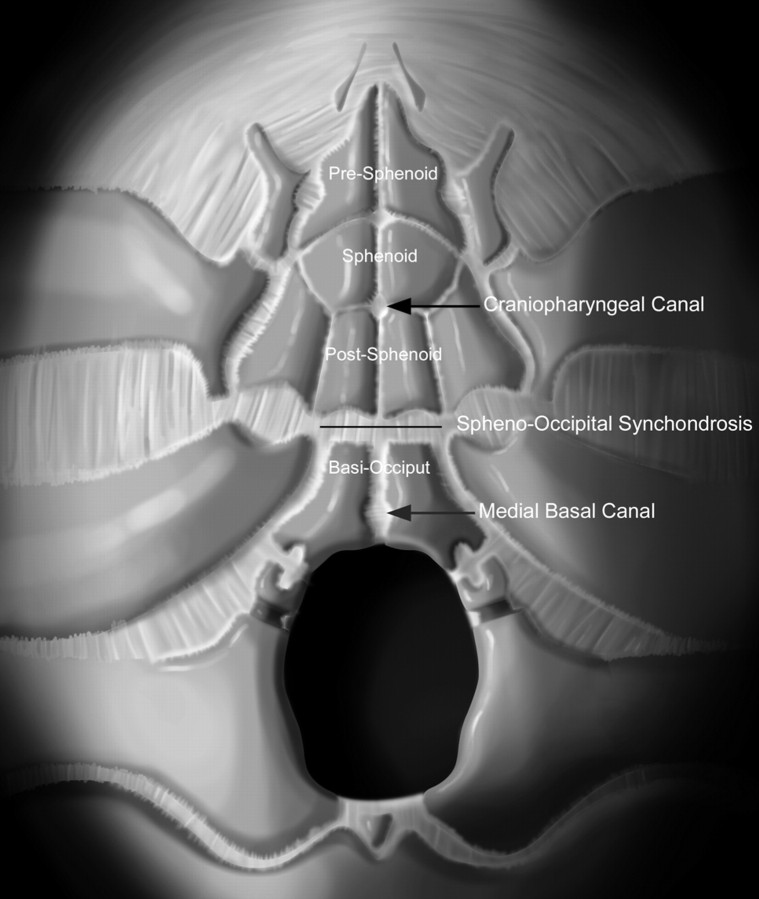

Fig 5.

Graphic drawing of developing skull base ossification centers. Note that the craniopharyngeal canal is anterior to the spheno-occipital synchondrosis, whereas the medial basal canal (canalis basilaris medianus) is posterior to the synchondrosis. Reproduced with permission from Amirsys.

Fig 6.

Sagittal graphic drawing shows the expected location of the notochordal remnant (blue line). Note the relationship of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis between the craniopharyngeal canal and the medial basal canal (short arrow). Extraosseous chordomas appear to arise from the extraosseous notochordal remnant. If these chordomas arise inferiorly, they may extend into the medial basal canal. Reproduced with permission from Amirsys.

One common vestigial embryonic tract not to be confused with the medial basal canal is that of the craniopharyngeal canal. The cranial extent of this tract is situated between the ossification centers of the sphenoid bone in the pediatric patient and thus slightly more cranial than the most cranial extent of the notochord (Fig 6).6,7 The embryology and development of the craniopharyngeal canal is debated but is generally accepted as a tract connecting the nasopharynx and the pituitary fossa. Lesions in the nasopharynx associated with the craniopharyngeal canal are different from nasopharyngeal lesions associated with the medial basal canal.8 Therefore this anatomic distinction has significant differential diagnosis implications.

Imaging Characteristics

Both CT and MR imaging are used in the evaluation of chordoma. CT is ideal for evaluating the bony involvement, whereas MR imaging is useful in evaluating the surrounding soft tissues and extension into adjacent structures. MR imaging is considered the gold standard in pretreatment and post-treatment evaluation of chordomas.1,9

On CT, the typical appearance for an extraosseous chordoma is a lobular hypoattenuated soft-tissue mass with areas of dystrophic calcification and lytic changes of affected osseous structures. Scattered areas of hyperattenuation are consistent with descriptions in the literature of blood products and intratumoral hemorrhage in typical chordomas.1-3

The interesting feature in our series is a sinus tract along the expected course of the notochordal remnant. The associated midline bony tract is an important clue to the notochordal origin of this extraosseous chordoma because other nasopharyngeal malignancies may destroy clival bone but do not demonstrate this midline tract. One of 5 cases we present is a Tornwaldt cyst mimic. In this specific example, the subtle sinus tract into the clivus helped distinguish this lesion from a Tornwaldt cyst.

With MR imaging, the features of the extraosseous chordomas are similar to typical skull base chordomas. The lesions were predominantly hyperintense compared with muscle on T2 sequences. The lesions were heterogeneous and demonstrated intratumoral septations. These findings suggest that though extraosseous chordomas can have atypical locations, the tumors will continue to demonstrate typical MR imaging characteristics.

Treatment

Improving outcomes are being obtained with surgical resection of intracranial chordomas.10-12 The main complication to treatment of chordomas remains local recurrence. In the case of an extraosseous chordoma, the removal of chordoma along the clival bony sinus tract along with the extraosseous tumor may be important to limiting the early recurrence of this lesion. MR imaging remains the standard for evaluating postsurgical patients and surveillance for recurrence. The most commonly cited finding of recurrence is hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences rather then morphologic changes.1 Contrast-enhanced imaging further aids in detecting areas of recurrence along the surgical margins. Distant metastasis is very rare in chordomas.13

Differential Diagnosis

Extraosseous chordoma is primarily a lesion of the nasopharyngeal soft tissues. For the purposes of our discussion, due to the location, the differential diagnosis primarily includes nasopharyngeal tumors. The differential diagnosis list is significantly different from the standard differential considerations for a classic chordoma. The differential for this variant lesion includes nasopharyngeal carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma differs from chordoma in that there is a demographic predilection among Chinese and North Africans.14,15 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the nasopharynx is a relatively uncommon tumor. The age distribution for non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the head and neck is in the sixth decade.16 Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy remain the primary treatment modalities for both nasopharyngeal carcinoma and lymphoma. Interestingly, as seen in our small series, a small extraosseous chordoma may mimic a Tornwaldt cyst, a benign notochordal remnant entity.

Conclusions

Extraosseous chordoma of the nasopharynx is a rare but important tumor to be considered in the differential diagnosis of nasopharyngeal masses. When a midline nasopharyngeal mass is found with an associated clival sinus tract, extraosseous chordoma moves to the top of the differential diagnosis list. Complete removal of the soft-tissue tumor and the clival sinus tract is the treatment of choice in such cases.

References

- 1.Erdem E, Angtuaco E, Hemert R, et al. Comprehensive review of intracranial chordoma. Radiographics 2003;23:995–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiFrancesco LM, Castillo C, Temple WJ. Extra-axial chordoma Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1871–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masui K, Kawai S, Yonezawa T, et al. Intradural retroclival chordoma without bone involvement. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006;46:552–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlin DC, MacCharty CS. Chordoma: a study of 59 cases Cancer 1952;5:1170–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribbert H, Virchow R. Chordoma. In: Windeyer BW. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine,Vol. 52 .1959. :1088–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madeline LA, Elster AD. Postnatal development of the central skull base: normal variants Radiology 1995;196:757–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes ML, Carty AT, White FE. Persistent hypophyseal (craniopharyngeal) canal. Br J Radiol 1999;72:204–06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsot-Dupuch K, Smoker WR, Grauer W. A rare expression of neural crest disorders: an intrasphenoidal development of the anterior pituitary gland. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:285–88 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson TC, Houser W, Laws ER. Imaging of cranial chordomas Mayo Clin Proc 1987;62:886–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin-Seymour M, Munzenrider J, Goitein M, et al. Fractionated proton radiation therapy of chordoma and low-grade chondrosarcoma of the base of the skull. J Neurosurg 1989;70:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes L. Pathology of selected tumors of the base of the skull Skull Base Surg 1991;1:207–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes L. Chordoma. In: Rice DH, Batsakis JG. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. New York: Marcel Dekker;1985. :967–71

- 13.Heffelfinger MJ, Dahlin DC, MacCarty CS, et al. Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors at the skull base Cancer 1973;32:410–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King AD, Lei KI, Richards PS, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the nasopharynx: CT and MR imaging. Clin Radiol 2003;58:621–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber AL, al-Arayedh S, Rashid A. Nasopharynx: clinical, pathologic and radiologic assessment Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2003;13:465–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urquhart A, Berg R. Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the head and neck Laryngoscope 2001;111:1565–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]